ABSTRACT

This article explores whether mechanisation affects patterns of accumulation and differentiation in Zimbabwe's post land reform where policy consistently disadvantages smallholders. Is the latest mechanisation wave any different? The article considers dynamics of tractor access and accumulation trajectories across and within land use types in Mvurwi area. Larger, richer and well-connected farmers draw on patronage networks to access tractors and accumulate further. Some small to medium-scale farmers generate surpluses and invest in tractors or pay for services. Thus, accumulation from above and below feeds social differentiation. Tractor access remains constrained yet mechanisation is only part of the wider post-2000 story.

1. Introduction

Zimbabwe's Fast-Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) implemented from 2000 reconfigured the country's agrarian political economy. The emerging agrarian structure is now dominated by smallholders (Scoones et al. Citation2010; Moyo Citation2011; Shonhe and Mtapuri Citation2020), articulating with both medium and large-scale farms. The changed agricultural economy has in turn generated new patterns of capital accumulation and social differentiation (Scoones et al. Citation2010; Moyo et al. Citation2014; Scoones et al. Citation2018). This new agrarian political economy is shaping debates about the role of agricultural mechanisation in Zimbabwe (Moyo Citation2011; Shonhe Citation2019a), which is unfolding against the backdrop of a strong push for mechanisation across the African continent driven by governments and development agencies (African Development Bank Citation2016; FAO and AUC Citation2018).

In policies supporting agricultural mechanisation in Africa, the state has historically been biased towards tractors (Binswanger Citation1986; Houmy et al. Citation2013). Recently, South-South cooperation, involving China, Brazil, India and other ‘rising powers’, has played a part in driving tractor-focused mechanisation (Cabral et al. Citation2016; Cabral et al. Citation2013), including in Zimbabwe (Mukwereza Citation2015; Shonhe Citation2019a). Little attention, however, has been given to how mechanisation articulates with patterns of accumulation, social differentiation and class dynamics. Based on a case study of one high potential farming area, this article offers an analysis of how, in Zimbabwe's post FTLRP setting, mechanisation is intertwined with ongoing processes of accumulation and social differentiation, asking: who has access to mechanisation in Zimbabwe's post-FTLRP agrarian setting, and how? How does mechanisation influence social differentiation and class formation, and through what pathways of accumulation?

Many studies have highlighted ongoing social differentiation and class formation in the post-FTLRP period (e.g. Moyo Citation2011; Cousins Citation2013; Zamchiya, Citation2012; Scoones et al. Citation2012; Mazwi et al. Citation2019; Muchetu Citation2020; Shonhe and Mtapuri Citation2020), but what is the role of mechanisation in this process across and within land use types? Moyo's (Citation2011) trimodal perspective highlights three groups: smallholders, including communal areas (CA) and smallholder resettlement areas (A1 and old resettlement farms); medium-scale farmers (A2 and small-scale commercial farms); and large farms/agro-estates. However, land size is only one factor influencing differentiation. This article therefore considers how mechanisation intertwines with complex social structures and political relations of Zimbabwe’s contemporary agrarian economy. Through a case study from Mvurwi area, the research explores how mechanisation not only is shaped but also shapes agrarian relations and accumulation processes, with mechanisation emerging as part of an elite state-driven national project (Bernstein Citation2003), supported in recent years by new Southern development partners.

Following this introduction, the next section contextualises agricultural mechanisation in Zimbabwe. Section 3 introduces the fieldwork site, Mvurwi, and outlines the methodology used. Section 4 analyses access to mechanisation (and tractors specifically) in Mvurwi, and how this is related to access to finance and shaped by patronage politics. Section 5 juxtaposes mechanisation with patterns of production, labour use and asset ownership and, on this basis, identifies pathways of accumulation that are noticeably feeding social differentiation in Mvurwi. Section 6 concludes.

2. The history of mechanisation in Zimbabwe

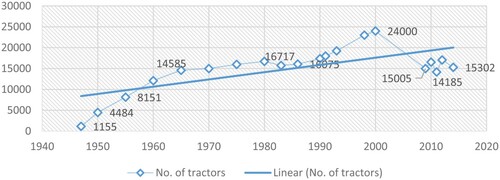

Since the early twentieth century, mechanisation has been a core part of agricultural policy, favouring certain groups of farmers. During the colonial era, policies prioritised settler commercial agriculture, encouraging intensification, especially after the Second World War (Dunlop Citation1971). The number of tractors held by white commercial farmers increased from an estimated 500 in 1945 to 4,484 by 1950 and 16,000 by 1975 ().

Figure 1. Historical tractorisation pattern for Zimbabwe. Source: author, compiled from Dunlop (Citation1971), FAOSTATS (Citation2019) and Zimstats (Citation2012, Citation2016)

Despite the increased use of tractors by white farmers, the spread of mechanisation to the native, Africa population was minimal (Pingali, Bigot, and Binswanger Citation1987). Relying on political and economic superiority, white farmers, who had a close relationship with the colonial government, maintained an advantage over the black peasantry (Phimister Citation1986). As the liberation war intensified from the mid-1970s and commercial agriculture got disrupted, tractor holdings stabilised, and imports declined.

After Independence, in 1980, the government introduced initiatives to increase the level of tractorisation amongst smallholders, including the Group Tractor Programme, the District Development Fund (DDF) and the Ministry of Local Government's Agricultural Rural Development Agencies (ARDA) (Rusike Citation1988). However, not much progress was achieved and the national stock of tractors actually declined to 15,763 by 1983 (), with only 0.4% of the communal households holding tractors by the 1983–84 season (Zimbabwe Central Statistical Office Citation1984).

