ABSTRACT

The food crisis of 2007/8, alongside rapid population growth, and the uncertainties of climate change propelled African agricultural transformation back into the development mainstream. New narratives of ‘climate-smart agriculture’ and ‘sustainable intensification’ underlie this contemporary transformation. We present a political economy analysis of agricultural policy and livelihoods in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia, and use this to assess the challenge of achieving ‘sustainable and inclusive intensification’. We find little evidence that agricultural institutions have the capacity to deliver sustainable intensification in agriculture, or that agricultural policy drives changes in agricultural livelihoods that will make them either more sustainable or inclusive.

1. Introduction

The 2012 revision to the FAO World Agriculture Report predicted that if the world adopted agricultural intensification, in the form of increasing crop production and higher cropping intensities, there could be a 90% increase in global food production and that ‘world agriculture should face no major constraints to producing all the food needed for the population of the future, provided that the research/investment/policy requirements and the objective of sustainable intensification continue to be priorities’ (Alexandratos and Bruinsma Citation2012, 20). Such predictions undoubtedly render sustainable agriculture intensification (SI) as an ‘organising principle’ through which global food and climate change problems can be solved (FAO Citation2009a). Moreover, whilst the idea of intensification in agriculture is certainly mainstreamed and is now entrenched in the push for a second green revolution (Fairbairn et al. Citation2014; Snyder and Cullen Citation2014; Tittonell Citation2014; Vanlauwe et al. Citation2014; Mdee et al. Citation2019), this can mean a narrow focus on technical interventions to increase production, and an unclear and contested relationship with the normative goal of ‘sustainability’.

This paper explores the gap between the compound and normative goal of ‘inclusive sustainable intensification’ and the actual practice of agricultural policy and livelihoods in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. Our argument is developed using a political economy analysis, to review relevant policies and recent research evidence from all three countries, triangulated through key informant interviews. Our starting point is the research question posed by the Policy for Equity in African Agriculture project, on sustainable intensificationFootnote1:

How can equity issues be best addressed in Sustainable Intensification approaches and policies to ensure the needs and interests of poorer smallholders, especially youth and women, are properly addressed?

2. The prospects for inclusive sustainable intensification

Sustainable intensification (SI) is a debated term, given the intensely slippery nature of ‘sustainability’ as a discursive and normative construct (Loos et al. Citation2014; Petersen and Snapp Citation2015). For Pretty, Toulmin, and Williams (Citation2011, 7)

… .. it is defined as producing more output from the same area of land while reducing the negative environmental impacts and at the same time increasing contributions to natural capital and the flow of environmental services.

Agricultural intensification has been neither inevitable nor continuous in African farming systems. In some areas, intensification was halted or reversed by changing environmental or political and economic conditions; in others, it has occurred not as an adaptive response to population growth or commercialisation, but in the face of growing labour shortages and declining commercial activity. Such cases underscore the importance of studying farming as a dynamic social process. As farmers contend with social as well as environmental conditions, changes occur not only in what is produced and how much, but also in when work is done and by whom. Thus, changes in cropping patterns and methods of cultivation are influenced by social factors which govern the timing as well as the amounts of labour devoted to farming, as well as the control of effort and output.

The incentives, opportunities and obstacles for actors to promote (or discourage) agricultural intensification are related to both the political economy of development processes and a range of, often conflicting, national, regional and international policies and programmes. Institutional change processes and agricultural dynamics may lead to either inclusionary or exclusionary tendencies, e.g. small farmers may become landless if national policies favour agri-business investment (Vorley, Cotula, and Chan Citation2012; Tsikata Citation2016; Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata Citation2017; Chinsinga and Chasukwa Citation2018a; Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2018a, Citation2018b).

In addition, the adoption of inclusive sustainable intensification as a normative approach and outcome for agriculture in SSA would be subject to the agreement on such a vision by a multitude of different actors, with often competing interests and agendas. The barriers to this are obvious: donors remain confused about how to package, coordinate and deliver intervention to accelerate agriculture development (Mdee et al. Citation2019); and there are inconsistencies between global, regional and local policies on land governance and approaches to agriculture development (Chinsinga and Chasukwa Citation2012). Government budgetary spending and commitment to agriculture is rising but remains low in Africa (FAO Citation2009b, Citation2018); corporate investments are reproached for their unclear investment motives and destabilising relationship with smallholder farmers (Dubb, Scoones, and Woodhouse Citation2017) and smallholder farmers remain trapped in between the politics and dynamics of competing interests (Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2018a, Citation2018b). There is also little agreement from mainstream development partners on what sustainable agriculture looks like (Mdee et al. Citation2019). The contradictions among actors involved in agriculture development have historical origins hence it is important to understand the foundation of current agricultural policies in colonial regimes.

It is suggested that development partners and governments have a responsibility to create an enabling context of macro policy that could support inclusive and sustainable agricultural intensification (Pretty, Toulmin, and Williams Citation2011). In sub-Saharan African at a more meso-level, sub-national agricultural institutions and actors (including extension services, farmer organisations, traders, investors in contract farming, input suppliers and local authorities who control land tenure systems) are some of the most important mediators that determine the extent to which agricultural policies contribute to inclusivity and sustainability in existing agricultural dynamics. The resources and capabilities present at the meso-level have a critical role in enabling policy and strategy to be implemented and where resource and capability gaps are present, then the gap between stated policy and practice can be wide (Andrews, Pritchett, and Woolcock Citation2013; Mdee and Harrison Citation2019). At the micro level, farmers operate in a space in which they implement livelihood strategies in a context shaped by formal institutions, but also through more socially embedded customary arrangements (Harrison and Mdee Citation2017b).

It is apparent that the visibility of small-scale ‘peasant’ farmers in either colonial or post-colonial visions for agricultural transformation in Africa has been limited, presenting them as a problem to be solved, or a resource to be exploited (Birner and Resnick Citation2010). Birner and Resnick’s (Citation2010) comparative political economy of agriculture policies in Africa and Asia argues that transformation of smallholder agriculture is not the focus of agricultural policy in SSA, despite their dominance in the agricultural sector, given the policy maker's preference for ‘modernised’ and commercial agriculture. However, large agriculture-dependent populations also need to be politically manipulated where democratic elections have been adopted (Bates and Block Citation2009) and where public spending on staple crops permeates political dynamics. This is pronounced in many subsidy programmes (Chirwa and Chinsinga Citation2012). We are conscious that there is an extensive literature on rural development and transformation, particularly relating to class formation and differentiation (for example Bernstein Citation2016), but focus our attention in this article on contemporary agricultural policy dynamics and capacity for implementation.

To what extent is it likely that this wide range of actors and interests will align on the normative goal of ISI? A critical examination of the literature on the political economy of agriculture in SSA suggests that this outcome is unlikely. In this section, we highlight three critical challenges to the normative goal of ISI: the scramble for ‘surplus’ land in Africa; the dominant narrative of agricultural modernisation/industrialisation and the politicisation of food crops; and the politics of identity in shaping the ‘inclusiveness’ of agricultural policy.

2.1. Challenge 1- the scramble for ‘surplus’ land

A narrative of agricultural intensification is frequently used as a justification to explain the motives behind large-scale land acquisition (LaSLA) in some sub-Saharan African countries by companies and external state interests (Engström and Hadju Citation2019). The argument is that such investment will ensure increased production, food security and wider agricultural transformation. Jayne, Chamberlin, and Headey (Citation2014) suggest that the 2008 world food price crisis propelled a concerted effort to transfer land from customary tenure to the state or private individuals who, it was assumed, would more effectively realise the production potential of the land to meet national and global food objectives. This technical narrative of efficiency, often obfuscates the politics of agriculture and land access in order to frame answers to the question of ‘who will make the best use of Africa’s land?’ (Manjengwa, Hanlon, and Smart Citation2014).

