ABSTRACT

This paper explores the organization of production in Rwanda’s main coffee producing zone. Most rural households in the region have limited access to land and stable employment. Yet, while differences in property and employment appear small from afar, this paper shows why they are consequential: even when marginal, these differences interact with time and market pressures (e.g. relative dependence on household food production or need for cash) that shape the complex and gendered labour relations between and within generally land-poor households. In a context of heightened precarity, such a labour-centred approach helps chart the prevailing trajectories of accumulation and exploitation.

Introduction

After the 1994 genocide, Rwanda experienced a remarkable economic recovery with annual GDP per capita growth averaging 4.6 percent between 1999 and 2019 (World Bank Citation2020). The country went from having a largely agriculture-based economy (32 percent value added of GDP in 1999) to a more diversified structure that still benefits from the agricultural sector’s stable contributions to domestic product (24 percent in 2019) and employment (62 percent in 2019, World Bank Citation2020). In recent years, Rwanda’s agricultural sector has been significantly transformed with a green-revolution-style modernization package including a new land law and a market-oriented crop intensification programme (CIP).Footnote1

While the official discourse highlights productivity gains and other improvements at the macro level, a significant subset of scholars portrays a more nuanced picture and calls for investigations of the ‘lived experiences on the ground’ (Ansoms et al. Citation2018, 1). These more granular contributions have substantially advanced our understanding of Rwanda’s agrarian change. However, most have focused on land issues, livelihoods in general or the specific impacts of policy interventions. A bottom-up perspective on rural labour relations and agrarian class dynamics has been largely missing. This paper aims to fill that gap using survey and qualitative fieldwork data from Nyamasheke district – Rwanda’s main coffee producing region. Our contribution thereby contributes to the argument more recently put forward that there is a vibrancy in African rural labour markets that has been often overlooked by scholars.Footnote2

By focusing on labour and class relations, we identify important variations among similarly land-poor households with consequences for their experiences of agrarian change. Although nested in global relations of exploitation, these relations are reproduced locally on the basis of exploitative interactions exemplified in what Mike Davis (Citation2006, 181) calls ‘relentless micro-capitalism’. Our contribution, grounded in the accounts of rural workers-cum-producers, herewith follows Newbury and Newbury’s (Citation2000, 868) call to ‘[bring] the peasants back in’ to Rwandan studies.

As in many parts of the world (see for example Hart, Turton, and White Citation1989), decades of export commodity production and pressure over land have not resulted in a clean polarization between groups of landowners and groups of rural proletarians in Nyamasheke. The vast majority of the population has access to some land for agricultural production (over 90 percent of households in our sample, with an average landholding of 0.29 ha per household) but, importantly, also depends on casual agricultural wage employment for their social reproduction – making an analysis of rural labour markets indispensable. This paper aims to understand how property and labour relations reveal marked forms of differentiation and power relations in a context of no prominent class polarization.

By using a class-relational approach, this paper examines different trajectories of accumulation and exploitation and makes sense of the production relations in which households take part (Campling et al. Citation2016). The article focuses on forms of surplus value extraction and the power relations that mediate them. We start by outlining our research design and data collection process. The second part introduces land relations and coffee production in Nyamasheke, providing a baseline against which to examine the diverse work engagements of our respondents. The third section presents labour relations as a way to observe and analyse class and applies a quantitative tool developed by Patnaik (Citation1976; Citation1987) to observe class positions in Nyamasheke. While useful, this approach is insufficient to account for the multidimensional and dynamic nature of classes. Therefore, in section four, we adopt a relational approach to instead examine the drivers, functions and power relations underlying the prevailing forms of surplus value extraction in Nyamasheke: wage labour, sharecropping and cattle-sharing. The final section argues that although peoples’ experience of surplus extraction is predominately shaped by their access to land, their labour relations are significant in two ways. First, in a temporal way: time matters because labour mobilization is predicated on the relative urgency of some households to get access to food or cash. Second, in relation to commodification pressures: markets matter because labour mobilization depends on the different market compulsions that households experience and the different markets they participate in as a result. The relative lack of access to means of production or stable employment presents structural limits to a household’s reproduction strategy. What our case study shows, though, is that these structural conditions, especially in contexts of no sharp polarization, are mediated at the household level predominantly in the form of time pressures and market compulsions. Temporality and commodification are thus crucial to understanding the tensions of localized micro-capitalism.

Research design and data collection

Fieldwork for this paper, conducted between October 2018 and March 2019, used a mixed-methods approach to observe class relations at the village level. Nyamasheke district, located in Western Province, was purposely selected because it is the main coffee producing region of Rwanda (NISR Citation2012; Migambi Citation2014). Compared with other rural areas of Rwanda, Western Province has the smallest average of cultivated land per farming household (NISR Citation2012), partially linked to its mountainous terrain and lake access. But as in most farming regions of Rwanda, smallholder farmers end up having to combine food production for own consumption, commodity production and wage employment (Bigler et al. Citation2017).

Fieldwork consisted of an extensive household survey and several qualitative data collection methods. The sampling strategy for the survey was as follows: we purposively selected two dynamic coffee-producing sectors in Nyamasheke and two sectors where previous research had been conducted (Erlebach Citation2006). In each sector, two villages and then a number of households proportional to the size of the village were selected using systematic random sampling. This resulted in a sample of 233 households across eight villages. The questionnaire asked about a wide array of household and individual characteristics with a focus on work and land relations. As rural labour markets are difficult to capture, we implemented a number of measures to ensure that the extent and diversity of wage employment were captured in our sample (Oya Citation2015a), such as the enumeration of all relevant economic activities (as opposed to focusing on the main occupation only) and the inclusion of any type of compensation – whether in kind or in cash and for whatever time period.

We also conducted qualitative fieldwork in three of the surveyed villages that exemplified different socio-ecological conditions. This included interviews with key informants, such as coffee washing station managers and village leaders; participatory observation; thirty in-depth interviews and three life stories. Household interviews were conducted with wives and husbands when possible and with the household head in the case of single-headed households.Footnote3 Respondents were purposively selected from surveyed households to represent the most land-poor and land-rich households. The second round included six repeat interviews as well as the three life story interviews.

Land and production in western Rwanda

In the last two decades, the government of Rwanda has undertaken sweeping agricultural reforms as well as large-scale investments in education, health and infrastructure. Rwanda also established wide-ranging social protection programmes with some positive, yet uneven, impacts, including improvements in access to employment and public services (Ruberangeyo, Ayebare, and de Bex Citation2011; Pavanello et al. Citation2016; Ezeanya-Esiobu Citation2017).

These efforts notwithstanding, the extent to which Rwanda’s growth trajectory translated into the reduction of poverty and inequality remains a matter of debate (Orrnert Citation2018; Okito Citation2019). Despite being the heartland of Rwanda’s coffee production, Nyamasheke remains the poorest district of the country with 70 percent of the population in poverty (NISR Citation2018a). Western Province is the most food-insecure region of the country and, in Nyamasheke, 21 percent of households are food-insecure (WFP Citation2018).Footnote4 To understand the production relations underlying this setting, this section examines property and production relations in Nyamasheke with an emphasis on coffee production, the district’s main cash crop.

