ABSTRACT

Using a recently re-discovered text by Alexander Chayanov, this article argues that while demographic differentiation may lead to stratification, this is, for a variety of reasons, mostly temporary and does not generally result in the formation of antagonistic rural classes. At the same time there is also the far more deep-rooted phenomenon of market-induced differentiation. This latter type stems from, and reflects, capital’s ability to create and bridge price differentials, mostly through long-distance trading and food engineering.

In reality no theory ever gets completed, even if its believers think differently. This is a universal truth, but especially so for the work of Alexander Chayanov, an engaged Russian scholar who was an important figure during the Russian October Revolution in 1917, playing a dual role in this seismic event. On the one hand, he aligned the Russian peasantry with the revolutionary movement, simultaneously trying to assure that the revolution also benefitted those working in the countryside. On the other hand, he elaborated a theoretical approach that allowed for a better understanding of the organization and development of peasant agriculture. This approach was many-sided, comparative and comprehensive. It had multiple foci, examining the level of the single peasant farm, intermediate phenomena (such as regional markets and cooperatives) and macro issues (such as the position of the peasantry within capitalism). However, the tragic events occurring in the aftermath of the revolution meant that Alexander Chayanov was not able to finish his theoretical work as his life was abruptly and brutely interrupted.

The incomplete nature of his work is particularly evident when it comes to the issue of social differentiation. The notion of differentiation figures at two levels in his theoretical work. First, at the level of the single peasant farm and family and, second, at the level of the agrarian sector as a whole. The two manifestations are not interlinked, although they both contribute to the confusing, and often misunderstood, heterogeneity of agriculture. Disentangling this heterogeneity (or at least parts of it) is precisely what unites and differentiates the Leninist and Chayanovian approaches.

The demographic cycle

At the micro level the key phrase is demographic differentiation. This refers to, what we now call, the economic size of the peasant farm. In Chayanov’s time this coincided with the area (expressed in e.g. desiatinas or hectares) worked by the peasant family – at least in Russia where land was abundantly available and regularly redistributed by the peasant communities (mirs) themselves This set Russia apart from Western Europe at that time where, as Chayanov noted, it was not the physical amount of land but the intensity of land use that determined the economic size of a single peasant farm. Be that as it mayFootnote1, the economic size of Russian peasant farms differed considerably: alongside small farms there were larger ones and, as always, there were those in-between; the medium farms. This difference affected peasants’ wellbeing. For small farmers, poverty was never far away: they had to work hard to maintain their families. Drudgery (a canonical concept from Chayanovian analysis) was an everyday reality. Their opposites, the large farmers, were relatively well-off and signs of richness (even timid ones) were often displayed. The farmers working medium-sized surfaces were neither poor, nor rich, but somewhere in-between.

The distinctive element in Chayanov’s analysis is that he relates (and thus explains) these differences mainly, though not exclusively, through the demographic cycle of the peasant family. Hence demographic differentiation. When a young couple married (as they did at that time in Russia), started working their own small farm, and got children, they had to work hard in order to feed the family. And as the number of children increased they necessarily had to enlarge their farm in order to make ends meet. Technically speaking: the ratio of hands to do the work and the mouths to be fed was constantly changing and this drove the peasant family. After a certain point, as the children grew up, they added to the farm’s labor force so that a larger area could be worked, just as a modest surplus might be transformed into some degree of well-being. However, sooner or later, the parents necessarily had to make their final voyage and the domus (the unity of family and land) was divided among the heirs. Thus the cycle started anew. Consequently, being ‘poor’, ‘in-between’ and ‘well-off’ (just as having small, medium and large areas of land available for working) were stages of life and the knowledge that after each stage there is another one was an invisible glue that tied peasant communities and families together.

In synthesis: according to Chayanov’s analysis, there is, and always will be, stratification within peasant societies (see also Netting Citation1993 and van der Ploeg Citation2013). There are different strata (small, medium, large; poor, middle, rich). This stratification is produced by the demographic cycle; and the same cycle turns the different strata upside down, over and again, intermingling them – even to the degree that you never know exactly who is about to enter the ballroom and who is leaving. Ironically, this is reflected in the literature itself. Differences in farm size and family wellbeing have been interpreted as definitive indicators of class differentiation (Bartra and Otrero Citation1987), demographic differentiation (White Citation2018) or understood as an expression of both (Deere and de Janvry Citation1981). In particular situations, some authors have identified a trend towards class differentiation whilst others have refuted such an interpretation (see Akram-Lohdi Citation2005 and Trang Citation2010, respectively). Anyway, to read stratification in an a priori way as an expression of class formation is clearly wrong (see also Shanin Citation[1977] 1990, 59; Netting Citation1993, 231). Chayanov accepted that there might be such social differentiation at specific times and in specific places. However the mere presence of socio-economic differences (i.e. the presence of different strata) can never be taken as a linear, one-way, indicator of social differentiation as conceptualized in Leninist theory (Cousins Citation2022). Only careful empirical research (preferably grounded on time series and applying diachronic analysis) can reveal the different and interacting processes that contribute to, and result in, the often impressive and, at first sight, highly confusing diversity of farms, farming and agriculture.

