ABSTRACT

In East Africa, pastoralist systems are undergoing rapid transformation due to land enclosures, benefit distributions associated with new land uses, shifting social relations, and changing authority and governance structures. We apply a critical analysis of the institutions that mediate access and benefits across a complex mosaic of property relations within Ilkisongo Maasai pastoralist land in southern Kenya. Our analysis elucidates how global and national influences have interacted with shifting dynamics of socio-cultural norms and rules regarding access to create new benefit pathways, cascading patterns of accumulation and social differentiation, and diffuse institutional controls over land.

Introduction

A growing literature has emphasized ‘green grabbing’ and ‘accumulation by dispossession’ in pastoralist lands in East Africa (e.g. Benjaminsen and Bryceson Citation2012; Bersaglio and Cleaver Citation2018; Bluwstein et al. Citation2018). This literature links changes in land control and different types of associated benefit streams with complex, variegated interactions between patterns of international investment, reforms in governance processes at multiple scales, and local social responses ‘from below’ (Hall et al. Citation2015; Lund and Boone Citation2013; Gardner Citation2012). While processes of enclosure and dispossession often pose conspicuous, broad-scale patterns of exclusion from land and benefits, more subtle, diffuse changes in access, claiming, and exclusion at local scales can also have important implications for livelihood systems (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2012; Peluso and Lund Citation2011). Extensive pastoralist systems are distinguished by flexible, adaptive livestock husbandry practices and socio-cultural relations that enable a production strategy that benefits from environmental variability (Krätli and Schareika Citation2010). These systems have been characterized by their ‘open property regimes’ or 'complex mosaics of property' (Moritz Citation2016; Robinson Citation2019), with plural, overlapping rights and authorities, and highly dynamic social processes of inclusion and exclusion that all play key roles in access to land and other resources (German et al. Citation2017; Gongbuzeren, Huntsinger, and Li Citation2018 ; Scoones Citation2021). These, as well as other dynamic socio-cultural and environmental relations, require that a distinct set of analytical lenses be applied in order to understand the emerging patterns of accumulation and social differentiation, and ongoing, rapid transformations occurring in these globally important livelihood systems (Scoones Citation2021).

In this paper, we focus on how informal and formal institutions shape benefit pathways, processes of accumulation, and land control in extensive pastoralist systems that are undergoing transformation. We do so with a case study of changes in livelihood practices, social differentiation, and struggles among Ilkisongo Maasai over collectively titled land in Kajiado County in southern Kenya. As seen throughout East Africa, the interaction of complex recent changes in socio-cultural norms, and unequal abilities to access, benefit from, and control land, have profoundly impacted emerging patterns of social differentiation among pastoralists (Goldman and Riosmena Citation2013; Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015; Lind et al. Citation2020; Unks et al. Citation2019). A range of factors, including structural adjustment policies and decentralization reforms, have also bolstered recent patterns of investment and influence by new political actors, that have produced new sources of capital, new pressures for land use, and cascading changes in social relations (German, Unks, and King Citation2017; Lind, Okenwa, and Scoones Citation2020; Unks Citation2022). Explicit enclosure and establishment of new boundaries within Kenyan Ilkisongo Maasai land has resulted in both dispossession and loss of access to grazing resources. However, changes due to new political and economic dynamics, and the expansion of wildlife conservation and industries such as mining and cash crop farming, have also influenced processes of accessing and benefiting from land in more subtle ways. Focusing on how institutions mediate differentiated abilities to access and benefit from land within a complex mosaic of property relations, we elucidate (1) emergent pathways of accessing and benefiting from land within Ilkisongo Maasai communities; (2) how these pathways are recursively reproducing social differentiation; and (3) how changing livelihoods and social difference relate to local politics of accumulation and land control.

Previous studies among pastoralists in East Africa have shown how privatization, wildlife conservation practices that exclude access to land, changing social relations, and new practices of supplementing livestock mobility all shape differential abilities to access and benefit from land (Goldman and Riosmena Citation2013; Unks et al. Citation2019). Here we expand this approach to understand the various ways in which multiple, overlapping institutions mediate how people benefit from resources, but also shape processes of accumulation, both of which underpin changing local politics, social relations, and views of collectively titled land. In Kajiado County, the majority of collectively titled Maasai lands, known as group ranches (GRs), have subdivided and dissolved since establishment in the 1970s (Mwangi Citation2007a). However, several GRs surrounding Amboseli National Park (ANP) have remained collectively titled. Amidst concerns surrounding the ecological implications of subdivision, fencing, and farming (Groom and Western Citation2013), wildlife conservation NGOs have sought to maintain open, contiguous rangelands surrounding ANP (Western Citation1994), and spearheaded a range of interventions intended to sustain collective land tenure (Unks Citation2022). At the time of writing, however, these GRs have begun to formally subdivide. Sweeping changes in livelihood practices, market interactions, socio-cultural relations, and state and non-state actor influence over land use have also transformed the way that Ilkisongo Maasai relate to land (BurnSilver Citation2009; Campbell et al. Citation2005; Kituyi Citation1990; Lind et al. Citation2020; Roque de Pinho Citation2009; Southgate and Hulme Citation1996). In this context, we asked how Ilkisongo Maasai views of collectively titled land have been impacted by changing institutional configurations of resource use and differentiated abilities to benefit from land. In addressing this question, we contribute to larger debates about pastoralist property relations, land tenure, and ongoing changes in land control in relation to global, national, and local processes.

To trace the evolution of the overlapping informal and formal rules and norms that mediate access to variable resources and benefits from land, we apply a non-normative view of institutions (Johnson Citation2004), and understand them as inherently social, relational, and historically contingent (Cleaver Citation2012). We draw on critical literature on institutions (Cleaver Citation2012), access (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003), and entitlements (Leach, Mearns, and Scoones Citation1999) to expand our understanding of social differentiation across a complex mosaic (Robinson Citation2019) of property relations and land use. Focusing on the relationship between access, benefit streams, and land control (Peluso and Lund Citation2011), we situate socially differentiated abilities to access, benefit from, and control land and resources in relation to a broad spectrum of social processes, local authority structures and functions, and wider political and economic shifts. Through examining the ‘webs and bundles of powers’ (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003) that extend across complex systems of access and benefits, we highlight how different actors produce and reproduce asymmetries through their abilities to shape institutional configurations (Cleaver and de Koning Citation2015) and mediate processes of inclusion and exclusion (Lund Citation2016 ; Sikor and Lund Citation2009). We argue that applying this approach to agrarian questions of production, accumulation, and politics (Bernstein Citation1996, Citation2010), while considering important socio-cultural dimensions of variegated transformations (Edelman and Wolford Citation2017), can expand understandings of ongoing patterns of shifts in the control of land and associated benefit streams in extensive pastoralist systems (Scoones Citation2021).

In Ilkisongo Maasai land, demarcation and enforcement of new boundaries associated with conservation and privatization has broadly restricted access to land and resources. However, attention to finer-scale changes in rules and norms of access to multiple resources, highlights complex, socially differentiated benefit pathways where explicit control over land is otherwise difficult to identify. A systematic understanding of the ways in which different households secure benefits from land – which we refer to as benefit pathways – provides a lens for understanding complex changes in land control and accumulation at multiple spatial scales, and highlights the interaction between direct benefits from land (e.g. farming, livestock) and new, indirect ways of benefiting from land (e.g. leasing for conservancies and mining).Footnote1 By mapping these benefit pathways, we trace explicit connections between socio-cultural change, livelihood differentiation, and uneven abilities to regulate the use of resources at multiple scales within collectively titled lands. By showing the relationship between multiple benefits from land, multiple dimensions of inclusion and exclusion from these benefits, and the social and political relationships that mediate this inclusion and exclusion, we elucidate diffuse processes of land control and accumulation.

