ABSTRACT

This contribution looks at the interplay of different logics of governing the environment, resources and people in Cambodia that materialise in overlapping zones of exclusion, thereby co-producing new relations of resource control in a complex frontier constellation: a frontier for water, forest and carbon commodities and also for state control. Focusing on three Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) hydropower dams, the paper analyses a partly unintentional, but significantly consequential coalescence of distinct spaces of governing located in the Cardamom Mountains: a forest conservation zone, the CDM technological zone, an enclaved corporate hydropower zone and a semi-official timber logging zone. While the CDM element has exposed the projects internationally, it has obscured several problematic aspects and dynamics of resource politics connected to the dams that are revealed in this paper. These include the vulnerabilisation of local fisher communities, incarceral labour practices on the dams’ construction sites and accelerated logging in the conservation zone. The paper also shows how the interaction of the studied zones takes place through their distinct mechanisms of exclusion with the effects of more centralised resource control and the bracketing of the associated dispossessions.

1. Introduction

This contribution analyses the interplay of the differing logics of resource control that shapes dynamics in a complex frontier constellation and produces spaces of governing that intersect with each other in consequential ways. The focus is on three Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) hydropower dams in Cambodia – Atay, Tatay and Russei Chrum – which have been developed by Chinese companies under concessionary arrangements. These are among the most significant foreign direct investments in the country (1.3 billion USD in total) and comprise fenced enclaves with a high rate of corporate regulatory autonomy. They are located in the Cardamom Mountains in south-west Cambodia, next to the border with Thailand, within one of the largest remaining forest areas in mainland South-east Asia.

The Cardamom Mountains are an example of a resource-rich site, attracting actors operating on various scales and with interests ranging from resource extraction to conservation. The different ends and means of resource control (Peluso and Lund Citation2011) present in the area also overlap and interact with each other in important ways, something that is becoming more of a norm than an exception in the remaining resource-rich areas of South-east Asia (Eilenberg Citation2014), and even globally. As these entanglements cannot be fully grasped through the more conventional project-by-project or ‘sectoral’ approaches, new analytical lenses and conceptualisations developed in close connection to empirical realities are required (Baird and Barney Citation2017; Hunsberger et al. Citation2017). Our study aims to contribute to this task.

To make sense of the observed, complex dynamics in the Cardamoms we developed a novel approach, conceptualising the interconnections between different resource control schemes as overlaps in zones of exclusion. In our study these include: (1) a conservation zone co-governed by international conservation organisations and national authorities; (2) a technological CDM zone of global climate governance; (3) enclavistic Chinese corporate hydropower zones; and (4) mobile, semi-official logging zones. They share common features in that they are non-contiguous spaces of governing and regulation constituted by regimes of exclusion. Yet they are also heterogeneous not only in their aims and means but because they include both territorially fixed spaces (conservation, hydropower and logging zones) and non-territorial regulatory spaces formed by technical practices (CDM zones). We examine their operations and governing logics, how they relate to each other and with what effects, bringing forth the interaction of different resource control schemes that often remain invisible but nevertheless may be consequential. This in turn contributes new perspectives to discussions on the frontiers as sites of co-production of resources and states (Bridge Citation2014; Eilenberg Citation2014; Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018) and connects these discussions to the studies of enclaved spaces of governing (Ong Citation2006).

Analysis of the study’s CDM element casts light on how climate governance initiatives may become intertwined with on-the-ground resource politics, something continuously overlooked in the climate domain (Käkönen et al. Citation2014; Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015; Leach and Scoones Citation2015). It also opens up the politics of commodity production – the socio-ecological and labour relations – that are hidden by the end product of certified emissions reductions (Milne Citation2012; Peluso Citation2012). Furthermore, problematic aspects and adverse outcomes of the CDM hydropower dams, such as the vulnerabilisation of fisher communities, incarceral labour practices and accelerated logging in the conservation zone, are revealed, none of which are visible in the CDM documents, the only official publicly available records connected with the projects.

Primary research data are drawn from relevant policy and project documents, newspaper articles and fieldwork carried out mainly in March 2013 and February/March 2014. The informants of the 23 thematic interviews included relevant ministry officials (especially those with connections to the CDM projects) and journalists as well as non-governmental organisation (NGO) staff and activists engaged in conservation and human rights. Some of the interviewees from the ministries we interviewed for the first time in 2011. Most of these interviews were carried out in Phnom Penh and Khemara Phoumin, the capital of Koh Kong province. Despite concerted efforts we could not gain interview access to representatives of the hydropower companies. During the two and half months of fieldwork around eight days were spent in villages. The community-level group discussions with villagers and interviews with local ex-workers in dam construction and village chiefs (38 interviewees in total) were carried out in two communes in the province of Koh Kong where most of the dams’ downstream impacts are experienced: Bak Khlang downstream from the Atay and Russei Chrum Dams, and Tatai Kraom downstream from the Tatay Dam. Around half of these discussions were carried out by Try Thuon (second author) in Khmer and the rest by Mira Käkönen (first author) via a translator.Footnote1

We begin by explaining and contextualising key conceptualisations. We then outline the history of Cardamom’s resource frontier closure by conservation schemes and later partial reopening for extractive hydropower dams, including discussion of their concessionary governing mode. Thereafter we demonstrate how the technological zones (Barry Citation2006) of the CDM and environmental impact assessments (EIAs) have bracketed the dispossessions produced by the dams. We go on to show that the exclusivity and legal exceptionality of the corporate hydropower enclaves enable and shield exploitative labour practices; then, aligning with and building on Milne’s (Citation2015) findings, we discuss how hydropower projects together with the control mechanisms established for conservation purposes interact with exclusive zones of logging. We conclude by underlining the co-constitutive elements of the overlapping zones of exclusion, bringing forth how resource extraction and power relationships are co-produced in complex frontier constellations.

2. Frontier constellations and zones of exclusion in Cambodia

The past decades of changes in the Mekong countries like Cambodia have been mostly viewed through the lens of transitioning from battlefield to marketplace (Glassman Citation2010), bringing into focus how the years of civil war, insurgencies and Cold War legacies kept Cambodia largely disconnected from transnational circuits of capital and how shifting from a command economy to freer markets since the 1990s has been influenced by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund doctrines of investor-friendly regulations. As Dwyer (Citation2011) has noted in the case of Laos, however, both sides of the equation are important: the ‘marketplace’ for opening up resources for wealth accumulation, and the ‘battlefield’ for consolidating fragmented sovereign powers and territorial state control (Lund Citation2011). In Foucauldian terms two differing, yet interacting, governing rationalities are present – the securing of global circulation and territorial fixation (Foucault Citation2007, Citation2008). The latter can be understood to include both the rationale of fixating state sovereign territorial authority and its exclusivity, and the strengthening of the state capacities to control resources and people within this territory. The liberal rationale of securing global circulation, in contrast, includes the establishment of ‘conditions for the organization of world market’ (Foucault Citation2008, 56) and thus enabling of the globalising operations of capital.Footnote2 Both rationalities are part of shaping the resource-rich Cambodian ‘hinterlands’ that form complex frontier sites at the edge of both the global capitalistic economy and state rule. Frontiers have long been regarded either from the perspective of expanding capitalism and logics of accumulation (Hall Citation2012) or as political borderlands at the margins of state control (Hagmann and Korf Citation2012). More recently Eilenberg (Citation2014) has developed the concept ‘frontier constellations’ to capture the concurrence of expansions in agrarian capitalism and state authority in the resource-rich borderlands of South-east Asia. This conceptualisation opens up possibilities to account for the concomitance and often co-constitutive relations between resource-making for the circuits and advances of global capital, and state-making in terms of forming, consolidating and territorialising state powers (Bridge Citation2014; Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018). It also allows analysis of how the economic rationale of profit making and the political rationale of strengthening state powers become entangled and form relations of mutual co-dependence (e.g. Emel, Huber, and Makene Citation2011). We contribute to these discussions by studying a complex configuration of different possible frontier constellations: a frontier for water, forest and carbon commodities as well as for political control and state power consolidation.

