ABSTRACT

Regimes of agricultural modernization and climate change adaptation have converged in Rwanda under the banner of ‘climate smart agriculture’. Findings from a study with four agrarian communities show how external agendas of climate smartness can undermine locally rooted strategies for navigating social and environmental uncertainties. Through a focus on two crops (maize and sweet potato), this paper illustrates how climate resilience can be viewed as an uneven and incomplete process situated in peasants’ struggles for viability, autonomy, and wellbeing. I suggest that attention to everyday adaptations can help researchers and practitioners think beyond the technical adjustments that currently dominate institutionalized responses to climate change.

The adaptation imperative

In May 2016, as Rwanda faced its ‘worst drought in 60 years’ (Ntirenganya Citation2016), the World Economic Forum on Africa held its yearly meetings in Kigali. During a ‘Tackling Climate Change’ event, panelists listed alarming figures (increased temperatures, decreased rainfall, millions more people food insecure) before turning to the investment priorities that could avert disaster: climate information services, crop insurance, high-yielding seeds, stronger markets, and water infrastructure. A press release for the WEF Forum succinctly captures this framing of climate change adaptation:

Small-scale producers do not have the resources or ability to mitigate or protect themselves from the effects of climate change. Adaptation strategies need to be implemented. The effects of global warming can be managed by optimizing inputs – i.e. fertilizer application according to soil analysis and good-quality seeds with high germination potential. There needs to be a shift from traditionally grown staple crops … to cash crops – niche products with higher yields and margin. (WEF Citation2016)

This paper examines efforts to integrate climate change anxieties into agricultural development agendas and the implications for agrarian livelihoods. I consider the consequences of framing climate change adaptation as commensurate with technology-led agricultural intensification – what Marcus Taylor has termed the ‘adaptation-modernization nexus’ (Citation2014, 99). My analysis centers on four Rwandan communities’ experiences with overlapping programs of agricultural intensification and climate change adaptation, including Rwanda's Green Growth and Climate Resilience Strategy (GGCRS), Crop Intensification Program (CIP), Land Use Consolidation program, and associated agricultural improvement and climate adaptation efforts operated by various development agencies.Footnote2 These initiatives have found fertile meeting ground under the umbrella of ‘climate smart agriculture’ (CSA).

Developed in 2010,Footnote3 CSA has become a prominent framework to mainstream climate change concerns into development practice. Its proponents claim that CSA offers a ‘triple win’ of climate change adaptation, greenhouse gas mitigation, and increased agricultural productivity – all of which are viewed as crucial to meeting food security goals and economic development targets during an era of global climate change (FAO Citation2019; World Bank Citation2016). Skeptics have painted CSA as an effort to renew a paradigm of input-led agricultural intensification by attaching to it a narrative of climate emergency (Borras and Franco Citation2018; Clapp, Newell, and Brent Citation2018; Newell and Taylor Citation2018). They have argued that CSA neglects power relations, allocates responsibility for climate change mitigation to marginalized people, and can be readily co-opted by dominant policy discourses (Chandra, McNamara, and Dargusch Citation2018; Karlsson et al. Citation2018; Taylor Citation2018). Little research, however, has examined on-the-ground realities of CSA (though see Cavanagh et al. Citation2017; Taylor and Bhasme Citation2021).

This paper considers CSA's place in Rwanda's ‘Long Green Revolution’ (Patel Citation2013). My intention is to examine how CSA emerges in historical-geographical contexts, including how it shapes – and is shaped by – broader arcs of agrarian change. I focus on Rwanda's Land Use Consolidation (LUC) program (Bizoza Citation2021), which strongly incentivizes individual producers to consolidate land toward the cultivation of crops deemed by the state to be economically viable. LUC is at the center of efforts to increase crop productivity and enable agricultural-led economic growth through scaling up and commercializing the production of six priority crops: maize, wheat, rice, potato, bean, and cassava. LUC has become closely aligned with CSA mechanisms of crop insurance and marshland intensification. Findings from fieldwork in southwest Rwanda show how these conjoined efforts of agricultural modernization and climate change adaptation create an uneven landscape of resilience by privileging wealthier men and undermining the livelihoods and everyday forms of climate adaptation practiced by semi-subsistence producers, particularly women in farming households.

Through this case study of Rwanda, I advance an argument for approaching resilience as an uneven and incomplete process that is situated in peasants’ daily struggles for autonomy, security, and wellbeing. I show how climatic stressors entwine with unpredictable market dynamics, resource access constraints, gender relations, and other forces that impinge on agrarian societies. I highlight the value of considering everyday adaptation: incremental changes to land use and livelihood practices by which people address these myriad and intersecting challenges. I document the everyday nature and inherent unevenness of resilience through the stories of two plants: maize and sweet potato. While agrarian studies scholarship as tended to center humans and their institutions (Galvin Citation2018), a focus on human-plant relations enables us to see how climate resilience resides not in individuals or societies but in assemblages of people, crops, livestock, soil, technology, and climate. I show how some plants (maize in this case) become enrolled in assemblages that allow wealthier male farmers to mitigate climate risk while other plants (in this case sweet potatoes) form alliances with poorer households and women, enabling them to avert hunger following climatic shocks. This suggests the importance of examining interrelations among climate, crop ecology, and social dynamics in research and practice on climate change and development.

The resilience of development

Over the past decade, climate adaptation and greenhouse gas mitigation have become explicit goals of development policy and practice. These efforts to ‘mainstream’ climate change have drawn sustained criticism from political ecologists. Many have taken issue with the decontextualized nature of these climate-development programs, which tend to depict vulnerability and adaptation as ‘internal’ processes that are challenged by ‘external’ stressors, hiding how political-economic structures and cross-scale social processes give rise to climate vulnerabilities (e.g. Brown Citation2014; Ribot Citation2014; Watts Citation2015). Such a framing often leads to adaptation solutions of a technical and managerial nature (Taylor Citation2014; Nightingale et al. Citation2020) and to greenhouse gas mitigation policies that exacerbate land conflicts and support land grabbing in the name of the environment (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2012; Corbera, Hunsberger, and Vaddhanaphuti Citation2017). Many have also pointed out that policy interpretations of climate ‘resilience’ tend to evade attention to the concept's political nature, often referring to stability and self-sacrifice while overlooking how power dynamics influence people's abilities to persevere or not (Mikulewicz and Taylor Citation2020; Holt-Giménez, Shattuck, and Van Lammeren Citation2021). This partiality towards the colloquial meaning of resilience allows climate change to be invoked in ways that secure development's existing biases rather than catalyze long-needed reforms to development theory and practice (Carr Citation2019).

Together with this focus on shortcomings the shortcomings of climate-development research, political ecologists have advanced calls for understanding vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience as relational processes (Turner Citation2016). A relational approach views climate adaptation as embedded in social-environmental dynamics rather than a set of technical adjustments that societies employ in response to biophysical change (Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015). It allows us to see how adaptation or resilience for one group of people at one scale often implies vulnerability for another group at another scale (Taylor Citation2014; Goldman, Turner, and Daly Citation2018). It encourages us to focus on the negotiations about which adaptations are to be prioritized (Matin, Forrester, and Ensor Citation2018), how the meanings of ‘resilience’ and ‘adaptation’ are contested, and how these debates expose potentially contrasting values about future agrarian worlds (Borras et al. Citation2022). For instance, Burnham and Ma (Citation2018) show how drought adaptation strategies that emphasize building producers’ capacities for irrigated agriculture implicitly value commercial farming futures over subsistence futures. Within these negotiations lie opportunities for reworking power differentials or maintaining them (Forsyth and Evans Citation2013). A relational lens has thus been foundational in political ecology research on the cross-scalar social relations that co-produce climate injustices (Sultana Citation2022).