While the Economic and Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) curtailed government intervention from 1991, it opened up opportunities for selling in international markets that led to specialised intensification in large-scale commercial agriculture (Moyo Citation2000). This resulted in the contraction of land utilisation and a drop in the demand for tractors from large scale farmers. At the same time, government-run tractor schemes for smallholders collapsed due to reduced government investment. Nevertheless, the total stock of tractors was 24,000 by 2000 ().

The FTLRP from 2000 altered the demand for draught power and tractors. State-run organisations were unable to provide sufficient tillage services (Hanyani-Mlambo Citation2004), and imports of tractors were initiated from various Eastern and Western countriesFootnote1, through private purchases, government-to-government agreements and the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) programmes. By 2005, less than 20% of farmers had access to power-driven equipment, compared to 49% who relied on animal ploughing (Moyo et al. Citation2009). Uneven access to tractors also persisted, with 70% of the A2 farmers holding tractors compared to 22% among smallholders (MAEMI Citation2009). A2 farmers entering joint venture arrangements with national and international investors were also able to mechanise.

Despite some imports, the total tractor stock declined to around 15,000 after land reform as many tractors were taken out of service or broke down due to poor maintenance related to shortage of foreign currency required for the importation of spare parts (Simalenga Citation2013). Favouritism of politically aligned A2 farmers in state-sponsored schemes further skewed access. In 2011, a new mechanisation programme targeting smallholder farmers was supported by a US$98 million loan from the Brazilian government (Cabral et al. Citation2016). Although fraught with political interference, the programme reached some smallholders via tractor cooperatives (Shonhe Citation2019a).

As this very brief history shows, tractors have been an important part of state policy for over a century. Seen as a route to intensification of agriculture and improved outputs, they have been widely promoted, yet policy efforts have been focused only on certain groups. During the colonial era, white settler farming was targeted, while after Independence it was communal area farmers who were the focus of tractorisation efforts. Since the land reform, tractors have become a focus for patronage, particularly among the A2 farmers.

Following an overview of the study methodology, the next sections look at who owns tractors and how they get them, and in turn how this affects trajectories of accumulation and patterns of social differentiation.

3. Study area, methods and different farming clusters

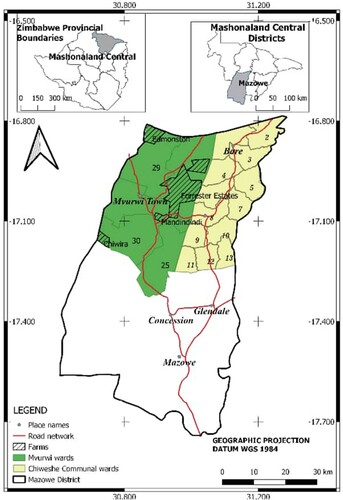

This study focuses on Mvurwi area, Mazowe district (). Mvurwi is situated nearly 100 km north-west of Harare and is classified as a high potential farming region, which receives an average rainfall of 800 mm per year. Intensive crop farming and animal husbandry are practised in this area. Maize and tobacco have been the two major crops grown commercially in the area since the colonial period.

Figure 2. Mvurwi study area. Source: Scoones et al. (Citation2020, 8).

Land reform in Mvurwi resulted in radical changes in land use and agricultural production patterns. By 2019, 4,529 A1 farmers and 319 A2 farmers had been settled on 105 former commercial farms. Some of these A2 farms are joint ventures between Chinese investors, former commercial farmers, local entrepreneurs or urban dwellers and the resettled farmers. In addition, there is one LSCF farm owned by a black Zimbabwean, which already existed in 2000. There is also one large estate operating under a Zimbabwe-Germany bilateral trade agreement. There are also 2,709 CA households within the Mvurwi section of Chiweshe communal area. Across the area, there are seven tractor cooperatives created as part of the programme between the governments of Brazil and Zimbabwe.

The study used a mixed methods design, combining quantitative with qualitative data and methods. Data collection comprised a cross-sectional household survey, in-depth interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs), conducted between 2017 and 2020. The survey was carried out with a sample of 874 farmers, comprising 520 CA farmers (with average land holdings of 2.5 ha), 310 A1 farmers (4.9 ha average) and 40 A2 farmers (54.2 ha average). The survey was carried out in: (i) A1 farms where the Brazilian tractor cooperatives were established – Donje, Mandindindi and Ruia A/B farms; (ii) three wards (1, 3 and 4) within the Chiweshe CA, selected based on their close proximity to and interaction with farmers in resettled areas; and (iii) A2 farms, with some being operated as joint ventures. Farms/households selected within each of these categories were chosen randomly.

Survey data were complemented by 24 in-depth interviews and four FGDs. The interviews focused on farmers’ life trajectories, patterns of accumulation and experiences linked to mechanisation access and machinery use. Respondents included: six CA farmers, eight A1 farmers and six A2 farmers, and officials from the Grain Marketing Body (GMB) and Agricultural Extension (Agritex) offices (see Appendix 1). A2 farmers comprised one LSCF, two joint ventures, one previously established estate and two independently operating farms owned by a former army officer and a local entrepreneur. FGDs aimed to get insights regarding tractor cooperatives, tractor allocation and hiring services. These were carried out at Donje, Ruia A, Chidziva and Mandindindi A1 farms, all of which have active tractor cooperatives. The FGDs included, on average, 12 farmers comprising members and non-members of tractor cooperatives, men and women and different age groups. The analysis also relied on complementary archival material from the Zimbabwe National Archives, the Central Statistical Office in Harare and the Agritex archive in Concession in Mazowe District.

