Abstract

As a concept and phenomenon, ‘flex crops and commodities’ feature ‘multiple-ness’ and ‘flexible-ness’ as two distinct but intertwined dimensions. These key crops and commodities are shaped by the changing global context that is itself remoulded by the convergence of multiple crises and various responses. The greater multiple-ness of crops and commodity uses has altered the patterns of their production, circulation and consumption, as novel dimensions of their political economy. These new patterns change the power relations between landholders, agricultural labourers, crop exporters, processors and traders; in particular, they intensify market competition among producers and incentivize changes in land-tenure arrangements. Crop and commodity flexing have three main types – namely, real flexing, anticipated/speculative flexing and imagined flexing; these have many intersections and interactions. Their political-economic dynamics involve numerous factors that variously incentivize, facilitate or hinder the ‘multiple-ness' and/or ‘flexible-ness' of particular crops and commodities. These dynamics include ‘flex narratives' by corporate and state institutions to justify promotion of a flex agenda through support policies. In particular, a bioeconomy narrative envisages a future ‘value web’ developing more flexible value chains through more interdependent, interchangeable products and uses. A future research agenda should investigate questions about material bases, real-life changes, flex narratives and political mobilization.

The rise of flex crops and commodities

Contemporary agrarian transformations are shaped by – and are shaping – a complex and dynamic mix of interests and concerns around food security, energy/fuel security, climate change mitigation, the recent global financial crisis and rising demand for natural resources and commodities from traditional hubs of capital (primarily North Atlantic), but also increasingly from the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries and some middle-income countries (MICs), which represent emerging centres of international capital.

One notable, yet still underexplored, dimension of the current era is the rise of ‘flex’ crops and ‘flex’ commodities. As our working definition here, ‘flex crops and commodities’ have multiple uses (food, feed, fuel, fibre, industrial material, etc.) that can be flexibly interchanged while some consequent supply gaps can be filled by other flex crops. Flexibility arises from multiple relationships among various crops, components and uses. Specific forms of flexible-ness and multiple-ness can become more profitable through several means – e.g. changes in market prices (of crop materials, substitutes or their ultimate products), policy frameworks (e.g. direct or indirect subsidy favouring specific uses or state procurement of commodities produced from specified components) and technoscientific advance facilitating conversion of non-edible feedstock (e.g. via microbial enzymes, biorefineries). The latter's economic viability depends on low-cost feedstock, which can be cheapened by several means, e.g. mining nature, super-exploitative labour, more intense market competition and land grabs. Current examples include soya (feed, food, biodiesel), sugarcane (food, ethanol), oil palm (food, biodiesel, commercial/industrial uses) and corn (food, feed, ethanol). These may be considered the most prominent, established ‘flex crops’; others are emerging on the horizon, including cassava, coconut, sugar beets, rapeseed and sunflower. Other commodities are starting to follow such a path too – for example, trees for timber, pulp, biomass, ethanol (from woodchips) and carbon sequestration purposes.

Although still initial and fluid, the emergence of flex crops and commodities partly addresses global-market price volatility, which can be a costly difficulty and/or an opportunity, depending on an actor's role in a wider value chain/web. Flex crops play a dual role in reducing uncertainty and stabilizing (or even increasing) profitability, from the different standpoints of vendors and purchasers. In a specific crop sector, flex crops allow for a more diversified product portfolio, thereby enabling investors to better anticipate – and more nimbly react to – changing prices, e.g. to better exploit price spikes or withstand price shocks. For the producers of intermediate and final goods, flex crops facilitate multiple sourcing and greater competition among suppliers, and, consequently, a more stable (or even lower) price. Such change might emerge from the vertical integration of production chains/webs. These two strategic perspectives can be contradictory and/or complementary.

With the emergence of, or speculation about, relevant markets and, in some cases, the development and availability of technology (e.g. flexible mills) that enables, or will potentially enable, maximization of multiple and flexible uses of these crops, diversification can be achieved within a single crop sector. When sugarcane prices are high, sell sugarcane. When ethanol prices are high, sell ethanol. Or at least this is generally assumed to be an incentive driving flex crops. When the actual market for biodiesel is not there yet, sell palm oil for cooking oil, while waiting for, or speculating on, a more lucrative biodiesel market that has yet to emerge. Or at least sell palm oil while wishing for a more profitable scenario to happen. Meanwhile build a storyline about this projected scenario to jump-start business undertakings, e.g. to raise investments, lure investors, entice governments, persuade affected communities and orchestrate favourable media attention to achieve some of these requirements. Flexing means that product lines can be narrowed without undermining allocative efficiency.

Such flexibility has recent precedents in corporate strategies around crop biotechnology. One strategy was theorized as ‘substitutionism’, seeking to reduce agricultural products to industrial inputs for food manufacture and/or to replace farm-based products with industrially produced substitutes (Goodman, Sorj, and Wilkinson Citation1987). By comparison, flex crops and commodities have greater capacity as substitutes for both inputs and outputs, thus potentially stimulating greater changes in production systems and power relations.

Bioeconomy visions

This flexibility is taken further by reconceptualizing agriculture as a source of biomass for a future bioeconomy. The bioeconomy agenda seeks extra flexibilities from mainly non-food biomass in global value chains. Biomass denotes renewable raw materials which can be readily decomposed and recomposed in more profitable ways. Agriculture is envisaged as ‘oil wells of the 21st century’. Non-edible plant material will have more lucrative uses offering an El Dorado, according to proponents (quotations cited in Birch, Levidow, and Papaioannou Citation2010; Levidow, Birch, and Papaioannou Citation2013). According to European Union (EU) lobby groups, the bio-economy is the ‘sustainable production and conversion of biomass into various food, health, fibre and industrial products and energy’ (Becoteps Citation2010). This means horizontally integrating several industries.

The agenda promotes flexibility of biomass feedstocks – their sources, types, conversion processes and end products. A central means would be an ‘integrated, diversified biorefinery – an integrated cluster of industries, using a variety of different technologies to produce chemicals, materials, biofuels and power from biomass raw materials’ (Europabio Citation2007). Strategies seek a competitive advantage for companies becoming ‘backward-integrated’ into multiple feedstocks and flexibly converting them into multiple products. ‘The newly established value chain will have room for non-traditional partnerships: grain processors integrating forward, chemical companies integrating backwards and technology companies with access to key technologies, such as enzymes and microbial cell factories joining them’ (DG R&I Citation2014, 68). As envisaged in this agenda, future biorefineries would enable more flexible uses of current crops as well as future ones:

Biorefineries that are designed to be flexible and modular will be able to take a wider range of feedstock or adapt to changes in demand for specific chemicals without large capital costs. This flexibility will also mean that a biorefinery will be able to cope with a variety of feedstocks that mature at different times of the year. A modular installation will also be able to change its processing technologies as new feedstocks are developed. From a research perspective, the emphasis must be on the development of a set of capabilities that are independent of particular fuels, chemicals and materials. (World Economic Forum Citation2010, 20)

In these future scenarios, technoscientific innovation will expand the range, role and economic value of flex crops (see penultimate section for a typology). Some crops also are being redesigned for biorefineries, e.g. for easier breakdown of cell walls or higher-value chemicals, whereby plants become ‘green factories’ for producing new compounds (ETP ‘Plants for the Future’ Citation2007). Alongside the interests of commodity traders to achieve a competitive advantage, research and development (R&D) investors have strategic interests in intellectual property from genetically modified (GM) crops and GM microbes producing enzymes for biomass conversion processes.