In this article, I combine this political ecology of resilience lens with emerging scholarship on human-plant relations. The latter illustrates how agrarian worlds are composed of assemblages linking plants and humans together with technologies, knowledge, infrastructure, capital, and finance (Galvin Citation2018). James Scott's (Citation2017) book Against the Grain provides a useful starting point. Scott calls for attention to how crops’ biophysical characteristics and life cycles become dynamically linked with human social relations in ways that can enable and constrain certain groups of people. He argues that grains such as wheat became quintessential political crops for early states in part because their biophysical properties make them innately governable. Grains mature above ground and ripen in unison, facilitating legible rural landscapes. Once harvested, grains can be dried, stored, and transported with high value relative to their volume and weight. Grains’ legibility thereby accompanies them from farms to cities. By contrast, Scott depicts tubers such as cassava as escape crops because they demand little labor once planted, ripen underground, and their roots remain edible for two years after maturation. These traits entice subsistence producers who prioritize flexibility, autonomy, and a secure localized food source.

While Scott (Citation2017) developed this concept through historical assessments of early states, scholars have recently applied it to examine class and labor dynamics in contemporary agri-food systems. For instance, Sinha (Citation2022) adapts the political crops lens to account for the diffuse power that characterizes agrarian capitalism in India, where capital and labor circulate within and beyond state boundaries. She demonstrates how the material properties of the plants shape production relations and markets downstream of production, which in turn can impinge on producers’ livelihoods and risk management. With case studies from Malawi and India, Jakobsen and Westengen (Citation2021) show maize can help consolidate agribusiness power over food systems while also supporting assemblages of food sovereignty – that is, where the decisions about what and how to produce and consume food reside with subsistence producers. Similarly, Roman and Westengen (Citation2022) document how cassava was central to Brazil's colonization and to resistance in communities of former escaped slaves because the tuber's material properties resist standardization, instead fostering collective identity and strengthening community bonds. A red thread in this nascent literature is that political outcomes of control or resistance do not result solely from plants’ biophysical characteristics or from pure human intention, but instead emerge from social-material relations linking humans and plants in a given place and time.

Merging a political ecology approach of relational resilience with this thinking on human-plant relations helps me peel apart interlocking processes of agrarian change and climate change amid Africa's Green Revolution. As I demonstrate below, some plant-human assemblages distribute climate risk onto the most marginalized people while others support efforts to forge more equitable adaptations in the face of climatic uncertainty and top-down agricultural policies.

Making Rwanda’s green revolution ‘climate smart’

Rwanda's agricultural intensification policies have earned the country praise from development agencies while consistently drawing criticism from academics. What both groups would likely agree upon is that the policies are ambitious. Since 2007, Rwandan households have been compelled to settle in villages, consolidate land in monoculture, and cultivate market-oriented crops (potato, bean, rice, maize, and wheat). A top-down governance regime compels local and regional authorities to ensure that land is converted to ‘modern’ techniques (Heinen Citation2022). What this means in practice is that traditional crops and polyculture land use systems are strongly discouraged. In accordance with national targets, regional agronomists and government-certified agro-dealers select the crops to grow each season. The strictness of land use regulations varies within and between rural communities depending on where the government has invested in agronomic infrastructure. In drained marshlands and terraced fields, producers have a little leeway. They can be fined or have land confiscated by the state if they fail to plant the crop selected by authorities. Penalties are less severe for other fields, particularly those not visible from a principal road, where administrators tend to look the other way.

Development scholars tend to portray Rwanda's Green Revolution as an imposed vision of rural modernization (Dawson, Martin, and Sikor Citation2016). Criticism has often centered on the authoritarian nature of the government's approach and how it poorly fits with local realities. For instance, accounts emerged of how agricultural modernization enabled the state and private sector to appropriate common property (Huggins Citation2014). Studies have found that these policies have exacerbated food insecurity for the rural poor (Dawson, Martin, and Sikor Citation2016; Clay Citation2018), with particularly negative consequences for women (Bigler et al. Citation2019). In their various ways, these and other studies find that Rwanda's agricultural policies have reproduced inequalities by inadequately addressing (or even aggravating) their underlying causes. The present paper builds on this work to consider how a mindset of agricultural modernization infuses the climate adaptation regime that has emerged in Rwanda over the past decade.

Since Rwanda's green revolution policies began in 2008, numerous initiatives of agricultural intensification have since been rebranded as ‘climate smart’. A key example is the Land Husbandry, Water Harvesting, and Hillside Irrigation project (LWH), a 135 million USD effort operated by the World Bank and Government of Rwanda from 2009 to 2018. LWH began with a focus on constructing terraces and draining marshlands for intensive, commercial agriculture. By 2015 the aims were described as ‘enhancing hillside agriculture resilience to climate change and variability through increased productivity and income’ (World Bank Citation2015, 10). At the project's close, the Bank claimed that it had created ‘climate-smart productive landscapes’ by ‘increasing productivity and livelihoods and reducing climate vulnerability’. This construction of climate resilience as synonymous with modernization is similarly articulated in Rwanda's 2011 Green Growth and Climate Resilience Strategy and is further fleshed out in a 2015 report, Climate Smart Agriculture in Rwanda (World Bank Citation2015). This report is articulated through the language of agricultural efficiency. For example, it attributes low yields to a combination of ‘the predominance of small-scale subsistence farming’ and climate change and states that ‘producers in drought-prone areas lack the knowledge, skills, and the adequate infrastructure to cope with such harsh conditions’ (p.4). In turn, CSA is framed as a set of technologies and practices that maintain or increase productivity while facilitating climate adaptation or greenhouse gas mitigation. Various crops and associated cultivation practices (e.g. ‘crop rotation’ and ‘recycling of crop residues’ for maize) are given a numeric ranking in terms of their ‘climate smartness.’ As I illustrate below, this framing of climate change and development falters because climate risk management is not reducible to discrete technologies or practices, but is situated within complex social-environmental dynamics that comprise human-plant relations in a given place and time.

CSA in Rwanda combines what Borras and co-authors (Citation2022) refer to as a ‘climate-emergency narrative’ with a ‘corporate-driven, technological narrative’. Smallholder producers are cast as victims because they lack technologies and knowledge to adapt. This positions states and corporations as natural protagonists because they offer the education and technology to ‘optimize inputs.’ Another example of this reductionist framing of CSA can be seen in the One Acre Fund (OAF), an American company that has partnered with the Rwandan government since 2011 to distribute hybrid seeds together with fertilizer and agricultural training. Through their extensive networks which reach hundreds of thousands of households (One Acre Fund Citation2016), OAF has been a critical cog in Rwanda's Green Revolution ambitions. Despite little change to their business model, OAF recently began claiming that their market-based input dissemination service is ‘the ideal delivery system for our growing suite of climate smart products and services’ (Citation2020). To validate this system as a climate smart solution, OAF deploys a climate change framing of smallholder producers as simultaneously vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and responsible for climate change:

At One Acre Fund we understand that smallholders are on the front lines of tackling climate change around the globe. But, inevitably, as part of the agricultural ecosystem, they are also responsible for contributing to that change. For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa, producers without sustainable avenues for increasing their yields are often compelled to “harvest” their natural environments through deforestation, converting natural land to farmland, and participating in other unsustainable agricultural practices such as monoculture which can lead to issues of soil degradation. This scenario creates a cycle of land breakdown and poor yields that, over time, accelerates the effects of climate change. (One Acre Fund Citation2020)

Study site and methodology

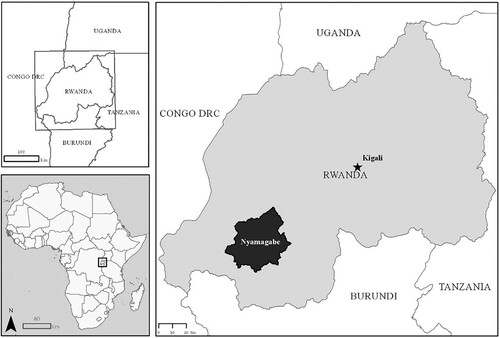

This research was conducted from 2014 to 2016 in four umudugudu (rural communities) in Southwest Rwanda's Nyamagabe district (). Nyamagabe has long counted among Rwanda's poorest regions. Its underperformance on economic growth and food security indicators is often attributed to the steep slopes, narrow valleys, and infertile, rocky, acidic soils that characterize the region. Yet, for hundreds of years, Nyamagabe has supported high population densities through intensive agricultural systems that centered on the integration of crops and livestock, with pastures maintained through controlled burning (Olson Citation1994). Farming households manage soil fertility through locally-viable practices including intercropping, agroforestry, leasing additional fields, caring for others’ animals in exchange for manure, and collecting grasses for green manure.

