Abstract

This article explores mock sea-fights performed on the Thames in 1610 and 1613, which marshalled civic and naval vessels and personnel to offer spectators a realistic representation of the noise and magnitude of maritime combat. These nautical performances are a unique and important form of civic theatricality that offered Londoners an alternative means of visualizing the kinds of nautical combat they would have encountered in stage plays and news pamphlets. My analysis of printed accounts and eye-witness reports of these mock sea-fights explicates their complex negotiation of artifice and feigning on the one hand and realism on the other, whereby the grim realities of naval combat manifested themselves in the process of performance. The article likewise considers how this unique form of entertainment was presented to book-buyers and readers in pamphlets that feature paratextual woodcut illustrations of ships, which align the publications with other genres of ‘maritime’ print. Ultimately, what follows demonstrates the rich contributions that the mock sea-fight as a form of riverine theatricality can make to our understanding of performance culture in Jacobean London.

The focus of this article is an extraordinary but largely neglected form of waterborne theatricality in Jacobean London: the mock sea-fight. Two such spectacles were performed on the River Thames, the first in June 1610 to celebrate Prince Henry’s investiture as Prince of Wales, and the second in February 1613 for the marriage of Princess Elizabeth. By virtue of their scale and public nature, these feigned nautical encounters were witnessed not only by royal spectators but also by thousands of Londoners on both banks of the Thames. These spectacles staged realistic violent encounters between Christian ships and ‘Turkish’ pirates, the likes of which spectators would have encountered in less realistic or immediate ways in playhouses, in ballads, and in news pamphlets. These choreographed nautical shows mobilized fleets of civic and naval vessels, offering spectators a vicarious, noisy, visually arresting glimpse into the world of naval combat, while at the same time playing out national fantasies of naval supremacy against imagined Ottoman and ‘Turk’ aggressors. Despite being a powerful and wide-reaching expression of anti-Ottoman sentiment, these shows tend to get only occasional, cursory attention in scholarship on theatrical representations of ‘Turks’, and receive little attention in studies of early modern drama more generally.Footnote1 This article likewise fills a gap in scholarly attention to how these shows ‘function’ in print. I interrogate how printed accounts negotiate this unique type of ephemeral entertainment, reflecting in particular on the use of paratextual woodcut illustrations of ships that feature in several publications containing descriptions of the shows. My exploration of these entertainments situates them within a wider context of cultural fascination with maritime combat and Mediterranean piracy, both in terms of their narrative content and the material texts in which descriptions of the sea-fights were published. What follows explores how these complex spectacles negotiated between artifice and reality in performance and in print, demonstrating how this genre of entertainment can expand our understanding of London’s theatrical culture and imaginative engagement with the maritime world.

The Thames had long played a crucial role in civic festivities, serving as both a means of passage and a watery stage during occasional royal processions and annual Lord Mayor’s Day celebrations. Critical work on mayoral pageantry has addressed the mayor-elect’s journeys by river and their attendant pageantry, which included a vibrant flotilla of vessels accompanied by trumpets, drums, and the thundering gunfire of the galley-foist, as well as symbolic and allegorical devices pertaining to mercantile ambitions.Footnote2 Jacobean mock sea-fights also represent mercantile concerns, but this genre of entertainment belongs to a rather different entertainment tradition: the naumachia (Greek for ‘naval battle’). This form of entertainment was inaugurated in the first century BCE, and was typically concerned with violent recreations of historical battles on natural bodies of water and, more commonly, on artificially constructed lakes or in flooded amphitheatres.Footnote3 This type of waterborne entertainment was revived in France, Italy, and Spain in the sixteenth century, in lavish — albeit usually less violent — ways. Although a naumachia was held in Edinburgh in 1562, it was not until the Jacobean period that comparable entertainments occurred in England’s capital.Footnote4 In discussing the Jacobean spectacles I use the term ‘mock sea-fight’ rather than naumachia because these English examples differ somewhat from their Continental predecessors in scale, setting, and content, and the term naumachia was not applied to such performances in Jacobean England. The language typically used in descriptions of these entertainments emphasizes fiction and approximation; ‘imitation’, ‘supposed’, ‘pretended’, and ‘jesting’ are the terms most commonly applied. Such terms stress the theatricality and artifice of these nautical performances, but, as my examination of these shows will demonstrate, theatrical imitation of naval combat had the potential to be overwritten by physical harm and misadventure, thereby unintentionally realizing the gore and bloodshed of maritime combat.

The mock sea-fights of 1610 and 1613 were vicarious shows of naval supremacy over Ottoman aggressors. Scholars have documented the enduring cultural interest in Ottoman history and ‘Turks’ during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, most prevalently in print and on the playhouse stage.Footnote5 The term ‘Turk’ encompassed not only inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire but also North African regions beyond Ottoman borders, and it was often used as a general term for those belonging to the Islamic faith.Footnote6 Pirates and corsairs operating from the Barbary Coast had long been a threat to European shipping interests in the Mediterranean, and fears about depredation at sea, kidnapping, and conversion to Islam circulated in the cultural consciousness in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.Footnote7 By the time that the Jacobean mock sea-fights were staged on the Thames, Anglo-Ottoman relations had undergone a shift that had important implications for England’s role in the maritime world. Elizabeth I had sought cooperation with Ottoman rulers, finding in them powerful potential allies against Spain, their common enemy.Footnote8 Letters of marque were issued to Englishmen by way of encouraging maritime assaults against Spanish shipping, and officially sanctioned privateering opened up a world of dangerous and alluring possibilities for power and wealth, but also brought with it anxieties about apostacy and conversion to Islam. As the work of Nabil Matar and others has shown, during Elizabeth I’s reign there were numerous Anglo-Ottoman ambassadorial interactions, exchanges, and trade ventures, such as the setting up of the Levant Company, yet even in this context, Anglo-Ottoman relations remained complex and sometimes fraught.Footnote9 Following James VI’s accession to the English throne in 1603 and the subsequent peace with Spain, privateering and piracy were no longer encouraged by the crown, and James repeatedly sought to rein in the piratical activities of his renegade subjects operating from Islamic strongholds, who attacked merchants in the Mediterranean, indiscriminately marauding the ships of their countrymen as well as foreign powers.Footnote10

Scholars have illuminated the popular interest in ‘Turks’ by attending to the prevalence of ‘Turk’ plays in the playhouse repertory system and by exploring links between piracy, Ottoman power, and ‘turning Turk’.Footnote11 Indeed, early modern plays that deal with maritime adventuring, such as John Heywood’s Fair Maid of the West (c. 1609–11, published 1631) and Heywood and William Rowley’s Fortune by Land and Sea (c. 1607–9, published 1655), feature piratical practices and encounters, some of which bring English characters into contact with Islamic forces. Accounts of maritime depredations by North African corsairs, Ottoman Turks, and English renegades frequently circulated in print, providing readers with descriptions of sea-fights and depredations. Sometimes, these printed accounts served as fodder for stage plays, where the textual material was adapted and brought to life in performance. For instance, Robert Daborne’s A Christian Turn’d Turk (c. 1610–11, published 1612) directly engages with issues of religious conversion and piracy by dramatizing the historical figure of John Ward, whose exploits were initially recounted in several 1609 news pamphlets and in ballad form.Footnote12 Plays that featured renegade figures like Ward explored the allure of piracy and potential gains of conversion to Islam, highlighting how piracy and Islam were linked in the minds of English readers and theatregoers.

