Abstract

The Group of Eight Countries (G8) launched the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition to improve nutritional outcomes through private sector involvement in agricultural development. The accession of Malawi to the Alliance reveals the assumptions behind the intervention. We show that while the New Alliance may seem to have little to do with nutrition, its emergence as a frame for the privatization of food and agriculture has been decades in the making, and is best understood as an outcome of a project of nutritionism. To highlight the failings of the approach, we present findings from the Soils, Food and Healthy Communities Initiative in northern Malawi, which has demonstrated success in combatting malnutrition through a combination of agroecological farming practices, community mobilization, women's empowerment and changes in intrahousehold gender dynamics. Contrasting a political economic analysis of the New Alliance alongside that of the Soils, Food and Healthy Communities Initiative shows the difference between a concern with the gendered social context of malnutrition, and nutritionism. We conclude with an analysis of the ways that nutrition can play a part in interventions that are inimical, or conducive, to freedom.

I. The New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition

Following the recession and food price inflation of 2007–2008, the number of malnourished people topped 1 billion.Footnote1 In 2009, at the Group of Eight Countries (G8)Footnote2 summit in L'Aquila, Italy, the world's richest countries pledged USD 22 billion over 3 years to address hunger. Four years later, half the pledges had materialized (Henriques Citation2013). In the intervening period, the G8 had developed new policies through which hunger might be managed. The New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition was unveiled under the US presidency of the G8 in May 2012 (The White House Citation2013). This late entry into the post-2008 ledger of international commitments to tackle hunger was remarkable for its shift away from pledges centred on government intervention, and its turn toward the private sector as the remedy to both chronic and acute hunger and malnutrition. Six countries were included in the New Alliance's first round of partnerships – Ghana, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Cote D'Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Mozambique – in an effort to ‘lift 50 million people in sub-Saharan Africa out of poverty in the next 10 years by supporting agricultural development’ (USAID Citation2013b).

Bearing the hallmark not only of the Obama administration, but of politics within the G8 more broadly, the New Alliance was built around a governance model of public–private partnerships (Allcott, Lederman, and López Citation2006). Often, the private sector took the lead in drafting policy. The frameworks for the agricultural component of the New Alliance come from documents like the World Economic Forum's Achieving the new vision for agriculture: new models for action (World Economic Forum Citation2013).Footnote3 These documents in turn emerge from the collaborative processes between the private sector, philanthropy and donor agencies that have advocated a shift towards ‘creative capitalism’ in the agricultural sector in the Global South (Kinsley, Clarke, and Banerjee Citation2008; Curtis and Hilary Citation2012; Koopman Citation2012).

Those commentators who see in the New Alliance the shaping of development policy by the needs of transnational capital are not wrong (Holt-Gimenez Citation2013; Sulle and Hall Citation2013; War on Want Citation2013; Murphy Citation2014). In this paper, we advance the analysis of food policy by asking how manifestos for private sector agricultural capitalism have become policy vehicles for ending hunger. By locating the policy manoeuvres behind the New Alliance in thinking that emerges in a moment of free-market triumphalism at the end of the Cold War, we are able to point to a logic of ‘nutritionism’ – understood as a set of ideas and practices that seek to end hunger not by directly addressing poverty but by prioritizing the delivery of individual molecular components of food to those lacking them – that propels the New Alliance forward. The way nutritionism comes to matter, however, is not through the battering ram of aid, or by imperial decree. The idea of nutritionism does not float freely (Risse-Kappen Citation1994). It is articulated with the possibility of material shifts in ways to control land and state resources within both the Global North and the Global South. We provide an analysis that complicates a facile reading of the New Alliance as a pure imposition of foreign capital's will on a naïve or helpless local democracy.

Second, given the pervasion of nutritionism through development policy, we explore the question of whether there are ways of recuperating the basic ideas of nutrition to address human health without succumbing to nutritionism. In asking this question, we do not dismiss the fact that the main reason for malnutrition is poverty, disenfranchisement, exploitation and marginalization. We do, however, think it worth asking whether it is possible for any approach for ending hunger to use the term ‘nutrition’ without being co-opted by a discourse that would speak of malnutrition in the absence of politics. To do that, we examine the New Alliance alongside an initiative in northern Malawi, the Recipe Days of an organization named ‘Soils, Food and Healthy Communities’, which offers an antidote to orthodox development policy, while signalling a politics that, we argue, breaks with some of the deeper tenets of the New Alliance.

Let us turn first to the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition. The ‘win–win’ policy approach lauded at the time of the Alliance's launch was celebrated as a form of ‘enlightened capitalism’ (White Citation2013). The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) reminded the world that ‘Africa's economic growth, with agriculture as a strong driver, is creating substantial new business opportunities, and the rate of return on foreign investment in Africa is higher than in any other developing region’ (USAID Citation2013a). The Alliance's goal was to harness this growth to the service of economic growth and, thereby, a reduction in hunger and malnutrition.

Raj Shah – the Administrator for USAID who birthed the New Alliance through his organization – argued for the vital importance of the private sector in agricultural development with these words: ‘We are never going to end hunger in Africa without private investment. There are things that only companies can do, like building silos for storage and developing seeds and fertilizers' (Shah quoted in Strom Citation2012).

In the original Green Revolution, silos, agricultural research and fertilizer distribution were often the domain of the public sector, as were the subsidies and public infrastructure necessary to sustain grain storage, marketing and agricultural extension (Perkins Citation1997; Ross Citation1998; Cullather Citation2010; Patel Citation2013). Silos have been built, seeds developed and fertilizers used in the past without multinational corporations. When Raj Shah suggests that it is impossible to eradicate hunger without transnational capital, the statement must be parsed not as a reflection of historical truth, nor as a logical impossibility, but as an attempt to create a twenty-first century political necessity.

Shah's historical revision, in which transnational corporations became indispensable, swiftly led to the criticism that the New Alliance was an attempt by G8 countries to impose the will of favoured private-sector entities onto African countries. In a bid to pre-empt the accusation, the New Alliance made clear that it operated by ‘mobilizing private capital, taking innovation to scale, managing risk’ (USAID Citation2013b), by building on existing country development plans. Such plans could be found in the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP).Footnote4 By articulating the New Alliance with previous endogenous efforts to increase the involvement of the private sector in agriculture, the New Alliance is able to imply that African governments have already accepted the premises of its intervention.

Debates about whether increased agricultural private investment improves food security for the poor are, however, far from resolved (Bezner Kerr et al. Citation2012; McMichael Citation2013; Wood et al. Citation2013). The New Alliance doesn't seem to read McMichael, but rather insists on the impossibility of ending hunger without the assistance of the international private sector. Through this stifling of debate about the merits of the private sector, it appears as if international capital is imposing its will upon benighted Africans (Holt-Giménez Citation2008; Holt-Gimenez, Altieri, and Rosset Citation2008; Bellwood-Howard Citation2014). It isn't wrong to see the New Alliance as the G8's latest attempt to spear-carry for the international agrofood industry, but it is important to take seriously the New Alliance's assertion that in bringing neoliberal market forces and international corporations to agriculture, it is only doing to African countries what they have chosen to do to themselves. It is hard to do interpretive work simply by presenting the New Alliance as an imperial fiat. To do so robs African governments, private sector and people of any agency. Better, it helps to think of the Alliance's mode of public–private partnership as involving the configuration of a particular hegemonic bloc, and relations to the means of production (Anderson Citation1977; Gramsci and Buttigieg Citation1992; Gill and Law Citation1993). The idea of a historic bloc – led by a bourgeoisie making alliances and compromises, and using coercion and consent to maintain hegemony – prompts us to examine African countries’ responses and motivations in accepting the New Alliance.

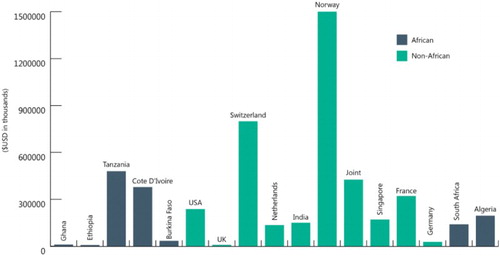

We can see both the membership of the bloc, and its constitution, by observing that the Alliance has resources that have been lacking in the transformation of African agriculture. New Alliance donors’ commitments total a little under half a billion US dollars over 3 years ().

