ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the relationship between cyclical labour migration and agrarian transition in the uplands of Nepal, Ethiopia and Kenya. It shows that while migration decision-making is linked to expanding capitalist markets, it is mediated by local cultural, political and ecological changes. In turn, cyclical migration goes on to shape the trajectory of change within agriculture. The dual dependence on both migrant income and agriculture within these upland communities often translates into an intensifying work burden on the land, and rising profits for capitalism. However, on some occasions this income can support increased productivity and accumulation within agriculture – although this depends on both the agro-ecological context and the local agrarian structure.

1. Introduction

Labour migration is a defining societal issue of the twenty-first century. A substantial 258 million people live outside their country of birth worldwide as of 2017 – a figure which has risen by 69% since 1990. There are also about 740 million internal migrants (FAO Citation2012), a group whose importance is often overlooked (Castaldo, Deshingkar, and Mckay Citation2012). Upland areas have long been important regions of out-migration, given the fragile ecological resource base and structural dependence on lowland economies (Grau and Aide Citation2007; Sugden, Seddon, and Raut Citation2018). Contrary to commonly held presumptions however, the rise in migration from and within the Global South does not necessarily lead to the ‘abandonment’ of agriculture, even in resource constrained upland landscapes (Greiner and Sakdapolrak Citation2013; Jokisch Citation2002). Instead, households are increasingly moving towards a dual livelihood, where peasant farming is combined with temporary labour in the capitalist sector of cities or overseas, often to provide households access to cash in the face of rising living costs and agrarian stress, while the land provides households with their food needs (Warner and Afifi Citation2014; Schoch, Steimann, and Thieme Citation2010; Murton Citation1999). The importance of this dual livelihood strategy was brought to the fore during the COVID19 crisis, whereby migrant labourers, who had lost their employment were forced to return to their villages or home countries en mass, often under conditions of extreme distress (Dandekar and Ghai Citation2020). As these workers move between migrant labour and agriculture periodically, they are hereafter termed ‘cyclical’ migrants.

This paper engages with the relationship between cyclical migration and agricultural livelihoods in the uplands of central Kenya, northern Ethiopia and eastern Nepal. We move beyond simple questions of migration ‘drivers’ or ‘impacts’ to situate labour mobility within a larger context of agrarian transition – the process through which the peasantry shifts from one mode of production to another. We assert that cyclical migration, which is increasingly central to livelihoods in the Global South, is emblematic of a distorted pattern of agrarian transition as capitalism expands into peripheral locales and articulates with peasant economic formations. We also explore the nuances of migration decision-making under diverse political-economic and ecological contexts, before seeking to understand the stresses brought about by migration on labour management and gender relations. Finally, we question whether the increased cash flows from wage labour into mountain regions with otherwise limited off farm wage earning options, can be mobilised within upland agriculture to expand or intensify production, reducing longer term dependence on migration – and what this means for rural differentiation.

2. Agrarian transition, capitalist expansion and cyclical labour migration

Research on the relationship between migration and agriculture in sending communities is an emerging field. This includes research on migration decision-making, including its role as an adaptation strategy to ecological and agrarian stress (Tacoli Citation2009; Nielsen and Reenberg Citation2010), or the cultural imperatives to migrate (Sharma Citation2013). Research has also looked at how migration affects cropping patterns and resource allocation on the farm (Chen, Pandey, and Ding Citation2013; Piras et al. Citation2018), the acquisition of agricultural knowledge (Sugden and Punch Citation2016), and the management of land (Murton Citation1999). Out-migration of men has also been shown to improve women farmers’ financial empowerment, yet also add to their work burden (Adhikari and Hobley Citation2011; Hadi Citation2001).

While this research also seeks to understand the two-way connections between out-migration and economic and environmental change, it moves beyond an analysis of migration decision making or migration ‘impacts’ in isolation. Instead, it seeks to understand how both fit within the larger process of agrarian transition and the expansion of capitalism into diverse, ecologically fragile mountain regions.

Agrarian Studies has for decades sought to understand the diverse paths of transition from a non-capitalist peasant economy towards capitalism in the Global South, particularly in the wake of post 1980s neoliberal restructuring (Lerche, Shah, and Harriss-White Citation2013; Akram-Lodhi and Kay Citation2010; Bernstein Citation1996). Upland regions themselves are not isolated from this change, in spite of geographical remoteness (Dunaway Citation1996). The ecological, climatic and geological ‘niche’ provided by upland geography means they are prime sites for capitalist accumulation. While accumulation can take place through displacement and proletarianisation of the peasantry, through for example, hydropower development (Barney Citation2009), mineral extraction (Perreault Citation2013) or rubber plantations (Kenney-Lazar Citation2012), this represents an extreme mechanism through which capitalism dissolves peasant based agrarian formations.

There is broad recognition in agrarian studies that the peasantry need not be ‘dispossessed’ of their land to facilitate capitalist accumulation (Hart Citation2002). In many upland regions where the peasantry remains intact, it is cyclical labour migration which has emerged as a lucrative source of surplus value for capitalism in lowland cities and overseas (Sugden, Seddon, and Raut Citation2018). The reason this form of migration is profitable for capitalism is because the migrants are often paid a wage that only covers their immediate subsistence needs. The costs of what Marx ([Citation1933] Citation2008, 36) termed labour reproduction, including the costs of bringing up the labourer, their ‘retirement’, and support for non-productive household members, are provided by the peasant economy (Meillassoux Citation1981). This capacity for cyclical migrant workers to generate substantial profits through covering the reproduction costs of labour has been demonstrated in the context of West African guest worker migration to post-war Europe (Meillassoux Citation1981), migration in Apartheid South Africa (Wolpe Citation1982), and migration to Indian cities from the Eastern Gangetic Plains (Sugden Citation2019) and the Adivasi belt of central India (Shah and Lerche Citation2020; Singh Citation2007). Rural-urban migration in China has also led to lowering the cost of urban labour (Zhan and Scully Citation2018; Alexander and Chan Citation2004).

These studies document a skewed pattern of agrarian transition whereby segments of the peasantry depend on both agriculture and migrant labour, yet cannot improve their economic position through either. This livelihood pattern however follows multiple trajectories. The first divergence is with regards to the decision-making of farmers to migrate. While cyclical migration from peripheral parts of the global economy generates substantial profit, the processes encouraging rural people to enter the labour force are not reducible to a simplistic logic of capitalist accumulation in receiving regions alongside underdevelopment in sending regions.Footnote1 Using case studies from upland communities in Nepal, Ethiopia and Kenya, the paper will explore how migration decision-making and the character of migration is mediated by local political-economic, cultural policy and ecological contexts. The second divergent trajectory of change is with regards to how migration reshapes livelihoods in rural communities. The paper will go on to explore how migration and the injection of cash into peripheral upland communities shapes patterns of accumulation and differentiation by both class, gender and ethnicity – and how these are mediated by the contours of local the geography, ecology and political economy.

3. Methods and study sites

At the time of writing the authors were part of the same research programme, and were based in Nepal, Ethiopia and Kenya respectively. The Nepal study (2015–2016) was part of an analysis of agrarian change and migration. The valley was chosen as it was representative of Nepal’s middle hills and its cultural and agroecological diversity. The authors of this paper later decided to conduct comparative research in Kenya and Ethiopia in 2017–2018. These latter two field sites were selected out of several where the team had done past research and specific villages were chosen following discussions with local government agencies and development institutions. We selected communities with high levels of out-migration, while trying to capture a range of agroecological domains within each site.

