ABSTRACT

This paper answers calls from the food regime scholarship for a closer analysis of the implicit rules, transitions, and regional scales of food regimes. Drawing on archival materials from the Japanese colonial administration and Sino-American agricultural cooperation, interviews with key actors, and secondary sources, this paper examines instances of agricultural knowledge production and exchange. We suggest that beyond the profound influence of the US in the postwar food regime, the nuances and historical and regional specificity of agricultural scientists’ life stories and individual technological imaginaries can ‘scale up’ through the translation of agrarian knowledge.

Introduction

In the process of ‘discovering’ and developing desirable lands and resources, colonizers invented modern agricultural systems and mechanisms of knowledge production and circulation. Elucidating these colonial roots of contemporary agrarian systems has become a vibrant field of research (Azuma Citation2019; Patel Citation2013; Waldmueller Citation2015; Wang Citation2018; Wolford Citation2021), which we seek to extend by showing how colonial practices evolved and are implicated in postwar and contemporary food regimes. Appreciating both the ‘new food regime geographies’ (Jakobsen Citation2021) and ‘the power of small stories’ (Campbell Citation2020), this study examines regional food regimes in Asia through the lens of Taiwan and parts of Southeast Asia – as they were embedded in the empires of prewar Japan and Cold War American hegemony. Careful attention to regional scale (McMichael Citation2013, Citation2020; Rioux Citation2018) and implicit rules (Friedmann Citation1993, Citation2016) reveals how the technological imaginaries guiding the actions of Asian agricultural experts were influenced not only by colonial and modern agrarian development doctrines, but also by regional contingencies that shaped their agricultural institutions. Evoking the nuances and historical specificity of their roles sheds further light on the variegated pathways in the (re)location(s) of modern agriculture in Asia.Footnote1

As the Japanese empire expanded during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it tried to modernize agriculture in its new territories and incorporate them into an imperial division of labor similar to the UK-centered first food regime. It succeeded in modernizing rice and sugar agriculture in Taiwan and Korea, establishing secure sources of cheap food for the imperial economy (Chang and Myers Citation1963; Cumings Citation1984; Ka Citation1995; Myers Citation1984; Myers and Yamada Citation1984). After 1945, working through its Cold War hegemonic umbrella, the United States reshaped the food systems of occupied Japan and its former colonies, including Taiwan, in accordance with the second food regime; China and some parts of Southeast Asia remained outside the system of alliances and followed different paths. Studies of divergent paths of postwar agrarian development in Asia – whether capitalistic green revolutions or communist-inspired red revolutions – have traced them to different colonial experiences (McMichael Citation2005; Schmalzer Citation2016; Stross Citation1986); we seek to add nuance to the view that modern agrarian scientific institutions and agronomists within the US-led coalition in Asia pursued similar patterns of development. There continues to be insufficient understanding of the complex and disparate regimes of agrarian knowledge production and circulation underlying these divergent trajectories. Likewise, McMichael’s (Citation2020) view of China’s BRIC initiatives in the context of ‘agro-security mercantilism’ has contributed to deepening our understanding of the multipolar patterning of contemporary food regimes in Asia, with its deliberation on the rising neomercantilism at the Asian regional scale. Yet, without a further note on the ‘old’ mercantilism in Asia, such as the food systems centered on the Japanese empire and the US Cold War regime, the historical transitions of the food regimes in the context of ‘rising China’ (Arrighi Citation2007), cannot be clearly explained.