Nautical combat featured prominently in the plays noted above, but for practical reasons such action took place off-stage, represented by means of special effects, such as the firing of unloaded ordnance, alarums, shouts, or else through dialogic or choric descriptions.Footnote13 Mock sea-fights, by comparison, offered a realistic representation of such action, extending the familiar sonic and olfactory elements of playhouse effects in visually and materially immediate ways, inviting sensory associations between different performance environments. For many spectators, the sea-fights undoubtedly became experiential reference-points for future imaginary encounters with maritime combat. Likewise, mock sea-fights provided a materially different means of representing the military threat posed by the Ottoman Turks than the plays staged in London’s playhouses. Yet, despite the impact of these public nautical shows, they receive only cursory, occasional attention, normally in larger studies of ‘Turks’ in early modern drama and theatrical culture, which do not fully consider how these shows functioned in performance and in print.

Jacobean mock sea-fights on the Thames were a form of civic entertainment openly visible and audible to thousands of Londoners, but they were primarily intended to appeal to the interests of the royal spectators. The first such entertainment was performed in honour of Prince Henry, and was especially appropriate given Henry’s active interests in naval reform and ambition to become the Lord High Admiral of the navy.Footnote14 Indeed, Henry’s friendship with key naval figures such as Robert Mansell and Charles Howard (the Lord High Admiral), as well as the royal shipbuilder Phineas Pett, would have facilitated the realization of such nautical shows. While James VI & I did not share Henry’s zeal for naval reform and militant foreign policy, the anti-piracy, anti-Turk content of the shows would have appealed to a monarch who held anti-Islamic views and was actively attempting to suppress piratical activity.Footnote15

Royal and civic public entertainments on the Thames typically elided the kind of violent conflict and confrontation that lies at the heart of mock sea-fights. Although mayoral processions by water were noisy affairs, mayoral and royal civic pageantry tended to highlight harmony, unity, and munificence. The nature of the livery companies’ overseas trading interests often led to the creation of pageants that directly engage with foreign Others such as Moors, Turks, and Indians, who were depicted as pliable and willing participants in trade, which is vastly different from the nautical representation of belligerent Ottoman aggressors in the mock sea-fights.Footnote16 Mayoral civic pageantry often engaged with the idea of the Thames as a vital passageway into the wider world of trade, and while maritime dangers are sometimes mentioned in speeches, foreign threats like the ones found in sea-fights are rarely represented.Footnote17

Mock sea-fights on the Thames were loci at which various dramatic and readerly interests could converge, juxtaposing in the minds of spectators different textual and dramatic experiences of maritime news, anti-Ottoman sentiment, and piracy. I argue that the Jacobean mock sea-fights speak to and are shaped by representations of maritime combat and depredations in playhouse culture, and in balladry and print. The size, noise, and public nature of these mock encounters meant that members of the theatre-going public who had seen pirate and ‘Turk’ plays performed in London’s theatres would have been able to experience in much more realistic and immediate ways the kind of nautical battles that they would have encountered previously in more abstract terms. Indeed, spectators would have placed the mock sea-fights in both performance and print within wider, connected networks of theatrical and textual associations concerning nautical combat and piracy, and for this reason these nautical spectacles warrant closer scrutiny and attention.

Prince Henry’s investiture, 1610

The investiture of James VI & I and Queen Anna’s eldest son, Henry, as Prince of Wales on 31 May 1610 was a momentous occasion for both the heir apparent and the future of the nation. The Thames and marine iconography played an important part in the week-long celebrations, beginning with Henry’s journey from Richmond to Whitehall by water instead of the expected royal progress through the City on foot.Footnote18 On his arrival from Richmond, Henry was greeted by the Mayor, the Aldermen, and a flotilla of decorated barges bearing members of the livery companies, and treated to two water pageants on the river, prepared at the expense of the City by Anthony Munday.Footnote19 Munday, who had ample experience of devising speeches and pageants for civic celebrations, issued a description of the City’s welcome to Henry in a pamphlet entitled Londons Love, to the Royal Prince Henrie (1610; STC 13159), which also contains descriptions of the mock sea-fight and its accompanying firework show.Footnote20 Munday notes that his two-page description of the sea-fight is based on ‘such reporte as was thereof made to me’ (D2r), meaning that he likely did not play a direct part in devising the show. Footnote21 While documentary evidence for the 1610 sea-fight is lacking, the nature of the spectacle would of course have required collaboration of various civic and naval personnel, as the more extensive evidence for the 1613 show demonstrates.

The sea-fight should have taken place on the evening of 31 May, but it was postponed until the evening of 6 June, thereby becoming the final part of the investiture festivities.Footnote22 The main ‘actors’ in the fight were two ‘Turkish’ nautical aggressors who attacked two presumably English merchant ships, which were eventually rescued by two warships. The staging of the sea-fight transformed the Thames into a vision of the open seas, representing for the vicarious pleasure of the spectators the kinds of dangers and depredations that frequently filled the pages of news pamphlets:

A Turkishe Pirate [small ship] prowling on the Seas, to maintaine a Turkish Castle (for so their Armes and Streamers described them both to be) by his spoyle & rapine, of Merchants, and other Passengers; sculking abroade to find a bootie: he descried two Merchants Shippes. (D2v)

The Turkish ‘Pirate’ made advances on a merchant ship, which steadfastly refused to give in: ‘the Merchant either not regarding, or no way fearing, rode still boldely on’ (D2v). This situation escalated when the ‘Pirate’ fired a warning shot, ‘which the Merchant answered againe, encouraged thereto by her fellowe Merchant, who by this time was come neere her, and spake in like language with her to the Pirate’ (D2v). The interaction between the ships is thus presented as a kind of dialogue, spoken in the ‘language’ of gunpowder and pyrotechnics. The exchange of shots intensified and ‘a verie fierce & dangerous fight’ (D3r) ensued. The merchant ships fell into distress after coming under fire from the ‘Castle’, but they were eventually saved by two war ships. Once these men-of-war joined the fight, it ‘grewe on all sides to be fierce indeed, the Castle assisting the Pirate very hotly, and the other withstanding bravely and couragiously’ (D3r). Such a performance must have been wondrous to behold, all the more so given the fight’s conclusion, whereby the merchant ships and men-of-war ‘prooved too strong for the Pirate, they spoylde both him, and blewe up the Castle, ending the whole batterie with verie rare and admirable Fire-workes’ (D3v). The noise and smoke of the battle thus transitioned into an even more visually arresting type of pyrotechnic display at its victorious conclusion.Footnote27

