ABSTRACT

This paper examines agroecology within Europe, its dynamics, its position within a broader politico-economic framework and its political significance. It argues that agroecology is contesting and, at least in some places, effectively changing the main social relations of production in today’s agriculture. In this respect, it has a strategically important potential for allowing farmers to regain control over the labour process. Empirically, the paper builds on the case of the Northern Frisian Woodlands, a large territorial cooperative that, has been developing a range of agroecological practices, and (often successfully) advocating for their more widespread adoption.

1. Introduction

In Europe, agroecology represents, and is rooted in, a multitude of agricultural practices that, at first sight, seem to be merely agronomic and/or technical (and thus run the danger of being seen as irrelevant for critical agrarian studies (as defined by Edelman and Wolford Citation2017)). These practices have emerged as response to distortions in the process of agricultural production that arose as a consequence of increased dependency on external agents (the providers of inputs and technologies, banks, and processing industries) and/or as a response to the unequal distribution of value in agricultural supply chains to which farmersFootnote1 are subjected. Thus, these responses clearly have a politico-economic dimension, even if they are manifested through technical and organizational adaptations in, and of, agricultural production. Europe’s many agroecological practices are geographically highly dispersed and take many different forms (see van der Ploeg et al. Citation2019 for an overview), yet, taken together, they constitute a political struggle in which European peasants are seeking to regain control over their labour process.Footnote2 There are three distinctive and decisive dimensions to agriculture generally. The first concerns the socio-material organization of agricultural production (the material dimension); the second the social distribution of the wealth produced (the politico-economic dimension); and, the third, the ways in which peasants struggle to change both the production and distribution of wealth (the socio-political dimension).

This paper starts by providing a critical examination of the social relations of production within agriculture which, I believe, is helpful in bringing the many-sided, and radical, nature of agroecology to the fore. I will argue that agroecology is changing the social relations of production in agriculture. One of the implications of this is a reshuffling of the wealth produced and a regaining of control. I will also argue that the changes thus forged are not necessarily doomed to become conventionalized and that upscaling-without-conventionalization is not impossible, although it may prove difficult (see also Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho et al. Citation2018). One key to how these changes may layout is self-regulation at the territorial level.

This leads me to illustrate these arguments with a discussion of the Northern Frisian Woodlands, a territorial cooperative of farmers in the North of the Netherlands. I do not present this case as ‘proof’ of the theses forwarded in the theoretical sections of the paper. ‘Proving’ would require far more cases, thorough comparisons and inquiries into possible outliers. Such an endeavour would go far beyond the possibilities of this article. However, the presentation of this particular case can help, I think, to identify the relevance of politico-economic categories (as social relations of production, labour process, capital-labour relations, appropriation, etc.) in the analysis of today’s agriculture.

2. On the social relations of production

The social relations of production have two aspects: the relations between people and things (i.e. the means of production) and those between people (and especially those who control the means of production and those who do not). The social relations of production have a twofold impact: they constitute the processes of labour and production and they regulate the social division of the wealth produced (Poulantzas Citation1974).

In his classical book Labour and monopoly capital (first published in 1974), Harry Braverman (Citation1998) discusses how, in most capitalist industries, labour initially put its imprint on the labour process. The craft and skills embedded in labour were essential. The labour process was artisanal and capital could not control it completely. Capital operated mainly through, and by means of, its control over the different exchange relations that existed within, and between, the labour market and the markets for machinery, buildings, raw materials and manufactured products. This control allowed for the creation of surplus value: the value that capital could squeeze out of the production process. Only with the introduction of ‘management’ (a layer between the workers and the owners of the means of production) did capital begin to wrest direct control over the processes of labour and production. This direct control brought restructurations that allowed ever more surplus value to be obtained from the process of production: ‘the processes of production are […] incessantly transformed under the impetus of the principal driving force, the accumulation of capital’ (Braverman Citation1998, 6). Technological change and the associated increases in the productivity of labour became more or less permanent outcomes of such transformations. Braverman views the loss of direct control of labour over the process of production as ‘the degradation of work in the twentieth century’ in which work was reduced to the monotonous repetition of a single task, and the workers lost their overview over the production process as a whole, which became the responsibility of management. At the same time, the dangers related to work (job-related diseases, accidents, exposure to contamination, etc.) increased considerably. Labour suffered a de-skilling, which often went hand-in-hand with further decreases in wage levels.

Labour unions were a response to these decreases. They were often able to raise salaries and wages through collective bargaining and lobby for regulatory changes that improved health and safety in the workplace. The price, though, they had to pay for the improvement of labour conditions (including the remuneration of work) was a further decrease in workers’ control over the process of production (Braverman Citation1998, 8, 9). This decrease, and the dehumanization of work that came with it, spurred new movements (the creation of workers’ councils, the occupation of factories and the redefinition of work and the labour process, the construction of worker-controlled cooperatives, as well as slow-downs and sabotage) through which workers sought to regain control over the labour process. A highly significant episode in these struggles was the wave of occupations of major industries in Northern Italy at the end of the 1920s. In the late 1960s and early 1970s such struggles emerged again. They resulted in a rich set of theoretical elaborations on the relevance of workers’ control over the labour process (see, for example, Trotta and Milana Citation2008). This literature stresses that it is not just capital that shapes the social relations of production but that these can also be (re)shaped by labour. Cleaver (Citation2000) argued that, labour might ‘take the lead’: introducing radical changes in the material organization of production, especially in periods of intense turbulence.

The agricultural sector followed a different trajectory. With the exception of capitalist farm enterprises, the organization and development of the agricultural labour process remained a domain that was fully controlled by the producers themselves. According to their specific circumstances, they applied the locally-prevailing cultural repertoire in ways that aligned the operation of the farm, as much as possible, with their own interests and prospects (Hofstee Citation1985). Organizing and developing the farm was the duty, responsibility, and privilege, of the farmer, to the degree that the external features of the farm were taken as indicators of the capabilities of those who worked it.

It is only since the late 1950s and early 1960s that this pattern started to change, with many of the tasks that make up the agricultural labour process being increasingly prescribed (and eventually sanctioned) by outside agencies, such as banks, the providers of technical inputs, extension services, accountancy bureaus, food industries, traders and government institutes (for water management, the prevention of plant and animal diseases, etc.). The French rural sociologist Rambaud (Citation1983) referred to this newly emerging layer (that operates as a kind of collective manager) as the nomenclatura, whilst Benvenuti (Citation1982), an Italian scholar who worked in the Netherlands, referred to it as TATE, a Technico-Administrative Task Environment: a web of increasingly interconnected institutions that specify how the farm is to be operated. The Dutch language even has a word for such people: erfbetreders (‘those who walk into the farm’). Whatever term we use, this newly emergent layer of ‘external’ management brought ‘the dictation to the worker of the precise manner in which work is to be performed’ (Braverman Citation1998, 62), replicating in agriculture (although perhaps to a less pronounced degree) the same processes that occurred in industry previously (Lacroix Citation1982; McNamara et al. Citation2018; van der Molen et al. Citation2018).

The emergence of ‘external management’ that controls the labour process located within the farms coincided with, and is rooted in, two material changes. One is the externalization of an increased number of tasks of the farm labour process to outside agencies. This implies that the tasks that do remain within the farm need to be aligned with external artefacts and protocols. Take seeds, for instance: a growing number of farms externalize their selection, multiplication and improvement to outside agencies (seed companies) that produce the seeds that are acquired by farms that no longer produce their own seeds (Kloppenburg Citation2014). As a result the seeds are sown and managed according to the manual that comes with them, specifying the land preparation, timing, depth and density of seeding, fertilization, etc. This may seem to be a minor technical point, but it represents a major rupture: before externalization, seeds in the farm were selected (nearly naturally) so as to fit with the conditions and characteristics of the farm and the way it was operated – now it is the other way around: the farm and labour process need to be modified so as to meet the requirements of the acquired seeds (van der Ploeg Citation1993; Scott Citation1998; Wynne Citation1996).