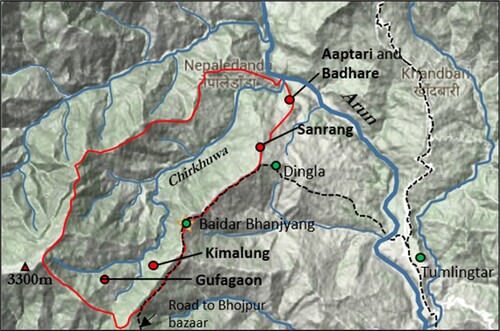

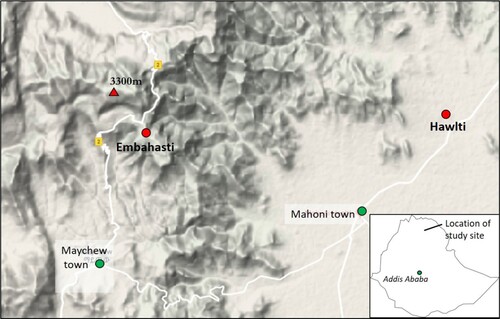

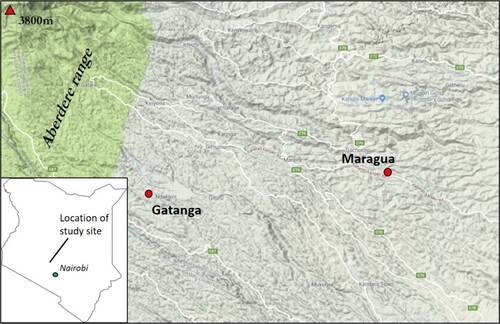

The Nepal site is situated in the densely populated Chirhkhuwa valley in the eastern hills (see ). Three clusters were selected for the analysis. The villages of Kimalung and Gufagaon are in the upper altitude temperate zone (above 1700 m). Most land is rainfed and is suitable for subsistence millet, maize and potato production. Sanrang in the middle altitude zone (between 600 and 1700 m), and Aaptari/Bhadare, in the lower altitudinal zone (below 600 m), have a subtropical climate suitable for intensive cultivation of paddy.

In Ethiopia, both field sites are situated in the southern part of Tigray in the northern highlands (see ). As with the Nepal site, there is considerable agroecological diversity. The first community is Embahasti kebeleFootnote2, which is situated high above Maichew, the main town of the Endamehoni district, at a temperate altitude of 3000 m. Rainfall is high for the region, and the cropping system is dominated by wheat, barley and vegetables such as carrots and cabbage. Hawlti kebele by contrast lies in the in adjacent Raya Azebo district in the lower yet drier Raya valley at around 1700 m, which is dominated by mostly subsistence oriented sorghum and teff cultivation.

In Kenya, the research was focussed in Muranga district in the central highlands in the Upper Tana River basin (see ), in the Kikuyu heartland. The study sites include two densely populated sub-counties, both of which are home to dispersed settlements which span the multiple watersheds spreading down from the Aberdare mountains. Gatanga is a higher altitude site between 2000 and 2200 m, while Muragua is lower altitude between 1600 and 1700 m. The region is important for cash crops such as coffee, tea and commercial vegetables, alongside subsistence maize production.

In total, 365 interviews took place across seven communities in the three countries (see ). The interviews included a quantitative section collecting data on agricultural production, livelihoods and migration, and a qualitative section to assess perceptions and experiences of out-migration in a changing agricultural context. In Nepal, due to the small size of the communities, most households were interviewed, while in Kenya and Ethiopia, households with a current migrant family member were selected. These respondents were introduced to the team by gatekeepers from local NGOs, farmer groups, or local government and in the process we endeavoured to capture a range of wealth groups, as seen in the subsequent analysis. The sample was not selected using a systematic random method from the community population which creates a limitation for the data in Ethiopia and Kenya, as it does not give a cross section of the community. However, as our research was focussed on exploring the process of migration and how it shapes agrarian livelihoods, by focusing on households known to have migrants, we were able to ensure we had sufficient qualitative and quantitative data for reliable analysis. Secondary data from the local government was acquired in Ethiopia to give indications as to the levels of migration. Our paper also builds upon a significant body of knowledge from earlier work by the research team across the region (Nijbroek and Wangui Citation2018; Sugden, Seddon, and Raut Citation2018; Birnholz et al. CitationForthcoming).

Table 1. Interviews carried out in each community.

4. Particulars of migration in the study sites

4.1. The Chirkhuwa valley, Nepal

4.1.1. Agricultural change and ecological context

The Chirkhuwa valley was historically home to the indigenous Rai, who were shifting cultivators on the valley slopes. Following the eighteenth century Gorkhali conquest, Hindu castes brought sedentary paddy cultivation methods and claimed the fertile, once forested, valley land in the lower agro-ecological zone. Meanwhile, the abolition of tribal communal land rights or kipat, and creation of individual property rights to land, disenfranchised many indigenous cultivators who resided on the valley slopes (Gaenszle Citation2000; Sugden, Seddon, and Raut Citation2018). Over the centuries, other janajati or indigenous groups settled in the upper altitude zone, including the Sherpa who settled near the watershed, where they carried out transhumance, and the Tamang who settled below the Sherpa on the steeper, more marginal land.

These ethnic settlement patterns which are visible across eastern Nepal (Gaenszle Citation2000) created a unique altitudinal geography of inequality. Furthermore, with population growth and the state abolition of the kipat system, agriculture was sedentary by the early twentieth century and feudal class divisions also emerged, particularly in the fertile middle and lower agro-ecological zoneFootnote3 where a class of wealthier land owners emerged.

4.1.2. Agrarian structure today

Inequalities in the agrarian structure persist today. In the upper altitude zone, most farms are small and include only rainfed bari land. Ninety-two per cent of farmers have their own plots (see ) and inequality within the two communities is only moderate, with no notable ‘large farmer’ class. In spite of this, the land is marginal, with a short growing season.Footnote4

Table 2. Composition of sample by land ownership and agroecological cluster, Nepal.

In the middle altitude zone around Sanrang, the land is fertile and allows multiple harvests, yet with a history of landlordism, inequality is more distinct. Five per cent of the sample are pure tenants, yet a substantial 24% of the sample are part-tenants who sharecrop some of their land.Footnote5 About 43.10% of farmers are small owner cultivators with less than 0.5 ha of khet land or 1 ha of rainfed land, while 25.86% are larger farmers with more than 1 ha of bari or 0.5 ha of khet land. There is significant inequality in the productive khet land, suitable for paddy cultivation, which has been long sought after by more powerful socio-economic groups. Larger farmers, who form just a quarter of the sample, own 70% of this land. Most of this group are upper caste Brahmin and Chettris, who own 0.78 ha of khet on average, compared to just 0.44 ha for the numerically dominant Rai.

Table 3. Composition of sample by land ownership status by kebele, Ethiopia.

Inequality is even higher in the lower altitude zone on the valley floor, where most the land is khet. Here agriculture is dominated by landlord-tenant relations. About 11.29% of the sample are landless tenants, with 38.71 as part tenants for whom just under two-thirds of their land is rented. Despite the fertile land and access to irrigation, sharecropping means that paddy produced by tenants is often sufficient for just four to six months of the year. While there are several prosperous owner cultivators, most landlords who are renting-out are Brahmins from Sanrang and are absentees and are not captured in the sample, with many living in lowland towns.

4.1.3. Migration

The Eastern Nepal Himalaya has long seen significant labour migration, initially to work on colonial era tea plantations in Assam and Darjeeling (Caplan Citation1970), and in more recent via cyclical movement to Indian cities. However the 1990s saw new migration opportunities with rising demand for labour from Gulf Cooperation Council governments after the first Gulf war. These states sought a low-cost, temporary workforce, who were culturally separated from citizens and non-aligned to the political fissures of the Arab World (Chalcraft Citation2010; Hanieh Citation2010). The peasantry from countries such as Nepal offered these states an ideal labour force. Their labour power could be reproduced through the agrarian system at home, keeping wages down, while short-term contracts would ensure it remains cyclical and they retain these links to their home communities (Sugden Citation2019).

Government policy in Nepal since the 1990s has actively facilitated this migration through various acts and bilateral treaties with states in the Gulf, and other Asian countries such as Malaysia (Sijapati and Limbu Citation2012). For the government, migration could be considered a ‘safety valve’ for youth, particularly when faced with a stagnant industrial sector and civil unrest (Wickramasekara Citation2016). The number of labour permits issued by the governments for overseas work increased dramatically from 3605 in 1993/1994 to 453,543 in 2012/2013 (Sharma et al. Citation2014).

In the agroecologicaly fragile upper altitude villages of Kimalung and Gufagaon, 77% of sampled households had migrant family members at the time of research, compared to 60% in Sanrang in the middle altitude zone and 55% in Aaptari and Bhadare in the lower altitude zone. Across all the villages, 92% of migrants are overseas, working primarily in construction and the service sector in the Gulf countries and factories and plantations in Malaysia, with the remainder in Indian cities and Nepal, some of whom migrate seasonally. All migrants recorded were male, and as a consequence, just over a third of households are female headed.