This study follows Azuma Eiichiro’s In Search of Our Frontier (Citation2019), which emphasizes the role of Japanese (American) agricultural experts in expanding the formal empire of Japan in Asia (ishokumin) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but shifts attention to the postwar era, focusing not only on the role of agrarian experts, who felt the influence of colonial doctrine in making a borderless empire, but also on the rules and institutions they utilized to shape modern agrarian development in different parts of Asia. Patel’s (Citation2013) notion of the ‘Long Green Revolution’ reminds us that there were different modes of agricultural modernization in different parts of the world under the concept of a ‘green revolution.’ These modes were especially varied in the ways in which they linked governments, non-profit organizations (NPOs), and food corporations to legitimatize certain knowledge systems and facilitate mobilization of agricultural development projects by governments or states. In addition, Patel (Citation2013) suggests that the demand for food security and its governance structures formed the discourse that states used to justify their expansion to seek out agri-food sources in hitherto untapped territories during the postwar period. In this way, the ‘New Green Revolution’ is tied closely to Cold War geopolitics and territorial strategies and presents an avenue for reconsidering the internal links and transitions of food regimes. Schmalzer (Citation2016) parallels ‘red revolution’ and ‘green revolution’ to suggest that the socialist China (PRC) in the postwar era never adopted the idea of ‘green revolution,’ but rather, it mobilized the movement of so-called ‘scientific farming’ (namely: ‘red revolution’) to combine modern agricultural farming and traditional intensification (the Tu science) as a way to circumvent social and political revolution.

We follow Friedmann’s (Citation2016, 682) suggestion that ‘for food regime analysis, cumulative histories shape cycles via the sediments left by past cycles in each phase’. Studies have shown that colonial knowledge institutionalized by the Japanese empire contributed to the development of modern agriculture in Asia (Azuma Citation2019; Moore Citation2013); that Japanese colonies (including Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria) played key roles in the management and extension of Japan’s military logistics networks during World War II (Cumings Citation1984; Ka Citation1995; Kang and Hyun Citation2010); and that legacies of Japanese colonialism – resources, infrastructure, even human capital – were inherited by the US-dominated Cold War regime (Cumings Citation1984). But scholars have barely addressed their role in forming postwar food regimes in Asia. Even fewer studies have addressed the pivotal role that Taiwan (ROC), international agrarian research and development institutes, and the Sino-American Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction (JCRR, 1948–1979) played in modernizing Asian agriculture in the postwar period (Lin Citation2015; Wang Citation2018). The JCRR viewed the development of agriculture as a modernization project designed to improve agricultural productivity and foster development in order to combat communism.Footnote2 In this context, we address how the dynamics of agricultural modernization in Asia came together to shape transitions between food regimes that were localized in regional historical and geographical contexts. Our contribution is therefore to reveal the qualitative changes in the nature of the food regimes by reconceptualizing the transition from the first to the second food regimes and explaining how these changes might explain the emergence of the contemporary food regime.

The first section reviews recent efforts to regionalize the food regime framework and the need to incorporate implicit rules in the analysis. We then turn to the historical geography of modern agrarian development in Asia before and after 1945, using materials from the Japanese colonial administration and JCRR archives to discuss how these imperial regimes influenced the postwar development of agriculture in Asia. We also draw on interviews with key actors, diaries, memoirs, biographies, interviews, academic works, and state-produced materials.Footnote3 These resources enable us to examine the agrarian development of Asia through the lens of the story of Shen Zonghan, a leading figure in Asian agrarian development and the founding of the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) and the Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center (AVRDC). These stories show that international agricultural research institutes and philanthropic institutions built for ‘green revolutions’ in Asia prioritized opposing communism over ensuring food security. But they also demonstrate the importance of regionalizing food regime analysis and paying attention to the ‘small stories’ of implicit rules by showing how one individual’s imaginary can ‘scale up’ through the translation of agrarian development knowledge. Doing so helps advance explanation of food regime transitions in their colonial and postcolonial contexts. The paper concludes with a discussion of the wider implications for the formation of food regimes in Asia and how further research could benefit from incorporating the analyses of food regimes in Asia.

Reconsidering the postwar food regime in Asia

The food regime framework attempts to identify and explain the existence of, and shifts between, relatively stable spatio-temporal configurations articulating agriculture, food production, and consumption, and to show the roles these have played during different periods of capitalist globalization (Friedmann Citation1987; Friedmann and McMichael Citation1989; McMichael Citation2009, 2013). Combining political economy and historical analysis, this approach ‘prioritizes the way in which forms of accumulation in agriculture constitute global power arrangements’ (McMichael Citation2009, 141) and simultaneously how food regimes emerge out of political and economic processes. Until recently, the food regime literature tended to assume the UK- and US-centered first and second food regimes could explain most of what was important in the global food economy, overlooking other regional dynamics (McMichael Citation2013). In addition, though analyses examined how food regimes emerge out of social movements and powerful institutions, and thus reflect the negotiated frames for instituting new rules in agricultural development and food capitalism (Friedmann Citation2005, 234), they tended to downplay the complications of negotiated agency, especially in non-center regional dynamics. This section will address the need to regionalize the food regime literature, and pay more attention to the implicit rules in regional formations.

