ABSTRACT

Critical Agrarian Studies has three actual and aspirational interlocking features which together connect the worlds of academic research and practical politics: it is politically engaged, pluralist and internationalist. These features also defined the older generation of agrarian studies that gave birth to the Journal of Peasant Studies (JPS) 50 years ago, in 1973.Footnote1 Within a decade or so of the journal's inauguration, the agrarian world had been transformed radically amid neoliberal globalization. An altered world did not render agrarian studies less relevant; on the contrary, it has become even more so, but within a different context in which political engagement, pluralism and internationalism develop new meanings and manifest in new ways.

The philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways,

the point, however, is to change it.

– Karl Marx

Critical agrarian studies

Critical Agrarian Studies enquires into the causes, conditions and consequences of societal transformations by focusing its analysis on the interaction between social structures, institutions and actors that shape the processes of change in, and in relation to, the rural world. It pays attention to questions of agency of the exploited, oppressed and marginalized groups in the rural–urban and agriculture–industry entanglement, particularly their autonomy and capacity to interpret – and change – their conditions. It is critical in three ways: it interrogates mainstream neoliberal theories; it is sympathetic to radical social movements and their proposed alternatives, but is vigilant in scrutinizing these in theory and practice; and it questions, and works to transform, the very institutions of the global circuits of knowledge.

Critical Agrarian Studies today is marked by three interlocking features: political engagement, pluralism and internationalism – as actually existing and as aspirational reference points – that together connect the worlds of academic research and practical politics. Its methods center on the fundamental guiding questions of political economy, focusing on social relations of property, labor, income, and consumption and reproduction, and on how power relations emerge and are contested and transformed. From there, it branches out widely to intersect with other issues and themes pertaining to social processes, intellectual traditions, fields and disciplines. One of its basic assumptions is that as capitalism penetrates the countryside, processes of commodification of nature and labor lead to social differentiation among the population, making class relations key to scientific inquiry (Lenin Citation2004 [1899], see also White Citation1989; Cousins Citation2022). But as Henry Bernstein explained: ‘class relations are universal but not exclusive “determinations” of social practices in capitalism’ (Bernstein Citation2010a, 115, original emphasis). He went on to elaborate: ‘They intersect and combine with other social differences and divisions, of which gender is the most widespread and which can also include oppressive and exclusionary relations of race and ethnicity, religion and caste’ (ibid.).

This definition of Critical Agrarian Studies has been the intellectual and political compass for Journal of Peasant Studies (JPS) for the past 15 years. But Critical Agrarian Studies, as a field and community, is not defined by the written words of certain scholars. More important than any written definition is how Critical Agrarian Studies has been defined in practice, including how it has actually been understood and experienced by scholars and activists who comprise the field's community.

This paper looks back at the past 50 years of JPS more generally, with special attention given to the past 15 years of JPS under the editorial team that took over the journal leadership in 2009. The team started to work in early 2008, preparing the 2009 volume. Generational renewal in the editorial team is key to maintaining the vibrancy of the journal. It is for this reason that the JPS Editorial Collective has implemented some changes, with several of its members migrating to the International Advisory Board, while some new members have recently joined. JPS has also shifted away from a solo Editor-In-Chief set-up to a team structure, with a new set of core Editors. Furthermore, and by deliberate design, the overwhelming majority of the new Editors are from or in the Global South, and are in relatively early and middle academic career phases: this ensures that JPS retains its dynamism, while contributing to ongoing efforts to democratize the global circuits of knowledge. These specific editorial team changes are a tiny part of a bigger dynamic unfolding in the field. This paper therefore aims to understand the interrelationship between the transformation of the field and the journal during the past 50 years partly in order to see the outline of pending challenges. It is thus an analysis of the interweaving of dynamics in the field and the journal, based on the belief that they have shaped one another over time. The remainder of this section traces the history of classical agrarian studies and the emergence of Critical Agrarian Studies. It is followed by three sections dedicated to exploring the three defining features of the field, namely, political engagement, pluralism and internationalism, before a final section offers some closing remarks.

*****

Like JPS, Critical Agrarian Studies traces its provenance to what can be called the ‘classical agrarian studies’ that was part of a broadly Marxist tradition of agrarian political economy and was dominant during the previous century. Critical Agrarian Studies places utmost importance on how social structures, agrarian institutions and political agency of social classes and groups are constructed, reproduced and transformed across space and over time. It privileges inquiries into how the exploited and oppressed social classes and groups understand their conditions and try to subvert and change them to achieve greater degrees of fairness and justice, even as ‘fairness’ and ‘justice’ are themselves contested concepts. Yet, there are multiple appreciations and interpretations as to what the field is. The abbreviated interpretation we put forward above is just one of these, and it overlaps with the views of Edelman and Wolford (Citation2017) and Akram-Lodhi et al. (Citation2021):

Critical Agrarian Studies are simultaneously a tradition of research, thought and political action, an institutionalized academic field, and an informal network (or various networks) that links professional intellectuals, agriculturalists, scientific journals and alternative media, and non-governmental development organizations, as well as activists in agrarian, environmentalist, agroecology, food, feminist, indigenous and human rights movements. These linkages are not easily mapped or bounded, in part because of their complexity and in part because their contours shift over time. (Edelman and Wolford Citation2017, 962)

The field of classical agrarian studies – which was/is also popularly and loosely referred to as ‘peasant studies’ – was a trailblazer in many ways, with the fundamental texts associated with the early phase of that field having framed enduring analytical and political puzzles that persist up to the present. These include many formulations by Marx himself, especially on questions of politics elaborated in the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (Marx Citation1968 [1852]), Engels’ original formulation of the ‘peasant question’ (Citation1968 [1852]), Kautsky's formulation of the ‘agrarian question’ (Kautsky Citation1988 [1899]), and Lenin's elaboration on how capital penetrates and transforms the peasantry and the countryside (Lenin Citation2004 [1899]; see also Chayanov Citation1986 [1925]).Footnote2 Taking peasant politics as something too important to ignore, the classic texts are theoretical and political and, in some instances, they also informed politico-military calculations by communist and socialist parties and the mass movements associated with them, as demonstrated in the 1920s–1930s socialist construction in the USSR, as well as in Mao's strategy of ‘Protracted Peoples’ War’ (PPW).

Shortly after this generation of classic texts, a number of influential books were published in the 1930s and 1940s, notably, McWilliams (Citation2000 [1935]), Fei (Citation1939) and Polanyi (Citation2001 [1944]). But the golden era of classical agrarian studies is the period between the 1950s and the first half of the 1980s, which produced seminal works by world-leading (albeit overwhelmingly Northern) authors including Marc Bloch, Anton Blok, Eric Wolf, Barrington Moore Jr., Polly Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, Teodor Shanin, James C. Scott, Jeffrey Paige, E.P. Thompson, Raymond Williams, John Womack, Arturo Warman, Michael Watts, Sidney Mintz, Alain de Janvry, Benedict Kerkvliet, Keith Griffin, Samuel Popkin, Michael Lipton, Jack Kloppenburg, Gillian Hart and Catherine LeGrand, to name a few. This list of book authors excludes a much longer list of scholars who published highly influential journal articles or book chapters during this period, such as Harriet Friedmann, Hamza Alavi, Robert Brenner, Cristóbal Kay, Mahmood Mamdani, Sam Moyo, Issa Shivji, Utsa Patnaik, Terry Byres, Henry Bernstein, Rodolfo Stavenhagen, Gerrit Huizer, Philip C.C. Huang, Philip McMichael, Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sara Berry, Carmen Diana Deere, Amartya Sen, Bina Agarwal, John Harriss, Barbara Harriss-White, Ben White, Bridget O’Laughlin and Ashwani Saith. Many of these were published in Past & Present and Journal of Peasant Studies. This period was the gilded age of agrarian political economy.Footnote3

