ABSTRACT

The central Appalachian coalfields have become a major site of carbon forestry offsets on California's carbon market. I use these coalfields as a vantage point from which to examine the emerging dynamics of climate change and rentier capitalism in the rural Global North. Studying one valley on the Kentucky-Tennessee border where coal mining has largely ended, I document how emergent land uses take the form of rentier capitalism. I conclude that rentier dynamics articulated with deindustrialization have created the conditions for right-wing populism to emerge, in part in response to the experience of becoming ‘surplus population,’ drawing upon Tania Li's framework.

Introduction

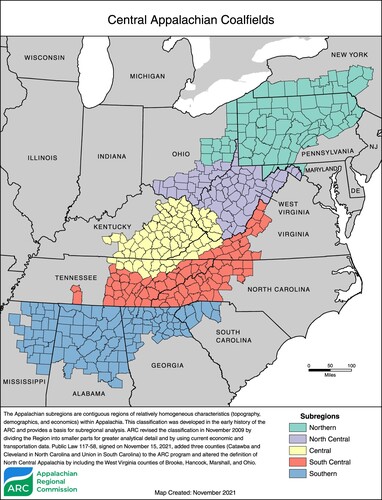

The central Appalachian coalfields have become a major site of carbon offsets on California’s carbon market. Spanning from southern West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, southwest Virginia, to northeast Tennessee, the historic coalfields (see ) are now home to the second-largest concentration of Improved Forestry Management (IFM) offsets outside of California (after Alaska) (California Air Resources Board Citation2019). Appalachian carbon offset project managers argue that offsets not only provide good return on investment but provide wide social benefits. Researchers have recently documented that many climate investing projects fail in such goals: market-driven climate change mitigation and adaptation schemes remain largely symbolic, failing to create emissions reductions, to generate social benefit, and to turn a profit (Bigger and Carton Citation2020; Bigger and Millington Citation2020). Much of this research, however, has originated from an analysis of urban space (green bonds, etc.) (for exception see Kay Citation2018).

Figure 1. Map of the Central Appalachian region, as defined and mapped by the Appalachian Regional Commission. The coalfields closely map onto the central sub-region.

Carbon offsets and climate finance in rural Appalachia, on the other hand, are big business. Estimating average prices per-offset from the California market alone,Footnote1 Central Appalachian landowners have netted at least several hundred million dollars from offset sales in the last five years (California Air Resources Board Citation2019). While the costs associated with certifying the offsets are not insignificant, the offsets can continue paying out over time and the long-term labor costs are very low.

IFM offsets are a recent addition to the Appalachian landscape. In 2013, the state of California implemented a carbon dioxide emissions ‘cap-and-trade’ program, a policy that requires large industrial polluters in California (utility companies, oil companies etc.) to reduce emissions by a set amount per year. If a polluter does not meet their emissions targets, they can either purchase credits from another polluter that had reduced emissions below their target, or they can purchase up to eight percent of their target reductions from offsets. Offsets provide emission reductions from actors outside of the carbon market, however, California’s law only allows offsets projects to originate from within the United States at present (Hsia-Kiung and Morehouse Citation2015). Since 2014, carbon offsets and other climate change mitigation measures have provided sizeable new sources of rent for large corporate landlords in the Appalachian coalfields.

Rent is distinct from other revenue because it is, ‘income derived from the ownership, possession or control of scarce assets … ’ (Christophers Citation2019, 6). Understood as such, rents rely on very little labor, or workers, at least in the rentier portion of an economy.

The central Appalachian coalfields offer one vantage point from which to examine the emerging dynamics of climate change and rentier capitalism in the rural Global North. Although climate change mitigation politics may appear to be liberatory, such climate measures in Appalachia are deepening forms of disinvestment and corporate value extraction. I find evidence for this trend in one former coal mining valley that straddles the Kentucky-Tennessee border, the Clearfork Valley. In this valley, two simultaneous processes are playing out. First, deindustrialization leads to novel processes of disinvestment. Second, in this context, climate change investments and other emergent land uses take the form of rentier capitalism. I conclude that rentier dynamics articulated with deindustrialization have created the conditions for Right-wing populism to emerge, in part in response to the experience of becoming ‘surplus population,’ to use Tania Li’s framing (Li Citation2010).

To make this argument, I trace land use and landownership changes in the Clearfork Valley and I study the effects of these transformations for people in this area. The Clearfork Valley was also the site of John Gaventa’s germinal study, Power and Powerless: Rebellion and Quiescence in an Appalachian Valley (1982), a helpful point of comparison to the present situation. Dynamics in this valley can provide useful insights into the political economy of the region for two key reasons. First, the last coal mines in this area shuttered in 2020, making the area emblematic of the region’s energy transition. Across Appalachia, this transition is well underway. Region-wide coal production and employment have fallen by over forty percent between 2010 and 2020 (Energy Information Agency Citation2019). Second, in 2019, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the world’s wealthiest environmental organization, purchased nearly all the forested land in this valley. The purchase was part of a half-a-million-acre purchase and market-driven climate change mitigation project that spans the Tennessee, Virginia, and Kentucky coalfields. TNC will continue fossil fuel extraction leases on these lands, including gas leasing in the Clearfork Valley, because they claim they cannot break existing lease agreements with fossil fuel companies. Rather than reducing emissions from fossil fuels, TNC aims to reduce emissions through IFM (improved forestry management): increasing the amount of carbon stored in trees that are destined for the timber industry. However, more than just increasing the amount of carbon stored in trees, TNC promises the land deal will support ‘a wide variety of jobs,’ and ‘increase value to local communities’ (Tingley Citation2021, np). These promises are intimately connected to the decline of the coal industry, as TNC and other investors position their investments as supporting the region’s economic transition.

Asking what the effects of emergent climate forest governance regimes are for people living in these forests, I bring a critical agrarian studies approach (Edelman and Wolford Citation2017) to investigate land use change and the making ‘surplus’ of much of this population. I draw on fourteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in the Clearfork Valley and over fifty interviews with economic development planners and activists for this analysis.

The research findings contribute to the study of capitalism and climate change in the rural world in two ways. First, I find evidence to support Marxian geographic scholarship that posits that rentierism relies on enclosure to generate value (Felli Citation2014; Kay Citation2017; Citation2018; Karakilic Citation2022). In this Appalachian valley, climate mitigation rents, or what I term climate rentierism, constitutes a new enclosure of coalfield forests, while other rentier practices, such as leasing the land for recreation, further enclose forests. Yet, these enclosures do not alter the livelihoods of most of the people living in the rentier landscape. Climate change mitigation enclosures build upon ongoing processes of uneven deindustrialization to deepen existing inequalities. New processes of rent seeking, such as climate rentierism, may rely on enclosures to extract value, but that value may not necessarily originate from the people living in the rentier landscape. My second contribution, therefore, is to point to the ways that rentierism renders people living in rentier landscapes ‘surplus’ and extraneous to processes of value generation. Much of the literature on rentier capitalism has focused on theoretical political economy, with little of it investigating how rentier dynamics affect everyday conditions of human life and the wellbeing of people. I add to this literature with an analysis of the effects of rentier dynamics for people living in the coalfields.

As a contribution to the forum on climate change and agrarian struggles, I respond to provocations in the recent essay in this journal on the subject (Borras et al. Citation2022). Borras et al. (Citation2022) ask how climate change differs from other environmental exclusions in agrarian environments; how climate change affects trajectories of accumulation in the rural world; and how rural struggles mobilize in the context of climate change and amid authoritarian populist politics. I address these timely questions in three ways: first, I detail how climate change mitigation efforts in the rural Global North mimic and deepen already existing processes of exclusion, reproducing existing trajectories of rentierism, if also providing novel sites of accumulation. Second, as indicated, I suggest that climate rentierism helps produce the conditions for authoritarian populist sentiments to emerge. And third, in this context, I suggest that other politics are possible, presenting possible places to look to consider the future of rural politics in Appalachia and beyond.

