ABSTRACT

Economistic approaches to the study of peasant livelihoods have considerable academic and policy influence, yet, we argue, perpetuate a partial misunderstanding – often reducing peasant livelihood to the management of capital assets by rational actors. In this paper, we propose to revitalize the original heterodox spirit of the sustainable livelihoods framework by drawing on Stephen Gudeman’s work on the dialectic between use values and mutuality on the one hand, and exchange values and the market on the other. We use this approach to examine how historically divergent mutuality-market dialectics in different Amazonian regions have shaped greater prominence of either extractivism or agriculture in current livelihoods. We conclude that an approach centered on the mutuality-market dialectic is of considerable utility in revealing the role of economic histories in shaping differential peasant livelihoods in tropical forests. More generally, it has considerable potential to contribute to a much-needed re-pluralization of approaches to livelihood in academia and policy.

1. Introduction

The men here, they just do a little fishing, their boss pays them hardly anything, they don’t think of the future: working with nature doesn’t get you anywhere. They plant a little manioc, but hardly enough to last a few months [of the year]. They also work with lianas and making barbecue sticks, but after five days’ work this is barely enough [money] to buy even a few supplies … . The people here live from nature … nothing of nature gives any income, nothing has life from the nature. Kill, cut wood and it dies, cut a liana and it dies … . But the land gives life, everything that we plant gives life … A vida é futuro, a morte não tem (Life [agriculture] is future, but death [extractivism] has none.). If I had a little capital, I’d plant 3000 cacao trees, 3000 papaya plants … .

Henrique Mendoza Fortado

This paper focuses on ‘traditional populations’ of Brazilian Amazonia, whose livelihoods fall into the broad analytical category of tropical forest ‘agro-extractivists’ (Adams et al. Citation2009a). However, Amazonian livelihoods are heterogeneous, and place-based comparisons reveal livelihood diversity characterized by different combinations of agriculturalist and extractivist activities. These spatial differences are shaped by distinct historical processes, adding up to significant inter- and intra-regional heterogeneity which is important to understand from an environmental and social policy perspective. Herein, we distinguish three sub-categories of livelihood: agricultural, extractivist and agro-extractivist. Agricultural livelihoods are characterized by eight months or more a year of subsistence farming (small-scale diversified crop production mainly for household consumption, drawing on family and kin for labor, with some sale of surplus each year), whereas extractivist livelihoods are those where eight months or more a year are spent gathering and working with forest products, hunting and fishing (for sale in addition to subsistence) and/or small-scale timber harvesting. Agro-extractivist livelihoods are those where agricultural and extractive activities are more closely balanced. ‘Agricultural’ and ‘extractivist’ should therefore be conceived of as polarities on a continuum of time devoted to each activity, while the combination of the two is characterized as ‘agro-extractivist’ livelihoods.

Distinguishing among these broad sub-categories of livelihood, their political economy and history of underlying modes of production and extraction is important in understanding the following questions among the traditional populations of different regions of Brazilian Amazonia: (1) why people make particular natural resource and land management decisions; (2) the roles of economic history and environmental characteristics in the differentiation of livelihood trajectories; (3) the dynamics of indenture versus freedom in community formation. We return to these three questions in our three sets of conclusions in the final section of the paper. To be clear, our use of the term ‘extractivism’ should be distinguished analytically from mineral and hydrocarbon extraction (Bebbington Citation2011), and also industrial agricultural production of soybeans, sugarcane and oil palm (Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho Citation2016; Fernandes, Welch, and Gonçalves Citation2010), which can also be considered ‘extractivist’, in the sense that the productive process extracts ecological, economic and/or social value (Alonso-Fradejas Citation2015).

In this paper, we argue that the dominance of economistic approaches to livelihoods can lead to a certain blindness with regard to their relational and historical shaping. The theoretical lenses employed by research communities to understand peasant livelihoods in developing countries shape the policy world –in terms of both policy agendas and the ways in which policymakers conceive of the subjects of their policymaking. The success or failure of environmental policies in tropical forests then depends on how they conceptualize the realities of target groups, which depends in turn on the lenses employed to understand livelihoods. Policies can produce new or reshape existing livelihood differentiation, through the uneven distribution of benefits and burdens depending on the ability of different socio-economic groups to take advantage of new opportunities (Scoones et al. Citation2012; Li Citation2014; Campbell Citation2015). More subtly, the governmentalizing (i.e. the ‘conduct of conduct’) effects of environmental discourses on policies aimed at forest citizens (Agrawal Citation2005) can be problematic when not attuned to local realities. Examples include the effects of anti-swidden narratives that have characterized the tropics from the colonial period to present (e.g. Dressler Citation2014), the effects of conservationist narratives wherein science is ‘fact’ and local knowledge is ‘opinion’ (e.g. Cepek Citation2011), or the resurrection of the old trope of the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor in environmental form in their categorization as ‘eco-threats’ or ‘eco-guardians’ in relation to national parks (Ojeda Citation2012). Therefore, both reflexive awareness and critical appraisal of prominent lenses is crucial (Moon and Blackman Citation2014).

Over the last three decades, livelihood approaches have become popular with policymakers. Underneath and behind the thinking that went into the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) lies a critical and heterodox set of influences including political ecology, actor-oriented development sociology and Marxist approaches (Scoones Citation2009, 174; Scoones Citation2015), embracing thinkers as diverse as Tony Bebbington, Henry Bernstein, Debbie Bryceson, Robert Chambers, Frank Ellis, Ian Scoones and Norman Long (Batterbury Citation2016). The majority of studies that claim to use the SLF, however, do so in a narrowly economistic and instrumental fashion, which goes against the pluralist spirit of its original conceptualization. Livelihood research and policy interventions are dominated by micro-economic and demographic approaches, based on underlying assumptions that (1) individuals and households are rational actors who maximize their utility by (2) managing a set of five ‘capital assets’, (social, human, physical, natural and financial). Various authors use such approaches in studies focused on Amazonia (e.g. Duchelle et al. Citation2014; Morsello et al. Citation2014; Yoshito Takasaki and Oliver Citation2001; Walker, Moran, and Anselin Citation2000; VanWey, D’Antona, and Brondízio Citation2007; Caviglia-Harris and Sills Citation2005; Coomes, Grimard, and Burt Citation2000; Perz Citation2005; Brondízio et al. Citation2013). Both of these assumptions are open to question, however, especially when reified from the much broader and richer context of the original SLF (i.e. Scoones Citation2015, 36).

Firstly, the idea of people as Homo economicus – that is, of universal economic rationality as a fundamental human characteristic – can be traced through thinkers such as Friedman, Hayek, Ricardo, Mill and Locke back to classical liberalism. A longstanding debate turns on the degree to which peasant (and, indeed, other) societies can or should be conceived of either in such ‘formal’ terms – that is, of instrumentally rational, self-maximizing atomized individual agents, on the one hand, as opposed to ‘moral’ or ‘substantive’ terms, as actors whose decisions are shaped more by kinship, religion and social institutions (Scott Citation1977; Polanyi Citation1957; Weber Citation1978; Gudeman Citation2008). A variety of studies have shown that the logic of production in peasant societies is in maintaining the household, subsistence and cultural institutions, rather than maximizing productivity (Curry et al. Citation2015; Laney and Turner Citation2015; Fraser, Frausin, and Jarvis Citation2015). Our criticism of economistic livelihoods approaches here is that they overly emphasize the formal dimension of (utilitarian) exchange-values without properly accounting for the importance of the substantive dimension of (deontological, moral) use-values (Gudeman Citation2001, 17).

