ABSTRACT

This paper examines how Malagasy dina—local-level codes considered ‘customary law’ in Madagascar—have been enrolled in competing projects of territorial production. In doing so, it engages with conversations regarding the mobilization of indigenous forms—here manifested in the guise of ‘authentic’ institutions—to stake claims and govern behavior on extractive frontiers. Drawing on ethnographic evidence from Betsiaka, a rural commune in Madagascar’s far north, I show how a gold mining-specific dina has figured in local leaders’ struggles against state-corporate interventions; in external actors’ strategies of domination; and in intracommunity contests between factions seeking wealth and power in the diggings.

1. Introduction

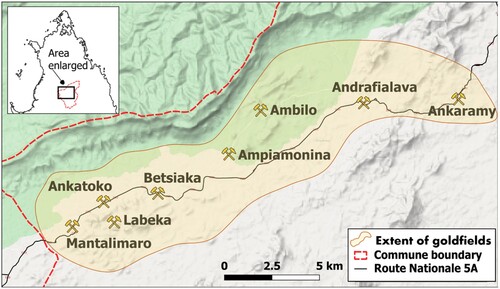

Betsiaka is a rural commune in northern Madagascar known for its dust and mud, for being the natal village of now-deceased former President Zafy Albert—and, most prominently, for gold (volamena). Today, roughly 25,000 miners work across Betsiaka’s goldfields, which span roughly 70 square kilometers of scrubby hills, narrow valleys, and open flood plains south of the forested escarpment of Andavakoera. The local gold economy has deep roots stretching back to at least the mid-nineteenth century (Klein Citation2020), and presently provides income to approximately 90 percent of resident households.

When I first visited the town (see ) in 2016 and asked community leaders to explain local regulation of extractive activities, the assistant mayor handed me a draft copy of Betsiaka’s gold mining dina. ‘This is our guide,’ he said. ‘Our law.’ Dina are customary codes associated with community self-governance, a form that scholars and rural residents alike consider traditional in and indigenous to Malagasy society (Bérard Citation2009). Long favored by rural communities for addressing cattle banditry and insecurity, dina have proliferated in recent decades in relation to natural resource conservation, cultivation, extraction, and use. State agencies, conservation NGOs, and corporate extractors have incorporated dina into ‘community-based’ management strategies for forests, fisheries, rangelands, and other resources. Local and regional leaders have also increasingly integrated them into programs for managing productive activities critical to livelihoods and rural development, especially commodity sectors like vanilla, cacao, cattle, sapphires—and, in Betsiaka, gold.

Today’s Betsiaka DinaFootnote1 is a 40-page booklet comprising 73 articles that outline rules for claim-staking and relations with proximate operations; processes for dispute mediation; penalties to be levied; taboos to be observed; and more (see ). Its final pages, meanwhile, feature handwritten decisions from the community meeting at which the Dina was adopted, as well as ordinances of approval stamped with the red seals of various state authorities. The last of these comes from the magistrate’s court in Antsiranana, the regional capital. The court’s approval in May 2017 completed the Dina’s officialization (homologation) under a 2001 law, meaning it has thence been imbued with state authority.

In addition to being a 40-page booklet of 73 articles and red stamps of approval, though, Betsiaka’s Dina is also a bundle of contradictions. Despite the red stamps, for example, nearly all the artisanal gold mining activities the Dina ostensibly regulates are technically illegal, lying as they do within a 10,625-hectare concession held by Kraomita Malagasy (KRAOMA), Madagascar’s state-owned mining company. The text includes well-established, socially-embedded provisions that shape and reflect everyday life and work in the diggings—but also features articles that miners do not know or observe, and prescribes penalties that are rarely applied. Moreover, while the state-sanctioned Dina establishes a committee charged with enforcement (the Komity Mpanatanteraka ny Dina, or KMD), it explicitly requires that the committee use a blue stamp, not red, to reflect that KMD members are not agents of the state. State officials, meanwhile, have sometimes worked to undermine and/or coopt KMD authority.

Given such paradoxes, one might think twice before accepting the Dina as a static or straightforward ‘guide’ to local-level mineral governance in Betsiaka. Rather, in this paper, I take the Dina as a starting point for interrogating historical and contemporary processes of domination and resistance featuring the enrollment of ‘indigenous’ institutions. I argue that Betsiaka’s Dina has been a key tool and target of territorialization (Vandergeest and Peluso Citation1995), with varied actors—local leaders, state-corporate interests, intracommunity factions—alternately seeking to wield, shape, and/or undermine the Dina in contests over access and authority. In advancing these claims, I work to engage with scholarship examining the mobilization of indigenous forms in frontier contests over landscapes, resources, and the people therein (Peluso and Lund Citation2011), offering both a comprehensive accounting of Malagasy dina and an examination of the abiding—even heightening—relevance of ‘customary law’ in thoroughly modern resource politics.

Resource frontiers have rightly been identified as sites of ‘institutional opulence’ (Korf, Hagmann, and Doevenspeck Citation2013) where socio-political architectures are reconfigured as diverse claimants seek to establish and challenge territorial regimes (Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018). Often, such ‘plurified’ (Côte and Korf Citation2018) governance landscapes feature institutions—e.g. land tenure regimes, authorities—drawing on registers of custom or indigeneity. Corresponding interest in such forms has surged in recent years, with scholars documenting how state actors have sought to sideline, subvert, and/or coopt customary authorities and systems to their benefit (Alden Wily Citation2012; Capps Citation2018; German, Unks, and King Citation2017; Mamdani Citation2018), as well as how local elites and community leaders have leveraged such identities and/or forms to claim power or rents (Berry Citation2018; Capps and Mnwana Citation2015; Ferme Citation2018; Lund Citation2008; Smith Citation2018) or assert autonomy and resist state-corporate dispossession (Capps Citation2018; Coyle Citation2018; Peluso Citation2005, Citation2018; Springate-Baginski and Kamoon Citation2021).

My goal here, then, is to bring Betsiaka’s Dina—and the ‘indigenous’ form of Malagasy dina more broadly—into this conversation. Defining ‘indigeneity’ in Madagascar is admittedly complex. Only one group—the Mikea of the southwest—have been formally recognized as ‘indigenous’ by external watchdog organizations (Huff Citation2012). While there is broad agreement among scholars that the island’s supposed 18 or 20 official ‘tribes’ (foko) were invented (i.e. fixed, delineated, enumerated) by the French colonial regime to facilitate their envisaged politique des races (Alvarez Citation1995; Domenichini Citation2003), the island undoubtedly hosts a range of ‘regional groups’ recognized as (more or less) distinct by constituent members and outsiders alike (Esoavelomandroso Citation2001). At the same time, whatever differentiated identities a Malagasy person might embrace, they nevertheless remain Malagasy. Ascriptions of Malagasy-ness are absolutely fundamental to understanding how Malagasy lifeworlds are conceptualized as comprised of both things that are indigenous and local to the island and its peoples (gasy, malagasy), on the one hand, and foreign (vazaha) introductions, on the other. One key informant—Gérard Justin, the lawyer who helped write the Betsiaka Dina—compared dina with other uniquely Malagasy phenomena whose names have been adopted into foreign lexicons, including lavakaFootnote2 and ravenala.Footnote3 ‘You could translate dina as ‘convention’ or ‘collective and deliberate decision,’’ he said, ‘but it is nevertheless something distinct. It is Malagasy.’ Fady (taboos), too, have been identified as a concept and practice used to differentiate that which is Malagasy from that which is foreign (Sodikoff Citation2011). Such distinctions matter immensely. And it is in this sense that I discuss dina as an indigenous institution, a form the island’s residents—as well as foreigners leading interventions—see as rooted in a collective and authentic Malagasy identity.

It is precisely this seen-as quality that I wish to explore, leveraging an excavation of the Betsiaka Dina to counter simplistic notions holding dina as either wholly organic and virtuous expressions of community values, or as imposed ‘empty institutions’ (Ho Citation2016) fully commandeered by state-corporate-NGO designs. Instead, they are simultaneously sites of contestation and possibility (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2018), enduring and reimagined ‘custom’ or Malagasy-ness enrolled in projects of both domination and resistance (Scott Citation2008). As such, I work to show how Betsiaka’s community leaders have used the Dina and antecedent institutions to bolster local autonomy; how vampiric state-corporate elites and other external actors have alternately sought to manipulate or undermine the Dina to advance their interests; and how the Dina has figured in intracommunity contests between locals, migrants, and other factions in pursuit of access and authority.

