ABSTRACT

The term ‘Shadow State' refers to illicit extraction and patrimonial resource grabs. This paper documents the history of Cambodia's Shadow State and its interlocutors in the timber trade, drawing connections to contemporary timber extraction involving syndicated logging, government officials, and USAID. We use this to discuss three interrelated things: How infrastructures for Shadow State extraction morph with policy changes and persist through time. How climate change politics connect a long history of violent resource extraction, and how the ‘shadow’ state is knowingly hidden within the modern state. The implications of our findings for social and environmental justice cannot be ignored.

1. Introduction

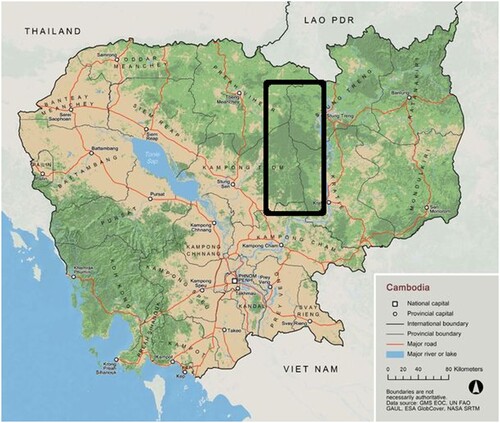

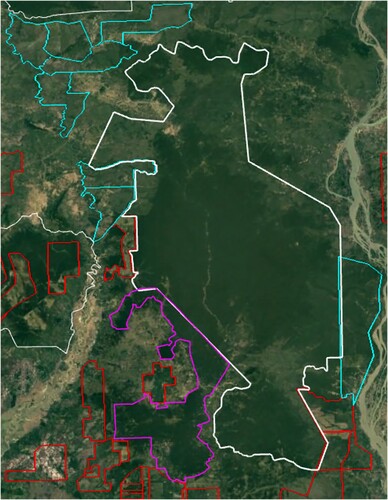

Cambodia’s resources opened to the global market in the late 1980s amid continuing civil war and instability.Footnote1 The promise of the Paris Peace Accords in 1991 began a 30-year process marked by various strategies for territory control, resource extraction, and international investment (Le Billon Citation1999; Hughes Citation2003; Biddulph Citation2010; Käkönen and Thuon Citation2019). In line with donor-driven global economic policies promoting economic growth, aggressive initiatives produced strong GDP performance of 7–10 per cent growth each year since 2000, accompanied by acute inequalities and environmental degradation (Ear Citation2007; Cock Citation2016; Springer Citation2015). The climate change politics of the sustainable development paradigm are a direct response to the ecosystem destabilization of economic development and attempt to nest extraction and all its development projects neatly into a system that can be sustainable, growth producing, and profitable (Franco and Borras Citation2019; Borras, Franco, and Nam Citation2020). In Cambodia, entire landscapes are being grabbed for production and conservation. The USAID Greening Prey Lang project involved in our case study is one such ‘landscape’ conservation initiative that captured 3.3 million hectares of forest across an area of multiple land uses (), including river systems, industrial plantations, and untenured small holder claims.

Figure 1. Prey Lang Extended Landscape (Image taken from, USAID and TT Citation2021, 43).

Whether conservation project or nation state, the map and the bureaucracy needed to make it, the global climate change policies to which it attaches, and the laws that make it possible are often understood to represent the ‘real’ thing. The reality-making potential of both policies and maps often conceal the fiction it might represent (Thongchai Citation1994; Shore and Wright Citation1997). In this way, a constitution, a collection of national laws rationalizing land, forest, waterways, and trade, a map, an election, and a leader can be understood to represent a real state – regardless of how each artifact corresponds to material processes in real time. Logging in Cambodia’s protected areas, for example, is against national law and yet there has never been a time in the history of the Royal Government of Cambodia without logging in protected areas involving national-level officials (GW Citation1999, Citation2007; Hughes and Un Citation2012; Cock Citation2016; Global Initiative Citation2021). The highly coordinated structures through which this happens have been refered to as a Shadow State, or shadow economies (Le Billon Citation2000; Billon and Springer Citation2007; Milne Citation2015; Mahanty Citation2019). In this context, which state is the ‘real’ state, the one of constitutions, laws, and policies or the one that has tangible effects on the ground, depends on one’s subject position. For international and national elites, development donors, conservation organizations and their staff, and often social scientists, it is the laws that make the state. For the inhabitants and citizens of the ‘state’ it is the ability to control access to resources that makes the state (see also, Lund Citation2016), and this happens both within and without supporting bureaucratic and legal structures.

James Ferguson (Citation2006) suggests that the ‘shadow state’ mimics the donor (colonial) states by way of both aspiration and representation, and further, that without the donors, shadow state extraction would not be possible. Close examination of this process shows how the contemporary ‘shadow state’ seems to operate at the dynamic interface where the violence of sovereign law (Derrida Citation2002; Agamben Citation2005) meets the primitive accumulation that founds the capitalist state (Marx Citation1976). Based on our findings, we argue that these are not only interdependent processes, but may be inextricable. The evidence we put forward shows how Cambodia’s ‘shadow state’ not only ensures extraction and the capitalist transformation of landscapes, but also creates the need for donor projects that can ‘strengthen’ state functions (see also, Hutchinson et al. Citation2014; Asiyanbi and Lund Citation2020). The illicit extraction of the ‘shadow state’ is not hidden from donors and people living in extractive landscapes, but it is hidden by donor laws and policies, which persistently validate exclusionary practices through recognition (Reno Citation2000; Le Billon Citation2000; Ferguson Citation2006). National and global citizens and investors are often in the dark about the actual effects of laws and bureaucratic structures. It is significant that in developing countries across the globe, the development donors often draft the laws put into action by ‘legitimate’ national governments. The implementation and interpretation of these laws varies, but the legal framework is typically supplied by donor organizations.

The case we unpack here articulates this dynamic mimesis with all of the development strategies put forward by development donors since Cambodia’s United Nations-sponsored elections in 1993. These include Forest Concessions, Economic Land Concessions (ELC), Community Forests, Reforestation, REDD+, and Protected Areas. All of these coagulate in USAID’s Greening Prey Lang project, which is building governance capacity, increasing local livelihoods, and securing forest financing within the Prey Lang Extended Landscape (). We detail the simultaneous appearance of USAID’s Greening Prey Lang project and a syndicated logging operation run by a former Forest Concessioner in collaboration with Cambodia’s ruling elite in the same landscape, to discuss the intricacies of an encounter between the shadow state and the development donor. This encounter reveals many things. What we draw out here is that not only can several enclosures occur in the same place simultaneously (Peluso and Lund Citation2011; Hunsberger et al. Citation2017), but that territorializations have histories that are distinctly non-linear (Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018; Borras, Franco, and Nam Citation2020), both coming before and extend beyond the life of the project (Eilenberg Citation2014; Woods Citation2018). And they are all embedded within policy frameworks that consistently prove to be inadequate for most local situations, reproductive of unfounded myths, and unchanging through time (Le Billon Citation2000; Asiyanbi and Lund Citation2020; Delabre et al. Citation2020).

After almost 10 years of direct collaboration with Cambodia’s forestry sector, USAID continued to ‘fall prey’ to the manipulations of ministry actors (see, Work and Thuon Citation2017). In the case we describe, it took almost two years of constant advocacy for USAID to publicly acknowledge the extreme extraction going on inside the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary and withdraw their support (Khuon Citation2021a, Citation2021b). During that time USAID continued to fund Cambodia’s Ministry of Environment (MoE), to populate the Greening Prey Lang Facebook page, and to publish feel-good ‘Exposure’ stories (GPL Citation2021). All the while, the MoE (and other ministry actors, police, commune officials, and private security forces) protected company loggers while entering the wildlife sanctuary, excluded monks, and local citizens, and the organized community patrol group, also canceling a community-led tree ordination celebration. In addition, the MoE established a new civilian forest patrol group, using USAID funds and conservation organization staff, that actively excluded the existing civilian forest patrol group, the Prey Lang Community Network (PLCN). MoE made multiple public statements during this time to tout collaboration with both USAID and with forest-dependent communities amid publicized reports of wide-scale deforestation and activist repression in Prey Lang (Nov Citation2021; Mao Citation2021). When USAID made their first public statement in response to criticisms, they claimed that Prey Lang’s ‘forest loss’ is the result of ‘weak law enforcement and opaque governance systems’ (USMC Citation2021a, 1). This is a powerful ‘gray zone’ of climate politics (Franco and Borras Citation2019), where donor discourses palpably change the nature of the thing described in ways that at once legitimize and blame the national government, while cleansing the roles of private industry, conservation, and climate change mitigation initiatives in ‘forest loss’. The impunity with which USAID, MoE, and company actors approached the evidence of large-scale illegal logging in Prey Lang (GI Citation2021) is worthy of some pause. We will open that discussion at the end of the piece.