Table 1. Development partners for the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition.

That Norway should be such a substantial donor to the initiative may at first appear mysterious, but becomes clearer when one examines the provenance of the corporations that form part of the New Alliance ().

Figure 1. Total investment of companies in the New Alliance by country of origin. Source: Hong and ONE (Citation2014).

Business and Northern governments aren't alone in this bloc. They are joined both by philanthropic and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Indeed, the NGO ‘ONE' authored to defend the Alliance against charges that it was a vehicle for large-scale agribusiness from the Global North to take over Africa. Conceding that the largest single donor was the Norwegian fertilizer corporation Yara (with initial commitments in 2012 at USD 1.5 billion), followed by Swiss seed giant Syngenta (USD 500 million), ONE offered that a Tanzanian company had ‘sizeable investments’, pointing to the Tanzanian company Agro EcoEnergy's USD 425-million commitment. Unfortunately, closer scrutiny reveals the Tanzanian company to be an offshoot of a Swedish group that has been involved in conflict with local smallholders over its need for large areas of farmland on which to grow crops for biofuels (Locher and Sulle Citation2013; Widgren Citation2014).Footnote5 These figures point unambiguously to the kind of agriculture envisioned by the New Alliance: large scale, export driven, chemically intensive, centralized knowledge and expertise in the (mainly foreign) private sector.

Yet the Alliance's bloc also involves ‘local partners’. In every country in which the Alliance is forged, a country cooperation framework has been drafted. In this paper, we examine the case of Malawi, and use the Country Cooperation Framework, together with interviews with key stakeholders, as the basis of the analysis in this section (New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition Citation2013). Malawi was a later arrival to the New Alliance, with the signing of its commitments announced under the UK's chair of the G8 at a hunger summit in June 2013. Malawi is an appropriate candidate for initiatives to tackle hunger and malnutrition (UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Citation2013). The choice by then-President Joyce Banda to commit Malawi to the alliance may, however, have had less to do with the Alliance's capacity to eradicate stunting, or indeed halve it in 10 years, as Banda hoped (Banda Citation2013), than with Malawi's recent International Monetary Fund (IMF)-encouraged currency devaluation and need for foreign direct investment to offset balance-of-payments issues. The formation of hegemonic blocs is characterized by both consensual and coercive behaviour – the latter term being particularly appropriate in describing the relationship between the government of Malawi and the donor community in the setting of domestic monetary policy. Indeed, as Attwell (Citation2013) suggests, the relationships that make contingent future loans (and current creditworthiness) on the kind of spending that is possible within the domestic sphere have vital impacts. They flow through monetary policy to shape the possibilities of responding to events such as famine and chronic hunger, such as Malawi experienced in the early 2000s (Devereux Citation2002).

The exigencies of foreign capital flows may explain the haste with which the government released a Country Cooperation Framework. After swift consultation with the private sector – though there were no meetings with civil society groups – and a mere three months after President Banda's London visit, the government of Malawi released its framework document (New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition Citation2013). The document contains the goals of different international donor agencies and the private sector, as well as undertakings by the government of Malawi, to meet partnership requirements under the Alliance. The Alliance announced that it will lift 1.7 million Malawians out of poverty by 2022. In order to do that, business, donors and government will work in concert. The government of Malawi's commitments are the most detailed and specific, and are headlined by the following ‘policy indicators’ to increase food security and reduce malnutrition. Those policy indicators, as found in the framework document, are:

Improved score on Doing Business Index to among top 100 economies

Increased dollar value of private sector investment in the agriculture sector and value added agro-processing

Increased private investment in commercial production, sale of inputs and produce and value addition (New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition Citation2013, 6)

These are the only metrics that appear in the New Alliance country document. They lack any explicit mention of nutrition or food security, which has led many commentators to observe that, at its heart, the New Alliance is really about neither. Such a view would be bolstered by a close reading of the private-sector commitments to the Alliance ().

Table 2. Declared private-sector commitments to agriculture in Malawi in the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition.

With US$51.7 million from Malawian registered companies and US$88 million from overseas, the partnership's umbrella covers substantial investments. These are not, however, new commitments, but ones that companies declared within their current plans of operation. Nonetheless, the scope is ambitious. The tobacco company Alliance One Tobacco (Malawi) Limited, a supplier to the global tobacco industry, has outlined specific plans in its 7-year plan which, in addition to growing more tobacco, include:

to harvest 300,000 metric tonnes of maize (currently 36,000 metric tonnes), 145,000 metric tonnes of soya (currently 1600 metric tonnes), 40,000 metric tonnes of flue-cured tobacco (currently 6800 metric tonnes), and 90,000 metric tonnes of burley tobacco (currently 50,000 metric tonnes). This will require an increase in related employment from 71,000 (current) to 181,000 (end-state) as well as an increase in land utilized in production from 61,000 hectares (current) to 181,000 hectares (end-state). (New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition Citation2013, 21)

The composition of the local partners in the New Alliance's bloc points to the extent to which there has been a genuine endogenous component to the push toward privatized and export-driven agriculture. President Banda initiated a policy in 2012 with the goals of promoting pigeon pea, groundnuts and soya beans for export, and liberalizing the domestic seed market. The firms involved in that initiative overlap with the New Alliance partners, with the further addition of tobacco and processing firms.

There is, indeed, a rich history in which the Malawian government has found its interests aligned with certain elements of its private sector and foreign interests, above those of its poorer citizens. Malawi's first president, Hastings Banda, initiated land reform that did little to address historically inequitable land disparities between peasants living on customary land, private-sector land holdings and government holdings:

Between 1967 and 1994, for example, more than 1 million hectares of customary land [out of under 8 million] were lost to private and public land … None of the reforms of 1967 addressed the legacy of landlessness and land hunger bequeathed by colonial land policy. (Kanyongolo Citation2005, 124).

It is onto customary and – to a lesser extent – public land that private sector holdings will expand under the New Alliance.

Although ostensibly different, the Malawian public and private sectors have increasingly found themselves intertwined. The Cashgate scandal that ended the administration of President Joyce Banda (unrelated to Hastings Banda) saw the country defrauded of 1 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) – US$32 million – through government contracts with private-sector firms for which no services were provided, or for which costs were inflated (Economist Citation2014).

In defence of the Alliance, one might argue that the push toward export agriculture is one that generates increased employment, and thereby generates food security. This argument has to contend with the lower labour requirements of export agriculture, the consistently low wages and poor working conditions of agricultural workers (UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Citation2013), and the opportunity cost of high-quality land set aside for export rather than domestic food production. Insofar as changes in Malawi's agriculture have, arguably, produced welfare benefits, they have come not through export agriculture but through increased food production (Beck, Mussa, and Pauw Citation2013; Chirwa and Dorward Citation2013).

In order for these investments to succeed, however, the government is required to do its part to provide a business-friendly environment and, in particular, to liberalize land purchasing arrangements (Chinsinga, Chasukwa, and Zuka Citation2013). Attempts by Parliament to pass a land bill that might do this foundered in 2012, over the objections of chiefs and civil society. Chiefs were concerned with the loss of their traditional authority to manage land (Chinele Citation2014), while civil society groups were concerned about the dynamics encouraged by the legislation that would disenfranchize women (see Peters and Kambewa Citation2007 on gendered land tenure arrangements in central and southern Malawi). The legislation, passed by Parliament, currently sits with the President, recently elected following highly contentious elections in May 2014. Land reform has not been named as a high priority by the new government.

