ABSTRACT

The mid-2000s foreign headway over China’s soybean downstream complex, known as the battle of the beans, reinforced an uncritical nationalist discourse over food security based on a Sino-foreign dichotomy. This article demonstrates through an empirically rich analysis based on four crucial Chinese SOEs that such a discourse ignores diverging capitalist accumulation strategies as two SOEs (COFCO and Chinatex) took advantage of global soybean price fluctuations to grow in association with foreign agribusiness. Instead, I suggest that food security reflects dynamic state-capital relations in China evidenced by the political reaction of two state-owned competitors (Jiusan and Sinograin), endorsing its nationalist appeal.

Introduction

Since the Cold War period, when geopolitical conflicts and the US embargo threatened China’s food provision, the Communist Party has raised food security as a strategic policy and associated it with a pursuit for self-sufficiency (Zhang Citation2018). The mid-1990s’ agricultural stagnation and food shortages followed by China’s subsequent soaring urban consumption brought food security back to the political agenda (Bramall Citation2009, 215). However, critical scholars draw attention to an ideological shift in line with the party’s current reformist agenda, which has sustained capitalist transition in the countryside (Lin Citation2017; Zhan Citation2017). Whereas the Maoist regime saw land redistribution and rural collectivisation as a precondition for food self-sufficiency, the recent reform and opening-up embraced agricultural modernisation under capitalist imperatives, favouring large agribusiness as the primary vessel of domestic food provision (Zhan Citation2017, 160).

With the total liberalisation of soybean imports upon China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, the Chinese government took the international provision of soybean and other feed crops as a supplement for its food security policy (Zhang Citation2018, 47–48). The combination of liberalisation and government incentives and fiscal protection on agri-food processing allowed the rise of correlated import-based feed meal and cooking oil production plants in China’s coastal regions (Sharma Citation2014). Meeting the interests of domestic processors, the government promoted independent sourcing strategies overseas and made continuous efforts to improve China’s pricing power by diversifying soybean supply – including the partial maintenance of local Chinese farming (Myers and Guo Citation2015). In this way, the Chinese narrative around food security reinforced an uncritical nationalist appeal, emphasising the need to control supply chains and sustain domestic production without considering the means through which it achieves this goal (Yan, Chen, and Ku Citation2016, 384).

Nevertheless, given its early liberalisation and consequent integration into global value chains, the Chinese soybean downstream complex became vulnerable to price speculation led by transnational corporations (TNCs) – particularly the so-called ABCD (Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus), that constituted a trade oligopoly over most of the world agricultural commodities’ trade. The battle of the beans is the most emblematic expression of this scenario. Accordingly, amidst the overflow of imports into the domestic market, two global waves of price fluctuations hit the soybean processing industry during 2003/2004 and 2007/2008. Already in the first wave, when prices spiked, Chinese enterprises overpaid approximately US$1.5 billion of soybean imports compared to the previous period (Wen Citation2008). As a result, around 3,000 of them could not absorb the losses and went bankrupt (Cui and Zeng Citation2011, 11). Following the Chinese domestic debacle, foreign TNCs took the opportunity to expand their processing capacity by refinancing and acquiring bankrupted enterprises. In the end, they obtained the direct or indirect control of 70 per cent of China’s processing capacity (MOA Citation2009; cited in Yan, Chen, and Ku Citation2016, 374). Meanwhile, global price fluctuations and the inflow of genetically modified (GM) soybeans in the domestic market led to the stagnation of Chinese soybean agriculture, pushing small farmers out of production (Oliveira and Schneider Citation2016).

During the battle of the beans, the foreign headway instigated the revival of a public debate about food self-sufficiency in China. Nevertheless, as Yan, Chen, and Ku (Citation2016) point out, even though many scholars and social activists took a critical stance against soybean liberalisation, most of them followed a nationalistic appeal in line with the party’s reformist agenda. They stressed the distinction between Chinese and foreign ownership while endorsing the vertical integration of large agribusiness in multiple agricultural segments to the detriment of small households (see Guo Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Citation2010; Li Citation2009; Su Citation2009; Zhuang Citation2009; Guo Citation2012). This article indicates, though, that their nationalistic appeal only corresponds to the interests of a specific state segment represented by a group of Chinese enterprises that operated in the soybean downstream complex. These were primarily the centrally controlled state-owned China Grain Reserves Corporation (henceforth Sinograin) and Jiusan Oils and Grains Industries (henceforth Jiusan), the soybean processing subsidiary of the local state-owned Beidahuang. Both enterprises went through corporate reforms and adopted profit-seeking strategies into soybean logistics, processing, and trade (interview with Zhao, Xin, 29 March 2019).

At the same time, they took a strategic role in the state macroeconomic policies towards domestic agriculture. Sinograin administered the central state grain reserve, whose primary function was to regulate agricultural supply and price. Whilst following market principles, it acts similarly to a ministerial agency through policy-driven operations, corresponding to long term economic planning (Yang Citation2014). In turn, Jiusan’s parent company Beidahuang was one of the only Chinese enterprises with abundant farmland and directly engaged in agricultural production (Wang, Wang, and Wei Citation2013). It was the corporate arm of the North-eastern Heilongjiang Province Farms and Land Reclamation Bureau, responsible for most of China’s soybean production, through which Jiusan’s soybean crushing plants acquired a significant part of their supply (Smith Citation2017). Hence, Jiusan and Sinograin grew through domestic circuits of production and consumption in the soybean downstream complex, relying on a stable resource supply under the state/party leadership.

Whereas these two SOEs adopted an accumulation strategy in line with China’s actual food security narrative, two other big state-owned competitors went in an opposite direction. These were the China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation (henceforth COFCO) and China National Textile Corporation (henceforth Chinatex). As state trading monopolies, they built a long-standing relationship with agribusiness TNCs – who depended on them to reach commercial agreements with China. Although COFCO and Chinatex were traditionally government instruments for managing commodity markets (McCorriston and MacLaren Citation2010), they strengthened their global collaboration during the battle of the beans and ventured into speculative trade alongside transnational agribusiness. As they shared with foreign counterparts the economic benefits of soybean price fluctuation, they took over domestic processors through Sino-foreign joint ventures, consolidating themselves among the leading players in the soybean downstream complex.

To understand COFCO’s and Chinatex’s expansion trajectory, the following section brings up Oliveira’s (Citation2017, Citation2018) analysis on Chinese investments in Brazil, emphasising the agency aspects of Chinese sourcing strategies and its plural and destabilising outcomes in contrast with the state capitalism paradigm. Instead of a durable process strategically coordinated by Beijing, I suggest that COFCO’s and Chinatex’s early investments in Brazil were susceptible to change according to contextual and personal factors. Accordingly, between 2003 and 2008, COFCO and Chinatex built direct trade relations with Brazilian cooperatives and commercial intermediaries for importing soybeans. However, as Oliveira (Citation2018) points out, world price volatility and the subsequent crisis in the Chinese soybean complex discouraged these local players to partner with Chinese enterprises, undermining COFCO’s and Chinatex’s sourcing strategy. Even so, given their economic resilience as state traders, COFCO and Chinatex obtained the preferential collaboration of the ABCD, proving to be stable and attractive soybean importers. Just after facing hostility from those agribusiness TNCs in Brazil, COFCO and Chinatex were welcomed to purchase and transport soybeans from Brazilian ports with their help. In the end, the battle of the beans reconfigured the Chinese investment approach overseas, from independent sourcing to a ‘subordinated alliance’ with foreign capital.

However, I argue that by stressing the agency aspects of China’s changing sourcing strategies overseas, scholarship often incurs the risk of disconnecting it from broader political and economic analysis. Instead, I indicate through the lens of the Marxist uneven and combined development concept that those Chinese outbound agricultural investments are deeply rooted in historical determined social relations underpinned by different forms of capitalist accumulation. As Nogueira and Qi (Citation2018) indicate, China’s recent integration into the world economy entailed intricate state-capital relations in which class conflicts underpinned changes in its political structures. In the state sector, corporate reforms, including ownership diversification, market-oriented management, and competitive orientation at the provincial and federal levels, have changed the SOE’s mission from delivering public goods to obtaining profits (Gallagher Citation2005; Andreas Citation2008). From an individual perspective, those reforms became fast vehicles for great fortunes through executives’ self-enrichment practices – such as ‘super salaries’, the concentration of positions, often occupied at more than one subsidiary, ownership shares in their own and other companies, illegal part-time jobs at private businesses and other forms of corruption – and private investors’ penetration in the state sector.Footnote1

I argue that the agency factors that move Chinese enterprises to go abroad are intimately connected with heterogenous capitalist expansion at home and their expression in diverging segments of the state. Accordingly, section ‘Capitalist Accumulation Integrated to Global Finance’ indicates that COFCO’s and Chinatex’s association with foreign agribusiness TNCs in Brazil propelled an accumulation strategy integrated into global finance and at odds with China’s actual food security governance (discourse and policies). As COFCO and Chinatex developed a trade alliance with the ABCD, they reproduced their investment methods, submitting soybean processing and farming to speculative interests through growing financialization of production. Thereby, the two Chinese state traders overcame initial losses during the battle of the beans by venturing in trade derivatives, brokering foreign financial investments in China, and raising shareholder value through capital market operations.