Iso-prices: an almost forgotten, but still highly useful concept

Concerning the second level – agriculture as a whole – Chayanov demarcated pre-revolutionary Russia (where peasant agriculture existed alongside landlords and capitalist farmers) from the post-revolutionary situation, just as he clearly distinguished farming in the Soviet economy from farming in e.g. the USA.Footnote2 He was aware that time and space were very important. ‘To correctly raise the question and get relevant answers, we have to accurately and thoroughly study every single case to find out what kind of differentiation processes we are observing [… .] and how to place [them] in the […] national economy of the country under study’ (Chayanov Citation1927 in Nikulin, Trotsuk, and van der Ploeg Citation2023; italics added).Footnote3 John Harriss (Citation1982, 180) synthesized this far later saying that ‘purely structural conceptions of causality’ are to be avoided.

In the USSR of 1927 ‘we have neither large, nor medium sized, capitalist farms in agriculture’ (Chayanov Citation1927 in Nikulin, Trotsuk, and van der Ploeg Citation2023). Nonetheless, there were considerable segments of the rural population and extended areas characterized by poverty, enslaving forms of exploitation, the abandonment of farms and migration. This raised a question that is still very relevant today: ‘As a result of [this kind of] differentiation, will we have the professional proletariat that completely abandoned agriculture or the new workers who are our old friends – semi-peasants/semi-workers – who maintain relationships with their villages?’(ibid.).Footnote4

Be that as it may, there evidently was (just as in our times there still is) a ‘complete discrepancy’ between the social, the economic and the ecological. In Chayanov’s time this was partly related to the shift from subsistence economies to a market economy. In our times it is related to global capitalism permanently extending its many frontiers (Beckert et al. Citation2021). Thus, discrepancies are continuously produced in more and more areas. These generate complex inter and intra-regional forms of differentiation.

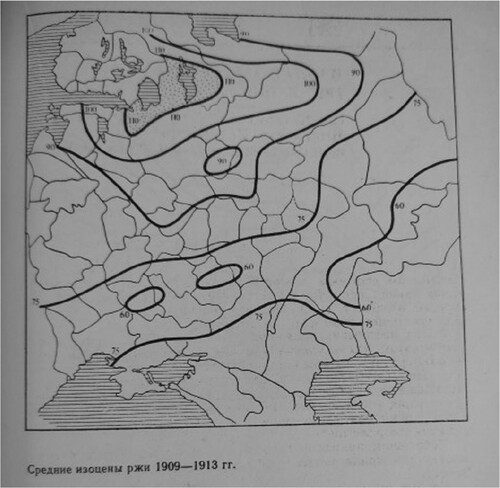

The key concept that Chayanov proposes for the analysis of ‘this kind of differentiation’Footnote5 is iso-prices.Footnote6 Iso-prices are lines that connect places with the same price for a specific product.Footnote7 shows such iso-prices for rye in Russia before the First World War (Chayanov also elaborated similar cartograms for the autumn of 1917 and the spring of 1920).Footnote8 The figure shows that, at that time, north-western Russia (the region around Saint Petersburg) experienced the highest price-level for rye (100 Rubbles or more), whilst in the south and the south-east there were pockets with price levels of 60 or less.

Iso-prices are an indicator that are hardly used anymore and one might wonder how they possibly relate to the issue of differentiation. However, a careful reading of Chayanov’s exposé renders intriguing insights that offer great promise in the analysis of contemporary agriculture.

First, Chayanov clearly argues that ‘a subsistence economy excludes iso-prices’. If peasant production is not market-oriented, there will be no market, nor price and, consequently, no iso-prices. One the other hand, when markets emerge and production becomes market-oriented, there will be prices and thus (probably) also iso-prices.

This brings us to the second point. What is the reason for these iso-prices? They exist because, at the local and/or regional level, prices will reflect different scarcity relations between supply and demand – that is between the capacity and willingness of peasant farmers to produce and deliver agricultural products and the needs and purchasing power of non-agrarian (mostly urban) populations. The sides of this balance are rooted, in complex ways, in population density and distribution, ecology, history, town-countryside relations, associated power relations, and so forth. And with variations in these webs of underlying reasons, relations and flows, scarcity relations will vary and thus, at an inter-regional level, iso-prices will emerge.