Although these labor-intensive systems evolved to counter Nyamagabe's environmental limits, these agroecologies also expose deeply-rooted social disparities. As Jennifer Olson (Citation1994) shows with a detailed account of the region's political ecology, inequities in land and animals are at the heart of rural Nyamagabe's continued poverty. In precolonial Nyamagabe, land use was organized through a feudal monarchy, where ruling Tutsi pastoralists allotted land and animals to Hutu agriculturalists in exchange for portions of their crop production (Maquet and Naigiziki Citation1957). Through manure, animals transferred nutrients from distant grasslands to intensively cultivated fields near households (de Lame Citation2005). Inequities in resource access were exacerbated during the colonial period, leading to further intensification as land grew scarcer. When famines resulted, administrators brushed away demands for land redistribution by attributing low crop yields to climatic fluctuations and soil erosion caused by inappropriate farming techniques (Harroy Citation1944). These inequitable though finely-tuned agro-ecological practices have persisted (albeit with important evolutions whose precise nature is beyond the scope of this paper) into the present day. As Olson (Citation1994) notes and my findings uphold, uneven access to these resources has meant that the soil fertility gap has continuously widened on class and gender lines.

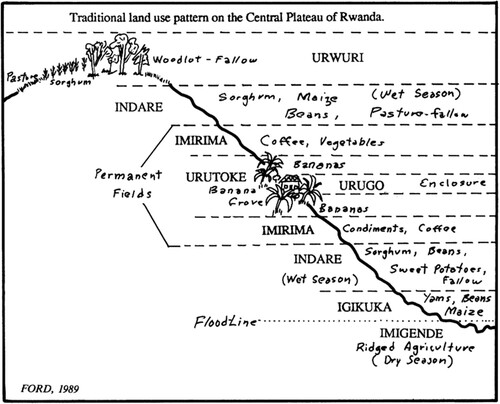

Contemporary agriculture in Nyamagabe and throughout the country (at least prior to the influence of Rwanda's LUC Program) is characterized by diverse polyculture systems. Soil moisture and fertility vary greatly over short distances and depending on the season. A typical household cultivates a wide range of crops each season across a patchwork of small fields at various elevations. (from Ford Citation1990) shows a simplified rendition of this land use pattern. Urutoke and Imirima (permanent fields of perennial crops) surround the household, which until Rwanda's villagization program was typically located somewhere near the middle of the hill. Indare (rainy season fields of staple tubers and grains) are planted above or below the household, and Imigende (dry season fields) are located in low-lying valleys or marshland, which retain more moisture throughout the year and therefore serve an important purpose of enabling continued food supply during the lean months (Ford Citation1990).

Figure 2. Rendition of a spatially and temporally heterogeneous agroecology in twentieth century Rwanda. Figure from Ford (Citation1990).

This system takes advantage of the diverse microclimates offered by the mountainous landscape. It enables producers to optimize a combination of low-risk food security crops with crops that are typically sold. Cultivating fields in diverse locations allows farm families to distribute risk of either insufficient rainfall or torrential rains – both of which have become increasingly common in Nyamagabe. Nearly all households in the study site could be classified as semi-subsistence producers. The preference being to consume food produced by the household (mainly bean, sweet potato, peas, and potato), with surplus crops and cash crops (banana, tea, sorghum, potato, cassava, and sweet potato) sold to meet household expenses. With two distinct rainy and dry seasons each year, the labor and social calendar has been structured around key periods of agricultural labor. This system also ensures a nearly continuous supply of food throughout the year.

Nyamagabe makes for an important case study of Rwanda's efforts to improve agricultural productivity in part because of the innate challenges to commercial agriculture in the region. The Crop Intensification Program is strongly represented in the region, with 90% of the study participants in the four communities operating land that came under the jurisdiction of the program. Within each of these communities, there are strong discrepancies in income, livestock, and access to land and other productive resources (see ). The wealthiest 10% of households owns around eight times as much land as the poorest 60% of households and five times as many livestock. Day in and day out, these class divides translate into starkly different experiences with Rwanda's agricultural policies. As I detail elsewhere (Clay Citation2018; Clay and King Citation2019), wealthier households are able to generate surplus crops and income from renting out their land while poorer households are forced to work in others’ fields to earn money for inputs prior to cultivating their own land, and they care for others’ animals in exchange for the manure, generally without benefiting from the profit of animal sale. These class divides mean that wealthier households have significant power in shaping decisions about what crops are grown in a particular area. Because landowners work with agronomists to select the crops grown in consolidated areas, they play a role in controlling what their tenants plant.

Table 1. Relative asset classes and correlating characteristics of survey respondent households. Each grouping of household was found to be significantly different (p < .01) from the others in terms of the factors in the leftmost column. Note that these data are based on participant responses to survey questions.

This study is based on two years of fieldwork conducted from 2014 to 2016 in four umudugudu (rural communities) in Nyamagabe together with a Rwandan research team. The findings reported here draw from qualitative and quantitative methods. We first conducted six open-ended focus group interviews to gain a sense of issues at the interface of climate change and agriculture, (each with between 7 and 16 participants). We built on this understanding through three months of ethnographic work (daily informal conversations and participant observation within the four communities), which helped us apprehend how agricultural practices and climate risk management are interrelated and shifting amid the ongoing Green Revolution campaign. This qualitative understanding allowed us to design a structured questionnaire, which (following pre-tests with 30 households to calibrate the questions) was administered to all households in the four umudugudu who were available and willing to participate. Surveying all households reduced selection bias as our 428 respondents represent more than 90% of households.

Following initial analysis of the above materials, we designed and conducted a parcel-level survey in which these 428 households’ 3017 parcels of land were visited, with detailed measurements of the crops grown, yields produced, and land use strategies employed. While research assistants were administering the second survey, I visited 40 households’ fields, asking follow-up questions that probed about why they made certain decisions. Together, the two surveys gave us a robust understanding of how livelihoods, resource access, food security, biophysical aspects of fields, and crop yields intersect in the context of Rwanda's Green Revolution policies and climatic shocks (two drought seasons and several flooding events that occurred from 2013 to 2016) to shape differential experiences. With the help of a research assistant, I then conducted 72 semi-structured interviews with 36 male and 36 female residents across the four study umudugudu (villages). Respondents were selected randomly after grouping survey respondents according to assets and income. Approximately half of respondents classified themselves as poorer than average while 25% classified themselves as wealthier than average and another 25% as among the poorest. Interviews averaged 1 hour and 22 minutes and focused on changing land use and labor dynamics, climate change experience, and gender roles in the context of Rwanda's Green Revolution policies. Most included visits to agricultural parcels, where further unstructured questions were asked. Finally, I conducted 23 semi-structured interviews with local and regional administrators (mayors, umudugudu leaders, agronomists, cooperative presidents, input distribution companies, and security officials, among others), also with a research assistant.

