ABSTRACT

This contribution addresses the growing global trend to promote ‘natural capital accounting’ (NCA) in support of environmental conservation. NCA seeks to harness the economic value of conserved nature to incentivize local resource users to forgo the opportunity costs of extractive activities. We suggest that this represents a form of neoliberal biopower/biopolitics seeking to defend life by demonstrating its ‘profitability’ and hence right to exist. While little finance actually reaches communities through this strategy, substantial funding still flows into the idea of ‘natural capital’ as the basis of improving rural livelihoods. Drawing on two cases in Southeast Asia, we show that NCA initiatives may compel some local people to value ecosystem services in financial terms, yet in most cases this perspective remains partial and fragmented in communities where such initiatives produce a range of unintended outcomes. When the envisioned environmental markets fail to develop and benefits remain largely intangible, NCA fails to meet the growing material aspirations of farmers while also offering little if any bulwark against their using forests more intensively and/or enrolling in lucrative extractive enterprise. We thus conclude that NCA in practice may become the antithesis of conservation by actually encouraging the resource extraction it intends to combat.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the global conservation movement has increasingly embraced ‘natural capital accounting’ (NCA) as a key strategy for environmental protection. Through an intricate web of partnerships, states, private-sector firms and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have developed a variety of initiatives intended to assign economic value to ‘ecosystem services’ that are then supposed to be maintained through appropriate pricing and preservation as ‘natural capital’ (Sullivan Citation2013, Citation2017a). In this way, NCA ‘aspires to incorporate all aspects of valued external nature within accounting practices’ consonant ‘with the contemporary market economy’ (Sullivan Citation2017b, 397). This campaign rests on the assumption that if natural resources can be valued financially, a critical mass of people – from global policymakers to local resource users – will be motivated to defend them.

NCA is part of a widespread trend toward neoliberalization within conservation governance evident throughout the world (Büscher, Dressler, and Fletcher Citation2014). This trend promotes market-based instruments (MBIs) for environmental management (e.g. ecotourism, payment for environmental services and carbon markets) to incentivize ‘stakeholders’ to favor conservation over resource extraction. Strong concerns have been raised about this strategy, questioning its reduction of environmental value to narrow economic measures (Büscher and Fletcher Citation2015), its contribution to ‘green grabbing’ (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2012) and how actual investments in MBIs have lagged far behind their lofty promises (Dempsey and Suarez Citation2016). Yet while the vision underlying NCA promotion has been explored in various ways by ecological economists (e.g. Jansson Citation1994; Costanza et al. Citation1997, Citation2014) and others (Dempsey Citation2016; Sullivan Citation2017a, Citation2017b), how this vision is currently materializing within on-the-ground policy and practice has yet to be systematically investigated. As NCA is frequently introduced into frontier areas harboring rural, resource-dependent populations, investigating NCA’s impacts in the context of rapidly intensifying agrarian transformations remains critically important.

Here we explore two cases in which NCA has been introduced to support biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration in frontier Southeast Asia through the lens of Foucaultian biopolitics. While conservation governance has been previously analyzed as a form of biopower (Biermann and Mansfield Citation2014), such analysis has not yet engaged with Foucault’s recently published discussion of a specifically neoliberal biopolitics. We argue that NCA represents the intensification of a neoliberal biopolitics in which the central aim to nurture and sustain life is sought via incentives that emphasize nonhuman life’s potential to contribute to economic growth (termed ‘green growth’ within NCA parlance). We conclude that while NCA can strongly influence local behaviors and livelihood changes (Dressler Citation2014), in practice its effects usually remain partial and fragmented.

Indeed, our findings suggest that rather than incentivizing conservation, NCA may more commonly encourage precisely its opposite: the expansion of resource-extractive activities that threaten conservation. By encouraging local resource users to further embrace market logic for natural resource valuation while failing to deliver sufficient revenue to make in situ biodiversity preservation more valuable than lucrative extractive practices (e.g. mining, oil palm), NCA may in practice lead local communities to shift to more destructive resource uses, and ultimately to embrace conventional extractivism.

We first introduce our conceptual framework and outline the recent rise of NCA among conservationists. We then apply our framework to our empirical case studies. We demonstrate that while NCA can facilitate livelihood changes, the rhetoric and range of incentives on offer commonly misalign with local livelihoods and create conditions leading local farmers to instead embrace more exploitative options. We conclude by highlighting the implications of our analysis for future investigation concerning NCA within the context of neoliberal conservation, biopolitics and landscape change.

The analysis is based on long-term ethnographic research in the Philippines and Indonesia by Dressler and Anderson, respectively. Data collection for the Philippines ran from 2008 to 2016, and that in Indonesia from 2013 to 2016. In both areas this entailed semi-structured interviews with key NGO, government and community organization representatives as well as participant observation and focus group discussions with rural farmers. We spent weeks in homes and fields, documenting past and present farming practices (e.g. swidden) as well as responses to and outcomes (both socio-economic and biophysical) of NCA interventions. Data analysis focused most on patterns of response within and between interviews. The corresponding researchers are conversant in Filipino (Tagalog) and Bahasa Indonesian and used local translators when Pala’wan and Dayak languages were spoken. All informants gave informed consent, and all areas and respondent names are pseudonyms.

Neoliberal biopolitics

Foucault introduced ‘biopower/biopolitics’ to describe the historical change from the pre-modern sovereign’s prerogative to ‘take life or let live’ to the modern state’s claim to ‘make live and to let die’ (Citation2003, 241). While Foucault himself focused on the exercise of biopower in defense of human populations, others have extended the concept to analyze diverse phenomena (Lemke Citation2011; Mendieta Citation2014), including forms of environmental governance in defense of nonhumans, such as protected area enforcement (Luke Citation1999; Youatt Citation2008; Fletcher Citation2010; Cavanagh Citation2014).

What remains underexplored within this growing literature on environmental biopolitics, however, are the different ways in which biopower can be exercised. Initially, Foucault (Citation1978, Citation2003) described biopower as largely synonymous with the ‘governmentality’ analytic he developed simultaneously, in that both addressed power exercised at the level of (national) populations rather than over a collection of subjects or discrete individuals. This resulted in the famous ‘sovereignty–discipline–government’ triad (Foucault Citation1991, 102) that inspired the now-massive governmentality literature (Rose, O’Malley, and Valverde Citation2006; Lemke Citation2012). Yet in subsequent lectures Foucault (Citation2007, Citation2008) reworked the governmentality concept, such that it ‘progressively shifts from a precise, historically determinate sense, to a more general and abstract meaning’ (Sennellart Citation2007, 388) encompassing various strategies for the ‘conduct of conduct’. In the process, ‘discipline’ ceases to be opposed to ‘government’ but becomes instead one of several forms of an expanded governmentality.

In The birth of biopolitics, Foucault (Citation2008) distinguishes ‘disciplinary’ and ‘neoliberal’ modes of governmentality (cf. Fletcher Citation2010). While disciplinary governmentality seeks to propagate social norms and ethical standards compelling individual conformance due to fears of appearing deviant or immoral, a neoliberal governmentality aims to create external incentive structures within which subjects can be influenced through manipulation of incentives. Neoliberal governmentality thus constitutes ‘an environmental type of intervention instead of the internal subjugation of individuals’; ‘a governmentality which will act on the environment and systematically modify its variables’ (Foucault Citation2008, 260, 271).

Importantly, disciplinary and neoliberal modes of governmentality can also be understood to prescribe divergent (yet overlapping) strategies for the exercise of (bio)power. In Foucault’s early analysis, disciplinary techniques function as one of the principal means by which the (emerging modern) state exercised biopower, allowing for the manipulation of individuals’ behavior in pursuit of an optimized human existence. The subsequent rise of neoliberalism, he suggested, introduced a novel approach to biopower, prescribing different strategies for influencing subjects’ attitudes and behavior.