The spectacle undoubtedly delighted Prince Henry on account of his naval ambitions and interests in continental festivals. In fact, it was likely inspired by a report sent to Henry by John Harrington, which described a naumachia performed on the Arno for the wedding of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo II, in August 1608.Footnote28 While the 1610 nautical battle was modest in comparison to continental naumachia, it was nevertheless an important civic show. Aside from providing a visually and sonically arresting spectacle, the mock sea-fight had a perceptible political imperative: mercantile interests at sea are prone to attack from foreign aggressors, which can only be overcome with a strong naval presence. Although Munday’s account does not explicitly identify the merchant ships or men-of-war as English, this encounter was performed at the City’s expense and the involvement of livery companies with overseas trade would have made this a useful opportunity to stage an imaginative representation of domestic merchant ships and English naval vessels. Whether the Christian ships bore the flag of St George or not, the performance clearly echoed English and European anxieties about trade and Mediterranean piracy. In fact, this mock sea-fight prompted a similar conceit that was performed five months later at the 1611 mayoral festivities, devised by Munday and Peter Grinkin, which included ‘Divers Sea-fights and skirmishes’ featuring ships bearing cargo from ‘the rich and Golden Indian mines … [performed] both in the passage to Westminster, and back againe’.Footnote29

The movement of the ships in the 1610 show was choreographed to make the overall narrative clear to the spectators. It is unclear, however, whether the ships’ crews were instructed to feign injury and distress, or whether the intended verisimilitude of the performance came too close to embodying the dangers of maritime combat. Munday’s report is ambiguous on this point: ‘divers men appearing on either side to be slayne, and hurlled over into the Sea, as in such adventures it often comes to passe, where such sharpe assaultes are used indeed’ (D3r). Munday offers an idealized account of the event for public consumption, so any potential harm incurred by the ‘actors’ in this fight is figured as imitation, although it is unclear how one might ‘appear’ to be hurled overboard convincingly without actually falling into the water. Munday’s description highlights how imitation can too easily give way to reality in this type of performance, for in the process of feigning injury members of the ships’ crews necessarily exposed themselves to physical harm. The inherent danger of imitating violence by means of artillery, ordnance, and combat in such nautical performances is even more apparent in relation to the much larger-scale mock sea-fight performed in 1613.

Princess Elizabeth’s wedding celebrations, 1613

The marriage of Princess Elizabeth and Frederick, Elector Palatine, on 14 February 1613 prompted a lavish array of celebrations, including masques, processions, a firework show, as well as a large-scale sea-fight on the Thames.Footnote30 A comprehensive overview of these festivities, including a description of the sea-fight, appears in The Marriage of the Two Great Princes — commonly referred to by critics as The Magnificent Marriage — which underwent two editions in 1613 (STC 11358 and STC 11359). This text was aimed at disseminating an account of the celebrations beyond London; the anonymous author claims it is published for ‘certaine of my acquaintance in the countrey’ (A2r). A description of the water battle and firework shows was also published in John Taylor’s Heavens Blessing, and Earths Joy (STC 23763), along with Taylor’s celebratory poems. These descriptions constitute ‘textual performances’ of the shows, a term originally applied by David Bergeron to printed accounts of mayoral civic pageantry.Footnote31 He argues that mayoral pageant texts ‘constitute a meta-dramatic event’ where ‘dramatic fiction and historical reality’ converge, and this convergence is particularly interesting in how the two textual performances of this sea-fight attempt to explicate and negotiate the boundary between fiction and reality.Footnote32 While the printed accounts are shaped by their need to explicate the intended meanings and outcomes of the performance, surviving eye-witness accounts offer us valuable, more candid, glimpses of the event, as this section will show.

The 1613 sea-fight played out an encounter between the Christian powers Spain, Venice, and England against Islamic forces represented by a ‘Turkish’ fleet and land fortifications, pitting the mercantile and naval interests of Europeans against the Ottomans, which the royal family watched from the privy stairs at Whitehall. In Londons Love, Taylor counts 16 ships, 16 galleys, and 6 frigates, ‘of the which Navy, the Ships were Christians and the Gallies were supposed Turkes, all being artificially rig’d and trim’d, well man’d and furnished with great ordinance and Musquettiers’ (A3v), meaning that the principal nautical ‘actors’ were, as in 1610, identifiable by their ‘trimmings’ as well as by the type of vessel, with the ‘Turkes’ undoubtedly bearing crescent moons. We learn from the autobiography of Phineas Pett, royal ship builder and friend to the recently deceased Prince Henry, that the Venetian ‘argosey’ in the show was represented by ‘an old pinnace of the King’s called the Spy … whereof I was somewhat against my will (by the Lord Admirall’s persuasion) made to serve as a Captain’.Footnote33 Such a comment makes one wonder about how many other nautical ‘actors’ were forced into performing against their better judgement.

Taylor notes that the Turkish galleys lay in wait on Lambeth side opposite Westminster in a specially constructed harbour belonging to a ‘supposed Turkish or Barbarian Castle of Tunis, Algiers, or some other Mahometan fortification’ erected for the event (A3v). This structure is described more precisely in Magnificent Marriage as ‘a Turkish castle, which represented and bare the name of the castle of Argier, furnished with 2. well approved great peeces of Ordinance … [built] at a place named Stand-gate’ (A4v).Footnote34 It is unclear whether the design of the ‘castle’ attempted to imitate a Northern African architectural style; it is possible that the design replicated castles used in European firework shows, in this case bearing the label of ‘Argier' on a board to make it more easily identifiable.Footnote35 The ‘Venetian’ ships, according to Taylor, came down the river from the direction of Temple Stairs and were met on the section of the river at the south end of what is now the Victoria Embankment Gardens by four Turkish galleys, where a ‘friendly exchanging of smal shot and great ordinance on both sides’ (A4r) took place. The Venetian ships were captured and the rest of the Christian fleet rushed to their aid, whereupon ‘all the Ships and Galleyes met in freindly opposition and ymaginary hurley-burley battalions … the thundring Artillary roared, the Musqueteirs in numberless volleys discharged on al sides’ and the fortification on land likewise discharged ‘great shot in aboundance at the Ships, and the Ships at them againe’ (A4r). Even though live ammunition was not used in this ‘ymaginary’ encounter, the use of artillery and muskets, together with the sheer number of vessels and performers involved, meant that co-ordinating and choreographing such a spectacle was no mean feat.

Practical arrangements for the event were overseen by naval personnel, and it appears that Sir Robert Mansell, former naval officer turned administrator, was in charge of the finances, while watermen and musketeers performed in the entertainment.Footnote36 A letter by John Chamberlain dated 11 February (the day of the firework show on the river) indicates the scale of the preparations:

The preparations for fire workes and fights upon the water are very great, and have alredy consumed [£]6000 which a man wold easilie beleve that sees the provision of sixe and thirty sayle of great pinesses, galleasses, carraques with great store of other smaller vessels so trimmed, furnished and painted, that I beleve there was never such a fleet seen above the bridge, besides fowre floting castles with fire workes, and the representation of the towne, fort and haven of Argier upon the land.Footnote37

attended by the Principal Officers of the Navy, the Masters and Master Shipwrights, to resolve not only for the preparation of the fleet to attend the transportation [of Elizabeth and Fredrick to the Continent after the wedding], but also for preparing many vessels, to be built upon long boats and barges, for ships and galleys for a sea-fight to be presented before Whitehall.Footnote38

