ABSTRACT

Climate reductive translations of migration attract international attention, but result in three problematic misreadings of Bangladesh’s socioecological landscape. First, attributing migration to climate change misreads coastal vulnerabilities and the importance of migration as a gendered livelihood strategy to deal with rural precarity and debt- both in the past and present. Second, misreading migration caused by brackish tiger-prawn cultivation, infrastructure-related waterlogging and riverbank erosion as ‘climate-induced’ hinders a discussion of long-term solutions for rural underemployment, salinisation, siltation and land loss. Lastly, framing climate change as causing ‘gendered displacement’ ignores the importance of affective kinship relations in shaping single women’s migration choices.

Introduction: beyond climate reductive translations of migration

In 2014, I met with Bangladeshi migration researchers in Dhaka who had gained significant funding for a project on ‘climate-related migration’ following Cyclone Aila in 2009. I asked [in Bangla] how migration was related to climate change. The researchers replied that since their main focus is on migration, they could continue their work by using climate change as a masala to attract funding. They further pointed out that shrimp farming was the main cause of outmigration:

The main reason why the flooding was so devastating during Aila was due to the damages shrimp farms [ghers] made on flood-protection embankments. The devastation was caused by a cyclone, but its impact would have been less had it not been for ghers.Footnote1

Yet an increasing number of papers frame such migration as climate-related (Kartiki Citation2011; Saha Citation2017; Ahsan Citation2019) or even climate-induced (M. R. Islam and Shamsuddoha Citation2017; R. Islam, Schech, and Saikia Citation2021) while also creating a false binary of internal migration as ‘climate-induced’ vs. ‘non-climate-induced’ (Adri and Simon Citation2018) in ways that removes from view political problems of land use that make rural livelihoods even more precarious ().

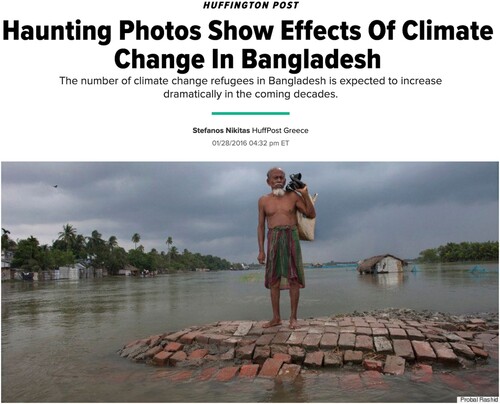

Figure 1. Huffington Post article on ‘Climate Change Refugees’. Source: Nikitas (Citation2016). Photo courtesy Probal Rashid.

Bangladesh is often portrayed as a ‘climate hotspot’ where its coastal migrants are described as victims of climate change who are ‘forced’ to migrate due to climate change, or else risk drowning in rising sea levels or in cyclonic events (Collectif Argos Citation2010; Stellina Jolly and Ahmad Citation2019; McDonnell Citation2019). Such recasting of migrants in Bangladesh and other regions of the world as ‘climate refugees’ ignores how migration was, and continues to be, a central part of agrarian lives (Farbotko and Lazrus Citation2012) where causes of migration are multifaceted and contradictory, as are the motivations of those who move (Amrith Citation2014).

Striking images of Bangladeshis as ‘climate refugees’ can be seen as an attempt to advocate for global climate justice, but they are also anchored in a longer history of Bangladesh being a key destination of international aid. As donors are increasingly allocating funds to climate change, development brokers engage in ‘climate reductive translations’, that is they create a causal narrative that links their particular activities to the policy theory of climate change, in order to continue with their ongoing activities (Dewan Citation2021b; Citation2020).Footnote2 ‘Climate reductionism’ refers to ‘the increasing trend to ascribe all changes in environment and society to climate change’ (Hulme Citation2011, 255–256) – a climate reductive translation of migration represents migration as caused by climate change. While contemporary capitalism fuels the climate crisis (Borras Jr. et al. Citation2022), capitalist actors increasingly draw on climate reductive translations to reframe flood-protection embankments, brackish aquaculture and capital-intensive high-yield agriculture as climate adaptation solutions and misread the Bengal delta (Dewan Citation2021b). Climate reductive translations of migration may attract international attention for Bangladesh’s plight, but it misreads coastal vulnerabilities while normalising a victimising discourse where there is no space to discuss political solutions that could alleviate agrarian livelihoods such as rural employment schemes, silt management and freshwater agriculture.

The current framing of migration as caused by climate change deflects attention away from how coastal vulnerabilities are fundamentally entwined with political structures of social and economic inequalities. Similar to how policymakers have misread Kissidougou’s forest landscape by reading history backwards and wrongly blaming local villagers for deforestation and environmental destruction in the present (Fairhead and Leach Citation1996, 3), attributing migration from Bangladesh’s coastal zone to climate change alone misreads the socio-environmental landscape and the multi-faceted drivers of migration. As the 2022 floods in Pakistan highlight, devastation is often accepted as largely unavoidable and unpredictable when blamed on climatic change rather than poor governance (Kelman Citation2022). Misreadings of environmentally related migration (e.g. salinisation, floods and riverbank erosion) as ‘climate-induced’ removes existing structural socio-economic push factors of migration and potential ways to address agrarian struggles from public debate. Even so, ‘push’ dimensions of migration do not help to fully explain why some women in similar socio-economic positions are unable to migrate, while others can. Climate reductive translations of migration not only misread socio-environmental and gendered vulnerabilities, but also ignore the historical importance of migration for agrarian livelihoods while removing women’s agency to choose to migrate.

Women in the Global South are constructed as more ‘vulnerable’ to climate change (Arora-Jonsson Citation2011) in ways that tends to obfuscate their agency (Cuomo Citation2011, 695). Bangladeshi women are assumed to be more likely to suffer in climate-related events due to being restricted by patriarchal rules of female seclusion (Cannon Citation2009), that they do not migrate on their own (Poncelet et al. Citation2010) or that they are extra vulnerable to trafficking (Stellina Jolly and Ahmad Citation2019). This stereotyping of gendered vulnerabilities homogenises Bangladeshi women in a way that ignores how class, education, urban-rural lifestyle, and kinship networks shape different migration possibilities (Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta Citation2004; Mehta Citation2018). Paying attention to the migration decisions of landless single mothers in coastal areas highlights the differential agentive capacity of women migrants and how this is entangled with kinship-based reproductive support.

A historically grounded ethnographic account of migration shows how such processes are embedded in environmental and socio-economic vulnerabilities rooted in political structures of gendered inequality. Through its close attention to the intimate everyday migration decisions of landless single mothers in coastal areas, this ethnography critiques how ‘coastal vulnerabilities’ conflates the vulnerability of a particular place to climatic risk with the socioeconomic constraints of the people living there (Dewan Citation2021b, 18–20). It reveals the importance of kinship relations in shaping the differential agentive capacity of women in choosing to migrate and argues that climate reductive translations of migration obfuscate the affective relations that sustain agrarian livelihoods. This historical and ethnographically grounded account of ‘climate reductive translations of migration’ thus contributes to critical debates on the increasingly politicised knowledge production of climate change (Barnes and Dove Citation2015; Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015) and climate displacement in an agrarian world already on the move (Kelley, Shattuck, and Thomas Citation2021).

Three problematic misreadings of the socioecological landscape arise from ‘climate reductive translations’ of migration. First, attributing migration to climate change misreads coastal vulnerabilities and the importance of migration as an agrarian livelihood strategy to deal with rural precarity and debt both in the past and – also for single women (divorced, widows). Second, misreading migration caused by saline tiger-prawn cultivation, infrastructure-related waterlogging and riverbank erosion as ‘climate-induced migration’ or ‘climate displacement’ hinders a discussion of long-term solutions that may remediate such damaging anthropogenic floods. Lastly, ideas of climate change causing ‘gendered displacement’ misread gendered vulnerabilities. Landless women consider various aspects of reproductive kinship support intimate relations and social reputation as they choose whether or not to migrate to brick kilns, Dhaka garments industry and the Gulf for domestic work. Misreading causes of migration based on tropes of Bangladesh as a ‘climate change victim’ hinders public debate on solutions for rural underemployment, floods, land loss and salinisation by aquacultures. Crucially, it misses how migration is constrained/enabled by affective kinship relations to sustain social reproduction at home.