In what follows, we first review intersecting bodies of literature on institutions, access, entitlements, and land control. We then present empirical findings alongside supporting literature to show how changes in rules and norms and other socio-ecological relations have shaped dynamics of accessing and benefiting from resources in Ilkisongo Maasai land. We then relate these changes to trends of social differentiation and new patterns of accumulation within land that was de jure recognized as collectively titled, but with complex de facto patterns of access and claiming. Finally, we discuss linkages between benefit pathways and livelihood outcomes, perceptions of collectively titled land, and processes of land control. We show how under shifting external influences, benefit pathways have become reconfigured along old and new lines of inclusion and exclusion according to authority, wealth, political affiliation, socio-cultural identity, and geographic location.

Pastoralism, institutions, entitlements, and access

Mobile pastoralism is a livelihood activity that is well-adapted to drylands (Behnke, Scoones, and Kerven Citation1993), in large part due to flexible, informal rules and norms of resource access that enable constant adjustment in response to spatio-temporal environmental variability (Niamir-Fuller Citation1999; Oba Citation2001). However, pastoralists’ practices of mobility and resource access have frequently been marginalized relative to other land uses, and pastoralists themselves often have limited political power within state governance structures (Turner Citation2017; Niamir-Fuller Citation1999; Waller Citation2012). Nation states have tended to refer to pastoralist areas as ‘underutilized’ or ‘degraded’ as a justification for economic, political, and wildlife conservation interventions (Bluwstein et al. Citation2018; Scoones et al. Citation2019), and for exerting control over populations, asserting legibility, and extracting value (Turner Citation2017; Waller Citation2012). This has led to a frequent lack of appropriate land tenure and wider political and economic support for pastoralist livelihood practices (Turner and Schlecht Citation2019), and to a perpetuation of narratives of ‘the death of pastoralism’ (Weldemichel and Lein Citation2019).

Common pool resource (CPR) studies have emphasized how pastoralist institutions mitigate risk associated with high variability of rainfall (Niamir-Fuller Citation1999), and examined the main factors driving the seeming paradox of pastoralists choosing to privatize collectively titled land (Mwangi Citation2007a; Lesorogol Citation2008). In Kenya, CPR analysts have contributed powerful arguments about how British colonial-era policies, along with those implemented by the Independent Kenyan state after 1963, undermined Maasai land management systems (Mwangi Citation2006, Citation2007a, Citation2007b; Mwangi and Ostrom Citation2009a, Citation2009b). However, persistent conceptual problems have limited CPR theory’s explanatory power in pastoralist contexts. In particular, CPR theory’s emphasis on clearly defined groups, with powers to exclude ‘outsiders’ enabling sustainable management of resources (Ostrom Citation1990), has not reflected the flexible, overlapping, and fluid social processes used by pastoral peoples to access spatio-temporally variable resources (Fernández-Giménez Citation2002 ; Turner Citation2011). Alternate conceptualizations have attempted to overcome these limitations through characterizing pastoralist resource governance as varying from ‘open property regimes’ that are regulated primarily through informal rules (Moritz Citation2016) to ‘complex mosaics’ involving a mixture of ‘open property’, 'common property', private, 'open access', and/or state regulated land (Robinson Citation2019). Additionally, given the inherent complexity of pastoralist systems of access and the importance of ‘bottom-up’ social processes, they also elude normative, managerial framings that focus on how the ‘fit’ of institutions determines the potential to regulate resource use (e.g. Cumming, Cumming, and Redman Citation2006; Epstein et al. Citation2015; Young and Gasser Citation2002). While a wide range of scholars have emphasized how natural resource institutions are fundamentally linked to social conflict, inequality, and asymmetries in decision making and authority (Agrawal Citation2003; Cleaver Citation2012; Kabeer Citation2000), CPR studies have generally tended to not view institutional configurations as constituted through socially differentiated processes (see Cote and Nightingale Citation2012; Cleaver and de Koning Citation2015). In contrast, ‘critical’ institutionalists have emphasized how institutions are produced through relational social processes that involve diverse economic, emotional, moral, and social motivations; asymmetrical power relations; and struggles over meaning (Bennett et al. Citation2018 ; Cleaver Citation2012; Cleaver and de Koning Citation2015; Cote and Nightingale Citation2012; Hall et al. Citation2014; Mehta et al. Citation1999; Whaley Citation2018 ). These scholars center how institutions tend to have complex origins (e.g. a mix of 'customary', colonial state, post-colonial state, and non-governmental); are influenced by a wide range of political, economic, historical, and discursive processes over time; and often represent powerful interests rather than those of 'communities' as a whole (Cleaver Citation2012; Hall et al. Citation2014; Leach, Mearns, and Scoones Citation1999; Mehta et al. Citation1999; Mosse Citation1997; Whaley Citation2018). This highlights the need for a relational understanding of property in legally plural contexts (Berry Citation1989), where rules and norms such as land access rights are dynamic, historically contingent, and contested, and reflect and (re)produce social difference and relations of inclusion and exclusion (Cleaver Citation2012; Kabeer Citation2000). These insights are particularly relevant in contexts of state-imposed collective tenure regimes, which may in ways resemble ‘commons’ (Ostrom Citation1990), but that have been prescriptively imposed and are inherently at odds with the ‘bottom-up’ regulatory concerns of CPR scholars (Berry Citation2018; Borras and Franco Citation2010; Li et al. Citation2010; Mwangi and Ostrom Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Peters Citation2004 ; Sikor, He, and Lestrelin Citation2017).

The conceptual frameworks of ‘access’ (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003) and ‘extended entitlements’ (Leach, Mearns, and Scoones Citation1999) have both greatly advanced understandings of rural livelihoods by expanding beyond frameworks that primarily focus on land tenure and rights. Analysis of access elucidates how property itself is a product of social relations, among others, and focuses on the ‘webs and bundles of powers’ that mediate the ability of different actors to access, and maintain access to resources, but also the ability to regulate, reorganize, and control the access of others in diverse contexts (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003). The closely related extended entitlements framework is more acutely focused on livelihoods, and explicitly addresses how households’ differential control over various social, economic, and material resources shapes their ability to gain benefits from multiple other resources (Leach, Mearns, and Scoones Citation1999). It expands Sen’s original (Citation1984) focus on legal rights, broadening this framing to emphasize how the ability of households or individuals to utilize and benefit from resources is mediated by interactions between endowments (i.e. assets) and diverse institutions, rather than by rights alone (Leach, Mearns, and Scoones Citation1999). An analysis of the interaction between the spectrum of a household’s endowments, and the institutions that shape their access to resources, can be used to ‘map’ the relative entitlements of households, and to assess the role that institutions play in mediating benefit streams from multiple resources (Leach, Mearns, and Scoones Citation1999). Studies of pastoralism drawing jointly from the frameworks of access (Moyo, Funk, and Pretzsch Citation2017) and extended entitlements (Goldman and Riosmena Citation2013; Unks et al. Citation2019) thus enable a fine-grained analysis of political, social, and economic relations that sustain and reconfigure institutions which mediate differentiated access and benefits to livelihoods from land across ‘complex mosaics’ of different property relations (Robinson Citation2019).