Second, whilst the SLF as originally conceived incorporated institutional contexts and processes, and so relations as well as capitals (Carney Citation1998), the idea of assets as capital is often the only aspect of the SLF given serious consideration in economistic studies of livelihood. As Ian Scoones, one of the scholars associated with the original SLF, notes, the focus on ‘capitals’ and the ‘asset pentagon’ ‘kept the discussion firmly in the territory of economic analysis’ which was ‘in some respects … an unfortunate diversion’ (Scoones Citation2009, 176–78). The term ‘capital’, as used by economists, derives its meaning from institutional contexts of the private ownership of productive assets (Arce Citation2003, drawing on Robinson Citation1953). It has long been recognized that peasants tend to be less market integrated than other types of actors, however (Chayanov Citation1986).

In peasant societies, the pursuit of a livelihood entails complex mixtures of collective (or commons) and private (or capital) property ownership (Arce Citation2003, 203). Economistic approaches to livelihoods therefore arguably conflate assets with capital, often reducing livelihoods to merely the rational allocation of resources for economic ends (Carr Citation2015; Arce Citation2003). Various other authors have made the point that the dominance of the economistic framing has led to a situation where there is frequently no explicit theorization of the epistemological and ontological underpinnings of livelihoods approaches. This is related to a lack of attention to the realities of research subjects – neglecting and obscuring socio-cultural and historical dimensions of land use and livelihoods (e.g. De Haan and Zoomers Citation2003; Kaag Citation2004; Small Citation2007; Prowse Citation2010; Jakimow Citation2012; Carr Citation2013; Citation2015; Oestreicher et al. Citation2014).

In this paper, we argue that an approach to livelihoods based on the dialectic between mutuality and market spheres, as elaborated by Stephen Gudeman (Citation2001, Citation2008), is better suited to capture the historical dynamics of and tensions between relations of exchange and community in the emergence of spatially differentiated tropical forest peasant livelihoods. We illustrate our argument by using Gudeman’s mutuality-market dialectic to explain diverging patterns of agriculture and extractivism in livelihoods in two different regions of the Brazilian Amazon. We demonstrate that spatial and temporal differences in mutuality-market dialectics have shaped the extent to which long-term agricultural communities could form in different regions of Brazilian Amazonia. By ‘long-term’ we mean communities that have been in existence for several generations.

The paper is structured into nine sections. The following section 2 presents our theoretical framing based on Gudeman’s mutuality-market dialectic, while section 3 locates this framing in Amazonian economic history, and section 4 describes our methodology. Section 5 explores local understandings of livelihood differentiation, while sections 6 and 7 present two contrastive case studies of peasant livelihoods in two different regional environments of Brazilian Amazonia, the lower Negro and middle Madeira rivers. Studies of resource use by tropical peasantries are typically restricted to single communities or localities (e.g. Brondizio et al. Citation1994; Caviglia-Harris and Sills Citation2005; Coomes and Burt Citation2001). Few studies have actually compared populations living in different kinds of tropical environments, using qualitative and quantitative methods, to explore whether or why there are links between specific socio-historic populations and current livelihoods. We argue that peasant economy and society are constituted through a historical dialectic between community and market, and the ways in which this plays out vis-à-vis the socio-ecological characteristics of different regions and their particular extractive regimes. Section 8 tests this assertion using quantitative survey data from sub-tributaries of the River Negro and River Madeira. Section 9 presents our conclusions.

2. Mutuality-market dialectics and the Amazonian peasantry

For Gudeman, economies are comprised through a dialectic between the realm of mutuality, the moral subsistence base of community, and the amoral, impersonal market realm, with the latter developing through competitive trade (Gudeman Citation2008). From this viewpoint, economy consists in the contradiction or tension between people producing for themselves and trading with others. People in part live by way of the anonymous, competitive trade of goods, services, labor and money that are separated or alienated from enduring relationships – the market realm. But they also live through the realm of community or mutuality, wherein ‘things and services are secured and allocated, by means of continuing ties, such as taxation and redistribution; through cooperating kinship groups, households, and other groupings; by bridewealth, indenture, and reciprocity, and by self-sufficient activities, such as agriculture, gardening … ’ (Gudeman Citation2008, 5).

This dialectic was first expressed through Aristotle’s notions of use-value versus exchange-value: the former referring to trade which sustains ‘the community’, the latter referring to market trade aimed at increasing monetary capital. Aristotle’s distinction was developed by Smith, Ricardo and Marx (Bloch and Parry Citation1989). To take up a dialectical approach means focusing on how people experience life or being in terms of relations and processes (rather than as atomized individuals) and the ways in which these are contingent on space, time and scale (Harvey Citation1997, 49–57). Dialectics is close to other traditions, in particular phenomenology, which anthropologists argue are better suited to understanding peasant livelihoods from the perspectives of lived experience or ‘lifeworlds’ of those who practice them (Ingold Citation2000; Jackson Citation2013; Harris Citation2005; Willerslev Citation2004; Roth Citation2009; Fraser, Leach, and Fairhead Citation2014).

The Amazonian peasantry is made up of the descendants of mixed Indigenous, European and African backgrounds. Migrants, primarily of European descent, came to the region during the rubber boom (1860–1920); the traffic of Africans slaves to the region intensified during the second half of the nineteenth century, being most pronounced in Eastern Amazonia with long-lasting impacts on social and cultural life in the region. This diverse and heterogeneous group is collectively known as caboclos; the term is, however, ambiguous and sometimes pejorative. Caboclos that live along rivers and other watercourses are also referred to as riberinhos (river dwellers) – a place-based identification (Adams et al. Citation2009a; Nugent Citation2002; Lima Citation1992; Cunha and de Almeida Citation2000; Barretto-Filho Citation2009).

Amazonian peasant livelihoods historically and today consist of the practice of semi-autonomous forest and river extractivism and agriculture; their carbohydrate staple is bitter manioc (Manihot esculenta), which is the subsistence base of community and mutuality (re)productionFootnote2 (Adams et al. Citation2009b). Hence, the Amazonian peasantry is unique to the region and different from other Latin American peasantries that worked on plantations or as share-croppers and were much more integrated into national economies (Nugent Citation1993; Nugent and Harris Citation2004; Adams et al. Citation2009a; Harris Citation1998, Citation2000).

Like other Latin American peasantries, contemporary Amazonian ‘traditional populations’ are a heterogeneous mixture of ‘new peoples’ (Schwartz and Salomon Citation1999). These are traditional peoples strongly shaped by modernity itself (paradoxically, given the normal putative opposition between ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’) – through conquest of America and the control of the Atlantic after 1492 and the decimation of native populations (Escobar Citation2007; Quijano Citation2007). The economic expression of modernity and early merchant capitalism in Amazonian was the aviamento system (described in more detail in the following section), which peaked during the rubber boom and was based on a regionally unique model of debt-peonage rather than waged labor as in other regions of Latin America (Hecht Citation2013, Chapter 14).

Western framings of Amazonian culture as its indigenous ‘other’, as explored by the ‘tropicality’ literature (e.g. Arnold Citation1996; Hecht Citation2013), has led to these mixed peasantries emerging in the wake of colonialism – which do not fit this category – to largely be deemed uninteresting by anthropologists (cf. Nygren Citation1999), leading to a relative absence of long-term ethnographic work. These factors add up to perpetuate an ‘invisibility’ in policy and research (Nugent Citation1993, Citation2002; Harris Citation1998). This could lead to the idea that Amazonian peasants are more or less ‘modern’ people living traditional livelihoods that can be understood with livelihood models that emphasize economic rationality (since to be ‘modern’ is to be ‘rational’) (Quijano Citation2007).

This obscures an understanding of the plurality of agro-ecological trajectories and economic histories of domination and emancipation, and degrees of community and kin formation that underpin current livelihood strategies. This invisibility risks perpetuating existing misrecognition of these subalternFootnote3 (Spivak Citation1988) social groups, and is unjust in that it fails to recognize the differentiation of Amazonian peasantry (Young Citation1990). Invisibility is certainly not the only, nor the most important problem faced by the Amazonian peasantry. Material issues, such as poverty, food insecurity, and lack of health and education services, are more urgent, but in order to tackle these issues the dynamics of how residents make a living and livelihood differentiation need to be understood, and hence invisibility is a central consideration here. The notion of ‘differentiated citizenship’ (Holston Citation2008) is growing in popularity amongst Amazonian scholars, helping to render regional difference visible (Hecht Citation2011; Mathews and Schmink Citation2015; Campbell Citation2015). The key point we make here is that Amazonian peasants are differentiated by their livelihoods and associated agro-ecological knowledge which are products of diverse economic histories or trajectories, relational phenomena which are not captured by economistic – that is, individualistic and atomistic – approaches to livelihood.

