Abstract

Sustainable development and climate change mitigation policies, Dunlap and Fairhead argue, have instigated and renewed old conflicts over land and natural resources, deploying military techniques of counterinsurgency to achieve land control. Wind energy development, a popular tool of climate change mitigation policies, has consequently generated conflict in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Istmo) region in Oaxaca, Mexico. Research is based on participant observation and 20 recorded interviews investigating the Fuerza y Energía Bíi Hioxo Wind Farm on the outskirts of Juchitán de Zaragoza. This paper details the repressive techniques employed by state, private and informal authorities against popular opposition to the construction of the Bíi Hioxo wind park on communal land. Providing background on Juchitán, social property and counterinsurgency in Southern Mexico, this paper analyzes the development of the Bíi Hioxo wind park. It further explores the emergence of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ counterinsurgency techniques used to pacify resistance against the wind park, enabling its completion next to the Lagoon Superior in October 2014. Discussing the ‘greening of counterinsurgency’, this contribution concludes that the Bíi Hioxo wind park has spawned social divisions and violent conflict, and intervened in the sensitive cultural fabric of Istmeño life.

Introduction

On 24 February 2013, in the Seventh Section neighborhood of Juchitán de Zaragoza, the Asamblea Popular del Pueblo Juchiteco (APPJ) was formed. The next day, on the southwest outskirts of town, they went public with a barricade on the highway to Playa Vicente to halt the construction of the Fuerza y Energía Bíi Hioxo Wind Farm (). Then on 26 March, 1200 police came to break the barricade (Earthfirst! Citation2013). A member of the APPJ recounts the event:

When we left the barricade heading north, about halfway we saw between 26 or 30 buses of state police, then my sister said to me: ‘Let’s go back, let’s go back!’ And I told her, ‘No, we have to keep going – stay calm’. She continued: ‘They are going to arrest you’, and I answered, ‘No, keep walking’. Then we got in my truck and we drove past the police convoy, arriving to a place called El Tanque. When we arrived in town, most of the neighbors were standing on the road – there were a lot. People were all over the road asking: ‘What can we do? What can we do?’ [A] neighbor close to me asked what to do, I told him: ‘Grab rocks, grab sticks, and anything you can to block the road, because they already passed, but they are going to need this road to get out and then they will be fucked’. To the other compañeros who were wondering about what to do, I told them to go to the loudspeakers in the town to make the announcement, and I went to do the same. I went downtown where the speaker is higher, so I called from there and said: ‘Now is the time! We have to defend our land, we have to defend our territory. My fellow countrymen, women, kids, elders and men grab everything you can: sticks, rocks, machetes and anything to defend our barricade!!’ So, the mayhem starts. People came from the Fifth Section and downtown; they were young people, women, and children. Some women, even those who were identified for belonging to the [local leftist political party] Isthmus Coalition of Workers, Peasants and Students (COCEI)Footnote1 tied their chals Footnote2 on their waist as if it was a ceñidor Footnote3 so they could fill it with rocks and with that they were running to the highway.

The police shot teargas and slingshots because some of them are from Juchitán. And the people were defending themselves with anything they had: stones, throwing sticks, etc. The police tried to recover their vehicles, they couldn’t. The people saw them coming, burned a truck, and started fighting them. There was barbaric fighting. When the police tried to take back their vehicles from the barricades and run away, the people attacked them with stones and made them get out of the vehicles and run into the field. They ran towards Unión Hidalgo and left their shields – we picked up around 40 shields that the police abandoned. At night, somebody told us that the police were picked up around Union Hidalgo by the military because some of them were naked in order not to be identified as police.

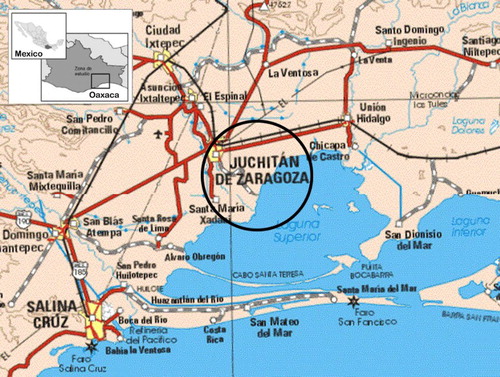

Figure 1. Map of the Costal Isthmus of Tehuantepec, adapted by author from University of Texas Libraries.

The account above offers a glimpse into the level of conflict and resistance generated by wind energy projects in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region of Oaxaca Mexico, known locally as the Istmo. This case fits a wider, well-documented pattern of so-called ‘green grabbing’ (Vidal Citation2008; Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2012) that describes how land is grabbed and controlled in the name of an environmental ethic to promote sustainable development and climate change mitigation programs (Peluso and Lund Citation2011), which has reignited old and created new conflicts over land and natural resources. Furthermore, it illustrates how, as argued by Dunlap and Fairhead (Citation2014), there is a history and continued reliance on military techniques of counterinsurgency to advance resource control and industrial development in ecologically diverse and sensitive areas (Peluso and Vandergeest Citation2011). This reliance on counterinsurgency and other militarized techniques has been particularly well documented in relation to nature conservation, as captured in the notion of ‘green militarization’, defined by Lunstrum (Citation2014, 817) as ‘the use of military and paramilitary (military-like) actors, techniques, technologies, and partnership in the pursuit of conservation’. Büscher and Ramutsindela (Citation2016, 3) extend green militarization to a wider notion of ‘green violence’, describing the material, social and discursive dimensions as well as the longer histories of violence and militarization in a particular region and its conservation areas.

As this contribution shows, green militarization and violence is not limited to conservation parks, but can be found with any project utilizing an environmental rationale and repressive techniques to impose its existence on an entire (or segments of a) population and the spaces they inhabit. This paper thus builds upon the notion of the greening of counterinsurgency outlined by Dunlap and Fairhead (Citation2014), which roots ‘green violence’ within a specific military doctrine and history emerging from asymmetric colonial wars that has become increasingly popular, gaining widespread application within militaries (Owens Citation2015), police departments (Williams Citation2007; Williams, Munger, and Messersmith-Glavin Citation2013), resource extraction companies (Rosenau et al., Citation2009; Javers Citation2011) and even marketing agencies (Copulsky Citation2011). Not only does counterinsurgency establish a strong historical link with previous military, paramilitary and police operations within a region, but it also unravels the ‘conflict management’ approaches of dominant public, private and non-governmental actors (Verweijen and Marijnen Citation2016; Duffy Citation2016; Dunlap and Fairhead Citation2014; Peluso and Vandergeest Citation2011). The following case of Bíi Hioxo wind park illuminates the relevance of adopting counterinsurgency as a lens to analyze efforts to break popular opposition to wind energy development in the name of mitigating anthropogenic climate change.

Research on the Bíi Hioxo wind park emerges from a wider study on wind energy development in the Istmo based on participant observation and 123 recorded informal and semi-structured interviews. Twenty interviews from this pool focused directly on the Bíi Hioxo wind park and were largely concerned with the perspective and experience of those resisting its development. The semi-structured interviews asked open-ended questions about people’s experiences, the actors involved and the repressive tactics used during wind park development. This research was conducted with an interpreter with ties to the resistance, referred to in the text as a ‘friend’ because during this research they were more than an interpreter. Fieldwork included tours of wind park affectations, fishing trips and joining a pilgrimage to a religious site as well as participating in local ceremonies. Fieldwork abruptly ended after five months due to repression related to embedding and participating in the resistance groups in the region. Because of the conflict in this region, preserving research participant confidentiality is a priority in this contribution.