We examine the frontier dynamics in the Cardamom Mountains via the interaction of differing logics of resource control – that is, as effects of multiple determinations ‘shaped by interacting global forms and situated political regimes’ and irreducible to a singular logic (Ong Citation2007, 8). The more ‘global forms’ of governing logics to be discussed are mainly related to the securing of global circulation in the form of neoliberal logics, shaping how the environment is used both as a ‘tap’ (source of raw materials) and as a ‘sink’ (space of pollution) (Moore Citation2015; Barney Citation2017). In addition, there is a preservationist logic (Biermann and Mansfield Citation2014) present in the form of furthering protected areas as promoted by international conservation organisations.Footnote3 Cambodia’s provision of a tap for regional and global markets has been guided by neoliberal prescriptions of creating investor-friendly environments (Hughes Citation2009; Springer Citation2011); meanwhile, the new ‘economy of repair’ (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2012) provides opportunities to use the spaces of pollution as bases of wealth accumulation. This takes place through neoliberalised environmental governance wherein direct regulation is significantly replaced by market-based solutions and the creation of new environmental commodities (Bakker Citation2005), which, in the case of carbon markets and the CDM, imply the intention of monetary valuation of the entire carbon cycle, although effectively only selected carbon dynamics are accounted for (Bäckstrand and Lövbrand Citation2006, Lohmann Citation2008).

The resource-governing logics of the ‘situated political regime’ in Cambodia are mainly authoritarianFootnote4 – governing through fear and sovereign rule of force – and neo-patrimonial, or reliant on networks of loyalty and reciprocal favours (Un and So Citation2009; Cock Citation2010; Hughes and Un Citation2011; Springer Citation2011; Biddulph Citation2014). The capacity of the Cambodian state to act from a distance is built around reciprocal exchange of political loyalty and access to key resources, the centralising of which has provided the current ruling party, the Cambodia People’s Party (CPP), with its sovereign powers (Le Billon Citation2002; Hughes Citation2009; Hughes and Un Citation2011; Milne Citation2015). Timber rents in particular have been used to consolidate control over the ex-Khmer Rouge, the military, provincial strongmen and business tycoons (Le Billon Citation2002; Hughes and Un Citation2011). Donor dependency has meant that intensive resource exploitation shaped by patronage logics often remains a hidden transcript (Scott Citation1990) in resource governance, while more public policy documents and strategic development plans are aligned with donor expectations of good governance and sustainability promotion (Le Billon Citation2000; Hughes Citation2009, 156–65). Neo-patrimonial and neoliberal logics, although often perceived as conflicting, have in the Cambodian case interacted in mutually supportive ways: patronage arrangements have produced the stability that is a precondition for ‘investor friendliness’ (Hughes and Un Citation2011). These arrangements have provided the regime with coercive powers that are often crucial in creating resource availability for large-scale corporate investments (see Levien Citation2012).

The current concession-based approach of promoting economic growth in Cambodia can thus be seen as a co-produced assemblage (Collier and Ong Citation2005) of neoliberal, authoritarian and neo-patrimonial logics with colonial legacies (Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014). International development banks have pressured Cambodia to make its legal system more investor friendly and World Trade Organization compliant, resulting in the 2001 Land Law that created a category of ‘state private land’ that is ‘alienable’ and available for concessionaires (Dwyer Citation2015); currently more than two million hectares are covered by economic land concessions, equalling over one-third of the country’s agricultural land (Davis et al. Citation2015). Investment friendliness also materialises in the establishment of Special Economic Zones (SEZs), with 30 currently approved (Open Development Cambodia Citation2015). Most concessions are in the hands of foreign investors (mainly Chinese and Vietnamese) but almost half of them are under okhnas – local tycoons with well-established and formalised connections to the CPP elite – and operationalisation of both has often required authoritarian decisions and violent displacements (Springer Citation2011; Licadho Citation2014). Of particular interest for our study is the way this concession-based development model materialises in a ‘chequered geography’ of non-contiguous zones of governing, a territorial fragmentation that partly undermines but also exerts and extends state power through a kind of variegated sovereignty (Ong Citation2006). Unlike the high-tech zones in Ong’s focus, many Cambodian zones are agro-industrial (rubber and sugarcane) and extractive concessions (mining and hydropower). These tend to be enclaved as distinct territorial zones carved out from national terrain and disembedded from surrounding society, often entailing deviation from national regulations and – in the case of foreign, especially Chinese, investments – possessing characteristics of extraterritoriality (Lyttleton and Nyíri Citation2011).

The concept of zone is thus central in our analysis. In our deployment the zones are spaces of governing that ‘emerge by parcelling off a bounded area as a specific regulatory space’ and are thus non-contiguous and distinctive from their surrounding jurisdiction (Opitz and Tellmann Citation2012, 263). There is significant heterogeneity inherent in the zones as they may form spaces that are at once global and territorial (Opitz and Tellmann Citation2012), and they may take shape as territorially fixed zones (Vandergeest and Peluso Citation1995; Ong Citation2006) but they may also take shape as regulatory spaces formed by the standardisation of technical practices (Barry Citation2006). This heterogeneity is also present in the zones we analyse. While the CDM (and EIAs) represent a space of governing formed by technological devices and calculations (Methmann Citation2013) – that is, a technological zone: ‘[one] within which differences between technical practices, procedures and forms have been reduced, or common standards have been established’ (Barry Citation2006, 239) – the conservation, hydropower and logging zones are more territorially bounded. The zones also differ from each other in that they are variously nested within the space of state rule, and variously serve the rationales of global circulation and territorial state power consolidation. For example, the hydropower enclave shares some features of global territoriality (Opitz and Tellmann Citation2012) by facilitating global connectivity and providing foreign investors friction-free access to resources, and of extraterritoriality (Lyttleton and Nyíri Citation2011) in the sense of the de facto authority of Chinese state-owned hydropower companies within the enclave. The logging zone in turn rather resembles a kind of a micro-sovereignty (Humphrey Citation2004). But both zones also serve the pursuits of state power consolidation. Inherent to the zones are governing capacities but these are multivalent in the sense that they may end up also serving other than initially intended purposes. A common feature to all zones is that constitutive of the ‘zoneness’ are terms and mechanisms of exclusion that in turn are essentially about establishing order or governability (Humphrey Citation2004; Li Citation2014). In our study two dimensions of exclusion are critical. Firstly, by exclusion we refer to the regimes of exclusion (Li Citation2014) in relation to the resource control exercised within more territorially bounded zones, emphasising especially the mechanisms that delineate the resource uses and users that are allowed access from those that are excluded (Vandergeest and Peluso Citation1995)Footnote5. Secondly, exclusion refers to practices that establish boundaries for a particular ‘field of vision’ in which only certain aspects are included while others are excluded (Dean Citation1999, 29; Barry Citation2006); these are constitutive of the technological zones of CDMs and EIAs. The boundaries maintained through these exclusions are less clear than in the more territorial ones. Markedly novel in our study is the focus on relations between these different zones of exclusion. We underline that, despite the differing purposes of the zones, their overlaps and interaction may create situations where one zone provides enabling conditions for another, and that the interaction between the zones can have significant overall power effects that bring changes to the relations of resource control.