4.2. Southern Tigray, Ethiopian highlands

4.2.1. Agricultural change

The Southern Tigray region has an ancient history of sedentary agriculture and was known to be productive and fertile in the past. Since the nineteenth century, a combination of climatic, demographic and political-economic stresses resulted in widespread environmental degradation (Young Citation2006; Kebbede and Jacob Citation1988). During the years of Haile Selassie (1930–1974), agriculture in Ethiopia was feudal with some parallels to Nepal. Land in Tigray was held under a form of communal ownership known as rist where it belonged to a kinship group. Peasants had to pay dues to the imperial regime or religious institutions, and there was a notable landed nobility (Kebbede and Jacob Citation1988; Young Citation2006). Land fragmentation due to the division of plots within families alongside a steady rise in population was a persisting challenge, and over half of holdings in Tigray were less than 0.5 ha (Kebbede and Jacob Citation1988). There were few incentives for tenants or small farmers to invest on the land when between a third and half of the produce was appropriated through rents, taxes and dues. During this period, the landed nobility converted communal land into private holdings, resulting in rising landlessness (Bennet Citation1983).

After the overthrow of the emperor in 1974, land reforms were carried out under the Derg regime. While these abolished feudal agrarian relations and led to the nationalisation of land (Ghose Citation1985), inequalities persisted, and some argued that land reforms and redistribution favoured larger farmers and the old elite (Bennet Citation1983) or were not fully implemented in the North due to the ongoing conflict with the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front.

Decades of land scarcity and inequality throughout the twentieth century contributed to a cycle of environmental decline across the northern highlands, which peaked in the 1980s. The severe food insecurity had driven farmers onto even steeper slopes, worsening the loss of top soil and reducing soil moisture retention (Kebbede and Jacob Citation1988). This environmental history was brought up by respondents in the study sites who also noted that what limited forest and vegetation cover was left was cleared for fodder and fuelwood. This made agriculture far more vulnerable to drought. Land degradation, combined with the civil war, state neglect, and persisting inequality and land scarcity, culminated in the devastating 1984 famine (Kebbede and Jacob Citation1988).

There were significant agricultural improvements since the 1990s following the change in government, with the state initiating large scale soil and water conservation works. Labour was mobilised from villages to build terraces, check dams and bunds. In later years these were continued via donor funded food for work programmes (Bewket and Sterk Citation2002). In the study sites, land restoration efforts included bench terracing, afforestation (mostly eucalyptus), and gabions construction on fragile slopes, and construction of ponds.

4.2.2. Agrarian structure today

Unlike in Nepal, the state is the ultimate owner of land in Ethiopia, and plots are allocated by the kebele. However, most farmers operate as de facto independent peasants with control of their own production process and surplus. While plots are small and fragmented in Tigray, as is the case across Ethiopia (Paul and Wa Gĩthĩnji Citation2018), the holding sizes are sufficiently divergent to create a moderate inequality in land distribution – although these don’t align to ethnic-caste divisions as they do in Nepal given the relative cultural homogeneity of the study villages (see ). Seventeen per cent of interviewed farmers across both villages own more than 0.5 ha. The largest amongst this group with more than 1 ha of land represents just 13% of the sample, yet owns 53% of the land. In both communities, while land is not on its own a measure of wealth as it has some bearing on the family size and historical allocations to households, larger farmers generally have higher output and display a greater investment in assets. For example 30.5% of owner cultivators with over 0.5 ha who we interviewed have access to irrigation as compared to 11% of small owner cultivators. Seven households are landless, all of whom work as tenants, yet another 45% are part tenants, with some of the latter being more prosperous farmers expanding their holdings through the lease market.

4.2.3. Migration

While migration overseas was banned until the 1980s, it rose rapidly after the 1990s (Kefale and Mohammed Citation2016), when the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs issued the Private Employment Agency Proclamation to manage employment overseas (Fernandez Citation2017), and following the removal of the requirements for exit visas for Ethiopians in 2004 (Kefale and Mohammed Citation2016).

Ethiopia was one of several countries (along with Nepal) from where migrant labour was sought by the Gulf states. Yet while labour agreements with Nepal were primarily for unskilled male manual labour, for Ethiopia, the focus was on meeting the demand for female domestic workers – particularly during the 2000s when welfare concerns spurred some Asian countries to restrict female domestic worker migration to the region (Kefale and Mohammed Citation2016). The number of permits for female domestic work in Saudi Arabia for example, the largest destination for Ethiopian labour migrants, rose from just 2478 in July 2009 to 160,000 by 2012 (Fernandez Citation2017). Unlike in Nepal there are far fewer bilateral labour treaties to sustain legal migration channels, and the supply and demand for work far exceeds the number of permits issued (Kefale and Mohammed Citation2016). As a result, the government estimates that 60–70% of the estimated 300,000–350,000 Ethiopians in the Gulf states are irregular migrants without legal papers (Fernandez Citation2017). Internal labour migration is also widespread.

According to official kebele level data, there were 55 migrants from Embahasti and 179 migrants from Hawlti.Footnote6 These figures are likely to be significantly higher given that so much mobility is informal. In Embahasti, all migration was within Ethiopia, with 71% being long-term (several years at a time) and the remainder being seasonal. Just over a third of migrants in our sample were women, and with males still making up the majority. In the drought prone Hawlti village in the lower altitude Raya valley, only 14% of the migration was internal, and often involved seasonal movement to Humera to work on sesame plantations. This region has however seen a large rise in undocumented migration to Saudi Arabia, representing 86% of the migration recorded in the sample The fees paid to agents are high and many migrants face deception, exploitative conditions and deportation. Male migrants, who make up just over half of the sample, mostly work in Saudi Arabia as cattle keepers. Women migrants, who make up a substantial 48% of the sample, mostly also go to Saudi Arabia, usually for domestic work.

4.3. Central Kenyan highlands

4.3.1. Agricultural change

The agrarian system of the predominantly Kikuyu central highlands, was shaped under the British colonial regime. There was widespread land alienation, with certain lands being set aside for white farmers and other lands being allocated as ‘African reserves’ for the Kikuyu. The latter lands were often neglected in colonial agricultural policy (Kanyinga Citation2009). In the late colonial period, land tenure reform was carried out. It sought to replace uncertain customary tenure with individual land titles (Kanyinga Citation2009), but also to consolidate scattered plots, expand cash crop production and encourage investment through registered titles by farmers as security for loans (Haugerud Citation1989). It was hoped this would lead to the emergence of a powerful class of capitalist farmers from within the peasantry who would buy out the plots of smaller producers. However, land purchases were often for speculation rather than investment and loans were often diverted into consumption (Haugerud Citation1989).

As in Ethiopia, fragmentation within families resulted in dwindling plot sizes, a process which continues to this day. While landlessness increased, there were insufficient opportunities in agriculture or industry to absorb the growing surplus labour pool (Haugerud Citation1989). This ‘failed’ agrarian transition towards capitalism created the backdrop for the migration patterns to the urban capitalist sector of the present. There was some redistribution of formerly white owned land after Kenyan independence. Land made available was insufficient to distribute to the large number of landless households, and already well-off farmers who could afford the required deposit could secure larger plots. Later schemes favoured larger commercial farms, thus worsening land inequality (Kanyinga Citation2009).

Land inequalities have persisted today, although with a diversity of new crops, improved inputs such as hybrid seeds and rising manure use, cropping intensity has increased and most land is cultivated throughout the year. This intensification however has not been without challenges. Like in the Ethiopian case study, there is a long history of land degradation in the upper Tana basin due to decades of intensive slope cultivation (Kizito et al. Citation2013). Farmers complained of falling soil fertility due to fertiliser overuse (likely causing acidification), mono-cropping, and soil erosion on the deforested steeper slopes. There have been some efforts to control the decline and many farmers turned to terracing, planting of Napier grass strips (32.82 ha of land cultivated in study site) and afforestation of trees such as banana (4.23 ha of land). Nevertheless, the levels of restoration are not as advanced as in Ethiopia, and most households cannot subsist from the land alone.