For developing flex crops and commodities, a future bioeconomy has also become a major R&D agenda within the European Commission (EC). During the period 2007 to 2013, its Framework Programme 7 allocated more than €60 million to future biorefineries. In its current seven-year successor, Horizon 2020, the bio-economy agenda is extended, e.g. for ‘renewable oil crops as a source of bio-based products’, towards ‘broadening the range of suitable oil feedstock candidates with optimally-lowered resource inputs and developing economically viable and sustainable, eco-friendly and bio-based products’. Going beyond imagined flexing (defined below), future bio-economy visions mobilize investment and policy support to help realize such a future. This agenda serves as an economic imaginary, portraying corporate interests as a common societal interest (Levidow, Birch, and Papaioannou Citation2013).

Dual concepts of ‘multiple-ness’ and ‘flexible-ness’ within a ‘bioeconomy web’

There are two dimensions of these crops and commodities that are distinct yet similar and overlapping. The distinctness and mutual constitution of these two dimensions are crucial to our understanding of flex crops. These dimensions are the ‘multiple-ness' and ‘flexible-ness' of crop and commodity uses.

The ‘multiple-ness' of crop and commodity uses

Most of the crops and commodities identified above potentially have multiple uses. Many of these crops have actual multiple uses. Coconut, for example, has always been referred to in the Philippines as the ‘tree of life' because every part of the coconut tree and the coconut itself has an important use and commercial value. This is the same as the popular sentiment towards the (sugar) palm tree in Cambodia. Producing alcohol from most of the popular ethanol feedstocks today, such as sugarcane, cassava and corn, has always been part of a long tradition of villagers producing their own alcohol and fuel from these crops. Of the current popular feedstocks for biodiesel, perhaps only jatropha does not have the chemical potential for multiple uses because it is toxic to animals and humans. Arguably, one of the principal reasons for the rather quick boom-and-bust cycle of jatropha, despite massive hype, is that it is not materially conducive to multiple uses.

While there is nothing particularly novel about crops having multiple uses, the contemporary agricultural restructuring explained above has resulted in the emergence of new additional uses that previously were not thought to be possible – at least technologically and commercially. Dating back a couple of decades or so, soya is a relatively recent boom crop that is associated with the rise of the global meat complex (Weis Citation2013). The soya oil by-product may have seen increased market demand with the expansion of the vegetable oil market worldwide, including in China. The most recent commercially significant by-product for soya is perhaps biodiesel (Oliveira and Schneider Citation2014). Sugarcane has multiple food-oriented uses, and is also famous for jumpstarting modern day bioethanol in the 1970s (McKay et al. Citation2014). Corn is a classic crop with multiple uses: sweetener, livestock feed and ethanol (Gillon Citation2015). Palm oil has been a popular vegetable oil for cooking and other foodstuffs. But by-products from producing palm oil – palm kernel cake, palm oil sludge and palm pressed fibre – are increasingly important commercial animal feedstuffs, and so is biodiesel from palm oil (Alonso-Fradejas et al. Citationforthcoming). Coconut's latest important commercial product lines come from coco coir. In light of climate change mitigation strategies, coco coir has become a popular commodity for soil conditioning, soil erosion control and slope stabilization, in addition to cocowater (for health issues), and biodiesel (cocodiesel).

There are new aspects of the emerging contemporary uses of these crops and commodities. First is the orientation of emerging uses that are associated with the political economy of changing dietary preferences, especially the growing preference for animal protein and animal products, and public health concerns such as heart disease, as well as socio-ecological narratives around climate change, which spur a search for renewable resources and energy. Second, the sources of demands for these commodities are more diffuse and global, rather than just being concentrated in a particular hemispheric corner or particular consuming social class – although the recent and rising demands from the BRICS and MICs are remarkable. For example, the dramatic increases in the production of livestock products and sugarcane ethanol in Brazil were matched by dramatic increases of consumption of these products domestically (Wilkinson and Herrera Citation2010). Third, in absolute terms, demand for these commodities globally has increased dramatically during the past decade or so.

Quantitative indicators in terms of area harvested, production, trade and value are important measurements and play a central role in studies of agrarian political economy. They tell us about current conditions and trends in a particular crop sector and are important in understanding the rise of flex crops and commodities. However, they also have inherent limitations, as these measures are unable to capture the emerging, dynamic and fluid political economic conjunctures around these crop and commodity sectors. If we base our analysis solely on what percentage of palm oil production actually went to biodiesel production and consumption, we will be able to capture the actually existing quantity and value of traded biodiesel output, but not the indirect yet crucial link between biodiesel and the expansion of oil palm plantations worldwide.

It is quite probable that policy narratives and trade talks about biofuels were enough to convince national governments and corporate investors to push for massive expansion of the sector, even though there is not yet a fully developed biodiesel market (Borras, McMichael, and Scoones Citation2010; Franco et al. Citation2010). Their actions might have been principally inspired by the prospect of a lucrative biodiesel market worldwide; they can afford to wait for that market to grow in the near future because meanwhile they can sell their palm oil in various commodity forms: cooking oil, cosmetic material and other commercial–industrial commodities. Thus, if we quantify the percentage of palm oil that already went to the biodiesel market, it is most likely not as much as the projected biofuel market, particularly given the growing prevalence of blending mandates (Wise and Cole Citation2015). This is the case in Indonesia where most palm oil is still traded for other purposes besides biodiesel. However, all these conjectures are informed guesswork on our side. These issues require systematic empirical research.

Hence, the emergence of a new type of multiple-ness of crop and commodity uses also necessarily alters the way we research the political economy of these crops and commodities: how and to what extent capital accumulation, social relations, and power and power relations are contested and transformed. We cannot rely solely on quantitative measurements of these products to examine political economic trends and meanings. This forces us to look more deeply and carefully into the political economy of these crops.

All together, these patterns and questions show that the multiple-ness of crop and commodity uses is both old and new, and the significance of this recent development cannot be taken for granted. The character, extent and trajectory of, as well as the demand for, these new types of multiple uses, linked to the old uses of these crops and commodities, may have resulted, or may result, in important changes in the patterns of production, circulation and consumption of these products, and those of others – and in how we understand these transformations. For one, it has altered old and created new routes of commodity circulation and sites of consumption. It has also drawn a much wider array of gatekeepers into the process of commodity circulation, such as food, energy, fuel, biotechnology and car and livestock companies, among others (Franco et al. Citation2010), including finance capital such as investment banks, hedge funds and so on (Clapp Citation2014; Fairbairn Citation2014; Isakson Citation2014).

The newness of some additional uses of these crops and commodities is not the end of the story. In some instances, it might only be the beginning because it brings us to the related concept of ‘flexible-ness'. We now turn to this issue.

The ‘flexible-ness' of crop and commodity uses

A crop with multiple uses is quite valuable; a crop with multiple flexible uses is even more so. If a crop or commodity use can be switched from one specific purpose to another with technical ease and with attractive economic return, then a link between multiple-ness and flexible-ness may have far-reaching political economic implications.

Obviously, for a crop to become a flex crop it should have at least two main uses; the more uses it has, then the greater its potential for flexing. Crops with a single principal use are less attractive in the contemporary context, unless the agronomic, technical and economic conditions for producing such a crop outweigh the conventional risks associated with a single crop–single use/commodity. As we briefly mentioned above, in our view, this is one of the reasons for the hype and the quick boom–bust cycle of jatropha. There are no known major commodity products or uses for jatropha other than biodiesel. But crops with multiple uses do not automatically have sufficient basis for flexibility. In our initial estimate, there are at least three minimum conditions for crops and commodities with multiple uses to become flex crops – namely, material basis, technological possibilities and profit viability.