As I analyze the prominence of COFCO and Chinatex through distinguished forms of capitalist accumulation, I finally question why did they not affect state politics and discourses around food security during the battle of the beans? To answer this question, one could raise the idea of state-market detachment, pointing out that state power in China is placed above specific capitalist interests, as often depicted by scholarship’s analyses on the Chinese state. However, the contradictory trajectory of the four main Chinese SOEs evidences a rather dynamic and interactive political nexus involving different economic interests in the soybean downstream complex. Accordingly, given Jiusan’s and Sinograin’s political-strategic position in China, they acted to halt COFCO’s and Sinograin’s expansion by pressuring related state institutions to take measures against foreign ownership and price speculation, limiting China’s association with foreign TNCs and further integration into global finance.

In order to contextualise the political reaction of Jiusan and Sinograin during the battle of the beans, the section ‘Food Security and Diverging State-capital Relations’ considers Jessop’s (Citation1990) society-centred approach, which takes the capitalist state as an articulation of forms of power expressed within the broader society. From this perspective, I show how the two SOEs took advantage of new rural bias policies to create semi-official industrial associations under the support of China’s Ministry of Agriculture. They instrumentalized the social discontent over China’s soybean debacle through those associations by allying with processors and farmers (including small households). Jiusan’s and Sinograin’s political articulation alongside the industry’s discontent sectors contributed to an institutional dispute against the Ministry of Commerce, which backed COFCO’s and Chinatex’s economic prominence under a liberal orientation amidst China’s entry into the WTO. In this context, Jiusan and Sinograin endorsed and took advantage of China’s nationalist appeal over food security based on the Sino-foreign dichotomy to undermine the political influence of their state-owned rivals.

Considering the diverging accumulation strategies and power struggle in the soybean downstream complex, I conclude that food security is constantly under scrutiny. Instead of a stagnant discourse, it reflects China’s contradictory state-capital nexuses underpinned by different forms of capital accumulation. It evidences that the state in China entails historically determined social relations, through which institutions and policies reflect diverging capitalist interests and vice-versa. In this sense, the battle of the beans was overall a battle over political power between Chinese conglomerates and related state segments with diverging economic interests. Behind the food security’s nationalist appeal hides the vicissitudes of this intricate ‘battle’.

My analysis is based on 18 months of fieldwork research in China and Brazil between 2018 and 2019 and sporadical data collected up to date. Among all data, this article references interviews with representatives of Chinese enterprises and government officials. It also references corporate internal reports, credit rating reports, as well as relevant information on the industry from official and semi-official statistics. In addition, I considered dozens of newspaper and magazine articles in Chinese, English, and Portuguese, most of which contained dated interviews.

Going out for food security?

It is almost a consensus within the critical literature around China’s agricultural outbound investments that Chinese enterprises overseas carry a high degree of politicisation, in which economic interests accompany strategic goals around food security. As Myers and Guo (Citation2015) point out, increasing Chinese investments in Latin American soybeans follow a diversification of diets in China towards larger protein intakes due to rapid urbanisation, rising incomes, and improved living standards. Although Chinese sourcing overseas is not necessarily bonded to the domestic market demand, they ensure food security by nurturing Chinese-based agribusiness with soybean provision for animal feed and cooking oil. Following a similar approach, Wilkinson, João Wesz, and Maria Lopane (Citation2016) argue that domestic enterprises have adopted a ‘more-than-market’ strategy abroad to meet food security targets. They purchase soybean from Brazilian farmers with orders placed above the market prices. Thereby, China increases its control over global supply chains with costs beyond what would be economically rational.

The analyses described above coincide with Q. Zhang’s and H. Zeng’s (Citation2020) idea of the state in China as a modelling force imposed on agrarian capitalist classes through food security policies and various types of state interventions. It also coincides with the state capitalism paradigm in agrarian studies, which considers a durable and cohesive political dynamic tending to favour large agribusiness under the party/state control. From this paradigm, the state incubates and boosts domestic-based capital accumulation as a way to deliver economic growth and, consequently, preserve the political status-quo (Huchet Citation2006; Huang Citation2008). In this way, Chinese soybean sourcing strategies overseas aim to secure the stability of food supply and price control according to systematic state policies (Lin Citation2017; Belesky and Lawrence Citation2019; Gaudreau Citation2019).

However, Oliveira (Citation2017, Citation2018) presents a more nuanced understanding of the Chinese outbound investments and trade relations. Inspired by critical global ethnography literature and agrarian change conjunctural analyses, he draws on the centrality of individual practices taken by Chinese and Brazilian government agents, agribusinesses professionals, and civil society. In his opinion, rather than automatically abiding by state-guided policies, Chinese investments in Brazil situate specific territorial power relations and associated discourses both locally and globally. Through an actor-centred approach, he draws attention to the diversity and connectivity of each active individual and institution engaged in China’s international expansion.

Chinese investment strategies in Brazil during the battle of the beans lend support to Oliveira’s approach as they deviate from food security targets due to agential specificities. Accordingly, following independent sourcing efforts initially in line with China’s nationalist discourse over food security, COFCO and Chinatex obtained political support to go abroad as soon as China’s Going-out policy (zou chuqu 走出去) was first announced in 1999. They took advantage of the Brazilian Workers Party’s election in 2002 and the consequent tightening of China-Brazil relations to prospect sourcing strategies in the country’s soybean complex. During Hu Jintao’s visit to Brazil in 2004, COFCO opened negotiations with Lula’s government to facilitate the purchase of farmland for soybean plantations (Y. Hu Citation2004). In turn, Chinatex, who had already opened a business office and hired personnel in Brazil, consolidated a partnership with farm cooperatives and trading intermediaries from the Southern Rio Grande do Sul province (Oliveira Citation2017, 93). While Chinatex’s partnership achieved successful results,Footnote2 COFCO showed more interest in merging with China Grains & Oils Group (CGOG), another Chinese SOE with early investments in Brazilian soybean supply. CGOG went to Brazil in the early 2000s and sought trade partnerships with local players. It signed a preferential supply agreement with the French/Brazilian agribusiness group Agrenco in 2004, from which it purchased a considerable number of soybeans (Riveras Citation2005).Footnote3 With its merger in 2006, COFCO integrated CGOG’s soybean trading business with Agrenco.

However, as Oliveira (Citation2018) points out, the battle of the beans ruined early Chinese attempts to establish independent supply channels with local partners. The ABCD treated COFCO and Chinatex with particular hostility in Brazil to maintain their oligopolistic control over soybean exports. They refused to reach supply agreements with Chinese counterparts and imposed financial impediments on any potential Chinese partners from within their commercial network in Brazil (Oliveira Citation2018, 123). As foreign TNCs reinforced their global trade leadership during the Chinese soybean debacle, their boycott of Chinese investments in Brazil became even more effective. In addition to facing foreign animosity, in 2004, China imposed restrictions on contaminated soybeans from the Rio Grande do Sul province, which retarded Chinatex’s shipments and provoked disagreements between them and local cooperatives (Li Citation2010; Oliveira Citation2018, 113). In turn, COFCO’s trading partner Agrenco became the target of a Brazilian corruption investigation in 2008, damaging its reputation and ruining its business (Alves Pintar Citation2013; Freitas Citation2014). As a result, both COFCO’s and Chinatex’s commercial transactions in Brazil collapsed.

