ABSTRACT

Agroecological transitions in the Global North are inhibited by the cultural and legal norms of a ‘ownership model’ of property that underpins agrarian capitalism. The resulting property system limits asset transfers to agroecological regimes and co-produces technologically oriented reforms. Scotland’s land reforms are emergent legal interventions to reshape land ownership within a Western legal context. By examining legal manoeuvres, mobilizing discourses, and governance considerations in Scotland, we sketch a roadmap for rethinking property in regions where the ownership model is entrenched. This case suggests that existing property law can be leveraged to achieve shifts in property norms towards promoting agroecology.

Introduction

Globally, modernized agricultural systems – characterized by input-intensive crop monocultures and large-scale feedlot operations – produce economic and labour injustices (Rosset and Altieri Citation1997), degrade ecosystem services (Kremen and Miles Citation2012; IPES-Food Citation2016), exacerbate climate change (IPCC Citation2019), and simultaneously drive global obesity and malnourishment (Patel Citation2012; Schutter Citation2011). Agroecology, a combination of ecological farming practices and the knowledge and social movements to support these practices, offers a compelling model for creating a more just and resilient food system (Gliessman Citation2018; Altieri and Toledo Citation2011; Wittman Citation2009). Agroecology meets food production needs through nurturing complex, ecologically rich working lands that enhance biodiversity and provide numerous ecosystem services. These territories reduce use of off-farm inputs like agrochemicals, sustain farmer and worker livelihoods, and contribute to nutrition and food security at local and regional scales (Bezner Kerr et al. Citation2021; Perfecto and Vandermeer Citation2010). Agroecology provides principles and practices that can be locally adapted in places worldwide, reflecting their specific social, ecological, and environmental conditions (Wezel et al. Citation2020). While agroecology began as a study of the agronomic methods of farming ecologically, it has come to include the social relations and governance regimes that support and expand these forms of food production, such as new emancipatory labour and market relations (Francis et al. Citation2003). In many places, agroecology has become associated with rebuilding local food economies based on solidarity, asserting farmer independence from the dominant industrial agricultural system, and maintaining or reviving diverse crops and livestock that reflect the region’s culture and history. For these reasons, La Via Campesina, the international peasant and smallholder farmer movement, puts forth agroecology as the desired agricultural paradigm in order to achieve its broader objective of ‘food sovereignty’ (Nyéléni Citation2015). Agroecological movements and farmers are thriving or emerging in many places around the planet, from India to Mexico and from the US to Australia (Iles Citation2021; Tittonell et al. Citation2020; Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho et al. Citation2018; Brescia Citation2017).

Despite the demonstrated potential of agroecology, the approach has not gained much traction in the national policies, land use planning or cultural norms of countries in the Global NorthFootnote1 (Lang Citation2020; Ploeg et al. Citation2019). Agroecological transitions seem to be sluggish and still highly localized in the form of farm experiments and ad hoc institutional supports (e.g. Iles Citation2021). In the United Kingdom, for example, efforts to include recognition and support for agroecology within the Agriculture Bill (prompted by the UK’s departure from the European Union) were rejected in the national Parliament, instead opting for milquetoast agri-environmental schemes as the preferred reform strategy in the Agricultural Act 2020 (Soil Association Citation2020). In other European countries, proponents of alternative food systems have put pressure on the reform process of the Common Agricultural Policy (Pe’er et al. Citation2019), but the consensus policy options that are emerging emphasize market-based mechanisms like climate smart agriculture, sustainable intensification and increased funding for agri-environmental payment schemes (Moschitz et al. Citation2021).

What might help agroecological transitions break through these apparent logjams in the Global North and expand beyond their current niche innovation status? Wezel et al. (Citation2020, 8) note: ‘[T]o effectively address food security and nutrition, discrete techniques or innovations and incremental interventions are not sufficient to bring about the food system transformations that are needed’. Rather, foundational, systemic changes need to occur to enable agroecology to expand across a country and become a core feature of its food system. Recent scholarship on agroecological transitions have pointed to several systemic leverage points in industrial countries, such as rectifying the imbalance in government research funding for agroecology (DeLonge, Miles, and Carlisle Citation2016), restructuring agricultural extension services to embrace agroecology (Miles, DeLonge, and Carlisle Citation2017), integrating human health analyses of agroecology to build new constituencies (O’Rourke, DeLonge, and Salvador Citation2017), and developing ‘agricultural lighthouses’ that demonstrate the benefits of adoption to producers (Nicholls and Altieri Citation2018).

Here, we argue that efforts to advance agroecology in Global North locales are muted because they ultimately tiptoe around the foundational role that property regimes – especially the form known as the ‘ownership model’ – play in shaping agricultural land use and the associated political power of agricultural landowners. Existing proposals to amplify agroecology often overlook how land relations act as a critical enabling factor for the agronomic, social, and political interdependencies endemic to agroecological production (Calo Citation2020a). Researchers, NGOs, and movements in the Global North may view the notion of land reform as politically unpalatable and thus avoid demanding change in property regimes (Roman-Alcala Citation2015). Moreover, the smallholder model that predominates in much of the Global South food sovereignty activism, tends to be inverted by the socio-legal commitments of strong property regimes in the Global North. The result is a powerful ‘yeoman farmer’ mythology that drives agroecological farmers to operate as atomized entrepreneurial units, rather than as a social force concerned with land justice (Calo Citation2020b).

While critical agrarian scholars and proponents of agroecology have long identified the urgent need for new land access and redistribution (Calo Citation2020b; Shoemaker Citation2020; Williams and Holt-Giménez Citation2017), their attention has less often focused on the potential pathways to provide access in a context where the private property model is enshrined in culture and in the law. There have been fits in starts, of late, invoking Indigenous claims to land (Ramírez Citation2020), reparations for dispossession of minoritized farmers (Penniman Citation2018), and new legal land trust models that aim to de-commodify agricultural land piece by piece (Anderson Citation2021). These calls for land justice or piecemeal efforts at land decommodification are important and welcome. However, we argue they lack a coherent asset acquisition and transfer strategy that can be applied to diverse socio-cultural and geographical contexts and is accessible to all agroecological farmers. Such a strategy for legitimizing and legalizing new land tenure relations to foster agroecology amidst a seemingly ‘settled’ system of property rights (Bromley and Hodge Citation1990) in the Global North is the focus of this article.

The community land agenda emerging in Scotland offers an instructive case for the politics and processes of reforming property relations amidst a strong socio-legal commitment to the ownership model of property. Scotland has long been characterized by one of the world’s most concentrated land ownership structures. The Scottish land reform agenda suggests how land might be unlocked from entrenched ownership patterns, challenge power relations embedded with land ownership, and transfer significant acreage of productive land from one form of tenure to another. Via a series of Land Reform Acts between 2003 and 2016, Scotland has given community entities the right to buy land ahead of other purchasers, which has recently been strengthened to allow communities to buy vacant and unused land without landowner agreement, or land that they wish to develop sustainably. As a result, we suggest a new opening for agricultural transformation and agroecological transitions in Scotland has materialized, because of how legal manoeuvres, mobilizing discourses, and governance structures have combined to legitimize and legalize land reforms that reflect Scotland’s particular history and evolving political identity. Farmers interested in agroecology could potentially use the new land reforms to secure access to the land they need. We point to emerging evidence of a revitalized food movement in Scotland which shows the interplay between new legal opportunity and visions of alternative land use. However, at present an agroecological vision for Scotland’s agrarian system is lacking, and as a result land reforms have unharnessed potential to reshape Scottish agriculture. Less than 0.5% of agricultural land in Scotland is used for fruit and vegetables for human consumption and across the UK, the ‘fruits and vegetables’ category has the largest trade deficit at £10.2bn in 2020 (DEFRA Citation2022). For Scotland to transform its food system, it must match its willingness to reshape land governance with a bottom-up movement of agroecological farmers committed to farm beyond the standard smallholder model.