By agrarian political economy I mean, loosely and broadly, the field of study that enquires into how social structures, institutions and political agency of social classes and groups arise, how they interact with one another in relation to production and social reproduction, and how power relations that emerge from this are contested and transformed (Bernstein Citation2010a). Taking social relations within and between classes and groups in society as a focus of inquiry, agrarian political economy necessarily takes ‘class relations’ – and class struggles – as the fundamental reference points, aware that there have been serious debates as to what these mean, how they manifest in the real world, and why and how they are central to explaining agrarian change (Bernstein Citation2010a, Thompson Citation2016 [1963], Harriss-White Citation2022; see also Friedmann Citation2019). Moreover, political economy takes historical method as key in its enquiry into class dynamics (Bloch Citation1992 [1954], Hobsbawm Citation1971; Byres Citation1996; Edelman and León Citation2013). On peasant politics specifically, a preoccupation in classical agrarian studies is how to transform ‘class-in-itself’ (socioeconomic category) to ‘class-for-itself’ (political category) (Marx Citation1968 [1852], Byres Citation1981). This taps into the fundamental puzzle of how peasants become revolutionary (Huizer Citation1975), and necessarily, its flipside: how do peasants become, or remain, reactionary? This aspect of agrarian political economy is far more nuanced than some sceptical characterizations imply, in the sense that no one argues that class alone can explain everything about agrarian change and politics. If one's understanding of agrarian political economy is along the broad outline spelled out at the beginning of this paragraph, then the Marxist interpretation stands as the most important, but certainly not the only, tradition in agrarian studies.

In this context, the tradition stemming from the classical Russian agrarian populists, with the various incarnations and hybridizations it has undergone over time, represents another important stream. The foundational ideas of A.V. Chayanov in Russia during the period of the Bolsheviks form a significant branch of this lineage (Chayanov Citation1986 [1925]). His ideas were revived, updated, developed and extended further by a corps of trailblazing agraristas, including Teodor Shanin (Shanin Citation1971), Scott (Citation1976) and van der Ploeg (Citation2013), among others. None of these is a purist Chayanovian and all of them use Marxist theories and concepts to varying extents. In Latin America, especially in Mexico, there was a related fierce debate in the 1970s and 1980s between the ‘peasantists’ (‘campesinistas’) and ‘depeasantists’ or ‘proletarianists’ (‘descampesinistas’ or ‘proletaristas’) (Kay Citation2000). This body of work is rich and diverse, deeply informed and grounded, and more nuanced than the caricature that some critics draw under the pejorative catch-all label of ‘neopopulist’, meaning ‘class-blind’, engaged in ‘restorative struggles’ and thus ‘nostalgic and romantic’, if not ‘utopian and reactionary’.

While the fundamentals of Critical Agrarian Studies are directly traced to the two traditions of political economy discussed above (Marxist and Chayanovian), it does not mean that the latter are the only important traditions that have energized and animated the field. Since the 1990s, there are two other intellectual traditions that made significant contributions to the construction and expansion of the reach of Critical Agrarian Studies. The first one is the ‘Livelihood Approach’ that has acquired various labels, the most common of which is the Sustainable Rural Livelihoods Approach. This approach has become quite popular not only among academic researchers but especially among the international development and donor organizations partly because it could easily blend with mainstream thoughts such as New Institutional Economics. The cumulative work by Ian Scoones, starting from Scoones (Citation1998)Footnote4 to Scoones (Citation2009a) and Scoones (Citation2015), has contributed to bringing this approach closer to radical versions of agrarian political economy (and for bringing the latter to the former). The result is a rich hybrid approach that has developed its own huge following worldwide. The second is Food Regime studies and, as a consequence, the broader studies of global food politics. Firmly located in the conventional debate and literature on the ‘agrarian question’ (Akram-Lodhi and Kay Citation2010a, Citation2010b), classical agrarian studies had its scope of enquiry largely focused on the domestic or national social processes. Harriet Friedmann and Philip McMichael, in their seminal work in 1989 (Friedmann and McMichael Citation1989), opened up a door to the international dimensions of the ‘agrarian question’ which, arguably, are so significant today, and have generated and required a different interpretation of Marxism. This means seriously attempting to scientifically analyze (and politically organize against) how capital as a global force (agribusiness, finance and digital companies, exerted through political dealing at the state and international institutional levels) is (re)shaping agrarian conditions and territories across the world (see, e.g. Clapp and Isakson Citation2018; Fraser Citation2019; Canfield, Anderson, and McMichael Citation2021). A continuity and elaboration of the classic Friedmann and McMichael (Citation1989) within the twenty-first century context, Friedman (Citation2000) is an initial analytical key to this kind of approach. Since then, the macro-historical method of understanding the historic shifts in the international food trade and related hegemonic transitions has become increasingly intertwined with many of the basic components of the agrarian questions in classical agrarian studies, and have been interwoven with what could become an even bigger field of global food politics. The fusion of Friedmann and McMichael's ‘Food Regime’ studies with classical agrarian studies has contributed immensely to the construction of what we now know as Critical Agrarian Studies. The Scoones version of the Sustainable Rural Livelihoods Approach and the Food Regime perspective by Friedmann and McMichael are both hybrid approaches that have been constructed by revising, and/or borrowing concepts from, several intellectual traditions. In turn, this would contribute to an important tendency in Critical Agrarian Studies today: the tendency to not see scientific and political rigor as something that can only be achieved through ‘purist’ or orthodox approaches. This has contributed to making Critical Agrarian Studies a nondogmatic, heterodox and welcoming field for many scholars and activists, encouraging more creative and bolder intellectual and political explorations.

My particular interpretation of Critical Agrarian Studies is based on my own political and academic work and history,Footnote5 and on the experiences of a diverse global community of academic and activist researchers and networks that are directly and indirectly linked to Journal of Peasant Studies.Footnote6 On the one hand, before I got into academia, I was for a long time deeply involved in radical rural mass movement organizing and mobilizing work in the Philippines and, later, internationally. I was a member of the International Coordinating Committee of La Via Campesina in 1993–1996. In my experience, all those who work in the trenches – directly engaged in the painstaking work to build agrarian mass movements – internalize the tensions and contradictions generated in the theoretical and political (and politico-military) debates. They are confronted by a neat textbook Marxist-Leninist notion of what and how agrarian movements ought to be, and what political contingency requires militants to do. The easier and safer task is to interpret classic texts academically. The more difficult and riskier task is to interpret classic texts politically and, in some instances, politico-militarily. This is related to the primary task of academic scholars to critique, in contrast to the task of political cadres or militants in the trenches to build. Building something – a movement, a political project, a revolution – is inherently contentious, experimental, open-ended, and subject to hits and misses. For example, building the idea of food sovereignty and constructing its accompanying mass movement will be marked by successes and failures, imperfections and contradictions. It is easy to judge a movement's achievement as ‘half empty’ when measured against the standards set by classic theoretical texts, and by doing so one does not have to explain much beyond enumerating what's wrong and listing the shortcomings that are often quite obvious to outsiders. This narrative can be demobilizing. If you are operating fully or partially in the trenches, the one thing you do not need is a demobilizing narrative. What is more challenging is to see a movement's accomplishment as ‘half full’, and explain why this is so, because positive accomplishments may not always be obvious especially to outsiders. The latter implies hope that for those in the trenches is a political resource like no other as it can keep a movement energized and mobilized. It is one thing to observe the process from a distant, comfortable, academic window and critique it for its intellectual deficit. It is quite another to identify its shortcomings and problems from inside the trenches in order to rectify them politically and ratchet up collective action. Often, it requires more creative intellectual and political energy to figure out how to organize and mobilize landless workers in a small banana plantation owned by a violent landlord supported by a corrupt provincial official and police than to read and comprehend a set of Marxist literature on social differentiation of the peasantry. I am not saying that one task is relevant and the other not; it is not a question of ‘either/or’, rather it is about how to combine critiquing and building, the intellectual and political tasks – and achieving this is the most difficult task of all. This is the experience that shapes my own perspective of Critical Agrarian Studies.