Against this background, one might ask how both state trading enterprises relocated themselves in the global soybean supply chain. At first glance, they followed the same fate as other domestic players. After failing to establish independent sourcing in Brazil, trade speculation conducted by foreign TNCs affected COFCO’s and Chinatex’s businesses in China. In 2004, Chinatex, which had prepaid a high price for soybean imports, suffered losses of approximately US$ 15 million due to price volatility (Oliveira Citation2018, 123).Footnote4 Meanwhile, COFCO stated in its annual report that ‘the soaring price of soybean and other raw materials in the first half of 2004 brought great challenges to the Company and had a serious negative impact on the overall performance of the Company’ (COFCO International Annual Report Citation2005). However, as centrally controlled SOEs with a primary role in China’s trade relations, they still had a robust financial capacity to absorb the losses of price fluctuations and fulfil their contracts (Oliveira Citation2018). COFCO’s and Chinatex’s economic resilience proved to be a vote of confidence for foreign TNCs in Brazil. As COFCO’s Chairman Zhou Mingchen (周明臣) – who had led the company's business diversification through several Sino-foreign joint ventures – made clear in an interview to the Chinese 21st Century Business Herald:

Cooperation is based on strength. Through a series of changes in these years, COFCO has continuously strengthened its own business. This should be an important prerequisite for multinational companies to be willing to cooperate with COFCO. (Jin Citation2003)Footnote5

We earned our reputation that year [in 2004] because we fulfilled our contracts and never defaulted, like some other companies … Since then, the big trading companies, the ABCDs, their attitudes changed. They still would not sell directly to many Chinese buyers [in Brazil], but they accepted our challenge to reduce their risk of exposure. (Oliveira Citation2018, 126)

Notwithstanding, even though Oliveira acknowledges that Chinese agricultural investments in Brazil are dynamic and carry diverging economic interests, he does not go deep into its implications on power relations in China. Thereby, Chinese corporate actions in Brazil seem detached from broader processes of capitalism expansion. His analysis on this issue lacks a more accurate depiction of China’s political economy from which food security discourse and policies emanates. In order to fulfil this gap in the literature, the following section examines through the lens of uneven and combined development how the reconfiguration of Chinese investment overseas affected COFCO’s and Chinatex’s accumulation strategies in the Chinese soybean downstream complex.

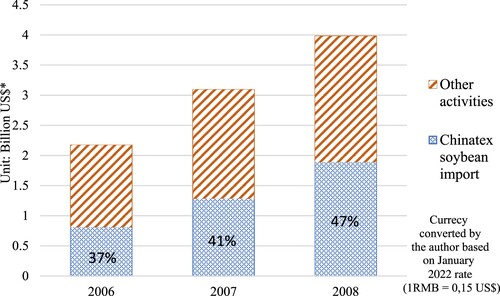

Figure 1. Chinatex’s revenue from soybean imports and other activities. Source: Chinatex Corporation Interim Report (Citation2010); data compiled by the author.

Uneven and combined development highlights how late-industrialising capitalist societies develop in leaps by introducing forms of production and social relations similar to advanced economies while preserving backward social formations.Footnote7 As such, they combine different stages of development through contradictory international capital interactions, producing hybrid and historically unique modalities of capitalism. The concept of uneven and combined development is applied in the Chinese context by scholars such as Rolf (Citation2021) and Peck (Citation2021). Rolf argues that the Chinese recent industrial catch-up incurred profound class ramifications as it went through new geopolitical mediations under global neoliberalism – contrasting with earlier East Asian experiences. In turn, Peck stresses China’s social and economic heterogeneity in light of geographical junctions that have combined free-market economy and socialist market economy. This is the case, he argues, of the ‘Greater Bay Area’, which integrates the globalised cities of Hong Kong and Macao and the technological hubs of Guangdong province, creating hybrid forms of capitalist restructuring.

Following this analytical approach, both scholars stand in line with state analyses that emphasise varied forms of state-capital relations. They oppose dichotomic interpretations of the international political economy drawn upon the world division between liberal versus ‘social-statist’ poles, as often depicted by the literature on Varieties of Capitalism. Instead of a counter-polar alternative to globalising capitalism, China organically interacts with it and reproduces its contradictions within domestic power structures. By examining COFCO’s and Chinatex’s accumulation strategies in the soybean commodity chain, I reinforce the notion of uneven and combined capitalist development in line with their approach, highlighting the agency aspects of sectorial expansion dynamics in China.

Capitalist accumulation integrated to global finance

During the battle of the beans, a wide range of Chinese scholars approached food security by stressing the distinction between Chinese and foreign ownership, in tandem with China’s current reformist ideology. They condemned foreign agribusiness TNCs without questioning the forms of capitalist accumulation (adopted by either those TNCs or domestic conglomerates) in the soybean downstream complex. For instance, Guo Qingbao, the Chief Information Editor of China Oils and Fats magazine, despite being aware of the nuances in China’s agribusiness strategies, never got to question the free soybean trade. He described how the ABCD used speculative trade operations in the Chicago Board of Trade to expand their processing capacity in China while attesting the potential benefits of soybean imports to private processing plants from coastal regions (Q. Guo Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Citation2010). In turn, Li Guoxiang, a vocal scholar of the Institute of Rural Development of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, drew lessons from the Chinese debacle by advocating measures to block foreign-owned oligopolies. At the same time, he believed that foreign investments helped enhance Chinese agribusiness’ modernisation if subject to ‘fair competition’ in China and abroad (Zhuang Citation2009). Other scholars (Li Citation2009; Su Citation2009; Y. Guo Citation2012) placed great emphasis on how to preserve Chinese soybean processing by supporting its vertical integration with other agri-food industrial segments, expanding the large-scale domestic agribusiness (Li Citation2009; Su Citation2009; Y. Guo Citation2012).

By focussing on ownership control, the ‘official’ literature on food security could not entirely grasp the economic and political transformations brought about by COFCO and Chinatex. Accordingly, their subordinated alliance with foreign agribusiness TNCs paved the way for a distinguished financial-driven capitalist expansion in the Chinese soybean downstream complex. The two Chinese enterprises took advantage of preferential trade relations to reproduce mechanisms of price speculation through a deepening global partnership. Therefore, they expanded to the prejudice of most domestic enterprises that relied on a stable soybean supply for processing activities, contradicting China’s food security governance.

Contrary to the official literature’s depiction, COFCO and Chinatex, as primary soybean importers, served as a conduit for foreign investments in China. By partnering with domestic enterprises, foreign agribusiness TNCs gained access to the domestic market through preferential distribution channels, connections with relevant state institutions and local personnel, and Chinese bank credit offers, among other benefits (Breslin Citation2007). COFCO’s and Chinatex’s preferential position in attracting foreign capital, though, was used in favour of an internal group of executives and related government officials to push forward an accumulation strategy that mimicked their foreign counterparts’ investment methods in the soybean downstream complex. For instance, in the late 2000s, COFCO became a minor shareholder of Wilmar International, having five per cent of its shares. Meanwhile, Yu Xubo (于旭波) and Lu Jun (吕军), two of COFCO’s senior executives, integrated the board of directors of Wilmar International and Wilmar Holdings, respectively (Disclosable Transactions Citation2009, 52; Murphy, Burch, and Clapp Citation2012, 41). The exchange of directors, along with a series of joint ventures in the soybean processing sector, allowed the two Chinese state traders to obtain privileged information on trade and avoid risks of world price volatility. As Zhang Dongfeng, the general manager of COFCO’s Oils and Fats Department, said in an interview with the Chinese journal Agricultural Economics in 2010:

Our company’s shareholders [ADM and Wilmar International] are well aware of the supply and demand tendencies and price changes of oilseed crops in the international market, and they can turn their experience and advantages in international trade into advantages for our procurement costs. (Qu Citation2010, 74)Footnote8

Table 1. COFCO’s and Chinatex’s profits.

We suffered losses [in 2004] because we entered into the market too early and bore an enormous hedging scale (…). In 2006 and 2007, though, COFCO saw the whole agricultural futures market tendency correctly and, in the end, was able to make money. (Yu Citation2020)Footnote9

Their [Chinatex’s] strategy is very similar to the way foreign capital enters China. First, they set up trading companies abroad and organize supply sources, and then expand to the downstream of the industrial chain by merging and acquiring processing enterprises. (B. Li Citation2010)Footnote11

In the same way, although losing the major shareholding control of two large joint ventures in 2007, COFCO expanded its processing capacity also in collaboration with foreign agribusiness TNCs.Footnote13 Between 2003 and 2009, the company built/acquired three new soybean crushing plants, one with ADM, one under the direct ownership of COFCO’s subsidiary in the tax haven the British Virgin Islands, and the last one under the major ownership of Well Grace Holdings International, an obscure intermediary financial holding linked to COFCO Hong Kong.Footnote14 The company also upgraded some of the already existing crushing plants it built with agribusiness TNCs, and transferred the newly absorbed plant from CGOG in the southern port of Dongguan to Time Triumph Limited, another Hong Kong financial holding.

Figure 2. Soybean crushing capacity of China’s Top 10 processors. Source: Qichacha [Enterprises Investigation] (Citation2019); and Sublime China Information Database (Citation2018); data compiled by the author.