Property relations in a context of high pressure over land

Rwanda has a comparatively high population density and skewed and fragmented land distribution (MINAGRI Citation2012). The average size of cultivated land per farming household is estimated at 0.59 ha for the whole country and at 0.49 ha for Nyamasheke (NISR Citation2012). Erlebach (Citation2006) reports the average size of cultivated land per household to be even lower at around 0.2 ha in the Rwamatamu area (in Nyamasheke). This resonates with our sample in which mean landholdings are 0.29 ha per household.Footnote5 This highlights the need, experienced by most households, to engage in alternative strategies to make a living. Yet, land retains strong meaning: as the locus of home and food provision, it secures a modicum of subsistence. The extreme nature of land fragmentation is illustrated by the fact that there are only 12 landless households and only 11 households with more than 1 ha of cultivated land for the 190 households that provided information for these variables. Most of the differentiation referred to in this paper takes place among households with less than a hectare of land (), so while the range of the land distribution is narrow, there is still a very high level of inequality among, in absolute terms, predominantly land-poor households. While we lack panel data for our sample, anecdotal evidence suggests that the land distribution has become more unequal over time, in line with other studies (Pritchard Citation2013).

Table 1. Distribution of households according to operational landholding (n = 190).

Rwanda implemented comprehensive land tenure reform through the 2004 land policy and the land laws of 2005 and 2013. The reform made registration compulsory and had the effect of formalizing and individualizing property relations (see Leegwater Citation2015). This intensified commodification and has been constitutive of class relations in several ways: title transfers are painstakingly slow, especially for returnees trying to access land, and land markets exacerbate class differentiation as vulnerable households are prone to distress sales while land purchases remain prohibitively expensive for most. Although inheritance continues to be the main route to acquire land and women were granted equal rights of inheritance in 1999, their access to land remains problematic (Isaksson Citation2015; Bayisenge Citation2018; Bigler et al. Citation2019). For many women, especially those whose parents died before the reform, access depends upon what they can claim through marriage and is often mediated by family relations. Women that are unofficially married have almost no tenure security, as was the case of one of our respondents who had to move to live with her parents after the death of her partner.

Coffee in Nyamasheke

The economy of Nyamasheke revolves around the production of coffee for export. Coffee was introduced to Rwanda in 1904 by German missionaries (Guariso, Ngabitsinze, and Verpoorten Citation2012). Coffee trees and cultivation knowledge are usually handed down in families over generations and have taken on important cultural significance.

Today, coffee farming is dominated by smallholders. Coffee is the country’s second most important agricultural export product after tea, accounting for around 15 percent of agricultural export value (MINAGRI Citation2019).

The Rwandan state intervenes strongly in the coffee sector through the National Agricultural Export Development Board (NAEB). In 2016, NAEB instituted a zoning policy whereby all farmers are required to sell their coffee to designated, and often privately-owned, washing stations for processing (Gerard, Clay, and Lopez Citation2017). Farmers can sell their coffee cherries either directly at the washing station or via official buyers licensed by the washing station. Buyers – ‘acheteurs’, usually better-off villagers – are stationed at strategic locations and buy up the coffee from nearby farmers in their zones who usually bring it to them on foot. The production of semi-washed coffee, in which the coffee is de-pulped and dried by the farmers, is heavily discouraged (NAEB Citation2018), limiting opportunities for farmers to add value to their product and reap higher prices.

NAEB enforces a minimum price, over which washing stations can offer a premium. The Coffee Exporters and Processors Association of Rwanda (CEPAR) organizes the distribution of fertilizers and pesticides which are predominantly financed with export fees – farmers thus pay for these inputs indirectly (Gerard et al. Citation2018). Despite these measures, many coffee growers in our sample complained about a continued loss of purchasing power, arguing that variable production and living costs are not reflected in disappointingly low coffee prices.

In Nyamasheke, almost all coffee is grown by farming households. There are only a dozen large-scale coffee plantations (with more than 5,000 coffee trees) in the administrative sectors where we conducted the survey, yet these are very important employers, particularly during the harvesting season. Coffee cooperatives are also rare.

Coffee is the most important cash crop in our study region: 43 percent of all the households with land access in our sample grow coffee for sale. Proceeds from coffee are often used to pay for clothes, hoes, health insurance and school expenses. Coffee farmers tend to be considered more creditworthy than other farmers and have easier access to loans guaranteed by their coffee sales.Footnote6

There are, however, important entry barriers to coffee farming that help explain why the average operational holding of coffee-producing households is 0.41 ha in contrast to 0.23 ha for households with land access that do not produce any coffee. Furthermore, only 40 percent of farmers with less than 0.25 ha of land (the largest category in our sample) grow coffee.

First, coffee is a perennial crop with a single harvest per year. Thus, coffee farmers need a means of subsistence to support themselves between coffee harvests, which not all farmers manage. Hélène is a widow with a small plot but does not grow any coffee.Footnote7 Instead she works for wages and grows soybeans, beans and cassava for own consumption. When we asked why she does not plant coffee, she said: ‘The farm is too small and the coffee takes too long. I can harvest at the end of maybe one year. So, it will not be good because I need food for my children’. Second, coffee requires a certain level of capital investment, since Arabica trees only start producing cherries after three to four years (Guariso, Ngabitsinze, and Verpoorten Citation2012). In the meantime, they also require inputs, which not everyone can access.

Nevertheless, coffee is crucial in Nyamasheke given its direct and indirect spillover effects as a labour-intensive crop. Coffee is a key catalyst of the local labour market and provides wage-earning opportunities, especially for people who cannot produce coffee.Footnote8 Since few households have the means to produce enough food to sustain themselves all year long, most need to complement their own production with sharecropping or other forms of work.

A labour-centred approach to class relations

Recent contributions to class analysis stress the usefulness of a labour-centred approach (Selwyn Citation2016). These contributions are themselves nested within a longer tradition of thinking about class in relational terms. A class-relational approach emphasizes dialectical and unequal relationships underpinning different forms and modes of exploitation and accumulation (Campling et al. Citation2016; Pattenden Citation2016). Importantly, classes are seen as intersecting with other sources of oppression such as gender or caste: their associated trajectories are open-ended rather than linear (Pattenden Citation2016). Class boundaries are often fluid, and class positions themselves can be unstable, with households combining different class elements and oscillating between various class positions across time, e.g. seasonally or across life cycles (Lerche Citation2010). In this section, we lay out what a labour-centred analysis entails and use it to interrogate class relations in rural Nyamasheke.

Labour exploitation in class analysis

The world of work opens a window to observe the relations and struggles of agrarian societies in transition. First, it sheds a light on the measures deployed by employers to monitor and discipline workers and the many acts of defiance and resistance. Second, the coexistence of inter-household hiring and forms of self-employment requires us to account for occupational multiplicity, a key feature of rural livelihoods. Third, a labour-centred approach helps expose the often disguised, unequal and exploitative work relations that are at the core of many institutional arrangements – something we will examine in the context of land rentals and sharecropping. A labour-centred perspective is therefore a fruitful way to explore class relations and grasp their multidimensional character.

We make use of two important contributions that put labour relations at the centre. On the conceptual side, the category of ‘classes of labour’ (Bernstein Citation2010) has been developed to capture ‘the growing numbers … who now depend – directly and indirectly – on the sale of their labour power for their own daily reproduction’ (Panitch et al. Citation2001, ix, cited in Bernstein Citation2010, 110–111, italics by Bernstein). This pays attention to the diversity of labour encounters across rural worlds, notably the many marginal farmer households engaging in casual wage employment (Lerche Citation2010; Pattenden Citation2016). Unlike Bernstein, who would include some petty commodity producers in this group, we will distinguish ‘workers’ (whose main economic activity involves working for others) from ‘petty commodity producers’ (whose own labour is the pillar of their farming).