To understand the research context, it is important to outline the types of resistance in the area. The struggle against wind energy in the Istmo is diverse, and unequally distributed. There are factions fighting for wind turbines, notably politicians, land elites and unions, and there are tendencies of resistance that resonate with the two types identified by Borras et al. (Citation2012), namely those against exploitation and those against dispossession. First, there are people who are not necessarily against wind energy development, but are against exploitative land deals, advocating, in areas already subject to wind energy parks, for increases in social development, employment, profit-sharing and (heavily) subsidized or free electricity. In prospective wind energy sites, this takes the form of struggling for community wind farms (Oceransky Citation2011). Second are those fighting against dispossession – taking the insurrectionary stance of total rejection and (relative) non-cooperation with the wind companies, state government and regional security forces. Cooperation with authorities is generally limited to a concerted legal strategy.

Interviews for the Bíi Hioxo wind park were largely concerned with the factions in total rejection. As highlighted by Bebbington et al. (Citation2008, 2890), ‘the cultural and psychological losses that might arise when livelihoods are disarticulated’ create opposition. Similar to other contexts, resistance groups in the Istmo, especially the APPJ, ‘explicitly and deliberately recur to cultural symbols to strengthen and legitimize their case’ to express livelihood and cultural disarticulation felt from the arrival of the wind park (Salman and Assies Citation2007, 212). By listening to the experience, stories and outlook of those resisting the wind project, the aim was to understand the conflict, why people are opposing the project, as well as the obstacles faced by the resistance movement. Emerging from these in-depth interviews were signs of repression against wind park opponents that echoed the approach advised by counterinsurgency manuals, which came to provide the lens to examine the Bíi Hioxo wind park.

This paper proceeds as follows. First, it provides some historical background on the Istmo and the Bíi Hioxo wind park. The next section moves into a review of counterinsurgency warfare and its more subtle property-based approaches deployed in Southern Mexico. After this, the paper turns to the arrival of the Bíi Hioxo wind park on the communal land south of Juchitán. The subsequent section then examines the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ counterinsurgency techniques used to combat resistance and complete the wind park. The piece ends by concluding that the deployment of counterinsurgency techniques appears to aggravate the violent social divisions and cultural change caused by Bíi Hioxo in the Istmo, which serves to reinforce larger trajectories of political violence and industrial degradation in the face of existing ecological crises.

Background: Oaxaca, Istmo and the Bíi Hioxo wind park

Oaxaca is the second poorest state in Mexico after Chiapas (CONEVAL Citation2015). It has 570 municipalities, 418 of which are governed by an indigenous form of governance – usos y costumbres Footnote4 – based on consensus decision-making in communal assemblies (Stephen Citation2002; Altamirano-Jiménez Citation2014). It also has the largest indigenous populations in Mexico, with 16 different languages and the greatest concentration of social property (77.6 percent) – ejidos and communal land (Gobierno de Oaxaca Citation2011). The Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Istmo) is one among seven principal geographical regions in Oaxaca.Footnote5 According to the 2003 United States Agency for International Development-sponsored report Wind energy resource atlas of Oaxaca (Elliott et al., Citation2003), the region has excellent wind resources and is now considered ‘home to some of the best wind resources on earth’ (IFC Citation2014, 1). By January 2015, the region had 1608 wind turbines (Rivas Citation2015). While wind turbines are predominately concentrated in the northern part of the Coastal Istmo, since 2005 there have been plans to spread wind turbines south across the entire region, placing them on and around the semi-subsistence farming and fishing communities of the Lagoon Superior and Pacific Ocean.

Planning for the Bíi Hioxo wind park formally began in 2006 and it was among the first wind parks planned, eventually becoming the only park constructed on the Lagoon Superior, in October 2014. This wind park became the third largest in Latin America, with 117 wind turbines and a capacity of 234 megawatts (MW; CDM Citation2012; GNF Citation2013a). It was registered with the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) as ‘it will make a positive contribution to the protection of and care for the environment, directly addressing problems of climate change’, which ‘does not require extraction, drilling, transport of fuel or water consumption, and does not generate polluting dangerous or radioactive waste’ (CDM Citation2012, 2). Spread over 2050 hectares of disputed and sought-after communal land (comunales) by land owners, government and corporations (Rubin Citation1997), the Bíi Hioxo wind park is also among the ‘self-supply’ (autoabastecimiento) wind parks in the region (CDM Citation2012). Self-supply electricity is private, generated and reserved for the investors or co-owners of the project: Gas Natural Fenosa (GNF), Cementos-Moctezoma construction, Tiendas Chedrahui superstores and Saint-Gobain México industrial construction company, among others (CODIGODH Citation2014; CDM Citation2012). The leading investor, Gas Natural Fenosa, is a member of the United Nations (UN) Global Compact – ‘the world’s largest corporate sustainability initiative’ – and is valued by ‘the main sustainability indices’ (UNGC Citation2014). It claims to maintain ‘its firm commitment to respect for human rights and specifically the traditional ways of life’ (GNF Citation2014, 6, 224). As further explained below, it is a widely held perspective among those engaging in resistance in Istmo that these claims are not honored.

Counterinsurgency, social property and indigenous people in Southern Mexico

Counterinsurgency, Kilcullen (Citation2006, 29) writes, is ‘a competition with the insurgent for the right and ability to win the hearts, minds and acquiescence of the population’. Here, winning ‘hearts’ is explained as ‘persuading people their best interests are served by your success’, and winning ‘minds’ means ‘convincing them that you can protect them, and that resisting you is pointless’ (Kilcullen Citation2006, 31). Counterinsurgency is a type of war – ‘low-intensity’ or ‘asymmetrical’ combat – and style of warfare that emphasizes intelligence networks, psychological operations (PSYOPS), media manipulation and, finally, security provision and social development that seek to maintain governmental legitimacy (FM3-24 Citation2014). Williams (Citation2007) makes the distinction between ‘hard’ (direct) and ‘soft’ (indirect) practices of counterinsurgency that work together in larger strategies of population control. ‘Hard’ techniques – the proverbial ‘stick’ – include overt political violence by police, military and mercenary forces, while ‘soft’ techniques – the ‘carrot’ – are civil–military operations that invest resources and technologies into ‘underdeveloped’ or ‘troubled’ areas. ‘Soft’ interventions are commonly referred to as civilian assistance and community development, including foreign aid provided to collaborating local elites to stabilize and manage areas of interest. Notably, the deployment of these ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ techniques often necessitates the establishment of proxy forces or a type of ‘decentralized household rule’ that work within specific political and cultural contexts (Owens Citation2015, 8). Within rural Mexico, for instance, this meshes with the (patriarchal) authoritarian corporatism(s) characteristic of many regions (Mackinlay and Otero Citation2004).

Counterinsurgency takes on a totalizing approach, seeking to monitor and engineer entire populations, and make them internalize particular values and worldviews. In other words, counterinsurgency is the art of population control, which seeks to colonize and incorporate the people and natural resources into the projects of dominant actors. These are not limited to nation-states and regional governments, but also include (trans)national resource extraction companies. Indeed, through public or private security forces, counterinsurgency warfare techniques play an integral, if overlooked, part in the operations of resource extraction companies (Rosenau et al., Citation2009; Downey, Bonds, and Clark Citation2010), which sometimes are even calculated into cost–benefit analysis ratios (Caselli and Cunningham Citation2009). At a 2011 oil conference in Houston, Texas, Matt Carmichael, manager of external affairs for Anadarko Petroleum, recommended to public relations experts to ‘[d]ownload the US Army-slash-Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Manual’, calling opposition to hydraulic fracturing in the US ‘an insurgency’ (Javers Citation2011). Echoing Carmichael, Matt Pitzarella says: ‘We have several former psy ops folks that work for us at Range [Resources] because they’re very comfortable in dealing with localized issues and local governments’ (quoted in Javers Citation2011). The latest Counterinsurgency Field Manual 3-24 (FM3-24 Citation2014, 1–2, emphasis in original) explains:

When a population or groups in a population are willing to fight to change the condition to their favor, using both violent and nonviolent means to affect [sic] a change in the prevailing authority, they often initiate an insurgency. An insurgency is the organized use of subversion and violence to seize, nullify, or challenge political control of a region.