The scale of the 1613 mock sea-fight was far greater than that of the 1610 one. Not only did it involve a greater number of vessels, but it also spilled forth the fictional Mediterranean seascape from the river onto the land, transforming the south bank of the Thames at Lambeth into a recognizably North African location through the erection of fortifications and a harbour. Bergeron’s discussion of the 1613 sea-fight situates it in the context of courtly and literary engagements with Christian-Islamic conflict at the battle of Lepanto (1571), widely hailed as a triumph for Christian forces, albeit a short-lived one.Footnote43 Although neither England not Scotland were involved in the battle, James VI & I wrote a heroic poem on the subject around 1585, subsequently published in London in 1603, and Bergeron proposes that this performance was no doubt intended to appeal to the King’s interest in this respect.Footnote44 This is supported by Taylor’s direct invocation of Lepanto in his account, although I would argue that for many of the civic spectators the more immediate interpretative framework for this entertainment would have been news pamphlets, pirate pamphlets, and plays dealing with sea-faring, piracy, and ‘Turks’, such as Fair Maid and A Christian Turn’d Turk, for example. Taylor’s description of the event’s realistic use of aural and visual effects gives way to a consideration of the grim realities of combat at sea in their historic contexts, whereby in the cacophony of

Drummes, Trumpets, Fifes, Weights, Guns, showts, & acclamations of the Mariners, Soldiers and spectators, with such reverberating Echoes of joy to and fro, … there wanted nothing in this fight (but that which was fit to be wanting) which was ships sunk and torne in peices, men groning, rent and dismembered, some slaine, some drowned, some maimed, all expecting confusion. This was the manner of the happy and famous battell of Lepanto fought betwixt the Turks and the Christians, in the yeare of grace 1571. Or in this bloody manner was the memorable battaile betwixt us and the invincible (as it was thought) Spanish Armado in the yeare 1588. (A4r)

Taylor reports that the battle lasted some three hours until retreat was sounded by both sides, and his report of the conclusion emphasizes the fictional nature of the staged encounter rather than a clear victory: ‘the Victorie inclyning to neither side, all being opposed foes, and combyned friends: all victors, all tryumphers, none to be vanquishd, and therefore no conquerors’ (A4r-A4v). According to Taylor, then, there were no winners or losers in the fictional battle. This ending appears to be somewhat of a damp squib, and contradicts the idealized anticipatory account of the sea-fight’s conclusion found in Magnificent Marriage, which describes the intended ending as well as supplying additional details about the Christian fleet lacking from Heavens Blessing.Footnote45 Unsurprisingly, more emphasis is placed on the presence of English ships in the fight: ‘the Scoutes and Watches of the Castle, discovered an English Navie, to the number of fifteene Saile of the Kings Pinnaces … with their red crost Streamers most gallantly waving in the Ayr’ (Marriage, A4v). While the report acknowledges that the fight went on for a long time with ‘the victorie leaning to neither side’ (B1r), eventually the reader is told that the English Admiral’s ship cast anchor, subdued their adversaries, and sacked the castle, taking prisoners who were then presented to the King. ‘The English Admirall, in a most tryumphant manner carried as a prisoner, the Admirall of the Gallies attired in a red Jacket with blow sleeves, according to the Turkish fashion, with the Bashawes, and the other Turkes’ to the Privy Stairs at Whitehall, where the prisoners were handed over to Robert Mansell, then to Charles Howard — the real-life Lord Admiral — who in turn presented them to the King as ‘a representation of pleasure, which to his Highnes moved delight, and highly pleased all there present’ (B1r). Magnificent Marriage supplies details absent from Heavens Blessing, and in so doing offers a more complete account of the entertainment’s intended outcomes, some of which did not materialize as expected on the day of the performance.

Reasons for the somewhat anti-climactic conclusion described by Taylor in Heavens Blessing may be found in Chamberlain’s account of the performance:

the fight upon the water came short of that shew and bragges had ben made of yt, but they pretended the best to be behind and left for another day, which was the winning of the castle on land: but the King and indeed all the companie tooke so litle delight to see no other activitie but shooting and potting of gunnes that yt is quite geven over and the navie unrigged and the castle pulled downe.Footnote46

divers [were] hurt in the former fight, (as one lost both his eyes, another both his handes, another one hande, with divers other maymed and hurt) so that to avoyde further harme, yt was thought best to let yt alone.Footnote48

Jacobean mock sea-fights staged on the Thames are a mode of theatricality that does not centre the bodies of human actors trained for dramatic performance, relying instead on the practical expertise of naval, military, and civic personnel. The skills of these men made possible a choreographed performance of vessels that were marshalled to enact in realistic terms the type of naval combat that was frequently reported in news pamphlets and dramatized in plays written for the professional stage. This form of public entertainment is a powerful means of enacting cultural fantasies about maritime supremacy, and I agree with Bergeron that the mock sea-fights ‘offer a means to confront the Turks in fiction … discharging anxiety, controlling it, and supplanting it with the assurance of victory’, but I would also add that it is important to acknowledge that the unintended injuries arising from this type of performance had the potential to undermine the ‘assurance of victory’, as was the case in the 1613 show.Footnote50 Where Bergeron suggests that mock sea-fights ‘represent the thrill of battle against the “enemy” without any serious risk’ to the nation, I would stress that they are nevertheless marked by serious risk to the human participants involved. The injuries sustained by the performers in the process of using ordnance and artillery to feign maritime combat clearly had the potential to inflict harm on civic labourers and naval personnel, thereby puncturing the fraught division between imitation and reality.

Mock sea-fights in print

The discussion so far has focused on mock sea-fights in performance, situating this unique form of riverine theatricality within a larger context of national fantasy and cultural fascination with the maritime world. This section considers how the mock sea-fights are presented in print, arguing that the inclusion of this unique form of spectacle within larger publications affects how those publications are organized bibliographically and presented to readers in material terms. More specifically, I demonstrate how descriptions of mock sea-fights tend to dominate the pamphlets in which they were published, namely by means of paratextual elements such as woodcut illustrations and title pages. These bibliographical features highlight the spectacular nature of the shows and extend the sense of nationalistic fantasy by aligning these commemorative pamphlets in visual and material ways with maritime news, pirate pamphlets, ballads, and navigational manuals. I focus on Munday’s Londons Love and Taylor’s Heavens Blessing, both of which were printed by Edward Allde, and I propose that the ship woodcuts found on the initial leaves of these publications place them into a wider readerly network of visual associations that encompasses other genres of ‘maritime’ print.

Early seventeenth-century printers frequently used decorative ornamentation in their publications, including printers’ ornaments, headpieces, tailpieces, decorative borders, woodcut illustrations, and engravings across a range of different genres and formats of print.Footnote51 While some books necessitated the production of specific illustrations, printers had a tendency to reuse ‘generic’ woodcuts across different publications, both in the main body of texts and on title pages. As James Knapp notes, literary scholars tend to treat such woodcuts dismissively, especially those that are frequently recycled across different texts.Footnote52 However, Christopher Marsh’s study of woodcut recycling habits in early modern ballads has challenged a long-standing ‘tendency to assume that the reuse of images suggests apathy about their significance on the part of producers and consumers alike’.Footnote53 Marsh argues that frequently reused woodcuts in balladry were a ‘central component … rather than a feeble extra’, and that the ‘redeployment of pictures was in fact an incitement to engage and debate, rather than a reflection of apathy’.Footnote54 Although any arguments about early modern visual interpretative practices ought to remain tentative, studies such as Marsh’s demonstrate the value of attending closely to the circulation of ‘generic’ images in early modern print and what they can tell us about networks of visual associations. Prefatory or title page illustrations certainly influence a reader’s initial interaction with the text. In her discussion of textual surfaces, Lucy Razzal identifies the ‘distinctive exterior surface’ of the early modern title page as a locus ‘for other important information about the work’, arguing that it is an important site of ‘initial encounter’.Footnote55 I propose that in publications such as Londons Love and Heavens Blessing, ship illustrations act as sites of ‘initial encounter’ that invite the book-buyer or reader to place those publications (and accounts of the sea-fights therein) into an existing network of associations built up by exposure to other texts featuring such images.