On the other hand, for the purposes of observation, we build on a tool to measure labour exploitation developed by Patnaik (Citation1976; Citation1987) and used in various contexts. It sums up the class positions of different households in relation to their work arrangements: ‘[w]hile no single index can capture class status with absolute accuracy, […] the use of outside labour relative to the use of family labour, would be the most reliable single index for categorising the peasantry’ (Patnaik Citation1976, A-84, italics in original). Patnaik’s index considers possession of the means of production, intensity of the production effort and whether labour is predominantly hired in or out. This tool expands on indices based solely on acreage by incorporating the intensity and organization of (re-)production. Acreage or asset-based class indices would be unhelpful in the Rwandan context where acute land scarcity means that ownership differences can be small in absolute terms and at the same time result in gross inequality. A labour-centred perspective does not negate the importance of access to the means of production but incorporates the different arrangements households are entering in response. It highlights that land access is not the only class-forming variable, but that class is contingent on other factors such as social connections, the capacity to mobilize labour power and access to wage employment.

Class positions as a starting point

We have adapted the labour exploitation index to the Nyamasheke context.Footnote9 First, we adjusted the class structure to distinguish between households that were primarily selling labour power, primarily self-employed or primarily buying labour power. A second adaptation was to include non-agricultural work in our analysis.Footnote10 Third, wage work paid in kind as well as the work imputed into sharecropping and land rentals constitute an important mechanism for surplus appropriation and were therefore included in the calculation of the index.Footnote11 On the other hand, kuguzanya (traditional labour exchange) was excluded because it is, as it is practised in Nyamasheke, a reciprocal arrangement (as will be shown below). Finally, and building on Kitching’s (Citation1980) observations in Kenya, two additional classes of households were added: households with access to professional jobs (high-skilled, formal, non-agricultural workers such as teachers and nurses) and households that depend mostly on non-agricultural self-employment (petty traders and shop owners). Patnaik assumed uniform labour productivity, but this does not hold in Nyamasheke. Compared to ‘workers’ and ‘petty commodity producers’, ‘professionals’ and ‘retailers and traders’ respectively engage in very different forms of work with different labour productivities.

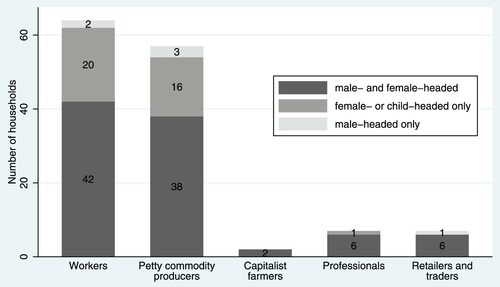

Using the labour criterion together with these adaptations to analyse the survey data, five classes are proposed: (a) ‘workers’, i.e. households that in the last 12 months spent more labour days working for others, often in casual jobs, than they used in own-account farming; (b) ‘petty commodity producers’ that work more days on their own farm than the number of workdays that they hire either in or out; (c) ‘capitalist farmers’ that employ workers for more labour days than they work on their farms themselves; (d) ‘professionals’ with access to high-skilled non-agricultural jobs and (e) ‘retailers and traders’ who depend largely on non-agricultural self-employment. presents the distribution and helps identify some key features of agrarian class relations in Rwanda.Footnote12

Figure 1. Distribution of households in sub-sample according to class grouping and household type (n = 137).

First, the majority of households (47 percent) are classified as ‘workers’. The prevalence of working households demonstrates a high degree of dependence on rural labour markets and the limitations of own-account farming for social reproduction. Although 42 percent of households are classified as ‘petty commodity producers’, most of these households participate to some degree in labour or output markets. Subsistence farming, in the strict sense, is thus truly the exception.

The sub-sample includes two households in the class of ‘capitalist farmers’. Corporate-owned estates and washing station owners can also be counted as agrarian capital but will not be picked up in a household survey. Interviews with representatives from estates and washing stations were therefore carried out separately and have informed our analysis.

The small number of ‘capitalist farmers’ in the sample relative to ‘professionals’ and ‘retailers and traders’, suggests that there may be limits to capital accumulation in agriculture. After achieving a certain level of accumulation, households seem to diversify away from agriculture. Given the acute land scarcity in Rwanda, there appear to be fewer options to reinvest in buying land, contrary to what Kitching found among ‘capitalist farmers’ in Kenya (Citation1980).

Finally, shows the prevalence of female-headed households among the more precarious ‘workers’ and ‘petty commodity producers’. Land-poor widowed, divorced and separated women face the triple burden of production, reproduction, and discrimination in the labour market. The extent to which female-headed households manage to retain access to land is key. In addition to a loss in economic security, many women told us that they missed emotional support and felt lonely. For Françoise, this translated into feeling disempowered: ‘Normally it doesn’t affect my relationship with others but of course, I have a single-headed household, I know that I am alone. For instance, I am not in a position to start conflicts with my neighbours’.

While Patnaik’s tool provides a rough but useful quantitative approximation of class position that goes beyond traditional asset-based measures, its unidimensional character is limiting because it counts all workdays as equivalent. In contrast, a class-relational approach aims to identify the dynamic position of households within a web of (work) relations. The ensuing challenge for agrarian political economy is then to develop ways to conceptualize, observe and measure the multidimensional and dynamic nature of class relations. This requires going beyond capturing the magnitude and direction of surplus extraction to reveal also drivers, functions and power relations embedded in labour arrangements. The next section examines these questions and the resulting struggles over the fruits of labour. In so doing, it approaches classes from a relational instead of a positional perspective, thereby befitting settings with no sharp polarization.

Mechanisms of labour mobilization and their tensions

This section presents empirical findings on four key labour institutions prevalent in Nyamasheke: wage labour, kuguzanya (labour exchange), nyiragabana (sharecropping) and kuragiza (cattle-sharing). For each, we will describe the arrangement and to what extent it operates as a mechanism of surplus value extraction with different functions and temporalities attached to it, as well as inherent power relations. This helps reveal mechanisms of accumulation and exploitation, and to what extent they harbour the possibility to transform the structural position of a household.

Active rural labour markets

Nyamasheke has very dynamic labour markets. In our sample, 51 percent of households worked for wages at some point during the 12 months preceding the survey. Conversely, 15 percent of households were in a position to hire workers. Most employment in the district is agrarian in nature (72 percent of hired-out wage employment activities and 97 percent of hired-in).

Almost all agricultural work at the village level involves physically demanding manual labour. Many respondents reported lacking stamina and experiencing pain from agricultural work. In selling their labour power, workers’ bodies become instrumental to commodity relations (Mezzadri Citation2017; O’Laughlin Citation2017). In this context, and coupled with pervasive food insecurity, old age and disability are heavy impediments to work. Several respondents described a vicious circle whereby they have to demonstrate to would-be employers that they have eaten, or that they are bringing enough food for the day, to ensure that they will have the energy necessary for the task at hand. Françoise, a widow and mother of six who depends on casual wage work, recounted that sometimes employers ‘look at whether the workers brought food for lunch and those who don’t may be chased away because they won’t be able to work up to 2pm without lunch’.

Yet, the non-agricultural sector remains a crucial livelihood component, accounting for 22 percent of hired-out wage employment in our sample. About half a dozen households have formal sector jobs, the majority of which are in the public sector as teachers and nurses. The two prevailing casual non-agricultural jobs are in construction and transportation.Footnote13 Women are generally excluded from the latter jobs. This contributes to the gendered nature of labour markets in Nyamasheke because it reserves some of the best paid unskilled off-farm jobs for men, reinforcing patriarchal roles. In addition, public works employment under the Vision 2020 Umurenge Programme (VUP) is another important source of income for the poorest.