Land control in extensive pastoralist systems

New land uses, global political and economic forces, and local contestations have increasingly been characterized as producing ‘new frontiers of land control’, defined as ‘practices that fix or consolidate forms of access, claiming, and exclusion’ (Peluso and Lund Citation2011 pp. 668). Changing processes of access to and control of resources in pastoralist contexts is challenging to understand because of the heterogeneous and variable distribution of resources over time and space, overlapping webs of social relations, plural notions of property and rights, and diverse labor practices (Scoones Citation2021). Increasingly commodified labor and livestock, privatization of land and resources, and increasing social differentiation can indicate apparent shifts in these production systems (Bassett Citation2009; Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015; Scoones Citation2021). However, land control can also involve processes of local accumulation, for example through the commodification of resources (such as pasture and sand), which exacerbates socio-economic differentiation, modifies access, and can lead to new territorial assemblages (Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger Citation2015). Furthermore, attention to shifts in the logics of livestock production in response to changing political economic conditions, but embedded in distinct pastoralist socio-cultural systems, are important for understanding increasingly capitalist relations and new patterns of controlling land (Schareika, Brown, and Moritz Citation2021). Critical agrarian studies scholars have increasingly shown how land acquisitions and environmental governance reforms advocated by international actors are often facilitated by support from different state representatives, including local authorities, with important implications for local communities (Lanz, Gerber, and Haller Citation2018; Wolford et al. Citation2013). Those in positions of authority, such as local state representatives, are given new powers to reconfigure access and make claims within geographical boundaries (Peluso and Lund Citation2011), and serve as intermediaries to balance the interests of the state with local social relations (Lund Citation2016). However, they also frequently disproportionately promote the interests of new outside actors, and leverage local norms and practices of inclusion and exclusion along lines of identity to their advantage (Lund and Boone Citation2013; Lund Citation2016). These authorities acting as intermediaries can work to reconfigure land in ways that doesn’t constitute clear privatization, for example, within pastoralist communities in Kenya, where authorities have gained an uneven ability to modify institutions that mediate the access of others (Bergsalio and Cleaver Citation2018 ; German, Unks, and King Citation2017).

Throughout East Africa, complex patterns of sedentarization, increased reliance on grain-based diets, crop cultivation, markets, and other livelihood changes have exacerbated inequality and led to changing norms of mutual assistance among pastoralists (Fratkin and Roth Citation1990; Fratkin Citation2001; Little et al. Citation2001; McPeak and Little Citation2005; Potkanski Citation1999). In the context of land surrounding ANP, Ilkisongo Maasai elites have shaped access to resources within local communities as they negotiate new land uses with powerful outside interests such as cement manufacturers and wildlife conservation NGO representatives (Unks et al. Citation2021 ). Processes of inclusion and exclusion in access to resources and benefits from land along the lines of clan, age-set, and gender are also known to play a growing role in political divisions within communities (Southgate and Hulme Citation2000). These processes of inclusion and exclusion, along with wider changes in social relations and differentiated abilities to benefit from land, have important implications for processes of accumulation, but also for land control. In what follows, we illustrate a case study where we take a critical focus on shifting institutional configurations that mediate systems of accessing and benefiting from land, and show how new benefit streams, uneven processes of accumulation, and shifting authority, worked together to produce a new system of diffuse land control. In this case study, Ilkisongo Maasai authorities, in particular, were able to treat collectively titled land as private property, and this, coupled with their influence on social processes that mediated access and benefits, recursively reproduced local patterns of accumulation, socio-economic differentiation, and control over land.

Study area description and history

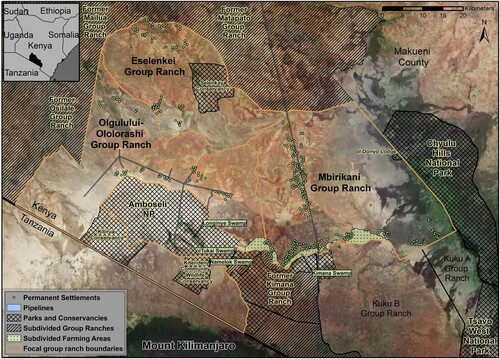

Our study focused on three GRs of the Ilkisongo Maasai section (Eselenkei, Olgulului–Ololorashi, Mbirikani), which are situated between the Chyulu Hills to the east, subdivided former GRs to the north and west, and Tanzania to the south (). The climate is semi-arid; the annual rainfall regime is bimodal, with rainy seasons typically occurring in March–May and November–December; and frequent droughts (Altmann et al. Citation2002).

A series of colonial and post-independence land appropriations, formalization of institutional configurations, and decreased political autonomy all restricted the flexibility of Maasai pastoralism in Kenya (Rutten Citation1992; Mwangi and Ostrom Citation2009a). The British colonial authority coerced the Maasai into signing a series of treaties that reduced their land by 50–70% and limited them to current day Kajiado and Narok counties (Hughes Citation2006; Reid Citation2012). Additional land was appropriated for private European ranches (Spear Citation1993), for game reserves under the national parks ordinance of 1945, and for privatized ranches claimed by Maasai authorities (Campbell Citation1993; Galaty Citation1992; Kituyi Citation1990). Within the land of the Ilkisongo section, Amboseli, along with the Chyulu Hills and Tsavo areas, were designated as national reserves in 1947–1948; and all were later gazetted as national parks following independence (Hughes Citation2006). Based upon pejorative assumptions about Maasai land use, a series of interventions were introduced by colonial authorities (and subsequently maintained by the postcolonial Kenyan state). These measures aimed to transform livestock husbandry practices into commercial production, undermine communal land management, encourage individualistic thinking, and promote cultivation of cash crops on settled land (Fratkin Citation2001; Rutten Citation2008; Waller Citation2012; Hemingway et al. Citation2022).

The colonial-era East African Royal Commission (Dow Commission of 1952) – along with the post-independence Lawrence Report – formed the policy basis for the establishment of GRs, beginning in 1968 with the Land Adjudication Act. GRs implemented collective land tenure, brought grazing management plans designed to reduce stocking rates and limit mobility, developed permanent water sources, and introduced measures to prevent livestock disease and promote commercialized livestock keeping (Campbell Citation1981; Grandin Citation1991; Mwangi Citation2007b; Rutten Citation2008; Waller Citation2012). Many GRs were not designed to reflect the need for seasonal access to ecologically variable resources, and those that did include seasonal forage and water access considerations did not account for required mobility during droughts (Campbell Citation1981; Coldham Citation1982; Rutten Citation1992; Rutten Citation2008; Waller Citation2012). Collective GR land tenure reconfigured access rights and undermined the socio-cultural basis of pastoralists’ mobile production strategies (Okoth-Ogendo Citation1986; Okoth-Ogendo Citation1989). As such, GRs constrained the flexibility of historical resource management institutions and social relations that previously mediated responses to ecological variability, leading to failure of collective management (Mwangi Citation2006; Citation2007a; Citation2007b; Mwangi and Ostrom Citation2009a, Citation2009b). In Kajiado, most GRs were soon subdivided into private parcels (Mwangi Citation2007a). This was motivated by a complex suite of factors including fears of appropriation of land by Maasai elites, non-Maasai, and the state, as well as deepening inequality within the GRs, national prioritization of crop cultivation and land privatization, and Maasai individuals use of land as collateral to obtain loans (Galaty Citation1992; Galaty Citation1994; Rutten Citation1992; Mwangi Citation2007a). Insecurity in land tenure, however, continued after subdivision due to GR representatives securing land for themselves and their relations, while many, especially women and youth, lost access to land and resources in the process (Galaty Citation1994; Mwangi Citation2007b; Rutten Citation1992). Highly unequal distributions of land parcels during subdivision, and land-grabs by non-Maasai politicians, have been common (Galaty Citation1994; Galaty Citation2013; Mwangi Citation2007b; Ntiati Citation2002; Rutten Citation1992; Waller Citation1976).

