ABSTRACT

This paper explores how the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP), as an example of contemporary bottom-up development practices in the global South, governs nomadic pastoralists in the peripheries. Based on fieldwork in Ethiopia's Somali region, we show that PSNP practices of client targeting, community-based public works and (international) financial resource flows, both for their own sake and because of their entanglement with the sedentary metaphysics of Ethiopian state, have advanced sedentary governmental order into pastoral peripheries more than top-down state sedentarization interventions had ever done. Finally, we argue that bottom-up development practice is an effective tool for state-building in the periphery.

Introduction

The ‘doom and gloom’ view of African pastoralists as marginalized, impoverished, vulnerable to climate change and ill-adapted to modern services and production networks has become a dominant narrative, attracting the attention of state and non-state development actors (Little et al. Citation2008; Scoones Citation1995). The identification of pastoral problems and the framing of solutions coemerge within a specific development regime of states, such as the Ethiopian state, whose very highland, settled crop-farming identity, as Catley, Lind, and Scoones (Citation2013) note, often puts it in opposition to nomadic pastoral practices. Pastoral areas of Ethiopia have recently suffered recurring droughts and acute food crises reviving the view of the Ethiopian government that nomadic pastoralism is no longer viable (Devereux Citation2010). Pastoralists, for the Ethiopian government (FDRE Citation2008, 2), are among the ‘country’s poorest and most marginalized people with the highest incidence of food insecurity’. Pastoral areas of Ethiopia are characterized by the lowest development indicators with respect to health, education and infrastructure (FDRE Citation2008).

Hence, pastoral areas have attracted the attention of Ethiopian policy makers and NGOs/donors. The rationalities and practices of pastoral development of the Ethiopian state are, however, still based on a stereotypical representation of pastoralism as ‘backward’ and unviable, locating the causes of poverty and food insecurity within nomadic pastoralism itself (Beyene and Korf Citation2012; Hogg Citation1992). Nomadic pastoralism is viewed as an obstacle to Ethiopian government’s pursuit of modernity for which sedentarization is deemed a precondition (Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015). This explains the sedentary metaphysics of the Ethiopian state in which sedentary lifestyles and livelihood practices are taken for granted as the ‘right’ paths toward modernity and development. They are positioned as the only way in which the wellbeing of pastoralists can be secured, and structure the discursive and practical orientations of bureaucrats and technocrats working on (pastoral) development.

A radical transformation of pastoralists and their livelihoods is rationalized such that ‘the civilizing mission of development thus becomes associated with settlement projects, irrigation schemes and the provision of ‘modern’ services’ (Catley, Lind, and Scoones Citation2013, 11). Such pastoral ‘civilizing’ projects have been implemented by successive Ethiopian regimes (Regassa, Hizekiel, and Korf Citation2019; Regassa and Korf Citation2018). They have much in common with Scott’s (Citation1998) ‘high-modernist’ development schemes which are state-led and top-down (Mosley and Watson Citation2016) that seek to impose state schemes over pastoral peripheries. While pastoralists have alternative rationalities and strategies based on nomadic pastoralism and a mobile lifestyle and always resist the imposition of state-planned development schemes (Mosley and Watson Citation2016), these schemes, mainly focused on sedentarization, have remained unsuccessful (Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015). It is at this juncture, that a new, so-called bottom-up development scheme called Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) has been implemented.

The focus of our analysis is on how the rationales and approaches of PSNP have been translated into practice. The paper is neither an analysis of the rationale of PSNP nor an evaluation of the programme’s success. Drawing on PSNP implementation in Ethiopia’s Somali pastoral periphery, our aim is to explore how contemporary bottom-up development programmes work on-the-ground. We show that PSNP practices and technologies, both for their own sake and because of their entanglement with the sedentary metaphysics of Ethiopian state, enhance the trend towards sedentarization in the pastoral peripheries more than the Ethiopian state had ever achieved in the past. We demonstrate this by analysing the three aspects of PSNP practices: targeting, community-based public work and financial resource flows.

PSNP and pastoralists

In 2005, the government of Ethiopia launched PSNP for 5 million chronically food insecure farming highlanders (FDRE Citation2006). Financed by a harmonized multi-donor trust fund, PSNP is the largest social protection programme in sub-Saharan Africa in terms of both financing and number of beneficiaries (Pankhurst and Rahmato Citation2013). PSNP was launched in pastoral areas in 2008 raising the number of beneficiaries to 8.3 million (FDRE Citation2016).

PSNP differs from the state-led, top-down development schemes presented above in its design, goals and approach. PSNP is multidimensional, holistic, and programme-based. Its goal is expansive: improving the overall condition of people in an integrated manner. Its approach is participatory and community-based. In general, PSNP is claimed to be a bottom-up development scheme. In view of PSNP as a (in Foucault’s sense) governmental intervention, the bottom-up development (programme) we allude to here is a development programme designed by governments or non-government development agencies while planning for and implementation (of its sub-projects) are guided by the conditions, interests and participation of local communities. It does not necessarily mean that it is an intervention exclusively designed and practiced within and by local communities.

The key component of PSNP is ‘public work’ – in which most beneficiaries participate and much of the budget is allocated – that constitutes community-based activities, such as rangeland management, water point development and construction of infrastructures, in which pastoralists participate as a source of employment (FDRE Citation2012). The aim is to provide conditional food and cash as a wage for pastoralists so that they can meet their consumption needs in the short-term while they simultaneously enhance the communal resource base in the long-term (FDRE Citation2006). The other component is ‘direct support’ that constitutes unconditional food and cash transfers for households who are unable to participate in public work. The PSNP implementation manual (FDRE Citation2010, 6) reads as follows:

PSNP … not only includes a commitment to providing a safety net that protects food consumption and household assets, but it is also expected to address some of the underlying causes of food insecurity and to contribute to economic growth in its own right. The productive element comes from infrastructure and improved natural resources base created through PSNP Public Works … The PSNP is not a project but a key element of local development planning.

The implementation of PSNP needs to be based on local realities and interests (FDRE Citation2012). Its latest implementation manual (FDRE Citation2016, Chapter 9, 20) reads ‘public work subprojects and livelihoods interventions will take into account the differing agro-ecological and sociocultural characteristics in pastoral lowlands’. In pastoral areas, because of the lack of clearly defined boundaries that is typical of communities in more sedentary areas and because of seasonal mobility of household members across villages, the kebeleFootnote1 is identified as an ‘appropriate’ unit of intervention (FDRE Citation2012). A representative community committee must be formed to organize client targeting, and the process should be participatory in which community members should be involved (FDRE Citation2016). ‘[The] community participates in the identification, planning, monitoring and evaluation of public work sub-projects to ensure public works are tailored to the prevailing livelihood in the area’ (FDRE Citation2016, Chapter 8, 2). Implementation is backed by manuals which do not offer sedentarization as a component of the PSNP strategy.