4.3.2. Agrarian structure today

In Kenya, like Nepal, farmers can own their land and there is notable pre-existing differentiation in the peasantry, although there are no ‘feudal’ agrarian relations. Across both communities, only two interviewed households were landless, 24% were small owner cultivators with less than 0.5 ha, with a further 23% being small owner cultivators who also rented land as tenants (see ). Fifty-two per cent of the sample with more than 0.5 ha own 79% of the land, although only five households own more than 2 ha. While this points to moderate concentration of assets, we did not encounter a distinctive ‘large farmer’ class with disproportionate control over land like in Nepal.

Table 4. Composition of sample by land ownership status by sub-county, Kenya.

4.3.3. Migration

There is a relatively long history of migration in the Central Highlands. As also documented in West Africa (Meillassoux Citation1981), the colonial administration used several mechanisms to mobilise a labour force for capitalism, such as taxation and neglect of agriculture. There was high migration of Kikuyu within the highlands to work on white-owned farms and plantations (Kanyinga Citation2009).

Out-migration continued throughout the postcolonial period in the Central Highlands (Greiner and Sakdapolrak Citation2013). As with Ethiopia, the Gulf governments have sought labour from Kenya, and the government estimates that around 100,000 of its citizens are working there as domestic workers and other forms of low paid and manual labour (Malit Jr. and Al Youha Citation2016). While migration to the UEA was reported in the study site, overseas migration was significantly lower than in Nepal and Ethiopia. The proximity to major centres such as Nairobi and Nakuru meant that cyclical labour to work in the urban capitalist sector was predominant. Most migrants were reported to engage in ‘casual labour’ particularly in construction. Other jobs included drivers and factory workers. Most households, noted that around 10 years ago there would be one migrant in each household while it is now common for two or more family members to work in urban centres. From sampled households, two-thirds of migrants were seasonal. Female migration is common, like in Ethiopia, although there was a tendency for women to return to the community after marriage, particularly if their husband had inherited land, with the community being a favoured domain to raise children.

Local labour is limited to casual jobs such as construction, or semi-skilled trades such as masonry and carpentry. Some household members also reported local jobs as boda boda (motorcycle taxi) drivers.

5. Capitalist expansion, monetisation and climate stress: understanding migration decision making

The decision to migrate to enter the capitalist labour force is a complex process. When asked an open-ended question on the decision for family members to migrate, most respondents across all three countries noted financial insecurity and the difficulty meeting immediate food needs from the land. Nevertheless, dialogues connected this to a range of secondary stresses including climatic change and political-economic shifts. Therefore, while one cannot isolate a specific ‘proximate’ process which encourages family members to migrate, the decision to enter the labour force takes place against a backdrop of rising agrarian and livelihood stress.

A narrative that came up repeatedly in interviews, across different socio-economic groups, and in all three country sites, was the rising demand for cash to purchase an increasing availability of products in local shops. This is driven by an unprecedented expansion of capitalist markets over the last 20 years into what were once relatively isolated regions. Structural adjustment programmes in Nepal and Kenya in the 1980s, and Ethiopia in the 1990s (Demissie Citation2008; Rono Citation2002; Khanal, Rajkarnikar, and Acharya Citation2005), have supported an expansion of markets, alongside a surge in imported commodities, growing export orientation of agriculture and privatisation of public services. Within this context, the cash needs of households have spiralled, and respondents repeatedly noted that migration has filled the gap.

In all three countries, farmers complained of a rising cost of fertiliser – particularly in Kenya where more input intensive commercial cropping systems are common. Of particular concern though was a rise in the cost of living. Respondents in all three countries have also been affected by rising costs of education and medical care, which has taken place in the context of privatisation. The rising price of food was also a concern, in line with global trends. In Hawlti of Ethiopia for instance, it was noted how the cost of teff, the primary staple in Ethiopia, has risen almost 10-fold in a decade, and the price of an ox had risen from 3500 birr ($110) to around 24,000 birr ($755) during the same period. This inevitably affects younger households who have separated from their parents but have not inherited titles for land – the group making up most labour migrants.

The cost of living has also been pushed up with the enhanced access to imported commodities. These changes were particularly dramatic in Nepal as a surge in foreign-aid-funded road building over the last decade has increased the availability of consumer goods, at the expense of local cottage industry, in turn dissolving old exchange systems whereby local people would purchase goods using grain. In all three countries however, the increased availability of imported commodities has fostered a culture of consumerism. It was amongst youth, the primary group entering the capitalist labour force, where this was most apparent. Interviews reported strong peer pressure for young people to spend money on high quality or fashionable clothes. One family in Ethiopia recalled how their son had friends from a wealthy family and part of his decision to migrate was connected to a desire to ‘follow’ their lifestyle, including buying expensive clothes, with similar aspirations being recalled by three other households with migrants. With Nepal, it was remarked how young people observe urban lifestyles on TV, and aspire to purchase goods such as liquor, soft drinks, sweets, noodles and clothes now easily available in local markets, in line with a perceived ‘modern’ lifestyle (see also Liechty Citation2003). In all sites, paying for mobile data was also a significant albeit recent ‘expense’.

The connection between changed expenditure patterns and migration operates in both directions, and migration itself perpetuates particular aspirations of a modern lifestyle intertwined with consumer culture, as also noted by de Haas (Citation2014) regarding Morocco. Respondents in Nepal and Ethiopia noted how migrants return with expensive goods, encouraging other young people to follow. Associated with this are posts on social media offering a selective vision of migrants’ lives – often in opulent surroundings, even if these are far from the lived realities of workers in the Middle East. In Hwalti, a village leader noted how remittances from Saudi Arabia were themselves invested in TVs and other imported electronic goods, resulting in a desire amongst youth to make similar investments, further contributing to the incentives to migrate. The desire to invest in ‘modern’ goods as part of the migration experience (from Nepal) has been analysed by Sharma (Citation2013).

In Nepal, changed consumer behaviour extends to food habits. In the non-rice growing villages of Kimalung and Gufagaon, households have reduced the consumption of traditional crops from their diet such as phapar (buckwheat), maize, and potatoes and now purchase rice imported from the lowlands as the primary staple. Rice consumption has long been associated with social status since it was introduced two centuries ago by upper caste cultivators from the west (Gaenszle Citation2000). Now that it is easily available in the local market, there is strong cultural pressure to consume it – despite the rising costs of grain. Remittances from male migrants are one of the primary mechanisms through which to meet the cost of rice purchases.

It was clear from the interviews that migration was increasingly a necessity if households were to continue their livelihood trajectory and maintain an acceptable living standard. Nevertheless, there has also been a cultural shift, which has gone alongside economic change and monetisation whereby young people aspired to migrate and leave agriculture sector as an end in itself. As Carling (Citation2002) notes regarding Cape Verde, the economic, social and political context, including a place based (rather than individual) perception of poverty, facilitates the emergence of particular cultural narratives through which young people aspire to migrate.

In Kenya, a lack of jobs was mentioned by nearly all respondents when asked about migration decision making. However, when digging deeper, it was absence of local jobs outside of agriculture which was the key issue. In Ethiopia, despite the significant improvements in agricultural productivity, just wanting to ‘experience’ city life emerged in 7% of interviews as a factor behind migration decision making. Several older respondents also noted a strong peer pressure amongst youth or the need to ‘follow’ their friends. In Nepal, this cultural pressure to migrate has been framed by Sharma (Citation2013) as a ‘rite of passage’. While these aspirations do not neatly align with material circumstances, they are arguably connected to the larger process of capitalist infiltration, whereby aspirations for an urban lifestyle went side by side with changing patterns of consumption and a rising demand for cash.

It has been established how rising demand for cash in the wake of expanding markets and cultural change amongst youth has contributed to migration decision making. This drive to leave farming, however, also needs to be explored in the context of additional stresses facing the peasantry. A first consideration is the land ownership structure. The inter-household inequalities in access to land appeared to have a limited role in shaping the decisions for family members to migrate – with rates of migration remaining high for households across different land ownership groups. For households in the Nepal sample who own less than 0.5 ha of khet paddy land (or less than 1 ha of bari dry land), 65% have a current migrant, which is comparable to the 59% for those with more than 0.5 ha. The average number of migrants per household is actually higher for the larger farmers at 1.33, versus 1.17 for the smaller farmers. In the case of Ethiopia, the number of migrants per household is 1.7 for land poor households with less than 0.5 ha of land, and it is only marginally different, at 1.6, for their better off counterparts. For Kenya this was 2.11 and 2.02, respectively.