We first review the literature on the relationship between socio-legal norms of property and agrarian land use. Our review shows how property relations shape and facilitate agrarian capitalism as well as muting attempted food system reforms. We then turn to the Scottish land reform agenda, laying out its fundamental architecture, progress to date, and early lessons for agricultural transformation. We frame these interventions in terms of contributions from access and agrarian change scholars who situate claims to natural resources as an interplay between legitimizing and legalization practices and the authorities that validate these claims. Finally, we discuss the extent to which the land reforms succeed in challenging property norms and how Scotland’s experience may be instructive for other Global North constituencies seeking to promote deep agroecological transformation amidst strong private property contexts.

The ownership model of property and its contradictions with agroecological transformation

In the Global North, a particular construction of property has risen to dominance since the eighteenth century, enshrined in culture and in law as something akin to a natural right (Christophers Citation2020; Christman Citation1994). In liberal democratic societies, property broadly takes the limited form of the ‘ownership’ or ‘Blackstonian’ model of property, washing away the complexity of land and resource access relations in becoming understood as the individual, exclusive possession of identifiable things (Blomley Citation2005). The restricted ‘castle-and-moat’ view of what property is – and what it should be – has lasting implications for how humans relate to the land and thus how agroecological production may expand in regions where the ownership model prevails.

The ownership model stipulates a set of accepted norms and proscriptions for human relationships with land. The model makes a paramount commitment to the ‘protection of individual control over valued resources’ (Alexander et al. Citation2009). In this construction, an individual owner of property possesses the strong negative right to exclude others from access to the property and complete autonomy to use the property as they desire. This right to exclude extends to a state guarantee against expropriation or ‘takings’ by the state through bedrock legal constructions like the final clause of the Fifth Amendment in the US Constitution and Article 1 of the first Protocol of the European Convention on Human Rights.Footnote2 Farm owners, then, have the right to turn their land into monoculture fields, use toxic chemicals to attack pests and weeds, and over-use soils even if these harm the environment and weaken food system resilience. They can also leave their land unused and unproductive if they wish to, even if local communities want to experiment with agroecological production.

The enduring propensity to champion the ownership model can be attributed to its foundational role in liberal ideology, where property is the progenitor of freedom and the engine of economic prosperity. For example, Hayek (Citation1944) situates property as core to the pursuit of a liberal utopia, protecting democracy against the tyranny of governments. The ownership model is also driven by a persuading narrative about wealth creation. If humans are innately rational utility maximizers, then the best way to facilitate trade and reduce wasteful conflict is to clearly define who owns what (Rose Citation2019).

Blomley (Citation2005) warns that the entrenchment of the ownership model prefigures a set of problematic property relations where the primacy of a legally identified owner is assumed over informal communal claims, the commonsense notion of property becomes ‘private property’, owners are motivated by self-interest, and owners intrinsically are engaged in competitive dynamics, for example owners against neighbours and owners against state intervention (126). These property relations, deeply rooted in social and legal discourses of the Global North, pose deep challenges to the expansion of agroecology. And while some property scholars applaud the call for new models to uphold relegated ethical commitments, an active legal tradition based in libertarian values and ‘constitutional originalism’ argues that the state’s effort to regulate private landowners in the name of environmental benefits for the public good is the ‘civil rights issue of our time’, aiming to affirm the ownership model at all costs (Marzulla Citation2001, 241).

Where the ownership model of property dominates, the flourishing of agroecology is constrained in multiple ways. Proponents of agroecological transformation recognize the importance of supportive land relations as the basis for agroecological expansion. Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho et al. (Citation2018), in their exploration of cases of agroecological transitions, note that ‘access to land for farmer families is a necessary precondition for agroecology and its growth’ (Citation2018, 8). Yet this access is often precarious and mediated by structural racism and economic inequality.

Substantial contemporary agroecological efforts are involved in restoring the complex traditional ecological knowledge systems that were displaced through the atomizing force of the ownership model (Saylor, Alsharif, and Torres Citation2017). Over the past few centuries, the discovery doctrine, where settler colonial states define already inhabited land as ‘empty’ and then grants it as property, has repeatedly erased the landscape level management regimes of Indigenous peoples (Miller Citation2019; Pascoe Citation2018). As a result, Indigenous peoples are less able to maintain access to land in which to practice their traditional agroecological knowledge.

In addition, the colonial need to rationalize landscapes through property boundaries created artificial borders that split the ecological interconnections underlying landscape socio-ecological systems. This approach contrasts with the contemporary understanding of how landscape level interactions shape agroecological outcomes, as is the case for landscape habitat and pollinator efficiency (Kremen, Iles, and Bacon Citation2012), and with how actions taken at the farm level can create environmental benefits and dis-services to the broader public (Ribaudo et al. Citation2012). Agroecological food webs often operate across large watersheds, as in the case of upland taro growers and lowland fisher people in pre-colonial Hawaii (Lincoln Citation2013), but new Westernized property regimes render the upstream and downstream users of water as self-contained, independent entities rather than connected by the social and cultural processes that support large scale collaborative land management.

The ownership model thus has an imposing role in cleaving natural systems from human activity, constraining a diversity of potential landscape relationships into one that is decidedly concerned with production and trade. Rose (Citation2019) shows how the early application of the doctrine of first possession fundamentally remakes the human-nature relationship. Grounded in a Lockean philosophy of mixing one’s labour with land as the progenitor of ownership entitlements, Rose (Citation2019) argues that the doctrine of first possession can only succeed by validating certain forms of labour that are distinct from the land management regimes of non-settlers:

The doctrine of first possession, […] reflects the attitude that humans are outsiders to nature. It gives the earth and its creatures over to those who mark them so clearly as to transform them, so that no one will mistake them for unsubdued nature. The metaphor of the law of first possession is, after all, death and transfiguration; to own a fox the hunter must slay it, so that he or someone else can turn it into a coat. (18)

Another key problem dominant property regimes pose for agroecological expansion is their role in maintaining the control of access to quality farmland for powerful actors. Scholars recognize, for example, how historical property regimes in the United States have shaped racialized agricultural land ownership and control patterns that make entry to the agricultural sector profoundly difficult (Calo Citation2020b; Shoemaker Citation2020; Carlisle et al. Citation2019b). An emerging class of farmers who have the skills and the aspiration to farm agroecologically cannot gain access to quality land at meaningful scales because of restrictive land markets (Minkoff-Zern Citation2019; Carlisle et al. Citation2019a; Calo Citation2018). This problem is compounded by the way private property rights now articulate with farmland financialization. Atop existing trends of farmland conversion for development, land prices become further inflated by turning land into financial commodities for investors, further locking out farmers who want the land to farm instead of speculating on investment value (Fairbairn Citation2020).