![Figure 2. Soybean crushing capacity of China’s Top 10 processors. Source: Qichacha [Enterprises Investigation] (Citation2019); and Sublime China Information Database (Citation2018); data compiled by the author.](/cms/asset/993e4826-d2cd-4084-9271-0a5f51ff95ff/fjps_a_2054701_f0002_oc.jpg)

Thus, COFCO and Chinatex and their related state segment contradicted the Chinese nationalistic appeal around food security by establishing an organic association with foreign capital. They expanded by mimicking speculative investments alongside agribusiness TNCs, which jeopardised China’s pursuit for food self-sufficiency – contributing to the exposure of local farmers to foreign competition and leading to the bankruptcy of domestic soybean processors. In line with the concept of uneven and combined development, COFCO’s and Chinatex’s strategy reveals how different levels of integration into the global economy enables heterogeneous forms of capitalist accumulation at home. Instead of a linear historical process, capitalist expansion spurs different production units and forms of accumulation that coexist with each other considering national specificities. In the Chinese context, state planning and state ownership under the communist party’s control, combined with the Sino-foreign association, propelled SOEs like COFCO and Chinatex to expand through deep global financial integration.

Accordingly, while most domestic enterprises relied on stable soybean supply and productive capital investments in processing infrastructure, COFCO and Chinatex expanded side-by-side with transnational agribusiness, submitting soybean processing to the rule of finance. Already in December 2006, Chinatex Planning Institute and the European and American Students Association held the first ‘Chinatex Capital Forum’ to discuss the company’s overseas financing, capital operation, and brand strategy (EASA Citation2006). In the following year, Chinatex headquarters in Beijing entered negotiations for a company-wide merger with Olam, a thriving Singaporean-based agribusiness transnational. Olam was a strong competitor of Chinatex in the cotton trading sector and had plans to diversify into soybean sourcing and processing. Its merger with Chinatex aimed to build an international platform that combined both companies’ cotton imports in China and their soybean processing and trading businesses (Olam Citation2007; cited in Oliveira Citation2017, 97).

As for COFCO, some pro-liberalism executives reached higher corporate positions and promoted further financial-driven reforms. For instance, the futures business expert and a COFCO’s representative at Wilmar’s board of directors, Yu Xubo, became COFCO’s Deputy General Manager in 2000 and General Manager in 2007.Footnote15 In turn, Ning Gaoning (宁高宁), a liberal enthusiast, left the prominent Chinese state trader China Resources to become COFCO’s new Chairman in 2004.Footnote16 At COFCO, Ning was more audacious than the already ‘financial-friendly’ former Chairman Zhou Mingchen.Footnote17 He pushed forward a liberal ideological crusade and gave COFCO’s offshore subsidiaries greater power to grow and open their capital accounts.Footnote18 Accordingly, in 2006, Ning established the new subsidiary China Agri-Industries Holdings Limited (China Agri) and listed it on the Hong Kong stock exchange. China Agri absorbed some of COFCO’s mainland assets and concentrated most of its companies, including COFCO International, which was primarily responsible for COFCO’s soybean processing business. China Agri issued an unprecedented amount of capital stock and contributed to the multiplication of offshore firms,Footnote19 which reached the vast number of 164 in 2013 (General Tax Letter Citation2013).Footnote20

In short, COFCO’s and Chinatex’s expansion during the battle of the beans contradicted the Chinese nationalistic discourse as they carried out a financial-driven accumulation strategy associated with foreign capital. However, to understand the broader implications of this contradiction to China’s food security governance, we should consider its political nexus vis-à-vis other SOEs such as Jiusan and Sinogrian. How did their financial-driven expansion play out as a contradictory aspect of the state in China? Did they affect and were affected by state policies, transforming power relations in the soybean downstream complex? In order to address these questions, the following section investigates the interconnectivity between China’s heterogenic capitalist formation and state-capital relations.

Food security and diverging state-capital relations

Given that, during the battle of the beans, the ‘official’ literature on food security endorsed an uncritical nationalist appeal based on a Sino-foreign dichotomy, one could argue that China’s agrarian capitalist expansion is devoid of political influence. In other words, COFCO’s and Chinatex’s divergent accumulation strategy would not affect and transform state policies regarding food security. However, by analyzing the adaptation and reaction of the state-owned competitors Jiusan and Sinograin, I indicate that Chinese agri-food policymaking is rather mutable and interrelated with inter-capitalist disputes. Their adaptation and reaction follow Jessop’s (Citation1990) society-centred approach, in which the state internalises forms of power and class struggle expressed within the broader society. According to Jessop, capitalist class structures constrain and enable the forms and functions of states without automatically determining them. The state emanates heterogeneous capital accumulation and contradictory class interests. As so, it is prone to rivalry and alliance formations between different fractions of capital that seek the state support through political action for expanding their bases of accumulation.

From this perspective, we can see that due to diverging capitalist class interests acting within the state, COFCO’s and Chinatex’s economic prominence during the battle of the beans did not revert mechanically to a hegemonic form of accumulation. The two state traders contradicted China’s food security governance, though they did not generate alternative discourses and policies. Instead, they faced the political hostility of their state-owned competitors Jiusan and Sinograin, which used food security’s nationalist appeal to hinder any further financial-driven expansion associated with foreign capital.

Accordingly, at first glance, officials in charge of Sinograin and Jiusan and private capitalist partners made clear attempts to adjust their accumulation strategies, moving away from domestic circuits of production and consumption under the strict control of Beijing’s headquarters. In 2007, Sinograin, which had complete ownership control of its soybean processing assets, held talks with Bunge and Louis Dreyfus for joint investment in a crushing facility at the Southern Dongguan port (Q. Guo Citation2008a, 8; World Grain, 12 August 2007). In turn, Jiusan, which until then repudiated offshore tax evasion practices (Wang, Wang, and Wei Citation2013), partnered with the Hong Kong food trading intermediary Xinglong Grains and Oils to invest in two soybean crushing plants in 2004 and 2007.Footnote21 Thereby, the Hong Kong counterpart held the equivalent of 11 per cent of Jiusan’s total soybean processing capacity and facilitated Jiusan’s access to the region’s free trade system and looser tax regulations.

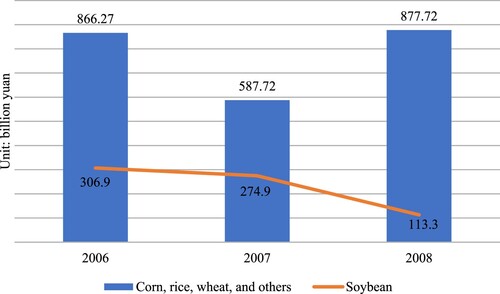

However, Jiusan’s and Sinograin’s strategic political role reduced their room for economic adaptation in response to COFCO’s and Chinatex’s prominence. For instance, Jiusan, as an SOE from China’s leading soybean producer, Heilongjiang Province, and Sinograin, as a manager of the central state grain reserve, had a significant role in the state macroeconomic policy for agricultural supply and price control. As such, they depended on political and economic stability derived from the party/state legitimacy to grow. During the battle of the beans, though, following the crisis of processing enterprises in Northeast China (where Heilongjiang Province is located), Jiusan’s parent company Beidahuang Group dropped its soybean sales drastically (). The shortening of Beidahuang’s supply discouraged local farmers from growing soybean and aggravated, even more, the decline of China’s processing sector. Against this background, to safeguard Heilongjiang’s soybean production, the provincial reserves stockpiled domestic soybeans, and Jiusan purchased them whenever soybean import prices plummeted. Therefore, from June 2004, Jiusan paid one to two cents higher than the market price for each ton of domestically produced ones (Chen Citation2014).

Figure 3. Direct sales of Heilongjiang Beidahuang Agriculture Group’s main agricultural products. Source: Heilongjiang Agriculture Company Limited, cited in M. Zhao and Liang (Citation2009).

Sinograins’ and Jiusan’s limits for economic adaptation propelled related state segments to take political actions against the overflow of imported soybeans into the Chinese market. Officials from Heilongjiang Province made efforts to sustain the domestic production by creating a market niche for non-transgenic soy-food processing in China (interview with Liu, Yingtao, 31 October 2018). Accordingly, in the early 2000s, the central government prohibited the manufacturing of GM soybeans as food ingredients for human consumption – except soybean oil, which is a subproduct of soybean meal production.Footnote22 Thereby, Chinese farmers, who were only allowed to plant non-GM soybeans, gained an exclusive selling market for soy-food processing. Meanwhile, local agribusiness was encouraged to diversify within the tempted market niche. For instance, Jiusan increased its production and sales of powdered phospholipids (a food-item ingredient) and specialised in non-GM soybean oil from domestically produced soybeans (Bu and Jiang Citation2010, 55).