In some ways, the New Alliance is not something new; policies which are private-sector friendly have recent precedent – the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), together with USAID, has long been pushing for mechanisms to disseminate agricultural technologies through the private sector (Holt-Giménez Citation2008; Holt-Gimenez, Altieri, and Rosset Citation2008; Patel, Holt Giménez, and Shattuck Citation2009). Such dissemination might once have been the purview of the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (MoAFS). With decades of donor pressure to reduce government expenditure and domestic choices to spend the majority of the MoAFS budget on fertilizer subsidies, the extension service has suffered. In 1996–1998, for instance, government extension services were responsible for 67 percent of the Ministry of Agriculture's budget. Today, that figure is 7 percent, and there is a 60 percent vacancy rate for extension workers (International Food Security Network Citation2011). The private sector can handily make the case that the Malawian extension service is underfunded, and unsuited to the task of disseminating new technologies. Into the void left by the extension service, USAID and AGRA have supported agrodealership networks that have effectively privatized agricultural extension services and displaced services provided by the state Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation (ADMARC), the public grain marketing board. So successful has the sweep of the public by the private sector been that one local Monsanto executive credited the entirety of his company's sales to small-scale agrodealers (Curtis and Hilary Citation2012). It is possible to be critical of the corruption within government, from Cashgate to improprieties at ADMARC (Tambulasi Citation2009) to fictional data produced by the Ministry of Agriculture, while thinking that a robust public institution might function more in the public interest than the private sector is inclined to behave.

Despite research pointing to the benefits of public extension services over the subsidy of private sector inputs (Allcott, Lederman, and López Citation2006; Blanco Armas, Gomez Osorio, and Moreno-Dodson Citation2010), the government is being urged to hand its agricultural policy to the market. Footnote6 One needn't romanticize the public sector. As Bezner Kerr (Citation2013) notes, extension services have long been harnessed to overseas purposes. Likewise, abandoning of the state as delivery mechanism does not mean an end to the state's role in the process of disseminating a particular model of agriculture. The profits of such activity have merely been privatized. The costs, as we shall see, remain in the public domain. What is new here are the ways that such activity has restructured state–society relations under capital, under the aegis of preserving life. In ways that are historically novel, the relations to means of production are mediated and redistributed because they may lead to better nutritional outcomes.

II. Understanding what role ‘food security and nutrition’ play in the New Alliance

To castigate the New Alliance as having little to do with either food security or nutrition is to miss the political work that has happened around these terms under neoliberalism. They function as more than simply an alibi for accumulation by dispossession. The notion of a historic bloc involves not just a bricolage of comprador interests – domestic and international – but cultural intervention as an inextricable part of the maintenance and furthering of hegemony. ‘Development’ as project and process has long been part of that vocabulary of hegemony. Recent work by Scrinis (Citation2013) and Kimura (Citation2013) helps interpret new uses of the term ‘nutrition’. The clearest articulation of these new uses can be found in the World Bank's (Citation1994) publication Enriching lives: overcoming vitamin and mineral malnutrition in developing countries, which laid the ground for interventions well matched to the private sector. We explore these ideas at some length in this section because they are likely to be unfamiliar to many readers, and are only likely to become more significant in international development discourse. It is worth understanding why, and why it is dangerous.

Scrinis defines nutritionism as

a reductive focus on the nutrient composition of foods as the means for understanding their healthfulness, as well as by a reductive interpretation of the role of these nutrients in bodily health. A key feature of this reductive interpretation of nutrients is that in some instances … it conceals or overrides concerns with the production and processing quality of a food and its ingredients. (Scrinis Citation2013, 16–17)

Kimura (Citation2013) advances this by helping to identify how specific nutrients achieve prominence in the minds of policy makers. Describing these ‘charismatic nutrients’, she argues that ‘the charisma of nutrients cannot be fully captured by their “scientific” values, but rather, depends on sociopolitical networks built around them’ (Kimura Citation2013, 575–76). We suggest that a nutritionism focus aligns well with the productivist emphasis in agriculture, which emphasizes food quantity over all other qualities, regardless of concerns about how food is produced, by whom, and who has access to that food – in other words, the ecological implications and the social–political networks surrounding food and agriculture.

Nutritionism is clear in the case of the Malawian government's emphasis on iodine through fortifying salt under the Scaling Up Nutrition initiative.Footnote7 Iodine deficiency is a serious issue. Two billion people are iodine deficient according to the World Health Organization, and mandatory salt iodization programs have had success in addressing the health effects of inadequate intake (Zimmermann Citation2004). Natural sources are associated with coastal diets – seafood and kelp are naturally high in the mineral, but it is also present in dairy, eggs and certain legumes (Higdon Citation2014). There are also high levels of vitamin A and iron deficiencies, particularly in preschool children of whom 60 percent have subclinical vitamin A deficiencies, and among whom 80 percent suffer anaemia. Severe developmental difficulties associated with iodine deficiencies are around 1 percent (Government of Malawi Citation2009, 9).

The Malawian government has not, however, committed to ensuring a diet rich in foods which address these deficiencies. Such a course might require, according to the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, addressing low peasant access to land, currently estimated at 0.5 ha/person in a country with rising inequalities (Chinsinga and Chasukwa Citation2012; UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Citation2013). Improving dietary quality might also involve increasing the minimum wage, currently estimated at one of the lowest in the world, and improving primary education, to help children and their caregivers understand basic nutrition science (De Schutter 2013).

Instead, the emphasis of the Malawi government is on fortifying salt with iodine. Other things being equal, this is more sensible than not iodizing salt, but as a policy, it fails to address other nutritional deficiencies or the structural issues that lead to high rates of child mortality and persistent child stunting. The prioritization of iodine deserves an explanation. Part of it can be traced to the model of thinking about nutrition not as a precondition for a healthy life, but as an investment. A rational calculus of nutrition spending can be found in the World Bank's Enriching Lives, in which it observes that ‘deficiencies of just vitamin A, iodine, and iron … could waste as much as 5 percent of gross domestic product, but addressing them comprehensively and sustainably would cost less than 0.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP)’ (World Bank Citation1994, 7). If one is inured to the instrumentalization necessary to understand nutrition in this way, if one is able to suspend questions about poverty and poor peoples’ access to healthy food on their own terms, this becomes a powerful call.

In food multinationals, the World Bank found willing responders to such a call, who heard in the language of investment the opportunity to tweak their products, expand their ranges and find new customers who had been encouraged by their governments to buy, not grow, food sprinkled with charismatic nutrients. The Business Alliance for Food Fortification (BAFF) was convened by the World Bank and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition. Over 150 companies attended, and at their first meeting in China in 2005, ‘Coca-Cola, Danone and Unilever agreed to become the first co-chairs of the BAFF’ (BAFF Citation2014, 2). Members of the private sector saw themselves as well positioned to contribute to the effort to eradicate malnutrition. ‘Companies already own the right technology to make a difference as well as the distribution channels and communication networks’, BAFF explained (Citation2014, 1).

The economic calculus presented to the business community also possessed a logic irresistible to governments. Again, the language of investment resonated particularly with those governments struggling with high levels of debt, and with scarce resources for a more comprehensive nutrition policy. Fifteen years later, in the Malawian government's National Nutrition Policy and Strategic Plan (2007–2011), the government used the language of investment, losses and economic returns to frame their nutritional intervention:

In Malawi, it is estimated that due to mental impairment caused by iodine deficiency, the present value of lost future wages over ten years (2006–2015) could amount to US$71 million. Reduced physical capacity in stunted adults would contribute to a loss of future economic production of US$207 million for every 1% reduction in height is equivalent to 1.3% loss in productivity (in present value terms)…The translation is that for every US$1 Malawi invests in nutrition, there is a US$5.3 gain in productivity and therefore Malawi would gain US$1.7 billion in the same 10 years period (2006–2015). (Government of Malawi Citation2009, 12 emphasis in original)

Salt iodization is a great return on investment. As Kimura observes,

The procurement and distribution of supplements requires too many government resources or those of international organizations, and the execution is dependent on their capacity and commitment. In contrast, the argument goes, fortification is much more ‘efficient’ because it needs less government involvement. Fortification is also an ideal way to involve the private sector in the currently celebrated notion of ‘public-private partnership’. (Kimura Citation2013, 1247–1252)