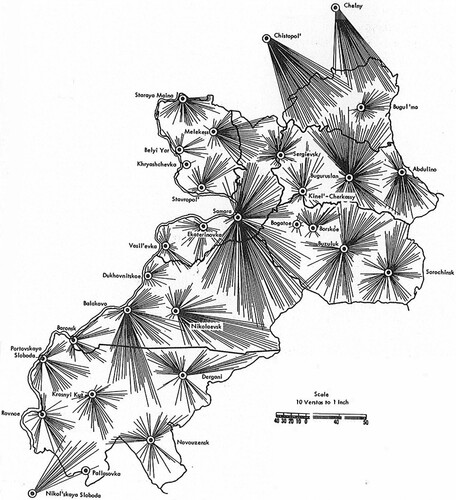

Thirdly, it is evident that the existence of iso-prices will trigger trade. But such trade (bringing food commodities from ‘cheap’ to ‘expensive’ areas) does not eliminate these iso-prices. Interregional (or long-distance) trade comes with transport costs, the costs of trading, and transaction costs (i.e. the cost of using the market). Thus a decentralized pattern of semi-independent, but interlinked, regional markets emerges within which the production and consumption of food are largely (though not exclusively) regional and mutually interdependent. This is reflected in (derived from the work of Chayanov [Citation1923] Citation1986, 259).

It is important to take into account here that regional markets and the phenomenon of iso-prices do not belong to a remote past. Of the total amount of food produced and consumed in the world today 84% never crosses national boundaries. It is produced and consumed within one and the same country – and most production and consumption are proximate in terms of distance (less than 20 kilometers apart). This does not exclude, however, the parameters set by the world market having a strong impact upon regional markets.

Take for example the EU, within which there is, formally speaking, one milk market. Nonetheless, there are considerable and significant iso-prices. In the year 2002 these ranged from 0.26–0.36 Euro/kg. of milk (farm gate price), with consumer-prices (for 1 L of UHT milk, excluding VAT) ranging from 0.51–1.12 Euro (in the same year). The farm gate price as a percentage of the consumer-price varied between 23 and 61% (Unalat Citation2002, 25). These regionalized processes of price-formation were explicitly institutionalized in some parts of the world. In this vein Italy had, up to the end of the 1960s, zone bianche: ‘white zones’ that combined a gravitational center (an urban conglomeration) with its surrounding agrarian hinterland (as in ). In the framework of these zone bianche the farmers and labour unions (the latter representing consumers) met yearly to negotiate and agree upon the milk price. Consequently, the milk price paid in Milan differed from the one paid in Reggio Emilia, whilst the one in Bologna was at yet another level.Footnote9 Without going into detail, I observe here that several social movements are currently trying, once again, to actively restore and manage specific price levels (that differ markedly from prices paid elsewhere).Footnote10

Iso-prices can be made to disappear, just as they can re-emerge. Current food regimes actively construct and exploit places of poverty that they then link to places of richness through long-distance trade.Footnote11 Food engineering, which allows for bridging huge distances in time and space,Footnote12 and control over infrastructure (ports, processing plants, etc.) are strategic here. Thus, food empires are constantly expanding the frontier that is used to feed capital accumulation.

The non-emergence of capitalist farmers

Capital makes food products flow from one side of the iso-curve to the other (preferably bridging gaps that are as wide as possible), with the effect of lowering farm gate prices in relatively well-off regions. This flow both induces and explains an important politico-economic process: the impoverishment of the peasantry without any simultaneous ‘accumulation from below’. Impoverishment induces a many-facetted stratification: peasants losing their land, some of them migrating to the cities (mostly to live the life of human garbage as the Brazilian expression goes), yet others try to defend themselves through all kinds of handicrafts, etc. But there is no simultaneous emergence of capitalist farmers (i.e. rich peasants becoming capitalist farmers employing wage workers) – at least, not in a generalized way. This is because the induced price reductions virtually exclude profit-making at the level of single farms.Footnote13 If anything, the international food trade (as organized by the current food empires) generates a very specific kind of class-dynamics. On the ‘poor side’ of the international trade chains we witness the marginalization of peasantries and the emergence of large-scale capitalist farm enterprises controlled by large non-agrarian capital groups. However, these new enterprises are definitely not the result of any ‘accumulation from below’, as Leninist approaches would have it. In this vein, Ben White noted, in a study in Indonesia, that ‘rural differentiation and concentration are established facts; however this has not produced a capitalist large-scale farmer class’ (2018:1108; italics added). Instead, land-grabbing is the key phrase to understanding their spread throughout the Global South. On the ‘rich side’ a similar crippled type of differentiation can be seen: ‘one side is operational, the other not’. Poor and middle peasants are outcompeted but, some exceptions apart, there is no coherent and generalized transition of ‘rich peasants’ into ‘capitalist farmers’. To give just a few references: At the beginning of this twenty-first Century, Europe as a whole (EU28) had a total of 12,248,000 farms. Of these, 11,885,000 (i.e. 97%) were classified as family farms (FAO Citation2014). Equally, in France only 3% were classified as capitalist farms (Laurent and Remy, Citation1998), whilst in Italy it also oscillates around 3% (ISTAT Citation2010 and Citation2022), a sharp decrease compared to the first decades of the previous century (Sereni Citation1979).

