ABSTRACT

There are not fixed conditions that make potential agricultural frontiers attractive to capital: different spaces and strategies are chosen in relation to previous failed experiments, including those strongly contested by social movements. Socio-environmental contestations can also inadvertently result in negative spillovers, or a kind of indirect land use change. I propose a concept of redirected land use and control change for cases with strategic adaptations by promoters of frontiers. I suggest three dimensions of adaptations – across spaces, political-administrative regimes and in forms of land appropriation – to apprehend the multi-scale politics of land grabbing, through the case of Matopiba in Brazil.

1. Introduction

Literature in the wake of the announced land grab rush after the 2007–8 financial crisis often naturalized capital as finally reaching ‘last frontiers’, giving special emphasis to the large-scale land deals in the African continent as evidence of a new wave of enclosures (Ince Citation2014). Since then, scholars have highlighted that many of the announced deals in Africa did not actually materialize (Cotula Citation2013) and that many other transformations were also occurring around the world (Edelman, Oya, and Borras Citation2013). Some authors have also emphasized how new frontiers can be made and remade, going through multiple waves of resource grabbing and transformation of social relations (Edelman and León Citation2013; Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018). The question remains, however, particularly with the current transnational reach of capital, why certain spaces are chosen over others and why many deals did translate into intense land use and control change when others did not.

Capital moves around and fixes itself in place for many reasons. Shifting around is a strategy in and of itself, particularly in this highly financialized and speculative era, in which purchasing and selling land is a key strategy for accumulation (Harvey Citation2003; Spadotto et al. Citation2020). Harvey through his concept of spatial – or spatio-temporal – fixes focused on how capital is shifted spatially to attempt to deal with recurring crises of overaccumulation. In his larger body of work, he recognizes that capitalist landscapes are also shaped by the interactions of different logics of capital and of states and by the rise of resistance to dispossession and other popular demands (Harvey Citation2003, Citation2014). In this paper, I turn my attention precisely to how political contestations and struggles also modulate the directions of capital and connect different potential frontiers across the globe, building on recent works that have focused on the role of politics and embedded histories in shaping the directions of land rushes (Alonso-Fradejas Citation2015; Wolford et al. Citation2013; Edelman and León Citation2013; Levien Citation2015).

New spaces for investment in land and agriculture are chosen based on many factors, including biophysical conditions, pre-existing infrastructure, and institutional contexts. I focus here on the role played by dynamic political struggles occurring on multiple scales – from local to transnational – and on the different types of adaptations that occur in response to and in anticipation of political contradictions. As highlighted by Li (Citation2015), transnational farmland investors engage in a business fraught with political risk and must take measures to secure legitimacy, both in relation to directly affected peoples and to civil society and state actors around the world. I will address three types of adaptations by promoters of new frontiers – shifts across space, across political-administrative regimes and across regimes of land tenure – which can help us to apprehend a high fluidity of strategies and directions of capital in the intersection with processes of legitimation.

The ways in which we visualize the possibilities both for contesting and promoting land grabs change if we consider potential agricultural frontiers relationally. It becomes clearer that there are not set conditions that make frontiers attractive – they become more attractive, or less attractive, in relation to other possible frontiers. Moreover, specific mechanisms through which capital operates emerge in relation to procedures that have previously failed or been contested, not only in that territory but also as imported lessons from other places. Transnational companies can also use the possibility of removing their investments to other sites or sectors as a key form of leverage against opposition and as a guarantee against potential issues they encounter (Gill and Law Citation1989).

The possibilities in each frontier are thus influenced by conditions in other frontiers; and contestations in one sector or space might lead to the shift of the associated investments to another sector or space. The requirements for sustainable sourcing in biofuels in the European Union led to European rapeseed previously used for food to be increasingly converted to biodiesel, for instance. But this also allowed the palm oil tied to land grabbing in Indonesia which was being criticized as an unsustainable biofuel source to simply fill the opened market gap as an ingredient in food sectors which didn't have the same regulation (Borras et al. Citation2016, 108). Similarly, as will be detailed in this paper, the critical attention and focus by environmental organizations on expansion of soy in the Amazon left the Cerrado region in Brazil relatively more vulnerable to land grabbing, revealing complex intersections between agrarian and environmental politics.

Sustainability literature has sought to further understand the possible unintended effects of conservation efforts across different spaces, introducing terms such as ‘leakages’, ‘spillovers’, ‘indirect land use change’ (ILUC) and the importance of ‘telecoupling’ to visualize interconnectedness (Ostwald and Henders Citation2014; Liu et al. Citation2015). These categories have facilitated the visualization of global connections and are often coupled with discussion of policies, but for several cases their use can suffer from a lack of political analysis of the adaptations themselves. Words such as ‘leakages’ or ‘indirect land use change’ can give the notion that these are indeed simply unintended effects of well-meaning efforts in complex systems. As this paper attempts to show, in many cases these changes are actually mediated and selected, as transnational corporations often redirect their sourcing to new frontiers when facing contestations in other places. That is, when analyzing relations of power and changes in land control coupled with changes in land use (Borras and Franco Citation2012), many of these processes are better represented as redirected land use and control change across the globe to ensure continued access to natural resources and increasing profits by powerful actors.

The Matopiba agricultural frontier, in northeast Brazil, provides an excellent case to explore the importance of a political framework analyzing multi-scale politics and connections across frontiers. Matopiba is the acronym most often used to describe the Cerrado portion of four states (Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia) in northeast Brazil being converted to intense agribusiness and extractive projects ().

Figure 1. Official delimitation of Matopiba (Embrapa Citation2015); my captions for states.

Matopiba has recently galvanized attention through social movement campaigns and in academic literature (Pereira Citation2019). Multiple Brazilian social movements have coalesced around the Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado since 2015 to call attention to the widespread destruction occurring in this region. Partnerships of Brazilian movements with international human rights organizations have also yielded fact-finding missions and a collective report on the human and environmental costs of land investments in Matopiba (FIAN International et al. Citation2018). In addition to agrarian movements, international environmental NGOs have also increased their attention to the Cerrado and have called upon traders and retailers to commit to stop purchasing commodities from deforested areas of the Cerrado (Manifesto Citation2017).

In part, this wave has been a reaction to the official announcement by the Brazilian Government in 2015 of Matopiba as a new prioritized region, calling it ‘the last agricultural frontier in expansion in the world’, taking up the ‘last frontier’ discourse as a promotional strategy (Planalto Citation2015). In the last year of Dilma Rousseff's Presidency before her impeachment, the government officially promoted Matopiba, planning to create different policies around it, based on studies published in 2014 by the Brazilian State Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa Citation2015). Moreover, this increase in interest has also been tied to emerging evidence of international investment in the region, including the uncovered presence of foreign pension funds involved in land speculation in South Piauí, such as TIAA-CREF and Harvard University's endowment fund (Pitta and Mendonça Citation2015; GRAIN and Rede Social Citation2018).

While these are important reasons for the increased international attention on Matopiba, the question remains of why it was relatively in the shadows before, among communities tracking global land grabs, since the massive socioecological transformations in the four states had actually been occurring for decades. The state of Bahia, especially, is already a more consolidated hub of agribusiness, following expansion in the 1980s. Meanwhile, the expansion of soy into Maranhão, Piauí and Tocantins gained speed in the mid-1990s and the early 2000s. Just between 2000 and 2014, over two million hectares were deforested in the area, with over 60% of agricultural expansion in Matopiba occurring over native vegetation (Carneiro Filho and Costa Citation2016, 9). The traditional communities and peasants living there have felt the impact of strangulation of their livelihoods and dispossession for decades. It is true that local social movements and researchers have already been following the destructive socioenvironmental impacts of industrial agriculture closely for many years (Paula Andrade Citation1995; Souza Filho Citation1995; Carneiro Citation2008; Paula Andrade Citation2012). Nonetheless, the previous relative obscurity of Matopiba and the challenges in scaling up contestations before 2015 are particularly relevant because they relate to its political viability, which enabled the confident declaration of the Brazilian government of a new frontier and the entry of foreign investors.