Fortification has long been celebrated in nutrition, in part because of its simplicity. No change in distribution or education is required. Since people already consume sugar and salt, fortification is a simple way to increase micronutrient intake, as long as they can afford these foodstuffs. Lest it bear restatement, this isn't to argue that iodine deficiencies ought to be tolerated. Chronic iodine deficiency can lead to reduced mental facility, and pregnant women, in particular, need increased iodine (Zimmermann Citation2012). Such fortification, however, gilds a shift towards a diet higher in salt, fat and sugar that has led in the Global North (and increasingly in the Global South) to severe chronic health issues (Patel Citation2007; Guthman Citation2011). Further, following Kimura, the discourse of investment and return under nutritionism ‘critically shifts who can speak authoritatively about the food problem and who is listened to’ (Kimura Citation2013, 254–55). Further, it ‘creates a particular visibility for women – but not necessarily in a way that reduces their oppression and marginality. Discourses of nutritionism may highlight women's plight as the victims of micronutrient deficiencies, but only as biologically programmed ones’ (Kimura Citation2013, 320–22). Little attention is paid to the broader structural factors, such as poverty, low education, low wages or limited landholdings, that lead to undernutrition; instead, the medicine is just a spoonful of fortified sugar. In other words, rather than a central commitment to eradicate poverty, the covering logic of nutritionism commits to making exploitation survivable. With fortified flour, the exploited can carry on (LaGrone et al. Citation2012). This is the era of poverty with added vitamins.

This point brings us to the second intervention that the Malawian government hopes to achieve under its New Alliance commitments: the extension of maternity leave from eight weeks to an as-yet unspecified higher number, in order to increase the period of exclusive breast-feeding closer to the recommended six-month minimum. Yet, out of a total workforce of over 6 million, less than half a million work in formal-sector jobs covered by maternity leave, so only 10 percent of working women would be affected (ILO Citation2011).

The intervention flags ways in which the New Alliance is both a bourgeois project – and progressive for middle class women in the workplace – and yet careless toward the class condition of the majority of Malawi's reproductive labour, and women's labour in particular. It is a way for the state to answer the question ‘how can women be encouraged to breastfeed?’, yet to answer with bourgeois tools, unable and unwilling to do more than extend the time allotted by formal labour for reproductive labour. Nutritionism's emergence through the private sector helps explain the ways that the New Alliance can offer itself as a sincere attempt to combat malnutrition, at the same time as building public–private partnerships in other parts of value chains (McMichael Citation2013). This is how the arrival of foreign multinationals in search of resources for low-cost agro-export and for new customers (for fertilizer and fortified foods, for example) becomes compatible with the sainted goal of ending hunger.

We have intentionally taken longer in this section to explore these issues, not only because of their novelty but also to lay a foundation for exploring exactly how, through the development of new contradictions of class, gender and traditional relations, the New Alliance reconfigures a historic bloc. What is suppressed through this hegemony is the possibility of alternative ways of addressing hunger. The eradication of poverty (Atinmo et al. Citation2009), the provision of livelihood support and opportunity (Devereux et al. Citation2006), the funding of basic services in order to provide support to mothers (Pandolfelli, Shandra, and Tyagi Citation2014) – all of these are policy goals undermined by the emphasis on private-sector solutions to public problems. Struggles against neoliberalism in Malawi, whether around land (Kanyongolo Citation2005), seeds (Bezner Kerr Citation2013) or healthcare (Bezner Kerr and Mkandawire Citation2012), are ongoing and important. We want, however, to turn to a project that looks at an important – and often overlooked – site of resistance to the formation of the hegemonic bloc: the household.

As Bezner Kerr and Mkandawire (Citation2012) note, neoliberalism involves the presupposition of problematic ‘modern’ gender roles, particularly around the household. There are ways in which women are instrumentalized in dominant development practices and policies that militate against radical approaches to the creation of a diverse diet, ending poverty, women's empowerment, agroecological resilience and gender transformation. We turn now to such an example, to suggest ways that the New Alliance's modernity is being contested (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2011). It is a project that is in no way comparable to the scale of the New Alliance. It currently involves only about 10,000 farmers in Malawi – a small fraction of the millions in the country. Nonetheless, we offer it as a counterexample to the New Alliance not only because it has already been able to accomplish what the New Alliance only aspires to, but because it takes seriously a politics that stands opposed to nutritionism, to technocratic rule, to the discounting of women's knowledge or peer-to-peer networks, to the questioning of long-held hierarchies of power, a politics in which ideas of nutrition matter, but are subordinate to ideas of equality and democracy.

III. How to take food security and nutrition seriously – Recipe Days in Northern Malawi

That 60 percent of undernourished people are women or girls is widely accepted (WFP Citation2009; Patel Citation2012). It has long been understood that an unequal division of labour within the home contributes to these outcomes (Kabeer Citation1994), even though the precise mechanisms through which these operate are less well understood (Cafiero Citation2012).

The household is a space in which gender relations are produced and reproduced (Gibson-Graham Citation1996), in which labour is divided daily, in which the historical inequities in gender relations are made contemporary. Within the household, a central site of these performances is the kitchen, and the reproductive labour of preparing, cooking, serving and cleaning around mealtimes. Inequities in the division of labour – reproductive and otherwise – extend beyond the household. In Malawi, women are actively involved in agricultural work. A recent national survey indicated that women performed agricultural labour on 94 percent of all plots, while men undertook similar agricultural labour on 82 percent of all plots (NSO Citation2012). While the same survey did not report on household labour, small-scale studies indicate that women do the vast majority of household tasks, such as cooking, water collection and child care (Bezner Kerr Citation2005). The inequity around this division of labour is further compounded by the subsequent outcomes in nutrition. Care has been shown to be a crucial aspect of child nutritional outcomes (Ruel et al. Citation1999), and Malawi has had persistent high rates of child stunting, currently estimated at 48 percent nationally (NSO Citation2012).

A recent UN Human Development Report for Africa looks at resource control, and women's ownership of land in particular, as a potential locus for change (UNDP Citation2012). Yet the ability to access land is not the primary issue for women in northern Malawi. Access to land is through the patriarchal institution of village chiefs, rather than through the market. For women who are residents in good standing of a particular village, the generally observed rule is that a wife will farm her husband's land. Widowed or divorced women (about 20 percent of Northern households) more often gain access to farmland through male kin, such as fathers or brothers (Bezner Kerr Citation2005; NSO Citation2012).

An estimated 20 to 40 percent of households find themselves exhausting their food supplies before the harvest comes in. When this happens, casual labour in other peoples’ fields– ganyu – is a survival strategy (NSO Citation2012). Female-headed households are more likely to be dependent on ganyu to survive than male-headed households (Bezner Kerr Citation2005; Dimova et al. Citationforthcoming). By contrast, more equality in the home, observe Lemke et al. (Citation2003) in a rare and important examination of intra-household inequality, results in increased food security.

The Ekwendeni region of northern Malawi is characterized by high levels of gender inequality within food insecure families. In-depth interviews carried out in 1997 revealed stories of domestic violence, lack of control over household resources, heavy workloads, excessive alcohol use by husbands and hunger (Bezner Kerr Citation2005). At the same time, both women and men talked about the rising cost of fertilizer and the limited options available to farmers to improve their crop production.

The Soils, Food and Healthy Communities (SFHC) project began in 2000 as a response to these findings, a pilot project of Ekwendeni Hospital to test different sustainable agricultural techniques as a means to improve food security and, ultimately, child nutrition (Bezner Kerr and Chirwa Citation2004). Using a farmer participatory research approach, the project initially began in seven villages, in which 30 members of a ‘Farmer Research Team’ were selected by their communities.

The Farmer Research Team learned different ways that leguminous plant options, such as pigeon pea and groundnut, could be grown to both improve their soils and provide alternative nutritious food sources for their families.Footnote8 The farmers then tested these options on their own small experimental plots, taught fellow villagers interested in trying the legume options and, alongside hospital staff and outside researchers, measured the impact of these new agricultural practices on their food security and nutrition. Other villages approached the hospital requesting access to the legumes and techniques associated with them. Over time, thousands of farmers began to experiment with different legume options and expand the size of their legume fields (Bezner Kerr et al. Citation2007).