Even if agroecological farmers do gain access to land, this land is often marginal because it is cheaper or carries such financial burden that they are less able to farm with the techniques or the time-horizon needed to generate adaptive capacity and biological diversification (Petersen-Rockney et al. Citation2021). Otherwise, aspiring agroecologists may only gain access if they possess significant capital, social connections, and experience, leading to an agroecological gentrification where only the well-off can afford to enter (Pilgeram Citation2019; Sutherland Citation2012). For many farmers who have insecure rental agreements or debt-leveraged loans, their ability to benefit from the improvements they make to the land is prohibited as the power to decide how to manage the land is frequently in the owners’ or debtors’ hands (Calo and De Master Citation2016).

Finally, a key aspect of agroecology is the promotion of solidarity markets, where market relations are shaped to support the transition to agroecology through shared labour and price thresholds that produce dignified agricultural livelihoods (Nicholls and Altieri Citation2018). A solidarity market may include a policy change to create price floors and other contract guarantees like public procurement programs (Graddy-Lovelace and Diamond Citation2017). To implement solidarity markets for agroecological production, agroecologists need social and political power to intervene in established corporate food market relations (Anderson et al. Citation2019) yet large landowning agricultural operations that represent the largest commodity producers enjoy political representation to uphold a farm and trade policy that rewards the industrial model of production (Kovacs Citation2021). As long as the majority of farmland assets are controlled and consolidated by industrial agriculture interests, the power of agroecologists to shape food regimes will always be marginalized (Howard Citation2016).

Challenges to the ownership model in property studies

Although the dominant ownership model is entrenched in the socio-legal configurations of most Global North contexts, it is contested in much property scholarship that seeks to establish how property is socially constructed according to particular cultures and legal traditions (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003) rather than being an ahistorical, universal concept (Rose 1994). In the 1940s, historian Karl Polanyi took a critical view on the role of property in society that became marginalized during the onset of neoliberal thought three decades later. For Polanyi, the realization of true freedom depended on the state using its powers of regulation and control to establish entitlement for all and he argued that democratic rights were diminished by the power of property owners (Polanyi Citation1944, 2, 265).

When it comes to certain ‘real property’ like land, some contemporary property theorists suggest that the recognition of an individual’s right to dispose of land as an apex right has the effect of inhibiting the practice of other ethical commitments that are also enshrined in law (Shoemaker Citation2020). For example, land may serve a legally dictated cultural value, as a resource to generate a livelihood, as a space for public recreation, or the source of vital public goods thought of as fulfilling basic human rights like housing and food. Property theorists thus argue that a strong ownership model of property fails to address the plurality of values and connections that are clearly visible across a spatial/social landscape, placing the powers of the state to regulate in the name of the common good at odds with the strong affirmations of property (Sax Citation1993). This problem is exemplified by the challenges that environmental legislation faces at the landscape level amidst a geography made up of many parcels protected by strong ownership entitlements (Fennell Citation2011). Some property reformists, like the self-identified ‘progressive property’ theorists, thus stimulate thinking about new conceptions of property to embrace alternative values like ‘human flourishing’, pluralism and civic engagement (Alexander et al. Citation2009).

An important addition to progressive property thinking comes from legal geographer Nicholas Blomley, who stresses that simply urging the creation of new property models misses how property is materialized through the iterative and symbolic actions of people, like maintaining a fence or labelling property boundaries in maps (Blomley Citation2019). Drawing on performativity theory, which argues how the world is produced through discursive acts like language or expressions, Blomley argues that while new legal constructions are important, what needs to also be analysed is the ways that a vision of property are successful at enrolling human and non-human elements into a coherent assemblage (Blomley Citation2013, 34).

Blomley’s contribution helps with thinking of ways that alternative property regimes may be made, because it suggests that the lever for change is not solely some new legal formulation, but rather through the understanding of why and how certain performances of property succeed in enrolling people, institutions and land into a durable socio-legal configuration. Remaking property for agroecology must then seek out the meanings of property ‘not only at the Supreme Court but also at the humble garden fence’ (Blomley Citation2013, 48).

Property regimes and agrarian studies

Sensing the absence of a coherent, redistributive and class-aware land agenda to match the objectives of food sovereignty, Borras and Franco (Citation2012) call for the development of a ‘land sovereignty’ agenda, one that confronts the messiness of property and tenure relations to rebalance the means of production required for meaningful transition to agroecology. The authors, in laying out the land sovereignty concept, call for

[...] a framework with which all those who are confronted by a land question, whether they are in urban or rural areas, or in the South or North can identify with; a framework that can be flexibly interpreted across structural and institutional settings. (Borras and Franco Citation2012, 11)

In Global North contexts, however, where the ownership model of property dominates, the links between land governance and the character of agriculture tend to take a much lesser role in food system reform initiatives. This is a blind spot of the critical agrarian studies literature, leading Sippel and Visser (Citation2021) to suggest it amounts to ‘othering’ in land tenure discussions, where the strong learnings of agrarian studies are applied to Indigenous groups, shifting cultivators, and post-colonial societies of the Global South rather than invoked within the ‘own’ of the Global North.

Land access interventions to benefit farmers in Global North locales thus usually take place within a private property logic (Roman-Alcala Citation2015): through neo-Chayanovian smallholder farmer business models (Smaje Citation2020), agricultural easements that facilitate the partial transfer of use rights to stall development (Morris Citation2008), land trusts or government programs that purchase farmland at market value to lease to farmers on affordable terms (Johnson Citation2008), or through the voluntary production of agroecology-friendly leases or succession plans (Rabkin Citation2010).

Identifying the broader contradictions between ownership-based property regimes and the movement goals of food sovereignty and agroecology, some scholars and activists conclude that there can be no legitimate claims to food sovereignty in settler-colonial states unless alternative food movements confront the underlying property relations that drive developed economies (Blue et al. Citation2021; Kepkiewicz Citation2020; Kepkiewicz and Dale Citation2019; Kepkiewicz and Rotz Citation2018; Trauger Citation2014). Given this context, the motivating question for our analysis of the Scottish land reform is thus, in a liberal capitalist society, how is legitimacy for land redistribution produced?Footnote3

Questions of legitimacy formation, production of state authority, and contested claims over access to resources have long been the focus of agrarian studies (Verdery Citation2018; Mészáros Citation2013; Hall, Hirsch, and Li Citation2011; Peluso and Vandergeest Citation2001; Fortmann Citation1995). Focusing mostly on the Global South, in contexts of ‘legal pluralism’ like post-colonial or post-socialist geographies, this work argues how possession of natural resources occurs through a negotiation between social practices, exercise of political-legal authority, and the types of legitimation processes that validate some claims over others (Sikor and Lund Citation2009). A first strand of work is interested in the relationship between property and access. Here, the emphasis is on how formal entitlements like property rights are less useful to understand the distribution of natural resources than the complex array of social negotiations that shape access, like political capacity to hold land or a practical ability to successfully exclude others (Hall, Hirsch, and Li Citation2011). Actors competing for vital resources thus deploy a suite of ‘access mechanisms’ like the threat of violence, new technologies, or cultural norms, to determine who eventually benefits from a natural resource stream (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003).