Labour markets, for agricultural work in particular, are localized and casual in nature. Of all households hiring workers, only 9 percent employ workers from outside their administrative sector, and just 18 percent of households working for wages reported any migration longer than a month. Contracting is normally orally agreed and most hiring is done on a daily basis, except for task-based activities like coffee pruning. Employment opportunities are piecemeal and strongly determined by seasonal production cycles, with most households working for a number of different employers throughout the year. Location, social networks and personal relationships are important to access employment. Several respondents mentioned costs involved in looking for a job, having to expend considerable time and energy to find work, and, after completing the task, chasing after the payment. Cash and in-kind payments fluctuate throughout the year and are higher when labour markets tighten around the coffee harvest season from late March to July. Between October and December, demand for labour power is sluggish, leaving many heavily under-employed and suffering from hunger and deprivation. Many households use up any savings or food stocks they have left and depend on the solidarity of others as well as in-kind payments for whatever work they can find.

Further, labour markets are gendered. On a global scale, women are discriminated against, among other areas, in their access to ‘decent’ jobs (Kabeer Citation2012). However, awareness of the transformative potential of women’s wage employment, especially in export-oriented sectors, is growing (Sender, Oya, and Cramer Citation2006; Van den Broeck, Swinnen, and Maertens Citation2017), although gendered discrimination and empowerment in the labour market remain hotly debated (see Krumbiegel, Maertens, and Wollni Citation2020; Razavi et al. Citation2012). Based on the overrepresentation of widowed, separated and divorced women in rural labour markets, Oya and Sender (Citation2009) explore the extent to which this opens an avenue to women’s empowerment as opposed to being a mere consequence of their marginal status. Recent studies on Rwanda have confirmed women’s unequal employment opportunities, but there are diverging accounts on the labour market participation of female-headed households (Ansoms and McKay Citation2010; Petit and Rizzo Citation2015; Bigler et al. Citation2017).

In Nyamasheke, married women are considered primarily responsible for large parts of household farming, while their husbands are often in charge of securing off-farm income. Depending on the households’ needs and the husbands’ relative success in finding wage labour, wives may look for complementary income sources. Moreover, with growing land scarcity and more female-headed households, women are further pushed into wage labour. Roughly half of all wage workers in our sample are women, although on average, they work 68 days per year as opposed to 140 days for men. In addition, not only are women in charge of most reproductive tasks in the household, but they frequently also have no choice but to bring their small children to work. A few employers invoke this to rationalize their reticence to employing women. More generally, this is used to justify women being paid less. To conclude, our data shows both the various ways in which women are discriminated against in the labour market as well as the growing reliance on women’s wage labour for production and reproduction.

A final characteristic of wage relations is the variety of means of payment reported by respondents, including payments in cash or in kind paid daily or upon completion of a specific task. The mean daily agricultural cash wage is around RWF 700 for women and RWF 750 for men.Footnote14 Coffee harvesting is usually paid around RWF 40 per kg, often providing a higher daily wage equivalent than other jobs, and the pay for coffee pruning depends on the area worked.Footnote15 Usually, workers are free to do the task-based activities alone or with others (typically with their children or spouse). Of all daily paid agricultural jobs reported in our sample, 11 percent are paid in kind (in most cases with food, typically beans, cassava or sweet potatoes).

These various payment forms have specific functions and class dimensions. On the employee side, the most food-insecure households are under daily pressure to satisfy immediate nutritional needs. They accept in-kind payment partly because they cannot afford to wait or find food to buy after work. A job paid in kind saves workers a trip to the market and diversifies the diet of poor households. This was described by Alice, a widowed returnee from the DRC: ‘When I have cassava, I can’t eat it alone [… so] I go to someone and ask if they have a job for me, so that I can weed for them and get some beans, so that I can mix them with cassava to eat’. Net hiring households tend to have more means and might be able to afford longer-term investments. In a context of unequal power relations and limited monetization, households sometimes end up combining payment forms according to the different timing of their needs (in-kind payments tend to be especially sought after in the lean season). This is exemplified in Françoise’s statement: ‘When I don’t have something to eat, I request the in-kind payment because I can't eat the money’.

Often, women with childcare duties in food-insecure households are pushed into precarious jobs that are paid in kind but tend to be more flexible in terms of working time or bringing children to work. This is reinforced by a range of patriarchal norms that tend to exclude women with childcare responsibilities from better employment opportunities such as jobs at washing stations, on commercial plantations or through the VUP scheme. Thus, precarious jobs characterized by a certain flexibility do not improve the situation of women but, on the contrary, reinforce the existing division of labour.

On the employer side, in-kind payments, much like other work arrangements discussed below, are ways of mobilizing labour power when no cash is available. However, the persistence of in-kind payments more likely reflects a lack of liquidity rather than the absence of commodification. In fact, there is a certain permutability between in-kind and cash payments. This is especially the case when households hire workers to meet time-sensitive peak demand or when they are forced to hire because they cannot work themselves (e.g. due to health impairments or old age). Without access to more resources or a larger scale of production, the only currency the latter households might have is the produce grown on their plots. Households thus hire workers for different reasons and under different sets of constraints. This is why a class-relational approach can help untangle power relations in work arrangements that are often seen as being clear-cut.

Even though employers in these localized markets often hire neighbours, kin and friends (i.e. people with whom they are in long-term personal relations), and there are instances of solidarity or paternalism, wage employment is also marked by power imbalances and struggles. Our respondents described frequent disputes about work. Because arrangements are informal and piecemeal, the terms of work such as length of the working day, intensity of work, breaks and terms of payment are all subject to negotiation and frequent sources of conflict between employers and employees. For example, Françoise had an employer that would demand workers to work extra hours and would not allow them a break for lunch:

This would lead to disagreements amongst the workers because some think that the boss is not fair and others, because they have no other choice, will just work the additional hours […] If the boss becomes aware that there is someone complaining, this person could even be threatened with losing their payment for the day.

Employers are also reported to use a wide range of disciplining measures to increase the effort extracted, such as monitoring workers closely and in some cases withholding payment, threatening to dock workers’ wages or not paying at all. In many instances, these deductions are arbitrarily imposed by the employers and hard to contest by the workers. Fidèle, a young father who works in agriculture and construction, said: ‘If you don’t work well, the employer may decide to reduce your pay. So, you behave’. Other tactics include not paying workers for the hours during which rainfall stops work.

These examples show that, given high labour supply and the relative scarcity of adequate employment opportunities, most of the power resides with the employers, and space for resistance or collective action is limited. Respondents complained that voicing demands carries the risk of repercussions and lowers the chances of rehire. Employment pressures are compounded when workers are made to compete or turn against each other, for fear of losing pay. Some workers resort to what Scott referred to as ‘weapons of the weak’ (Citation1985), such as hiding away to take breaks or boycotting bad employers. Some coffee washing stations and a large-scale plantation in our sample promote more formal contractual arrangements. These jobs are generally considered more desirable because the pay is higher.

Kuguzanya: the relative reciprocity of labour exchange

In contrast to wage employment, kuguzanya is a traditional labour exchange system involving no payment. It allows households to mobilize labour power to work on their own or sharecropped land and is frequently practised in Nyamasheke. It is usually based upon personal relationships with friends and family members. The tasks performed (typically ploughing or weeding for cassava, beans or maize) vary, but the arrangement is seen as reciprocal and fair, independent of the scale of the exchange. Kuguzanya can be practised in an individual pairing or in small groups that are typically gendered but flexible enough to allow a spouse of the opposite gender to stand in if need be. Households are often motivated to participate in these labour exchanges as a form of sustaining and strengthening communal relations. Takeuchi and Marara (Citation2007) confirm the reciprocal nature of the arrangement and argue that kuguzanya is mostly practised by poor households.