To explore these dynamics, I draw primarily on 15 months of ethnographic fieldwork undertaken between 2015 and 2022. Ten of these months were spent living in Betsiaka, a site to which I was drawn because of its gold-rich reputation, and where a particularly helpful contact—a former commune worker I refer to in this paper as Francisco—facilitated connections with a broad range of local actors. In Betsiaka, I worked with miners in their pits and tunnels; sat in on community meetings where various questions related to mining and/or local governance were debated; accompanied KMD members and other local authorities on site visits, through dispute mediations, and on other business; and carried out further forms of participant observation. Though my position as a white, American man doubtless shaped the information and interpretation of practices and events, close and extended ethnographic examination of governance-in-practice helped to reveal authority structures and institutions like the Dina not simply as they were explained to me by local elites when I first arrived in the area, but rather as mining laborers and other community members interacted with and described them over the extended course of my stay—to understand provisions and power from below, from the underground. I also conducted numerous semi-structured interviews with interlocutors in Betsiaka, Antsiranana, Ambilobe, and Antananarivo (both remotely and in-person, typically in Malagasy with occasional use of French or English).

Moreover, I further incorporate insights from roughly 28 months of prior experience in Madagascar (from 2010-2012), when I served as a U.S. Peace Corps Volunteer in Vondrozo, a district in the island’s rural southeast. It was during this time that I first learned of Malagasy dina, a favored tool of my partner organization, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). WWF agents had been working with local residents to establish community-based forest management associations (vondron’olona ifotony, VOIs) in villages along the rainforest corridor, and to elaborate and codify conservation rules with each of these novel groups in the form of dina. While I use evidence from Betsiaka to substantiate this paper’s claims, my time working with WWF and the VOIs in Vondrozo leave me confident in saying that the arguments I make apply to dina in a general sense—and undoubtedly to ‘customary’ institutions beyond Madagascar, as well.

2. Territorialization and indigenous institutions

Similar to other zones of extraction and/or conservation across the rural global South, Betsiaka’s goldfields are defined by a particular set of frontier dynamics (Klein Citation2020), including a fragmented and contested governance landscape (Barney Citation2009; Lund Citation2006) where varying actors reconfigure institutional orders as they compete over territory (Peluso and Lund Citation2011). In Madagascar, existing scholarship has examined how competition among and within politico-legal institutions shapes access to and authority over land (Burnod, Gingembre, and Andrianirina Ratsialonana Citation2013), and how the burgeoning power of international conservation NGOs and other non-state actors in environmental management can both extend state territorialization (Corson Citation2011, Citation2016) and reconfigure sovereignty (Duffy Citation2006). In navigating plurified governance landscapes, institutions and actors appeal to various normative registers to secure legitimacy and authority (Sikor and Lund Citation2010). In some cases, this might mean emphasizing an institution’s alignment with formal law, or its association with ‘state-ness’ (Lund Citation2006). Alternatively, actors might stress an institution’s ‘customary,’ ‘traditional,’ or ‘indigenous’ character.

This latter set of types has received heightened attention in recent years, especially as vehicles of community resistance to state, corporate, and/or NGO-instigated projects of conservation or extraction, or as (alternately championed or derided) components of decentralized or ‘community-based’ approaches to environmental management (Dressler et al. Citation2010; Kull Citation2002; Li Citation2010; Ribot, Chhatre, and Lankina Citation2008). In the former instance, scholars have documented communities’ efforts to enact ‘local territorialities’ (Peluso Citation2005) through claims to indigeneity (Li Citation2000, Citation2007a; R. P. Neumann Citation1995; Salazar Citation2017) and campaigns for recognition of longstanding customary rights (Okoth-Ogendo Citation2002; Springate-Baginski and Kamoon Citation2021). Often such strategies have coalesced as forms of resistance ‘from below’ (Hall et al. Citation2015), mobilizations and adaptations of identities or customary institutions aimed at frustrating state-corporate enclosure and dispossession (Bottazzi, Goguen, and Rist Citation2016; Gingembre Citation2015). Scholarship on artisanal mining in Madagascar and beyond has documented the utilization of customary forms in local-level mineral governance (Klein Citation2022b). In some cases, miners’ and mining communities’ deployment of such institutions is framed explicitly as a mode of opposition to state-corporate interventions aimed at formalization or dispossession (Hilson and Yakovleva Citation2007; Klein Citation2022a; Lahiri-Dutt and Brown Citation2017; Nyame and Blocher Citation2010).

The leveraging of customary forms is not, of course, a technique available exclusively to (idealized) rural communities. While colonial and post-independent states have sometimes undermined ‘traditional’ systems of governance (Alden Wily Citation2012) or extinguished customary claims through direct appropriation or concession-granting processes (German et al. Citation2014), they have also sought to coopt or otherwise enroll customary institutions and authorities in logics and programs of rule. In Africa, a primary example is colonial indirect rule via chieftaincies (or ‘native authorities’), a strategy in which European officials often grossly misunderstood indigenous institutions and subsequently transformed them in ways that left them out of sync with prior local structures and cosmologies (Capps Citation2018; Mamdani Citation2018; Ribot and Oyono Citation2012; Shah Citation2010).

In recent decades, states and NGOs across the global South have frequently turned to customary institutions in programs of decentralization and ‘community-based’ natural resource management (CBNRM) (Osei-Tutu, Brobbey, and Agyei Citation2021). Such efforts are ostensibly meant to grant local communities greater control over proximate resources through the empowerment of ‘traditional’ institutions assumed to be more democratic, more legitimate, and less corrupt (Brown and Lassoie Citation2010; Bruce and Knox Citation2009; McLeod, Szuster, and Salm Citation2009). Scholars have heavily criticized these claims, highlighting such approaches’ tendency to extend state power and/or legitimize undemocratic forms in devious ways (Neumann Citation1997; Ribot, Agrawal, and Larson Citation2006, Citation2008; Ribot and Oyono Citation2012); rely on problematic definitions and assumed characteristics of community or indigeneity (Li Citation2002, Citation2007b); or undermine customary forms’ legitimacy through imposition and insufficient empowerment (Kull Citation2002, Citation2004). State-administered formalization programs for customary systems or claims, moreover, might paradoxically provide pathways for government agencies, NGOs, or other actors to augment their own authority and pursue their own agendas in local contexts rather than furthering local capacities and autonomy (German, Unks, and King Citation2017).

Furthermore, customary institutions are not only vehicles for resistance by communities, on the one hand, or domination by states or NGOs, on the other. They also provide spaces and occasions for particular groups or individuals to seek advantage. ‘Traditional’ authorities and other local elites, for example, might fight to secure greater recognition and power for customary institutions so as to enhance their own positions in national and local politics. In several African countries, chiefs have worked to install or portray themselves as ‘legitimate’ community representatives capable of brokering access for intervening state and/or capital interests like mining companies (Capps and Mnwana Citation2015; Coyle Citation2018; Smith Citation2018). Different genres of customary leaders also might compete with one another for influence and authority—as in the case of Ghana, where chiefs and earth priests have intensified contestation over control of land (Lund Citation2008).

Recognizing the multitudinous ways in which customary institutions might be conceived and leveraged by different actors with disparate interests helps to illuminate an important aspect of conflicting territorialities and institutional dynamics on the frontier. In short, contestation in such settings need (and often does) not take the form of opposition between clearly distinct and neatly divided sorts of institutions and their advocates—state actors and formal law versus communities and custom, for example. Rather, plurified legal or regulatory contexts often feature ‘messy realities where boundaries between the different forms of ordering are at best blurred, as actors and institutions transcend the different legal systems and spaces in pursuit of their interests, reconfiguring the boundaries of those spaces in the process’ (Suhardiman, Bright, and Palmano Citation2021, 413). Amidst such conditions, ‘custom’ itself—as well as the identities, structures, and claims it is used to craft, legitimate, and bolster—is reinterpreted, refashioned, and redirected (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2018).