Shifting human-plant-climate dynamics

Maize: uneven resilience

On a dry day in September, around 80 community members gathered on the newly-constructed terraces in Nyamagabe to learn ‘modern maize planting techniques’. They watched as an OAF field manager – a young Rwandan man who hailed from an urban center – used a tape measure to space out holes in the soil and insert neon pink hybrid maize seeds. Producers, mostly men, only half-watched this performance. They had seen such demonstrations before and were more interested in the hundreds of sacs of fertilizer and seed that awaited distribution by OAF. These transactions of expert knowledge and modern agricultural inputs have become common across Rwanda. Maize (Zea mays) is a centerpiece of efforts to transform rural areas through agricultural modernization. By extension, it has also become key to efforts to make Rwanda's green revolution climate smart. To understand the challenges of assuring climate resilience through what is widely seen as a climatically risky crop, we must look to the human-plant relations surrounding maize.

Across East and Southern Africa, colonial governments compelled producers to adopt maize in the early twentieth century and the crop became a staple in most countries (Jakobsen and Westengen Citation2021). The story of colonial maize diverged significantly in Rwanda. Belgian administrators had little success encouraging its adoption in food or farming systems. Producers maintained a preference for sorghum and finger millet, which relied on complex land use practices that were embedded in systems of social reciprocity and collective labor. In an effort to evict these native grains, colonial administrators implemented land-use regulations. Citing fears of land degradation, they outlawed the burning of grasses, a vital practice for millet cultivation (Uwizeyimana Citation1991). Still, maize never became a staple in rural Rwanda. Instead, sweet potato filled the caloric niche left vacant by the millet that could no longer be cultivated (Olson Citation1994).

Over the past 15 years, however, maize has been the star of Rwanda's Green Revolution. Countrywide, the area planted annually in maize rose from 100,000 hectares in 2007–260,000 hectares in 2017 (Ngango and Hong Citation2021). This surge is attributed to Rwanda's LUC program and to OAF, which work synergistically to compel planting of maize and supply the required inputs. Rwanda's emerging maize regime thus ties smallholder producers to numerous external actors, including seed and fertilizer companies, private-sector index-based insurance providers, government agronomists, and consumers in urban marketplaces. Several biophysical properties of maize attract the attention of these diverse entities. The straight, tall, golden maize stalks are visible from afar, ensuring legible landscapes of uniform plants. Maize goes hand-in-hand with terrace construction and marshland draining, both of which function to render land legible by the state and investible in its vision of modern agriculture. The biophysical nature of hybrid maize further reinforces the need for large contiguous areas planted with the same seeds. This is because hybrid maize is open-pollinating, meaning it can cross-pollinate with nearby maize plants, whether they are hybrid or locally-adapted varieties. To grow hybrid maize, Rwandan producers, therefore, need to purchase new seeds every season. This contrasts to the archetypal hybrid rice varieties of Asia's Green Revolution, which producers needed only to purchase once because rice is self-pollinating (Patel Citation2013). The fact that maize is open-pollinating incentivizes the state to ensure that producers consolidate land in maize planting areas. If they do not, then more expensive high-yielding varieties may cross-pollinate with local varieties, resulting in irregularly-shaped seeds that are worth less in commercial markets.

The need to purchase seed each season also ties Rwandan producers into agreements with seed distributors, enabling global circuits of capital and knowledge to reach into rural landscapes and households. OAF distributes the majority of maize seed in ‘technology bundles’ that include synthetic fertilizer and crop insurance. OAF allocates these bundles on credit, with a high-interest loan (in 2015 the interest rate was 19%) to be repaid at the end of the growing season. OAF is powerful in Rwanda's maize assemblage, acting as a vehicle for ideals, capital, and seeds. Through OAF, maize has finally made inroads in Rwanda after years of failed colonial efforts. And in maize, OAF has found an ideal conduit for its brand of corporate philanthropy that relies on continuously scaling up through recruiting more producers in order to generate enough revenue to pay investors back and keep expanding. As OAF's Investments Director put it, the company aspires to become ‘the Amazon for rural producers’ (Parrucci Citation2018).

Rwanda's maize assemblage enrolls smallholder producers in ways that reinforce gendered labor practices and class divides. Respondents described how men had all but abandoned agriculture in Nyamagabe until the promise of commercialized, modern agriculture pulled them back. Men described maize as a potent symbol of the country's progress and criticized systems of intercropping as ignorant – adhering to the state's narrative. Many women pointed out that men contribute relatively little to the household agricultural labor burden but that they increasingly pressure their wives to plant maize. Women also condemned hybrid maize as risky due to its need for high soil fertility and its intolerance of dry spells relative to locally-adapted varieties. As such some women hid locally-adapted maize seeds in nondescript places (e.g. broken earthenware containers), which they planted in LUC areas so that administrators and husbands would see that they complied with the policy, yet without losing money to purchased inputs that they saw as likely to fail in the event of drought. Maize earned a reputation as environmentally risky for good reason. In 2014 and 2016, droughts decimated nearly all of the hybrid maize planted in LUC areas on hillsides. And in 2014 and 2015 floods completely destroyed maize planted in LUC areas in marshlands. Many female respondents described maize as a gamble that is not worth the wager of household food security.

By 2021, OAF supplies more than one million customers, claiming to support the poorest of the poor. However, in Nyamagabe, respondents described how OAF is only viable for wealthy producers who can succeed with maize because they have more fertile land, more access to inputs, and more assets that enable them to bear the risk of not being able to repay a high-interest loan in the event of a drought or heavy rain that destroys their crops. These wealthier male respondents often see maize as an important step out of subsistence agricultural livelihoods. Through fertilizer inputs for maize and the increased availability of people who are willing to farm via sharecropping arrangements, wealthier landowners have found a pathway to enhance the fertility of their fields. On the flip side, many poorer producers described their frustrations at laboring in rented fields for years and applying copious manure only to have the owner discontinue the agreement once the land was fertile enough. In this sense, maize enables control and appropriation of rents not only by the state and corporations, but also by local elites. Most problematically, the poorest households (who are arguably the least prepared to succeed with agricultural modernization) were forced to plant a higher proportion of their land (45%) in government-selected crops than wealthier households, who only planted 27% of their land.

Recognizing the substantial climate risk of maize in Rwanda, OAF has sought options for producers to insure its maize. OAF contacted Agriculture and Climate Risk Enterprise (ACRE), a crop insurance initiative founded by the seed and pesticide conglomerate Syngenta and with ties to AGRA. Syngenta Foundation conducted a feasibility study of ten crop value chains in Rwanda to guide provision of crop weather insurance for smallholders. The study identified maize as the most viable crop because it would garner enough insurance premiums after three years to make it financially viable for private sector investment (Syngenta Foundation Citation2012). ACRE's insurance is ‘index-based,’ using satellite imagery to determine aberrations in rainfall in a given season. The smallest pixel that can be viewed is 4 km, meaning that microclimates cannot be assessed, a crucial oversight in a mountainous country such as Rwanda. My study participants reported that this has resulted in them not being compensated for numerous climatic shocks that have decimated maize harvests. Nevertheless, OAF now requires customers to purchase crop insurance for maize as part of its bundle of services. Through this financialization of climate risk, smallholder producers have thus become tied into global capital circuits. While maize is a cornerstone of efforts to make Rwanda's green revolution climate smart, it offers producers a costly illusion of climate resilience and a disproportionate burden of climatic risk.

Despite the hopes for maize to generate economic growth, the crop has continuously failed to deliver countrywide. Even assessments by Rwanda's Ministry of Agriculture find that maize had among the lowest revenues per hectare from 2014 to 2017 – providing only a third the revenue of sweet potato (GoR Citation2018). The lackluster performance of maize is frequently attributed to ‘sub-optimal agricultural practices,’ with ‘agricultural inputs and best management practices’ prescribed as solutions to overcome persistent ‘yield gaps’ (Bucagu et al. Citation2020, 1269). However, even in years when maize yields are relatively high, respondents noted that the price of maize bottoms out due to oversupply. While in theory producers could wait to sell their harvests until demand increases, those without adequate storage risk contamination by aflatoxins (a pathogenic fungi that thrives in hot, humid conditions). For example, in 2017 Africa Improved Foods (a large maize processor in Kigali established by Rwanda's government with support from AGRA) rejected 90% of maize due to the presence of aflatoxins (AIF Citation2021). Such market dynamics and value chain stages are seldom considered within CSA, where the overriding focus is on the production phase. In part through the illusion of climate-smart development, maize has pulled semi-subsistence producer deeper into uneven risk allocation and strengthened control by government and corporate actors.