3. Amazonian peasant livelihoods: agriculture and extractivism, mutuality and market

The rubber boom, which stimulated a huge economic migration from the drought-stricken Northeast of Brazil to rivers throughout Amazonia (Weinstein Citation1983), along with aviamento labor relations can be said to have established the economic basis of the modern Amazonian peasantryFootnote4 (Lima Citation1992, 94; Santos Citation1980, 100; Weinstein Citation1983, 90). This section explains how diverging mutuality-market dialectics emerged in different regions. In some regions, rubber-era workers had the freedom to form communities, and therefore the mutuality that underwrites them, and these regions now tend to be characterized by longer term, larger communities, related as kin, which facilitates labor for settled agriculture, the practice of which is today widespread. In other regions, conversely, where rubber boom relations were more coercive and bosses’ (patrões) restrictions inhibited settlement formation, kin-based agricultural communities and so relations of mutuality have only formed in the last generation or so, after this system broke down, and people today are likely to practice more extractivism.

The market relations which have shaped the above-mentioned situations (whether allowing relative freedom or degrees of coercion) were historically expressed as aviamento, a system whereby patrões (bosses) exchange manufactured goods for extractive resourcesFootnote5 with fregueses (workers). Amazonian peasantries came into being in the context of debt relationships (albeit varying in intensity) of the aviamento system. Aviamento provided patrões the twin function of labor control and surplus extraction via a ‘debt’ enforced through violence and coercion. The aviamento system has become much less pervasive in the contemporary period, but still exists alongside the modern capitalist labor relations in Amazonia, especially in very remote regions (Mathews and Schmink Citation2015).

Locations where farming communities were able to form tended to be in less remote regions where there were a variety of actors offering relations of aviamento (that is, in situations where there was not a monopoly); in areas where extractive resources (e.g. rubber and Brazil nut stands) are concentrated, such as in nutrient-rich white-water environments. This allowed for a more settled and freer form of agro-extractivism to emerge, and people could engage in aviamento on more favorable terms (Dean Citation1982, 41; Weinstein Citation1983, 20; de Almeida Citation1992).

Conversely, in regions where natural resources are more dispersed (such as nutrient-poor black-water environments), extractivism was necessarily more peripatetic, and this made it easier for aviamento monopolies to form wherein patrões were able to prevent manioc farming and subject workers to more exploitative forms of aviamento, all of which inhibited the formation of long-term communities, and the associated benefits of kinship-based labor, subsistence food production, and mutuality.

The sphere of mutuality for Amazonian peasants centers on the community. Amazonian communities are ideally based on kinship, expressed as ‘tudo parente’ (all kin), in a popular idiom. They are structured as ‘clusters’, which are ‘dense networks of multi-family houses, organised around a parental couple’ (Lima Citation1992; Harris Citation2000, 84), which are the ‘matrix of social organisation and reproduction … the primary units in which economic and social life are acted out’ (Harris Citation2000, 87). The mutuality, to use Gudeman’s term, which binds clusters has been expressed for contemporary Amazonian peasants in terms of the ‘economy of affection’ in which family ties and exchange/remittances underpin contemporary rural-urban networks/linkages (WinklerPrins and de Souza Citation2005).

An important function of kinship in rural Amazonia is to mediate access to resources, principally land (Harris Citation2000), and to provide labor for agriculture (Lima Citation2004). Clusters are often tied to one another through ‘re-linking marriages’, creating a dense network of consanguineous and affinal ties. Communities are usually formed from two or more intermarried complex clusters. Long-term multi-generational settlements are formed from a series of interlinked complex clusters, whereas in regions where most families have recently migrated from other places, families may be in discrete individual households not linked by kinship.

Mutuality was historically manifest through micro-economies of reciprocity and redistribution known as ‘Putáua’, a Nheengatu term (the lingua geral of the colonial period, derived from Tupi); literally ‘a gift’, carrying with it the obligation of retribution, whereby a family donates some food (meat, fish, manioc flour, fruits or industrial products) to another family who will return the gift, either immediately or later, with another portion of food or similar. Writ large, it is a network of exchange of gifts which greatly contributes to food provisioning in the community, avoiding over-accumulation by some houses and shortages in others (Vaz Citation2010, 31). Farming was organized through the puxirum (agricultural work group), which is, according to Vaz, a big putáua of work, food and comradeship. In the context of the shifting cultivation of manioc, each year, people work in one another’s fields and fallows, exchanging seeds, fruits, manioc flour (farinha), domestic animals, baskets, etc. A key point for our purposes here is that both putáua and puxirum, as institutions of mutuality, require a community featuring one or more clusters, to facilitate the constant flow of gifts and provide labor for farming. Since the 1970s, the functioning of these informal institutions has declined, with the spread of cash economies and more individualistic rationality taking hold (Vaz Citation2010, 371), which can be seen as the market sphere and its influence being more completely realized.

For Amazonian peasants, mutuality and the market have existed in dialectical tension right from the very beginning. In common with other peasants at the frontiers of capitalism, Amazonian peasantries ‘originated in the expansion of merchant capitalism and are characterized by two spheres of production, one for direct use and the other for exchange’ (Lima Citation1992, 124). Our point is that the emergence of mutuality was enabled or constrained by different relations of aviamento (that is, the market) in different regions. Aviamento was socially underwritten through fictive kinship: the institution of patrons being co-parents (compadrio) of peasant children gave exploitation a veneer of social acceptability through tropes of kinship and patriarchal authority (Brass Citation1986). Conversely, Wagley (Citation2014) argued that Amazonian peasants use compadrio with full conscientiousness as a way to access resources in the absence of the state, a kind of ‘weapons of the weak’ as James Scott puts it, and this continues today.

The degrees of agency as opposed to domination associated with the debt-bondage relationship of aviamento varied greatly. During the boom period, a wide variety of labor regimes existed (Weinstein Citation1983, 20). There were wide-ranging differences across space and time in the levels of coercion and use of physical violence.Footnote6 Aviamento varied enormously in the way its power relationships were expressed, ranging from the landless ‘peon’ in quasi-slavery to tappers as small-scale producers who legally owned four or five trails, producing enough food to subsist, and with more equal relationships with their patron (Dean Citation1982, 41; Weinstein Citation1983, 20; de Almeida Citation1992). After the end of the rubber boom, the Amazonian economy continued to focus on extractivism and the aviamento regime persisted, although its coercive powers gradually diminished over time, owing to increases in state intervention, internal market competition and a reduction in the power of patrões. These factors proved decisive in the emancipation of Amazonian peasantries (Lima Citation1992, 92). Freedom, for Amazonian peasantries, is being able to live and work in the woods and near the river, in the countryside, farming, hunting and fishing with relatives without interference or exploitation by outsiders (Vaz Citation2010, 444).

While the inalienable rights to communal territory of Quilombola (Afro-descendent) and Indigenous peoples were formally recognized in the 1998 Constitution (Articles 68 and Article 231, respectively), ‘traditional peoples’, known regionally as caboclos and riberinhos and referred to here as the Amazonian peasantry, do not have constitutional land rights on the basis of ‘ethnic’ identity as these other groups do. Rather, they have rights based on their livelihood practices as tropical forest agro-extractivists, and to reside in territorial units such as the National Forest (FLONA), Extractive Reserve (RESEX), Sustainable Development Reserve (RDS) and a variety of INCRA Forest Settlement Projects, under Articles 17, 18 and 20 of the National Conservation Units Law, 2000, and Article 189 of the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, respectively (Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservação â SNUC, 2000; Almeida Citation2004).