Given the heterogeneity of farming households across and within the land use types, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to create clusters that differentiate households on the basis of a combination of factors (Alvarez et al. Citation2018). PCA is a multivariate technique used to reduce datasets with numerous correlated variables into smaller datasets of unrelated variables (known as principal components). A total of 16 variables was reduced to six principal components – marital status, tobacco area, fertiliser source, crop income, male permanent workers and perception of food security (see Appendix 2). In turn, six clusters were identified across land use types, where farming households shared similar characteristics. The following sections of this article investigate how these clusters relate to patterns of tractor use and ownership, examining the implications for accumulation and social differentiation.

4. The role of tractors in farming across land use types

Across the sample, encompassing different land use types, the different clusters are unevenly distributed (). CA farmers are overwhelmingly found in Cluster 1 (88.6%). Most A1 farmers are in Clusters 1 and 2 (46.1% and 28.7%, respectively), while A2 farmers are predominantly in Clusters 3, 4 and 6 (28.9%, 26.3% and 26.3%, respectively).

Table 1. Land area, assets, labour hiring, production metrics and sources of draft by land use type and cluster, Mvurwi, 2016/17 season.

Farmers within each cluster – characterised by a particular type of farming and asset ownership – use tractors in different ways. As shows, Cluster 1 represents the poorest households, with limited land holdings and the lowest levels of crop production. These households are concentrated in the communal areas and among the poorer A1 farmers. They make limited use of tractors, and these are nearly all hired. Cluster 2 is most common in A1 areas, where farmers mostly own their own oxen and farm independently on slightly larger areas, and with more income, including from tobacco. Cluster 3 farmers are common among less well-off A2 farmers. They mix the use of their own oxen with tractor hire – although a reasonable proportion of the farmers own them – and in total they produce relatively greater amounts of tobacco and maize. Cluster 4 households are richer still, with larger land holdings and more assets. They are only found in A2 and A1 areas, and make use of a mix of own tractors, hired tractors and own oxen for draft power and have higher crop outputs supported by more hiring of labour. Cluster 5 are mainly located among A2 and CA farmers. They receive the highest level of command agriculture support due to their connections with government, and because some of them are senior state bureaucrats. They also rely on their salaries to secure additional farming inputs, hire tractors and increase the size of their herds, on which they also rely for draft power. Cluster 6 households are the richest, with the greatest proportion of tractor ownership (especially in A2 farms). Many farmers in this cluster also have their own oxen for draft power and have the highest crop incomes associated with the largest hired workforces.

As shows, A2 farmers have significantly more access to tractors. Overall, 37.5% of A2 farmers own tractors and 43% hire tractor services. By comparison, only 3.7% of A1 farmers and 0.2% of CA farmers own tractors, while 25.8% of A1 farmers and 3.4% of CA farmers hire tractor services. Oxen are still the dominant power source for A1 and CA farmers, with 58.1% of A1 farmers and 72.4% of CA farmers using their animals for land preparation. By contrast, only 17.5% of A2 farmers make use of oxen for draft power. Oxen hiring services are also a source of power for 24.6% of CA farmers, but are less important for A1 farmers (13.5%). None of the A2 farmers hire in oxen or use hand hoeing for tillage purposes. Not surprisingly, with their larger land areas and greater asset base, A2 farmers are overwhelmingly more mechanised than CA and A1 smallholders.

Table 2. Average land size and area tilled, sources of draft and financing sources per land-use type in Mvurwi, 2016/17 season.

In other words, tractors take on very different roles within farming across our sample. In the poorer communal areas, tractors are rarely owned though sometimes hired, but limited land areas and lack of capitalisation make tractor use difficult, and most households make use of ox-drawn ploughs. The lack of uptake of tractors since the major programme of the 1980s continues. A1 farmers have larger land areas, tilling on average 4 ha in our sample. These farmers make use of tractors if they can, but the stock is limited, although some hire from nearby A2 farms and make use of tractors supplied through the cooperatives in these areas. It tends to be the richer A1 farmers, who have had a run of good harvests of tobacco and maize, who invest in tractors and the numbers in the area are gradually growing. It is the A2 farmers who need tractors if they are to make use of their large fields (average areas of 54.2 ha in our sample). However, lack of finance affects their ability to purchase tractors, and therefore many rely on hiring, and a surprising number still farm with ox-drawn ploughs, making only a limited use of their large farm areas (42.6% on average are tilled).

5. Access to tractors: reinvestment, financing and political connections

How then do different farmers gain access to tractors and tractor services, across and within the land-use types, and how do different types of financing and access to political connections, assist this?

In the post FTLRP period, and the context of Zimbabwe's enduring economic crisis and credit flight, farmers have struggled to access financing for purchasing farm equipment such as tractors. Government support for mechanisation programmes has been sporadic, and has declined over time due to reduced government capacity (Shonhe Citation2019b). As discussed below, access to tractors is linked to the ability to generate surpluses from farming and reinvest it in farm equipment. It is also linked to political connections and patronage networks, as well as access to private and public contract farming arrangements.

5.1. Access through reinvestment of surplus agrarian income

Reinvestment of agrarian surplus income is critical for those who are unable to access government tractor programmes or secure funding for acquiring productive farming equipment.