The second strand of research concerns how political-legal institutions gain their authority and hold power to influence in part through the making and maintenance of property regimes. Here, researchers show how competition for resources encourages claimants to seek authority to settle disputes, and how they may engage in ‘forum shopping’ to find a suitable entity that will validate their form of claim – in our case, for example, a legislature willing to entertain human rights law to enact a community-based property model (von Benda-Beckmann Citation1981). Another central dynamic takes place: while claimants may strategically shop for a suitable institution to validate their claim, political-legal institutions also have an interest to validate claims effectively, because the power of their authority solidifies as discretion to resolve disputes becomes recognized as settled law (Sikor and Lund Citation2009). Therefore, in their synthesis, Sikor and Lund (Citation2009) link the establishment of well recognized property regimes to state formation and state function. These scholars and their interlocutors offer that empirical work about access, property, and authority ought to focus on the ‘legitimising practices’ that turn a claim to a resource into property via the validation work of powerful or authority seeking institutions. Lund (Citation2020) also highlights the importance of ‘legalisation’,Footnote4 or a process of signalling to state actors to validate a claim and fend off competitors through legal enactments and constructs. For Lund, despite the important role of informal social mechanisms in determining resource use, it is the law’s promise of ‘enduring predictability’ that makes it such an important terrain for engaging in contested claims (Lund Citation2020, 4). The imaginary of ossifying a political claim into a settled, widely enforceable legal right is too attractive for claimants not to pursue.

In this juncture, where proponents of food system reform in most Global North locales struggle to envisage a cogent and actionable plan that meets the standard of Borras and Franco’s land sovereignty agenda, we can find valuable lessons in Scotland’s bottom-up and top-down land reform activities over the last 15 years. There, a community land agenda has worked in concert with multiple acts of Parliament, creating new legal tools for land transfer and governance. The ink is yet to dry on some of the most recent Land Reform policies, yet we argue this case demonstrates how property norms can be transformed within the context of strong commitments to the ownership model. The Scottish case shows a state with the willingness and sense of responsibility to exercise its legislative and political power to intervene in the distribution of land and other assets. Importantly, the land reform agenda demonstrates a legitimation and associated legalization process of intervening in the meaning of property in order to uphold other ethical and legal commitments. Through analysis of this case, we hope to provide insight into effective strategies to challenge the ownership model and position the strategy as a key first step to unlock land for agroecology.

Here, we build on the approach of Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho et al.’s (Citation2018) exploration of eight key drivers that foster the expansion of agroecology.Footnote5 Accordingly, we focus on the mobilizing discourses that influence system change action and ‘establish a clear, easily understandable discourse or frame that helps promote social action in a way that is understood and reproduced by the collective’ (13). Building on the key driver of favourable polices that nurture agroecology, we draw from critical legal geography studies that demonstrates how discourse, geography, and governance arrangements co-construct each other (Braverman et al. Citation2014), generating legal manoeuvres and favourable governance arrangements that can support a land reform agenda. The access-property and power-authority theoretical strands from agrarian studies help view these processes of legal manoeuvring and mobilizing discourses in Scotland as forms of legitimizing practices that have been successfully recognized by Scottish statutory institutions. A focus on governance demonstrates the ways actors making claims for new land entitlements in Scotland pursued a variety of authoritative forums for legitimacy. Importantly, the Scottish case reveals a process of legalization amidst a system of seemingly settled institutional coherence and property regimes. However, for this agenda to facilitate not just new property relations but property relations that enable agroecology, community-based practices are needed to ‘perform’ land use for agroecological, diversified, or organic farming purposes, thereby helping solidify potential access. This line of thinking about the logics that drive the re-imagination of property further centres land as part of efforts to understand agroecological transition strategies for the Global North.

The case of Scotland’s land reform agenda

Scotland’s land reform agenda must be understood against the backdrop of a tumultuous social history. In particular, during the period from 1750 to 1860, inhabitants of rural areas were subjected to waves of reform in pursuit of ‘agricultural improvements’. The rationalization of agriculture was the driving logic of these improvements, in which the potential return on investment for the wool trade transformed much of the uplands in Scotland into felled pasture. Transformations of complex landscapes into reservoirs for wool production changed the local inhabitants’ rights and relationships to the land, creating entrenched poverty and contributing to mass emigration. This period is commonly known as the ‘Clearances’ and is widely represented as a period when inhabitants of the Highlands and Western Islands of Scotland were forcibly evicted from their land. Evocative testimony tells stories of inhabitants being tossed from the land and starving or freezing to death or being burned alive in cottages (Prebble Citation1963). It is not known how many were forcibly evicted, and as asserted in an authoritative account by historian Tom Devine, forcible eviction was only one part of the clearances process which led to a surge in emigration by 1860 (Devine Citation2018).

More widespread than forcible evictions was a generalized loss of status created by the rise of ‘landlordism’ and specifically within the agricultural context, the enclosures system. The enclosures are perceived as an English term and practice but also occurred in Scotland, whereby common land and existing forms of land governance – open fields for grazing in the highland context – were replaced with large-scale pastoral farms and stocked with sheep. These new farmlands were considered to be more productive and accrued higher rents, effectively displacing the pre-existing tenants and inhabitants, many of whom moved to newly created communities known as ‘crofts’,Footnote6 where they had low status as employees in the arduous industries of fishing, quarrying or kelp harvesting. The ensuing impoverished conditions, the risk of famine (as a result of the European potato blight outbreaks of the 1840s), and the general hardship of being on the land all played a role in driving mass emigration (Devine Citation2018).

These demographic shifts were facilitated by laws which asserted and entrenched the property rights of powerful elites, displacing a diversity of land tenure regimes that existed prior. From the twelfth century onwards, Scotland was subjected to waves of feudalism whereby common land held by clans and later by churches was appropriated by the country’s aristocracy and propertied classes. This process was legitimized and upheld by legal instruments such as the Register of Sasines 1617 (from the French saisir = to seize) which gave greater security to land titles; the Law of Entail 1685 which prevented land from being lost even when a land owner went bankrupt; and the Commonty Acts c. 1695, which provided the legislation to divide and appropriate all common lands in the parishes outside the Highland area and not belonging to either the Royal Burghs or to the Crown. This legislation passed through the Old Scots Parliament and was enforced through the law courts (Wightman, Callander, and Boyd Citation2003). It served to strengthen private property rights in Scotland to such an extent that it was considered that ‘In no country in Europe are the rights of proprietors so well defined and so carefully protected’ (Sinclair 1814 cited in Wightman, Callander, and Boyd 2003). Consequently, Scotland did not benefit from the processes of democratic land reform enjoyed by neighbours (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Ireland, etc.) throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

This history has left an enduring legacy and today Scotland still has the most concentrated pattern of ownership in Europe (Hunter Citation2013; Glass, McMorran, and Thomson Citation2019). In 2010, Andy Wightman’s landmark book The Poor Had No Lawyers gave the staggering statistic that 50% of privately-owned rural land in Scotland is owned by 432 landowners (Wightman Citation2013, 148). A recent research review published by the Scottish Land Commission provides more texture to Wightman’s statistic: In 2014, 1125 estates were estimated to control about 70% (4.1 million hectares) of privately-owned rural land. Six hundred and sixty seven of these estates were between 1000 and 10,000 hectares in size and 87 were larger than 10,000 hectares (Glass, McMorran, and Thomson Citation2019). Succession law in Scotland has generally allowed estates to stay intact, suggesting that the long-term pattern of low turnover in estates is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. In this way Scotland differs markedly from other European countries where, typically, the bulk of a country’s land is owned by very large numbers of people and where extensive estates of the Scottish sort are few or non-existent.

The Clearances also had a lasting ecological, landscape and agricultural impact. The practices of clearing land for intensive grazing resulted in massive loss of tree cover, with accounts that by the year 1900 native woodlands represented only 5% of Scotland’s land area (Nature Scot Citation2020). In the same stroke, images of Scotland’s landscapes – empty moorland, open heathery hillsides, grouse moors, and roaming stags – became associated with the ‘classic’ idealized vision of the land (Wach Citation2019). Livestock grazing (sheep and cattle) was presumed to be the only feasible form of agriculture for the Scottish Highlands, particularly in what is known as the ‘uplands’ (or steeper slopes).