Nyiragabana: inequality in sharecropping arrangements

One of the determinant features of agrarian relations in Nyamasheke is dictated by the peculiar combination of pressure over farmland and the inconsistent availability of wage work. Land-poor households often find themselves needing to access extra land to produce food and may thus engage in a land-sharing institution, a form of sharecropping referred to as nyiragabana.Footnote16 This is an informal agreement whereby tenants farm someone else’s land, normally splitting the final output 50:50. Landowners generally provide the plot and tend not to contribute inputs or labour; they need only need be present during the harvest to ring-fence their share of the product.Footnote17 Sharecropping arrangements are regularly forged among local villagers and last as long as the respective agricultural crop cycle. Importantly, nyiragabana is practised both between wealthier and poorer households as well as between poor households, particularly between labour-poor and land-poor households. Given that tenants are usually expected to provide all inputs (mainly seeds and manure) and necessary labour power, the poorest of the poor are often not in a position to engage in these arrangements, even as tenants.

Around 11 percent of respondents in the survey engage in nyiragabana, but these tenancy agreements are especially important for land-poor households. The average area of land owned by households that are nyiragabana tenants is 0.08 ha – lower than the overall average of 0.34 ha per cultivating household. Furthermore, female and child-headed households are overrepresented as nyiragabana tenants (55 percent of all tenant households).

In many respects, nyiragabana resembles forms of sharecropping in other agrarian social formations. However, its idiosyncrasies speak volumes about the specific constraints and possibilities facing land-poor rural households in western Rwanda. Almost no household in the sample relies exclusively on nyiragabana for its reproduction, but instead sharecropping seems to complement working for wages and own-account farming: 70 percent of tenant households also do wage work. Importantly, land farmed under nyiragabana is used to produce food crops such as cassava, beans and sweet potatoes that are rarely marketed. Both landowners and tenants use this arrangement as a way to source food. Among poor households, this can be the only food they produce directly; whereas households with more land (among landowners) or more labour availability (among tenants) may use nyiragabana instead to diversify or expand their food production to cover needs at different times of the year. This seems to suggest that nyiragabana is the form taken by the specific interaction between relatively land abundant and relatively labour abundant households, but there is not necessarily a stark disparity between tenants and landowners. Tenancy arrangements are present both among those who are primarily employed by others and those who are primarily self-employed, and cases of households that have been renting land in and out in different years are not unheard of.

However, nyiragabana is far from a mutualistic arrangement: tenants decry that the proceeds of their hard work have to be split with landowners at such a punishingly high rate. In turn, landowners can change the terms of the deal in ways that are openly arbitrary.Footnote18 Tenants know that their livelihoods are on the line if they fail to deliver. Unsurprisingly, nyiragabana is often seen as an exploitative institution, in which households would not engage as tenants unless they felt compelled by need. Eveline and Jean-Pierre, a land-poor couple that combines own-account farming with sharecropping, explained that: ‘If you don’t have land, you can’t think twice. What you want is to survive, so you have to go and do it [nyiragabana]. It’s our decision, no one pushes us into that agreement’. Tenants have few options to negotiate more favourable terms, although some do attempt to grow food in inconspicuous patches of the field and hope that this can be harvested before the landowner finds out.

From the perspective of landowners, nyiragabana is a labour mobilization arrangement, with two advantages over labour hiring: there are no payments in cash or kind needed to mobilize this work, and there is no need to monitor workers since the output-sharing formula works as a disciplining mechanism. This is the case of Fabien who is a land-rich farmer. By having nyiragabana arrangements in some of his plots, the land is put to productive use without him having to hire or monitor workers. In contrast, Julienne is a widow with a disability that cannot farm the small plot that she owns. Engaging in nyiragabana is her strategy for securing food that she cannot produce herself.

Uncharacteristically for a form of sharecropping, nyiragabana does not seem to predate land rentals in this part of Rwanda. On the contrary, most of the respondents contend that land rents paid in cash were the norm until sometime in the early 2000s but that, for the most part, these have been replaced with sharecropping agreements which landowners now prefer.Footnote19 The reasons for this shift are not clear, but it could be that nyiragabana allows landowners to expand their production without having to hire workers – an expense that many simply cannot afford. It could also be that it is easier for landowners to be paid in kind as part of the sharecropping arrangement than having to chase cash payments.

This suggested transition from land rentals to sharecropping happens against the background of accelerated commodification. At first sight this could seem counter-intuitive, but as households become more deeply integrated into markets (for labour power, coffee, inputs etc.) their social reproduction also changes. It could be argued that their participation in labour markets and their demand for traded goods and services is predicated, or made possible, by their own production of the means of subsistence. In this sense sharecropping is not the negation, or the opposite, of market relations but, on the contrary, a condition for the participation of households in markets – akin to the role of marginal own-account farming but necessitated by lack of access to sufficient land. The idea that nyiragabana and working for wages are complementary rather than opposite is further supported by the different time horizons in which these two livelihood activities are embedded. Entering a nyiragabana arrangement as a tenant means signing up for months of agricultural labour against a distant mid-term goal of harvesting food; in contrast, people set out to find wage work with the hope of returning home in the afternoon with cash or food to cover daily needs.

At a fundamental level, nyiragabana leverages a class difference between landowners and land-poor households to facilitate the appropriation of the fruits of labour by landowners, showing how ownership of the means of production and labour relations interact.

Kuragiza: cattle-sharing as a longer-term investment

Another form of surplus labour mobilization is called kuragiza, a cattle-sharing institution.Footnote20 Similar to sharecropping for land, households can access livestock through kuragiza. Much like nyiragabana, in a kuragiza agreement animals – cows mainly, but sometimes goats or pigs – owned by a ‘giver’ are reared by a ‘receiver’. All offspring born during the period of the arrangement are assigned to ‘giver’ and ‘receiver’ in turns. When the animal subject to the kuragiza arrangement is sold, the ‘giver’ is reimbursed for the initial investment and for veterinary expenses incurred; any remainder (and often the milk produced) is split 50:50. Like sharecropping, cattle-sharing is a labour mobilization institution whereby the profit-sharing formula works as a disciplining mechanism. By making all gains to the ‘receiver’ contingent upon taking good care of the cow and effective only after selling it, the ‘giver’ has no need to monitor the work done by the ‘receiver’ and can rest assured in the certainty of profit. There is also a barrier to entry as ‘receivers’ have to be seen as trustworthy and able to provide fodder and shelter for the animal.Footnote21 Cattle are not primarily reared for food, but instead as a savings deposit for emergencies. In that vein, engaging in kuragiza is meant as a financial investment, unlike sharecropping which is meant to produce food. Additionally, cattle produce manure, a coveted by-product for cash-strapped farmers with no access to chemical fertilizers. Thus, kuragiza entails for ‘receivers’ a combination of a long-term investment with the potential of using manure to improve agricultural productivity and milk for own consumption. For ‘givers’, it is an interest-yielding reinvestment opportunity.