When the various processes of donor-facilitated state territorialization are taken together and viewed from within a single spatial and temporal moment, we can see their non-linear and intertwined nature. In our case, for example, Forest Concessions facilitated a solid network of collaborating elites, disposed local actors toward the trees-for-cash economy, and made a ‘degraded’ landscape grabbed for ‘reforestation’, which became a timber laundering site with a sawmill in the eastern forest. Because the forest remains so rich in this region, it also became a site for industrial conservation and forest carbon projects. The particulars of this case study force all these dynamic processes into a single conversation that illuminates some unexpected connections, like those between forest concessioners of the 1990s and contemporary illicit extraction, and also adds weight to already known processes, like the entanglement of ongoing illicit ‘Shadow State’ timber extraction (Milne Citation2015) with international investors, donor agendas, and big conservation (see also, Milne Citation2019). Of growing concern is the extent to which ‘shadow’ activities are accommodated, legitimized, and cleansed under the funding and policies of international donor and conservation actors, whose ongoing willful blindness and aspirational policy adjustments continue to shield the elicit extraction from the general public and investors (Work et al. Citation2019; Milne Citation2015; Mahanty Citation2019; Bovensiepen Citation2020).

We begin in the next section with a discussion of the ‘Shadow State’ and its intimate co-constitution with the donor institutions that make the state capture of resources possible. From there we will introduce the Prey Lang forest, its history of occupation and its transformation into a state-owned economic entity, introducing the key players in our case study, the PLCN, USAID, and the Think Biotech co, ltd, and other minor players, after which we will discuss the case beginning in November 2018, when USAID’s Greening Prey Lang conservation project began and when Mr. Lu Chu-Chang became the new owner of the Think Biotech co, ltd. In conclusion, we will stitch together shadow state activities and end the piece with a discussion of the ‘absurdly difficult, but not impossible’ (Borras Citation2019, 3) pathways toward social and environmental justice.

2. Framing weak and shadowy states

The ‘Shadow State’ has two meanings in social science literature. We refer to those processes coined by William Reno (Citation1995; Citation2000), which refer to organized resource extraction carried out by recognized state actors that occur ‘behind the façade of laws and government institutions’ (2000, 434). The other use of the ‘Shadow State’ refers to the plethora of NGOs and other international organizations involved in supporting state functions and seems to have been coined in reference to western industrialized states (see for example, Trudeau Citation2012). There is an irony to these two uses of the same term, worthy of note but beyond our scope as we proceed to discuss the conundrum of extreme extraction and ‘Shadow State’ economics that operate outside of donor-created laws, but (ironically) inside of donor-organized projects. This paradox of the rational modern state of affairs, in which the corruption and violence of primitive accumulation cannot be ensconced within the laws of statehood and sovereignty (Agamben Citation2005; Lund Citation2016), is obscured by the idealized imaginaries of development, conservation, and sustainable progress. This creates a bifurcated ‘state’, one side of which is a supposedly ‘real’ state of laws, policies, and bureaucratic structures that rationalize landscapes and another that exists in the shadows of this façade violently capturing resources and cultivating collaborating elites with impunity.

In Cambodia, timber extraction is a primary driver of ‘shadow state’ activities that operate through illicit, corrupt, and patrimonial networks of state actors. Le Billon (Citation2000) first discussed this in the Cambodian context after the transition to a market economy from 1989 to 1999. He notes that the ‘idealized’ legislation put forward by the international community (unintentionally) ‘legalized’ the shadow state politics of the national government (Le Billon Citation2000, 795), which were already relevant under the legal structures of the Vietnamese from 1979 to 1989 (Global Witness 2015). In the era documented by Le Billon, these shadow activities were part of what smoothed the peace process, as warring factions came into contact, and then contracts, over the timber deals that helped fuel the war. They did not, however, fill state coffers and were highly destructive to forest resources and local communities. They did drive GDP. Both Andrew Cock and Caroline Hughes document the importance of this growth to the image of international development and how it forestalled donor critiques of the coup by Hun Sen in 1997 (Hughes Citation2003), and of the anarchic forest destruction of the subsequent Forest Concession scheme (Cock Citation2016).

Up until the present in Cambodia, development initiatives and the policy landscapes that support them are created within donor agendas, developed by legal and policy experts who assist in drafting governance policies and the laws that uphold them. Through these acts, the sovereign state of the Kingdom of Cambodia was established and bound to particular governance protocols. This is not to say that national governments have no agency, policy drafting is an iterative process in which national actors adjust and frame the documents toward their own agendas – sometimes even retaining language in the unofficial English version that is omitted or altered in the official version published in the national language (see for example, Faxon Citation2017). Legal experts attempt to include language that upholds internationally agreed-upon frameworks of rights and sustainable practices, while at the same time ensuring economic growth and business-friendly environments, but the state remains a mediator between capital and nature and donors are bound to accommodate national agendas (Robbins Citation2008). The resulting landscape of extraction and corruption has been described as a Machiavellian arrangement of expediency within which the larger goals of peace and development can proceed (Biddulph Citation2014). This political strategy depends on the willingness of donors, investors, and other states to ‘recognize the façade of formal sovereignty’ created by the laws, maps, and elections of (illicit, law-breaking) national governments (Reno Citation2000, 437; see also Ferguson Citation2006).

We do not suggest that international actors are solely responsible for the failures of development projects (Scott Citation1998), and our description of the case below attends to the ‘complex, relational reproduction’ of relations at the frontier zone (Barney Citation2009, 150). Indeed, the ways that donor agendas often hinder state capacity for autonomous action are important, as well as the ‘structural dependency’ these relationships create within which state actors must creatively negotiate their own vision of development (Hughes Citation2003; Hagmann and Ṕeclard Citation2010). Nonetheless, we are concerned with the crucial role played by donors in creating the imaginative spaces of laws, boundaries, maps, and policies that make a recognizable reality into which investments can flow, as well as their complementary work of ‘strengthening’ the governance of ‘weak’ state actors (Hansen and Stepputat Citation2001; Hutchinson et al. Citation2014; Asiyanbi and Lund Citation2020). It seems strange to refer to the Cambodian state as in need of strengthening, especially when state-initiated coordinated actions can be swift and effective across many realms of governance. The 2012 land titling scheme, the trials and dissolution of the main opposition party in advance of the 2018 election, the enforcement in 2018 of the Law on Associations and Non-Governmental Organizations (LANGO), and the swift, effective exclusion of local forest activists from their ancestral lands that we describe below, all show functioning institutions, binding laws, inter-ministerial coordination, and the rapid deployment of actors to address issues on the ground. In this context, the framing of expedient corruption as weak governance in need of strengthening by the international community may call for deeper scrutiny (see, for example, USAID’s most recent Country Development Cooperation Strategy, USAID Citation2021).

Of course, any state can be strong in some respects while weak in others (see, for example, Creak and Barney Citation2018 on Laos). Cambodia is certainly weak in terms of developing expensive social infrastructure to protect society from the externalities of extreme extraction and expanding wealth and is weak also in terms of building expensive hard infrastructure for effective resource extraction. But in terms of taking charge of resource extraction and channeling the wealth that comes from it, the Cambodian state is neither weak nor fragile. The capacity and inclination to take charge of resource control precedes legitimacy and authority and can be understood to create the state (Lund Citation2016; Rasmussen & Lund Citation2018, 388), but in the case, we describe it is in dynamic interaction with the donor imaginary of what a state is and how ‘development’ should proceed (Hansen and Stepputat Citation2001; Asiyanbi and Lund Citation2020). We show how the ‘shadow state’ is only possible behind the façade of laws and bureaucratic infrastructure that create the sovereign state, which creates an unmarked space for its exception (Agamben Citation2005). This façade cleanses the violence of resource capture and obscures the ‘chaos and corruption’ at the resource frontier (Hutchinson et al. Citation2014, 27), but also creates a scapegoat upon which to blame the violence and injustice of that process (Bernstein Citation1990; Ferguson Citation2006).