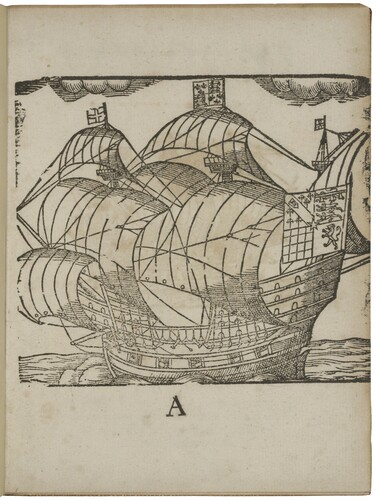

The ordering of visual and textual information on the first two leaves of Londons Love is particularly notable in this respect: the first leaf bears two ship illustrations ( and ), with an unillustrated title page appearing on the recto of the second leaf. This type of illustrated first leaf is exceptional in a publication of royal festivities; typically, before the publication of Londons Love, royal celebration texts did not feature ‘generic’ woodcut illustrations in this way. Specially made woodcuts and engravings were a different matter: Stephen Harrison’s The Arch’s of Triumph (1604; STC 12863) contains a set of detailed engravings of the lavish arches erected for James VI & I’s entry into London, and a specially made heraldic woodcut illustration appears in Chesters Triumph in Honor of her Prince (1610; STC 5118). When it comes to extant pamphlets commemorating the royal marriage festivities of 1613, it is only the title pages to Heavens Blessing and Magnificent Marriage that bear ‘generic’ illustrations. The latter, printed in two editions by Thomas Creed, features illustrations of armed figures on horseback on the title pages, loosely alluding to a tilt described in the account.Footnote56 It is also worth noting that printed accounts of the annual mayoral civic celebrations typically did not include illustrations, generic or otherwise.

FIGURE 1 Londons Love (London, 1610), A1r, bearing a Type 4 ship woodcut. Call #: STC 13159. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

FIGURE 2 Londons Love (London, 1610), A1v, bearing a Type 8 ship woodcut. Call #: STC 13159. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Londons Love is an exceptional early Jacobean example of a commemorative account that uses repurposed ‘generic’ woodcut illustrations. Given the nautical and riverine content of the text, it is unsurprising that Allde should have used ship illustrations to ‘dress’ the publication, and this decision impacts book-buyers’ and readers’ experience of the pamphlet as a material object by having the images serve as ‘paratextual induction’ to the text that follows.Footnote57 Ship illustrations were frequent in print, as evidenced by Luborsky and Ingram’s A Guide to English Illustrated Books, 1536–1603, which outlines 12 distinct ‘types’ of ship woodcuts.Footnote58 The recto of the first leaf of Londons Love () contains a signature mark beneath a Type 4 woodcut illustration of a large ship; the verso of the first leaf () contains a smaller ship, identified as Type 8 by Luborsky and Ingram. The Type 4 ship in bears four flags: the arms of England on the mainmast, St George’s cross atop the foremast and the mizzenmast, while the bottom part of the mizzenmast displays the arms of Charles Howard, Lord High Admiral of the navy from 1585 until 1619. Luborsky and Ingram do not ascribe the arms to Howard, but an identical version of the arms is found on the Lord Admiral’s seal and in portrait engravings of Howard.Footnote59 Given the Lord Admiral’s prominence in the context of turbulent relations with Spain in the 1580s, it is unsurprising that a printer should have decided to invest into the creation of a woodblock of a war ship bearing Howard’s arms. This woodcut illustration circulated in a range of news pamphlets about skirmishes at sea prior to its appearance in Londons Love.Footnote60

The presence of the Type 4 ship on the first leaf of Londons Love performs several functions, regardless of whether these functions were directly intended by the printer or not. Given the contents of the text that follows, the image is not simply decorative but illustrative of the nautical festivities generally and of the Lord Admiral’s arms specifically, since they would no doubt have featured on the men-of-war. Yet without prior knowledge about the pamphlet’s textual content, the first leaf of Londons Love aligns it with other genres of publications, such as maritime news or navigation manuals.Footnote61 Knapp suggests that woodcuts ‘opened the text to multiple and sometimes contradictory readings (and viewings)’, which holds true in this case.Footnote62 The appearance of this ship without textual context potentially aligns the report of the 1610 investiture water pageantry with other genres of print, and in so doing privileges the role of the mock sea-fight (which occupies only the final two pages of text) over the other elements of the account (which take up 23 pages).

Although Ingram and Luborsky’s Catalogue is not exhaustive and terminates in 1603, a perusal of entries on publications bearing the 12 types of ship woodcuts identified therein reveals that they generally appear on maritime news publications and navigation manuals. Supplementary investigation using the English Short Title Catalogue and Early English Books Online confirms a continuation of this pattern beyond 1603. A dismissive evaluation of the ship illustrations in Londons Love would dictate that it is merely a case of the printer enhancing this already handsome publication by arbitrarily decorating a blank leaf with some woodcuts that he happened to have in his possession, but the bibliographic situation warrants fuller consideration. It is common to find an initial blank leaf (sometimes with a signature mark) preceding the title page in books and pamphlets from this period, so the decision to include a protective outer leaf in a pamphlet of this type is unsurprising, given that such items would be sold unbound. Footnote63 However, the decision to decorate that ‘blank’ leaf with a prominent image of the Lord Admiral’s ship is more unusual, although it appears that Allde had done this before in several maritime news pamphlets. For example, the first leaf of A True and Credible Report (c.1600; STC 20891) contains only a signature mark, with a Type 4 Lord Admiral’s ship on the verso and the title page proper appearing on the second leaf. Similarly, in An Hour Glasse of Indian Newes (1607; STC 18532), the recto of the first leaf contains a half-title above a Type 8 ship before the unillustrated title page appears on the second leaf. Undoubtedly, the use of the large Type 4 ship in Londons Love is a deliberate strategy to enhance the publication; the ship displays the arms of the Lord Admiral, which is fitting for a textual account of a performance of English naval power. The size of the woodcut, however, would preclude its use on the title page, which privileges textual content and (like the rest of the publication) a liberal use of white space. Thus, it might be that in wishing to feature this specific illustration without overcrowding and impinging on the textual content of the title page, Allde dedicated a ‘blank’ leaf for it especially, so that the Lord Admiral’s ship could provide the first site of a reader’s interaction with the publication. Whatever Allde’s motivation, the presence of these ships serves to privilege the nautical content of the text, which is only a minor part of the publication as a whole.