First is the material basis, or the extent to which the chemical and physical constitution of a crop or commodity enables switching among multiple uses. For instance, some next generation biofuel feedstocks like grass, algae, and jatropha are being developed for a single use and, consequently, lack the material basis for flexing. Similarly, soya meal, copra meal, and palm kernel cakes have few other uses except as animal feed principally and food consumption secondarily. But soya oil, corn oil, coconut oil and palm oil have multiple uses – and these semi-processed products can be flexibly used – at least in principle in terms of their chemical constitution. For example, coconut oil can either be used as cooking oil or cocodiesel. Indeed, there are many crops and commodities that have the material basis for multiple flexible uses: for example, sugarcane, palm oil, soya, corn, coconut, cassava, sugar beets, sunflower, rapeseed, castor and wood chips. Some have more uses than others, and thus have better prospects for multiple flexible uses. Compare palm oil with castor, for example.

Two related issues are of relevance. On the one hand, there are crops and commodities that have by-products that can easily be developed into important commodities in the current changed context. This is the case of soya where, due to the current global political economy of livestock, the main product is soya meal, while soya oil has become the by-product. But this oil can be directed towards food uses or it can also be transformed into biodiesel. It is the reverse for coconut: the oil is the main product (for food and biodiesel uses) and the copra meal is the by-product (for animal feed). There is a better potential for multiple flexible uses in crops with important by-products.

On the other hand, as agribusiness continues to develop technology towards more efficient crop and commodity production, it is likely to lead towards the emergence of crops and commodities with less – not more – multiple uses. At least, this is the case for GM corn that is meant not for human consumption but for animal feed, in addition to being a feedstock for ethanol. Whether this will happen in other crops is something to watch out for. In our calculation, when this happens, the possibility for multiple flexible uses is reduced, but not completely eliminated.

Second is the technological possibility. One of the reasons why jatropha was quite popular initially was the fact that the technological requirement to transform farm-gate produce into oil is inexpensive and easily installed even at the household level. The seeds can be pressed easily for immediate use. Thus, we see ordinary farmers pressing their jatropha seeds to produce fuel for cooking, or for motorbikes or tractors. Different crops and commodities have varying technological possibilities. Ethanol plants are generally more complex than biodiesel ones. Among ethanol feedstock, sugarcane and corn require quite complex processing plants (Wilkinson and Herrera Citation2010; Gillon Citation2010). Crops like coconut and palm oil, on the other hand, present relatively less of a challenge. Technological capacity allows for the possibility and/or ease of crop and commodity flexing. But variation between countries regarding the current conditions for key crops and commodities in terms of technological possibility is one of the key empirical questions that need to be researched.

Third is profit viability. Even when a crop has the material basis, and the technological capacity is possible and/or available, flexing may not happen if it makes no business sense or if the technology is simply unaffordable. This is a concern in some ethanol sectors where updated food–ethanol-flexible plants can have very prohibitive costs, such as those in the sugarcane and corn sectors. Meanwhile, where a cheap substitute commodity exists, it will also render flexing for a crop infeasible. For example, palm oil and coconut are comparable crops in terms of multiple uses and potential for flexing, but palm oil remains generally cheaper than coconut, partly explaining the popularity of palm oil and not of coconut.

Our hunch is that where all three key requirements – material basis, technological capacity and profit viability – are available in favourable ways, the chances for flexing are high. This has to be validated empirically. But in our initial analysis, these three minimum conditions do not operate in a political vacuum. They are shaped in the political economic context of contestations around property, development and control of technology, how a labour regime is shaped, and how political power is exercised in society. Class formation and dynamics in society will influence whether these minimum conditions occur, and, if they do, how. State policies also play a critical role in determining whether these three minimum conditions are met, including public investment in R&D, agricultural subsidies and trade policies.

However, there are cases where there is potential for crop-use switching, but for some socio-economic and political reasons, actual flexing may not occur or may become publicly unpopular, especially if it comes up against a polarized food-versus-fuel dilemma. This is the case of corn, at least at some point a few years ago. Alternatively, there might be cases where switching uses occurs despite non-viable economic terms, as partly demonstrated in the debates about the efficiency of US corn ethanol (Gillon Citation2010).

In short, multiple uses do not necessarily lead to flexible uses. The expanding uses of certain crops and commodities influence and transform their patterns of production, circulation and consumption. An industry lobby group has envisaged ‘flexible and adaptable production systems’ through multiple uses of crops and their by-products: ‘Individual sectors will be mutually dependent on each other for raw materials and energy, together forming the Bioeconomy web’ (Becoteps Citation2010, 4). With this future vision of ‘web’ interdependence, the group advocates a public-sector R&D agenda for novel crops and processes which would render biomass more functionally interchangeable as well as resource-efficient.

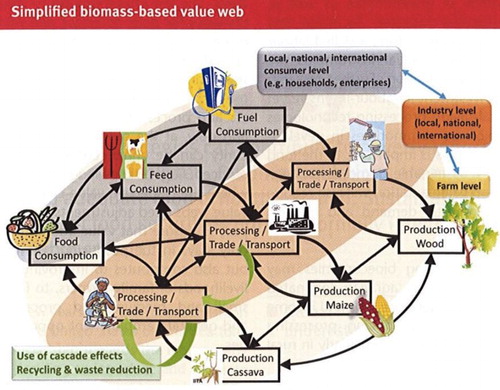

This web concept is further elaborated as the ‘biomass-based value web' concept by Virchow et al. (Citation2014, cited in Rural 21 Citation2014), explained at length in the extended quote below and by :

Undernourishment and micronutrient deficiency in Africa are still at high levels, while at the same time the international and domestic demand for non-food agricultural produce, like feed, energy and industrial raw materials, is continually increasing. The rising demand for more diverse biomass-based produce will transform traditional agriculture from a food-supplying to a biomass-supplying sector. Concepts are required which improve food security for the poor through increased food availability while supplying sufficient non-food, processed biomass to offer employment and income opportunities and hence improve the economic access to food. For these concepts analytic approaches are needed which are able to depict the increasingly complex ways of biomass from crop production to final consumption. Conventional value-chain approaches analysing single value chains are not sufficient anymore. We develop a biomass-based value web approach, in which the ‘web perspective’ is used as a multi-dimensional methodology to understand the interrelation between several value chains, to explore synergies and to identify inefficiencies in the entire biomass sector. This is instrumental to increase the sector's efficiency. The web perspective focuses on the numerous alternative uses of raw products, including recycling processes and the cascading effects during the processing phase of the biomass utilization. (Virchow et al. Citation2014, n.p.)

Figure 1. Virchow et al.’s biomass-based value web.

‘Value web’ emphasizes a continuous strategic flexibility in supply chains and ultimate products – by contrast to ‘value chain’, which implies rigid linear relationships. The idea of a broader biomass-based value web – as opposed to the narrow value chain – also provides landed, corporate and governmental interests the necessary ammunition and cover to engage in flex narratives to justify expansion of their drive for capital accumulation. They invoke a win–win–win scenario – where the dispossessed and exploited should be thankful for being entangled in the web rather than shackled in a chain.

Biofuel crops in the biomass-based value web

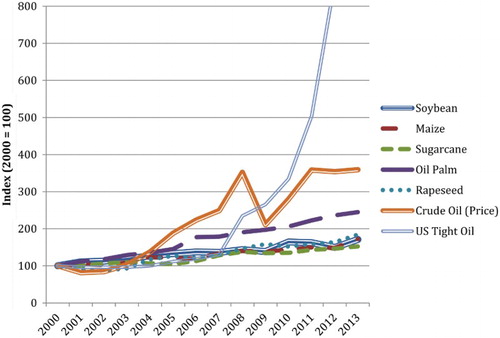

The formation of biomass-based ‘value webs’ means that no single end use will strongly influence the production of particular flex crops or flex commodities. When shifting economic and political conditions reduce the motivation for utilizing feedstocks for certain purposes, the logic of the web is that processors will simply redirect them to other uses. Thus, while concerns about ‘peak oil’ and climate change played a key role in the increased production of biofuels, the corresponding development of the broader bioeconomy should theoretically ensure resilient demand for flexible biofuel feedstocks, even in the face of recent developments in the global energy sector. A preliminary analysis of empirical data supports this hypothesis. relates changes in crude oil prices, tight oil (i.e. ‘shale oil’) production in the United States, and the global production of major flexible biofuel feedstocks. As the trends suggest, the cultivation of biofuels crops has steadily increased despite the explosion in shale oil production since 2007 and rising, yet fluctuating, crude oil prices. Moreover, as the ‘elasticity’ – or responsiveness – measures in suggest, the dramatic drop in oil prices between 2008 and 2009 and the subsequent spike between 2009 and 2011 had very little impact on the production of principal flexible biofuels crops. As a general rule, elasticity measures that are less than one are considered ‘inelastic’ and thus unresponsive to change in the relevant variable. The fact that all of the measures in are so close to zero suggests the production of all key biofuel feedstocks was unaffected by the significant, albeit short-term, changes in the price of crude oil in 2007–2011. While this is somewhat expected with perennial crops like oil palm and sugarcane, where changes in land use practices require significant work, the global production levels for annual crops (e.g. maize, soybeans, and rapeseed) that can be replaced with significantly more were also unresponsive to changes in the price of oil.