In the three GRs considered in this study, full subdivision had not yet occurred, but all had begun formal subdivision processes at the time of writing. Until the 1970s, GR land was primarily used for pastoralism, but competing land uses such as wildlife conservation, crop cultivation, and extractive industries had steadily increased (Campbell et al. Citation2000; Campbell et al. Citation2005; Roque de Pinho Citation2009; Southgate and Hulme Citation1996). Since 1977, Ilkisongo Maasai dry-season settlement within ANP, a key dry-season source of forage and water, had been restricted (Campbell Citation1981). Widespread farming began in wetlands in response to drought and livestock loss following this prohibition (Campbell Citation1981; Campbell et al. Citation2000; Campbell et al. Citation2005). There was increased demand to produce cash crops for urban markets, to extract sand from seasonal river channels for urban construction, and to dedicate land to wildlife conservation (BurnSilver Citation2009; Campbell et al. Citation2005). Partial subdivision of land, while not officially recognized, had previously occurred in all three GRs within high-productivity swamps that were designated for drainage and cultivation in Olgulului–Ololorashi in the 1970s, and in Mbirikani in the early 2000s (BurnSilver and Mwangi Citation2007; BurnSilver, Worden, and Boone Citation2008; Southgate and Hulme Citation2000). Other areas were also subdivided for trade centers and towns, or designated for the construction of ecotourism lodges. Drier upland areas remained primarily used for livestock herding. Livestock populations had fluctuated over time with variability in rainfall, but as the Maasai population had increased, per capita livestock numbers had declined, relative numbers of small stock had increased, and household diets had become increasing dependent on grains (BurnSilver, Worden, and Boone Citation2008; Grandin Citation1991; Nkedianye et al. Citation2020). Maasai livelihoods continued to depend heavily on livestock but increasingly relied on cultivating crops, waged labor, and trade (BurnSilver Citation2009; Hemingway et al. Citation2022), with lower numbers of livestock among completely sedentarized households (Kimiti et al. Citation2018).

So-called 'community-based conservation' (CBC) projects had gained prominence in GRs surrounding ANP. Wildlife exploited water and forage within swamps inside the park during the dry season, but typically moved to areas with more nutritious forage outside of the park during the rainy season. A number of wildlife conservation NGOs were active within these GRs, and monetary income to GRs from these activities occurred primarily through: (1) ecotourism lodges leasing parcels of land as conservancies, with direct payments to GR representatives, intended to provide water infrastructure, education, and medical facilities (Campbell Citation1999; Rutten Citation2002); (2) leasing of subdivided lands from communities, bundled together as ‘group conservancies’, where individual payments were made to each individual title holder; (3) compensation schemes that offer payments when livestock are lost to predators (Okello, Bonham, and Hill Citation2014); (4) jobs as wildlife rangers and scouts on all three GRs; and (5) educational bursaries provided by NGOs and Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS). The overall monetary incomes produced from conservation had been reported to be small on all three GRs (BurnSilver Citation2009; Rutten Citation2002; Western Citation1994) and also unevenly distributed among households and across GRs (Groom and Harris Citation2008; Roque de Pinho Citation2009). Very few tourist operators were from the communities, and the returns from leased lands were largely under the command of Maasai authorities and elites (BurnSilver Citation2009; Campbell et al. Citation2000; Roque de Pinho Citation2009; Rutten Citation2002; Western Citation1994).

Methods

The following analysis is based upon eleven aggregate months of field work by the first author. Participant observation and ninety-eight interviews (sampling stratified by age, gender, clan, wealth, and livelihood practices) were conducted across the three different GRs (Olgulului–Ololorashi, Eselenkei, Mbirikani). Interviews were limited to GR residents of Maasai ethnicity to focus on understanding their views of collectively titled land.Footnote2 Interviews were conducted primarily in Maa and translated into English by a translator, with several also in Kiswahili or English. Interviews were conducted under informed consent and recorded only if additional consent was granted. Interviews followed a semi-structured format, with a subset of questions replicated in each interview that allowed for responses to be coded and quantified across interviews. Themes addressed in the interview questions included:

Changes in informal and formal rules or norms that mediated livelihood practices (e.g. changes in land tenure, land use, access relations, authority structures, and mutual assistance).

How the above changes in institutions related to the ways individuals have adjusted their livelihood practices.

Views of collective land management.

In order to challenge preliminary interpretations, the first author reported study findings at eight public meetings in locations where interviews were completed. All residents were invited and encouraged to critically discuss study findings (noted in the text when referenced). Below we first report findings on changes in institutions alongside key literature on past institutional configurations. We follow this with an analysis of differential access and entitlements as shaped by institutions in this dynamic context. We then relate overlapping changes in benefits from land to changing views of collective land governance.

Changes in institutions mediating herding access

In addition to restrictions in access to vital dry season resources, a number of other shifts in rules and norms had limited Maasai herding practices in the study area over time. Though Maasai historically practiced transhumant pastoralism, multiple practices were used by colonial and post-colonial governments to coerce sedentarization. Colonial-government-appointed Maasai ‘chiefs’ (see Waller Citation1976; Hughes Citation2006) played central historical roles in the formation of permanent settlements (emparnat) intended to sedentarize families near boreholes, pipeline junctures, and other water access points, and to institute grazing management plans focused near these settlements (BurnSilver, Worden, and Boone Citation2008; BurnSilver Citation2009; Fratkin Citation2001) (). Sections (olosho, pl.: iloshon) are the largest geographic divisions within Maasai territory and represent distinct socio-linguistic groups. Rules implemented by chiefs further divided these into imurrua,Footnote3 i.e. areas that contain permanent settlements as well as dry- and wet-season grazing areas. Historically, access to these areas was open to other groups, and numerous male and female interlocutors over ∼50 years of age (hereafter: male and female elders), told us that before GR formation, movements between areas that came to be designated as imurrua and GRs were common. For example, people who lived in areas situated within Olgulului–Ololorashi GR formerly regularly moved to areas currently within Mbirikani GR during the beginning of the short rainy season (oloorkisirat), and those living within Mbirikani GR moved to areas within Olgulului-Ololorashi during the beginning of the long rainy season (inkokua). These movements with livestock across GR boundaries over time became much less common, and were actively prevented by chiefs aside from in a few localities with permanent settlements near to GR boundaries. Subdivision had also occurred to the south within the Ilkisongo section (i.e. Kimana south to Oloitokitok), and to the north and west in the Ilkaputei and Matapato sections, constraining movement to these areas in the recent past (). Many interlocutors told us that they still sometimes moved to these lands within subdivided areas, but that it required a relationship (e.g. agnate, affine, or stock partner), and increasingly, a rental agreement; as one male elder remarked: ‘before they used to move freely, now even your friend asks you for something’ (see also BurnSilver and Mwangi Citation2007).

At the time of the study, within GRs, movements with livestock between imurrua had also become increasingly limited, but access was sometimes granted to outsiders under drought conditions. Movement across these numerous boundaries required permission from chiefs, GR committees, and members of an imurrua, with denial being common. As one male elder commented, they were sometimes told to ‘return to your place, you are here because you didn’t save your grass'. Movement was also sometimes discouraged by access to water being limited or charged for. Importantly, both imurrua and water point access were sometimes, but not always, limited by clan affiliation. Although each GR considered here contains a mix of clans (engilat) and sub-clans, GRs were allocated along lines of clan, and were sometimes dominated by one group, to the exclusion of others. Rivalries were particularly strong between three clans: the ilaitayok and ilaiser, who are both clans within the orokiteng’ moiety; and ilmolelian, a clan of the odomong’i moiety. Each imurrua tended to be dominated by one of these groups. Farming had also limited livestock access within GRs to perennial, spring-fed, swamp areas that formerly were heavily relied upon during drought, but which had been privatized, drained, and converted to farms. Finally, leased areas within GRs that have become conservancies () had restricted grazing access, despite sometimes allowing grazing during droughts, albeit only after other reserve areas had been exhausted, and no overnight cattle enclosures were permitted within them (see also Rutten Citation2002).