Some clusters achieve high annual returns annually and are thus able to reinvest in crop production, animal husbandry, and farming equipment acquisition. In the A2 farms, high crop sales income was achieved by farmers in Clusters 4, 5 and 6 (cf. ). Mr D, an A2 farmer (Cluster 4) who is thriving, indicated:

Having tractors of my own enabled me to do my farming on time, get better crop yields, and accumulate more farming assets. Because of this, I plan to buy another tractor under the new government scheme introduced earlier this year. I have already applied to CBZ bank. If the application doesn't succeed, I will buy an excellent second-hand tractor from Harare, using my maize and tobacco sales income. I might even sell some cattle to supplement the income. (Interview with Mr D, Arrowan farm, Mvurwi, January 2020)

I am one of the three farmers who have been able to buy tractors on this farm. When we got settled in 2000, I had no cattle of my own. However, by 2004, I had bought two heifers and these have since increased to sixteen. We sold our maize and tobacco crops and raised enough money to buy the tractor from an A2 farmer from a nearby farm in 2010. Now we can till our lands on time and hire out to farmers from the surrounding farms and from Chiweshe to raise additional funds to support our cropping programme. (Interview with Mr AM, Donje farm, Mvurwi, July 2020)

5.2. Agricultural financing through contracting

Contracting farming is an important source of financing for Mvurwi farmers. The survey data show the relationship between tractor ownership and contract farming across the sample (). A2 farmers, who have most access to tractors, also had greater access to contract farming for tobacco from private companies (35.9%) and command agriculture for maize from the state (47.5%). A1 and CA farmers are relatively disadvantaged. 17.5% of A1 farmers and 13.5% of CA farmers had access to contract farming, while 5.5% of A1 farmers and 2.9% of CA farmers had access to command agriculture. As discussed further below, those with greater access to command agriculture were most likely to be politically connected.

The most mechanised households tend to be those with higher access to contract farming and command agriculture. For example, among A2 farmers, those in Cluster 6 had significant access to contract farming (43.5%) and command agriculture support (52.2%), and also owned more tractors (). Similarly, A2 Cluster 4 farmers, who also had relatively high access to contract farming (40%) and command agriculture financing (30%), had reasonable access to tractors (20%) and recorded high levels of reliance on tractor hiring services (70%). Command agriculture financing was especially important for A2 Cluster 5 farmers where 66.7% had access. However, access to command agriculture does not necessarily result in tractor ownership for A2 farmers. This is the case of those in Cluster 5 who had high access to command agriculture (66.7%), low levels of maize and tobacco production and relatively low levels of tractor ownership. By contrast, the fewer A2 farmers in Clusters 1–3 had much less access to command agriculture, although quite a few still had contracts for tobacco. Many of these contracts were however only for one-hectare plots and did not release the level of financing required for purchasing tractors. Most farmers in these clusters did not own tractors and relied on tractor hiring services or their own oxen.

Among A1 farmers, access to command agriculture is small (5.5%), whereas contract farming is more extensive (17.5%). Although A1 farmers in Clusters 2 and 3 have greater access to contract farming (32.5% and 38.9%, respectively) when compared to Cluster 4 (25%), the latter has higher tractor holdings (33.3%) and 8.5% of these farmers have access to command agriculture. Despite having some access to contract farming, none of the A1 Cluster 2 farmers owned tractors or relied on tractor hiring services.

Mechanisation is very limited among the CA farmers, although some Cluster 2 farmers (4.6%) use tractor hiring services. Among the CA farmers, 13.5% had access to contract farming tobacco and only 2.9% to command agriculture. Among CA farmers, 61.5% of those in Cluster 5 have access to contract farming yet only 0.2% have tractors of their own (), and like the other clusters in the CA site, they mostly rely on animal power. Mrs JN (Cluster 3) noted:

Like many others here in Chiweshe, having cattle of your own is the most important issue for successful farming. To hire a tractor one has to approach resettled farmers in the A2 and A1 sectors as nobody in our area owns one. I have resigned to the idea that one day I will be able to buy a tractor. I have such a small piece of land that does not warrant the use of a tractor. Also, my annual income from crops is very low. Often we struggle to feed the family and often have to reduce the number of meals to only one per day. (Interview with Mr JN, Chiweshe area Mvurwi, February 2020)

5.3. Political connections and patronage

As one farmer explained, it was ‘mostly those with party positions … who accessed tractors and command agriculture support’ (interview with JH, Mvurwi, January 23rd, 2019). This is a pattern seen more widely as ZANU-PF leaders and those in the military, judiciary and public service benefitted through allocations by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, including both low cost tractor ‘loans’ and support through command agriculture (Shonhe Citation2019a). Cluster 5 farmers include many who are employed workers, including those in the civil service often occupying high positions. They were able to use their position to gain access to tractors under various government schemes (Magaisa Citation2020).

Although not all A2 farmers are politically connected, those in clusters 3, 4 and 6 rely on these connections to gain access to tractors and command agriculture support. Such access to political patronage networks is far less common in other land use types. With limited access to bank finance and the constraints inherent in crop-focused contract farming, political connections matter.

Political connections also matter for gaining access to tractors in tractor cooperatives where A1 and CA farmers are the beneficiaries. Under this scheme, smallholders who join the cooperatives are allocated tractors and tractor implements procured through the aid programme. There are seven cooperatives in Mvurwi and four of these are located at Hariana, Madhidhidhi, Donje and Chidziva farms. Focus group discussions with both members and non-members of the tractor cooperatives revealed how the process of establishing the cooperatives was politicised, often involving the conversion of local ZANU-PF structures into tractor cooperatives (FGD, Donje farm, Mvurwi, March 23, 2019). The Hariana farm cooperative was led by the former Ward Development Committee that was converted into the Tractor Cooperative Committee. At Chidziva farm, the Cooperative Committee is the former Committee of Seven, again linked to the party structures. At Madhidhidhi farm, the former ZANU-PF provincial governor, campaigning for primary elections for a by-election, allocated tractors to the members to increase his chances of being elected (Interview with GSD, Mvurwi, July 17, 2019).