In contemporary Cambodia, ‘shadow’ economies are deeply entwined with formal institutions (Milne Citation2015; Mahanty Citation2019), and our case study adds to the story of illicit extraction. It also makes clear that the corruption and the social and environmental destruction it brings can no longer be considered a shadow of the real, it seems rather to be constituent of the global market and the modern state. Suggestions that the ‘shadow state’ is an aspirational performance in which developing mimics developed in an ‘uncanny combination of likeness and difference’, might be well founded (Ferguson Citation2006, 22). It is the ability to divert attention away from the costs of growth, rather than the ability to actually minimize or eliminate those costs that is the triumph of the developmental state (Hughes and Un Citation2012, 23). In the next section, we hope to make this more visible by describing the situation in the Prey Lang Forest where we collected data for this paper.

3. Research landscape

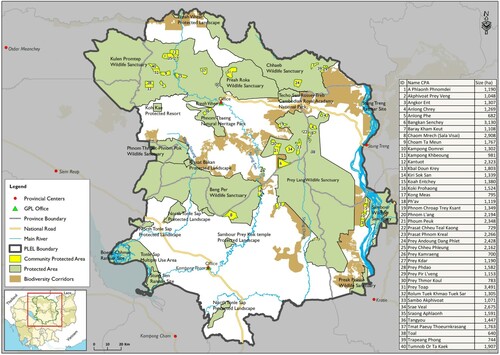

At the end of the capitalist wars in the early 1990s, Prey Lang was a vast, contiguous forest landscape, and remains the largest lowland evergreen forest in mainland Southeast Asia. Once comprising over 600,000 hectares, the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary is currently bound into 432,000 hectares of designated protected area, established in 2016 ( and ).Footnote2 Sitting at the intersecting boundaries of Steung Treng, Preah Vihear, Kampong Thom, and Kratie provinces the forest is home to over two-hundred thousand families of Indigenous Kuy and Khmer subsistence farmers (and since 2016 many more migrant families who have yet to be officially counted).Footnote3

Figure 5. The Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary 2021. Protected Area in white, Tumring REDD+ in purple, and the logging syndicate of Think Biotech, Thy Nga, PNT, and HengFu Sugar ELCs in blue.

The people living in and adjacent to the forest, until the events described in this paper, relied heavily on harvesting liquid resin from the forest. This widespread practice (in 2010, 80–90% of forest-based families owned resin trees) yielded an annual gross income of over three-thousand USD (Dyrmose et al. Citation2017), this income is supported (less each year) by local knowledge of forest plants and animals that are used for medicine, food, and craft materials. The tools and ritual knowledge for hunting and managing forest resources also remains part of the local economy (Turreira-García et al. Citation2017; Work Citation2018). Research for this paper was carried out independently by the collaborating authors, but the first and second authors each conducted engaged research collaborations with members of the PLCN, civil society organizations, and academic researchers starting in 2014 and continuing to the present (Hunsberger et al. Citation2017; Theilade et al. Citation2020; Work et al. Citation2021; Theilade et al. Citation2022).

Each author has been engaged in forest-related research in Cambodia for many years and the case-study data presented here is from November 2018 to June 2021. Data collection involved ground research, interviews with PLCN, Tetra Tech and USAID representatives, Think Biotech representatives, field research in Prey Lang and at Think Biotech conducted by the first author, data collection from trained PLCN researchers, GIS and satellite data collated, analyzed, and disseminated by the second author and researchers at University of Copenhagen, and interviews with government officials, UNDP, CI, and WCS conducted by the third author. These data along with extensive desk research over the years into the various development, conservation, and climate change oriented policies and projects inform the evidence we provide here to discuss the dynamic confluence of three decades of ‘development’ strategies in the gutting of the Prey Lang forest. We proceed here to describe the Forest Concessions of the civil war years, the Prey Lang Community Network that emerged out of that chaos, the Economic Land Concessions (ELC) of the post-civil war era, and the landscape conservation initiatives and climate change strategies of contemporary development as they have each come to rest in the Prey Lang Forest ( and 5).

4. The confluence of prey lang enclosures

4.1. Forest concessions

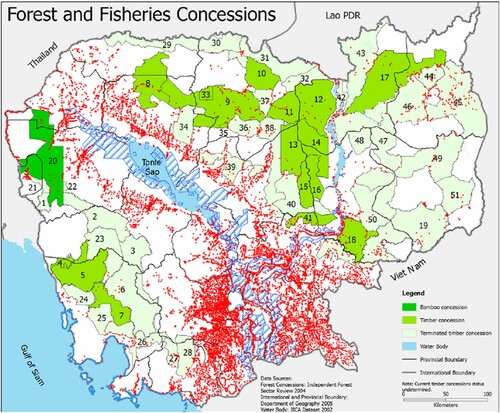

The first act of development instituted Forest Concessions, which legalized and rationalized the informal civil-war era timber trading by allocating seven million hectares of forest land to a small number of private concessionaires between 1991 and 1998 (). Le Billon (Citation2000, Citation2002) describes how legalizing the existing system of forest exploitation helped bring warring factions together in shared profit-making, but also reconfigured power networks through shadow state systems in collaboration with international corporations who recognized their sovereignty, broke their laws, and shared the profits. This rationalization of the forest followed international standards with laws making the state the de jure owner of forest land and outlining the sustainable harvesting of timber (Cock Citation2016). Le Billon (Citation2000) suggests this was an ‘idealized model of timber exploitation’, that assumed regulated markets, a working democracy in which citizens demand accountability through elections, and a ‘state’ that would act toward the social good (795). This imagined ‘state’ did not reflect local conditions, in which ‘legal mechanisms and the misuse of public authority, together with overt coercion and violence’ relieved local residents of their rights to forest resources (797). By dis-attending these processes, the international community actually legalized shadow state politics in Cambodia through the recognition of a state that governed through power rather than rights.

Local people were also relieved of their rights to access forest resources in 1993, using policies that excluded both industrial actors and local users from twenty-three protected areas that captured about 20% of Cambodia’s land cover by royal decree (Le Billon Citation1999). The Prey Lang Forest was not among those protected areas, and the above map shows it entirety awarded to logging concessions (), which operated with little regard for the environment or the local populations often with military support and cooperation from government officials (GW Citation1999; O’Connel and Saroeun Citation2000). In response, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund actors suspended, then restored loans. Donors restored funding under condition that the RGC implement forestry reforms (developed and paid for by donors) and begin to ‘use the country’s forest capital stock to its greatest development advantage’ (WB, UNDP, and FAO Citation1996, 16). This uncritical support presents state actors who mismanaged a sound system due to their lack of sufficient training and effective systems (cf Le Billon Citation2000). At the same time, external reports suggest highly sophisticated networks of actors harvesting and shipping timber to global markets (Barney Citation2009; GW Citation1999).

By the year 2000, the Forest Concession system’s continued failure to produce tax revenues, control extraction, or to enhance other types of development projects in the country prompted the World Bank to create the $4.8 million ‘Forest Concession Management and Control Pilot Project’, to clean up the industry, ‘strengthen’ Cambodia’s forest governance sector, and teach officials and concessioners about the rights of local inhabitants (WBIP Citation2005, 9, see also, Billon and Springer Citation2007; Cock Citation2016). The language of the policy document is as if the shadow economies do not exist and forestry officials are diligently, but ineffectively trying to enforce the law and protect their citizens. The document erases the ways that RGC officials were intimately involved in the oppression and dispossession of local forest users (see especially, WB Citation2005, 17). Despite the creation of elaborate governance systems, the scheme failed, but only after loud and prolonged local protest that featured PLCN and forest community members in the Prey Lang region demanding to see management plans that neither, companies, World Bank, nor RGC actors could produce (Pyne Citation2004; WBIP Citation2005, Citation2018).

Le Billon (Citation1999, Citation2000) points to the naïve idealistic nature of international systems and their failure to take local dynamics into account that drove the failures in Forest Concession reform efforts. Cock suggests that the persistence of inadequate policy reform was due to collective denial that the forest concession system itself may be the problem (2016, 127). Our data show how features of that system persist in both the landscape and the policy language that made the failure possible.

Two of the Forest Concessions targeted in the World Bank’s failed attempt to create an environment of both law and extraction at capital’s frontier are intimately connected to the conservation landscape of this study. They were both issued in 1996, in the context of one of several donor-instigated forestry reform initiatives (see Cock Citation2016). The first concession, the 130,000-hectare Chinese Everbright CIG Wood Co. Ltd (, #14), is only passively implicated by opening the remote eastern regions of Prey Lang in Kratie to industrial extraction. They built roads, employed soldiers and villagers, and moved timber through the forested western edge of the Mekong for nearly 10 years. The second is the Cherndar Plywood Co. Ltd. (, #10), which operated in Preah Vihear in the Preh Preah Roka Forest.