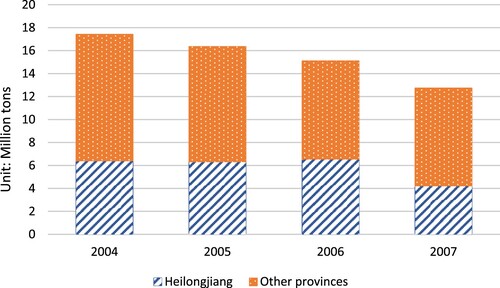

Nevertheless, forming a market niche for domestic non-GM soybeans was not enough to recover the economic burden from the battle of the beans. As Jiusan’s Chairman Tian Renli (田仁礼) noticed in an interview with the Chinese journal Agricultural Economics, China’s soy-food consumption was still very restricted and generated few economic returns compared to soybean meal and soybean oil (Bu and Jiang Citation2010, 56). Besides, foreign agribusiness TNCs launched great investments in processing infrastructure in Northeast China, increasing the competition over non-GM soy-food production (Su Citation2009, 39; Wang Citation2010, 36). As a result, state-owned grain enterprises from Heilongjiang Province, of which Jiusan’s parent company Beidahuang was the biggest by far, had losses of over US$ 86 million in 2007 (China Grain Yearbook Citation2007).Footnote23 Lastly, whereas the new protective policies secured short-term stability of Heilongjiang’s soybean production, between 2006 and 2007, it began to drop again from 6.53 million tons to 4.2 million tons (). Consequently, the disruption of local supply inflated soybean oil prices and generated social chaos. In December 2006, the population of Harbin, Heilongjiang’s capital city, rushed to supermarkets to buy soybean oil before prices could rise again (Jiang Citation2007).

Figure 4. China’s soybean output. Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China (Citation2009); data compiled by the author.

As the social disarray and economic uncertainty put the political legitimacy of related officials at risk, Jiusan had no choice but to adopt a more assertive political approach against the foreign headway (and COFCO’s and Chinatex’s associated expansion) into the Chinese soybean complex. Therefore, even though Jiusan and Sinograin had changeable economic aspirations, their critical political role in China made them radically reactive. For instance, when the Chinese media unveiled the intention of agribusiness TNCs to acquire Jiusan’s soybean processing assets after the first wave of price fluctuations, Jiusan’s Chairman Tian Renli firmly rejected it. As he said to the Open Times Journal:

In fact, the American ADM has long been eyeing us, and then the US Bunge and Cargill have also contacted me. They are interested in my crushing capacity of 15,000 tons per day, but I’m protecting China’s last soybean hub, I am standing firm. (Wang, Wang, and Wei Citation2013)Footnote24

As Jiusan’s claims echoed in the Chinese official media, related state institutions ratified the stance on food security that aimed to stabilise soybean prices and reduce China’s reliance on imports. For instance, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the State Council agency in charge of broad macroeconomic management, held direct talks with Jiusan’s representatives and the representatives of other leading soybean processors. The NDRC also conducted investigations into the soybean crisis, which included several visits to Heilongjiang Province (Cao and Guo Citation2006). Consequently, it proposed measures to improve China’s trade regulations and import logistics. In July 2006, the NDRC encouraged Sinograin to expand the national soybean reserves and integrate provincial level grain reserves (Lin Citation2017, 126). It also suggested the creation of a joint procurement mechanism for importing soybeans composed of several big Chinese agribusinesses – probably including Jiusan and Sinograin (Cao and Guo Citation2006).

As one can imagine though, the NDRC ratification of China’s food security governance exacerbated the disputes between segments of the state represented by enterprises with different accumulation strategies, putting Jiusan and Sinograin on opposite sides of COFCO and Chinatex. A joint procurement mechanism and the strengthening of national soybean reserves threatened COFCO’s and Chinatex’s trade monopoly and capacity to manipulate prices. Therefore, as soon as the NDRC guidelines were approved, disagreements emerged, and industrial insiders attempted to prevent them from coming into effect (Cao and Guo Citation2006).

Amidst increasing rivalry, executives and state officials related to Jiusan and Sinograin took advantage of the nationalistic appeal of China’s official food security discourse to gather political support. They made efforts to build a unitary political platform alongside Chinese enterprises on the edge of bankruptcy. Such efforts translated into the creation of the China Soybean Industry Association (CSIA) in 2007 – a semi-official union of 32 soybean processors, politicians, individuals related to the industry, and scholars (Li Citation2007). Jiusan, its main sponsor, sought state recognition to create the CSIA already in 2003 (Suo Citation2007b). However, it faced the opposition of the Ministry of Commerce, which advocated COFCO’s and Chinatex’s exclusivity over imports and exports (Suo Citation2007b). The Minister Bo Xilai (薄熙来, July 2004 – December 2007), a member of the second generation of CCP cadres, was often depicted as a Maoist orthodox. Even so, his stance in favour of COFCO and Chinatex followed the Ministry’s commitment to liberalise trade in the aftermath of China’s access to the WTO – which most scholars view as a trampoline for Bo to escalate in the party ranks.Footnote26 The China Business Journal well describes Bo’s position:

As the China Soybean Industry Association opposed the erosion of the Chinese market by imported soybeans, COFCO, and the China Chamber of Commerce for Food, Native Produce and Livestock Import and Export of the Ministry of Commerce, which is in charge of soybean imports, naturally stood on the opposite side of the association. (Suo Citation2007a)Footnote27

The introduction of foreign investment in agriculture must adhere to the basic requirements of providing services and ensuring the effective supply of major agricultural products. It must maintain the safety of the domestic agricultural industry and the interests of farmers. (Farm Produce Market Weekly, 21 September Citation2009, 29)Footnote29

The China Soybean Industry Association is the result of a game between various interest groups. Behind it is the dispute between non-GM soybeans and GM soybeans, between Northeast soybean crushers and coastal soybean crushers, and between the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Commerce. (Teng Citation2010, 21)Footnote30

The development of the soybean industry cannot be solved by the Soybean Association alone. It requires the joint attention and efforts of the whole society to form a chess game across the country to deal with the current crisis. (Wang and Huang Citation2009, 44)Footnote32

One could argue that by building broad alliances, Jiusan and Sinograin contributed to bringing China’s food security discourse back to the Maoist style-condemnation of capitalist forms of production in agriculture. However, as they took the lead in those alliances, they imposed their state-led accumulation strategy over elements of the labouring class. Despite making concessions to small farmers, they instrumentalized the social discontent in the favour of large agribusiness. Even though direct subsidies and other beneficial measures alleviated the historical burden on rural China, small households were still progressively played down by capitalist expansion fostered by the state. As it is broadly described within the critical literature, the rising prices of agricultural inputs, the processes of commodification of land, and labour displacement, among other factors, propelled the development of capitalist relations and forms of production to the detriment of rural labour (Yan and Chen Citation2015; Day and Schneider Citation2018). Furthermore, as a way to overcome the soybean crisis, the NDRC approved in 2008 new directives encouraging big soybean processors like Jiusan to merge and acquire smaller ones and integrate into different segments of the soybean complex. As the document states, ‘leading enterprises should be supported so that they can have stronger competitive force and gain more market share’ (Petry and Josh Citation2008, 6).

By instrumentalizing social discontent through broad alliances, state segments related to Jiusan and Sinograin undermined COFCO’s and Chinatex’s political influence. For instance, besides favouring large agribusiness, the NDRC directives drew a clear line against ‘low domestically owned [processing] capacity’ and ‘excess reliance on imported raw materials’ (Petry and Josh Citation2008, 4). The document reinforced some of the policies proposed previously by the Ministry of Agriculture and recommended strengthening state guidance on China’s soybean complex (Q. Guo Citation2008b, 4). Lastly, it promoted the adoption of subsidies for Northeastern soybean processors to purchase domestically produced soybean so that Jiusan, the biggest processor with five plants in the region, would no longer bear alone the burden of China’s soybean crisis (NFSRA Citation2010, 1).Footnote34 The new subsidy policy came alongside the State Council’s approval of a comprehensive programme for Revitalizing Northeast China in August 2009. To this end, a leading group chaired by Premier Wen Jiabao formulated policies to strengthen Northeast grain production through investments in transportation and storage capacity (Zhao and Liang Citation2009, 9).