A counternarrative suggests that these investments pose challenges for smallholder farmers and the food security (Dell’Angelo et al. Citation2017; Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata Citation2017). Modern ‘land-grabs’ have historical precedents. Africa has been the target of large land acquisition and investment, especially during colonial periods. Past and present waves of land reallocations/acquisitions focus on customary or ‘unused’ lands (Doss, Summerfield, and Tsikata Citation2014; Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata Citation2017; Kuusaana Citation2017). Allocations of land to incoming investors (either foreign or local) are often predicated on the assumption that there is spare and unproductive land, while land demarcations and designations are contested terrains. There is evidence in all our focus countries that estimates of spare land are exaggerated, and that almost all land is subject to claims of one kind or another, be they from the state, settlements, individual landowners or land users (see Chinsinga and Chasukwa Citation2012; Sitko and Chamberlin Citation2016; Bluwstein et al. Citation2018).

Where the state seeks to invest in agricultural transformation through ‘modernisation’ of agriculture then this can favour the commercial and corporate investor, and local elites, who use their power and resources to dispossess others of their access to resources (see, for example, Tsikata Citation2016; Kuusaana Citation2017; Bluwstein et al. Citation2018). This is reflected in the observed increasing differentiation of agricultural livelihoods across Africa (Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata Citation2015; Andersson Djurfeldt and Hillbom Citation2016; Andersson Djurfeldt, Dzanku, and Isinika Citation2018). Current patterns suggest that this process may be driving a new wave of marginalisation and dispossession.

2.2. Challenge 2- the politics of agricultural ‘modernisation’

Agricultural policy in sub-Saharan Africa is dominated by a historical and aspirational narrative of ‘modernisation’, whereby peasant agriculture is subject to transformation through the consolidation of lands, and the application of ‘modern’ technologies and production methods, organised around the potential to generate export revenue (Scott Citation2002; Bernstein Citation2010). As already noted above, this drives policy design, which often does not specifically tackle the challenges of small-scale agriculture (Birner and Resnick Citation2010; Mdee et al. Citation2019). A refreshed drive towards ‘industrialisation’ in African government policy further reinforces this dominant policy narrative (Verdier-Chouchane Citation2017).

A critical difference is that a post-second world war discourse on agricultural industrialisation does not fit the contemporary context, in which industrial agriculture is recognised as a significant contributor to carbon emissions, and environmental degradation. Despite donor-driven and international finance incentives to adopt a ‘green’ industrial strategy, this as yet shows little sign of coherent operationalisation, beyond limited policy statements on the adoption of ‘climate-smart agriculture’, ‘sustainable intensification’ and ‘conservation agriculture’ (Arslan et al. Citation2015; Mdee et al. Citation2019). As noted above, there is little agreement on what sustainable intensification in agriculture is, and critics have argued that it actually represents a significantly contested terrain, in which influential corporate actors and technology-driven philanthropists (e.g. Gates Foundation) offer technical solutions with green outcomes (GMOs, drip irrigation, drones and GPS controlled pesticide application), whilst others rooted in a more critical position on food sovereignty argue for a more radical reconfiguration of global food chains in the interests of both producers and the environment (Pretty et al. Citation2010; Morvaridi Citation2016; Mdee et al. Citation2019). There is a growing evidence base that genuine sustainable agriculture (low input, agro-ecological systems) can deliver intensification and improved livelihoods (Pretty Citation2001, Citation2002, Citation2003; Altieri and Toledo Citation2011; Altieri, Funes-Monzote, and Petersen Citation2012; Rosset et al.Citation2011; Bennett and Franzel Citation2013; Nyantakyi-Frimpong et al. Citation2016; Khadse et al. Citation2018; Mdee et al. Citation2019). Yet, the barriers to agricultural policy being shaped by this evidence are significant (Isgren Citation2016). It runs counter to a deeply embedded and hegemonic policy rhetoric, where modernisation is equal to hybrid seeds, inorganic fertilisers, and large-scale mono-cropping (Engström and Hajdu Citation2019).

This policy rhetoric is built on a political economy of agriculture in which, the rural producers (as the backbone of the economy, and through democratisation as voters) can be embedded, controlled and exploited. In Zambia, for instance, Chapoto, Kabaghe, and Zulu-Mbata (Citation2015) observe how heightened public expenditure on agricultural subsidies often coincides with general elections.

Taxation and price controls were common strategies that enabled elite control in the sector in both colonial and post-colonial eras. Thus, the prevailing basis of agriculture policies focuses on the dominance of political elites at the expense of small-scale agricultural development (Poulton Citation2012).

More overtly, subsidies and support provided for farmers can also act as an indirect source of funds for campaigns and electoral strategies for winning rural votes (Banful Citation2011) and serving as quick means to compensate for a lack of longer-term investment in rural infrastructure (Dorward et al. Citation2009). It benefits governments to keep the price of food low for noisy and politically active urban populations, whilst also subsidising production for the populous rural voters. Subsidies to agricultural production are frequently subject to local elite capture in their allocation and may limit sustainability of intensification through decreasing cropping diversification, promoting the use of inorganic inputs and ignoring soil fertility in the long term (Jayne and Rashid Citation2013; Chapoto, Kabaghe, and Zulu-Mbata Citation2015).

2.3. Challenge 3- the seductive simplifications of identity-based inclusion

Finally, addressing inequality in agricultural policy is framed predominantly through an identity-labelling approach (e.g. women or youth or vulnerable groups such as people living with HIV/AIDS). We see this reflected in the question which underpins this paper, and of course, this is built on substantial foundations in international development policy (Doss et al. Citation2018). This is consistent with neo-liberal understandings of poverty that frame it as an individual problem resulting from identity-based disadvantage, rather than a more structural product of class relations, resource control and power. The net effect of this is that in the international development industry, and in the policies that they influence we see a tendency to tackle inclusion through identity-based labelling. Therefore, it is argued that ‘women’ or ‘youth’ require special attention in order for them to overcome disadvantage (Hickel Citation2014). This may take the form of women or youth specific projects or targeted inclusion in decision making. However, this approach has significant weakness in addressing structural disadvantages.

Women, more than youth, have been labelled either as cardboard victims or heroines (Cornwall Citation2016). Ironically, at a time when it is argued that patriarchal decision-making power is declining in rural households, giving way for women and youth to gain more decision-making power and economic autonomy (Bryceson Citation2009), broad brush assumptions in relation to gender still dominate agricultural policies (Okali Citation2012). Doss et al. (Citation2018) identify a number of dominant policy myths such as ‘women produce 60%–80% of food’. Whilst this statement is used to demonstrate the critical role women play in food production, they explain that these universalistic phrases, often based on patchy evidence, ignore the diversity of social and gender relations in agrarian households. Whilst such statements are widely accepted and propagated, they fail to create a meaningful change through the policies they inform (Okali Citation2012; Andersson Djurfeldt et al. Citation2018; Doss et al. Citation2018).

Without a more complex understanding of increasing differentiation within and between rural households, it is unlikely that policy will be able to respond to making agricultural intensification more inclusive (Doss, Summerfield, and Tsikata Citation2014; Tsikata Citation2016; Andersson Djurfeldt, Dzanku, and Isinika Citation2018).

This is not to say that gender and youth are not important factors in understanding inclusion and exclusion in agricultural livelihoods. However, they cannot be universalised and need to be understood as contributory and integrated into dynamics of differentiation, along with many other factors. Current evidence suggests a continued trend of increasing differentiation and class formation in agricultural dynamics (Jayne, Chamberlin, and Headey Citation2014). It is not enough to address this dynamic through identity-based intervention, rather state and political institutions have to address the consequences for those who are impacted negatively by current agricultural dynamics, such as those rendered landless (Snyder and Cullen Citation2014).