The fieldwork methodology and process

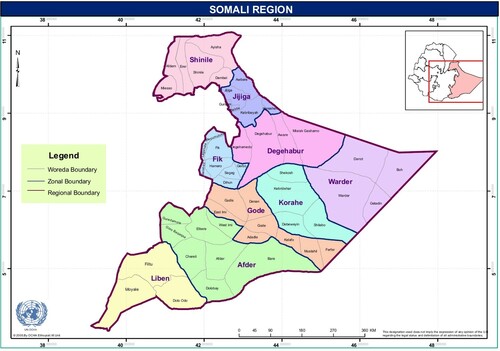

The paper is based on 12 months of fieldwork from 2017/2018 in three pastoralist sub-kebeles, namely Qurenjale, Dhaladu, and Gobanti, together forming one kebele administration called Gobley in the semi-arid Afdem woredaFootnote2 of Ethiopia’s Somali region (). We selected Gobley kebele based on accessibility and because it meets the topical criteria of the co-existence of nomadic pastoralism and PSNP. We targeted all the three sub-kebeles because, on the one hand, the geographical and social (clan relation) boundaries among them are blurred to the extent that pastoralists continuously moved their dwellings between sub-kebeles, while some key PSNP-related bureaucratic decisions are made at the kebele level on the other hand. The population of Afdem woreda belongs to the Issa clan, and according to Afdem Woreda (Citation2018), 90% of the population depends on nomadic pastoralism as a source of livelihood and way of life. While each sub-clan lineage in other parts of the Somali region claims and owns grazing land from which non-member users are mostly excluded (Beyene Citation2009), there is no separate sub-clan claim of ownership on grazing land within the larger Issa clan. There has not been noticeable state or private capital investment, or commodification of the pastoral frontier in Afdem woreda that has been common in other parts of Ethiopian pastoral lowlands and explains sedentarization (cf. Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015).

We conducted 26 unstructured in-depth interviews with PSNP beneficiary pastoralists composed of men and women, youth and elderly, and clan leaders. Eight in-depth interviews were made with bureaucrats at (sub-)kebele, woreda and region levels, selected because of their roles in PSNP implementation. One intensive focus group discussion was held with a group of pastoral clan leaders and elders. While all interviews with pastoralists (including (sub-)kebele officials) were made in Somali language with the help of a translator, interviews with the woreda and regional bureaucrats were made in Amharic without translator. We conducted participant observation in formal and informal meetings, PSNP retargeting and public works. A significant amount of research material was collected through informal interactions and conversations, such as gossips, rumours, everyday talks and pastoralists’ metaphors, all the way from the villages (e.g. with village schoolteachers who speak Amharic) to the town of Afdem.

The political sensitivity of our research emerged early during our fieldwork. Pastoralists were suspicious of us to be government spies. They invoked the metaphor ‘Sirta Dawlada Iyo Isha Qudhaanjada lama carko’ (meaning ‘government’s secrets and the eyes of a sugar ant are not visible’ in Somali) upon which they frame their relations to the government in general, and us in particular. While this was considered as part of our research rather than a challenge, the researcher-pastoralists relation gradually improved with assistance from an insider research assistant/translator who also worked as a village schoolteacher and through the recruitment of a facilitator from the communities themselves. Some key government actors at the regional and woreda government levels directly and indirectly rejected requests for interviews. However, surprisingly most of those interviewed were not shy to speak about PSNP and sedentarization as they believe that they are doing strategically important work in the service of pastoralists themselves.

Theoretical framework: governmentality and (bottom-up) development

Governmentality is succinctly defined as the ‘conduct of conduct’ in which power is exercised to shape human conduct towards some ‘ideal’ standards by some calculated means (Foucault Citation1991). Modern government is concerned with optimizing the well-being of populations at large and to direct them to be more productive through the use of tactics other than coercive state apparatuses or law (Foucault Citation1991). The aim is not to dominate people, but to improve their condition (Li Citation2007). To this end, government is expansive and intervenes in, citizens’ means of subsistence, their territory, resources, habits, customs, ways of thinking and acting, misfortunes and relations involved to adjust them in beneficial ways (Foucault Citation1991). Government operates through ‘a multiplicity of authorities and agencies in and outside of the state and at a variety of spatial levels’ (Watts Citation2003, 13).

Government is constituted by three dimensions: governmental rationalities, subjectification and technologies of government. Governmental rationalities draw upon formal bodies of knowledge and expertise to justify the activity of governing subjects (Dean Citation2010). Subjectification is about the (re)production of governable subjects (Dean Citation2010). Individuals or population are made subjects (selves, actors or agents) in relation to, among others, their modes of production and lifestyles, for example, nomadic pastoralism versus settled crop-farming.

Technologies of government refer to the assemblages of procedures, instruments, techniques, devices, resources, dossiers, mundane practices and so forth through which governmental rationalities are translated into concrete governmental practices (Dean Citation2010). Government is spatialized through its technologies to produce real and material governable spaces and subjects. The scales at which this happens are myriad and include the community, village, the region or nation (Watts Citation2003). Governmental technologies are the main focus of empirical research, like this one, to understand how people govern and are governed practically and in real by governmental interventions, such as PSNP.

The actual implementation and outcomes of governmental technologies are, however, shaped by a complex social fabric, specific national development discourse, such as the Ethiopian (anti-)pastoral development discourse and practices, and even by the processes and subjects they seek to govern (Li Citation2007). Governmental technologies are negotiated on the ground given the ability of subjects to think and act otherwise (Li Citation2007), the disregarding of which has been the usual criticism directed at the governmentality approach (McKee Citation2009). Foucault himself was, however, against top-down singular models of power and indeed acknowledged human agency (McKee Citation2009) though the agency of the governed cannot be viewed as outside power relations which are unequal and hierarchical (Dean Citation2010). Agency of the governed is also implied by the capacity to process social experiences, negotiate (including compromises) and devise ways of coping with hegemonic power even under structural constraints. Contemporary governmental practices, on the other hand, depend upon the formation of certain types of subjects and actors, such as pastoralists and their organizations (clan leaders), endowed with agency and the creation of conditions within which they act, so that government might be effective (Dean Citation2010).

Government, as conceptualised here, has been exercised in much of the global South through contemporary (bottom-up) development practices, and in turn has attracted a lot of scholarly attention (cf. Li Citation1999, Citation2007; Watts Citation2003). Development practices structure the possible field of action of others (the poor) through a variety of technologies and micropolitics of power (Watts Citation2003). Given the shift in development discourse and practices, beginning in the 1980s, from a state-led and top-down to a bottom-up one in the global South, critics argue that development practices tend to play a key role in advancing governmental power over the poor in the name of their well-being (Mosse Citation2005). Hence, contemporary bottom-up development practices, such as PSNP, in the global South can be analysed as forms of Foucault’s government.

Bottom-up development, that comes under many aliases such as people-centred development, local development and alternative development, is a development practice towards achieving locally defined needs through endogenous and community-based strategies with the active involvement of local people and their organizations (Pieterse Citation2010). It is people-centred because it seeks, on the one hand, empowering the poor so that they would be self-reliant in solving development challenges in the long-term, while this can be achieved when it draws on local strategies/knowledge and responds to local realities on the other hand (Pieterse Citation2010). The poor and local communities are made subjects with the capacity to improve themselves with the guidance of CSOs/NGOs. The principal techniques include participation, community-based planning/activities and NGOs/donors’ financial resources. Central to all this is to intervene at the local socio-spatial unit (e.g. community) within which the characteristics, deficiencies and capacities of the poor are revealed. This, from a Foucauldian perspective, is ‘a way of making collective existence intelligible and calculable’ (Li Citation2007, 232). From Scott’s (Citation1998) ‘seeing like a state’ perspective, this permits the state to easily identify, observe, count and monitor its subjects, thereby enhancing the legibility of a society as a whole. This is seen as a condition for ‘successful’ ‘high-modernist’ development interventions though, in this case, from above by the authoritarian state.