Changes in norms of mutual assistance

Changes in mutual assistance had created additional limitations on mobility. Two common types of mutual assistance: individual and clan-based, are core features of Maasai social organization (Galaty Citation1981; Grandin Citation1991; Potkanski Citation1999). Individual assistance through food and livestock occurs between patrilineal and affinal bonds as well as between close friends that share age-set bonds formed among the ilmurran (typically unmarried males initiated into an age-set through circumcision and charged with security and cattle herding) (Galaty Citation1981; Grandin Citation1991; Potkanski Citation1999). Clan-based assistance is distinct from individual assistance, and can take the form of multiple clan members contributing livestock for various purposes, e.g. bride-price, fines, or following loss of livestock (see Galaty Citation1981; and Potkanski Citation1999 for detailed discussions). These agnate, affine, clan, and friendship bonds are the basis of numerous important relationships that also facilitate securing seasonal grazing access across different spatial scales (Homewood and Rodgers Citation1991).

Among the Ilkisongo, mutual assistance through kinship and other extended social networks beyond immediate family had decreased with the increasing influence of livestock markets, cultivation practices, and employment (Campbell Citation1999), as also noted among Maasai in other sections (Galaty Citation1981; Potkanski Citation1999). Ilkisongo female elders in particular tended to emphasize that mutual assistance was becoming increasingly localized within imurrua, and isolated by family, age-set, and clan, especially among men. Many male and female elders described these changes in behavior as symptomatic of wider changes in norms, including overall decreases in respect (enkanyit). However, some, also usually female elders, disagreed that mutual assistance had decreased, sometimes even claiming that, overall, group-level unity (naibosho) had increased and that new types of assistance had become more important than individual mutual assistance (osotua) – especially with a recent proliferation of new norms around church and women’s groups that encouraged pooling of resources, income, and labor support.

These socio-cultural changes were frequently discussed as being closely related to decreases in shared herding labor. Whereas in the past numerous neighboring households would combine their herds and household labor, especially during the dry season where mobility and herd splitting were most important (see also Sperling and Galaty Citation1990), it was increasingly common for individual households to herd their own livestock. However, some emphasized that those without paid herders would sometimes still combine their herds, and herd in shifts, especially when accessing dry-season grazing areas and the national parks during droughts. Some related these decreases in shared herding labor to changes in joint herding and food-sharing inkangitie (singular.: enkang; residential compounds of several nuclear families, often of patrilineal descent) (Grandin Citation1991), as combining herds and sharing labor primarily occurred within these inkangitie, or between family and close friends. While inkangitie historically usually contained dozens of households that herded collectively, their physical sizes and the number of people sharing inkangitie, have both diminished on average (see also BurnSilver, Worden, and Boone Citation2008; Archambault Citation2016). In explaining these changing relations, male and female elders regularly emphasized the role of rising inequality, with decreasing mutual assistance between people from different levels of wealth, divergent individual preferences for specific livestock husbandry or housing practices, and also underlying changes in religion and formal education (see also Borona Citation2020).

Increases in older women and men herding, and young girls and boys herding only when not in school were also prominent, and male and female elders usually explained the increasing prevalence of children attending Kenyan schools as another key factor underlying changes in shared labor. Since the colonial era there have been government attempts to weaken the social bonds of ilmurran through forced school attendance (Knowles and Collett Citation1989; Kituyi Citation1990; Zaal Citation1999). Historically, Maasai often fought such pressures, and resisted sending their children to school. This had changed, however, with many people, especially elder women, associating school attendance with higher social status. However, male and female elders typically told us that changes in livestock husbandry were also related to education in three ways: (1) the quality of practices of care of cattle, especially regarding mobility and protection from predators, had deteriorated with ilmurran regularly attending school; (2) the need to pay for hired herders or to resort to alternative arrangements had increased; and (3) sales of livestock to pay school fees had increased. Although some ilmurran refused to attend school, and some families could not afford school, young males from wealthier families nonetheless nearly always went to school, as one wealthy male elder commented, ‘I will not allow my children to herd’. In turn, however, the families of ilmurran that were not enrolled in school and that were available to herd cattle had increasingly expected compensation from families they assisted.

A number of other inter-related changes in social relations also had important implications for mutual assistance, particularly changes in authority structures, decision-making processes, and clan and age-set politics. The creation of GRs imposed a new structure of authority, where elected or appointed representatives gained the power to make decisions on behalf of GR members about land use (Mwangi and Ostrom Citation2009b ). Government-appointed Maasai ‘chiefs’, GR representatives, and politicians have in general, gained exclusive access to, and disproportionate benefits from, land, with sweeping implications for mutual assistance and concepts of ownership (Campbell Citation1993; Campbell et al. Citation2005; Galaty Citation1981). There had also been an increased salience of interactions between Maasai and conservation NGO representatives, where employees and GR representatives were perceived as disproportionately benefiting financially from wildlife conservation activities, and also forming new patron/client relationships with NGO representatives (Unks et al. Citation2021). While there have been long-standing tensions between adjacent age-sets as they have grappled over power and roles, men from younger age-sets have gained historically unprecedented power by occupying formal GR authority positions that enabled enhanced relationships of patronage with national political actors and that undermined the authority of male elders (Campbell Citation1999; Southgate and Hulme Citation2000). These tensions have been raising across Maasai areas (for discussion of this in Tanzania, see Goldman Citation2020, and Hodgson Citation2011). Finally, competition between clans, and clan-based alliances with national politicians, had also reconcentrated flows of patronage, which had been detrimental to other forms of mutual assistance relations (Southgate and Hulme Citation2000).

Differentiated access to grazing resources during drought

At the time of study, there were few locations that could be accessed with livestock outside of GRs, and access to these places was highly socially stratified. During the drought of 2016–2017, once forage within GRs was exhausted, reliable grazing access was secured by some on subdivided, privately titled lands through social relations (e.g. family, friends, or people in positions of influence that did so on promise of future favors), but also through payments. Several herders said they had traveled to Tanzania or other distant places in search of grazing. The most common destinations at this time were Chyulu Hills National Park (CHNP), Tsavo West National Park (TWNP), ANP, and neighboring subdivided GRs. Because pipelines no longer provided water to some permanent settlements, herders were legally able to access water in the swamps inside ANP – as per agreements made following exclusion from having settlements within ANP. Access to the swamps was permitted for four hours a day, and only in areas where livestock could be out of sight of tourists. During droughts, however, some herders took the risk of overstaying this time because grass within ANP was the only available aside from that in private land, TWNP, or CHNP. Taking this risk to sustain cattle was only possible for those with sufficient herding labor because this enabled them to avoid KWS guards (who they said were likely to drive livestock away or beat herders, if encountered). While formally not permitted to access, some also entered TWNP and CHNP, where access was sometimes negotiated by bribe. If caught by guards, however, and negotiation was impossible, they said that livestock were driven into remote areas and lost to predators, and herders fined, beaten, or jailed.

According to male and female elders, in the past, dry season watering points were key determinants of where households temporarily settled during different seasons. However, patterns of restriction, locations of designated watering points, and settlement areas, and the ability to transport water, had transformed these patterns. In particular, the ability to use a vehicle to transport animals, water, and grain to supplement livestock had become extremely important during drought. As a result, some were able to disproportionately exploit distant grazing areas that were formerly limited to times when water was available in seasonal ponds. Although some interlocutors claimed that water carried by truck was equally available to all, others indicated that individuals with trucks who provided water would prioritize assistance to those with close relations (e.g. kinship, clan- and sub-clanship, neighbors). Further, use of supplemental feed such as grain, bailed grass, and crop residues during drought was a recent practice that became widespread in the area in 2016–2017. As one male elder remarked ‘we are feeding them like people now’ (see also Goldman and Riosmena Citation2013). Those who had greater access to these assets and a means of transporting them, along with water, were able to reach areas far from homesteads and watering points, where the forage had been grazed less. Those with these assets were thus able to remain within dry season grazing zones, to graze farther into distant areas, and to reduce walking strain on animals. Male and female elders both frequently said these changes were leading to deepening inequality compared to the recent past when everyone grazed in the same direction and traveled the same distance from settlements.