While Foucault did not develop this idea of a neoliberal biopower further, a nascent body of literature has begun to do so (see esp. Lemm and Vatter Citation2014). Thus far, this analysis has not been systematically applied to environmental governance, although Fletcher (Citation2010) speculates concerning how neoliberal biopower might manifest within conservation politics specifically. He suggests that

a neoliberal perspective would likely focus less on subjects’ internal states than on the external structures within which they act … interventions would be framed less in terms of morality than cost–benefit characteristics … [and] … would likely place less emphasis on nurturing and sustaining life directly than on supporting economic growth. (Citation2010, 175)

In the process, we contribute to the study of neoliberal conservation in conjunction with agrarian change. While neoliberal conservation has been analyzed extensively (Igoe and Brockington Citation2007; Büscher et al. Citation2012; Büscher, Dressler, and Fletcher Citation2014, Holmes and Cavanagh Citation2016), the lens of biopolitics adds a productive new dimension by focusing on how neoliberal interventions seek to optimize rural peoples’ valuation and use of the resources in question. While previous conservation governance tended to foreground ethical concerns and hence pursue the creation of ‘environmental subjects – people who care about the environment’ (Agrawal Citation2005, 162), contemporary interventions often minimize such concerns, seeking to instead promote decision-making via economic valuation. Here, stakeholders are encouraged to behave as ‘rational actors [who] can be motivated to exhibit appropriate behaviors through manipulation of incentives’ (Fletcher Citation2010, 173). This demands a different perspective, one that the concept of neoliberal biopolitics facilitates.

We do not claim that neoliberal biopower necessarily displaces other processes entirely, as different forms of biopower may ‘overlap, lean on each other, challenge each other, and struggle with each other’ (Foucault Citation2008, 313). As our case studies demonstrate, a disciplinary biopolitics may thus continue to be promoted alongside neoliberal interventions. Indeed, a certain mode of the former may underpin the latter, in that the inculcation of a neoliberal orientation often necessitates disciplining to produce the rational actors considered capable of appropriately evaluating incentives.

We also acknowledge that aspects of neoliberal (or other forms of) biopower promoted via environmental governance are seldom wholly internalized by target populations. Analysis from the perspective of governmentality/biopower, after all, tends to be less concerned with ‘what happened and why’ than ‘to start by asking what authorities of various sorts wanted to happen’ Rose (Citation1999, 20). Whether this intention is actually realized is explored by a body of research investigating the correspondence between ‘vision’ and ‘execution’ in environmental governance (see Carrier and West Citation2009; Anderson et al. Citation2016). Dempsey and Suarez (Citation2016), moreover, demonstrate that despite worldwide promotion of neoliberal conservation over the past decades, very little actual market exchange has taken place thus far, while most trade that does occur has been directed by states. They thus describe ‘free’ market transactions among private parties as ‘slivers of slivers of slivers’ of general financial transactions (Dempsey and Suarez Citation2016, 654).

Yet earlier research suggests that while finances often do not flow from direct market transactions per se, significant funds do manifest by way of project delivery, infrastructure development, accounting and monitoring activities and, crucially, the various incentives and conditions intended to convert rural residents into environmental defenders (Dressler Citation2014). Indeed, as Dempsey and Suarez point out, in failing to develop substantial markets conservation mechanisms may still function ‘to reinforce neoliberal political rationalities among conservationists’ and local stakeholders (Citation2016, 655). To what extent this actually succeeds in creating the envisioned (eco)rational subjects is an empirical question, one that animates our analysis below.

The rise of natural capital

While having existed for some time, the concept of natural capital has been increasingly promoted within environmental governance as part of an expanding coalition of the world’s most influential environmental organizations and corporations. In 2006, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) partnered with Stanford University to create the Natural Capital Project (Kareiva et al. Citation2011), after which the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) championed natural capital in its TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity) initiative (TEEB Citation2010). This inspired the World Bank to develop its own WAVES (Wealth Accounting and the Valuation of Ecosystem Services) program (World Bank Citation2017a) These organizations, along with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) , World Business Council for Sustainable Development, and many more, have since come together in a ‘Natural Capital Coalition’ (NCC) which recently released a ‘Natural Capital Protocol’ intended to ‘harmonize existing best practice and produce a standardized, generally-accepted, global approach’ (Gough Citation2016, 1). At the 2016 IUCN World Conservation Congress in Hawaii, NCA was prominent, with a launch celebration of the Natural Capital Protocol and announcement of an expanded coalition to develop financial instruments for NCA including new players Credit Suisse and JP Morgan Chase (IISD Citation2016).

Within this coalition the definition of natural capital remains ambiguous. In early conceptualization by ecological economists, the concept designated measurement of ‘stocks’ or ‘flows’ of natural resources (Daly Citation2014). Yet within NCA the concept’s meaning has changed significantly to emphasize the monetary value of natural resources specifically. The Natural Capital Declaration thus states: ‘The term “capital” has been borrowed from the financial sector to describe the value of the resources and ability of ecosystems to provide flows of goods and services such as water, medicines and food’ (NCD Citation2012, 1).

To incorporate natural capital into decision-making demands appropriate measurement and accounting procedures, since it is natural resources’ ostensible ‘economic invisibility’ that ‘has thus far been a major cause of their undervaluation, mismanagement and ultimately resulting loss’ (UNEP Citation2011, 8). Consequently, ‘successful environmental protection needs to be grounded in sound economics, including explicit recognition, efficient allocation, and fair distribution of the costs and benefits of conservation and sustainable use of natural resources’ (TEEB Citation2010, 3). The overarching aim is to incorporate this valuation into benefit–cost analysis, which ‘offers a rather convenient way of measuring the overall social values of alternative policies. Thus it provides a basis for making difficult policy decisions’ (Goulder and Kennedy Citation2011, 16). Benefit–cost analysis can then inform comprehensive accounting procedures assessed at various scales, from individual firms to particular sectors and beyond, such that ‘[i]deally, changes in stocks of natural capital would be evaluated in monetary terms and incorporated into the national accounts’ (UNEP Citation2011, 5).

Fundamental to NCA is thus the creation of markets in which natural resources can be bought and sold in ways that both sustain these and generate financial return to investors; to make conservation ‘not only affordable, but profitable’ (Thiam Citation2016, 3). This demands ‘[t]ruly sustainable market growth that also delivers measurable conservation benefits’ (Credit Suisse and McKinsey Citation2016, 7), commonly termed ‘green growth’. NCA thus builds on efforts over the last few decades to create global markets for trade in ecosystem services. As UNEP asserts, ‘[t]ried and tested economic mechanisms and markets exist, which can be replicated and scaled up, including from certified timber schemes, certification for rainforest products, payments for ecosystem services, benefit-sharing schemes and community-based partnerships’ (Citation2011, 9). Similarly, Credit Suisse and McKinsey highlight ‘proven project types and business models’, particularly in ‘sustainable forestry, sustainable agriculture, and ecotourism’ (Citation2016, 10).

Payment for ecosystem services (PES) is commonly considered the archetypal natural capital market – the ‘main model’ for future ‘scaling up’ of NCA. PES is also widely seen as the main model for the global REDD+ (Reduced Emissions through avoided Deforestation and land Degradation) mechanism, an ambitious effort to link campaigns to halt deforestation, conserve biodiversity and mitigate climate change. Generally conceptualized as a quintessential MBI in its aim to incentivize forest conservation by ascribing monetary values to standing forest that would cover the opportunity costs of alternative land use and so make conservation more profitable than destruction, over the last decade REDD+ has been aggressively promoted by conservation organizations and others who have initiated more than 500 pilot projects worldwide (Sunderlin et al. Citation2015). Early World Bank forecasts anticipated a USD 30 billion global market for REDD+ trade by 2030 (Mollicone et al. Citation2007).