On the other hand, my interpretation of Critical Agrarian Studies also draws from a broader collective process of knowledge politics around JPS and its wide networks. These include the Initiatives in Critical Agrarian Studies (ICAS, established in 2007Footnote7), Land Deal Politics Initiatives (LDPI, formed in 2010Footnote8), BRICS Initiatives in Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS, organized in 2014Footnote9), Emancipatory Rural Politics Initiative (ERPI, launched in 2017Footnote10), and the JPS Annual Writeshop in Critical Agrarian Studies and Scholar-Activism (started in 2019Footnote11). The latter initiative involves collaborating with early career researchers from the Global South, who formed the Collective of Agrarian Scholar-Activists in the South or CASAS.Footnote12 The academic and activist researchers who have animated these networks and initiatives come from various fields, disciplines and thematic interests, as well as different ideological persuasions. It is a polycentric, global community, a movement with active participation of diverse individuals and groups.

The broad transition from classical agrarian studies or ‘peasant studies’ to Critical Agrarian Studies occurred in JPS with the editorial team change in 2008–2009,Footnote13 around the same time that the landmark World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development was released, which outlined the fundamental doctrines of neoclassical and new institutional economics in agriculture (World Bank Citation2007).Footnote14 The first issue of JPS in 2009 included an editorial article that outlined five elements of what is now called Critical Agrarian Studies (Borras Citation2009). First, the altered context for and object of agrarian transformations and politics as well as scientific research have affirmed the significance of orthodox Marxism – and the many currents within Marxism – but at the same time have opened doors for other complementary or even competing traditions and approaches (ibid.: 5–13). Second, the growing traction of diverse radical theories and methodologies has occurred in an increasingly pluralist academic and political atmosphere. Third, there has been a remarkable increase in the degrees of appreciation of the mutually reinforcing interactions between academic research and radical practical politics. Fourth, Critical Agrarian Studies questions prescriptions emerging from mainstream perspectives, while interrogating popular conventions in radical thinking (ibid.: 25). Finally, while the methods of work of Critical Agrarian Studies cannot be reduced to or interchanged with ‘scholar-activism’, the latter is an important aspect of the former. The importance of a scholar-activist approach was underscored in the 2009 JPS editorial article (ibid.: 23–24):

Development practice and activism that are informed by rigorous critical theories are more effective and relevant, and are less likely to cause harm within the rural poor communities, than those that are not […] Co-production of knowledge and a mutually reinforcing dissemination and use of such knowledge among academics, development practitioners and activists are likely to address some of the key weaknesses of a purely theoretical research detached from the real world, or of a too practice-oriented initiative without theoretical and methodological rigor.

JPS made enormous contributions to classical agrarian studies under its founding editor, Terry Byres, and the other previous editors, Teodor Shanin, Charles Curwen, Henry Bernstein and Tom Brass. Until recently, the field of Critical Agrarian Studies was a somewhat amorphous discipline and community. The particular contribution that JPS has made since 2009 to this evolving field is to help provide some shape and form, making it less nebulous. Critical Agrarian Studies and JPS have drawn energy and strength from each other. One factor explaining why JPS has soared to the highest level of citation impact, and has remained at that level for the past decade or so, is the vibrancy of Critical Agrarian Studies; and one factor explaining that vibrancy is the trailblazing work done by JPS. I say this with the necessary caveats about the political economy of the publishing world, and the flaws in official metrics, such as ‘impact factor’ and so on (see Burawoy Citation2014; Deere Citation2018).

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the community of JPS and allied networks is not the only prominent hub of agrarian conversations and research. Three other eminent communities at the center of the field are, (i) the Agrarian Studies Program at Yale University, with its long-running colloquium series that was anchored by James C. Scott until recently (it is currently co-directed by Shivi Sivaramakrishnan and Elisabeth Wood); (ii) Journal of Agrarian Change (JAC) and the ‘Agrarian Change Seminar’ seriesFootnote20 and related activities based at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London; and (iii) Agrarian South: Journal of Political EconomyFootnote21 associated with the Sam Moyo Institute of Agrarian StudiesFootnote22 based in Harare, with activities which include an annual summer school dedicated to young scholars from the Global South. JAC and Agrarian South are both committed to Marxist agrarian political economy.

JPS, JAC, Agrarian South and the book series mentioned above are not the only journals and book series that have significant engagement with and make contributions to Critical Agrarian Studies, but they are the publications in English that are fully dedicated to the field. There are many other journals from allied fields that occasionally publish articles that engage, partially or fully, with Critical Agrarian Studies. These include Journal of Rural Studies, Land Use Policy, Antipode, Geoforum, Monthly Review, Sociologia Ruralis, Rural Sociology, Annals of American Association of Geography, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, Environmental and Planning (A and D), and Agriculture and Human Values. Several journals in development studies and international political economy, including Third World Quarterly, Globalizations, World Development, Canadian Journal of Development Studies and Development and Change, also publish articles that engage with Critical Agrarian Studies.Footnote23

Knowledge is political. A fundamental starting point in Critical Agrarian Studies is that the global circuits of knowledge (generation, attribution, circulation, exchange and use) are politically contested. Moreover, given that academic knowledge is generally located in formal institutions (universities, colleges, research institutions) that are in turn embedded in the global capitalist system, it is not possible to disentangle knowledge contestations from the contestations within and against capitalism (Burawoy Citation2014; Rodney Citation2019). The points highlighted by Scoones (Citation2009b) in the context of his analysis of the politics of the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD) are important and frame the discussion of this paper. In his words:

[…] some of the knowledge contests involved in the assessment […] illuminate four questions at the heart of contemporary democratic theory and practice: how do processes of knowledge framing occur; how do different practices and methodologies get deployed in cross-cultural, global processes; how is ‘representation’ constructed and legitimised; and how, as a result, do collective understandings of global issues emerge? The paper concludes that, in assessments of this sort, the politics of knowledge needs to be made more explicit, and negotiations around politics and values, framings and perspectives, need to be put centre-stage in assessment design. (Scoones Citation2009b, 547)

Political engagement

In his classic primer, community organizing pioneer Alinsky (Citation1989: ix [orig. 1946]) declared:

I am still irreverent. I still feel the same contempt for and still reject so-called objective decisions made without passion and anger. Objectivity, like the claim that one is nonpartisan or reasonable, is usually a defensive posture used by those who fear involvement in the passions, partisanships, conflicts, and the changes that make up life; they fear life. An ‘objective’ decision is generally lifeless. It is academic and the word ‘academic’ is a synonym for irrelevant.

During the upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, the most vibrant hub of academic conversations on agrarian political economy, at least in Europe, emerged at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, with the Peasant Studies seminar series coordinated by a group led by Terry Byres (Citation2001). It was a politically engaged initiative, discussing and problematizing some of the most pressing issues of the time: peasant revolutions, transitions to socialism, understanding peasants in the context of revolutionary and reactionary forces, the then newly launched Green Revolution, raging famines, the birth and rise of the global food aid complex, and reinterpretations of history.