Counterinsurgency initiatives have led governments as well as resource extraction companies to view civil dissent, non-violent social movements and organized opposition as insurgent or proto-insurgent, where they apply various mixtures of consent and coercion to defuse group formations or their militancy (Dunlap Citation2014).

Counterinsurgency in Mexico

Mexico has a gruesome history of civilian-targeted low-intensity warfare during the Cold War (Arronte, Castro-Soto, and Lewis Citation2000), which re-emerged and reinvigorated visions of rural threat with the 1994 Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas, the 1996 debut of the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR) in Oaxaca and the subsequent War on Drugs (Norget Citation2005). The Mexican government responded by restructuring the country around military-centered internal security imperatives of counterinsurgency (Arronte, Castro-Soto, and Lewis Citation2000; Stephen Citation2002). Between the years 1978 and 1998, no less than 4172 Mexican military personnel received training overseas, the majority of whom (61 percent) were trained in 1994. Many of them were trained at the School of the Americas (SOA) and other academies of scientific violence specializing in counterinsurgency, torture and other unsavory techniques (Arronte, Castro-Soto, and Lewis Citation2000). This development coincides with a policy to actively blur the line between the police and military with the creation of the Federal Preventive Police (PFP) in January 1999, who specialize in targeting civil dissent (Arronte, Castro-Soto, and Lewis Citation2000). In 1997, Oaxaca State began embracing a comprehensive counterinsurgency plan detailed in a document titled: Oaxaca: the conflict and the project (Arronte, Soto, and Lewis Citation2000, 73). This plan promoted interagency command and control from military, federal and state police to counter guerrillas, but also to pre-empt the growth of social unrest arising from the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and other government policies (Arronte, Castro-Soto, and Lewis Citation2000, 73–80). Summarizing this program, Arronte, Castro-Soto, and Lewis (Citation2000, 78) write, ‘the government’s actions in Oaxaca are not geared toward combating poverty, but rather toward counterinsurgency maneuvers, through the use of publicly funded projects such as the “Microregional Fund,” and the media’. Low-intensity warfare operations have now become generalized and reached unprecedented levels under the War on Drugs, which Paley (Citation2014) argues is actively used to repress civil dissent arising from the unpopular government policies, which include efforts to assert control over and further integrate social property into the national economy.

Social property is often perceived by the Mexican government not only as a barrier to economic growth, but also as spaces harboring illegal activity and potential insurgents (Bryan and Wood Citation2015). In the Istmo, social property – ejidos and communal land (comunales) – have been a source of conflict for more than a century between and among different tiers of the Mexican government, private companies, land owners and social movements, the most notable of which was the COCEIFootnote6 who eventually came to power in the region in 1981 (Rubin Citation1997). Originating from Article 27 of the 1917 constitution, ejidos provided land for farmers to cultivate, but not to buy and sell – something that began to change after alterations to Article 27 in 1992 (Assies Citation2008). Ejidos are allocated for residential and agricultural use and governed by local assemblies – traditionally constituted by male heads of the household – while ‘direct ownership of all natural resources’ below ejido topsoil was reserved for the Mexican government (MG Citation2007, 19). Communal land, on the other hand, is related to pre-colonial land claims. Like ejidos, it is governed by the community with varying rules and relationships according to regional customs and practices, and mostly held in comunidades agrarias (Stephen Citation2002), although internally often treated as private property (Binford Citation1985). Unlike ejidos, communal land has a different legal status that allows a greater degree of autonomy to Indigenous groups over their governing structures and natural resources. Importantly, communal land has served as a barrier towards public and private development projects, which has resulted in a variety of programs and interventions to better manage and integrate these lands into the political economy of Mexico (Payan and Correa-Cabrera Citation2014). In this respect, it is important to note that while ‘only about 5% of the land in Mexico was held under communal tenure in 1960’, ‘38% of the Oaxaca land was so administered’ (Binford Citation1985, 180–81).

The trend to officially break down social property begins with the 1992 Article 27 revisions that legalized the privatization of social property and introduced the Program for the Certification of Ejido Rights and Titling of House Plots (PROCEDE)Footnote7 that sought to survey, map and register social property (Assies Citation2008). Lasting until 2005, PROCEDE was met with varying success: 100 percent coverage in the northern states of Guanajuanto and Colima, while predictably less in southern states, with Guerrero certifying 65 percent of their social property, Chiapas 43 percent and Oaxaca 39 percent (Assies Citation2008). The attraction to PROCEDE was simultaneously intertwined with a ‘culture of fear’ generated by state agencies to convince individuals to have secure titles and guard against inter-communal land grabs (Osborne Citation2013, 125). Furthermore, it created the prospects to sell, rent and use the ejido as collateral to access farming credit, social welfare and development schemes such as Programa Nacional de Solidaridad, Programa de Educación, Salud y Alimentación (1994–2000) and Oportunidades (2000–2006) (Assies Citation2008). However, PROCEDE also sought to collect information on rural communities and create the possibility of privatization (Stephen Citation2002; Bryan and Wood Citation2015). This development has intensified with the recent adoption of the Energy and Utility Act (2013) that mandates that social property holders must negotiate and eventually surrender their land to energy companies in regions of development interest (Payan and Correa-Cabrera Citation2014). While the results of this legislation are only beginning to emerge, analysts see conflict on the horizon (Payan and Correa-Cabrera Citation2014).

While PROCEDE reached its potential for titling, classifying and extending government control over natural resources in many areas, the tension to make social property legible continued with two different, yet mutually reinforcing, strategies of what Bryan and Wood (Citation2015, 149) call ‘property based approaches to counterinsurgency’. First was the 2006 US military-funded México Indígena, a ‘participatory mapping’ project that sought to document native territory and rights to provide land tenure security for residence as well as contribute to the ‘open source intelligence’ of rural areas around the world (Boyce and Cash Citation2013, 245-6). This project was coordinated by Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Demarest, led by Dr. Peter Herlihy and carried out by a team of geographers from the University of Kansas. This research team set off into the Zapotec Sierra Juarez region of Oaxaca to finish what PROCEDE could not, offering mapping jobs, geographic information systems (GIS) training, free computers and updated maps for towns (Bryan and Wood Citation2015). According to locals, those implementing the project failed to mention that this ‘Bowman Expedition’ was sponsored by the Fort Leavenworth Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO), the Mexican Government and the American Geographical Society (AGS) with USD 2.5 million, with the intention ‘to gather intelligence on emerging and asymmetric threats to the United States for the purpose of preparing for conflict and maintaining “peace”’Footnote8 (Finn et al., Citation2014; Boyce and Cash Citation2013, 245). Through a local intermediary, Gustavo Ramírez, the towns Tiltepec, Yagila and Yagavila began working with the expedition. However, at the start of 2009, once people realized what was being produced and became aware of the military’s involvement, individuals and collectives started to denounce this project (Bryan and Wood Citation2015). Commenting on the ‘recent attempts to create world-wide property databases’, resident Melquiades Cruz writes,

this mapping occurs in the midst of the debate over a package of military financing from the United States known as the Mérida initiative. The control and displacement of indigenous communities is intended to prevent potential conflicts in ‘hot spots’, contribute to the military control of the region, and finally free up natural resources for the benefit of the government and its transnational allies. (quoted in Bryan and Wood Citation2015, 144)