This concession was officially recognized in 1996, but its director Mr. Lu Chu Chang reports being in Cambodia’s timber industry since 1991.Footnote4 Mr Lu was particularly violent, and residents report that their legally-protected resin trees were regularly under threat, and they feared for their own safety (O’Connel and Saroeun Citation2000).Footnote5 When the Forest Concession infrastructure crumbled along with World Bank activities in 2005, neither concession was canceled but both ceased concession operations that same year.

Everbright went home, and Cambodia’s Forest Administration (FA) designated the forest of the old Everbright concession along the Mekong ‘degraded’. Mr Lu did not go home but began a plywood company and became president of the Cambodia Timber Industry Association, designed by forest sector reforms to facilitate communication between industry and government.

4.2. PLCN

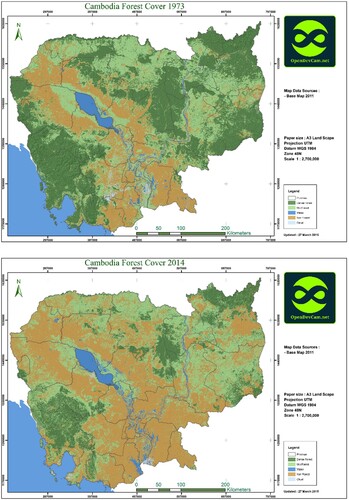

The radical extraction of forest concessions sparked widespread popular protest and people demanded protection and compensation (McKinney Citation2003; Naren and Vrieze Citation2012; Khy Citation2015). The Prey Lang Community Network (PLCN) took shape during these years as donor dismay opened both space and funding for activist collectives. The Kuy Indigenous communities from Prey Lang’s four provinces had already been reacting against company incursions. Starting in the late 1990s with a few members, by the early 2000s, in response to forest concession logging they began coordinated forest patrols to confront illegal extraction from both companies and freelance loggers, these activities increased as ELC began to move into the forest (Brofeldt et al. Citation2018). PLCN gathered more members as the destruction continued and they became more effective as their numbers grew. The majority of Kuy families harvested resin, and their losses increased with the large clear-cutting for plantation agriculture through ELC. In addition to protesting ELC development in Prey Lang, PLCN started destroying timber and equipment upon capture and local authorities accused them of criminal activities, subjecting them to harassment and threats of arrest. It soon became clear that their activities were disrupting the work of local officials in the forestry sector (Bun Citation2011), who presided as de jure owners of the forest over one of the largest global deforestation events (). During the years of local activism, PLCN also received support from USAID through the East–West Management Institute (EWMI) (Parnell Citation2015), which ended when authorities objected to PLCN activities. The grassroots collective continues to advocate for forest protection and continues to receive external support from NGO, researchers, and other activists. Since 2014 they have collaborated with researchers at the University of Copenhagen to produce a high quality ‘Forest Monitoring Report’ each year, which publishes the data gathered by grassroots researchers, supplemented by satellite data.Footnote6 In 2016, the group was awarded the Equator Prize for their work protecting Cambodia’s forests, and continue to be recognized by the international community. This recognition by others is an important element in the legitimacy of PLCN, just as it is for the extractive Cambodian government. We describe below the powerful effects of USAIDs legitimizing choices and continue here to discuss the Prey Lang landscape.

4.3. Economic land concessions (ELC)

Deforestation under the forest concession system was extreme, but this was single-cut industrial logging rather than clearcutting, and the forests remained relatively intact. Not until the rollout of ELC were whole regions transformed from forest to industrial agriculture, foreclosing all other livelihood options. The 2001 land law provided the legal structure and RCG awarded the first ELC in Prey Lang in 2007 to the Tumring Rubber Co. (now the site of a REDD+ project, discussed below).Footnote7 This opened up dense forest and quickly transformed the region with multiple new concessions, first at the southwestern edge of the forest (2007–2011, red boxes) then into the northern regions (2012, blue boxes). ELC sparked another wave of anarchic land grabbing, destruction beyond concession boundaries, circumventing of legal codes, and massive deforestation (Milne Citation2015; Tucker Citation2015; Beban, So, and Un Citation2017). Reforms were instigated in 2005 (RGC Citation2005) and new protected area laws were ratified in 2008 (RGC Citation2008).

Programs for reforms and transparency, like those for forest concessions, were ineffective and ELC were discontinued in 2012, by which time approximately 14% of the country was allocated to domestic and foreign corporations for development (Forest Trends Citation2015). Approximately 80% of this land (113 ELC) is inside protected areas and forest reserves (Theilade and Kok Citation2015; RGC Citation2008).

In Prey Lang, ELC transformed large areas of forest into plantation in a very short time. In 2012, ten concessions arrived in the northern regions totaling nearly one-hundred thousand hectares, including one 43,007 ha ‘forest restoration’ project. These 2012 concessions are all implicated in the syndicated logging discussed below. After the 2012 referendum, no new ELC have been awarded, but the residue of violence remains. Because ‘development’ in Cambodia involves transforming land that is already in use, the process regularly involves police and military actors to facilitate the ‘transfer of ownership’ (Sperfeldt, Tek, and Tai Citation2012; Beban, So, and Un Citation2017). The biggest issue currently is the continued logging with the obvious facilitation of government officials.

4.4. Landscape conservation

Forests inside Cambodia’s protected areas are disappearing as fast as forests nationwide, rendering them clearly ‘un-protected areas’ (Zsombor and Pheap Citation2015). This is the context in which USAID entered the conservation scene in earnest with a 20 million USD project titled Supporting Forests and Biodiversity (SFB), implemented by Winrock International from 2012 to 2018. The project managed two landscapes, the Keo Seima Protected Area and Prey Lang, and partnered with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and Conservation International (CI). Both of which are under scrutiny for facilitating illegal logging, human rights abuses, and greenwashing beyond Cambodia (Ecologist Citation2011; Milne Citation2019; RF Citation2020). Among SFB goals were ‘increased forest governance capacity’ of government and local people, selling carbon credits, and establishing Prey Lang as a protected area (Work Citation2018, 15). USAID made earlier tentative steps into Prey Lang and conservation-related projects with environmental and country studies (USAID Citation2001, 2013), and starting in 2009, funded civil society-strengthening projects executed by EWMI.

The EWMI initiative was well-regarded by PLCN members, but not by the FA and MAFF. According to the director of the project at Winrock International, the PLCN was seen as ‘activists against the government’ and SFB ‘just stopped’ the direct collaboration with PLCN.Footnote8 Just months later, SFB funded a new civilian patrol group agreeable to the FA. During this time MAFF resisted protected area negotiations, preferring a production forest strategy (see Work and Thuon Citation2017 for details of the patrol group and the PA negotiation). Eventually, SFB pushed through the protected area agenda with the MoE. However, the new roads connecting Kuy villages inside the protected area along with the ongoing migrant incursions and increased small holder plantations beginning in 2016 suggest that a different vision was already underway for the region. Perhaps in line with the ADB development corridors that cut across the northern regions of Prey Lang.Footnote9 PLCN’s 9th Monitoring Report shows 2016 had the highest deforestation rate recorded in Prey Lang since 2001 (PLCN Citation2021), numbers that are absent from the SFB final report (Work Citation2018).

The Greening Prey Lang (GPL) project began without the community consultation promised at the close of the SFB project (Maza and Sengkong Citation2016; for details of project issues see, Work and Thuon Citation2017; Work et al. Citation2019). When the 20 million USD project was awarded to Tetra Tech in 2018, USAID declared that they did not need to consult the community because they had all the information they needed from the last project.Footnote10 The GPL project lacked clear documents at the outset, but it was conceived in largely similar ways as SFB. The collaborations with big conservation organizations CI and WCS were re-established, with governance, livelihoods, and forest management and financing (REDD+) as key priority issues (USAID and TT Citation2018). In addition, they developed the ‘conservation corridor’ concept through the Prey Lang Extended Landscape (). By 2020, the number of ‘un-protected area’ hectares in Cambodia expanded to 41% of the country’s surface area, way above the 20% recommended by the IUCN and unrivaled at the international level. One of these corridors included the yet undeveloped northern areas of the Think Biotech project. That corridor is now treeless, and the Think Biotech project at the center of our case study began as an intergovernmental partnership toward climate change mitigation.