Iso-costs

Alongside iso-prices one can also discern iso-costs. These refer to (and summarize) the variable and fixed costs that occur in agricultural production. Peasant production is grounded on a relatively autonomous resource-base. Most inputs and factors of production are produced and reproduced within the farm (or region). Through many different processes, though, this resource-base is being eroded and thus ‘world’s agriculture is being [… ] drawn into the general circulation of the world economy, and the centers of capitalism are […] subordinating it to their leadership’ (Chayanov [Citation1923] Citation1986, 257). Alongside its presence on the downstream side of the peasant farm, the ‘trading machinery’ (ibid:258) also appeared on the upstream side. And again the effects were, and are, two-tiered. First it is most likely that the quantitative relations between means of production within the peasant farm do not correspond with the prices of capital and labour in the reigning markets.Footnote14 Thus, problems of relative overpopulation suddenly come to the fore (see e.g. Chayanov in Nikulin, Trotsuk, and van der Ploeg Citation2023). Second, new forms of stratification emerge as a result of the commoditization of the resource-base being an unequal and non-linear process (Nemchinov [Citation1926] Citation1967; Shanin Citation[1977] 1990, 234–242; van der Ploeg Citation2010) that translates into important differences in the intensity and scale of farming. Thus, the stratification brought about by, and through, differential commoditization, extends to differences in farming styles (as Salamon Citation1985; Goldschmidt [Citation1947] Citation1978; and Strange Citation1988 have shown to be the case in the USA).

The rule: stratification but no class differentiation

All this can be synthesized in the thesis that mostly peasant societies are characterized by a many-sided stratification but lack a generalized and consistent trend towards class differentiation. There is a possible theoretical line of reasoning that helps to sustain such a thesis. Alongside this there is an important, empirically induced, argument that, I think, further supports this thesis (or ‘rule’).

Bernstein (Citation2020, 36) is right when he argues that the discussion of peasant class formation (and, consequently, the exploration of differentiation) requires ‘a theoretical framing’. Such framing has been convincingly developed by Thiemann (Citation2022) who characterizes, after a careful re-reading of Marx, the peasantry as (part of) ‘the third class’. Instead of being made up by the combination of contradictory class segments (capital and wage labour) – a combination that is inherently unstable and necessarily deemed to dissolve into separate elements – the ‘artisan’ is ‘a general class of labour [that represents] an antonym to the proletarian condition and [which operates] the means of production as patrimony rather than capital’ (2022: ix). The labour process here is grounded on, as much as it provides, relative autonomy, self-direction and possibilities for emancipation (op. cit., 6). ‘Artisans [peasants included] have control over or effective access to the means of production and are thus in a position to self-direct their labour. [Consequently], the artisan is the class which innately opposes ‘the process which divorces the producer from the ownership of the conditions of his own labour’’(Thiemann Citation2022, 13; italics added). Such opposition is possibly further strengthened by the nature of agricultural production, as suggested by Mann and Dickinson (Citation1978) (but criticized by Mooney Citation1982 and later on by Toledo Citation1990) who argue that the labour process in agriculture is an encounter with living nature, which makes the systematic separation of manual and mental labour and the inevitable recourse to wage labour relations highly improbable.

The innate opposition to differentiation, as hypothesized by Thiemann, is supported by, and reflected in the institutional patterns (Ostrom Citation1990; Diez Hurtado Citation1998; Lucas, Gasselin, and van der Ploeg Citation2019), infrastructures (Boelens Citation2008), historically created landscapes (van der Ploeg Citation2022) and cultural repertoires (Hofstee Citation1946) that one finds in peasant societies. Such repertories, for instance, explicitly discourage, disapprove and, even, actively hinder growth at the farm level that goes beyond the potential of farm and family – and this is especially the case when such growth starts to threaten the continuity of other peasant farms and families (for ‘traditional’ cultures see e.g. Foster Citation1965 and Berger [Citation1979] Citation2014 and for ‘modern’ repertoires e.g. Ortiz Citation1971 and Rooij, Brouwer, and van Broekhuizen Citation1995). Cultural repertoires thus inhibit the materialization of differentiation as a social reality. In this respect cultural repertoires come to the fore as crucial elements of ‘superstructure’ – reflecting and reaffirming the structure, consistency and endurance of the ‘third class’.