This echoes de Haas’ (Citation2014) framework which suggests increased wealth can actually increase both the aspirations and capabilities to migrate. Rising education and living standards may increase households’ ability to bear the costs and risks associated with migration, while also enhancing desires for a better lifestyle.

Access to land within the family though, is a contributory factor in the decision for family members to migrate in Kenya and Ethiopia though, when one considers the rising intergenerational inequalities in access to the means of production. Against a backdrop of land fragmentation, young people are less likely to inherit land from their parents at an age when they become independent, or are receiving smaller plots. It has been almost three decades since land was last redistributed, and population had risen considerably since then. Lack of access to land for youth was raised as a factor in the decision to migrate by 6% of respondents in Ethiopia, and 11% in Kenya. In Endamehoni woreda, where Embahasti kebele is located, the land restoration programme had reached out to youth and provided them plots, usually through producer groups, and thus far 1400 have been engaged in agriculture and agricultural enterprise programmes. However, this is just a small proportion of the estimated 12,000 youth in the woreda.

A second set of stresses facing the peasantry are associated with climate change. While it was rarely raised directly as a ‘reason’ for migration, as shown elsewhere (Black et al. Citation2011), it was invariably recalled as one of several causes for poor agricultural performance, which draws farmers towards external labour markets. In Nepal for example, when asked about changes in agriculture over the last decade, climate invariably cropped up as a cause of stress, particularly in the upper part of the valley in the heavily migration dependent villages of Kimalung or Gufagaon, where agriculture is rainfed and the cropping season is shorter. Farmers there blamed late rainfall for a twofold decline in the potato yield and a drop in maize production, while noting that warmer temperatures had increased pest outbreaks.

In Ethiopia, there were also significant perceptions of climate stress, despite the improvements in land management. Southern Tigray is highly vulnerable to climatic extremes, particularly drought. Analysis from the region has shown an increase in summer kiremt rain and drop in the Spring belg rains over three decades, but has also pointed to differences between rainfall data and farmer perceptions (Abrha and Simhadri Citation2015). In the lower and drier Hawlti there was a strong perception that the precipitation had declined in recent years with more frequent drought. The precipitation was just 350–650 mm per year as opposed to 2000–2500 mm in Embahasti (data from local woreda office), and 93% of respondents noted that it had shown a declining trend, limiting the effectiveness of many of the government extension and soil and water conservation initiatives. In the absence of irrigation, households complained of persisting food insecurity. Just 11.60% of the cultivated area had been irrigated over the last year, compared to 22.33% in Embahasti in the uplands. Regardless of whether the perceived decline in rainfall matched with actual trends, perceptions are important when understanding migration decisions.

In higher rainfall Embahasti, changing climate was not considered a cause of livelihood stress or a contributory factor in migration decision making, and combined with land restoration, several respondents felt that that the outlook for agriculture in terms of productivity was positive. The production of market oriented vegetables by 51% of households there was itself helped by the wetter climate, unlike in Hawlti, where the cropping system is dominated by teff and sorghum for subsistence, and only one household had produced vegetables.

In Kenya, perceptions of increased climate stress were evident amongst nearly all respondents. Farmers complained of reduced rainfall, and an increase in the incidence of prolonged drought, to the point that some crops such as French beans could no longer be planted. Farmers also complained of cold spells which can be damaging for tomatoes. Again, this was not framed as a reason for labour migration, although combined with the persisting challenge of land degradation, it was one among several biophysical pressures contributing to falling agricultural production and the need for outside sources of cash.

6. Migration wages and the agrarian structure

In Nepal, monthly unskilled labour wages for migrants are low by the standards of the receiving countries which can vary from 800 Riyal in Qatar ($220) to MYR1100 in Malaysia ($270). These wages are comparable to off-farm wage work in NepalFootnote7, except that working abroad is favoured as it provides a regular income for a 2–3-year period. Out of those who had received remittances in the last year, the average annual income was $1931, or $160 per month. In Hawlti, Ethiopia, where undocumented migration to Saudi Arabia was widespread, $1164 on average was sent back per year. In Embahasti, where most people were migrating internally, they could earn around $100 a month, but as work was often not regular, average annual money sent home was only $450 per year.

Interviews across the sites suggested that migrant income could not meet the family’s subsistence needs without the additional income or food from the farm. As noted above, the continued ties cyclical migrants hold to peasant agriculture at home itself supports the perpetuation of low wages – and this represents a classic articulation of modes of production which is highly profitable for capitalism. The inability to support one’s family was even more critical for Kenyan internal migrants. They also had to contend with the spiralling cost of living in Nairobi and other cities. Wages were typically KSH 10,000 a month ($100) for jobs such as a security guard. One parent reported that their son actually calls them to borrow cash during periods of hardship. Only $138 on average was reportedly sent home over the year – although this was likely an underestimate.Footnote8

While wages are low, a further challenge for migrants from Nepal and Ethiopia is the share of migrant income appropriated by intermediaries. It was normal for Nepali migrants to the Gulf to pay around $1500 to ‘manpower agents’ in local towns, to connect them with jobs overseas. In Ethiopia also, labour migrants to Saudi Arabia make payments of between $300 and $1000 to smugglers and middlemen.Footnote9 These intermediary costs mean a substantial 89% of households in the Nepal sample had taken high interest migration loans, usually from private money lenders, including 98% of tenant farmers – the poorest producers. During the first few years after migration households face a considerable debt burden.

Similarly, 40% of migrants from Hawlti in Ethiopia had taken loans to fund their migration to Saudi Arabia (usually from relatives, friends or other migrants), with the remainder selling off high value assets such as livestock or utilising family savings – pushing the household into further financial insecurity. These loans sometimes contribute to accumulated debts from the past, and combined with the sale of assets, they can contribute to the same economic pressures which encourage families to look outside for work in the first place. Even after departure, there was no guarantee that migration would lead to a regular in flow of cash. Undocumented migrants to Saudi Arabia faced chains of extortion along the way during the risky passage, along with the risk of deportation with no earnings. Even in Nepal where migration is through official channels, stories of deception by employers or agents and associated financial losses were widespread.

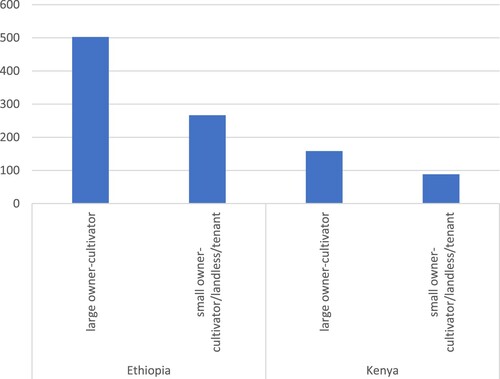

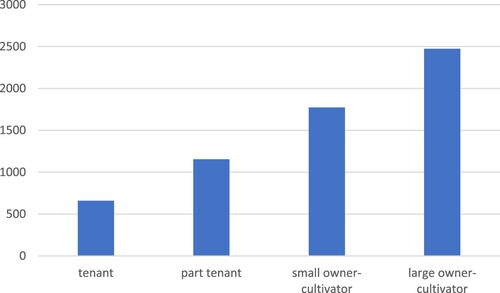

Importantly, while one’s pre-existing position in the agrarian structure plays a limited role in shaping the decision to migrate, it does play a role in shaping the financial outcomes of migration for the household, as also noted by de Haas’ (Citation2009) Morocco study. In Ethiopia and Kenya, farmers were asked about the increase in annual income after migration (see ).Footnote10 Accepting these are only rough estimates, they did point to stark differences according to wealth. In Kenya for example, smaller owner-cultivators/landless households reported no increase in income, while larger owner-cultivators estimated an average increase of $225. Similarly, in Ethiopia, the estimated increase was just $55 for smaller owner-cultivators/tenants as opposed to $336 for larger owner-cultivators. This is particularly acute in Nepal, where inequalities are most acute. Tenant farmers at the base of the agrarian structure have earned on average $273 from migrants in the last year as compared to those classified as larger owner cultivators, who were earning on average $728 (see ).