In building on pre-existing mechanisms, such NCA schemes can be understood as an intensification (Nealon Citation2008) rather than a wholesale reinvention of the neoliberalization already promoted via conservation policy and programing in many locations over the last several decades. Yet it aims to go far beyond this as well. As place-based conservation initiatives, PES and REDD+ are limited in their capacity to generate significant liquid capital that can be grown directly through investment in financial markets. Consequently, the current emphasis in NCA is to move from concrete markets in goods and services to engagement in global financial markets – what Büscher (Citation2013) calls the pursuit of ‘liquid nature’ (see also Sullivan Citation2013). This entails abstracting value from investment in concrete projects so that it can become fungible and hence convertible across a greater range of instruments. The aim is then to combine different instruments in order to ‘bundle a diverse set of cash flows … and mold them into a single investment product’ (Credit Suisse and McKinsey Citation2016, 13) with the ultimate goal of eventually establishing conservation mechanisms as a new ‘asset class’ within conventional finance markets. On the ground, these diverse sets of cash flows work through conservation mechanisms that supposedly offer the rural poor ‘co-benefits’ and ‘low-carbon’ futures as they contend with their own political and economic struggles. As we show, these schemes obviously articulate with local livelihood needs and concerns, but typically not in ways that match poor rural residents’ hopes and aspirations. Rather than foster agency and empowerment, then, NCA promotion may also constrain it.

Such promotion is typically envisioned in neoliberal terms wherein human beings are considered rational actors functioning as ‘entrepreneurs of themselves’ who can therefore be influenced by manipulating costs versus benefits of certain courses of action (Foucault Citation2008; Fletcher Citation2010). This can clearly be observed within promotion of PES that commonly ‘constructs human behavior as determined by individual, material self-interest’ (McAfee and Shapiro Citation2010, 595) The World Bank, for instance, states, ‘Market-driven PES programs are more likely to be sustainable because they depend on the self-interest of the affected parties rather than on taxes, tariffs, philanthropy, or the whims of donors’ (McAfee and Shapiro Citation2010, 593).

The neoliberal biopolitics informing NCA is clearly apparent in this frame. As NCA becomes a concerted campaign to unite influential conservation actors and direct conservation policy throughout the world, it urgently demands further scrutiny. Some of this has already begun with respect to underlying assumptions (see Sullivan Citation2013, Citation2017a; Dempsey Citation2016), but how the NCA vision materializes via on-the-ground conservation practices – and how it is perceived and negotiated by the rural residents it targets – has yet to be systematically investigated. As one of the most prominent new processes influencing the lives of rural landholders around the globe, critical analysis of NCA is particularly important for peasant and agrarian studies. In the following, then, we explore two case studies in rural southeast Asia where NCA has been explicitly promoted as the rationale for renovated conservation interventions.

Defending natural capital

The following analysis draws on a comparison of empirical research from southern Palawan, the Philippines, and East Kalimantan, Indonesia, where key actors have increasingly emphasized the need to enlist rural residents as defenders of natural capital. The cases demonstrate a common process wherein domestic and international civil-society organizations seek to enroll poor farmers within projects informed by a neoliberal biopolitical logic. These projects have encouraged shifts from ‘traditional’ forest use and horticultural practices to more ‘value-added’ production involving performance-based incentives, such as payments for tree planting, rotating funds for sustained livestock production, and similar mechanisms that will ostensibly generate revenue by and for ecosystem services conservation. Both cases evidence a move from earlier integrated conservation and development projects (ICDPs) to newer NCA-based interventions that center on financially valuing a stock of resources as ‘natural capital’ and protecting this from loss or degradation.

Southern Palawan

Long considered the last ecological frontier in the Philippines, Palawan’s forests continue to host high levels of endemism and various indigenous populations (Eder and Fernandez Citation1996; see ). The main indigenous groups – the Tagbanua and Batak in Central Palawan and the Pala’wan in the south – continue to engage in shifting agriculture (i.e. swidden) in the mid to upper elevations of the island’s central mountain chain. The Pala’wan – the focus of this case – are an indigenous people of Malay descent and are largely ‘hunting-harvesting’: horticultural in focus, while diverse swidden practices still figure strongly in ritual, custom and livelihood. Increasingly, Pala’wan also engage in daily wage labor (arawan) in lowland paddy rice fields and, now, oil palm plantation and mining complexes in the same areas where NCA projects occur. Living in matrilocal household clusters that range in number between five and 50 households, the Pala’wan practice swidden by cutting down older forests, burning debris with hot flames, keeping land in fallow, and leaving other forest areas intact in line with local ritual and custom. Upland hamlets generally hold religious agents, belijan, and customary leaders, panglima, who serve as socio-cultural arbitrators and mediators in Pala’wan society. Today these community leaders, and notionally government-sanctioned ‘tribal’ datus or chiefs, have taken on a much stronger political role as brokers for politicians and NGOs pushing NCA.

The southern forests of Palawan have recently received focus as a global biodiversity hotspot while being subject to extractivism in the form of nickel mining and oil palm expansion. Both NCA governance and extractivism now overlap and encroach upon Pala’wan ancestral territory and old growth forest. Taken together, these perceived threats have driven NGO and state efforts to ‘safeguard’ biodiversity by working with indigenous uplanders to develop market-oriented NCA approaches to stabilize swidden farming in the uplands – a practice that, we show, has significantly reduced spaces for field rotations and fallow length, depletes soil and curtails regeneration, and displaces swidden practices into older forests (Anda Citation2015).

In central Palawan, especially, a complex network of NGOs, state representatives and bilateral agencies has facilitated an array of environmental governance initiatives since the late 1980s. Aligned with global conservation paradigms, these have ranged from more tangible ICDPs to speculative PES programs. Most of these interventions have worked through state- and municipal level-land-use programs, and were coordinated under indigenous tenure initiatives called Ancestral Domains Claims and Titles (CADC, CADTs; see IPRA, Citation1997). These compel indigenous communities to adopt Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development Management Plans that encourage uplanders to invest in fixed-plot, sedentary commercial agriculture. In these enclosures, swiddeners have been subject to intermittent monitoring and management through tree-planting initiatives, environmental-education stewardship programs, and major livelihood replacement programs (e.g. converting swiddens to tree crop, monocultures). Responses to these initiatives are mixed. Some resist, while others play along politically.

In the island’s southern reaches, we now see local NGOs, the regional chapters of Big International NGOs (BINGOs) (particularly Conservation International), and the World Bank, busily assessing the financial value of forests as stocks of natural capital, especially in the Mount Matalingahan Protected Landscape (MMPL). In 2008, Conservation International (CI), the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, the Department of Environmental and Natural Resources and others estimated the value of the broader environmental services of MMPL, including timber, soil, watershed dynamics and marine biodiversity, at over USD 5 billion in total. This was asserted to far exceed the economic value of mining (at roughly USD 3 billion) and other resource uses like upland agriculture. By using a ‘total economic value’ framework, CI and partners asserted that ‘at a 2% discount rate, the benefit from water for domestic agriculture and fishery was highest at P68.092 billion followed by the benefit from carbon sequestration, valued at P33,788 billion’.

WAVES

The World Bank’s WAVES initiative is also being rolled out across several countries including the Philippines. In these countries, the program seeks to introduce NCA in line with ‘internationally agreed standards … [and] other ecosystem service accounts’ (World Bank Citation2017b). The aim is to compile and scale up ‘accounts’ for natural resources such as forests, water and minerals in line with the UN’s System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA). Such national-level accounting will then be aggregated into a global-level assessment.

In 2013, consultations for the Philippine component of the program, Phil-WAVES, were carried out by state agencies and NGOs in southern Palawan that supposedly reflected the ‘status quo’ of alarming environmental degradation in the country (Fontanilla Citation2014). The program’s main objective was to ‘promote sustainable development through wealth accounting, the natural capital as its major determinant’ (1). In practice, this meant establishing ecosystem accounting for two areas in Southern Palawan to facilitate an analysis of trade-offs associated with different resources and ecosystem use scenarios. The year 2015 was particularly busy, with Technical Working Groups providing NCA workshops and training through database management and satellite and geographic information systems analysis. To date, several key ecosystem service accounts have been completed, including land and CO2 sequestration potential in upland areas occupied by Pala’wan farmers.