Apart from the reproduction of plant materials, many other tasks have been externalized (the on-farm production of many essential inputs; food-processing; the development of knowledge and skills and the socialization and training of the labour force, to name but a few). Following Braverman, externalization brought (a) ‘the dissociation of the labor process from the skills of the workers’ (Citation1998, 62); (b) ‘a separation of conception from execution’ (Citation1998, 80); and (c) ‘the monopoly over knowledge to control each step of the labor process and its mode of execution’ (Citation1998, 82). In short: ‘the [farm] labour process is rendered independent of craft, tradition and the workers’ knowledge’ (Citation1998, 78).

This process was actively driven forward by state agencies and capital groups under the umbrella of ‘modernization’ and ‘technological progress’ and, after a while, the hegemonic farmers’ organizations also became supportive of this process. And while it did bring a range of advantages – at least in the short and medium run – many farmers became concerned about the distortions that it created: declining soil fertility, reduced longevity of animals, greater susceptibility to diseases, new risks, stagnating incomes and a lack of prospects and autonomy (Eizner Citation1985).

The second major material change (that strongly interacts with the first one) is located in the modified nature of technological designs. Benvenuti refers to this phenomenon when discussing ‘technology as a language’ (Citation1982). Technological artefacts ‘tell’ farmers how to run, adapt and develop their farm. New technologies often operate as change agents in disguise. Take, for example, the refrigerated milk reservoir that allows milk to be stored for 2 to 3 days in the farm before it is collected by the dairy. In the 1970s these milk reservoirs replaced the churns (or milk cans) that were collected twice a day.Footnote3 The milk reservoir, like other technological devices, assumes and imposes a series of connections in order to function properly. There needs to be high voltage current, a milking parlour connected with a tube to the milk reservoir, milking can no longer be done in the meadows (unless extra investment is made in a mobile reservoir), the farm yard needs to be made suitable for the larger trailers that now come to collect the milk and the stable (cow shed) is preferable to a cubicle stall. With the change from milk churns to refrigerated reservoirs ‘the instrument of labour is removed from the workers and placed in the grip of a mechanism [that] acts upon the materials to yield the desired result […]. The change in the mode of production in this case comes from a change in the instruments of labour’ (Braverman Citation1998, 117; emphasis added).

A farm is a complex and finely tuned constellation with many interrelations between its different component parts. When one specific artefact is ‘plugged’ into this constellation, many connections need to be reconsidered and retuned, and many of the composite elements have to be adapted. If not, the system functions badly and the farmer is faced with disappointing levels of production and increased cost levels. Thus, technological developments indirectly impose new constraints and strictures over the labour process.

Labour, in the industrial sector, has become increasingly standardized since the 1920s and ‘scientific management’ played an important role in this. In farming, labour started to become prescribed and standardized in the 1960s with ‘scientification’ again being a key mechanism – through the ‘Green Revolution’ in the Global South and the ‘Modernization of Farming’ in the Global North. Goodman, Sorj, and Wilkinson (Citation1987) discussed this in terms of appropriation and substitution, whilst Guthman (Citation1998) and Morgan and Murdoch (Citation2000) did so for organic agriculture.

As farm labour was gradually forced to submit to the dictates of Rambaud’s nomenclatura, farmers lost control over their labour process and were increasingly obliged to follow externally defined scripts. This was accompanied by a redistribution of the produced wealth (Inosys Citation2017). The new technologies and inputs came at a price: they involved monetary expenditure, which reduced the value-added that remained on the farm.Footnote4 Thus, externalization, the associated increase in dependency on upstream markets (for resources that facilitated or, in some cases, were required for the process of production), technological development and state programmes meant that the ‘modernization’ of farming brought a fundamental and far-reaching reshuffling of the social relations of production. They contributed to and, in the end, resulted in, an expropriation of farm labour. This expropriation was twofold. It occurred at the material level through increased parts of the wealth produced in the agricultural sector being channelled towards external capital groups, but also in terms of autonomy, as control over the labour process, once the bulwark of the peasantry, was lost to the nomenclatura.

3. Agroecology

Agroecology is a powerful and timely response to this double expropriation of farm labour. It seeks to regain control over the labour process and addresses the appropriation of value by external capital groups in novel, and increasingly successful, ways. In this respect, agroecology is transforming agricultural production, making it more sustainable, more productive, more remunerative, more attractive and more variegated (Sevilla Guzman Citation2007; Wezel et al. Citation2009; Gonzalez de Molina and Guzman-Casado Citation2017). This shows that peasant struggles are not just reactive. They are not just following and responding to capital. They are transforming the praxis of farming, moving it beyond the many contradictions that are currently strangling it. In short capital is no longer solely writing the script. Labour (in the form of peasants and farmers) is actively moving farming in new directions, constructing new realities and opening up future developments.

Agroecology is bringing about a socio-material transformation of agriculture (de Schutter Citation2010) that critically affects and remoulds the material, politico-economic and socio-political dimensions of agriculture. It does so, first, because it once again gives a central role to the natural and social resources that are available within (or in close proximity to) the farm. Agroecology focuses on building an autonomous resource-base that is used according to ecological principles and cycles (Altieri Citation1995; Gliessman Citation2007). This is in stark contrast to the double expropriation by capital, which has resulted in the marginalization of internally available resources (which were replaced by external ones). Natural resources (the land, soil biology, animals, plant materials, fields, ecological infrastructure, etc.), the knowledge on how to combine them into a well-balanced productive whole, the possibility of sharing experiences, resources and products with others, and the autonomy needed to control the labour process are strategic in this respect. Together with this, agroecology also changes several relations within, and between, farms. In contrast to the high levels of specialization induced by capital, agroecology stimulates mixed (‘multifunctional’) farms that combine different lines of production (different crops and animals and sometimes ‘non-agricultural’ activities) (Petersen Citation2018). The typical agroecological farm produces many of the inputs that it needs (energy, manure, seeds, feed and fodder, young animals, maintenance facilities, savings for investments, knowledge, etc.) by itself and/or in cooperation with other agroecological farms (Lucas, Gasselin, and Van der Ploeg Citation2019). Secondly, agroecology changes a range of external relations, with the providers of technologies and inputs, banks and processing industries. This change forces the nomenclatura to retreatFootnote5; it is increasingly replaced by direct exchanges of experiences (of the campesino-a-campesino type), mutual help and farmers’ schools (Rosset and Altieri Citation2017). Together the re-organization of the resource-base and the re-patterning of the relations in which the farm is embedded imply a reshuffling of the social distribution of the wealth produced, offering the promise of generating better incomes than can be earned through agriculture structured by the imperatives of capital. Thirdly, agroecology also transforms the identities of its practitioners: it re-introduces the peasant as a decisive, and distinctively different, actor (Rosset and Altieri Citation2017) – one who is central to, and integrally responsible for, the production of food and eco-services (instead of being a ‘puppet’, applying the script of others). This often translates into a call for self-regulation, exemplified by the case study explored in this paper.

4. Agroecology and ‘labour income’

The concept of income can be understood and operationalized in different, sometimes strongly contrasting, ways. In agroecology income is mostly equated to the gross value of marketed production, minus the monetary expenses related with this production (basically, purchased inputs and services, together with the depreciation of medium and long term investments). This is identical to what Chayanov referred to as ‘labour income’ (Chayanov Citation1966; van der Ploeg Citation2013) and what peasants, through the ages, have referred to as ‘the clean part’ (Slicher van Bath Citation1958; Yong and van der Ploeg Citation2009). Practically speaking, the concept of labour income is synonymous with the value added at the level of the farm enterprise (which is the same as VA related to the number of producers who will share it). Peasants seek to optimize their labour income, and balance this against the ‘drudgery’ needed to realize it and the number of people who are to be supported, directly and/or indirectly, completely and/or partially, with it.

The labour income of those working in a farm (the value-added per unit of labour force: VA/LU) can be enlarged in a variety of ways. It can be done by increasing the gross value of production per unit of labour force (GVP/LU), producing more per person (which is identical to enlarging labour productivity). Another possibility is to increase the value-added as part of the total value of production (VA/GVP). Together VA/GVP and GVP/LU determine the labour income or VA/LU since VA/GVP * GVP/LU = VA/LU. An increase in VA/LU can be achieved by increasing GVP/LU, VA/GVP or a combination of the two.

Entrepreneurial agriculture, largely shaped by the logic of modernization, basically aims at increasing GVP/LU. This is generally achieved by enlarging the scale of production, ongoing specialization and technology-driven intensification. Such increases in GVP/LU are in line with capital’s interests since they increase demand for inputs, expensive technologies and ever-larger loans to finance these purchases, while at the same lowering the transaction costs for processing industries and giving more opportunity to impose lower prices on producers (since the supply has been increased).