3. Assessing evidence for inclusive sustainable intensification in agricultural policy and livelihoods in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia

Political economy analysis aims to provide a reasoned explanation for how a current situation comes to be as it is, in addition to elucidating different actor’s strategies and motivations (Jerven Citation2014; Nyame and Grant Citation2014). The nature of institutions and how they shape change is particularly key to understanding how change happens, who influences it and to what outcomes it has led.

Our analysis is based on the triangulation of multiple secondary and primary data sources. We began with a literature review of evidence on agricultural policy and donor intervention in the case study countries, with the purpose of understanding the broad dynamics of agriculture and how these align with the notion of ISI. This was substantially informed by the previous work of the authors. Anna Mdee has conducted extensive field research on agricultural livelihoods and natural resources governance in multiple locations in Tanzania since 1996 (Toner Citation2003; Cleaver and Toner Citation2006; Harrison and Mdee Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Mdee Citation2017; Harrison and Mdee Citation2018; Mdee et al. Citation2019; Mdee and Harrison Citation2019; Brockington et al. Citation2019); Michael Chasukwa has researched and published on the political economy of agriculture and on local government capacity in Malawi since 2005 (Chinsinga and Chasukwa Citation2012, Citation2015, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Chinsinga, Chasukwa, and Zuka Citation2013), and Simon Manda has researched and published extensively on agriculture in Zambia, including a recent three year investigation of large scale land acquisition (Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2019). We also reviewed the AFRINT survey data for each of the countries and worked in close co-operation with senior researchers from AFRINT country teams.Footnote2 Additional primary data collection was undertaken from November 2017 to February 2018 for the purposes of triangulation. This consisted of key informant elite interviews with government ministries, universities, NGOs and development partners both at national and district levels and primary data and focus group discussions with farmers in each country.Footnote3 Full details on the background fieldwork are published in a series of detailed working papers under the Policy for Equity in African Agriculture project: https://sairla-africa.org/what-we-do/research/policy-for-equity-in-african-agriculture-afrint-iv/.

3.1. Dynamics of agriculture in Malawi, Zambia and Tanzania

Notwithstanding the specificity of the detailed context of each of these three cases and variations in terms of politics, socio-economic conditions and agriculture policies, it is possible to identify a set of common trends and themes. This section should be read in conjunction with which provides a synthesis of evidence on trends in agricultural policy and livelihoods.

Table 1. Dynamics of agricultural change in Malawi, Zambia and Tanzania.

All three countries share commonalities of colonial engagement, post-independence state-led agricultural investment, followed by structural adjustment and liberalisation, moving to a current concern with the ‘African green revolution’, large-scale commercial investment, and climate-smart agriculture. The discourse of agricultural modernisation is present in all three countries. Whilst these policy directions are heavily influenced by donors, the politics involved is complex. The aim of dominant political regimes of both colonial and post-colonial eras favours full-scale agricultural transformation, meaning the shift of labour from agriculture, and a concentration of land-holdings, through intensification and commercial investment; but this goal has remained elusive across the case study countries. Whereas the share of agriculture in GDP may be declining to variable degrees, small-scale agriculture remains highly significant in the livelihoods of most of the population (Manjengwa, Hanlon, and Smart Citation2014; Harrison and Mdee Citation2018). All three countries are experiencing large-scale land acquisition and increasing differentiation of rural wealth (Andersson Djurfeldt and Hillbom Citation2016; Chinsinga Citation2017; Chung Citation2017; Bluwstein et al. Citation2018). Whilst decentralisation shapes the governance agenda of all three governments, the process is incomplete, and local government support to agriculture is under-resourced and fragmented (O’Neil et al. Citation2014; Mdee, Tshomba, and Mushi Citation2017). Tanzania abolished ‘traditional authorities’, but they retain a central role in agricultural governance in Malawi and Zambia (Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2019).

Malawi, Zambia and Tanzania in this era of new green revolution have implemented state reforms through policy and donor-funded programmes geared towards accelerating modernisation and commercialisation of agriculture through Private-Public Partnership (PPP) approaches. In Tanzania, the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) Programme, an investment strategy under Kilimo Kwanza (Agriculture First) aims to focus investment and commercialisation of agriculture in the central zone. However this has created space for local elites and companies to accumulate land and prosper at the expense of vulnerable groups and small producers (Chung Citation2017; Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018; Engström and Hajdu Citation2019). Similar criticisms are made of large-scale land acquisitions and PPPs such as the Green Belt initiative in Malawi (Chinsinga Citation2017), and the farm block initiative and out-grower schemes in Zambia (Sitko and Jayne Citation2014; Matenga Citation2017). Land policy in all three cases has similarities of duality with customary or collective tenure sitting alongside more formal systems of individual ownership. Again, there is existing broad literature on this that supports our analysis, and this is further confirmed in fieldwork and is explored in the next section. There is some evidence in all three countries that differentiation in land holdings is growing, and that exploitation of customary land is being enabled by traditional and other local leaders (Peters Citation2013; Andersson Djurfeldt and Hillbom Citation2016; Chinsinga Citation2017; Matenga and Hichaambwa Citation2017; Bluwstein et al. Citation2018: Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2019).

The shape of the economy as a whole is critical to the agricultural sector. The three countries in our study all have a large population base who derive a considerable proportion of their livelihoods from agriculture. However, there are differences relating to the size of land holdings and the shape of the wider economy. In Zambia, the mining sector underpins significantly more urbanisation than in Malawi or Tanzania. However, wider economic growth in mining, tourism and construction has also driven urbanisation in Tanzania. Malawi remains dependent on agricultural production for export revenue. The poorest households in all three countries depend on rain-fed agriculture, but strategies of migration and family network remittances are critical to their livelihoods (Andersson Djurfeldt, Dzanku, and Isinika Citation2018).

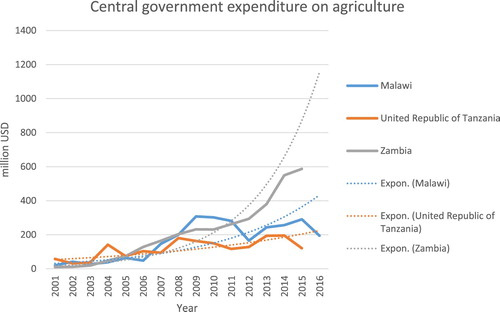

Malawi and Zambia both maintain high levels of state spending on input subsidies in the face of protracted donor opposition. These are politically important programmes and the focus of considerable debate, relating to their design, impact, and political capture (Sitko et al. Citation2017). For the past decade, FAO data has demonstrated increases, to different degrees, in central government expenditure in agriculture in all three countries (see ) which may partially relate to the adoption of the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP). Relative to government expenditures on sectors such as education and road infrastructure, spending on agriculture has not necessarily increased as a proportion of total government expenditure.

Figure 1. Trendline graph showing central government expenditure on agriculture in Malawi, Zambia and Tanzania (FAOSTAT data, 2018).

Gender and youth as categories of inclusion are present in the form of ‘policy noise’, workshops, committee quotas (very common in Tanzania) and groups. However, in all three cases, the greatest frontier of differentiation and exclusion appears to be class-based, within which gender and youth as categories also have some (but differentiated) significance.