Building on CI’s earlier work, Phil-WAVES activities on Palawan have attempted to account for stocks of natural capital and their relative financial value in landscapes subject to mining and oil palm development. A recent ‘Pilot Ecosystem Account for Southern Palawan’ report (WAVES Citation2015) asserted that the forests of the MMPL had greater value standing than cleared by swidden farmers and extractive industries (e.g. mining and oil palm). In paradigmatic neoliberal biopolitical logic, the aim was to show upland Pala’wan farmers that a tree left standing was worth more than a tree felled.

Maracunan

While the WAVES program has yet to reach local farmers in any substantive way, its logic and practices extend out from CI’s longer-term NCA campaign in southern Palawan. Since 2009, CI has worked to offer indigenous uplanders various incentives to become forest stewards by having ‘over 300 families … sign conservation agreement[s] to agree to protect their natural assets, and learn the value of conservation’. They note that ‘the incentives for community members are plenty’ (CI Citation2017). In the small village cluster of Maracunan,Footnote1 CI established a Community Conservation Agreement (CCA) with the village’s Tribal Council. At about 800 m above sea level, the cluster of thatch houses is home to 12 large Pala’wan families (∼15–20 households, 80 individuals) who reside and subsist amid a patchwork of swidden fields, fallows and older forests. In this remote upland area, these families have relied heavily on unfettered access to their forest landscape, with swidden, non-timber forest products (NTFPs) harvesting, and daily wage labor being their main subsistence and cash income sources.

As the CI pamphlets explained, the CCA model promoted conservation strategies to address the opportunity costs of forgoing destructive resource uses, including the lost income otherwise generated from the conversion of forest to (swidden) agriculture. These CCAs were negotiated between CI and the Maracunan host community. As CI states,

The agreement specifies conservation actions to be undertaken by the resource users, and benefits that will be provided in return for those actions. The conservation actions to be undertaken by the resource users are designed in response to the threat to biodiversity. The benefits are structured to offset the opportunity cost of conservation incurred by the resource users. The types of benefits vary, but may include technical assistance, support for social services, employment in resource protection, or direct cash payments. (CI n.d., 1)

CI’s progress report indicates Maracunan was pre-selected because significant tracts of old growth forest were threatened there, stating that ‘kaingin (swidden) was deviating from the traditional practices … [and so] is a major threat to the remaining intact forest in the MMPL’s strict protection zones’. To counter this, ‘the tribal council agrees to specific conditions and actions to protect the forest in the area’. In support of this, farmers would become deputized as ‘community rangers [who] in coordination with the local peoples would monitor the area to ensure old growth forest and threatened species would not be cleared for swidden and harvested for consumption or sale, respectively’. In return, CI offered a long list of ‘co-benefits’ to encourage people to move toward sedentarized farming, including:

- The distribution of pigs and chickens;

- Construction of a tribal hall/learning center;

- One year of financial support of ‘para-teacher’ for non-formal education and support for school supplies;

- Technical and financial support to coconut planting, corn production and vegetable gardening by interested and capable members of the community;

- One-year incentives for community rangers for patrolling activities. This comprises 15 days of patrolling by two (2) persons @ ||Php 1,000.00 per month for one year;

- Establishment and year-round management of a nursery of indigenous species Reforestation activities of at least 10 hectares of denuded areas of Maracunan for one year. (CI n.d., 1)

To achieve the first few objectives, an environmental learning center (see ) was built, where Pala’wan were introduced to English and the importance of conserving forests by abandoning swidden. The center itself was equipped with a chalkboard, pictures of watersheds, and colorful forest animals for children.

The last objective of building a nursery for fruit and forest species reflected the most direct incentive structure: payments for planting various ‘high-value’ trees in former swidden fields. In planting the tree crops, CI assumed farmers would not return to clear and burn their fields again for fear of destroying the trees after a longer fallow period.

CI’s progress report for Maracunan (Citation2009–Citation2010), claimed that the program had been successful, concluding,

- based on the … experience, the conservation agreement scheme has proven effective in forms of foregoing [sic] destructive activities by directly addressing the socio-economic needs of the resource users.

- The communities have right away received and felt the benefits they identified, thus, they also adhered to the necessary conservation actions to protect the nearby old growth forest and rehabilitate damaged patches. (CA Progress Report Citation2009–Citation2010, 1)

In an interview, Pastor Manong Pilmar, the local Adult Learning Center (ALC) facilitator for CI’s ‘Environmental Literacy and Informal Education Program’, also claimed that the CCA program was achieving its objective:

Well, for almost two years of teaching them so far it is good and they like it, in our literacy program they already know how to write and to sign their signature, now in terms of environmental teachings, they have learned a lot that’s why as you can see it’s been two years now that there is no kaingin (swidden) here; they have really stopped [clearing the forest].

Well according to the Agreement between CI and the Tribe, this tribe here was initially given 1000 pesos monthly (USD 22 per person) and with that, they would guard the forest, they would act as forest rangers, and plant seedlings in kaingin … but this only happened a few times. Now there’s nothing. It was to be over a year.

Panglima Franco Bilog, CI’s ‘tribal broker’ and environmental advocate, states similarly,

Yes, right now there are people here who explain [to us] about Mt. Mantalingahan and that we should protect and preserve it; we are told to avoid making kaingin (swidden) in giba (old growth) so that the watershed will not be damaged.

So right now we just obey them … but I thought they would support us continuously so that we can have our source of income; if we have our daily income, we can have money to buy rice and it would not be hard on our part. But we are still waiting. Sometimes I think that it was much better before CI came. Before when we had kaingin it made us survive; if we don’t have kaingin I feel that we’ve lost everything.

We had big hopes, but now there’s nothing, doctor. That’s why we only get money if we plant fruit trees from the nursery, and if we can work for them we can get money; but if there’s no environmental work there’s no money, and we only eat cassava.

CI is the agency that helped us so that we will not cultivate the giba (old growth) and avoid its destruction. Because that’s their appeal – they don’t want many of us to open new giba for kaingin. But in this area, I’m not the [one] responsible for making kaingin. I also follow others to not open [forest for] new kaingin. But we were promised livestock and funds for forest protection but none of these came through. They promised the farmers money if we plant [trees] but until now nothing has happened.

Other farmers pointed out that among the trees they did plant since the CI project, it had become increasingly difficult to clear and burn in the same area. Diego Darmon notes,

Before the CI came here our livelihood was good, but when they came we lost livelihood. Before CI our livelihood was kaingin but when they came we couldn’t do it anymore. They prohibited us and we are told to guard the Mt Matalingahan including the virgin forest – they told us not to touch it.

But then they told us that if we plant seedlings in our kaingin we will get money. But we thought that if we plant the trees in date kaingin (older kaingin) we cannot go back there [in bunglay, secondary forest] … so we have problems because it is illegal to open new kaingin in giba (old growth). I told them [CI] that if we plant fruit trees in our bunglay (fallowed kaingin) … where will we do our kaingin now? And they said that we can use other bunglay, but we still cannot open a new one. When we only clear and stay in bunglay we cannot produce a good harvest … the soils become weaker (mahina ang lupa). So we have no choice … [but to open older forest].

When asked his opinion of the CI project and its tree-planting initiative, another farmer noted with ambivalence,

I can’t disagree and I cannot agree … we just follow along … I mean we received chickens, one lived the rest died because of a stomach infestation. So they say ‘If you don’t cut down the old forest, we will give you a chicken’. But we were also told to plant a lot of trees in our uma [newly cleared] fields. I was given 400 saplings and was supposed to be paid 4 pesos per tree. So we planted many of them in our fields but after a while we had to stop, and then planted all the trees in one area only! [outside of the uma] Our panglima suggested we do this … . He said that if we plant all these trees in every kaingin, in the future we won’t have any area for kaingin. So we really don’t have a choice but to open in giba (old growth).