In what follows, I first discuss political economic theories of rent, rentierism, and so-called ‘surplus population’. Second, I detail how climate investing becomes enrolled in rentier capitalism in the coalfields, a process that has accompanied uneven deindustrialization. Third, I detail how people living in this Appalachian valley experience the effects of emergent rentierism. I then point to the ways that a deepening of inequality stokes ‘rural resentment’ (Cramer Citation2016) of perceived unevenness in wealth and prosperity, suggesting how such sentiments play into the politics of right-wing populism in rural America. I conclude with a brief examination of other politics that offer possibilities to reorient political alliances in the current moment, and, perhaps, ‘erode capitalism’ (Wright Citation2017) in rural North America.

Climate change and rentier capitalism

Some political economists argue that carbon crediting, offset schemes, and climate-driven conservation easements are novel forms of rent (Felli Citation2014; Kay Citation2017). Studies of climate rents are a piece of recent geographic scholarship that has theorized the political economy of rentierism, rentier capitalism, and financialization (A. Gunnoe Citation2014; Kay Citation2017; Christophers Citation2019, Citation2020; Karakilic Citation2022).

The effects of rentier capitalism for people living in rentier landscapes, however, has received less explicit attention. Paying attention to the effects of rentier capitalism in Appalachia is important because such scholarship can provide the basis to consider the articulation of political economic transformation and people’s political dispositions. Such an analysis helps explain the relationship between rentierism and right-wing populism in Appalachia.

That Appalachia is a rentier landscape has been well documented: in some counties in coal country, land companies own upwards of eighty to ninety percent of total land (Appalachian Land Ownership Task Force Citation1979). In the 1970s, researchers first documented these dynamics as central to the coal industry’s control of the political economy in the region. Dynamics in the Clearfork Valley helped spurr the Land Ownership Task Force to study the dynamics of ‘absentee landowners,’ an outcome of John Gaventa’s study of the valley (Citation1982). In 2013, a group of researchers based out of the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy conducted a similar study on West Virginia, finding that concentrations of corporate land ownership had stayed relatively constant (Spence et al. Citation2013). Finer-grained studies of land ownership continue to reveal deepening rentier dynamics, documenting ongoing evictions in southern West Virginia as land companies find tenants to be irrelevant and a nuisance to a rent seeking model (Appalachian Land Study Citation2022).

Changes in land use and land ownership indicate that the collapse of the coal industry is producing a ‘rent gap’ (Smith Citation1979; Citation1996; Darling Citation2005). As the price of land and mineral assets fall or slow in growth, investors find new opportunities to purchase land and seek new forms of rent. This new rentierism mirrors processes of financialization of land that geographers have documented across North American resource extraction landscapes and timberlands (A. Gunnoe Citation2014; Kay Citation2017; Fairbairn Citation2020).

‘Climate rents’ feed into a new rentierism in the coalfields, a rentierism that has largely left the people in the region without work and with diminishing investments in basic infrastructure. Recent debates about rent and rentierism (Felli Citation2014; Kay Citation2017; Christophers Citation2020; Karakilic Citation2022) highlight how Global North economies increasingly rely on rentierism, as all sectors of the corporate world increasingly monopolize and lease access to scarce assets (e.g. intellectual property, platforms, land etc.) (Christophers Citation2019; Citation2020). Marxist geographers have added that not only does rentier capitalism entail monopolization, privatization, and deregulation (products of neoliberal politics), but it also consistently relies upon the enclosure of commons, or commonly accessible resources (A. Gunnoe Citation2014; Kay Citation2017; Karakilic Citation2022).

In North America, these enclosures have accompanied the financialization of land (e.g. Fairbairn Citation2020). For instance, Kelly Kay’s study of Maine timberlands deftly shows how new ‘investor-owners’ threaten to destroy forests that are vital for the tourist industry as a way to increase financial rents, forcing local communities reliant on the tourist industry to pay for conservation easements (Kay Citation2017). Kay demonstrates how rent seeking involves obstruction of access to the ‘necessary conditions of production,’ drawing on the work of Romain Felli (Citation2014, 269) to show that the privatization of nature has relied on obstructing access to aspects of the landscape.

The rentierization of North Atlantic economies, and Appalachia in particular, has accompanied processes of deindustrialization (Winant Citation2021). Disinvestment has ‘hollowed out’ rural communities across the United States: industrial employment all-but disappeared, public social infrastructure has been widely abandoned, and people with education, skills, and capital continue to look for better opportunities in cities (Carr and Kefalas Citation2010; Edelman Citation2021). In Appalachia, mines mechanized, and then shuttered. The timber industry has taken a similar trajectory, as has manufacturing, which saw growth from the 1970s through the 1990s as plants relocated to southern, less union friendly geographies, only to relocate again offshore in the 2000s (Eller Citation2008). The growth and decline of data and service oriented companies (e.g. data and call centers) also followed similar trends from the 1990s through the 2000s (Oberhauser Citation1993; Maggard Citation1994).

Without industries providing a tax base, funding for schools, roads, water systems, and public services have evaporated. As work becomes scarce and government does not invest in infrastructure (what might otherwise create the conditions for higher quality of life or more diverse economic growth), many people have left deindustrializing communities (Kratzer Citation2015).

Deindustrialization renders those people that have stayed in Appalachia ‘surplus population.’ Tania Li defines the term, following Marx’s ‘relative surplus population,’ as people who are not needed for capital accumulation. Li details that there is a growing body of rural poor who have nowhere to go, dispossessed of land or livelihood when new production regimes displace former livelihoods and offer few jobs in return (Li Citation2014; Citation2017). The author estimates there are a billion people on the planet whose ‘predicament is that their labor is surplus in relation to its utility for capital’ (Li Citation2010, 68). Teleological narratives of development offer, ‘the assumption that all these surplus people would find somewhere else to go, and something else to do’ (Li Citation2017, 1250), moving to cities or other jobs. In a world of increasingly deindustrializing cities, however, many people return or stay in the countryside despite dire conditions of poverty. Li draws on the Foucauldian concept of biopolitics to consider state responses to this ‘surplus population’ of poor and underemployed people in the countryside, biopolitical responses to either ‘make live’ or ‘let die’ (Li Citation2010).

The central Appalachian coalfields exemplify Li’s thesis. Many people live without jobs, ‘surplus’ to the needs of capital, in deeply precarious situations, facing poverty, depression, disease, and despair. On average, less than sixty percent of adults aged eighteen to sixty-five participated in coalfield counties’ workforce between 2015–2019, with some counties having lower than forty percent participation rates (Pollard and Jacobsen Citation2021, 87). The coalfields have some of the lowest and most rapidly falling life expectancies in North America. Compared to the US, ‘the region’s deficit in life expectancy increased from 0.6 years in 1990–1992 to 2.4 years in 2009–2013’ (Singh, Kogan, and Slifkin Citation2017, 1423). People under the age of sixty-five face disproportionately high rates of premature death from poverty and disease, namely addiction, suicide, and overdose deaths compared to the United States (Rigg, Monnat, and Chavez Citation2018; Cooper et al. Citation2020; Meit et al. Citation2020). An epicenter of the opioid epidemic, many people in the coalfields struggle with opioid addiction and often become entangled in the criminal justice system because of drug criminalization (Ray Citation2021). This is a decidedly ‘let die’ biopolitics.