4.5. Inter-governmental partnerships and REDD+ Korea-Cambodia

Two projects emerged out of a 2008 MoU, ‘concerning the cooperation on investment in forest plantation and climate change’, between the Cambodian Forest Administration and the Korean Forest Service. The first product of this agreement was to establish the Think Biotech forest restoration project on 34,007 hectares of healthy forest that was re-classified by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) as ‘degraded forest’ due to previous logging by Forest Concessions ( and ). The area’s ancient trees fell to concessionaires, but vital forest remained in use to hunt, fish, and tap resin trees as reported by local residents and witnessed by all three authors between 2003 and 2020 (see also, Thuon Citation2002; Turreira-García et al. Citation2017). Local activism against Think Biotech was strong (Titthara Citation2013b; Citation2013a), and the blatant ways that climate change discourses were deployed to obscure industrial plantation development in healthy forest areas drew waves of criticism (Turton Citation2017). Further investigations revealed Think Biotech logging within the protected area and company trucks hauling lumber to Tbong Khmum province along new roads crossing the forest (Phak and Turton Citation2017). Research revealed MoE ranger knowledge of the transport, and complicity in logging, but links to syndicated logging were not pursued. Company practice drew considerable complaints from local observers, which when added to the disconnect between framing policies and project implementation — including private memos between the Korean and Cambodian agencies regarding Think Biotech, a newly created subsidiary of a massive chemical and weapons manufacturing company, that would ‘restore’ the healthy forest—raise significant questions about the integrity of both sets of government actors as well as the sustainability of climate change mitigation projects (see, Work Citation2017; Scheidel and Work Citation2018).

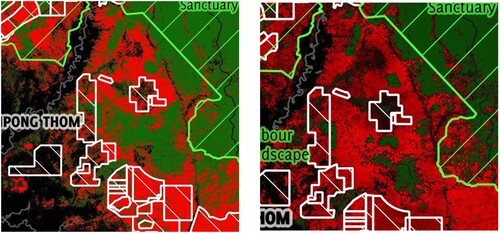

In addition to the forest ‘restoration’ project, the Korea-Cambodia Tumring REDD+ project was initiated in 2015. In terms of impacts on local lives, the project was benign. It landed in Tumring, a section of the forest where market-independent livelihoods were already heavily degraded by the ELCs. The Tumring REDD+ has a beautiful online presence describing the project situated in 67,791 hectares of forest in Kampong Thom ().Footnote11 In this small area the project apparently avoided losing 645,410 tons of carbon from January 2015 to December 2019 and plans to avoid over 11,559,975 tons of carbon over the 30-year life of the project. These numbers are difficult to verify, and the director of the project would not agree to an interview. But satellite imagery shows extensive deforestation that the project claims to have avoided (). This project also came under critique from a Korean NGO in connection with other claims against the Korean Forest Service’s mismanagement in KoreaFootnote12 (see also FAO and FILAC 2021, on effective community management, and Asiyanbi and Massarella Citation2020, on inflated carbon credits). Korea will not sell these credits on the voluntary (patron/client) market but will use contained carbon to offset their own emissions.

Figure 6. Forest loss in Tumring REDD+ project site. 2016 deforestation map on left; 2019 map on right. (Maps are continually updated and can be downloaded from this site: https://www.licadho-cambodia.org/land_concessions/).

4.6. Japan: JCM and Mitsui REDD+

Japan’s Joint Credit Mechanisms are designed to ‘facilitate diffusion’ of ‘low carbon technologies’ and the ‘implementation of mitigation actions’ through bilateral agreements in ‘developing countries’ and to ‘evaluate contributions from Japan to GHG emission reductions or removals’ to ‘achieve Japan’s emission reduction target’.Footnote13 The 2018 Mitsui REDD+ project brokered by CI through Japan’s Joint Credit Mechanisms also falls under the GPL mandate (TT Citation2019). These kinds of strategies are an excellent example of 'green grabbing' discussed by Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones (Citation2012), and are a new element of climate politics being adopted by industrialized countries explicitly to meet their National Declaration Commitments of the Paris Agreement.Footnote14 Even by industry insiders, they are widely acknowledged to be offset ‘games’ and forms of ‘greenwashing’, more aspirational and cosmetic than effective.Footnote15

The Mitsui REDD+ project, which comprises 120,000 hectares of forest in Steung Treng () is still in the pilot phase. CI receives about one-million USD from the project to provide technical support and in-country coordination, but has yet to claim any carbon credits.Footnote16 Mitsui pays for the calculations and on-the-ground activities with half of their budget and retains the other half for marketing the project in Japan to find the carbon buyers.Footnote17 The Wildlife Conservation Society REDD+ expert claims this project model is in line with protocols reached in the Paris Agreements,Footnote18 and the CI website declares that it ‘helped to quantify forest carbon stocks, provided training to local and provincial governments to monitor the tropical forest, and provided support for improving livelihoods and law enforcement training.’Footnote19

Figure 7. REDD+ projects in Prey Lang. Orange dots 2019/2020 deforestation (Keeton-Olsen Citation2020).

The CI director was unclear about whether any funds will go to forest communities, but stated, ‘surely the money from carbon credits will go to the project to do all the work on the ground.’Footnote20 REDD+ projects typically provide little benefit for people living within the project area, and consistently do not reduce forest loss (see, Ken et al. Citation2020, for a study of the two Cambodian projects that have sold carbon). The Tumring REDD+ project promised to provide monthly support for community forest groups to do patrols, but payments are unreliable.Footnote21 In another REDD+ site (Keo Sima), the monetary benefits of approximately ten-thousand USD per year are channeled through a ‘commune investment program’, because villagers are apparently ‘not good at managing money’.Footnote22 Villagers are not unhappy with this, but they are very concerned about continued deforestation despite the REDD+ project and say their deforestation reports go unheeded (Keeton-Olsen and Dara Citation2021). And yet consistently, Cambodia’s ‘earnings’ from REDD+ projects go into project management and bureaucratic infrastructure that seems to be doing little to actually stop deforestation.Footnote23

REDD+ as an initiative for global forest governance, is an extension of and often embedded within the conservation landscape. As such, it reinforces government power over forests with optimistic policies for forest conservation, while doing little to benefit people living in forest landscapes or to limit forest degradation and deforestation (Milne Citation2021, 1; Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2012). REDD+ is part of the context in which our case study plays out with strong implications for the future of forest-based carbon offset projects. We proceed now to lay out the details of the case study that prompts this re-evaluation of shadow state activities in Cambodia’s development

5. The logging syndicate

For reasons that cannot be confirmed, but that could have to do with the official community forests inside the concession boundary (ratified by SFB), with the unofficial resin forests mapped by community members, with the company’s inability to have their Environmental Impact Assessment approved due to excessive impacts on local livelihoods, and the ongoing complaints and protests from villagers (see, Work Citation2017), the Koreans pulled out of Think Biotech at some point in 2018. Local resin tappers and villagers living close to the concession reported a hopeful silence at the site until late November 2018. This is when Mr. Lu acquired the company in partnership with a well-connected Cambodian businessman. Together they run Think Biotech and Angkor Plywood, both publicly implicated in the organized crime we report here (see also, Global Initiative Citation2021).

Logging under the cover of ELCs is a well-established practice in Cambodia, lamented by concessionaires, activists, and academics alike (Milne Citation2015; GW Citation2015). In our case, there are four concessions operating in the northern sectors of Prey Lang along both the east and western boundaries of the protected area (). Two of these (PNT and ThyNga) were implicated by PLCN and other activists in timber laundering under the cover of undeveloped Vietnamese-operated rubber concessions in Preah Vihear (Titthara Citation2016). One is the fully developed, now defunct Chinese-operated HengFu sugar concession in Preah Vihear (5 contiguous concessions operating as a single company, see Mackenzie et al. Citation2022), which housed a sawmill within its boundaries (operating legally at first, and illegally once the plantation was cleared; it stopped operations when HengFu officially stopped operations), and the fourth is the Think Biotech ‘forest restoration’ concession.

Evidence gathered over the course of multiple field missions from 2018 to 2021 by local researchers and forest activists who for their own safety must remain anonymous, provide detailed evidence of syndicated timber extraction based inside the above mentioned ELCs. These data show clear evidence of Cambodian-owned and operated ELC-based sawmills collecting timber from the protected forests of Prey Preah Roka and Prey Lang and direct connections to the Angkor Plywood company, which played a major role in transporting the timber across the Vietnamese border. It also establishes stronger links between activities within the Think Biotech forest-restoration project and Angkor Plywood. The report published by Global Initiative (Citation2021) provides geo-tagged photos and videos from inside protected areas and ELC boundaries, vehicle trackers, as well as bills of lading gathered from the border check points going into Vietnam under the Angkor Plywood company. The details of this report are substantiated by data and information gathered by the research activities of the first two authors also between 2018 and 2021 (both activists and authors have data that extends further into the past).