The immediate context for classical agrarian studies were the socioeconomic conditions of the exploited and oppressed agrarian classes of the 19th and 20th centuries, and the objective was to examine how these classes understood their conditions, and how they mobilized to change their situation (Bernstein et al. Citation2018). Most of the early studies were extensions of historical debates and inquiries. Subjects included the French peasantry, observed by Marx in the mid-nineteenth century to be providing a social base for Bonaparte, or the peasants of France and Germany in the context of attempts to win votes for the political party of the socialists – topics raised by Engels and Kautsky at the end of that century (Engels Citation1968 [1894], Kautsky Citation1988 [1899]). There were discussions about the relevance of agrarian relations in the uneven development of capitalism in Russia and the role that various strata of the peasantry (poor, middle, or rich peasants) could play in revolutionary or reactionary politics in the USSR during the 1920s and 1930s. Another illustrative example of what it means to be politically relevant is the classic and iconic scholar-activist book by McWilliams (Citation2000 [1935]) on the multiple crises of the Great Depression that resulted in the misery, but also in the exercise of political agency, of the working class. The book starts with the discovery of gold in mid-nineteenth century California and the ensuing gold rush, which subsequently led to the construction of California as a center of large-scale industrial agriculture. McWilliams’ analysis includes the arrival of waves of Indigenous, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Filipino and Mexican laborers, which coincided with the migration of millions fleeing from the Dust Bowl of the Great Plains during the Depression. This period generated important research in classical agrarian studies that would later impact present-day Critical Agrarian Studies (Mitchell Citation1996; Holleman Citation2018). The point that I would like to emphasize through these examples is that scholarly works are products of their time, even the contemporary works that aspire to explain the present through an historical lens, such as the groundbreaking books by Watts (Citation2013 [1983]), Mintz (Citation1986), Mitchell (Citation1996) and Davis (Citation2002).

The objective conditions that helped shape classical agrarian studies were transformed once neoliberalism gained momentum in the 1980s. The era of peasant wars that Wolf (Citation1969) chronicled was over. The generation of peasant movements directed by communist and socialist parties, in which non-armed collective actions were subordinated to clandestine armed struggle (Putzel Citation1995), was gone. The classic Green Revolution and the original version of US food aid, driven by Public Law 480 in the context of the tail-end of the Second Food Regime (Patel Citation2013; Friedmann and McMichael Citation1989), metamorphosed into something significantly different in a world where biophysical carrying capacity and the role played by industrial agriculture were under serious scrutiny (Weis Citation2010). The Cold War ended, and with it the many socialist-oriented land and agricultural development models (Spoor Citation2012). Nationalist development campaigns and the role played by agrarian reform in these campaigns were also over, even if the quest for the improved well-being of humanity and the need to democratize the politics of land have remained urgent and necessary (Franco and Borras Citation2021; Mudimu, Zuo, and Nalwimba Citation2022; Kay CitationForthcoming). The framing of radical and nationalist agrarian movements’ campaigns around agrarian reform has, during the past three decades, expanded to campaigns around ‘land and territory’ (Rosset Citation2013; Brent Citation2015) and political framing has expanded to include human rights perspectives (Monsalve Citation2013; Thuon Citation2018). Yet, many fundamental realities have persisted, albeit in altered forms.Footnote24

The rise of radical agrarian movements that are relatively autonomous from political parties was one of the most important changes in the global agrarian front that would shape the agenda of Critical Agrarian Studies (Edelman and Borras Jr Citation2016). Following Fox (Citation1993), I view autonomy as the degree of intervention or influence of external actors on the internal decision-making processes of an organization or movement. Autonomy is not an ‘either/or’ question, judging whether a movement is completely co-opted by, or totally independent from, actors external to it, such as the state or political parties. Autonomy is a matter of degree. There are two types of current autonomous agrarian movements: (a) those that were not created by political parties and those that have always been relatively independent of political parties, including many anarchist or anarcho-leaning groups; and (b) those that were created by communist and socialist political parties, but that have progressively distanced themselves from these parties, allowing them to pursue political projects, coalitions and campaigns, such as food sovereignty, agroecology, other popular food politics-oriented initiatives, or other issues that are not staples of conventional left agrarian movements. Such movements remain rooted in class politics, but have expanded to include overlapping axes of social difference (race, ethnicity, gender caste, generation), taking social class and identity as co-constitutive. They represent a new generation of agrarian movements that combine elements of class-oriented politics of their past counterpart movements, with attention to contemporary issues like climate, environment and indigeneity, among others (Veltmeyer Citation1997; Petras and Veltmeyer Citation2001). Their notion of alliance is different from the classic worker–peasant alliance orchestrated by communist or socialist parties (Shivji Citation2017), and their emphasis on issues such as food sovereignty, agroecology, environmental justice or climate justice brings in different types of allies, and leads to the formation of new types of coalitions (Tramel Citation2016; Claeys and Delgado Pugley Citation2017; Sekine Citation2021; Yaşın Citation2022; Bjork-James, Checker, and Edelman Citation2022).

Contemporary agrarian movements are a reaction to neoliberal capitalism, and at the same time they are a creation of neoliberalism. Edelman's Peasants Against Globalization (Citation1999) on Costa Rican peasant movements and Peasants Beyond Protest by Biekart and Jelsma (Citation1994) on the Central American transnational agrarian movements’ coalition ASOCODE are excellent illustrations of this. Many later studies on the rise of La Via Campesina also underscore the same point (Desmarais Citation2007; Martínez-Torres and Rosset Citation2010; Wittman, Desmarais, and Wiebe Citation2010). The rise of a new generation of agrarian movements, and their proliferation, coincided with a similar rise of diverse radical social justice movements that lean towards the intersection of class and identity politics, such as Indigenous Peoples, Black Lives Matter, and feminist movements, as well as broad movements that are bound together by common interests such as food sovereignty, agroecology, climate justice and environmental justice advocacy. These, in turn, have shaped and influenced policy and academic research (Bjork-James, Checker, and Edelman Citation2022). Key issues on the agrarian front have become even more plural and diverse than in the past, and the social justice movements that emerged separately around each sub-theme, and collectively in the broadest sense of the agrarian world, have become more widespread. Thus, while La Via Campesina is the best-known transnational agrarian movement today, there are other important progressive and radical social movements that run parallel to it or are allied with it (Mills Citation2021). This has provoked political and academic debates revolving around class and axes of social difference. Competing views on the Indian new farmers’ movements of the late 1980s and early 1990s, for example, are illustrative of highly contested issues of class and identity politics (Brass Citation1995, Citation2000; Baviskar Citation1999; see also Veltmeyer Citation1997 for the Latin American context). This changing terrain has become an exciting subject of academic research, and is largely responsible for how agrarian studies has transformed into what we know now as Critical Agrarian Studies.

Having an impact on policy debates is a central interest of Critical Agrarian Studies and within JPS. Political and academic agendas and debates shape and are shaped by policy debates. The case of biofuels is a good illustration. Here, policy shifts in the United States and the European Union have transformed the political economy of the global production, exchange and use of key feedstocks such as corn, sugarcane, oil palm and rapeseed (Franco et al. Citation2010; McCarthy Citation2010), as well as climate change mitigation policies (Corbera and Schroeder Citation2011; Paprocki Citation2021), Climate Smart Agriculture (Clapp, Newell, and Brent Citation2018), and organic agriculture certification (Guthman Citation2014; Galvin Citation2021). In turn, these shifts have triggered global campaigns and mobilizations by social justice movements, and generated interest among academic researchers. If we look at the global agrarian front and the key issues that have exploded during the past decade, we see that the ranks of researchers who work on these issues, and who are at the same time directly involved in social justice movements that aim to influence the character and trajectory of agrarian transformations, have grown exponentially. But this process is highly contested. Political engagement is often conflated with ‘societal relevance’, and loose and competing interpretations abound. To some, ‘societal relevance’ means building a partnership between a fossil energy transnational corporation and conservation NGOs, but to others this is politically unacceptable. Researchers in Critical Agrarian Studies see political engagement as a key element in their research work, but are aware that what it actually means is fiercely debated. JPS, too, uses political engagement as a compass, including in deciding the topics on which to organize its themed issues.