With few public resources available for people to sustain themselves outside of jobs, many have turned to federal disability benefits, Social Security Insurance, as one of the only sources of consistent long-term cash benefits in the United States. Whereas the national average for disability benefits from 2015–2019 was ten percent, coalfield counties in central Appalachia have on average higher than twenty percent of the population age eighteen to sixty-four receiving payments for a disability (Pollard and Jacobsen Citation2021, 154). Perhaps even more telling about dynamics of ‘surplus population,’ disproportionate rates of disability benefits extend to children, with seven percent or higher of children in the central Appalachian coalfield counties receiving disability insurance, while the national average was below three percent between 2015 and 2019 (Pollard and Jacobsen Citation2021, 155). While disability benefits for adults can be partial or due to work related injury, disability in children indicates a life-long inability to work. Clearly, many parents find that, under conditions of poverty and deindustrialization, their children are unlikely to find gainful work for a multitude of reasons. As Alan Maimon points out, disability benefits in coalfield Appalachia are a measure of injury, sickness, and the mental health effects of chronic poverty, as well as a measure of people who have given up the hope of ever working given economic and personal circumstances (Maimon Citation2021).

Rentierism in Appalachia, in the context of deindustrialization, increasingly renders people surplus to capital accumulation. As I conclude, these effects of deindustrialization and deepening rentier relations are intimately tied to emergent ‘rural resentment’-driven right-wing populism.

Climate rentierism and enclosures

In the following section, I detail how climate investments offer a business-as-usual approach to forest management, deepening dynamics of rentier capitalism in the coalfields. This deepening of rentier dynamics largely leaves local communities out of the distribution of economic benefit and leaves people increasingly irrelevant to the economic logic.

Corporate and non-profit spokespeople involved with novel climate change mitigation investments in the coalfields, which TNC’s land deals typify, are steadfast in their conviction that the marketization of nature can both mitigate climate change and create social goods. TNC wrote in a job advertisement for a staff person for this new project: ‘Our vision is based on the conviction that capital markets, businesses and governments must invest in nature as the long-term capital stock of a sustainable, equitable and more efficient economy’ (The Nature Conservancy Citation2021, np). TNC land managers are convinced that these land deals will support community desires for economic development in the collapse of the coal industry. As one staff person explained the goals in starting the project: ‘the big overarching goal was how do we manage these properties in a way that support localities, tied to local communities’ goals and vision through economic diversification in the wake of the decline in the coal industry’ (Interview with non-profit staff. Phone. September 17, 2021). TNC sees their role as maintaining ‘working forests’ and supporting jobs in a more sustainable timber industry, leasing land for more recreational uses, and protecting lands for conservation.

Interviews with residents near the Cumberland Forest Project, TNC’s name for the half-million-acre purchase, however, indicate that these strategies for jobs and community development investment overlook the ways that carbon offset, conservation easement, and recreational leasing programs deepen existing inequalities in the region. What TNC terms community benefits, many in the community understand as business-as-usual.

In fact, TNC’s social benefits are so opaque that none of my interviewees in the areas surrounding the Cumberland Forest Project knew that TNC had purchased the property three years prior. That community members are largely unaware of TNC’s project indicates that the project has largely unaffected their lives, in part because the project resembles the rest of the landscape. Across multiple interviews, Clearfork Valley residents said that little had changed in terms of economic conditions in recent years. Not only were people unaware that TNC purchased the land bordering their homes; multiple people told me that the land was owned by either Chinese companies or, as one informant stated, ‘I heard it was all owned by some Japanese company’ (Fieldnotes. January 7th, 2022), neither of which is true for nearby properties. A Chinese firm had, in fact, purchased a local coal company and attendant mineral rights a decade earlier (Boling Citation2012), however, their last mining operations had shuttered in 2020.

TNC’s land deal exemplifies the financialized investments schemes that control much of the coalfield forests. TNC used a corporation they started called NatureVest to acquire the property, raising ‘green’ venture capital to finance the purchase. NatureVest brings together investors that hope to see large returns on their investments, rather than see these lands in conservation for perpetuity or to predominantly derive rent from timber production. NatureVest intends to sell the property in several years, promising sizeable earnings in the sales price for the investors (Personal correspondence. Email. July 15th, 2020). This format mirrors for-profit financialized timber investment operations that dominate the industry in North America, known at Timber Investment Management Organizations (TIMOs) (Gunnoe and Gellert Citation2011; Gunnoe, Bailey, and Ameyaw Citation2018).

As a TIMO-like model, TNC’s project joins the region’s rentier economy. Gunnoe (Citation2014) illustrates how financialization of timberlands in the United States has ushered in a new kind of rentierism, one where investors aim to extract rents not simply from timber production, but the inflation of the prices of the timberland holdings. Kelly Kay also illustrates this point, noting that the investor-owners of TIMOs are looking for new sources of rent, such as conservation easements, to increase shareholder value outside of timber production (Citation2017).

TNC’s project follows this same model. As a TNC staff person familiar with the project explained,

the limited partnership [NatureVest] is set up much like other timber-oriented investment funds and so it's not meant to be a forever situation … we think plus or minus 10–12 years, we'll need to eventually sell the property. Okay. But before, before we do that, we're going to work to put permanent legal conservation easements in place on as much of the properties as we can. (Interview with the Nature Conservancy staff. Phone. September 17, 2021)

In line with a rentier model for shareholder value, the Cumberland Forest Project is pioneering new sources of rent through both carbon offsets and recreational leasing. What is striking about these new rents is not simply their closure of forest access for nearby communities. Rather, these new rent sources require drastically less local labor or community involvement than resource extraction or other tourist economies. For instance, the carbon offsets on the TNC land derive value from corporations and workers in California, not from the labor or presence of people in Tennessee or Kentucky.

This climate rentierism is not limited to TNC. Many Appalachian land companies and actors the timber industry are getting into offset rents. Business and finance reports indicate that TIMOs have picked up on the trend as a low-cost way to get rent out of forests while still being able to extract timber lease income. Dick Kempka, a spokesperson for Molpus Woodland, a TIMO that owns substantial holdings in the Appalachian coalfields, was quoted in the Wall Street Journal, ‘We're seeing more and more value from having the trees stay there longer’ (Dezember Citation2020, np). This value comes from carbon offset rents derived in California, as essentially a tax on California polluters, presumably passed on to workers and surrounding communities. To understand the financial scope of these projects, the carbon offset deals on the Cumberland Project lands, although financial details are undisclosed, received at least $80 million dollars from California polluters.Footnote2

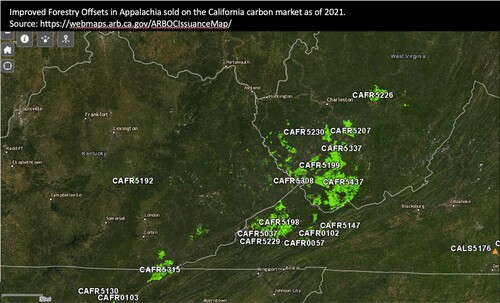

Despite recent research that indicates improved forestry offsets are over-credited for the carbon they mitigate (Badgley et al. Citation2022), carbon forest offsets are a growing trend across West Virginia, Virginia and Tennessee coalfield counties. IFM offsets comprised 17,880,708 issued offsets in the Central Appalachian coalfields as of 2019 (California Air Resources Board Citation2019, 18), with the potential for market expansion. As reports on the industry note, land companies in the region are turning to carbon offsets as part of their new revenue strategies at a moment when coal revenue is in free-fall and they have witnessed stagnation in hardwood timber prices during the COVID-19 pandemic (despite refined lumber prices sky-rocketing) (Dezember Citation2020; Zhang and Stottlemyer Citation2021).