3. Cardamom Mountains: closures and openings of a resource frontier

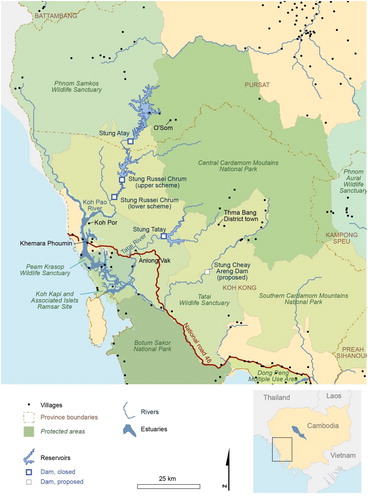

Up until 1998 the Cardamom Mountains were the last refuge of the Khmer Rouge, which protected the vast forests from widespread destruction, although not entirely from selective logging. Timber rents played an important part first in sustaining the insurgents, and later in accommodating the interests of the ex-Khmer Rouge to those of the new rulers (Le Billon Citation2002). During the 1990s the regime aimed to centralise control over timber exploitation through a World Bank-assisted logging concession system that became strongly criticised by the international donor community and was therefore suspended by Prime Minister Hun Sen in 2001 (Le Billon Citation2002). This provided an opportunity window for international conservation agencies that had realised the global importance of the Cardamoms’ conservation potential (Killeen Citation2012). In 2002 the protected areas increased significantly with the establishment of the Central Cardamom Mountains Protected Forest (CCMPF), which together with the already existing Phnom Samkos and Phnom Aural wildlife sanctuaries contiguously covered over 1,000,000 hectares. In 2004 the Southern Cardamoms Protected Forest was formed (see ).Footnote6 The international conservation organisations have been tightly woven into the governance of these protected areas, which form exclusive zones exemplifying fortress-type conservation with community-based elements targeting those within and near the protected areas. The schemes have provoked conflicts between conservationists and residents over resource use and access rights (Milne and Adams Citation2012). These approaches, however, did not include evictions of local residents, and there are villages inside the protected areas, as can be observed from .

Figure 1. Hydropower dams, reservoirs, protected areas (as since 2016) and villages in the Cardamom Mountains. (Source: Open Development Cambodia Citation2017).

In light of developments in the past five years it seems the government rationale regarding the Cardamoms is less about conservation as an end in itself and more about its role in preventing forested areas from turning into ungovernable spaces, meanwhile safeguarding valuable natural resources for future exploitation (see Kelly Citation2011). At the time the schemes were initiated, Cambodia was relying on outsiders such as international conservation NGOs to supply funds and means of control, seemingly giving them a strong bargaining position in terms of the area’s governance. Yet, the schemes also enabled the Forestry Administration and the Ministry of the Environment to establish their presence in the Cardamoms, strengthening the state’s ability to exercise central authority over these peripheral and contested areas and thereby facilitating state territorialisation (Vandergeest and Peluso Citation1995; Baird Citation2009; Milne Citation2015). The government has also made it clear that it does not want ‘too many’ entities co-governing resource use in the area. The listing of the Cardamom Mountains as a World Heritage Site, for example, has been opposed ‘because it is a place for the construction of hydroelectric plants … [forming] an electricity battery for Cambodia. These things belong to Khmers, so their use is to be … decided by us’ (Hun Sen quoted in The Mirror Citation2007).

In terms of frontier dynamics, the conservation schemes have aimed at closing the Cardamoms to peasants’ and in-migrants’ dispersed and decentralised forms of resource use, although not always successfully (Milne Citation2012). At the same time, however, the area has been opened to more centralised resource extraction in the form of large-scale hydropower schemes. The ability of the state to grant extraction concessions within the conservation zone proves its superior public authority compared to international co-governing entities; indeed, the pre-existing conservation regime inadvertently facilitated these concessions. As Barney (Citation2009) notes, resource frontiers are relational and often discursively represented as unharnessed and empty, thus erasing from consideration existing resource uses and users. In the case of the Cardamom Mountains the emptiness is relative but also somewhat more concrete, a state to which the exclusionary conservation schemes have contributed by at least partly slowing down the potential influx of new settlers to the area. Hence the area remains very sparsely populated and direct impacts of the dams in terms of the displacement and resettlement have been low – possibly, at least partly, explaining the lack of strong local resistance.Footnote7

4. The concessionary governing mode of the hydropower dams

Like almost all hydropower projects in Cambodia, the Cardamom projects are Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) concessions as laid out in the World Bank-influenced 2001 Electricity Law aimed at creating favourable conditions for the private sector to lead development in the power sector (Middleton, Matthews, and Mirumachi Citation2015). The Cardamom dams (Atay, 120 MW; Tatay, 246 MW; and Russei Chrum, 338 MW) are responsible for most of the recent increase from 308 MW to 1584 MW by the end of 2014 in Cambodia’s generation capacity; they are also part of the governmental strategy addressing the problems of expensive electricity and low domestic generation capacity with large-scale hydropower production backed by coal plants (RGC Citation2010).Footnote8

The BOT schemes are meant to ‘mobilise private capital to provide infrastructure traditionally funded by the public sector’ (Bakker Citation1999, 225), thus manifesting the neoliberal logic of contracting out core state functions to private providers (Islar Citation2012). The BOT terms (30–37 years) ensure long-term revenue flows to project developers as the projects are transferred to the government only in the final stages of the dams’ operational lives. Investor attractiveness has been further augmented with tax holidays, free-of-charge licences and government guarantees to purchase the electricity (Hensengerth Citation2015). Decisions are made in the Council for the Development of Cambodia, established as a ‘one-stop-service’ for investors, chaired by the prime minister and composed of senior ministers from the main government line agencies (Middleton Citation2008); rather exclusionary, they easily align with the opaqueness of authoritarian powers. The Atay, Tatay and Russei Chrum developers were contracted without public tendering or consultation, terms were negotiated behind closed doors and the visible support of the highest-level authorities influenced how these projects have been handled in the line ministries (Middleton Citation2008). This explains the relative ease of carrying out extractive projects within protected areas and why, at least in the case of Atay, construction started before the EIA approvals (IR Citation2015). Thus, the investors have benefited from both investor-friendly regulations and the state’s ability to provide contractual authority (Emel, Huber, and Makene Citation2011) and to make exceptions to normal regulations (Ong Citation2006) in ‘effective’ authoritarian ways.

Although the projects have been carried out by independent power producers (IPPs), they are not ‘independent’ or private sector-led in ways often assumed for BOT/IPP projects (Middleton, Matthews, and Mirumachi Citation2015). Rather, they are run by Chinese state-owned enterprises backed by Chinese public financiers, thereby blurring boundaries between public and private. Prime Minister Hun Sen has praised the Chinese companies for ‘adjusting their investment projects in accordance with their Government’s directions and in line with the recipient country’s demand’ (Hun Sen/CNV 23 February Citation2013). He has also framed the projects as evidence of the new strategic bilateral relations with Cambodia, resulting in increased flows of Chinese investments and aid to Cambodia (Hun Sen/CNV 12 January Citation2011). Still, the BOT/IPP model is significant as it provides considerable autonomy to developers in conducting their operations and lends itself to enclavistic development. Moreover, as such projects are carried out with scant state involvement, they do not produce significant ‘hydraulic capacities’ for state planners or strengthen the ‘bureaucratic state powers’ as has been the case in the conventional ‘hydraulic missions’ (Scott Citation1998; Molle, Mollinga, and Wester Citation2009; Harris Citation2012). Thus, although large in scale, they do not provide the ‘means to demonstrate the strength of the modern state as a techno-economic power’ (Mitchell Citation2002, 21). On the other hand, they are discursively constructed as joint achievements requiring the decisive efforts of the ruling regime, thereby demonstrating state power in other ways. Prime Minister Hun Sen has emphasised his role in mobilising necessary resources via his personal visits to meet ‘the Chinese leaders’ while presenting the projects as reflecting his party’s provision of the crucial investment precondition of stability in remote and previously ‘unruly’ corners of the Cardamoms (Hun Sen/CNV 28 December Citation2010).

Overall, the exclusive corporate enclaves of the Cardamom BOT hydropower projects exemplify a concessionary model of development in Cambodia which is shaped by a combination of neoliberal investment policies and opaque authoritarian decisions. They present the main new ownership regime over rivers with electricity-producing potential. Although they depend on foreign developers and investors and do not strengthen ‘bureaucratic state powers’, they are framed as great achievements by the current regime and are therefore tied to efforts to consolidate state power. Moreover, these projects are entangled with the multifaceted bilateral relationships between Cambodia and China (Sullivan Citation2015) in which both profit accumulation and power consolidation matter.