The article draws on 12 months of multi-sited qualitative research from August 2014 to July 2015. I conducted forty in-depth, unstructured interviews with development professionals in Dhaka and Khulna cities and nine months of ethnographic fieldwork in southwest coastal Bangladesh, mainly in the embanked floodplain of ‘Nodi’Footnote3 in Khulna District. This included participant observation of village life in the two unions of Nodi: ‘Lonanodi’ were brackish tiger-prawn cultivation was dominant, and ‘Dhanmarti’ where a grassroots movement ended such saline shrimp farming. My main interlocutors were two groups of women doing ‘earthwork’ – repairing small roads in a donor-funded rural employment scheme targeting landless ‘female-headed’ households (equated with the ‘poorest of the poor’ See Kabeer Citation1991; Lewis Citation1993). I met the twenty women regularly at their work sites, and they soon invited me home to meet their families. I hired some of them as my field assistants to go door-to-door and carry out a qualitative household survey (jorib) in Nodi with what ended up as approximately four hundred households. NGOs starting new projects often carry out a jorib, resulting in villagers being accustomed to talking to outsiders about their livelihoods and this helped legitimate my presence. Spending whole days with the women further facilitated participant observation, where I immersed myself into rural life, to ‘as far as possible, to think, see, feel and sometimes act as a member of its culture’ (Powdermaker Citation1966, 9).

Misreading coastal vulnerabilities

Rural precarity and agrarian debt

It was payday during one of the last months of the donor-funded rural employment scheme in Nodi. I sat with the landless women labourers outside the local government building in Shobuj town as they waited for their salaries. When they received news that they would not receive the two-year extension to their existing four-year contract, they were visibly upset and disappointed. Riparna, married with two children exclaimed:

[After two years], we are barely stepping out of the poverty we’re in and now we’re going to fall straight back down again. If we only got two more years, we would have been able to secure our livelihoods.

All these expenditures are internalised as individual private costs in the absence of state-entitlements for Bangladeshi citizens (Dewan Citation2021b). This reflects another key finding from my survey: the large amount of agrarian debt accumulated through women household members taking four to six microcredit loans from different NGOs (Dewan Citation2021b; See also Karim Citation2011; Paprocki Citation2016; S. B. Banerjee and Jackson Citation2017). Nodi comprises of Dhanmarti union where a grassroots movement ended tiger-prawn cultivation in 2008 in favour of freshwater crop cultivation, and Lonanodi union where the movement failed. In both unions, households used microcredit to pay for healthcare, education, dowry and fees/bribes to labour brokers, illustrating the importance of debt for agrarian formation (Fairbairn et al. Citation2014)

Development projects and NGOs, both through the access to microcredit and to various development projects targeting the ‘poor’, constitute an important element of the political economy in Bangladesh’s southwest coastal zone, considered to be the most poor and vulnerable in the country. My jorib in Nodi revealed that there were significantly more landless women (without capital or male adult earners in the household) that coveted these short-term rural employment schemes despite low wages and no social or health insurance: they provided an income for a fixed duration. The project-mentality of the development industry serves to perpetuate a system that only provides temporary patches to large-scale problem of structural rural un(der)employment and sustain a form of labour market based on precarious, low-cost labour (Dewan Citation2021a; See also Qureshi Citation2014). Coastal vulnerabilities here are fundamentally tied to socio-economic inequalities.

Migration as an agrarian livelihood strategy

High levels of out-of-pocket expenses incentivised people in Nodi to migrate – but not only among those facing the livelihood hardships of living in saline barren deserts of shrimp farms (see Feldman and Geisler Citation2012; Paprocki Citation2019b). Local work was mostly available during the planting of monsoon rice in July–August and during its harvest in the Bengali month of Poush (mid-December to mid-January). Seasonal labour migration provides an important source of income for Bangladeshi villagers (Afsar Citation2003; Toufique Citation2002). Able-bodied male daylabourers migrated for a month during the dry season to harvest goromer dhan [dry season rice] in the northern parts of Khulna district and received rice as payment, sustaining a family of four for six months. Other forms of circular migration among men in Nodi include crab fishing in the Sundarbans in the winter months at risk of being held at ransom and beaten up by gangs of dacoits [pirates], earthwork in labour markets or rickshaw pulling in Khulna or Dhaka.

Climate reductive translations of migration thus fail to capture the importance of seasonal labour migration as an agrarian livelihood strategy in South Asia – both historically and in the present (Rogaly et al. Citation2002). With the 1947 partition of India, ‘internal’ seasonal migration was obstructed through artificial borders; separating the local people of coastal Bengal despite affinal and cultural ties (Van Schendel Citation2001). Now that global warming is increasingly framed through security and borders (Cons Citation2018), Indian geopolitical fears of Bangladeshi climate refugees are increasingly used to legitimise further securitisation and tightening of border control (Chaturvedi and Doyle Citation2010, 207). For my interlocutors, India – Bharat – was just across the river and not bidesh [abroad]. Working in factories or in regionally located rice mills or brick kilns even across the border were typical forms of season-based migration for landless when local labour opportunities are scarce (Mahbubar Rahman and Van Schendel Citation2003; Samaddar Citation1999). Such circularity enables migrants to remain deeply embedded in rural social networks (Mosse et al. Citation2002), a form of translocal householding (Etzold and Mallick Citation2016; Jacka Citation2017; Gidwani and Ramamurthy Citation2018).

Historical migration among ‘female-headed households’

The historical equivalents of my interlocutors, working-class divorced women and young widows (‘female-headed households’) in Bengal, also migrated as a livelihood strategy (Sen Citation1999; Engels Citation1996). Mughal Bengal’s famous muslin textile industry was an important employer of women spinners in the eighteenth century – they were often widows from all castes and classes (N. Banerjee Citation1990). Bengal’s textile industries were de facto deindustrialised under East India Company rule (Chattopadhyay Citation1990; Faraizi Citation1993). A Dhaka resident described how ‘The import of the cotton thread from England into the country at a low price threw the Bengal spinners out of employment. Hapless widows, who subsisted on spinning were the hardest hit’ (20th August 1831 in The Samachar Sarpan).Footnote4

For women, cottage-based subsistence crafts remained as an important source of income outside of the rice harvesting season – these were no different from ordinary household chores; any woman of any background could resort to them in circumstances of distress. Examples include animal husbandry, making dairy products like clarified butter [ghee], preserving and processing grains and pulses, making puffed rice [muri], preparing vegetable oil, as well as collecting, processing and selling forest produce. They also pounded rice, ground flour, produced rock salt, collected and sold fuel and fodder, as well as made leaf plates, baskets, mats, nets and brooms (N. Banerjee Citation1990, 284). Until the 1880s, 20% of Bangladesh’s workforce comprised of women who were primarily engaged in these food processing industries that they could do from home (Sen Citation1999).

In the 1890s, the jute industry in Bengal grew rapidly and saw a mass movement of migrants to Calcutta and its vicinities; by 1912, there were 61 jute factories in this region employing nearly 200,000 workers (Basu Citation2008). Like today’s pattern of circular migration, adult males migrated to urban industries, while periodically returning to their wives and children in the villages (Basu Citation2008). Women from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh denied support from kin (widows, deserted by husbands) – also migrated to the jute mills (Sangari and Vaid Citation1990; N. Banerjee Citation1990; Sen Citation1999). The colonial expansion of jute exports saw the sector becoming male-dominated, where women were gradually subjected to irregular hiring and informal recruitment (Sen Citation1999).