Therefore, China’s nationalistic appeal over food security suited Jiusan’s and Sinograin’s interests and disciplined COFCO and Chinatex by blocking their financial-driven expansion and association with foreign agribusiness. For instance, China’s National Tax Administration Bureau called for the registration of COFCO’s offshore firms as resident companies of mainland China. From then on, the financial decisions of those firms – such as borrowing, lending, financing, financial risk management – and their corporate management – such as appointment, dismissal and remuneration of directors – would be subjected to the approval of COFCO’s headquarters in Beijing (General Tax Letter Citation2013). In turn, in the late 2000s, Chinatex aborted its plans to merge with Olam, which hindered its process of internationalisation and integration into global finance. The state promotion of domestic ownership would also limit COFCO’s and Chinatex’s association with agribusiness TNCs in the soybean processing sector. From 2009 onwards, all COFCO’s new crushing plants were financed entirely by COFCO Oils and Fats Holdings,Footnote35 and Chinatex ceased negotiations with agribusiness transnationals for joint investments in soybean processing.

Following COFCO’s and Chinatex’s political decline, their investment strategy in Brazil would also become obsolete. With restricted means to develop financial mechanisms for price speculation alongside transnational TNCs, Chinatex obtained continuingly less revenue from soybean trade (). Moreover, both SOEs would shift their sourcing strategy in Brazil towards new attempts to establish independent supply channels for importing soybean. Therefore, a new phase of China’s going-out trajectory would begin, with new players, including Beidahuang, Jiusan’s parent company, prospecting massive investments in farmland acquisition for soybean exports in the late 2000s (Wilkinson, João Wesz, and Maria Lopane Citation2016).Footnote36 This new phase would correspond once again to the official nationalist discourse, in which Chinese enterprises were encouraged to ‘go global to establish a stable and reliable imported supply system and improve the ability to secure domestic food security’ (NDRC Citation2008).Footnote37

Table 2. Source: Wang and Dong (Citation2011); Zhong and Wang (Citation2014); data compiled by the author.

Conclusion

The political and economic disputes between state segments upholding different accumulation strategies in the soybean downstream complex show that China’s food security governance is under constant scrutiny. Instead of invariable policies and discourses corresponding equally to all actors involved, food security is susceptible to dynamic pressures emanating from economic interests and diverging state-capital relations.

During the battle of the beans, the ‘official’ discourse over food security reinforced China’s uncritical nationalist appeal, condemning foreign ownership without questioning the many forms of capital accumulation. By doing so, it neglected COFCO’s and Chinatex’s financial-driven expansion associated with foreign agribusiness TNCs. To understand the peculiar expansion trajectory of these two state traders, I considered Oliveira’s (Oliveira Citation2017, Citation2018) analyses on Chinese agricultural investments in Brazil. Following his argument, I assume that agency factors involving the relations with the ABCD in Brazil in the context of the battle of the beans propelled a shift in COFCO’s and Chinatex’s investments away from food security premisses. Rather than promoting independent soybean sourcing, the two Chinese trading enterprises allied with foreign counterparts to import soybeans with their help from Brazil.

Moreover, addressing the gaps in the related literature, I argue that the Chinese changing outbound investment strategies are closely connected to different forms of capital accumulation at home. Contrary to what is often depicted by the literature on state capitalism, agrarian capitalist expansion in China follows the premisses of uneven and combined development. It reveals itself as heterogenic and, in many ways, conflicting as the domestic economy integrates through different levels into global capitalism while preserving national specificities. This brings new empirical and reflexive scrutiny as agency factors related to diverging state segments provoked mutable and destabilising effects on China’s rural economy. Accordingly, COFCO’s and Chinatex’s association with foreign capital allowed them to take advantage of price speculation mechanisms and subordinate soybean processing activities to the rule of finance. With such a distinguished accumulation strategy, they contributed to the breakdown of China’s soybean farming and processing alongside foreign partners, contradicting China’s nationalist discourse around food security.

However, in line with Jessop’s social-centred approach to state analyses, I argue that China’s heterogeneous capitalist expansion reflects historically determined social relations and class disputes within the state. As such, COFCO’s and Chinatex’s economic prominence depended on the political struggle against diverging capitalist interests, having no automatic effect on the state power. The broad social articulation of state segments related to Jiusan and Sinograin rather hindered the further expansion of speculative financial practices led by their state-owned rivals. Amidst a rurally biased political environment, they upheld stable soybean supply by endorsing China’s food security discourse based on an alleged Sino-foreign dichotomy. Food security’s uncritical nationalist appeal corresponded to their interests as it served as a unifying ideological platform against COFCO’s and Chinatex’s political influence.

As an expression of mutable and contradictory power dynamics in China’s rural economy, the post-battle of the beans’ food security governance must be seen through contextual lenses, constantly susceptible to change. As it is widely known, COFCO regained economic and political centrality by launching massive investments since the mid-2010s in South America. Its business management and operations overseas are highly diversified and are carried by COFCO International, a financial-oriented investment platform associated with multiple foreign investors. Therefore, this case might bring up new inter-capitalist within the state sector disputes and political nexuses that warrant study and discussion (Wesz, Escher, and Fares Citation2021). The distressing effects of COFCO’s rebound on food security policies and the characteristics of its recent international expansion will be analysed by the author in a forthcoming article.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Leandro Vergara-Camus, Tim Pringle, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. The open access to this article was made available through the support of SOAS, University of London.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tomaz Mefano Fares

Tomaz Mefano Fares is a PhD candidate and a Graduate Teaching Assistant in the Department of Development Studies at SOAS, University of London. His research concerns inter-capitalist disputes and political change in the Chinese soybean downstream complex. He participates in an increased scholarly interest in agrarian studies, Chinese studies, critical development studies, and international political economy.

Notes

1 Taking Jiusan as an example, Guo Yanchao, a business magnate, and prominent politician from Henan Province, became its most significant individual investor since the early 2000s and enforced his interests by holding the company’s vice presidency and directorial positions in several subsidiaries. At the same time, Sui Fengfu, the Communist Party secretary in Heilongjiang Provincial State-owned Farms Administrative Bureau and chairman of Jiusan’s parent company Beidahuang obtained 10.4 million yuan (1.6 million US dollars) along with his wife Deng Yongqin, only with bribes, cash, and gifts related mostly to land transfer operations between 2003 and 2014 (China Daily Citation2016; J. Hu Citation2016; Shanghai Daily Citation2015). Meanwhile, Beidahuang has progressively decoupled from the public administration by transferring to the provincial government administrative functions of civil affairs, industry and commerce, and social responsibilities (Gao Citation2018; interview with Liu, Yingtao, 31 October 2018).

2 With the collaboration of its Brazilian partners, Chinatex had delivered direct shipments of 60 thousand tons and 550 thousand tons of raw soybean in 2003 and 2004, respectively (Oliveira Citation2017, 90).

3 From 2004 to 2006, CGOG purchased from Agrenco 400, 120, and 234 thousand tons of soybean each year (Trase Citation2020; Zhang Citation2005).

4 Currency converted by the author based on January 2022 rate (1RMB = 0,15 US$).

5 Translated by the author.

6 Currency converted by the author based on January 2022 rate (1RMB = 0,15 US$).

7 This concept was originally articulated by Leon Trotsky considering the Russian germinal integration into global industrial and financial circuits of capital. It takes capitalist development as an expanding totality of which national economies are a constitutive part (Trotsky Citation2017).

8 Translated by the author

9 Translated by the author.

10 Currency converted by the author based on January 2022 rate (1RMB = 0,15 US$).

11 Translated by the author.

12 Jindou Food Limited Company, Fengyuan Food Company, and Jinshi Biological Protein Technology Company. In all these three acquisitions, Chinatex became the major shareholder.

13 In 2007, Wilmar International acquired all the shares owned by ADM and its affiliated soybean processing enterprises in China, it became the major shareholder of two large joint ventures composed originally by ADM, Wilmar, and COFCO under latter’s control.

14 COFCO’s new crushing plants are Cofco ADM Cereals and Oils Industry (Heze) Co., Xiangrui Cereal & Oil Industry (Jingmen) Co., and Excel Joy (TianJin) Co.

15 In the late 2000s, Yu Xubo also became the director of COFCO Hong Kong and related companies, such as China Agri, COFCO British Virgin Islands, and Wide Smart Holdings (Disclosable Transactions Citation2009).

16 During his time as head of China Resources, Ning promoted the listing of essential subsidiaries like the CR Enterprise. He also associated with foreign financial firms to develop securities businesses and to prospect a new bank in Mainland China (Jie Citation2003, 74). However, due to the company’s internal opposition to his financial-driven strategy, he concluded that ‘China Resources was not familiar and qualified enough for developing financial businesses’ (Zhou Citation2005, 35). As COFCO’s new Chairman, though, Ning Gaoning had enough room to accomplish his goals.

17 As later became public, the former Chairman Zhou Mingchen had a relatively more cautious approach to COFCO’s integration into global finance. After leaving the company, he was elected Member of the Tenth National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. Hence, he made several public statements against China’s rush into stock exchange markets, raising the slogan ‘listing is not fashionable’ (Guo Citation2007).