Market interactions, and ability to gain cash assets that shape mobility and farming

Overall, Ilkisongo Maasai had been increasingly engaging with livestock and crop markets in nearby town centers to meet growing needs for cash (e.g. livestock-related costs, livestock purchases, school fees, transportation, medical expenses, and family food). This had been facilitated by market demands in Nairobi, and recently constructed paved roads (see also Campbell Citation1999). However, because of price fluctuations in these markets, being able to sell livestock strategically when market prices are high had gained increasing priority. A sizeable herd, secondary income, or alternate source of food were regularly emphasized by interlocutors as being crucial for reducing the impact of herd offtake, especially to avoid sales when market prices were low – such as during times when school fees were due or during drought. Indeed, many indicated that their herd sizes had decreased primarily through necessary sales at extremely low prices, rather than due to animal mortality during the 2016–2017 drought.

Many noted that they had been motivated to increasingly adopt ‘improved’ breeds of livestock (e.g. Sahiwal cattle, Dorper sheep, see also BurnSilver, Worden, and Boone Citation2008) by the higher market prices of these animals, despite the majority stating that they consumed more forage, could not walk long distances, required more intensive herding practices, and were more likely to die during drought. However, those with larger herds, and livestock brokers, who in both cases frequently bought and sold cattle locally and transported them to markets, explained how they were able to utilize the market to their advantage (see also Evangelou Citation1984 ; Zaal Citation1999). These individuals shared their extensive knowledge of prices at different markets throughout the Amboseli basin according to livestock breeds, animal health conditions, and different purposes (e.g. milking cows, breeding bulls, castrated steers for meat, etc.). Traders, in particular, also usually had other sources of income and were able to profit from buying and reselling (often strategically, under favorable market conditions) animals that others could not because they lacked the labor force or time to transport them to markets.

Farming strategies were similarly differentiated, with some focusing on cash crops, some on subsistence farming, and others leasing their informally titled land, usually for very low returns. Those cultivating for subsistence tended to grow maize or beans for family consumption, storage, or local sale in small quantities, with maize in particular having relatively low input costs and being easier to maintain. Growing tomatoes as a cash crop involved prohibitive costs for many (e.g. digging wells, plowing land, purchasing generators, pipes, chemicals, and seeds) and high amounts of financial risk due to fluctuating market costs and loss from pests and wildlife (see also Hemingway et al. Citation2022). The majority of cash-crop farms in many areas were leased to, or cultivated in partnership with non-Maasai, who often took responsibility for labor and for deterring wildlife from foraging in plots. These plots were primarily located within former (drained) swamps, but also in locations near pipelines in Mbirikani GR, and in close proximity to the Eselengei River (). While most said that there was not a bias in how plots were allocated amongst clans, they were more likely to say that plot distribution was skewed in terms of quality toward the wealthy and/or GR representatives. Soil type, plot size, elevation relative to the water distribution furrow, distance to the river or pipeline, and distance to main transit corridors all impacted the farm’s viability. Depending on location, bribes allowed some to influence the amount and timing of water in irrigation furrows, or to access pipeline water. In locations without furrows or pipelines, farming was largely limited by ability to hand dig wells or pay for a private borehole. Cash was also required to pay for purchasing or renting, maintaining, and fueling water pumps. High cost chemical fertilizer and pesticide reliance had also increased conspicuously, especially for growing tomatoes, and experienced tomato farmers tended to stress the high susceptibility of these crops to pests.

Changing ecological stressors and differentiated abilities to benefit from mobility

Male and female elders explained how the above changes in mobility, social relations, and cash incomes were also interacting in new ways with three key ecological factors: livestock disease, changing wildlife behavior, and changing rainfall patterns. They indicated that several livestock diseases had increased in recent memory, requiring more frequent use of antibiotics and acaricides, and that ‘improved’ livestock breeds were more sensitive to some of these diseases. Many explained that livestock that visited CHNP and TWNP were exposed to East Coast Fever (oltikana) and trypanosomiasis (engoroto), and so migrating there required a source of cash for preventative disease treatment. Numerous interlocutors also explained that predators such as lions and hyenas feared people less today (see also Goldman, de Pinho, and Perry Citation2013; Unks et al. Citation2021) and so were a greater threat to livestock, especially when using dry-season grazing areas, an issue that was compounded when labor to defend the livestock from predators was lacking. Male and female elders told us, nearly unanimously, that seasonal rains had become less predictable (e.g. more frequently failing, or arriving later than usually expected) since the late 1990s. They also commonly added that the impact of changes in rainfall had exacerbated the lack of open areas to move to, with many male and female elders repeating the phrase ‘everywhere is now occupied’.

Many told us that the 2016–2017 drought was the first time in their experience that grass had not been available anywhere (aside from the parks and private lands), and that 2016–2017 was the first time they had not migrated during a drought. Most explained that their decision to not migrate was related to recent experiences, such as during the 2009 drought, and they recounted that they had lost large amounts of livestock, had difficulties finding water, and had negative interactions with park rangers. Those who chose not to migrate also sometimes elaborated and said that those who had remained within their GRs had lost less livestock than them in 2009, or that personal risks, increased risks of predation and disease, labor and asset limitations, the new strategy of feeding grains to livestock, and/or prevalence of less mobile livestock breeds, had influenced their decisions to remain within GRs. Some also concluded that they had lost fewer animals by remaining within their GRs in 2016–2017 compared to those who moved. However, others attributed their changing assessment of mobility primarily to decreases in cattle numbers, and some from these households with few livestock said they were able to sustain them through the drought by grazing within high-productivity private farm plots in former swamps.

A range of strategies were taken across households to sustain livestock in the 2016–2017 drought. The characteristics of households' different strategies were usually described to us as associated with differentiated abilities to access and benefit from different resources. Most emphasized that herding labor was a key determinant of their relative mobility. Herding labor varied greatly among families, and most considered ilmurran labor in particular to be essential for maintaining and protecting cattle in remote areas with high numbers of predators. Another commonly mentioned asset was multiple enkang locations, which many told us both enhanced herders' access rights across GR or imurrua boundaries, and also reduced labor constraints because it enabled splitting of labor and herds between locations (e.g. it facilitated tending to milking cows and nursing or weak livestock within permanent settlements while the remainder of the herd was mobile). Furthermore, some said that those that had one enkang in farming areas, in addition to others in locations more conducive to the needs of livestock, had an optimal arrangement.

Having a source of income in addition to farming and livestock also enabled some households to enhance their ability to benefit from livestock and farming (as also reported by Campbell Citation1999). These sources of cash usually came from family members employed in Nairobi, working in eco-lodges or as tour guides, as scouts or guards in conservation organizations, or in cement manufacturing. Temporary employment incomes were also common, with some women working to harvest cash crops, and some men working to mine sand or driving motorcycle taxis. Others managed businesses such as general stores, restaurants, bars, hair salons, butcheries, or rental houses. Furthermore, many stated that their livestock- and farming-related sales and costs were closely interrelated, and often complementary, e.g. selling livestock to invest in farming, and then reinvesting proceeds from farming into livestock. Some with higher cash assets were able to invest in feed during the drought, with some even able to buy stocks of feed to sell to others for a profit. Some pointed to important differences in quality of feeds, and stressed that lower price feeds sometimes contained additives (such as sawdust) that were harmful to livestock and had sometimes caused their death during the drought. Those with greater cash assets were also more likely to buy and transport water, more able to pay for labor and for grazing fees in subdivided areas, to pay fines and/or bribes when moving, and to pay for transport of weak animals. They were also better able to buffer herd losses from predation, disease, and starvation during the drought. One striking example of the interrelation of these multiple assets was a prominent county-level politician and absentee pastoralist, who reportedly did not lose any of his herd of ∼500 cattle. In contrast, others who lacked assets such as additional income, adequate labor, supplemental feeds, transport capabilities, and paid grazing access, said they were heavily impacted by the drought and by other interacting stressors such as markets, livestock diseases, and wildlife predation. Similar outcomes were described surrounding farming, where those with cash assets to pay for bribes to furrow and pipeline managers, to cover the costs of pumping water from rivers or wells, and to pay for chemical inputs and seeds tended to report more beneficial outcomes from farming. Many, however, also viewed farming cash crops as enabling them to be less sensitive to drought and also enabling them to support livestock, and to reduce sensitivity to offtake by waiting to sell livestock until market prices had risen. This showed similarity to other contexts in the region, where the ability to invest in and benefit from cash crops (Little et al. Citation2001) has been shown to be closely related to differentiation in mobility, market interactions, non-livestock sources of income, and the structure of risk (Lesorogol Citation2008; McPeak and Barrett Citation2001).