Contemporary bottom-up development practices in the global South have, on the other hand, (re)invented communities of various kinds from below (Li Citation2007). The poor are reimagined as forming some sort of intelligible collective existence from below (Li Citation2007). They, Li (Citation2007, 235) writes, are ‘made visible, formalized, and improved where they already existed, crafted where they were absent, or resuscitated where they were disappearing’. This is particularly relevant to nomadic pastoralists, who do not have one specific bounded space, in producing new spatial subjectivity for them.

Then, a variety of participatory approaches, broadly constituted as Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA), have been widely (re)produced and deployed in the global South through which community members are encouraged to reveal their characteristics, deficiencies, capacities and desires, and prepare and execute plans (Mosse Citation2005). The process intensifies the intelligibility of local units of intervention, and it is, Li (Citation2007, 235) argues, ‘the principal [governmental] intervention’. Governmental advances promoted by the technologies of participation can offset people’s conscious resistance triggered by top-down, coercive development practices. Hence, participatory, bottom-up development approaches have rather become effective technologies of government by advancing technocratic control and external interests over marginal areas and people while concealing the agency of outsiders (Mosse Citation2005).

Finally, the governmentality approach is criticized for disregarding human agency and the unintended and different impacts of governmental interventions on different social groups though, following McKee (Citation2009), we argue that the critics do not actually reflect Foucault’s original analysis. Hence, as Li (Citation2007) suggests, Foucault’s governmentality would be, analytically, more robust when it is informed by ethnographic methodology, exploring what actually happens when governmental interventions, such as PSNP, encounter, on-the-ground, not only the practices, processes and agents they seek to improve but also the (implicit) strategic rationalities/goals of the intervening parties, such as the state.

The sedentary Ethiopian state, pastoral development and governing Ethiopian Somalis

State formation in Ethiopia began from the sedentary crop-farming highland around which civilization and development are still defined and organized. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Imperial Ethiopian state expanded to the pastoral lowlands to incorporate the peripheries into the central state by force (Markakis Citation2011). This was usually followed by dispatching members of imperial ruling class from the highland as trustees, a position defined by dar-ager makinat (in Amharic, the will to civilize the peripheries) by expanding and consolidating state bureaucracy and infrastructures.

Regassa and Korf (Citation2018) observe that successive Ethiopian regimes from the Imperial to the current period have intervened in the pastoral lowlands in two interrelated ways, in the manner explored in Scott’s (Citation1998) ‘high modernism’: transforming the ‘underutilized’ pastoral land into productive ones through agro-industry, irrigated commercial farms, dams and infrastructure projects that could contribute to national development at large; and sedentarizing nomadic pastoralists so that they could enjoy modern social services. The recent government’s pastoral development policy (FDRE Citation2008, 11) advocates a ‘[p]hased voluntary sedentarization along the banks of the major rivers as the main direction of transforming pastoral societies into agro-pastoral system, from mobility to sedentary life, from rural to small pastoral towns and urbanization’. All these governmental interventions represent top-down, coercive state territorialization and sedentarization of making peripheral space and subjects governable by excluding or including nomadic pastoralists within particular geographic boundaries and controlling what they do. However, state-planned sedentarization alone has succeeded very little (Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015).

Governmental interventions in the pastoral lowlands under the current EPRDF government share the kind of development vision stated above (Mosley and Watson Citation2016). But what is changed under EPRDFFootnote3 since 1991 is the political-administrative context created by the ethnic federal policy that created ethnically-defined ‘autonomous’ regional states, the Somali regional state is among them (Samatar Citation2004). This new governance structure offered relative local autonomy (Hagmann Citation2005), for example, in organizing development practices by administrators drawn from local communities. The ethnic federal policy created clan-based reterritorialization of pastoral space and local administration, such as in Somali region, enhancing sedentarization (Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015).

As both Ethiopia’s Imperial and Socialist regimes viewed the Somalis incapable to organize and run state institutions (Hagmann Citation2005), state-backed highlanders settled in the Somali lowlands as trustees/administrators (Hagmann and Korf Citation2012). The incorporation of the Somali periphery into the Ethiopian nation state has been very complicated, slow and yet incomplete (Hagmann Citation2005). The Christian highland Ethiopians and elites perceive Ethiopian-Somalis as trouble-makers and alien to the Ethiopian nationhood (Hagmann Citation2005). The Muslim Somalis, in contrary, view state expansion into their territory as colonialism (Hagmann Citation2005) and as imposition of highland Ethiopian values on their way of life (Devereux Citation2010). Successive Ethiopian regimes have attributed the complicated relationship with the Somalis and political instability in the region to the Somalis’ nomadic and ‘backward’ lifestyles (Hagmann Citation2005). Hence, sedentarization has been always promoted as a civilizing mission and consolidation of state power in the Somali peripheries. However, until recently, state capacity to deliver social services is nominal while its territorial control remains limited to military outposts (Hagmann Citation2005). The state-planned sedentarization alone achieved very little support for a very long time, while recently sedentarization has been enhanced by indigenous commodification by the Somalis themselves in the framework of an enabling ethnic federal policy (Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015).

The introduction of ethnic-based ‘decentralized’ federal governance opened up space to incorporate Ethiopian Somalis and their local governance structures into the modern Ethiopian nation state through ‘self-rule’ rather than coercion (Hagmann Citation2005). Despite limitations, Somalis now enjoy self-administration rights, and hence their relations with the central state have become better than ever before (Markakis Citation2011; Samatar Citation2004).

Ethnic-based ‘decentralization’ and self-administration translated into political competition within the Somali regional government and party (Hagmann and Korf Citation2012). Political competition means competition for (state) resources, such as land, among clans (Hagmann Citation2005). Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger (Citation2015, 886) write, ‘different Somali clan lineages attempted to expand and demarcate their home territories, as these claims to territory translated into political power at the level of the regional government’, incentivizing more sedentary lifestyles by pastoral elites. On the other hand, the continued co-option of Somali authorities by the federal government and ruling party made the former subordinate elites who continue to serve federal policies (Samatar Citation2004). Hence, on the one hand, there has been the continuation of centralization of political power in the hands of the federal ruling party and the continuation of anti-pastoral development thinking and practices, while on the other hand, ‘decentralized’ ethnic federalism enables ethnic Somalis to enjoy rights such as self-administration by bureaucrats drawn from local communities – that have offered a sense that Somalis are also stakeholders in the Ethiopian state (Samatar Citation2004). At the interface of the two, as Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger (Citation2015) observe, sedentarization has been increasing.

Sedentarization is conceptualized in a ‘more open fashion, referring as it does to a relative shift, to a decline in nomadism and an increase in sedentism’ (Salzman Citation1980, 11). The shift to sedentism has been a common trend for pastoralists across the globe and has dramatically been increased among East African pastoralists in the late twentieth century as a result of economic, political and environmental changes (Caravani Citation2019; Fratkin, Roth, and Nathan Citation2004). National governments and development agencies have frequently advocated sedentarization as the right path to modernity both locally and nationally.

In Ethiopia the sedentarization dynamics is not so different (cf. Müller-Mahn, Rettberg, and Getachew Citation2010; Regassa and Korf Citation2018; Schmidt and Pearson 2016). As a bottom-up development programme, PSNP's formal policy goal was not actually sedentarization, though as we will show, this has been one of the impacts. However, our purpose is not to reconstruct all of the dynamics of sedentarization. Instead we focus on how the implementation process of PSNP is related to, complicit in and/or serve the sedentarization logic/rationale and interests of the Ethiopian state.