By the 1920s, Bengal’s jute industry was in turmoil and this was compounded by a major agrarian crisis in Bengal. Rising prices, the commercialisation of the rice trade, changing forms of rent collection, declining agricultural yields, a decrease of arable land due to British-planned public works contributed to rural indebtedness that caused three million peasant families to become functionally landless (Chatterjee Citation1982, 122; Engels Citation1996, 198). Furthermore, the introduction of mechanised rice huskers and the opening of male-operated rice mills in the 1920s impacted women workers disproportionately. While 270,000 women registered rice manual husking as their key occupation in 1911, this number dropped to 136,000 in 1931 (Engels Citation1996).Footnote5 With further decline in cottage-based incomes and the lowered demand for women in jute mills, the 1920s saw landless women leaving their villages to work as domestic servants in the cities; migrating with their families or leaving with single women villagers. The number of women domestics increased by 300% within a decade (Engels Citation1996, 198).

These historiographies of working-class women in Bengal illustrate how the penetration of capitalism and its restructuring of subsistence economies often increased gender-based disadvantages (Momsen Citation2003). They also show the importance historically of migration as a key livelihood strategy that enabled women to adapt to changing circumstances: from reduced reliability of the land due to environmental stressors and shocks to the loss of family/kin support, to remediating debt and the lack of rural income opportunities. Both in the past and present, rural indebtedness serves as a push factor for migration. Yet viewing migration as an outcome mainly of uneven capitalist economic change may be limited. In the remaining paper, I discuss the importance of environmental factors for sustained agrarian livelihoods and the complexity of migration decisions made actively by women who dare to work outside the home and the social stigma they may face for doing. Drawing on ethnographic insights, I argue for the importance of kinship support for social reproduction and intimate relations in enabling landless divorced single mother’s to migrate.

Misreading ‘climate-induced migration’

Shrimp-related migration

Like in the past, most women in Nodi prefer local, cottage-based work that enable them to live at home and take care of their children and still have an income source. After the grassroots movement to end brackish tiger-prawn cultivation, Dhanmarti women were able to yet again engage in subsistence cottage crafts (weaving palm leave mats and making fuel sticks of cow dung). In contrast, women in Lonanodi lamented that saline aquaculture degrades soil fertility and damages water quality in ways that reduces their ability to gain income from cottage-based crafts and to conduct homestead activities that rely on freshwater domestic ponds (Dewan Citation2021b). Since the 1990s, tiger-prawn cultivation expanded through land grabbing (Adnan Citation2013) and changed agrarian structures (Ito Citation2002). It contributed to a ‘fake Blue Revolution’ (Deb Citation1998) that reduced local labour opportunities and contributed to outmigration from rural coastal areas (Swain Citation1996; Guhathakurta Citation2003; Samaddar Citation1999).

Rural livelihoods thrive on fertile agricultural soils and the original purpose of flood-protection embankments in this region was to keep out saline intrusion in the rivers during the dry season (Dewan Citation2021a). Shrimp businessmen drill unauthorised pipes and cut embankments in order to flood these arable lands with brackish waters – rendering them structurally unstable (de Silva Citation2012). Such forced salinisation of the soil reduces local food production and increases the cost of food and other household items (Paprocki and Cons Citation2014; Swapan and Gavin Citation2011), worsening rural livelihood opportunities (Pouliotte, Smit, and Westerhoff Citation2009). Salinisation negatively affects reproductive activities (cooking, cleaning, housekeeping, crafts) as well as mental and bodily wellbeing (Dewan Citation2021b) – illustrating the gendered workings of aquaculture extractivism (Ojeda Citation2021). Based on these socio-environmental effects, the International Organisation of Migration (Citation2010) states that even without the projected impacts of climate change, increasing salinity and population pressure will escalate emigration pressures in Bangladesh’s coastal zone. This illustrates how the vulnerability of agrarian livelihoods in this delta is shaped by a complex interplay of land use practices.

Such an ecological vulnerability is compounded by the lack of state provision in an aid-dependent landscape where discourses of climate change obscures the unequal access to water-land resources held by the more powerful (Dewan Citation2021b). Considering this historical and political context of inequality, climate reductive translations of migration that represent people migrating from tiger-prawn producing villages in the wake of cyclones as ‘climate migrants’ (Lovatt Citation2016) are deeply problematic. A reframing of shrimp-induced migration as ‘climate migration’ could be perceived as part of a grander scheme of depeasantization through ‘anticipatory ruination’ by an ‘adaptation regime’ (Paprocki Citation2019a), where agrarian dispossession fuels migration supporting urban expansion (Paprocki Citation2018). In addition, a climate reductive translation of migration from tiger-prawn producing areas obfuscates the environmental degradation that exacerbates structural socio-economic push factors of migration. It is therefore important to separate migration caused by environmental degradation and broken embankments resulting from shrimp farming from ‘climate-induced’ migration.

Flood-related migration

As shrimp-induced migration suggests, floods in Bangladesh are not solely about climatic change. Furthermore, not all kinds of floods must be prevented. Monsoon borsha floods have long been integral to agricultural activities when silt-laden river water mixed with rain and inundated these deltaic wetlands, this fertilised the soil and irrigated rice fields while providing essential breeding ground for fish (Zaman Citation1993). The construction of donor-funded ‘flood-protection’ embankments in the 1960s obstructed these borsha floods and trapped silt in the outside river (Dewan Citation2021a). The difference in elevation of a raised riverbed and a sunken floodplain resulted in rainwater being unable to drain and caused damaging jalabaddho floods [drainage congestion, waterlogging] (Iqbal Citation2010) that we often see in media portrayals of ‘flooded Bangladesh’ (Dewan Citation2021b) ().

Embankments contribute to waterlogging and obstruct the delta’s ability to raise its land levels through sediment deposits, and therefore pose greater flood risks than rising sea levels (Auerbach et al. Citation2015). Indeed, the unembanked Sundarbans have gained 1–1.5 m of elevation, while embanked floodplains (like Nodi) are sediment deprived (van Staveren, Warner, and Shah Alam Khan Citation2017). A reductive translation of migration as caused by climate-related floods removes attention from the fact that ‘flood-protection’ embankments – through a century of poor infrastructure design by colonial powers and western donors – actually worsen jalabaddho floods (Dewan Citation2021b). Migration due to waterlogging is not ‘climate-induced’.

Embankments further contribute to the silting up several important water bodies, rivers and canals (Dewan, Mukherji, and Buisson Citation2015). This further exacerbates Bangladesh’s climatic risks as the monsoon is expected to shift and this poses a grave threat to lives and livelihoods in South Asia (Amrith Citation2018). Silted waterbodies have less capacity to retain freshwater monsoon rains over the dry season and this hampers their ability to counter the salinity of the yearly dry saline season (Dewan Citation2020).

This siltation and salinisation is also affected by India’s diversion of freshwater through the Farakka barrage that has increased salinity of Ganges flows since the 1970s (Government of Bangladesh Citation1976; Khan et al. Citation2015) and the conversion of agricultural land into saltwater tiger-prawn farms that salinize soil and water since the 1980s (Bernzen, Jenkins, and Braun Citation2019). In order to address flooding as the monsoon rains and dry seasons are expected to shift with climatic change, silt management of the delta and long-term solutions against waterlogging that increase the water-retention capacities of rivers and canals is of urgent importance to help sustain agrarian livelihoods.

Displacement from riverbank erosion

Floods and silt capture the geological feature of the Bengal delta that accretes and erodes. The Ganges River has meandered eastwards for millennia eroding land, riverbanks and now flood-protection embankments as it changes its course while creating new lands (Brammer Citation2012). This held an important role in shaping land revenue policies from Mughal to colonial times (Dewan Citation2021b). O’Malley (Citation1908) writes ‘ … the streams are constantly eating away on one bank and depositing on the other, until the channel in which they formerly flowed becomes choked up’. Riverbank erosion swallows up land into the river. This is not a new phenomenon causing vulnerability in the Bengal delta, recognising how land was swallowed up by the rivers. As a senior government official in Bangladesh’s water sector stated: ‘you cannot correlate climate change [directly] with riverbank erosion … The delta is in a formation stage, it eroded in the past, it’s eroding now, and it will continue to erode in the future as well’Footnote6 ().