In all three countries, donor and NGO intervention in agriculture is seen as confused, contradictory, driving elite capture, and supporting corruption. This view is repeatedly emphasised by elite interviewees in all sectors (government, NGOs and private). In Zambia, for example, this manifests itself in poor coordination of large-scale foreign investments in agriculture. This highlights a gulf between policy in theory and implementation capacity in practice. Analysis using the wider literature on local service delivery and governance underlines this case (e.g. Mdee, Tshomba, and Mushi Citation2017 on Tanzania). All three countries exhibit a critical lack of implementation capacity in local government support to agriculture and are forced to attempt ‘gap-filling’ through donor-funded projects. The outcome of this is an ad-hoc short term and fragmented approach that does not support longer term institutional capacity development. This is emphasised in elite interviews and reconfirmed in fieldwork at district levels. For example, in Malawi, a key informant at the local council made the observation: ‘we do not get enough resources from central government. The only way for us to be visible on the ground is to accept being involved in projects implemented by NGOs. We go by what they want us to do because it is a project’.Footnote4

Our research shows that irrigation development is seen as a critical component of agricultural modernisation. This again reflects government (with donor support) priorities of encouraging public-private investment in irrigation infrastructure – though state-led expansion remains slow (Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2019), farmer-led irrigation is expanding rapidly (Mdee and Harrison Citation2019). There is inadequate implementation capacity (even where there are comprehensive policy frameworks) for managing contested water use, and water scarcity is a growing concern (Harrison and Chiroro Citation2017; Harrison and Mdee Citation2018).

In Malawi and Zambia, state subsidy and market controls have significant impacts on driving maize production, although both countries are attempting to diversify their schemes (Hanjra and Culas Citation2011; Mpesi and Muriaas Citation2012; Mason, Jayne, and Mofya-Mukuka Citation2013). In Tanzania, the government subsidises maize through an input voucher, but on a much smaller scale (Gabagambi, Mkangwa, and Kadeng ‘uka Citation2015). It does intervene through the setting of tariffs and import/export bans on particular goods. These can be erratic and have significant impacts on markets in some cases, and we will explore this further below.

Evidence in all three countries suggests that access to reliable and fair markets remains a challenge for small farmers, even when they successfully increase their production (Chirwa and Chinsinga Citation2012; Matenga and Hichaambwa Citation2017; Harrison and Mdee Citation2017b).

From our analysis in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia, we identify three key challenges that will need to be addressed if inclusive sustainable intensification is to be achieved: 1. Closing the gap between policy in theory and policy implementation in practice. 2. Addressing the role of maize and agricultural subsidies, and 3. Addressing the dynamics of elite capture in land and water acquisition.

3.2. The policy-practice gap

Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia have extensive policy frameworks relating to agriculture and related areas – such as irrigation, climate change, gender, etc. With donor focus on ‘good governance’-driven institutional change over the last decade, considerable resources and incentives have been in place to create policy and make ‘policy noise’. There is significant evidence of ‘isomorphic mimicry’ in creating a policy architecture that has the appearance of reform, without having the capability and capacity to implement extensive change (Andrews, Pritchett, and Woolcock Citation2013; Mdee and Harrison Citation2019).

How things work in practice is different from the neat intentions set out in policies. The reasons for this are multiple – relating to the creation of policy in vacuums in central government and elite levels, the hierarchical tendencies of government bureaucracy, the practical politics of power and patronage, and significant resource constraints (see Mdee, Tshomba, and Mushi Citation2017 for a detailed exploration of this in the Tanzanian context). In Zambia, recent evidence shows that ‘whilst possibilities for LaSLAs are created by state institutions, the state agencies seeking to administer land-based resources also limit their potential through competing authority and agendas’ (Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2019, 194).

An academic interviewee in Malawi also illustrates this issue:

The National Agricultural policy processes demonstrate that policies in Malawi involve multiple stakeholders, multiple arenas and multiple levels. This has significant implications for the level of coordination and coherence required to achieve the desired goals and objectives of any policy process. The level of complexity varies depending on the nature of the specific policy. The challenges demonstrate that policy and policy-making is conditioned and shaped by the political, social and economic context, as well as historical factors. It is also important to note that there is a lack of an internal sense of urgency to systematically address policy challenges within the government. This implies that the government is not proactive when it comes to initiating processes leading to the development of relevant policy documents. Almost always, policy processes are a reaction to international pressures and implemented on a project basis. Ministry or departmental led policy processes can be overshadowed by politically orientated policy pronouncements. There is often a sense of urgency to do something about these policy pronouncements since they may relate to political profiles for electoral purposes and are, usually, at the expense of other equally pressing policy processes and priorities. (Key informant Interview-Malawi 2018)

Aid is weakening everybody- we need to kick out the donors. There is so little capacity to implement the policies that are designed by them. In the end, the Districts just rely on NGOs to do anything. (Key informant interview, Malawi 2018)

3.3. The politics of maize

In all three countries, maize remains a key staple food crop for both urban and rural dwellers, and thus is politically significant. The elevation of crops such as maize into a political food crop is predominant in Malawi and Zambia and presents itself as a form of social contract between the government and citizens (Banful Citation2011; Hanjra and Culas Citation2011; Mpesi and Muriaas Citation2012; Jayne and Rashid Citation2013; Chinsinga and Poulton Citation2014; Kato and Greeley Citation2016; Morgan et al. Citation2019). The dominant political narrative is that adequate maize availability translates into food security. These forms of social contract limit the government’s spending on other food crops and broader agricultural transformation initiatives and are fulfilled by the government in the form of inputs subsidy programmes and policies, consumer and producer price controls and marketing strategies, and these have significant impacts on farmers’ crop choice and production practice. Morgan et al. (Citation2019) confirm our findings that such subsidies disincentivise production methods associated with sustainable intensification.

In Malawi, key informant interviews confirmed that not only are policy programmes like the Farmer Inputs Subsidy Program (FISP) problematic and subject to political manipulation, but they are also trapping smallholder farmers in maize production. Moreover, when the government establishes a parastatal agency that purchases a single food crop for farmers, it demonstrates the level of importance of the crop relative to other crops. In Zambia, the Food Reserve Agency (FRA) and FISP budgets dominate other agricultural expenditure in the country (Jayne and Rashid Citation2013). FRA purchases maize from farmers above the current market/privatized wholesale prices and deposits maize purchased into commercial mills. In Tanzania, the use of input subsidies is less extensive than Malawi and Zambia, however it is noted that the National Agriculture Input Voucher System (NAIVS) was subject to political demands for extension to certain strategic locations of the country (Gabagambi, Mkangwa, and Kadeng ‘uka Citation2015).

Hence, whilst providing input subsidies for maize might target crop productivity improvement, it also creates political and financial incentives for farmers to keep producing maize with inorganic inputs, (NPK fertilisers), for governments to manipulate rural voters, and for fertiliser importers and agro-business dealers to benefit from government contracts (Jayne and Rashid Citation2013). Additionally, there are potentially negative consequences of increasing the vulnerability of smallholder production to droughts and pests, and lowering the resilience of production systems (Morgan et al. Citation2019). In Zambia, the culture of defining agriculture in terms of maize production has been identified as stifling wider efforts towards diversification and market participation among local farmers (Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2019). Similarly, the narrative among citizens in Malawi that ‘food security is maize availability’Footnote5 leads political authorities to concentrate on promoting maize to resonate well with the electorate. It is evident, thus, that the these narrow subsidy programmes can frustrate efforts for crop diversification and climate change adaptation interventions (Chinsinga and Poulton Citation2014).

Key informants in all the three countries suggest that local agro-dealers deliberately do not stock diverse inputs because they are not profitable (confirmed in multiple interviews in 2018). An expert on agricultural subsidy in Malawi argued that the subsidy programme design assumes that agro-dealers should provide a comprehensive agricultural support system to farmers, including the provision of extension services and through supplying a range of agricultural inputs. However, in practice this has turned out to be impossible because of commercialisation of subsidy programmes and the temporary nature of agro-dealers – with most emerging opportunistically at the start of subsidy programme and closing the business at the end of the subsidy period. Furthermore, smallholder farmers in hard-to-reach areas are under-served because agro-dealers do not find any business justification to operate in less lucrative areas (see also Andersson Djurfeldt, Dzanku, and Isinika Citation2018). In these difficult-to-reach areas, people maybe systematically excluded because they are unable to walk long distances to buy farm inputs even if they have vouchers. At the District levels, agricultural extensions officers observed that it is also difficult for government to regulate agro-dealers and other suppliers because some are politically connected and represent interests of elites and political powers, and farmers are often at risk of purchasing fake inputs. Therefore whilst subsidy programmes may be nationwide in design, in practice they tend to focus on areas of commercial and political significance.