PSNP governmental technologies and practices in the Somali pastoral periphery

One of our major challenges in implementing PSNP was the mobility of pastoralists that complicated the targeting and transferring process … However, this problem is now reduced because of the reduction in mobility … PSNP has helped pastoralists to settle as they are provided with all the necessary services [food/cash transfers and infrastructures] and as the [PSNP] committees and kebeles [administration] are now there to facilitate this. (a Somali man, PSNP coordinator of the Somali Regional State, Jijiga city, 30 May 2018)

Prior to and during the initial period of PSNP implementation in our research area, pastoralists had continually been moving between temporary settlements based on the availability of rangeland resources. Pastoralists continually reconfigure the number of households who move and ‘settle’ together seasonally. During the rainy season when resources were not scarce, large number of households, including distant kinship relatives, ‘settle’ together whereas during the dry season only a very small and close kinship relatives move together and ‘settle’ in stopovers to avoid competition for scarce resources. Ethiopian state-planned sedentarization policy meant regulating this flexible ‘settlement’ on the grounds that it hinders the state’s ‘civilization’ efforts, for example, to expand modern services and infrastructures. It is in the context of this broader (anti-)pastoral development thinking and efforts, PSNP was implemented.

PSNP targeting and the (re)production of the (sub-)kebele as a legible unit of intervention

PSNP implementation began with the identification and creation of visibility of target populations through targeting: the identification of locally legible units of intervention and the selection of eligible clients within these units. In identifying legible and manageable units of PSNP intervention, potential target populations were reimagined as forming many local groups that could collectively be mobilized. Given pastoralists’ mobility across village and even kebele boundaries, and they ‘rarely have clearly defined boundaries that is typical of a community in more sedentary areas’ (FDRE Citation2012), (sub-)kebeles were (re)invented as legible units within which nomadic pastoralists were to be targeted as PSNP clients. The kebele was already functional in the sedentary farming highlands as the lowest administrative unit. However, given Issa/Somali pastoralists’ continuous mobility and evasion of state institutions, for a long period, the kebele has not been, formalized, functional and/or were not known to the pastoralists in our research area. Issa/Somali pastoralists did not have any enduring formal spatio-administrative unit within which they strictly reside and access resources, such as development aid, as the narration of an elderly pastoralist clan leader reveals that

… these so called kebeles and sub-kebeles are recent developments which came following PSNP. There were no so-called Gobeley kebele; Gobenti sub-kebele; Qurenjale sub-kebele; Dhaladu sub-kebele; and so forth. We did not know all these before PSNP. You know, all pastoralists were traveling to the woreda town to receive food aid [that preceded PSNP].Footnote4 (Gobenti sub-kebele, 18 November 2017)

The most important spatial reference in connection to the mobility of pastoralists was rather the Ella (a traditional hand-dug water point), which is used as a dry season reserve for pastoralists, belonging to the lineage group who developed and owned it and that pastoralists mostly considered/referred it as their home/village. Then, a group of clan leaders/elders (leading actors of the very initial targeting), with guidance from woreda authorities and PSNP officers, (re)invented sub-kebeles with reference to and named after their respective Ellas. However, the two did not usually overlap as some Ellas are located just at the periphery of the respective (sub-)kebele and hence are contested by pastoralists who used it as a pretext to move to their Ellas during the dry season.

While the manual prescribed the kebele as the smallest administrative unit for PSNP intervention, the targeting team identified sub-kebele, sub-dividing the kebele further into three locally ‘feasible’ legible units. This was followed by the selection of clients within each sub-kebele in which each nomadic pastoral client is formally assigned to a specific sub-kebele. As (sub-)kebele, as an administrative unit, had not been functional yet, all PSNP implementation activities including those roles that (sub-)kebele authorities are supposed to play were handled by a clan leaders/elders’ committee before it was replaced by a (sub-)kebele administration to the extent that the committee is no longer functional today.

‘As the PSNP quota allocated to us was too small to target all eligible pastoralists and as conflict/competition between pastoralists to be targeted might have been arisen on the spot’, a pastoralist clan leader who involved in the very first targeting process recounts, ‘the committee did the targeting carefully by prioritizing the most needy pastoralists without their direct involvement while we are actually trusted by our fellow pastoralists’ (Dhaladu sub-kebele, 23 March 2018).

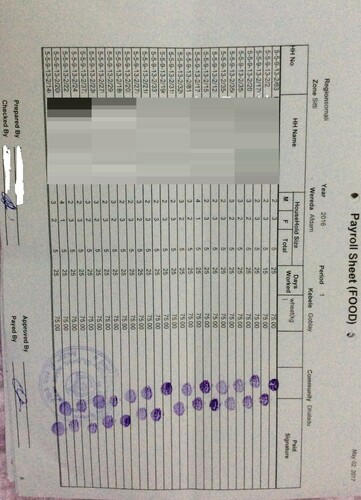

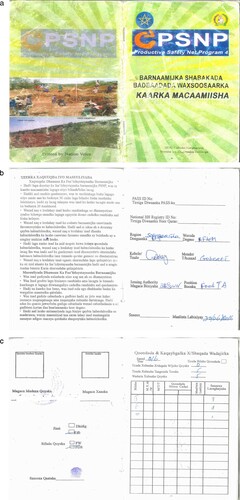

The (re)targeting process formally culminated with the preparation of a ‘Master List’ (an official document that comprises the final selection list of PSNP beneficiary households in a given (sub-)kebele) () and granting PSNP client cards as proof for inclusion in the programme (). The ‘Master List’ objectifies the client in terms of documenting different forms of visibility such as the client’s (sub-)kebele where he/she is targeted, household demography, labour status and the type of intervention sought (public work or direct support). The client card, additionally, carries the client’s photograph and lists of duties and rights that the clients are abide by and give their consent by signing on it. These PSNP inscription devices formalized and stabilized the identification of nomadic pastoralists with (sub-)kebeles where they are targeted. Pastoralists raised their concerns and negotiated with authorities about the compatibility of PSNP implementation with their nomadic livelihoods/lifestyle. Pastoralists then ‘succeeded’ in making PSNP/public work on the move in which they were allowed to keep moving while they could collect their transfers only in the (sub-)kebele where they were targeted.

Figure 3. Sample Pages of client card: (a) cover page; (b) inside page showing, among others, the beneficiary’s duties and rights and the (sub-)Kebele within which the holder becomes beneficiary; (c) inside page showing, among others, the photograph, the name and signature of the holder.

PSNP targeting practices and technologies we presented above produced governable pastoral spaces and subjects that were instrumental for state-planned sedentarization, in four ways. First, by (re)inventing (sub-)kebeles as legible units of intervention and targeting nomadic pastoralists within them, the most evasive Issa/Somali pastoralists are connected to a specific space, (sub-)kebele, in terms of cognition. Second, the cognition is further formalized by objectifying pastoralists through inscription devices (‘Master List’ and client card). The ‘Master List’ and client card have become what Watts (Citation2003) calls ‘micropolitics of power’ through which different regimes of governmental practices are structured as illustrated by livestock tax collection and village statistical data collection incidents below:

‘When I collected livestock tax from pastoralists by excluding the poorest and transferred to the woreda’, a pastoralist kebele administrator recounts, the woreda administrator complained that both the tax amount and number of paying pastoralists are small. I responded that we have only these number of pastoralist households in our kebele. The woreda administrator then immediately pulled out the ‘Master List’ from his office shelf and showed me that ‘but you have this large number of PSNP beneficiaries’. (Dhaladu sub-kebele, 4 March 2018)