Riverbank erosion (nodi bhangon) is damaging and disruptive; ruining water-sided road cum embankments causing those who live on top, or outside, the embankment to lose their homes and move away. My interlocutors in Nodi perceived riverbank erosion as part of the course of the river – this displacement is one they had seen for generations, resulting in people having to migrate. Such erosion is increasingly cast as being caused by climate change where Western media and the aid industry portray these erosion-displaced peoples as ‘climate refugees’ (McDonnell Citation2019; Nikitas Citation2016), their land ‘swallowed by the river’ (Montu Citation2020). A short-term environmental shock like riverbank erosion does not itself constitute climatic change (Bernzen, Jenkins, and Braun Citation2019) nor are riverbank displaced peoples necessarily climate migrants (Lewis Citation2010). Such a climate reductive translation of migration deflects attention away from the fact that riverbank-induced displacement forms part of a wider political problem of regular land loss in a context of land fragmentation and a growing population. Labelling this as ‘climate-induced’ makes it difficult to properly discuss the long-term political solutions of equitable and pro-poor land settlement that forms part of contemporary agrarian struggles in Bangladesh.

Misreading gendered vulnerabilities

Reproductive support, intimate relations and migration to brick kilns

Lipi is a divorced single mother living with her elderly mother and adolescent daughter in Lonanodi. She was particularly upset over the roads project ending since migration was not an option for her. Her elderly mother could not take care of her daughter on her own, nor could she rely on her older brothers’ wives who lived in the same homestead compound. She also expressed strong fear of migrating:

I have never migrated. I’m too afraid to go to an unknown place as a lone woman. Kharap [bad, spoiled] things can happen to me. I will never do it! What if someone kidnaps me or if I get lost and cannot find my way back again? It’s too terrifying, I won’t do that, I’d rather die poor, at home.

Thus, she tried to get irregular work in Lonanodi, struggling to ensure that her daughter could continue studying rather than being married off.

Lipi lives in southwest coastal Bangladesh – a region portrayed by donors and NGOs as a place where migration is ‘climate-related’ and where women are particularly vulnerable to ‘displacement’ (World Bank Citation2009; UNDP Citation2019). In this section, I critically examine this misreading of gendered vulnerabilities by discussing how Nodi women’s ability and motivations to migrate differ based on affective and intimate relations that help them navigate social reproduction in a context of both socio-economic and environmental vulnerabilities.

Furthermore, Lipi referred to brick kilns as places of illicit extramarital relationships and stated that she was above kharap behaviour. Her colleague Yasmine, on the other hand, regularly migrated to the brick kilns each year, spending six months there at a time. She was relaxed about the contract ending stating, ‘Once the project ends, I will go to the brick kilns. I can earn a lot of money’. It was only after I left Bangladesh that she introduced me to her bariwallah [colloq. husband] on the phone. As a divorced single mother, she was now in a new relationship in a society that condemns extramarital romantic relations. In the brick kilns, she and her partner could live as ‘husband and wife’ – a practice of ‘temporary marriages’ also common in the Bengal jute factories of Calcutta more than a century ago, where women would symbolically marry a man as protection from other men (Curjel Citation1923). Similar to how migration to brick kilns may be romantically motivated in India (Shah Citation2006), the privacy of remote brick kilns in Bangladesh provide the opportunity for an alternative life. For Yasmine, who was married off when she was twelve and divorced when her daughter was only a few months old, this romantic relationship was one that she chose for herself as an adult woman. It provided an important incentive for migration, while ensuring personal security among strangers in patriarchal spaces – her choice to migrate was affective and thus not ‘climate-induced’ or due to environmental pressures caused by shrimp farming.

While Lipi had no female relatives to leave her daughter with, and did not want to migrate alone, Yasmine lived with her mother in a female-headed household along with her many sisters and younger brothers’ wives that could take care of her now adolescent daughter while she worked with her ‘husband’. This illustrates how women’s choices to migrate depends on their access to kinship-based reproductive support at home to take care of their children as well as personal contacts (incl. intimate relations) to facilitate migration.

The pull of Dhaka ready-made garments

Both Lipi and Yasmine in Lonanodi lacked educational qualifications and were limited to the informal sector, such as brick kilns. Dhaka’s global textile industry, on the other hand, only employs workers above the age of eighteen with a secondary school certificate, incentivising villagers to allow their daughters to study longer. While landless families in Dhanmarti also migrated to brick kilns, villagers in Dhanmarti knew more people who could help them get jobs in Dhaka’s Ready-Made Garment’s industry. Bangladesh’s garments industry received much negative attention after the 2013 Rana Plaza fire, but it remains one of the popular migration destinations in Bangladesh especially for poor women attracted to the higher urban wages (Seeley et al. Citation2006). They account for nearly two-thirds of the total employment (R. I. Rahman and Islam Citation2013; Jamaly and Wickramanayake Citation1996; Kabeer Citation2000). Dhaka RMG employs more than four million people and accounts for eighty per cent of Bangladesh’s exports (Gardner and Lewis Citation2015, 177). In contrast to migration to the garment industry being a response to capitalist displacement like in the Caribbean (Werner Citation2016), landless women workers in Nodi, perceived work in Dhaka’s RMG industry to hold a higher status compared to seasonal brickwork. Garments work is an employment (chakri) that requires full-time work throughout the year, where they can choose to earn more through paid overtime.

In Nodi, labour migration to Dhaka’s RMG industries provided a stable, not-too-expensive, higher income opportunity to repay large microcredit debt, especially for families whose small businesses or migration abroad had failed. For example, Sunil is a young boy staying with his maternal grandparents in a village in Dhanmarti while his parents migrated to Dhaka RMG to pay off a microcredit loan for a failed poultry business. Rather than such rural-to-urban migration being climate-induced, or that these women workers are necessarily environmental migrants (McDonnell Citation2019; Evertsen and van der Geest Citation2019), this was a much coveted migration destination. Indeed, some of the landless single mothers in Lonanodi asked if I could help their daughters get work in the Dhaka RMG sector.

But these migration choices were not only economic. Salma was one of my closest interlocutors. At the time of my fieldwork, she was a divorced single mother in her mid-twenties living with her young daughter and divorced mother. Salma’s father left them at an early age, and she grew up in the lush homestead compound of her maternal grandparents in Dhanmarti. At the age of 16, Salma went with a distant female ‘relative’ to work in the Dhaka RMG industry. As the earthwork project was ending, she was considering re-migrating to Dhaka RMG, but this time with her new secret partner. Like in Yasmine’s case, intimate relations shaped Salma’s desire to migrate, while her kinship relations provided her with the reproductive support to raise her child in Nodi while she was working in Dhaka.

Migration to the gulf: social stigma as a key gendered vulnerability

These romantic choices are kept highly secret also due to the wider societal stigmatisation of working-class women without husbands, be they young and single, widows or divorcés/abandoned. In the past and present, unmarried/divorced/widowed women of poorer classes often faced social stigma when working outside side of the home. Women workers in the jute mills were increasingly seen as breaking rules of conduct for women and received negative treatment by their male colleagues (Engels Citation1996). By the 1920s, these women workers were deemed as social outcasts (Sangari and Vaid Citation1990) and were negatively described as ‘disease-ridden’, ‘degraded’ and engaging in open prostitution (Curjel Citation1923). Similarly, women migrating to Dhaka or the Middle East today are perceived to be engaging in sexual work/relations. Salma, who met her ex (and father of her child) while working in Dhaka, emphasised that she lived with a family with strict controls, not at girls’ hostels:

When you have six to seven girls living together in a mess [hostel], they can go wherever they want. They have too much freedom; they can go to parks and live like bachelors. No one asks what they are doing. They can stay out late at night, meet boys. There are various problems with these things; they can have [extra-marital] affairs.

Yet, Salma told me how three women from their village had already gone to the Middle East for domestic work via a locally based labour broker. The broker approached Salma and offered a two-year work contract in Oman. She knew the families receiving remittances were doing well. Despite her good relations to her maternal uncles and their wives, Salma pointed out: ‘It is uncommon that brothers allow their sisters to inherit. We must plan for the day my grandfather is no longer here … we must save up money to buy our own homestead land we can live on’. Salma’s 40-year-old divorced single mother Jhorna, worried about the [sexual] risks and Salma’s safety, stating that Salma was too young and beautiful and that she would rather go in her place. The broker agreed and said the fee would only be 30,000 taka. Afterwards, Salma regretted the decision:

Once we started the process of training, tickets and applying for passports, the cost went up to 50,000 taka. We have spent 80,000 taka in total. We feel cheated. We borrowed 60,000 taka and I used 20,000 taka of my own savings. Now my mother is crying daily. They’re making her work in two homes rather than just one.