The map below, , shows the extent of coalfield forests already sold on California’s offset market as of 2020, data that leaves out any carbon offsets sold on numerous voluntary markets.

Figure 2. Map of IFM carbon offsets in Central Appalachia that have been sold on the California carbon market as of 2021.

Enclosure I: climate rentierism

What are the implications of landownership and land use changes for people living in these forests? Here I argue that climate investing and other rentier activities limit the community’s access to forests. I note, however, that most of the effects of climate rentierism largely go unnoticed and unfelt. Carbon offset and conservation economies do not fundamentally alter conditions of employment or livelihood for people in these communities. These new rentier activities do, however, continue to alienate people from local economic activity. Yet, rather than express resentment or anger at rentier corporations, people express more general nostalgia and grievance about current conditions of life in their communities.

Before I consider some of these sentiments, I first examine the ways that climate mitigation investments enclose forest access regimes. Will Bowling, TNC’s Central Appalachian Projects Director for Kentucky told TNC’s magazine, ‘that the plan is not to lock people out of the land, but to prove that conservation can be an economic driver’ (Elliston Citation2019, np). Yet, based on interviews with people living around the forest, TNC’s investments deepen on-going trends to make lands accessible to tourists, not residents, and they do not drive increased jobs or business growth in the Clearfork Valley.

The new carbon offsets join a decades long process of deindustrialization and professionalization of the timber industry in this region. TNC’s promise of forestry jobs will likely go to sustainably certified timber management corporations and companies that can conduct carbon accounting on these lands. For small-scale loggers living in the Clearfork Valley and operating with little capital, the new forestry regime means less work. Loggers in the Clearfork Valley said in multiple interviews that many of the small owner-operator mills had closed recently (Fieldnotes. February 7, 2022). Others explained that jobs were declining. In one logger’s telling, new restrictions made companies cut less, and he speculated that the local operators were getting fewer contracts too (Interview with coalfield resident. Eagan, TN. February 15, 2022). While the logging industry employment in the coalfields has been marginal in recent decades, employing few people in extraction while most of the wood products manufacturing occurs elsewhere, the move towards sustainable forestry management further limits the amount of work that residents living near these forests will see. These investments may create jobs in the wider region, however, many of them will be higher skilled and higher educated jobs. Timber firms now must hire consultants to count carbon stored in the trees and practice stainable forestry methods, the proof of which often requires certifications and the presences of degree-holding foresters. Such jobs will likely not reach many people in the communities closest to the forests since many of those people have low levels of educational attainment.

Enclosure II: recreational rents

In addition to the new forestry regime, many people in the Clearfork Valley complain about enclosures that occur because landowners, witnessing the decline of coal rents, have leased land to state wildlife and recreation agencies. These public agencies administer the lands as fee-to-access hunting and recreation lands. People living in the forests, again, do not express anger towards the rentier corporations, but instead towards the government bodies that now police their access of forests. While such recreational leasing predates TNC’s new land management regime, the Cumberland Forest Project highlights the implication of recreational leasing.

Recreational leasing in the Clearfork Valley began in 2014. The then major landholder, Molpus Woodlands Group, leased their holdings to the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) as hunting land, making it a Wildlife Management Area (WMA). While publicly this deal was heralded as making more land publicly accessible, for residents of the valley it was just the opposite.

Across coalfield Appalachia there is a long history of people relying on forest access to collect non-timber forest products for sale (e.g. ginseng); hunting; collecting fuelwood to defray utility bills; and recreation that is a key part of identity (Hufford Citation1993; Citation2003). Recreational leasing disrupts these practices, establishing a pay-to-access regime catered to tourists and middle-class users. Discussing how the forest used to be a commons, an interviewee remarked, ‘I think TWRA has put an end to all that, because you have to have a permit now, you know’ (Fieldnotes. Eagan, TN. January 13th, 2021). Many others expressed similar thoughts.

One ginseng digger in the Clearfork Valley expressed outrage that,

… [P]eople that lived here all their life can't even go over on it [TWRA controlled land]’ (Interview with ginseng digger. Clairfield, TN. January 25th, 2022). Discussing how ginseng digging practices have changed, the interviewee responded, ‘Not as many as there used to [dig it]. Because now there's quite a lot of game wardens. And they've got that land lease, and a lot of people won't pay to travel on it … . (Interview with ginseng digger. Clairfield, TN. January 25th, 2022)

TWRA’s land management has brought very few investments into the valley, and fewer new employment opportunities. Except for a half-dozen campgrounds catering to the all-terrain vehicle (ATV) riders that have flocked to newly established ATV riding trails, the largest of which employees nine year-round employees (Interview with campground manager. Stinking Creek, TN. July 23rd, 2022), there are few indicators of local economic impact from the recreational leasing. Employment figures for the five census tracts in the four counties that comprise the Clearfork Valley have closely tracked job gains and losses in the coal industry over the past decade,Footnote3 indicating little impact from tourism (US Census Bureau Citation2020).

TWRA’s control of this territory has, however, brought a new criminalization of forest access.

… [A] lot of people [are] getting in trouble too for it,’ said one interviewee. ‘If I go 15 feet away from [a permit holder] when I'm on their land, I'll go straight to jail if they pull me over. (Interview with ginseng digger. Clairfield, TN. January 25th, 2022).

The presence of hundreds of ATV riders a weekend is palpable. The hills hum and whine with the echoing sounds of dual-stroke engines as riders enjoy the thrills of off-road trails and rugged abandoned mine features. Of the ATVs, one resident said, ‘I hate them’ (Fieldnotes. March 10, 2022). Others complained about late night and early morning weekend noise as the riders buzzed past resident’s homes.

In 2020, ATV trail riders paid thirty-seven dollars for a permit to ride through the woods, a cost that residents refuse (TN Dept. of Tourism Development Citation2021). Across Appalachia, ATV riders now pay to ride across thousands of miles of private land company lands (Tennessee Wildlife Resource Agency Citation2022; Hatfield and McCoy Trails Redevelopment Authority Citation2011). TWRA and other public agencies collect fees from riders and hunters, sending much of those funds directly to private landowners, such as TNC. Atop the climate rentierism, more traditional forms of rentierism and enclosure, such as recreational leasing, close forests to wider community access.

While enclosure of the forest is felt as a grievance and a wrong, few of my interviewees felt that the closures fundamentally altered their livelihoods or employment. While forest practices are important parts of identity, few people live off of root-digging or hunting in this community, and those that do have found ways to evade TWRA policing. Rather than dispossess people from their livelihoods, these enclosures occur with little economic effect upon local livelihoods.

Nostalgia and grievance in a deindustrialized landscape

Many people in the Clearfork Valley express sentiments of nostalgia for an imagined better past and grievances about economic decline and community dissolution. Despite these grievances, few people talk about leaving the area. The rise of the kind of rentier capitalism that I describe here accompanies processes of uneven deindustrialization. Deindustrialization has left many people across Appalachia without work, in desperate poverty, and with few other places to go. In the Clearfork Valley, many people discuss a sense of being trapped amid attachments to home. Furthermore, rentier capitalism increasingly renders people ‘surplus’ and relegates their communities to disinvestment and abandonment from capital and the state, dynamics which climate investing only deepens. If this is so, why do people in the Clearfork Valley not go somewhere else?

In previous decades, when people across Appalachia were rendered unnecessary to capital they moved to industrial cities of the North (now the ‘Rustbelt’) or South (in a period of rapid ‘Sunbelt’ urban growth) (Obermiller et al. Citation2009). Many in the coalfields no longer see those as options, and indeed many people that lived in cities have come home to retire or find economic refuge in Appalachian communities. Facing the possibility of dire poverty in deindustrialized cities, many people have come back, and many choose to stay in increasingly deindustrialized and disinvested rural communities. These decisions mirror a trend that Tania Li identified across rural communities around the world (Li Citation2010; Citation2014; Citation2017). Many people in the Appalachia region have nowhere to go.