Yet this vision belies Scotland’s long history of what can now be recognized as agroecology. A recent doctoral dissertation by Elise Wachs at the University of Coventry, The potential for agroecology and food sovereignty in the Scottish uplands, assessed the historical presence of agroecological food systems and argued that a rich cultivation system was clearly evidenced in Scotland prior to the 1700s (Wach Citation2019; also Wach Citation2021). In the Highlands under the pre-capitalist Clanships, land was held for the good of the clan by clan chiefs, plots of arable production of oats, barley, and vegetables were rotated amongst the clansmen without any sense of individual ownership and production was based on goals of sufficiency rather than productivity. The result was a complex landscape mosaic, where grazing animals found shelter in mixed woodland areas and in the summer months the grazing animals and their caretakers would temporarily establish in upland areas known as ‘shielings’. The diet during this time was diverse, including meat and dairy products from grazing animals, wild game, hazel nuts, foraged mushrooms and seaweed and a rich staple of species now seen as ‘weeds’ today that were used to make grains.Footnote7 Medicinal plants were also gathered and planted. Wach’s analysis of surviving archival data suggests that the Highlands population was able to sustain itself, rather than importing food from outside the region. Part of the impact of the Clearances was not only the subordination of existing communities to a new landlord regime, but also disassembly of the local land governance that formed the basis of an agroecological food system.

The potential for change of these entrenched land ownership patterns was introduced with the creation of a new Scottish Parliament in 1998. One of the Parliament’s early legislative landmarks was the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, described by Hunter as having ‘signalled the emergence of a peculiarly Scottish variant of land reform – one that gives pride of place to fostering community ownership rather than to promoting owner-occupancy’ (See Endnote 10). Over the past 20 years, almost the entire lifetime of the Scottish Parliament – a relatively new institution as discussed in the ‘Governance Structure’ section below – community ownership of land and assets has steadily increased across Scotland. A new wave of community ownership has swept from the Highlands, where it was historically concentrated, through the Central Belt to the Lowlands, and from rural to urban areas.

Overview of legal provisions

What might be called the ‘Scottish Land Reform Agenda’ is a multifaceted process of political ambitions, new Acts of parliament, earmarking of financial resources, and new legal tools aimed at increasing the diversity of land tenure by shifting land from individual ownership to community control. A suite of land reform laws established a number of new entitlements, pre-emptive rights, and asset transfer mechanisms from individual owners to community ownership () First, the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 introduced both ‘a community right to buy land when it comes on the market’ and ‘an absolute crofting community right to buy land’. The 2003 community rights to buy only apply if there is a willing seller, in which case the community right is one of first refusal. The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 and the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 (LRS Act 2016) then created further community rights to buy land even where there is not a willing seller, namely against a present owner’s wishes. Importantly, the 2015 law introduced a ‘community right to buy abandoned, neglected or detrimental land’, if identified as such by the government. It also expanded the scope of the ‘2003 Right to Buy’ to include urban communities; because the original provision only applied to areas with a population of less than 10,000, it had generally only covered rural and village areas (see Reid Citation2019). The 2015 law also established an asset transfer mechanism for transferring assets into community ownership. Part 5 provides a framework for this process: community-controlled bodies, such as community-owned limited guarantee companies, Scottish charitable incorporated organizations, community benefit societies, and community-controlled body corporates, must make an asset transfer request to a landowner that specifies the land, reasons for making a request, benefits to the community, and proposed price that the community is willing to pay. The landowner must review and decide on this request; if it is rejected or granted in different terms, a community body can appeal to the Scottish government.

Table 1. Summary of the Land Reform Acts and their relevant provisions.

Another key innovation – and one particularly pertinent for our agroecology analysis – came when the 2016 law created a new ‘community right to buy land to further sustainable development’, which entered force in 2020. Community bodies will have an absolute right to buy the land if they can demonstrate that the community acquisition will help achieve ‘sustainable development’ on the land. In evaluating whether the proposed sustainable development is in the public interest and is likely to result in significant benefit to the community, the Scottish government must consider a combination of economic development, regeneration, public health, social wellbeing, and environmental wellbeing. The transfer of land must be the only practicable, or the most practicable, way of achieving this benefit; not allowing the transfer must be demonstrated to be likely to harm the community.

The 2016 law also established a new institution to oversee land law and policy, the Scottish Land Commission, and created a new land register, the ‘Register of Persons Holding a Controlled Interest in Land’. The Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement, issued as a preamble to the Acts, recognizes that the right to land brings responsibilities to deliver public goods (including human rights); contains a vision and six principles setting out a human rights approach to land use and ownership; and mandates the newly created Scottish Land Commission to pursue this vision. Through a dedicated land fund, the Scottish Land Fund (SLF), communities can bid for public funds to carry out purchases when exerting their newly granted rights.

The legislation states that a ‘community body’ must have several essential characteristics, which collectively ensure that community owned assets are used for the benefit of the wider community rather than one particular interest group. The community body should: (1) Have a clear definition of the geographical community to which the body relates; (2) Have a membership which is open to any member of that community; (3) Be locally-led and controlled; (4) Have as its main purpose the furthering of sustainable development in the local area; (5) Be non-profit distributing; and (6) Have evidence to demonstrate a sufficient level of support/community buy-in. Regarding point six, in some cases the law dictates that before a community right to buy can be finally exercised, approval of the process must survive a majority voting process. For the purposes of the rights to buy, ‘community’ is defined on a geographical basis, which can be defined by postcode units and/or a prescribed area.

To exercise these new community rights to buy, the Acts stipulate a process of application, notification and judgement. The community group must demonstrate the community’s connection to the land, the proposed use, development and management of the land, the existence of community support and previous efforts to negotiate sale with the landowner. The community body must set out the reasons why it considers that the land is either wholly or mainly neglected, abandoned or ‘harmful’ (the 2015 right) or how they propose to use the land to further ‘sustainable development’ (the 2016 right). A copy of the application must be sent to the landowner and other relevant parties as defined in the Act. In pursuing their community right to buy, community groups can apply to the Scottish Land Fund for support of up to £1 million for asset transfers. An exception was made in the case of Ulva in 2018 when the SLF provided £4.4 million to support community purchase of the island.Footnote8

Impact of the land reform acts

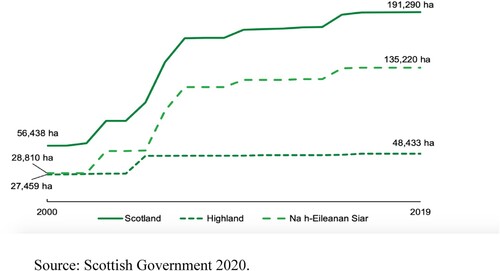

shows a modest, slowly accelerating increase in community ownership since 2003 as a result of the land reform process. According to the most recent Scottish Land Commission audit as of December 2020, 612 assets were in community ownership, owned by 422 community groups, covering an area of 191,261 hectares. Most of these transfers occurred under the original 2003 provisions, with the 2015 and 2016 provisions still to show their full impact. Not all acquisitions are transfers from private owners; sometimes they are from public bodies such as councils, while some are from quasi-public bodies such as churches. For example, a local group, the Ardnamurchan Lighthouse Trust, was awarded £224,900 from the Scottish Land Fund to buy a lighthouse building from the Highland Council in 2019 (Oban Times Citation2019). A local group, Action Porty, was awarded £647,500 to buy a church and its associated halls from the Church of Scotland owners in 2017. Importantly, the majority of community acquisitions to date have relied on the original community right to buy provision introduced in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, where the landowner was a willing seller but the community asserted its right to buy ahead of another buyer. In other words, the new rights to buy have not yet been fully exercised, partly because they are still so novel and implementation is still taking form. The dominant norm of private property ownership may also be highly influential in that communities may be more reluctant so far to force transfers (McKee Citation2015).