Farmers in Malawi have long experimented with new crops. As Carr notes:

Farmers … now supplement their diet with beans and pigeon peas from India, tomatoes and avocados from the Americas, rape from Europe, mangos, paw paws and guavas from Asia, the list goes on and on. It is in fact difficult today to find farmers who are growing any indigenous plants and the countryside is dominated by crops which were introduced from other continents in comparatively recent times. This completely undermines the assumption, so widely proclaimed, that Malawian smallholders are extremely conservative in both their farming and eating habits. In reality they have welcomed and adopted a whole range of new crops and exotic foods without any outside pressure. (Carr Citation2004, 13)

The SFHC project built on this willingness to experiment with a social system for transmitting and sharing knowledge equitably and freely. In creating spaces and processes in which women and men might consider one another equal in skill, entitlement to speak and as bearers of knowledge, something new emerged. While gender had been a consideration by project staff from the start of the project, a participatory workshop held in 2003 proved a pivotal moment for raising key gender dynamics that worked against improved household food security and child nutrition. The workshop included various groups from communities, both older and younger women, highly food-insecure farmers and Farmer Research Team members as well as hospital staff, the second author and other researchers.

Across a range of presentations – ranging from factual to dramatic in form – farmer participants highlighted the challenges faced in their homes. Women complained that in some cases, the new cropping patterns resulted in an increased workload. Increased food availability of nutritious crops such as groundnuts, pigeon pea and soya beans did not necessarily result in improved nutritional benefits. Women reported that men would often take these crops, sell them, and use the revenue to purchase alcohol, or other uses not of benefit to the household.

Active discussions at that workshop led to the formation of a ‘Nutrition Research Team’ of 35 farmers, both men and women, to address issues raised in the workshop. This team was mandated to focus on four major nutrition themes identified through previous research by the project: exclusive breastfeeding, dietary diversification, frequent feeding of young children, and ‘family cooperation’, which included addressing unequal gender relations. Initially, each village team conducted home visits to families who had highly malnourished children. These home visits included demonstrations of recipes, and the presentation of ideas about how their children's diet might improve. In a meeting 2 years later, however, the team admitted that often men did not participate in these visits, and that participants had reported limited benefits from the home visits.

The idea of ‘Recipe Days’ emerged as an iterative improvement to the experiences of the home visits. Discussions between project staff, researchers and the Farmer Research Team about how to address child malnutrition, food insecurity and gender inequality – particularly around the division of household labour and decision-making – suggested that a one-on-one didactic approach hadn't been successful, and that a more collective, public and enjoyable approach might work better. Recipe Days were born out of this impetus.

The first Recipe Day was a somewhat modest affair. About 20 people attended, of whom a handful were men, mainly members of the Farmer Research Team. The women did the majority of the cooking and took charge of explaining recipes. Men's participation was intermittent and awkward, uncomfortable in their transgressing a gender role as they pounded soya, sieved flour and stirred various dishes (). A small number of recipes were made and then displayed and discussed by the participants. A week later, a technical workshop was held to discuss nutrition education, during which there was a brainstorming session about the way forward. Village teams decided to have community meetings with both men and women present, where different dishes would be prepared, discussed and then eaten, and gender issues would be raised. This approach would address questions of nutrition, provide a public and collective forum for the discussion of gender – and make it possible to have in public the kinds of discussion around the distribution of household work that had remained a private domestic matter.

Recipe Days continued, characterized by collective cooking, sharing of recipes, eating and discussion. At first they were organized by the Nutrition Research Team and then, after this team had dissolved in 2005, they were organized by staff and the Farmer Research Team. Over time, the size, participation by men and experience of Recipe Days changed. More and more men began to attend, often making up half of the participants. Their active participation in pounding, cooking and then presenting the dishes to the group also became an increasingly prominent feature of these events. The experiences became livelier, with more joking, laughter and tasting the food during cooking ().

Figure 3. Paul Nkhonjera cooking with other farmers looking on, 8 August 2009. Source: Rachel Bezner Kerr.

In-depth interviews about the project impact revealed that the recipes learned during the Recipe Days, and the shared experience of cooking together, were deeply appreciated by participating farmers:

Whenever our children were sick or malnourished we would take them to the hospital where they were receiving likuni phala [soy and maize flour to make porridge]; I did not know it was the same soya which we grow or we can grow and harvest ourselves. The new way of cooking which we have learnt from SFHC has made our families so special because our children feel as if we have just ordered the food from somewhere because of the way the food tastes and looks and so good.

(Middle-aged man, in-depth evaluation interview 18, 2009)

[Have you noticed any change in gender relations in your home since joining the project?] They've changed so much. Like now I'm here at the clinic, maybe my wife is here at the garden, so when I go home, I cannot sit and wait for her. I can prepare a meal, eat my share, and when she gets back she can eat. I cook nice meals! My last-born son is 15 years, he also cooks and helps at home.

Before the project I'd say ‘I want you to go the wells and draw three buckets of water, and then do this and this.' I was in charge. I appreciate that life has changed, it is no longer what it was in the past. God has also helped. Not many people can know why someone would change like this. Even my son is happy.

It is not like a one man's show in my family. Sometimes my wife says ‘I'm not feeling well’, maybe I do heavier jobs, and she does lighter jobs.

The project has grown from a handful of farmers to hundreds and now thousands in the region experimenting with different sustainable agricultural techniques (Bezner Kerr et al. Citation2012). Alongside the agricultural experimentation has been active organizing around recipes and nutrition education. In 2012, there were about 10 Recipe Days organized, some by the project staff and some by community members, with a range of between 25 and 100 adults in attendance at any Recipe Day, alongside often an equal or greater number of children. Over 1000 men and women have attended Recipe Days in the region in the past 3 years (SFHC Citation2012). Some of the Recipe Days have a specific ‘theme’ such as sharing recipes for a particular crop, or recipes that are useful during the period of food shortages. Others are organized to welcome visitors and showcase the work that farmers have achieved. In 48 in-depth evaluation interviews conducted in 2012 about the project, in which people were asked what significant changes they had experienced after joining the project, learning new recipes was a common theme, and, interestingly, over three quarters of those interviewed talked about having a more equitable division of labour and decision-making in their households. As one 31-year-old woman noted, when asked if there had been any significant changes in her household since she joined the project:

Sharing of household resources, decision-making: we share in every work, and we women even have time to rest. Before I had to work all day, there was no time for me to rest. Even decisions are [now] made by the two of us. (Evaluation interview 48, October 2012)

Others talked specifically about the changes in cooking that they experienced as a result of the project, such as this young woman:

Like in food preparation my husband can cook nsima [maize porridge] for the children, when am away, and when I cook nsima he assists with relish preparation and cooking though many laugh at him. My husband can do anything I can do for the child, [like] feeding, washing clothes. People feel I have given him ‘love' medicine. We also make decisions together. (Evaluation interview 5, with similar comments made by 7, 8 and 34, October 2012)

Men also talked about the transformations wrought in them since joining the project, at times waxing poetic about these changes during the interview in front of male neighbours and kin. As one older man insisted:

Nowadays I can help my wife, although at first most of the work was done by her. I can prepare food when my wife is busy with other household work, I even prepare the bed when my wife is cooking. (Evaluation interview 13, October 2012)

To paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir, one isn't born part of a household, one becomes one. At Recipe Days, women and men are offered the opportunity to perform gender relations differently. Women teach men to cook for the household (as opposed to simply for themselves, which they may already know to do if involved in labour away from their homes), exchanging nutritious recipes with other households. Recipe Days provide a space where men can feel safe and encouraged in new performances of ‘counter-hegemonic masculinity’ (Connell Citation1995), and where women can subvert gender roles and ‘undo gender’ with a freedom hard to find in other spaces (Butler Citation2004). The creation of these spaces makes it easier for gender transformation to occur. These transformations in turn lead to improvements in food security within the household. Recipe Days aren't magic, of course. They require extensive follow-up by community organizers in order for the lessons to be incorporated into everyday practice. The lessons don't always stick. The responses from the small-scale survey show a failure rate of around 25 percent, and the efficacy of the programme is currently the subject of ongoing statistically robust work.