In the contrast between nyiragabana and kuragiza we encounter two output-sharing arrangements with different time horizons and trade-offs between use- and exchange-value. First, harvested food crops introduce a time imperative: work is demanding and concentrated in peak labour times. There is a narrow window of time in which food must be harvested. Tenants are subjected to this rigid temporality although they can only retain 50 percent of the product. In contrast, cattle-sharing (kuragiza) is not seasonal and cattle can be sold at any point in time – although ‘givers’ usually decide when to sell, because they are in the position of power. Other than manure, kuragiza ‘receivers’ hold cattle to acquire livestock or invest. These two agreements therefore have different class dimensions: in sharecropping, the surplus labour of tenants is squarely appropriated by landowners, whereas through kuragiza, ‘receivers’ are invested in a process that will allow them to one day own their own means of production. While kuragiza is seen as a less exploitative arrangement than nyiragabana, in both cases relations between tenants and landowners, or between cattle ‘givers’ and ‘receivers’, show a tense struggle over the division of labour between the owners of the means of production and those who work.Footnote22

Class relations in Nyamasheke

We have argued that analysing classes as positions is insufficient to understand the dynamism and diversity inherent in the relations among and between them. Instead, the previous section has taken a relational approach to explore the drivers, functions and power relations underlying different labour encounters that mediate class relations. From this discussion, two insights emerge: first, that relations are shaped by the different time scales that households experience, and second, that subsistence is now fully commodified. These themes cut across different labour arrangements and class positions in Nyamasheke and would be obscured by focusing on class positions alone. As the next section will explain, questions of temporality and commodification apply in most rural settings but how they affect social reproduction is an empirical question worth answering on a case-by-case basis.

Time and markets as intermediary dimensions of class relations

An important dimension of agrarian relations has to do with the different temporal scales that households encounter in their livelihood patchworks. By this we mean that there is a tension between work arrangements based on longer production horizons (typically employers) and households that find themselves at times in shorter reproduction cycles (casual workers, day labourers). At different times, households may have the ability to wait for a harvest or for the delayed payment of a trader, while in other instances their urgency is to ensure that their household has food to eat at the end of the working day. These sets of pressures are expressed in the work relation and provide the conditions for surplus extraction or appropriation.

Demand for jobs, although mostly affected by the seasonality of the coffee harvest, operates at the daily scale. For many poorer households, a day of work translates into food payments that are consumed on the day or cash revenue that is used to meet basic needs, leaving little room for investments or savings. There are nevertheless important differences: households that are dependent on a multiplicity of fragile and casual arrangements face great uncertainties that limit longer-term planning. In contrast, other households manage to gain more stable access to wage employment, often through long-standing personal relationships with employers. Even though they might not be able to accumulate, their position is somewhat less precarious.

Own-account farming and sharecropping arrangements are subject to annual cycles. On the one hand, the more households are able to cultivate, the more their subsistence provides security against shocks and against the vagaries of the labour market. On the other hand, this should not distract from the big risks in terms of yield fluctuations and harvest failures inherent in agricultural production.Footnote23 Nature dictates much of the cultivators’ time scale. As a result, seasonal pressures and the need for complementary income earned through wage employment apply to most households. Moreover, at a generational scale, class relations are contingent upon life-cycle events such as the influx of bridewealth, the mobilization of labour through marriage, health impairments and old age, return from exile or widowhood.

Throughout all temporal scales, class intersects with other social markers such as gender and location, making classes fragmented and internally differentiated. The resulting personal networks play an important role and can provide crucial support in times of crisis through various, albeit irregular, non-market mechanisms.

Time matters differently for different groups involved in production. In a sense, the differential pressures of timing become another arena of struggle. These pressures may be imposed by natural cycles or market demands beyond the control of producers and workers. But differences in the pressures imposed by timing also sustain surplus extraction in a variety of ways. Those with long time horizons can impose work conditions on those under more pressure; employers extend the working day or delay payments as ways of disciplining workers or transferring onto them the pressures of lacking liquidity and the risks of production. Workers similarly face time as an objective materiality, but differently, in accordance with their reproduction needs and the temporal scales of the work arrangements they find. Yet again, they can leverage time as a medium of reproduction by combining varying time horizons in their struggles to survive or transform their fortunes. Some combinations reveal certain households’ flexibility and capacity to mix strategies opportunistically, such as when more stable employment enables households to invest in coffee production. In other cases, households are coerced into different combinations out of desperation or the drudgery of survival. The story of Hélène, the widow that grows some of her own food but is required to sharecrop and take up additional wage employment to ensure her survival, is a case in point.

The second theme captures the implications in Rwanda of a completed process of commodification. There are a number of basic necessities that most households are not able to produce themselves, such as tin roofs or tools, and other goods and services that can only be paid for with cash, such as education, health insurance and bridewealth. Households who have access to some cash, even if only sporadically, through sales of produce or from wage employment can reproduce themselves more comfortably. Some households that lack secure and constant access to cash income cannot afford to work in more regular jobs with bi-weekly or monthly payments because they cannot wait so long to be paid and thus find themselves churning between more irregular, but more promptly paid, work opportunities. While most produce some food on their own, many are food-insecure and depend on payments and exchanges, including gifts, bartering or sharecropping to complement their diets. Even some of the households who can afford to hire a few workers for a couple of days are cash-strapped, especially before coffee sales materialize, and can only pay in kind.

By relating this to our previous discussion on time scales, we can now compare the different functions of nyiragabana, kuragiza and wage work in kind and cash along time horizons and with regard to commodity relations. summarizes the different temporalities in which these arrangements operate and the needs they satisfy.

Table 2. Work relations according to needs and time horizon.

As shown above, both nyiragabana and kuragiza involve a risk transfer onto the weaker party who is responsible for, respectively, the crop production and the cattle rearing. The two arrangements serve, however, different purposes. Nyiragabana, much like work paid in kind, prioritizes food provision and thus use value, whereas kuragiza and work paid in cash produce primarily exchange value. Very few households are to be found exclusively in one of these work relations (work paid in kind, work paid in cash, nyiragabana or kuragiza) as most combine elements of them.

Although the literature has convincingly argued that, with few exceptions, the commodification of subsistence ran on par with the world historical consolidation of capitalism (Bernstein Citation2010), there remains an influential current in agrarian studies that stresses, in contrast, autonomy and self-sufficiency as a possible alternative (Rosset and Altieri Citation2017). The Nyamasheke case is useful to examine in light of this debate. Prima facie, there are characteristics of production and livelihoods that would suggest that commodification involves social relations of production only partially and that people in Nyamasheke participate in markets only opportunistically. For example, most respondents reported problems of liquidity and being continuously cash-strapped; there is an important contribution to household reproduction by goods and services produced domestically and not traded in markets; and there is evidence of many instances in which work is paid for in kind. However, it is argued here that these constitute, on the contrary, evidence of the advanced commodification of subsistence, meaning that social reproduction entails the mediation of markets. Respondents and people in the region, by extension, can no longer sustain themselves meaningfully with what they produce alone, and a large share of households do not have the means to produce any food. Markets, however informal and vernacular, are not only necessary for basic consumer goods, but also needed to ensure household reproduction and accumulation. The commodification of subsistence creates the compulsion that makes people available for work and, frequently, more likely to be exploited the more their subsistence depends on this labour encounter. Commodification also provides those seeking to employ someone with pools of people in need of work. More specific to the Nyamasheke case, but likely applicable to other settings, commodification contributes to the emergence of an extremely dense network of work arrangements that are central for enabling production at the aggregate level (notably coffee exports) and livelihoods for most households, while neither leading to the emergence of stable wage employment nor serving as the foundation of an established or single class identity.

Churning at the bottom: relentless micro-capitalism and the limits of polarity

This begs the question on what level the households in our sample are able to reproduce themselves as a result of these different pressures, i.e. to what extent work relations reinforce or have the power to change a household’s circumstances. The often piecemeal livelihood patchworks worked out ingeniously by many households under intense commodification pressures or employment uncertainty offer limited potential for accumulation, leaving many households subject to what Bernstein (Citation2010, 104) calls a ‘simple reproduction squeeze’. Moreover, the reproductive value of most wage employment is so low that the survival of many households depends on their ability to multiply these precarious engagements. This is what we mean by ‘churning at the bottom’ – a sense of powerlessness experienced by those in precarious livelihoods.