Figure 2. Changes in Crude Oil Prices, the Production of U.S. Shale Oil, and the Global Production of Major Flexible Biofuel Feedstocks (2000–2013).

Sources: FAOSTAT Citation2015; U.S. Energy Information Administration Citation2015a; and U.S. Energy Information Administration Citation2015b.

Table 1: Elasticity of Biofuel Feedstocks to Changing Crude Oil Prices

In part, the consistent increase in biofuel feedstocks is attributable to favorable political policies, most notably the growth of consumption mandates, which are now in place in some 64 countries and will require a significant increase in the production of first generation biofuels in coming decades (Wise and Cole Citation2015). This, however, raises the question of whether a significant and long-term drop in oil prices and/or the relaxation of consumption mandates in major biofuel consuming nations would spur an unravelling of the ‘value web’. Is the bioeconomy viable without political and economic conditions that are favorable to the production of biofuels? That is, does the potential to flex mean that demand for oil palm, sugarcane, and other major biofuel feedstocks will remain strong even when biofuel production is not viable? What about crops that are not widely used as biofuels? Given forecasts for significantly lower oil prices for throughout the remainder of the decade (IEA Citation2015), the answer to these questions may soon be evident.

Of course, the long-term viability of flex crops and commodities is not only contingent upon there being sufficient demand (for biofuels or otherwise). It is also highly dependent upon producers' access to sufficient capital. Whether this actually materializes is largely dependent upon financial actors' willingness to invest in said commodities. In the contemporary era of financialization, the unique qualities of flex crops may make them a particularly enticing target for investors who are awash with surplus funds. We now turn to this topic.

Financialization and the rise of flex crops

Interlinked with the contemporary food, fuel and economic crises, financialization is among the various processes that have likely contributed to the rise of flex crops and flex commodities. Financialization is most commonly understood as the growing importance of financial motives, actors and markets in the operations of economies and their governing institutions (Epstein Citation2005). While the process has manifested itself in a variety of forms, from the growing power of corporate shareholders to the mediation of social relations by financial logics, financialization is often understood as a recurring feature of capitalism, wherein profits increasingly derive from speculative activities rather than the trade and production of actual commodities (Krippner Citation2011; van der Zwan Citation2014).

The most recent phase of financialization emerged as a response to a crisis of overaccumulation in the 1970s. Faced with insufficient demand for their products and declining profits, US and European enterprises redirected their surplus capital from productive activities to financial markets (Arrighi Citation1994; Harvey Citation2010). Finance capital sought refuge in various activities in the subsequent decades – including technology stocks, foreign currency and housing – producing a series of speculative bubbles. Most recently, it has targeted the food and agricultural sector, speculating on activities all along the agro-food supply chain (Isakson Citation2014). A prerequisite to this, of course, is that the different aspects of agro-food provisioning – be it farmland, price risk or weather uncertainty – must be assembled into investible objects (Isakson Citation2015; Li Citation2014; Martin and Clapp Citation2015). That is, seemingly ethereal financial products are ultimately tethered to something tangible (Leyshon and Thrift Citation2007). Flex crops and commodities provide such a foundation.

This section considers how the financialization of food and agriculture has been codetermined by the emergence of flex crops. Our argument is that the multiple and flexible uses of some crops and commodities have the potential to mitigate risk on investments while maximizing returns, thereby rendering them a particularly attractive target for financial speculation.

Among the various financialization-induced changes to agro-food provisioning, the impacts upon commodity prices have received the most attention. Flex crops play an important role in this story. The prices for several emblematic flex crops – including oil palm, maize, soya, sugar, timber and coconut – have increased dramatically since the onset of the contemporary financial crisis in 2006. In real terms, prices for these crops remain at or near 30-year record highs (World Bank Citation2014). These increases are likely both the cause and the result of financialization. As several scholars have documented, the recent spikes in – and subsequent volatility of – agricultural commodity prices cannot be explained by underlying market fundamentals (Clapp Citation2009, Citation2014; Gilbert Citation2010; Ghosh, Heintz, and Pollin Citation2012; Spratt Citation2013).

Instead, they point to the dramatic increase in speculative activity in commodity futures markets over the past decade. Whereas orthodox economic theory and the so-called ‘efficient markets hypothesis' suggest that conditions in the spot markets where actual commodities are traded will guide prices in futures markets (i.e. futures markets are accurate predictors of real-world conditions), these scholars have documented a ‘contango' effect, wherein financial speculation in agricultural futures markets determines the prices of physical commodities in spot markets. The result is that speculative bubbles in futures markets have transmitted to actual spot market prices for a number of commodities, including prominent flex crops like maize and oil seeds (Palm Oil HQ Citation2009; Gilbert Citation2010; Pradhananga Citation2013). Of course, speculative exuberance has inflated the prices of a variety of commodities, not only flex crops. Nevertheless, as will be discussed below, the rising prices of flex crops have attracted financial interest in other arenas beyond futures markets. First, however, it is worth considering why financial capital might have a special interest in flex crops.

Financial capital may be particularly attracted to flex crops because their multi-functionality helps to mitigate the purported trade-off between risk and yield on investments. As noted earlier, investing in crops with diverse uses is akin to diversifying one's portfolio. A single crop is demanded by markedly different sectors, thereby ensuring a minimum number of buyers and mitigating market risk. In other words, the fact that flex crops can be sold in multiple markets ensures the liquidity of investments, or the ability to easily convert them to cash, making them particularly attractive to investors seeking a ‘flight to quality' during the economic downturn.

In the contemporary context, the multiple-ness of flex crops not only helps to ensure a minimum demand from a given sector, but often promises a growing overall market demand and, correspondingly, a rising price. More than having many uses, prominent flex crops like maize, oil palm, soybeans, trees and sugar are each posited as a solution to a number of crises – food, energy, climate – that afflict contemporary society. Whether real or imagined, the idea that a particular flex crop is a silver bullet that can solve such vexing problems feeds the notion of spectacular and sustained yields. Consider a recent article in Moneyweek entitled ‘Palm oil is set to boom: you should buy in now' (Stevenson Citation2012). Palm oil ‘has a wide – and growing – variety of uses, both food and industrial', the author observes. ‘And', he continues, ‘it could be about to surge in price'. He implies that strong demand from the food and industrial sectors renders oil palm a safe investment, while growing demand for alternative fuels promises spectacular returns in the short run and a ‘longer-term bull market' (Stevenson Citation2012).

As the author of the Moneyweek article observes, there are multiple ways that investors can speculate on flex crops. While they can ‘dabble in the futures market', he encourages buying shares in plantations where there is a possibility of capturing surplus from multiple stages of the value chain (Stevenson Citation2012). A cursory investigation suggests that there are plenty of opportunities for investors to buy into flex-crop enterprises. The funds raised through such initiatives seem primarily intended to acquire farmland and, importantly, to invest in the mills and refineries that could potentially enhance the enterprises’ ability to flex – or determine how a particular crop is utilized. Provisioning credit and insurance represents a third channel through which financiers can tap into the expanding flex-crop sector.