Rather than embrace conservation per se, in sum, many farmers only temporarily engaged in such practices due to the partial, insufficient nature of payments and the fact that other livelihood priorities and concerns simply mattered more. This case shows that merely incentivizing behavioral change to facilitate forest stewardship amongst farmers who depend on clearing and burning forest for survival is fundamentally misaligned with local realities.

East Kalimantan

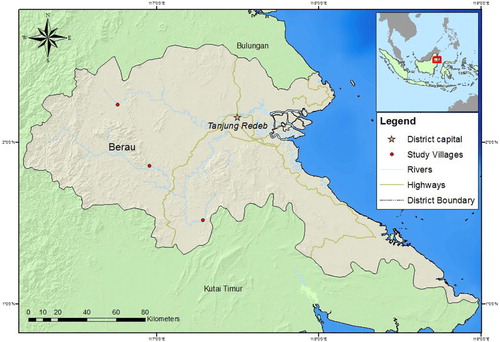

Like Palawan, the district of Berau in East Kalimantan has long been considered one of the last frontiers for resource extraction and environmental conservation in Indonesia. Despite a history of extensive logging and coal mining, Berau remains a critical area for biodiversity and ecosystem conservation, and one of the most forested regions in Kalimantan, with around 75 percent of the land area still covered by rainforest.

Until the late 1980s, Berau’s population was composed of local Malay and Buginese farmers and traders, town-based Indo-Chinese traders, indigenous Dayaks and nomadic Bajau communities (Obidzinski and Andrianto Citation2005). Beginning in the 1980s, however, the advent of government-sponsored transmigration programs brought about major social, economic and environmental change: thousands of people were brought to the region to relieve population pressures on Java and elsewhere, and, in the 1990s, to work on the growing timber plantations. Since the end of the Suharto Regime in 1998, the population has continued to grow, with most migrants working in forestry, plantation agricultural and mining. Upriver Dayak communities continue to rely on swidden and NTFP collection for sustenance and income, supplemented by a range of other wage labor opportunities. Traditional land-use practices are changing as plantations expand into the hinterlands and opportunities for employment or to sell land gradually emerge. The most drastic changes in Berau’s land cover have occurred since 2000 (Ekadinata et al. Citation2010), with oil palm cultivation rapidly replacing other land uses, particularly timber production. As of 2015, 32 location licenses had been issued for palm oil plantation development, covering almost 330,000 ha, with a loss of 24,000 ha of forest per year (Anderson et al. Citation2016). All of this has impacted Dayak livelihoods and the integrity of the forest (Vermaat, Estradivari and Becking Citation2012) ().

In part because of its location on the frontier of resource extraction in the province, Berau has been selected by international NGOs, donors and state agencies as a demonstration area for ICDPs aiming to integrate forest and species conservation with business-oriented programs. Under the banners of ‘green development’ and ‘sustainable forest management’, these interventions have primarily targeted the livelihoods and forest management practices of local communities, but also the extraction practices of local timber companies.

This began in 1996 with the European Commission-funded Berau Forest Management Project (BFMP), which brought more than EUR 14 million in funding to the district to support sustainable forest management (SFM) and conservation at the logging concession level. The BFMP began promoting the ‘model forest’ concept in 2000 as a means to engage local communities and account for a wider range of land uses in spatial planning. Since then, many projects have followed suit, seeking to manage Berau’s forest area in ways that protect biodiversity and support local development while allowing conventional large-scale resource extraction processes (chiefly palm oil and mining) to continue largely unabated. As a result, communities have found themselves negotiating between programs that support traditional livelihoods but offer limited tangible development opportunities, and the money offered by oil palm companies expanding into Berau’s remaining forests.

This sustained engagement between the government and people of Berau, local business interests, and the NGO and donor community has given rise to a network of organizations and projects that share a vision of eco-rational sustainable development in which continued economic growth is supported through the use of ‘extended cost–benefit analyses’ and an approach to community engagement and stakeholder participation based in neoliberal biopolitics. As in Palawan, this vision has most recently been articulated through projects grounded in the idea of ‘improving forest governance’ by assessing and defending natural capital. This defense of natural capital is premised on access to existing and new markets for ecosystem services, particularly carbon and water, and other ‘green’ sources of revenue such as ecotourism and NTFPs to support ‘low-emissions development’.

The natural capital of Berau’s Forest

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) has been the dominant non-governmental organization working in Berau’s terrestrial environmental governance complex since 2001, when TNC began working in Berau’s Kelay subdistrict with the goal of protecting the remaining population of orangutan and their old-growth forest habitat in the Lesan River Protected Forest (HLSL). Since this time, TNC has worked to frame local forests in terms of their natural capital value, and has positioned its interventions as a means of protecting this value. A 2002 study published by TNC, for example, concluded that the water and watershed services provided by two local rivers have an estimated value of more than USD 5.6 million/year (ESG International Citation2002), a valuation that has been taken up by UNEP’s TEEB initiative as a positive example of the economic dimensions of ecosystems services informing environmental decision-making (Hansjurgens et al. Citation2009). Simultaneously, local Dayak communities have been cast as stewards of natural capital, who, given the right incentives, can be helped to shift their livelihoods practices away from swidden farming to more modern, rational land uses and ‘value added’ production (e.g. ecotourism development).

TNC eventually expanded its vision and activities across the district by creating the Berau Forest Carbon Program (BFCP). Established in 2009, following the 13th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 13) in Bali and the emergence of the Indonesian National REDD+ Program, the BFCP is a district-scale REDD+ program and low-emission development project. It involves varied actors, including the District Government of Berau, the Provincial Government of East Kalimantan, NGOs including TNC, and donors, particularly the German Development Agency (GIZ) through its Forest and Climate Change Program (FORCLIME). The BFCP initially received around USD 50 million in funding (Hartanto et al. Citation2013).

Although the claim has proven contentious, GIZ FORCLIME identified the main driver of deforestation in Berau between 1990 and 2010 as shifting cultivation and smallholder agriculture (Navratil, Peterson, and Siegert Citation2012; Bellot Citation2015). Consequently, many of the NGO-led initiatives operating under the umbrella of the BFCP have focused on the use of incentive-based conditional agreements and ‘capacity building’ to influence local people’s activities, and limit the opening of new forest areas for swidden. In particular, TNC has developed a community engagement model called SIGAP-REDD+ (Communities Inspiring Action for Change in REDD+) with seven participatory stages of direct local engagement (Hartanto, Tomy, and Hidayat Citation2014). As a TNC Indonesia staff member explained, their approach ‘is called “inspiring action for change” because the staged process relies on the collective action of citizens to find strength, dreams and creative solutions to deal with their challenges, and strengthen their existence as communities that coexist with the forest’ (TNC Citation2014b). SIGAP-REDD+ is now being replicated in 23 villages across Berau.

While TNC’s village-based activities focus on other forms of value, including the ‘cultural or traditional values of forests to communities’ (TNC Citation2014a), the BFCP is centered on promotion of ‘green development’ and accounting for the economic value of natural capital – particularly carbon – as a means of making the ecosystem services provided by forests, watersheds and biodiversity visible to state actors in the face of rising extractivism. In this sense, REDD+ and the financial incentives associated with carbon markets must augment the value of natural capital sufficiently to outcompete these extractive activities in economic terms.

Complications

As the main proponent of the BFCP, TNC’s ‘non-confrontational, pragmatic, and market-based’ approach (TNC Citation2013) has been instrumental in shaping the form that environmental governance takes in the district, particularly as the Berau district government maintains ‘ownership’ of the BFCP. For that reason, the priorities and sensitivities of the local government have led to the concepts and intentions of BFCP being translated in ways that, at times, appear adversely related to the BFCP’s original goals.