The second property-based approach to counterinsurgency emerges indirectly with Mexico’s national payment for ecosystem services (PES) program. While grassroots movements have adapted and use Mexico’s PES programs to their benefit (McAfee and Shapiro Citation2010; Shapiro-Garza Citation2013), arguably PES can serve a secondary purpose of rural pacification, putting aside the contentious notion of PES quantifying and constructing the natural environment as a ‘service provider’ commensurable with financial markets (Sullivan Citation2009, Citation2013). The Mexican National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR)Footnote9 made enrollment in PROCEDE a mandatory prerequisite for participating in PES that creates new real or imagined benefits for farmers (Osborne Citation2013). However, the related control and financialization of the natural environment can become intertwined with regional counterinsurgency strategies that in Chiapas have worked to blunt the Zapatista movement (Bartra Citation2007; Osborne Citation2013). ‘In particular state agencies have used conservation and development projects as a kind of counter-insurgency strategy within the Lacandon region’, writes Osborne (Citation2013, 126), making ‘participation in forestry programs, such as PES, contingent on the certification of communal lands’. The economic development associated with land certification, expanding roads, plantations and constructing model villages (‘Rural Cities’) in areas of rural poverty are used to win the ‘hearts’ and ‘minds’ of locals, which also attempt to erode Zapatista territory, confine it within the grid of industrial development and thereby mitigate revolutionary violence (Wilson Citation2013). The deployment of green economy initiatives with market-based conservation (PES, REDD+Footnote10), luxury eco-tourism resorts (Agua Azul) (Rocheleau Citation2015) and other schemes works indirectly to undermine insurgent groups’ legitimacy by ‘exploiting the root causes of conflict’ by providing a series of development initiatives and jobs to unruly areas, which operate alongside coercive measures associated with state and extra-judicial forces (FM3-24 Citation2014, 10–1).

Green economy initiatives have the potential to not only aid market growth, but also work in accordance with state stabilization strategies that seek to create predictable environments for civil and security sectors to manage rural populations. Even the recent counterinsurgency manual (FM3-24 2014, 10–1, 2) openly advocates ‘promoting sustainable development’, and ‘education, empowerment and participation’ as foundational to mitigating violence and promoting ‘long-term regional stability’. Counterinsurgency is designed to be adapted to local interests, demands and divisions, which are in turn conditioned by larger processes of economic policy, (trans)national investment, and the federal and state counterinsurgency programs that shape the practices of locally deployed security services. These larger population management and investment protection strategies trickle down and are adapted into patronage networks, appearing as job opportunities, ‘dirty work’ or even community development initiatives. Importantly, counterinsurgency aims not only to find social divisions, but also to create and exaggerate them in order to blur the line between counterinsurgency and inter-communal conflict (Bartra Citation2007). This is particularly relevant to the existent paramilitarism in Oaxaca and the Istmo that is intertwined with the practices and interests of local political elites and industrialists as well as the federal and state security imperatives (Arronte, Castro-Soto, and Lewis Citation2000; Stephen Citation2002, Citation2013; Norget Citation2005). Responses to the resistance against the construction of the Bíi Hioxo wind park illustrate these dynamics.

From death squads to arriving wind turbines

As the story goes, some of the same Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) politicians, industrialists and gunmenFootnote11 involved in putting down the Oaxaca insurrection (2006) were also instrumental in preparing the way for wind parks in the Istmo. These Oaxacan elites recruited people from the Seventh Section neighborhood in Juchitán and all over the country for the ‘caravanas de la muerte’ (caravans of death), which was a death squad formed to break the barricades and five-month-long occupation of Oaxaca City in 2006 (Stephen Citation2013).Footnote12 Select individuals and networks associated with organizing these paramilitary groups, in the past and present, have worked with the wind companies to regularize and invade social property around Juchitán. People interviewed repeatedly claim that the arrival and security of the wind park was managed by local elites – land owners and politicians. FM 3-24 advises ‘to quickly and accurately identify the various community leaders and develop strategies to work with them’ (Citation2014, 3-4). According to interviews in Juchitán, wind companies negotiated with ‘political representatives’ – formal and informal – paying them anywhere from 17 million to 28 million pesos (if not more) to allow the development of wind energy parks. Exactly how much and where this money was spent remains disputed and unknown. This, however, hints at the conflict between the civil populations and governments, wind companies and political authorities, and between the different political authorities – COCEI, PRD and PRI – collaborating with the wind company in the region.

On 17 June 1964, 68,112 hectares of communal land in Juchitán were officially recognized by presidential decree, which ever since has been a source of struggle and controversy between comuneros, land owners, the state and private companies trying to lay claim to the land (Rubin Citation1997). Currently the issue of communal land outside Juchitán remains unresolved, making the arrival of the Bíi Hioxo the latest controversy on these lands (CODIGODH Citation2014). The uncertain legal status of communal lands and support of regional elites has led the wind company to approach comuneros – the holders of communal land – to negotiate individual contracts.

Wind park consultation began, according to the CDM document, at the House of Culture in Juchián in February 2008. People were ‘invited to the meeting via loudspeaker in the urban areas where most owners live’ with an attendance of approximately ‘50 owners’ (CDM Citation2012, 43). The second meeting was in September 2009, where ‘[e]ach owner received a personalized invitation at his home’, which resulted in approximately 160 owners attending the meeting. Finally, the third meeting took place on 6 December 2011, with personalized invitations for land owners and approximately 155 owners attending (CDM Citation2012, 44). The CDM document makes it clear that the wind company preferred land ‘owners’, failing to consider the rest of the population. The wind companies and regional authorities were also selective with information distribution. A 70-year-old fisherman recounts:

[N]obody knew about the signing of the contract, they did not ask the community – they did not go house to house like when they are [ … ] campaigning for an election, they go house to house delivering their message. But, as for the signing of the [wind park] contract, they never got around to asking the people, and the people did not give their consent to the construction of that park. Because there was money that the politicians received, but how come upon receiving that money they did not tell the people. So, it was built because nobody was asked.

The takeover of communal land has sparked controversy. When heavy machinery began preparing the way for wind turbines by moving in to clear trees and brambles, building new and fortifying old roads, it caused shock and scandal. As a woman commented,

what the business people say is a nasty lie – that it is clean energy, that it is green energy. But how could it be green if it is devastating the trees that provide us with oxygen. It pollutes our ground water. It eliminates alternative natural medicine, which we receive through the animals and plants that are in all the areas where the wind energy companies have invaded.

These changes, as well as resistance against them, were viewed through the lens of cultural symbolism and spiritual imaginaries. As one person, called the ‘Wild Tiger’, explained in relation to the Zapotec religion before the Spaniards arrived, this ‘was a religion that used to worship the sites’, such as ‘the sea, the lagoons, swamps, and hills where people would go, for example, to ask for rain. There is the god of rain, the god of corn production; the god of the wind and all of nature to us is something sacred’. Hence, the takeover of communal land has serious cultural implications. Moreover, it is home to seven sacred sites where people make pilgrimages to pray, to have contact with nature, to relax, to socialize and to share the harvest of the year. Among these are the tombs where Zapotec warriors resisted the Spanish in Guze Venda, Guela Venge, Chigueze and La Chxaada, in Paso Cruz.Footnote13 A woman member of the APPJ explains:

When you enter Guela Venge, now the main entrance to that chapel is blocked by the wind energy project. They no longer let people freely enter there. There are people that go there to pray, there are spiritual sisters that go to do their rites there, and they are no longer allowed to enter in that area of Guela Venge. In Guce Venda, because of the resistance of the APPJ, people can still enter there, but the company had intended to close that off. Why? Because they started to block near Chigueze, they did not want farmers who had not signed on with the company to go through there. That is where the APPJ started. Yes, because they were farmers and fishermen who wanted to go through there and they were told that they could go through, but only with a badge on.