Understanding these decisions is important to conceptualize how climate politics and capitalist dynamics articulate in Appalachia. The hollowing out of rural communities is intimately tied to distrust, disaffection, and resentment among a rural political base in the US (Carr and Kefalas Citation2010; Cramer Citation2016; Ashwood Citation2018; Edelman Citation2018; Berlet and Sunshine Citation2019; Silva Citation2019; Edelman Citation2021). As many people in these rural areas have found political affinity with right-wing anti-establishment conservatives, rural voting blocs now offer significant political opposition to legislation and political momentum to regulate fossil fuels and mitigate the effects of a changing climate.

In this section, I explore the question of why people stay in disinvested places, and I consider how they narrate their situations. People voice sentiments of grief, loss, and abandonment, feelings that are intimately connected to deindustrialization, declining rural qualities of life, and a rentierism that operates with nearly no local workers.

Over the past fifty to seventy years, hundreds of thousands of people have left the Appalachian coalfields in search of better opportunities (Obermiller et al. Citation2009). From 2010 to 2020, most coalfield counties saw more than three percent of their population leave (Pollard and Jacobsen Citation2021, 13). The figure of three-percent population decline during the recent collapse of the coal industry is perhaps less than some might expect. Coal industry employment declined forty percent region-wide, and up to eighty percent in certain sub-regions (e.g. eastern Kentucky) during that same time period (Fritsch Citation2019). As one economic development planner in southern West Virginia explained to me, ‘the coal industry has collapsed … [And] you would expect there to be more of an exodus, considering that there are opportunities other places. But so many people who leave come right back’ (Interview with economic development professional. Zoom. January 26, 2022).

Despite many people expressing a love for the mountains and the country as why they stay or come back to the coalfields, others are more candid about feeling trapped. In the Clearfork Valley, one informant told me repeatedly, ‘If I could leave tomorrow, I would’ (Fieldnotes. September 23rd, 2021), discussing his desire to live in northern Michigan if only he did not have to take care of his ailing mother. ‘I mean, I love it, but I hate it [the valley],’ a young woman in her thirties who had struggled with addiction told me (Fieldnotes. January 7th, 2022).

Many of those that stay in the valley narrate the history of the place through discourses of loss and grief. As one elderly resident told me:

And that was sad. The day that they pulled all the [coal] trucks out. And they all was in a line and they blowed their horns for the last time. You know, it reminded me a lot of when my brother passed away … . (Interview with coalfield resident. Clairfield, TN. September 19, 2021)

Younger residents discussed wanting to stay in the area because they loved the place but also voiced the knowledge that they lived in a place of poverty and want. High school aged people discussed wanting to leave the Clearfork Valley, most of them hoping to move to small towns nearby in East Tennessee or Eastern Kentucky to get jobs there, such as in nursing. During interviews with working age people, however, when I inquired about whether people thought there was more opportunity elsewhere, most of those over the age of twenty-five did not think so. Most did not feel qualified for jobs that they could find elsewhere, and many expressed a fear of being without resources in place without family to fall back on. Like much of the coalfields, people stay because they love the place, but they also stay because there are few other places that they can easily find a job or are easy to live in for poor and working people: as Tania Li argues, conditions of urban deindustrialization make urban places unaffordable and unlivable.

People in the coalfields are increasingly extraneous for landowners. From losses of coal jobs to timber jobs, to the decline of small manufacturing, employment overall has plummeted in the region. Between 1984 and 2022, the Central Appalachian region has witnessed nearly eighty percent decline in coal employment (Open Source Coal Citation2022). Appalachia witnessed a twenty one percent decline in manufacturing jobs from 2002 to 2017 (Appalachian Regional Commission Citation2019, 25), while Central Appalachia lost nearly fifteen percent of its forestry and farming employment in that same fifteen year period (Appalachian Regional Commission Citation2019, 72). People living in the Clearfork Valley have acutely felt these employment trends. As one interviewee put it, ‘it's not a town for a working man. Because if you came in, I don't know where you'd find a job’ (Interview with coalfield resident. Clairfield, TN. September 23rd, 2021).

If under the hegemony of coal companies people faced domination, as John Gaventa documented (Citation1982), today they face irrelevance. New rounds of enclosure and processes of rent seeking join decades-long economic trajectories of deindustrialization that have made life in the coalfields difficult, dispossessing people of land, jobs, housing, public infrastructure, and access to the forest. This is the lived condition of Tania Li’s ‘surplus population;’ people are resentful, distrust the government, and feel irrelevant to local economic activity.

Feelings of grievance and nostalgia in rural communities articulate together in what scholars have documented as ‘rural resentment’ (Cramer Citation2016; Metzl Citation2020). Scholars have tied this resentment to Donald Trump’s election and the rise of a rural right-wing populism in the United States (Edelman Citation2021). Across rural America, feelings of abandonment, dispossession, and decline propel some people to give up on political participation, looking to individualized, personal, and moral solutions (Silva Citation2019). Indeed, Gaventa’s recent assessment of the Clearfork Valley indicated very low levels of political participation (Gaventa Citation2019). Those people that do participate in electoral politics, however, have widely supported far-right anti-establishment candidates (see below), a trend across rural America (Berlet and Sunshine Citation2019). Operating with possessive investments in whiteness and within the crises of masculinity associated with deindustrialization, the feminization of labor (McDowell Citation1991; Citation2014), and downward economic outcomes (Lipsitz Citation2006; Schwartzman Citation2013; Moreton-Robinson Citation2015; Lensmire Citation2017; White Citation2017), uneven deindustrialization creates conditions that fuel authoritarian populism in the countryside (Scoones et al. Citation2018; Gaventa Citation2019; Edelman Citation2021).

A new conjuncture

Far-Right politicians now dominate politics in the Clearfork Valley and much of the coalfields, the results of a thirty-year regional political shift towards the Right (Schwartzman Citation2013; Citation2015; Young Citation2022). Among the valley’s four counties, Republican presidential candidates garnered between 44 and 56 percent of the vote between 1976 and 2000, collectively electing Democrat Bill Clinton twice. Between 2004 and 2020, however, Republican votes steadily increased from 61 to 82 percent of the total votes cast (Leip Citation2022). Local county representatives reflect these presidential percentages. One popular commissioner told me, infamous for his failed attempt in 2022 to establish a publicly funded Confederate monuments museum and for saying that people receiving government assistance should not be allowed to vote, discussing post-coal development, ‘The people [is] what needs to change, not the government’ (Interview with county official. Jacksboro, TN. June 6, 2021). Another county official from the valley opens each commission meeting with a ten-minute invocation to ‘Jesus Christ’ (Fieldnotes. Tazewell, TN. September 25, 2021). Interviews with valley residents show that people’s sentiments of grievance and nostalgia have found a voice in anti-establishment far-Right politics, moralism, and conservatism. Yet, the current politics are not necessarily the politics of the region’s future.

The terrain is rapidly shifting in the coalfields. As Mike Davis argues, the most radically transformative organizing happens conjuncturally, only where and when diverse struggles align, link-up, and collide in new ways (Gramsci Citation2000; Hall Citation1988; Davis Citation2020; Hart Citation2020). Discussing the rise of Margaret Thatcher, Stuart Hall writes, ‘When a conjuncture unrolls, there is no ‘going back.’ History shifts gears. The terrain changes. You are in a new moment’ (Hall Citation1988, 161). The collapse of the coal industry, the crises in neoliberal hegemony (Hall, Massey, and Rustin Citation2015; Fraser Citation2019), substantial attacks on neoliberal rule coming from the Right (Slobodian Citation2021; Cooper Citation2021), and the emergence of popular discourses about the region’s economic transition indicate that the coalfields are in a different conjuncture; a new terrain where struggles emerge.