For example, while the premise of the BFCP is that carbon finance through REDD+ can offset the costs associated with forgoing traditional economic development trajectories – almost all of which are linked to continued deforestation – there is rarely mention of the carbon market and carbon payments, and REDD+ is seen as a means of improving local management capacity and forest governance rather than as a means of creating saleable ecosystem service credits.

Moreover, while TNC identifies the main drivers of land-use change and deforestation in Berau as ‘[conversion of] land to oil palm and timber plantations, commercial logging, coal mining activities, [and] swidden-fallow agriculture’ (Fishbein and Lee Citation2015, 11), until recently mining and oil palm were not a focus of BFCP’s activities at all. Interviewees attributed this to uncertainty concerning how to engage with these industries, in that local government actors are heavily invested in both mining and oil palm as sources of economic development for the district, while permitting for these industries also serves as a major source of illicit kickbacks to support election campaigns. This has meant that the activities associated with the BFCP have disproportionately targeted local forest-dependent communities, particularly swidden farmers, as the main cause of deforestation and forest degradation, and thus of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Berau (despite longer fallow swidden systems being substantial carbon sinks; Dressler et al. Citation2016).

The BFCP thus partially rests on a form of neoliberal biopolitics that aims to combine a disciplinary focus on the establishment of environmental subjectivities with creation of external market incentives. Yet as in Palawan, while the program’s vision is decidedly of a neoliberal biopolitical nature, the implementation and outcomes are clearly only partially ‘eco-rational’, even by their own standards, and not durable in the face of oil palm plantation expansion. To understand the significance of this approach and how it is rearticulated locally, we now examine the local situation in a ‘model’ village demonstrating REDD+ in practice.

Gunung Madu

Gunung Madu is located in a lowland forest area in Berau’s Kelay subdistrict at the foot of the Mangkalihat-Sangkulirang Karst mountains. The majority of Gunung Madu’s 56 households are ethnically Dayak Lebo, although there is also a significant population of migrants who have married into the village – mostly Banjar and Dayak Kenyah from elsewhere in East Kalimantan, Buginese from Sulawesi, and first- or second-generation Javanese transmigrants. All villagers recognize adat, a loose term defining a body of customary norms, laws, ceremonies and ritual, grounded in animistic beliefs, which govern many aspects of resource use and access, agriculture and the demarcation of different types of land.

Gunung Madu’s forest area is divided between a production forest of 11,300 ha, managed by the PT Utama Damai Indah Timber, and the Gunung Madu protected forest (itself part of the larger 65,500-ha Pegunungan Menyapa protected forest). With TNC’s support, in 2015 Gunung Madu was granted 35-year management authority over this 8245-ha community forest (hutan desa), which allows the community to manage and utilize the village forest for the collection of NTFPs, ecotourism development, and other minimally impactful activities, as the area’s ‘protected’ statues requires that they manage it ‘sustainably’ and prevent it from being converted to other land uses (like coal mining). Villagers rely on the forest for a range of resources, including game and NTFPs, and practice swidden agriculture within the forest area to produce rice for subsistence. Additionally, villagers cultivate fruit and vegetables in home and agroforestry gardens. Waged labor outside of the village has increased over the last few decades, particularly in nearby timber concessions, oil palm plantations or in the coalmines. The village has also received National Community Development Funding (PNPM).

TNC has developed a relationship with Gunung Madu since 2008, although activities grew after the establishment of the BFCP in 2010. Beginning in 2012, TNC started supporting Gunung Madu in their pursuit of community forest management certification, acting as an advisor to the village and a broker between the village leaders, the local and provincial governments and the national-level Ministry of Forestry.Footnote2 In late 2013, the government of Gunung Madu signed an agreement with TNC ratifying their participation in the BFCP and their commitment to protecting the forest and promoting environmentally friendly livelihood activities.

In Gunung Madu, the BFCP relies on influential community members and community-based TNC facilitators to act as brokers between villagers (as in Palawan), external NGOs and various government agencies. This relationship was formalized with the creation of a local forest management organization, Kehutan Inda, through which BFCP activities are implemented. The governance mechanisms deployed within the BFCP are as follows: Gunung Madu’s ratification of the BFCP is tied to a three-year performance-based conditional payment agreement, under which TNC agrees to provide support for conservation and alternative livelihood programs in exchange for villagers carrying out a range of activities meant to reduce deforestation and forest degradation, and thereby decrease GHG emissions. Like the CCA governing CI’s relationship with Maracunan, Gunung Madu’s conditional payment agreement is intended to address the opportunity costs of forgoing more lucrative forms of land use, such as oil palm cultivation, and provides incentives for shifting villagers away from swidden farming practices. The agreement also lays the groundwork for the creation of village-owned alternative business enterprises, such as honey collecting and ecotourism, based on the idea that markets for these commodities will emerge as the village’s own capacity develops.

This agreement also requires that the community create a land-use plan that limits the number, size and location of swidden plots, and mandates that community members participate in training, and conduct forest patrols and mapping activities. Adherence to the conditional agreement is evaluated each year against a previously agreed-upon scoring system, and if targets are not met the village may be sanctioned and face decreased financial support in the future. So far, this financial support amounts to around USD 20,000 per year, although much of this is given in the form of support for forest patrols and management, rubber cultivation, fish, duck and chicken farming, vegetable gardening, honey production, capacity building and more.

Interviews with villagers show that throughout the duration of the project, families tended to participate but also continued to pursue well-established livelihood practices, while maintaining clear, direct aspirations for enhanced ‘material well-being’ – aspirations that they would soon realize TNC could not deliver via NCA.

The fallout

More than two years have passed since the original conditional agreement was signed in Gunung Madu, yet despite TNC’s efforts to cultivate a participatory process of decision making and engagement between the households and the activities of the BFCP, a rift has opened in the community, with some members questioning the benefits associated with the BFCP, the community forest, and TNC’s activities in the village. Some of the activities associated with the BFCP have failed or experienced setbacks, particularly the alternative livelihood activities, and some villagers feel that the benefits of the BFCP are disproportionately enjoyed by a small group of villagers. As one villager said,

TNC gives us chickens, duck and fish, but the fish all died and the ducks got sick. Now the government is supporting us with cattle, but you have to be part the of the headman’s group to take advantage of these programs; I don’t have a cow! They do give us rubber seedlings, but it takes a long time for the trees to be ready to harvest, and for now we don’t have access to a market – the price of rubber has also fallen! I have three children in school, with one in SMP (middle school) and one already in SMA (high school). I have to pay for their housing and food since we do not have an SMP or SMA closer to our village. Where should this money come from?

There are no tourists visiting my house to stay or eat, only those of the people who are already part of the group; working with the organization [Kehutan Indah]. If tourists come it’s fine, but we are private people, we don’t want people we don’t know coming inside our houses unexpectedly, or walking around where they shouldn’t be. We just want to work in the ladang, go to the forest [to hunt and collect fruit and rattan], and be able to take care of our children and parents. If we organize well we can make a good deal with the [oil palm] company that will benefit everyone in the village, rather than just a few.

Oil palm does not have to be a threat if we are careful and do it the right way. Some of us have an idea of creating a group to negotiate with the [oil palm] company and then growing oil palm ourselves, in small areas. That way we can protect the forest and still receive the benefits from the company. In reality, if we are talking about the future, I think this will be necessary. I support the BFCP and work with Kehutan Inda, but if we want the village to develop we will have to do something … I still plant ladang the way my father did. I still go to the forest [to hunt and collect NTFPs], but things are different now – there are more things that we need money for, and what we take from the forest is no longer enough. Our children want the things that their friends have – phones, TVs, motorbikes – otherwise they will be left behind.