In November 2018, local resin tappers reported threats to PLCN in Steung Treng. A company connected to Think Biotech told them to sell their resin trees or lose them under the company’s mandate. PLCN and resin tappers collaborated to document the threats and to enlist the assistance of local authorities when over one thousand resin trees were aggressively harvested in early 2019 (SEATV Citation2019). In July of 2019 the second author and her team collected satellite data showing the clear development of roads leading from the new sawmill inside the Think Biotech concession directly into the protected area. Data gathered by local researchers during this period (Global Initiative Citation2021) show industrial-scale extraction from within the protected area that involved a sawmill inside the soon-to-be defunct HengFu sugar plantation in Preah Vihear, two new sawmills inside the undeveloped rubber concessions of ThyNga and PNT in Preah Vihear, as well as the new sawmill inside the Think Biotech concession.

A field trip to the Think Biotech sawmill in January 2020, conducted by USAID and Tetra Tech representatives, accompanied by the first author and PLCN representative, met company executives and representatives from both MAFF and MoE. The visiting party was detoured and brought to only one of the two sites requested. The road did not exactly run straight from the plantation into the protected area at this site, but there was clearly a road into Prey Lang. The company and government representatives denied any impropriety and USAID representatives negotiated in good faith. This meeting resulted in decreased activities until February 2020 when MoE denied PLCN access to the forest for their annual tree blessing ceremony (Sun Citation2020; Keeton-Olsen Citation2020).

In April 2020, the second author’s team, using satellite data from the Global Land Analysis & Discovery (GLAD) lab at the University of Maryland (Hansen et al. Citation2013), and Forest Canopy Disturbance data from the Joint Research Center (JRC) of the European Commission, published data proving extreme increases in logging activity within the Prey Lang Forest immediately after the exclusion of PLCN from the forest (Theilade Citation2020). These data were corroborated with field data gathered by local researchers in April 2020, during Covid-19 lockdown. Despite country-wide travel restrictions, logging activities continued in which hundreds of local loggers were paid to cut the remaining commercial timber within the protected area, targeting especially community resin trees, which were transported into the Think Biotech concession area (Lipes and Yun Citation2020; Theilade Citation2020). Regular field activities of local activists were met with arrest and detention without charge on two different occasions (Crothers Citation2020), with no legal action taken against any of the companies or individuals involved in the extraction, who had already been named in previous reports on Cambodia’s logging prowess (GW Citation1999, Citation2007; Forest Trends Citation2015; Cook Citation2018). Logging inside the protected areas continues to be documented by local researchers, right up to the time of this writing.

6. The conservation canopy

USAID granted the 20-million USD Greening Prey Lang project to the US-based consulting and engineering firm Tetra Tech (Tetra Tech Citation2019) at almost the same moment that Mr. Lu acquired Think Biotech from the Koreans in late 2018. The first and second authors were in contact with representatives of the USAID project from the beginning, and we spoke candidly about previous issues with USAID projects and informed them about the first author’s research project explicitly looking at the roll-out of this conservation project. When resin tappers were threatened in 2018 and excessive logging inside the protected area began in 2019, this information was shared. The data were ignored by the MoE and effective action was thwarted by USAID policies regarding the ‘sovereign’ rights of national actors. When logging reached a fevered pitch through 2020, the satellite and ground data gathered by the authors and local researchers were shared with the GPL project director in real time, and there were some overtures by the GPL project to pressure ministry actors to stop the extraction. The project continued in the meantime to execute ministry objectives despite the human rights violations they engendered, and it was not until July 2021 that USAID formally withdrew support for the MoE. Below is a description of the events (: timeline of events).

Table 1. Timeline presenting main events and actions of main stakeholders; (i) Ministry of Environment (MoE), (ii) USAID and implementing agency Tetra Tech, (iii) Prey Lang Community Network (PLCN) and other environmental defenders.

In February 2020, the MoE blocked the annual tree blessing ceremony in the old-growth forest. The monks, PLCN, civil society, and community members were all turned away and continue to be excluded from the forest at the time of this writing. Satellite imagery provided by the Joint Research Centre of the EU Commission and Global Forest Watch reveal rapid forest loss in that ‘core’ area of the forest over the weekend (PLCN Citation2021; Keeton-Olsen Citation2020). After the announcement of this data, the Spokesperson of the MoE publicly threatened to arrest PLCN members for using satellite data to observe deforestation, and referred to the Ministry’s collaboration with USAID GPL as the only legal forest protection (Savi Citation2020b). According to MoE spokesman, PLCN is a ‘politically motivated’ activist group operating outside of the law (Savi Citation2020a). The law referred to is the controversial Law on Associations and Non-Governmental Organizations (LANGO), that is widely criticized as being a tool to silence rights-based organizations (RGC Citation2015; UNHCR Citation2015).Footnote24

After that blatant exclusion and threats, the Ministry attempted to create its own patrol network through their Community Protected Area (CPA) program, which explicitly limits community access to forest resources and forest management to small, designated forest areas.Footnote25 Both USAID-sponsored conservation projects (SFB and GPL) implemented and administered this plan in collaboration with partners WCS and CI. The MoE agenda was larger and involved hiring new rangers and recruiting civilian patrollers from all four provinces in Prey Lang through the CPA committees. During the recruitment process, evidence emerged that the Provincial Department of the Environment directors purged PLCN names from the recruitment lists,Footnote26 and one CPA member claimed that ‘the only people approved for government patrols are illiterate and stupid’.Footnote27 The CPA and community patrol groups established by Greening Prey Lang that deliberately excluded PLCN members, provided a cover under which MoE could, and regularly did, claim effective forest governance and community participation against mounting critiques as news of Think Biotech activities circulated (Khorn Citation2020; Long Citation2020).

While PLCN is banned from patrol activities in clear violation of their commitment to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (Amnesty International Citation2020), the MoE publicizes their forest governance activities. They count over 900 criminal cases prosecuted in 2020 (Sen Citation2020), yet do not report the resin trees logged, which number in the tens of thousands (RFA Citation2020, Citation2019). This is despite the high economic value of resin for local communities. Promoting market linkages for resin were part of SFB and also Greening Prey Lang’s early project documents (Charles Citation2016; USAID and TT Citation2018), but have been silently replaced with promoting market linkages for intensified agriculture approaches. Nonetheless, at the height of resin tree exploitation and public outcry, while local activists faced attacks, arbitrary detention, physical assaults, and the death of one PLCN member in their interactions with both state authorities and corporate actors (Tran and Baliga Citation2021), GPL published a conservation success story on resin tapping (GPL Citation2021).

Despite sharing evidence and concerns regarding the obvious logging inside the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary with MoE, the GPL project remained publicly silent about the violations in their program area (Sun Citation2020). The impact on local livelihoods of such a rapid and dramatic loss of resin trees is substantial. ELC confrontations in 2011 reported 90% of families relying on resin for primary income. This is a generational loss as well because use of the trees is passed down through families. A full accounting of the number of trees and the number of families affected is emerging as Covid travel restrictions are lifted. There are families, however, who have benefited from the money gained through increased logging activities and collaborations with the company. While finite and short term, these gains must also be counted.

USAID finally broke silence on 8 March 2021 to say that they were ‘deeply concerned’ about the deforestation, which ‘is linked to several factors, including weak law enforcement and opaque governance systems’. The press release goes on to claim that they assist ‘local communities, including … PLCN’ (USMC Citation2021a). The hubris and impunity of this statement are remarkable in light of events in Prey Lang for almost two years. PLCN was appalled by the blatant falsehood (Flynn Citation2021), but more importantly, what we describe in this case study is not ‘weak law enforcement’, it is powerful, organized, and deliberate law breaking. It took another three months of pressure before USAID withdrew funding from the MoE through their GPL project in July 2021 (USMC Citation2021b), but funding for CI and WSC remains intact, and the project continues to cultivate business investments for both REDD+ and for enhancing market-based community livelihoods.

According to the new Country Development Cooperation Strategy released by USAID (Citation2021), the mission will prioritize ‘inclusive and sustainable economic growth’ as well as human rights, with ‘strengthened public oversight of government institutions’ through policies that focus on communities and private sector to ‘promote free market competition, support technology and innovation, and incentivize private sector growth and market-based solutions … [and] improve governance, rule of law, and sustainable development’ (USAID Citation2021, 3, 6, 5). How exactly the private sector is going to begin respecting the rights of poor humans and silent non-humans is unclear, equally unclear is what public oversight of an increasingly authoritarian political environment will look like, and further how USAID will protect rights in light of their recent failures in the context of increasing economic growth and the strong potential for continued private-sector-government anarchy that we describe above.