Perhaps the clearest indication that the coalfields are in this new political and ideological moment is that neoliberal ideology, which has become institutionalized across the coalfields, seems to fail to provide coherent explanation of or substantial answers for the many crises facing people in the coalfields. Across rural America, scholars have noted that neoliberalism faces an ideological crisis (Brown Citation2019; Fraser Citation2019; Peck and Theodore Citation2019; Davies and Gane Citation2021). Traditional divides between the Left and the Right are eroding in rural places where everyone can agree about their distrust of a state that works for corporate interests (Ashwood Citation2018). In Appalachia, there is widespread animosity towards mainstream political life that has failed to improve social conditions in the region for fifty years (Martin Citation2019), neither saving the coal industry nor planning for an economic transition (M. Gunnoe Citation2019). Political figures that buck a political elite in a Trumpian style are widely popular, such as West Virginia’s Democrat-turned-Republican governor, Jim Justice (Young Citation2022).

Political alliances are reorienting in this moment. For instance, in the Clearfork Valley, a coalition for community-led economic development, the Tennessee Appalachian Community Economies coalition, has garnered sustained community engagement from conservative pastors to anarchist community organizers. There is a growing consensus in the valley and across the region that the current economic development regime will not contend with the crises of disinvestment and deindustrialization. As one non-profit leader assuredly said of the recent wave of federal investments, ‘Oh, it’ll never make it down to the little guys like us’ (Fieldnotes. March 23, 2021), an assessment that has, sadly, so far born true.

No clear ideology or political alliance, however, has usurped neoliberal rule. Instead, reactionary, nostalgic, grievance laden politics that struggle to articulate strong visions of the future (such as those of the county commissioners or of West Virginia’s governor) dominate the landscape, indicating that, ‘the old is dying and the new cannot be born’ (Gramsci Citation1971, 276). While right-wing anti-elitism animates local politics, such politics fail to offer an imaginable future for the region.

Conclusion: towards a Left rural populism

In this moment, Leftist politics have the potential to galvanize support around brighter imaginable futures for the region. Many organizations and activists in Appalachia are already contesting and, perhaps, ‘eroding’ (Wright Citation2017) capitalist rentier relations through efforts to create more livable and democratic communities. These efforts build towards a strategy for rural Left populism.

On a regional scale, several institutions and organizations are working to mobilize grassroots support around economic agendas in Appalachia. These efforts include the Alliance for Appalachia, a coalition of grassroots progressive and environmental justice organizations in the region, advocating, among other things, for federal funding to create jobs remediating mined lands; Appalachian Voices, a regional non-profit advancing various campaigns for economic revitalization and environmental justice; and the ReImagine Appalachia coalition, advocating for a new New Deal and a federal jobs program.

A Left populist strategy, as Chantal Mouffe describes, must aim ‘at federating the democratic demands into a collective will to construct a ‘we,’ a ‘people’ confronting a common adversary: the oligarchy’ (Mouffe Citation2018, 24). Widespread disaffection with contemporary economic conditions provides an opening for Left populism to craft a new common will, one posed against the political entities of the region’s economic status quo.

This article highlights the centrality of land and land ownership in the post-coal political economic trajectory in Appalachia. More research is needed about the potential for struggles over land and land access to become issues that might galvanize new alliances in Appalachia, and to examine what agrarian populism (Borras Citation2020), however fraught that concept may be (Bernstein Citation2020), might mean in this context. Further research should consider what a ‘make live’ (Li Citation2010) biopolitics would be in Appalachia, and how the post-work politics of welfare, disability, and forest access articulate in emergent political alliances.

In the current moment, many Leftist political programs, such as social democracy, run counter to Right-wing populist rhetoric around individual responsibility and white Christian moralism, the imaginaries articulated to the current hegemonic alliance. Yet, as discussed, there is a palpable crisis of ideology in the region. Political factions that offer renewed political imagination may stand a chance of forging new hegemonic alliances with rural working and non-working people in coalfield Appalachia, alliances that could shift balances of power across the United States.

Political action on climate change requires this type of shift in rural politics in the United States. Rural voters, constituencies, and political representatives currently obstruct any political agendas that might stem fossil fuel use or constitute significant emissions reductions. Reversing this obstruction will require a national political alliance that convincingly promises to improve the quality of life for rural people.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, whose generous and constructive comments have been invaluable in this paper, and to thank the members of the TNACE coalition in the Clearfork Valley, whose work greatly informs this analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gabe Schwartzman

Gabe Schwartzman is in the Department of Geography, Environment, and Society at the University of Minnesota.

Notes

1 Many landowners sell carbon offsets to voluntary carbon offset markets, e.g., for air travel.

2 Based on the average price of carbon and number of offsets sold on the California market.

3 The valley lost 1,328 coal jobs from 2010–2020 in a total population of 15,000 in 2020. Numbers of employed persons track this figure.

References

- Appalachian Land Ownership Task Force. 1979. Who Owns Appalachia? Landownership and Its Impact. Lexington: Univ Pr of Kentucky.

- Appalachian Land Study. 2022. “Land Study Mission, Objectives, and Methods.” Appalachian Land Study. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://www.appalachianlandstudy.org/abou.

- Appalachian Regional Commission. 2019. “Industrial Make-Up of the Appalachian Region: Employment and Earnings 2002–2017.” Division of Research and Evaluation. Washington, DC: Appalachian Regional Commission. https://www.arc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IndustrialMakeUpoftheAppalachianRegion2002-2017.pdf.

- Ashwood, Loka. 2018. For-Profit Democracy: Why the Government Is Losing the Trust of Rural America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Badgley, Grayson, Jeremy Freeman, Joseph J. Hamman, Barbara Haya, Anna T. Trugman, William R. L. Anderegg, and Danny Cullenward. 2022. “Systematic Over-Crediting in California’s Forest Carbon Offsets Program.” Global Change Biology 28 (4): 1433–1445. doi:10.1111/gcb.15943.

- Berlet, Chip, and Spencer Sunshine. 2019. “Rural Rage: The Roots of Right-Wing Populism in the United States.” Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (3): 480–513. doi:10.1080/03066150.2019.1572603.

- Bernstein, Henry. 2020. “Unpacking ‘Authoritarian Populism’ and Rural Politics: Some Comments on ERPI.” Journal of Peasant Studies 47 (7): 1526–1542. doi:10.1080/03066150.2020.1786063.

- Bigger, Patrick, and Wim Carton. 2020. “Finance and Climate Change.” In The Routledge Handbook of Financial Geography. New York: Routledge.

- Bigger, Patrick, and Nate Millington. 2020. “Getting Soaked? Climate Crisis, Adaptation Finance, and Racialized Austerity.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 3 (3): 601–623. doi:10.1177/2514848619876539.

- Boling, Zhang. 2012. “China Digs into American Coal Mines.” MarketWatch, May 29, 2012, sec. Industries. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/china-digs-into-american-coal-mines-2012-05-29.

- Borras, Saturnino M. 2020. “Agrarian Social Movements: The Absurdly Difficult but Not Impossible Agenda of Defeating Right-Wing Populism and Exploring a Socialist Future.” Journal of Agrarian Change 20 (1): 3–36. doi:10.1111/joac.12311.