One day in the morning while the first author was moving around the kebele office, two young men from the regional statistical bureau suddenly appeared to ask the kebele administrator for a copy of ‘Master List’ who gave them from his office. The first author then asked them why they need it to which they responded that ‘we need it as a source of regional inter-census data while it is difficult to collect first-hand data by moving across this highly dispersed settlement and as many of the pastoralists may currently have moved away from the kebele’. (Dhaladu sub-kebele, 12 March 2018)

Third, the nominal connection of pastoralists to a specific (sub-)kebele is translated into ‘real’ when pastoralists are obliged to collect their PSNP transfers only in the (sub-)kebele where they were targeted. PSNP transfers have now determined pastoralists’ mobility as pastoralists had to regularly visit their PSNP (sub-)kebele to collect their transfers. Finally, the (re)invention of (sub-)kebele, as intelligible unit of PSNP intervention, has coincided with its consolidation as the lowest administrative unit in the pastoral Somali peripheries. PSNP reinforces the latter by making pastoralists legible bureaucratic/administrative subjects as ‘ … we are now already under the full control of the government through kebele and sub-kebele [administrations]’, an elderly pastoralist man regrettably explained, ‘in the name of the so called PSNP benefits, as our profiles and photographs are already documented in the woreda and regional government offices through the ‘Master List’ and client cards’ (Gobenti sub-kebele, 14 December 2017).

Community-based public work and the territorialisation of PSNP upon the (sub-)kebele

Community-based public work is rationalized such that the fields of PSNP interventions are expanded ranging from rangeland management to social service and infrastructure expansion. Participation of pastoralists in these activities is a condition to access PSNP transfers. Participation and community planning are techniques of gaining the consent of pastoralists doing all these in line with their local realities. In this way, pastoralists, ‘successfully’ negotiated with authorities and made PSNP/public work on the move, during the initial period of PSNP implementation. When pastoralists moved to another (sub-)kebele, they were allowed to participate in public work activities there and bring a letter from the (sub-)kebele administrator testifying their participation to collect their transfers.

On the other hand, PSNP/public work was (re)interpreted by local authorities, from the very beginning, as an incentive of transforming pastoralists into sedentarized farmers as the strategy through which pastoralists would be food secure. Its approaches, participation and community planning, were, (re)interpreted as techniques of shaping, rather than responding to, pastoralists’ desires. A former half Somali rural animal health technician who was also responsible for PSNP implementation narrates his experience:

Our intention was to target pastoralists in our kebele as sedentarized PSNP beneficiaries. Pastoralists would then participate in public work activities such as water point development … that would make the area favourable for sedentary crop-farming … They would then become self-sufficient in food. (Afdem town, 26 April 2018)

Public work has later been made immobile on the grounds that mobile public work is not convenient for programme management in view of, paradoxically, PSNP’s community-based principles, according to authorities. It is not convenient, one Somali PSNP officer argued, ‘because under mobile public work it was not possible to establish durable public work teams who can continuously come together to plan, execute and evaluate their activities and that posed challenges for us to monitor their team activities as they move into different places and join different teams at different times’ (Afdem town, 25 November 2017). Pastoralists, then, organized themselves in public work teams within their respective (sub-)kebeles they were targeted to contribute 15–25 days of public work labour per month for 6 months in a year and, therefore, have to stay there for that period.

Public work teams, with the guidance of PSNP officers, participated in the construction of primary schools, health posts, community roads, check dams, rangeland enclosures and rainwater reservoirs. Pastoralists are then directed, by authorities, to use public work outcomes efficiently by staying around. The primary school is a good example. ‘Representatives of donors and regional government officials warned woreda and kebele authorities of cutting funding if no one is using the infrastructures constructed’, a non-Somali kebele animal technician remembers, ‘when they, during their field visit, found out the [primary] school in our kebele was not attended by students as pastoralists moved away for better grazing resources’ (Dhaladu sub-kebele, 10 September 2017). As the construction of primary schools within each sub-kebele transformed mobile into immobile education to which pastoralists failed to send their children during mobility, sending children to schools has become a condition for accessing PSNP transfers. A non-Somali schoolteacher narrates

as we [teachers and (sub-)kebele authorities] were under pressure from the woreda authorities to increase school enrolment, we discussed with and convinced clan leaders about denying PSNP transfers for those pastoralists who fail to send their children to school even if they participate in public works. As education is a prioritized development agenda, woreda authorities acknowledged our measures though it is clear for all of us that our measures are contrary to the rules and principles of PSNP. (Afdem town, 17 April 2018)

Pastoralists then started to ‘settle’ around schools in their respective sub-kebeles and when mobility is unavoidable, they either left half of the family members (usually women) with schoolchildren or chose one or two household/s to stay near to the schools to take care of the schoolchildren of all other moving households who, in return, take care of the livestock of the staying household/s. In cases of missed public work participation by moving pastoralists, local authorities are sometimes ready to compromise. Sedentarization is, thus, in the making by consent and domination. A pastoralist kebele administrator narrates:

the government [woreda authorities] has, for a long time, mandated us to sedentarize pastoralists and to enclose land for crop-farming, but it was impossible for us to implement them before PSNP. I think our sedentarization process will be jeopardized if PSNP is stopped, as pastoralists are staying here because of PSNP transfers. (Dhaladu sub-kebele, 4 March 2018)

The (sub-)kebele which was modelled in thought, cognition and conviction through PSNP targeting process is now re-modelled as ‘real’ and material governable and populated space through public work practices and outcomes. Public work accomplished this in three ways. First, by including or excluding pastoralists, subjected to the conditionality of participation in ‘immobile’ public works, from certain spaces bounded as (sub-)kebeles. Second, by guiding what (public work sub-projects) pastoralists should do there in the name of participatory approaches. Third, by directing pastoralists’ access to and use of social services and infrastructures developed by public work. In connection to this, access to and use of rainwater reservoir, as a public work outcome, has excluded/included certain pastoral resource users within (sub-)kebele boundaries as local authorities decided that the reservoir should be used only by pastoralists who participated in building it following a conflict between members of two neighbouring sub-kebeles over access to a reservoir in one of the two sub-kebeles.

All these decisions coincide with the sedentary metaphysics of Ethiopian state and accelerated more the trend towards sedentarization than decades of coercive state-planned, top-down policies had ever done. As the argument of the kebele administrator above goes, however, pastoralists may return to nomadic pastoralism again once PSNP stopped because, as Randall and Giuffrida (Citation2006) observe, pastoralists oscillate between sedentary and mobile lifestyle depending on (economic) situations/incentives. On the other hand, sedentarization is not a non-contingent, unidirectional process (Fratkin, Roth, and Nathan Citation2004). Hence, PSNP is not simply food/cash transfer with which pastoralists settle and without which pastoralists resort back to mobility, but an assemblage of contingent material and non-material resources and practices that have enhanced the visibility and legibility of pastoralists as conditions of sedentarization.