Without explicit recognition of the political incentives and economic interests that drive subsidy programmes it is difficult to see how governments will shift their focus from these programmes as their major form of intervention in agricultural livelihoods. It is conceivable that such programmes are redesigned to incentivise practices associated with ISI, but that will require political will.

3.4. Dynamics of differentiation

There is some evidence from our literature review, and supported through key informant interviews in all three countries, that differentiation in land holdings is growing, and that exploitation and appropriation of customary or collectively managed land is being enabled by ‘traditional’ and other local leaders (Peters Citation2013; Sitko and Jayne Citation2014; Sitko and Chamberlin Citation2016; Bluwstein et al. Citation2018; Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018; Chinsinga and Chasukwa Citation2018a). Moreover, there is evidence of elite capture in both land allocations and agricultural subsidy schemes. The formal systems (such as the distribution of vouchers or selection of recipients for subsidy) interact with the more informal systems of power. Elites should not be thought of only as the top political and business elite, but include the relatively wealthy and more powerful in a local setting. Elite capture contributes to class differentiation, as those with connections to powerholders access opportunities for subsidy, capital accumulation and investment (Mdee and Harrison Citation2019).

Initiatives seeking inclusion of ‘women’ or ‘youth’ should be understood against this background. It cannot be assumed that institutional arrangements are uniformly discriminatory in relation to gender and generation. Such social relations are dynamic and shifting, for example in relation to the shape of the wider economy, e.g. if there are significant waged labour opportunities that can enable men to migrate. The burden of those who take responsibility for domestic reproduction much greater where the state does not ensure the provision of basic services, and therefore gendering of labour must be understood in the wider context of the nature of the economy and class differentiation (Fakier and Cock Citation2018).

Debates on inclusivity in agriculture often focus on rights to land and accessibility of inputs for individuals. Many of the NGOs interviewed in this research are targeting input and productive interventions at women, using a rhetorical narrative of mainstreaming gender. Much of the research under this theme disaggregates agricultural production and practice based on the sex of the ‘household’ head or ‘plot manager’ (Andersson Djurfeldt et al. Citation2018). Surveys often assume that the household exists as a formation of one unit per dwelling. Rather, households are rather more diverse networks of kin and familial relations with various configurations of resource flows (Brockington et al. Citation2019). Farming is more usually a collective undertaking, with a wide range of diverse intra-familial arrangements for deciding how to go about this and how to share the benefits. In some parts of Malawi, land inheritance is patrilineal, in other areas matrilineal (see Peters Citation1997 for example) but such classifications also shift and change. Simply giving individual women title to land, or access, to inputs cannot be transformational to unequal gender relations (see also Andersson Djurfeldt et al. Citation2018). Historical literature suggests that colonial regimes introduced the gender and property norms of the Victorian United Kingdom along with the capitalist mode of production, and that these then overlaid a multiplicity of customary arrangements to shape the current landscape of social relations (Mandala Citation1984; Peters Citation1997). Therefore, gender relations and inclusion are far more complex than the standard government and donor discourse allows, as is asserted here in a key informant interview with an NGO manager:

My experience is that when we talk about mainstreaming youth and gender, we have to unpack these concepts. Representation does not become true mainstreaming. What do numbers tell us? We have to understand issues of access and control – can our monitoring really pick this up? Women will tell us in interviews that their husbands make the decisions, even if that is not the case. That is what they think that they should say (Interview, NGO Programme Officer, Malawi January 2018).

However, key informants in all three countries suggested that the more powerful drivers of differentiation and inequality are to be found in patterns of land acquisitions, market access and unstable prices, unequal market inclusion leading to shortage of credit or debt traps and lack of alternative off-farm employment (Manda, Dougill, and Tallontire Citation2019).

4. Discussion and conclusion

Our analysis suggests that the normative goal of inclusive sustainable intensification in agriculture is somewhat divorced from current realities of agricultural policy and practice in Tanzania, Malawi and Zambia.

Firstly, the capacity of governments and local institutions to deliver coherent and multiple policies that ISI will require is highly doubtful. There is a very large gap between policy commitments on paper and the capacity of local institutions to deliver. There is no clear agreement on what characterises inclusive and sustainable agricultural production, and little evidence of coherent or sustained policy implementation to that affect, outside of donor or NGO funded projects. Agricultural policy remains dominated by a narrative of technology-driven modernisation and commercialisation, but evidence of a sustained advance towards that outcome is also limited. Agricultural subsidies are critical components of this landscape and currently create incentives for maize production in particular, and disincentivise the adoption of sustainable practices in agriculture (see Morgan et al. Citation2019). They also link symbiotically to the dynamics of rural politics and elections.

Secondly, our strongest conclusion is that agriculture is becoming less inclusive. This is being driven by the possibilities for elite capture in state subsidies, an increasing ‘middle’ class and elite accumulation of land, as well as donor-corporate-government alliances favouring large-scale land acquisitions. A renewed policy rhetoric on industrialisation might assume that the small farmer becomes a labour reserve for new industry, but there is little sign of new industries to fulfil this role.

There appears to be a failure of policy at multiple scales: at the global level policies of sustainable intensification are framed by a vague understanding of environment and agricultural production in a way which few can question on normative grounds. Who can possibly be opposed to a policy of sustainable, inclusive, intensification? This policy rhetoric then interacts with national and local political dynamics which, coupled with limited implementation capacity, produces an environment that favours local elite resource accumulation, and at the same time also encourages the entry of a multitude of donor-funded actors to compensate for the shortfall in state implementation capacity, creating a fragmented mess of donor-driven interventions.

Where agricultural intervention does exist, then elite capture at all levels is a frequent issue, as is illustrated in the example of the Farm Input Subsidy Programme (FISP) of Zambia. Traditional Authorities and resource allocation committees are frequent sites of elite capture and potential exploitation. Elite capture may have a gender dimension but requires explicit consideration of class. This also applies fundamentally to land policy, where land titling and formalisation may have made it easier for the poorest farmers to be dispossessed of land. A poorer man is very much more disadvantaged than a wealthier woman in this regard.

Policy frameworks are dominated by an aid-driven donor discourse. State investment in agriculture remains limited. Private finance is unaffordable to the small farmer and out-grower schemes have disappointed many of those involved. Elite and commercial interests are favoured in legal frameworks and in the normal business of institutional actors. Markets remain exploitative, hard to access, and unreliable for the small farmer. Exploitation and dispossession of resources are the dominant trends. These trends run entirely counter to the notion of inclusive sustainable intensification, and significant political will be required to reverse them. The dynamics of agriculture in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia are currently neither sustainable nor inclusive.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Agnes Andersson Djurfeldt for her insightful comments during the preparation of this paper, and to the two anonymous reviews for their guidance in shaping the final paper. We would also like to thank Gasper Mdee, Darlen Dzimwe and Royd Malisase for their assistance and insights during the fieldwork. This paper draws on a set of working papers produced for the Policies for Equity in African Agriculture Project, led by Lund University and funded by the UK Department for International Development. However this paper represents the views of the authors alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Mdee

Anna Mdee is Professor in the Politics of Global Development at the University of Leeds. She is an anthropologist who has worked on agricultural livelihoods and local governance in Tanzania since 1996. She is also Associate Director of water@leeds and has a particular interest in the politics of irrigation in the transformation of agriculture in Tanzania.

Alesia Ofori

Alesia Ofori Dedaa is currently a PhD student at the School of Politics and International Studies at the University of Leeds. Her PhD research seeks to excavate some of the complex political issues around the nexus between mineral exploration and community water supply, access and distribution in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Ghana. Alesia’s research interests encompass rural governance and development, agrarian change and the political ecology of waterscapes.