The rise of flex crops cannot be disassociated from the ‘financialization of daily life', or the growing role of credit and debt in the social reproduction of agrarian households (Martin Citation2002; Rankin Citation2013). With the neo-liberal dismantling of the Keynesian welfare state and the consequent emergence of the contemporary ‘debtfare' state, rural development has increasingly been construed as financial inclusion (Soederberg Citation2012, Citation2013). States no longer play a key role in the provisioning of agricultural inputs, rural infrastructure or risk management. Instead, farmers who are now dependent upon modern technologies are expected to acquire them on credit. The role of the debtfare state and other development actors is to facilitate poor peoples’ access to loans (Soederberg Citation2013). Of course, credit/debt is a double-edged sword that can both empower and constrain borrowers. The conditions attached to loans, and more generally financial inclusion, can be used to discipline farmers, typically limiting their production to approved crops.

Given the potential of flex crops to minimize risks while maximizing returns, lenders are likely to structure farmers’ land-use practices accordingly. In Guatemala, for instance, the state and other actors have identified oil palm production as a catalyst for pro-poor development in the country's impoverished northern lowlands. Small-scale farmers – at least those who have managed to retain their land (see Alonso-Fradejas Citation2012) – are encouraged through political, social and economic means to take loans and cash advances to acquire the inputs and technical knowledge for cultivating oil palm that they subsequently sell to specified palm oil enterprises on a contract basis. The initiative has contributed not only to the dramatic expansion of oil palm production in the region, but also to small-farmer debt (Guereña and Zepeda Citation2013).

The financialization of daily life has also permeated the management of agricultural risk. Whereas agriculture has always been risky, the dangers have been accentuated by the environmental uncertainty associated with climate change (Ribot Citation2014) and volatile commodity markets (Clapp Citation2009; Ghosh Citation2010). In the absence of moral economies and state support, farmers are left to independently manage risks. For financiers, the rising uncertainty that has accompanied the privatization of agricultural risk represents a new avenue for speculation. They have promoted a variety of financial instruments that purportedly help farmers mitigate risk, including the increasingly prevalent instrument of weather-based index insurance aimed at small-scale producers (Johnson Citation2013; Isakson Citation2015).Footnote1

Yet, like credit, oftentimes insurance is only offered for specified crops, namely those on which underwriters are willing to gamble (Isakson Citation2015). The ability to mitigate risk through flexing may mean that insurers are more partial to crops with multiple uses. In short, even as the financial sector profits from selling credit and insurance to farmers, it may also be implicitly pushing risk-averse farmers to cultivate flex crops. Its ability to do so is augmented by the fact that many lenders require borrowing farmers to acquire crop insurance. This practice is particularly prevalent among micro-lenders who often bundle insurance with loans. The result is that flex crops have become a means for both investors and processors to mitigate the risks associated with climate change and the increased volatility of commodity prices. This, however, is mostly conjecture. The extent to which different forms of agrarian finance shape land-use practices and whether there is a bias for flex crops warrants focused empirical research.

Real, anticipated or imagined: an initial typology of crop and commodity flexing

When the material basis, technological capacity and profitability are present, there are great possibilities for flexing. Even without either or both technological capacity or profitability, flexing is invoked for various purposes other than real crop and commodity flexing. Even where the three minimum conditions for flexing do not occur or are unobtainable, just conjuring the idea of flex crops and commodities is sufficient to trigger a real-world chain of events that can have far-reaching implications for agrarian transformation.

As we have mentioned above, we are interested in the politics of actualizing multiple commercial uses of crops and commodities as well as the possibility of flexing. For the purposes of this paper, by flexing we mean at least three broad types, which are best analyzed in their mutual intersections rather than separately.

Real flexing

The first type is real flexing. By real flexing we mean that there is a material and logical basis for flexing, so that it sometimes occurs. For example, with the mandatory blending of two percent for coco-diesel in the Philippines and a corresponding set of tax incentives for coco-diesel production and trade, a number of coconut oil millers and traders quickly fulfilled the blending requirement by shifting the final destination of their coconut oil from the traditional vegetable oil and other markets to the domestic coco-diesel market. The technological and investment requirements for flexing seem to be easily achieved (compared to the much larger requirement for building a sugarcane ethanol plant, for example). Within only three years, the millers and traders were lobbying to increase the mandatory blending quota to five percent to consume the over-supply of domestic coco-diesel. This case represents a situation where it is relatively easy to switch the ultimate use of coconut oil. If and when sugarcane millers are able to control whether to crush their sugarcane for sweetener products or ethanol, depending on price signals and/or subsidy/tax, real flexing can actually occur. This is the same with palm oil, canola, sunflower, sugar beets, corn or cassava.

Real flexing may be triggered by a series of related crop-use changes. For example, when canola oil that was predominantly used for food purposes was suddenly used to produce biodiesel, as in Germany – partly in order to produce biodiesel domestically – this shift left some market gaps where it was previously used in the food sector. This subsequent market gap could then be filled by imported palm oil. The two types of oil in this context then are tightly intertwined (Franco et al. Citation2010). In a way, these vegetables oils are ‘fungible', in the way described by McMichael (2010) – meaning you could have switched oils for both purposes, at least hypothetically speaking. The actual politics and economics of this are empirical matters that need to be investigated rather than assumed.

Based on initial, largely anecdotal, evidence, we know that various crops and commodities are really being flexed. To what extent this actually occurs, how this actually happens and what factors encourage/discourage, facilitate or block real flexing from happening in one sector versus another, or from one geographic setting to the next, are all empirical questions that ought to be investigated more carefully – and urgently.

Anticipated flexing

The second type is anticipated flexing. In this case, no flexing happens, but there is significant anticipation of or speculation about such activities based on a clear material and logical basis. As explained earlier, deals for major investments, including large-scale land acquisitions and investment pledges, are usually achieved on the basis of the dual ideas of multiple uses for crops and commodities and the possibility of flexing.

The Procana sugarcane ethanol company was able to secure 30,000 ha of land in southern Mozambique largely by projecting the rosy picture of multiple crop uses of sugarcane, including crop flexing for ethanol and other bioethanol-based commercial products such as ‘green plastics'. However, the first few years of operation of Procana saw only the production of conventional sweetener products, not ethanol. It had to close a few years after getting started, sometime in late 2011, having failed to mobilize sufficient investments in Europe. It was not able to build the much-vaunted Brazilian flexible sugarcane mills (Borras, Fig, and Monsalve Citation2011).

In this Mozambican example, there has been no real flexing. But flexing was, and is, an important aspect of the government and corporate narrative. It has material basis, and it sounds logical, legitimate and convincing. As this example shows, anticipated or speculative flexing – even before it is realized, if at all – can already have material, far-reaching impacts on the lives and livelihoods of real people. Ethanol was never produced in the Procana plantation, but the anticipation of or speculation about such production nevertheless transformed pre-existing social structures and institutions in this part of Mozambique, even after Procana pulled out in late 2011.

In short, flexing does not have to be real and happening for it to have important impacts – and for it to be taken seriously. Its significance is felt even when it is just anticipated or speculated.

Imagined flexing

The third type is imagined flexing. By imagined flexing we mean flexing that is not real, not actually happening and has no material or logical basis, yet it is invoked for some reason. While it has elements similar to anticipated or speculative flexing, the key difference is that the latter has material, logical and legitimate basis for anticipation; imagined flexing does not have these elements.