Sweet potato: everyday adaptation

Above I explored the paradox of enrolling a climatically risky crop in a ‘climate-smart’ program of agricultural modernization. Here I focus on sweet potato to consider the inverse: the ramifications of limiting cultivation of a crop that has long been a fixture of climate risk mitigation. A staple throughout rural Rwanda, sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) has been the country's most important source of calories since at least the 1980s (Tardif-Douglin Citation1991). At 88 kg per person, Rwanda maintains the highest per capita production of sweet potatoes in the world (Theisen Citation2020). In southwest Rwanda, acidic, low-phosphorus soils have made sweet potatoes particularly important due to the challenges of growing grain crops in the absence of manure and synthetic fertilizer (Olson Citation1994, and discussed above about maize). As my study participants repeatedly exclaimed: ‘sweet potato is the food of this place.’

This was not always the case. Nearly 100 years ago, producers resisted colonial administrators’ demands that they grow sweet potatoes. A 1924 law sought to prevent famines by compelling producers to maintain 0.15 hectare of sweet potato and cassava per adult (Ministere des Colonies Citation1954).Footnote4 Yet, Rwandans preferred sorghum and millet to sweet potatoes, often uprooting the tuber once colonial authorities were no longer in sight (Everaerts Citation1939). Nevertheless, as land became increasingly scarce and millet production untenable due to laws against burning grasses, sweet potatoes took on a greater importance. The tuber offered dependable, calorie-rich (if relatively low nutrient) yields. By the 1980s, government food security planning centered on sweet potatoes (Tardif-Douglin Citation1991). In the chaos that followed the 1994 war and genocide, sweet potatoes became particularly important as a low-risk crop.

How did sweet potatoes shift from unwanted colonial imposition to a fixture of risk-averse semi-subsistence farming in Rwanda? To answer this question, we can look to human-plant relations. Sweet potatoes’ malleability has enabled them to co-adapt with complex farming systems that developed amid land scarcity, inequality, irregular rainfall, and gendered household responsibilities. First, sweet potato life cycles are well-suited to Rwanda's bimodal rainy seasons. If planted during one of the two rainy seasons, they typically retain sufficient soil moisture through dry seasons, enabling continuous cultivation throughout the year. Second, because sweet potatoes develop below ground, they invite intercropping with above-ground beans, banana, sorghum, or maize. Intercropping has a dual purpose of ensuring a continuous supply of sweet potatoes and reducing soil erosion by maintaining ground cover.Footnote5 Sweet potatoes further optimize subsistence systems because they require relatively little labor and no purchased inputs. While synthetic and organic fertilizers are essential for maize, sweet potatoes require only ‘green manure’ cut from trees. And the tubers are propagated by planting vines, which are typically sourced from a recently harvested field or from neighbors and family.

Sweet potatoes are also malleable in terms of consumption. They are typically harvested immediately before consumption or sale and can remain in the ground for two years after ripening, where they will continue to grow. Women frequently likened this to ‘a bank account.’ Sweet potatoes and their vines can also be diverted to feed livestock, playing an important role in mixed-crop livestock systems. Their reliability has given sweet potatoes a central role in feeding the household (particularly children) and its livestock. As such, sweet potatoes are a strongly gendered crop in Rwanda, associated exclusively with women given their roles in ensuring food for children and livestock. Underscoring this deep gendered nature, respondents laughed at the idea of a man harvesting sweet potatoes. As important as they are for food security, sweet potatoes are also a vital cash crop for women, who sell the tubers at night markets to pay for clothing, food, or children's school fees. Sweet potatoes’ unique ability to operate as both a food security crop and a market crop has long provided small holders the flexibility vital to supporting household resilience in the face of uncertainty.

In short, sweet potatoes help households – through the labor of women – to diffuse climatic risk and space out labor across the year. However, the same features that make sweet potato emblematic of complex semi-subsistence farming systems have made them the target of government efforts to abolish subsistence farming. Respondents discussed the rampant uprooting of sweet potatoes by local leaders who were enforcing the government's LUC program. This limitation on the undisputed staple food had drastic effects in Nyamagabe. It led to increased hunger for 39% of all households surveyed and 49% of female-headed households. The effects were most stringent for poorer women, who explained how their food security, sovereignty, and wellbeing had eroded due to government policies. The places where the poorest households had once planted sweet potatoes – hillsides and marshlands – are the most strictly controlled. These are the government's priority areas of agricultural modernization and sites of ‘climate smart’ initiatives that constructed terraces and drained marshlands. Prior to this, poorer households planted sweet potatoes in low-lying areas and marshlands as a way to buffer against drought. The substantial labor required to prepare marshlands meant that only those most in need of a safety net would cultivate there. Marshlands became especially important in low-rainfall years. After consolidation, small plots of marshland cost 3000 to rent for a three-month period. Producers were obligated to cultivate maize or horticulture crops for export. This made marshlands off-limits to poorer households and undesirable to all but the wealthiest who could pay for inputs, including labor. During drought seasons in 2014 and 2016, drastic reduction of sweet potato acreage had cascading effects for poor households and women. When drought devastated maize harvests, they worked in the fields of wealthier landholders for money to buy food. Yet, the vastly reduced supply of sweet potatoes caused market prices to quadruple. And the shortage of planting material led to selling vines, a once-unheard of practice.

However, the materiality of sweet potatoes also enabled everyday adaptation. Following the 2014 drought, producers gradually returned to cultivating sweet potatoes, although in different ways than before. Women explained that ‘it is like stealing.’ They discussed how people did in fact continue to plant sweet potatoes, but only in ‘hidden places’ in akabande (the deep valleys that mark the border between communities). While the authorities uprooted sweet potatoes planted on hillsides, they looked the other way when the crop was planted in valleys. This was because valleys are hidden from view and because it is difficult to attribute valley land to a particular household as the plots are often a 20-minute walk or more from the homestead. Valley land thus became crucial for the mitigation of climatic shocks.

The practice of planting sweet potatoes in valley land can be considered a mode of everyday adaptation to coercive land-use governance as well as droughts and floods that routinely devastated fields planted in the LUC program. Yet, access to hidden areas in the akabande is uneven. Only 37% of female-headed households had access compared to 56% of all households. The importance of sweet potato amid drought, coupled with the fact that the crop could only be grown in valleys, caused valley land to skyrocket in value. Wealthier households, who own the majority of this land, have increased land rental fees. Before long, many sweet potato plots in hidden places were operated on a sharecropping basis, where tenants generally owe half of the resulting crop production to landowners (although this can be negotiated). Even while this is recognized as an exploitative institution, respondents noted that it has become increasingly common due to the need for valley land for sweet potatoes. Moreover, while 31% of female-headed households no longer sell any sweet potatoes, wealthier households have accumulated more valley land and increased sales of sweet potatoes, capitalizing on their scarcity. Additionally, where households of modest means own some valley land, it is typically located far away, creating a substantial labor burden for women who need to walk daily to the fields to harvest sweet potatoes for their families to eat. In summary, the inability of agricultural policies and CSA programs to acknowledge the keystone role of sweet potatoes in climate risk management spurred transformations that have deepened coercive land-labor dynamics. This allows us to see how agrarian change, climate change, and agricultural development are linked processes that cannot be managed in isolation.