Agroecology pulls on ‘the other lever’: searching for a higher VA/GVP. By replacing external resources with internal ones and improving their use-efficiency, agroecological practices systematically lower both variable and fixed costs, thus enlarging VA. These costs are further lowered due to the multifunctional nature of agroecological farms: when a particular resource (e.g. a tractor) is used for both arable and dairy production, the costs of this resource are shared by the different activities (Scherer Citation1975; Saccomandi Citation1998). Labour plays a central role in this ongoing search, especially when combined with skill-oriented technologies (Bray Citation1986) which can play a key role in fine-tuning the process of production as a whole and further increase the VA/GVP ratio.Footnote6

Consequently, if the volumes of production and price levels are equal,Footnote7 agroecological production generates better incomes than conventional farming. But there are other additional advantages, both to the individual farmer and society at large: agroecology increases employment, reduces indebtedness and the consumption of fossil fuels, increases the opportunities for farm succession making it easier for the next generation to take over the farm, and it comes with a quality of work that is more varied and attractive (Garambois and Devienne Citation2012). Empirical evidence from different European countries confirms the higher levels of income realised by agroecological farms (this research is summarized in van der Ploeg et al. Citation2019; see also Devienne et al. Citation2016 for dairy farms; Lechenet et al. Citation2017 for arable farms). gives a synthesis of some of the main findings.Footnote8

Table 1. Examples of the economic benefits of agroecology.

In addition to these benefits, agroecological farms are often able to realize prices that are significantly higher than those for conventional products.Footnote9 This is related to the possibility of formally converting to organic production and, more, to the possibility of producing regional specialities with organoleptic characteristics that reflect the specificity of the local (by using internal resources agroecological farming has strong links with the local ecosystem or terroir). Realizing this potential often requires collective effort and Austria has some impressive and well-documented examples of well-designed structures for processing and marketing agroecological produce (Schermer Citation2017).

The comparative data given in might provoke, at first sight, some perplexity. Given such income differentials, how can one explain that the large majority of farmers has, as yet, not converted to agroecological approaches? The answer is in the path-dependency constructed over the last decades. The high levels of indebtedness, contractual agreements with food industries and the farm structures built so far (technologies included) tie large segments of the agricultural sector into high input/high output systems (van der Ploeg Citation2018).

5. Towards self-regulation and new, nested markets

Regaining control over the labour process should not in any way whatsoever be equated with a retreat back to individualism and autarchy. The agricultural labour process requires cooperation at different levels; it needs many exchanges (with other farmers, consumers, processors, etc.) and it needs to articulate and represent itself in a complex and demanding society. All of this implies that agroecology needs representation and collective agency. To meet these requirements, self-organization and self-regulation come to the fore as strategic mechanisms for maintaining and strengthening the regained control over the labour process.

The principles of self-organization and self-regulation have been successfully applied to the distribution of agroecologically produced food, leading to the construction of nested markets, i.e. markets that are embedded (‘nested’) in mutual agreements between producers and consumers (van der Ploeg, Jingzhong, and Schneider Citation2010). In turn, these self-organized and self-regulated markets (that take many different forms) help to redistribute the total value-added along the chain in ways that are more favourable to producers.

During the first two decades of the twenty-first century the literature on self-organization and self-regulation in agriculture has grown rapidly (see van der Ploeg Citation2018, 179–204 for a synthesis). Self-regulation often starts in non-regulated spaces (or ‘institutional voids’ as Hajer Citation2003 puts it), just as self-organization mostly occurs in interstices (Holloway Citation2000, Citation2010). Nested markets particularly thrive where there are ‘structural holes’, i.e. a lack of adequate connections, in the dominant system (Burt Citation1992). This shows that, while self-organization and self-regulation are partly ‘subjective’ features (they strongly depend on the goal-orientation, knowledge and agency of the collective actors involved), they are also driven by ‘objective’ external circumstances. The following section demonstrates the importance and centrality of these two features.

6. Struggling to regain control: empirical evidence from the Northern Frisian Woodlands

The Northern Frisian Woodlands are located on the sandy soils in the east of the Province of Fryslân in the north of the Netherlands, formerly a very poor area, with many small farms and a population that engaged in migrant labour. The area has a strong anarchist tradition that was rooted in the peat industry and headed, amongst others, by a charismatic clergyman (Domela Nieuwenhuis), locally also known as ûs ferlosser (‘our liberator’). The area currently specializes in dairy farming. It has a scenic, man-made, corridor landscape, containing many hedgerows and alder belts and is extremely rich in biodiversity.

In the 1980s the peasant population of this area was confronted with a new regulatory scheme (the ‘Ecological Directive’) that aimed to protect the natural environment from acidification.Footnote10 The newly imposed rules implied a complete standstill for all agricultural activities located within a radius of 500 m of ‘acid-sensitive’ natural elements, such as water courses, hedgerows, bushes, etc. Given the density of the small-scale hedgerow landscape this would have brought a complete halt to farm development in the area. This caused considerable anger among local farmers who contested this proposed legislation and eventually came up with a counter-proposal centred on the notion of an institutional exchange: ‘if government declares the natural values in the area to be non-acid-sensitive (that is: if the area is exempted from the general rule), then we, the farmers in the area, promise on our turn to maintain the landscape and biodiversity and to reduce ammonia-emissions’. The local farmers formed two local peasant associations (VEL and VANLA) that aimed to care for nature and landscape, to actively reduce emissions and to present their case to different state agencies. The provincial government was the first to accept their demands and the national government followed a while later, albeit only after parliamentary pressure.

The development of the first two (quite small) associations into what is now a strong territorial cooperative (also called Northern Frisian Woodlands, or NFW) that currently has some 1000 members and covers around 50,000 ha, is a textbook example of the theoretical notions discussed earlier in this paper. The farmers in the area struggled, first individually, then together, to regain control over their farm labour processes. By doing so they (a) reshaped the socio-material nature of agriculture, (b) enlarged their share of the total wealth produced and (c) developed effective mechanisms for self-regulation.

6.1. Hoeksma: reducing dependency on external inputs

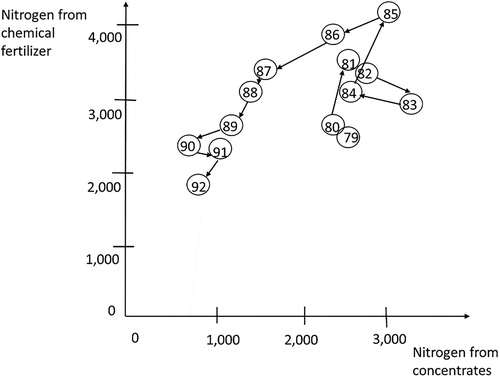

refers to the farm of Taeke Hoeksma, a prominent peasant farmer from the area who was involved in the creation of one of the first associations. The figure reflects the amount of nitrogen, embodied in concentrates and chemical fertilizer, that he ‘imports’ into his farm in order to produce (a standardized production of) 100,000 kg. of milk. In 1979 (the first year in the graph) in order to produce 100,000 kg. of milk,Footnote11 Hoeksma needed 2800 kg. of pure Nitrogen contained in bought feed and fodder (mainly concentrates) and 2400 kg. of pure Nitrogen contained in fertilizer. Hoeksma started to document his use of these external inputs because he had become very worried about the degradation of the quality of his soils. The years that followed show a pattern that is characteristic for peasant agriculture. Every year Hoeksma altered the amounts of nitrogen applied through the combination of chemical fertilizer (for the meadows) and concentrates. The changing combinations and changing amounts were in effect a series of small experiments, which were carefully observed, compared, analyzed and then translated into new trials. Such cycles of observation, comparison, interpretation and, in the end, reorganization of farming are, in a sense, the nervous system of the farm: guiding and tuning the different activities, allowing for continual learning and for the farmer wresting back control over his production.