The ‘decentralized’ ethnic federal governance provided enabling political-administrative framework for the practice of PSNP from below. Somali bureaucrats/politicians have now relative autonomy to (re)interpret and modify/manipulate national policies (PSNP) in the way they feel to ‘fit’ to the development demands of their fellow pastoralists (in this case sedentary crop-farming). Supporting this, as the following narration of an elderly pastoralist man reveals, pastoralists have been nudged to being ‘governed’ by the new self-ruling local government run by Somali administrators drawn from local communities:

We used to run away whenever we saw men dressing trousers [who used to be non-Issa/Somali bureaucrats from the highland ruling class]. It is only after the EPRDF government that we have gradually approached the government as our clan leaders and respected elders are assigned as local administrators and as we have been continuously receiving food aid [and PSNP] while the government also use these administrators to collect tax from us. (Gobenti sub-kebele, 4 December 2017)

PSNP as a readily available resource for building a state bureaucracy

PSNP is one of the largest resource transfer programmes in Africa financed by a World Bank-managed ‘Harmonized Multi-Donor Trust Fund’ (Pankhurst and Rahmato Citation2013). The total planned project cost for phase 4 (2014/2015–2019/2020), was USD 3.6 billion (World Bank Citation2014) which is equivalent to 28% of Ethiopia’s total annual budget in 2018/2019. The deployment of PSNP’s technologies and large number of implementing apparatuses and bureaucrats was possible with this large resource flow. PSNP is able to reach almost all pastoralist households both materially and bureaucratically. Pastoralists have been encouraged by the predictability and reliability of PSNP transfers to engage in active practices of self-management in connection to PSNP implementation.

Local authorities are helped by PSNP finances in the face of fiscal budget deficits for running government activities in general. Given PSNP’s principle of integration into woreda development activities, woreda authorities have commonly shifted PSNP budget to other local development projects and bureaucratic activities most of which divert from PSNP’s formal goals. PSNP officers have a better salary and per diem than other local bureaucrats. Pastoralists’ representatives, such as clan leaders, are financially encouraged to mobilize their communities. Clan leaders and (sub-)kebele officials, are paid a per diem from the (sub-)kebele PSNP budget (mostly in terms of offering them extra PSNP client cards) and are exempted from providing public work labour as compensation for coordinating (re)targeting and public work activities. Members of a so called ‘School Committee’ are also paid a per diem and are exempted from providing public work labour for their roles in going door-to-door to mobilize pastoralists to send their children for schooling.

While there is no official fiscal budget allocation for (sub-)kebele administration, including salary for its officials, PSNP budget has been locally and informally used as the main source of subsidy for (sub-)kebele administrative expenses. During PSNP (re)targeting, sub-kebele officials retain significant numbers of client cards – ‘up to 25 per sub-kebele’, as one schoolteacher who actively involved in the (re)targeting processes indicates – to cover administrative costs of their respective sub-kebeles, they claim. This is apart from the number of client cards – ‘between 5 and 10’, the same schoolteacher indicates – each sub-kebele official retains as a per diem for his/her roles as PSNP implementer. Moreover, by negotiating through clan leaders, (sub-)kebele officials deduct cash from the pastoralists’ own PSNP transfers in the name of covering (sub-)kebeles’ administrative costs and to pay, for example, the regional ruling party fees the woreda collects from each kebele.

As a result, the (sub-)kebele has been consolidated as part of the local state bureaucracy. It is now populated and run by pastoralist government officials paid with PSNP financial resources. To continue accessing these benefits, (sub-)kebele officials compete to stay within the (sub-)kebele bureaucracy which depends on their ability to take and effectively implement bureaucratic mandates from the woreda authorities. As a result, pastoralist Somali officials within the (sub-)kebeles are made into bureaucratic subjects to intensify state power rather than helping their fellow pastoralists to resist the state. In doing so, PSNP financial resources have enabled Ethiopian state to (re)establish and/or consolidate its (sub-)kebele bureaucratic apparatus in the Somali periphery. This supports Ethiopian state’s strategic interests of expanding its bureaucratic power and enhancing sedentarization in the Somali pastoral peripheries.

Negotiating (and evading) PSNP governmental practices and technologies

The implications of PSNP rationalities and practices for their livelihoods and lifestyles, as discussed above, put Somali pastoralists in a different position vis-à-vis authorities and implementers/experts: they also provoke them in words and deeds that lead to negotiations. The negotiation of PSNP’s key component, public work, is illustrative. Pastoralists challenge the very rationality of and their participation in public work sub-projects, such as terracing, check dams and rangeland enclosure. The diagnosis and prescriptions of state experts are generally based on outdated normative concepts of overgrazing, deforestation and soil degradation triggering droughts and explaining pastoralists’ food insecurity so that these public work sub-projects are presented as long-term, sustainable solutions. Pastoralists, drawing on their situated ecological and historical knowledge, on the other hand, claim that the real problem is bigger, than experts thought, which is deteriorating rainwater infiltration rate and hence quick loss of soil moisture, which is critical to support grass growth during the dry season, because of large-scale landform transformation from plains to rugged terrain over time. Asked if there is anything not addressed in the interview that he wants to tell at the end of the interview with an elderly pastoralist man under the shade of a tree, ‘do you see that hill?’, he asked by pointing a hill far away with his stick, ‘it used to have an extensive flat land at its top supporting the growth of grass throughout the year that used to be our dry season grazing reserve. We do not have that now as it has been transformed into rugged landscape, increasing runoff, reducing rainwater infiltration and soil moisture. So, you told me that you came from Europe; would you please help us bringing technologies to re-label the hill so that it will be restored to its previous quality’ (Qurenjale sub-kebele, 17 March 2018). The solution must be, pastoralists prescribe, large-scale re-labelling of the landform using bulldozers and other high-capacity technologies than those very minor-scale public work rangeland management. The environmental impact of the latter is, pastoralists challenge, insignificant except wasting their precious time and labour, and restricting their mobility in the name of public work participation. However, the nature of public work is not yet changed while pastoralists continue to participate but by manipulating it by using participatory planning as a negotiation space and by invoking their situated knowledge at the expense of scientific-expert knowledge. A pastoralist sub-kebele deputy administrator, who coordinated public work teams, explains how:

As PSNP officers and local authorities do not have sufficient knowledge on rangeland management public work sub-projects, and as they become ashamed of exposing their ignorance when we ask them about how these sub-projects are related to our local environmental problems and the implementation is justified, they sometimes just tell as to do what we wish and to report. This is a good opportunity for us to identify and do public work activities which do not harm our livelihoods and require little labour and time. (Gobenti sub-kebele, 20 December 2017)

Concomitantly, pastoralists, using metaphors, make critical observations about public works by making fun at communicating with each other through these metaphors, implying pastoralists’ possible reactions in deeds. They metaphorically call public work as ‘muruqi mali’ (in Somali, milking labour) and ‘neefkii leed’ (in Somali, kicked out at your cow) to express public work as labour exploitative and compromising pastoralists’ livelihood (livestock), respectively.

Moreover, pastoralists applied combinations of Scott’s (Citation1990) ‘hidden’ and ‘public transcripts’ to evade/negotiate PSNP’s directive for sedentarization as illustrated by the ‘empty tent story’. To evade sedentarization, pastoralists applied the empty tent technique: when PSNP transfers became conditional on sedentarization, pastoralists prepared two tents so that when they move away from the expected sedentarization sites, each household left one standing empty tent (while a few older women in the community stay behind) while they move with their second tent. So, they tricked local authorities or outsiders to believing that pastoralists are still there by observing standing tents while many of which are actually empty. This strategy is reinforced with mutual compromises between pastoralists and authorities. While the former use unmet government promises as pretext to evade sedentarization, the latter soften their sedentarizing directives in the face of pastoralists’ mobility for dry season reserve resources. A married pastoralist woman justifies her mobility that ‘when they [local authorities] built the school here and told us to settle around, they promised to build water supply here which has not been realized. So, we keep moving to access water. They are asking us why we keep moving. We ask them where is the water you promised … ’ (Qurenjale sub-kebele, 30 December 2017).