In Africa, scholars have interrogated a range of institutional forms with such complexities in mind, especially customary land tenure regimes and chieftaincies, revealing their entanglement with ‘ongoing, multifaceted struggles among local, national, and international actors over practices and meanings of ownership, authority, and belonging’ (Berry Citation2018, 79–80). A principal objective of this paper is to extend these discussions to other indigenous forms—namely geographically-inscribed codes like Malagasy dina—and to consider what the context of Betsiaka might illuminate vis-à-vis contemporary resource politics, plurified regulation, and customary law in Africa (Diala Citation2017; Zenker and Hoehne Citation2018), as well as the possibilities and complexities of mobilizing ‘indigenous’ forms in decolonial struggles for territory beyond (Anthias Citation2018; Fraser Citation2018).

3. Dina and rural power in Madagascar

The word ‘dina’ means charter or pact, and broadly denotes agreements made to govern behavior and social interactions (Bérard Citation2009). Dina also refers to something more specific, though: a codified set of rules, regulations, and penalties elaborated and enforced by a fokonolona (Andriamalala and Gardner Citation2010; Henkels Citation2002). Fokonolona is a flexible concept, generally referring to a deliberative assembly comprised of those community members with an interest or stake in the issue at hand (Graeber Citation2007b, Citation2007a). Traditionally, fokonolona crafted and adopted dina by consensus. Together with fady (taboos), fomban-drazana (the culture or way of the ancestors), fomba (broader cultural norms), and fihavanana (social solidarity), dina are understood as part of the corpus of so-called customary law in Madagascar (Henkels Citation2002).

Though the institution’s precise origins and full lineage are unclear, scholars and rural residents alike consider dina to be traditional in and indigenous to Malagasy society (Bérard Citation2009). Historically communities have formulated and transmitted dina orally, but increasingly they are recorded and promulgated in writing (Andriamalala and Gardner Citation2010; Rakotoson and Tanner Citation2006). Contemporary dina take many forms and are used to address a wide range of social issues, including banditry and public security; adherence to taboos and cultural norms; public works programs; communal labor arrangements; other aspects of local economic life and natural resource management; and the reconciliation of traditional customs with national laws (Andriamalala and Gardner Citation2010; Bérard Citation2009; Henkels Citation2002; Horning Citation2005; Kraemer Citation2012; Kull Citation2002; Rakotoson and Tanner Citation2006). In the 2018 round of Afrobarometer surveys, 73 percent of Malagasy reported having dina in their communities, and 90 percent expressed positive assessments of those dina, viewing them as legitimate.

The perceived legitimacy of dina has made it an attractive institutional form for actors interested in winning community cooperation or submission for centuries. From the early days of the imperial Merina kingdom—which had conquered nearly two-thirds of the island by the mid-nineteenth century—rulers employed dina in attempts to control rural productive activities, coerce peasant labor, and subvert local self-governance (Rajaona Citation1980). French colonial authorities undertook similar measures evidencing a broader strategy ‘to derive policy from existing practice’ (Feeley-Harnik Citation1991, 7), an approach involving the (attempted) cooptation of other customary concepts and institutions like fokonolona (Graeber Citation2007a; Rajaona Citation1980; Rakotoarijaona Citation2019) and fady (Feeley-Harnik Citation1991; Sodikoff Citation2011), as well. Dina—or rather a rigidified version of dina, refashioned to accord with foreign juridical logics—were absorbed into the administrative apparatus of the colony via a 1902 decree declaring them subordinate to civil law (Rajaona Citation1980). As with the Merina court, colonial authorities used dina to conscript labor, and placed strict stipulations on the spheres of activity dina were officially permitted to regulate with further directives into the 1950s (Bérard Citation2009). As with fady and fokonolona, such efforts were strongly challenged by rural populations, who consistently (re)claimed each of these forms and used them to delineate boundaries of difference, reject domination, and mobilize resistance (Feeley-Harnik Citation1991; Sodikoff Citation2011, 74).

Since independence, the Malagasy state has assumed a variety of postures towards dina. Recognizing dina as ‘the only thing universally understood’ by rural populations (Bérard Citation2009), central administrators in the 1960s declared dina tools for socio-economic progress and development, gave local state authorities jurisdiction over dina, and directed local leaders to popularize state law through dina (Rajaona Citation1980). Rural communities, meanwhile, continued to use locally-elaborated dina to resist state efforts to impose authority and enclose lands (Bérard Citation2009; Rajaona Citation1980). In the 1970s, Didier Ratsiraka’s revolutionary government enrolled dina in its broader socialist program, using dina socialiste to relay directives or pilot initiatives of the central state government (Rajaona Citation1980). Nevertheless, local populations continued to distinguish between community and state dina (Bérard Citation2009). As the country entered a deep social and economic crisis in the late 1970s and early 1980s, rural residents revitalized earlier understandings of fokonolona as based in fihavanana and mutual reliance, and elevated or elaborated dina as a means to address growing insecurity (Rajaona Citation1980; Rakotoarijaona Citation2019).

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Malagasy government again enrolled dina in reform-minded programs, this time efforts pushed by international donors advocating administrative decentralization (Bérard Citation2009). The 1992 constitution and subsequent legal reforms sought to integrate dina into civil law du nouveau, and granted mayors the power to propose, adopt, and enforce dina (Henkels Citation2002). These initiatives coincided with growing interest among conservation actors, development organizations, and state officials in community-based natural resource management (CBNRM). In 1996, the Malagasy government adopted Law 96-025—often referred to as the GELOSE law (from GEstion LOcale SÉcurisée)—to allow for the transfer of management rights and responsibilities over certain renewable resources to local communities. Initially, fokonolona—‘communities’ as customarily understood—were the intended target, but a range of political and practical considerations led conservation actors, government officials, and donors to instead favor the creation of new institutions called vondron’olona ifotony (VOIs) or communautés de base (COBAs) (Pollini and Lassoie Citation2011). Notably, these local associations are not customary bodies, but are meant to govern by way of a different ‘indigenous’ form: dina. The GELOSE transfer process involves the elaboration of dina regulating local activities relating to the resources in question. These dina—conceptualized as community creations, but often written with heavy extra-local involvement—must conform with existing law and receive state approval (Kraemer Citation2012; Kull Citation2004). Once the process is complete, dina carry the ‘force of law.’ In 2001, the government issued a further decreeFootnote4 (commonly known as GCF, for Gestion Contractualisée des Forêts), to simplify and expedite forest-related dina (Bérard Citation2009)

Recent scholarship examining and assessing dina has largely focused on those created through the GELOSE and GCF processes. Findings have underlined the importance of ‘traditional’ institutions in environmental management, as well as the uniquely powerful role of dina in shaping community behavior in the Malagasy context (Andriamahazo et al. Citation2004; Andriamalala and Gardner Citation2010; Bérard Citation2009; Fritz-Vietta, Röttger, and Stoll - Kleemann Citation2009; Henkels Citation2002; Kraemer Citation2012; Rakotoson and Tanner Citation2006). However, studies have consistently found dina to be plagued by problems of non-compliance and non-enforcement, and to be largely ineffective in achieving stated conservation goals (Andriamalala and Gardner Citation2010; Rabemananjara et al. Citation2016). Several factors explaining these shortcomings have been identified. Dina are often externally imposed and/or reflect top-down state or NGO priorities instead of community interests, and consequently are not well understood or viewed as legitimate among local populations (Andriamahazo et al. Citation2004; Andriamalala and Gardner Citation2010; Bérard Citation2009; Henkels Citation2002; Horning Citation2005, Citation2018; Kull Citation2004; Pollini et al. Citation2014). These findings resonate with analyses of conservation actors’ attempted appropriation of fady (taboos) to advance environmental goals, efforts that have failed due to misunderstandings of concept and context and pointed resistance by local community members (Osterhoudt Citation2018a; Sodikoff Citation2011). Furthermore, there is a persistent incongruity between dina as traditionally understood (community-driven, consensus-based) and dina as now enshrined in Malagasy civil law (Bérard Citation2009; Henkels Citation2002). Meanwhile, notions of fihavanana make it exceedingly difficult for community members to enforce strict dina provisions and apply sanctions (Andriamahazo et al. Citation2004; Andriamalala and Gardner Citation2010; Fritz-Vietta, Röttger, and Stoll - Kleemann Citation2009). Comparative studies, meanwhile, have concluded that environmental dina have greater chances of achieving stated aims when instigated by local actors and accepted by preexisting customary authorities as effective means for addressing recognized problems (Rakotoarijaona Citation2019; Ramamonjisoa, Rabemananjara, and Raharijaona Citation2020).