Reconceptualizing resilience as everyday struggle for wellbeing

To address the seemingly boundless uncertainties of global climate change, development agencies increasingly promote resilience as a vital aspect of their programs and policies. This paper has examined CSA, a prominent form of ‘climate resilient development’ that is currently being unrolled across Africa and throughout the global South. My case study of Rwanda demonstrates how CSA can have complex and uneven implications for the wellbeing of Africa's smallholder food producers. It showed how CSA has taken shape through large-scale, top-down initiatives that are embedded in a pre-existing paradigm of agricultural-led economic growth. In an effort to make Africa's green revolution climate smart, resilience is framed as the mitigation of external threats to increasing agricultural yields. Adaptation is viewed as a series of technological and managerial solutions intended to plan for and control climatic uncertainty. These solutions (crop insurance, water management infrastructure, climate information services, and improved seeds) all help to streamline a Green Revolution technology package that prioritizes input-led intensification to install economies of scale. By focusing on rural communities’ experiences with climate-development initiatives in Rwanda, I have identified crucial limits to these framings of resilience and adaptation. Simply put, the technocratic vision of resilience advanced by CSA is out of step with the lived experiences of climate and agrarian change among smallholder food producers, for whom resilience is inseparable from efforts to procure security, wellbeing, and autonomy.

More specifically, my findings show how programs that reduce climate change adaptation to a set of technologies can undermine the intricate social-ecological dynamics at the heart of smallholders’ climate risk management strategies. This suggests that equating climate resilience with agricultural efficiency can have negative implications for those already on the margins, for whom land use strategies that may appear inefficient can be carefully orchestrated efforts to mitigate climate variability, shocks, and change. The technological, finance, infrastructure, and market innovations put forward as climate solutions (as in the case above of ‘climate smart’ maize) exacerbate agrarian inequities because they favor wealthier male producers who are already integrated in cash economies – the same groups typically favored by Green Revolution technologies. Perhaps unsurprisingly then, Nyamagabe residents unable to benefit from agricultural modernization described CSA technologies as indistinguishable from other top-down management efforts that limit their sovereignty over land use. This shows how a Green Revolution mindset can all too easily permeate efforts to align agricultural development with climate adaptation. It underscores the need to actively reimagine agricultural development paradigms during a time of global climate change. It also suggests the inseparability of climate justice and agrarian justice (Borras and Franco Citation2018) and the importance of articulating climate resilience through attention to peasant rights over land and decision-making processes (Walsh-Dilley, Wolford, and McCarthy Citation2016).

More generally, this study exposes a harsh irony of climate-development initiatives. As shown in the WEF quote that opened this article, development programming frequently depicts subsistence producers as innately vulnerable and unable to adapt to climate change. The technologies put forth as climate smart solutions (crop insurance, high-yielding seeds, climate information services, irrigation infrastructure, and terraces) further consolidate agency in the hands of experts, solidifying state and corporate control over rural communities. This further strips away agency from the vulnerable, debilitating locally rooted systems of managing social, economic, and environmental uncertainties. Of course, as others have pointed out, appropriating the cause of the vulnerable may be a deliberate adaptation by states and corporations, many of which stand to benefit from advancing climate solutions that rely on market, financial, and technical innovations (Barnett Citation2020; Paprocki Citation2021). I am certainly not the first to consider the stranglehold that a technocratic mindset has on institutional responses to climate change. Abundant research has documented how efforts to build climate resilience through targeted adaptations can reproduce exclusionary power dynamics (for a summary see Nightingale et al. Citation2020). This has in turn inspired calls for explicitly decolonial approaches to climate adaptation research and practice (Borges-Méndez and Caron Citation2019; Haverkamp Citation2021; Santiago-Vera et al. Citation2021) and for climate-development initiatives that open up space for democratic deliberation about adaptation priorities (Mikulewicz Citation2018). In support of these more inclusive climate-development initiatives, I advance three interrelated arguments.

First, I corroborate calls (Allen et al. Citation2019; Chaigneau et al. Citation2022) for reframing resilience not as an idealized outcome of stability that automatically confers wellbeing but as a contested and contingent process: a struggle for viability, security, wellbeing, and autonomy – or what I call uneven resilience. By ignoring or obfuscating these struggles, programs that claim to offer climate resilient development risk effacing people's multifarious efforts to secure wellbeing amidst adverse social and environmental conditions. Conceptualizing resilience in this way throws into stark relief some of the conceits of CSA. However, I believe that approaching resilience as inherently uneven has applicability beyond assessing development programs that conflate agricultural modernization and climate change adaptation. It affords a simple reminder to bring resilience back down to Earth, to see it not as a balm but as a messy and contested process that is inseparable from broader agrarian change.

Second, and relatedly, I suggest the need for greater attention to how vulnerable populations creatively employ their knowledge and skills throughwhat I term everyday adaptations: land use and livelihood adjustments that are woven into the fabric of daily life. There is no need to reinvent the wheel here. Political ecologists and agrarian political economists have long focused on how everyday ‘local’ practices are dynamically linked to extra-local processes. As one example, Frances Cleaver (Citation2012) offers the useful metaphor of development as bricolage, where institutions of resource management are shaped through a continuous process of negotiation. Yet, such an analytic has not commonly featured in research on the interface of climate and agrarian change. Even while it is increasingly well known that global climate change has uneven and inequitable impacts on society, efforts to catalog these impacts remain abstracted from the experiences of people struggling with climate change alongside myriad other social-ecological challenges in their daily lives (Turner Citation2016; Goldman, Turner, and Daly Citation2018; Sultana Citation2022). There can be a fine line between climate adaptations and broader agrarian struggles (Borras et al. Citation2022). An empirical focus on the diverse, everyday adaptations that encompass yet are not solely provoked by climate change can help to subvert the predominant interpretation of climate as an external threat that can be managed by merely ‘getting the institutions right.’ If applied as more of a mindset than a framework, it may also help to open research, policy, and practice to subaltern knowledge and processes of adaptation, or what Haverkamp (Citation2021) calls ‘adaptation otherwise’.

Third, I suggest that attention to human-plant relations may prove fruitful for further work on climate change and agrarian struggles. This is one way (though certainly not the only way) to consider everyday adaptation because it helps ground interview and survey questions in context-specific practices, values, and challenges. Indeed, my analytical narrative centers on human-plant relations with maize and sweet potato because my interlocutors presented their experiences with Green Revolution and CSA programs through discussion of everyday activities that bound them to these plants in various ways. They explained how maize facilitates the further enrichment of those who can tolerate risk in accordance with a new regime of financialized resilience that is upheld through CSA. They also explained how sweet potatoes facilitate adaptation to climate change and the subtle resistance of state efforts to modernize rural landscapes. The plant's biophysical properties – together with the necessity of feeding families – encouraged women to defy top-down directives of agricultural modernization through creative yet labor-intensive practices. Yet, access to land to cultivate sweet potatoes is extremely uneven and requires significant labor by women to reach the far-away valley parcels. Thus, a focus on human-plant relations helps discern how resilience is uneven and partial. It is not intrinsic to plants, agronomic technologies, or social institutions but rather an emergent result of human-plant relations in a specific place and time. Analysis of shifting plant-human relations helps to develop a more embedded and relational understanding about how climate change adaptation and agrarian change are materially, historically and geographically situated.

Conclusions

The findings presented here speak to the need to revise CSA and related efforts to incorporate climate change concerns into agricultural development. By ascribing quantitative values of ‘climate smartness’ to crops, technologies, and management practices, CSA makes climate change governable by a constellation of powerful corporate and state actors. Empowering these actors now – through a discourse that simultaneously disempowers ‘climate-vulnerable peasant producers’ – will guarantee that external experts continue to govern climate change for years to come. Indeed, since its inception CSA has continued to tighten its grip on institutionalized responses to climate change in agrarian settings. As Scoones and Stirling (Citation2020) discuss regarding sustainability more broadly, such a foreclosure of alternative futures represents a significant agrarian injustice.