Michael Chasukwa

Michael Chasukwa is a Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of Political and Administrative Studies, Chancellor College, University of Malawi. He obtained his doctorate in development studies from the University of Leeds, United Kingdom. He has published in various journals including the International Journal of Public Administration, Agrarian South: the Journal of Political Economy, Insights on Africa, Journal of Development Effectiveness, Africa Review, and Journal of Asian and African Studies.

Simon Manda

Simon Manda is a Lecturer at the University of Zambia Department of Development Studies. He holds a PhD in Environment and Development and an MA in Global Development from University of Leeds, UK. He also holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Development Studies from the University of Zambia. His current research focuses on labour migration in agriculture.

Notes

1 The project is funded by the UK Department for International Development under the programme Sustainable Agricultural Intensification Research and Learning in Africa (SAIRLA) https://sairla-africa.org/. The Policy for Equity in African Agriculture project is led by Lund University under the AFRINT project https://www.keg.lu.se/en/research/research-projects/current-research-projects/afrint.

2 AFRINT is a multi-country longitudal study of agricultural dynamics in 8 African countries, based on household surveys: https://www.keg.lu.se/en/research/research-projects/current-research-projects/afrint.

3 20–30 key informant interviews were conducted in each country – purposively sampled to cover the perspectives of government ministries, agricultural extension workers, local, nation and international NGOs, development partners (inc World Bank and faith-based organisations). Numbers of focus groups varied by country and in relation to existing data sets. Focus groups differentiated participants by gender and were used to do a cross check on the themes emerging from key informant interviews.

4 Key informant interview, Dedza, Malawi.

5 Key informant, Mulanje District Council.

References

- Alexandratos, N., and J. Bruinsma. 2012. “The 2012 Revision World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision (No. 12). Rome. www.fao.org/economic/esa.

- Altieri, M., F. Funes-Monzote, and P. Petersen. 2012. “Agroecologically Efficient Agricultural Systems for Smallholder Farmers: Contributions to Food Sovereignty.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development 32 (1): 1–13.

- Altieri, M., and V. Toledo. 2011. “The Agroecological Revolution in Latin America: Rescuing Nature, Ensuring Food Sovereignty and Empowering Peasants.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (3): 587–612. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.582947.

- Andersson Djurfeldt, A., F. M. Dzanku, and A. Isinika, eds. 2018. Agriculture, Diversification and Gender in Rural Africa: Longitudinal Perspectives from Six Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Andersson Djurfeldt, A., and E. Hillbom. 2016. “Pro-poor Agricultural Growth–Inclusion or Differentiation? Village Level Perspectives from Zambia.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 75: 220–233.

- Andersson Djurfeldt, A., E. Hillbom, W. Mulwafu, P. Mvula, and G. Djurfeldt. 2018. “‘The Family Farms Together, The Decisions, However are Made by the Man’—Matrilineal Land Tenure Systems, Welfare and Decision Making in Rural Malawi.” Land Use Policy 70: 601–610.

- Andrews, M., L. Pritchett, and M. Woolcock. 2013. “Escaping Capability Traps Through Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA).” World Development 51: 234–244.

- Arslan, A., N. McCarthy, L. Lipper, S. Asfaw, A. Cattaneo, and M. Kokwe. 2015. “Climate Smart Agriculture? Assessing the Adaptation Implications in Zambia.” Journal of Agricultural Economics 66 (3): 753–780.

- Banful, A. 2011. “Old Problems in the New Solutions? Politically Motivated Allocation of Programme Benefits and the ‘New’ Fertilizer Subsidies’.” World Development 39 (7): 1166–1176.

- Bates, R., and S. Block. 2009. “Political Economy of Agricultural Trade Interventions in Africa.” Agricultural Distortions Working Paper 87. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/3322469/bates_block_87rev.pdf?sequence=2.

- Bennett, M., and S. Franzel. 2013. “Can Organic and Resource-conserving Agriculture Amprove Livelihoods? A Synthesis.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 11 (3): 193–215.

- Bernard, B., and A. Lux. 2017. “How to Feed the World Sustainably: An Overview of the Discourse on Agroecology and Sustainable Intensification.” Regional Environmental Change 17 (5): 1279–1290. doi:10.1007/s10113-016-1027-y.

- Bernstein, H. 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. 1 vol. Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press.

- Bernstein, H. 2016. “Agrarian Political Economy and Modern World Capitalism: The Contributions of Food Regime Analysis.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (3): 611–647.

- Berry, S. 1993. No Condition is Permanent: The Social Dynamics of Agrarian Change in Sub- Saharan Africa. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Béné, C., P. Oosterveer, L. Lamotte, I. Brouwer, S. de Haan, S. Prager, E. Talsma, and C. Khoury. 2019. “When Food Systems Meet Sustainability–Current Narratives and Implications for Actions.” World Development 113: 116–130.

- Birner, R., and D. Resnick. 2010. “The Political Economy of Policies for Smallholder Agriculture.” World Development 38 (10): 1442–1452.

- Bluwstein, J., J. Lund, K. Askew, H. Stein, C. Noe, R. Odgaard, F. Maganga, and L. Engström. 2018. “Between Dependence and Deprivation: The Interlocking Nature of Land Alienation in Tanzania.” Journal of Agrarian Change 18 (4): 806–830.

- Boserup, E. 1965. The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure. New York: Aldine Publishing Company.

- Brockington, D., E. Coast, A. Mdee, O. Howland, and S. Randall. 2019. “Assets and Domestic Units: Methodological Challenges for Longitudinal Studies in Poverty Dynamics.” The Journal of Peasant Studies. doi:10.1080/03066150.2019.1658079.

- Bryceson, D. 2009. “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Vanishing Peasantries and the Spectre of a Global Food Crisis.” Monthly Review 61 (3): 48–62.

- Chapoto, A., C. Kabaghe, and O. Zulu-Mbata. 2015. “The Politics of the Maize Sector in Zambia.” In Agriculture in Zambia: Past, Present, and Future, edited by A. Chapoto and N. J. Sitko, 37–49. Lusaka, Zambia: IAPRI.

- Chinsinga, B. 2017. “The Green Belt Initiative, Politics and Sugar Production in Malawi: Investigating the Contribution of Limphasa Sugar Corporation to Rural Development.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 26 (6): 1065–1084.

- Chinsinga, B., and M. Chasukwa. 2012. “Youth, Agriculture and Land Grabs in Malawi.” IDS Bulletin 43 (6): 67–77.

- Chinsinga, B., and M. Chasukwa. 2015. “Trapped between Fertiliser Input Subsidy Programme and Green Belt Initiative: An Audit of Contemporary Malawian Agrarian Political Economy.” In Africa’s Land Rush: Rural Livelihoods and Agrarian Change, edited by R. Hall, I. Scoones, and D. Tsikata, 132–149. Oxford: James Currey.

- Chinsinga, B., and M. Chasukwa. 2018a. “Agricultural Policy, Employment Opportunities and Social Mobility in Rural Malawi.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 7 (1): 28–50.

- Chinsinga, B., and M. Chasukwa. 2018b. “Narratives, Climate Change and Agricultural Policy Processes in Malawi.” Africa Review 10 (2): 140–156.

- Chinsinga, B., M. Chasukwa, and S. Zuka. 2013. “The Political Economy of Land Grabs in Malawi: Investigating the Contribution of Limphasa Sugar Corporation to Rural Development in Malawi.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 26: 1065–1084.

- Chinsinga, B., and C. Poulton. 2014. “Beyond Technocratic Debates: The Significance and Transience of Political Incentives in the Malawi Farm Input Subsidy Programme (FISP).” Development Policy Review 32 (s2): s123–s150.

- Chirwa, E., and B. Chinsinga. 2012. The Political Economy of Food Price Policy: A Case of Malawi’. A Draft Working Paper for WIDER. Zomba: Chancellor College, University of Malawi.