However, by negotiation for the Issa/Somali pastoralists, who historically stayed out of the reach of state bureaucracy and development apparatuses, means coming to make compromises in which the gradual government of pastoralists in space is implied as illustrated by the narration of an elderly pastoralist man:

they [local authorities] first asked us to send our children for schooling. We told them it is not compatible to our nomadic lifestyle. They promised us that it is mobile education. We accepted. One mobile teacher used to move with us. We used to build temporary schools wherever we go with public work labour. Then, they built permanent schools in some kebeles to stop mobile education. We complained. They then made us to (re)admit our children to the nearest school where we move to. They then built ‘unnecessary’ schools ‘everywhere’ just to restrict our mobility. Now our children cannot be (re-)admitted in other schools beyond our own kebele. If we fail to send our children to only schools in our kebele, they withhold our PSNP transfers … They are now forcing us to settle near to schools to facilitate school attendance by allowing only adult men to move with livestock. It is a matter of time that they will restrict even the mobility of adult men.

As Li (Citation1999, 316) reminds us, rule, such as developing/governing pastoralists, is accomplished through such negotiations that ‘draw people into compromising positions and relationships’. In the context of all such negotiations and/or compromises, on the one hand, sedentarization of Somali nomadic pastoralists is not a complete but evolving project while, on the other hand, pastoralists are now more visible and intelligible within governable (sub-)kebeles than have been ever before, the view equally shared by pastoralists and authorities.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we have shown that the regimes of practices and technologies of PSNP enhanced the trend towards sedentarization in the Somali pastoral peripheries. We have illustrated how this trend results not only from the PSNP policy, but also through its entanglement with the sedentary metaphysics of the Ethiopian state. Through our analysis of three domains of PSNP practices (i.e. targeting, community-based public work and financial resource flows), we have shown that sedentarization does not necessarily mean a complete and permanent settlement of pastoralists in fixed places, but rather changing and evolving trends towards more settlement – in connection to the operations of PSNP practices and technologies – that coincides with the logic of a sedentary order-of-things.

With respect to targeting, we have shown how targeting has served to (re)produce administrative units, the (sub-)kebeles as local spaces of intervention within which the most evasive nomadic pastoralists are made visible, legible and documented in a demarcated space as PSNP clients. This has created forms of visibility of nomadic pastoralists necessary for the operation of certain governmental regimes, beyond PSNP rationalities and goals, such as sending children to school as a condition for becoming beneficiary of PSNP. In this way, PSNP, ‘unintendedly’, promotes sedentarization as a condition for and/or an integral part of ‘orderly development’, couched in the discourse of civilization of the ‘unruly’ nomadic pastoral subjects. This relates to PSNP’s second regime of practices: community-based public works.

We have illustrated how community-based public work sub-projects, such as the expansion of social services and infrastructure, have been developed with the formal policy rationality that they are long-term investments in community resilience. We have shown, however, how these projects had the effect of directing pastoralists to participate in public work activities, and access and use of the outcomes within the (sub-)kebeles where they were targeted. We have outline how in turn these community-based public works supported more stable and sedentary (sub-)kebele boundaries – the (re)territorialisation of pastoral spaces – within which pastoralists’ mobility, activities and access and use of resources are limited/controlled. We note that this is an ‘unintended’ outcome of PSNP, but it is a necessary one from the perspective of sedentary rationality/goal of the Ethiopian state.

Finally, we show how these first two regimes of practices were possible through financial resource flows (from international donors, such as the World Bank). These financial resources offered predictable and reliable resource transfers for pastoralists to encourage them into active practices of self-management, financed assemblages of material and non-material PSNP governing practices. These financial resources also subsidized the consolidation of local (sub-kebele) bureaucratic apparatus to extend government over the Somali peripheries.

With respect to why and how did PSNP enhanced the trend towards sedentarization (which was not its formal policy goal) more than state-planned sedentarization programmes, for their own sake, had ever achieved in the past, we put forward the following. First, PSNP, as a so-called bottom-up development project, set conditions in which, following Dean (Citation2010), governing pastoralists (in terms of sedentarization) becomes ‘effective’ by relying upon their own agency (and organizations). Our analysis has documented how PSNP mobilized clan leaders/elders, as representatives of pastoralists, who, in their actions, were complicit in state bureaucratic control and/or cynical manipulation. On the other hand, while some PSNP participatory policy promises actually remained rhetoric, some others conflated with and become instrumental for top-down pastoral development practices.

Second, and in line with Samatar (Citation2004), we have shown how PSNP was implemented under the new ‘decentralized’ ethnic federal policy which granted regional self-rule that, at the same time, helped the (central) state to mobilize ethnic Somali leaders and make them into bureaucratic subjects as local collaborators of the state.

Following Dean (Citation2010, 88), we recognize ‘the disjunction between the explicit rationalities of government … [the stated and explicit intentions of PSNP] and the more or less implicit logic of these practices (how these practices operate as revealed by the analysis)’. While the disjunction may be interpreted as a ‘failure’ from the perspective of stated intentions of PSNP, it is a ‘success’, for the Ethiopian state, because it helps extend ‘government’ over hitherto ‘ungoverned’ pastoralists. However, the sedentarization process, as a governmental strategy, is far from complete given the agency of pastoralists to ‘negotiate’ in favour of their nomadic pastoral practices. Nevertheless, in the context of historically-embedded structural deprivation, the agency of pastoralists was not absolute and making compromises was part of their negotiation strategy.

To conclude, the Ethiopian government’s (pastoral) development discourse and policy, more broadly, embodies a rationale with sedentarization as a precondition for, and an integral part of, pastoralists’ civilized life and progress (FDRE Citation2008). Pastoral development, in this sense, becomes synonymous with sedentarization as the ‘right manner of disposing things’ in pursuit of not just a dogmatic/programmatic policy goal but improvement of the condition of pastoralists more generally. Hence, we argue that analysis and understanding of how (and why) PSNP was implemented in the Somali periphery should be made in connection with such broader (pastoral) development thinking and the sedentary metaphysics of Ethiopian state.

We argue that so-called bottom-up development practice is, in turn, an ‘effective’ mechanism of governing citizens (in the peripheries) at a distance and a tool for state-building in the periphery. In this way ‘neutral’ outside donors become parties in the project of state building of the Ethiopian state in the periphery by (unwillingly?) promoting the establishment of government. Our findings simultaneously highlight the agency of the governed to act otherwise, so that governmental interventions rarely completely realize their desired/intended outcomes while they may have unintended outcomes and different impacts on different social groups.

Acknowledgements

Getu Demeke Alene acknowledges the scholarship and fieldwork financial support from Netherlands Fellowship Programme (NFP) and Open Society Foundations (OSF), however, the opinions expressed herein are the authors’ own. A draft of this paper was first presented at a Summer School seminar on ‘Social Policy in the Global South: The Challenges of Socio-economic justice and Agro-ecological Development’ at the Sam Moyo African Institute for Agrarian Studies (SMAIAS), Harare, Zimbabwe, 21–25 January 2019, and later at Development Studies Association Conference at the Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom, 19–21 June 2019. We thank the participants for their constructive comments. We also thank this journal’s two anonymous reviewers who provided immensely helpful comments that have improved the paper significantly.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Getu Demeke Alene

Getu Demeke Alene is a PhD candidate at Wageningen University and Research. His research focuses on governmental interventions in food security and social protection, mainly in pastoralist contexts.