The early 1980s were a difficult period on the farm (partly because maize was introduced although it was eliminated again a few years later) but from 1985 onwards there were continuous decreases in the total amount of Nitrogen used in the farm (from 6800 kg in 1985 to just 2300 in 1992). However, this huge reduction did not translate into lower grass yields and/or lower milk yields. On the contrary, Hoeksma is known in the area as a very good ‘grassland farmer’. The explanation of the productivity of Hoeksma’s farm lies in the very good (and continuously improved) quality of the manure produced on the farm, the sturdy cows and the rich soils. Thus, by steadily building up the quality of the internal resource base, Hoeksma was able to reduce his use of external inputs in a step-by-step way.

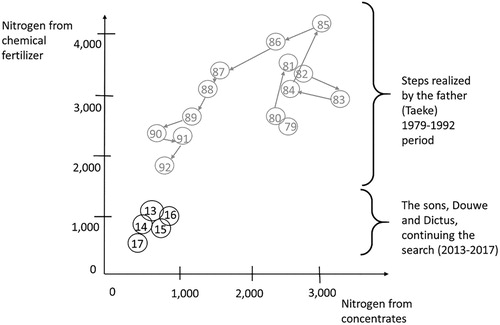

Some 25 years later Douwe and Dictus, the sons of Taeke Hoeksma, now work together on the farm and have been doing so for quite some time. (constructed in the same way as the ) summarizes the changes that occurred in the 2013–2017 period. Again there have been ongoing alterations, that have resulted in further increases in sustainability and resource-use efficiency. Between 1992, the last year of the first Figure, and 2017, the last year represented in , the use of externally supplied Nitrogen (needed for the production of 100,000 kg. of milk) decreased by a further 1600 kg, (that is, 61%). This brought the N surplus/ha well below 50 kg. N/ha.

6.2. Farmer-led research

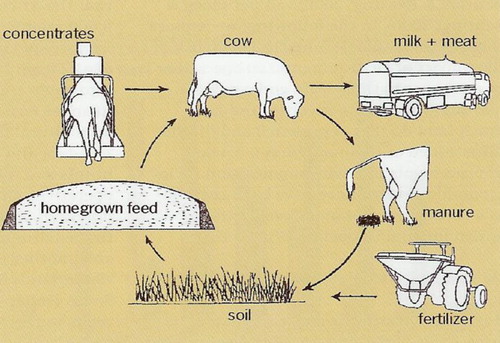

In the early 1990s the search of the Hoeksmas and others was combined in an important farmer-led research programme run by the first two associations. Through this farmer-led research the experiences of the Hoeksmas ‘travelled’ to neighbouring farmers and, in the end, to many other farmers throughout the Netherlands. The programme addressed the most important agronomic cycle entailed in dairy farming – the one that links cows, manure, grassland production and cattle-feeding (see also ) – and aimed to re-balance it in order to get a better whole farm equilibrium.Footnote12 The programme was designed by local farmers who chose to focus on the interfaces between the different elements of this cycle. They recognized, for example, that manure should not be considered as a separate element or be explored, understood and improved in isolation. ‘Good manure’ is only ‘good’ in as far as it positively affects soil biology and grassland growth. And the farmers recognized that the key to obtaining ‘good manure’ lay in making strategic changes to cattle feeding. This approach is typical of farmers’ knowledge: it focuses on the single elements through the interrelations in which they are embedded. This represents a basic difference with formal scientific knowledge, that tends to study single elements in isolation, i.e. in standing on their own and being determined by their internal composition.Footnote13

The farmer-led research resulted in new knowledge on improved manure, soils, fodder and cows and resulted in a re-setting of the cycle as a whole, that brought the overall use-efficiency of nitrogen from some 16% up to more than 50%, which in turn changed the socio-material reality of agriculture in the area. Manure was literally re-built to have a higher C/N ratio and lower levels of ammonia (Reijs Citation2007). The interface between manure and soil was improved through the design and construction of new machinery for spreading manure. Soil biology was enriched through the improved application of the improved manure (Sonneveld Citation2004), which in turn resulted in improved grassland production (partly because improved soil biology increases the soil’s capacity to autonomously deliver nitrogen). Finally, feeding the cattle with improved feed and fodder extended the animals’ longevity and gave milk that was richer in protein and fat contents and, indeed, improved manure. Thus the cycle was closed again but now at a much higher level of efficiency (and fewer costs).

In a way, improved manure was key to the whole process. This reflected, and confirmed, the initial impressions of farmers such as Taeke Hoeksma (and others). This central notion was tested in a patient, multi-year, farmer-led, field experiment in which different types of manure were applied, in different quantities, on different soil types. It is telling that applying standard scientific methodologies for experimental trials rendered no significant conclusions whatsoever, whilst other approaches (centring on the interactive effects) showed distinctive and statistically significant results. Thus, the experimental plots of VEL and VANLA became yet another ‘battlefield of knowledge’ (Long and Long Citation1992; van der Ploeg et al. Citation2006; Groot et al. Citation2007).

6.3. Towards self-regulation

Cooperation was crucial in this common research programme, which started with 60 farmers and grew to include many more. Cooperation was needed for the research itself – but equally to create sufficient agency to be able to deal with the participating scientists and, especially, to negotiate with state agencies over the conditions necessary to further unfold this field research and bring about socio-material changes to local farming.

When the first two associations merged into the present-day territorial cooperative (NFW), this created the basis for the required cooperation and the much-needed agency (or counter-power). The NFW is now able to negotiate new forms of local self-organization and self-regulation. Telling examples include training rural women in order to involve them in the staff of the cooperative, forms of self-control and the development of manuals and guidelines for improving the management of nature, the landscape and biodiversity. With these, and many other, mechanisms the NFW is slowly, but persistently, moving towards a ‘self-organizing space’ (Friedmann Citation2006)

6.4. Redistributing the wealth produced

How has all this translated in terms of income effects? ‘Wat smyt it op?’ [What does it bring us?] as the Frisians would say. It had been known for a while that farming ‘in an economical way’ (that is, with low external input use) provides incomes that are, at least, comparable to those of the average farm (van der Ploeg et al. Citation1992; Antuma, Berentsen, and Giessen Citation1993). The first empirical studies that compared the economic effects of the new approach (van der Ploeg et al. Citation2003; Groot, Rossing, and Lantinga Citation2006 and Reijs Citation2007) showed that those engaged in it, improved their labour income per 100 kg. milk by 1–2 Euros, while ‘conventional’ farmers in the area and Fryslân as a whole were seeing their returns decline (minus 1 Euro over the 1997/98–2000/2001 period). For the average farm this amounts to some 10,000 Euros extra labour income per year. In addition to that there are the payments for the maintenance of nature and the landscape. According to a study by Heijman (Citation2005), these bring an average additional 5000 Euros per farm.

7. The translation towards higher scale levels

In early 2015 Teunis Jacob Slob, a dairy farmer from the west of the Netherlands retired as president of Veelzijdig Boerenland [‘Colourful Peasant Land’], a second-tier cooperative that unites and supports a number of peasant associations engaged in the maintenance of nature and the landscape. Hundreds of people attended the meeting; all of them actively involved in the struggles that are currently changing Dutch farming and the Dutch countryside. Naturally, a delegation from NFW also attended. The gathering of all these people, from all over the country, underlined that NFW is not operating alone or by itself. It is, instead, part of (and, in large part, an inspiration for) a far wider process of change.

When the first associations (VEL and VANLA) that later became the building blocks of NFW started their activities, their practices and proposals were considered as a rebellion. Caring for nature and landscape was not farmers’ business but the task of professional organizations such as Natuurmonumenten, Staatsbosbeheer and Fryske Gea. The proposal that such maintenance could be equally well (or perhaps better) done by farmers represented a rupture in the established division of labour. Farming and maintaining nature were understood, and represented, as separate domains. In this respect combining agriculture with nature and landscape management filled an ‘institutional void’. The large dairy cooperative, for instance (Friesland Campina to which most farmers in the region sell their milk), was sceptical of proposals for the agrarian maintenance of nature and landscape saying that: ‘we are not interested in lumberjack milk’. It was even more an act of rebelliousness given that the proposal to take on board responsibilities for nature and landscape management was meant to counteract the state policy of the time that aimed at curtailing local agriculture in the name of ‘nature protection’.