Our argument also has an environmental dimension. Different kinds of Amazonian environments present different opportunities and constraints to agricultural and extractivist livelihoods, both today and in the past. White-water (eutrophic) and black-water (oligotrophic) Amazonian watersheds differ in their natural resources, including useful plant species, terrestrial and aquatic fauna, and cultivable floodplain soils. White-water rivers, such as the River Madeira (herein Madeira) are nutrient-rich because they are loaded with sediment originating in the Andes, and their floodplains are the most eutrophic environments in Amazonia (Junk and Furch Citation1985). This makes them more amenable to human habitation because there are fertile floodplains that can sustain seasonal intensive cultivation of annual crops and cattle grazing, and highly productive fisheries (Denevan Citation1996). This means that patches of fertile Anthropogenic Dark Earths (ADE) (Glaser and Birk Citation2012) tend to be larger and more abundant in white-water regions when compared to less fertile regions (cf. Petersen, Neves, and Heckenberger Citation2001). Black-water rivers, draining geologically old regions of the Amazon basin, do not carry significant particle loads and are characterized by very low nutrient concentrations (Quesada et al. Citation2011, 1417; Jordan Citation1985). They harbor five to 15 times lower fish densities than white-water regions, and their floodplains are not cultivable (Sioli Citation1984; Moran Citation1993; Ohly and Junk Citation1999; Oliver Citation2001).

Our interest in comparing livelihoods in different Amazonian environments was sparked by the viewpoint expressed by some of our interlocutors, that Amazonian peasants practicing agriculture on the black-water lower Negro River (herein Negro), where extractivism has been the principal mode of livelihood since the colonial era, tended to be migrants from white-water regions, where agricultural livelihoods are more likely to predominate (see section 5). Those who had grown up on the Negro, conversely, tended to practice more extractivist livelihoods (section 6). In white-water regions, by contrast, the practice of agriculture forms a much more important component of livelihoods (section 7). This divergence in current livelihood orientations, is, we argue, the outcome of divergent agro-extractivist trajectories – i.e. particular historical configurations of agriculture, extractivism, mobility and sedentism in inter-generational household livelihood pathways. This implies that the local agro-ecological knowledge and practice of different populations are bound up in their history of making a living (and therefore being) in certain landscapes characterized by particular affordances (Ingold Citation2000; Harris Citation2005).

4. Capturing livelihood differentiation on the Negro and Madeira rivers

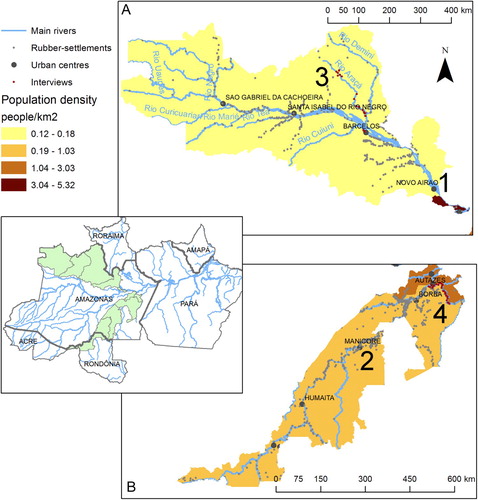

We collected data using mixed methods in three stages;Footnote7 the first two focused on the Negro and Madeira, whilst the final stage focused a tributary of each of these rivers ().

Initial participant observation, oral histories and open interviews on the Negro by JAF, which led to the formulation of research questions (section 5).

Semi-structured interviews and oral livelihood histories on the Negro and Madeira by JAF and TMC, in order to determine the extent of the pattern of agricultural, extractivist and agro-extractivist trajectories and current livelihoods of families (sections 6 and 7).

Two larger scale quantitative surveys of livelihoods by LP, in order to test these patterns. The first was conducted on the Aracá tributary of the Negro, and the second on the Abacaxis tributaryFootnote8 of the Madeira, with broadly similar environmental and historical conditions to those of their parent rivers (section 8).

Figure 1. Four research locations and distribution of historical rubber production sites (colocações) in Amazonas State, Brazil. (note: data on rubber production sites from www.sipam.gov.br). A, The black-water River Negro watershed; B, part of the white-water River Madeira watershed. No. 1 indicates the lower Negro research area, No. 2 indicates the middle Madeira research area, No. 3 indicates the Aracá research area and No. 4 indicates the Abacaxi research area. Dots along the Aracá and Abacaxi sub-tributaries mark the approximate locations of families interviewed in the quantitative surveys by LP.

The social structure of the rural population of each study region is distinct. On the Negro, families with discrete geographical origins occupy individual landholdings. There is a significant diversity of origins and histories within a relatively small area. For instance, the Sobrado ‘community’ actually consists of dispersed homesteads on the south bank of the Negro, stretching some 20 kilometers upstream from the town of Novo Airão (urban population 10,794; IBGE Citation2007), along with various homesteads located on two small tributaries, the Curuçá and Sobrado. On the Madeira, communities are composed of several large clusters, each a multi-generational family group. It was therefore necessary to visit several Madeira communities in order to obtain a sample that was comparable to that of the Negro study area. We selected small and large communities going upstream along the Madeira from the town of Manicoré (urban population 19,625; IBGE Citation2007).

Semi-structured interviews and oral histories on the Madeira and Negro by JAF and TMC in 2006 and 2007 were conducted in Portuguese, lasting from 30 minutes to one hour, and were transcribed by hand. Families were asked about their migration history, and parents’, grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ livelihood activities. Families were asked to estimate how many months of the year they spent practicing different livelihood activities. We then assigned them to one of the three livelihood categories outlined at the beginning of the paper; this was verified through participant observation and talking to other families. For example, a predominantly extractivist family was identified by either a total absence of manioc fields, or very small fields (< 0.25 ha), and six or more months of the year spent buying manioc flour.

Data from participant observation, open interviews and oral histories were later coded by searching for information about (1) whether current livelihood activities were predominantly agricultural or extractivist, (2) whether historical trajectories were primarily agricultural or extractivist (this was determined by inference from the livelihood activities of parents and grandparents), and (3) whether the family was local or had migrated only within the river, or if they were first-generation migrants from elsewhere in Amazonia or beyond. Open interviews on regional history were also carried out with locals in the towns of Novo Airão and Manicoré.

LP assessed riverine settlement and livelihoods on the Abacaxis River in August 2007 and the Aracá River in October 2007 (). These roadless watersheds serve as examples of the sub-tributaries in our white-water (Madeira) and black-water (Negro) regions. On each river, LP traveled upriver as far as the last household (400 km), and then returned slowly downstream, stopping and conducting structured interviews at settlements en route. LP interviewed river-dwellers at 16 settlements along the Aracá River and 26 settlements along the Abacaxi River (). Settlements were chosen from a stratified sample along each river. Both samples included small settlements (from one household) and large settlements. The data were collected following structured interviews with residents and community leaders. We assessed the spatial distribution of rural populations and their geographical origin for the entire Negro and Madeira study areas, using 2007 census data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE Citation2007). We derived human population density estimates from the area of each census sector, a sub-municipal scale used for the administration of governmental censuses.

5. Local understandings of livelihood differentiation

This section presents the views of Amazonian peasants who (like Henrique at the beginning of the paper) had migrated to the lower Negro river on the relationship of different kinds of current livelihood activity to divergent regional economic histories and agro-ecological trajectories. Agriculturalist migrants from white-water regions were surprised at the relative lack of agriculture and dominance of extractivism on the Negro. A common viewpoint that we encountered is expressed in the idea that families from white-water regions tend to engage in relatively more agriculture whilst those from black water regions tend to engage more in extractivism.