In this article, I explore three dimensions of adaptations that shaped Matopiba and allowed it to become politically and economically attractive to investors and state agencies up until the official announcement of the new frontier in 2015: the spatial shifts connecting Matopiba to other frontiers and differentiating processes within the region; the changes in political-administrative regimes and, finally, the shifts in forms of appropriating land. In the third section, I discuss the relevance of analyzing these dimensions for other cases as well in an era of high capacity for coordination and flexibility by agri-food transnational corporations.

This research is partly based on fieldwork conducted in August and September of 2017 in Maranhão and Piauí, through sixteen semi-structured interviews with key state officials, researchers and members of social movements as well as participant observation, participation in public hearings and interviews in visits to two peasant communities in Buriti (Maranhão) affected by soy expansion and to five affected communities in the municipalities of Santa Filomena and Gilbués (Piauí). The visits in Piauí were conducted as part of the Fact-Finding Mission in Matopiba organized by FIAN, the Social Network for Justice and Human Rights in Brazil (Rede Social) and the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT). I also conducted six additional interviews with officers of the Ministry of Agriculture, of Embrapa and of JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) in Brasília. While this paper looks at Matopiba as a whole, it focuses on the processes in East Maranhão and South Piauí, as two more recent frontiers within the region with considerable differences in their histories of political contestations.

2. The making of Matopiba

2.1. Early processes

The declaration of the area of 337 municipalities in Brazil, corresponding to the Cerrado biomeFootnote1 in the four states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia, as a unified frontier, under the name of Matopiba, was a political decision. This decision was technically supported by studies of Embrapa Strategic Territorial Intelligence Group in 2014 (Miranda, Magalhães, and Carvalho Citation2014) and was consolidated in a 2015 Presidential Decree that envisioned the creation of an Agricultural Development Plan for Matopiba (Decree Citation8447/2015). In fact, Matopiba is formed by diverse territories, with different histories, and even as an agribusiness frontier it has been amalgamated in different ways.Footnote2 Nevertheless, these states also share many features in common that are highly relevant to the frontier formation, including an abundance of legally ambiguous public lands and a cheaper land market (Pitta and Mendonça Citation2015), lower urbanization rates and higher poverty rates compared to the average of Brazil (IBGE Citation2010) and a peripheral position relative to the economic and political centers of the country.

A significant part of Brazil's interior, especially in the Center-South, has already undergone the conversion of large portions of land to industrial agriculture in previous decades, with soy having consolidated itself as Brazil's main production and exportation crop. While the central and southern states still dominate the production of soyFootnote3, Matopiba increased its share of Brazil soy production from 5.6% in 2001/2 (CONAB Citation2003, 22) to almost 11% in the 2016/17 season (CONAB Citation2017, 116).

It was largely in the twentieth century that a national project of intentional occupation of these hinterlands was formed, with its strongest expression under the military dictatorship of 1964–1985, which embraced a project of conservative agricultural modernization and actively encouraged farmers from the South of Brazil (commonly descendants of European migrants) to take over lands in the center and north of Brazil, supplanting the traditional occupants of these regions (Delgado Citation2010). Soy gained an increasingly important role in Brazil's agriculture after the selection of new seed varieties suitable for tropical climates, largely developed by Embrapa, created in 1973 (Schlesinger Citation2006, 17).

Two key programs expanding agriculture into the Cerrado in the 1970s were Polocentro (Program of Development of the Center-West Region) and Prodecer (Program of Japanese-Brazilian Cooperation for the Agricultural Development of the Cerrado). These, along with other key programs and infrastructure projects from the military regime, such as the construction of road BR-163, helped propel which would become the most consolidated agribusiness states, such as Mato Grosso and Goiás (Aguiar and Porto Citation2018). In the context of a soy moratorium by the United States in 1973, purchasing countries became more interested in developing cultivation in South America, and Japan pursued direct cooperation with Brazil (Schlesinger Citation2006). The second and third phases of Prodecer reached three states of Matopiba and helped propel the soy frontiers also there in the 1980s and 1990s.

Early incursions of intensive agriculture into Matopiba were also connected to the programs of the military dictatorship directed to the Amazon. These included Great Carajás Project, launched in 1980 and based around the iron mining project led by Companhia Vale do Rio Doce in the state of Pará and the construction of Railway Carajás that led to a port in São Luís (Maranhão). The government offered several economic and fiscal incentives to associated enterprises, which helped spur a charcoal production boom and first plantations of eucalyptus and sugarcane in the East of Maranhão in the 1980s (Paula Andrade Citation1995).

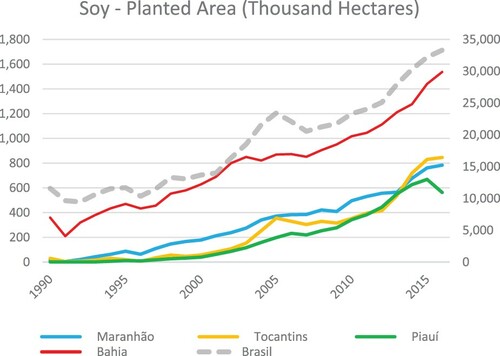

Through different policies, the Brazilian state encouraged specifically the expansion of soybean into the states of Maranhão and Piauí. In 1991, Companhia Vale do Rio Doce proposed the North Corridor of Exportation Program, pointing to the advantages of using the multimodal transportation infrastructure to export soy from Maranhão, Piauí and Tocantins (Carneiro Citation2008, 86). Whereas Bahia was the first Matopiba state in which soy plantations expanded and continues to have a larger production compared to the three other states, the south of Maranhão also had a quick expansion in the 1990s and has developed an important agribusiness hub around the city of Balsas (Carneiro Citation2008) ().

Figure 2. Expansion of planted area of soy in the four Matopiba states (own elaboration, based on data of PAM/IBGE). Two scales: four states (left); total in Brazil (right).

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, southern farmers who had already installed themselves previously in the East of Maranhão started planting soy, also with support of Embrapa. In the state of Piauí, production of soy also took off in the 2000s, leaping from 91.014 tons of soy in the state in 2002 to 308.225 tons in 2003 (PAM/IBGE Citation2017).

As can be seen in the examples of the previous establishment of eucalyptus and sugarcane in Maranhão, the arrival of southern farmers and the appropriation of lands – usually the illegal appropriation of public unclaimed lands, called grilagemFootnote4 – often preceded the expansion of soy. Indeed, much of the grilagem in Maranhão and Piauí occurred in the 1970s and 1980s before the soy boom, not only due to the encouragement of ‘colonization’ by the Federal Government, but also with the participation of state governments and local elites in a frenzy of land appropriation (Alves Citation2009). Land itself has also gained value as a commodity in Matopiba and land speculation has increased in the last years, with the installation of specialized land companies (Pitta and Vega Citation2017).

Expansion of areas of soy in Matopiba gained traction under the commodity boom of the 2000s, under the Brazilian government's reembraced strategy of basing growth on exportation of grains and oilseeds under the Workers’ Party administration (Delgado Citation2010). Although there had been hints of renewed interest in a policy for the Matopiba region through the proposal of the Center-North Corridor in 2012, a more concrete measure only appeared in 2015, with the announcement by the Federal Government of the intention to create a Plan of Agricultural Development, a Managing Committee and a Development Agency for Matopiba. This was largely led by the Minister of Agriculture Kátia Abreu, herself a large farmer from Tocantins, already in a period of political instability that preceded the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff. While many of the plans were interrupted by the impeachment, the announcement by the government attracted further attention both of potential investors and of social movements critical of the unbridled expansion of agribusiness capital.

2.2. Socio-environmental consequences and emerging contestations

The territorialization of industrial agriculture in Matopiba has largely occurred at the expense of other beings previously occupying those lands, with uniform monocultures supplanting biodiverse Cerrado ecosystems. These complex ecosystems were largely co-managed and inhabited by traditional, indigenous and peasant populations. All the communities visited in Maranhão and Piauí had been established at least for several decades. Both in the East of Maranhão and South of Piauí, the communities have traditionally relied on diverse sources of livelihoods, including plantation of subsistence crops, raising animals, and extracting fruit and other forest products, with limited commercialization and occasional wage labor, such as through seasonal migrant work in other states.