At this point it is useful to recall the characteristics of the three historical food regimes described in the literature. Simplified for analytical purposes, the first or ‘Colonial Project’ food regime (1870s–1930s) provided cheap food, labor, and raw materials from tropical occupation colonies and temperate settler colonies to facilitate industrialization in Europe (Friedmann and McMichael Citation1989; McMichael Citation2013). Metropole powers often shifted crops and techniques between locations like pieces on a chessboard, attempting to rationalize production based on geographies of climate and social relations (Wolford Citation2021). The second or ‘Development Project’ food regime (1950s–1970s) idealized food self-sufficiency at the level of discrete, Keynesian-inspired national economies. This ‘inner-directedness’ – industrializing agriculture for national interests – facilitated the incorporation of food consumption into an intensified capital accumulation that distinguished the US model of modernity (McMichael Citation2005). At the same time, the South-to-North flow of food was reversed with the transfer of US New Deal surpluses to Cold War allies in the Global South in the form of international food aid (Friedmann Citation1993; McMichael Citation2009, 2013). Shaped by efforts to contain communism, it sought political legitimation using ‘a state-building process in the Free World through economic and military aid, with the U.S. model of consumption as the ultimate, phenomenal, goal of development’ (McMichael Citation2005, 275). The worldwide expansion of agricultural research and extension programs during the second food regime was heavily funded by the US government and international agencies. Finally, the third or ‘Globalization Project’ food regime moved away from interlocked Cold War alliances toward international free-trade agreements (FTAs) made in response to the global economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s, and the WTO governance structure, ushering in the current period of neoliberal capitalist expansion (McMichael Citation2009, 2013, Citation2015; Pritchard Citation2009).

While some food regime scholars advocate moving beyond the idea of territorial states as self-contained entities (McMichael Citation2020; Pritchard et al. Citation2016), others attempt to move beyond the ‘relative scalar fixity’ of early analyses by incorporating more detailed empirical cases at smaller scales of analysis (Rioux Citation2018; Wang Citation2018; Jakobsen Citation2021). Some recent literature has turned attention to conceptualizing food regimes in Asian or other regional contexts (Roche Citation2012; McMichael Citation2013, Citation2020; González-Esteban Citation2018; Wang Citation2018). Despite progress in reshaping the food regime concept to address the incorporation of agri-food into a multilateral trading system and its multi-scalar governance structure, scholarship has not fully addressed the regionalization of the postwar food regime. Scholarship has largely overlooked the distinctive, endogenous pathways of the postwar food regime over time, shaped by the ‘implicit rules’ (Friedmann Citation1993, 31), underpinning the transition of food regimes. In particular, there has been little discussion of how the ‘Development Projects’ of the postwar food regime were localized in Asia. For instance, the literature on the postwar food regime has not paid sufficient attention to the reorganization of the Japanese empire’s mercantile apparatus (the zaibatsu groups, such as Mitsui & Co.), and how these groups became the dominant conglomerates in managing USAID during the postwar era and later evolving into today’s sogo-shosha (general trading companies and retailers). Nor have scholars paid enough attention to the agricultural R&D system built by the Japanese empire, and how these agricultural scientific institutes and scientists became essential parts of the ‘green revolution,’ operating through the networks of Cold War US alliances in Asia and evolving into many of today’s global agribusiness.