- Chung, Y. 2017. “Engendering the New Enclosures: Development, Involuntary Resettlement and the Struggles for Social Reproduction in Coastal Tanzania.” Development and Change 48 (1): 98–120.

- Cleaver, F., and A. Toner. 2006. “The Evolution of Community Water Governance in Uchira, Tanzania: The Implications for Equality of Access, Sustainability and Effectiveness.” Natural Resources Forum 30 (3): 207–218. doi:10.1111/j.1477-8947.2006.00115.x.

- Cornwall, A. 2016. “Women’s Empowerment: What Works?” Journal of International Development 28: 342–359. doi:10.1002/jid.

- Dell’Angelo, J., P. D’Odorico, M. Rulli, and P. Marchand. 2017. “The Tragedy of the Grabbed Commons: Coercion and Dispossession in the Global Land Rush.” World Development 92: 1–12.

- Dorward, A., J. Kydd, C. Poulton, and D. Bezemer. 2009. “Coordination Risk and Cost Impacts on Economic Development in Poor Rural Areas.” The Journal of Development Studies 45 (7): 1093–1112.

- Doss, C., R. Meinzen-Dick, A. Quisumbing, and S. Theis. 2018. Women in Agriculture : Four Myths. Global Food Security 16, July 2017: 69–74.

- Doss, C., G. Summerfield, and D. Tsikata. 2014. “Land, Gender, and Food Security.” Feminist Economics 20 (1): 1–23.

- Dubb, A., I. Scoones, and P. Woodhouse. 2017. “The Political Economy of Sugar in Southern Africa - Introduction.” Journal of Southern African Studies 43 (3): 447–470. doi:10.1080/03057070.2016.1214020.

- Engström, L., and F. Hajdu. 2019. “Conjuring ‘Win-World’–Resilient Development Narratives in a Large-Scale Agro-investment in Tanzania.” The Journal of Development Studies 55 (6): 1201–1220.

- Fairbairn, M., J. Fox, S. Isakson, M. Levien, N. Peluso, S. Razavi, I. Scoones, and K. Sivaramakrishnan. 2014. “Introduction: New Directions in Agrarian Political Economy.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (5): 653–666.

- Fakier, K., and J. Cock. 2018. “Eco-feminist Organizing in South Africa: Reflections on the Feminist Table.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 29 (1): 40–57.

- FAO. 2009a. World Summit on Food Security. Rome. www.lisd.ca/ymb/food/wsfs2009/html/%0Aymbvol150num7e.html.

- FAO. 2009b. “Rapid Assessment of Aid Flows for Agricultural Development in Sub-Saharan Africa.” http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/tci/pdf/SSAAid09.pdf.

- FAO. 2018. “Government Expenditure on Agriculture.” http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/investment/expenditure/en/.

- Gabagambi, D., C. Mkangwa, and L. Kadeng ‘uka. 2015. “Electronic Smart Subsidies in Agriculture for Food Security in Tanzania.” Conference on International Research on Food Security. http://www.tropentag.de/2015/abstracts/full/55.pdf.

- Garnett, T., M. Appleby, A. Balmford, I. Bateman, T. Benton, P. Bloomer, B. Burlingame, et al. 2013. “Sustainable Intensification in Agriculture: Premises and Policies.” Science 341, July: 33–34. doi:10.1126/science.1234485.

- Garnett, T., and H. Godfray. 2012. Sustainable Intensification in Agriculture. Navigating a Course Through Competing Food System Priorities. Oxford: University of Oxford. https://www.fcrn.org.uk/sites/default/files/SI_report_final.pdf.

- Hall, R., I. Scoones, and D. Tsikata, eds. 2015. Africa's Land Rush: Rural Livelihoods and Agrarian Change. Boydell and Brewer. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt16vj222.

- Hall, R., I. Scoones, and D. Tsikata. 2017. “Plantations, Outgrowers and Commercial Farming in Africa: Agricultural Commercialisation and Implications for Agrarian Change.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (3): 515–537.

- Hanjra, M., and R. Culas. 2011. “The Political Economy of Maize Production and Poverty Reduction in Zambia: Analysis of the Last 50 Years.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 46 (6): 546–566.

- Harrison, E., and C. Chiroro. 2017. “Differentiated Legitimacy, Differentiated Resilience: Beyond the Natural in ‘Natural Disasters’.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (5): 1022–1042.

- Harrison, E., and A. Mdee. 2017a. “Successful Small-Scale Irrigation or Environmental Destruction? The Political Ecology of Competing Claims on Water in the Uluguru Mountains, Tanzania.” Journal of Political Ecology 24 (1): 406–424. doi:10.2458/v24i1.20881.

- Harrison, E., and A. Mdee. 2017b. “Size isn’t Everything: Narratives of Scale and Viability in a Tanzanian Irrigation Scheme.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 55 (2): 251–273.

- Harrison, E., and A. Mdee. 2018. “Entrepreneurs, Investors and the State: The Public and the Private in sub-Saharan African Irrigation Development.” Third World Quarterly 39 (11): 2126–2141.

- Hickel, J. 2014. “The ‘Girl Effect’: Liberalism, Empowerment and the Contradictions of Development.” Third World Quarterly 35 (8): 1355–1373.

- Isgren, E. 2016. “No Quick Fixes: Four Interacting Constraints to Advancing Agroecology in Uganda.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 14 (4): 428–447.

- Jayne, T., J. Chamberlin, and D. Headey. 2014. “Land Pressures, the Evolution of Farming Systems and Development Strategies in Africa: A Synthesis.” Food Policy 48: 1–17.

- Jayne, T., and S. Rashid. 2013. “Input Subsidy Programs in sub-Saharan Africa: A Synthesis of Recent Evidence.” Agricultural Economics 44 (6): 547–562. doi:10.1111/agec.12073.

- Jerven, M. 2014. “The Political Economy of Agricultural Statistics and Input Subsidies: Evidence from India, Nigeria and Malawi.” Journal of Agrarian Change 14 (1): 129–145.

- Kato, T., and M. Greeley. 2016. “Agricultural Input Subsidies in Sub-Saharan Africa.” IDS Bulletin 47. doi:10.19088/1968-2016.130.

- Khadse, A., P. Rosset, H. Morales, and B. Ferguson. 2018. “Taking Agroecology to Scale: The Zero Budget Natural Farming Peasant Movement in Karnataka, India.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (1): 192–219. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1276450.

- Kuusaana, E. 2017. “Winners and Losers in Large-Scale Land Transactions in Ghana-opportunities for Win-Win Outcomes.” African Review of Economics and Finance 9 (1): 62–95.

- Loos, J., D. M. Chappell, J. Hanspach, F. Mikulcak, M. Tichit, and J. Fischer. 2014. “Putting Meaning Back into ‘Sustainable Intensification’.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12 (6): 356–361.

- Manda, S., A. Dougill, and A. Tallontire. 2018a. “Outgrower Schemes, Livelihoods and Response Pathways on the Zambian ‘Sugarbelt’.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 97: 119–130. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.021.

- Manda, S., A. Dougill, and A. Tallontire. 2018b. “Business ‘Power of Presence’: Foreign Capital, Industry Practices and Politics of Sustainable Development in Zambia.” Journal of Development Studies. doi:10.1080/00220388.2018.1554212.

- Manda, S., A. Dougill, and A. Tallontire. 2019. “Large-scale Land Acquisitions and Institutions: Patterns, Influence and Barriers in Zambia.” The Geographical Journal 185 (2): 194–208. doi:10.1111/geoj.12291.

- Mandala, E. 1984. “Capitalism, Kinship and Gender in the Lower Tchiri (Shire) Valley of Malawi, 1860–1960: An Alternative Theoretical Framework.” African Economic History 13: 137–169.