This article has reflected on how we might build more equitable and democratic responses to climate change by recognizing climate resilience as embedded in broader agrarian struggles for rural viability, autonomy, and wellbeing. It echoes calls (Walsh-Dilley, Wolford, and McCarthy Citation2016) for a rights-based interpretation of resilience to guide development operations in a time of global climate change. As the authors of the Working Group II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sixth assessment report (2022) suggest, climate resilient development should not be expected to manifest through a single decisive action or policy, but through the concerted work of diverse actors who strive to transform the values, ideologies, and social structures that underpin existing institutions. A focus on the everyday practices that constitute adaptation in agrarian environments could help seed such efforts.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for insightful feedback from four anonymous referees and the JPS editorial team. Numerous colleagues have helped me develop these arguments, including Alfred Bizoza, Dan Clay, Elissa Dickson, Brian King, and Karl Zimmerer. Thousands of people in Rwanda, who I will not name here, made this study possible. Any errors are my responsibility alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nathan Clay

Nathan Clay is a Researcher based with the Stockholm Resilience Center at Stockholm University. He was previously a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford. Nathan’s research focuses on environmental governance, rural livelihoods, intersectional vulnerability, and climate change. He examines how social-environmental change is unevenly experienced and how individuals, institutions, and social movements contest inequities at multiple scales.

Notes

1 AGRA was founded by the Rockefeller and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundations in 2006 with the purpose of moving the continent away from subsistence farming and towards commercial, intensive farming.

2 These initiatives hew closely to a vision of climate change adaptation informed by a conviction in the transformative power of agricultural modernization. This adaptation-as-modernization framing is not unique to Rwanda. It has become paradigmatic in development financing and practice throughout Africa (Mikulewicz and Taylor Citation2020).

3 CSA was developed by the World Bank, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), and the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

4 Famines were attributed to irregular rainfall and these crops were selected because they resisted drought, did not need to be harvested at the same time as other crops, and could be rapidly transported in case of regional food shortages (Harroy Citation1944).

5 When sweet potatoes are intercropped, the goal is often to reserve their vines as seedstock for a subsequent season. Other times, sweet potato is planted in an already-established field of sorghum, maize, or bean, with the plan to continue cultivating sweet potato after the principal crop is harvested.

References

- AIF. 2021. The Fight Against Aflatoxin. African Improved Foods. Accessed 22 March 2022. https://africaimprovedfoods.com/the-fight-against-aflatoxin/.

- Allen, Craig R., David G. Angeler, Brian C. Chaffin, Dirac Twidwell, and Ahjond Garmestani. 2019. “Resilience Reconciled.” Nature Sustainability 2: 898–900.

- Barnett, Jon. 2020. “Global Environmental Change II: Political Economies of Vulnerability to Climate Change.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (6): 1172–1184.

- Bigler, Christine, Michèle Amacker, Chantal Ingabire, and Eliud Birachi. 2019. “A View of the Transformation of Rwanda’s Highland Through the Lens of Gender: A Mixed-Method Study About Unequal Dependents on a Mountain System and Their Well-Being.” Journal of Rural Studies 69: 145–155.

- Bizoza, Alfred R. 2021. “Investigating the Effectiveness of Land use Consolidation– a Component of the Crop Intensification Programme in Rwanda.” Journal of Rural Studies 87: 213–225.

- Borges-Méndez, Ramón, and Cynthia Caron. 2019. “Decolonizing Resilience: The Case of Reconstructing the Coffee Region of Puerto Rico After Hurricanes Irma and Maria.” Journal of Extreme Events 6 (1). doi:10.1142/S2345737619400013.

- Borras, Saturnino M. Jr., and Jennifer C. Franco. 2018. “The Challenge of Locating Land-Based Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Politics Within a Social Justice Perspective: Towards an Idea of Agrarian Climate Justice.” Third World Quarterly 39 (7): 1308–1325.

- Borras, Saturnino M. Jr., Ian Scoones, Amita Baviskar, Marc Edelman, Nancy Lee Peluso, and Wendy Wolford. 2022. “Climate Change and Agrarian Struggles: An Invitation to Contribute to a JPS Forum.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (1): 1–28.

- Brown, Katrina. 2014. “Global Environmental Change I: A Social Turn for Resilience?” Progress in Human Geography 38 (1): 107–117.

- Bucagu, Charles, Alain Ndoli, Athanase R. Cyamweshi, Leon N. Nabahungu, Athanase Mukuralinda, and Philip Smethurst. 2020. “Determining and Managing Maize Yield Gaps in Rwanda.” Food Security 12: 1269–1282.

- Burnham, Morey, and Zhao Ma. 2018. “Multi-Scalar Pathways to Smallholder Adaptation.” World Development 108: 249–262.

- Carr, Edward. 2019. “Properties and Projects: Reconciling Resilience and Transformation for Adaptation and Development.” World Development 122: 70–84.

- Cavanagh, Connor Joseph, Anthony Kibet Chemarum, Paul Olav Vedeld, and Jon Geir Petursson. 2017. “Old Wine, New Bottles? Investigating the Differential Adoption of ‘Climate-Smart’ Agricultural Practices in Western Kenya.” Journal of Rural Studies 56: 114–123.

- Chaigneau, Tomas, Sarah Coulthard, Tim M. Daw, Lucy Szaboova, Laura Camfield, F. Stuart Chapin III, Des Gasper, et al. 2022. “Reconciling Well-Being and Resilience for Sustainable Development.” Nature Sustainability 5: 287–293.

- Chandra, Alvin, Karen E. McNamara, and Paul Dargusch. 2018. “Climate Smart Agriculture: Perspectives and Framings.” Climate Policy 18 (4): 526–541.

- Clapp, Jennifer, Peter Newell, and Zoe W. Brent. 2018. “The Global Political Economy of Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Systems.” Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (1): 80–88.

- Clay, Nathan. 2018. “Seeking Justice in Green Revolutions: Synergies and Trade-Offs Between Large-Scale and Smallholder Agricultural Intensification in Rwanda.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 97: 352–362.

- Clay, Nathan, and Brian King. 2019. “Smallholders’ Uneven Capacities to Adapt to Climate Change Amid Africa’s ‘Green Revolution’: Case Study of Rwanda’s Crop Intensification Program.” World Development 116: 1–14.

- Cleaver, Frances. 2012. Development Through Bricolage: Rethinking Institutions for Natural Resource Management, 240. London: Routledge.

- Corbera, Esteve, Carol Hunsberger, and Chayan Vaddhanaphuti. 2017. “Climate Change Policies, Land Grabbing and Conflict: Perspectives from Southeast Asia.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 38 (3): 297–304.

- Dawson, Neil, Adrian Martin, and Thomas Sikor. 2016. “Green Revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications of Imposed Innovation for the Wellbeing of Rural Smallholders.” World Development 78: 204–218.

- de Lame, Danielle. 2005. A Hill Among a Thousand: Transformations and Ruptures in Rural Rwanda. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Eriksen, S. H., A. J. Nightingale, and H. Eakin. 2015. “Reframing Adaptation: The Political Nature of Climate Change Adaptation.” Global Environmental Change 35: 523–533.

- Everaerts, E. 1939. “Monographie Agricole du Ruanda-Urundi.” Bulletin Agricole du Congo Belge 30 (3): 343–396.

- Fairhead, James, Melissa Leach, and Ian Scoones. 2012. “Green Grabbing: A New Appropriation of Nature?” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (2): 237–261.

- FAO. 2019. Agriculture and Climate Change – Challenges and Opportunities at the Global and Local Level – Collaboration on Climate-Smart Agriculture. Rome. 52 pp. https://www.fao.org/3/CA3204EN/ca3204en.pdf.

- Ford, Robert E. 1990. “The Dynamics of Human-Environment Interactions in the Tropical Montane Agrosystems of Rwanda: Implications for Economic Development and Environmental Stability.” Mountain Research and Development 10 (1): 43–63.

- Forsyth, T., and N. Evans. 2013. “What is Autonomous Adaptation? Resource Scarcity and Smallholder Agency in Thailand.” World Development 43: 56–66.