- Borras, Saturnino M., Ian Scoones, Amita Baviskar, Marc Edelman, Nancy Lee Peluso, and Wendy Wolford. 2022. “Climate Change and Agrarian Struggles: An Invitation to Contribute to a JPS Forum.” Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1080/03066150.2021.1956473.

- Brown, Wendy. 2019. In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. New York: Columbia University Press.

- California Air Resources Board. 2019. “U.S. Forest Offset Projects: Overview.” Sacramento: California Air Resources Board.

- Carr, Patrick J., and Maria J. Kefalas. 2010. Hollowing Out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What It Means for America. Illustrated Edition. Boston: Mass: Beacon Press.

- Christophers, Brett. 2019. “The Rentierization of the United Kingdom Economy.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, September, 0308518X19873007. doi:10.1177/0308518X19873007.

- Christophers, Brett. 2020. Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It? London: Verso Books.

- Cooper, Melinda. 2021. “The Alt-Right: Neoliberalism, Libertarianism and the Fascist Temptation.” Theory, Culture & Society 38 (6): 29–50. doi:10.1177/0263276421999446.

- Cooper, Hannah LF, David H. Cloud, Patricia R. Freeman, Monica Fadanelli, Travis Green, Connor Van Meter, Stephanie Beane, Umedjon Ibragimov, and April M. Young. 2020. “Buprenorphine Dispensing in an Epicenter of the U.S. Opioid Epidemic: A Case Study of the Rural Risk Environment in Appalachian Kentucky.” International Journal of Drug Policy 85 (November): 102701. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102701.

- Cramer, Katherine J. 2016. The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Illustrated Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Darling, Eliza. 2005. “The City in the Country: Wilderness Gentrification and the Rent Gap.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 37 (6): 1015–1032. doi:10.1068/a37158.

- Davies, William, and Nicholas Gane. 2021. “Post-Neoliberalism? An Introduction.” Theory, Culture & Society 38 (6): 3–28. doi:10.1177/02632764211036722.

- Davis, Mike. 2020. Old Gods, New Enigmas: Marx’s Lost Theory. London: Verso.

- Dezember, Ryan. 2020. “Preserving Trees Becomes Big Business, Driven by Emissions Rules.” Wall Street Journal, Accessed August 24, 2020, sec. Markets. https://www.wsj.com/articles/preserving-trees-becomes-big-business-driven-by-emissions-rules-11598202541.

- Edelman, Marc. 2018. “Sacrifice zones in rural and non-metro USA: fertile soil for authoritarian populism.” Transnational Institute. Accessed February 21, 2018. https://www.tni.org/my/node/23914.

- Edelman, Marc. 2021. “Hollowed out Heartland, USA: How Capital Sacrificed Communities and Paved the Way for Authoritarian Populism.” Journal of Rural Studies 82 (February): 505–517. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.045.

- Edelman, Marc, and Wendy Wolford. 2017. “Introduction: Critical Agrarian Studies in Theory and Practice.” Antipode 49 (4): 959–976. doi:10.1111/anti.12326.

- Energy Information Agency. 2019. Annual Energy Outlook 2019 with Projections to 2050. Washington, DC: Office of Energy Analysis, US Dept. of Energy.

- Eller, Ronald D. 2008. Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945. 1st ed. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

- Elliston, Jon. 2019. “Heart of Appalachia.” The Nature Conservancy Magazine. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.nature.org/en-us/magazine/magazine-articles/cumberland-forest-project/.

- Fairbairn, Madeleine. 2020. Fields of Gold: Financing the Global Land Rush. Cornell Series on Land : Perspectives in Territory, Development, and Environment. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Felli, Romain. 2014. “On Climate Rent.” Historical Materialism 22 (3–4): 251–280. doi:10.1163/1569206X-12341368.

- Fraser, Nancy. 2019. The Old Is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born: From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump and Beyond. London . New York: Verso.

- Fritsch, David. 2019. “U.S. Coal Production Employment Has Fallen 42% since 2011.” Today in Energy. Washington, DC: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id = 42275.

- Gaventa, John. 1982. Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence & Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Gaventa, John. 2019. “Power and Powerlessness in an Appalachian Valley – Revisited.” Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (3): 440–456. doi:10.1080/03066150.2019.1584192.

- Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. “Selections from the Prison Notebooks.” Edited by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. Reprint, 1989 Edition. New York: International Publishers Co.

- Gramsci, Antonio. 2000. The Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings 1916–1935, edited by David Forgacs. New York: New York University Press.

- Gunnoe, Andrew. 2014. “The Political Economy of Institutional Landownership: Neorentier Society and the Financialization of Land.” Rural Sociology 79 (4): 478–504. doi:10.1111/ruso.12045.

- Gunnoe, Maria. 2019. “An Open Letter from Fighter against Mountain Top Removal Coal Mining.” People’s Tribune (blog). Accessed October 11, 2019. http://peoplestribune.org/pt-news/2019/10/letter-from-fighter-against-mountain-top-removal-mining/.

- Gunnoe, Andrew, Conner Bailey, and Lord Ameyaw. 2018. “Millions of Acres, Billions of Trees: Socioecological Impacts of Shifting Timberland Ownership.” Rural Sociology 83 (4): 799–822. doi:10.1111/ruso.12210.

- Gunnoe, Andrew, and Paul K. Gellert. 2011. “Financialization, Shareholder Value, and the Transformation of Timberland Ownership in the US.” Critical Sociology 37 (3): 265–284. doi:10.1177/0896920510378764.

- Hall, Stuart. 1988. The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism And The Crisis Of The Left. London . New York: Verso Books.

- Hall, Stuart, Doreen Massey, and Michael Rustin. 2015. After Neoliberalism?: The Kilburn Manifesto. London: Lawrence & Wishart Ltd.

- Hart, Gillian. 2020. “Why Did It Take so Long? Trump-Bannonism in a Global Conjunctural Frame.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 102 (3): 239–266. doi:10.1080/04353684.2020.1780791.

- Hatfield and McCoy Trails Redevelopment Authority. 2011. “Hatfield and McCoys Trails.” Charleston, WV: WV Department of Transportation. https://transportation.wv.gov/highways/programplanning/plan_conf/Documents/2011PC/Hatfield_McCoy_Trails.pdf.

- Hsia-Kiung, Katherine, and Erica Morehouse. 2015. Carbon Market California: A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOLDEN STATE’S CAP-AND-TRADE PROGRAM. Washington, DC: Environmental Defense Fund. https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/content/carbon-market-california-year_two.pdf.

- Hufford, Mary. 1993. “Tending Commons: Ramp Suppers, Biodiversity and the Integrity of 'The Mountains'.” Folklife Center News. Washington, DC: American Folklife Center, the Libary of Congress.

- Hufford, Mary. 2003. “Knowing Ginseng: The Social Life of an Appalachian Root.” Cahiers de littérature orale 53 (1): 265–291.

- Karakilic, Emrah. 2022. “Rentierism and the Commons: A Critical Contribution to Brett Christophers’ Rentier Capitalism.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 54 (2): 422–429. doi:10.1177/0308518X211062233.

- Kay, Kelly. 2017. “Rural Rentierism and the Financial Enclosure of Maine’s Open Lands Tradition.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 107 (6): 1407–1423. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1328305.

- Kay, Kelly. 2018. “A Hostile Takeover of Nature? Placing Value in Conservation Finance.” Antipode 50 (1): 164–183. doi:10.1111/anti.12335.

- Kratzer, Nate W. 2015. “Coal Mining and Population Loss in Appalachia.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 21 (2): 173–188. doi:10.5406/jappastud.21.2.0173.

- Leip, David. 2022. “Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections.” 2022. http://uselectionatlas.org/.