Although access to tractors through cooperatives is important for smallholders, participation in the cooperatives remains relatively low. The numbers of tractors available is inadequate to satisfy total demand. For instance, at Hariana farm, only 30 out of a total of 302 farming households (9.9%) are members of the cooperative. The proportion is more significant at Donje farm, where 41 out of 160 households are cooperative members (26%), and at Chidziva farm, there are 15 out 56 households who are members (27%). Madhidhidhi farm has the highest membership proportion in our study area, with 50% participation (21 of 42 households). Thus, most farmers on these farms are non-members who rely on tractor hiring services and animal power. While the original allocation of tractors was highly politicised, cooperative members confirm that access to tractors and their use is not on the basis of political favours, despite some pressure from party members, as members reject political interference, preferring to maintain operational independence (interview with TG, Hariana farm, March 16 2019). Tractor hiring out services was mostly a commercial decision made by the cooperative members.

In sum, patronage politics mediate access to state support to mechanisation, both through command agriculture financing, mechanisation programmes supported by the Reserve Bank and via aid-funded programmes that supported the tractor cooperatives. This benefits a few, well-connected individuals, mostly in the A2 areas, while in the A1 areas the cooperatives are a site of political contestation as attempts to control them are resisted at the local level. The politics of tractor access is an important part of the contemporary story in Zimbabwe, as it has been before. However, overall the outcomes are patchy, with very few gaining access to new tractors – although an increasing tractor stock in the area feeds the hiring market for tractor services for others, including exchange between A2 and A1 and communal areas.

6. Tractors and the dynamics of accumulation

How then does this complex pattern of tractor access and use across clusters and land use types relate to dynamics of accumulation in Mvurwi?

Mr A explained how diverse sources enabled him to accumulate, including the purchase of tractors:

I have been involved in tobacco contract farming for the past ten years and in command agriculture for maize production since 2016. The two programmes work very well for my farming programmes as I can access inputs for tobacco and maize farming, respectively. Using funds earned from the sale of these agricultural commodities, I have bought three tractors, a disc harrow, two trailers, one truck, one mouldboard plough, one cultivator, one raw marker, six knapsack sprayers, two tractor-drawn disc ploughs over the past six years. I also bought four heifers eight years ago, and my herd has since grown to 16 cattle. Furthermore, I built one three-roomed brick house under corrugated zinc–iron sheets, one shed, one fowl run, and one brick toilet with a corrugated roof on the farm. (Interview with Mr A, Hariana farm, Mvurwi, June 17th, 2020)

Overall, do tractors make a difference to the possibilities of producing surplus and joining a trajectory of accumulation like Mr A? The survey data show that tractor owners among the A2 and A1 farmers cultivate relatively larger areas and register higher yields for both maize and tobacco than the average (). Among A2 farmers, those using their own tractors tilled an average of 50.4 ha, of which 12.7 ha was put under tobacco and 24.3 ha was used for maize. This resulted in 22,667 kgs of tobacco, with a yield of 1,785 kg/ha and 153.9 tonnes of maize, with a yield of 6.3 t/ha. In the A1 and CA areas, farmers using their own tractors tilled an average of 6 ha, of which 3 and 2.8 ha respectively was put under tobacco and 2.5 and 1.3 ha was put under maize. Tractor owners in A1 areas produced on average 7,000 kg of tobacco, with a yield of 1,374 kg/ha and 10.8 tonnes of maize, with a yield of 4.3 t/ha. The few CA tractor owners also produced the most tobacco (2,475 kgs) and maize (8.3 tonnes) and the highest yields (1,904 kg/ha for tobacco and 3 t/ha). By contrast, across all land use types, the outputs and yields for both tobacco and maize were lower for those who hired in tractors, or used their own or hired in oxen.

Table 3. Maize and tobacco production, productivity, and sales by source of power across farming models, Mvurwi, 2016/17 season.

The benefits of tractor ownership, as well as the challenges of access, are highlighted by one respondent. Mrs F is a resettled A1 farmer who migrated from Harare to Mvurwi in 1980, left her previous employment, and has since survived through farming, mainly growing tobacco and maize. She explained:

Only a few people do contract farming or own tractors in the area. Also, we struggle to hire tractors in this area, as it often takes very long to get one, even if you pay early. We had bought one using our pensions but we have since failed to maintain it and it now lies dysfunctional. We mostly hire from those who got tractors through the tractor cooperatives, but the demand is high, and often they fail to cope. As a result, our productivity remains low as we face difficulties in acquiring inputs and farm implements, including tractors. (Interview with Mrs F, Arrowan farm, Mvurwi, January 23rd, 2019)

7. Tractors and patterns of social differentiation

Given that tractors are associated with the possibilities of generating surpluses and so accumulation, what does this suggest about emerging patterns of social differentiation and class formation? A snapshot survey may not reveal longer term dynamics, but by combining survey data with qualitative insights and the cross-sectional analysis of patterns across clusters (cf. Oya Citation2007), we can begin to get an idea of how tractors articulate with patterns of social differentiation. The analysis here does not delve into the gendered, generational divisions and kinship dimensions, which adds layers of further complexity to the household level analysis attempted here.