The years 2007–2008 represent a significant reference point in Critical Agrarian Studies. During this time, a number of global events and issues erupted and converged which would prove to be central to the field: the global financial crisis, a key report on global land grabs, the rising prominence of biofuels, food price hikes, UNFCC's climate change negotiations attracting unprecedented attention, and media reports on the rise of the BRICS countries. A few years later, there was a global buzz about governance crises amid the rise of right-wing populists and, more recently, the Covid-19 pandemic. Separately and in combination, these have helped consolidate and then expand the research agenda of Critical Agrarian Studies.Footnote25 Equally important, this period has seen growing agrarian-oriented social justice movements and wide-ranging forms of collective actions, popular initiatives from below, and advocacy campaigns.Footnote26

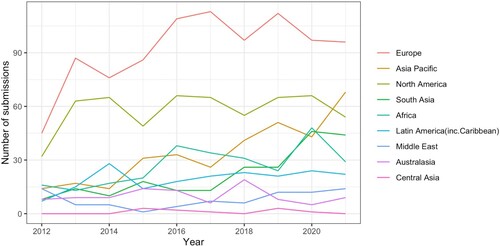

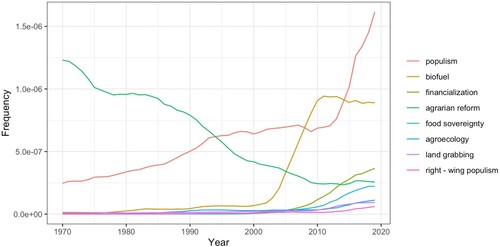

Trends shown in point to shifts in the agrarian world, as well as the transition from classical agrarian studies to Critical Agrarian Studies. Notably, ‘agrarian reform’, which was so central in public and academic debates during the first three quarters of the past century, has seen a marked decline since the onslaught of neoliberalism in the 1980s (Akram-Lodhi, Borras Jr, and Kay Citation2007), even though the imperatives of redistributive land reforms remain urgent (see e.g. Ra and Ju Citation2021). That agrarian reform nevertheless retains a certain level of significance today is most likely the result of a handful of prominent national agrarian reform cases, especially in Brazil, Zimbabwe and South Africa (in Brazil, the role played by a world-renowned landless movement, MST, might have also helped). At the same time, themes that were insignificant in the 1970s and 1980s began to emerge in the 1990s and 2000s and have increased either sharply or steadily since then. These include populism (including the smaller sub-category of right-wing populism), biofuels, financialization, food sovereignty, agroecology and land grabbing. These themes started to be picked up regularly from around 2005, and gathered much more momentum around 2007–2008. The keywords included in remain popular themes in Critical Agrarian Studies, and their trajectories continue to be upward. These are themes that have preoccupied and animated the spaces for global public policy debates, as well as the research community of Critical Agrarian Studies, and have dominated the pages of JPS for the past decade or so.

Figure 1. Trends in Selected Key Themes, 1970–2020.

Note: Figure generated using ngramr and ggplot2 packages in R 4.2.1.Footnote27

In that time, JPS has interacted closely with radical social justice movements, particularly those associated with agrarian and environmental justice. Most of its themed collections have been products of, or have been extensively debated in, large international conferences co-organized by JPS with other international research networks, including world-leading agrarian and environmental justice movements. It is not an exaggeration to say that radical social movements often set the agenda for research, and academic researchers more or less follow. This has been the context in which JPS-related events were conceived and organized. During the last 10–15 years, important international gatherings were held at Saint Mary's University in Halifax (Canada), International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, Institute for Development Studies (IDS) in Brighton, Cornell University in New York, Yale University in Connecticut, College of Humanities and Development Studies (COHD) of China Agricultural University in Beijing, Chiang Mai University, Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) in Moscow, University of Brasilia, and Universidad Externado de Colombia in Bogotá, as well as co-organized with EHNE-Bizkaia in Vitoria-Gasteiz in the Basque country. These major events were often either co-organized by or prepared in direct dialogue with key social justice movements: Transnational Institute (TNI), La Via Campesina, IPC for Food Sovereignty, Friends of the Earth, FIAN, Food First, GRAIN, and Focus on the Global South, among others. The methodology adopted and the overall tone and atmosphere were necessarily a hybrid between a conventional academic conference and an activist movement event. In these JPS-related conferences, movement activists were given the same level of importance in terms of speaking slots, and events sometimes opened with a mistica – a short dramatization of social realities and political struggles (see interview article with Paul Nicholson in this JPS issue), in an informal, festive atmosphere – often accompanied by powerful images from the paintings of Filipino activist artist, Boy Dominguez or BoyD (see Iles Citation2022).

One can perhaps say that a watershed moment for Critical Agrarian Studies was the large international conference on land and social justice held at the ISS in The Hague in January 2006. To my knowledge, this was the first time that radical academics (from followers of multiple currents of agrarian Marxism to those broadly inspired by Chayanovian and agrarian populist ideas) and world-leading anti-capitalist agrarian movement leaders converged on such a scale. It was truly international (with simultaneous language translation facilities), numbering more than 300 participants (with activists constituting more than a third of the total participants) locked in a nearly week-long period of serious debates about some of the most consequential agrarian issues in the world.Footnote28 The event was truly politically engaged, conducted in a pluralist atmosphere, and very internationalist in orientation and composition. The event also served as a reminder to the participants that the academy is not the only place in which important knowledge is generated and that academic researchers are not the only ones who generate that knowledge; the political trenches and agrarian movements are also sites and producers of knowledge.

Such events provide platforms at which leading radical academics and activists are able to meet face to face, and exchange ideas and views about burning global issues. Often, these dialogues do not result in consensus, but we suspect that they have short- and long-term transformational effects on both sides, one of which is the building of mutual respect of key intellectuals on both sides, despite differences and scepticism. They have also resulted in long-lasting collegial relationships and further research collaborations. Re-viewing the collection of video recordings from some of these events provides a welcome reminder as to how such encounters occurred.Footnote29

In 2020, the Agrarian Conversations webinar series was launched. This is a collective effort by JPS and TNI, ICAS, CASAS, COHD in China Agricultural University in Beijing, Young African Researchers in Agriculture (YARA) and PLAAS of the University of the Western Cape. It is dedicated to some of the most pressing issues that concern academics and activists worldwide. Each webinar is conducted in at least three languages for greater global participation. The response has been promising, with an average of 900 registered participants for each webinar.Footnote30 The first three were quite global in scope, addressing topics that are the subject of animated public policy and political discussions: China's key role in the transformation of the global food regime, pastoralists and the world, and the global rise of authoritarianism and populism – topics which have also been the focus of academic publications (see, e.g. McMichael Citation2020; Scoones Citation2021; Scoones et al. Citation2018; Roman-Alcalá, Graddy-Lovelace, and Edelman Citation2021).

The timing of the interventions by JPS and related research networks is crucial: conferences have been organized and subsequent publications released at moments when these social phenomena were being hotly debated and popularized (see ). For example, JPS organized a global conference on biofuels in 2009 and published a special issue in early 2010; JPS organized the first major international academic conference on global land grabbing in early 2011, at the same time that it released its first collection of land grab articles. The timing of these events was influenced by the political debates spearheaded by radical social movements. In turn, the conferences and publications influenced the character and trajectory of the very subject of their conversations and scientific inquiry. This is a hallmark of today's Critical Agrarian Studies: timely intervention with the aim of reshaping agendas and methods of debate in the context of promoting greater fairness and social justice. The issue of timing is one aspect of political engagement. It generates a classic dilemma in the intersection of scholarship and practical politics, that is, when to call for the closure of research processes and when to continue looking for more evidence and maturation of the theorizing process. The difficult balancing act required by this dilemma is a constant challenge in Critical Agrarian Studies.