5. The CDM’s and EIAs’ bracketing of vulnerabilisation

The global significance of the Cardamom dams is constituted through their linkage to carbon markets. Cambodia has been a forerunner in the global carbon frontier in the least developed countries (LDCs) amongst which it hosts the second highest number of CDM projects (UNEP DTU Partnership Citation2016), with the Atay, Tatay and Russei Chrum hydropower dams producing the biggest share (76 percent) of the projected carbon credits (see ). The CDM has the dual objective of assisting industrialised countries to achieve their emission-reduction targets by buying credits from mitigation projects carried out in developing countries and assisting project-host countries to achieve sustainable development. The final buyers of future credits from the Cardamom dams are Switzerland (Russei Chrum), Sweden (Atay) and the Netherlands (Tatay) via carbon traders belonging to the top 20 credit buyers (UNEP DTU Partnership Citation2016). The sustainable development gains from Russei Chrum, Atay and Tatay are claimed to provide ‘great benefit to the national economy and environmental sustainability’ (CDM-EB Citation2012, 2), stimulate local economic development, ameliorate the electricity shortage (CDM-EB Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2012) and create local employment opportunities during the construction and operation periods (CDM-EB Citation2012, 2).

Table 1. Facts of the CDM projects.

It is questionable whether the projects will produce ‘real’ emission reductions, however, as they are hardly ‘additional’ (IR Citation2013) and they are indirectly linked to building coal power plants to level seasonal fluctuations in the dams’ power production. In our analysis, however, the focus is on how the seeming sophistication of performative equations (Lohmann Citation2014) in accounting for ‘virtual’ carbon reductions (Cavanagh and Benjaminsen Citation2014) obscures the processes of vulnerabilisation, dispossession and exploitation that have been part of the production of the ‘virtual’ carbon commodity. Initially, the CDM was expected to result in projects that were ‘better than the baseline’, as put by an interviewed official (in 2011), that is, better than could be achieved through the usual regulatory measures – thus forming ‘sustainability enclaves’ (Whitington Citation2012). Instead, as shown in the next sections, the Cardamom dam projects resulted in exceptionally exploitative enclaves where environmental and labour norms have been suspended, seriously failing in terms of delivering ‘sustainable development benefits’.

Here, it is worth reviewing how the CDM works as a technological zone that provides common standards of critical importance to the functioning of global carbon markets. The technologies at the core of the CDM relate to the production of certified emission reductions, the commodity sold in the carbon markets, which must be defined technically and legally and made transferable and tradable (MacKenzie Citation2009). This requires standardisation, simplification and commensuration by different scientific experts, verifiers and monitors (Gupta et al. Citation2012). As for so-called sustainable development benefits it is the host countries that hold the decision-making power over their standards and criteria and evaluate whether they are met. As a result, they are not substantially included, but rather are excluded from the global technological zone of the CDM, whose evaluative grids effectively encompass only elements given value in terms of carbon. In the case of the Cardamom dams and their CDM procedures, ‘non-carbon elements’ were mainly addressed by referring to national approval of the projects and by using the projects’ impact assessments to demonstrate their sustainability. The officials in our interviews were reluctant to discuss the Cardamom CDM dams, but some described the projects as ‘political’ and hinted that despite the projects failing to meet the national sustainable development criteria there was pressure from high-level officials to accept them. One official even stated (February 2013) he was ‘surprised that the dam projects eventually got registered [by the CDM Executive Board]’.

Next we examine how the indifference of the CDM’s technological zone to the sustainable development shortcomings of the dams was facilitated by the expediently limited zones of impacts produced by the EIAs. Impact assessments supposedly constitute the key device in informed consultations and decision-making by producing and presenting the anticipated zone of impacts; they also define what is at stake and who is to be included in, or excluded from, consultations (Lamb Citation2014). In the case of the Russei Chrum, Tatay and Atay Dams, the EIAs produced a very limited zone of impacts, including only immediate areas and mainly direct impacts such as biodiversity losses due to the reservoirs, while excluding or seriously downplaying longer term losses in downstream fisheries and related livelihoods. Consequently, not all affected people were consulted, while those who were did not anticipate the extent of dam-induced changes. Moreover, expectations of benefits were raised by promises of electrification and compensation. Combined with the absence of major immediate displacements, these problematic impact assessment processes are likely to have lowered opposition to the dams.

The Tatay Dam EIA (KCC Citation2010), for instance, did not consider fishery impacts to be relevant despite the fact that most of the 1000 people living along the Tatai River are part-time fishers. On the Koh Pao River, downstream from Russei Chrum, fishing and crabbing are the primary sources of livelihoods for many. Here the dam’s impact on fisheries was at least acknowledged by the EIA; 1064 people in three villages were estimated to be potentially affected (SAWAC Citation2010). However, if all the fishing communities downstream along the Koh Pao River were taken into account the figure might be as much as 20 times the EIA’s estimate: around 15,000–20,000 people in 10–15 villages.Footnote9 Even in the provincial capital of Koh Kong, located along the Koh Pao River the poorest families fish regularly, and if they were included the figure would be higher still. All interviewed villagers had noted a significant decline in numbers of fish after the construction of the dams, also identifying the rampant sand mining in Koh Pao and Tatai Rivers as a contributory cause. A study by Kastl et al. (Citation2013) states that the two have together caused a dramatic 70–90 percent reduction in fish catches in the downstream areas of Tatai. It is the combined effect that worries many of the downstream residents the most. As one in Koh Por commented (March 2014), ‘Less fish means less income. If in the future there is no fish or crab what will happen, where do we go? … Maybe in the future we will be forced to sell our labour’. The changes are experienced differentially, and most heavily by the land poor who form the majority in the villages along Koh Pao River.

Also excluded from the zone of impacts by the EIAs is the Koh Kong estuary, containing the largest mangrove forests of South-east Asia and some of Cambodia’s best-known coastal fishing villages, where crabs and fisheries are vital to sustaining most peoples’ livelihoods (Marschke Citation2012). Yet its mangrove ecosystems, fisheries and fishers are likely to be significantly affected by the cumulative impacts of the dams (Killeen Citation2012; Kastl et al. Citation2013). Cambodia has been repeatedly identified as one of the most vulnerable countries in the world in terms of climate change, with the most sensitive areas located along its coast (BEH Citation2012). Yet it has been noted that the mangrove ecosystems ‘provide invaluable protection from climate change impacts and create an environment in which communities can build coastal resilience’ (Kastl et al. Citation2013, 4). Through damage to mangroves and fisheries the CDM dams are thus contributing to further vulnerabilisation of the coastal fishers in terms of climate change.

The communities excluded from the projected impact zone were also excluded from consultations, while the consent of those included was constructed by limited portrayals of impacts and un-kept promises of benefits and compensations. For example, in Koh Por village, downstream from Russei Chrum, people recalled how an EIA survey team conducted door-to-door interviews, promising electricity at a reduced price. Yet all the electricity is being transmitted elsewhere and now the people of the village are disappointed. As the village chief commented (March 2013):

The villagers didn’t understand what the survey team was actually doing. People just heard they would get electricity and they were happy …. They said to villagers, that if we keep all of nature in its natural condition you do not get any electricity … I think many were just thinking about the electricity and not, for example, the fish.

In the case of Tatay, formal consultations were more ‘participatory’ in the sense that more villagers were present, but only in the first meeting. The consultation mostly consisted of expositions on the benefits of the dam, and again electricity was promised. According to some informants, critical questions were prevented by an intimidating atmosphere. A foreign worker at an eco-lodge along the Tatai River described the first meeting as ‘just a complete whitewash to tick the box to say the villagers are in favour of the dam’ (March 2014). At the second Tatay consultation, in which almost no locals were present, it was finally admitted that the electricity would go straight to the Phnom Penh grid.

Each of the EIAs (KCC Citation2010; SAWAC Citation2010, Citation2011) concludes that all relevant stakeholders supported the project but, as shown above, this consent was produced in problematical ways. The EIAs were not made publicly accessible and thus were never exposed to broader public discussion. And, at least in the case of Atay, the EIA was officially approved only after dam construction had already started (IR Citation2015). The EIA results were, however, more decisive in relation to accepting these dams as CDM projects, also becoming partially public via the CDM project design documents and validation reports that included copy-pasted excerpts from the EIAs and summarised key results. The limited zones of impacts and the claims of local support for the projects were thus circulated and reproduced in the CDM documents, but in so decontextualised a form that it is impossible to assess the validity of the results. Thus, the manner in which the EIAs entered the technological zone of the CDM further bracketed the dispossession and vulnerabilisation caused by the dams.