- Lensmire, Timothy J. 2017. White Folks: Race and Identity in Rural America. Writing Lives : Ethnographic Narratives. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2010. “To Make Live or Let Die? Rural Dispossession and the Protection of Surplus Populations.” Antipode 41 (s1): 66–93. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00717.x.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2014. Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2017. “After Development: Surplus Population and the Politics of Entitlement.” Development and Change 48 (6): 1247–1261. doi:10.1111/dech.12344.

- Lipsitz, George. 2006. The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics, Revised and Expanded Edition. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Maggard, Sally Ward. 1994. “From Farm to Coal Camp to Back Office and McDonald’s: Living in the Midst of Appalachia’s Latest Transformation.” Journal of the Appalachian Studies Association 6: 14–38.

- Maimon, Alan. 2021. Twilight in Hazard: An Appalachian Reckoning. New York: Melville House.

- Martin, Lou. 2019. Appalachia in the Age of Neoliberalism. Asheville, NC: Marshall University. https://mds.marshall.edu/asa_conference/2019/session6/26.

- McDowell, Linda. 1991. “Life Without Father and Ford: The New Gender Order of Post-Fordism.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 16 (4): 400. doi:10.2307/623027.

- McDowell, Linda. 2014. “Gender, Work, Employment and Society: Feminist Reflections on Continuity and Change.” Work, Employment and Society 28 (5): 825–837. doi:10.1177/0950017014543301.

- Meit, Michael, M. P. H. Heffernan, Erin Tanenbaum, Maggie Cherney, and Victoria Hallman. 2020. “Appalachian Diseases of Despair.” Final Report. Appalachian Diseases of Despair. Chicago: University of Chicago NORC. https://www.arc.gov/report/appalachian-diseases-of-despair/.

- Metzl, Jonathan M. 2020. Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment Is Killing America’s Heartland. Illustrated Edition. New York: Basic Books.

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. 2015. The White Possessive. 1 ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mouffe, Chantal. 2018. For a Left Populism. London . New York: Verso.

- The Nature Conservancy. 2019. “Cumberland Forest Project.” The Nature Conservancy. 2019. https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/kentucky/stories-in-kentucky/cumberland-forest/.

- The Nature Conservancy. 2021. “The Nature Conservancy, Director Cumberland Forest Project.” Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.impactfinancepro.com/cumberland-forest-the-nature-conservancy/.

- Oberhauser, Ann M. 1993. “Industrial Restructuring and Women’s Homework in Appalachia: Lessons from West Virginia.” Southeastern Geographer 33 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1353/sgo.1993.0011.

- Obermiller, Phillip, Chad Berry, Roger Guy, J. Trent Alexander, William Philliber, Michael Maloney, and Bruce Tucker. 2009. “Major Turning Points: Rethinking Appalachian Migration.” Appalachian Journal 36 (3/4): 164–187.

- Open Source Coal. 2022. “Coal Production by Mine Type and Employment 1983-2022 in the 'Central Appalachian' Region.” Appalachian Voices. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.opensourcecoal.org.

- Peck, Jamie, and Nick Theodore. 2019. “Still Neoliberalism?” South Atlantic Quarterly 18 (2): 245–265. doi:10.1215/00382876-7381122.

- Pollard, Kevin, and Linda A. Jacobsen. 2021. “The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview from the 2015-2019 American Community Survey. Chartbook.” Appalachian Regional Commission. https://eric.ed.gov/?id = ED613609.

- Ray, Tarence. 2021. “United in Rage.” The Baffler, July 6, 2021. https://thebaffler.com/salvos/united-in-rage-ray.

- Rigg, Khary, Shannon Monnat, and Melody Chavez. 2018. “Opioid-Related Mortality in Rural America: Geographic Heterogeneity and Intervention Strategies.” International Journal of Drug Policy 57 (July): 119–129. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.011.

- Schwartzman, Gabe. 2013. Where Appalachia Went Right: White Masculinities, Nature, and Pro-Coal Politics in an Era of Climate Change. Berkeley, CA: Center for Right Wing Studies, University of California. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/4wm02403.

- Schwartzman, Gabe. 2015. “How Central Appalachia Went Right.” The Daily Yonder, Accessed January 13, 2015. http://dailyyonder.com/how-coalfields-went-gop/2015/01/13/.

- Scoones, Ian, Marc Edelman, Saturnino M. Borras Jr, Ruth Hall, Wendy Wolford, and Ben White. 2018. “Emancipatory Rural Politics: Confronting Authoritarian Populism.” Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1339693.

- Silva, Jennifer M. 2019. We’re Still Here: Pain and Politics in the Heart of America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Singh, Gopal K., Michael D. Kogan, and Rebecca T. Slifkin. 2017. “Widening Disparities In Infant Mortality And Life Expectancy Between Appalachia And The Rest Of The United States, 1990–2013.” Health Affairs 36 (8): 1423–1432. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1571.

- Slobodian, Quinn. 2021. “The Backlash Against Neoliberal Globalization from Above: Elite Origins of the Crisis of the New Constitutionalism.” Theory, Culture & Society 38 (6): 51–69. doi:10.1177/0263276421999440.

- Smith, Neil. 1979. “Toward a Theory of Gentrification A Back to the City Movement by Capital, Not People.” Journal of the American Planning Association 45 (4): 538–548. doi:10.1080/01944367908977002.

- Smith, Neil. 1996. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. 1st Edition. London . New York: Routledge.

- Spence, Beth, Cathy Kunkel, Elias Schewel, Ted Boettner, and Lou Martin. 2013. Who Owns West Virginia in the 21st Century. Charleston, WV: West Virginia Center for Budget and Policy.

- Tennessee Wildlife Resource Agency. 2022. “The Nature Conservancy, TWRA Announce Conservation Easement to Benefit North Cumberland WMA’s Ed Carter Unit.” Government. Tennesse State Government. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://www.tn.gov/twra/news/2022/1/10/the-nature-conservancy–twra-announce-conservation-easement-to-benefit-north-cumberland-wma-s-ed-carter-unit.html.

- Tingley, Andrew. 2021. “How The Nature Conservancy’s Work in the Cumberland Forest Supports Jobs & Climate Mitigation.” Salesforce.Org. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.salesforce.org/blog/the-nature-conservancy-cumberland-forest-project/.

- TN Dept. of Tourism Development. 2021. “Tennessee Tourism Outperformed the Nation in 2020 with $16.8 Billion in Visitor Spending Despite COVID-19.” TN Department of Tourism Development. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/tourism/news/2021/8/6/tennessee-tourism-outperformed-the-nation-in-2020-with–16-8-billion-in-visitor-spending-despite-covid-19.html.

- US Census Bureau, American Community Survey. 2020. “American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table S1071.” Generated by Gabe Schwartzman. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/.

- White, Dustin. 2017. “The Toxic Masculinity of Fossil Fuels.” Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition (blog). Accessed November 11, 2017. https://ohvec.org/toxic-masculinity-fossil-fuels/.

- Winant, Gabriel. 2021. The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America. Caimbridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wright, Erik Olin. 2017. “How to Be an Anti-Capitalist for the 21 St Century.” Theomai 35: 8–21.

- Young, Charles. 2022. “Gov. Jim Justice: ‘West Virginia Is in Demand.’” WV News. 2022. https://www.wvnews.com/statejournal/news/gov-jim-justice-west-virginia-is-in-demand/article_d4a2c50c-9bd7-11ec-b177-73e9990e2095.html.

- Zhang, Xufang, and Anne Stottlemyer. 2021. Lumber and Timber Price Trends Analysis During the COVID-19 Pandemic. College Station, TX: Forest Analytics Department.