A similar type of privileging is at play on the title page of Heavens Blessing, also printed by Allde. This pamphlet does not contain a blank leaf; the title page appears on A1r, where a Type 7 ship sits underneath the subtitle: ‘A true relation of the supposed Sea-fights & Fire-workes … with Triumphall Encomiasticke Verses’. Interestingly, another title appears on A3r, announcing ‘Epithalamies. Or, Encomiastick Triumphal verses … With a description of the Sea-fights & fireworkes’, even though an account of the fight — not the verses — immediately follows. The poems actually begin on C4r, preceded by their own title page; the wording on this supplementary title page also announces verses, then sea-fight. This might suggest some re-shuffling of priorities during the process of composition and printing, since the title page for the verses appears to have been intended as the title page for the entire publication, but was supplanted by a more nautically oriented layout that presented the sea-fight as the main element of the pamphlet. Indeed, at a first glance the title page of Heavens Blessing certainly looks like that of a navigation manual or a maritime news pamphlet.Footnote64

The nautical elements of Heavens Blessing are certainly privileged over the verses, both on the title page and by the subsequent appearance of the large ship featuring the Lord Admiral’s arms on A2v and B4v, where it breaks up visually parts of the text dealing with the sea-fight and the firework show. As with Londons Love, the large ship illustration may have been included here for its potential to perform an illustrative function, gesturing towards the presence of domestic warships represented in the entertainment. The arms of the Lord Admiral would have featured on the flags and banners of the English fleet, since the Admiral was personated in the performance. The repeated presence of a ship bearing Howard’s arms in a published report of the mock sea-fight links both the form of entertainment and the material text to the realities of national maritime endeavour and naval defence of England’s political interests.

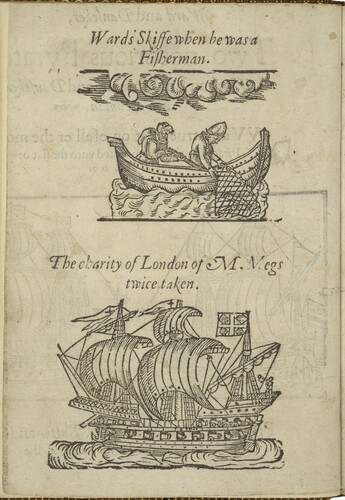

Literary scholars tend to overlook or dismiss the relevance of ‘generic’ woodcut illustrations, but their presence nevertheless impacts readers’ encounters with the material texts in which they appear. The two publications containing accounts of mock sea-fights printed by Edward Allde in 1610 and 1613 are useful examples of how apparently ‘generic’ woodcuts have meaningful illustrative rather than purely decorative functions and align the publication with other genres of ‘related’ print. It is reasonable to suppose that readers of maritime news pamphlets would have built up a network of mental associations within which to place the ship illustrations catalogued by Luborsky and Ingram, including those discussed above. Undoubtedly, the ship illustrations used in Londons Love and Heavens Blessing would have invited associations with other illustrated texts, including those pertaining to piracy and maritime depredations, thereby creating visual links between those types of publications and reports of the royal festivities. In fact, in the year prior to the publication of Londons Love Allde printed several news pamphlets about the capture of pirates, all of which used the Type 8 ship woodcut in . The ship appears on A1r of The Lives, Apprehensions, Arraignments and Executions of the 19. Late Pyrates (STC 12805), and again in Newes from Sea, of two notorious Pyrats (STC 25022), which uses the images on the final leaf (B4r), while the second issue, Ward and Danseker: two notorious pyrates (STC 25022.5), moves the ship to the verso of the title page ().Footnote65 It is notable that a woodcut used in this set of publications about an Englishman who had converted to Islam and turned pirate should re-surface in the context of an Anglo-Ottoman mock sea-fight in the following year. The accumulated meanings of these otherwise ‘generic’ woodcuts would no doubt have invited narrative expectations that reports of mock sea-fights fulfil in ways that are both similar to and different from these other types of ‘maritime’ publications.

FIGURE 3 Ward and Danseker: two notorious pyrates (London, 1609), A1v. Call #: STC 25022.5 Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

In Londons Love and Heavens Blessing, the mock sea-fight ‘dominates’ the larger publication through the presence of ship woodcuts and the ordering of information on the title pages. These paratextual features align the material texts with a wider cultural fascination with piracy and maritime news, which was invoked repeatedly on the playhouse stage as well as in print. The mock sea-fight — as a form of theatricality and a textual ‘event’ — thus offers us a valuable insight into a powerful expression of anti-Ottoman, anti-piracy, nationalistic sentiment. While it is impossible to uncover with absolute certainty how early modern book-buyers or readers would have responded to the presence and ordering of the visual and textual information spread across the initial leaves of Londons Love and Heavens Blessing, these publications nevertheless demonstrate the utility of attending seriously to the presence and function of paratextual illustrations in early modern print, particularly in relation to material texts that sought to capture ephemeral forms of extraordinary entertainment like the 1610 and 1613 nautical shows. Printed descriptions of Jacobean mock sea-fights on the Thames come down to us as a component of publications that include a much wider array of material, and as I have argued here they ‘dominate’ these publications, privileged through paratextual elements such as title pages and woodcuts. I have suggested that paratextual illustrations are a key means of privileging the content of nautical spectacle and that ship woodcuts function as a means of highlighting not only the spectacular and realistic nature of the shows in print, but also a means of conveniently giving expression to national maritime ambition. In this sense, the paratextual images highlight the ideological content of the mock sea-fights above the other content of the publications in which they were printed.

Conclusions

This article has investigated the mock sea-fight as a unique form of civic waterborne entertainment in Jacobean London. These shows mobilized a variety of civic, royal, and naval vessels and put them to use as ‘actors’ on the river Thames for the delight of the royal family, foreign emissaries, and the City’s inhabitants. In so doing, these performances capitalized on cultural fascinations with news pertaining to sea-battles and piracy, as well as anti-Ottoman sentiment, which manifested itself in news pamphlets and in London’s playhouses. Mock sea-fights offered spectators a new way of visualizing similar nautical skirmishes in the playhouses and in print. Attending to how mock sea-fights were ‘staged’ in both performance and print helps to broaden our understanding of how popular tropes relating to piracy, Ottoman power, and nationalistic fantasy functioned beyond the playhouse stage. I have demonstrated that this form of riverine nautical theatricality was a powerful means of enacting national fantasies of maritime supremacy within a (relatively) controlled environment, while highlighting its attendant dangers. By considering closely the ‘textual performances’ of the mock sea-fights in printed accounts alongside contemporary eye-witness reports, this article has painted a fuller picture of how these shows likely came together in performance. Likewise, I have offered here the first meaningful bibliographical consideration of two key publications containing accounts of the 1610 and 1613 mock sea-fights, highlighting how paratextual illustrations align these texts and events with other forms of print and cultural production. Taken together, these strands of enquiry illuminate the way in which the mock sea-fight as form of entertainment offers an important contribution to wider theatrical, literary, and national expressions of naval strength and anxieties about Ottoman power, piracy, and the maritime world.

Acknowledgements

This article arises from a contribution to a seminar panel at the 2019 Shakespeare Association of America annual meeting. I offer my thanks to the convenors, Andrew Gordon and Tracey Hill, and to the other seminar participants — especially David M. Bergeron and Sarah Crover — for their thoughtful comments and feedback on my research. I am also grateful to Aaron Pratt at the Harry Ransom Center for his assistance with reference queries, and to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and recommendations.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria Shmygol

Maria Shmygol is a Research Fellow on the AHRC-funded ‘The Complete Works of John Marston’ project at the University of Leeds. She is preparing an edition of William Percy’s The Aphrodysial, or Sea-Feast (1602) for the Malone Society, and is the co-editor, with Lukas Erne, of the German play Tito Andronico (1620), which is forthcoming with Arden Shakespeare.