Despite this heavy focus on dina conceived under GELOSE and GCF, not all contemporary dina fall under these frameworks or pertain to forestry or biodiversity conservation. In 2001, the Malagasy state adopted Law 2001-004Footnote5 establishing guidelines for dina related to ‘public security.’ The preamble to the law makes clear the government’s motivation, namely that communities were creating and enforcing dina without consulting state authorities. Under this law, dina must go through an officialization process and receive approval from local authorities and regional courts, which again requires accordance between the dina and existing statute. Several regional governments have adopted dina under Law 2001–004 with diverse provisions related to public security (e.g. cattle banditry), public health, environmental protection, customary tenure and land disputes, and regionally-significant commodity sectors (e.g. sapphire mining, vanilla cultivation). Often these regional dina (dinabe or dinam-paritra) are based on earlier, informal dina conceived by communities or lower administrative divisions (communes or fokontany). The Betsiaka Dina—wholly focused on gold mining activities—was officialized under Law 2001-004.

Important to recognize, however, is that whether associated with GELOSE, GCF, or Law 2001-004, officialized dina only comprise some small fraction of dina on the island. Despite governmental efforts to subsume longstanding local dina into legible (and domesticated) regional iterations, a plethora of community-level, security-focused dina related to cattle banditry remain ‘informal’—especially those like the southeast’s ‘dina of the red neck’ (dina mena vozo), which permits summary execution of bandits in contravention of state law (Kneitz Citation2014). Moreover, communities across the island continue to create and maintain dina related to local norms, ancestral customs, taboos, and other spheres of life and work that remain outside the state’s reach. In the far south, dina represent ‘the principal institution created by the fokonolona for the purpose of rule-making’ and enforcement, with levels of institutionalization varying depending on context (Marcus Citation2008). Dina are ubiquitous manifestations of what Graeber (2007b) refers to as ‘active traditions of self-governance’ in Madagascar’s ‘provisional autonomous zones,’ regions where the state apparatus has assumed a ‘ghost-like’ character.

Dina thus remain a form in flux, terrain upon which centuries-old contests for legitimacy and power continue to be waged. Regardless of mounting evidence of the ‘failure’ of GELOSE dina, conservation NGOs and state actors continue to use the form with various goals in mind: exerting greater control over priority landscapes (L’Express de Madagascar Citation2021; NewsMada Citation2017), suppressing the use of fire (M Citation2021), combating violence and insecurity (NewsMada Citation2020), halting wildlife trafficking (NewsMada Citation2018), and more. While doing so, these actors consistently invoke idioms of custom, contending that using dina, whatever the process of adoption or ultimate objective may be, serves ‘to preserve traditional Malagasy values’ (R Citation2021). Meanwhile, the same cast of characters disparages the effects of other customary institutions like fihavanana, and seeks to heighten dina enforcement by undermining social cohesion through monetary incentives and other measures (Kaufmann Citation2014).

Corporate actors, too, have seized on dina, underlining the form’s utility for not just those concerned with conservation, but also those motivated by extraction. To illustrate, consider an exchange I had in December 2017 with two Malagasy consultants working for a foreign mining company trying to secure access to deposits near a town on the island’s east coast. The diggings were a source of income for many local people, and the area’s popularity had drawn an influx of migrant miners from the north. The consultants explained how they had drawn on customary institutions in formulating a strategy to win local support for the company’s entrance:

‘There is a kind of local law … called dina … We worked with the dina, local customary leaders (tangalamena), the project [i.e. mining company], and local miners to expel and keep out the people from Diego [migrant miners]. You see, the interesting thing with the dina is we can change it. We can change it to keep out particular people.’

The consultants had done prior work in Betsiaka, as well, and so I asked them to compare these efforts to the Betsiaka Dina. It was different, they told me, because the Betsiaka Dina was both the culmination of many years of effort on the part of local leaders to build a ‘mining code’ that could govern a large mining population of diverse origins, and also because Betsiaka and its Dina attracted heightened attention from elite actors they called ‘the mafia.’

In the remainder of the paper, I turn to unpacking this complexity, working to illuminate how the Dina has been a tool and target of territorialization for various actors in Betsiaka—for local leaders against external state-corporate interests; for state agencies, corporate extractors, NGOs, and shadowy ‘mafia’ elites seeking access to and/or authority over the diggings; and for diverse groups and individuals within the mining community competing for power and gold. Overlapping frontiers and territories have been well documented in Madagascar (Blanc-Pamard Citation2009; Vuola Citation2022; Zhu and Klein Citation2022). Existing research has explored conflict over which activities or uses should be prioritized, as well as competition between institutions in struggles over access to and authority over territory (Burnod, Gingembre, and Andrianirina Ratsialonana Citation2013). I aim to extend this conversation to show how both the dina form generally and the Betsiaka Dina in particular are themselves sites of contestation—a story not of competing sectors or rival institutions, but of the way a single, specific form and code has been targeted and turned to competing ends. Furthermore, I contribute a novel perspective showing not just that there are ‘two types of dina’—‘those created within the community … and those … created by outside interests’ (Marcus Citation2008, 95), or those that are traditional or endogenous versus those that are imposed, administrative, or exogenous (Bérard Citation2009; Rakotoarijaona Citation2019)—but rather that individual dina can become fields upon which much more elaborate contests over access and legitimacy are played, complicating simplified distinctions and showing the heightened stakes around the form’s ostensible valences of autochthony and authenticity.

4. Governance by the people: the Betsiaka Dina and community resistance

When asked about the Dina’s provenance, Betsiaka miners initially cited recent processes of revision and officialization that took place from 2015-2017. Follow-up questions (e.g. what was being revised, and why) quickly brought mention of earlier versions of the Dina drafted between 2010-2013. Pressed further, though—on provisions’ origins, and what came before—local residents eventually recounted a much longer story. Far from a recent creation cut from whole cloth, the Dina instead was assembled over time through the accretion and progressive codification of anterior institutions through iterative bricolage (Cleaver Citation2002; Klein Citation2022b). ‘Its roots stretch back to the times of my father and grandfather,’ said Francisco. ‘Maybe even further back.’

While many norms and taboos included in the text dated back to at least the 1970s (and several far before that) much of the system’s architecture took clearer form beginning with the first of Betsiaka’s many modern rushes—that at Labeka in 1990-1991 (see ). The Labeka Rush involved the arrival of 15,000 miners, the proliferation of crisscrossing underground tunnels, and an associated spike in conflicts. Mediation responsibilities fell to site bosses and ray aman-dreny (RAD, local councils of elders), but they were quickly overwhelmed by the volume of cases and range of issues to be addressed. ‘There was a breakdown in social relations,’ said Zohery, an elderly Labeka veteran who still lives near the rush site today. To ameliorate the situation, Zohery explained that a well-respected local man proposed an idea suggested by one of his migrant miner colleagues: to adopt a warden (vaomiera) system—commonly used in other sectors like agriculture—for the local mining sector. The community accepted the idea, and the first committee of wardens was appointed by consensus.

The warden system (système vaomiera), as it continues to be known, was further developed following a 1994 strike at Andrafialava. Warden responsibilities were more clearly defined, claim-staking processes and claim dimensions altered, registration requirements established, and particular types of encroachment by neighbors prohibited. Henri, a former Betsiaka mayor who was also president of Andrafialava fokontany at the time, identified this process of elaboration as the moment the Betsiaka Dina was effectively ‘born.’ Though they hadn’t yet labeled the body of provisions a dina, he said, this was ‘the first time things were put in writing.’ This step was seen as a critical pivot towards the more codified dina form, and towards a governance regime in which sectoral knowledge and technical expertise assumed greater weight. Another local leader confirmed the significance of this transition: ‘Everything before [the 1994 strike] was cultural norms (fomba),’ he said. ‘After, we had rules (fepetra).’