Figure 4. Average income sent by migrants in last year by land ownership status * in Kenya and Ethiopia (US$).

Note: * Large owner-cultivators have >0.5ha of land, small owner-cultivators have <0.5ha of land.

Figure 5. Average income sent by migrants in the last year by land ownership status * in Nepal (US$).

Note: * Large owner-cultivators have >0.5 ha of khet (paddy) land or >1 ha of bari (dry) land. Small owner-cultivators have <0.5ha of khet land or <1ha of bari land.

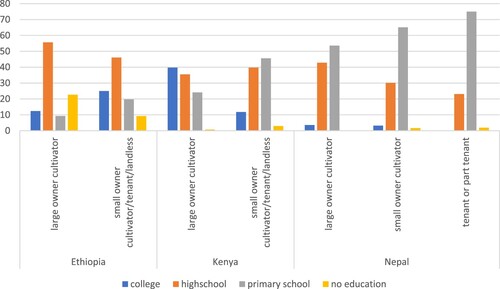

These differences are partially connected with educational attainment (see ). In Kenya, 40% of migrants from larger owner-cultivator households had college level education as opposed to just 11% of smaller farmers. These figures are 56% and 46% respectively for Ethiopia. In Nepal, college level education was restricted to a handful of large owner-cultivator households, although 42% of this group have a high school education as compared to 31% from small owner-cultivator households and 26% from tenants. Better-educated migrants from Nepal to the Gulf or Malaysia can partake in skilled work, often in the service sector, and thus earn more than the base wages for unskilled labour set by bilateral agreements. Other factors affecting wages may include better social networks or access to capital for investment in enterprises at place of destination. In the case of Nepal, it was reported that indebted families would often pay remittances directly to the private moneylenders. This may lead to lower reported cash inflows for poorer households.

7. Migration and divergent trajectories of agrarian transition

7.1. Changing role of women, the work burden and implications for agriculture

The articulation between peasant agrarian formations and capitalism through migration is influencing the trajectory of agrarian change, including labour management, and patterns of differentiation. The peasant economy has been argued to subsidise wages in the urban sector through covering the cost of labour reproduction – yet for this to take place, those who stay behind inevitably need to increase their labour contributions on the land. This is particularly challenging given the challenges previously explained. Labour shortages and rising workloads in agriculture following migration have been shown in numerous past studies (Adhikari and Hobley Citation2011; Ajani and Igbokwe Citation2011; Hadi Citation2001; Sugden et al. Citation2016). In all three sites, the only migrants recorded in the survey as having limited or no involvement in agricultural work before migration were younger family members who migrated after finishing school.Footnote11 The remainder of migrants had a key role to play on the farm before they left. In Nepal for example, male migrants were previously engaged in tasks such as land preparation, repairs to terraces, making animal shelters, cutting bamboo, and transporting millet or maize to the mill. Now these tasks fall to women. This was by far one of the biggest issues raised by female respondents when asked how migration had affected their wellbeing.

In the Ethiopia and Kenya sites, female migration was also widespread, yet the labour burden of out-migration still disproportionately affects women who stay home, particularly older women. In Kenya for example, respondents were asked in the survey who picked up the labour burden after a migrant had left. A third reported this being passed on to other female household members such as the wife, sister or mother in law, and just under half reported it being ‘shared’ between remaining men and women. In Hwalti of Ethiopia, where levels of female and male migration are equal, it was often the older generation who took on the work burden on the land – creating additional hardships in the case of poor health.

Although women and older people disproportionately experience labour stress due to out-migration, this does appear to disproportionately affect households at the base of the agrarian structure, in particular, those who have less land and lower levels of remittances. Women and the elderly from better off households in all three sites reported hiring in of labour to compensate for absent family members. In Ethiopia for example, one household had two sons working in the town, one was a trader another a carpenter, with reasonable income. Workers from outside were hired to take on farm work to support the parents.

7.2. Migrant income, agricultural investment and differentiation

Migration induced labour shortages place considerable pressures on agrarian livelihoods already enduring the stresses of climatic change and monetisation. However, an important question is whether the injection of cash into the household economy by migrants can support accumulation and productivity improvements within agriculture. While this appears highly unlikely for the poorer households experiencing the lowest remittance flows, the variability in the levels of exploitation that migrants experience, and the higher levels of migrant earnings for better off farmers, means this may be a possibility for selected households. This section thus considers whether migration is emerging as a driver of differentiation within the peasantry.

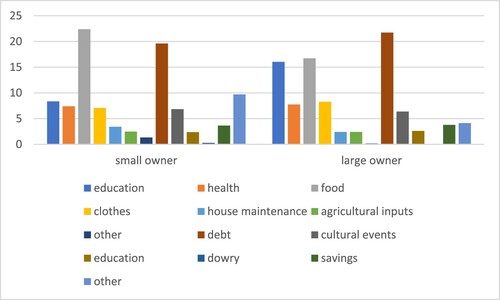

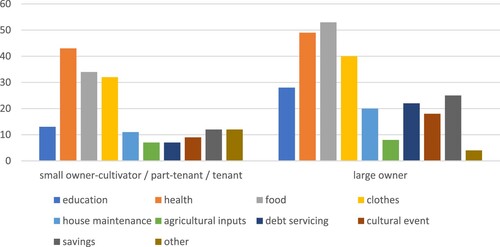

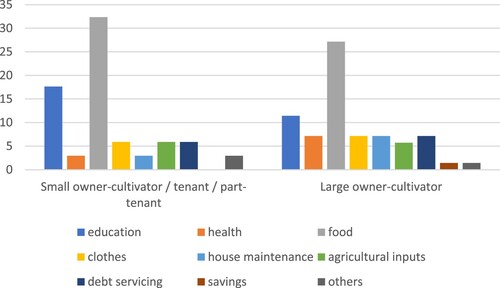

The data suggests that the majority of respondents in all three sites, regardless of land ownership, spent what was sent by migrant family members primarily on basic subsistence, as shown in numerous rural studies (Sijapati et al. Citation2017; Tsujita and Oda Citation2014; Adhikari and Hobley Citation2011). In the Nepal sites, farmers were asked to estimate the proportion of remittances spent on different items. Food is by far the biggest expenditure by both better-off and poorer farmers (see ), with negligible use of remittances on the farm (3%). In Ethiopia and Kenya, the survey asked households to list how money sent home had been spent. Again, farm inputs or other agricultural costs (e.g. equipment hire) were very limited compared to subsistence items (see and ). In all three sites debt servicing appears significant, and in Nepal it absorbs a similar proportion of migrant income to what is spent on food.

Figure 8. Percentage of farmers allocating remittances to different spending categories in Ethiopia by land ownership status.

Figure 9. Percentage of farmers allocating remittances to different spending categories in Kenya by land ownership status

While day-to-day investment of migrant income into agriculture may be limited, could accumulated cash be instead channelled by farmers into longer-term investments to improve the land, mechanise production to offset labour shortages, shift to new cropping systems, or even make land purchases? This is significant for understanding how migration shapes the trajectory of differentiation in agriculture, as it could allow a strata of the peasantry who are already better off (and whose migrant family members often earn higher wages) to further improve their financial position or emerge as an ‘accumulating’ class.

The utilisation of migrant income for long-term investments in the land received attention in Tiffen, Mortimore, and Gichuki’s (Citation1994) seminal study in Machakos, Kenya, which recorded investment of cash from migrant family members in terracing and other improvements. Similarly, de Haas (Citation2006), referring to Morocco, notes that remittances from Europe were invested in tube wells and pump sets to intensify production. Significantly though, in a critique of Tiffen, Mortimore, and Gichuki’s (Citation1994) Kenyan study, Murton (Citation1999), in a follow-up study in the same district, highlighted the class pattern to investments of migrant income. Food secure larger farmers were more likely to use cash to improve the productivity of the land, while their poorer counterparts instead use it to make up for shortfalls in food production.