While there have been cases of direct expulsion and multiple reports of threats and violence committed against these communities in the past decades by land grabbers, many researchers and my own fieldwork have pointed to the predominance of a process of gradual strangulation of communities in Matopiba (Souza Filho Citation1995; Pitta and Mendonça Citation2015; Pitta and Vega Citation2017). Due to the geographical formation of these areas, industrial agriculture has largely spread across the higher plateaus, which communities historically used for extraction of forest products, hunting, and free grazing of livestock, while they typically live in lowlands. However, across the years, in addition to the difficulties caused by the loss of their commons and reserve areas, communities have struggled to remain on their land due to growing ecological conflicts which seep into the lowlands, such as reduction of water availability, reduction of native land animals and fish used as food sources, contamination by pesticides and loss of food crops due to new pests. These effects, along with the lack of basic infrastructure in these regions and opportunities for income generation, have pushed communities to sell their lands or to move to municipal centers. Even though some young men are employed in the new soy plantations – especially in strenuous seasonal work, such as removing roots of cutdown trees – there are few opportunities for labor incorporation in the farms.

Peasants interviewed in Piauí often have to balance their frustration over the negative effects that they are suffering with difficulties in pointing fingers to the companies and farmers. Denouncements might not only lead to violent retaliations, but also to the loss of ‘good neighbor’ relations that might have been formed over the years. Some large farmers fulfill roles of patronage and companies operating in the area often promise and/or enact small improvements such as building schools or income generation projects.

Still, in the communities visited in Maranhão and Piauí, even peasants who had not had much previous contact with organized resistance, generally formulated strong acknowledgement of loss of their commons over the years and feelings of disenfranchisement. Effective reactions to such a forceful and state-supported advancement of industrial agriculture largely depend on the possibility of regional interlinkages and the capacity to scale up and connect with organizations at a national and/or international level. In the past years, after the announcement of the Matopiba frontier by the Federal Government, more movements and organizations have turned attention to the region.

Many factors influenced the difficulty in scaling up contestations previous to 2015. Some factors are not specific to Matopiba but have to do with the erosion of capacities of contestation by social movements in Brazil as a whole in the last decades. The factors pertaining specifically to Matopiba, in turn, can be better understood in relation to other places and previous regimes, as we shall see in the next three sections. Still, some initial preliminary generalizations can be made.

First, networks of contestation are held back by geographical isolation in Matopiba. The affected areas are often hundreds of kilometers from state capitals, where many organizations and state institutions are based. Furthermore, there is a strong historical symbolic process of rendering the Cerrado and its traditional and indigenous peoples invisible. Coordinators of the Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado point out that there is a need to rescue the image of the Cerrado as a complex biome inhabited by traditional populations, as the identification of the region as the grainery of Brazil has largely already been naturalized.

Also, the history of the formation of rural social movements in Brazil is pertinent to the capacity of multi-scale resistance in Matopiba. Brazil's largest and most influential movement, the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST), started in the South of Brazil and has expanded its territorial base upward (Fernandes Citation2010, 164–169), and still has a weaker presence in some of the regions of Matopiba. Moreover, while MST was largely built around the demand for land reform, in Matopiba, struggles have often been to avoid dispossession and to recognize their traditional territories and ways of life, considering many rural communities have been settled on legally unclaimed public lands for decades.

In recent years, more socio-territorial movements in Brazil have formed around collective identities related to diverse traditional forms of usage of natural resources, known as ‘traditional populations and communities’ (Almeida Citation2008). In addition to and in dialogue with movements based around traditional occupation of territories in Matopiba, the northeast of Brazil has also had a stronger expression of church-based movements (Poletto Citation2010). Comissão Pastoral da Terra (CPT) is one of the most expressive organizations that supports rural communities in the Matopiba states. Other rural social movements, human rights organizations, labor unions, academics and some state officers also engage in constellations of contestations to land grabbing and environmental degradation.

This type of powerful synergy has actually occurred in past decades in East Maranhão, where there has been previous scaling up of contestations. In reference to the conflicts concerning the expansion of charcoal production, eucalyptus plantations and sugarcane around the Great Carajás Project in Maranhão in the 1990s, several unions, church-based entities, researchers and civil society organizations formed networks of resistance and facilitated visits of state officials to the areas to verify the violations (Paula Andrade Citation1995). In the 2000s, with the expansion of conflicts around soy, once again a network of resistance was formed, leading to the constitution of a Forum in Defense of Life in the Baixo Parnaíba and propelling a mission by the Brazilian Platform of Economic, Social, Cultural and Environmental Human Rights in 2005. One key actor in these processes of resistance has been the Sociedade Maranhense de Direitos Humanos, a human rights organization that has given support to communities in East Maranhão since the 1980s. In addition, researchers of the Federal University of Maranhão have played the effective role of scholar-activists in the last decades, conducting research with several affected communities (Paula Andrade Citation2012). The monitoring of violations by activists and researchers has often connected with legal contestations to ensure territorial rights of the communities and to halt violations by agribusiness actors, including public lawsuits filed by prosecutors of the Public Ministry to hold companies and state agents accountable.

The possibilities for this type of network formation have been very different in South Piauí previous to 2015. The region of agribusiness expansion in Piauí is much further from the state capital, compared to East Maranhão, making the connection with organizations more challenging. Moreover, the communities typically live in highly isolated places and are more scattered compared to the East of Maranhão. Nonetheless, church actors, labor unions and CPT agents have also engaged with these communities. In 2009, social movements organized a Caravan of the Cerrados of Piauí to denounce the expansion of agribusiness. Pressure has also increased in Piauí to address the widespread illegal appropriation (grilagem) of public lands in the state. In 2012, prosecutors of the Public Ministry of Piauí formed a special group to combat grilagem and a specialized Agrarian Court was formed to judge cases of land conflicts, eventually identifying and blocking dozens of irregular estates of tens or even hundreds of thousands of hectares. It is now, however, with the formation of international campaigns, that the south of Piauí is receiving much more visibility.

Finally, the formation of alliances and escalation of contestations is not a straightforward process. Since 2015, international environmental NGOs have also significantly increased their attention in the region. However, although socio-environmental processes are intrinsically linked in Matopiba, some streams of environmentalism can directly or indirectly translate into exclusion of traditional communities and support further expansion of agribusiness (Franco and Borras Citation2019). On the other hand, many rural social movements in Brazil are still in the process of incorporating ecological discussions. The Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado, launched in 2016, has been an attempt to build a socio-environmental progressive platform.

All these factors, while important, still give us a narrow picture of why Matopiba was considered politically viable by the promoters of the new frontier. We now approach larger factors that have to do with Matopiba's relation to other frontiers and to changing political-administrative regimes and forms of land appropriation in Brazil.

2.3. Shifts across space

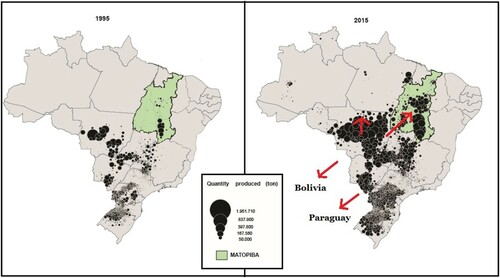

The technical documents produced by Embrapa in 2014 justified their choice of delimitation of Matopiba primarily on the criteria of selection of the Cerrado area of the four states (Miranda, Magalhães, and Carvalho Citation2014, 9). At first glance, the expansion into Matopiba might seem like a logical direction from the standpoint of agribusiness, continuing policies that prioritized territorialization of soy into the Cerrado of Brazil. However, looking at the map below of production of soy in Brazil in 1995 and 2015, one can see that soy has territorialized not only towards Matopiba, but also upward in the central state of Mato Grosso. Moreover, soy producers in Brazil have also expanded to other countries, especially to Bolivia and Paraguay (Borras et al. Citation2012), which border some of Brazil's states with most intense grain/oilseed production ().

Figure 3. Production of soy per municipality in Brazil in 1995 and 2015. Data: PAM/IBGE Citation2017. Organized as map by Lorena Izá Pereira; my arrows.