Now, more than 25 years later, the NFW is a well-organized and well-functioning territorial cooperative, and farmers’ management of nature and landscape is now a widely accepted and well-institutionalized practice that is supported and funded by the EU, the Dutch State, the Province and a range of ‘neighbouring’ organizations and movements (including the environmental movement, the nature organizations and the Water Board). Today, an outsider would hardly see this change as being rebellious; the initial rebellion was seemingly short lived (as appears to be the case with many, if not most, peasant uprisings [Paige Citation1975]). It was only a ‘rebellion’ until the point when the peasants’ proposals were taken over (i.e. ‘accepted’) by state agencies at different levels and thus became ‘conventionalized’ (as this process is referred to nowadays [see e.g. Guthman Citation2014 and especially Bonanno and Wolf Citation2018]).

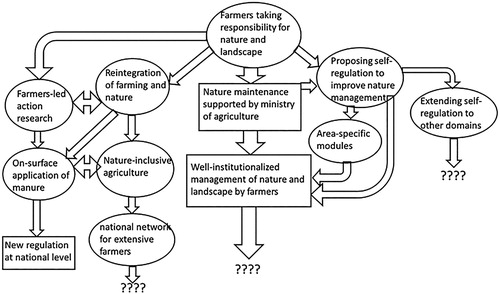

Careful observation, however, shows that things are very different. It is true that the farmers’ collective proposal to maintain nature and the landscape was (after a long struggle) accepted by the state and has evolved into an institutionalized practice that has subsequently been applied across the country as a whole and in increasing parts of the EU as well. And, while there still are frictions, this model has now, on the whole, evolved into a smoothly functioning constellation of interconnected practices and has more or less become routine. But the same institutionalization has triggered (and keeps triggering) a range of new rebellions that have led to the NFW emerging as a strong democratic entity that unites nearly all the farmers in the area and which is increasingly capable of putting its imprint on evolving agricultural realities within, and even beyond, the area. These new rebellions and their connections to more conventional practices are summarized in .

There are, of course, no clear cut delineations, nor black and white contrasts, between those practices that are prescribed and financed by the state (the conventionalized practices – indicated by rectangles in ) and the novel, rebellious practices (indicated by ovals) that move beyond external prescription and question the routines imposed by the state, agro-industries and/or the dead hand of history. Even the practices that are routinized and embedded in strict regulatory schemes can sometimes generate frictions that require subsequent negotiations or even lead to law-suits challenging the government’s interpretation of its own rules, regulations and underlying principles (thus generating what Kerkvliet [Citation2009] termed a kind of ‘rightful resistance’). On the other hand, the novel practices relate to current routines and regulatory schemes, but they simultaneously try to go beyond these by designing, and experimenting with, new solutions that are at odds with the existing ones. By and large, some practices get conventionalized (they become established within existing regulatory schemes), although some of them and other (novel) practices continue to alter the regulations.

Thus, the differences between the two are gradual. Nonetheless, it is a useful distinction to make as it allows for the elaboration of some strategic points. First there is an organic unity between conventionalized and novel practices, as is evident with the NFW (and I think this applies more generally for agroecology). Initial rebellions flow into practices that become conventionalized, generating, in turn, new activities that strive for additional breakthroughs. Take for example the left-hand side of the scheme presented in . Once the notion of caring for hedgerows, alder belts and ponds was activated, farmers started to reflect on how to better use nature as a useful resource (Swagemakers Citation2008). They were initially interested in exploring issues around soil biology and how it is affected by using different types of manure and slurry, but they also became interested in the phenomenon of cows curing themselves (for example of internal parasites) by means of selective browsing from the hedgerows. This inspired the farmer-led research programme (a novelty in itself) focussing on the interactions between cattle-feeding, manure quality, soil biology and dry matter production per hectare which highlighted the importance of ecological principles and well cared-for agronomic cycles within dairy farming. This was not a result of consulting textbooks, but through making cross-farm comparisons and the visible outcomes of experimental plots – which is what convinces farmers more than anything else (Stuiver, Leeuwis, and van der Ploeg Citation2004). Through all this (including the experiences of the many farmers who slowly shifted towards a more economical way of farming, spending less on chemical fertilizers and concentrates), the notion of ‘nature-inclusive agriculture’ was born: a local version of agroecology (though no-one referred to it as such at the time) . One telling detail is that even, in its early versions, this vision stressed the need for radical changes at the level of the nomenclatura (the technological-administrative support structure).

When the regulation on manure was tightened (following the increase in phosphate surpluses that resulted from overproduction after the quota system was abolished) the notion of nature-inclusive farming (by now also referred to as closed cycle farming) had travelled to the national level. The new regulation favoured farms that were rapidly expanding their production (mostly large-scale, intensive and specialized farms), whilst those who did not expand (including most organic farmers and extensive farmers who maintained appropriate balances between land and cattle) were left to pay the biggest part of the bill. This caused considerable anger and the NFW launched a nation-wide network (Netwerk Grondig)Footnote14 to fight this regulation. It is a struggle that, at the time of writing, is ongoing and it is not possible to predict how it will be resolved (hence the question marks in ).

Similar stories can be told about the other lines of action shown in . What is important is that they repeatedly show that the dialectical relation between conventionalized practices and the novel, disruptive, ones cannot be understood as oppositional or mutually exclusive. Precisely the opposite applies (and this becomes clear when we take time and space into account). Rebellions result in practices that become institutionalized and, ultimately, conventional.Footnote15 But then these conventionalized practices generate new insights, practices and proposals (for instance an extension of self-regulation in order to make agrarian maintenance of nature and landscape more effective; or new forms of self-control that can greatly reduce administrative costs). The development of such proposals might be (and mostly is) supported by the organization that has been established and built to carry these conventionalized practices forward.Footnote16

Today there are some activities that are conventional: which have been stripped of any last vestige of disruptiveness. They have been deactivated into ever-so-many innocuous parts of hegemonic logic and discourse. But this should not lead us to diagnose a general or inevitable trend towards conventionalization. Today’s conventional practices are part of a wider movement through time that is continuously generating new, rebellious, activities that question reigning logics and create new, novel practices. If we take a longer-term perspective (NFW has now been in existence for 30 years), it is evident that the movement as a whole is now far stronger; has a wider and better developed programme; is more able to sustain its own activities, and has more credibility in the eyes of those with whom it ‘does business’. The fact that some activities have become conventional has not neutralized the movement but has actually strengthened it.

This conclusion applies even more when the spatial dimension is taken into account. Within the area itself farmers’ management of nature and landscape is a widely accepted and applauded practice. Yet, this same conventionalized practice, however, might pop up, within the Hague (the location of the Ministry of Agriculture), Amersfoort (headquarters of the large dairy industry) or Utrecht (where the main offices of the RABO bank are located) as being disruptive – as a practice that is at odds with the dominant logic and capable of slowing down processes of accumulation.Footnote17

7.1. Upscaling

These, once rebellious, now conventionalized, practices have not stood still but have gone through different stages of up-scaling. Groups of farmers from all over the Netherlands followed NFW’s example: moving from individual maintenance activities towards the joint management of nature and the landscape. At one point the Netherlands had nearly 400 farmers’ associations for nature and landscape management. Many of them were directly inspired by the NFW; in many cases a visit to the NFW was the trigger that set these new associations in motion. A second stage in the process of upscaling was induced by the new (2013–2020) European Regulation for Rural Development.Footnote18 This Regulation (no. 1305/2013) explicitly allows agro-environmental measures (the maintenance of nature and landscape included) to be organized collectively and offers higher payments to such self-governing groups (+30%)Footnote19 to cover the costs of governance and management. This brought about a far-reaching reshuffling. In order to avoid high transaction costs, the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture required the many associations to merge into a smaller number of collectives (currently 44, the NFW being one of them). It also led to a standardization of the many localized and diverse initiatives, in order to bring them in line with the funding and control mechanisms for this regulation.Footnote20 This induced considerable bureaucratization, leaving many of the newly merged collectives with hardly any time to engage in new, creative, initiatives.Footnote21

Ironically, the same conventionalization brought about some ‘rebellions’ in other places, some faraway. In Italy, for instance, the care for nature, landscape and biodiversity was not included in the national implementation of agri-environmental service provision. When a group of Italian farmers visited the NFW and were informed about the possibilities offered by the new Rural Development Regulation (or Pillar 2), they came together and claimed similar rights from their government. The NFW’s influence is also ‘travelling’ to other levels: as exemplified by the recent proclamation from Provincial Minister for Agriculture Johannes Kramer that all agriculture in Fryslân should become organic as soon as possible (Kramer Citation2019; LC Citation2019).