The theoretical framing of the peasantry as part of the third class does not, of course, exclude the possibility of stratification. There always are some peasant families getting far richer than others whilst running far larger farms, just as there are others becoming impoverished. Equally, there is bound to be a division of labour and dependency relations between the different strata as well. But such differences and dependencies are contained through cultural repertoires. This explains why the differences that show up at one moment in time, do not result in perpetual linear processes that result in ever-widening gaps (as shown for e.g. yields by Zachariasse Citation1979). Within peasant agriculture being or becoming ‘rich’ is a biography with a clear beginning as well as a clear end. The same applies for being poor. Both emerge and then dissolve. Upward mobility (which clearly contributes to stratification) is followed by downward mobility (Shanin Citation[1977] 1990, 216–218). In peasant agriculture, mobility is cyclical, with some families moving upwards and others downwards (Edelman and Seligson Citation1994; IFAD Citation2010). In the next generation’s time these processes will probably be reversed. This occurs in countries as diverse as China and the Netherlands: some small peasant-like farmers disappear, while others grow. At the same time, some large entrepreneurial farms are eliminated and their resources become available and may be partly used by local peasants who want to enlarge their farm and/or by new entrants seeking to establish themselves as new, small and peasant-like farmers (Huang Citation1985, 169; Ploeg, Citation2018, 501).

Exceptions to the rule

Although there is no general tendency of rich peasants converting themselves (through a process of accumulation ‘from below’) into capitalist farmers, there are specific pockets where such a transition is occurring. These need to be explained by looking at the specificities of time and place. There still is much research to be done, but some ingredients of such an explanation can be suggested here. Typically, such transitions frequently occur by crossing the iso-curves Chayanov was referring to. That is the story of relatively rich Western European farmers moving into the USA where they can obtain cheap land and contract cheap Mexican workers for their enlarged farm enterprises. The same applies to large growers of fruits and vegetables in the southern part of Europe who can contract poor and often illegal labour migrants from Sub Saharan Africa (and to large horticultural producers in the Netherlands and elsewhere in NW Europe employing cheap migrant workers from Eastern Europe). Crossing the iso-curves and moving to cheap landFootnote15 and/or cheap labour is generally the key to these processes. Yet another case occurs when peasant farmers change into agricultural entrepreneurs (through increased degrees of commoditization, especially when supported by the state through modernizationFootnote16 and Green Revolution programs) who, under special circumstances (e.g. long-run security regarding farm-gate prices and the availability of cheap credit) are spurred to make the step towards capitalist farm enterprises build on the expanded use of wage workers. However, cases like these are the exception rather than the rule (which does not imply that they are without political relevance). Wherever the role of living nature in agricultural production can be strongly reduced (through an artificialization of nature, such as e.g. genetic modification), the probability of agricultural production being organized as capitalist enterprise increases.

The intertwinement of different forms of differentiation

Market-induced differentiation does not come ‘alone’, just as Ben Cousins observes for class differentiation (2022:1394). It is intertwined, in many different and complex ways, with other forms of differentiation (e.g. gender, generation, race, religion, class and caste) that, together, result in constellations in which one form of differentiation feeds into (or prevents) another. Thus, religious differentiation, for instance, might support or even induce new patterns of class differentiation (as documented by Moerman Citation1968 and Long Citation1977), whilst small farmers working for large farmers may help to avoid the ‘disappearance’ of the former (as occurred in large parts of north-western Europe in the post-WW2 period).

Slotting market-induced differentiation into the analysis of such complex, heterogenous and constantly moving constellations has at least three benefits. Firstly, it inevitably extends the analysis (including class analysis) to the global level. Secondly, it explains why the expected effects often do not materialize in the spaces where we might expect them, but crystallize in other, far-away, spaces. Thirdly, it helps to us understand how capital evolves by, and through, a range of essentially non-capitalist forms of differentiation – sometimes even actively enlarging them.

Market-induced differentiation has, as already noted, differential effects. When different agricultural constellations (each with its own particular levels of scale, intensity, income-generating capacityFootnote17, accessibility, etc.) are systematically interlinked through one single market – if, in other words, iso-prices are eliminated and simultaneously reproduced – the effects will be highly diversified (see also Mazoyer and Roudart Citation2006). This is accentuated when the development of agricultural technologies is biased, in the sense that their design is more suited to some constellations and represents a significant rupture with others.