The expansion of soy in the north of Mato Grosso, however, has provoked multiple contestations, since it is a transition between the Cerrado and Amazon biome, which has been the object of strong national and international concerns over deforestation, especially since the 1990s. In 2004, data on deforestation in the Amazon showed alarming loss of vegetation that year, attracting the attention of international NGOs, such as Greenpeace, which released reports showing the connection between the cultivation of soy and the loss of the Amazon forest (Greenpeace Citation2014).

The pressure from civil society organizations also led to some political agreements around slowing down deforestation of the Amazon. One of the most influential agreements was the Soy Moratorium of the Amazon signed in 2006, through which traders and retailers committed not to buy soy from deforested areas (Greenpeace Citation2014). The new national Forest Code of 2012 ultimately reduced environmental protection in Brazil – including by giving amnesty to certain environmental violations committed before 2008 – but kept the standard of the previous Code of stricter restrictions within the Legal Amazon, especially in area of forests, compared to other biomes (Law 12.651/Citation2012). It is true that industrial agriculture expansion into the Cerrado since the 1970s had benefitted from the negative imaginary around the region and its people and was already then portrayed as a more easily manageable alternative to the Amazon (Silva Citation2009, 64–65; Aguiar and Porto Citation2018, 11), but this contrast became more prominent with the gained importance of transnational environmental and agrarian politics in the late twentieth century.

Especially in the twenty-first century, in the context of stricter regulations and more contestations around the expansion of soy in the Amazon, Matopiba consolidated itself as a more overtly ‘viable’ option – even though some of its regions are more vulnerable to water stress (Barros Citation2016). Other researchers have pointed to the connection between the shift of soy expansion to Matopiba and the contestations around expansion in the Amazon (Oliveira and Hecht Citation2016, 270; Hershaw and Sauer Citation2017) and many of the environmental organizations that were involved in pushing for the soy moratorium are now recognizing this ‘leakage’ effect and have turned their attention to the Cerrado, pushing for a similar conservation agreement there (Manifesto Citation2017). Scientists working with telecoupling frameworks in sustainability have also analyzed through models that two supply-chain agreements on soy and cattle in the Amazon were connected to reduced deforestation in the targeted area, but also to increased deforestation in the state of Tocantins in the Cerrado, which they considered a spillover effect (Dou et al. Citation2018).

In this sense, the Embrapa 2014 studies can also be interpreted as an attempt to further legitimize the frontier compared to contestations elsewhere. One document openly states: ‘Changes in the use and occupation of land in Matopiba possess characteristics differentiated from what was, for example, the process of expansion of agriculture in the south arc of the Amazon, in the 1970s and 1980s, characterized by deforestation’Footnote5 (Miranda, Magalhães, and Carvalho Citation2014, 2).

The promotion of Matopiba has also been connected to potential frontiers outside of Brazil. In the 2000s, Brazil was also involved in agricultural cooperation programs with African countries. ProSavana, a triangular cooperation with Japan in Mozambique, was launched in 2009, in an attempt to replicate previous Brazilian-Japanese cooperation in the Cerrado, with evidence also emerging that Brazilian soy producers were interested in starting operations in Mozambique under the umbrella of the program. However, multiple contestations to ProSavana emerged, linking social movements and researchers from Brazil, Japan and Mozambique, which led to the Campaign ‘No to ProSavana’ and, along with other factors, pushed the actors in the cooperation to adapt their plans and halt much of the cooperation (Aguiar and Pacheco Citation2016). In addition to rising transnational contestations, potential investors saw Mozambique's land tenure laws – under which land is state-owned and rights to use are ceded – as a possible factor of legal uncertainty and obstacle to speculation with land, and were also faced with conflicting demands over the existing logistical infrastructure which they wished to benefit from, historically used for transportation of people (Aguiar and Porto Citation2018). Difficulties encountered in Mozambique might have been a possible additional factor encouraging more investment and attention around Matopiba in recent years, since many of the actors that were involved in Prodecer and ProSavana and who are increasingly interested in Matopiba coincide. These actors include not only the governments of Brazil and Japan, but also private companies of each country.

In 2014, 2016 and 2017, the Ministry of Agriculture of Brazil held events with the Japanese government called Dialogues Brazil-Japan on Agriculture and Food, in which possibilities of investment and cooperation in Brazil have been further discussed, with growing emphasis on Matopiba, in contrast to previous focus given in seminars between Brazil and Japan to investments in Africa (Câmara Citation2011; MAPA Citation2016). The strategic alliance between Vale and Mitsui, a Japanese trader, has been present both in plans for Mozambique and for Matopiba, as a key infrastructure and logistics operator in Matopiba is VLI, a holding formed by Vale, Mitsui and a Brazilian state-controlled investment fund.

Spatial shifts by agribusiness capital in response to contestations do not necessarily implicate leaving or avoiding an area completely, but can be restricted to shifts by certain sectors or actors. The moratorium of soy in the Amazon not only left a relative space open for soy in other biomes, but also diverted attention from other agricultural sectors. Deforestation in the last years in the Amazon has largely been led by livestock, and, as the expansion of soy typically pushes livestock to new areas, degraded pastures are often later converted to soy plantations, in a vicious cycle (Domingues and Bermann Citation2012).

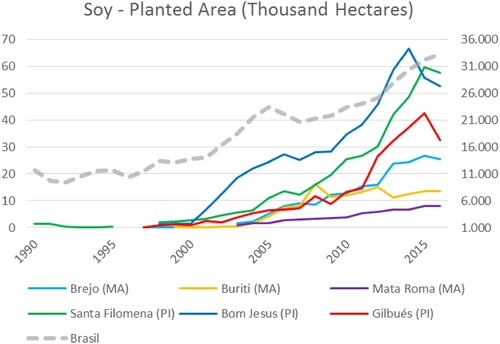

There are also indications that spatial leaps of agribusiness investment have also occurred within Matopiba, in relation with the conjuncture of contestations described in the previous section. As the graph below shows, in municipalities in south Piauí, where there have been fewer possibilities for scaled-up reactions, the area of planted soy expanded quickly, much above the general rate in Brazil. In the municipalities in East Maranhão, soy has advanced at a more moderate pace. One cannot simply make a straightforward comparison between the contestations or lack thereof and speed of expansion of soy in the two states, because there are multiple other differences between these regions to consider, such as the difference in sizeFootnote6 of their municipalities and the fact that soy shares space in Maranhão with eucalyptus plantations, estimated to cover 30–40 thousand hectares (Souza and Overbeek Citation2013) ().

Figure 4. Soy production in municipalities of Maranhão (MA) and Piauí (PI) (own elaboration based on data from PAM/IBGE Citation2017). Two scales: six cities (left); total in Brazil (right).

All these particularities notwithstanding, there is also evidence that there was a mismatch between initial agribusiness expectations for soy advancement in East Maranhão and the actual trajectory. In this sense, legal and political contestations seem to have played a role in propelling spatial shifts outwards. In 2003, Embrapa estimated that around 500–600 thousand hectares in East Maranhão could be used for intensive farming (Monteles Citation2003). In 2015, however, soy occupied a little over 70 thousand hectares in the region (PAM/IBGE Citation2017). According to the Secretary of Agriculture of Maranhão, the region still has potential for soy expansion, but it will be a slow growth compared to other possible new areas in Maranhão, due to the prevalence of small plots of land (Honaiser, interview 9 August 2017). Nonetheless, East Maranhão has also been a site of grilagem and companies have tried to irregularly appropriate large plots of land in the past. SLC Agrícola, one of the largest commodity companies in Brazil, acquired a large farm in Buriti for soy called Palmeira in 2000, but sold it in 2010, reporting the area to be 14.625 hectares in extension (Olivon Citation2012). This exit seems to be correlated to the growing reactions to grilagem and environmental violations in the region. SLC was also one of the companies in Buriti to suffer a lawsuit for environmental damage by the Public Ministry in 2007. While purchasing and selling lands is a strategy increasingly used by SLC in order to profit from real estate speculation along with the production of commodities (Spadotto et al. Citation2020), SLC sold this land when they were still in a period of aggressive expansion and the company ended up leaving the northeast of Maranhão completely after this sale, not maintaining or purchasing new lands there as it has done in other parts of Matopiba. With the exit of larger companies, the main apparent actors involved in soy production in East Maranhão continue to be southern farmers, rather than larger companies (Gaspar Citation2013). This contrasts with the South of Piauí, which still has the presence of larger companies, such as Radar and SLC.