Notes

1 A key exception is D. M. Bergeron, ‘Are We Turned Turks?: English Pageants and the Stuart Court’, Comparative Drama, 44:3 (2010), 255–75. The sea-fights are discussed briefly in S. C. Chew, The Crescent and the Rose: Islam and England During the Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1937), 459-61; and R. Barbour, Before Orientalism: London’s Theatre of the East, 1576–1626 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 99–101.

2 See: T. Hill, Pageantry and Power: A Cultural History of the Early Modern Lord Mayor’s Show, 1585–1639 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010), 1–2, 155–68, and D. Carnegie, ‘Galley-foists, the Lord Mayor’s Show, and Early Modern English Drama’, Early Theatre, 7:2 (2004), 49–74.

3 See: M. E. Muñoz-Santos, ‘Why Ancient Rome Staged Epic, Violent Sea Battles’, National Geographic History Magazine, 26 September 2017 <https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2017/09-10/roman-mock-naval-sea-battles-naumachia/> [accessed 20 August 2020].

4 See: P. Bandara, ‘Mary, Queen of Scots’ Aquatic Entertainments for the Wedding of John Flemming, Fifth Lord of Fleming to Elizabeth Ross, May 1562’, in M. Shewring (ed.), Waterborne Pageants and Festivities in the Renaissance (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), 199–209. Small-scale allegorical performances of waterborne conflict featured in Elizabethan progress entertainments at Kenilworth (1575) and Elvetham (1591); another Jacobean mock sea-fight was also staged in Bristol in June 1613 (see STC 18347 and Bergeron, ‘Turks?’, 269–72).

5 Jonathan Burton notes that between 1579 and 1624, over 60 dramatic works featured Islamic themes, characters, or settings. J. Burton, Traffic and Turning: Islam and English Drama, 1579–1624 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2005), 11. See also: M. Dimmock, New Turkes: Dramatizing Islam and the Ottomans in Early Modern England (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005); J. Schleck, Telling Tales of Islamic Lands: Forms of Mediation in English Travel Writing, 1575–1630 (Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 2011); B. Andrea and L. McJannet (eds.), Early Modern England and Islamic Worlds (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011); D. Vitkus, Turning Turk: English Theater and the Multicultural Mediterranean (Houndmills: Palgrave, 2003).

6 On definitions of ‘Turk’, see: <https://www.tideproject.uk/keywords-home/> [accessed 22 March 2021].

7 These issues are explored at length by Burton, Traffic and Turning; and by N. Matar, Islam in Britain, 1558–1685 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); N. Matar, Britain and Barbary, 1589–1689 (University Press of Florida, 2005); and N. Matar, British Captives from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, 1563–1760 (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

8 See, for example: J. Brotton, This Orient Isle: Elizabethan England and the Islamic World (London: Penguin, 2016).

9 See: N. Matar, Turks, Moors, and Englishmen in the Age of Discovery (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999); and J. Brotton, This Orient Isle: Elizabethan England and the Islamic World (London: Penguin, 2016).

10 See: J. Larkin and P. Hughes (eds.), Stuart Royal Proclamations (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973–1983), vol. 1, 30–31, 55, 98–99, 145–6, 203–6.

11 See: M. Hutchings, Turks, Repertories, and the Early Modern English Stage (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017); Burton, Traffic and Turning, chapter 2.

12 The text of several such ballads is reproduced in D. Vitkus (ed.), Three Turk Plays from Early Modern England (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), Appendix I. On historical pirates and literature, see: C. Jowitt, The Culture of Piracy, 1580–1630: Literature and Seaborne Crime (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010). On the circulation of news, see: U. McIlvenna, ‘When the News was Sung: Ballads as Media in Early Modern Europe’, Media History, 22:1–2 (2016), 317–33; E. Cecconi, ‘Comparing Seventeenth-century News Broadsides and Occasional News Pamphlets: Interrelatedness in News Reporting’, in A.H. Jucker (ed.), Early Modern English News Discourse (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2009), 137–58, and J. Raymond, Pamphlets and Pamphleteering in Early Modern Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), chapter 4.

13 See: C. Edelman, ‘Morose’s Fights at Sea in Epicoene’, Notes and Queries, 53:4 (2006), 516–19; P. Womack, ‘Off-stage’, in H. S. Turner, (ed.) Early Modern Theatricality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 71–92.

14 See: T. Marshall, Theatre and Empire: Great Britain on the London Stages under James VI and I (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), chapter 3.

15 On James’s anti-Islamic views, see: Dimmock, New Turkes, 200–1, and Bergeron, ‘Turks?’, 257–9.

16 On representations of Moors and Indians in mayoral pageants, see: Chew, Crescent 463–8, and A.G. Barthelemy, Black Face Maligned Race: The Representation of Blacks in English Drama from Shakespeare to Southerne (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987), chapter 3.

17 For a notable exception (inspired by the 1610 sea-fight) see pp. 6–7 above.

18 On the journey by water, see: R. Strong, Henry Prince of Wales and England’s Lost Renaissance (London: Pimlico, 2000), 115–16. Samuel Daniel’s masque, Tethys Festival, was another marine-themed investiture entertainment (STC 13161).

19 The celebrations were made possible by a loan of £100,000 from the City of London, secured at the end of April. See: D. M. Bergeron, ‘Creating Entertainments for Prince Henry’s Creation (1610)’, Comparative Drama, 42:4 (2008), 435.

20 Early modern usage of i/j and u/v has been regularised silently in quotations throughout. The place of publication is London unless otherwise indicated. Short Title Catalogue citations refer to the second edition of A Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland and Ireland, and of English Books Printed Abroad 1475–1640 (London: Bibliographical Society, 1976).

21 Signature references to primary works are provided in the main body of the article throughout.

22 Munday does not provide a clear reason: ‘whether by the violent storme of rayne, or other appointment of his majestie, I knowe not’ (D2r).

23 Bergeron, ‘Turks’, 263; Strong, Lost Renaissance, 121. In his edition of Pageants and Entertainments of Anthony Munday (New York: Garland, 1985), 48, Bergeron glosses the word: ‘a large ship, especially of war (OED). Though the dictionary does not attest this meaning until 1642, that seems to be what Munday had in mind’. The OED notes mid-sixteenth-century usage of ‘Castle, n. 7. Nautical. A tower of elevated structure on the deck of a ship’ in the sense of a ship’s ‘forecastle’, but there is nothing to suggest that the word was used metonymically in the early seventeenth century.

24 J. Stow and E. Howes, The Annales, or a generall chronicle of England, begun first by maister John Stow … and after him continued … by Edmond Howes (1615; STC 23338), 4G1r.

25 John Chamberlain to Alice Carleton, 4 January 1613, in N. E. McClure (ed.), The Letters of John Chamberlain, 2 vols (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939), vol 1, 416.

26 Crescent moons commonly feature on woodcuts depicting Islamic/Ottoman soldiers and ships: see STC 11029, STC 11359, STC 25022, and STC 25022.5.