These changes in life worlds and livelihoods have provoked resistance. The first expression of this occurred when farmers were restricted from using communal roads. Control over the communal roads provided a glimpse into the life the wind companies would deliver. ‘The farmers would ask the operators of the machinery for permission to go through and they would say, ‘“No. The company has already signed a contract”’, which gave construction crews the legal right to work and deny farmers access to their land. One day, this led to confrontations between farmers and fishermen and road construction crews over a tractor that almost turned into a violent brawl. While the tractor blocking the roads was eventually moved, this event served to raise awareness about the existence and changes brought by the wind company.

Direct action against the project continued. Before the forming of the APPJ to halt the wind park, the erection of the barricade (as described in the introduction) and subsequent interest from human rights organizations around this issue, people tried to take action into their own hands. This evoked violent repression. When asked the clarifying question: ‘Essentially what you are telling me is that this wind park was built here with people guarding it with assault rifles?’ a farmer replied:

Yes! For example over there [pointing], we came and chased them [the guards], but because they have weapons, they started shooting at us – ‘Bow! Bow! – Bow! Bow! Bow!’ – and one of the bullets hit really close to me and we started running, but they took a kid. Then a lady that came with us and all the ladies that were strong started yelling at them: ‘Release him! We did not come to fight with weapons, we just came to try and stop these wind turbines from being here’. And one of them [the gunmen] took his pistol and started shooting – Pow! Pow! Pow! – but he didn’t hit anything and he ran out of bullets. So the other guy handed him a knife and started saying, ‘Kill him! Kill him! [holding the kid]’, but he didn’t want to and the other one kept yelling, ‘Kill him! Kill him now! Kill him!’ So the kid was really scared, but he was really lucky that the ladies took him back, they took him from those guys’ hands, but he ended up with his t-shirt ripped.

AD: How did the women grab him from the gunmen?

Pulling him. One of the women started yelling, ‘Kill me and you will realize that we do not have weapons, but you are not going to take this kid anywhere to kill him’. So we stayed away [from the gunmen], and nobody was allowed to pass [to the communal land]. So we made a barricade; they paid the gunmen to burn it.

Divide and conquer: counterinsurgency for wind energy

The strength and militancy of the anti-wind energy social movement in Juchitán and other parts of the Istmo no doubt constitutes a threat to existing and future wind energy development. This section reviews the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ counterinsurgency techniques applied to overcome this resistance by GNF and their collaborators within the Mexican government, regional elites (caciques) and their networks.

Hard techniques

The security forces operating in Juchitán are diverse. There is military, navy and federal police presence, which combines with state, municipal and PABIC police. At the same time, there are roughly three types of mercenaries: (1) local gunmen, who know or in some cases are related to the people struggling against wind turbines; (2) Mexican gunmen from other parts of the country; and (3) gunmen who look like foreigners – ‘whites’ – that are rumored to be imported by the wind companies. In the struggle against the Bíi Hioxo wind park a variety of repressive techniques have been documented by the Comité de Defensa Integral de Derechos Humanos Gobixha (CODIGODH Citation2014, 26–28):

Police harassment and brutality;

Death threats (in person and by phone);

Home surveillance;

Constructing informant networks;

Firing guns in front of homes;

Breaking into and vandalizing homes and community radio stations;

Attempted kidnappings;

Illegal detainment (held hostage) by police;

People being followed around town and after public events;

Burning ranch land;

Burning barricade camps (three times);

Assassination.

On 19 May 19 2013 a farmer was shot working his field, while on 21 July 2013, after he left a party, APPJ member Hector Regaldo Jiménez was shot six times. Badly wounded, he was rushed to a hospital where he identified two men and a member of the PABIC as the perpetrators, thereafter passing away on 1 August (CODIGODH Citation2014). Many attackers are well known ‘because sometimes the people who threaten us are our families or cousins at the service of Pulpo’, as one person explained. Families were divided and people in opposition to the wind park were systematically intimidated, harassed and even put under gunfire. One farmer associated with the APPJ commented:

When I would go out to lead my cattle to graze and give them water, people would shoot at me. It is a threat; they were trying to intimidate me.

AD: Did they shoot in the air or at you?

At me, I had to run. I know all of the land around here.

AD: How many times has that happened?

[ … ]

Four times.

The wind company also recruited gunmen from the barricade. ‘The wind energy companies sucked them in with money, and they armed them and turned them against us’, explains a fisherman who described how they harass him when he is on communal roads. ‘They use killers from this neighborhood and they also use them to tear apart our assembly – they use our very own compañeros that use to be part of the assembly [APPJ] and then bribed them with money’, explained another man. He continued, ‘among them is one of my uncles – a brother of my father – who has also received money from the [wind] companies and with that took some compañeros with him’. Another person summarizes: ‘They are given money, they are given weapons, and they do not have to work hard, so they join the company’. Indeed, buying and flipping people emerged as a recurring theme in resistance against the wind energy park here and in other parts of the Istmo.

Members of the APPJ felt that people claiming to be ‘human rights defenders or members of collectives or from some university’ were hanging around, trying to gather information and ‘look who the leaders are’, which they thought was funny as there is no leader within these collectives. Furthermore, a range of disruptive tactics were employed to isolate and break up the APPJ. For instance, it was reported that collective members were bought off and stole the APPJ contact list along with Radio Totopo’s equipment. Another tactic was the spread of rumors about people in the APPJ. Notably, about two months into my research, someone began spreading rumors that my friend and I were police informants. Not using our names, this person described the two of us, claiming that he had ‘received information from Chiapas that we were infiltrators’. Later this intensified with a ‘leak’ from the Salina Cruz courthouse that told people in the resistance that I was a police informant, while at the same time I was being harassed and attacked by a state-sanctioned mercenary group in Álvaro Obregón calling themselves the Constitutionalists.Footnote15 These directly repressive tactics were enacted in tandem with what appear to be ‘soft’ counterinsurgency techniques that encourage the dissolution and fragmentation of the opposition to the wind energy park.

‘Soft’ techniques

The section titled ‘Integrated monetary shaping operations’ (IMSO) in the chapter ‘Indirect methods for countering insurgencies’ in FM3-24 (Citation2014) best describes the tactics employed around the Bíi Hioxo wind park. IMSO implies distributing money to socially engineer the political terrain to garner legitimacy for governments, security forces or, in this case, a development project. After the barricade battle, a study was conducted titled Perceptions of the wind energy park in Juchitán, Oaxaca (GNF Citation2013)Footnote16 where, according to the study:

Gas Natural Fenosa needs to implement marketing strategies to understand the Juchitán, Oaxaca population’s perception of the Parque Eólico Fuerza y Energía Bíi Hioxo with the goal of introducing possible solutions to deactivate the social movements that have arisen around this project. (emphasis added)

To engineer support, the wind companies organized a cadre of fishermen to attend public events and speak in support of the Bíi Hioxo wind park. There are two principal groups with a total of around 250 members supporting wind parks in the area. The Oaxacan state Secretary of Indigenous Affairs provides them works under a ‘Temporary Work’ program as well as fishing equipment: boats, motors, nets, weights and fishing line. Many of these people, however, are not fishermen or do not fish anymore. According to people interviewed, these ‘fishermen’ go to towns on the Lagoon Superior and sell their new equipment, worth around 800 pesos, for 200. People resisting wind projects feel these fishermen groups, who openly support the wind companies for money, were created to counter wind park opposition groups. The creation of counter-fishing groups mimics counterinsurgency tactics that purposely seek to create and exaggerate social division that echoes the paramilitarism well known in Oaxaca and Chiapas (Arronte, Castro-Soto, and Lewis Citation2000; Norget Citation2005).