The existence of logistical and storage infrastructure also plays an important role in the possibility of spatial shifts, since their existence both facilitates frontier expansion, often propelling production corridors around key routes, and new infrastructure development itself is commonly propelled by agribusiness demands (Aguiar and Porto Citation2018). The accelerated expansion in South Piauí compared to East Maranhão is also interesting considering the latter's closer proximity to the Port of Itaqui. Although it increases transportation and logistics costs for some economic actors, expansion in relatively isolated areas can also serve to hide violations and can open demands for new logistical corridors that other agents might benefit from, such as construction companies.

Finally, it is important to note that spatial shifts by certain agribusiness actors to leave areas in which tensions have mounted might rely on leaving frontmen in place or waiting for the ‘dirty work’ to be executed by actors that are less traceable. This has often happened in the process of grilagem in Matopiba, in which grileiros first use violence to remove people and later sell the regularized land to companies (Pitta and Mendonça Citation2015). This might mean that some shifts across space can be otherwise interpreted as a shift across time (a postponement), as companies can return or appear more visibly after the situation has been ‘subdued’.

Harvey's concept of spatial and spatio-temporal fixes by capital can provide a broader framework to understand how capital moves and creates new frontiers to attempt to deal with contradictions of overaccumulation (Harvey Citation2003; Pereira Citation2019). This section attempts to show that other types of contradictions can also push spatial shifts and that it is important to develop complimentary frameworks that give more attention to the political mediations in the choice of new territories of investment.

2.4. Shifts across political-administrative regimes

The perceived political viability of Matopiba and the challenges in scaling up contestations also need to be interpreted through the prism of transformations in the political-administrative regime in Brazil in the last decades.

The first large development programs facilitating the entry of agribusiness capital into Matopiba were launched under the Brazilian military regime, during which contestations were violently repressed and policies of colonization of land often relied on massacres in the countryside. The exponential increase in soy in Matopiba, and particularly in the two areas considered, occurred mostly under the Workers’ Party (PT) governments (2000–2016). While there were some new progressive policies for land and agriculture, such as those supporting small-scale farming, the much-awaited redistributive large-scale land reform did not occur and the alliances of representatives of PT with sectors of agribusiness intensified across the years (Fernandes Citation2010; Sauer and Mészáros Citation2017).

With the election of PT, there was an increased sophistication in forms of gathering consent and restricting need for coercion of the state. Traditional representatives of labor (associated with PT) and traditional representatives of finance came together to co-manage capital through use of public funds, often through managing pension funds of state companies and through the National Bank of Economic and Social Development (BNDES) (Oliveira Citation2003).

Through neo-developmentalist policies such as the Program of Acceleration of Growth (PAC), the Federal Government helped finance key agribusiness infrastructure demands in Matopiba, including the extension of the North–South Railway and the construction of the Terminal of Grains of Itaqui. Vale, previously a state company, was associated with projects of agricultural modernization in Matopiba in the 1980s through Great Carajás Project and in the 1990s through the North Corridor of Exportation Program. In 1997, Vale was privatized, but majority control was turned over to Valepar, in turn controlled largely by state company pension funds and BNDES (Coelho, Milanez, and Wanderley Citation2017).Footnote7 The government also injected money through public fund FI-FGTS into the formation of the logistics company VLI with Vale's participation. Vale has continued to have an important role attracting new companies to the region. It made, for example, an agreement with pulp and paper company Suzano in 2009 selling 85 thousand hectares of land in Maranhão and giving special conditions for Suzano to use Vale's railway system (Vale Citation2009).

It is difficult to know the full extent of involvement of the Federal Government in key operations in Matopiba during the PT governments, since the state was able to influence directions not only through direct federal investment programs, as was done in infrastructure, but also more indirectly, such as through the participation of state or workers’ funds in company boards. The fact that PT and managers of workers’ funds co-managed this process under a banner of national development also meant that actors of the Brazilian Left that might have contested it at another time were actually co-participants. The key role played by national companies and farmers in Matopiba connected also to another trend that overshadowed what was occurring there: many contestations of the land rush in Brazil after the 2007–8 crisis were concerned primarily with risk of foreignization of land, as was criticized by Oliveira (Citation2010).

While other researchers have pointed to the importance of not narrowing the discussion of land grabbing in Brazil to foreignization (Sauer and Borras Citation2016), it is still an angle that tends to attract more attention. The discovery of investments by foreign pension funds, such as TIAA-CREF, in land in Matopiba (Pitta and Mendonça Citation2015) has been one of the triggers of new contestations to agribusiness and speculation in the region.

Finally, another factor potentially obscuring processes in Matopiba tied to national (neo-)developmentalism has been the attenuating effects of the income redistribution and social welfare policies under PT. The four Matopiba states are among the poorest states in Brazil, and their populations have greatly benefited from welfare programs, with significant alleviation of severe poverty (IPEA Citation2010). While the peasant way of life has been strangled and livelihoods have certainly been compromised with the expansion of agribusiness, government transfer programs cushioned the gradual loss of control over resources and might have prevented reactions from below or a worse social catastrophe. In the last years, Piauí and Maranhão have also had state governments in hands of PT or their allies. Thus, elements of the dual strategy of coupling socially progressive policies with the encouragement of agribusiness also occurred at the state level.

Many of these shifts were, in fact, preventive of scaled-up contestations. While agribusiness capital ultimately benefited from this conciliatory conjuncture, many of its sectors also continued to lobby for the further removal of environmental protection and territorial rights of traditional populations and to deploy once again more direct coercion to guarantee their interests – as has occurred under the Presidency of Michel Temer and, even more sharply, under Jair Bolsonaro.

Even as many countries in the world turn once more to the far-right, the analysis of possible shifts in political-administrative regimes intertwined with frontier-making alerts us to avoid assumptions about capital necessarily targeting more ‘vulnerable’, ‘weaker’ or more authoritarian states for land grabs. Sassen (Citation2013), for instance, analyzed land grabs as processes of partial, emergent denationalization, focusing on sub-Saharan states facilitating sales of land to foreigners, constrained and disciplined by external debt. While these have indeed been important factors in several cases, the shifts in Matopiba point not only to the possibility of co-participation of states (Wolford et al. Citation2013), but also to potential advantages for capital in partnering with states with stronger capacities for balancing imperatives of economic accumulation and political legitimacy (O’Connor Citation1973).

Borras et al. (Citation2018) noted also that, while there had been many studies of Chinese land investments in other countries, there had until then been fewer studies of crop booms and foreign investments in China itself, possibly reflecting tendencies within the literature to see certain investment paths as unidirectional, when in fact they are more fluid and occur in multiple directions. As stated by the authors, ‘the fundamental logic of capital is that it will go wherever it can generate profits, regardless of nationality and national borders’ (Borras et al. Citation2018, 136). This more fluid logic of capital, of course, constantly interacts with and can clash with more territorial and state-based logics of power, including geopolitical and protectionist interests (Harvey Citation2003). Nonetheless, in this era of high transnational mobility of capital and commodities, it can be helpful analytically to avoid strong assumptions of trajectories of investments and to acknowledge the flexibility of political-administrative forms associated with land grab rushes in response to previous historical conjunctures.