Jessica Duncan

Jessica Duncan is an Associate Professor in Rural Sociology at Wageningen University. She holds a PhD in Food Policy from City University London (2014). Her research areas include: food policy; food security; global governance; environmental policy; and participation. She researches relationships between global governance mechanisms, food provisioning, the environment, and the actors that interact across these spaces. More specifically, she is interested in better understanding ways in which non-state actors participate in supra-national policy making processes, and analysing how the resulting policies are implemented, shaped, challenged and resisted in localized settings. She sits on the editorial board for the journal Sociologia Ruralis and works as an associate editor for the journal Food Security. She also acts as an advisor and researcher with Traditional Cultures Project (USA).

Han van Dijk

Han van Dijk is a personal Professor at the Sociology of Development and Change Group at Wageningen University and Research. His research focuses on land tenure, pastoralism, natural resource management and conflicts, land governance in post-conflict situations, state formation, climate change adaptation and health governance.

Notes

1 Kebele is the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia, similar to a ward/neighbourhood while in some cases, such as in our research setting, it may be further divided into smallest units, sub-kebele, similar to village.

2 The fourth level administrative unit/division within the Ethiopian federal government structure, similar to district.

3 EPRDF, used to be a coalition of four ethnic-based parties, transformed itself into a one centralized party called Prosperity Party in 2019 (after our fieldwork) by merging all ethnic-based regional parties including those from the pastoral lowlands, while one of its dominant founding members, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), left out. However, the policy on ethnic federalism is not yet changed.

4 This, as a pastoralist sub-kebele deputy administrator indicates, does not necessary mean there was no kebele administration at all before PSNP, but was not functional and hence was not known to pastoralists before PSNP.

References

- Afdem Woreda. 2018. “Woreda Annual Safety Net Plan.” Agricultural and Natural Resource Development Office.

- Beyene, F. 2009. “Property Rights Conflict, Customary Institutions and the State: The Case of Agro-Pastoralists in Mieso District, Eastern Ethiopia.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 47 (2): 213–239.

- Beyene, F., and B. Korf. 2012. “Unmaking the Commons: Collective Action, Property Rights, and Resource Appropriation among (Agro-)Pastoralists in Eastern Ethiopia.” In Collective Action and Property Rights for Poverty Reduction Insights from Africa and Asia, edited by E. Mwangi, H. Markelova, and R. Meinzen-Dick, 304–327. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Caravani, M. 2019. “‘De-pastoralisation’ in Uganda’s Northeast: From Livelihoods Diversification to Social Differentiation.” Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (7): 1323–1346.

- Catley, A., J. Lind, and I. Scoones. 2013. “Development at the Margins: Pastoralism in the Horn of Africa.” In Pastoralism and Development in Africa: Dynamic Change at the Margins, edited by A. Catley, J. Lind, and I. Scoones, 1–26. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dean, M. 2010. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Devereux, S. 2010. “Better Marginalised Than Incorporated? Pastoralist Livelihoods in Somali Region, Ethiopia.” European Journal of Development Research 22 (5): 678–695.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). 2006. PSNP Programme Implementation Manual. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). 2008. Draft Policy Statement for the Sustainable Development of Pastoral and Agro-Pastoral Areas of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Federal Affairs.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). 2010. Productive Safety Net Programme: Programme Implementation Manual. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). 2012. Guidelines for PSNP – PW in Pastoral Areas. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). 2016. Productive Safety Net Programme: Phase 4 Programme Implementation Manual. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Foucault, M. 1991. “Governmentality.” In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality with Two Lectures by and an Interview with Michel Foucault, edited by G. Burchell, C. Gordon, and P. Miller, 87–104. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fratkin, E., E. A. Roth, and M. Nathan. 2004. “Pastoral Sedentarization and Its Effects on Children’s Diet, Health, and Growth Among Rendille of Northern Kenya.” Human Ecology 32 (5): 531–559.

- Hagmann, T. 2005. “Beyond Clannishness and Colonialism: Understanding Political Disorder in Ethiopia's Somali Region, 1991–2004.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 43: 509–536.

- Hagmann, T., and B. Korf. 2012. “Agamben in the Ogaden: Violence and Sovereignty in the Ethiopian – Somali Frontier.” Political Geography 31: 205–214.

- Hogg, R. 1992. “Should Pastoralism Continue as a Way of Life?” Disasters 16 (2): 131–137.

- Korf, B., T. Hagmann, and R. Emmenegger. 2015. “Respacing African Drylands: Territorialization, Sedentarization and Indigenous Commodification in the Ethiopian Pastoral Frontier.” Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (5): 881–901.

- Li, Tania M. 1999. “Compromising Power: Development, Culture, and Rule in Indonesia.” Cultural Anthropology 14 (3): 295–322.

- Li, Tania M. 2007. The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Little, D. P., J. McPeak, B. Barrett, and C. and Kristjanson. 2008. “Challenging Orthodoxies: Understanding Poverty in Pastoral Areas of East Africa.” Development and Change 39 (4): 587–611.

- Markakis, J. 2011. Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers. New York: James Currey.

- McKee, K. 2009. “Post-Foucauldian Governmentality: What Does it Offer Critical Social Policy Analysis?” Critical Social Policy 29 (3): 465–486.

- Mosley, J., and E. E. Watson. 2016. “Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10 (3): 452–475.

- Mosse, D. 2005. Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. London: Pluto Press.

- Müller-Mahn, D., S. Rettberg, and G. Getachew. 2010. “Pathways and Dead Ends of Pastoral Development among the Afar and Karrayu in Ethiopia.” The European Journal of Development Research 22: 660–677.

- Pankhurst, A., and Desalegn Rahmato. 2013. “Food Security, Safety Nets and Social Protection in Ethiopia.” In Food Security, Safety Nets and Social Protection in Ethiopia, edited by Rahmato Desalegn, A. Pankhurst, and J. van Uffelen, xxv–xlv. Addis Ababa: Forum for Social Studies.

- Pieterse, N. J. 2010. Development Theory: Deconstructions/Reconstructions. London: Sage.

- Randall, S., and A. Giuffrida. 2006. “Forced Migration, Sedentarization and Social Change: Malian Kel Tamasheq.” In Nomadic Societies in the Middle East and North Africa: Entering the 21st Century, edited by D. Chatty, 431–462. Leiden: Brill.

- Regassa, A., Y. Hizekiel, and B. Korf. 2019. “‘Civilizing’ the Pastoral Frontier: Land Grabbing, Dispossession and Coercive Agrarian Development in Ethiopia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (5): 935–955.

- Regassa, A., and B. Korf. 2018. “Post-Imperial Statecraft: High Modernism and the Politics of Land Dispossession in Ethiopia’s Pastoral Frontier.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12 (4): 613–631.

- Salzman, P. C. 1980. “Introduction.” In When Nomads Settle: Processes of Sedentarization as Adaptation and Response, edited by P. C. Salzman, 1–20. New York: Bergin Publishers.

- Samatar, A. 2004. “Ethiopian Federalism: Autonomy Versus Control in the Somali Region.” Third World Quarterly 25 (6): 1131–1154.

- Scoones, I. 1995. “New Directions in Pastoral Development in Africa.” In Living with Uncertainty: New Directions in Pastoral Development in Africa, edited by I. Scoones, 1–36. London: ITDG.

- Scott, J. 1990. Domination and the Art of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Scott, J. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Watts, M. 2003. “Development and Governmentality.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 24 (1): 6–34.

- World Bank. 2014. “International Development Association Project Appraisal Document on Proposed Credit in the Amount of USD 600 Million to the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia for Productive Safety Nets Project 4.” Report: PAD1022.