Jhorna struggled for the first few months and homesickness was a common issue for many of the men and women going to work abroad as they struggled to adapt, without their kin, in a foreign country, surrounded by a foreign language and foreign foods. Salma confided that she will not recommend any woman to work in the Middle East as a domestic worker: ‘It’s better to be a beggar in Bangladesh, than indebted there’. Salma pleaded with Jhorna to stay another six months so that they could at least repay the loans taken to migrate. If Jhorna broke her contract and returned earlier, the journey to Oman would have been for nothing; they would not have acquired the savings needed to buy land and would be forced to migrate elsewhere (such as the Dhaka RMG sector) to repay their loans.

Among my interlocutors, climate or environmental reasons were never given as a cause of migration to the Gulf. Prior to my fieldwork, I mistakenly assumed that extreme poor women and female-headed households would not have the financial resources to migrate internationally as domestic workers.Footnote7 Yet Salma and her colleagues did consider such options, borrowing from brokers to migrate. For example, Sahira a youthful and attractive divorced single mother living in her brother’s homestead compound in Lonanodi village was considering an offer from her cousin’s friend in Dhaka to help her get a job in Saudi Arabia after her earthwork project ended: ‘I only have to pay 30,000 taka for a two-year contract, they will arrange the rest’. I recalled Salma and her mother’s experience and the costs of visas and flights, none of which could be covered by a 30,000-taka fee.

Her colleagues pointed out that she did not know this dallal [broker] and began to discuss the risks of sexual exploitation of domestic workers abroad covered in the newspapers. Afrina, the oldest, was the most critical:

We do not want to send our daughters/girls to Arab countries. They [the brokers] only want young and beautiful girls. We have read in the papers that these returned girls were tortured. Did you know that one of our Ministers said that when Bangladeshi girls are being exploited in Bangladesh, they might as well be exploited in Saudi and earn good money?

Discussion and conclusion

Countries of the Global South have been subject to colonial powers and external actors (donors, corporations) intervening in their societies, economies – and their environments – for centuries. Development interventions such as embankments, brackish tiger-prawn cultivation for exports and agrochemical-dependent high-yield agriculture fundamentally change and renders more vulnerable Bangladesh’s deltaic wetlands, exacerbating risks to climatic change (Dewan Citation2021b). Development interventions supposed to help Bangladesh adapt to climatic change may actually worsen the social vulnerability that they are supposed to address by removing focus from how such socio-ecological vulnerabilities are compounded by the lack of state provision in an aid-dependent landscape. This in turn results in high out-of-pocket expenditure for healthcare, education and labour brokering costs – fuelling rural indebtedness.

Combining environmental history, political economy and historiographies of working class women in Bengal with long-term ethnography with landless single mothers in the southwest coastal zone of Bangladesh reveal how longstanding agrarian injustices and gender-based constraints contribute to migration choices. Such historically anchored ethnography yields insights into agrarian political economy which can be leveraged against simplified understandings of contemporary migration being caused by climate change. Any discussion on ‘climate displacement’ in agrarian worlds drastically changing due to environmental degradation and climatic change must also therefore take into account changing political economies and the importance of migration as a rural livelihood strategy. Labour migration continues to be important for Bangladeshis. Contrary to beliefs that Bangladeshi [Muslim] women are more sedentary and extra ‘climate vulnerable’, working-class women in Bengal have a history of migrating for work, especially divorcées and widows.

Attention to environmental history further sheds light on various forms of misreading of ‘climate displacement’ in Bangladesh, an iconic symbol of a ‘climate change victim’ that is portrayed as drowning in rising sea levels. Firstly, the long-term salinisation of arable lands by brackish aquaculture has contributed to rural hardship and outmigration since it was introduced to the coastal zone already in the early 1990s as its damages to embankments have further contributed to cyclone-related migration. Secondly, waterlogging floods are deeply entangled with man-made infrastructure impeding the drainage of monsoon rains. Thirdly, land being ‘swallowed by the river’ is due to river-bank erosion (rather than floods) and is a geological feature of the Ganges. By portraying river-bank displaced peoples, migrants from tiger-prawn producing villages and people suffering from waterlogging as ‘climate refugees’-political solutions are ignored such as land-compensation schemes, stopping shrimp farming, and remediating the flaws of flood-protection embankments through tidal river management and regular canal excavation through rural employment schemes.

A healthy ecology is crucial for cottage-based crafts and rural livelihoods, where women in saline Lonanodi faced greater hardship than those in freshwater Dhanmarti. Yet, due to debt and high costs of living, women were migrating from both these unions. Like rural women in colonial times, lack of rural income motivated them to work outside the home and village. Though the jute industry is no longer as important as it once was, Dhaka’s export-oriented garment industries resembles the Mughal textile industries by being one of the main employers of working class women, particularly those without adult male earners. In the 1920s and 1930s, agrarian crisis resulted in many women working as domestic workers in Bengali cities, today they go to the Middle East. But as this ethnography shows, women migrated not only due to environmental degradation, debt or aspirations to increase incomes but to also be with their secret romantic partners. The ability of landless, divorced single mothers to migrate depended on their reproductive kinship support and their social relations that could help them migrate safely. Indeed, some women chose not to migrate due to the social stigmatisation of migrant women, especially those migrating to the Middle East as domestic workers or to Dhaka RMG – both high-income destinations.

To conclude, climate reductive translations of migration misread coastal vulnerabilities and the push factors of migration and ignore the heterogeneity of women and their differential agentive capacities, thereby failing to address policy solutions that remediate rural underemployment, floods, riverbank erosion and salinisation by aquaculture. By highlighting the disconnect between development policy discourses with everyday gendered lived experiences of socio-environmental agrarian vulnerabilities, this article contributes to the growing critical scholarship on climate adaptation, migration and development and ‘agrarian worlds on the move’.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this article is based was funded by a Bloomsbury Colleges studentship from the University of London (Birkbeck College and SOAS) and writing up was funded by the Norwegian Research Council [grant number 275204/F10]. I am indebted to my (sister-)interlocutors in Nodi who shared their lives with me. I am grateful for comments on early versions of this article from David Mosse, Penny Vera-Sanso, Katy Gardner, James Fairhead, Caroline Osella and Christopher Davis. Thanks to Nicholas Loubere, Nari Senanayake, Anwesha Dutta and Elisabeth Schober, as well as the participants of the 2022 AAG panel ‘Conceptualizing Climate Displacement in an Agrarian World Already on the Move’ and Session 11 of the 2022 JPS Climate Change and Agrarian Justice conference for critical and constructive comments. Special thanks to Annie Shattuck, as well as to the four anonymous reviewers for their excellent feedback and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Camelia Dewan

Camelia Dewan is an environmental anthropologist focusing on the anthropology of development and author of Misreading the Bengal Delta: Climate Change, Development and Livelihoods in Coastal Bangladesh (2021, University of Washington Press). She holds a PhD in Social Anthropology and Environment from the University of London (SOAS/Birkbeck). As a postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo, she is examining the socio-environmental effects of shipbreaking in Bangladesh. She is the co-editor of two special issues Fluid Dispossessions: Contested Waters in Capitalist Natures (Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology) and Scaled Ethnographies of Toxic Flows (Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space).

Notes

1 Words in italics are in Bangla unless otherwise indicated.

2 By translation I refer to the processes by which development brokers produce coherence [make projects real] by stabilising representations so as to match causal events to the prevailing policy theory (Mosse and Lewis Citation2006, 13; Mosse Citation2005, 9) This draws on Latour’s use of translation ‘as a relation that does not transport causality but induces two mediators into coexisting [with each other]’ (Latour Citation2005, 108).