- Manjengwa, J., J. Hanlon, and T. Smart. 2014. “Who Will Make the ‘Best’ use of Africa’s Land? Lessons from Zimbabwe.” Third World Quarterly 35 (6): 980–995.

- Mason, N., T. Jayne, and R. Mofya-Mukuka. 2013. “Zambia’s Input Subsidy Programs.” Agricultural Economics 44 (6): 613–628.

- Matenga, C. 2017. “Outgrowers and Livelihoods: The Case of Magobbo Smallholder Block Farming in Mazabuka District in Zambia.” Journal of Southern African Studies 43 (3): 551–566.

- Matenga, C., and M. Hichaambwa. 2017. “Impacts of Land and Agricultural Commercialisation on Local Livelihoods in Zambia: Evidence from Three Models.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (3): 574–593.

- Mdee, A. 2017. “Disaggregating Orders of Water Scarcity-The Politics of Nexus in the Wami-Ruvu River Basin, Tanzania.” Water Alternatives 10 (1): 100–115. http://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol10/v10issue1/344-a10-1-6/file?auid=200.

- Mdee, A., and E. Harrison. 2019. “Critical Governance Problems for Farmer-Led Irrigation: Isomorphic Mimicry and Capability Traps.” Water Alternatives 12 (1): 30–45. http://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol12/v12issue1/477-a12-1-3/file.

- Mdee, A., P. Tshomba, and A. Mushi. 2017. “Holding Local Government to Account in Tanzania Through a Local Governance Performance Index.” Exploring lines of blame and accountability, Overseas Development Institute- Working paper, London. https://dl.orangedox.com/Mzumbe-WP3.

- Mdee, A., A. Wostry, A. Coulson, and J. Maro. 2019. “A Pathway to Inclusive Sustainable Intensification in Agriculture? Assessing Evidence on the Application of Agroecology in Tanzania.” Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 43 (2): 201–227. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1485126.

- Morgan, S., N. Mason, N. Levineand O, and O. Zulu-Mbata. 2019. “Dis-incentivizing Sustainable Intensification? The Case of Zambia’s Maize-Fertilizer Subsidy Program.” World Development 122: 54–69.

- Morvaridi, B. 2016. “Does sub-Saharan Africa Need Capitalist Philanthropy to Reduce Poverty and Achieve Food Security?” Review of African Political Economy 43 (147): 151–159. doi:10.1080/03056244.2016.1149807.

- Mpesi, A., and R. Muriaas. 2012. “Food Security as a Political Issue: The 2009 Elections in Malawi.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 30 (3): 377–393.

- Nyame, F., and J. Grant. 2014. “The Political Economy of Transitory Mining in Ghana: Understanding the Trajectories, Triumphs, and Tribulations of Artisanal and Small-scale Operators.” The Extractive Industries and Society 1 (1): 75–85. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2014.01.006.

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H., F. Mambulu, R. Kerr, I. Luginaah, and E. Lupafya. 2016. “Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems: Participatory Research to Improve Food Security Among HIV-affected Households in Northern Malawi.” Social Science and Medicine 164: 89–99.

- Okali, C. 2012. “Gender Analysis: Engaging with Rural Development and Agricultural Policy Processes.” Future Agriculture Consortium. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/.

- O’Neil, T., D. Cammack, E. Kanyongolo, M. Mkandawire, T. Mwalyambwire, B. Welham, and L. Wild. 2014. Fragmented Governance and Local Service Delivery in Malawi. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Peters, P. 1997. “Against the Odds: Matriliny, Land and Gender in the Shire Highlands of Malawi.” Critique of Anthropology 17 (2): 189–210.

- Peters, P. 2013. “Land Appropriation, Surplus People and a Battle Over Visions of Agrarian Futures in Africa.” Journal of Peasant Studies 40 (3): 537–562.

- Petersen, B., and S. Snapp. 2015. “What is Sustainable Intensification? Views from Experts.” Land Use Policy 46: 1–10.

- Poulton, C. 2012. “Democratisation and the Political Economy of Agricultural Policy in Africa.” Future Agricultures Working Paper 043. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/20548/1/FAC_Working_Paper_043.pdf.

- Pretty, J. 2001. “Policy and Practice. Policy Challenges and Priorities for Internalizing the Externalities of Modern Agriculture.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 44 (2): 263–283.

- Pretty, J. 2002. Agri-culture. Reconnecting People, Land and Nature. London: Earthscan.

- Pretty, J. 2003. “Agroecology in Developing Countries: The Promise of a Sustainable Harvest.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 45 (9): 8–20. doi:10.1080/00139150309604567.

- Pretty, J., W. Sutherland, J. Ashby, J. Auburn, D. Baulcombe, M. Bell, J. Bentley, et al. 2010. “The Top 100 Questions of Importance to the Future of Global Agriculture.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 8 (4): 219–236.

- Pretty, J., C. Toulmin, and S. Williams. 2011. “Sustainable Intensification in African Agriculture.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 9 (1): 5–24.

- Rasmussen, M., and C. Lund. 2018. “Reconfiguring Frontier Spaces: The Territorialization of Resource Control.” World Development 101: 388–399.

- Rosset, P., B. Sos, A. Roque Jaime, and D. Lozana. 2011. “The Campesino-to-Campesino Agroecology Movement of ANAP in Cuba: Social Process Methodology in the Construction of Sustainable Peasant Agriculture and Food Sovereignty.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (1): 161–191.

- Scott, G. 2002. “Zambia: Structural Adjustment, Rural Livelihoods and Sustainable Development.” Development Southern Africa 19 (3): 405–418.

- Sitko, N., and J. Chamberlin. 2016. “The Geography of Zambia’s Customary Land: Assessing the Prospects for Smallholder Development.” Land Use Policy 55 (2016): 49–60.

- Sitko, N., J. Chamberlin, B. Cunguara, M. Muyanga, and J. Mangisoni. 2017. “A Comparative Political Economic Analysis of Maize Sector Policies in Eastern and Southern Africa.” Food Policy 69: 243–255.

- Sitko, N., and T. Jayne. 2014. “Structural Transformation or Elite Land Capture? The Growth of ‘Emergent’ Farmers in Zambia.” Food Policy 48: 194–202.

- Snyder, K., and B. Cullen. 2014. “Implications of Sustainable Agricultural Intensification for Family Farming in Africa.” Anthropological Perspectives 20 (3): 9–29.

- Tittonell, P. 2014. “Ecological Intensification of Agriculture — Sustainable by Nature.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 8: 53–61. doi:10.1016/J.COSUST.2014.08.006.

- Toner, A. 2003. “Exploring Sustainable Livelihoods Approaches in Relation to two Interventions in Tanzania”. Journal of International Development 15 (6): 771–781. doi:10.1002/jid.1030.

- Tsikata, D. 2016. “Gender, Land Tenure and Agrarian Production Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 5 (1): 1–19.

- Vanlauwe, B., D. Coyne, J. Gockowski, S. Hauser, J. Huising, C. Masso, G. Nziguheba, M. Schutand, and P. Van Asten. 2014. “Sustainable Intensification and the African Smallholder Farmer.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 8 (0): 15–22.

- Verdier-Chouchane, A. 2017. “Introduction: Challenges to Africa’s Agricultural Transformation.” African Development Review 29 (2): 75–77.

- Vorley, B., L. Cotula, and M. Chan. 2012. “Tipping the Balance: Policies to Shape Agricultural Investments and Markets in Favour of Small-scale Farmers.” Oxfam Policy and Practice Private Sector 9 (2): 59–146.

- Wezel, A., G. Soboksa, S. McClelland, F. Delespesse, and A. Boissau. 2015. “The Blurred Boundaries of Ecological, Sustainable and Agroecological Intensification: A Review.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35 (4): 1283–1295. doi:10.1007/s13593-015-0333-y.