An example is the case of big landed elites in the sugarcane sector in the central Philippines. Land reform in the Philippines has been ongoing since 1988, with a chequered history, but has delivered some partial success (Borras Citation2007). One of the remaining bastions of resistant big landlords is the sugarcane sector where the hacienda system inherited from the colonial times has persisted into the twenty-first century. There are a number of legal loopholes in the land reform law that landlords persistently exploit to evade land redistribution (Franco Citation2011). One loophole protects ‘corporate farms' that are plantations run in a highly capitalized manner. Alternatively, other modalities of reform used to be allowed, such as a stock distribution option. When the National Biofuels Policy was enacted in 2006, it was widely seen as due to support from anti-land reform speculative interests (Padilla, Citationn.d.). In fact, some powerful and well-connected landlords invoked conversion to modern ethanol plants as a legal basis to evade land reform. This was the case in the land controlled by the brother-in-law of former President Macapagal Arroyo, the Hacienda Bacan in Negros Occidental, immediately after the passage of the biofuels act (Gomez Citation2007). A close examination of these landlords would likely show that they are incapable of such dramatic recapitalization, and that a modernizing and entrepreneurial character is not a feature of conventional comprador type sugarcane landlords in the central Philippines. Instead, landlords continue to avoid land reform, and invoking an imagined flexing has been added to their repertoire of narratives.

Stepping back and looking at the big picture, it is not difficult to speculate that these three types of flexing can and do co-exist in a given place and time – in parallel with, contradicting or complementing, facilitating or undermining one another. It is highly political. The points of intersection between these various types, and their implications, are crucial areas for empirical investigation. The factors that encourage, discourage, facilitate or hinder flexing are not just chemical–physical and technological; they are very much political. To what extent these three types manifest in different settings and in various crop and commodity sectors is one of the unknowns that need to be researched more empirically, extensively and carefully.

Moreover, and equally important, regardless of whether there exists real, anticipated or imagined flexing, the notion of crops with multiple and flexible uses provided the basis for corporate and government elites to engage in what we call ‘flex narratives’: when cornered about promoting biodiesel from palm oil, they can easily duck and claim to be interested only in food uses, and so on. As Franco et al. (Citation2010) showed, the European Union jumped from one justification to another to promote biofuels: from climate change mitigation strategy to energy security to livelihood development, and often combining these. It is along the same lines that landlords, companies and many other interest groups engage in flex narratives – as suggested many times earlier in the paper – to maximize the potential of flex crops in providing them enough justification, or cover, in their aggressive drive for capital accumulation.

In the World Economic Forum report cited above, for example, imagined flexing incentivizes change in land use which can become actual flexing. In the report, rising market demand appears as an objective force – an ‘exponentially increasing demand’ for raw materials – as if this were exogenous to blending mandates and the industrial sectors fulfilling the demand. It ‘may shift the relative economics of food/feed production vs other land uses, such as cellulosic energy crops’ (World Economic Forum Citation2010, 20). More flexible uses will give the global South greater business opportunities to supply raw materials:

a new international division of labour in agriculture is likely to emerge between countries with large tracts of arable land – and thus a likely exporter of biomass or densified derivatives – versus countries with smaller amounts of arable land. (World Economic Forum, 21)

In particular, Africa has a great economic opportunity but faces several challenges:

One is their low agricultural productivity caused by suboptimal agricultural practices, such as lack of fertilizers, deficient crop protection, shortcomings in the education and know-how of farm workers, insufficient irrigation and the dominance of smallholder subsistence farming. (World Economic Forum, 17).

Expressed less euphemistically, Africa must weaken peasants’ land-tenure to replace their agriculture systems with chemical-intensive agro-industrial plantations.

Recasting the political economy of flex crops and commodities

The political economy of flex crops and commodities is necessarily recast in several ways, eight of which are: (1) changed multiple sites and levels and increasingly long-distance interconnectedness; (2) new owners of capital and technology; (3) continuity and change in the organization of production and the emerging labour regime; (4) new commodity producers and traders; (5) a new range of consumers; (6) crop-use and land-use change; (7) the role of the state; and (8) the evolving role of international regulatory institutions (taking Bernstein's four fundamental questions in agrarian political economy as a reference point; Bernstein Citation2010). It is important to examine these interrelated categories to understand the character, pace, scope, trajectory and implications more broadly of the rise of flex crops and commodities – and what it implies for future research. In particular:

Changed multiple sites and levels and increasingly long-distance and complex interconnectedness

Although the specifics need empirical investigation, it is clear that the new aspects in the multiple-ness of crop and commodity uses have partly altered the sites and levels of production, circulation and consumption of these commodities and/or other key commodity routes. A good example is sugarcane ethanol, where Rotterdam and Singapore (their ports and financial districts, to be specific) have become important transit points for this traded fuel, although their ultimate origin may likely be Brazil. The outflow of Indonesian palm oil is going to places that include China, India and the EU, but with different product lines and consumption contexts. In the EU, palm oil partly filled the market gap for food use left by the conversion of rapeseed oil to biodiesel. There might also be an increasingly long-distance and complex interconnectedness between these sites of production, circulation and consumption. For example, Indonesian palm oil traded for food use in China is intertwined with the anticipated or imagined biodiesel market in the EU. These changed sites and the character of interconnectedness have become important dimensions of the political economy of these crops and commodities.

Owners of capital and technology

The production of flex crops and commodities is generally capital intensive, although there remain significant variations. As mentioned earlier, ethanol plants for sugarcane and corn are the most expensive to build and operate. Key to maximizing the multiple flexible uses of these crops and commodities is the ownership and control of processing technologies. This is where non-agrarian elites come in. Perhaps most especially the industrial bourgeoisie and international/finance capital may work in alliance or competition with agrarian elite classes (recall our discussion earlier, in the section on financialization). Depending on the history and pre-existing agrarian structures and institutions, this may erode – or reinforce – traditional landed classes in agrarian societies. In parallel, a bioeconomy narrative envisages a future ‘value web’ developing more flexible value chains through more interdependent, interchangeable products and uses; as this illustrates, flex narratives help to promote supportive policies.

Organization of production and emerging labour regimes

The organization of production of these crops and commodities is marked by continuity and change. Traditional organization of production that has generally been based on monocultures and/or large-scale plantations in combination with strategic processing plants has generally remained the same in most of these sectors. However, we are also witnessing important varied tendencies: the incorporation of small oil palm growers as suppliers of palm fruit through a variety of contracts; the shrinking share of commercial family farms in the land area in the US Midwest; the proliferation of land lease arrangements, particularly in the sugarcane sector in Brazil, and some variants of this in the soya sector of Argentina – namely, the ‘pools de siembra' (see Gillon Citation2010; McCarthy Citation2010; Murmis and Murmis Citation2012, respectively). While monocultures and the incorporation of processing technology and plants are quite common in contemporary organization of production, the rest can vary quite widely. Companies will explore various modalities as long as they gain control of resources and profit. Thus, there is a significant incorporation of family farms in the emerging value chains, whose farm sizes can vary widely: from a three-ha oil palm farm in Malaysia to a 3,000-ha corn farm in Iowa. While monocultures and industrial large-scale plantations are generally labour-saving enterprises, some arrangements are labour intensive – e.g sugarcane cutting work in Brazil, as well as oil palm plantations in Indonesia. This is not to say that the conditions and terms of incorporation are desirable, especially since the Brazilian sugarcane sector is infamous for the slave-like conditions faced by cane cutters. Observers argue that the optimistic estimates of the labour absorption capacity of the Indonesian oil palm sector are inflated (Li Citation2011). Nevertheless, relative to smallholder-based agriculture with little mechanization, industrial monocultures generally expel or save more labour than they absorb.