3 All names have been changed to protect the anonymity of my interlocutors. I obtained oral informed consent by explaining to each interlocutor the purpose of my work, who I am, what my affiliations were, the nature of my research, that I was not part of a project that they could benefit from and that all information would be anonymised. I asked open-ended questions about environmental change and livelihood strategies and qualitatively analysed the transcripts of these conversations. I obtained ethics approval for this fieldwork from the Department of Social Anthropology, SOAS (University of London).

4 Cited from B.N Banerjee op.cit, Vol II, pp. 336–337 in Chattopadhyay (Citation1990).

5 With the rapid mechanisation of the 1970s Green Revolution, landless women lost their main income source from processing rice (Greeley Citation1987).

6 Bangladeshi researchers I met stated that up until 2015 there had been no conclusive study confirming that climatic change is exacerbating nodi bhangon.

7 Research on Bangladeshi domestic workers migrating to the Middle East and South East Asia has already been long established (Gardner Citation1995; Siddiqui Citation2001). In recent years, the Government of Bangladesh has implemented incentives to recruit women to work abroad as domestic workers (Migrant Rights Citation2016).

References

- Adnan, Shapan. 2013. “Land Grabs and Primitive Accumulation in Deltaic Bangladesh: Interactions Between Neoliberal Globalization, State Interventions, Power Relations and Peasant Resistance.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 40 (1): 87–128. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.753058

- Adri, Neelopal, and David Simon. 2018. “A Tale of Two Groups: Focusing on the Differential Vulnerability of “Climate-Induced” and “Non-Climate-Induced” Migrants in Dhaka City.” Climate and Development 10 (4): 321–336. doi:10.1080/17565529.2017.1291402.

- Afsar, Rita. 2003. Internal Migration and the Development Nexus: The Case of Bangladesh. Dhaka: Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit and UK Department for International Development.

- Ahsan, Reazul. 2019. “Climate-Induced Migration: Impacts on Social Structures and Justice in Bangladesh.” South Asia Research 39 (2): 184–201. doi:10.1177/0262728019842968.

- Amrith, Sunil S. 2014. “Currents of Global Migration.” Development and Change 45 (5): 1134–1154. doi:10.1111/dech.12109

- Amrith, Sunil S. 2018. “Risk and the South Asian Monsoon.” Climatic Change 151 (1): 17–28. doi:10.1007/s10584-016-1629-x.

- Arora-Jonsson, Seema. 2011. “Virtue and Vulnerability: Discourses on Women, Gender and Climate Change.” Global Environmental Change 21 (2): 744–751. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.005.

- Auerbach, L. W., S. L. Goodbred Jr, D. R. Mondal, C. A. Wilson, K. R. Ahmed, K. Roy, M. S. Steckler, C. Small, J. M. Gilligan, and B. A. Ackerly. 2015. “Flood Risk of Natural and Embanked Landscapes on the Ganges–Brahmaputra Tidal Delta Plain.” Nature Climate Change 5 (2): 153–157. doi:10.1038/nclimate2472.

- Bakare-Yusuf, Bibi. 2013. “Thinking with Pleasure: Danger, Sexuality and Agency.” In Women, Sexuality and the Political Power of Pleasure. Feminisms and Development, edited by Susie Jolly, Andrea Cornwall, and Kate Hawkins, 28–41. London: Zed Books.

- Banerjee, Nirmala. 1990. “Working Women in Colonial Bengal: Modernization and Marginalization.” In Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History, edited by Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid, 269–301. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Banerjee, Subhabrata Bobby, and Laurel Jackson. 2017. “Microfinance and the Business of Poverty Reduction: Critical Perspectives from Rural Bangladesh.” Human Relations 70 (1): 63–91. doi:10.1177/0018726716640865.

- Barnes, Jessica, and Michael Dove. 2015. Climate Cultures: Anthropological Perspectives on Climate Change. Yale Agrarian Studies Series. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Basu, Subho. 2008. “The Paradox of Peasant Worker: Re-Conceptualizing Workers’ Politics in Bengal 1890-1939.” Modern Asian Studies 42 (1): 47–74. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0700279X.

- Bernzen, Amelie, J. Jenkins, and Boris Braun. 2019. “Climate Change-Induced Migration in Coastal Bangladesh? A Critical Assessment of Migration Drivers in Rural Households Under Economic and Environmental Stress.” Geosciences 9 (1): 51. doi:10.3390/geosciences9010051.

- Borras Jr., Saturnino M., Ian Scoones, Amita Baviskar, Marc Edelman, Nancy Lee Peluso, and Wendy Wolford. 2022. “Climate Change and Agrarian Struggles: An Invitation to Contribute to a JPS Forum.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1080/03066150.2021.1956473.

- Brammer, Hugh. 2012. The Physical Geography of Bangladesh. Dhaka: The University Press.

- Cannon, Terry. 2009. “Gender and Climate Hazards in Bangladesh.” In Climate Change and Gender Justice. Working in Gender & Development, edited by Geraldine Terry, 54–70. Oxford, UK: Practical Action; Oxfam.

- Chatterjee, Partha. 1982. “Agrarian Structure in Pre-Partition Bengal.” In Three Studies on the Agrarian Structure in Bengal 1850-1947, edited by Asok Sen, Partha Chatterjee, and Saugata Mukherji, 113–224. Calcutta: Centre for Studies in Social Sciences.

- Chattopadhyay, Dilip Kumar. 1990. Dynamics of Social Change in Bengal, 1817-1851. Calcutta: Punthi Pustak.

- Chaturvedi, Sanjay, and Timothy Doyle. 2010. “Geopolitics of Fear and the Emergence of ‘Climate Refugees’: Imaginative Geographies of Climate Change and Displacements in Bangladesh.” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 6 (2): 206–222. doi:10.1080/19480881.2010.536665.

- Collectif Argos. 2010. Climate Refugees. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cons, Jason. 2018. “Staging Climate Security: Resilience and Heterodystopia in the Bangladesh Borderlands.” Cultural Anthropology 33 (2): 266–294. doi:10.14506/ca33.2.08.

- Cuomo, Chris J. 2011. “Climate Change, Vulnerability, and Responsibility.” Hypatia 26 (4): 690–714. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2011.01220.x

- Curjel, Dagmar F. 1923. Women’s Labour in Bengal Industries. Bulletins of Indian Industries and Labour 31. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing.

- Deb, Apurba Krishna. 1998. “Fake Blue Revolution: Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts of Shrimp Culture in the Coastal Areas of Bangladesh.” Ocean & Coastal Management 41 (1): 63–88. doi:10.1016/S0964-5691(98)00074-X

- Dewan, Camelia. 2020. “‘Climate Change as a Spice’: Brokering Environmental Knowledge in Bangladesh’s Development Industry.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 87 (3): 538–559. doi:10.1080/00141844.2020.1788109.

- Dewan, Camelia. 2021a. “Embanking the Sundarbans: The Obfuscating Discourse of Climate Change.” In The Anthroposcene of Weather and Climate: Ethnographic Contributions to the Climate Change Debate, edited by Paul Sillitoe, 294–321. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Dewan, Camelia. 2021b. Misreading the Bengal Delta: Climate Change, Development, and Livelihoods in Coastal Bangladesh. Culture, Place, and Nature. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Dewan, Camelia, Aditi Mukherji, and Marie-Charlotte Buisson. 2015. “Evolution of Water Management in Coastal Bangladesh: From Temporary Earthen Embankments to Depoliticized Community-Managed Polders.” Water International 40 (3): 401–416. doi:10.1080/02508060.2015.1025196

- Engels, Dagmar. 1996. Beyond Purdah? Women in Bengal 1890-1939. SOAS Studies on South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Eriksen, Siri H., Andrea J. Nightingale, and Hallie Eakin. 2015. “Reframing Adaptation: The Political Nature of Climate Change Adaptation.” Global Environmental Change 35 (November): 523–533. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.014.