Market-induced differentiation and peasant politics

Peasant struggles contain a range of potential responses that may allow the peasantry to avoid the devastating effects that can result from intertwined processes of differentiation. Food sovereignty is a prime example as it aims to re-regionalize both the production and the consumption of food and rejects free trade as an ordering principle. Food sovereignty uses local and regional marketplaces to tie production and consumption together, and represents an institutionalized alliance between rural and urban people. This leads to food markets becoming nested in a mutual understanding between peasant producers and urban consumers (Ploeg, Ye, and Schneider Citation2012). Food sovereignty does not exclude inter-regional marketing – it grounds it upon ecological principles: only produce that is lacking may come from elsewhere whilst surpluses are only traded into other marketplaces that are experiencing shortages (this is the principle underlying e.g. the Brazilian Ecovida network). A second response is peasant-managed cooperatives, which govern both the operation of local and regional markets and interregional trade. They also play an important role in enlarging and sustaining the autonomous resource base that upholds peasant production. Agroecology is a third pillar: which both further strengthens the resource-base and promotes the rich diversity of food (and other products and services) needed in local and regional markets. A fourth response is a change in technological development. Instead of centering on off-the-shelf magic bullet solutions such as genetic modification and automation, it puts ‘man and living nature’ center stage again and contributes to their co-evolution –as advocated in the agroecological agenda. And last, but far from least, farming, small-scale processing and local marketing are (once again) to be made as attractive as possible, especially for women and young people.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Sasha Nikulin and Igor Kuznetsov for providing me with crucial insights and rich background information.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2023.2179164)

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jan Douwe van der Ploeg

Jan Douwe van der Ploeg is Professor Emeritus of Wageningen University in the Netherlands and Adjunct Professor in Rural Sociology at the College of Humanities and Development Studies of China Agricultural University in Beijing. He is the author, most recently, of The Sociology of Farming: Concepts and Methods. Previously he wrote, among others, Peasants and the Art of Farming: A Chayanovian Manifesto.

Notes

1 The funny detail, of course, is that the Leninist classification scheme of small, medium and large (peasant) farmers could only be operated in Russia because the magnitude of the land being worked could easily be assessed. If not directly, then indirectly by the number of horses used for working the land: no horses meant a poor peasant; having one horse translated as being a medium-sized peasant producer; and three or more horses implied being a large and rich farmer, a kulak. If there had been structural differences in the levels of intensity this simple mathematics of the ‘revolution’ would have failed even more than it actually did. The other side of the equation is that the same classification scheme has never been well-understood and accepted, let alone effectively operated, by emancipatory movements in the Western European countryside. It simply did not fit very well. It did not reveal what it was meant to unravel (i.e. to distinguish poor rural workers from rich capitalist farmers).

2 See e.g. ‘Letter from A.V. Chayanov to V.M. Molotov on the current state of agriculture in the USSR compared with its pre-war state and the situation in agriculture of capitalist countries (October 6; 1927)’ in Nikulin, Trotsuk, and van der Ploeg Citation2023

3 At the time of writing Nikulin, Trotsuk, and van der Ploeg Citation2023 was not yet available in printed form. Thus I am unable to give page numbers.

4 The relevance of this early observation is revealed by the circular movement of migrant workers (from countryside to town and then back again) in China. See Ploeg and Ye, Citation2010.

5 There is one text (recently translated and re-published in the English language) explicitly dedicated to the discussion of differentiation (‘On differentiation of the peasant economy’ in Nikulin, Trotsuk, and van der Ploeg Citation2023). This text, first published in 1927, is a revised version of a report presented at the beginning of the same year in Moscow at a discussion on the socio-economic differentiation of the Russian peasantry, a discussion in which both the so-called ‘Marxist agrarians’ and the ‘agrarian neo-populists’ participated. See also Shanin (Citation[1977] 1990, 234).

6 I am very grateful to Sasha Nikulin of RANEPA in Moscow for having explained to me the meaning and use of this concept in the Russian academic traditions and debates of that time.

7 The concept of iso-prices and the methods for calculating them were elaborated and systematically tested for the first time by the German agrarian economist Engelbrecht. Chayanov referred to him in his ‘Lehre van der bäuerlichen Wirtschaft’ (Citation1923, 126) and, later, in his ‘Essays on the theory of the labor economy’ (Citation1924). In the latter he strongly built on the famous Russian economist Nikolay Kondratiev who discussed iso-prices related to the market for bread (Kondratiev [Citation1922] Citation1991, 448–449). I am most grateful to the Russian economic historian Igor Kuznetsov for having provided this information to me.

8 The three cartograms can be found in A.V. Chayanov (Citation1989), Peasant Economy: Selected Works, Economics, Moscow, pp 110–113, which is currently only available in Russian.

9 In the framework of the then just-created EEC (European Economic Community) this practice became forbidden as it was seen as a ‘distortion’ of the free market.

10 Theoretically important is that the movements bring about intra-regional price differences (as much as they contribute to the reproduction of inter-regional differences).

11 Long-distance trade has been, through the ages, an important prerogative of capital (Braudel Citation1992)

12 Such as making latte fresco blue, see van der Ploeg Citation2008, chapter 4.

13 This is reflected, among others, in the fact that, in macro-terms, over the years Dutch agriculture shows no (calculated) profits at all. There are just (calculated) losses. This does not exclude families generating attractive incomes from farming. The same is true for other European countries (and to family farming generally).