Via the CDM documents the EIAs had the performative role (Callon Citation2007) of producing the sustainability that is required for CDM projects to be approved by the CDM Executive Board. Overall, the work of the CDM Executive Board is mostly tuned to carbon assessments because the main role in calculating sustainable development benefits has been assigned to the national authorities; the CDM architecture thereby allows inadequate scrutiny, especially in the validation stage, for non-carbon elements, and deploys uncritical and vague methods when cross-checking sustainability assessments and consultations (Kuchler and Lövbrand Citation2016). After CDM projects have been approved only emission reductions are constantly monitored, so once the projects have entered the carbon markets they become even more abstracted from how and where the emission reductions are made (Lohmann Citation2008; Lovell and Liverman Citation2010); meanwhile, the socio-ecological interactions and the labour relations that are essentially part of the production of the certified emission reductions commodity are rendered invisible.

6. The Chinese corporate hydropower enclaves

This section examines how the sites of Atay, Russei Chrum and Tatay form zones governed principally by corporate authorities, and the modes of exclusion facilitating exploitative labour practices. The hydropower concessions were granted to joint ventures of Datang (Atay), Huadian (Russei Chrum) and China National Heavy Machinery (Tatay), all Chinese-state-owned, overseas hydropower companies. The concessionary BOT/IPP hydropower model lends these companies considerable autonomy in their operations. The projects consist of fenced enclaves with special regulations, tax holidays and limited government oversight, wherein the corporate authority exerts de facto control over the conditions of living, labouring and the movement of people. In terms of these privileged rights and surrendered degrees of state sovereign power these zones have ‘extraterritorial’ features (Lyttleton and Nyíri Citation2011) further manifested in Chinese being the main language used, and the technical staff and a significant number of workers coming from China.Footnote10

The disconnectedness from surrounding society means that people outside have little information on dam operations. When a partial collapse occurred at Atay, no details were reported to the local authorities (IR Citation2015). Even the normal public disclosure mechanisms are lacking, although operations, especially of the Russei Chrum and Tatay Dams, may rapidly cause major water-level fluctuations (IR Citation2015). The people living in the vicinity are concerned about dam safety and afraid of accidents. Downstream from Tatay a villager from Anlong Vak commented (March 2013), ‘We lack information about the dam … If the dam breaks we will die’. Information about working conditions inside has been almost non-existent, as administrators, NGOs and other ‘outsiders’ are not allowed to enter the zones. As an interviewed village chief observed (March 2014), ‘Local authorities don’t know what happens inside. I have never been inside. But I know, if something happens it is very different from the factories in Phnom Penh, as there is no union and no way to complain’. An NGO representative working in Koh Kong’s provincial capital added (March 2014) the observation, ‘Normally the role of our organisation would be to train people in their rights as workers, but in this case the company controls the area so strictly that we have had no chance for doing that’.

The number of workers at each site during the construction phase varies, according to different sources,Footnote11 from 2000 to 4000.Footnote12 Harsh, incarceral labour conditions marked the approximately five-year construction phase of the dams during which all workers had to stay within the project site. The company provided them with accommodation and food, and they were allowed out only on public holidays, if then. The interviewed ex-workers complained (March 2013 and March 2014) of low salaries,Footnote13 maltreatment and unsafe working conditions resulting in injuries that often went uncompensated.Footnote14 At least fifteen peopleFootnote15 lost their lives in different accidents.

The local employment opportunities that were promised, for example in CDM documents, were not taken up because after initial interest locals refused to work on the construction sites which were eventually largely run with a migrant Khmer and Chinese workforce. Apparently, it proved harder to turn the local villagers into ‘disciplined labour’ than the migrants, who were more dependent on the employer and likelier to obey the incarceral ruling. As a local NGO worker informant explained (March 2014):

The majority of the [local] people don’t want to work for them. Only those who have no other choice …. The locals prefer to go to Thailand. And the fishermen prefer to fish … It is actually easier to find loggers [for the companies contracted to clear the reservoir] than people to work on the dam construction.

Local and national-level authorities have been reluctant to oversee safety issues or carry out investigations of the incidents, reacting only after NGO or media interventions. While workers’ rights in Cambodia are at best contested and emergent, the rise of concession enclaves such as those described here have created ever more precarious working conditions, leaving the workers disenfranchised with nowhere to look for protection. Non-interference in exploitative labour practices appears to be a deliberate state strategy to guarantee conditions of profitability for the project concessionaires (Arnold and Pickles Citation2011), to be measured against the larger complex of Cambodia–China relations (Sullivan Citation2015; see also Mohan Citation2013). The exclusiveness of the enclaves has sheltered the investors and hidden the ways inexpensive labour has been produced and exploited.

7. Exclusive logging zones in the shadows of the hydropower dams

Infrastructures incorporate the power to rearrange relations between people and things and reorganise access to material resources (Harvey and Knox Citation2015); they may also shape activities in ways that ‘remain unstated but are nevertheless consequential’ (Easterling Citation2014, 15). The infrastructure of the Cardamom hydropower projects consists of not only dams but also transmission lines, reservoirs and new roads. The designated reservoir areas are commonly first cleared of all vegetation to avoid eutrophication and methane emissions from rotting vegetation, as well as disruptions in the water flow and the waste of valuable timber. In the case of Cardamom dams the clearance permits, partly facilitated by new roads, enabled logging that eventually extended well beyond concession boundaries. Roads as infrastructural forms subsume potentially unruly forces (Harvey and Knox Citation2015) as they often instigate frontier dynamics (Tsing Citation2005) by making previously inaccessible areas accessible. In this way they create new possibilities for economic circulation. However, in this case the flows of resources and profits were strictly controlled. The mechanisms of exclusion and control of the conservation zone were significant in ensuring the governability of logging activities (Milne Citation2015).

Two Cambodian-run companies with close ties to the country’s ruling elite (Milne Citation2015) – MDS for Atay, and Timbergreen for Tatay and Russei Chrum – were authorised to carry out the clearance. The logging contract for Atay in the O’Som commune was issued in May 2009. By June 2009 there were already reports of logging outside agreed boundaries (Shay and Sokha Citation2009; Cambodia Daily Citation2009a; Cambodia Daily Citation2009b). An unpublished report by an international conservation group in 2012 estimated that MDS operations extended into conservation zones to the tune of 200,000 hectares, and at least 16,135 cubic metres of rosewood had been logged. This alone would have made the company between 220 and 310 million USD.Footnote16 The main stocks of rosewood were exhausted by 2012, but less intensive logging continued even in 2014 when the dam was already operational (Titthara Citation2014a). Actual reservoir clearance was only partial, causing problems in water quality (IR Citation2015) and – ironically for a CDM project supposedly mitigating climate change – higher emissions of greenhouse gases.

As Milne (Citation2015) has pointed out, Forestry Administration officials and military police not only allowed but also facilitated the logging activities; their semi-legal involvement enforced the exclusive monopolisation of logging by the licensed companies as Forestry Administration’s conservation staff monitored activities in the area, and confiscated all ‘independently’ logged timber and handed it over to the licensee. In return the Forestry Administration benefited from the arrangement through a kind of informal taxation, receiving payments from every MDS truck of rosewood that passed its checkpoints. The means developed for conservation purposes (and supported by international NGOs) in terms of surveying, monitoring and control thus also served as mechanisms of exclusion for logging purposes. The maps and knowledge of the locations of valuable timber also benefitted the logging company.

Logging contracts for Tatay (2000 hectares) and Russei Chrum (1500 hectares) reservoirs were awarded to Timbergreen in 2010. Again, logging extended well beyond the contract boundaries and, according to informants and media sources, the mode and scale of operations were similar to those at Atay. An opposition member of parliament noted at the end of 2011 that logging in Thma Bang was accelerating because loggers no longer worried about getting caught; investigative journalists uncovered organised logging in the area soon after (Boyle Citation2011; Stout and Chakrya Citation2011; Boyle and Titthara Citation2012). A well-known environmental activist, Chut Wutty, who had attempted to expose Timbergreen’s activities and its connections to military officials, was shot dead near Russei Chrum. This put Timbergreen in the media spotlight for a while, but no formal investigations followed, which suggests that Timbergreen operations had silent authorisation from the highest official level.