Commodity producers and traders

Commodity producers remain varied, ranging from large-scale industrial agribusiness companies to smallholder producers, and diverse other types in between. We see this in soya, sugarcane, oil palm, corn and even tree production. But most of the smallholder producers are subordinated to the larger agribusiness conglomerates that control the commodity chain. Traders are far more diverse, involving key players in sectors that were not previously engaged in agriculture, such as car and energy companies moving to food and biofuels, and, likewise, some food companies diversifying into trading of fuel commodities (Franco et al. Citation2010).

Range of consumers

The new character of several crops and commodities necessarily expands the spread of their consumption, implicating a much wider range of actors. Brazilian sugarcane used to be largely linked to consumers outside that country through its sweetener products, but its expansion into ethanol production has multiplied the number of consumers of this crop. Palm oil has consistently had a very widespread reach in terms of consumption because of its inclusion as a basic ingredient for a wide range of products, from chocolates to shampoo to cooking oil. But this reach widened even more when it became one of the most popular biofuel feedstocks. Thus, long distance, de-personalized connections between the production sites on the one hand and the consumption sites and the social groups therein on the other hand have become much more dense and far more complex – they connect far more people across societies.

Crop-use and land-use change

The rise of flex crops has complicated notions of land-use change. Early discussion among activists about biofuels tended to equate production of biofuels to land-use change. Indeed, there were, and are, farms that were dedicated to food that were converted to produce biofuel feedstock, triggering the earlier food-versus-fuel debate. But the current situation is more complicated than this. It seems that a significant part of what is happening is more of a ‘crop-use change' than the conventional ‘land-use change’ – but of course the former is intimately linked to the latter. Changing the use of a crop means changing the use of the land as well, since it changes the ultimate purpose of cultivating the land, even though the particular plants on the land may not change.

However, it is useful to analytically separate the two concepts. When much of the corn harvest from the US Midwest was converted from feed and food products to ethanol, farmers continued to cultivate the same high-yielding varieties. When Indonesian palm oil that was previously produced for cooking oil was instead used as biodiesel, it did not require any change in the plantation. There are similar stories for sugarcane, coconut, soya, sunflower, cassava and others. The notion of ‘crop-use change' can better capture this aspect of the rise of flex crops and commodities, rather than the conventional notion of land-use change. Still, this has resulted from the rise of flex crops being harvested on more land; thus, understanding land-use change is also still important.

As above, when US corn cultivation was increased and shifted to ethanol production, US soya cultivation fell and Brazilian soya cultivation rose to fill the gap. In this way, crop-use changes created a market gap and thus stimulated land-use change elsewhere. Often this means land clearing for crop monocultures, which causes more social and environmental harm than a change from one crop to another. This indirect land-use change (ILUC) has become the focus of advocacy campaigns against biofuel expansion. Similar harm may likewise result from other changes, like shifting crops or land to animal feed.

Role of the state

Institutional factors also facilitate, hinder, encourage or discourage key actors in exploiting the potential multiple-ness and flexible-ness of these crops and commodities. Some options are framed and pushed strategically by the state, e.g. by creating a favourable investment climate, land laws, trade policies and agreements, biofuels mandatory blending laws, climate change mitigation strategies, taxation, labour laws, foreign ownership laws or subsidies. These are among some of the main variables that facilitate or block the efforts of key actors to harness the potential multiple-ness and flexible-ness of crops and commodities. In addition, the global land rush that has accompanied the rise of flex crops and commodities could not have proceeded smoothly, effectively and widely without the central and critical role played by the state in terms of legal and political justification, definition, quantification, identification, appropriation and disposition of lands needed by investors, that are legally claimed by the state. This is especially so because investors mainly target public/state lands precisely because they can be acquired at low cost and deals can be facilitated relatively easily by the state as a willing partner. Hence, despite the neoliberal call for the retreat of the state, the latter seems to be called back to carry out institutional reforms to harness the potential of flex crops and commodities in capital accumulation.

International regulatory institutions

There are multiple regulatory institutions, instruments and principles that have evolved alongside the expansion of the production and consumption of some crops and commodities. These global governance instruments range from obligatory governmental instruments or principles such as human rights instruments and the free, prior, informed consent (FPIC) to voluntary codes of conduct under the umbrella of corporate social responsibility (see Franco Citation2014 on FPIC). In the latter, especially, we have witnessed the proliferation of sectoral voluntary standards, including the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the Roundtable for Sustainable Biofuels (RSB) and the Roundtable for Sustainable Soya (RSS), among others. In addition to FPIC, probably the most popular of governmental instruments is the Voluntary Guidelines for the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (TGs), popularly perceived by civil society organizations as an instrument that is closer to an obligatory type than a voluntary one, despite the label. The challenge for researchers, social movement activists and policy experts is to understand the ways in, and the extent to, which the rise of flex crops and commodities – and the corresponding dynamic and fluid commodity flows across sites of production, circulation and consumption – might undermine the efficacy of a sectoral approach to governance, because of the far more interlocking multi-sectoral nature of the phenomenon. This requires careful empirical research.

Implications for future research

The multiple-ness and flexible-ness of particular crops and commodities are crucial concepts for our understanding of the emerging politics around key crops and commodities in the changing global agrarian context. Flex crops and commodities are not inherently disadvantageous to poor people or to the environment. How it is produced, who controls the wealth produced from these commodities, and for what strategic purposes are politically contested questions. We know that agribusiness companies are economically and politically powerful, and are able to seize new opportunities to create profits, especially from their ability to invest in technological innovation (Jansen and Vellema Citation2004). But we still have little empirical knowledge about how all these get played out in the context of the recent phenomenon. We know just enough to make us confident that this is something worth further empirical investigation, further theorizing and jumpstarting political debates.

A research agenda should link political economy, political ecology and political sociology as the key fields of interest. The strategic central question is: how are capital accumulation, social relations and power relations contested and transformed within and through the emergence of the flex crop and commodity complex? This central research question can be disaggregated along, and can encompass, several themes:

Material bases

What are the material bases for, and policy narratives underpinning, new multiple and flexible uses, of which crops and commodities? What is the actual configuration of the political economic requirement for flexing, namely, the material basis, available technology and profit viability of key crops and commodities (including sugarcane, soya, palm oil, corn, sunflower, cassava, sugar beet, coconut and fast-growing trees)? What is the actual extent of crop and commodity flexing in each of these sectors? How does flexing actually happen? Who are the key players who decide how to read signals for flexing and when, where and how to flex? How do strategic ports of the world (e.g. Rotterdam, Singapore, Shanghai) play a role in terms of possible circulation – and flexing – points? Redesigning crops and/or further industrializing the processing stage may be crucial for further flexing. Of the many potential technological advances, which ones will be commercialized? How will they be strategically designed and selected to change power relations, especially by expanding a more flexible ‘value web’?

Real-life changes

What real-life changes (in resource property control, land and water use, production systems and so on) result from anticipated and/or imagined flexing in key crops and commodities? Who are the key players involved in anticipated and/or imagined flexing? When, where and how do they deploy these types of strategies? Who are the old and new corporate, financial and state actors involved in the emerging complex of flex crops and commodities, and why and how did they decide to engage in this new complex? Does finance capital favour particular types of flex crops and uses? If so, why, and how does this bias (re)shape agrarian structures and land-use practices?

Flex narratives

How do the multiple-ness and flexible-ness of boom crops and commodities allow governments and corporations to facilitate further capital accumulation in the boom crop sectors? How do they engage in flexible narratives around flex crops and commodities to legitimize their capital accumulation strategies? What is the state's role in facilitating the rise of flex crops and commodities – especially in facilitating the more flexible use of non-food biomass? What are the various manifestations and mutations of corporate and governmental ‘flex narratives’ on flex crops? What are the implications of flex narratives on international regulatory institutions within and between flex crop and commodity sectors? How do these different types of narratives influence the reality of financial investment in flex crops?