For example, a family that arrived there in 1960 from the white-water Solimões River claimed that no one grew manioc along the Negro when they arrived. They recall that people worked cutting wood and purchased big sacks of farinha (manioc flour) from Manaus, the state capital. This family stated that people did not know how to plant manioc correctly and were not (and are still not) interested in agriculture. They had to go to the opposite bank of the Negro in order to find manioc cuttings. They planted several hectares and said that people were impressed because they had never seen such big fields.

According to this family, the residents of the Negro used to live, and still live, ‘apehiado’ (struggling to make ends meet), because they have to buy farinha with the money they get from harvesting timber and other extractive goods. As one of them commented, ‘the people here were children of seringa [rubber], they didn’t know how to plant’. This family’s experiences illustrate the distinct realities they encountered in the Negro region compared to the white-water River Solimões. The assertion that people are ‘children of seringa’ [rubber, but what they mean is forest extractivism generally] shows the extent to which incomers believe that an extractivist history has influenced contemporary livelihoods on the Negro.

Another migrant from the Solimões River explained, ‘the majority of the people here don’t plant. People born here on the Negro were born into that rhythm [extractivism], they do not know any other way’. Another recent migrant noted that

on the Solimões [River] my family and everyone else plants a lot of bitter and sweet manioc, banana and vegetables. Here on the Negro it’s just fishing and timber. People from white-water [regions] aren’t like the people from here. People from the Solimões [River] have got a different vision, it's more one of planting. Here people say, ‘today I’ll go hunting, collect lianas or copaiba [a medicinal oil tapped from trees of Copaifera spp.]’.

Amazonian peasants who grew up on the Negro also recognize the influence history has on their current livelihoods. As one migrant from the Unini River [a black-water sub-tributary of the Negro] stated,

My father used to work with sorva [a latex from Couma spp. trees], rubber, copaiba, and make canoes. I work with the same things that my father did … . We work with these things because they these are the things we know how to work with.

Oral histories demonstrated just how little freedom many workers on the Negro had historically. In one case, a boss traveled over 1000 km from the Solimões River to the Unini River, bringing his indebted workers with him. Another informant recounted that a boss traveled over 1000 km from the Juruá River, picking up workers on the Negro. Yet another boss lived on the Negro and took his workers up to work in the Jaú River on the middle Negro. Alternatively, extractivists would themselves travel long distances for seasonal work. That workers traveled far from their home communities resulted in a monopoly of power for bosses, and they often denied workers the opportunity for community formation and manioc farming.

A resident of Communidade Sobrado, who grew up on the Unini, explains how these processes shape family histories and current livelihoods:

On the Unini people always used to be in debt to their patrão, and he used to prevent them from planting manioc. For the people who planted manioc, they [the patrões] refused aviamento. The patrões only extended goods on credit to those who worked in the forest. Only people who had a good patrão were allowed to plant manioc, but most people didn’t plant manioc because of their patrão. They also thought it was easier to work in the forest. Most people had been taken there by patrões to whom they were in debt. On the Solimões people were Pirarucu fisherman, and sold farinha. Our patrão took more than 50 people there to work on the Unini, all of whom were in debt to him. In the period [mid-twentieth century] there were only three patrões on this river. The other two patrões didn’t allow people to plant manioc. The prohibition on manioc ended when various regatões [itinerant traders] entered the river and offered aviamento, allowing people to plant … . Today I make a living going on fishing trips with my patrão. I don’t plant manioc because I don’t really know how.

6. Livelihood trajectories and mutuality-market dialectics on the Negro

Our Negro study area has a low population density, just 0.29 people per square kilometer (; IBGE Citation2007). Our interview data revealed that 16 families (53 percent) with predominantly extractivist livelihood activities came from an extractivist livelihood trajectory, and were born on the Negro, whilst a second group, comprised of 10 families (33 percent) with predominantly agricultural livelihood activities, were first-generation migrants from white-water rivers of Amazonia, or elsewhere in Brazil (). Only four families deviated from this pattern. These families were found to be practicing either agricultural (seven percent, two families) or agro-extractivist (seven percent, two families) livelihoods, despite having been born on the Negro. Closer examination reveals agricultural influences in the histories of these two families, however: The grandparents of one family were farmers from Tefé, and the family returned to farming on the lower Negro after a period of extractivism on the Unini River. The male head of the other family had an indigenous mother, a farmer from the upper Negro. Hence, amongst our sample of peasants on the Negro the majority (83 percent) of agriculturalists (i.e. those whose livelihoods were predominantly agriculturally oriented) were first-generation migrants from other regions. Only 17 percent of the agriculturalists were born on the Negro.Footnote9

Table 1. Livelihoods and histories of 30 families living in individual homesteads along the black-water River Negro, and of 40 families living in communities along the white-water River Madeira.

The scarcity of long-term communities with close kinship ties on the lower Negro is due to the extractivist history of most families, which is characterized by peripatetic livelihoods owing to the mobility required by their extractivist livelihood activities which did not permit cluster formation.Footnote10 Data from our interviews show that many families living on the lower Negro today have recently (over the last 50 years) migrated from other regions (either the middle Negro, or elsewhere in Amazonas state or beyond), and kinship relations between them are only beginning this generation. Families tend to live apart in individual homesteads a short canoe ride or walk from one another; the mobility of families in recent history has not permitted sedentary patterns of settlement required for the formation of clusters and the kinship-based communities they enable.

Some families do not even see themselves as part of a community, a common refrain being ‘they are not my kin’, underlining how kinship is a prerequisite for community and mutuality. Others stated that they prefer to remain apart as they see no reason to participate in the community. This situation constrains the inhabitants’ ability to engage in agriculture as, although there is a community puxirum, it functions poorly. Census data support these observations, showing that 136 people (5.7 percent of the population) in our Negro study area were from other municipalities in Amazonas State. This was as much as 18.2 percent of the population of one locality, Igarapé Sobrado.

The common thread running through oral histories of families from the Negro is many years of family involvement in forest extractivism on the Negro, and the peripatetic livelihoods this entailed. Various informants in this group recall their formative years working in the forests on the middle or lower Negro extracting piaçava (Leopoldinia piassaba), sorva, balata, rubber and timber, and hunting animals for skins. Families who were born in other regions of the Negro and arrived over the last 50 years make a living from varying combinations of manioc farming, fishing,Footnote11 extracting lianas (the vines used for handicrafts) and copaíbaFootnote12 (Copaifera spp.), timber and making charcoal and barbecue sticks. While nearly all families cultivate manioc, many do not produce enough to feed the family throughout the year ().

Amazonian peasant families for whom agriculture constitutes a significant livelihood activity on the Negro tend to be migrants from the white-water Solimões River or peri-urban areas in the Iranduba region close to Manaus.Footnote13 Their parents were mostly farmers, and therefore it is reasonable to assume they learned agricultural practice from an early age (). Several more entrepreneurial families actively sought out and cultivated ADE sites, the only fertile soils present on terra firme along the Negro, cultivating a wider suite of crops than on background soils (German Citation2003).

The origins of these patterns can be traced back to the rubber boom (1860–1920), during which the Negro received far fewer migrants from Brazil’s Northeast than white-water regions such as the Madeira and Solimões did. On the middle and lower Negro, workers were subject to a more exploitative market system of aviamento, where they were exploited by a few bosses who monopolized the supply of manufactured goods in exchange for forest products. Bosses would take workers on long journeys up remote rivers for months on end, sometimes traveling to other regions of the Amazon. Species of rubber trees on the Negro, Hevea microphylla and Hevea benthamiana, produce inferior-quality latex and are relatively unproductive. The superior Hevea brasiliensis, widespread on white-water rivers and their (black-water) sub-tributaries, is absent on the Negro (Dean Citation1982). Hence, the pattern of widespread rubber production at relatively fixed locales that became communities that characterized white-water rivers such as the Solimões and Madeira was not replicated on the Negro. shows that along the Madeira historic rubber settlements clustered along the main channel, while along the Negro they were more remote and widely distributed along sub-tributaries.