The timber extraction operations were carried out in mobile logging zones characterised by exclusiveness and ‘exceptional rules’. As a local NGO representative commented (February 2013): ‘Their [logging companies’] zones of operation move all the time. To get in there is very difficult. They control all the movements of people’. The ‘exceptional rules’ were captured by a journalist:

In the town of Thma Bang, military police and soldiers infest the streets, patrolling the area like a small, privately owned fiefdom. They are known to use intimidation against anyone potentially jeopardising the interests of the … businessmen and officials profiting from the illegal rosewood trade. (Titthara, Boyle, and Cheong Citation2013)

For Try Pheap, the okhna or tycoon behind MDS, Atay served as a testing ground for a new modality of logging or ‘timber laundering’ subsequently replicated elsewhere (Global Witness Citation2015; Milne Citation2015). In fact, Try Pheap has ‘[gained] a monopoly on all clearing, trading and export of rare luxury timber species in Cambodia’ (Global Witness Citation2015, 18). Meanwhile, the profits from logging are circulating in new activities such as SEZs, mining concessions and holiday resorts. State powers granting permits and enabling exclusive and rather violent resource appropriation have been essential to this circulation and accumulation of profits.

Primitive accumulation and profit-making are, however, not the only logics at stake. Try Pheap has been ‘allowed to get rich’, but only in return for loyalty and significant contributions to the CPP-controlled off-budget funds used for roads, bridges, pagodas, schools and administrative facilities (Global Witness Citation2015; Milne Citation2015). His company has also funded several army battalions through a sponsorship programme (Global Witness Citation2015) established because ‘the Cambodian army is consistently short of resources’ (Verver and Dahles Citation2015, 62). Thus, the logics also relate to state power consolidation and even to assembling the state’s sovereign powers of territorial control through relations of patronage. Here the blurred boundaries of legal and illegal seem to work as ‘technologies of sovereignty’ (Humphrey Citation2004, 429). State-authorised clearance provided the appearance of legality to logging outside the reservoir boundaries and enabled state authorities (and conservation organisations) to ‘look the other way’ and bend rules on conservation and protected timber species without being overtly exposed to international pressure and criticism. In this kind of terrain the powerful tycoons are perhaps kept more ruly as ‘looking the other way’ can always be suspended. In addition, these semi-legal arrangements keep a substantial proportion of the timber rents off the official state budget and facilitate their channelling into CPP-controlled funds, thereby keeping the capacities of the state dependent on the ruling party (Craig and Kimchoeun Citation2011; Hughes and Un Citation2011; Milne Citation2015).

Timber extraction is organised in mobile, exclusive zones with their own coercive and paralegal measures of control wherein regular laws are replaced by a system with its own rules of operation, which makes use of the conservation zone’s regime of exclusion. At the same time the zones operate in collaboration with elements of the state (including the Forestry Administration and military police), and produce funds partly channelled into functions integral to state sovereign powers. Consequently, although the logging zones almost resemble a type of micro-sovereignty (Humphrey Citation2004) with their own rule-making and enforcing capacities, they are only partly excluded from the political space of state authority as they eventually also serve the goal of the party-state to strengthen its sovereign powers.

8. Discussion: the consequential interaction between the zones of exclusion

We have examined the operations and governing logics of distinct zones of exclusion and how they relate to each other. Here we bring forth more systematically the interaction between the studied zones and the effects and relevance of this interaction that importantly takes place through the distinct mechanisms of exclusion that are constitutive to each zone (see also ). Our findings indicate that the exclusionary mechanisms of the conservation zone enabled state territorialisation and, by limiting potential in-migration, partly facilitated the major hydropower investments in the area. Together with the conservation zone the construction of the hydropower dams enabled the emergence of exclusive logging zones through roads and other infrastructure which made previously inaccessible areas accessible, and reservoir clearance permits which provided cover for logging activities. Whereas the capital-intensive and concentrated, large-scale hydropower production enables the establishment of exclusionary spatial enclaves, activities like timber extraction are harder to insulate in a similar way. The pre-existing exclusionary conservation zone in the Cardamoms, however, partly constituted the mechanisms of exclusion required for monopolised extraction of timber that is widely spatially dispersed and requires relatively low capital investment.

Table 2. Elemental aspects of the zones of exclusion discussed in the paper.

The interaction between the zones through their exclusionary mechanisms was also significant in terms of the politics of visibility. The CDM element has exposed the Cardamoms’ hydropower projects internationally, but with the global gaze fixed on emission units in international carbon markets, the CDM, along with the EIAs, has obscured the ways the projects are intertwined with power relations and resource politics, as well as the dispossessions and vulnerabilisation set in motion by the dams. Together, the exclusionary hydropower and logging zones and the technological zone of the CDM have kept socio-ecological consequences and exploitative labour relations largely invisible. The interacting exclusionary hydropower and logging zones, along with the exclusionary and limited field of vision produced by the technological CDM zone, at the time seemed to align conveniently with the government’s intentions to keep ‘public transcripts’ of resource use in line with sustainable development agendas while shielding authoritarian and neo-patrimonial extractive practices from international oversight. Despite the increase of Chinese aid and investments, Western donors have remained important, at least until recent times,Footnote17 possibly with the rationale that good relations with Western powers may counterbalance the increasingly powerful presence of China (Sullivan Citation2015).

The studied zones are variously nested within the space of state rule. Yet even the zones most excluded from state control, like the semi-sovereign logging zones and the hydropower zones under the de facto control of the Chinese companies, became entangled with the state’s efforts to strengthen its capacities for resource control. The zones also varied significantly in their governing rationales. Yet even the zones that may most seem to serve the securing of global circulation – like the CDM zone that facilitates carbon markets and the concessionary BOT/IPP corporate hydropower enclaves – became entangled with processes of state power consolidation, especially through their interaction with the other zones. The ways the zones fragment the space of state rule means that the presence of state power in some processes of resource use is reduced, but this seems to be more about variegated sovereignty than about compromised sovereignty (Ong Citation2006).

Our analysis of the dynamics related to the zones and their interaction emphasised the entangled and often co-dependant relations between profit accumulation and state power consolidation, as demonstrated by the complex of Sino–Cambodian relations that forms around the hydropower enclaves, and by relations between domestic business tycoons and ruling party authorities around the logging zones. The ruling party authorities in Cambodia seem to be able to make at least some use of the enclavist concessionary governing mode of hydropower for their own purposes despite, for example, the inhibited production of state hydraulic capacities. The usual expectations of accelerated economic development, local job creation, technology transfer and other similar ‘spill-over’ or ‘multiplier effects’ that are often used to justify the enclave model have been shown to materialise rarely in enclaved economies (Ferguson Citation2006), and the case discussed here is no exception.Footnote18 It is, however, through other type of effects overflowing the enclave boundaries, like the triggered para-legal logging, that domestic accumulation of profits was mobilised. And it is the rents from these activities that the current regime is able to use for its own strengthening.

For the forest and fisher communities in south-west Cambodia the overlapping zones of exclusion have decreased livelihood options, circumscribed resource-use autonomy and increased labour market dependency. Yet neither dispossessed fishers nor intimidated forest community members have significantly challenged the on-going resource appropriations. It appears that the lack of strong or concerted resistance has to do with the combined effects of the different zones of exclusion. The conservation zone may have pre-empted local resistance to the dams by keeping the area sparsely populated, thus contributing to the lack of physical dispossession or displacement. The EIAs were used to buy consent via the limited zone of impacts produced which excluded most of the losses in downstream fisheries from consideration, while the CDM methods reproduced these exclusions thereby excluding most of the dams’ serious effects from international circulation. Finally, the zones of logging operations enrolled many of the villagers into semi-illegal relations that made them evasive about making public claims.