8. On political struggle in the European countryside: some conclusions

If one compares the current situation of the NFW to that of 30 years ago, one cannot but conclude that it has made important gains and is now firmly consolidated. It is widely recognized that farmers’ management of nature and landscape can be highly effective and is able to produce results comparable to, if not considerably higher than, those of the professional nature conservation organizations. At the same time the ‘market’ for green services (including the maintenance of nature and the landscape) has been de-monopolized and farmers have found new opportunities to sustain and improve their incomes. These flows of additional income (on average some 5000 Euros/farm/year) have allowed many farmers to continue farming. Equally, there is a growing political recognition of the enormity of environmental pressures and that farmers might play an important role in mitigating climate change. Finally, the monopoly of the once nearly dictatorial National Farmers’ Union (LTO) has been broken: more voices are being heard, several of them stemming from the NFW. Alongside this, the principle of self-organization and self-regulation is now widely accepted and acts as an important and motivating rallying cry. In short: the correlation of socio-political forces has been changed and new spaces for contestation, negotiation and creating alternatives have been opened – inside, around and/or as a result of NFW as these socio-political struggles have moved on into new arenas (some of which are indicated in ). Thus the cycle that goes from developing agroecological practices, increasing labour income, casting of the nomenclatura, and arranging new forms of self-organization to fighting for self-regulation, is repeated in a myriad of different ways.

NFW is clearly an exceptional case. It is a field laboratory (Stuiver, van der Ploeg, and Leeuwis Citation2003) where new, disruptive, practices were proposed, tested, adapted, implemented, further elaborated and, finally, passed into the institutional circuits that govern agricultural and rural development in Europe. In retrospect, NFW was able to operate in this way due to a range of interacting factors. These include the somewhat peripheral position of peasants from the Friesian Woodlands within the official farmers’ union, LTO, the local cultural repertoire and a history and tradition of peasants from this area being ‘headstrong’ people.

Can this experience be replicated in other areas? Of course not. But there is no need to repeat this experience. NFW has opened ‘windows of opportunities’ that many other areas have used – in many different ways. Some of these areas have discovered institutional voids that were not accessible to the NFW (such as processing local products through new cooperative arrangements) and have constructed novel solutions. Thus, each step is followed by a next one. Sometimes later, sometimes immediately, just as the next step might be realized nearby or faraway. Together, these many steps flow into one, strong movement.

Apart from the immediate gains summarized in this article, there some other, politically highly relevant messages contained in, and articulated by, these gains. The first of these is that it is clearly shown that the organization of farming does not need to be scripted by the requirements of capital. Indeed it can be organized in a way that it is antithetical to those interests. The organization and development of farms and farming does not need to follow the trajectory of scale-enlargement, technology-driven intensification and specialization. The negative externalities that accompany this trajectory – such as the degradation of landscapes, the destruction of biodiversity, increased CO2 emissions, the weakening of regional rural economies and many more, are not inevitable. On the contrary: the oppositional trajectory based upon agroecology (or farming economically and/or closed-cycle agriculture, as it is known in the NFW) can deliver a range of positive externalities and simultaneously generate incomes that are significantly better than those that result from the application of capital’s script. At this stage, this possibly is the most important contribution of agroecology: It is a permanent, material and highly visible critique of the logic of capital and it shows that the world is definitely better off when capital’s control over the production, processing, distribution and consumption of food is reduced. This applies especially since agroecology is a return to the local and to heterogeneity. Both are at odds with standardized, generic regulation and centralized control. Agroecology is, in this respect, a comprehensive and convincing critique that speaks through successfully applying alternative practices and obtaining results that show that agroecology performs better. When this critique materializes, and is articulated, at the territorial level (as in the case of the NFW) it constitutes a ‘space of opposition’ (Pahnke Citation2015) – a bulwark that is simultaneously defensive and offensive: defensive in that it is able to keep rigid regulation and extreme draining at arms’ length and offensive in that it offers the protection that new progressive movements need to develop. Thus, the bulwark becomes a space of, and for, permanent socio-political struggle, whilst showing to the outside world that such struggles are not in vain.

A second observation regards the political relations between the peasantry and capital.Footnote22 As shown in this article, it is not necessarily capital that takes the lead, with labour (I assume the peasantry here to be a specific part of labour) merely being reactive. It is (at least in this case) the other way around: it is the peasants who are taking the initiative and shaping new, promising practices that are subsequently conventionalized by capital and/or the state (at least partly) – after which other, new and rebellious, practices are forged. I do not argue that this will be the case everywhere and always. On the contrary. The point, though, is that the experience of the NFW (and similar cases elsewhere) clearly shows that labour can potentially take the lead and thus generate an intriguing and self-strengthening dynamics. It is precisely this type of dynamics that underlies the dialectics of conventionalization and novel practices that produce ruptures. Through novel practices, the peasantry tries to move the production, processing, distribution and consumption of food (plus the preservation of biodiversity, the maintenance of scenic landscapes, the accessibility of the countryside, etc.) beyond the limits imposed by capital and, by doing so, to relocate farming (further) outside domains that are directly controlled by capital.

The third observation that I want to propose here is that agroecology is, in this respect, an important movement that is helping peasants to move beyond the limits imposed by capital. It does so by moving farming beyond the scripts imposed by capital and the state (ongoing scale-enlargement, technology-driven intensification and specialization as the inevitable path to progress), whilst simultaneously offering an alternative that is increasingly convincing – even in economic terms. It does so too by progressively reducing material dependency on capital (as embodied, for example, in reductions in the use of chemical inputs, concentrates and fossil fuels).

Expressed in more theoretical terms I would argue that agroecology (as theory, practice and movement) is helping to remould the social relations of production in agriculture. Agroecology is moving them from being a set of relations dominated by capital (through a range of material dependencies, a nomenclatura that exerts control and an intensified appropriation of the wealth produced) towards a set of relations that (again) allow for a relatively autonomous peasantry. The key elements of this latter scenario are (1) an autonomous and self-controlled resource base; (2) multiple distantiation from markets controlled by capital and the construction of new, nested, markets; (3) a high quality of labour, exchange of experiences and the availability of skill-oriented technologies, and; (4) self-regulation at the territorial level.

Through the patient construction of these new social relations of production, agroecology is involved in and progressing a massive and promising transformative process that promises to deeply affect and substantially improve the qualities of peasant life, landscapes, nature and food. It is a transformation in which considerable parts of mankind should get involved.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the anonymous reviewers who helped me to improve this paper. I thank Annie Shattuck for inviting me to write this contribution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jan Douwe van der Ploeg

Jan Douwe van der Ploeg is Adjunct Professor in the Sociology of Agriculture at the College of Humanities and Development Studies (COHD) of China Agricultural University (CAU). He is Member of the Board of Agroecology Europe (AEEU) and also Member of the Advisory Board of the Noardlike Fryske Wâlden (NFW), a territorial cooperative in the North of the Netherlands. In the past, he was Professor and Chair of Rural Sociology at Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

Notes

1 In this text I use the term ‘farmer’ in a generic sense. The term refers to men and women and embraces both peasants and agricultural entrepreneurs, two very different modes of farming (van der Ploeg Citation2018). Although the term ‘farmer’ is mostly used in the singular, it can also refer to social groupings (family, kin groups, rural communities, and so forth).

2 Here I take ‘the labour process’ to be the process of production as perceived, and experienced, by those who do the actual work. It normally entails a wide range of tasks and sub-tasks which might be carried out by the same person or several people, whether family members or hired labour.

3 The introduction of milk reservoirs was firstly encouraged, and then enforced, by the dairy industry.

4 The resources previously produced in the farm (e.g. manure which was displaced by chemical fertilizers; self-selected seeds by bought seeds; hay and silage produced on the farm instead of bought-in feed and fodder, etc.) also came with a ‘cost’: it took labour to produce them. However, this cost was non-monetary – producing these resources within the farm avoided monetary costs (and the associated transaction costs) and thus contributed to enlarging the labour income of the farm.