To this end, addressing the implicit rules of the postwar food regime is particularly important for food regime analysis in conceptualizing the postwar period as the ‘transition’ – if we borrow Chakrabarty’s (Citation2000, 41) concept of ‘transition narrative,’ which highlights the modernization procedure that privileges a Western-centered knowledge system. Chakrabarty suggests that if ‘Europe’ is provincialized, we must condemn the prioritization of the knowledge system embedded in institutional practices for the purpose of (European) dominance. We further note that answering Friedmann’s (Citation2016, 677) recent call to open an inquiry into the ‘simultaneously changing parts of a changing totality’ of food regimes with ‘open historical interpretations’ can help to address the transition from the first food regime to the second and its ‘carryover’ for further development. As such, in this study, we attempt to reveal the implicit rules that governed the postwar food regime for agrarian development in Asia. We discuss the scientific agrarian knowledge regime created for the purpose of dominance and how it constitutes an integral part of the story of imperialism within the Asian regional history of food regimes.

In Hygienic Modernity, Ruth Rogaski (Citation2004) notes that the expansion of the Japanese empire in Asia facilitated the adoption of the modern idea of hygiene, providing a bridge between China and Western countries through which Japanese colonial administrators worked together with Western specialists and the colonies’ native elites to construct material and symbolic power over colonial societies. Similarly, in terms of agriculture, the agency of local actors in Japan’s colonies was crucial for translating and implementing Western agrarian knowledge systems. These local actors included people from both China and Taiwan who had studied modern agriculture in either Japan or a Western country, and who came to play significant roles not only as modern agrarian scientists, but also as active participants in the production of the postwar order of agrarian development (Geng Citation2015).

In this context, Aaron Moore’s concept of the ‘technological imaginary’ provides an important lens. Moore borrowed the term ‘scientific colonialism’ from Goto Shinpei, colonial Taiwan’s head of civilian affairs, to argue that the Japanese colonial regime was articulated through a practical and inventive notion of technology ‘whereby different areas of life were rationally planned and mobilized to exhibit their maximum potential and creativity’ (Moore Citation2013, 7). Regarding the scope of food regime analyses, the technological imaginary resonates with Bernstein’s (Citation2010) argument that capitalism is capable of exploiting multiple forms of labor through different political arrangements, and so colonial states can incorporate a variety of agrarian structures within a given food regime.

In addition, the construction of the technological imaginary for the postwar food regime was synonymous with the simultaneous self-formation of the colonial subject and the lure of the US model of modernity (Patel Citation2013). Agrarian development, alongside other development projects, operated in the form of coordinating individuals who reshaped their societies in the context of war-time discipline. Once the colonial elites acquired positions of power, they laid claim to the ‘truth’ through the systematization and modernization of environmental and agrarian knowledge (Mitchell Citation2002). Although many colonial regimes shared unifying characteristics, the postwar food regime in Asia had specific effects on societies during the Cold War. The circulation of modern scientific agrarian knowledge did not merely flow between two monolithic entities, but rather was a complex process that emerged at specific moments (Patel Citation2013). Hence, examining the moment of emergence highlights patterns of cooperation and coercion, and ‘looks at the sometimes intimate collaborations between multiple “colonizers” and various members of “the colonized”’ (Rogaski Citation2004, 8–9).

Drawing on such approaches helps us to rethink Asia’s variegated geographies and translocalities. It reconfigures how we think about food regimes in Asia, helping us go beyond East – West binaries and the dominant role of the nation-state. In Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization, Chen Kuan-Hsing (Citation2010) argues that Asia has not entirely entered into the postcolonial period because the US-dominated Cold War regime repositioned power relations among Asian countries with the installation of an ‘anticommunism-pro-Americanism structure.’ This Cold War regime retroactively justified Japanese colonialism and imperialism, especially to Japan’s former colonies, because the reflections toward Japan (including Japan itself) were suppressed in service of the US need to secure Japan as the beachhead of its Cold War front in the Asia-Pacific. Nevertheless, neoliberal globalization reconfigured the Cold War regime and opened the door for new forms of decolonization and deimperialization, and the de-escalation of the Cold War in Asia. In this context, Asia’s diverse historical experiences and rich social practices derived from multiple local and regional traditions may be mobilized to provide alternative horizons and perspectives.