2.5. Shifts across land tenure regimes

Legal possibilities of land acquisition and tenure, and ways to bypass them, have also been a central changing factor enabling the Matopiba frontier. While also connected to political-administrative regimes, they are addressed here as a separate shift, specifically related to forms of grabbing land. As stated previously, the expansion of soy in Matopiba has frequently relied on the grilagem (illegal appropriation) of untitled public lands. A strong frenzy of grilagem started in the 1970s and 1980s in Maranhão and Piauí, often with the acquiescence or co-participation of local elites and the state governments (Alves Citation2009). Under redemocratization, pressure increased to restrain widespread grilagem, with the constitutional obligation of social function of land and the establishment of more mechanisms of oversight. The Land Law of Maranhão of 1991, for example, established the preference of acquisition of public land for those traditionally occupying an area of under 200 hectares and created stricter conditions for titling large lands. Mounting conflicts also led to the creation of a court specialized in agrarian conflicts in Piauí in 2011 and a specialized agrarian prosecution in Maranhão in 2013. Increasingly, land titling and regularization have also been encouraged in areas with vast quantities of officially unclaimed lands, such as through a partnership of the state of Piauí with the World Bank to promote land regularization.

In this new context, there have been shifts in strategies of appropriation of land by agribusiness, which has turned to more sophisticated forms. Some examples witnessed by activists interviewed in the region have involved using corrupt community members, union leaders or lawyers, who request land titles at the state land institute claiming to represent peasant communities and later sell the bundle of titles to entrepreneurs. Land titling has often been distorted as a mechanism to legalize the claims of land grabbers, rather than those of the communities that have been there for decades. Thus, instead of straight-out forgery of documents to appropriate immense plots of land, actors have often used peasants as conduits to gather regularized private titles.

Moreover, in recent years, environmental requirements for landowners have been subverted and used to appropriate land. This matches a larger global trend, identified as ‘green grabbing’ (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2012). Brazilian Forest Code (Law 12.651/2012) obliges that each property in the Cerrado biome (outside of the Legal Amazon) set aside 20% as a ‘legal reserve’ for environmental protection.Footnote8 In the communities in Maranhão and Piauí, there have been cases of peasants suffering intimidation and legal action by farmers claiming that the peasants’ land constituted their environmental reserve. In these regions, soy farmers have typically deforested the entire plains they originally appropriated and recently have moved to claim the area preserved by the traditional populations – the lowlands which they have been able to retain – as their reserve. Another subversion of environmental law for the purpose of grilagem has occurred through CAR, the Rural Environmental Cadastre, a new national electronic registery mechanism created by the 2012 Forest Code (Law 12.651/2012, Art. 29). Although CAR is an instrument of environmental monitoring and not of tenure, lawyers working with social movements I interviewed and other researchers are noticing that, in practice, it is being warped as ‘proof’ of land possession for land grabbers (Vecchione Goncalves Citation2018).

Given the context of gradual strangling of livelihoods, even the correct land titling of traditional communities might over time lead to the transfer of more land to the hands of agribusiness through piecemeal sales. Members of rural social movements involved in the 2017 International Fact-Finding Mission in Matopiba shared similar concerns around the new Land Law of Piauí of 2015, which has been titling land to larger farmers and has also been fragmenting communal territories through emission of individual land titles, rather than the recognition of collective traditional territories.

Strategies of agribusiness to appropriate land have thus varied from the period of unbridled grilagem and more violence to also taking advantage of land titling of peasants and of environmental laws, although this might again change with the shift in national political regime.

These shifts point once more to the historical embeddedness of mechanisms used for frontier expansion and land grabs, including in land tenure regimes. The existence of countries with state-owned lands in Africa in the early land rush in the 2000s initially appeared to be an advantage to potential investors, since thousands of hectares could easily be brokered at once for cheap prices by states; later, as in the case of Mozambique, this turned to be considered a possible disadvantage, generating legal uncertainty (Aguiar and Porto Citation2018). As noted by Li (Citation2015), while transnational investors might try to legitimate their land deals through market, law or by force, none of these strategies provide definitive means to exclude other claimants to land, and the work of legitimation is always an ongoing process, which might combine or alternate between strategies.

It is to the importance of considering politically-mediated shifts in the making of frontiers, beyond the case of Matopiba, that the next section turns its attention.

3. The global politics of making and contesting frontiers

The three shifts described above enabled the assumption of political viability by the promoters of the Matopiba frontier, and they were built from the interplay of interests and adaptations occurring on multiple scales – foreign, national, regional and local. Some adjustments were more planned by powerful actors in liaison with each other; whereas others were patterns that emerged more gradually from experiments, toing and froing, and larger changes in context.

Since the announcement of the new frontier by Brazil's government in 2015, the conjuncture has changed significantly, not only with the rising transnational attention by human rights, agrarian and environmental organizations to Matopiba – propelling new negotiated strategies in the regionFootnote9 – but also with the larger change in Brazil's political regime to more authoritarian governments, which have once more reduced environmental restrictions in the Amazon and facilitated the use of violence against social movements (Casado and Londoño Citation2019).

While the descriptions of adaptations in this paper are embedded in the local, previous conditions within the subregions of Matopiba and focus on shifts occurring up until 2015, the three dimensions can provide a frame of reference for other cases and periods, potentially facilitating future comparative work on the relative attractiveness of frontiers to capital and effects of contestations. The findings here link to a larger picture regarding global land grabbing and its current conditions, and the need for future more interconnected and multi-scale research.

In first place, the findings cast further doubts on fatalistic and deterministic explanations that emerged mostly around what Edelman, Oya, and Borras (Citation2013) identified as the initial ‘making sense’ period of the global land grab literature, that saw capital as reaching the final, unreached frontiers. Initial studies and reports often saw African countries as the main target for global land grabbing, since the Green Revolution and massive land dispossession had not reached there on the same scale as other continents (Moyo Citation2011; Oakland Institute Citation2011, 4; Cotula Citation2013). Research in following years, however, showed the existence of widescale land grabbing occurring heavily across the globe, including in Latin America (Edelman, Oya, and Borras Citation2013, 1519). More than an issue of partial data, however, early research possibly had misleading assumptions.

First, they sometimes naturalized the notion of ‘frontier’ as a locus that capital has not yet reached, when, indeed, many of the places with land grabs have already seen the penetration of capital in land and agriculture through other forms, or have actually suffered multiple previous incursions (Tsing Citation2003), and cycles of dispossession – as has happened in many subregions in Matopiba itself, which has had previous cycles of cattle raising, for instance. Second, the discussions on new forms of imperialism have been key to highlight asymmetries of power between countries and possible new global tendencies of extraction and exploitation sponsored by states, including by emerging economies. These tendencies also intersect, however, with more fluid logics of capital and with the constant negotiation of multiple factors by promoters of frontiers. The picture from the ‘making sense’ period highlighted predatory land grabs on ‘weaker’ or poorer states as almost natural targets – when, indeed, many of the announced deals in Africa did not come to fruition, often due to disparities between the expected conditions and the actual local scenarios (Cotula Citation2013, 46). There are definitely many factors that make poorer countries in the global South more vulnerable to predatory investments and more violent land grabs, but the lack of preceding infrastructure, sedimented agribusiness sectors and strong state capacities in some cases can also present hassles to investors, who, after encountering them, might choose to shift back their investments to countries with more consolidated agribusiness sectors. This appears to have been partly the process with certain key actors involved in ProSavana directing their eyes back towards Brazil following the encounter with contestations in Mozambique and different legal and infrastructure conditions than expected.

Many dynamic factors play into what makes certain frontiers economically and politically attractive. Even in the context of rapidly advancing technologies seemingly capable of curbing biophysical contradictions, natural land conditions continue to be a key element influencing the potential of frontiers – conditions which were not deeply explored in this paper. The rising environmental contradictions and potential ecological exhaustion caused by intensive agribusiness itself might push for spatial shifts down the road, as might still happen in water-stressed Matopiba (Barros Citation2016). As has been highlighted here, institutional and legal frameworks matter greatly and can be both enabling and hindering conditions to, as well as potentially transformed by, the arrival of agribusiness capital. The shifts in the three dimensions of political-administrative regimes, in forms of land tenure appropriation and across spaces, as seen in Matopiba, provide a framework for visualizing how multi-scale actors are influenced by and influence the conditions in different sites, in a context of ongoing struggle.

Hence, a second relevant implication of the analysis of the shadowing of Matopiba is not only taking the importance of political clashes on a transnational scale seriously, but also considering the potential for so-called ‘spillovers’ into other territories or sectors following contestations in a certain area or sector.