Figure 1. The graph shows that the majority of assets in community ownership in Scotland are in the Highland region (135,220 of 191,290 hectares). The Na h-Eileanan Siar region is in the Outer Hebrides, and therefore, by land surface area the highlands and islands possess the largest amount of community land. This is partly explained by transfer of singular large estates in these areas into community ownership.

The impact of the legislation is enhanced by the Scottish Land Commission’s work. The Commission and the six Commissioners (appointed on merit for their expertise on land issues in Scotland and intended to represent a cross-section of land interests) have a remit to review the effectiveness and impact of laws and policies relating to land, and to make recommendations to Scottish Ministers on future land reform. The Commission’s role is:

[T]o stimulate fresh thinking and change in how we as a nation own and use land, and to advise the Scottish Government on an ongoing programme of land reform. As well as providing advice and recommendations for law and policy, we provide leadership for change in culture and practice. (Scottish Land Commission Citation2020, 11)

Their work supports the implementation and impact of new legislation whereby unwilling sellers can be obliged to sell land which is vacant and derelict. For example, the recent ‘Not So Pretty Vacant’ joint campaign by the Scottish Land Commission and SEPA (the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency) drew national attention to the many derelict and vacant sites across Scotland and sought to identify one hundred sites with the best community development potential.

Highlighting the elements relevant for agroecological transition

Having surveyed the relevant legal manoeuvres that underscore the Scottish Land Reform agenda, we now highlight three key elements that are relevant to achieving the re-imagined land relationships relevant for agroecological transition. These elements are (1) new legal tools; (2) mobilizing discourses that legitimize these tools; and (3) governance structures that allow action to take place. Together, they have created a new opening for greater farmer access to land for agroecological production.

Legal tools: a timely application of the human rights framework

The first legal tool evidenced by the Scottish land reform agenda is the application of a human rights framework to intervene in existing property entitlement commitments. Recognition of the connection between ownership of large swathes of land in rural Scotland and community degeneration, inequality, poverty, and homelessness have become more widespread in recent years, partly through Wightman’s writings (Wightman Citation1997, Citation2013), through renewed activism for Scottish Independence in 2014, and partly through a greater localization of human rights concerns and the work of various NGOs to this effect. Connections between ecological crises of climate change and biodiversity loss and large estate ownership have also become more explicit in popular accounts of environmental degradation in the UK (Monbiot Citation2013).

The human rights framework, particularly economic, social and cultural rights, along with emerging environmental rights (such as the right to clean air, water and a healthy environment), is increasingly recognized as providing ‘tools’ for identifying and, moreover, labelling the harms caused by existing patterns of highly consolidated land ownership and for legitimizing new forms of ownership (Gilbert Citation2013). In the Scottish land context, as explained by then-Policy Director of Community Land Scotland, Peter Peacock, ‘The integration of economic, social and cultural rights to the land agenda changed everything. Suddenly there was a vocabulary and a structure to balance the interests involved’ (Shields Citation2018, 3).

To illustrate how this new vocabulary is being invoked, the human rights discourse was used to identify harms or losses on the Isle of Harris, where the community’s viability was threatened by a declining population and the seasonal, unsustainable nature of housing and employment on the island. The situation began to reverse when the West Harris Trust bought over 17,000 acres of land from the Scottish Government in January 2010. In partnership with the Hebridean Housing Partnership, the Trust devoted its development priorities to building affordable homes in the area. By providing access to decent affordable housing, the community ownership initiative had a positive impact on the right to housing. The creation of a mixed business tourism development in a former school building provided several new full-time jobs, supporting the right to work. This regeneration may enable key public services on the island to reopen, and therefore, may have knock-on effects on the right to education, the right to cultural life, and other social and economic rights. There is also potential for community ownership initiatives to support the right to health and the right to food through enabling access to green spaces and supporting food growing projects (Shields Citation2018).

The injection of the human rights legal framework into debates about land was important for encouraging the legality of the land reform Acts, through settling fears that challenging the sanctity of property rights would result in legal challenge, especially in the context of the right to property guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights (McCarthy Citation2020). Importantly, the Scottish land reform model has opted to pursue a path of full compensation, where both unwilling and willing sellers in asset transfer receive ‘market’ value for the asset, regardless of its use history. As land markets skyrocket, some legal scholars have pondered the wisdom of devoting public funds to pay out existing landowners at full market value (Lovett Citation2020; Walsh Citation2021). Notwithstanding this critique, they do not detract from pockets of success within the movement that aim at greater equality of resources by affirming human rights, particularly through the ‘scaling-up’ and realization of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Pre-emptive rights for community land use

Perhaps the central legal mechanism to implement the land reform Acts is the community right to buy, which is a pre-emptive right. As mentioned, pre-emptive rights give the rights holder the first opportunity to buy an asset in question if and when it is to be sold. Also known as first right of refusal, pre-emptive rights significantly intervene in the logics of property markets. A property with an active pre-emptive right claim is not as fungible as other land, resulting in knock off effects for land markets. The land is not as easy to sell immediately, so it can be less valuable and less susceptible to land speculation or development. Perhaps most importantly, pre-emptive rights drastically alter the power relations in the case of a proposed working land sale. Writing about the Action Porty case, Lovett and Combe (Citation2019) write:

Communities can now bring property owners, whether owners of large rural estates or even an entity as historically powerful as the Church of Scotland, to the bargaining table to discuss the transfer of property either in the shadows of the new legislation or under the formal auspices of that legislation. (222)

Thus, the threat of communities pursuing their legal entitlement to force a sale acts as a powerful informal mechanism to increase negotiation and mediate conflicts between owner and tenant or owner and neighbour, whereas local community interests or even existing tenants previously had little recourse to assert their visions of current or future land use if a particular patch of land comes up for sale. The mere spectre of the right being enforced may reshape power relations and deliver a sense of land tenure security without ever having to use the right.

Legal scholars have noted that the community right to buy is somewhat of an outlier in terms of other examples of pre-emptive rights. The usual mechanism is for the state to hold the pre-emptive right, as in the case of eminent domain, a popular tool of expropriation where the state reserves the right to take back land from private owners back into public control (Lovett Citation2010). In the Scottish case, the state acts as a guarantor of the right, but actually passes it directly to the community body, never holding the right itself. Importantly, the pre-emptive rights in the Scottish case are an example of setting forth new values of land ownership and management, then identifying a subset of individuals – the local community – that are sole recipients of these new powers.