One way in which this conflict is visible is in the land-claiming practices taking place in the village. As part of Gunung Madu’s village land-use plan, on which the conditional payment agreement is based, the land along a road to the southwest of the village was set aside as ‘reserve land’ for future generations. However, when TNC conducted the first-year evaluation of the conditional payment agreement in March 2015, villagers admitted that four households had engaged in land clearing for swidden along this road. Because violations of the land-use plan affect the amount of funding provided to the village in the following year this violation had the capacity to impact all villagers. The participatory evaluation eventually found that the village met 85 percent of their commitments (and thus would continue to receive full support in the following year), yet during the discussion a number of interesting justifications for the land clearing emerged.

One of the most common justifications offered was that community members had opened the reserve land in an effort to protect the village from encroachment by outsiders. As oil palm plantations have expanded in a neighboring village area, residents from that village have challenged the demarcation of Gunung Madu’s boundaries and attempted to assert control over areas that Gunung Madu claims. This has resulted in moments of tension, including the confiscation of a bulldozer owned by the plantation company that was found clearing land in the forest area under debate. Thus, a number of villagers suggest that people only open new forest areas for swidden where border conflicts with other communities exist.

At the same time, some community members suggest that some of those opening land question the ability of the BFCP to generate tangible benefits for the village or feel that they have not gotten a fair share of the benefits already generated. It is suggested that these villagers are opening swidden along the border in order to position themselves to receive compensation if/when oil palm expands into the village area, rather than out of a concern for the territorial integrity of the village. They are thus claiming land as a form of private speculation or ‘territorial banking’ (Thaler and Anandi Citation2017) in advance of the expansion of the neighboring plantation. As one village elder mentioned,

The people opening land along the border are protecting our village and preventing them [neighboring villagers] from taking our land. But we do not disagree with the idea of oil palm entering our village. We all want to protect the forest – our lives are tied to the forest, as Dayaks the forest is part of us – but we also need development. We need better roads and schools for our children, we need better access to health care, and enough food to eat. We have the idea of growing oil palm ourselves in smaller plots and forming an oil palm growers’ [co-op] group. That way we can access the benefits of oil palm while still protecting the forest and our way of life in the village.

When representatives of the NGOs working in Berau or the local government are asked whether the BFCP has been successful in Gunung Madu the answer is a resounding ‘yes’, a perception demonstrated by the fact that Gunung Madu was chosen as the showcase of successful REDD+ implementation during a February 2016 visit by Norway’s climate and environment minister. The village guestbook filled with foreign names is often shown to illustrate the success of ecotourism, and TNC’s literature recounts the successes linked to the BFCP and REDD+ implementation in Gunung Madu (Hartanto, Tomy, and Hidayat Citation2014): the participatory construction of a three-dimensional map of the village which taught villagers young and old about different ways of understanding the village space; and the increase in government funding to support village development activities tied to TNC’s assistance in the creation of a Village Medium Term Development Plan.

But in private this ‘success’ is tempered by anxiety about the future and a recognition of the precariousness of Gunung Madu’s position in a political climate that favors oil palm as the primary development strategy. As one TNC staffer asked,

What do you think of our activities in the villages? Because I’m worried to be honest. I’m afraid that oil palm will enter Gunung Madu [after more than half a decade working in the village]. We have a better relationship with the government now, but the government still supports oil palm as the way towards development … . We know that if we can demonstrate improved forest governance and land use at the village level then the government will pay attention and work with us, but I don’t know if that is enough to provide development to the village. It may be short-sighted, but you can’t blame people for wanting development.

In practice, it seems that apart from grandiose rhetoric little sets the BFCP apart from the history of previous ICDPs, with NGOs and donors scrambling to fulfill both development and conservation objectives. Yet discursively and materially the BFCP, and the coalition of actors and organizations that has formed around it, represents a distinct moment in the history of conservation in which conservation action is founded on the promise of future markets. While the story of communities and government actors negotiating between better paying but more destructive resource extraction, and less lucrative but more sustainable forms of development and conservation, is not new, it is worth asking what the uncertainty of the (future) market and the shadow of unmet expectations add to this equation. One thing that is certain is that without the emergence of a global carbon market, funding for the BFCP, in its current form at least, will not last indefinitely.

The cruel optimism of defending natural capital

A pattern emerges when comparing Palawan and Berau: a cruel optimism (Berlant Citation2010) offered to local community members tasked with being the defenders of natural capital while at the same time being prohibited from practicing livelihoods strategies that they have engaged in for centuries. But this cruel optimism extends beyond the villages, and is not merely a case of NGO workers taking advantage of villagers in order to implement a project with the veneer of success. Local NGO workers also find themselves caught in the vise of pragmatism and an economy of expectations (Borup et al. Citation2006), hoping for more but accepting less in the interest of making small steps toward protecting the forest and supporting communities. Local representatives of BINGOs, meanwhile, find themselves shaped by the structural constraints of environmental governance in situ just as local community members do, with both groups giving, receiving and buying into a range of speculative, future-oriented promises that seldom come to fruition.

Interventions in both areas include a PES scheme (a provincial project in Palawan, a national REDD+ program in East Kalimantan) established with support from NGOs, the state and bilateral donors. What is remarkably consistent across the cases is the speculative anticipatory ‘end objective’ that NGOs promote to recruit local stakeholders (upland farmers in Palawan, district and state officials in East Kalimantan) with the seductive promise of new (financial) capital derived from the (natural) capital they supposedly already possess. In order to realize these benefits, farmers must change their behaviors and attitudes toward themselves, livelihoods and forest landscapes in ways that, we contend, exemplify a particularly neoliberal biopolitics promising ‘green growth’ as an incentive for this shift. In this way, swidden farmers are turned into forest stewards, honey hunters become centerfold sustainable harvesters and, in time, both forest stewards and sustainable harvesters become ‘showpieces’ for local forest conservation initiatives – exemplary warriors in defense of natural capital.

In contrast to their common framing by conservationists, however, local people tend to be more realistic and opportunistic brokers than selfless ecological stewards. While they negotiate and enact their role as stewards and representations of NGO-led programs, they also deftly negotiate the socio-political networks of extractive capital in search of the most lucrative prospects. In so doing, they keep opportunities open for involvement in either endeavor by simply not closing these off.

In some cases, locals will themselves refuse extractive industry in defense of natural capital – but usually only insofar as NGOs continue to invest time, labor, capital and rhetoric in creating the anticipatory atmosphere of valuable opportunities to be realized in the future. But when these NGOs, along with state agents engaged in ‘public–private partnerships’, abandon these ventures, as they often do, communities may splinter, with some availing themselves of the opportunities they have kept open for employment in extractive activities such as oil palm.

In other cases, such as Palawan, community members feel abandoned and desperate with respect to the intangible aspects of NGO promises and return to what they have always done: clear old growth forest for productive swidden yields so as to feed their families. In other instances, they maintain plots and forest harvests as they shift labor time to work in plantations that flank the forest uplands. In this way, NGOs often inadvertently leave a legacy of frustration alongside the lingering notion of the continued necessity to improve oneself in pursuit of a chimerical development (Li Citation2007).

Conclusion

Our analysis has explored how natural capital valuation in the interest of biodiversity conservation has been promoted in similar ways in two sites in Southeast Asia. A common pattern emerged in which this promotion is intended to (directly or indirectly) enroll local resource users as defenders of natural capital in exchange for the promise of payments to make this defense more profitable than the extractive opportunities forgone in the process. We have proposed that this exhibits a form of neoliberal biopower in terms of which the imperative to ‘make live’ is justified by both the role of biodiversity in sustaining life and the need to incentivize defense of natural capital through demonstrating the economic potential in harnessing capitalist markets as the basis of conservation payments. ‘Green growth’ becomes the common metaphor for this logic, shorthand for the particular manner in which life is to be nurtured within a neoliberal biopolitical perspective. NCA is thus not merely a new version of a longstanding ICDP approach; rather, it espouses a new, overarching set of technologies, conditionalities and incentive structures hitherto foreign to rural frontier spaces (Büscher, Dressler, and Fletcher Citation2014; Turnhout, Neves, and de Lijster Citation2014). For this reason it is crucially important that peasant and agrarian change scholars attend to the implications of this trend for rural livelihoods.