The politics of access and benefit pathways

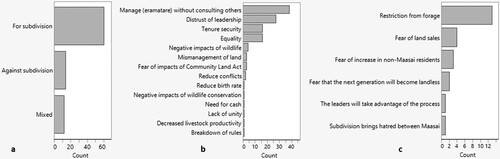

Though numerous factors had spurred the process of subdivision underway at the time of writing (see Unks Citation2022), to understand how individuals viewed the overall structure of access and benefits, we explicitly asked about their views on subdivision of GRs, which we then related to wider views of collective land tenure and management. Though in a minority, some expressed fears about subdivision. Of those fully against subdivision or with mixed views of it ((a)), the fears that they expressed most commonly concerned loss of access to livestock forage, and to a lesser extent, a mixture of concerns over widespread sales, and/or loss otherwise, of lands, unequal distribution of land in the subdivision process, fears of people from other ethnic groups moving onto Maasai land, and increased ‘hatred’ among MaasaiFootnote4 ((c)).

Figure 2. Views of subdivision in three group ranches. (a) Support of subdivision; (b) reasons motivating supporters of subdivision; (c) reasons to not subdivide.

The overwhelming majority indicated that subdivision would be a favorable change ((a)). The most common motivator they listed was a desire to manage their household activities and land (eramatare) without consulting others, which was also usually described as closely related to desires for individual tenure security, which was the third most commonly referenced motivatorFootnote5 ((b)). Both of these motivators were often explained as enabling conditions to build permanent homes, drill boreholes, and dig private water reservoirs. The second most common reason for supporting subdivision was mistrust of GR representatives ((b)). Though many maintained public respect for representatives through public narratives of respect (enkanyit), unity (naibosho), and mutual assistance (osotua) – all of which are paramount for Maasai – they often expressed deep seated reservations about representatives in these private interviews.

Indeed, it was a common sentiment in all GRs that the three primary representatives (chairman, secretary, treasurer) were involved in financial mismanagement, were the main beneficiaries of new land use projects, and did not make decisions on GR members’ behalves. In particular, GR representatives’ decisions about leasing land to outsiders, fears about their ability to make decisions about land in the future, and unequal distribution of financial benefits from projects they had arranged were frequently stated to be the source of this distrust. As one male elder remarked ‘they realized even if they didn’t subdivide that it would be sold … ; someone might come with a new idea for a conservancy and so we decided to subdivide'). There were widespread views that representatives were ‘eating’ land everywhere and that they were ‘selling without consulting’. This applied to leasing of land to the Simba Cement Company on Mbirikani GR, sand mining agreements on Eselenkei GR, and wildlife conservation agreements on all three GRs, where the conditions of payments, and decisions about the use of these funds, were often conducted in private among GR committee members. Members of Eselenkei GR frequently described the negotiations and agreements with respect to Selenkay Conservancy () as lacking transparency and primarily benefiting GR representatives through their ability to control funds from entry fees, bed night fees, and other incomes intended for use by the GRs as a whole. Many members of Olgulului–Ololorashi GR, where subdivided plots were bundled together and leased as Kitenden Community Wildlife Conservancy to a conservation organization (), said that they had not been informed of the contents of the agreement and suspected that a public meeting had been manipulated by representatives to make it appear to NGO representatives that GR members had reached a consensus about leasing the land. Many also stated that processes of plot allocation in local town centers had foregone public discussion about surveying processes and fees, and that no documents from surveyors had been made available to them.

Others expressing support for subdivision saw it as a way of making the benefits gained from livestock more equitable, sometimes explaining that it would enable them to lease land to those with greater livestock, or negotiate more profitable conservancy leases (‘equality’, (b)). These were also often related to the way that ‘chiefs’, GR representatives, politicians, Ilkisongo NGO employees, and their extended families had accumulated assets derived from leasing land, from wildlife that broadly used collective land, and that enabled them to enhance the benefits derived from farming and livestock. Some also emphasized a widening social divide between lower and higher wealth families, politicians, and representatives. This was related through examples of elites not adhering to grazing rules (e.g. GR representatives and influential county government officials whose herds utilized dry season grazing areas at times others were restricted). GR representatives were also frequently described as being heavily influenced in their decisions about land by patron/client relationships, especially those with higher level national politicians.

The four most prevalent reasons for supporting subdivision (distrust, managing without consultation, tenure security, and concern for equality) were often explained as closely related to one another, and all were tied to direct and indirect benefits from land such as farm plot allocation, water access, bursaries, cash payments from GR officials for medical or ceremonial purposes, grazing access, employment, and predation compensation. In order to understand the complexity of these interrelations and how they impacted households along lines of social difference, we next briefly summarize how clan, age-set, wealth, political party, and gender were explained to us as interacting and forming axes of a constantly evolving relational system of inclusion and exclusion.

While some stated that clan politics had decreased in terms of limited water rationing and grazing movements (see also Southgate and Hulme Citation2000), a majority indicated that the influence of clan politics had increased surrounding elections, job selection for wildlife conservation, and distribution of indirect benefits from land. Importantly, bribes and distribution of benefits among clan members, and members of allied clans, were vital for GR representatives to build and sustain support among clan leaders. Many also stated that national political alliances increasingly influenced election outcomes, with national politicians being able to determine who was nominated, to sway elections, and create day-to-day barriers for elected committee members who choose not to support them (see also Kibugi Citation2008). Many said age-set politics had gained an increasing influence, for example in Eselenkei where four representatives are from the younger (Irkiponi) age-set and were widely seen as challenging representatives from older age-sets (i.e. Ilkeleyani and Ilkishumu). Through participant observation, we also documented that different subgroups (e.g. clan, age-set, and political alliances) strategized to push specific agendas in public meetings, especially in terms of employment in wildlife conservation and sand mining, plot allocation, or other income benefits that representatives had influence over. We also observed that while GR representatives commonly engaged in public deliberation, as has been the norm historically, they also engaged in frequent private meetings with outside actors (e.g. wildlife conservation NGO representatives, businesspeople, politicians, surveyors). These all likely contributed to perceptions that GR representatives have made decisions that primarily suited the interests of their extended families, and their clan and political allies.

As also noted by others, Maasai women are often excluded from formal decision-making processes regarding land and finances, yet share an increasing burden of herding and farm labor (Wangui Citation2008; see also Yurco Citation2018). In our study area, women frequently emphasized that they were not typically employed by sand mining or conservation projects. Neither did they regularly participate in the leasing of GR land, or attend meetings about land uses, GR finances, or meetings with external actors. As a result, distrust of GR representatives was especially common among women. However, at the same time these patterns of exclusion and distrust highlight the central role that Ilkisongo Maasai women were playing in envisioning new ways of sharing land and exploring possibilities for more even distributions of benefits, and how these might be bolstered by subdividing land. Despite on-going processes of exclusion, women had an increasing influence at household, as well as imurrua-level decisions, because of their increasing ability to control cash through farming labor and other jobs, to advocate for the education of children, to create new practices of mutual support through women’s groups and church groups, to speak during some meetings, and increasingly, to generate political pressures through social mobilization. While women continued to be excluded from most formal positions of authority, they were organizing to advocate for new relations and decision-making processes surrounding land use (see also Archambault Citation2016), contesting decisions about land use made by GR committees composed exclusively of men, contesting the alliance-building practices of authorities across political levels, and fostering new types of alliances intended to counter-act political and clan divisions among elder men. Women were also creating new alliances with ilmurran from the youngest (ilnyankulo) age-set, who were also excluded from decision-making processes (see also Goldman, Davis, and Little Citation2016). One conflict on Mbirikani GR in particular was frequently referenced, where the ilmurran and women jointly contested an arrangement made by GR representatives for sand mining, leading to a conflict claiming the lives of one olmurrani and a police officer. References to this, and other similar public contestations, were often described as closely linked to wider mobilizations by women to negotiate the norms of sharing and benefiting from land.