We are also critical of those who are included and left out of these interventions. The landholding arrangements where SFHC takes place fall under traditional law. They happen with the permission of the village headman. His patriarchal authority is not the subject of debate or discussion. In addition, there are examples where families – usually migrants from southern Malawi looking for land – have joined the SFHC programme, improved the soil using agroecological methods and then have that land reclaimed by the village headman. In other cases, widows who have improved the land have it seized by their husband's family. We recognize the many layered inequalities, built on histories of dispossession and patriarchy, that mean only some peasant farmers benefit from this intervention.

We have tried in this discussion to emphasize the experience of the participants themselves in the Recipe Days, because it is their participation – and the subsequent follow-up by community organizers in maintaining the transformation of relations– that has mattered to them. Such an emphasis should not preclude, however, the importance of the intervention as a policy decision. This is a site of struggle that takes nutrition seriously, without devolving into nutritionism. Research carried out over a 7-year period demonstrated that the intervention made a significant difference in child stunting in the area. Over 3500 children had their height and weight measured before and after their household joined the project. Children in families that were participating actively in the project had improved child growth compared to families that were not in the project (Bezner Kerr, Berti, and Shumba Citation2010; ). Malnutrition rates have declined substantially in the region, to the extent that the Nutrition Rehabilitation Centre at Ekwendeni Hospital has closed, due to a lack of acute cases. While the Hospital's active Primary Health Care programme (including anti-malaria, maternal and child health and AIDS programmes) is likely responsible for a fair share of this decline, the SFHC project has also contributed to this dramatic shift in a little more than a decade (Bezner Kerr, Berti, and Shumba Citation2010).

Figure 4. Change in Ekwendeni children's weight (under the age of 3 years) between 2004 and 2007 by village involvement in the intervention (t = 0 at month in which village joined intervention). Villages are grouped according to the year in which they became control and intervention villages. The survey group effect was significant (P = 0.04). Significant differences were observed within groups (P < 0.05): (i) control year x – intervention year 2001, 1st survey < 3rd, 4th and 8th, 2nd survey < 3rd, 4th and 7th, 3rd survey < 5th, 6th and 7th, 4th survey < 7th, 5th survey < 7th, 7th survey < 8th; (ii) control year 2001 – intervention year 2002, 1st survey > 3rd, 4th and 5th, 2nd survey > 3rd, 3rd survey < 4th and 5th; (iii) control year 2001–intervention year 2003, 1st survey < 4th, 2nd survey < 7th, 3rd survey < 8th, 4th survey < 7th, 5th and 6th surveys < 7th. Source: Bezner Kerr, Berti, and Shumba (Citation2010).

IV. Dividends from comparing the New Alliance with Recipe Days

The innovations produced through processes that spawned Recipe Days show that insofar as they found the autonomy to research, farm, invest and distribute as they'd like, the participants in the SFHC project were able to be far more successful than the New Alliance might be (Van der Ploeg Citation2008). A number of differences suggest themselves from the comparison of the New Alliance and the SFHC project.

Perhaps most important is the issue of who gets to think (Pithouse Citation2006; Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2011; Neocosmos Citationforthcoming). That Recipe Days emerged from a process of farmer research, with no specific individual credited with the idea, is in marked contrast to the disempowering tropes of the New Alliance, which constructs the hungry as recipients – and buyers – of better food, but never as agents empowered to think through the problems and constraints around malnutrition.

Herein lies another difference between the New Alliance and the SFHC project – a taste for democratic politics. Under the New Alliance, the proper job of politics is to create and police a business-friendly climate, after which the efficiencies of the private sector, and the laser-like focus of science, will prioritise and address malnutrition, deficiency by deficiency. This biopolitical management of hunger seems to overwhelm the notion of using ‘nutrition’ in ways other than those conforming to the New Alliance's mode of governance. It is in this sense that the New Alliance's concern with nutrition places it in a trajectory of a Long Green Revolution (Patel Citation2013).

Yet in the SFHC project, an understanding of nutrition that heeds concerns of power and labour – particularly reproductive labour – guides a politics that pays little heed to the liberal distinctions of public and private sectors, or public and domestic space. Questions of distribution and inequality are inherently political. In addressing malnutrition, they cannot be postponed. The farmers involved in the SFHC project understand the political nature of hunger, and have created spaces where political work, at least at the local and household level, happens. Recipe Days are just one dimension of this work. The use of agroecological methods to improve soil fertility and food security is another (Msachi et al. Citation2009).

By contrasting the New Alliance to Recipe Days, we argue that the same problem – of households not having enough food, and children's bodies being deprived of the things they need to survive – is being addressed very differently and, in the case of Recipe Days, with success. The reconfiguration of the household, in counter-hegemonic ways, is an important pointer to ways in which prevailing hegemony can be countered. Of course, without further struggle against other forces within the historic bloc – international, domestic and traditional – little may change. The women and men who make Recipe Days happen do not do so in explicit opposition to the New Alliance. Yet in their addressing of gender, in their reconfiguration of productive and reproductive labour responsibilities and in the organizing that precedes and follows these events, Recipe Days reveal an understanding about the causes and responses to infant malnutrition that the New Alliance cannot – by its own constraints – address. This approach helps us explain why the New Alliance is actually about food security and nutrition. But it also points to the possibilities of different kinds of subjectivity than those on which the New Alliance depends. In Ekwendeni, people aren't consumers or passive recipients. They are architects, constrained but inventive, of new ways of being in the world – and agents, above all, of their own freedom. The New Alliance offers many things, but it can never offer that.

The authors would like to thank Steve James for suggesting the title, and the participants of seminars at the University of California, Berkeley, Center for African Studies and the Rhodes University's UHURU Humanities Lecture series for incisive comments on early presentations of this work. We also thank the SFHC community promoters for further insights into gender relations in their communities. The authors are also grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

Additional information

Raj Patel is a research professor at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, and a Senior Research Associate at the Unit for the Humanities at Rhodes University (UHURU), Grahamstown, South Africa. He is a fellow at The Institute for Food and Development Policy, also known as Food First. In addition to his scholarly work he has written for The Guardian, the Financial Times and the Los Angeles Times, among others. His first book was Stuffed and starved: the hidden battle for the world food system and his latest is The value of nothing: how to reshape market society and redefine democracy. He is currently working on a documentary project about the global food system, with director Steve James. Corresponding author.

Rachel Bezner Kerr is an associate professor in the Department of Development Sociology at Cornell University. Her research interests converge on the broad themes of sustainable agriculture, food security, health, nutrition and social inequalities, with a primary focus in southern Africa, and foci on (1) historical, political and social roots of the food system in northern Malawi, (2) sustainable agriculture, food security and social processes in rural Africa, (3) social relations linked to health and nutritional outcomes and (4) local knowledge and climate change adaptation.

Lizzie Shumba is the project coordinator of the Soils, Food and Healthy Communities Project, which she joined in 2003. Lizzie holds a diploma in nutrition from the Natural Resources College in Lilongwe, and she is completing her BSc in rural extension and nutrition at the Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources. She looks forward to sharing what she learns with her colleagues when she returns to Ekwendeni.

Laifolo Dakishoni, or ‘Dak' as he is commonly called, is an accountant and acting project coordinator at the Soils, Food and Healthy Communities Project (SFHC), and is currently the principal investigator and enterprise coordinator of the Malawi Farmer to Farmer Agroecology Project. He began with SFHC in November 2001, after study at the Malawi College of Accounting, where he earned a diploma in accounting, and where he continues his studies in chartered accountancy. Since 2001, he has enjoyed being part of the project's evolution, and has been greatly motivated by the farmers' eagerness to learn and try new things.