While we our cases demonstrate that the ideal neoliberal vision informing NCA is rarely if ever wholly realized in practice, its biopolitics clearly does circulate discursively and manifest materially, if only partially, in its influence on local (self-)perceptions and land use in the short term. Despite their limited success in improving conservation outcomes, moreover, NCA initiatives remain lucrative for some in funding program design and project delivery, infrastructure development, accounting and monitoring activities and so forth. Yet in the long term, the common misalignment between NCA interventions and local needs will likely merely precipitate intensification and degradation of frontier landscapes. As our cases demonstrate, most NCA interventions do not satisfy the benefit–cost ‘calculations’ of rural residents as these newer interventions are simply not tangible and lucrative enough to stop poor farmers, who simply want a better future, from entering into extractive ventures.

While our analysis includes only two specific cases, anecdotal evidence from other sites suggests that the common dynamics we have identified are not limited to these. These are, we propose, inherent within NCA, which embodies an essential tension between the economic valuation it promotes and its persistent inability to actually generate the financial resources necessary to direct this valuation toward conservation. This is, quite simply, because resource extraction is almost always far more lucrative than conservation, which results from the fact that this extraction is able to externalize social and environmental costs in order to increase profits (Fletcher et al. Citation2016). NCA, of course, is intended precisely to encourage the internalization of such costs in acknowledgment of this dynamic. Yet its market-based emphasis means that to do so entails eschewing the possibility of direct regulation in favor of the effort to generate more revenue from conservation than extraction in order to incentivize the former. Yet to accomplish this on a substantial scale is essentially impossible within neoliberal capitalist economies whose boundaries this strategy takes as given. To generate the profits necessary for this strategy to work would paradoxically require externalizing even more social and environmental costs elsewhere to generate the revenue needed for conservation offsets (Fletcher et al. Citation2016).

The fact that these daunting issues are rarely addressed in conservation planning is not necessarily a function of neglect or miscalculation on the part of planners. Our research demonstrates that such avoidance seems to stem not from naiveté but more commonly from a sense of paralysis in the face of overwhelming structural challenges. To really stop extractive expansion would be to call for a fundamental transformation in how both states and markets operate within a capitalist political economy predicated on continual expansion. Efforts to advance a conservation strategy that acknowledges this reality are underway (Kothari Citation2014; Büscher and Fletcher forthcoming). Short of that, the choice to use NCA initiatives and focus on local communities in order to try to protect some small piece of biodiversity is a pragmatic one.

NCA for conservation, in sum, seems plagued by a fundamental contradiction in terms of its overarching aim to promote cost–benefit analysis in pursuit of conservation. In practice, as we have shown, rather than producing the promised symbiosis the former actually tends to undermine the latter, encouraging valuation based on economic logic yet in failing to provide sufficient revenue from conserved resources ensures that the cost–benefit equation will be resolved in favor of the very resource extraction it intends to counter. In this way, a neoliberal biopolitics is promoted even as it fails to defend the ‘natural capital’ it targets.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper was presented at a panel on ‘Violent Neoliberal Environments: The Political Ecology of “Green Wars”’ organized for the conference ‘Political Ecologies of Conflict, Capitalism and Contestation (PE-3C)’ at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, 7–9 July 2016. We would like to thank the other panel participants for valuable feedback in developing the current version, as well as three anonymous reviewers at JPS whose insightful evaluations pushed us further on various aspects of the analysis. Research in Palawan and Indonesia was funded by Dressler's ARC Future Fellowship (FT130100950). Research in East Kalimantan was carried out with support from the University of Toronto School of Graduate Studies, the Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship and the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). We also thank the indigenous people of southern Palawan and Berau for supporting our work. This paper is for them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Robert Fletcher is an associate professor in the Sociology of Development and Change group at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. His research interests include conservation, development, tourism, climate change, globalization, and resistance and social movements. He is the author of Romancing the wild: cultural dimensions of ecotourism (Duke University, 2014) and co-editor of NatureTM Inc.: environmental conservation in the neoliberal age (University of Arizona, 2014).

Wolfram H. Dressler is an associate professor in the School of Geography at the University of Melbourne, Australia. His longstanding research interest concerns social justice and agrarian politics in the Philippines and Indonesia. He works with and for indigenous peoples’ self-determination.

Zachary R. Anderson is a PhD candidate in the Department of Geography and Planning at the University of Toronto and a graduate fellow with University of Toronto’s Centre for Critical Development Studies. His doctoral research investigates the emergence of the ‘green economy’ in Indonesia through a case study of ‘green growth’ in the province of East Kalimantan.

Bram Büscher is a professor and Chair of the Sociology of Development and Change group at Wageningen University, The Netherlands, and holds visiting positions at the University of Johannesburg and Stellenbosch University. He has published over 70 articles in peer-reviewed journals and edited volumes, and is the author of Transforming the frontier. Peace parks and the politics of neoliberal conservation in Southern Africa (Duke University Press, 2013). He is currently finalizing a book manuscript entitled ‘Sharing nature? Conserving biodiversity between platforms, post-truth and power.

Notes

1 A pseudonym.

2 Now the Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

3 From TNC currently. The World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Fund (FCPF) recently selected East Kalimantan as its area of focus in Indonesia, with around USD 50 million being earmarked for Berau, so there is a possibility that payments for verifiable emissions reductions may be forthcoming after 2024.

4 At the Green Growth Compact launch in Jakarta on 26 September 2016.

References

- Agrawal, A. 2005. “Environmentality: Community, Intimate Government, and the Making of Environmental Subjects in Kumaon, India.” Current Anthropology 46 (2): 161–190. doi: 10.1086/427122

- Anda, R. D. 2015. “Summer not all beach in Palawan; it is the season to burn forests.” Inquirer.net, April 9. Accessed 17 August 2017. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/684378/summer-not-all-beach-in-palawan-it-is-the-season-to-burn-forests#ixzz53xaRqc1O.

- Anderson, Z. R., K. Kusters, J. McCarthy, and K. Obidzinski. 2016. “Green Growth Rhetoric Versus Reality: Insights from Indonesia.” Global Environmental Change 38: 30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.02.008

- Bellot, F.-F. 2015. Drivers of Deforestation: Global, National, and Local Scale. Jakarta: GIZ FORCLIME.

- Berlant, L. 2010. “Cruel Optimism.” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 17 (5): 20–36.

- Biermann, C., and B. Mansfield. 2014. “Biodiversity, Purity, and Death.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32: 257–273. doi: 10.1068/d13047p

- Borup, M., N. Brown, K. Konrad, and H. Van Lente. 2006. “The Sociology of Expectations in Science and Technology.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 18: 285–298. doi: 10.1080/09537320600777002

- Büscher, B. 2013. “Nature on the Move: The Value and Circulation of Liquid Nature and the Emergence of Fictitious Conservation.” New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 6 (1/2): 20–36.

- Büscher, B., W. Dressler, and R. Fletcher, eds. 2014. NatureTM Inc.: Environmental Conservation in the Neoliberal Age. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

- Büscher, B., and R. Fletcher. 2015. “Accumulation by Conservation.” New Political Economy 20 (2): 273–298. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2014.923824

- Büscher, B., and R. Fletcher. Forthcoming. Towards Convivial Conservation: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature Beyond the Capitolocene. London: Verso.

- Büscher, B., S. Sullivan, K. Neves, J. Igoe, and D. Brockington. 2012. “Towards a Synthesized Critique of Neoliberal Biodiversity Conservation.” Capitalism, Nature Socialism 23 (2): 4–30. doi: 10.1080/10455752.2012.674149