5 Tellingly, a French farmer member of the Confederation Paysanne in France (an organization that has generated many agroecological practices (see e.g. RAD Citation2015)) told me that ‘we had to learn again to say no’.

6 By contrast the search to increase GVP/LU tends to reduce the centrality of labour through making the workload more repetitive and less varied and ultimately ‘deskilling’ the farmer.

7 This has been demonstrated in Dutch experimental research which showed that an agroecological approach can secure an income comparable to the conventional farm, even when the volume of production in the former is half of that in the later (Evers et al. Citation2007; van der Kamp and De Haan Citation2004).

8 All cases included in contain paired comparisons of farms operating under more or less the same conditions and within the same markets. A detailed discussion of the methods used and results obtained is given in van der Ploeg et al. (Citation2019).

9 Apart from the Swiss case, the data in refer to farms operating in the same markets and therefore receiving equal prices per unit of end product.

10 Caused by a combination of excess ammonia from fertiliser applications and manure. The ‘Ecological Directive’ was generic: it applied to the country as a whole, including low emission areas, such as the Northern Frisian Woodlands.

11 For the farm as a whole this came down to an Nitrogen surplus of some 250 kg/ha. Hoeksma applied, on average, 140 kg. of pure Nitrogen in fertilizer per hectare. This is to be compared with the scientific advice of that time: 400 kg. of pure Nitrogen per hectare.

12 It was widely recognized by farmers that modernization had thrown this balance into disarray. The indications were visible everywhere and known to most farmers: more and more fertilizer was needed to maintain grassland productivity and the longevity of cattle was declining sharply.

13 The relational approach of farmers knowledge is a reflection of the reality that a farmer has to deal with the farm as a whole. The ‘essentialist’ approach of science is, in its turn, reflected in, and reproduced by, disciplinary divisions: animal science studies cows, soil science the soils, agronomy studies grassland production, etc., all generally in isolation.

14 In Dutch this name has a double meaning. ‘Grondig’ means ‘earth’ and ‘earthy’, but also ‘thorough’, ‘radical’ and ‘valid’.

15 The application of manure and slurry to the land is another example. Legally, injection is required. NFW, though, negotiated an exception as the injection equipment was too large and too heavy to be satisfactorily used on the small, wet, fields that characterise this area. So NFW developed a technology for on-surface application that fits in the small-scale landscape and allows for the spreading of small quantities. This exception was finally turned into new regulation that allows all extensive dairy farmers in the country to use this approach.

16 This reflects a similar ‘choreography’ to that developed by the Brazilian MST (Movimento dos Sem Terra). After the initial asentamento was created (after long, arduous and painful struggles) it helped other groups involved in land invasions offering them food, seeds, advice, etc., to help them construct their own settlements. Once settled, they in turn assisted the next wave of invasions.

17 For various reasons, the systematic inclusion, within the farm, of nature and landscape maintenance slows down scale-enlargement and technology-driven intensification. It also reduces the need for additional credit (simply because there is less need to further expand the farm size).

18 This new Regulation was partly inspired by the NFW. Delegations of the NFW visited the European Commission and European Parliament, whilst high officials of the EC (DG VI) visited the NFW.

19 This extra remuneration was made more or less irrelevant by the official European Farmers’ Unions (grouped together in COCEGA) and especially the Dutch LTO, who successfully lobbied the Commission to allow individual farmers to receive +20% for administrative costs.

20 The acceptance of collective farmers’ management of landscape and nature by European, national and provincial state agencies and, especially, their incorporation in funding schemes that come with this complex and far-reaching regulation, undoubtedly imply a ‘regimentation’ of the peasantry who are obliged to accept the discipline imposed by the new regulatory schemes.

21 The associated tension is illustrated by the threat of VEL and VANLA, the first founding associations, to withdraw from the larger NFW, although thus far this schism has been avoided.

22 Capital is used here as general category. It shows up, in practice, as agro-industries, state policies, knowledge and regulatory schemes that are disconnected from the local, and the many interrelations between them. Farmers in the area are actively resisting and contesting this hegemonic bloc.

References

- Altieri, M. A. 1995. Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture. Boulder, USA: Westview Press.

- Antuma, S. J., P. Berentsen, and G. Giessen. 1993. Friese melkveehouderij, waarheen? Een verkenning van de Friese melkveehouderij in 2005; modelberekeningen voor diverse bedrijfsstijlen onder uiteenlopende scenario’s. Wageningen: Vakgroep Agrarische Bedrijfseconomie, LUW.

- Benvenuti, B. 1982. “De technologisch-administratieve taakomgeving (TATE) van landbouwbedrijven.” Marquetalia 5: 111–136.

- Bonanno, A., and S. A. Wolf. 2018. Resistance to the Neoliberal Agri-Food Regime, A Critical Analysis. London and New York: Routledge.

- Braverman, H. 1998. Labor and Monopoly Capital. The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. 25th Anniversary Edition. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Bray, F. 1986. The Rice Economies: Technology and Development in Asian Societies. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Burt, R. S. 1992. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Chayanov, A. V. 1966. The Theory of Peasant Economy. Edited by D. Thorner et al. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Cleaver, H. 2000. Reading Capital Politically. Leeds: Anti/Theses, Cardigan Centre.

- de Schutter, O. 2010. “Report Submitted by the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food to the UN General Assembly.” December 20. https://repository.un.org/handle/11176/288653

- Devienne, S., N. Garambois, P. Mischler, C. Perrot, R. Dieulot, and D. Falaise. 2016. Les exploitations d’élevage herbivore économes en intrants (ou autonomes): Quelles sont leurs caractéristiques? Comment accompagner leur développement? Rapport d’étude pour le Centre d’Études et de Prospective du Ministère de l’Agriculture, de l’Agroalimentaire et de la Forêt (MAAF), AgroParisTech-IDELE -RAD, 126 p.

- Edelman, M., and W. Wolford. 2017. “Introduction: Critical Agrarian Studies in Theory and Practice.” Antipode 49 (4). doi: 10.1111/anti.12326

- Eizner, N. 1985. Les paradoxes de l’agriculkture française: essai d’analyse a partir des Etats Généraux de Développement Agricole, avril 1982-fevrier 1983. Paris: Harmattan.

- Evers, A. G., M. de Haan, K. Blanken, J. G. A. Hemmer, C. Hollander, G. Holshof, and W. Ouweltjes. 2007. “Results Low-cost Farm 2006.” Report no. 53, ASG/WUR, Lelystad.

- Friedmann, H. 2006. “Focusing on Agriculture: A Comment on Henry Bernstein’s ‘Is There an Agrarian Question in the 21st Century?’” Canadian Journal of Development Studies XXVII (4): 461–465. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2006.9669167

- Garambois, N., and S. Devienne. 2012. “Les sytemes herbagers économes. Une alternative de développement agricole pour l élevage bovin laitier dans le bocage vendéen?” Economie Rurale 330–331: 56–72. doi: 10.4000/economierurale.3496

- Gliessman, S. R. 2007. Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems. New York, USA: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis. 384 p. (3rd edition 2015).

- Gonzalez de Molina, M., and G. Guzman-Casado. 2017. “Agroecology and Ecological Intensification: A Discussion from a Metabolic Point of View.” Sustainability 9 (1): 86. doi:103390/su9010086 doi: 10.3390/su9010086

- Goodman, D., B. Sorj, and J. Wilkinson. 1987. From Farming to Biotechnology: A Theory of Agro-Industrial Development. London: Basil Blackwell.

- Groot, J. C. J., W. Rossing, and E. A. Lantinga. 2006. “Evolution of Farm Management, Nitrogen Efficiency and Economic Performance of Dairy Farms Reducing External Inputs.” Livestock Production Science 100: 99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.livprodsci.2005.08.008

- Groot, J. C. J., van der Ploeg, J. D., Verhoeven, F. P. M. and Lantinga, E. A. (2007). “Interpretation of Results from on-Farm Experiments: Manure–Nitrogen Recovery on Grassland as Affected by Manure Quality and Application Technique, 1, an Agronomic Analysis.” NJAS 54 (3): 235–254.