14 Chayanov was well aware of the theory of relative prices of production factors – a theory that was well explained in late 19th Century Russian textbooks – but he did not elaborate this aspect any further. I am grateful to Sasha Nikulin for explaining this issue to me.

15 The notion of cheap land includes the absence of environmental and/or spatial regulation (or enforcement).

16 Tellingly, modernization in West-European agriculture contained a large element of a cultural offensive, meant to eradicate the then reigning cultural repertoires.

17 Reflected in the VA/GVP ratio, i.e. the relation of Value Added (or ‘labour income’ as Chayanov called it) and the Gross Value of Production.

References

- Akram-Lohdi, H. 2005. “Vietnam's Agriculture: Processes of Rich Peasant Accumulation and Mechanisms of Social Differentiation.” Journal of Agrarian Change 5 (1): 73–116. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2004.00095.x.

- Bartra, R., and G. Otrero. 1987. “Agrarian Crisis and Social Differentiation in Mexico.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 14 (3): 334–362. doi:10.1080/03066158708438333.

- Beckert, S., U. Bosma, M. Schneider, and E. Vanhaute. 2021. “Commodity Frontiers and the Transformation of the Global Countryside: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Global History 16 (3): 435–450. doi:10.1017/S1740022820000455.

- Berger, J. (1979) 2014. Pig Earth. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Bernstein, H. 2020. “Shanin, Chayanov and Peasant Studies of Russia and Beyond.” Russian Peasant Studies 5 (4): 32–38. doi:10.22394/2500-1809-2020-5-4-32-38.

- Boelens, R. 2008. “The Rules of the Game and the Game of the Rules: Normalization and Resistance in Andean Water Control.” PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Braudel, F. 1992. The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century, Vol. II. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Chayanov, A. V. (1923) 1986. The Theory of Peasant Economy, with a new Introduction by Teodor Shanin. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Chayanov, A. V. 1923. Lehre van der Bäuerlichen Wirtschaft, Versuch Einer Theorie der Familienwirtschaft im Landbau. Berlin: Verlagsbuchhandlung Paul Parey.

- Chayanov, A. V. 1924. Ocherki po Ekonomike Trudovogo Sel’skogo Khozyaistva [Essays on the Theory of the Labor Economy], S. Predisloviem, Narodnyi Komisariat Zemledeliya, Moskva.

- Chayanov, A. V. 1927. “Letter to V.M. Molotov on the Current State of Agriculture in the USSR Compared with the Pre-war State and the Situation in Agriculture of Capitalist Countries.”

- Chayanov, A. V. 1989. Peasant Economy: Selected Works. Moscow: Economics.

- Cousins, B. 2022. “Social Differentiation of the Peasantry (Marxist).” Journal of Peasant Studies. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2022.2125805.

- Deere, C. D., and A. de Janvry. 1981. “Demographic and Social Differentiation among Northern Peruvian Peasants.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 8 (3): 335–366. doi:10.1080/03066158108438141.

- Diez Hurtado, A. 1998. Comunes y Haciendas, Procesos de Comunalización en la Sierra de Piura (Siglos XVIII al XX). Lima: Fondo Editorial CBC.

- Edelman, M., and M. A. Seligson. 1994. “Land Inequality: A Comparison of Census Data and Property Records in Twentieth-Century Southern Costa Rica.” Hispanic American Historical Review 74 (3): 445–491. doi:10.1215/00182168-74.3.445.

- FAO. 2014. Regional Conference for Europe (ERC/14/5). Rome: FAO.

- Foster, G. M. 1965. “Peasant Society and the Image of Limited Good.” American Anthropologist 67 (2): 293–315. doi:10.1525/aa.1965.67.2.02a00010.

- Goldschmidt, W. (1947) 1978. As you Sow: Three Studies in the Social Consequences of Agribusiness. Montclair, NJ: Allanheld Osmun.

- Harriss, J. 1982. Theories of Peasant Economy and Agrarian Change. London: Routledge.

- Hofstee, E. W. 1946. Over de Oorzaak van de Verscheidenheid in de Nederlandse Landbouwgebieden (Inaugural Address). Wageningen: Landboyuwhogeschool.

- Huang, P. C. C. 1985. The Peasant Economy and Social Change in North China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development). 2010. Rural Poverty Report 2011- New Realities, new Challenges: New Opportunities for Tomorrow's Generation. Rome: IFAD.

- ISTAT. 2010. Censimento Generale Dell’Agricoltura. Rome: ISTAT.

- ISTAT. 2022. Censimento Generale Dell’Agricoltura. Rome: ISTAT.

- Kondratiev, N. D. (1922) 1991. The market for bread and its regulation during the war and revolution, Nauka, Moscow (In Russian (Кондратьев Н. Д. Рынок хлебов и его регулирование во время войны и революции. М.: Наука).