As McMichael (Citation2020, 118) notes, it is particularly important for future studies of food regimes to pay greater attention to the synchronic dynamics of food regime ‘conjunctures.’ We argue that, beyond the profound influence of the US in the postwar food regime, the nuances and historical and regional specificities of the agricultural scientists’ life stories and individual agricultural technological imaginaries can ‘scale up’ through the translation and circulation of agrarian knowledge in the transition of food regimes in Asia.

The Japanese empire-dominated first food regime in Asia

In the late nineteenth century, modern agricultural knowledge from Western countries, especially the United States, was introduced into Japan and China, mediated by missionaries, educational networks and international agencies (Duke Citation2009; Love and Reisner Citation[1964] 2012). Japan adopted and adapted American knowledge and practices and transmitted them to its colonies; among them, Taiwan then played a prominent role in the further development of the empire’s agriculture. But Japan also directly influenced China’s agricultural modernization and development prior to the war, during the late Qing and early Republican period (1912–1920). Chinese agricultural experts and scientists trained in American but also Japanese universities, and then returned and applied Japanese approaches and practices – adapted from American agrarian science – to Chinese farms (Dong Citation1997; Geng Citation2015; Perkins Citation1997; Stross Citation1986). Meanwhile, as the Japanese empire stretched its physical boundaries through military conquest, some first-generation Japanese-Americans with agricultural expertise acquired there returned to Asia to carry out their own colonial ventures, contributing to Japan’s territorial expansion (Azuma Citation2019).

From the late nineteenth century until 1945, Taiwan and many parts of Asia were increasingly enmeshed in an emerging food regime centered on the Japanese empire as it strove to mold itself as metropole in the classic ‘old international division of labor’ characteristic of Western colonial empires. Consolidation of this food regime involved re-orienting the colonies toward an imperial division of labor with Japan receiving imports of rice and sugar from Taiwan, rice and soy from Korea, and soy, cotton, and coal from Manchuria; and conversely, Japan exporting manufactured goods, especially textiles, to its colonies (Hiraga and Hisano Citation2017, 18). A key feature of this regime was the production of agricultural knowledge by Japanese actors, and the deployment and circulation of knowledge, trained personnel, and seeds throughout the empire, mimicking Western imperial powers. But the story is more complex: Japanese practices and institutions of knowledge production were heavily influenced by America in multiple ways, and knowledge produced in Japan’s Taiwan colony was circulated to other parts of the Empire.

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the government began efforts to modernize agriculture in the Japanese homeland, and later extended those efforts to its occupation and settler colonies (Lynn Citation2005). In addition to the land reforms of the 1870–1880s and conversion to tax payments in cash (Hirano Citation2015, 198), the Meiji government sought advice from Western experts, which led it to promote modern and capital-intensive farming methods, such as increased use of animal power, and replacing traditional self-sufficient soil management techniques with purchased fertilizer. Initially this was domestic fishmeal, but supply was limited, and soymeal imported from Manchuria became increasingly dominant in the 1890s (Hiraga and Hisano Citation2017, 9). The early Meiji also adopted American modes of agricultural knowledge production and circulation, including agricultural schools and extension agencies. To give just one example, Horace Capron, a former US Commissioner of Agriculture under President Ulysses Grant, was hired by the Meiji from 1871 to 1875 to advise on the settler colonization of Hokkaido. He established demonstration and experimental farms in Tokyo and then Hokkaido, and his recommendations led to the founding of Sapporo Agricultural CollegeFootnote4 in 1876 by William S. Clark, a professor of chemistry and botany and a leader in American agricultural education (Hirano Citation2015, 202; Gowen et al. Citation2016).

These institutions and practices became part of the colonial machinery, and Japan transferred them to Taiwan as soon as it gained sovereign control in 1895 after the first Sino-Japanese War. The Taiwan Colonial Governor-General’s Office (TCGO) brought experts from Japan, many of them graduates from the abovementioned agricultural college in Sapporo, to establish and staff modern agricultural institutions. Two of note were Iso Eikichi (1886–1972), who helped found the Agricultural School of Taihoku Imperial University in 1925 (now National Taiwan University), and Hikoichi-I Oka (1916–1996), who would become one of the founders of the Taiwan Governor’s Office High School on Agriculture and Forestry (now National Chung Hsing University) in 1944 (Kitamura et al. Citation2016).Footnote5 The TCGO established its first agricultural extension station as early as 1896 (Fujihara Citation2018, 141), followed later by a chain of experimental and extension stations (Wang Citation2018).Footnote6 It implemented major irrigation works and consolidated a network of Farmers Associations (Looney Citation2020, 57).