The issue of political engagement and the sense of ‘timing’ around knowledge generation, circulation and use brings us to a particular facet of Critical Agrarian Studies, that is, ‘scholar-activism’. This is defined here in the broadest terms as a way of approaching the politics of the circuits of knowledge (generation, attribution, circulation, exchange and use) with the aim not only to reinterpret the world in various ways, but to change it, and to change it in the direction of fairness and social justice, while democratizing the very institutions within which knowledge processes are embedded. Classical agrarian studies had its generation of ‘scholar-activists’, although the terms used varied: public intellectuals, radical scholars, militant academics, etc. (see, e.g. Yan, Bun, and Siyuan Citation2021; Tadem Citation2016; Baud and Rutten Citation2004; Gramsci Citation1971). They were predominantly individuals who sympathized with or supported national liberation and anti-colonial struggles as well as socialist political projects. This type of intellectual is still important in today's Critical Agrarian Studies, but is no longer dominant. The field has spawned multiple and diverse types of scholar-activists, many of whom are anti-capitalist in orientation or by implication, along the lines of Wright's typology of twenty-first-century anti-capitalist struggles (Wright Citation2019), and hold political positions in relation to agrarian movements (Edelman Citation2009; Hale Citation2006). Scholar-activists in the 1970s and 1980s helped classical agrarian studies transition into what we know today as Critical Agrarian Studies, partly by reframing the kind of research questions and agendas of political and policy debates, and methods of political work: their contributions proved to be precursors to what would become dominant scholar-activist agendas and methods of work. Two examples of such scholar-activists from this period are Frances Moore Lappe of Food First (see Diet for a Small Planet, 1971) (Lappe Citation1971) and Susan George of the Transnational Institute (see How the Other Half Dies, 1977) (George Citation1977). Contemporary scholar-activists have helped to radicalize the global academy in different ways, and in this sense, Critical Agrarian Studies and the current generation of agrarian-oriented scholar-activists have been mutually reinforcing. What this implies is that Critical Agrarian Studies necessarily internalizes not only the positive energy that is generated by rising global agrarian-oriented scholar-activism, but also the dilemmas and contradictions that it brings (Hale Citation2006; Edelman Citation2009; Piven Citation2010).

In all the conferences and webinars organized by JPS and allied networks, the politico-academic character is the same: a platform of conversation among some of the most important academic researchers and influential social justice and agrarian movement activists. In this process, the importance of political engagement is repeatedly affirmed, even while its very meaning is continuously redefined by dialogue participants. The way that political engagement has been interpreted in Critical Agrarian Studies seems to have been influenced, explicitly or implicitly, by two popular and enduring insights from Marx: that while philosophers of the past interpreted the world in various ways, the real point is to change it; and that ‘Men [sic] make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past’ (Marx Citation1968 [1852]: 98). Critical Agrarian Studies requires that questions of political agency and political contingency are taken seriously. For JPS, political engagement, a great sense of timing, taking political contingency seriously, and reflecting the character of Critical Agrarian Studies are among the key factors that have propelled the journal to the very top of its field, and have enabled it to maintain that level for more than a decade.

Pluralism

The second defining feature of Critical Agrarian Studies is pluralism. While the discussion in this section is shorter than the discussions on political engagement and internationalism, that does not mean that this feature is less important than the other two. In this paper, I define pluralism normatively to mean that constant rigor and mutual respect should permeate the global circuits of knowledge in academic and political terms. It implies a commitment, in theory and practice, to veering away from purist and sectarian approaches to knowledge work. Sectarianism, whether academic or political, is the belief that only one correct view or path is possible; in struggles over ideas, it is used as a justification to stifle and suppress, ridicule and shame views that do not correspond to what is officially sanctioned as correct and passed off as rigorous scholarship. In the political world this can be even more dangerous, potentially leading to (violent) suppression of dissent in which individuals or groups are banished or physically neutralized. The history of many lineages of Marxism is marred by waves of sectarianism, which on some occasions led to bloody internal purges. The orthodox Marxist-radical populist conjoined histories, and those of other related radical left traditions such as anarchism, have been partly cast and reproduced through persistent sectarianism and struggles against it.

Two important things need to be emphasized in the discussion about pluralism in Critical Agrarian Studies. First, pluralism is inherently a matter of degree; there is no either/or distinction between pluralist or sectarian. Second, the idea of pluralism is normative and aspirational. Keeping these two features in mind, it is my view that sectarianism continues to haunt Critical Agrarian Studies today – a tendency that traces its provenance, in part, to the late nineteenth century Russian debate between Lenin's party and the narodniks (populists). The very name ‘neopopulist’, a pejorative term that became attached to one type of radical agrarian political economy, necessarily internalizes the long history of sectarianism that characterized these two camps. But sectarianism, including the violence it at times engenders, is also a hallmark of Marxist political parties. Partly because of the waning of communist and socialist parties, the sectarianism emanating from that intellectual and political camp has to a certain extent eroded, although it has not been eradicated (indeed, it is my belief that sectarianism will never be completely eradicated). The flipside of this is that any normative discussion about pluralism is necessarily aspirational, inspired by real, albeit partial, gains in pluralist practices. Thus, the pluralism I discuss in this paper in the context of Critical Agrarian Studies is only partially emerging, and the higher degree of pluralism that I refer to here is aspirational. Addressing sectarianism is complicated and difficult, because the distinctions and boundaries between what is ‘a rigorous struggle of ideas’ on the one hand, and ‘a fierce sectarian dismissiveness’ on the other hand, are often blurred. It is far too common for sectarian impulses to be embellished and passed off as a rigorous theoretical stance, or – its unfortunate converse – for a less rigorous theoretical or political stance to be justified in the name of pluralism.

The absence of any hegemonic ideological bloc in radical anti-capitalist movements today, unlike the past hegemony of communist and socialist parties, has led organically to the formation of broad coalitions which are rarely dominated by any singular ideology. The key issues on the agrarian front – climate and environmental crisis, cross-border migrant workers, global food supply and hunger, the rise of right-wing populism, anti-mining – require cross-class, cross-sectoral coalitional politics. This is seen in some of the most successful agrarian-oriented transnational social justice movements, such as La Via Campesina, IPC for Food Sovereignty and Friends of the Earth. Critical Agrarian Studies and publications in JPS reflect, to a large extent, the character, plurality and diversity of key actors in contemporary agrarian struggles, and in related food, labor and environmental justice struggles.

Within the academy, the launch of JPS involved converging and coalitional forces, principally among various currents within the Marxist tradition, and secondarily between Marxists and some of the most radical thinkers among the anti-capitalist agrarian populists. While Terry Byres, an orthodox Marxist, was the principal founding editor of JPS, he chose to collaborate with the most important figure among the so-called neopopulists, Teodor Shanin, who became a co-founding editor. And while the pages of JPS were dominated by scholars from various strands of the Marxist intellectual tradition, other radical thinkers from agrarian political economy, including James C. Scott, Joan Martínez-Alier, Ben Kerkvliet, Bina Agarwal and Michael Lipton, were warmly welcomed. Such a non-sectarian convergence was a source of strength for classical agrarian studies; it was to greatly expand and become a cornerstone of Critical Agrarian Studies and of the contemporary JPS.

It is worth noting that there is a remarkable resurgence of Marxist perspectives in agrarian studies today, which might have been unintentionally provoked by a new generation of agrarian movements and struggles. The rise of La Via Campesina in the early 1990s was preceded by the emergence of a handful of strong national land movements (Moyo and Yeros Citation2005; Wolford Citation2010; Edelman Citation1999). As La Via Campesina gained strength in the second half of the 1990s, this spilled over to several national and transnational regional agrarian movements in different world regions (Edelman and Borras Jr Citation2016). The outcome today is the proliferation of transnational, national and subnational agrarian movements that are relatively vibrant, and of diverse ideological orientations, from Marxist-Leninist to non-Marxist radical movements. The emergence of these global movements may have stoked the embers of the long-running debate and tension between orthodox Marxists and the classical Russian agrarian populists, and the subsequent generations of radical intellectuals who draw inspiration from them (principally, Herzen and Chernyshevsky, Chayanov, and, much later, Shanin, Scott and van der Ploeg). Orthodox Marxists seem to be perplexed by a paradox pointed out by Bernstein (Citation2018: 1146): ‘while the best of Marxism retains its analytical superiority in addressing the class dynamics of agrarian change, for a variety of reasons agrarian populism appears a more vital ideological and political force’.