There have been, however, some signs that the consolidation of the power of the Cambodian state through the interplay of neoliberal, patrimonial and authoritarian logics of resource control may ultimately turn against the regime. Violent concession policies have increasingly been countered by community mobilisation, especially in cases of direct displacement, and support for the regime has shrunk (Biddulph Citation2014, Milne and Mahanty Citation2015).Footnote19

9. Conclusion

Through a study of three CDM hydropower dams located within the protected forests of the Cardamom Mountains, we have shown how the interplay of the different logics of governing the environment, resources and people in Cambodia has materialised in overlapping zones of exclusion that co-produce new relations of resource control. We have brought to the fore the co-constitutive elements of the zones and the effects of their interconnections. Together these have meant more centralised resource control as well as bracketing of the associated dispossessions. These effects should not be considered a pre-given end point as the operations and interconnections of the zones maintain considerable indeterminacy. Our analysis has also shed light on the multivalence of the zones in the sense that the governing capacities they possess may serve also purposes other than those initially intended. Furthermore, our study has shown how the governing rationales of territorial fixation and securing of global circulation may shape resource control in parallel and interacting ways, and that processes of territorial fragmentation do not necessarily mean compromised state sovereignty.

With this contribution we hope to have demonstrated the potential of an analysis that takes seriously the overlaps and entanglements of disparate resource control schemes that often remain invisible and underanalysed in more project-based case studies. Similar, situated, multi-resource analysis in which the interactions between divergent rationalities and distinct resource control schemes are considered may also be revealing in other places of intense resource politics, especially in other dynamic frontier constellations where both resources and states are in the making. It could be useful also for other studies that analyse how global climate change initiatives get entangled with on-the-ground relations of resource control. Furthermore, the conceptual idea of overlapping zones of exclusion could be generative more broadly in efforts seeking to come to grips with the heterogeneous and intersecting spaces of governing.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (grant number 277182), Helsinki University Doctoral Programme in Political, Societal and Regional Change and Helsinki University Centre for Environment. The paper benefited from insightful comments by Anja Nygren, Turo-Kimmo Lehtonen, Tuomas Tammisto, Anna Salmivaara, Mike Dywer, Jun Borras, Marcus Taylor, Jason W. Moore and Nancy Lee Peluso. Helpful comments on an early draft were received from Mattias Borg Rasmussen, Andrea Nightingale and others at the seminar ‘Governance at the Edge of the State: Public Authority and Property in Conflict Environments’, University of Copenhagen, September 2015. Thanks to Matti Kummu for help in producing Figure 1. The authors are also grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their carefully considered and helpful suggestions.

Notes on contributors

Mira Käkönen is a project researcher and a PhD candidate in development studies, University of Helsinki. Over the past 10 years she has worked in various research projects on water, energy and climate change governance in the Mekong Region, with an interest in the power dynamics that shape relations of resource control.

Try Thuon is an adjunct lecturer and a researcher at the Faculty of Development Studies, Royal University of Phnom Penh, and a PhD candidate with the Doctoral Program in Social Science, Chiang Mai University. He has over a decade of experience in Cambodia and neighbouring countries working on resource governance and rural livelihoods.

ORCID

Mira Käkönen http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2350-4020

Try Thuon http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2064-8237

Notes

1 The topic is politically sensitive; thus, preserving anonymity of all interviewees is critical.

2 The rationale of territorial fixation is thus about centripetal logics of spatial ordering geared towards the state, with unlimited ‘reason of state’, whereas the rationale of securing global circulation is about centrifugal logics of spatial ordering geared towards enabling global circulation and the formation and expansion of global systems, accompanied by the liberal ‘reason of least state’ (Foucault Citation2007, 44–45, Citation2008,52; see also Sassen Citation2006).

3 These are in a way efforts at closing down parts of the opening frontiers, but still they do not exactly form a counter-force but rather the other side of the coin of the commodification logic (Biermann and Mansfield Citation2014).

4 These authoritarian logics of governing correlate with the rationale of territorial fixation and the intensification of the state’s resource control.

5 We align here also with the definition of exclusion by Hall et al. (Citation2011, 7): ‘the ways in which people are prevented from benefitting from things’ which encompasses a broader range of processes than concepts of enclosure, primitive accumulation or accumulation by dispossession to include goals not reducible to profit accumulation.

6 In 2016 the protected forests were upgraded to national parks and transferred from the Forestry Administration to the Ministry of Environment. The area under protection was also expanded, especially in the Southern Cardamoms.

7 One of the planned Cardamom dams, Cheay Areng, would have displaced around 1500 people but has been stalled, mostly because of local resistance and unprecedented mobilisations supported by civil society groups (Hensengerth Citation2017). This seems to support the assumption that projects with heavy direct displacements are likely to be opposed.

8 Nonetheless, electricity remains unevenly distributed, with a low electrification rate (34 percent, IEA Citation2015).

9 Estimate based on Dara et al. (Citation2009), Kastl et al. (Citation2013) and RGC (Citation2014).

10 For example, in the construction phase of Russei Chrum, out of approximately 2400 workers possibly 300–400 (IR Citation2015) or even 500 (interviewed ex-worker, March 2015) came from China, as for Atay a senior engineer of Huadian estimated in media that half of the 4000 workers were Chinese (Becker Citation2011).

11 Media sources, interviews and the EIAs.

12 Now that the dams are operational, only around 100–200 workers remain at each, and working and living conditions seem to be relatively well organised.

13 We were, for example, told that at Russei Chrum workers protested because of low salaries in 2011 and 2012, after which monthly salaries were raised from 150–160 USD to 200–280 USD which still were considered low.

14 Similar views have been presented also in media sources (e.g. Titthara and Boyle Citation2012).

15 The figure is compiled from media sources: Kongkea (Citation2011); Chakrya (Citation2011); Titthara (Citation2011, Citation2012); Nimol (Citation2011); Titthara and White (Citation2012).

16 Based on estimations in Pye and Titthara (Citation2014); Titthara and Pye (Citation2014); Pye (Citation2015).

17 More recently, however, the government has been increasingly more open in opposing all Western donor pressure and opted more decidedly for increased reliance on Chinese investment and aid (e.g. Thul Citation2017).

18 Apart from the possible economic multiplier effects of the increased electricity production transmitted to the national grid that, however, still covers only the central provinces, excluding e.g. Koh Kong.

19 However, currently the threats to its power have made the ruling party focus ever more decidedly on efforts to break all opposing forces (Peou Citation2017).

References

- Arnold, D., and J. Pickles. 2011. “Global Work, Surplus Labor, and the Precarious Economies of the Border.” Antipode 43 (5): 1598–1624.

- Bäckstrand, K., and E. Lövbrand. 2006. “Planting Trees to Mitigate Climate Change: Contested Discourses of Ecological Modernization, Green Governmentality and Civic Environmentalism.” Global Environmental Politics 6 (1): 50–75.

- Baird, I. G. 2009. “Controlling the Margins: Conservation and State Power in Northeastern Cambodia.” In Development and Dominion: Indigenous Peoples of Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos, edited by F. Bourdier, 215–248. Bangkok: White Lotus.

- Baird, I., and K. Barney. 2017. “The Political Ecology of Cross-Sectoral Cumulative Impacts: Modern Landscapes, Large Hydropower Dams and Industrial Tree Plantations in Laos and Cambodia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (4): 769–795. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1289921.

- Bakker, K. 1999. “The Politics of Hydropower: Developing the Mekong.” Political Geography 18 (2): 209–232.

- Bakker, K. 2005. “Neoliberal Nature? Market Environmentalism in Water Supply of England and Wales.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95 (3): 542–565.

- Barney, K. 2009. “Laos and the Making of a ‘Relational’ Resource Frontier.” The Geographical Journal 175 (2): 146–159.

- Barney, K. 2017. “Environmental Neoliberalism in Southeast Asia.” In Handbook of the Environment in Southeast Asia, edited by P. Hirsch, 99–114. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Barry, A. 2006. “Technological Zones.” European Journal of Social Theory 9 (2): 239–253.

- Becker, S. A. 2011. “Chinese Engineer Loves Living in Cambodia.” Phnom Penh Post, September 30.

- BEH [Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft]. 2012. World Risk Report 2012. United Nations University (EHS). Berlin: Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft.