Another method employed to win ‘hearts’ and ‘minds’ is social development projects. While negotiations with the wind company for social development have been going on for a long time, it was not until 2013 and 2014 that these projects manifested. Adhering to points eight and six of IMSO that stress the importance of ‘[P]urchasing education supplies’, providing ‘education to the local population’ and ‘[R]eparing civic and cultural sites’ because ‘cultural heritage is a sensitive issue’ (FM3-24 Citation2014, 10–12), the wind company has provided computers for schools, funded reforestation campaigns and supplied medicines, household appliances and food. Additionally, it has repaired cultural sites, fixed an irrigation canal and, I am told, contributed with other wind companies to developing electrical engineering classes at the Technical Institute of the Istmo. Likewise, the wind company has engaged in church restoration, while simultaneously denying access to cultural and spiritual sites. While welcomed by some, these social initiatives also generated outrage. According to friends and family, when teachers brought their classes to go plant trees and take photographs, some students protested and refused. One boy proclaimed to his teacher that the wind companies are ‘fooling the people and stealing their land’ with this project, while another girl echoed: ‘No! They are fooling the people and the kids this way’. They explained to their teacher that the kids and the subsequent photographs were being used to show that the wind company ‘is helping people, but it really is not true’.

These initiatives were matched by public relations and information campaigns. Utilizing what has traditionally been activist counter-information tactics (Juris, Caruso, and Mosca Citation2008), the wind company made their own WordPress website, Parque Eólico Bíi Hioxo, to dispel point by point popular concerns with the wind park. This blog had a section titled ‘Myths and realities’ that asserts the wind park ‘is environmentally friendly’; ‘The land where wind farms are installed is still usable’ for ‘livestock, agriculture, fishing, etc.’; ‘It is not loud’; ‘It is safe’; and, finally, it ‘[I]nvolves Economic benefits for Communities’ (GNF Citation2013b). As emerged from the interviews, nearly all these points conflict with observations made by the people living in and around the Bíi Hioxo wind park (Navarro and Bessi Citation2015). The blog also documented and reposted all of the positive press and the contributions made to the surrounding communities (GNF Citation2013d). To lend credibility to these narratives, the public relations campaign was matched by raffling off household appliances, buying trophies for soccer tournaments, distributing Bíi Hioxo wind breakers to kids in the winter and supporting a breast cancer fundraiser, among other initiatives.

Another public relations technique appeared to live up to the spirit of FM 3-24 (Citation2014, 3–4), which states that ‘stories, sayings and even poetry can reveal cultural narratives of shared explanation’, that can be used to ‘[F]requently, advertise appeals to people by using these narratives, as do effective information operations’. Thus, the Winds of change photo exhibition by Jacciel Morales tried to blend Zapotec cultural symbols with wind turbines, attempting to send the message that the two could co-exist (GNF Citation2013c). You have cows under turbines, women in traditional dress playing with their children surrounded by wind turbines () as well as a farmer reflecting into the sunset – with wind turbines in the background. Though it was a notable attempt at public relations, some young students knew better. A member of Radio Totopo explained:

They set up a photo exhibition in the house of culture. In the schools that have received computers and paints to paint the school, they told the teachers that they need the kids to come to the exhibition. So, they dragged several kids to the exhibition. Among those kids was the daughter of Juanito, and this girl told the teacher that they did not want to go to the exhibition because they are fooling the kids. So the teacher said: ‘If you do not go, you are going to lose points for your grades’. And the girl said: ‘I don’t care. I am going to tell my mom’. So, Juanito’s wife, Maria, went and told the [other] parents that the kids were going to be taken out of school without the parents’ permission to go to the exhibition with the intention of fooling the kids to convince them that the wind turbines do not pollute and that people can live with them. So, by the time the girl had told their mom, two buses have already left the school paid by the [wind] company, and they took the kids without authorization. So, from this incident a group of women was formed, among them Juanito’s wife and they went to the House of Culture and they yelled at the principal: ‘Hey, you are fooling the kids! And that is in violation of children’s rights! And you are also going over the parents’ authority’. So, they yelled and the kids heard, and the principal called the state police.

Figure 4. Photo from the winds of change exhibition by Jacciel Morales. Source: GNF Citation2013c.

In addition to public relations campaigns, ‘soft’ counter-insurgency tactics included creating and widening social divisions within Zapotec religious groups – a tactic also documented around Zapatista territory in Chiapas (Gledhill Citation2002). The wind company, according to members in the resistance, through donations, bought off churches and people within religious congregations, spawning internal divisions. One way in which this occurred was that the wind company sponsored counter-Velas. Velas are large, often extravagant day- or even week-long cycles of festivals that take place in and around Juchitán. They are often centered on processions or a mass with food sharing, ritualized dancing and drinking (Rubin Citation1997). After the wind company had blocked communal roads and damaged and altered cultural sites, they ‘created an imitation of the three crosses and looked for a new Mayordomo who was financed by the wind energy companies to make their own Vela’, explained a Zapotec priest who described how they took the cross to another location in the north, bought the ‘best’ music groups from Oaxaca City as well as ‘gave away free beer, food, snacks and everything’.

The wind company with ‘its firm commitment to respect [ … ] the traditional ways of life’ (GNF Citation2013, 6, 224) created new religious divisions in the area, causing discord and discontent. By giving money to people in traditional Zapotec-Catholic religious groups, they found ways to create divisions and widen their support base. This demonstrates the truth, but also the deceptive nature of corporate social responsibility claims that respect culture but are simultaneously articulated as weapons in strategies of IMSO aimed at sowing divisions, disharmony and strife into the everyday Zapotec life.

Conclusion

The creation of the Bíi Hioxo wind park, and the managing and quelling of resistance against it, spawned social divisions and violent conflict, and intervened into the sensitive cultural fabric of Istmeño life. This contribution has examined the counter-resistance strategies undertaken to complete the Bíi Hioxo wind park in a joint effort by Gas Natural Fenosa, local elites and their national networks, from the perspective of counterinsurgency warfare. It has demonstrated how the tactics adopted to deactivate the social movement against the wind park approximate both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ counterinsurgency, reflecting at once the logics of violent repression, sowing social divisions and ‘winning hearts and minds’. These logics resonate with the political system of authoritarian corporatism, patronage and clientele networks characteristic of Southern Mexico. Furthermore, they reflect how since the 1960s, the Mexican armed forces, police and mercenary groups have progressively been immersed and trained in the art of low-intensity warfare. These strategies are designed to adapt and merge with local interests, which often seek to widen existing social and political divisions as a means to fragment, break and isolate resistance groups, often intentionally blurring the line between counterinsurgency and inter-communal conflict.

Examining conflicts from the perspective of counterinsurgency can prove analytically fruitful in unraveling specific warfare strategies, power relationships and the frequently overlooked weaponizing of social development programs. This also applies to natural resource conflict, the study of which can be enriched by examining how apparatuses of scientific violence and population management in their ‘unified action’ and ‘whole-of-government approach[es]’ operate to maintain government legitimacy, protect foreign direct investment and manage ‘social peace’ (FM3-24 Citation2014, 1–10, 1–12). It is from this perspective, regardless of their self-conception and reformist attitudes, that social movements are implicitly profiled as insurgent and proto-insurgent by both public and private security personnel trained, conditioned and organized by counterinsurgency doctrine. This means attentiveness to counterinsurgency can enrich analysis of how social movements are stifled, flourish or are co-opted/recuperated into the agendas of the state, transnational companies or regional actors. As a corollary, understanding counterinsurgency, its widespread application by governments and its fusing with domestic security imperatives can strengthen future social movements. Recognizing the strategies and tactics to break these movements may help to counteract them. Let this paper serve to encourage more research in this direction.