The connection between orthodox Marxism and agrarian populism actually led to mutually reinforcing, generative processes of knowledge production and practical politics – however grudgingly. Whether their ongoing interactions have somehow transformed the two camps, and if so, how and to what extent, are questions that are not easy to answer. But while caricatures have been drawn of each camp, it is important to realize that is exactly what they are – caricatures – while the reality is quite different. Levien, Watts, and Yan (Citation2018, 854) observed: ‘On the one hand, more “populist” scholarship – whether focused on land grabs, food sovereignty or land reform – has far more explicitly incorporated Marxian insights about class and the dynamics of capitalism than ever before’, but they continued: ‘On the other hand, much explicitly Marxian scholarship has moved away from its dismissal of peasant political agency; the hyper-structuralism of modes of production debates; and linear or Eurocentric conceptions of history embedded in the transition problematic and “doomed peasant dogma”’. It may be speculative to say, but this could be interpreted as a reflection of what might be a partial erosion of sectarianism over time.

This constellation of actors in the entanglement between orthodox Marxism and agrarian populism provides the lion's share of energy to contemporary Critical Agrarian Studies, and by extension, to JPS. It is pluralist, but it has limits; it is not liberally borderless. Key scholars who have pointed to the need for nuanced intellectual navigation in this continuum include Deere and De Janvry (Citation1979), Shanin (Citation1983), McMichael (Citation2008), Isakson (Citation2009) and White (Citation2018). Looking at the historical dynamics of agrarian change in Java, Indonesia, White (Citation2018: 1108) observed that: ‘Rural differentiation and concentration of landholdings are […] established facts; however, this has produced not a capitalist large-farmer class but growing numbers of share tenants, as the landowning "masters of the contemporary countryside" parcel out their land in minuscule plots to share tenants’. He concluded: ‘Understanding the continuing existence of this highly productive and pluriactive mass of micro-farmers requires concepts derived from both the Marxist and the Chayanovian traditions’. Or, as van der Ploeg (CitationForthcoming, 1) suggests, ‘The work and life of Alexander Chayanov are narrowly interwoven with both the Russian peasantry of the early twentieth Century and the October Revolution of 1917’. According to van der Ploeg (ibid.), Chayanov was involved in helping ‘organize the Russian peasantry into a dense web of cooperatives […] and was active in outlining the land reform. He was convinced that Russian peasant communities (and their cooperatives) could operate as important drivers for the transition towards socialism’. He continues:

As a critically engaged scholar, Chayanov also developed a theory on the organization and development of peasant agriculture. He considered this theory, grounded on the specificity of the peasant farm, as being in line with (if not as being a further unfolding of) Marxist theory. Leninists of that time (and later the followers of Stalin) considered this to be not the case. For them the Chayanovian approach was an expression of repudiable ‘populism’. Today, though, its value and relevance are widely recognized, and the approach itself has been enriched, not only through research, but also, and especially, with new achievements created by peasant movements all over the world. (ibid., original italics)

Internationalism

Decolonizing and democratizing the global academy are elements of ‘internationalism’, the third defining feature of Critical Agrarian Studies. Interpreting the world in order to change it does not only pertain to the object of research, the agrarian world (out there); it also applies to the very institutions of knowledge generation, attribution, circulation and use that include the global academy (Castree Citation2000; Derickson and Routledge Citation2015; de Jong et al. Citation2017). Those engaged in Critical Agrarian Studies aspire to be truly internationalist by contributing to decolonizing and democratizing the field and the academy more generally. And that challenge, despite initial gains, remains enormous and daunting. It is not that internationalism is unique to contemporary Critical Agrarian Studies – classical agrarian studies was also internationalist – but the internationalism that contemporary agrarian studies requires is different.

The traditional agrarian studies context into which JPS was born, politically embedded within its time, was internationalist in orientation. That community sympathized with various communist and socialist political projects and anti-colonial liberation movements. Unavoidably, the internationalism that emerged in practical politics during that time, and was in part internalized in subsequent radical scholarship, mirrored to some extent the divisions of the Cold War: First World, Socialist Bloc, and the so-called Third World. Among orthodox Marxists, it mattered at that time whether one was Moscow-aligned, Trotskyist, or Maoist. Many radical agrarian studies scholars were also part of solidarity organizations in the Western world working in support of national liberation movements or socialist projects. For example, in the 1970s, Teodor Shanin and Hamza Alavi were both fellows of the Amsterdam-based think tank, the Transnational Institute (TNI).

It is important for us to clarify two broad types of internationalism in agrarian studies. The first is a largely North Atlantic-based community of radical scholars deeply committed to internationalism, and doing great solidarity-oriented, world-class radical scholarship. This was typical of the early agrarian studies, and the first decades of JPS. The second type of internationalism is a polycentric global community of scholars with a much greater and more active participation of researchers from and in the Global South. This is characteristic of contemporary Critical Agrarian Studies and the current JPS: it is internationalist in both its orientation and its composition.

JPS has made some modest contributions to building an internationalist field. For example, in 2019, and in collaboration with ISS in The Hague, COHD of China Agricultural University in Beijing, and PLAAS of the University of the Western Cape, JPS organized the first Annual Writeshop in Critical Agrarian Studies and Scholar-Activism, held in Beijing. It aimed to provide training to young researchers from and in the Global South, through a crash course on key theoretical debates in the field, and to scrutinize the politics of global circuits of knowledge (generation, attribution, circulation, exchange and use). It also sought to build social and cultural capital by creating a global network and by addressing practical issues about writing and publishing that are more familiar in Global North institutions. The Writeshop has since become an annual event, with an average of 55 participants each year. Those who have completed the Writeshop have self-organized into the Collective of Agrarian Scholar-Activists in the South.Footnote31 JPS has always aspired to include significant participation from the Global South, from young researchers, women and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color), civil society organizations and agrarian movements.

In addition, JPS has partnered with several international research networks and launched competitive calls for small grants to produce research papers, supported by the research project and institutional funds of the network members, and targeted primarily at young PhD and post-doctoral researchers, internationally. This has resulted in a number of small grants of between US$1,000 and US$2,000 being awarded. The multiplier effects of this have been extraordinary in terms of research output.

One of the biggest barriers to democratizing and decolonizing the academy is the dominance of the English language, with very limited meaningful interaction and cross-fertilization between Anglophone agrarian studies on the one hand, and non-English traditions in agrarian studies (with a few exceptions such as the long-standing agrarian studies traditions of Mexico, Brazil and Colombia) on the other. An English-language journal, JPS has nevertheless sought to address the deeply undemocratic terrain in knowledge generation, attribution, exchange and use by organizing and/or supporting language and translation initiatives. The latest such efforts are the joint initiative by JPS, TNI, CASAS and others in launching the Agrarian Conversations (AC) webinar series in 2020 that runs in multiple languages, and supporting simultaneous interpretation at international conferences, including the 2022 online conference on climate change and agrarian justice that attracted 2,200 registered participants and provided simultaneous translations in English, Spanish, French and Burmese.

Another important element in knowledge politics is a researcher's ability to circulate within and across the global circuits of knowledge. This means participating in important international conferences and workshops, as well as gaining membership to associations that are relevant to one's discipline and field. But these entail monetary costs that most Global South-based researchers, especially doctoral students and early career academics, cannot afford. And for those who manage to secure funding to participate in international conferences and workshops, securing a visa to many countries may prove to be too difficult. The discrimination that one faces in many consulates and embassies, and the emotional pain of having prepared for an international conference only for the visa application to be rejected, are everyday realities of oppression for countless researchers from and in the Global South, and BIPOC more generally, that are often invisible to privileged academic researchers from richer countries and/or better-funded universities.