Discussion

Here we explore the patterns presented above and discuss the ways in which socially differentiated pathways of benefiting from collectively titled land are intertwined with the changing political, social, economic, and ecological context of Ilkisongo Maasai land, and how new diffuse patterns of land control closely relate to both surplus accumulation and social patterns of inclusion and exclusion that have emerged. Key drivers of institutional changes during the colonial, post-colonial, and more recent NGO-led wildlife conservation eras,Footnote6 which have all shaped access to resources, can be grouped as follows:

State interventions, land appropriations, and collective tenure arrangements (GRs);

Changes in land use designations and access rules due to GR governance, subdivision of neighboring GRs, and internal wildlife conservation policies;

Benefit streams from cash cropping and wildlife conservation;

Social changes that emphasize increasingly individualized practices and changing alliances;

Market and technological changes that impact livelihood-based benefits from land;

The ability of local authorities to modify the access of others to land, and to treat collectively titled land as private property;

Reconfiguration of patterns of mutual assistance to increasingly focus on specific relations (e.g. external political actors, NGO representatives, clans), leading to new patterns of inclusion and exclusion from indirect benefits of land.

The relationship between access and benefits from land

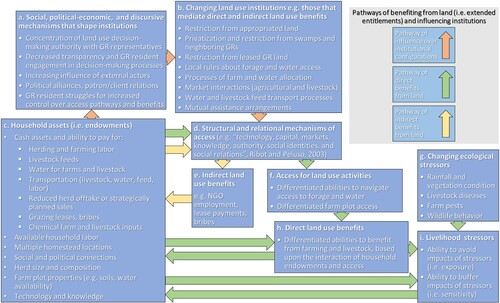

The drivers listed above produced a number of institutional changes ((b)) that shaped patterns of differentiated access ((d)), which in part mediated differential household abilities to benefit from land ((f)). Due to a suite of changes in mobility, markets, and social relations, accumulation of livestock required an array of new assets that distinguished it from historical pastoralist practice ((c)). Below, we emphasize four key ways that the institutional basis of access interacted with these household assets to shape direct benefits from land ((h)).

Figure 3. Key factors shaping benefit streams and control of collectively titled group ranch land. Boxes e and h specify benefits associated with the distinction of ‘direct use rights’ and ‘indirect use rights’ over land made by Sikor, He, and Lestrelin (Citation2017).

Firstly, access to forage was dependent on individual household endowments, and was mediated by institutional changes at multiple scales. Access to forage outside of GRs during times of scarcity was differentially limited by cash assets and ability to pay for grazing lease fees, labor, bribes, medicine, and water. As forage outside of GRs was primarily within protected or privatized areas, this access was also mediated by social relations that formed the basis of arrangements to access (illicit and otherwise). While all had de jure and de facto access to dry-season grazing within GRs, access to these areas was also heavily influenced by individual households’ abilities to provide water and supplemental feeds to livestock and to transport livestock, and thus was highly socially stratified, according to household cash assets, technology (e.g. veterinary supplies, vehicles), and social relations. Further, the ability to sustain cattle through mobility within and outside of GRs to avoid exposure, and other measures to decrease sensitivity to ecological stressors such as disease and wildlife ((i)) rested on household assets that were supplemented by assets gained from farming or other household income ((g)). In other words, the ability to benefit from land was not just about access, but was also tied to a wider set of household endowments and interrelated abilities to benefit from multiple resources (i.e. one’s extended entitlements set). Changes in required entitlement sets, in turn shaped the highly differentiated decision making of households in response to social and ecological uncertainty and impacted how livelihood stressors were experienced.

Secondly, institutional changes in social norms of mutual assistance led to increasingly individualized responses to uncertainty. This placed heightened importance on individual household assets (i.e. endowments), which shaped abilities to benefit (i.e. entitlements), and deepened social differentiation in abilities to adjust to ecological variability and new constraints on mobility. Changes in shared labor and resources among households were linked to long-term social changes due to multiple factors. These included historical interventions to end ilmurran practices (see Kituyi Citation1990) and national reforms in Kenya that shifted the burden of education and social services onto households (Galaty Citation2013). These had salient, cascading impacts on families who lacked household labor and/or the financial assets to hire labor needed to sustain livestock during droughts, with important gendered implications. Changing social alliances along lines of wealth, political affiliation, clans, age-sets, and gender, and between a subset of Maasai and wildlife conservation NGO representatives also reconfigured patterns of mutual assistance. Further, the ability to gain cash assets through employment, and through other indirect benefits from land ((e)), was closely related to social alliances (e.g. especially through clan and patron/client relations).

Thirdly, the ability to generate cash assets, and the ability to selectively interact with markets, allowed some households to strategically use livestock markets to gain benefits while others were forced to sell livestock at inopportune times, such as when market prices had crashed. Success in livestock keeping was closely linked to farming success as well as indirect benefits from land ((e)), and assets gained which, in turn, supported livestock production, highlighting the importance of the overlap in different benefit pathways represented in . Farming outcomes were in great part determined by the ability to raise cash assets for farm inputs, the ability to strategically interact with markets, to prevent or buffer impacts of wildlife and pests, and to form social relations that shaped plot allocation.

Fourthly, changes in mobility, labor, markets, and intensification of farming also interacted with technology and knowledge to shape access to land, and had differential livelihood outcomes. 'Improved' livestock breeds and cash crops brought new abilities to benefit from land for some, but also introduced new livelihood stressors through sensitivity to scarcity of grass, livestock disease, crop pests, and wildlife herbivory in farms ((i)). These also required other technologies (e.g. chemical, transportation), and new forms of knowledge about veterinary drugs, farm chemicals, and markets (e.g. that of livestock brokers) for their successful use. They also required additional assets to buffer their increased sensitiviity, including increased need for labor, water, and secure access to grazing in locations like private lands.

Accumulation, the politics of access control, and cascading socio-economic differentiation

The disparities in abilities to directly benefit from land through livestock that we described above were impacted by households’ variable control of diverse assets that historically have been central to livestock production, but also the ability to control a variety of new herding assets (e.g. hired labor, grazing fees, supplementary livestock feed, transported water) .Footnote7 These disparities in livestock production were compounded by abilities to gain assets from farms, to benefit from market interactions, and to gain indirect benefits from land (e.g. lease payments, employment income, bursaries that reduced education costs). Receiving indirect benefits from land, in particular enhanced some households’ overall abilities to navigate institutions that mediated benefits from both livestock and farming, enabling them to generate surpluses in livestock, cash assets from sales of livestock and farm produce, and to recursively reinvest these in the above pathways to maximize their production. A narrow subset of households (notably, wildlife conservation NGO employees and GR representatives) were able to reap new indirect benefits from land, and were subsequently able to exploit direct benefits from land to a greater extent than other GR residents, deepening these differences in abilities to access and benefit from land. However, the ability to navigate these overlapping benefit pathways, and the overall accumulation produced through these imbricated pathways, in turn also translated into enhanced abilities to shape institutions and to enable diffuse control over land ((a)).