The following sections link patterns of social differentiation and identifications of ‘class’ to statistically-derived clusters – and associated patterns of production, labour use, asset ownership and so on (see Appendix 2) – and their link to tractor ownership and use. Broadly associated with different clusters, four ‘class’ groupings are identified, each associated with a particular trajectory of accumulation (or lack of it), and pattern of tractor ownership or use (or lack of it). These are: poor peasants, petty commodity producers, semi-proletariat, and the rural bourgeoisie. These groupings are consistent with previous studies on agrarian change in Zimbabwe (Weiner et al. Citation1985; Cousins, Weiner, and Amin Citation1992; Cousins Citation2010; Scoones et al. Citation2012; Moyo Citation2011; Shonhe and Mtapuri Citation2020; Shonhe, Scoones, and Murimbarimba Citation2020). The discussion starts with the poorest group, the least likely to make use of tractors.

7.1. Poor peasants

Farmers in Clusters 1 and 2 across the three land-use types struggle to produce surplus commodities for selling in the market. Farmers in these clusters share common characteristics in that they do not access contract farming nor command agriculture funding and very few have access to their own tractors. These farmers can be classified as ‘poor peasants’. They are associated with family farming where there is high dependence on households’ own labour. However, due to the production of tobacco, across farming classes, some poor peasants now employ labour to help them during some critical stages of the season, including during planting, weeding, reaping and grading of the crop. The hired labour is usually paid by way of maize grain, through the offering of a piece of land, or a portion of the crop produced or by way of cash during or at the end of the season. Poor peasants experience a reproduction squeeze and thus struggle with capital and labour reproduction, often facing a dilemma between focusing on consumption or investment.

7.2. Petty commodity producers

Farmers in Clusters 3 and 4 can be described as ‘petty commodity producers’. The majority are A2 farmers with relatively smaller cropped areas, while a few are A1 farmers, who engage both in capitalist and peasant family farm production, hiring in labour and producing regular surpluses, which are invested on-farm, including building up significant livestock holdings. They often have highly diversified livelihoods and straddle farm and off-farm activities, including informal trading and artisanal mining. They have access to contract farming and command agriculture and so have significant access to tractors of their own, especially among A2 and A1 farmers. Their levels of tobacco and maize production is relatively high, showing patterns of expanded reproduction and via intensive engagement in tobacco production and involvement in global commodity circuits (Scoones et al. Citation2012; Cousins Citation2010).

7.3. Semi-proletariat

Farmers in Cluster 5 can be characterised as ‘semi-proletariat’. They work in urban centres and use their wages to support agricultural investments. They do own tractors to compensate for lack of labour to tend livestock and engage in ox-ploughing, due to absent workers in the household. However, tractors purchased through wage employment are often not functional, as the costs of maintenance are too high. Due to wage-based agricultural financing, they are productive in crop farming, gaining decent incomes. Many are able to gain access to command agriculture through urban work connections, and thus achieve significant crop sales annually. Combining on and off farm sources, they show patterns of extended reproduction, reinvesting in the farm. In the A2 and A1 sites, such households are associated with high labour employment, often hiring farm managers to support their operations while they work in urban areas. However, these worker-peasants invest less in houses, as very often they reside in homes in town.

7.4. Rural bourgeoisie

Farmers in Cluster 6 represent a type of ‘rural bourgeoisie’. They are the most mechanised group (60.9% own tractors and 34.7% hire them). This is not surprising given their high levels of access to tractor programmes, contract farming and command agriculture. This group is politically connected and some occupy key positions in the army and government, where the command agriculture programme is managed. Of all the groups, they employ the most workers and own the highest number of cattle. Their rural housing is of high quality and extensive, and they have invested in a range of farm assets, as well as often having urban homes and connections. They are highly incorporated in commodity circuits and show patterns of sustained expanded reproduction. They are ‘driven by the compulsion to accumulate, innovate, compete and reinvest’ (Oya Citation2007, 460), but do so on the back of state support and patronage, which has the effect of forming rural capitalist classes in the process (cf. Amanor Citation2005; Bates Citation1981).

In sum, the statistically derived clusters, based on the principal components analysis across survey variables, can be linked to distinct rural classes. We can see that tractors are selectively associated with each group. Whether tractor ownership/access is more of a cause or consequence of class formation remains a question as there are a range of factors affecting the dynamics of accumulation and patterns of social differentiation, as the paper has shown.

8. Conclusion

Land reform in Zimbabwe since 2000 has created a new agrarian structure, with altered opportunities for accumulation, across smaller and larger farms. Mechanisation – and specifically the possession and/or use of tractors – is linked to patterns of accumulation and social differentiation, across and within land use types. There has been a long history of mechanisation in Zimbabwe, but the impacts on accumulation have been patchy. There have been many constraints for smaller farmers, who have alternative options for draft power, and there has been extensive corruption around tractor schemes.

This research investigated the current dynamics of mechanisation in the high potential area of Mvurwi, where extensive land reform took place. The research looked across all land use categories – communal areas, smallholder resettlement schemes (A1) and medium-scale resettlement A2 farms – to investigate the relationships between tractor ownership and use (through hiring/borrowing) and differential patterns of accumulation. A principal components analysis identified six clusters. Across these clusters different trajectories of accumulation are observed, with some associated with ownership and use of tractors. ‘Poor peasants’ show limited accumulation and simple reproduction, and rarely use tractors. ‘Petty commodity producers’ generate surpluses as part of diversified livelihoods, and may invest in tractors, although their maintenance is a challenge. ‘Worker peasants’ rely on off-farm town-based income earning for investment, and urban connections also provide opportunities for patronage connections and access to tractor schemes. It is only the emerging ‘rural bourgeoisie’ who rely on tractors as a core part of their activity. They are concentrated in the medium-scale A2 farms and benefit significantly from patronage support through political connections.