18 Ning Gaoning recommended COFCO’s employees to read two well-known liberal ‘business manuals’, the ‘Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies’ and ‘Confronting Reality: Doing What Matters to Get Things Right’ (Wei Citation2005). Moreover, during COFCO’s high-level strategy seminars, Ning Gaoning proposed a business model similar to China Resources Group, with integrated business units overseas having a flexible financial strategy (Xiao Citation2006).

19 By the end of 2007, the proportion of minority shares reached 30.66 per cent, part of which belonged to Yu Xubo and Ning Gaoning (China Agri Interim Report Citation2008, 13; Huang, Liu, and Li Citation2008, 4).

20 Most of COFCO’s offshore firms were incorporated in remote locations known as tax havens, such as the British Virgin Islands (84 firms), Samoa (16 firms), and Bermuda (2 firms).

21 The crushing plants are Jiu San Group Tianjin Soya Science and Technology Co., and Huiyu Feed Protein (Fangchenggang) Co.

22 In a personal interview with the author, a senior official of China’s Ministry of Agriculture suggested that the government approval of domestic GM soybean oil is based on the belief that the oil extracted from GM crops does not contain transgenic molecular elements (interview with Chen, Yulin, 12 October 2018).

23 That was three and a half times lower than the average profit of all China’s state-owned grain enterprises, evaluated at around US$24,61 million. All values were calculated by the author based on January 2022 rate (1.00 RMB = 0.15 US Dollars).

24 Translated by the author.

25 Translated by the author.

26 In 2007, Bo Xilai was nominated to the selected group of members of the CCP Politburo and the Mayor of Chongqing Municipality, China’s Western political power hub.

27 Translated by the author.

28 In January 2006, the government abolished most agricultural taxes, ending a historical burden to the rural economy (Day and Schneider Citation2018). In the same year, the CCP raised the slogan of the new socialist countryside, which in essence enhanced social protection to small farmers (Zhao and Liang Citation2009, 7–8).

29 Translated by the author.

30 Translated by the author.

31 For instance, in 2008, after a processing enterprise from Harbin purchased GM soybeans, the Association convened a public forum to block the purchase and spread their concern.

32 Translated by the author.

33 Translated by the author.

34 The state subsidies came into effect in the years 2009 and 2010.

35 COFCO Oils and Fats Holdings established new crushing plants in Huanggang, Jingzhou, and Chaohu.

36 Sinograin also launched investments in trade logistics and encouraged local SOEs with farming and land reclamation experience to seek global sourcing opportunities (Lin Citation2017, 126; Liu Citation2018). It is worth mentioning, though, that most of the new players failed to establish profitable exporting bases in South America due to their focus on traditional (or political-oriented) practices, such as the overreliance on local officials' assistance at host countries, insufficient employment of management teams with local experience and, above all, an exaggerated promotion of farmland acquisitions, which provoked a disproportionate international political reaction (Oliveira Citation2017, 197–286).

37 Translated by the author.

References

- Alves Pintar, Marcos. 2013. “Empresa Pede Reparação Por Abusos Em Operação Da PF [Company Asks for Reparation for Abuses in the Federal Police’s Operation].” Revista Consultor Juridico [Legal Adviser Journal], April 1. https://www.conjur.com.br/2013-abr-01/empresa-reparacao-uniao-abusos-operacao-policia-federal.

- Andreas, Joel. 2008. “Changing Colours in China.” New Left Review 54: 123–152.

- Belesky, Paul, and Geoffrey Lawrence. 2019. “Chinese State Capitalism and Neomercantilism in the Contemporary Food Regime: Contradictions, Continuity and Change.” Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (6): 1119–1141. doi:10.1080/03066150.2018.1450242.

- Bramall, Chris. 2009. Chinese Economic Development. London: Routledge.

- Breslin, Shaun G. 2007. China and the Global Political Economy. International Political Economy Series. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bu, Xiang, and Yunzhang Jiang. 2010. “Jiusan Youzhi de Kunjing [The Dilemma of Jiusan Oils and Fats].” Agriculture Economics 1: 55–58.

- Cao, Haidong, and Fengling Guo. 2006. “Zhengjiu Zhongguo Dadou [Saving Chinese soybeans].” Southern Weekly, August 10. http://news.cctv.com/financial/20060810/103311.shtml.

- CCCPC (Central Committee of the Communist Party of China). 2009. Several Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Promoting Stable Development of Agriculture and Sustained Income Growth of Farmers. http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/jj2021zyyhwj/yhwjhg_26483/201301/t20130129_3209961.htm.

- Chen, Xiaohua, ed. 2014. China Agriculture Statistical Report. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: Zhongguo nongye chubanshe [China Agricultural Publishing House].

- China Agri Annual Report. 2009. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing. China Agri-Industries Holding Limited, stock code: 606. http://www3.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2009/0424/00606_533011/ewf116.pdf.

- China Agri Interim Report. 2008. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing. China Agri-Industries Holding Limited, stock code: 606. https://www1.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2008/0929/ltn20080929315.pdf.

- China Daily. 2016. “Former Heilongjiang Legislator Stands Trial for Corruption.” China Daily, July 28. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-07/28/content_26257975.htm.

- China Grain Yearbook. 2007. Jingji guanli chubanshe [Economic Management Publishing House].

- Chinatex Corporation Interim Report. 2010. Beijing, China: China Lianhe Credit Rating. http://pg.jrj.com.cn/acc/CN_DISC/BOND_NT/2010/05/20/103010724_ls_00000000000002Ws1h.pdf.

- Clever, Jennifer. 2017. China’s Strong Demand for Oilseeds Continues to Drive Record Soybean Imports. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, GAIN Report. No. CH17032.

- COFCO International Annual Report. 2005. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing. COFCO International Limited, stock code: 0506. http://www3.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/SEHK/2005/0414/LTN20050414072.HTM.

- Cui, Jianling, and Shiqi Zeng. 2011. “Huifu Jituan Shangyan ‘San Ji Tiao’ [Hopefull Group Staged ‘Triple Jump’].” Agricultural Products Market 40, 14–15.

- Day, Alexander F., and Mindi Schneider. 2018. “The End of Alternatives? Capitalist Transformation, Rural Activism and the Politics of Possibility in China.” Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (7): 1221–1246. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1386179.

- Ding, Jiping, Jing Huang, and Xiaoping Liu. 2007. COFCO Credit Rating. Beijing: China Lianhe Credit Rating. http://www.lhratings.com/reports/B0164-GSZQ0096-2007.pdf.

- Disclosable Transactions and Continuing Connected Transactions. 2009. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing. China Agri-Industries Holding Limited, stock code: 606. http://www3.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/SEHK/2009/1115/LTN20091115012.pdf.

- EASA (European and American Students Association). 2006. “Youth Committee in the United States Actively Supports the First China Textile Capital Forum.” Overseas-Educated Scholars, December 16.

- Farm Produce Market Weekly. 2009. “Guo Xin Ban Jiu Nongye 60 Nian Fazhan Chengjiu Juxing Fabu Hui [Press Conference on the Achievements of Agricultural Development in the Past 60 Years].” September 21.

- Freitas Jr., Gerson. 2014. “Justiça Paulista Decreta Falência da Agrenco No Brasil [São Paulo Justice Decrees Agrenco’s Bankruptcy in Brazil].” Valor Econômico, November 4. https://valor.globo.com/politica/coluna/tcu-prova-sobrepreco-em-mini-pasadena.ghtml.

- Gallagher, Mary Elizabeth. 2005. Contagious Capitalism: Globalization and the Politics of Labor in China. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gao, Yuyang. 2018. “Beidahuang Bianju: San Zhengbu Zuozhen Zhihui Caizhengbu Luxing Chiziren Zhize [Beidahuang Changes: Treasury Department Takes Command].” Finance Sina, December 18. https://finance.sina.com.cn/chanjing/gsnews/2018-12-18/doc-ihqhqcir7796190.shtml.

- Gaudreau, Matthew. 2019. “Constructing China’s National Food Security: Power, Grain Seed Markets, and the Global Political Economy.” PhD diss., University of Waterloo. http://hdl.handle.net/10012/14816.

- General Tax Letter. 2013. Beijing: China National Tax Administration Bureau, no. 183. https://acc.cn/news/toolbox/1564564767/1537/0/.

- Guo, Fenglin. 2007. “Yangqi Zhengti Shangshi Buneng ‘Yi Hong Er Shang’ [The Whole Listing of Central Enterprises Can’t ‘Rush Forward’].” China Securities Journal, March 5.