27 For a more detailed description of the fireworks see: Stow and Howes, 4G1r.

28 An engraving of the naumachia on the Arno is reproduced in F. A. Dominguez, ‘Philip IV’s “Fiesta de Aranjuez”, Part I: The Marriage of Cosimo II de Medici to María Magdalena de Austria and Leonor Pimentel’, Hispaniófila, 157 (2009), 39–62 (44). On Harrington’s report see Strong, Lost Renaissance, 100.

29 Chruso-thriambos. The Triumphes of Golde (1611, STC 18267), A3v. Records do not provide specific details about the number or types of vessels used; see: J. Robertson and D. J. Gordon (eds.), A Calendar of Dramatic Records in the Books of the Livery Companies of London, 1485–1640 (Oxford: Malone Society, 1954), 73–74

30 The surviving texts of these entertainments, together with a list of celebratory poems and ballads, are reproduced in J. Nichols (ed.), The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First (London: 1823), vol. 2, 527–626.

31 D. M. Bergeron, ‘Stuart Civic Pageants and Textual Performance’, Renaissance Quarterly, 51:1 (1998), 163–83.

32 Bergeron, ‘Textual Performance’, 164–5.

33 W. Perrin (ed.), The Autobiography of Phineas Pett (London: Navy Records Society, 1918), 103. The Spy was built in 1586 and was part for the fleet that sailed against the Armada. See: W. L. Clowes, The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present (London: Low, Marston & Co, 1897), 423, 425, 588–9.

34 See also Stow and Howes, 4H2r.

35 On firework castles, see: S. Werrett, Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 19–20.

36 Chamberlain remarks in early February that ‘above five hundred watermen [are] alredy pressed, and a thousand musketters of the trained bands in the shires hereabout made redy for this service’ (see: McClure, Letters, 416, 421). An abstract or brief declaration of the present state of his Majesties revenew (1651; Wing A148), B*3, notes that funds were granted to Robert Mansell for the ‘Navall Fight’ and fireworks.

37 McClure, Letters, 421.

38 Perrin, Autobiography, 102.

39 Ibid.

40 The naming of the miniature ship as the Disdain might have been in homage to the Lord Admiral’s pinnace of the same name, which was built in 1585 and played a part in England’s defence against the Spanish Armada (see Clowes, Royal Navy, 564, 581, n., 593). It seems unlikely that Pett refers here to the old pinnace, since his mention of the Spy specifically identifies it as ‘old’ and belonging to the Admiral, while no such comment is made about the Disdain. See note 33 above.

41 See Perrin, Autobiography, 22–23, and Nichols, Progresses, vol. 1, 425, for accounts of the ship’s first excursion. See Strong, Lost Renaissance, 35–38, on Henry and Pett’s relationship.

42 Strong suggests that ‘Flickers of the dead Prince of Wales’s vision perhaps survive in the naval battle of the Thames’ (Lost Renaissance, 137).

43 Bergeron, ‘Turks’. See also: M.-C. Canova Green, ‘Lepanto Revisited: Water-fights and the Turkish Threat in Early Modern Europe (1571–1656), in Waterborne Pageants, 177–98 (but note that the author mistakenly conflates accounts of the 1610 and 1613 events).

44 The poem was first published in His Majesties Poeticall Exercises at vacant houres (Edinburgh, 1591; STC 14379) and then as His Majesties Lepanto, or, Heroicall song (1603; STC 14379.3).

45 There is also confusion about some of the ships: where Taylor and Pett talk about the ‘Venetian Argosy’, the Venetian vessel is here identified as a ‘carvelle’, and the ‘Argosy or Galliaza, seemed to be of Spaine’ (A4v).

46 McClure, Letters, 423.

47 See: Heavens Blessing, B1r-C2v.

48 McClure, Letters, 423.

49 Perrin, Autobiography, 103.

50 Bergeron, ‘Turks’, 237.

51 See: A. Fowler, The Mind of the Book: Pictorial Title Pages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 1–54.

52 J. A. Knapp, ‘The Bastard Art: Woodcut Illustration in Sixteenth-Century England’, in D. A. Brooks (ed.), Printing and Parenting in Early Modern England (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), 151–72.

53 C. Marsh, ‘A Woodcut and Its Wanderings in Seventeenth-Century England’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 79:2 (2016), 245–62.

54 Ibid., 246.

55 L. Razzal, ‘“Like to a title leaf”: Surface, Face, and Material Text in Early Modern England’, Journal of the Northern Renaissance, 8 (2017), para. 5, 6. <https://www.northernrenaissance.org/like-to-a-title-leafe-surface-face-and-material-text-in-early-modern-england/> [accessed 10 July 2020].

56 The first edition of The Magnificent Marriage (STC 11358) uses a ‘large woodcut, knight and squire on horse-back posed for tilting’. W. Jackson and E. Unger (eds.), The Carl H. Pforzheimer Library: English Literature 1475–1700 (Newcastle, DE: Oak Knoll, 1997), 373. The second edition (STC 11359) uses a different illustration that broadly privileges the ‘Turk’ but not the maritime content of the sea-fight; it is a ‘crusade’ image, where a group of turbaned soldiers bearing crescent moons on their shields clash with a presumably Christian faction.

57 M. B. Saenger, ‘The Birth of Advertising’, in Brooks, Printing, 197–219. Saenger’s discussion focuses on title pages proper rather than the type of illustrated initial leaf I am describing, but the general concept holds true.

58 R. S. Luborsky and E. M. Ingram, A Guide to English Illustrated Books, 1536–1603, 2 vols (Tempe: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1999), vol. 1, 103–13.

59 See: Royal Museums Greenwich online catalogue Object ID SEC0239 and SEC0243. Thomas Cockson’s engraving of Howard exists in at least two states. See British Museum Collections Online: items 1912,0709.17 (c.1599) and 1849,0315.9 (c.1599–1602).

60 See STC 21546, STC 21546.5 and STC 20891. The attractiveness to printers of a ship woodcut with the arms of the Lord Admiral is further attested by a cruder, reversed adaptation of this woodcut (identified as Type 5 by Luborsky and Ingram), which was similarly used on maritime news pamphlets and navigation manuals.

61 On the role of illustrations and title page marketing, see: P. J. Voss, ‘Books for Sale: Advertising and Patronage in Late Elizabethan England’, Sixteenth Century Journal, 29:3 (1998), 733–56 (especially 737–43).

62 Knapp, ‘Bastard Art’, 152.

63 S. Werner, Studying Early Printed Books, 1450–1800: A Practical Guide (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2019), 83.

64 Allde himself had printed numerous editions of The Safegard of Sailers that variously used the Type 7 and Type 8 ship woodcuts on the title page before 1613 (1587, STC 21546; 1590, STC 21546.5 and STC 21547; 1605, STC 21549; 1612, STC 21550).

65 Both of the pamphlets use a large woodcut of an English ship facing a Turkish ship with two bodies hanging from the foremast, which was most likely created especially for this publication. See: K. Sisneros, ‘Early Modern Memes: The Reuse and Recycling of Woodcuts in 17th Century English Popular Print’, The Public Domain Review, 6 June 2018 <https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/early-modern-memes-the-reuse-and-recycling-of-woodcuts-in-17th-century-english-popular-print> [accessed 13 August 2020].