Overall, those with higher tractor holdings earn higher crop incomes, both maize and tobacco, with both higher outputs and yields. In turn, those with higher incomes – from both on and off farm sources, including via patronage sources – are able to acquire tractors to improve on their productivity further, thus propelling further accumulation and greater social differentiation. Thus, agricultural mechanisation acts to reinforce uneven accumulation patterns already in motion. Political connections and access to agricultural financing from contracting and the state-led programme of command agriculture favour these elites.

Tractors are therefore important for supporting accumulation trajectories, but their ownership and use reflects patterns of social differentiation, with largely richer, well-connected farmers benefiting the most. Indeed, political support to such farmers, via various schemes focused on providing tractors from both the state and aid programmes, reinforce divergent accumulation trajectories and patterns of social differentiation. Tractors are therefore significant for rural politics, through the formation of an elite, especially through patronage processes. That said, despite the focus on tractors and mechanisation more generally as a route to intensification of agriculture over many years, the ownership and use of tractors remains constrained, with mechanisation being only a part of the wider story of post land reform agrarian change, relevant to only some people in some places.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the funding provided by the Agricultural Policy Research in Africa (APRA) programme to carry out the study. APRA is funded by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO). The author acknowledges the valuable support of farmers in Mvurwi, along with local officials in government departments. Reviews and comments of multiple earlier versions of this paper were provided by Professor Ian Scoones and Dr Lidia Cabral, along with two external reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Toendepi Shonhe

Toendepi Shonhe (PhD) is an agrarian political economist whose research interests includes agrarian change, agricultural mechanisation and commercialisation, agricultural labour, rural development and poverty studies. He has written extensively on the broad array of agricultural development and economic development in Africa. Toendepi is a researcher based at the Thabo Mbeki African School of International and Public Relations.

Notes

1 The countries included: Belarus, China, Hong Kong, India, Iran, Kenya, Malaysia, Mauritius, South Africa, South Korea, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Zambia.

References

- African Development Bank. 2016. “African Countries Urged to Prioritize Mechanized Agriculture for Increased Productivity.” Accessed November 30, 2016. http://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/article/african-countries-urged-to-prioritize-mechanized-agriculture-for-increased-productivity-16096/.

- Alvarez, S., C. J. Timler, M. Michalscheck, W. Paas, K. Descheemaeker, P. Tittonell, J. A. Andersson, and J. C. Groot. 2018. “Capturing Farm Diversity with Hypothesis-Based Typologies: An Innovative Methodological Framework for Farming System Typology Development.” PLoS One 13 (5): e0194757.

- Amanor, K. S. 2005. “Agricultural Markets in West Africa: Frontiers, Agribusiness and Social Differentiation.” IDS Bulletin 36 (2).

- AOSTAT (2019). Food Agriculture and Organization (FAOSTAT). Retrieved from https://nam12.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.fao.org%2Ffaostat%2Fen%2F%23data%2FQC&data=04%7C01%7Cprakash%40novatechset.com%7C0db5e8ab2a8a48018b8b08d90a9f050d%7Ca03a7f6cfbc84b5fb16bf634dbe1a862%7C0%7C0%7C637552500385242504%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJWIjoiMC4wLjAwMDAiLCJQIjoiV2luMzIiLCJBTiI6Ik1haWwiLCJXVCI6Mn0%3D%7C1000&sdata=QJSLqs8BZezsR1fioNHgFRsQrCMOU1EONMPTt8LjHXo%3D&reserved=0

- Bates, R. 1981. Markets and Statesin Tropical Africa: The Political Basis of Agricultural Policies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bernstein, H. 2003. “Land Reform in Southern Africa in World-Historical Perspective.” Review of African Political Economy 30 (96): 203–226.

- Binswanger, H. 1986. “Agricultural Mechanisation: A Comparative Historical Perspective.” The World Bank Research Observer 1 (1): 27–56.

- Cabral, L., A. Favareto, L. Mukwereza, and K. Amanor. 2016. “Brazil's Agricultural Politics in Africa: More Food International and the Disputed Meanings of ‘Family Farming’.” World Development 100 (81): 47–60.

- Cabral, L., A. Shankland, A. Favareto, and A. C. Vaz. 2013. “Brazil–Africa Agricultural Cooperation Encounters: Drivers, Narratives and Imaginaries of Africa and Development.” IDS Bulletin 44 (4): 53–68.

- Cousins, B. 2010. What is a ‘Smallholder’. PLAAS, University of the Western Cape, Working Paper, 16.

- Cousins, B. 2013. “Smallholder Irrigation Schemes, Agrarian Reform and ‘Accumulation from Above and from Below’ in South Africa.” Journal of Agrarian Change 13 (1): 116–139.

- Cousins, B., D. Weiner, and N. Amin. 1992. “Social Differentiation in the Communal Lands of Zimbabwe.” Review of African Political Economy 19 (53): 5–24.

- Dharmasiri, L. M. 2012. “Measuring Agricultural Productivity using the Average Productivity Index (API).” Sri Lanka Journal of Advanced Social Studies 1 (2): 25–44.

- Dunlop, H. 1971. The Development of European Agriculture in Rhodesia 1945–1965. Department of Economics, Paper 5: Salisbury, University of Rhodesia.

- FAO and AUC. 2018. Sustainable Agricultural Mechanization: A Framework for Africa. Addis Ababa: Food and Agricultural Organization and Africa Union Commission.

- Hanyani-Mlambo, B. T. 2004. The Status of Farm Level Mechanization, Facilities, Services, Access Mechanisms and Strategies for Improving Mechanization in Zimbabwean Agricultural Systems. Harare: FAO assessment mission report.