7. Implications and invocations

Many of the issues we describe above have been described before. The importance of bringing them together here are twofold. First, to highlight the dynamic interactions between development projects and actors over time, especially the textured ways that development politics morph into climate change politics, and the ways that actors in one can be implicated in another. The Korean Forest Service is a player in what became the Think Biotech reforestation project, just as the World Bank played its role in creating the conditions for a shadow state and the market relations currently at play in Prey Lang. We point to the policies that make this possible, because of the persistence of ‘idealized’ landscapes upon which policy frameworks are created, which seem to be instrumental in legitimizing – even legalizing the kinds of violent extraction visible in places like Cambodia.

The second reason for drawing out this case study is that this collection of egregiously illegal, socially and ecologically damaging activities takes place in plain sight of an international donor bound by policies respecting sovereign rights to let it continue (USAID/Tetra Tech), and long-involved conservation corporations (WCS and CI) that have grown accustomed to the process (see also Milne Citation2019). It is true that China’s increasing role in driving development changes the donor landscape (Käkönen and Thuon Citation2019; Mackenzie et al. Citation2022), and that this changes Cambodia’s public adherence to Western donor requirements. We do not, however, interpret this shift in donor dependency as impactful in the complicity of the current case. The role of Western donors remains important in Cambodia, particularly in climate projects, and their leniency and continued support since the UNTAC interventions as outlined above have changed little over time. We also point to the importance of illegal timber from Cambodia in supplying EU markets through the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA), between the European Union and Vietnam, in which large-scale illegal timber traffic from Cambodia and Laos into Vietnam was exposed (EIA Citation2020). Nonetheless, large-scale exports of timber from Vietnam to the EU continue to occur (Nghia Citation2021). At this historical moment, Ferguson’s (Citation2006) observation that predatory states ‘not only destroy national economic spaces but construct global ones’, is of increasing importance (13).

Also important is the persistence of policies that assume benign states, regulated markets, and the high value of economic growth and wealth creation. Delabre et al. (Citation2020) discuss these as myths that persist in global sustainable forest governance. We show how many of these myths extend into the history of development projects and the inherent tension between extraction and sustainability that drives the tension between violence and justice. We suggest that understanding these myths as an inverse expression of the narrative of the shadow state can illuminate some of the shaded areas of the global development project through which the slide into climate instability continues unchanged. If the shadow state describes a set of dysfunctional practices that happen behind the bureaucratic structures of laws, the myths of governance justify a particular bureaucratic configuration of policy and law that operate in front of the shadow state. The policies are anticipatory, operating in an imagined place of possibility as if the transformation of self-organized ecological economies can be converted into state-owned market-oriented landscapes without violent exclusions and ecological degradation. The grey zone lies in the open space where the primitive accumulation that creates sovereignty is shielded by its impossibility within the laws that legitimize it.

In a coda to an edited volume on the grey subjects of post-communist Eastern Europe, Nils Bubandt (Citation2015) suggests that the proliferation of grey narratives emerges in part from the ‘subversion of an imagined order’ (188). This is an important point to think with, in the context of ecological destruction, continued economic growth, and the myths and histories of forest governance that we highlight here. The processes of extreme extraction and the violent subversion of the law that we describe are not grey, but the condition in which they emerge is obscured, shaded by the bureaucratic canopy of international development and the conservation industry. In the face of well-documented forest crime accusations, MoE pointed directly to the Greening Prey Lang-supported activities to legitimize their good work (Long Citation2020; Voun Citation2020), and USAID attempted to hold the party line by declaring the problem to be ‘weak law enforcement’ rather than organized crime (USMC Citation2021a). This is now an old story in Cambodia, which has transformed from a land of rich traditions, flora, and fauna into a vibrant market economy and carbon supply chain for the developed world. Perpetuating the myth that illegal acts of primitive accumulation can be contained by rational law is now bordering on the criminal (Greene Citation2019), and it may be time to acknowledge this if climate justice is to be more than a farce.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like most of all to thank the people living in and around Prey Lang who have shared their insights and experiences with us and helped us see what development projects look like from the ground. We are also indebted to local activists, who cannot be named here, but whose research is vital to our collective knowledge, and we thank colleagues who shared their experiences with us through interviews and collaborations and whose expertise sharpened the piece, especially Marcus Hardtke, Sarah Milne, Jeremy Ironside, and James Cock. And a special thanks goes to the generous and excellent blind reviewer for JPS, whose critique, advice, and keen eye helped us bring out the story we wanted to tell with this piece.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Courtney Work

Courtney Work is associate professor of ethnology at National Chengchi University in Taipei. Her research focuses on regions transforming from forest to developed, settled landscapes with interests in the interactions between humans and the non-human world. Current research is focused on engaged methods to enhance dialogue in the contact zones where development meets the land that sustains it. Disciplines include, the Anthropologies of Religion, Development, and the Environment; the History of Southeast Asian political formations; and Contemporary Political Economy and Climate Change.

Ida Theilade

Ida Theilade is a professor at University of Copenhagen on participatory management and conservation of tropical forests. Current research centres on ethnobotany and the role local and indigenous knowledge can play in natural resource governance and climate action. This includes the use of information and communication technology in forest governance and climate change mitigation and adaptation. Capacity building and advisory services on forest governance in East Africa and SE Asia and dissemination of research results to a wider audience is an integral part of her research.

Try Thuon

Try Thuon holds a PhD in social sciences from the International Program of Doctor of Philosophy of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University. He has led two research projects: ‘Urban Development and socio-economic change of Sihanoukville urban development in time of covid-19 pandemic' and a join transboundary research project called, ‘Bringing more than food to the table: precipitating meaningful change in gender and social equity-focused participation in transboundary Mekong Delta wetlands management’. His research interests include urban vulnerability and resilience in practice, urbanism from the bottom, water security, gender inequality and ethnic relations and the role of social sciences in social engagement for co-learning process and planning practice.

Notes

1 To understand how Cambodia came to be in a situation of civil war in 1980, entails a discussion of Cambodia’s post-colonial history, the American war against communism, Vietnamese ouster of Khmer Rouge, ASEAN sanctions against the Vietnamese-sponsored State of Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge holding Cambodia’s seat at the United Nations, and the United Nations Transitional Authority (UNTAC) that is beyond the scope of this paper (please see, Vickery Citation1990; Kiernan Citation2004; Gottesman Citation2004; Chandler Citation2008; Ear Citation2007; Thun Citation2010).

2 Map 2 Source: Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Atlas of the Environment (2nd Edition). Adapted from the GMS Information portal, http://portal.gms-eoc.org/uploads/map/archives/map/CAM-Overview1hires2.jpg/ with permission from GMS Environment Operations Centre, Bangkok, Thailand.

3 In a 2018 study in Steung Treng, village heads from five of the eight Kuy villages visited (those connected by new roads) reported 80–100 new families each since 2016.

4 Interview, Lu Chu Chang, Phnom Penh, 26 July 2019.

5 The 2002 Law on Forestry states it is illegal to harvest resin trees without villager permission.

6 All issues of the ‘Forest Monitoring Report’ can be found here: https://preylang.net/

7 2001 land law was supported by ADB TA 3577 and LMAP TA GTZ

8 Interview, Phnom Penh, July 9, 2015.

9 For a 2014 map, see: https://wrm.org.uy/articles-from-the-wrm-bulletin/section1/the-asian-development-banks-infrastructure-led-growth-in-india-and-the-mekong-region-1/

10 interview, USAID, Phnom Penh, 24 August 2018.

11 See the Tumring REDD+ website at: http://www.tumringredd.org/

12 The Friends of the Earth website posted the press release. Accessed September 10, 2021. https://foeasiapacific.org/2021/08/30/large-scale-deforestation-at-korea-forest-services-redd-site-in-cambodia/

13 These quotes were taken directly from the JCM website, accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.carbon-markets.go.jp/eng/jcm/

14 The JCM and its self-declaration of emission reductions is beyond the scope of this paper but deserves critical reflection. One JCM project in Cambodia involves a ‘high-efficiency centrifugal chiller’ for the third Aeon mall that is under construction in Phnom Penh. Accessed March 5, 2021. https://www.jcm.go.jp/kh-jp/information/305

15 Interview UNREDD Cambodia director, August 21, 2019.

16 Interview MoE REDD+ representative, Jan 10, 2020.

17 Interview CI country director, Nov 16, 2020.

18 Interview, Oct 21, 2020.

19 Quote taken from Conservation International Website, accessed June 5, 2022. https://www.conservation.org/projects/prey-lang-wildlife-sanctuary

20 Interview, director CI, Nov. 16, 2020.

21 Interview, community forest groups, Feb. 27, 2016.

22 Interview MoE REDD+ representative, Jan 10, 2020.

23 Interview UN-REDD Rep, Oct 19, 2020

24 As a community-based group of volunteers with no formal structure, it is impossible for PLCN to register as an NGO ‘according to the law’.