The JPS initiatives enumerated above aspire to make the global academic terrain less discriminatory and unjust. They are always developed in collaboration with allied institutions and networks, and in dialogue with radical social movements, and they have achieved some major and inspiring successes. But they are not easy to orchestrate, and the logistics are extremely challenging. Moreover, while relevant and important, these efforts remain miniscule compared to the enormous task of decolonizing and democratizing the field and the global academy.

Knowledge circuits in Critical Agrarian Studies remain undemocratic and inequitable. Basic data from JPS shed light on this. In the Journal Citation Record (JCR) of Clarivate Analytics based on Web of Science, JPS has ranked #1 for most years during the past decade in the categories of Anthropology and Development Studies. For the period 2012–2021, aggregated data for JPS from Web of Science on aspects of knowledge generation, attribution, circulation, exchange and use show that these domains are largely monopolized by researchers and institutions in rich countries. I purposely limited the timeframe to the past 10 years for two reasons: it is the period in which statistics on manuscript submissions and usage reflect the Critical Agrarian Studies period in JPS, after the shift was made in 2009, and it is also the period in which journals became more or less fully digitized, with far-reaching impacts on manuscript submissions and usage.

On knowledge generation and attribution. Governments of rich countries have invested heavily in scientific research grants for scholars based there, not least in an effort to entice researchers from other places to migrate to their countries. In addition, universities in rich countries are generally well funded (or at least better funded than their counterparts in developing countries), their libraries well supplied, and their academic staff generally better paid than their Southern counterparts – as well as being entitled to compete for generous research grants. The overall effect of this material disparity is that formal academic knowledge and claims to authorship are monopolized by researchers based in rich, mostly Northern countries.

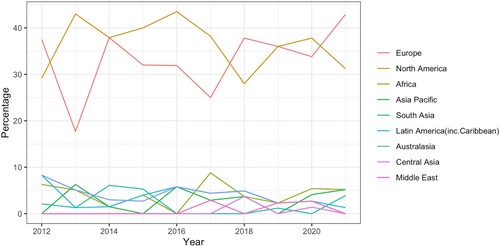

shows that the three regions in which the majority of authors submitting to JPS in this period were located were the following: Europe (34%), North America (21%) and Asia Pacific (13%, the bulk of which is accounted for by submissions from China). Combined, the total share of these three regions was 68%. It is no exaggeration to suggest that in Critical Agrarian Studies, subjects and settings of research are largely located in Africa, Latin America and South Asia. Yet, the shares of these three regions in terms of authorship were relatively small: Latin America 7%, South Asia 8% and Africa 10%, for a combined share of only 25%. The pattern is similar in terms of geography of published corresponding authors. shows that, by region, Northern America and Europe accounted for the lion's share, while the remaining regions of the world contributed a much lower and more or less unchanging proportion.Footnote32

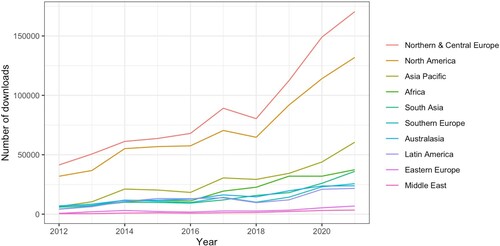

On knowledge circulation and use. The closely related sphere of knowledge circulation and use demonstrates a similar pattern, with access to knowledge far more widespread in rich countries and regions than their Southern counterparts. Some evidence of this is provided by statistics on article downloads. It is noticeable in that the volume of downloads has increased in all regions during the past decade, but the rates of increase in Northern and Central Europe, North America and Asia Pacific have been markedly higher than the other regions. is based on a dataset which shows that a total of 71% of all JPS article downloads in 2012–2021 were in these regions: Northern & Central Europe, Southern Europe and Eastern Europe (39%), North America (27%) and Australasia (6%). This contrasts with the small share of downloads in Africa (7%), Latin America (5%) and South Asia (5%), for a combined total of only 17%. It is a picture of absurdly lopsided distribution of access to formal scientific knowledge.

If we disaggregate the statistics down to the level of institutions, then the inequity in global knowledge circuits is even more vivid. In 2012–2021, for JPS, the top 25 research institutions accounted for total combined downloads of 0.43 million (16%) of the total global downloads of 2.7 million. This is 25 research institutions located in eight rich countries out of 19,800 higher education institutions in 196 countries included in the World Higher Education Database (WHED). In other words, 16% of all JPS downloads in this period went to just 0.12% of all registered higher educational institutions, in 4% of all registered countries. One requirement for manuscripts to get accepted for publication is that they must include or add to state-of-the-art knowledge. But if you are a researcher in a poorly funded university that has no subscriptions to important journals and books, how could you even know what the state of the art in your field or topic is, let alone go beyond it?

What the 10-year JPS data show is that the structural and institutional terrain remains profoundly neocolonial and undemocratic, and efforts to decolonize and democratize this sphere – such as the numerous initiatives associated with JPS – have yet to make any significant dent. This task is huge, especially because the latest developments in global publishing are likely to reinforce, not erode, such inequitable patterns of knowledge generation and use. One of the institutional mechanisms that might inadvertently reinforce the undemocratic structure of knowledge circuits is the ‘Gold Open Access’ institutional arrangement, by which the individual author, university, funding agency, or national government pays a publisher to make an accepted manuscript permanently available through open access. Only well-endowed researchers or well-endowed universities in rich countries can afford the high costs of such an arrangement. Some national governments have invested huge sums of money in institutional arrangements for open access publication for all researchers based in their countries. These investments are at a level that few countries can afford. At the time of writing, only a handful of countries have institutional contracts with Taylor & Francis (publisher of JPS), such as Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. This institutional arrangement privileges a tiny minority of researchers. It will not only sustain the differentiation among researchers worldwide, but it is likely to sharpen disparities.

In sum, this brief analysis of the field through an internationalist perspective and in terms of knowledge politics reveals an extremely inequitable and undemocratic institutional state of affairs. The bleak picture pertaining to the field of Critical Agrarian Studies and the case of JPS is not exceptional: unfortunately, there are indications that this analysis is generalizable. In an important study, Carmen Diana Deere analysed the issue of academic research excellence more broadly, focusing on Latin America, and found exactly the same pattern of inequities and hierarchies that I have flagged here (Deere Citation2018). Ultimately, global circuits of knowledge generation, attribution, circulation and use are mutually reinforcing: access to formal academic knowledge (in publications and other formats) boosts scholars’ ability to generate knowledge and claim authorship, especially in formal publications. The converse is also true: the absence of access to formal academic knowledge renders academic researchers weak and vulnerable in global knowledge politics. Thus, to be an internationalist in Critical Agrarian Studies today is not only to carry out tasks from the North in solidarity with marginalized colleagues in and from the Global South, but in addition, and perhaps even more importantly, it is to help dismantle the very social structures and institutions that cause and sustain inequity in global knowledge circuits. Brilliant and radical ideas are produced, and centers of teaching and research excellence are constructed, in deeply undemocratic, neocolonial and disempowering structural and institutional settings. These are everyday realities in the world today – but it is a status quo that the growing global community of Critical Agrarian Studies refuses to accept, increasingly challenges, and endeavors to radically erode through subversive ways of producing, sharing and using knowledge.

Critical agrarian studies: a dynamic, evolving field

The list of important academic research accomplished by Critical Agrarian Studies is long, and much of it has been referred to in this paper. But if we were to construct a list of what remains to be done to make the field fully attentive and responsive to every important aspect of the actually existing world, including those that remain under-researched, that list would be much longer – and the intellectual deficit of Critical Agrarian Studies would be clear.Footnote33