In this sense, concepts from sustainability studies, such as ‘Indirect Land Use Change’, ‘leakages’ and ‘spillovers’, have been used as helpful tools to analyze connections and interactions between systems (Ostwald and Henders Citation2014; Dou et al. Citation2018), but these expressions might not fully translate the relevance of political strategies mediating the adaptations for all cases. These concepts for addressing interconnectedness are also being incorporated and re-signified within critical agrarian studies (Oliveira and Hecht Citation2016, 270; Franco and Borras Citation2019), including in the form of landscape perspectives to understand the relationship between multiple claims over natural resources in a territory (Hunsberger et al. Citation2017). But more work is needed to apprehend how these adaptations are coordinated in practice by corporations, state actors and other entities that constantly seek access to and control over more natural resources. For many cases, new environmental and social contradictions, such as the ones arising within Matopiba after more attention was given to the Amazon, can be better understood as redirected land use and control change – even if these redirections are mediated and formed by multiple actors and negotiations. This alternative term recognizes the influence of powerful actors in shifting contradictions and can help us understand not only the redirection of extractive projects to new spaces that are less contested or are deemed less risky by promoters of frontiers, but also their redirection to new strategies and mechanisms that might evade accountability for violations caused, including in cooperation with different political or land tenure regimes.

A third implication is the necessity to rethink the potential for shifts by agribusiness in the current era, in which possibilities for adaptations by investors and companies, and thus more redirected land use and control change processes, are enhanced. Agribusiness-related capital is nowadays simultaneously more disperse – as publicly listed companies or private investment funds can easily have investors from all over the world – and more concentrated, as the sector has consolidated in the last decades in several oligopolies, which gives more flexibility and more options for coordination in response to political contestations (Friedmann Citation1992; Borras et al. Citation2020). Certainly, some actors have much more flexibility to adapt than others. Financial funds can more easily shift their investments across sectors and spaces and international traders can source from and sell to several locations across the globe. Transnational investors, in particular, are able to calculate and compare what they translate as ‘risks’ and ‘rewards’ on a global scale (Li Citation2014, 598–9) and can attempt to mitigate risks by diversifying their portfolios. On the other hand, actors that are more territorialized might have less maneuvering space. Furthermore, the shorthand ‘agribusiness capital’ represents a complex mosaic with asymmetries of power and conflicting interests – not only due to competition between companies, but also in the intersection with geopolitical conflicts.

Still, some general points can be made about the current enhanced capacity for adaptations and coordination by agribusiness capital. Recently, the agri-food system has become even more flexible, given the tendency for a few key commodities produced worldwide, such as soy, maize, and palm oil, to be used as relatively interchangeable sources for multiple uses, leading to web-like commodity complexes (Borras et al. Citation2016). Financialization brings up a new dimension of flexibility to agribusiness, by allowing quicker moves of capital and new mechanisms to bypass legislation through multiple shell companies hiding actual funds, which ultimately allowed the foreign pension funds to invest in Matopiba and bypass restrictions on foreign ownership of land (Spadotto et al. Citation2020). The formation of transnational land investment webs (Borras et al. Citation2020) implies extra risks for redirected shifts from capital reacting to social and environmental contestations that are restricted to a certain sector, region or issue. Finally, these corporations and sectors also benefit from new possibilities for gathering and processing information on potential frontiers, made possible by new technologies that create novel forms of legibility of territories and by the establishment of consultancies, real estate firms and brokers facilitating land and agribusiness deals across the globe.

4. Conclusions

While these changes might point to a dire picture, they do not, in any way, imply that struggles over natural resources – whether from perspectives of agrarian justice, environmental justice or the convergence of both – are always accommodated and subdued into convenient adaptations by capital. This study attempts to contribute to the ongoing reflections of activists and scholars on how to apprehend and confront the interconnected contradictions across sectors, spaces, and social and environmental contradictions. There has been important academic work on the multiple webs of influences between different commodities and sectors (Borras et al. Citation2016; Novo et al. Citation2010), and social movements and partner organizations have made significant efforts to increase transnational collaborations. As discussed, the struggle against ProSavana in Mozambique has been aided by the collaboration between peasant movements from Brazil and Mozambique and by lessons from previous frontier-making processes in Brazil (Aguiar and Pacheco Citation2016), and the Campaign in the Defense of the Cerrado has among its goals to continue exchanges between affected people of the Brazilian Cerrado and Mozambique.

This paper represents an attempt at looking at three key dimensions that can make or break frontiers and which contain spaces for adaptations mediated by political decisions: spatial adjustments, change in political-administrative regimes and changes in forms of land appropriation. These dimensions serve as a lens to compare and connect different potential frontiers, and to understand how capital's shifts in spaces and strategies interact with multiple, emerging political contradictions. The analysis of these three dimensions under a broader consideration of redirected land use and control change also provides a possible point of dialogue between critical agrarian studies, sustainability studies and analyses of state-society relations. Finally, this perspective, in dialogue with other established frameworks, could potentially also help to refine the visualization of which calculated political risks land grabbers are engaging in and thus facilitate the anticipation and prevention of socially and environmentally destructive forms of redirected land use and control change.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all those who gave valuable insights to earlier versions of this paper and with whom I had fruitful discussions on this research, especially: Alberto Alonso-Fradejas, Amod Shah, Anna Galeb, Daniela Andrade, Fábio Pitta, Jun Borras, Julien Gerber, Lorena Izá Pereira (also for composing two maps here used), Melek Mutioglu, Mindi Schneider and Valeria Recalde, and my deepest thanks to Yukari Sekine also for her careful comments on this latest manuscript. I am also very grateful for the helpful comments and suggestions of the anonymous reviewers. Finally, I am deeply appreciative of the people who agreed to participate in the research and who helped me in fieldwork, in particular to members of the Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado and to the organizers of the 2017 Fact-Finding Mission in Matopiba: the Social Network for Justice and Human Rights in Brazil (Rede Social), FIAN and the Pastoral Land Comission (CPT).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniela Calmon

Daniela Calmon is currently a PhD candidate at the International Institute of Social Studies (Erasmus University Rotterdam) in The Netherlands and a visiting doctoral researcher at the Center for High Amazon Studies (NAEA) at the Federal University of Pará in Brazil. Her research interests include the multi-scale political dynamics of frontier-making, intersections of land and climate change politics and the strategies of transnational corporations operating in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado.

Notes

1 Brazil is covered by six large environmental biomes, or ecoregions with broadly common environmental characteristics: Amazon, Cerrado, Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Pampa and Pantanal (IBGE Citationn.d.). While the Cerrado is broadly understood as a savannah ecoregion, and the adjacent Amazon is known for its tropical forests, there are multiple transition zones between them and ecological subdivisions within them (such as the Zona dos Cocais in Maranhão and Piauí), complexifying any clear division. Moreover, the administrative division of the ‘Legal Amazon’, covered by the Superintendence of Development of the Amazon, differs from the Amazon biome and partly covers states of Matopiba as well as Mato Grosso (Complementary Law 124/Citation2007).

2 Previous names given by researchers and companies to the frontier have been Bamapito, Mapitoba, Mapito (excluding Bahia) and variations of proposals as North, Mid-North and Center-North Corridor.

3 Mato Grosso state alone concentrated 26,7% of the 114.075.300 tons of soy produced in total in Brazil and 27,5% of the 33.909.400 hectares occupied by soy in Brazil in the crop season of 2016/2017 (CONAB Citation2017, 116).

4 The expression grilagem has historically been used in Brazil to denote the illegal forgery of documents to claim land tenure, typically of public lands (Sauer and Borras Citation2016, 12–13). However, it has also been used to identify more sophisticated forms of irregular appropriation of land covered by the veneer of legality, such as in the expression of ‘legalized grilagem’ (Oliveira Citation2016, 146) or with recent legislation that in effect legalizes grilagem after it has been committed (Sauer and Leite Citation2017).

5 Translated by author from Portuguese.

6 Santa Filomena and Bom Jesus each surpass 5000 km², while Brejo and Buriti are each smaller than 1500 km² (IBGE Citation2017).

7 This conjuncture is under change, with a 2017 agreement of stockholder restructuring (Coelho, Milanez, and Wanderley Citation2017).