For this study, levels of investment in Ethiopia and Kenya were found to be low across the board. In Kenya, just 11% of respondents had invested money sent by migrants in high value assets such as machinery, while only one respondent had bought land, and 13% had invested in cattle. In Ethiopia, 10% of households invested in livestock on their return, and while farmers cannot ‘buy’ land in the village, 5% had bought a plot in the town for non-agricultural purposes. Although there are large, capital intensive commercial farms near Hawlti, the expensive deep tubewells which these farms depend on are out of reach for even the wealthiest local farmer, and all these enterprises belong to private investors from urban areas, with some linked to international agri-business.

Given that so few households have invested migrant income in land or agricultural improvements, it is difficult to assess the role played by pre-existing wealth in these two sites. The low levels of investment suggest the practice is not widespread – particularly in Ethiopia where one cannot buy agricultural land. However, as an alternative to purchasing land or productivity improving assets, some households do make shorter term investments to increase the cropped area through taking land on lease after a family member had migrated. Here, wealth does appear to have an influence (see ). In Kenya in particular, 11% of larger farmers with over 0.5 ha of land have increased the cultivated area, while only 3% of smaller farmers have done so, with 18% of this latter group having actually decreased the cultivable area. The latter had rented their own land out due to their inability to cope with the labour shortages and costs, unlike their richer counterparts who can bear the expense. This points to some moderate differentiation within agriculture associated with labour shortages.

Table 5. Percentage of households who had increased or decreased the cultivable area after migration of family member by land ownership status.

It is only in Nepal where there is evidence of more substantial agricultural investment using money sent by migrants, as well as an emerging pattern of inequality. Investments are usually in land itself (given that productivity-improving investments such as machinery are limited in the rugged topography) and are driven by an effort to cultivate more lucrative crops. However, the capacity of households to invest and the opportunities they offer are aligned heavily to existing inequalities rooted in both the altitudinal settlement patterns on the one hand, and the distribution of land on the other.

In the upper altitude zone, which is home to historically marginalised ethnic communities, and where plots are rainfed, only 3% of households had bought land using remittances, and farmers consistently spoke of a lack of interest in investing on the farm and an intensifying dependence on remittances. Around 5% of households had actually sold land since the migration of a family member, and 5% had left land fallow. A further 8% have rented out their land, and only 3 households (8%) had reported improvements to their irrigation facilities in what is a largely a rainfed area. These findings from Nepal actually echo Nyangena’s (Citation2008) finding’s from a more ecologically fragile region of Kenya, where it was noted that increased flows of cash from migrants is associated with a reduced investment in land and soil conservation, possibly because livelihoods becomes more oriented towards off farm labour, with less time or interest to improve the land.

However, in the middle and lower agro-ecological zones, which have larger fields, a longer growing season, and greater access to water, there is strong evidence of migrant earnings being ploughed back into agriculture through land purchases, combined with investments to switch land over for agro-forestry, particularly rudrakshya cultivation – a ceremonial bead produced from the seeds of the tree elaeocarpus ganitrus, for which there is surging demand in India and China. Rudrakshya can only be grown in this lower altitude zone, which is also conducive for other commercial crops such as fruit and vegetables. A substantial 38% of households in Sanrang and 23% in Aaptari/Bhadare reported that they had purchased land using remittances or the money saved from migration – frequently with a view to expand cultivation of commercial crops. Several households had also invested in irrigation.Footnote12

However, in spite of this, there is a clear class dimension to these opportunities. Out of the 17.9 ha of land bought by the sample using migration income in the lower and middle altitudinal zone, 30% was purchased by larger owner cultivators (as per the categories in ), in spite of them forming just 18% of the sample. A further 45% of land bought was from small owner cultivators. However, only 13% of purchases were from tenants or part-tenants, in spite of them representing 49% of the sample. This is in part linked to the much lower levels of remittances for these two groups (see ).

While some land appears to have been bought from households who have relocated to the lowlands or urban areas, it appears that some has also been purchased from other local farmers in distress, pointing to some differentiation. Within the sample, 3.15 ha of land had been sold following migration of a family member, often due to migration induced debts. All sales were amongst small owner cultivators and tenants, with none amongst the larger farmer category. No land has been sold by the absentee landlords also, who appear to retain control over their holdings.

Furthermore, the ability for households to translate their investments in these new crops into a substantial profit is again linked to one’s agrarian class position. In Aaptari and Bhadare where rudrakshya agroforestry is most lucrative, large owner cultivators have earned a substantial Rs 147,142 ($1306) from rudrakshya in the last year. For small owner cultivators, it is only Rs 81,073 ($723), and for part-tenants it is Rs 49,130 ($438). For pure tenants it is only Rs 35,875, ($318) – less than the Rs 54,285 ($497) they earned on average from remittances. For households facing the rent burden, not only do they have a reduced capacity to purchase land, sharecropping acts as a considerable disincentive to shift towards cash crops. Rudrakshya cultivation involves turning land away from grain staples, which are required for food security, and it is several years before the trees yield an income. Landlords themselves had also begun asking for a share of the income from trees on their land planted by tenants, again undermining any potential economic benefits.

Wealth related barriers to investment also intersect with unequal gender relations, particularly regarding the distribution of remittances within the household. For women-headed households in Nepal whose husbands are overseas, only 53% receive money from their husbands directly and decide how it is used, while for the remaining households in-laws take control of the cash. Women’s control over migrant’s cash is even lower at just 23% for male-headed households, who make up two-thirds of the sample. Similarly, in Kenya where migration by both males and females is present, the money is sent to the wife or mother in 75% of women-headed households, versus 25% in male-headed households, with male family members such as fathers-in-law or brothers controlling cash in the remaining cases.

While women have benefitted from greater agricultural decision making, the challenges in easily accessing cash from migrants may create further disincentives for investment, particularly for those from land poor or tenant households. In the case of Nepal, while women are increasingly managing the land and leading the shift towards new cash crops in the lower altitudinal zone, not all women have access to funds as and when is required, or have the ability to independently make decisions with regard to land purchases.

In the case of Kenya, certain crops such as tea are managed almost entirely by men, and this remains the case even after male out-migration. While women still do the bulk of the labour, migrant male family members would manage this land from afar, investing to hire additional labour, and receiving cash directly into their bank accounts from the tea companies. While women did have control over vegetable and dairy production, they lack access to capital to independently invest in more lucrative cash crops such as tea, which would allow them to control the income.

7.3. Leaving the migrant labour force and investment by returnees

It thus far appears that the degree to which migrant earnings can be ploughed back into agriculture is limited to certain strata of the peasantry and varies according to the agro-ecological context. Amongst better off land-owning farmers, one observes limited expansion of the cultivated area in Ethiopia and Kenya, and actual purchases of land using remittances in Nepal, although only in more productive agro-ecological domains. However, with the evidence of accumulation outlined above – can this money be mobilised by some of these households to encourage return migration and even a long-term ‘break’ in their dependence on migrant income? This is particularly pertinent when one considers the additional ‘social remittances’ such as new skills acquired by migrants.

In interviews in all three sites we encountered migrants who had returned on a long-term basis. However, this was more often due to distress rather than as an ‘opportunity’. For example, out of the six households in Kenya with returnees, three came back due to a failure to find work. As one respondent noted, her son worked for five years as a carpenter in Nairobi. The cost of living was high, and if he had a bad day he could go hungry. He eventually gave up and returned to the farm where there was at least a regular source of food. Another son continues to work in Naivasha, but he hardly has sufficient money to send back after meeting his immediate needs. Another household reported migrants returning due to poor health and another was linked to ethnic conflict. In Ethiopia several migrants had returned due to deportation. These cases of individuals who returned under duress certainly did not represent a ‘break’ in the structures which drive migration due to a stronger livelihood, and many who had come back had considered migrating again.

There were however isolated stories from Nepal of better-off households returning on a long-term basis with a view to invest in agriculture. Again though – this was strongly linked to the emerging patterns of differentiation. In the middle altitude villages of Sanrang 15% of households had long-term returnees, while it was a substantial 35% in the most fertile villages of Aaptari and Bhadare. It was the income generating opportunities in rudrakhsya agroforestry, however, which provided an incentive for migrants from better off families with larger plots of fertile land at home to return. One male migrant had recently returned from the Gulf with Rs400,000 ($3750) in savings which he had used to buy a plot of land for a rudrakshya plantation, and we encountered several similar cases. Disillusionment with the wages and hardship overseas were consistently noted as important in shaping the decision of these migrants to return, suggesting that the exploitative articulation of modes of production can be broken for some households with sufficient land at home.