Political mobilisation

How does flexing positively and/or negatively affect the working classes and peasantries located in the sites of production, circulation and consumption of flex crops and commodities, rural and urban, in southern and northern countries? How does it affect struggles for livelihoods? How does flexing affect political mobilizations of agrarian and environmental movements for social justice? What are implications for non-governmental organizations (NGOs)’ roles in policy advocacy?

These are some initial questions to be taken up by engaged researchers. There are no ready, clear answers. Some of these questions have been answered partially and initially in the subsequent papers of this forum, e.g. by Oliveira and Schneider on soya; McKay, Sauer, Richardson and Herre on sugarcane; Gillon on corn; Fradejas, Liu, Salerno and Xu on palm oil; and Hunsberger and Alonso-Fradejas on policy narratives. Drawing on their preliminary answers, here we put forward new ways of asking and framing questions, rather than providing clear answers. A further step is to carry out empirical research that breaks through the silos of agricultural sectors and academic disciplines – towards a more multi-sectoral, inter-disciplinary collaborative research.

Acknowledgements

This paper emerged from a workshop on flex crops that was organized by the Transnational Institute (TNI) and held at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague in January 2014. We would like to thank the participants, including Ben White, Max Spoor and Esteve Corbera, for their critical and useful comments on an earlier, incomplete version of this paper. An earlier version of this paper appeared in the TNI working paper series on flex crops, in June 2014. We thank two JPS external peer reviewers for their critical but very useful comments and suggestions that improved the quality of our paper. The conceptual discussion draws from the very initial and highly abbreviated exploration of the notion of flex crops in Borras et al. (Citation2012).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Saturnino M. Borras

Saturnino M. Borras Jr. is a professor of agrarian studies at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, an adjunct professor at China Agricultural University in Beijing, and a fellow of the Transnational Institute (TNI) and Institute for Food and Development Policy (Food First). One of his recent articles is: Saturnino M. Borras Jr., Jennifer C. Franco and Sofia Monsalve Suarez (2015), ‘Land and food sovereignty’, Third World Quarterly. Email: [email protected]

Jennifer C. Franco

Jennifer C. Franco is an adjunct professor at China Agricultural University in Beijing and coordinator of the agrarian justice program at the Transnational Institute (TNI). One of her recent papers is: (2014) ‘Reclaiming free prior and informed consent in the context of global land grabs’, Amsterdam: Transnational Institute. Email: [email protected]

S. Ryan Isakson

S. Ryan Isakson is an assistant professor of international development studies and geography at the University of Toronto. With a focus on Mesoamerica, he has conducted research on peasant livelihoods and the cultivation of agricultural biodiversity, land reform and the financialization of food and agriculture. His current research projects focus upon the financialization of agricultural risk and the political economy of oil palm development in Guatemala. Email: [email protected]

Les Levidow

Les Levidow is a senior research fellow at the Open University, UK. His research topics have included the following: (un)sustainable development, agri-food-energy innovation, bioeconomy, agricultural research priorities, short food-supply chains, agroecology and European integration. He is co-author of two books: Governing the Transatlantic conflict over agricultural biotechnology: contending coalitions, trade liberalisation and standard setting (Routledge, 2006) and GM food on trial: testing European democracy (Routledge, 2010). Email: [email protected]

Pietje Vervest

Pietje Vervest is the programme coordinator of the Transnational Institute's Economic Justice Programme. She is an economic anthropologist and has specialized in the European Union's trade and investment policies. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1Agricultural derivatives have also been promoted as a means of managing price risk (Breger Bush Citation2012). Interestingly, farmers have been very reluctant to sell agricultural derivatives or purchase micro-insurance, leading economists to question their ‘irrational' behaviour (Binswager-Mkhize Citation2012; Da Costa Citation2014; Martin and Clapp Citation2015).

References

- Alonso-Fradejas, A. 2012. Land control-grabbing in Guatemala: The political economy of contemporary agrarian change. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 33, no. 4: 509–28. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2012.743455

- Alonso-Fradejas, A., J. Liu, T. Salerno, and Y. Xu. Forthcoming. The politics of palm oil flexing. Journal of Peasant Studies.

- Arrighi, G. 1994. The long twentieth century: Money, power, and the origins of our times. New York: Verso.

- Becoteps. 2010. Bioeconomy 2030: Towards a European Bioeconomy that delivers Sustainable Growth by addressing the Grand Societal Challenges. Brusssels: Bio-Economy Technology Platforms (Becoteps). http://www.epsoweb.org/file/560

- Bernstein, H. 2010. Class dynamics of agrarian change. Halifax: Fernwood.

- Binswager-Mkhize, H.P. 2012. Is there too much hype about index-based agricultural insurance?. The Journal of Development Studies 48, no. 2: 187–200. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2011.625411

- Birch, K., L. Levidow, and T. Papaioannou. 2010. Sustainable capital? The neoliberalization of nature and knowledge in the European Knowledge-Based Bio-economy. Sustainability 2, no. 9: 2898–918. http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/2/9/2898/pdf (accessed May 30, 2014). doi: 10.3390/su2092898

- Borras, S. 2007. Pro-poor land policy: A critique. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

- Borras, S., P. McMichael, and I. Scoones, eds. 2010. The politics of biofuels, land and agrarian change. London: Routledge.

- Borras, S., D. Fig, and S. Monsalve. 2011. The politics of agrofuels and mega-land and water deals: Insights from the ProCana case, Mozambique. Review of African Political Economy 38, no. 128: 215–34. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2011.582758

- Borras, S., J. Franco, S. Gómez, C. Kay, and M. Spoor. 2012. Land grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean. Journal of Peasant Studies 39, no. 3–4: 845–72. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.679931

- Breger Bush, S. 2012. Derivatives and development: A political economy of global finance, farming, and poverty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Clapp, J. 2009. Food price volatility and vulnerability in the Global South: Considering the global economic context. Third World Quarterly 30, no. 6: 1183–96. doi: 10.1080/01436590903037481

- Clapp, J. 2014. Financialization, distance and global food politics. Journal of Peasant Studies 41, no. 6: 797–814. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.875536

- Da Costa, D. 2014. The “rule of experts” in making dynamic micro-insurance industry in India. The Journal of Peasant Studies 40, no. 5: 845–65. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.857659

- DG R&I. 2014. Horizon 2020 Work Programme 2014-2015 on Food security, sustainable agriculture and forestry, marine and maritime and inland water research and the bioeconomy. Brussels: DG Research & Innovation, European Commission.

- Epstein, G. 2005. Introduction: financialization and the world economy. In Financialization and the world economy, ed. G. Epstein, 3–16. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- ETP Plants for the Future. 2007. European technology platform plants for the future: Strategic research agenda 2025. Summary. Brussels: EPSO.

- EuropaBio. 2007. Biofuels in Europe: EuropaBio position and specific recommendations. http://www.europabio.org/sites/default/files/position/biofuels-in-europe.pdf (accessed May 30, 2014).

- Fairbairn, M. 2014. “Like gold with yield”: Evolving intersections between farmland and finance. Journal of Peasant Studies 41, no. 6: 777–95. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.873977

- FAOSTAT. 2015. FAO Statistics. http://www.faostat3.fao.org (accessed and processed March 13, 2015).

- Franco, J. 2011. Bound by Law: Filipino rural poor and the search for justice on a plural-legal landscape. Manila: Ateneo de Manila University; Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Franco, J. 2014. Reclaiming Free Prior and Informed Consent in the context of global land grabs. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute (www.tni.org)

- Franco, Jennifer, et al. 2010. Assumptions in the European Union biofuels policy: Frictions with experiences in Germany, Brazil and Mozambique. The Journal of peasant studies 37, no. 4: 661–98. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.512454

- Ghosh, J. 2010. The unnatural coupling: Food and global finance. Journal of Agrarian Change 10, no. 1: 72–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0366.2009.00249.x