8 For cerrado areas within the Legal Amazon (an administrative division which covers a significant portion of Maranhão and the entirety of Tocantins, within Matopiba), the requirement is of 35%. For forest areas in the Legal Amazon, the requirement is much more stringent, requiring 80% of legal reserve (Law 12.651/Citation2012).

9 Such as the approximation between some environmental organizations and agribusiness corporations (Bunge Citation2018).

References

- Aguiar, D., and M. E. Pacheco, eds. 2016. The South-South Cooperation of the Peoples of Brazil and Mozambique. Rio de Janeiro: FASE.

- Aguiar, D., and S. Porto. 2018. “A Expansão da Fronteira Agrícola e Logística nos Cerrados e Savanas: Agroestratégias e Resistências no Brasil e em Moçambique.” Paper presented at the 6th BICAS International Conference, Brasília, November 12–14.

- Almeida, A. W. B. de. 2008. Terra de quilombo, terras indígenas, ‘babaçuais livre’, ‘castanhais do povo’, faixinais e fundos de pasto: terras tradicionalmente ocupadas. Manaus: PGSCA–UFAM.

- Alonso-Fradejas, A. 2015. “Anything but a Story Foretold: Multiple Politics of Resistance to the Agrarian Extractivist Project in Guatemala.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (3): 489–515.

- Alves, V. E. L. 2009. “O mercado de terras nos cerrados piauienses: modernização e exclusão.” Revista Agrária 10 (11): 73–98.

- Barros, B. 2016. “Matopiba está perto do limite, diz estudo.” Valor Econômico 21 November.

- Borras, S., and J. Franco. 2012. “Global Land Grabbing and Trajectories of Agrarian Change: A Preliminary Analysis.” Journal of Agrarian Change 12 (1): 34–59.

- Borras, S., J. C. Franco, S. Gómez, C. Kay, and M. Spoor. 2012. “Land Grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (3-4): 845–872.

- Borras, S. M., J. Franco, S. R. Isakson, K. Levidow, and P. Vervest. 2016. “The Rise of Flex Crops and Commodities: Implications for Research.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (1): 93–115.

- Borras Jr., S. M., J. Liu, Z. Hu, H. Li, C. Wang, Y. Xu, J. C. Franco, and J. Ye. 2018. “Land Control and Crop Booms Inside China: Implications for How We Think About the Global Land Rush.” Globalizations 15 (1): 134–151.

- Borras, S. M., E. N. Mills, P. Seufert, S. Backes, D. Fyfe, R. Herre, and L. Michéle. 2020. “Transnational Land Investment Web: Land Grabs, TNCs, and the Challenge of Global Governance.” Globalizations 17 (4): 608–628.

- Bunge. 2018. Bunge, Santander and TNC Offer Soy Farmers Long-Term Loans August 29. https://www.bunge.com/news/bunge-santander-brasil-and-tnc-offer-soy-farmers-long-term-loans-expand-production-without.

- Câmara de Comércio e Indústria Japonesa do Brasil. 2011. Seminário internacional debateu sobre investimentos no agronegócio em Moçambique. 25 April – Notícias da Câmara.

- Carneiro, M. S. 2008. “A expansão e os impactos da soja no Maranhão.” In Agricultura familiar da soja na região Sul e o monocultivo no Maranhão: duas faces do cultivo da soja no Brasil, edited by S. Schlesinger et al., 75–147. Rio de Janeiro: FASE.

- Carneiro Filho, A., and K. Costa. 2016. A expansão da soja no Cerrado: Caminhos para a ocupação territorial, uso do solo e produção sustentável. São Paulo: Agroicone, INPUT.

- Casado, L., and E. Londoño. 2019. “Under Brazil’s Far Right Leader, Amazon Protections Slashed and Forests Fall.” The New York Times, July 28.

- Coelho, T. P., B. Milanez, and L. J. Wanderley. 2017. O Novo Acordo dos Acionistas da Vale, MAM, May 15. https://mamnacional.org.br/2017/05/15/o-novo-acordo-dos-acionistas-da-vale/.

- Complementary Law 124 of 3 of January of 2007. Institui, na forma do art. 43 da Constituição Federal, a Superintendência do Desenvolvimento da Amazônia (…) BRASIL –Casa Civil.

- CONAB. 2003. Previsão e Acompanhamento da Safra 2002/2003. http://www.conab.gov.br/OlalaCMS/uploads/arquivos/c009db051e6748a6a4f54524fa70ec55.pdf.

- CONAB. 2017. Acompanhamento da Safra Brasileira – Grãos. http://www.conab.gov.br/OlalaCMS/uploads/arquivos/17_09_12_10_14_36_boletim_graos_setembro_2017.pdf.

- Cotula, L. 2013. The Great Africa Land Grab? Agricultural Investments and the Global Food System. New York: Zed Books.

- Decree 8447 of 6 of May of 2015. Dispõe sobre o Plano de Desenvolvimento Agropecuário do MATOPIBA e criação de seu Comitê Gestor. BRASIL - Casa Civil.

- Delgado, G. C. 2010. “A questão agrária e o agronegócio no Brasil.” In Combatendo a desigualdade social: o MST e a reforma agrária no Brasil, edited by M. Carter, 81–112. São Paulo: UNESP.

- Domingues, M., and C. Bermann. 2012. “O arco de desflorestamento da Amazônia: da pecuária à soja.” Ambiente & Sociedade 15 (2): 1–22.

- Dou, Y., R. F. B. da Silva, H. Yang, and J. Liu. 2018. “Spillover Effect Offsets the Conservation Effort in the Amazon.” Journal of Geographical Sciences 28 (11): 1715–1732.

- Edelman, M., and A. León. 2013. “Cycles of Land Grabbing in Central America: An Argument for History and a Case Study in the Bajo Aguán, Honduras.” Third World Quarterly 34 (9): 1697–1722.

- Edelman, M., C. Oya, and S. M. Borras Jr. 2013. “Global Land Grabs: Historical Processes, Theoretical and Methodological Implications and Current Trajectories.” Third World Quarterly 34 (9): 1517–1531.

- Embrapa. 2015. Matopiba Geoweb. Accessed 10 November 2017.

- Fairhead, J., M. Leach, and I. Scoones. 2012. “Green Grabbing: A New Appropriation of Nature?” Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (2): 237–261.

- Fernandes, B. M. 2010. “Formação e Territorialização do MST no Brasil.” In Combatendo a desigualdade social: o MST e a reforma agrária no Brasil, edited by M. Carter, 161–197. São Paulo: UNESP.

- FIAN International, Rede Social de Justiça e Direitos Humanos and CPT. 2018. The Human and Environmental Cost of Land Business – The Case of MATOPIBA, Brazil. Heidelberg: FIAN International.

- Franco, J., and S. M. Borras. 2019. “Grey Areas in Green Grabbing: Subtle and Indirect Interconnections Between Climate Change Politics and Land Grabs and their Implications for Research.” Land Use Policy 84: 192–199.

- Friedmann, H. 1992. “Distance and Durability: Shaky Foundations of the World Food Economy.” Third World Quarterly 13 (2): 371–383.

- Gaspar, R. B. 2013. O eldorado dos gaúchos: deslocamento de agricultores do Sul do País e seu estabelecimento no Leste Maranhense. São Luís: EDUFMA.

- Gill, S., and D. Law. 1989. “Global Hegemony and the Structural Power of Capital.” International Studies Quarterly 33 (4): 475–499.

- GRAIN and Rede Social de Justiça e Direitos Humanos. 2018. Harvard’s Billion-Dollar Farmland Fiasco. Report – September 2018.

- Greenpeace. 2014. Moratória da soja na Amazônia. Da beira de um desastre a uma solução em desenvolvimento. Accessed 2 January 2017.

- Harvey, D. 2003. The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, D. 2014. Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism. London: Profile Books.

- Hershaw, E., and S. Sauer. 2017. “The Evolving Face of Agribusiness Investment along Brazil’s New Frontier: Institutional Investors, Recent Political Moves, and the Financialization of Matopiba.” Paper presented at the 5th BICAS International Conference, Moscow, 13–16 October.