- Guo, Qingbao. 2008a. “Dangqian Waizi Zai Hua Zhiwuyou Channeng Fenbu Yan [Research on the distribution of vegetable oil production capacity of foreign capital in China].” China Oils and Fats 33 (3): 1–7.

- Guo, Qingbao. 2008b. “Jie Guochan Dadou Kunju, Fuchi Shipin Dou Huo Geng You Yiyi [To Solve the Predicament of Domestic Soybeans, Supporting Food Beans Is More Meaningful].” China Oils and Fats, September 30. https://xuewen.cnki.net/CCND-LYSC200809300011.html.

- Guo, Qingbao. 2010. “2009 Nian: Zhongguo Langyou Qiye De ‘ABCD’ Meng [2009: The “ABCD” Dream of Chinese Grain and Oil Companies].” China Oils and Fats, January 9. http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/20100115/09477250253.shtml.

- Guo, Yanchun. 2012. “Guochan Dadou Chanyelian Chuzai Bengkui Bianyuan [The domestic soybean industry chain is on the verge of collapse].” China Business Journal 7: 4–5.

- Hu, Junhua. 2016. “Qianren Zhangmenren Langdang Ru Yu, Beidahuang Chongji Shijie Wubai Qiang Luokong [The Former Leader Is Jailed, After Hiting the World’s Top 500, Beidahuang Tumbles].” China Business News, December 22. https://business.sohu.com/20161223/n476701259.shtml.

- Hu, Yu. 2004. “Zhongliang Jituan Jihua Fu Baxi Zhong Dadou [COFCO Plans to Plant Soybean in Brazil].” AgriGoods Herald, September 7.

- Huang, Yasheng. 2008. Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics. Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press.

- Huang, Jing, and Xiaoping Liu. 2010. COFCO Tracking and Rating Report. Beijing: China Lianhe Credit Rating. no. 041. http://www.lhratings.com/reports/B0164-DQZQ0477-GZ2010.pdf.

- Huang, Jing, Xiaoping Liu, and Zhibo Li. 2008. COFCO Credit Rating. Beijing: China Lianhe Credit Rating. http://www.lhratings.com/reports/B0164-DQZQ0277-GZ2008.pdf.

- Huchet, Jean-François. 2006. “The Emergence of Capitalism in China: An Historical Perspective and Its Impact on the Political System.” Social Research 73 (1): 1–26. doi:hal-02536879.

- Jessop, Bob. 1990. State Theory: Putting Capitalist States in Their Place. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Jiang, Longfei. 2007. “Zhongguo Dadou Chanliang Rui Jian Zhi Shiyong Douyou Jiage Meng Zhang [China’s Soybean Production Plummets, Causing Edible Soybean Oil Prices to Soar].” CCTV Economic Half Hour, December 19. http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2007-12-19/000114550485.shtml.

- Jiang, Yunzhang. 2010. “Liangyou Ye Guojin Min Tui Yinxing Dalao Zhong Fang Xianxing [Chinatex: The State Sector Advances Against the Private Economy as an Invisible Gangster].” Jingji Guancha Wang [The Economic Observer], April 2. http://www.eeo.com.cn/2010/0402/166658.shtml.

- Jie, Ling. 2003. “Huarun De Jinrong Weikou [China Resources’ Financial Appetite].” China Investment 5: 73–75.

- Jin, Cheng. 2003. “Zhou Mingchen: Kuaguo Gongsi Bu Yiding Fei Yao Ziji Duzi Qu Zuo [Zhou Mingchen: Multinational Companies Don’t Have to Do It Alone].” 21st Century Business Herald, December 29. http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/20031227/0857580077.shtml.

- Li, Lei. 2007. “Fazhan Dadou Chanye Xu Geng Shenru Liyong Ziben Shichang [The Development of Soybean Industry Requires Deeper Use of Capital Market].” Futures Daily, March 28. http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_59d6233601009wlz.html.

- Li, Xinhua. 2009. “Woguo De Dadou Jiagong Ye [China’s Soybean Processing Industry].” Xin Nongye [New Agriculture] 1: 11–12.

- Li, Bin. 2010. “Xin Mai You Liangzhong Fang Jituan: Dadou Yazha Jiagong Nengli Ju Di San Wei [The New Oil Salesman Chinatex Becomes the Third Largest Soybean Processor].” China Business News, July 3. http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/20100703/09058227805.shtml.

- Li, Wenxue. 2013. “Heilongjiang Dadou Xie Chuan Hui Cheng Jinkou Dadou Yu Zhongliu Gaodu Xiangguan [Heilongjiang Soybean Association Said That Imported Soybeans are Highly Related to Tumours].” CCTV Broadcast, June 21. http://tv.cctv.com/2013/06/22/VIDE1371862082439927.shtml.

- Lin, Scott Y. 2017. “State Capitalism and Chinese Food Security Governance.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 18 (1): 106–138. doi:10.1017/S1468109916000335.

- Liu, Hui. 2018. “Woguo Dadou Jinkou Duoyuan Hua Geju Yijing Xingcheng [China Diversifies its Soybean Imports].” Heilongjiang Grain 8: 18–19.

- McCorriston, Steve, and Donald MacLaren. 2010. “The Trade and Welfare Effects of State Trading in China with Reference to COFCO.” World Economy 33 (4): 615–632. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01237.x.

- MOA (Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China). 2007. Guowuyuan Bangong Ting Guanyu Cujin Youliao Shengchan Fazhan De Yijian [Opinions of the State Council on the Promotion of Oilseed Crop Production]. State Office no. 59. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2007-09/24/content_760094.htm.

- MOA (Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China). 2009. Dadou Chanye Fazhan Jizhi Chuangxin Shidian Gongzuo Fangan [Plans for Piloting Institutional Innovation for the Development of the Soybean Industry]. Document no. 7. http://finance.sina.com.cn/money/future/20090514/11306225224.shtml.

- Murphy, Sophia, David Burch, and Jennifer Clapp. 2012. Cereal Secrets: The World’s Largest Commodity Traders and Global Trends in Agriculture. Oxford: Oxfam Research.

- Myers, Margaret, and Jie Guo. 2015. “China’s Agricultural Investment in Latin America – a Critical Assessment.” Inter-American Dialogue Report Series. The Dialogue - Leadership for the Americas. https://www.thedialogue.org/analysis/chinas-agricultural-investment-in-latin-america/.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2009. Agricultural Statistics in the 30 Years of Reform and Opening Up. Beijing: China Statistics Press.

- NDRC (National Development and Reform Commission). 2008. “Guojia Liangshi Anquan Zhong Changqi Guihua Gangyao (2008-2020 Nian) [The Medium and Long-Term Framework Plan for National Food Security (2008–20)].” Xinhua News Agency, November 13. http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/chn156532.pdf.

- NFSRA (National Food and Strategic Reserves Administration). 2010. Liangshi Ju Gongbu Naru Butie Fanwei Dongbei Dadou Yazha Qiye Mingdan [Announced the List of Northeast Soybean Crushing Enterprises Included in the Subsidy Program]. Beijing: The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, January 14. http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2010-01/14/content_1510223.htm.

- Nogueira, Isabela, and Hao Qi. 2018. “The State and Domestic Capitalists in China’s Economic Transition: From Great Compromise to Strained Alliance.” Critical Asian Studies 51 (4): 558–578. doi:10.1080/14672715.2019.1665469.

- Olam. 2007. “Olam International (‘Olam’) and Chinatex Corporation (‘Chinatex’) Announce their Intention to Form Two Joint Ventures in the Oilseeds and Cotton Businesses in China.” Olam International News Release, February 7. https://www.olamgroup.com/content/dam/olamgroup/files/uploads/2011/12/20070207_release.pdf.

- Oliveira, Gustavo. 2017. “The South-South Question: Transforming Brazil-China Agroindustrial Partnerships.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley.

- Oliveira, Gustavo de L. T. 2018. “The Battle of the Beans: How Direct Brazil-China Soybean Trade was Stillborn in 2004.” Journal of Latin American Geography 17 (2): 113–139. doi:10.1353/lag.2018.0024.

- Oliveira, Gustavo de L. T., and Mindi Schneider. 2016. “The Politics of Flexing Soybeans: China, Brazil and Global Agroindustrial Restructuring.” Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (1): 167–194. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.993625.

- Peck, Jamie. 2021. “On Capitalism’s Cusp.” Area Development and Policy 6 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1080/23792949.2020.1866996.

- Petry, Mark, and O’Rear Josh. 2008. New Oilseed Industrial Policy 2008. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, GAIN Report. No. CH8084. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gainfiles/200810/146296095.pdf.

- Qichacha [Enterprises Investigation]. Online Database. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.qichacha.com/.