While the example of the Bíi Hioxo wind park demonstrates how counterinsurgency is applied – to support climate change mitigation and green economy projects – there is also another dimension to ‘green counterinsurgency’, namely how the military and other dominant actors use the green economy as a legitimizing device to push through wider projects of control. Arguably, the ‘green’ in the land grabs, the economy and climate change mitigation strategies is ultimately what the military calls a ‘force multiplier’, increasing the effectiveness of governance and its political and economic operations by enhancing their legitimacy. Counterinsurgency is about maintaining political stability and the legitimacy of government, including its choices to sell mining, timber and land concessions. The ‘green’, ‘sustainable’, ‘clean’ and ‘climate friendly’, among other popular phrases, are attempts at maintaining legitimacy in the face of widespread ecological crisis and climate change generated by industrial development – capitalist or otherwise (Dunlap and Fairhead Citation2014). Said differently, the ‘green’ in the notion of green grabs and green economy can be read as a larger pacification device to continue land acquisition and industrial development for continued market expansion. In the case of wind energy development, people living from the land, actively practicing and attempting to continue and uphold land-based cultural and subsistence practices, are all too aware of the negative impact of wind energy parks. However, people in North America, Europe and urban–suburban areas in Mexico, deeply inculcated in modern industrial lifestyles, are surprised when they hear about resistance against wind energy projects. The thought of people actively combating wind energy projects has a tendency to generate confusion and sometimes anger from people who are under the impression that wind energy is the solution to energy and climate crises. While counterinsurgency is used in the service of breaking resistance movements, the greening of industrial expansion acts to advance techniques of state, national and transnational corporate legitimacy that facilitate social pacification – fragmenting resistance and alienating potential national and international supporters unaware or indifferent (especially compared to fossil fuels) to the problems associated with wind energy development. This outcome of this legitimacy affirms business as usual in the face of anthropogenic food, energy and climate crises.

Acknowledgements

This article would not be possible with a great variety of help and support in Oaxaca from the APPJ, APIIDTT, the cabildo comunitario of Gui’Xhi’ Ro. Most notably, Mr. X, Flaco, Jack C. Anabel, Nadia, Anna and Paul R -- thank you for your time and commitment to working with and helping me. Likewise, comments from Judith Verweijen, Rodrigo Calvet, Ton Salman and the 3 anonymous reviewers proved valuable and are much appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alexander Dunlap

Alexander Dunlap is currently a doctoral candidate in the Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. His research focus has been on the social impact of wind energy projects in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Mexico. He has been living there for the last seven months, assessing the problems and social conflict generated by wind projects. Recent publications have been in the journals Anarchist Studies and Review of Social Economy, and a co-authored piece in Geopolitics, ‘The militarisation and marketisation of nature: an alternative lens to “climate-conflict”’.

Notes

1 The COCEI is an ex-social movement turned political party that has been actively collaborating and negotiating with wind energy companies in the region, but this political party is not without its internal tensions.

2 A scarf that is part of traditional dress in the Istmo.

3 A cloth pouch.

4 Direct translation: ‘traditions and customs’.

5 Central Valley, Mixteca, Cañada, Papaloapam, Sierra Norte, Sierra Sur and the Coast.

6 Coalición Obrera, Campesina, Estudiantil del Istmo.

7 Programa de Certificación de Derechos Ejidales y Titulación de Solares.

8 See Dunlap (Citation2014) for a brief etymology of ‘peace’.

9 Comisión Nacional Forestal.

10 Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries, and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.

11 Even though this is well known in the Istmo, names will not be used here.

12 Their work also included organizing Movimiento de Unificación de las luchas Triquis (MULT) paramilitary groups in the Sierra Sur and Mixteca, which intensified divisions and killing among Triqui communities (see Norget Citation2005; Stephen Citation2013).

13 Zapotec spellings tend to vary between people and some of these spellings were not confirmed.

14 There is dispute over the exact meaning of ‘Chigueze’, deriving from Zapotec words such as thorn, priest and sweet potato.

15 Commonly known as Los Contras, they are regarded as police and paid by the (COCEI–PRD) Juchitán administration to counter the struggle for Indigenous autonomy against wind parks in Álvaro Obregón.

16 Percepción de Parquet Eólico Juchitán, Oaxaca.

References

- Altamirano-Jiménez, I. 2014. Indigenous encounters with neoliberalism: Place, women, and environment in Canada and Mexico. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Arronte, E.L., G.E. Castro-Soto, and T.P. Lewis. 2000. Always near, always far: The armed forces in Mexico. San Francisco: Global Exchange.

- Assies, W. 2008. Land tenure and tenure regimes in Mexico: An overview. Journal of Agrarian Change 8: 33–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0366.2007.00162.x

- Bartra, A. 2007. Los municipios incómodos. In La remuniciipalización de Chiapas: lo politico y la politica en tiempo de contrainsurgencia, ed. XL Solano, and ABCy Mayor, 329–43. Mexico City: Camara de Diputados LVII Legislatura.

- Bebbington, A., D.H. Bebbington, J. Bury, Jeannet Lingan, Juan Pablo Muñoz, and Martin Scurrah. 2008. Mining and social movements: Struggles over livelihood and rural territorial development in the Andes. World Development 36: 2888–905. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.11.016

- Binford, L. 1985. Political conflict and land tenure in the Mexican isthmus of Tehuantepec. Journal of Latin American Studies 17: 179–200. doi: 10.1017/S0022216X0000924X

- Borras, S., C. Kay, S. Gómez, and John Wilkinson. 2012. Land grabbing and global capitalist accumulation: Key features in Latin America. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D'études du Développement 33: 402–16. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2012.745394

- Boyce, G., and C. Cash. 2013. Geography, counterinsurgency, and the “G-bomb”: The case of México Indígena. In Life during wartime: Resisting counterinsurgency, ed. K Williams, W. Munger, and L Messersmith-Glavin, 245–58. Edinburgh: AK Press.

- Bryan, J., and D. Wood. 2015. Weaponizing maps: Indigenous peoples and counterinsurgency in the Americas. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Büscher, B., and M. Ramutsindela. 2016. Green violence: Rhino poaching and the War to save Southern Africa’s Peace parks. African Affairs 115: 1–22.

- Caselli, F., and T. Cunningham. 2009. Leader behaviour and the natural resource curse. Oxford Economic Papers 61: 628–50. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpp023

- CDM. 2012. Clean Development Mechanism Project Design Document Form (CDM-PDD): Fuerza y Energia Bii Hioxo Wind Farm. Juchitan de Zaragoza: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

- CODIGODH. 2014. Rostros de la Impunidad en Oaxaca: Prespectivas desde la Defensa Integral de los Derechos Humanos. Oaxaca: El Comité de Defensa Integral de Derechos Humanos Gobixha (CODIGO DH).

- CONEVAL. (2015) Informe de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social en México 2014. http://www.coneval.org.mx/Informes/Evaluacion/IEPDS_2014/IEPDS_2014.pdf.

- Copulsky, J.R. 2011. Brand resilience. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Downey, L., E. Bonds, and K. Clark. 2010. Natural resource extraction, armed violence, and environmental degradation. Organization Environment 23: 453–74.

- Duffy, R. 2016. War, by conservation. Geoforum 69: 238–48. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.09.014

- Dunlap, A. 2014. Permanent war: Grids, boomerangs, and counterinsurgency. Anarchist Studies 22: 55–79.

- Dunlap, A., and J. Fairhead. 2014. The militarisation and marketisation of nature: An alternative lens to ‘climate-conflict’. Geopolitics 19: 937–61. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2014.964864

- Earthfirst!. 2013. Mexico: 22 injured in Oaxaca wind farm protest. https://earthfirstnews.wordpress.com/2013/04/02/mexico-22-injured-in-oaxaca-wind-farm-protest/.