Taiwan was expected to become an important source of rice for the Japanese home islands, and the TCGO directed the Japanese experts in Taiwan to improve rice yields. Early efforts to transfer japonica varieties developed in Japan to the relatively tropical Taiwan were not successful, so the TCGO prioritized selecting and improving the highest-yielding local indica varieties. An early success was the DGWG indica variety developed in the 1910s. It was high yielding but not welcomed by Japanese consumers, so after the 1918 rice riots the experts in Taiwan were directed to refocus on developing japonica varieties.Footnote7 Iso Eikichi, who played a role in developing DGWG at Taihoku Imperial University, was sent by the TCGO in 1918 and 1928 to study under Professor Harry H. Love at Cornell University (Iso Citation1954). There he was exposed to photoperiodism, a new set of theories and techniques. He returned to Taiwan and by 1926–1928 applied these to lead the development of a japonica variety – Taichung 65 or horai – that produced high yields in Taiwan and was welcomed by Japanese consumers (Fujihara Citation2018).

After colonizing Hokkaido and Taiwan, Japan continued to expand its empire and extend modern agricultural practices into new colonies in Korea and Manchuria. Victory against Russia in 1905 conferred control of China’s Liaodong Peninsula and Korea. Full annexation of Korea followed in 1910, but as early as 1906 the Japanese Governor-General in Korea established an Agricultural Experiment Station in Suwon, near Seoul. More substations followed, some Koreans were allowed to study agronomy in Japanese universities, and by the late 1930s new rice varieties were being developed in Korea. But dynamics differed from Taiwan in one important regard: japonica varieties developed in Japan grew well in Korea, and by colonial fiat had mostly replaced indigenous strains by the 1920s (Kim Citation2018, 191–192). Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931 but did not establish modern agricultural institutions immediately; however, a series of local agricultural academies had sprung up in Japan in the 1910s and 1920s, with their curriculas eventually melding nationalism and modern agricultural techniques, and in the 1930s these took on the role of training potential settlers to Manchuria (Young Citation1998, 332, 360). Similar in climate to Korea and parts of Japan, modern japonica rice strains developed in Japan transferred well to cultivation in Manchuria (Fujihara Citation2018, 141), and agricultural experiments may not have been as immediately necessary.

Japan began to invade China proper in 1937, occupying Beijing, Shanghai, and Nanjing. As it continued its expansion into the less familiar climates of southern China it looked to Taiwan, seeking to take advantage of the useful colonial and agricultural knowledge it had developed in its only tropical colony (Chang Citation2007; TCGO Citation1943). The TCGO was eager to oblige, hoping to bolster its importance within the Empire in the face of fierce enmity and competition between itself (founded by the Imperial Japanese Navy) and the South Manchuria Railway (SMR), founded by the Japanese Guandong Army (Azuma Citation2019; Hotta Citation2014). Even before Japan’s invasion of China, TCGO Governor-General Nakagawa Kenzō had initiated official surveys of ‘tropics’ to prepare for Japan’s expansion towards Southeast Asia (TCGO Citation1935), and then founded the Taiwan Development CO., LTD in 1936–1937 to promote Japanese mercantilism. The TCGO launched policies to increase agro-industrial production in wartime Taiwan and simultaneously drew on this experience to design colonial policies in anticipation of the need to reconstruct, govern, and industrialize Japan’s newly occupied territories in the more tropical southern China and Southeast Asia (Kao Citation2005). During this period, TCGO ceaselessly reiterated that the knowledge of tropical agriculture it had developed in Taiwan would be key to the Empire’s expansion in Asia. One example of implementation occurred in Hainan, where the Japanese started to implement a system based on the horai rice and sugar economy the empire had developed in colonial Taiwan (Chung Citation2003).