In 2000, a subsequent rush at Ampiamonina prompted local officials to further extend and formalize existing provisions into a 39-article regulatory framework (fitsipika), that remained in place for roughly a decade. Significant changes came again, however, following a series of major strikes at Ambilo in 2010-2012, a period known for social upheaval. The troubles emanating from the Ambilo Sarakorako (a word elsewhere associated with promiscuous women, here used to denote a conflict-laden rush) led miners and local leaders to conclude that the existing framework was insufficient for dealing with contemporary conflicts. ‘It was expired (efa lany daty),’ a former assistant mayor explained. ‘It didn’t have ample specifications (tsy ampy fepetra).’ What followed was the process that would lead to today’s Dina.

In this abridged retelling, I have followed local residents’ tendency to equate episodes of institutional evolution with strikes, rushes, and social conflagrations that made novel rules, regulations, and enforcement bodies seem necessary. Beyond this functionalist account, though, lies a host of further reasons community members opted for particular provisions and forms of self-governance—reasons firmly oriented towards maintaining local autonomy over mineral commons (Klein Citation2022a) and countering state-corporate attempts to exert greater control over the region’s gold economy. Local understandings of these dynamics are influenced by historically-sedimented narratives of resistance stretching back to the era of French corporate colonial operations in the early 1900s, evidence of which is littered across the landscape in the form of abandoned shafts and building foundations. Memories and fables of extraction under the colonial regime are appropriated by local actors, strategically and actively positioned ‘within the politics of the present’ (Stoler Citation2008, 196).

The long French presence, for example, is seen as evidence of Betsiaka’s immense natural wealth, and of the dangers posed by external actors intent on exploiting what locals call ‘our territory’ (taninay). Residents characterize mining activities today as the reclamation of land, resources, and wealth from the French and other foreign extractors. Old shafts are reworked, colonial-era ‘overburden’ reprocessed as contemporary ‘ore’ thanks to gold’s long-running price rally. Of course, state-corporate interest did not disappear at independence, and so resistance discourse also focuses heavily on the maintenance of miners’ holdings in the face of more recent interventions, as well. These include attempts by the French overseas mining bureau, BRGM (Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières), to expel artisanal miners and initiate large-scale extraction in the early 1990s, as well as contemporary efforts by KRAOMA and its Chinese partner firms to enter the diggings. Miners and local leaders in Betsiaka clearly recognize the alignment of state interests with those of these intervening mining companies (BRGM, KRAOMA, the Chinese firms), and consistently portray the central government in pejorative and predatory terms.

Often these critiques assume an ethnic valence. Local opposition to central state authority is framed as an effort to counter hegemonic domination of the island’s politics by ethnic Merina from the capital region (often referred to pejoratively by northerners as Borzan). Such antipathy is rooted in a long and complicated history of struggle between an expansionist Merina empire and local polities (Gezon Citation2006), a French colonial period in which Merina predominance persisted under frameworks of indirect rule (Esoavelomandroso Citation2003), and a post-independent political economy in which the resource-rich north has often found itself at loggerheads with the administration in Antananarivo (Zhu Citation2022). For Antankarana—the group considered indigenous to Betsiaka—identity is strongly defined by ‘the story they tell about their survival in the face of pursuit and exploitation by the Merina (Hova, Borzan) in the nineteenth century’ (Lambek and Walsh Citation1997, 310). Most migrant miners belong to northern and/or coastal groups with similarly antagonistic views towards Highlanders—e.g. Sakalava harboring resentment and distrust (L. Sharp Citation1994); Betsimisaraka with memories of oppression and exploitation (Cole Citation2001)—who continue to dominate state institutions and positions of power.

This latent and pervasive oppositional disposition has influenced community leaders’ rejection of state authority and pursuit of local governance via custom-based forms. The Dina (and antecedent institutions) has been central to local strategies of resistance (Rajaona Citation1980) and territorialization against state-corporate intrusions. Consider the words of Vivato, an older miner from the area: ‘The Merina (Borzan) government doesn’t rule here,’ he told me. ‘We here have the Dina, which is the people’s government (fanjakanam-bahoaka).’ The Dina is thus conceptualized as an authentic expression of local autonomy, a form whose power flows from the community in opposition to the central state.

In contemporary debates over KRAOMA and its partner firms, moreover, local leaders and community members were emphatic in stressing the primacy of the Dina. At a community meeting called to discuss one of KRAOMA’s partner firms’ efforts to establish operations in an area called Ambolamenabe, a KMD member named Patrick explained:

‘The Dina is the law that we, here, have built together. We wrote it here—the people [vahoaka] did, and it’s now been accepted by the government, as well. The Dina compels us miners to register our claims … for purposes of protection. We can protect the people with things that are written. This is … the work of the KMD … to protect you from the company, and from the government.’

‘I’ll say it again: make sure you have papers for your claims. The KMD is doing good work … [and] if you have papers … then they can protect you [from expropriation by KRAOMA, the Chinese, and the government]. The reason for the KMD’s work, their purpose, is to protect you, to protect the people.’

Also present in their statements, though, was the acknowledgement that part of the Dina’s power and efficacy in serving to protect local interests was derived from its officialization—from its certification under Law 2001-004, and its translation of local claims into legible holdings via textual transcription. In this way, community actors might be seen as appealing to the ‘ghost-image’ of state authority (Graeber Citation2007b) or state-ness (Lund Citation2006) to bolster their claims. Indeed, KMD members frequently emphasized that physical copies of the Dina were deposited at visible foci of state authority—the gendarmes’ post, the commune, with the government’s resident administrative delegate (déléguée)—to convey its legitimacy and weight to me (the foreign researcher), and to conflict disputants wary of KMD-imposed penalties.

Important to note, however, is that the circumstances of Betsiaka are quite a departure from the contexts in which Graeber (2007b) describes the Malagasy ‘ghost state’—places where rural people might entertain state pretensions to authority in front of visiting officials, then promptly ignore them once said officials have departed. Graeber himself uses ‘bauxite mines’ as a foil to the communities he has in mind, and the goldfields are no different. Nodes of extraction and (potential) accumulation like Betsiaka command the attention of state elites. Rather than a ghostly character, then, the state assumes a different guise; local residents like Zohery use the term mpihina—eater, devourer—which I might creatively transmute to ‘vampire.’ As with Graeber’s ghost state, the vampire state is negligent regarding service provision or the maintenance of (democratic) order, but apparates in with coercive force to stake subsoil claims, facilitate extraction, and ensure the flow of gold-derived wealth into elite coffers.

Nearly a month to the day before the meeting at Ambolamenabe, I spent an afternoon talking with Gérard Justin, a lawyer based in Antsiranana. Gérard knew the Betsiaka Dina well, owing to the fact that he had been commissioned by German development agency GIZ to assist with its rewriting and officialization as part of a 2015–2017 intervention in the region. When I asked Gérard about the Dina’s origins, he responded, animatedly:

‘It was created in response to problems … especially the government interfering in mining operations. If there hadn’t been problems like this, Betsiaka wouldn’t have created the Dina. But there were these problems—the authorities were constantly interfering, constantly making things difficult for people. So there was discussion within the community, and they decided they should create a dina, to fight the government for control.’

5. The Dina and (attempts at) external domination

While the Dina has indeed been central to community territorial strategies, external actors—state agencies, foreign projects, mining companies—have also sought to manipulate, undermine, or coopt the Dina and its antecedents for their own (differing) purposes. Mining ministry representatives began visiting the region regularly in the 1990s, and staff members from subsidiary agencies—the Bureau du Cadastre Minière de Madagascar (BCMM) and Agence Nationale de la Filière Or (ANOR)—have continued doing so from the mid-2000s until today. Though generally failing to formalize the region’s artisanal sector, these actors have succeeded in introducing ideas subsequently adopted into local governance strategies. Examples include the use of miners’ licenses and claim registration booklets, as well as the notion that such records afford important protection or insurance for miners in legal proceedings.