- Etzold, Benjamin, and Bishawjit Mallick. 2016. “Moving Beyond the Focus on Environmental Migration Towards Recognizing the Normality of Translocal Lives: Insights from Bangladesh.” In Migration, Risk Management and Climate Change: Evidence and Policy Responses. Global Migration Issues, edited by Andrea Milan, Benjamin Schraven, Koko Warner, and Noemi Cascosne, 105–128. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Evertsen, Kathinka Fossum, and Kees van der Geest. 2019. “Gender, Environment and Migration in Bangladesh.” Climate and Development 0 (0): 1–11. doi:10.1080/17565529.2019.1596059.

- Fairbairn, Madeleine, Jonathan Fox, S. Ryan Isakson, Michael Levien, Nancy Peluso, Shahra Razavi, Ian Scoones, and K. Sivaramakrishnan. 2014. “Introduction: New Directions in Agrarian Political Economy.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (5): 653–666. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.953490.

- Fairhead, James, and Melissa Leach. 1996. Misreading the African Landscape: Society and Ecology in a Forest-Savanna Mosaic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Faraizi, Aminul Haque. 1993. Bangladesh: Peasant Migration and the World Capitalist Economy. South Asian Publications Series, Asian Studies Association of Australia, no. 8. New Delhi: Sterling.

- Farbotko, Carol, and Heather Lazrus. 2012. “The First Climate Refugees? Contesting Global Narratives of Climate Change in Tuvalu.” Global Environmental Change 22 (2): 382–390. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.11.014

- Feldman, Shelley, and Charles Geisler. 2012. “Land Expropriation and Displacement in Bangladesh.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (3–4): 971–993. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.661719

- Gardner, Katy. 1995. Global Migrants, Local Lives: Travel and Transformation in Rural Bangladesh. Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Gardner, Katy, and David Lewis. 2015. Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century. London: Pluto Press.

- Gidwani, Vinay, and Priti Ramamurthy. 2018. “Agrarian Questions of Labor in Urban India: Middle Migrants, Translocal Householding and the Intersectional Politics of Social Reproduction.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (5–6): 994–1017. doi:10.1080/03066150.2018.1503172.

- Government of Bangladesh. 1976. Deadlock on the Ganges. Dhaka: Ministry of Water, Government of Bangladesh.

- Greeley, Martin. 1987. Postharvest Losses, Technology, and Employment: The Case of Rice in Bangladesh. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Guhathakurta, Meghna. 2003. “Globalisation, Class and Gender Relations: The Shrimp Industry in Southwestern Bangladesh.” In Globalisation, Environmental Crisis, and Social Change in Bangladesh, edited by Matiur Rahman, 295–308. Dhaka: The University Press.

- Hulme, Mike. 2011. “Reducing the Future to Climate: A Story of Climate Determinism and Reductionism.” Osiris 26 (1): 245–266. doi:10.1086/661274.

- International Organization for Migration. 2010. Assessing the Evidence: Environment, Climate Change and Migration in Bangladesh. Dhaka: International Organization for Migration.

- Iqbal, Iftekhar. 2010. The Bengal Delta: Ecology, State and Social Change, 1840-1943. Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Islam, Rafiqul, Susanne Schech, and Udoy Saikia. 2021. “Climate Change Events in the Bengali Migration to the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) in Bangladesh.” Climate and Development 13 (5): 375–385. doi:10.1080/17565529.2020.1780191.

- Islam, M Rezaul, and M. Shamsuddoha. 2017. “Socioeconomic Consequences of Climate Induced Human Displacement and Migration in Bangladesh.” International Sociology 32 (3): 277–298. doi:10.1177/0268580917693173.

- Ito, S. 2002. “From Rice to Prawns: Economic Transformation and Agrarian Structure in Rural Bangladesh.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 29 (2): 47–70. doi:10.1080/714003949.

- Jacka, Tamara. 2017. “Translocal Family Reproduction and Agrarian Change in China: A New Analytical Framework.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (7): 1341–1359. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1314267.

- Jamaly, R., and E. Wickramanayake. 1996. “Women Workers in the Garment Industry in Dhaka, Bangladesh.” Development in Practice 6 (2): 156–161.

- Jolly, Stellina, and Nafees Ahmad. 2019. “Climate Refugees: The Role of South Asian Judiciaries in Protecting the Climate Refugees.” In Climate Refugees in South Asia: Protection Under International Legal Standards and State Practices in South Asia. International Law and the Global South, edited by Stellina Jolly and Nafees Ahmad, 203–254. Singapore: Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-3137-4_6.

- Kabeer, Naila. 1991. “Gender Dimensions of Rural Poverty: Analysis from Bangladesh.” Journal of Peasant Studies 18 (2): 241–262. doi:10.1080/03066159108438451.

- Kabeer, Naila. 2000. The Power to Choose: Bangladeshi Women and Labour Market Decisions in London and Dhaka. New York: Verso Books.

- Karim, Lamia. 2011. Microfinance and Its Discontents: Women in Debt in Bangladesh. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kartiki, Katha. 2011. “Climate Change and Migration: A Case Study from Rural Bangladesh.” Gender & Development 19 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1080/13552074.2011.554017.

- Kelley, Lisa C., Annie Shattuck, and Kimberley Anh Thomas. 2021. “Cumulative Socionatural Displacements: Reconceptualizing Climate Displacements in a World Already on the Move.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 0 (0): 1–10. doi:10.1080/24694452.2021.1960144.

- Kelman, Ilan. 2022. “Pakistan’s Floods Are a Disaster – But They Didn’t Have to Be.” The Conversation (blog), 20 September 2022. http://theconversation.com/pakistans-floods-are-a-disaster-but-they-didnt-have-to-be-190027.

- Khan, Zahirul H., F. A. Kamal, N. A. A. Khan, S. H. Khan, M. M. Rahman, M. S. A. Khan, A. K. M. S. Islam, and Bharat R. Sharma. 2015. “External Drivers of Change: Scenarios and Future Projections of the Surface Water Resources in the Ganges Coastal Zone of Bangladesh.” In Revitalizing the Ganges Coastal Zone: Turning Science Into Policy and Practices Conference Proceedings, edited by Elizabeth Humphreys, T. P. Tuong, Marie-Charlotte Buisson, I. Pukinskis, and Michael Phillips, 27–38. Colombo: CGIAR Challenge Program on Water and Food (CPWF).

- Lahiri-Dutt, K., and G. Samanta. 2004. “Fleeting Land, Fleeting People: Bangladeshi Women in a Charland Environment in Lower Bengal, India.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal : APMJ 13 (4): 475–495. doi:10.1177/011719680401300404.

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, David. 1993. “Going It Alone: Female-Headed Households, Rights and Resources in Rural Bangladesh.” European Journal of Development Research 5 (2): 23–42. doi:10.1080/09578819308426586.

- Lewis, David. 2010. “The Strength of Weak Ideas? Human Security, Policy History, and Climate Change in Bangladesh.” Critical Interventions 11: 113–129.

- Lovatt, Joanna. 2016. “The Bangladesh Shrimp Farmers Facing Life on the Edge.” The Guardian, 17 February 2016, sec. Global Development Professionals Network. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/feb/17/the-bangladesh-shrimp-farmers-facing-life-on-the-edge.

- McDonnell, Tim. 2019. “Climate Change Creates a New Migration Crisis for Bangladesh.” National Geographic, 24 January 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/01/climate-change-drives-migration-crisis-in-bangladesh-from-dhaka-sundabans/.

- Mehta, Rimple. 2018. Women, Mobility and Incarceration: Love and Recasting of Self Across the Bangladesh-India Border. London: Routledge.

- Momsen, Janet Henshall. 2003. Gender and Development. Routledge Perspectives on Development. London: Routledge.

- Montu, Rafiqul Islam. 2020. “‘It’s over for Us’: How Extreme Weather Is Emptying Bangladesh’s Villages.” The Guardian, 16 December 2020, sec. Global Development. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/dec/16/how-floods-are-emptying-bangladesh-villages.

- Mosse, David. 2005. Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. London: Pluto Press.