Finally, an important legal tool has been the extent to which the Acts describe, categorize and weight certain forms of land use and then apply the new pre-emptive rights in order to transition out of certain land uses. While noticeably absent when it comes to agricultural land use, the Acts do give a greater ability to successfully transfer an asset in cases of vacant and derelict land, or when crofting tenants are involved, or where the current land ownership situation impedes sustainable development of the community. This policy demonstrates a tepid willingness to begin to prioritize the value of certain forms of land use over others. The new rights then are aligned with the Scottish Land Commission’s vacant and derelict land campaigns, creating a new database of vacant lands in each region with the goal of stimulating new land transfers from neglecting owner to empowered community. The community right to buy to advance sustainable development has only become law in 2020 and has not yet been tested. But this new dimension opens up a new terrain for discursive contests over the notion of sustainability, as we discuss below.

Mobilizing discourses

The new land reform provisions did not occur in isolation nor were they legal breakthroughs only. Rather, the process of legislative review of the proposed new laws ran in parallel with building political momentum and citizen engagement with land reform. Here, we identify two important mobilizing discourses: modern-day reparation for a legacy of unresolved land dispossessions and a logic of the Scottish public good. The process of consultation on land reform led to a reflection on the role and power of property rights which was not confined to Parliamentary chambers or courtrooms but co-constructed by mainstream media and public debate. The legal tools deployed to reshape Scotland’s land tenure regimes can be traced to a guiding discursive rationale that ultimately provide the legitimacy for new legal action.

Unfinished business: a Hunterian view of Scottish history

James Hunter’s The Making of the Crofting Community (2018), inspired by E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, lifted the suffering of the highland clearances out of a dominant deterministic conception – a historical narrative that suggested efficient land users remained and inefficient ones emigrated – and into a contemporary popular debate. The Hunterian view of Scotland draws a straight line between the land dispossession of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the existing patterns of land use and pathways to dignified Scottish development today, continuing a long tradition of condemnation of Highland ‘landlordism’. Some of this history has long been evoked as rationales for reparations to the region, and the sense that the Highlanders had suffered injustices was rousing and persuasive. For example, in introducing the Highland Development Act 1965 to the UK Parliament House of Commons for debate, the Secretary of State for Scotland Willie Ross made the following statement:

For 200 years the Highlander has been the man on Scotland’s conscience … No part of Scotland has been given a shabbier deal by history from the 45 onwards. Too often there has only been one way out of his trouble for the person born in the Highlands–emigration. (Ross Citation1965)

This sentiment resonates in modern cult writing such as Wightman’s ‘The Poor Had No Lawyers’ (Wightman Citation2013) where modern estimates of extremely consolidated land ownership, especially in the Northwest of Scotland, are questioned and challenged. In the aftermath of the Scottish Independence Referendum 2014, with energies still running high and communication networks well established, these new accounts of Scotland’s land injustices gained momentum and propelled the call for revived land reform legislation at the Scottish Parliament, leading to the Land Reform Act 2016. Ewen (Citation2020) suggests the simmering presence of land reform legislative action is due to ‘a continual need to adopt the rhetoric of atonement for the Clearances’ (109).

The mobilizing discourse of a Hunterian view of history thus invokes a shared memory of eviction, expulsion and lack of control. As political difference deepens between Westminster in England and Holyrood in Scotland, a growing call for unlocking the productive potential of Scottish land for the Scottish people engenders a wide legitimacy. Of course, there is an important counter-discourse of the Scottish Highlands as a beautiful pristine habitat, made more special by its emptiness and trademark dominance of grouse, heather and stag. Nevertheless, the coherent discourse of righting a past wrong was strong enough for Scottish parliamentarians to act upon its force. There is no mention of the highland clearances in the Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement, nor the Land Reform Acts themselves. The legal discourse is always forward looking, but the Hunterian view of history is embedded throughout and was expressed often in legislative and public debates. For example, Roseanna Cunningham, a MSP of the Scottish National Party between 1999 and 2021, in her opening remarks to the Scottish Parliament debate on land reform in 2019 said,

Our relationship with land is unbalanced as has been for several hundred years. Too much of our land is owned by too few people, and too few of us are able to influence decision about the use and management of land […] The patterns of land ownership in Scotland are unlike anywhere else. There are complex historical reasons for this, but it is at the very heart of the Scottish government’s land reform agenda. If we do not fundamentally alter these patterns and change the framework that allowed them to develop and exist for so long, our land reform ambitions will ultimately be thwarted. (Cunningham Citation2019)

This discourse tends to align with high level calls for Scottish independence, where national sovereignty is expressed through new laws to gain land sovereignty in opposition to the historical legacy of English-influenced enclosures.

Land as a public good

The land reform Acts grant new powers and funding to transfer ownership of land and other assets, but only if a set of criteria are met, in which the transfer demonstrates the possibility of improving the public good. This is set out most strongly in the first principle of the Land Rights and Responsibilities statement, which indicates any action regarding land should ‘fulfil and respect relevant human rights in relation to land, contribute to public interest and wellbeing, and balance public and private interests’ (09, italics added). The appeal to human rights puts forth a sense that the current land tenure regime is unbalanced and may even be preventing the fulfilment of rights beyond that of peaceful possession of property, like economic, social and cultural rights (Shields Citation2018).

The public goods and human rights discourse manifests most strongly in the land reforms in two ways: what types of entities benefit from the new rights and what types of land uses are preferred. The first is the prioritization of community ownership. The community form was one that organically emerged from the crofting model, prior to any new legislation, and through tenure experimentation in the Northwest of Scotland, such as when the crofters and tenants of the Isle of Eigg succeeded in a buy-out of the island after waves of consecutive ownership transfers. The legal tools are designed to expand and institutionalize such bottom-up land tenure experiments. In addition, the Acts assign normative value to certain land use forms, deeming vacant and derelict lands as infringing public goods and introducing the concept of sustainable development as a virtue that landowners must facilitate, or be forced to transfer their land towards this end.

Governance structure

As Hunter, one of the foremost experts on Scottish land history points out, efforts at land reform throughout the twentieth century were repeatedly thwarted by the absence of democratic power in the form of state institutions.

[Re]form has so far been, by European standards, piecemeal, hesitant and inadequate. This results, in turn, from Scotland having always lacked a government with the courage to take on vested interests of a sort most other countries were prepared to confront successfully long ago. (Hunter Citation2013)

The Scottish Parliament was created by an Act of the UK Parliament in 1998 along with other devolution developments for Northern Ireland (Northern Ireland Act 1998) and Wales (Government of Wales Act 1998). These settlements were introduced whilst the Labour Party was in power in Westminster in a bid to decentralize power and in a bid to appease growing demands for increased power amongst the regions of the UK. Devolution was designed to give the Scottish people ‘a greater say over their own affairs’ through participatory democracy (The Scotland Office Citation1997, 1), echoing calls made in the final report of the Scottish Constitutional Convention (SCC Citation1992).

There was also an aspiration that devolution could foster a more consensus-based and less executive-dominated style of politics. The new Scottish Parliament differed from the UK Parliament in its unicameral nature (there is no unelected second chamber resembling the House of Lords); the use of proportional representation to elect the new Scottish parliamentarians; cross party committees on key issues (including land reform) intended to facilitate consensus-based politics; and codified constitutional commitments to human rights. The new parliament’s legislative design goes some way towards explaining why the Scottish Parliament was able to pass a significant body of law on land reform in a relatively short period of time. Since the advent of the Parliament in 1998, at least twenty-one Acts have been passed that contain land reform measures.