Projects supported by foreign bilateral organizations have also influenced institutional trajectories. Especially notable are the 2006–2008 Projet de Renforcement Institutionnel du Secteur Minier Malagasy (PRISMM), a mining sector reform effort funded by Cooperation Française, as well as GIZ’s 2015–2017 intervention. Though both PRISMM staff and local residents largely characterized the project as a failure, it did have one lasting effect: it was apparently a PRISMM agent who first suggested codifying the local governance system as a state-sanctioned dina. GIZ, meanwhile, stepped in shortly after the commune’s initial Dina draft had been rejected by the courts, commissioned a lawyer to help with revisions, and convened a regional dialogue meant to ameliorate local governance (with conservation goals in mind). Though the organization discontinued its project in Betsiaka much earlier than envisaged—due to complicated ‘politics,’ a former GIZ agent said—it did see the Dina through to officialization in 2017.

Local leaders in Betsiaka saw the uptake of suggested provisions and pursuit of Dina officialization as tools for strengthening local governance and enhancing local autonomy through formal recognition of community-controlled institutions. The aforementioned external actors, meanwhile, were united in viewing these developments as something quite different: measures that, however incrementally, rendered the local mining sector more legible (hence more controllable), and that fused local institutions with state legal authority.

Details of the officialization process are instructive: local leaders in Betsiaka first submitted the Dina to the court for approval on January 3, 2013. Two weeks later—on January 17, 2013—the district attorney scribbled a note on the submission’s first page indicating that nothing in the Dina was problematic vis-à-vis existing law or interests of public order. At some point thereafter, however, the official opinion of the government changed. Leaders in Betsiaka and the Antsiranana-based lawyer, Gérard, both insisted that the court had refused officialization citing incompatibilities between the Dina and existing law—but no one seemed to quite recall the process through which this disapproval had been communicated, or which ‘incompatibilities’ had been cited. Regardless, a lengthy GIZ-orchestrated process of regional dialogue, community consultations, and subsequent revisions ensued.

The final text of the 2017 Dina includes a number of notable changes from its 2013 predecessor. First, rather than appealing for officialization under a 1994 law’s decentralization provisionsFootnote6, it does so under Law 2001-004. Second, whereas Section One of the 2013 draft elaborated rights and responsibilities of workers, bosses, and sponsors, the 2017 text extends discussion to landowners and gold collectors, as well. Third, whereas the 2013 draft maintained the warden system without specifying selection procedures (practically meaning such would happen via consensus), the 2017 Dina instead established the KMD, whose members are elected by majority vote. The text also contains a range of further additions and alterations, including a provision banning the buying and selling of gold at night.

Many local residents offered favorable assessments of these revisions. For example, many of the region’s most powerful families and individuals are gold collectors, and so bringing them under the jurisdiction of the Dina was viewed as long overdue. ‘If miners are subject to the Dina,’ said Jaozandry, a mining laborer in his early 30s, ‘then the buyers should be too.’ Moreover, certain wardens were notorious for corruption and abuses of power, and so elections were seen as a welcome check on such behaviors—‘making them accountable to the people,’ Francisco explained. At the same time, these changes opened up avenues for the state to better understand and control the local sector. Traders were made subject to legible local rules endorsed (and enforceable) by the state. Enforcement authorities that had required consensus for appointment now needed only a simple majority in elections controlled by the government-appointed administrative delegate. A simpler Dina largely reflecting sedimented local practice was fleshed out to include a range of aspirational prescriptions—in some cases (e.g. with the prohibition on night transactions) clashing with existing norms. Penalty and fee amounts increased. And, while strong penalties on circumventing the authority of the KMD and other local authorities remained in the text, appeal to the court system was integrated into provisions regarding dispute mediation, providing a mechanism through which state officials might shape outcomes in conflict cases.

Each of these shifts has been exploited by state actors. ANOR agents publicly targeted local traders for failing to register and pay enumerated taxes and fees as required by the Dina, part of a broader campaign to force more gold production into licit value chains. The sudden death of the highly-regarded KMD president in November 2017 precipitated a standoff over committee leadership. While popular sentiment coalesced around elevating Jao Divay—a respected veteran miner who finished second in the 2017 election—to the post, the government’s resident administrative delegate rejected a petition requesting his installment and instead scheduled a new election. That election, though, was delayed once, twice, thrice. In the meantime, external state officials cultivated relationships with certain KMD members described by one local leader as selfish (tia tena) and open to corruption. When an election was finally held in July 2019, one of these members, Gino, ascended to the presidency, an outcome that same local leader alleged was fraudulent.

The packing of the Dina with provisions miners do not know or deem unnecessary, meanwhile, has arguably undermined its legitimacy. Physical copies of the stapled, cardstock-covered booklet are hardly scarce, but tend to rest in the hands of local leaders (KMD members, community elders, authorities, law enforcement) or elites (large sponsors, collectors, landowners, etc.). I encountered a handful held by mining laborers or civic-minded residents and shared my own digitized copy with interested interlocutors. Most rank-and-file miners, though, rely on popular common sense or defer to dig leaders—and when Dina provisions are unexpectedly found to clash with prevailing practices and perspectives, disillusionment or disengagement can follow. Few miners file mandated paperwork or pay registration fees to the KMD. Penalty amounts are seen as exorbitant—‘too heavy,’ a miner who had recently been ruled against told me. Night commerce proceeds unabated. ‘We should exorcize the provision that bans traders from weighing and buying gold at night,’ one local leader told me, ‘because popular respect for the Dina might be diminished if its rules are broken every day!’ In discussing the complexities of navigating the region’s most contentious rushes, Jaozandry and several other mining laborers lumped KMD members, gendarmes, and commune officials into the same sprawling category as external state actors, complaining how the ‘government’ or ‘bureaucracy’ (fanjakana) sought to manipulate contingent rules and regulations to their benefit.

State actors and elite sponsors, meanwhile, have leveraged the formality and fixity of the written and officialized Dina to advance their aims. Many interlocutors explained that external actors will send representatives to instigate conflicts at productive claims and reject local mediation outcomes so that cases are escalated into the state court system. This allows for manipulation of proceedings and rulings, and puts miners who have not complied with registration requirements at a disadvantage. Dina officialization has thus been a double-edged sword; miners can indeed claim novel protections, but only if they significantly modify existing practice by filing paperwork and paying fees. Nor are such developments restricted to contexts of conflict mediation. In February 2018, for example, the District Chief in Ambilobe, capital of the district to which Betsiaka belongs, issued a proclamation urging all miners to obtain licenses, register claims, and pay fees to the KMD and applicable state agencies. Several KMD members viewed the effort as wrongheaded, but felt as though their hands were tied given the partial sublimation of their authority into state hierarchies—again, a direct result of Dina officialization.

Despite these examples, most Dina provisions do continue to reflect quotidian local practices (e.g. around claim-staking, relations between proximate digs, conflict resolution, etc.), and much of the work of the KMD—especially lower-level dispute mediation—has proceeded in ways deemed legitimate by local miners (dynamics I elaborate further in Section 6 below). Whereas much of the discussion above focused on external interests’ manipulation and cooptation of the Dina, these more mundane (and positive) everyday realities have prompted certain external actors to adopt another sort of strategy toward the Dina: delegitimization. When I asked KRAOMA’s chief representative in the region about the Dina, for example, he complimented the idea before strongly criticizing the reality as corrupted and ineffective at preventing conflict and crime, protecting the environment, or developing the town.

His pejorative characterization echoed the comments of other external elites I spoke with, as well. BCMM and ANOR staff dismissed the Dina as failing to tackle the local sector’s illegality, its imbrication with illicit channels. ‘Artisanal mining in Betsiaka is supposedly governed by the Dina,’ the BCMM director told me, ‘but the gold it produces goes to the large collectors … and leaves the country illicitly.’ He went on:

‘A better option would be strong government intervention. We could clear out illegal artisanal miners to make way for industrial mining, or could force them into cooperatives authorized to work in restricted areas … and then educate them with a popularized version of the mining code.’

‘You know local leaders in Betsiaka have been attempting to build a local mining code for many years, and now these efforts have culminated in the Dina … So this is what local miners understand. This is what dictates how they work, how they behave.’

In summary, then, external actors have engaged with the Dina in multiple ways to advance territorial objectives. In certain instances, they have sought to exploit the Dina’s officialization process, which fused the community-level, ‘custom’-based form with state authority and concomitant hierarchies, as well as a handful of its provisions, its leadership structure, and its ostensible rigidity to open relatively autonomous spaces to heightened external influence. At other times, they have worked to undermine and delegitimize the Dina through claims of corruption or ineffectiveness, denigrating the institution vis-à-vis whichever functions remain beyond the ambit of external meddling to justify interventions aimed at ‘improving governance’ and augmenting control.