- Mosse, David, Sanjeev Gupta, Mona Mehta, Vidya Shah, Julia Fnms Rees, and KRIBP Project Team. 2002. “Brokered Livelihoods: Debt, Labour Migration and Development in Tribal Western India.” Journal of Development Studies 38 (5): 59–88. doi:10.1080/00220380412331322511

- Mosse, David, and David Lewis. 2006. “Theoretical Approaches to Brokerage and Translation in Development.” In Development Brokers and Translators: The Ethnography of Aid and Agencies, edited by David Lewis and David Mosse, 1–26. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Nikitas, Stefanos. 2016. “Haunting Photos Show Effects of Climate Change in Bangladesh.” The Huffington Post, 28 January 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/bangladesh-climate-change_us_56aa5cd8e4b0d82286d53900.

- Ojeda, Diana. 2021. “Social Reproduction, Dispossession, and the Gendered Workings of Agrarian Extractivism in Colombia.” In Agrarian Extractivism in Latin America. Routledge Critical Development Series, edited by Ben M. McKay, Alberto Alonso Fradejas, and Arturo Ezquerro-Cañete, 85–98. New York, NY: Routledge.

- O’Malley, L. S. S. 1908. “Bengal District Gazetteers: Khulna.” Calcutta. V/27/62/111. India Office Records, British Library.

- Paprocki, Kasia. 2016. “‘Selling Our Own Skin’: Social Dispossession Through Microcredit in Rural Bangladesh.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 74 (August): 29–38. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.05.008.

- Paprocki, Kasia. 2018. “Threatening Dystopias: Development and Adaptation Regimes in Bangladesh.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (4): 955–973. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1406330.

- Paprocki, Kasia. 2019a. “All That Is Solid Melts Into the Bay: Anticipatory Ruination and Climate Change Adaptation.” Antipode 51 (1): 295–315. doi:10.1111/anti.12421

- Paprocki, Kasia. 2019b. “The Climate Change of Your Desires: Climate Migration and Imaginaries of Urban and Rural Climate Futures.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, December, 026377581989260.

- Paprocki, Kasia, and Jason Cons. 2014. “‘Life in a Shrimp Zone: Aqua- and Other Cultures of Bangladesh’s Coastal Landscape’.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6): 1109–1130. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.937709.

- Poncelet, A., F. Gemenne, M. Martiniello, and H. Bousetta. 2010. “A Country Made for Disasters: Environmental Vulnerability and Forced Migration in Bangladesh.” In Environment, Forced Migration and Social Vulnerability, edited by Tamer Afifi and Jill Jèager, 211–222. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin.

- Pouliotte, Jennifer, Barry Smit, and Lisa Westerhoff. 2009. “Adaptation and Development: Livelihoods and Climate Change in Subarnabad, Bangladesh.” Climate and Development 1 (1): 31–46. doi:10.3763/cdev.2009.0001.

- Powdermaker, Hortense. 1966. Stranger and Friend: The Way of an Anthropologist. Nachdr. New York: Norton & Company.

- Qureshi, Ayaz. 2014. “‘Up-Scaling Expectations among Pakistan’s HIV Bureaucrats: Entrepreneurs of the Self and Job Precariousness Post-Scale-Up’.” Global Public Health 9 (1–2): 73–84. doi:10.1080/17441692.2013.870590.

- Rahman, Rushidan I., and Rizwanul Islam. 2013. Female Labour Force Participation in Bangladesh: Trends, Drivers and Barriers. ILO Asia-Pacific Working Paper Series. New Delhi: International Labour Organization. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_250112.pdf.

- Rahman, Mahbubar, and Willem Van Schendel. 2003. ““I Am Not a Refugee”: Rethinking Partition Migration.” Modern Asian Studies 37 (3): 551–584. doi:10.1017/S0026749X03003020.

- Rights, Migrant. 2016. “Saudi Lifts Ban on Bangladeshi Workers, While Ignoring Plight of Thousands of Stranded Workers,” 12 August 2016. https://www.migrant-rights.org/2016/08/saudi-lifts-ban-on-bangladeshi-workers-while-ignoring-plight-of-thousands-of-stranded-workers/.

- Rogaly, Ben, Daniel Coppard, Abdur Safique, Kumar Rana, Amrita Sengupta, and Jhuma Biswas. 2002. “Seasonal Migration and Welfare/Illfare in Eastern India: A Social Analysis.” Journal of Development Studies 38 (5): 89–114. doi:10.1080/00220380412331322521

- Saha, Sebak Kumar. 2017. “Cyclone Aila, Livelihood Stress, and Migration: Empirical Evidence from Coastal Bangladesh.” Disasters 41 (3): 505–526. doi:10.1111/disa.12214

- Samaddar, Ranabir. 1999. The Marginal Nation: Transborder Migration from Bangladesh to West Bengal. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Sangari, Kumkum, and Sudesh Vaid. 1990. “Introduction: Recasting Women.” In Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History, Edited by Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Seeley, J., S. Ryan, M. I. Hossain, and I. A. Khan. 2006. “Just Surviving or Finding Space to Thrive? The Complexity of the Internal Migration of Women in Bangladesh.” In Poverty, Gender and Migration, edited by S. Arya and A. Roy, 171–191. London: SAGE Publications.

- Sen, Samita. 1999. Women and Labour in Late Colonial India: The Bengal Jute Industry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shah, Alpa. 2006. “The Labour of Love: Seasonal Migration from Jharkhand to the Brick Kilns of Other States in India.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 40 (1): 91–118. doi:10.1177/006996670504000104.

- Siddiqui, Tasneem. 2001. Transcending Boundaries: Labour Migration of Women from Bangladesh. University Press: Dhaka.

- Silva, Sanjiv de. 2012. “Situation Analysis for Polder 3. [Project Report Prepared by IWMI for the CGIAR Challenge Program on Water and Food (CPWF) under the Project “Increasing the Resilience of Agricultural and Aquacultural Systems in the Coastal Areas of the Ganges Delta: Project G3 - Water Governance and Community Based Management”].” Report. International Water Management Institute (IWMI). https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/41802.

- Staveren, Martijn F. van, Jeroen F. Warner, and M. Shah Alam Khan. 2017. “Bringing in the Tides. From Closing Down to Opening up Delta Polders via Tidal River Management in the Southwest Delta of Bangladesh.” Water Policy 19 (1): 147–164. doi:10.2166/wp.2016.029.

- Swain, Ashok. 1996. “The Environmental Trap: The Ganges River Diversion, Bangladeshi Migration and Conflicts in India.” Report, Uppsala University, Department of Peace and Conflict Research, No. 41. Uppsala, Sweden: Dept. of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University.

- Swapan, Mohammad Shahidul Hasan, and Michael Gavin. 2011. “A Desert in the Delta: Participatory Assessment of Changing Livelihoods Induced by Commercial Shrimp Farming in Southwest Bangladesh.” Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.10.011

- Toufique, Kazi Ali. 2002. “‘Agricultural and Non-Agricultural Livelihoods in Rural Bangladesh: A Relationship in Flux’.” In Hands Not Land: How Livelihoods Are Changing in Rural Bangladesh, edited by Kazi Ali Toufique and Cathryn Turton, 57–64. Dhaka: Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

- UNDP. 2019. “CBA Bangladesh: Coping with Climate Risks by Empowering Women in Coastal Areas (GBSS) | UNDP Climate Change Adaptation.” https://projects/spa-cba-bangladesh-coping-climate-risks-empowering-women-coastal-areas-gbss.

- Van Schendel, Willem. 2001. “Working Through Partition: Making a Living in the Bengal Borderlands.” International Review of Social History 46 (03): 393–421. doi:10.1017/S0020859001000256.

- Werner, Marion. 2016. Global Displacements: The Making of Uneven Development in the Caribbean. Antipode Book Series. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- World Bank. 2009. “Poverty and Climate Change: Reducing the Vulnerability of the Poor through Adaptation.” Working Paper 52176. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/534871468155709473/Poverty-and-climate-change-reducing-the-vulnerability-of-the-poor-through-adaptation.

- Zaman, M. Q. 1993. “Rivers of Life: Living with Floods in Bangladesh.” Asian Survey 33 (10): 985–996. doi:10.2307/2645097.