Notes

1This figure was subsequently revised downward by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in a statistical recalculation that has attracted controversy. As Lappé et al. note, the FAO revised the figure down from a peak of 1 billion in 2009 to a history in which hunger peaked in 1990 at 1 billion and has been falling, more or less, ever since (Lappé et al. Citation2013).

2The Group of Eight countries are Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the UK and the USA, with additional representation by the EU.

3It is a document in which the words ‘gender’ and ‘women' appear once each.

4The CAADP was an initiative of the African Union and the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), formalized in 2003 to address agricultural issues on the continent. Its goals include agriculture-led growth, a 6-percent average annual agricultural growth rate at the national level, and ‘Implementation principles, including program implementation by countries, coordination by regional economic bodies, and facilitation by the NEPAD Secretariat' (NEPAD Citation2005). See also Loxley (Citation2003).

5Tanzania's experience with the New Alliance has revealed a suite of problems with implementation, transparency and the promotion of large-scale agriculturalists over the concerns of poorer small-scale farmers (Sulle and Hall Citation2013).

6Strictly, this should be ‘the potential for agricultural policy’. While there are nearly three dozen different agricultural initiatives of various stripes, the country currently lacks a coherent and comprehensive agricultural policy.

7We cannot address Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) in the depth it deserves in this paper, and is the subject of future research. We note, however, that SUN is part of the Alliance both bureaucratically and ideologically. SUN featured in the Lancet special issue and Save the Children report that accompanied the G8 New Alliance event in London in 2013, at which President Banda committed Malawi to the New Alliance. It is worth observing that this event, billed as a ‘hunger summit’ by the British government, went by a slightly different name in its official literature. It was entitled ‘Nutrition for growth: beating hunger through business and science’ (Gillespie et al. Citation2013; Nabarro Citation2013; Ruel and Alderman Citation2013; Save the Children Citation2013).

8While pigeon pea and groundnut have both been grown in Malawi for many hundreds of years, the ‘doubled-up’ legume system involves intercropping two or more legumes together and then incorporating the legume residue to improve soil fertility for the next growing season. This system is a significant change from the normal practices of burning crop residue or intercropping legume plants within a maize field (Bezner Kerr et al. Citation2007).

References

- Allcott, H., D. Lederman, and R. López. 2006. Political institutions, inequality, and agricultural growth: the public expenditure connection World Bank. Washington, DC: World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3902, April 2006.

- Anderson, P. 1977. The antinomies of antonio gramsci. New Left Review 100.

- Atinmo, T., P. Mirmiran, O.E. Oyewole, R. Belahsen, and L. Serra-Majem. 2009. Breaking the poverty/malnutrition cycle in Africa and the Middle East. Nutrition Reviews 67, no. Suppl 1: S40–6. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00158.x

- Attwell, W. 2013. ‘When we have nothing we all eat grass’: debt, donor dependence and the food crisis in Malawi, 2001 to 2003. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 31, no. 4: 564–82. doi:10.1080/02589001.2013.839225

- BAFF, Business Alliance for Food Fortification. 2014. Public-private partnership launched to improve nutrition in developing countries. Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition. http://www.gainhealth.org/sites/www.gainhealth.org/files/baff_report_pdf_46271.pdf (accessed April 1).

- Banda, J. 2013. New food security alliance is timely for Malawi's path out of poverty. In The Guardian Poverty Matters Blog. London. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2013/jun/18/new-alliance-food-security-malawi (accessed June 19, 2013).

- Beck, U., R. Mussa, and K. Pauw. 2013. Did rapid smallholder-led agricultural growth fail to reduce rural poverty? Making sense of Malawi's poverty puzzle. UNU-WIDER Conference Paper 20–21 September 2013 Helsinki, Finland. http://www1.wider.unu.edu/inclusivegrowth/sites/default/files/IGA/Pauw.pdf

- Bellwood-Howard, I.R.V. 2014. Smallholder perspectives on soil fertility management and markets in the African green revolution. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 38, no. 6: 660–85. doi:10.1080/21683565.2014.896303

- Bezner Kerr, R. 2005. Informal labor and social relations in Northern Malawi: the theoretical challenges and implications of Ganyu labor for food security. Rural Sociology 70, no. 2: 167–87. doi:10.1526/0036011054776370

- Bezner Kerr, R. 2013. Seed struggles and food sovereignty in northern Malawi. Journal of Peasant Studies 1–31. doi:10.1080/03066150.2013.848428

- Bezner Kerr, R., P.R. Berti, and L. Shumba. 2010. Effects of a participatory agriculture and nutrition education project on child growth in northern Malawi. Public Health Nutrition 14, no. 08: 1466–72. doi:10.1017/S1368980010002545

- Bezner Kerr, R., and M. Chirwa. 2004. Soils, food and healthy communities: participatory research approaches in Northern Malawi. Ecohealth 1, no. Supplement 2: 109–19.

- Bezner Kerr, R., and P. Mkandawire. 2012. Imaginative geographies of gender and HIV/AIDS: moving beyond neoliberalism. GeoJournal 77, no. 4: 459–73. doi:10.1007/s10708-010-9353-y

- Bezner Kerr, R., R. Msachi, L. Dakishoni, L. Shumba, Z. Nkhonya, P. Berti, C. Bonatsos, et al. 2012. Growing healthy communities: farmer participatory research to improve child nutrition, food security, and soils in Ekwendeni, Malawi. In Ecohealth research in practice: innovative applications of an ecosystem approach to health, ed. D.F. Charron, 37–46. Ottawa: Springer/IDRC.

- Bezner Kerr, R., S. Snapp, M. Chirwa, L. Shumba, and R. Msachi. 2007. Participatory research on legume diversification with Malawian smallholder farmers for improved human nutrition and soil fertility. Experimental Agriculture 43, no. 4: 437–53. doi:10.1017/S0014479707005339

- Blanco Armas, E., C. Gomez Osorio, and B. Moreno-Dodson. 2010. Agriculture public spending and growth: the example of Indonesia. Washington, DC: World Bank: April 2010.

- Butler, J. 2004. Undoing gender. London: Routledge.

- Cafiero, C. 2012. What do we really know about food security? Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome: September 10, 2012. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/ess_test_folder/Food_security/What_do_we_really_know_about_FS_Sept9.pdf (accessed June 26, 2013).

- Carr, S. 2004. A brief review of the history of Malawian smallholder agriculture over the past fifty years. The Society of Malawi Journal 57, no. 2: 12–20.

- Chinele, J. 2014. Malawi: new land law stirs controversy among chiefs. 21 March 2014 AllAfrica. http://allafrica.com/stories/201403240109.html

- Chinsinga, B., and M. Chasukwa. 2012. Youth, agriculture and land grabs in Malawi. IDS Bulletin 43, no. 6: 67–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00380.x

- Chinsinga, B., M. Chasukwa, and Sane Pashane Zuka. 2013. The political economy of land grabs in Malawi: investigating the contribution of limphasa sugar corporation to rural development. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 26, no. 6: 1065–84. doi:10.1007/s10806-013-9445-z

- Chirwa, E., and A. Dorward. 2013. Agricultural input subsidies: the recent Malawi experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Comaroff, J., and J.L. Comaroff. 2011. Theory from the south, or, How Euro-America is evolving toward Africa. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Connell, R.W. 1995. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cullather, N. 2010. The hungry world: America's Cold War battle against poverty in Asia. Cambridge, Mass: London: Harvard University Press.

- Curtis, M., and J. Hilary. 2012. The hunger games: how DFID support for agribusiness is fuelling poverty in Africa. London: War on Want.

- Devereux, S. 2002. The Malawi famine of 2002. IDS Bulletin 33, no. 4: 70–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2002.tb00046.x

- Devereux, S., B. Baulch, A. Phiri, and R. Sabates-Wheeler. 2006. Vulnerability to chronic poverty and malnutrition in Malawi: A report for DFID Malawi. Institute of Development Studies. Sussex. https://www.ids.ac.uk/files/MalawiVulnerabilityReport_Final.pdf

- Dimova, R., S. Gangopadhyay, K. Michaelowa, and A. Weber. forthcoming. Ganyu Labor in Malawi. Understanding rural household labor supply strategies.