Further research could show whether this cessation of migration in these contexts is permanent – particularly following recent disruption such as the COVID19 pandemic. What is clear though is that these opportunities for migrants to return and invest in rudrakshya cultivation are rooted in wealth and the agro-ecological context. In the ecologically fragile upper altitude zones, there was negligible return migration. Only three households had returned, out of which one planned to go again. The weaker agricultural resource base means alternative sources of cash are more limited and the articulation with the capitalist sector through migration remains entrenched. The same applies for tenants in the lower agricultural zones.

In Kenya, some young people did return to agriculture, given the high potential for cash crops and lucrative new crops such as macadamia, but access to land was considered a prerequisite to success, and thus represented a barrier for many young people. There were isolated stories of young people returning and purchasing or renting in land, such as a former labourer who had worked on a highway project, and had returned to purchase a plot, using the profits from milk production to expand the enterprise. However, risks are high and there was a perception that some youth only return to farming as a last resort.

7.4. The role of the state

While pre-existing wealth and agro-ecological context is important, the state can create a backdrop which is more conducive for migrants to invest. The state-led land restoration in Embahasti of Ethiopia, combined with targeted efforts to provide youth access to land, appears to have encouraged a few young people to return to farming or at least postpone the decision to enter the migrant labour force. These initiatives have expanded the cultivable area – with land given to youth collectively for vegetable and fodder production, while supporting individuals in livestock raising and small enterprises. One returnee in Embahasti noted how he used to work as a daily labourer in Maichew town three years ago, and used to earn 50–60 ETB ($1.5–1.9) per day. Now he is engaged in agroforestry and poultry production at home. Some youth in Embahasti had used leased land to invest in vegetable production, but this was restricted to those with capital and who could bear the risk.

While efforts to provide youth access to land are admirable, a critical difference from sites in Kenya and Nepal is that the Ethiopian government maintains control over the ownership and allocation of land. The persistence of this socialist model allows the state the discretion to distribute vacant or newly restored plots to youth, a phenomena which would be difficult to achieve in Nepal or Kenya where ultimate property rights lie with the individual – and in the Nepal case, the persistence of absentee landlords creates additional constraints.

Furthermore, the encouraging efforts by the state in the Ethiopian site to encourage youth investment possibly represent an isolated case, and across the three countries, there is no coherent policy seeking to address the links between migration and agrarian change. Policy in Ethiopia (Dessalegn, Nicol, and Debevec Citation2020) and Nepal (Sijapati and Limbu Citation2012) is largely oriented to facilitate the migration process or control irregular movement. In Kenya, a national policy on migration was in its draft in 2018, and has yet to be finalised as per the available information (International Organization for Migration Citation2018).

8. Conclusions

This article has sought to understand what cyclical migration means for the trajectory of agrarian transition at a time of unprecedented economic, social and environmental change in three upland sites in Kenya, Ethiopia and Nepal. The process of labour migration has been shown to be closely connected to a distorted pattern of transition in these upland regions, whereby capitalist production remains limited on or off the farm locally, yet the peasantry participates in wage labour in the capitalist sector outside, either domestically or overseas.

While the decision-making process to migrate takes place within the broader context of uneven development and neoliberal restructuring, at an individual level it remains complex. Rising costs of living associated with expanding capitalist markets and cultural shifts in consumption have combined with changing aspirations for youth, climate stress, and intergenerational inequalities in access to land.

While farming alone is insufficient to support large segments of the peasantry in these three ecologically fragile domains, neither are wages from workers in urban areas and overseas sufficient – particularly when one considers the reproductive costs of labour. Peasant participation in the migrant labour force arguably generates significant profits for capitalism, and this translates into an intensified work burden for those who stay behind, particularly women, and further agrarian stress. Importantly though, not all migrants are subject to the same levels of exploitation, and with different types of engagement in the capitalist sector, there are varying levels of cash flowing back to the community – differences rooted in pre-existing inequalities. We also address the question of whether the increased flows of cash for some of these households can be mobilised within upland agriculture to expand or intensify production, shaping the trajectory of agrarian transition – paving the way for differentiation and new patterns of inequality. It is here one observes divergent trajectories of change.

It is in Nepal where differentiation is more notable. This site experiences the greatest inequalities, including persisting landlord-tenant relations as well as an altitudinal geography of inequality rooted in historical relations between the state and indigenous communities. A new pattern of differentiation is emerging in this site. There is an emerging class of land-owning peasants in the lower valleys, investing their remittances in land for lucrative cash crop production. The inflow of cash can also push these better off farmers’ livelihoods beyond a threshold whereby the articulation between low productivity farming and low wage labour is undermined – with many returning to invest on the land. The experiences of these farmers stand in contrast to a second, increasingly distressed segment of the peasantry, which is made up of two subgroups. The first are the tenants in the lower valley with limited scope to expand their holdings or increase profitability due to the rent burden and lower migrant wages. The second are the Tamang and Sherpa families on the more marginal upper altitude land where unfavourable ecological conditions mean opportunities for investment and accumulation are low.

In the Ethiopia and Kenya sites on the other hand, the pattern of change is mixed. Some better off farmers have been able to expand the cultivable area, mobilising income from migrants to invest in cash crops. However, this has taken place only on a low level and has not broken households, dependence on migrant wages. While there are a few returnees, this often takes place under duress. For many, the limited access to land for youth presents a barrier for agricultural investment amongst the younger generation who dominate the migration economy.

It has also been observed that in all three country sites, the opportunities for investment in agriculture appear to be particularly constrained for women. Not only do they disproportionately bear the burden of labour shortages, accessing remittance cash to push back into agriculture is not a given, with in-laws frequently controlling how money is used.

It is important to emphasise that cyclical migration is emblematic of the distorted development of capitalism within peripheral locales in the Global South. The majority of the peasantry in our upland study sites were engaged in extremely low wage, cyclical migration, the wages of which fail to cover families' minimum subsistence needs. Given that opportunities for agricultural investment are segmented by wealth, the chances of in-flows of migrant cash supporting widespread accumulation across socio-economic groups is negligible.

Nevertheless, in the short term, do some government policies have the potential to support agrarian livelihoods for potential migrants or returnees? Answering this question would require further research on successful initiatives from elsewhere, but the paper does highlight the need for targeted packages of support for households affected by migration, including returnees. This includes identifying strata within the peasantry who are not able to divert earnings back into agriculture, and identifying the barriers rooted in access to land and labour, as well as agro-ecological limitations. With the case of land restoration for youth in Embahasti, one observes an example of a local government targeting the groups most likely to migrate, addressing the primary constraint (low ownership of land amongst youth) and increasing opportunities on the farm. While such initiatives will not reduce migration, they may remove some of the ‘distress’ associated with the decision to join the capitalist labour force outside. Importantly, the three countries studied in this article would benefit from more direct engagement between researchers and policymakers to ensure a better understanding of the complex two-way relationship between migration and agrarian transition, and the interventions and policies which may support migrant youth, returnees and their families at a time of unprecedented economic and agro-ecological stress.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful for the support and hospitality provided by the community in the study communities in Bhojpur, Nepal, the Upper Tana basin in Kenya, and in Maichew and Raya Azebo in Ethiopia. Invaluable field support was provided by Tesfu Arbha and Haimanot Woldegebriel in Ethiopia, Bimala Dhimal, Manita Raut and Sujeet Karn in Nepal, and Veronicah Thuo, Joyce Ndathy, Simon Njoroge and Nicholas Kuria in Kenya. The research was funded by the CGIAR programme for Water, Land and Ecosystems.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fraser Sugden

Fraser Sugden is geographer with over 15 years experience conducting research on the political economy of agrarian change in South and East Asia. He is presently a Senior Lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Birmingham, and at the time of conducting the research for this article he was a Senior Researcher at the International Water Management Institute and the country representative for IWMI Nepal, where he remains a visiting fellow.

Likimyelesh Nigussie

Likimyelesh Nigussie is a Research Officer at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Liza Debevec