- Galvin, Shaila Seshia. 2018. “Interspecies Relations and Agrarian Worlds.” Annual Review of Anthropology 47 (1): 233–249.

- Goldman, Mara J., Matthew D. Turner, and Meaghan Daly. 2018. “A Critical Political Ecology of Human Dimensions of Climate Change: Epistemology, Ontology, and Ethics.” WIREs Climate Change 9(4). doi:10.1002/wcc.526.

- GoR. 2018. Strategic Plan for Agriculture Transformation 2018-2024: Planning for Wealth. Government of Rwanda.

- Harroy, Jean-Paul. 1944. Afrique, Terre Qui Meurt: La Degradation De Sols Africains Sous l’Influence De La Colonisation. Brussels: Academie Royale de Belgique.

- Haverkamp, Jamie. 2021. “Collaborative Survival and the Politics of Livability: Towards Adaptation Otherwise.” World Development 137. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105152.

- Heinen, Sebastian. 2022. “Rwanda’s Agricultural Transformation Revisited: Stagnating Food Production, Systematic Overestimation, and a Flawed Performance Contract System.” The Journal of Development Studies, doi:10.1080/00220388.2022.2069494.

- Holt-Giménez, Eric, Annie Shattuck, and Ilja Van Lammeren. 2021. “Thresholds of Resistance: Agroecology, Resilience and the Agrarian Question.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (4): 715–733.

- Huggins, C. 2014. “‘Control Grabbing’ and Small-Scale Agricultural Intensification: Emerging Patterns of State–Facilitated ‘Agricultural Investment’ in Rwanda.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (3): 365–384.

- Jakobsen, Jostein, and Ola T. Westengen. 2021. “The Imperial Maize Assemblage: Maize Dialectics in Malawi and India.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (3): 536–560.

- Karlsson, L., L. O. Naess, A. Nightingale, and J. Thompson. 2018. “‘Triple Wins’ or ‘Triple Faults’? Analyzing the Equity Implications of Policy Discourses on Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA).” Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (1): 150–174.

- Maquet, Jacques J., and S. Naigiziki 1957. “Les droits fonciers dans le Ruanda ancien.” Revue Congolaise 11 (4): 339–359.

- Matin, Nilufar, John Forrester, and Jonathan Ensor. 2018. “What is Equitable Resilience?” World Development 109: 197–205.

- Mikulewicz, Michael. 2018. “Politicizing Vulnerability and Adaptation: On the Need to Democratize Local Responses to Climate Impacts in Developing Countries.” Climate and Development 10 (1): 18–34.

- Mikulewicz, Michael, and Marcus Taylor. 2020. “Getting the Resilience Right: Climate Change and Development Policy in the ‘African Age’.” New Political Economy 25 (4): 626–641.

- Ministere des Colonies. 1954. L’Agriculture au Congo Belge et au Ruanda-Urundi de 1948 a 1952. Brusselles: Royaume de Belgique, Ministere des Colonie, Service de l’Agriculture.

- Newell, Peter, and Olivia Taylor. 2018. “Contested Landscapes: The Global Political Economy of Climate-Smart Agriculture.” Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (1): 108–129.

- Ngango, Jules, and Seungjee Hong. 2021. “Impacts of Land Tenure Security on Yield and Technical Efficiency of Maize Farmers in Rwanda.” Land Use Policy 107. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105488.

- Nightingale, Andrea J., Siri Eriksen, Marcus Taylor, Timothy Forsyth, Mark Pelling, Andrew Newsham, Emily Boyd, et al. 2020. “Beyond Technical Fixes: Climate Solutions and the Great Derangement.” Climate and Development 12 (4): 343–352.

- Ntirenganya, Emmanuel. 2016. Rwanda’s Longest Drought in Six Decades. New Times. 16 September 2016. Accessed 10 February 2018. http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/203577.

- Olson, Jennifer. 1994. Producer Responses to Land Degradation in Kikongoro, Rwanda. East Lansing: Michigan State University.

- One Acre Fund. 2016. Press Release: Tubura Announces Open Enrollment for Producers in Rwanda. May 24. Accessed 20 March 2022. https://oneacrefund.org/blog/press-release-tubura-announces-open-enrollment-producers-rwanda/.

- One Acre Fund. 2020. Building Resilient Climate Smart Agricultural Systems for Smallholder Producers. September 17. Accessed 20 March 2022. https://impakter.com/one-acre-fund-building-resilient-climate-smart-agricultural-systems-for-smallholder-producers/.

- Paprocki, Kasia. 2021. Threatening Dystopias: The Global Politics of Climate Change Adaptation in Bangladesh. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Parrucci, Andrew. 2018. A New Loan for Sustainable Agriculture: One Acre Fund. August 6. Accessed 30 March 2022. https://calvertimpactcapital.org/resources/a-new-loan-for-sustainable-agriculture-one-acre-fund.

- Patel, Raj. 2013. “The Long Green Revolution.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 40 (1): 1–63.

- Ribot, Jesse. 2014. “Cause and Response: Vulnerability and Climate in the Anthropocene.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (5): 667–705.

- Roman, Gabriel G, and Ola T. Westengen. 2022. “Taking Measure of an Escape Crop: Cassava Relationality in a Contemporary Quilombo-Remnant Community.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 130: 136-145.

- Santiago-Vera, T., P. M. Rosset, A. Saldivar, B. G. Ferguson, and V. E. Méndez. 2021. “Re-conceptualizing and Decolonizing Resilience from a Peasant Perspective.” Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 45 (10): 1422–1440.

- Scoones, Ian, and Andy Stirling. 2020. The Politics of Uncertainty: Challenges and Transformation. London: Routledge.

- Scott, James C. 2017. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Sinha, Shreya. 2022. “From Cotton to Paddy: Political Crops in the India Punjab.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 130: 146–154.

- Sultana, Farhana. 2022. “Critical Climate Justice.” The Geographical Journal 188 (1): 118–124.

- Syngenta Foundation. 2012. Crop and Livestock Insurance Feasibility Study: Final Report.

- Tardif-Douglin, David G. 1991. The Role of Sweet Potato in Rwanda’s Food System: The Transiton from Subsistence Orientation to Market Orientation. Ithaca: Cornell University.

- Taylor, Marcus. 2014. The Political Ecology of Climate Change Adaptation: Livelihoods, Agrarian Change, and the Conflicts of Development. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, Marcus. 2018. “Climate-smart Agriculture: What is it Good for?” Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (1): 89–107.

- Taylor, Marcus, and Suhas Bhasme. 2021. “Between Deficit Rains and Surplus Populations: The Political Ecology of a Climate-Resilient Village in South India.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 126: 431–440.

- Theisen, Kelly. 2020. Africa: Sweetpotato Production.

- Turner, Matthew D. 2016. “Climate Vulnerability as a Relational Concept.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 68: 29–38.

- Uwizeyimana, Laurien. 1991. Croissance demographique et production agricole au Rwanda: Impossible adequation? Cahiers du CIDEP 8. Louvain-la-Neuve: CIDEP.

- Walsh-Dilley, Marygold, Wendy Wolford, and James McCarthy. 2016. “Rights for Resilience: Food Sovereignty, Power, and Resilience in Development Practice.” Ecology and Society 21 (1): 11.

- Watts, Michael.2015. “Now and Then: The Origins of Political Ecology and the Rebirth of Adaptation as a form of Thought.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by Tom Perreault, Gavin Bridge, and James McCarthy, 19–50. London: Routledge..

- WEF. 2016. 4 Factors Holding Back Africa’s Small-Scale Producers. Accessed 20 March 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/05/4-factors-holding-back-african-producers/.

- World Bank. 2016. World Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan. Accessed 20 March 2022. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/24451.

- World Bank; CIAT. 2015. Climate-Smart Agriculture in Rwanda. Washington D.C.: The World Bank Group.