- The Economist. 2014. The $32 m heist. In The Economist. London: The Economist. http://www.economist.com/blogs/baobab/2014/02/malawi-scashgate-scandal (accessed April 11, 2014).

- Gibson-Graham, J.K. 1996. The end of capitalism (as we knew it): a feminist critique of political economy. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

- Gill, S., and D. Law. 1993. Global hegemony and the structural power of capital. In Gramsci, historical materialism, and international relations, ed. Stephen Gill, 93–124. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gillespie, S., L. Haddad, V. Mannar, P. Menon, and N. Nisbett. 2013. The politics of reducing malnutrition: building commitment and accelerating progress. The Lancet 382, no. 9891: 552–69. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60842-9

- Government of Malawi. 2009. National nutrition policy and strategic plan. Lilongwe: Department of Nutrition, HIV and AIDS. http://www.moafsmw.org/Key%20Documents/National%20Nutrition%20Policy%20&%20Strategic%20Plan%20%20Final%2009.pdf

- Gramsci, A., and J.A. Buttigieg. 1992. Prison notebooks, European perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Guthman, J. 2011. Weighing in: obesity, food justice, and the limits of capitalism. Berkeley, Calif., London: University of California Press.

- Henriques, G. 2013. Whose Alliance? The G8 and the Emergence of a Global Corporate Regime for Agriculture. CIDSE. Brussels, http://www.cidse.org/content/publications/just-food/food-governance/whose-alliance-_the_g8_new_alliance_for_food_security_and_nutrition_in_africa.html (accessed April 11, 2014).

- Higdon, J. 2014. Iodine. Linus Pauling Institute. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/minerals/iodine/ (accessed March 29, 2014).

- Holt-Giménez, E. 2008. Out of AGRA: The green revolution returns to Africa. Development 51, no. 4: 464–71. doi: 10.1057/dev.2008.49

- Holt-Gimenez, E. 2013. The new alliance for food security and nutrition: nothing new about ignoring Africa's farmers. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-holt-gimenez/africa-food-security_b_1537279.html (accessed June 2, 2013).

- Holt-Gimenez, E., M. Altieri, and P. Rosset. 2008. Ten reasons why the Rockefeller and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundations’ alliance for another green revolution will not solve the problems of poverty and hunger in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Hong, D., and ONE. 2014. New alliance for food security and nutrition: part 1. ONE. http://www.one.org/us/policy/policy-brief-on-the-new-alliance/ (accessed April 11).

- ILO, International Labour Organization. 2011. Malawi decent work country programme M-DWCP 2011–2016. http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/program/dwcp/download/malawi.pdf

- International Food Security Network, IFSN. 2011. Success in reducing hunger: lessons from India, Malawi and Brazil. Rio De Janeiro: International Food Security Network, February 2011.

- Kabeer, N. 1994. Reversed realities: gender hierarchies in development thought. London: Verso.

- Kanyongolo, F.E. 2005. Land occupations in Malawi: challenging the neoliberal legal order. In Reclaiming the land: the resurgence of rural movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. Sam Moyo and Paris Yeros, 118–41. London: Zed Books.

- Kimura, A.H. 2013. Hidden hunger: gender and the politics of smarter foods (Kindle edition). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Kinsley, M.E., C. Clarke, and A.V. Banerjee. 2008. Creative capitalism: a conversation with Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, and other economic leaders. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Koopman, J. 2012. Will Africa's green revolution squeeze African family farmers to death? Lessons from small-scale high-cost rice production in the Senegal River Valley. Review of African Political Economy 39, no. 133: 500–11. doi:10.1080/03056244.2012.711076

- LaGrone, L.N., I. Trehan, G.J. Meuli, R.J. Wang, C. Thakwalakwa, K. Maleta, and M.J. Manary. 2012. A novel fortified blended flour, corn-soy blend “plus-plus,” is not inferior to lipid-based ready-to-use supplementary foods for the treatment of moderate acute malnutrition in Malawian children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 95, no. 1: 212–9. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.022525

- Lappé, F.M., J. Clapp, M. Anderson, R. Broad, E. Messer, T. Pogge, and T. Wise. 2013. How We Count Hunger Matters. Ethics & International Affairs 27, no. 3: 251–9. doi:10.1017/S0892679413000191

- Lemke, S., H.H. Vorster, N.S. Jansen van Rensburg, and J. Ziche. 2003. Empowered women, social networks and the contribution of qualitative research: broadening our understanding of underlying causes for food and nutrition insecurity. Public Health Nutrition 6, no. 8: 759–64. doi:10.1079/PHN2003491

- Locher, M., and E. Sulle. 2013. Foreign land deals in Tanzania :An update and a critical view on the challenges of data (re)production. PLAAS. Cape Town, South Africa: May 2013. http://www.plaas.org.za/sites/default/files/publications-pdf/LDPI31Locher%26Sulle.pdf

- Loxley, J. 2003. Imperialism & economic reform in Africa: what's new about the new partnership for Africa's development (NEPAD)?. Review of African Political Economy 30, no. 95: 119–28. doi:10.1080/03056240308373

- McMichael, P. 2013. Value-chain agriculture and debt relations: contradictory outcomes. Third World Quarterly 34, no. 4: 671–90. doi:10.1080/01436597.2013.786290

- Msachi, R., D. Laifolo, R.B. Kerr, and R. Patel. 2009. Soils, food and healthy communities: working towards food sovereignty in Malawi. Journal of Peasant Studies 36, no. 3: 700–6.

- Murphy, S. 2014. G8 punts on food security … to private sector. TripleCrisis.org, Accessed 29 March. http://triplecrisis.com/g-8-punts-on-food-security-to-the-private-sector/

- Nabarro, D. 2013. Global child and maternal nutrition—the SUN rises. The Lancet 382, no. 9893: 666–7. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61086-7

- Neocosmos, M. forthcoming. Thinking freedom in Africa: subjective excess, historical sequences and emancipatory politics.

- NEPAD, New Partnership for Africa's Development. 2005. CAADP country level implementation process: Concept note based on the outcome of the NEPAD implementation retreat organized on October 24 and 25, 2005 in Pretoria, South Africa. NEPAD. Midrand, South Africa.

- New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition. 2013. Country cooperation framework to support the new alliance for food security & nutrition in Malawi. UK Department for International Development . http://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/208059/new-alliance-progress-report-coop-framework-malawi.pdf (accessed November 3, 2013).

- NSO, National Statistical Office. 2012. Integrated household survey 2010–2011 household socio-economic characteristics report. Zomba, Malawi: National Statistical Office. http://www.nsomalawi.mw/images/stories/data_on_line/economics/ihs/IHS3/IHS3_Report.pdf (accessed March 21, 2013).

- Pandolfelli, L.E., J. Shandra, and J. Tyagi. 2014. The international monetary fund, structural adjustment, and women's health: a cross-national analysis of maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Sociological Quarterly 55, no. 1: 119–42. doi:10.1111/tsq.12046

- Patel, R. 2007. Stuffed and starved: markets, power and the hidden battle for the world food system. London: Portobello Books.

- Patel, R. 2012. Food sovereignty: power, gender, and the right to food. PLoS Medicine 9, no. 6: e1001223. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001223

- Patel, R. 2013. The long green revolution. Journal of Peasant Studies 40, no. 1: 1–63. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.719224

- Patel, R., E. Holt Giménez, and A. Shattuck. 2009. Ending Africa's hunger. In The Nation, 2 September 2009. http://www.thenation.com/article/ending-africas-hunger

- Perkins, J.H. 1997. Geopolitics and the green revolution: wheat, genes and the cold war. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peters, P.E., and D. Kambewa. 2007. Whose security? Deepening social conflict over ‘customary’ land in the shadow of land tenure reform in Malawi. The Journal of Modern African Studies 45, no. 03: 447–72. doi:10.1017/S0022278X07002704

- Pithouse, R. 2006. Our struggle is thought, on the ground, running: the university of abahlali basemjondolo. Center for Civil Society Research Reports 40.