The rubber-tapping that was done along the Negro was undertaken by Native Amazonians from the upper Negro, rather than settlers from the Northeast (Ribeiro Citation1992). By the middle of the eighteenth century, the Indigenous population of the lower Negro had been almost totally annihilated through a combination of disease, warfare and forced labor.Footnote14 Rubber bosses forced Native AmazoniansFootnote15 from the upper Negro to travel downriver and tap rubber under debt peonage (Prang Citation2001). This is an important factor in explaining the lack of long-term communities in the Negro region. Northeasterners had no choice but to settle, whereas Native Amazonians sought a return to their communities upstream. Alternatively, extractivists would themselves travel long distances for seasonal work. The monopoly of power resulted in little autonomy for workers. Wide dispersal of extractive resources in the Negro region resulted in low population density over a large area, thus preventing the emergence of denser, more sedentary populations that characterized other regions of the Amazon, such as the Madeira (Prang Citation2001, 130).Footnote16

To conclude, we found that historic market-mutuality dialectics have impeded community formation on the Negro, with the concomitant lack of benefits of agricultural labor availability, and this explains the tendency for extractivist livelihoods on this black-water river today. This is evidenced in the finding that on the Negro, peasant communities consist of loose-knit, dispersed homesteads made up of recent migrants with discrete origins, with kinship only emerging amongst them in the present generation. There was no large influx of migrants who settled during the rubber boom, as there was in other areas. Rather, given the early decimation of the region’s indigenous population, rubber tapping was performed mainly by indigenous people from the upper Negro, who subsequently returned to their homelands rather than settle. The ongoing primacy of extractivism on the Rio Negro is also the outcome of historical trajectories characterized by mobile life-ways, working primarily in extractivism and corresponding reliance on patrões for aviamento. This is linked to a historical lack of agriculture owing to this mobility, and paucity of long-term communities and resulting lack of kinship. Hence, along the Negro the relationship of peasants to the market was relatively coercive, demanded greater mobility and so constrained the mutuality and community formation. Another factor impeding agriculture has been the capital and markets for timber, owing to the close proximity of Manaus. Additional factors contributing to the constraining of community formation on the Negro are to be found in the restricted availability of natural resources – specifically, much smaller patches of ADE, wide dispersal and lower value of extractive forest products (for example, the weaker Heveas of the region), lower fish stocks compared to white-water regions, and possibly the lower fertility of background soils.

7. Livelihood trajectories and mutuality-market dialectics on the Madeira

Population densities are much higher in the Madeira study area than the Negro, there are 1.56 inhabitants per square kilometer despite the fact that much of the area is floodplain (; IBGE Citation2007) On the Madeira, we observed greater homogeneity of livelihood history and community origins amongst families (). All were born in the region and have emerged from agro-extractivist livelihood trajectories. Today, agricultural livelihoods are predominant amongst rural peasants on the Madeira. The main variation appears to be between the majority whose predominant livelihood activity is agriculture, and eight families who practice agro-extractivism. No families had predominantly extractivist livelihoods at the time of our interviews. Hence, the Madeira data confirm the idea that regions where people had greater autonomy during the rubber boom are today characterized as long-term agricultural communities.

Oral histories reveal the trajectories which shaped these current livelihoods. On the Madeira, with some exceptions, a more egalitarian form of aviamento became prevalent among peasants as the rubber boom progressed, permitting community formation. This relative autonomy enabled many rubber-tapping families to practice agriculture. This contrasts with more exploitative operations in more remote white-water rivers such as the River Juruá and upper River Purús, where agriculture was forbidden, as it was on the tributaries of the Negro. On the Madeira, rubber and Brazil nut trees are abundant near the main river channel. These factors made settlement of riparian areas attractive, and clusters grew into kin-based communities. This contributed to the greater degree of sedentism that has characterized their life histories to the present day. Numerous informants stated that it was their great-grandparents who first occupied (and often legally registered) the land where they now live. This allowed for the development of kinship relations, the institutions of puxirum and putáua, and the widespread practice of agriculture. Interviewees on the Madeira consistently reported that agriculture became the principal livelihood activity in the municipality in the late 1970s. This was presumably the tipping point between the strength of international demand for forest products and local and regional demand for agricultural produce. This period of 30 years fits well with this argument given the transition of Brazilian Amazonia to a mainly urbanized population (50.3 percent) by 1980 (IBGE Citation2000), which has increased the demand for agricultural products.

Interviews with elders revealed that, historically, the extractivism in the area occupied today by the communities of the North bank of the Madeira was controlled by three bosses. Workers were not subject to coercion and were relatively autonomous, even when they lived on land owned by one of the bosses. Smallholders lived along the high-levee floodplain, which was the site of extensive home gardens rich in rubber and cacao groves. People made a living from harvesting rubber and Brazil nuts, along with other extractive products including balata and sorva. They also planted manioc in the floodplain and on the terra firme. There were various small barracões (rubber warehouses) in the region, some with a small number of resident workers; as elsewhere, inhabitants obtained manufactured goods in exchange for their produce at the barracões.

On the Manicoré River, rubber and Brazil nut extraction took place through small-scale enterprises, typified by more egalitarian relations. There were no large operations with exploitative bosses. Instead the river was characterized by individual landholdings, upon which communities eventually developed. During this period, both landholders and river-borne traders engaged in relations of aviamento with inhabitants of the river and migrant workers. Extractive activity was more prevalent than it is today, but agriculture was always practiced. During the rubber boom, the rubber of these villages and of the river in general was produced by a series of smaller, more family-oriented enterprises, each with between one and 10 rubber trails. The workers of each barracão were people who lived with their families on the river, and seasonal workers who lived at the barracões during the summer rubber season.

This allowed families greater autonomy in the market – the existence of many smaller bosses, and even smallholders engaging in relationships of aviamento among themselves, meant that people had more choice over who they worked for and who they accrued debts with. The river was inhabited by people who had their own land (or had access to the land of others) and, while working seasonally gathering rubber and other extractive products, also engaged in subsistence agriculture. After the Second World War the bosses abandoned their barracões (owing to the drastic reduction in the value of rubber), thereby ending their reign as middlemen and allowing the long-term residents of the river to deal directly with the river traders. As one informant put it, ‘when the patrões left we took over aviamento’. The communities along the river today are extended family clusters with collective landownership and agricultural trajectories with their roots in the rubber boom period or even earlier, especially when inter-marrying with local indigenous peoples occurred. This has emerged from several generations of cohabitation, during which kinship relations among all residents were established, and so the original landowner usually ended up being related to the whole community, kinship then conferring de facto collective land rights onto them.

As the importance of extractivism in local livelihoods declined from the 1970s forward, and agriculture grew in importance, the significance of bosses diminished. Examining family histories shows a shift from the previous generation. While before, some men engaged in seasonal extractivism, sometimes traveling to distant locations, today only a few families derive significant income from seasonal extractivism (). As an outcome of these historical processes, the Madeira is characterized by widespread mutuality centered on communities that have grown out of small family landholdings occupied by people related by kinship, with continuous histories stretching back for up to 150 years. The livelihood history of the region was shaped by more egalitarian relations of land tenure and aviamento, which allowed the development of long-term communities and enabled the development of agricultural knowledge and practice. Census data show that very few people have migrated from other municipalities in Amazonas state: only five individuals (0.3 percent). There were also four people from elsewhere in Brazil. Hence, according to census data, only nine people grew up outside the area that they reside in today.