There are two related aspects to these dynamics in Nyamasheke that make a class-relational analysis indispensable. On the one hand, while it may seem from afar like there is a relatively homogenous, albeit poor, peasantry, closer inspection reveals a multitude of differentiated labour encounters. This exemplifies what Davis has called ‘relentless micro-capitalism’, i.e. localized systems of accumulation and exploitation – a typical feature of informal economies characterized by petty exploitation and growing inequalities (Citation2006, 181). In Nyamasheke and many other rural settings of the Global South, high levels of instability and fluidity in work arrangements result in some household members simultaneously taking on the role of exploiter and exploited in different relations, in what have been called systems of nested or recursive exploitation (Pérez Niño Citation2014). Importantly, acknowledging fluidity does not mean that class positions are meaningless or random like a game of musical chairs. The plurality of different work arrangements does not amount to a mere combination of livelihood strategies but is the consequence of being under a range of temporal and commodification pressures. What we want to stress here is not diversity per se but how these different work arrangements are part of a topography of uneven power relations. As a result, localized patterns of micro-capitalism leave their mark on communities, shaping inter-household relations, even in contexts of no sharp local polarization.

The study of class relations, even where quantitative differences between classes may be minute, is therefore indispensable to understanding production relations in a place like Nyamasheke. Production and reproduction in agrarian formations rely on the mobilization of labour power that exploits these very class differences. Such manifestations of class relations reveal how capitalism works at a local scale because they permeate social relations. While these differences appear small from afar, they are consequential: in a context of high precarity, they shape life experiences and the scope of action of the people of Nyamasheke. To the extent that these differences are experienced as being prominent, they could help explain the limitations of the emergence of broader identities and forms of collective mobilization.

Concluding remarks

This paper offered two ways of approaching class dynamics in Nyamasheke, the main coffee producing region of Rwanda, first analysing the groupings that form when households are classified in relation to their use of labour power and then contrasting different forms of labour mobilization to reveal power differences among participating households. In the first instance, the labour-centric approach allowed us to propose a class structure for Nyamasheke where, at its simplest, net sellers of labour power and net buyers of labour power are in the extremes and households that apply most of their labour power to their own production are in the middle. Our second avenue of analysis, the study of the quality and functions of different forms of labour mobilization among households, brought to the fore another set of considerations: it showed in a less discrete and more relational way that the labour relations underlying productive activities in the region invariably involve sets of households in different power positions vis-a-vis each other. Production therefore relies on the leveraging of class differences and varying degrees of surplus value extraction.

These power imbalances are not always the automatic consequence of some households owning the means of production and mobilizing the labour of households that do not (such polarity is largely exceptional in Nyamasheke). Instead, they are the way that less dramatic differences between households are experienced and mobilized in production, in conjunction with a set of pressures and tensions in social reproduction that households specifically experience. Here we referred for instance to how one household’s relative pressure to find food or cash for their own subsistence becomes an opportunity for accumulation for another household, frequently one that is more secure in their access to food and cash. Therefore, while the first approach (the class structure approach built on quantitative differences in the use of labour power) demonstrated that power differentials between groups exist; the second approach (focusing on the quality of labour relations) demonstrated that these power differentials do not take a single form, but are expressed and experienced in different ways. Studying class and inequality at the micro-level and in the absence of strong overall differentiation may seem daunting, but it is all the more important because, at the margins, these differences can have far-reaching consequences.

We have shown how, despite relatively limited monetization and the high prevalence of own-account farming, subsistence in Nyamasheke has been thoroughly commodified. Examples of the market pressures discussed above include among others: (i) the turn-around in terms of work arrangements which in some cases postpone payments until the end of the productive cycle, thus forcing many to engage in piecemeal work paid on a daily basis to support immediate food consumption needs; and (ii) the way in which households participate in different markets as required by their social reproduction, in some cases buying agricultural inputs and tools and in others paying for school uniforms and mandatory health insurance. Temporality and commodification thus shape households’ reproductive strategies. These themes will also be relevant in other rural settings.

In Nyamasheke, coffee production engenders crucial direct and indirect spillovers, notably via dynamic local labour markets, and provides an avenue of accumulation for some. Despite the dynamism of the Rwandan coffee sector, small farmers have limited room for accumulation in agriculture. This pushes most households to engage in a variety of precarious small-scale work arrangements subject to strong seasonal pressures and different time scales. Policy measures to tighten labour markets and better accommodate the needs of female-headed households could make an important contribution.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff at the Alliance of Bioversity International and International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Rwanda for facilitating and hosting our research in Rwanda. We would also like to express our greatest thanks to the invaluable research assistance and interpretation of Rénovat Muhire and Mukamana Theonille as well as to the enumerator team. Thanks also go to Yannik Friedli for significant support in transcribing the interviews. We are grateful to Prof. Catharine Newbury for providing substantial comments on an earlier draft. We would like to also acknowledge two anonymous reviewers for a close reading of the manuscript and their thoughtful suggestions for improvement. Finally, we sincerely thank all our research participants for offering their time and sharing their stories with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Patrick Illien is a PhD Candidate in Geography and Sustainable Development at the University of Bern. He has undertaken mixed-methods fieldwork in Laos and Rwanda investigating the political economy of agrarian change. Patrick is particularly interested in the relationship between economic growth, labour market dynamics and poverty. He holds an MSc degree in Violence, Conflict and Development from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London.

Helena Pérez Niño is a Lecturer in Political Economy of Development at the Centre for Development Studies, University of Cambridge. She received her PhD from SOAS University of London with a dissertation on the social relations of production in export agriculture in the Mozambique-Malawi borderland. Helena was an ESRC postdoctoral fellow; a research fellow at the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) in the University of Western Cape in South Africa as well as a visiting researcher at the Institute of Social and Economic Studies (IESE) in Mozambique.

Sabin Bieri is Director of the Centre for Development and Environment at the University of Bern. A social geographer by training, she oversees research and teaching on the social and economic dimensions of sustainability, thereby specializing in questions of work, globalization and inequality. She is the leading investigator of the FATE project, a cross-case study on agricultural commoditization and rural labour markets in four countries on three continents. She received her PhD from the University of Bern, where she was an awarded member of the Graduate School in Gender Studies.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These interventions have received considerable attention, specifically regarding entry barriers, opportunities and differentiated impacts (Ansoms Citation2008; Ansoms et al. Citation2018; Huggins Citation2017). Dawson, Martin, and Sikor (Citation2016) argue that these policies have heightened food insecurity and inequality in western Rwanda by dismantling traditional agricultural systems and privileging wealthier households. These findings are corroborated by Cioffo, Ansoms, and Murison (Citation2016) using data from Northern Province.

2 Oya (Citation2013) shows how rural labour markets have been notoriously underreported in much of sub-Saharan Africa; Van den Broeck and Kilic (Citation2019) provide evidence of widespread rural off-farm employment across a range of African countries using national panel household surveys; and Oya and Pontara (Citation2015a) present a selection of case studies that underline the diversity and dynamism of rural wage employment.

3 Although female-headed households represent only 30 percent of our sample, we decided that half of our interviewees would be from these households to explore the gendered dynamics of production and reproduction. This is done in the context of work by Newbury and Baldwin (Citation2000), Koster (Citation2010) and Carter (Citation2018) that debates whether female-headed households, many including women that became widowed in the war, are especially vulnerable in Rwanda.