6. Belonging, authority, and access: intracommunity contests and the Dina

In addition to figuring prominently in local and external actors’ territorial strategies, the Dina has also played a central role in intracommunity contests over belonging, authority, and access. One oft-invoked distinction along the lines of which such contests have played out is that between locals with ancestral roots in the region (zanatany), long-established migrants (together with zanatany sometimes referred to as tompontanana, ‘those responsible for the town’), and newer migrants (vahiny, ‘guests/strangers,’ or mpamangy, ‘visitors/passers-by’).Footnote7 Betsiaka tompontanana consistently mentioned migrant influxes following large gold discoveries as moments of social conflict and institutional reconfiguration. In part, they ascribed the changes rather straightforwardly to the growth of the mining population, especially rushes during which workers targeted underground deposits. Events at Labeka followed this logic, as did consolidation of the warden system following the 1994 rush near Andrafialava. During the Ambilo Sarakorako, ‘migrants came from all over the island … and conflict became more common,’ explained Kamisy, a former assistant mayor. ‘We built the Dina [in 2010-2013] to improve the system, to calm these conflicts.’

While Kamisy did see the increase in miners’ numbers as generative of both conflict and corresponding institutional change, he also emphasized something else: these migrant miners’ diverse ways of working and being. Another veteran miner, Papan’i Jaozandry, laid blame for the social unrest at Ambilo on migrants, but also on local miners who had left to try their luck in the sapphire mines of Ankarana and Ilakaka, and then returned home:

‘People changed, became different. Many local people went [to mine sapphires], learned bad ways, and then brought those habits here. Along with a large group of migrants, they arrived to chase the new gold veins [at Ambilo], and brought problems. Our community was wrought by social unrest. There was a rupture in cultural norms. The arrival of these bad ways led to conflict.’

Researchers working elsewhere in northern Madagascar have argued that in-migration and heterogeneity can weaken adherence to taboos (Golden and Comaroff Citation2015), but the relationship between autochthony and taboo transgression is often more complex. In the sapphire mining region of Ankarana/Ambondromifehy to Betsiaka’s northwest, for example, Walsh (Citation2002, Citation2006) has documented the ways in which miners often violate taboos in their work. However, both locals and migrants engage in these transgressions; as one local miner and tompontanana put it, ‘nobody has a money taboo’ (Walsh Citation2006). At the same time, migrant miners often do attempt to observe local fady, as ‘they expect that such respectful, responsible behavior will assist them in achieving the prosperity which they seek from the land’ (Walsh Citation2002, 464).

Betsiaka presents a similarly complex context. Migrants comprise roughly 70 percent of miners per municipal authorities, an unsurprising figure given the prevalence of mobility-defined ‘flexible extraction’ across the region’s multiple and overlapping resource frontiers (Zhu and Klein Citation2022). Local leaders and established residents were clear in pointing to migrant taboo transgressions as both sources of misfortune (e.g. illness, death, and falling gold production) and as reasons for the invention of novel governance forms, as the statements recounted above convey. Nevertheless, Betsiaka’s goldfields are hardly a ‘land of no taboo’ (Osterhoudt Citation2018b). Instead, the pursuit of gold—a sacred (masina) substance—involves constant negotiations of fady. While exploitation of underground deposits is no longer strictly prohibited, miners perform appropriate rituals (joro) to ask guardian earth spirits (tsiny) for permission before digging commences. The Antankarana polity’s taboo against working on Tuesdays is written into the Dina itself. Other fady—against working on particular days; fighting at mining sites; bringing meat or foods grown underground to the diggings; consuming chicken or pork before working; etc.—continue to shape miners’ interactions and comportment in substantial ways, as well, further revealing the importance of taboos not only in proscribing certain actions, but also in defining positive moral selfhood (Lambek Citation1992; Osterhoudt Citation2018a; Sodikoff Citation2011).

Rather than supplanting taboos, then, the Dina and its antecedents have represented a necessary complexification—an elaboration of ‘clear rules’ that complement taboos, providing kinds of specified guidance around claims, labor, and dispute mediation required for social regulation in heterogeneous social contexts. Though framed in this sense as a way for local leaders to more effectively manage migrant-heavy populations, migrants have simultaneously influenced the forms that governance has taken. Recall that a migrant miner suggested adoption of the warden system in Labeka; Henri, the Andrafialava fokontany president who pushed for its consolidation in the mid-1990s, was also a migrant; and the council charged with designing the 2013 Dina was dominated by migrants. Furthermore, while the majority of wardens were locals in the system’s early days, migrants quickly gained in numbers, and have represented a majority of wardens and KMD members ever since. In Betsiaka’s 2019 KMD elections, migrants predominated in each jurisdiction.

Migrants have thus played a critical role in advancing institutional elaboration and codification in Betsiaka’s gold sector. Doing so has provided an opportunity for migrants to integrate themselves into local governance structures in ways otherwise constricted by systems based on ethnicity, gerontocracy, and anteriority. Anthropologist Leslie Sharp (Citation1994) has observed a relevant dynamic in the northern town of Ambanja, where migrant women have become mediums hosting the spirits of local royalty (tromba). Becoming tromba mediums effectively allows these women to change their ethnicity, to win insider status, and to become active in local Sakalava power structures (Sharp Citation1994). While inventing the Dina and its antecedents has not made migrants into Antankarana zanatany, it has created an institutional space within customary structures where migrants can assume governing power, hastening their transformation away from being passers-by towards being (vahiny) tompontanana, instead.

This phenomenon has at times been cause for conflict. I witnessed one especially acrimonious argument between a zanatany and Gino, a migrant KMD member, in February 2018 outside the bar behind my house in Betsiaka. The zanatany man initiated the disagreement by stating that migrants should be barred from serving on the KMD. ‘You only care about being in a position of power so that you can accumulate as much money as possible and send it away to build your home in Antalaha [the KMD member’s natal town on the northeast coast],’ he charged. ‘You don’t care at all if Betsiaka develops!’ Gino heatedly retorted that zanatany are lazy, uninformed, and fail to translate the community’s natural wealth into development. ‘Migrants,’ he argued, ‘come here to work, do so diligently, and are best equipped to govern. We know the work!’ he continued. ‘We know the way of the diggings!’

This example is emphatically not meant to suggest that intracommunity dynamics in Betsiaka are wholly defined by an essentialized, local-versus-migrant opposition. In fact, most Betsiaka residents deny the existence of generalized conflict between local and migrant miners. Rather, the dynamics highlighted above should be taken to demonstrate how such identities are periodically enrolled and take on heightened salience in particular instances of conflict, including those over the Dina. Important to note here is that the gold mining-specific Betsiaka Dina, though articulated as a municipal code, applies specifically to the gold sector and its participants. That is, participation in the gold economy and labor of gold mining is what makes one a constituent of the imagined community governed by the Dina, what makes one subject to its rules, and what gives one a stake and voice in its composition and enforcement. The only people eligible to vote in KMD elections, for example, are gold miners (not simply residents of the commune, whether local or migrant).

Moreover, while the argument on the bar patio focused on a hypothetical question of who was best suited to sit on the KMD, other conflicts and controversies about the composition and comportment of the committee were much less abstract. Consider again the situation discussed in the prior section following the death of the KMD president, the delayed election to replace him, and its eventual outcome. Certain KMD members exploited the context to curry favor with external elites, augment their authority, and enhance their access to opportunities for accumulation. Following the president’s death, KMD members in Ambilo, one of Betsiaka’s most productive areas, were found to be extracting unsanctioned shares from miners. The revelation prompted a series of intense discussions among local leaders, who in March 2018 took the extraordinary step of temporarily suspending the Betsiaka KMD in an attempt to force members to get their house in order. Commenting on the context at the time, Jao Divay, the once-favored candidate to become KMD president, offered an appraisal that both condemned the behavior of the KMD members in question while reaffirming confidence in the Dina itself: ‘It’s not the structure [of the Dina] that’s the problem,’ he said, ‘but the people within it.’ KMD members eventually resumed their activities, but the Ambilo contingent remained estranged from the rest of the committee. Meanwhile, patio disputant Gino—a Betsiaka-based member who would go on to assume the presidency in 2019—had become a regular fixture at the installation of one of KRAOMA’s Chinese partner firms, which was still working to negotiate terms for access to targeted goldfields. Along with other local authorities, Gino accepted cash and other gifts from the company, leveraging his role as a ‘traditional authority’ to pursue ‘strategies of extraversion’ (Bayart Citation2000; Le Billon Citation2014; Duffy Citation2005) to secure material gains, illuminating how dina can be made into ‘personal instrument(s) of power,’ institutions ‘manipulated by self-serving elites’ in efforts to accumulate wealth and authority (Marcus Citation2008, 86).