The origins of these patterns can be traced back to the colonization of the Madeira River and the generation of its contemporary peasant population, which occurred during the second half of the nineteenth century (Amoroso Citation1992; Menédez Citation1992); there was a significant Native Amazonian presence along the river and its tributaries until the Cabanagem in the late 1830s (Harris Citation2010). Native Amazonians along the Madeira strongly resisted conquest and were decimated considerably later than the tribes along the middle and lower Negro were.Footnote17 The Madeira received many thousands of migrants from the Northeast of Brazil during the rubber boom. Both of these factors are reflected in the composition of communities on the middle Madeira today. In addition to various indigenous reserves, there are communities that, while not self-identifying as indigenous, emphasize that they are ‘gente daqui’ (people from here), while people in other communities trace one or both grandparents to migrations from Brazil’s Northeast. With around a hundred years or more of existence, many complex family clusters have formed on the Madeira, and these form the basis of most communities in the region. Communities in the region claim to be ‘tudo parente’ (all kin), as most members are related. This history of residence and kinship means that people are strongly tied to one another and to the land on which they were raised.

To conclude, we found that mutuality-market dialectics along the Madeira enabled widespread community formation historically. The outcome of this is that today community members are all related as kin, which makes labor available, and this explains the tendency for more agricultural livelihoods today. This can be traced to the large influx of migrants who settled during the rubber boom, the area made more attractive by concentrations of extractive resources, fertile floodplain soils, abundant aquatic protein and large patches of ADE. In addition, Native Amazonian populations of the region were ‘pacified’ much later than those of the Negro, and they are more evident in the make-up of Amazonian peasantry today on the Madeira. The outcome of stronger community history and mutuality, and the institutions of the puxirum and putáua that underwrote this, is that compared to the Negro, on the Madeira peasants were able to resist the more coercive elements of aviamento (that is, the market) and historically engage in more semi-autonomous agriculture combined with a more sedentary extractivism owing to the abovementioned concentration of extractive resources. This permitted sedentary forms of agro-extractivism historically, which is what enabled community formation in the first place, along with the pervasive kinship relations, and more widespread practice of agriculture which is an important factor in maintaining higher population densities over time.

8. Livelihoods on the sub-tributaries: the River Abacaxi and the River Aracá

Quantitative survey data from rural settlements along the Aracá River (a sub-tributary of the Negro) and Abacaxis River (a sub-tributary of the Madeira) confirmed our findings from oral histories and interview data: peasant livelihoods on a tributary of the Negro tended towards extractivism, while those on a tributary of the Madeira tended towards agriculture (). On average, communities on the black-water River Aracá were small (mean = 8.9 households), and predominantly extractivist livelihoods (whether for household consumption or sale) were commonplace. Only 53.1 percent of the 143 households from the 16 surveyed settlements had agricultural fields, mainly of manioc. In contrast, 71.3 percent of households extracted Brazil nuts, 58.0 percent harvested timber (various species), 52.4 percent made charcoal and 27.3 percent extracted the plant fiber piaçava. Communities along the River Abacaxi, on the other hand, were larger (mean = 18.3 households) and less remote. The last settlement on this river was only 187 km from the nearest urban center, compared to 400 km on the black-water River Aracá, where the headwaters had already been abandoned (see Parry et al. Citation2010). Overall, 67.6 percent of the 476 households from the 26 surveyed communities on the River Abacaxis had agricultural fields, also dominated by manioc. There was also far less extractivism in this white-water region, with only 22.9 percent of households harvesting timber (various species), 16 percent making charcoal and six percent tapping the tree oil of Copaifera spp. On the Abacaxis River, 18.9 percent of families engaged in fishing, compared to 100 percent of families on the Aracá River. The vast majority of the interviewees on these two sub-tributaries were from Amazonas state. Along the Aracá River, none of the interviewees was from a white-water river – most were born on the Aracá River itself (12), while a few came from other municipalities on the Negro (three), and one from Manaus. On the Abacaxis River no one came from black-water areas; most were born on the Abacaxis River itself (20) though six came from other municipalities of the Madeira.

Table 2. Salient characteristics of Amazonian peasant livelihoods of the lower Negro and middle Madeira rivers.

9. Discussion and conclusions

Scoones (Citation2015) argues that livelihood approaches need a better understanding of political economy, and by drawing on the work of Stephen Gudeman and demonstrating its utility in explaining Amazonian peasant livelihoods we hope to have contributed to such an understanding. Our two cases demonstrated how divergent mutuality-market dialectics shaped the degree to which community formation occurred historically, which is key to understanding the relative weight of agricultural and extractivist activity in Amazonian peasant livelihoods today. None of this would have emerged had we taken an economistic approach to livelihood. Academic and policy approaches to peasants, their livelihoods and their relationships to the community and market are typically represented in terms of the rational management of a set of capital assets. This, we argued, places too much emphasis on the formal, market realm of exchange values and too little on the substantive realm of mutuality in understanding peasant livelihood strategies. This paper set out to provide an alternative understanding of Amazonian peasant livelihoods, using a lens of mutuality-market dialectics in order to reveal how current livelihood strategies are differentiated by their emergence from economic histories in two different regions. Below, we summarize findings and finally discuss significance of this lens for policy and understanding of peasant livelihoods. Three intersecting lessons emerge from our findings on mutuality-market dialectics:

First, diverging historical livelihood trajectories shape current skills and perceptions of the environment, along with agro-ecological knowledge and practice, and so inform land and natural resource management decision-making by peasants. We revealed that there is evidence for the existence of what some Amazonian peasants understood as sedimented patterns of livelihood orientation and activity emergent from agro-extractivist trajectories (detailed in section 5). These have, over generations, shaped perceptions of the environment, skills and agro-ecological knowledge which in turn shape livelihood strategies. The outcome of this, we argued in section 7, is that on the Madeira, generations of agricultural livelihoods enabled by historical mutuality-market dialectics which permitted community formation shape agriculturally oriented skills and perceptions of the environment among the current generation, as parents reveal the affordances of the environment to children in particular ways (Ingold Citation2000; Harris Citation2005). Conversely, generations of extractivist livelihoods shaped by mutuality-market dialectics which constrained community formation shape extractivist-oriented skills and perceptions of the environment among the current generation on the Negro. This implies that even as kin-based communities form, peasants emerging from extractivist livelihood trajectories may continue to engage in predominantly extractivist livelihoods, as we argued in section 6. This would also appear to be supported by our quantitative survey presented in section 8.

Second, economic history – that is, the particular form that the market (i.e. aviamento) took, not environmental differences as such – explains this differentiation of livelihood trajectories. What we mean by this is that where aviamento was less coercive, mutuality-market dialectics permitted community formation and therefore labor for agriculture. Where it was more coercive, mutuality-market dialectics inhibited the emergence of the community and therefore also constrained the practice of agriculture. In other words, the particular form that aviamento took (more or less coercive) correlated with settlement dynamics (more or less mutuality). This would appear to suggest that the local perspectives that we presented in section 5 are overly environmentally determinist. Our findings did, however, point to a secondary role for environmental factors: in more nutrient-rich white-water regions, concentrated extractive resources meant that the formation of sedentary long-term communities practicing agro-extractivism was viable. In black-water regions, which are more nutrient poor, with more widely dispersed resources, more peripatetic lifestyles were often the only viable option for extractivists, curtailing their ability to cultivate for which sedentism is a pre-requisite. Our quantitative survey verified these findings on tributaries of the Negro and Madeira.

Third, we demonstrated that the degree to which community formation and the kinds of mutuality this affords could occur is contingent on the degrees of freedom versus bondage which were characteristic of different extractive regimes. This concentration of extractive resources along the Madeira permitted sedentism and the formation of kin-based communities, with mutuality in the form of the puxirum and putáua institutions, underwriting not only the ability to mobilize labor for agriculture but also more egalitarian forms of aviamento. On the Negro, conversely, the dispersal of extractive resources and higher mobility of workers enabled bosses to engage in more exploitative market practices through more a more coercive form of aviamento. This constrained the formation of more sedentary communities, and so mutuality, and therefore the ability to mobilize kin for agricultural labor. In such regions where relations with extractive bosses were more coercive, communities only began to form over the last generation, whilst in regions where peasantries had greater autonomy, communities formed several generations ago. The need to be able to mobilize labor for agriculture means that areas with long-term kin-based communities underwritten by mutuality can practice more agriculture today, and this has led to major differences in terms of the primacy of either agriculture or extractivism in livelihoods of different regions.