- Houmy, K., J. Lawrence, J. Clarke, E. Ashburner, and J. Kienzle. 2013. Agricultural Mechanization in sub-Saharan Africa: Guidelines for Preparing a Strategy. Vol. 22. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- MAEMI (Ministry of Agricultural Engineering, Mechanization and Irrigation). 2009. Agricultural Engineering Mechanization and Irrigation Strategy Framework: 2008–2058. Draft Report, Harare: Government Printers.

- Magaisa, A. 2020. ‘BSR EXCLUSIVE: Beneficiaries of the RBZ Farm Mechanisation Scheme > July 18. The Big Saturday Read Blog. Accessed on July 21 2020.

- Mazwi, F., A. Chemura, G. T. Mudimu, and W. Chambati. 2019. “Political Economy of Command Agriculture in Zimbabwe: A State-led Contract Farming Model. Agrarian South.” Journal of Political Economy 8 (1–2): 232–257.

- Moyo, S. 2011. “Changing Agrarian Relations After Redistributive Land Reform in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (5): 939–966.

- Moyo, S. 2000. Land Reform under Structural Adjustment in Zimbabwe: Land Use Change in the Mashonaland Provinces. Land Reform under Structural Adjustment in Zimbabwe: Land Use Change in the Mashonaland Provinces. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute.

- Moyo, S., W. Chambati, F. Mazwi, and R. Muchetu. 2014. Land Use, Agricultural Production and Food Security Survey: Trends and Tendencies, 2013/14. African Experiences. Harare: African Institute for Agrarian Studies, Eastlea.

- Moyo, S., W. Chambati, T. Murisa, D. Siziba, C. Dangwa, K. Mujeyi, and N. Nyoni. 2009. Fast Track Land Reform Baseline Survey in Zimbabwe: Trends and Tendencies, 2005/06. Harare: African Institute for Agrarian Studies.

- Muchetu, R. G. 2020. Restructuring Agricultural Cooperatives in the State-Market Vortex: The Cases in Zimbabwe and Japan. A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Doshisha University Graduate School Of Global Studies.

- Mukwereza, L. 2015. Zimbabwe-Brazil cooperation through the More Food Africa programme (Working paper 116). Brighton: Future Agricultures Consortium.

- Oya, C. 2007. “Stories of Rural Accumulation in Africa: Trajectories and Transitions among Rural Capitalists in Senegal.” Journal of Agrarian Change 7 (4): 453–493.

- Phimister, I. 1986. “Commodity Relations and Class Formation in the Zimbabwean Countryside, 1898–1920.” Journal of Peasant Studies 13 (1): 240–257.

- Pingali, P., Y. Bigot, and H.P. Binswanger. 1987. Agricultural Mechanization and the Evolution of Farming systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank.

- Rusike, J. 1988. Prospects for Agricultural Mechanisation in Communal Farming Systems: A Case Study of Chiweshe Tractors. Mechanization Project. Unpublished MPhil. Thesis, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Zimbabwe.

- Scoones, I., N. Marongwe, B. Mavedzenge, J. Mahenehene, F. Murimbarimba, and C. Sukume. 2010. Zimbabwe's Land Reform: Myths & Realities. Oxford: James Currey.

- Scoones, I., N. Marongwe, B. Mavedzenge, F. Murimbarimba, J. Mahenehene, and C. Sukume. 2012. “Livelihoods After Land Reform in Zimbabwe: Understanding Processes of Rural Differentiation.” Journal of Agrarian Change 12 (4): 503–527.

- Scoones, I., B. Mavedzenge, F. Murimbarimba, and C. Sukume. 2018. “Tobacco, Contract Farming, and Agrarian Change in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Agrarian Change 18 (1): 22–42.

- Scoones, I., T. Shonhe, T. Chitapi, C. Maguranyanga, and S. Mutimbanyoka. 2020. Agricultural Commercialisation in Northern Zimbabwe: Crises, Conjuctures and Contingencies, 1890–2020, Working Paper 35. Brighton: Future Agricultures Consortium.

- Shonhe, T. 2019a. Tractors and Agrarian Transformation in Zimbabwe: Insights from Mvurwi. APRA working paper 21, Brighton: Future Agricultures Consortium.

- Shonhe, T. 2019b. “The Changing Agrarian Economy in Zimbabwe, 15 Years After the Fast Track Land Reform Programme.” Review of African Political Economy 46 (159): 14–32.

- Shonhe, T., and O. Mtapuri. 2020. “Zimbabwe's Emerging Farmer Classification Model: A ‘New’ Countryside.” Review of African Political Economy 47 (1): 1–19.

- Shonhe, T., I. Scoones, and F. Murimbarimba. 2020. “Medium-scale Commercial Agriculture in Zimbabwe: The Experience of A2 Resettlement Farms.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 58 (4): 601–626.

- Simalenga T. E. 2013. Agricultural Mechanization in Southern African Countries. Silverton, Pretoria, South Africa: Institute for Agricultural Engineering.

- Weiner, D., S. Moyo, B. Munslow, and P. O'Keefe. 1985. “Land use and Agricultural Productivity in Zimbabwe.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 23 (2): 251–285.

- Zamchiya, P., 2012. “Agrarian Change in Zimbabwe: Politics, Production and Accumulation.” A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Oxford.

- Zimbabwe Central Statistical Office. 1984. “Zimbabwe National Household Survey Capability Programme.” Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development, Government of Zimbabwe, Harare.

- Zimstats. 2012. “Zimbabwe Statistics Office, Agricultural Production Statistics.” Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development, Government of Zimbabwe, Harare.

- ZimStats. 2016. Available from http://www.zimstat.co.zw/. Accessed 20 November 2016.

Appendices

Appendix 2b. Communalities variable extraction (principal components shaded)