The effects of these early reforms were significant especially in addressing the loss of status of inhabitants widely believed to have stemmed from ‘landlordism’ in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Yet in order to accomplish deeper change, the sense that property rights were intransigent had to be grappled with. The problem was that property rights in Scotland, as in much of the world, had come to represent apex constitutional rights. To challenge this hegemony, historical hierarchies within law and culture had to be questioned and human rights provided the legitimate basis on which to do this work. The Scottish Parliament was designed, like contemporary European Union institutions, with human rights at its constitutional core. The new legislature was attached to the modern international human rights movement through provisions within the Scotland Act. Section 29 (d) and s. 57 (2) limit the powers of the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament to make laws which are not compliant with the European Convention on Human Rights. Under section 58 of the Scotland Act 1998 in conjunction with Schedule 5, para 7(2), Scotland is obliged to respect its international obligations, including United Nations human rights treaties.

This constitutional basis enabled the use of progressive interpretations of human rights, as these develop within the UN human rights bodies. In this regard the constitutional basis of the Scottish Parliament differs fundamentally from that of the UK Parliament, which operates on an ancient doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty – meaning that the parliament is not limited by any external laws and institutions, and can repeal its own laws, theoretically without limitation. The Scottish Parliament’s alignment with the international human rights movement enabled a recasting of property rights within a wider constellation of citizen entitlements and state duties. Early party political protests that the Scottish Government’s land reform plans would interfere with the ‘right to property’ were easily countered by reference to legal provisions (Shields Citation2014). A reframing of the right to property as one amongst many human rights, including economic, social and cultural rights such as the rights to food, housing and health, enabled a justification of interference with property rights (McCarthy Citation2020).

In evidence hearings and consultations leading up to the passing of the Land reform Acts, the need to address the unfettered power of property rights were directly addressed. It was acknowledged that the prevailing ‘asymmetry of property rights’ must be grappled with if land was to be used to address urgent social needs. Consequently, governmental commitments to the UN International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural rights became key to the rationale for land reform and are referenced within the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015, the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016, and in the Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement 2016.

A land access roadmap for agroecological transition

In this section, we work through what the law reforms may mean for agroecological transition in Scotland and then consider how similar reforms might progress in other Global North regions with strong ownership model property relations and different histories.

For Scotland

While the legislative aspects of the Scottish land reform agenda are recent, with Part 5 of the Scottish Land Reform Acts only coming into force in spring 2020, they have important implications for transition into agroecological production and transition out of more productivist land use in Scotland. First, transition out of industrialized production may not be directly facilitated by the land reform acts. For the past few decades, the Scottish government has protected and strengthened the rights of agricultural tenants. Most notably, the 1991 Agricultural Holdings Act gave a large number of tenant farmers the absolute right to buy their properties, in the hopes of improving landowner-tenant cooperation and investment, in the context of Scotland’s highly concentrated landholdings. The Act also required that tenants must be adequately compensated for any improvements they make to the property while farming if they later lost their leases. As a result, being an agricultural tenant under the 1991 Act can grant rather secure tenure, compared to other agricultural leases that do not contain the right to buy or commitment to burden sharing.

Despite some important protections for tenants, agriculture is noticeably absent from the land reform laws. Agricultural production (including rough upland grazing areas) accounts for 80 percent of all of Scotland’s land (Scottish Government Citation2019). Yet working agricultural land has so far not been considered eligible for compulsory purchase on the ground it has been abandoned, neglected or detrimentally used, and this position is unlikely to change in the future given the layers of legal protections that existing governance of productivist farmland presents.

The Scottish Land Commission, which advocates for agrarian change in Scotland with regards to ownership and tenure of agricultural holdings, noticeably plays a neutral role with regards to agricultural practices. The SLC has produced official guidance and studies about pathways for new entrants into agriculture, which explore possible models for increasing the availability of farmland such as contract farming; licensing; tenancies; partnerships; and share farming (McKee et al. Citation2018). Most of these are simply ‘joint venture’ solutions between landowners and farmers, and do not involve land transfer. More important, the SLC does not engage with agricultural sustainability, so it has been neutral with regards to agroecology as a desirable direction for land management. Additionally, an emerging perverse outcome of the land reform agenda has been the freezing up of leased farmland. Owners, fearing new waves of pre-emptive rights for agricultural tenants, appear to prefer to take farm management in hand, or leave the land unfarmed or lightly farmed, rather than provide access for new entrant farmers.

Yet, whether intensively farmed or lightly farmed agricultural lands could meet the new criteria for community acquisition to advance sustainable development is worth exploring in order to further agroecology. If particular farming practices can be considered unsustainable, the most recent provision of the Land Reform Acts creates an untested opportunity where a legal case could be made that land should be acquired to make improvements towards sustainable development through agroecological or diversified farming production aimed at reviving Scotland’s lost heritage of vegetable, fruit, and weedy plant foods (Wach Citation2019). The use of new land reform tools by communities, if they choose this pathway, to transition out of historic conventional patterns of agricultural land use in Scotland remains experimental. To take this route, communities living in and around industrially farmed areas would have to form a trust or community organization with an agroecological or diversified production vision for future land use and contend that they have an absolute right to buy because the current farming model and its social and environmental impact on a particular area is preventing the community’s right to pursue sustainable development.

Given the current state of knowledge about the significant, harmful impacts of industrial agriculture on the environment and society, this certainly seems like a possibility, but would require a widespread shift in Scotland’s approach towards visions of sustainable agriculture. This shift may also require building on Blomley’s concept of enrolling people, institutions and land into a durable socio-legal configuration through material and symbolic actions to help Scottish agroecologists and other alternative farmers start to bridge the gap between legal opening and agrarian reality.

Transitioning land into agroecological use: crofters, new agroecological farmers, and community driven farmland tenure

Two key developments point to an emerging community practice for transitioning land into agroecological use. Prior to the land reform Acts, crofting offered a potential entry point for new agroecological farmers to find suitable land. Modern crofts tend to be smaller parcels of rural land with secure use rights, as historically a crofting community relied on the food provisioning of multiple adjacent units. Crofting is a way of life unique to the Scottish Highlands and islands. Historically crofting usually consisted of a small amount of arable production and pasture for livestock, plus access to community grazing land (for sheep predominantly) shared with other adjacent crofts. Crofts range in size from less than 0.5 hectares (ha) to more than 50ha but an average croft is nearer 5ha. Although often romanticized, crofting is a notoriously difficult way of life, and a ‘crofting community’ arose out of necessity following forced relocation and based on class struggle (Hunter Citation1976), although this account is disputed (MacKinnon Citation2019).

Much of the original (pre-land reform Acts) activism around community land ownership involved crofting land, like the Isle of Eigg buyout and most famously the Assynt Crofters Trust, where a group of crofting tenants organized to block the sale and subdivision of the land they collectively were renting, and formed a community owned estate of 21,000 acres (Chenevix-Trench and Philip Citation2001). In the appeals to recognize their claims, community members and crofters invoked symbolism of reclaiming land of their forefathers, held numerous traditional musical gatherings, and presented alternative visions of how they work steward the land if indeed they would have communal ownership. The first land reform law in 2003 built on this community demand and granted the community right to buy for crofting land only. Prior to this, crofters already had some legal protection for their land but simultaneously were tightly regulated in the case of certain pieces of agricultural land associated with historical crofting community areas. For example, the owner of a croft must live on and ‘work’ their land or be penalized or disenfranchized by the Scottish Crofting Commission. Because crofting land restricts speculative development, tends to persist in smaller parcels, and requires strict government oversight, crofts are where the most agricultural innovation has occurred in recent years, as new entrant farmers find that buying or leasing a croft can match their budget and landscape vision (Sutherland and Calo Citation2020).