- Elliott, D., M. Schwartz, G. Scott, et al. 2003. Wind energy resource atlas of Oaxaca. Colorado: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

- Fairhead, J., M. Leach, and I. Scoones. 2012. Green grabbing: A new appropriation of nature? The Journal of Peasant Studies 39: 237–61. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.671770

- Finn, J.C., T. Barnes, J. Bryan, et al. 2014. Book review symposium: Geopiracy: Oaxaca, militant empiricism, and geographical thought. Human Geography 7: 60–101.

- FM3-24. 2014. Insurgencies and countering insurgencies. http://fas.org/irp/doddir/army/fm3-24.pdf.

- Gledhill, J. 2002. Una nueva orientación para el laberinto: la transformación del Estado mexicano y el verdadero Chiapas. Relaciones 90: 203–57.

- GNF-(GasNaturalFenosa). 2013 June. Percepción de Parque Eólico Juchitán, Oaxaca. Survey. Mexico, 1–36.

- GNF-(GasNaturalFenosa). 2013a. ¿Quién es Bií Hioxo? https://biihioxo.wordpress.com/quien-es-bii-hioxo/.

- GNF-(GasNaturalFenosa). 2013b. Mitos y realidades. https://biihioxo.wordpress.com/ecologia-y-cultura/.

- GNF-(GasNaturalFenosa). 2013c. Se inauguró con éxito la muestra fotográfica “Vientos de Cambio” del artista local Jacciel Morales. https://biihioxo.wordpress.com/2013/11/14/se-inauguro-con-exito-la-muestra-fotografica-vientos-de-cambio-del-artista-local-jacciel-morales/.

- GNF-(GasNaturalFenosa). 2013d. Archivo de la etiqueta: Juchitán. https://biihioxo.wordpress.com/tag/juchitan/.

- GNF-(GasNaturalFenosa). 2014. 2014 corporate social responsibility report. http://www.gasnaturalfenosa.com/servlet/ficheros/1297147982420/IRC_ing_accesible_op,0.pdf.

- Gobierno de Oaxaca. 2011. Planes Regionales de Desarrollo de Oaxaca 2011–2016: Istmo, p. 59 footnote 38. http://www.transparenciapresupuestaria.oaxaca.gob.mx/pdf/03/Istmo.pdf.

- IFC. 2014. Investments for a windy Harvest: IFC support of the Mexican wind sector drives results. http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/60c21580462e9c16983db99916182e35/IFC_CTF_Mexico.pdf?MOD = AJPERES.

- Javers, E. 2011. Oil executive: Military-style ‘psy ops’ experience applied. http://www.cnbc.com/id/45208498.

- Juris, J.S., G. Caruso, and L. Mosca. 2008. Freeing software and opening spaces: Social forums and the cultural politics of technology. Societies Without Borders 3: 96–117.

- Kilcullen, D. 2006. Twenty-eight articles: Fundmentals of company-level counterinsurgency. IO Sphere 2: 29–35.

- Lunstrum, E. 2014. Green militarization: Anti-poaching efforts and the spatial contours of Kruger national park. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104: 816–32. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2014.912545

- Mackinlay, H., and G. Otero. 2004. State corporatism and peasant organizations: Towards new institutional arrangements. In Mexico in transition, ed. G Otero, 72–88. London: Zed Books.

- McAfee, K., and E.N. Shapiro. 2010. Payments for ecosystem services in Mexico: Nature, neoliberalism, social movements, and the state. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100: 579–99. doi: 10.1080/00045601003794833

- MG. 2007. Mexico’s constitution of 1917 with amendments through 2007. https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Mexico_2007.pdf.

- Navarro, S., and R. Bessi. 2015. The dark side of clean energy in Mexico. https://darktracesofcleanene.atavist.com/dark-traces-of-clean-energy-f1xd6.

- Norget, K. 2005. Caught in the crossfire: Militarization, paramilitarization, and state violence in Oaxaca, Mexico. In When states kill: Latin America, the U.S., and technologies of terror, ed. C Menjívar, and N Rodríguez, 115–42. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Oceransky, S. 2011. Fighting the enclosure of wind: Indigenous resistance to the privatization of the wind resource in southern Mexico. In Sparking a worldwide energy revolution: Social struggles in the transition to a post-petrol world, ed. K Abramsky, 505–22. Oakland: AK Press.

- Osborne, T. 2013. Fixing carbon, losing ground: Payments For environmental services and land (in)security in Mexico. Human Geography 6: 119–33.

- Owens, P. 2015. Economy of force: Counterinsurgency and the historical rise of the social. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Paley, D. 2014. Drug war capitalism. Oakland: AK Press.

- Payan, T., and G. Correa-Cabrera. 2014. Issue brief 10.29.14: Land ownership and use under Mexico’s energy reform. https://bakerinstitute.org/files/8400/.

- PBI. 2013. PBI Mexico: Worrying wave of violence against human rights defenders in Oaxaca. http://www.pbi-mexico.org/field-projects/pbi-mexico/news/news/?no_cache=1&L=0&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=3951&tx_ttnews[backPid]=109&cHash=6ec10488171a5f53900abf4b1de5d705.

- Peluso, N., and C. Lund. 2011. New frontiers of land control: Introduction. The Journal of Peasant Studies 38: 667–81. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2011.607692

- Peluso, N.L., and P. Vandergeest. 2011. Political ecologies of war and forests: Counterinsurgencies and the making of national natures. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101: 587–608. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2011.560064

- Rivas SC. 2015 Jan. Consulta Definira Futuro De Inversiones Eolicas: Ocaso o resplandor. http://www.noticiasnet.mx/portal/sites/default/files/flipping_book/oax/2015/01/23/secc_a/files/assets/basic-html/page20.html.

- Rocheleau, D.E. 2015. Networked, rooted and territorial: Green grabbing and resistance in Chiapas. The Journal of Peasant Studies 42: 695–723. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2014.993622

- Rosenau, W., P. Chalk, R. McPherson, et al. 2009. Corporations and counterinsurgency. Santa Monica, CA: RAND National Security Research Division.

- Rubin, J.W. 1997. Decentering the regime: Ethnicity, radicalism, and democracy in Juchitán, Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Salman, T., and W. Assies. 2007. Anthropology and the study of social movements. In Handbook of social movements across disciplines, ed. B. Klandermans, and C. Roggeband, 205–65. New York: Springer.

- Shapiro-Garza, E. 2013. Contesting market-based conservation: Payments for ecosystem services as a surface of engagement for rural social movements in Mexico. Human Geography 6: 119–133.

- Stephen, L. 2002. Zapata lives! Histories and cultural politics in southern Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Stephen, L. 2013. We are the face of Oaxaca: Testimony and social movements. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Sullivan, S. 2009. Green capitalism, and the cultural poverty of constructing nature as service provider. Radical Anthropology 3: 18–27.

- Sullivan, S. 2013. Banking nature? The spectacular financialisation of environmental conservation. Antipode 45: 198–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.00989.x

- UNGC. (2014) What is UN global compact. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc.

- Verweijen, J., and E. Marijnen. 2016. The counterinsurgency/conservation nexus: Guerrilla livelihoods and the dynamics of conflict and violence in the Virunga national park, democratic republic of the Congo. The Journal of Peasant Studies 43: 1–21. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1101069

- Vidal, J. 2008. The great green land grab. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2008/feb/13/conservation.

- Williams, K. 2007 [2004]. Our enemies in blue: Police and power in America. Cambridge: South End Press.

- Williams, K., W. Munger, and L. Messersmith-Glavin. 2013. Life during wartime: Resisting counterinsurgency. Edinburgh: AK Press.

- Wilson, J. 2013. The urbanization of the countryside: Depoliticization and the production of space in Chiapas. Latin American Perspectives 189, no. 2: 218–36. doi: 10.1177/0094582X12470378