Despite these controversies over the composition and comportment of the committee, most local miners continue to regard Dina provisions and the KMD as both functional and legitimate. Many rules—regarding the staking and dimensions of claims, relations between neighboring digs, procedures of adjudicating underground intersections, and so on—are indeed common sense. Miners generally view their holdings as secure. When asked about conflict and governance in the diggings, for example, Jaozandry emphasized that despite its unruly reputation, ‘everyday exploitation is calm and orderly—and when needed, we have the Dina.’ Those feeling anxious, meanwhile, eagerly make use of the Dina’s heightened codification to insulate themselves from perceived risk. Louis, a 25-year-old miner, explained his approach:

‘We decided to register our claim because I wanted to have clear papers (taratasy mazava). It’s a kind of insurance. If a big strike is made in the area, then no one will be able to force their way in, to take what’s ours. We’re protected; we’ve used the Dina to protect our claim.’

‘If you stake a claim, dig a pit, and find gold, what you need to do is head straight to the KMD and get your papers in order … That’s how you can keep things calm and orderly, by having your papers and engaging with the KMD … But another benefit of the Dina, and of the KMD, is that if there are problems, you can discuss and work to reach forms of solidarity-focused consensus (raharaha-pihavanana). That’s the purpose of the Dina—that we have rules, but that their application is Malagasy, is done in accordance with Malagasy culture.’

7. Conclusion

On a warm and dusty Tuesday afternoon in June 2018, I found myself sitting with KMD-member Patrick on the concrete patio of the bar-discothèque across the courtyard from my house. I’d asked members of the Dina committee to convene in order to review details of particular conflict cases I’d been following over the past many months. True to habit, Patrick arrived early, before the others, and so we grabbed a table and settled in sharing an orange Fanta, his regular preference over Three Horses Beer (THB), Madagascar’s staple libation, which the other KMD members tended to favor. As we sat drinking and conversing, my thoughts turned to the list of conflicts I planned to bring up, and to a familiar refrain common in the diggings with which I knew Patrick took issue: ‘gold provokes conflict’ (volamena mampiady). Out of curiosity, I posed the question to Patrick: what did this adage get wrong?

‘Gold does not provoke conflict,’ Patrick said with a slow, deliberate cadence that reminded me of the way in which he’d often quote passages of scripture. ‘Humans provoke conflict. Humans cause disorder.’

‘So then how is conflict to be avoided?’ I asked. ‘How is disorder to be overcome?’

‘Law,’ he replied. ‘Law brings order.’

Patrick thus saw human failings—the pursuit of self-interest above the social good—as the source of conflict in the diggings. Its antidote, meanwhile, was in law, in collective institutions. Patrick was something of a Dina buff. He always had his copy on hand, and had even committed excerpts to memory. Section and article, he would cite—not unlike his recitations from the Bible, chapter and verse. Moreover, he had a fondness for enrolling the Dina during public speeches or arbitration sessions via a very particular phrasing: ‘The Dina compels us,’ he would say. He saw the Dina as powerful, and as an imperative. ‘The law of the people’ (lalànam-bahoaka), he called it.

Back on the disco patio, I tapped the Dina booklet sitting on the table between us. ‘You mean this law?’ Patrick nodded, then continued:

‘But the law has no meaning outside of its application. The Dina is nothing but writing (soratra fo). The power of the Dina lies in the fact that it came from the people, and is manifested in the way that we, the KMD, apply it. It’s only in us applying it that it becomes real.’

Nor are these lessons limited to the island’s shores. Indigenous or customary institutions continue to govern rural social life in much of continental Africa and elsewhere in the global South, and remain attractive vehicles for central states, NGOs, and other actors looking to advance diverse objectives in the countryside. Evidence from Betsiaka argues against both reifying such forms as inherently legitimate, authentic, bottom-up, community-based ‘solutions,’ or dismissing them as hopelessly coopted, corrupted, external impositions. Rather, the picture that emerges is one in which what matters is not simply the institution itself or the indigenous valences ascribed to it, but also—to paraphrase Patrick and build upon his observations—how it is used, applied, enacted, subverted, or empowered; where it fits in plurified regulatory regimes; and how it’s understood in light of sedimented histories of struggle.

Moreover, all of these elements or contingencies are subject to change—and change is indeed afoot. Heavy sponsorship of digs is becoming more prevalent in Betsiaka. A corporate ‘buyer’ called MADAGOLD has negotiated its way into the diggings. A Chinese firm has paved the road running through the region. Each of these developments stands to instigate further attempts at hegemonic domination by vampiric state-corporate actors, resistance by community members intent on safeguarding local autonomy, and navigations by different groups and individuals within the community in search of stability or advantage. Amidst these shifts, Betsiaka’s Dina is likely to remain a bundle of contradictions, a territorial tool and target, and a case providing valuable insight regarding the evolving role of ever-proliferating and persisting dina in governing the power-laden landscapes of Madagascar.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Brian Ikaika Klein

Brian Ikaika Klein is an assistant professor at the University of Michigan, jointly appointed in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies and the Program in the Environment. He is a political ecologist interested in environmental governance, resource politics, and rural development with a particular focus on Madagascar

Notes

1 When referring to dina in a general sense, I use a lower-case ‘d.’ When referring to the Betsiaka Dina in a specific, proper sense, I capitalize the term.

2 Lavaka are a type of erosion gully prevalent across Madagascar’s Central Highlands.

3 Ravenala is the common name for Ravenala madagascariensis, a tree native to the island, also called the traveler’s tree or traveler’s palm.

4 Décret 2001–122 du 14 février 2001 fixant les conditions de mise en oeuvre de la gestion contractualisée des forêts (GCF)

5 Loi 2001–004 du 25 Octobre 2001 portant réglementation générale des Dina en matière de sécurité publique

6 Article 118 of Law 94–008 related to the powers of collectivités territoriales décentralisées

7 Studies of Malagasy sociopolitical contests often acknowledge the salience of these group identities (e.g. see Feeley-Harnik Citation1991; Walsh Citation2002, Citation2006).

References

- Alden Wily, L. 2012. “Looking Back to see Forward: The Legal Niceties of Land Theft in Land Rushes.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (3–4): 751–775. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.674033.

- Alvarez, A. R. 1995. “Ethnicity and Nation in Madagascar.” In Cultures of Madagascar: Ebb and Flow of Influences, edited by S. Evers, and M. Spindler, 67–83. Leiden: International Institute for Asian Studies.

- Andriamahazo, M., C. Y. E. Onana, A. Ibrahima, K. B. Komena, and J. Razafindrandimby. 2004. Concilier exploitation des ressources naturelles et protection de la forêt: Cas du Corridor Forestier de Fianarantsoa (Madagascar) (p. 143). Antananarivo: ICRA, CNRE, and IRD.

- Andriamalala, G., and C. J. Gardner. 2010. “L’utilisation du dina comme outil de gouvernance des ressources naturelles: Leçons tirés de Velondriake, sud-ouest de Madagascar.” Tropical Conservation Science 3 (4): 447–472. doi:10.1177/194008291000300409.

- Anthias, P. 2018. Limits to Decolonization: Indigeneity, Territory, and Hydrocarbon Politics in the Bolivian Chaco. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Barney, K. 2009. “Laos and the Making of a ‘Relational’ Resource Frontier.” Geographical Journal 175 (2): 146–159. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2009.00323.x.

- Bayart, J.-F. 2000. “Africa in the World: a History of Extraversion.” African Affairs 99 (395): 217–267. doi:10.1093/afraf/99.395.217.