25 The MoE Protected Area governance strategy, funded and underwritten by the World Bank (Citation2008), conceives of a protected area with regions zoned for particular kinds of uses and surrounded by a ‘buffer zone’ of community-managed areas. Within this strategy, local residents are excluded from the ‘core’ and ‘conservation’ zones, which are reserved for ‘Nature Conservation and Protection Administration officials and researchers’, and their activities are constrained within the other zones (Article 11). All traditional practices, shifting cultivation, hunting, grazing livestock, gathering plants, are prohibited within particular zones (Article 41) (RGC Citation2008). Despite being in direct contradiction of well-established conservation science, which confirms that large in-tact, as opposed to broken and segregated, conservation landscapes promote high biodiversity and ecosystem health (MacArthur and Wilson Citation2015 [1967]; Costanzi and Steifetten Citation2019) this legal framework ignores growing evidence that human activities in swidden landscapes promote high biodiversity and carbon content (Scheidel Citation2016; Dressler, Smith, and Montefrio Citation2018).

26 Interview, Tetra Tech representative, April 14, 2020

27 Interview, Steung Treng community member, Jan 27, 2021

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2005. The State of Exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Amnesty International. 2020. Cambodia: Harrassment of Forest Defenders Undermines Struggle Against Climate Change: Public Statement (Issue March, pp. 1–2). Amnesty International.

- Asiyanbi, Adeniyi P., and Jens Friis Lund. 2020. “Policy Persistence: REDD+ between Stabilization and Contestation.” Journal of Political Ecology forthcoming: 378–400.

- Asiyanbi, Adeniyi P., and Kate Massarella. 2020. “Transformation Is What You Expect, Models Are What You Get: REDD+ and Models in Conservation and Development.” Journal of Political Ecology 27: 378–495.

- Barney, Keith. 2009. “Laos and the Making of a ‘Relational’ Resource Frontier.” Geographical Journal 175 (2): 146–159. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2009.00323.x.

- Beban, Alice, Sokbunthoeun So, and Kheang Un. 2017. “From Force to Legitimation: Rethinking Land Grabs in Cambodia.” Development and Change 48 (3): 590–612. doi:10.1111/dech.12301.

- Bernstein, Henry. 1990. “Agricultural ‘Modernisation’ and the Era of Structural Adjustment:Observations on Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Peasant Studies 18 (1): 3–35.

- Biddulph, Robin. 2010. Geographies of Evasion: The Development Industry and Property Rights Interventions in Early 21st Century Cambodia. Göteborg: Geson.

- Biddulph, Robin. 2014. “Can Elite Corruption Be a Legitimate Machiavellian Tool in an Unruly World? The Case of Post-Conflict Cambodia.” Third World Quarterly 35 (5): 872–887. doi:10.1080/01436597.2014.921435.

- Billon, Philippe Le, and Simon Springer. 2007. “Between War and Peace: Violence and Accommodation in the Cambodian Logging Sector.” In Extreme Conflict and Tropical Forests, edited by Wilde Jong, Deanna Donovan, and Ken-Ichi Abe. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Borras, Saturnino M. 2019. “Agrarian Social Movements: The Absurdly Difficult but Not Impossible Agenda of Defeating Right-Wing Populism and Exploring a Socialist Future.” Journal of Agrarian Change 20 (1): 3–36. doi:10.1111/joac.12311.

- Borras, Saturnino M., Jennifer C. Franco, and Zau Nam. 2020. “Climate Change and Land: Insights from Myanmar.” World Development 129: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104864.

- Bovensiepen, Judith. 2020. “On the Banality of Wilful Blindness: Ignorance and Affect in Extractive Encounters.” Critique of Anthropology 40 (4): 490–507. doi:10.1177/0308275X20959426.

- Brofeldt, Søren, Dimitrios Argyriou, Nerea Turreira-García, Henrik Meilby, Finn Danielsen, and Ida Theilade. 2018. “Community-Based Monitoring of Tropical Forest Crimes and Forest Resources Using Information and Communication Technology – Experiences from Prey Lang, Cambodia.” Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 3 (2): 1–14. doi:10.5334/cstp.129.

- Bubandt, Nils. 2015. “Coda: Reflections on Grey Theory and Grey Zones.” In Ethnographies of Grey Zones in Eastern Europe: Relations, Borders and Invisibilities, edited by Ida Harboe Knudsen, and Martin Demant Frederiksen, 187–197. London: Anthem Press.

- Bun, Narin. 2011. “Police Warn NGO over Workshops”. The Cambodia Daily. September 6. Phnom Penh. https://english.cambodiadaily.com/news/police-warn-ngos-over-workshops-102702/.

- Chandler, David P. 2008. A History of Cambodia. Chiang Mai: Westview Press.

- Charles, Safiya. 2016. “Resin Brings Income for Rural People.” Khmer Times, September9, 2016. http://www.khmertimeskh.com/news/29560/resin-brings-income-for-rural-people/.

- Cock, Andrew. 2016. Governing Cambodia’s Forests: The International Politics of Policy Reform. Singapore: NIAS Press.

- Cook, Jesselyn. 2018. “Inside The Criminal Network Ravaging Cambodia’s Forests—And The Community Fighting To Save Them.” Huffington Post 2018. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/cambodia-forest-devastation_n_5a3d86b0e4b06d1621b45772

- Costanzi, Jean Marc, and Øyvind Steifetten. 2019. “Island Biogeography Theory Explains the Genetic Diversity of a Fragmented Rock Ptarmigan (Lagopus Muta) Population.” Ecology and Evolution 9 (7): 3837–3849. doi:10.1002/ece3.5007.

- Creak, S., and K. Barney. 2018. “Conceptualising Party-State Governance and Rule in Laos.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48 (5): 693–716. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1494849

- Crothers, Lauren. 2020. “Goldman Prize-Winning Cambodian Activist Arrested, Released in Cambodia.” Mongabay, March24, 2020. https://news.mongabay.com/2020/03/goldman-prize-winning-cambodian-activist-arrested-released-in-cambodia/.

- Delabre, Izabela, MariaBrockhaus EmilyBoyd, TorstenKrause WimCarton, Peter Newell, Grace Y. Wong, and Fariborz Zelli. 2020. “Unearthing the Myths of Global Sustainable Forest Governance.” Global Sustainability 3 (e16): 1–10. doi:10.1017/sus.2020.11.

- Derrida, Jacques. 2002. “Force of Law: The ‘Mystical Foundation of Authority’.” In Acts of Religion, edited by G. Anidjar, 228–298. New York: Routledge.

- Dressler, Wolfram H., Will Smith, and Marvin J.F. Montefrio. 2018. “Ungovernable? The Vital Natures of Swidden Assemblages in an Upland Frontier.” Journal of Rural Studies 61 (July): 343–354. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.12.007.

- Dyrmose, Anne Mette Hüls, Nerea Turreira-García, Ida Theilade, and Henrik Meilby. 2017. “Economic Importance of Oleoresin (Dipterocarpus Alatus) to Forest-Adjacent Households in Cambodia.” Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society 62 (1): 67–84.

- Ear, Sophal. 2007. “The Political Economy of Aid and Governance in Cambodia.” Asian Journal of Political Science 15 (1): 68–96. doi:10.1080/02185370701315624.

- Ecologist. 2011. “Conservation International Caught in Greenwashing Scandal.” The Ecologist, 2011. https://theecologist.org/2011/may/11/conservation-international-caught-greenwashing-scandal.

- EIA, Environmental Investigation Agency. 2020. Union Voluntary Partnership Agreement: A Work in Progress. London: Environmental Investigation Agency.

- Eilenberg, Michael. 2014. “Frontier Constellations: Agrarian Expansion and Sovereignty on the Indonesian-Malaysian Border.” Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (2): 157–182. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.885433.

- Fairhead, James, Melissa Leach, and Ian Scoones. 2012. “Green Grabbing: A New Appropriation of Nature?” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (2): 237–261. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.671770.

- FAO and FILAC. 2021. Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples: An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean. Santiago: FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2953