- Laurent, C., and J. Remy. 1998. “Agricultural Holdings: Hindsight and Foresight.” Etudes et Recherches des Systemes Agraires et Developpement 31: 415–430.

- Long, N. 1977. Introduction to the Sociology of Rural Development. London: Tavistock.

- Lucas, V., P. Gasselin, and J. D. van der Ploeg. 2019. “Cooperation in farm work: A hidden potential for the agroecological transition in northern agricultures.” Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 43 (2): 145–179.

- Mann, S. A., and J. M. Dickinson. 1978. “Obstacles to the Development of a Capitalist Agriculture.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 5: 466–481. doi:10.1080/03066157808438058.

- Mazoyer, M., and L. Roudart. 2006. A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis. New York: New York UP.

- Moerman, M. 1968. Agricultural Change and Peasant Choice in a Thai Village. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mooney, P. H. 1982. “Labor time, production time and capitalist development in agriculture: A reconsideration of the mann-dickinson the SIS.” Sociologia Ruralis 22 (3-4): 279–292. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.1982.tb01063.x.

- Nemchinov, V. S. (1926) 1967. Izbranne Oroizvedeniya. Vol. I (n.p.),. Moscow.

- Netting, R. McC. 1993. Smallholders, Householders: Farm Families and the Ecology of Intensive, Sustainable Agriculture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Nikulin, A., I. Trotsuk, and J. D. van der Ploeg. 2023. Peasants: Chayanov’s Recovered Essays. Rugby: Practical Action Publishing. doi:10.3362/9781788532518

- Ortiz, S. 1971. “Reflections on the Concept of ‘Peasant Culture’ and Peasant ‘Cognitive Systems’.” In Peasants and Peasant Societies, Penguin Modern Sociology Readings, edited by T. Shanin, 322–336. London.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Rooij, S. J. G. de, E. Brouwer, and R. van Broekhuizen. 1995. Agrarische Vrouwen en Bedrijfsontwikkeling. Wageningen: LUW/WLTO.

- Salamon, S. 1985. “Ethnic Communities and the Structure of Agriculture.” Rural Sociology 50: 323–340.

- Sereni, E. 1979. Storia del Paesaggio Agraria Italiano. Roma/Bari: Editore Laterza.

- Shanin, T. (1977) 1990. Defining Peasants: Essays Concerning Rural Societies, Expolary Economics, and Learning from Them in the Contemporary World. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Strange, M. 1988. Family Farming: A new Economic Vision. Lincoln University of Nebraska Press.

- Thiemann, L. 2022. “The Third Class: Artisans of the World, Unite?”. Ph.D. diss., International Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University, Rotterdam/The Hague.

- Toledo, V. M. 1990. “The ecological rationality of peasant production.” In Agroecology and Small Farm Development, edited by M. Altieri, and S. Hecht, 53–60. Ann Arbor, MI: CRC Press.

- Trang, T. T. T. 2010. “Social Differentiation Revisited: A Study of Rural Changes and Peasant Strategies in Vietnam.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 51 (1): 1–119. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8372.2010.01411.x.

- Unalat. 2002. Unalat Informe, Vol. 60. Rome: Unalat.

- van der Ploeg, J. D. 2008. The New Peasantries: Struggles for Autonomy and Sustainability in an Era of Empire and Globalization. London: Earthscan.

- van der Ploeg, J. D. 2010. “The Peasantries of the Twenty-First Century: The Commoditisation Debate Revisited.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 37 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1080/03066150903498721.

- van der Ploeg, J. D. 2013. Peasants and the Art of Farming: A Chayanovian Manifesto (Agrarian Change and Peasant Studies Series, 2. Winnipeg: Fernwood.

- van der Ploeg, J. D. 2018. “Differentiation: Old controversies, new insights.” Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (3): 489–523.

- van der Ploeg, J. D. 2022. The Sociology of Farming: Concepts and Methods. London: Routledge.

- van der Ploeg, J. D., and J. Ye. 2010. “Multiple job Holding in Rural Villages and the Chinese Road to Development.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 37 (3): 513–530. doi:10.1080/03066150.2010.494373.

- van der Ploeg, J. D., J. Ye, and S. Schneider. 2012. “Rural Development Through the Construction of new, Nested, Markets: Comparative Perspectives from China, Brazil and the European Union.” Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (1): 133–173. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.652619.

- White, B. 2018. “Marx and Chayanov at the Margins: Understanding Agrarian Change in Java.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (5-6): 1108–1126. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1419191.

- Zachariasse, L. C. 1979. Boer en Bedrijfsresultaat na 8 Jaar Ontwikkeling, LEI Publicaties 3.86. Den Haag: Landbouw Economisch Instituut.