4 Food insecurity is measured using the World Food Programme’s CARI (Consolidated Approach for Reporting Indicators of Food Security) approach: ‘a method that combines a suite of food security indicators, including the household’s current status of food consumption (food consumption score) and its coping capacity (food expenditure share and livelihood coping strategies) into a summary indicator – the Food Security Index (FSI)’ (WFP Citation2018, 17).

5 Our figure refers to operational holdings and excludes households with no farming land, while Erlebach does not specify if these households are included in the calculation. The much lower numbers reported by Erlebach and ourselves indicate strong local pressures over land and are partially due differences in survey design that in our case is more sensitive to land-poor households.

6 Most are informal loans from village saving groups or local social networks (e.g. employers, local power holders, acquaintances or family members), only few of which are invested in production. There are also more formal loans from cooperatives that lend to their members and from banks that can play an important role, notably for better-off households.

7 All names were changed to protect the respondents’ identities.

8 Even households that neither grow coffee nor work on coffee farms can find themselves renting land from, or indebted to, coffee farmers.

9 Oya (Citation2015b) proceeds similarly to distinguish between ‘classes of labour’ and ‘classes of capital’ in Mauritania, although without referring explicitly to Patnaik’s index. Most attempts to identify socio-economic groups in rural Rwanda are instead based on participatory poverty assessment exercises which consider a range of dimensions such as food security, education, land holdings and work. This usually results in six groups (see Ingelaere Citation2007; Ansoms Citation2010) corresponding to the ubudehe classification scheme used in Rwanda to identify beneficiaries of social protection programmes. In 2015, the categories were condensed to four groups (Ezeanya-Esiobu Citation2017). Such approaches to socio-economic differentiation vary from our labour-centred method. They provide locally grounded descriptions but conflate a household’s integration into the relations of production with associated markers of wealth and well-being.

10 A variant also used by Crow (Citation2001) and Nagalia (Citation2018).

11 In the absence of a direct measurement, we estimated the days worked by a household on their own farm and in a sharecropping/rented plot by attributing the total number of days worked proportionally to the area of the household farm and area used in sharecropping/rented land (we thank Utsa Patnaik for this suggestion). For leased out land (in only four cases of the sub-sample used for this analysis, see footnote 12), where we lacked the corresponding data of the household using that land, we imputed the median labour days per square metre used on land leased in our calculations.

12 We only included households with complete information and excluded inconsistent cases to increase the accuracy and validity of our analysis. Problematic cases with inconsistent key variables, e.g. a household reporting a large production volume but no work input by anybody from the household or outside, were thus excluded. This substantially reduced our sample size from 233 to 137. Therefore, statistics related to the groupings based on our labour index have only been calculated on this sub-sample. While the differences in land ownership and operational holding between the two samples are not statistically significant, the excluded households reported substantially fewer labour days of any kind. This makes sense given that data for these cases was incomplete or inconsistent and indicates underreporting (however, elder and people with disabilities who no longer engage in many work arrangements are also found in this group).

13 Two of our eight villages have lake access and include households for whom fishing is a key activity.

14 This discrepancy increases to about RWF 700 and RWF 900 respectively if the non-agricultural sector is included. Bigler et al. (Citation2017) find a similar wage gap in Northern Province.

15 Respondents harvest about 20–25 kg per day but can surpass this if the conditions allow as they have an incentive to work fast.

16 Few scholars have studied contemporary sharecropping arrangements in Rwanda. Takeuchi and Marara (Citation2007) refer to sharecropping as urutéerane, while Ansoms (Citation2009) briefly describes a similar institution called ikibara in Southern Province. This research gap is surprising given that around 15 percent of households in Rwanda cultivate sharecropped parcels (NISR Citation2018b).

17 At times, landowners may supply seeds or manure as well.

18 The timing of harvesting is often contentious: hungry tenants may be desperate to harvest while landowners may prefer to allow the tuber to mature further. According to Hélène: ‘If the landlord doesn’t want to harvest, then [the tenants] will sleep hungry. Although they have the products, that landlord doesn't want to harvest at that time’.

19 This is similar to the observations of Takeuchi and Marara (Citation2007, 112) who note: ‘No previous research has discussed sharecropping in Rwanda. Sharecropping in western Rwanda appears to be a relatively new practice that emerged after the civil war in the 1990s’.

20 Kuragiza is somewhat different from the historically important ubuhake cattle clientship, not least because the time period of the arrangement can be shorter, and because kuragiza usually involves less responsibilities and no longer relies on access to pasture (we thank Prof. Catharine Newbury for this point).

21 In our research areas, open grazing is generally not allowed and cattle have to be kept in sheds.

22 Nyiragabana and kuragiza may thus be characterized as wage employment in disguise following Oya and Pontara (Citation2015b).

23 The practice of kwotsa imyaka, whereby farmers sell part of their harvest prematurely at much lower prices, exemplifies the temporal and commodification pressures they experience (C. Newbury Citation1992).

References

- Ansoms, An. 2008. “Striving for Growth, Bypassing the Poor? A Critical Review of Rwanda’s Rural Sector Policies.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 46 (01). doi:10.1017/S0022278X07003059.

- Ansoms, An. 2009. “Faces of Rural Poverty in Contemporary Rwanda: Linking Livelihood Profiles and Institutional Processes.” PhD diss., Université d’Anvers. https://dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/object/boreal:117961.

- Ansoms, An. 2010. “Views from Below on the Pro-Poor Growth Challenge: The Case of Rural Rwanda.” African Studies Review 53 (02): 97–123. doi:10.1353/arw.2010.0037.

- Ansoms, An, Giuseppe Cioffo, Neil Dawson, Sam Desiere, Chris Huggins, Margot Leegwater, Jude Murison, Aymar Nyenyezi Bisoka, Johanna Treidl, and Julie Van Damme. 2018. “The Rwandan Agrarian and Land Sector Modernisation: Confronting Macro Performance with Lived Experiences on the Ground.” Review of African Political Economy 45 (157): 408–431. doi:10.1080/03056244.2018.1497590.

- Ansoms, An, and Andrew McKay. 2010. “A Quantitative Analysis of Poverty and Livelihood Profiles: The Case of Rural Rwanda.” Food Policy 35 (6): 584–598. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.06.006.

- Bayisenge, Jeannette. 2018. “From Male to Joint Land Ownership: Women’s Experiences of the Land Tenure Reform Programme in Rwanda.” Journal of Agrarian Change 18 (3): 588–605. doi:10.1111/joac.12257.

- Bernstein, Henry. 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Agrarian Change and Peasant Studies Series. Halifax and Winnipeg: Sterling, VA: Fernwood Pub. : Kumarian Press.

- Bigler, Christine, Michèle Amacker, Chantal Ingabire, and Eliud Birachi. 2017. “Rwanda’s Gendered Agricultural Transformation: A Mixed-Method Study on the Rural Labour Market, Wage Gap and Care Penalty.” Women’s Studies International Forum 64: 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2017.08.004.

- Bigler, Christine, Michèle Amacker, Chantal Ingabire, and Eliud Birachi. 2019. “A View of the Transformation of Rwanda’s Highland through the Lens of Gender: A Mixed-Method Study about Unequal Dependents on a Mountain System and their Well-Being.” Journal of Rural Studies 69 (July): 145–155. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.05.001.

- Campling, Liam, Satoshi Miyamura, Jonathan Pattenden, and Benjamin Selwyn. 2016. “Class Dynamics of Development: A Methodological Note.” Third World Quarterly 37 (10): 1745–1767. doi:10.1080/01436597.2016.1200440.

- Carter, Becky. 2018. Linkages Between Poverty, Inequality and Exclusion in Rwanda. K4D Helpdesk Report. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/14189.