- Guthman, J. 1998. “Regulating Meaning, Appropriating Nature: The Codification of California Organic Agriculture.” Antipode 30 (2). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1467-8330.00071,tipode. doi: 10.1111/1467-8330.00071

- Guthman, J. 2014. Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Hajer, M. 2003. “Policy Without Polity Policy Analysis and the Institutional Void.” Policy Sciences 36: 175–195. doi: 10.1023/A:1024834510939

- Heijman, W. 2005. Boeren in het landschap, een studie naar de kosten van agrarisch natuurbeheer in de noordelijke Friese Wouden. Wageningen: WUR.

- Hofstee, E. W. 1985. Groningen van Grasland naar Bouwland, 1750-1830. Wageningen: Pudoc.

- Holloway, J. 2000. Cambiar el mundo sin tomar el poder: el significado de la revolución hoy. Madrid: El Viejo Too.

- Holloway, J. 2010. Crack Capitalism. London/New York: Pluto Press.

- Inosys. 2017. Vaches, Surfaces, Charges … Tout Augmente sauf le revenu. Quinze ans de suivi en Bretagne, Pays de la Loire et Deux-Sèvres. Réseaux d’élevage pour le conseil et la prospective. Collection Théma. 24 p. https://idele.fr/presse/publication/idelesolr/recommends/vaches-surfaces-charges-tout-augmente-sauf-le-revenu.html.

- Kerkvliet, B. 2009. “Everyday Politics in Peasant Societies (and Ours).” Journal of Peasant Studies 36 (1): 227–243. doi: 10.1080/03066150902820487

- Kloppenburg, J. 2014. “Re-purposing the Master's Tools: The Open Source Seed Initiative and the Struggle for Seed Sovereignty.” Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6): 1225–1246. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.875897

- Kramer, J. 2019. Openbare toespraak bij de opening van de FNP campagne (Friese taal), Leeuwarden, Dairy Campus, 25 January 2019.

- Lacroix, A. 1982. Transformations du process de travail Agricole: incidences de l‘industrialisation sur les conditions de travail paysanne. Grenoble: INRA/IREP.

- LC (Leeuwarder Courant). 2019. “Wy sille mear foar ús iten betelje moatte.” Leeuwarder Courant, Leeuwarden, January 26, p. 1 and 33.

- Lechenet, M., F. Dessaint, G. Py, D. Makowski, and N. Munier-Jolain. 2017. “Reducing Pesticide Use While Preserving Crop Productivity and Profitability on Arable Farms.” Nature Plants 3: 17008. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.8

- Long, N., and A. Long. 1992. Battlefields of Knowledge: The Interlocking of Theory and Practice in Social Research and Development. London: Routledge.

- Lucas, V., P. Gasselin, and J. D. Van der Ploeg. 2019. “Local Inter-Farm Cooperation: A Hidden Potential for the Agroecological Transition in Northern Agricultures.” Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 42 (2): 145–179. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2018.1509168

- McNamara, J., J. Leppälä, G. van der Laan, C. Colosio, M. Jakob, S. Vander Broucke, L. Girdziute, E. Merisalu, A. M. Heiberg, and R. Rautiainen. 2018. “Rural Health: Agriculture, Pesticides and Organic Dusts, 1768Safety Culture and Risk Management in Agriculture (Sacurima).” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 75 (Suppl 2), doi:10.1136/oemed-2018-ICOHabstracts.1314.

- Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho, M., O. Felipe Giraldo, M. Aldasoro, H. Morales, B. G. Ferguson, P. Rosset, A. Khadse, and C. Campos. 2018. “Bringing Agroecology to Scale: Key Drivers and Emblematic Cases.” Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 42 (6): 637–665. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1443313.

- Morgan, K., and J. Murdoch. 2000. “Organic vs Conventional Agriculture Knowledge, Power and Innovation in the Food Chain.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 31: 159–173.

- Pahnke, A. 2015. “Institutionalizing Economies of Opposition: Explaining and Evaluating the Success of the MST’s Cooperatives and Agroecological Repeasantization.” Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (6): 1087–1107. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2014.991720

- Paige, J. 1975. Agrarian Revolution: Social Movements and Export Agriculture in the Underdeveloped World. New York, .: The Free Press.

- Petersen, P. 2018. “Agroecology and the Restoration of Organic Metabolisms in Agrifood Systems.” In The Sage Handbook of Nature, edited by T. Marsden, 1448–1467. London: SAGE Reference.

- Poulantzas, N. 1974. Les classes sociales dans le capitalisme d’aujourdhui. Paris: Maspoero.

- RAD (Reseau agriculture durable). 2015. Résultats de l’observatoire technico-économique bovin-lait du réseau agriculkture durable, synthese 2015, exercise comptable 2014.

- Rambaud, P. 1983. “Organisation du travail agraire et identités alternatives.” Cahiers Internationaux de Sociologie LXXV: 305–320.

- Reijs, J. 2007. “Improving Slurry by Diet Adjustments, a Novelty to Reduce N Losses from Grassland Based Dairy Farms.” PhD, Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Rosset, P. M., and M. Altieri. 2017. Agroecology: Science and Politics, ICAS Small Book Series. Vancouver: Fernwood Publisher. (International edition: https://practical-action.org/10U-588QE-B869K6V111/cr.aspx).

- Saccomandi, V. 1998. Agricultural Market Economics: A Neo-Institutional Analysis of Exchange, Circulation and Distribution of Agricultural Products. Assen: Royal Van Gorcum.

- Scherer, F. 1975. The Economics of Multiplant Operation, Harvard University Press. Cambridge: Mass.

- Schermer, M. 2017. “From ‘Additive’ to ‘Multiplicative’ Patterns of Growth.” International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 24 (1): 57–76.

- Scott, J. C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Sevilla Guzman, E. 2007. De la Sociologia Rural a la Agroecologia: Perspectivas Agroecologicas. Barcelona, Spain: Icaria Editorial.

- Slicher van Bath, B. H. 1958. Een Fries landbouwbedrijf in de tweede helft van de zestiende eeuw. Wageningen: Agronomisch-Historische Bijdragen, vierde deel, Studiejkring voor de Geschiedenis van de Landbouw, Veenman en Zonen.

- Sonneveld, M. P. W. 2004. “Impressions of Interactions: Land as a Dynamic Result of Co-Production Between Man and Nature.” PhD thesis. Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- Stuiver, M., C. Leeuwis, and J. D. van der Ploeg. 2004. “The Power of Experience: Farmers’ Knowledge and Sustainable Innovations in Agriculture.” In Seeds of Transition: Essays on Novelty Creation, Niches and Regimes in Agriculture, edited by J. S. C. Wiskerke and J. D. van der Ploeg, 1–30. Assen, The Netherlands: Royal van Gorcum.

- Stuiver, M., J. D. van der Ploeg, and C. Leeuwis. 2003. “The VEL and VANLA Cooperatives as Field Laboratories.” NJAS 51 (1–2): 27–40.

- Swagemakers, P. 2008. “Ecologisch Kapitaal: Over het belang van aanpassingsvermogen, flexibiliteit en oordeelkundigheid.” PhD, Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Trotta, G., and F. Milana. 2008. L’operaismo degli anni Sessanta, da ‘Quaderni rossi’ a ‘classe operaia’. Roma: Biblioteca dell’operaismo.

- van der Kamp, A., and M. de Haan. 2004. “High-Tech Farm and Low-Cost Farm in the Netherlands: What is the Solution?” Paper for Djurhälso & Utfodringskonferens 2004, ASG/WUR, Lelystad.

- van der Molen, H., P. Kuijer, G. de Groene, J. Bakker, B. Sorgdrager, A. Lenderink, J. Maas, and T. Brand. 2018. Beroepsziekten in cijfers. Amsterdam: Nederlands Centrum voor Beroepsziekten.

- van der Ploeg, J. D. 1993. “On Potatoes and Metaphor.” In An Anthropological Critique of Development: The Growth of Ignorance, edited by M. Hobart, 209–227. London and New York: Routledge.

- van der Ploeg, J. D. 2013. Peasants and the Art of Farming: A Chayanovian Manifesto. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

- van der Ploeg, J. D. 2018. The New Peasantries: Rural Development in Times of Globalization. 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- van der Ploeg, J. D., D. Barjolle, J. Bruil, G. Brunori, L. M. Costa Madureira, J. Dessein, Z. Drąg, et al. 2019. “The Economic Potential of Agroecology: Empirical Evidence from Europe.” Journal of Rural Studies, doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.09.003.