The key importance of our findings for livelihood studies is that people’s current livelihood strategies and perceptions of the environment appear to be as strongly shaped by historically contingent mutuality-market dialects as they are by people acting as rational utility maximizers. Hence, policy needs to take history seriously, in particular how diverging economic histories vis-à-vis resource availabilities shape contemporary livelihoods. For example, capturing the diversity of household economies is important in understanding deforestation patterns (Castro Citation2005). A limitation of our study is that it did not attempt to address the question of whether it is possible to reconcile theoretically dialectical with economistic approaches to livelihood. Are they inherently antagonistic in terms of their underlying philosophies, or is there scope to combine aspects of them? Engagement with such questions could contribute to a much-needed re-pluralization of approaches to livelihood in academia and policy.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonyous reviewers for their comments which helped us signficantly improve an earlier version of the manuscript, and Jun and the JPS team for their efficient handling of the editorial process. James Fraser thanks the Leverhulme Trust [grant number F/00 230/W] and CNPq [grant number EXC 022/05]. Angela Steward thanks the Mamirauá Sustainable Development Institute (MCTI) for institutional support during writing. Luke Parry thanks the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ESRC; ES/K010018/1] and CNPq [grant number CsF PVE 313742/2013â 8].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

James Angus Fraser

James Angus Fraser is a lecturer in the Lancaster Environment Centre (LEC) at Lancaster University, UK. He is in the political ecology research group at LEC. His research focuses on social and environmental dimensions of smallholder natural resource management in the humid tropics of Latin America and Africa. He focuses in particular on local agro-ecological knowledge, and social and environmental justice issues. He investigates these with theory and methods from a variety of disciplines, including anthropology, geography and development studies.

Thiago Cardoso

Thiago Mota Cardoso is a postdoctoral fellow in the postgraduate program in anthropology at the Federal University of Bahia. He lectures at the School of Conservation and Sustainability (ESCAS) and is a member of the research groups CANOA (the Environment, Practices and Perception Collective at the Federal University of Santa Catarina) and PACTA (Local Populations, Agrobiodiversity and Traditional Knowledge). He is also involved in the AURA project (Aarhus University Research on Anthropocene), “Uncovering the potential of unintentional design in anthropic landscapes”. He works primarily in Brazil, in the Amazon and Atlantic Forest biomes, with traditional communities and indigenous peoples, on themes such as agriculture and agrobiodiversity, resilience and communal systems, political ecology and local-global transformations, landscape anthropology and traditional territories. Email: [email protected]

Angela Steward

Angela May Steward is an assistant professor at the Center for Agrarian Studies and Rural Development, Federal University of Pará, Brazil. She is also a research collaborator at the Mamirauá Institute for Sustainable Development, Amazonas state, Brazil, where she leads the Research Group in Amazonian Agriculture, Biodiversity and Sustainable Management. Her research focuses on questions of natural resource management and local knowledge systems, with a focus on agricultural systems. She works primarily in Brazil, with traditional and Quilombo peoples, examining practices and systems within the context of broad social, political and environmental transformations, including changes in land tenure, livelihood diversification, conservation and development policies, and climate change. Email: [email protected]

Luke Parry

Luke Parry is a lecturer in the Lancaster Environment Centre (LEC) at Lancaster University, UK. He is in the political ecology research group at LEC. He has also just finished a position (2014–2016) as a Special Visiting Researcher (PVE) at the Nucleus of Advanced Amazonian Studies (NAEA), Federal University of Pará, Belém, Brazil. His research interests include urbanization and linkages with extreme climatic events and food insecurity. The geographic focus of his research is the Brazilian Amazon, particularly in the roadless areas of Amazonas State. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 REDD+ is a policy framework for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing countries, along with the conservation and sustainable management of forests, and forest carbon stock enhancement. PES stands for payments for ecosystem services. These are market-based mechanisms to pay landowners for actions to manage ecological services provided by their land or watersheds. PES are, then, similar to subsidies or taxes, and seek to encourage the conservation of natural resources.

2 Over the past few decades agriculture has declined, from a livelihoods and economic perspective, due to the emergence of off-farm income streams such as retirement, bolsa familia and professional employment (i.e. teachers, health agents).

3 In critical theory and post-colonial studies, subaltern refers to the populations outside of the hegemonic power structure. The point of using it is that it works as a meta-category embracing marginalized indigenous, peasant, afro-descendant, mestizo, campesino etc. groups without conceptually privileging any of them.

4 This followed the decimation of the Indigenous chiefdoms of Amazonia by colonial epidemics; from the early 1600s, Jesuits founded missions along the major rivers (Solimões, Negro and Amazon) in Central Amazonia (Sweet Citation1974). Missions ran on a system of forced labor, with turtle oil, spices, hardwoods, vegetable oils and cocoa beans gathered by Native Amazonians and the emergent Amazonian peasantry. From 1758 to 1798, around 60 Portuguese missions in Amazonia were placed under the control of civil administrators, under a new administration known as the Directorate.

5 This system defined the production of rubber (Hevea spp.) Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa), rosewood (Aniba roseiodora), sorva, jute (Corchorus capsularis) and balata (Manilkara spp.), each of which experienced a boom during the last 150 years.

6 Conditions in the Western Amazonia, notably those in the Brazilian State of Acre, and in Peru and Colombia were usually harsher than in Eastern Amazonia (Hecht Citation2013; Taussig Citation1987; Davis Citation1997). In the west, bosses monopolized the supply of manufactured goods which were sold in advance at highly inflated prices, and manioc agriculture was forbidden, thus ensuring continued indebtedness and dominance over workers, but also preventing the very formation of the community sphere, given the centrality of manioc farming to community formation.

7 Participant observation and open-ended life-history interviews were conducted with households (normally with both male and female adult family heads together); on the lower Negro River by JAF and TMC (n = 25, during March–June 2006) and on the middle Madeira River by JAF (n = 25, during September 2006–January 2007) ().

8 The Abacaxis River is not black-water in the same sense that the Negro and its upper tributaries are. Black-water rivers in white-water regions feature greater concentrations of extractive resources, and more productive fisheries, than black-water rivers in black-water regions do.

9 The kinds of livelihoods in which people engage are therefore shaped by their particular agro-ecological trajectories. Many caboclos from the lower Negro River and its tributaries engaged more in extractive livelihoods (timber, fishing, extraction of forest products). Oral histories from the north and south banks of the lower Negro River reveal that the mainstay of the regional economy over the last half-century or more has been timber. The long-term residents of the region (related by kinship but not as closely as the caboclos of the middle Madeira River, and not co-resident) are those most involved in the (illegal) timber trade. Locals in community Sobrado suggest that this is because they have been involved in timber for so long, and therefore have the connections and knowledge to avoid getting caught by IBAMA (the Brazilian Environmental Protection Agency). Timber has long been a mainstay of the local economy owing to the massive demand for wood for boat-building and construction in the city of Manaus, which has expanded dramatically over the last 50 years. Elsewhere, on the Apuaú River, there has been serious conflict between local residents and IBAMA over rights to timber, fishing and hunting on the river. This conflict cumulated in the expulsion of many residents and the installation of a permanent IBAMA presence at the mouth of the river to monitor traffic.

10 Other factors that have contributed to this include the shifting of the population of Velho Airão (a now abandoned town on the middle Negro) to Novo Airão, and the expulsion of inhabitants of the River Jaú with the creation of the National Park in 1980 and the resulting disintegration of communities along the Unini River, which caused significant migration to the lower Negro, where people hoped to find better access to markets, health and education (). The communities and kinship ties that existed or had been expanding in the source regions were disrupted by these processes.