- Biddulph, R. 2014. “Can Elite Corruption be a Legitimate Machiavellian Tool in an Unruly World? The Case of Post-Conflict Cambodia.” Third World Quarterly 35 (5): 872–887. doi:10.1080/01436597.2014.921435.

- Biermann, C., and B. Mansfield. 2014. “Biodiversity, Purity, and Death: Conservation Biology as Biopolitics.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32 (2): 257–273.

- Boyle, D. 2011. “Logging in the Wild West.” Phnom Penh Post, December 21.

- Boyle, B., and M. Titthara. 2012. “Blind eye to forest’s plight.” Phnom Penh Post, March 26.

- Bridge, G. 2014. “Resource Geographies II: The Resource-State Nexus.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (1): 118–130.

- Callon, M. 2007. “What Does it Mean to Say That Economics is Performative?” In Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics, edited by D. MacKenzie, F. Muniesa, and L. Siu, 311–357. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cambodia Daily. 2009a. “Alleged Logging Near Dam Site Worries Environmentalists.” Cambodia Daily, June 12.

- Cambodia Daily. 2009b. “Gov’t, Environmental Groups To Cooperate on Land Concession.” Cambodia Daily, June 17.

- Cavanagh, C., and T. B. Benjaminsen. 2014. “Virtual Nature, Violent Accumulation: The ‘Spectacular Failure’ of Carbon Offsetting at a Ugandan National Park.” Geoforum 56: 55–65. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.06.013.

- CDM-EB [CDM Executive Board]. 2011a. Clean Development Mechanism Project Design Document Form (CDM-PDD) of Lower Stung Russei Chrum Hydro-Electric Project, PDD Version 2.0, Completion date 21/09/2011. UNFCCC: http://cdm.unfccc.int/Projects/DB/BVQI1345566732.13/view.

- CDM-EB [CDM Executive Board]. 2011b. Clean Development Mechanism Project Design Document Form (CDM-PDD) of Stung Tatay Hydroelectric Project, PDD Version 2.0, Completion date 08/12/2011. UNFCCC: https://cdm.unfccc.int/Projects/DB/BVQI1355457198.66/view.

- CDM-EB [CDM Executive Board]. 2012. Clean Development Mechanism Project Design Document Form (CDM-PDD) of Cambodia Stung Atai Hydropower Project. UNFCCC: http://cdm.unfccc.int/Projects/DB/JCI1355902421.49/view.

- Chakrya, K. S. 2011. “Third Worker Killed at Hydrodam.” Phnom Penh Post, July 14.

- Cock, A. 2010. “External Actors and the Relative Autonomy of the Ruling Elite in Post–UNTAC Cambodia.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 41 (2): 241–265.

- Collier, S. J., and A. Ong. 2005. “Global Assemblages, Anthropological Problems.” In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems, edited by A. Ong, and S. J. Collier, 3–21. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Craig, D., and P. Kimchoeun. 2011. “Party Financing of Local Investment Projects: Elite and Mass Patronage.” In Cambodia’s Economic Transformation, edited by C. Hughes, and K. Un, 199–244. Copenhagen: NIAS.

- Dara, A., K. Kimsreng, H. Piseth, and R. J. Mather. 2009. An Integrated Assessment for Preliminary Zoning of Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary, Southwestern Cambodia. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Davis, K. F., K. Yu, M. C. Rulli, L. Picharda, and P. D’Odorico. 2015. “Accelerated Deforestation Driven by Large-Scale Land Acquisitions in Cambodia.” Nature Geoscience 8: 772–775. doi:10.1038/NGEO2540.

- Dean, M. 1999. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Diepart, J. C., and D. Dupuis. 2014. “The Peasants in Turmoil: Khmer Rouge, State Formation and the Control of Land in Northwest Cambodia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (4): 445–468.

- Dwyer, M. B. 2011. “Territorial Affairs: Turning Battlefields into Marketplaces in Postwar Laos.” PhD Thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

- Dwyer, M. B. 2015. “The Formalization fix? Land Titling, Land Concessions and the Politics of Spatial Transparency in Cambodia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (5): 903–928. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.994510.

- Easterling, K. 2014. Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London and New York: Verso.

- Eilenberg, M. 2014. “Frontier Constellations: Agrarian Expansion and Sovereignty on the Indonesian-Malaysian Border.” Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (2): 157–182.

- Emel, J., M. T. Huber, and M. H. Makene. 2011. “Extracting Sovereignty: Capital, Territory, and Gold Mining in Tanzania.” Political Geography 30 (2): 70–79.

- Eriksen, S. H., A. J. Nightingale, and H. Eakin. 2015. “Reframing Adaptation: The Political Nature of Climate Change Adaptation.” Global Environmental Change 35: 523–533.

- Fairhead, J., M. Leach, and I. Scoones. 2012. “Green Grabbing: A New Appropriation of Nature?” Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (2): 237–261. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.671770.

- Ferguson, J. 2006. Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal World Order. Durham and London: Duke University.

- Foucault, M. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–78. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–79. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Glassman, J. 2010. Bounding the Mekong: The Asian Development Bank, China and Thailand. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i.

- Global Witness. 2015. The Cost of Luxury: Cambodia’s Illegal Trade in Precious Wood with China. London: Global Witness. https://www.globalwitness.org/campaigns/forests/cost-of-luxury/.

- Gupta, A., E. Lövbrand, E. Turhnout, and M. J. Vijge. 2012. “In Pursuit of Carbon Accountability: The Politics of REDD+ Measuring, Reporting and Verification Systems.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 4 (6): 756–731.

- Hagmann, T., and B. Korf. 2012. “Agamben in the Ogaden: Violence and Sovereignty in the Ethiopian–Somali Frontier.” Political Geography 31 (4): 205–214.

- Hall, D. 2012. “Rethinking Primitive Accumulation: Theoretical Tensions and Rural Southeast Asian Complexities.” Antipode 44 (4): 1188–1208.

- Hall, D., P. Hirsch, and T. M. Li. 2011. Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia. Singapore and Honolulu: National University of Singapore Press and University of Hawai'i Press.

- Harris, L. M. 2012. “State as Socionatural Effect: Variable and Emergent Geographies of the State in Southeastern Turkey.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 32 (1): 25–39.

- Harvey, P., and H. Knox. 2015. Roads: An Anthropology of Infrastructure and Expertise. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hensengerth, O. 2015. “Global Norms in Domestic Politics: Environmental Norm Contestation in Cambodia's Hydropower Sector.” The Pacific Review 28 (4): 505–528.

- Hensengerth, O. 2017. “Place Attachment and Community Resistance: Evidence from the Cheay Areng and Lower Sesan 2 Dams in Cambodia.” In Water Governance and Collective Action: Multi-scale Challenges, edited by D. Suhardiman, A. Nicol, and E. Mapedza, 58–69. Oxon and New York: Routledge/Earthscan.

- Hughes, C. 2009. Dependent Communities: Aid and Politics in Cambodia and East Timor. Ithaca: Cornell Southeast Asia Program.

- Hughes, C., and K. Un. 2011. “Cambodia’s Economic Transformation: Historical and Theoretical Frameworks.” In Cambodia’s Economic Transformation, edited by C. Hughes, and K. Un, 1–26. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Press.

- Humphrey, C. 2004. “Sovereignty.” In A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics, edited by D. Nugent, and J. Vincent, 418–436. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Hunsberger, C., E. Corbera, S. M. Borras Jr, J. C. Franco, K. Woods, C. Work, R. de la Rosa, et al. 2017. “Climate Change Mitigation, Land Grabbing and Conflict: Towards a Landscape-Based and Collaborative Action Research Agenda.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 38 (3): 305–324. doi:10.1080/02255189.2016.1250617.

- Hun Sen/CNV [Cambodia New Vision]. 28 December 2010. Selected Comments at the Groundbreaking of the Construction of Russei Jrum Hydropower. Cambodia New Vision, Cabinet of Prime Minister Hun Sen. Accessed 24 May 2015. http://cnv.org.kh/selected-comments-at-the-groundbreaking-of-the-construction-of-russei-jrum-hydropower-in-the-district-of-mondul-seima-koh-kong-province/.