In 1941 Japan began the conquest and incorporation of Southeast Asia with the purpose of securing self-sufficiency in key resources, mainly petroleum (Hotta Citation2014). The Japanese military expected each territory to be food self-sufficient and also feed the occupying forces: even with Taiwan and Korea producing rice for Japan, food supplies were tight, shipping was fraught with risks, and such resources were needed for the war. However, many areas of Southeast Asia were net importers of food, having become specialized in export crops such as pepper, sugar, coffee, tobacco and rubber for European markets; only Vietnam, Myanmar, and Thailand were net exporters (Chang Citation2007). The tropical varieties of rice were not amenable to Japanese consumers anyway, so the Japanese military mandated some trade between territories within the region. It also undertook efforts to increase local rice production, bringing seeds and experts and beginning training and extension. In the Philippines, the Japanese Military Administration planted experimental farms with horai rice, and after declaring success, ordered some areas to plant only horai (Jose Citation1998, 73–75). In Malaysia, the Japanese dispatched ‘soldier-farmers’ to introduce and promote cultivation of horai (Kratoska Citation1998, 107). In Sarawak, agricultural stations and training schools were established (Cramb Citation1998, 147). None of these efforts were very successful. It can be inferred that localizing even the more tropical indica and horai rices developed in Taiwan would have required sustained experimentation and adaptation (Kurasawa Citation1998, 33), but the Pacific War simply ended too quickly in September of 1945.

Japan tried to increase food production in its new colonies, but also restructured the patterns of agricultural production in other ways. Before the war, northern China, Manchuria and the colony in Korea had served as Japan’s main production bases for soybeans, and northern China in particular as an important source of cotton (Hiraga and Hisano Citation2017). During the 1920s, British India and the United States together produced roughly 85% of Japan’s cotton imports (Ellinger and Ellinger Citation1930), but these sources were cut off with the beginning of the Pacific War. Because cotton was such a crucial input for munitions, clothing, and Japan’s competitive textile exports, Japan attempted to increase cotton cultivation in northern China but also in other colonies such as Taiwan, Hainan, and Southeast Asian territories in Java, the Philippines, Sarawak, and Vietnam in order to ensure cotton self-sufficiency within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (Moore Citation2013; Nagano Citation1998; Sato Citation1998, 179; Jose Citation1998, 74–75; Cramb Citation1998; Nguyen Citation1998, 210; Chung Citation2003).

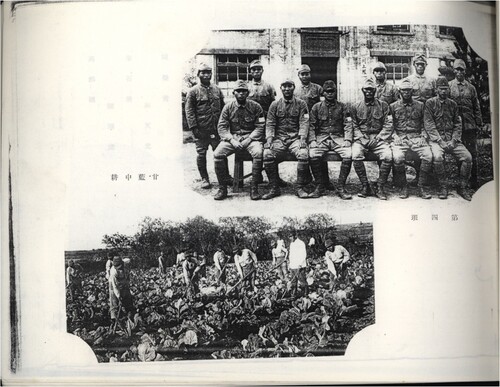

Finally, the empire also deployed trained personnel as part of its efforts to restructure agriculture in southern China and Southeast Asia to support military expansion and occupation, and to integrate and consolidate the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The agrarian education system was originally available only to Japanese citizens in colonial Taiwan, including Taiwanese with Japanese citizenship (Ka Citation1995; Kitamura, Hiura, and Yamamoto Citation2016), but it was gradually opened to Taiwanese students, and modern agriculture became central to the colonial education system during wartime (Sugai Citation1943). Modern agricultural education and training became part of the social reform that students in Taiwan experienced during the Kominka Movement, the radical Japanization campaign that started in 1937 and lasted throughout the war (Ching Citation2001). Starting in 1938, in order to increase the supply of food for the empire from the new territories in southern China and Southeast Asia, the TCGO repurposed its agricultural research institutes and experimental stations, creating regional and local centers to train Taiwanese farmers and villagers as agricultural experts. In the meantime, the Japanese Civilization Association (Citation1943) and the Farmers’ Associations in Taiwan also assumed responsibility for the basic training of agrarian settlers (Chang Citation2007). The TCGO drew on these to dispatch agrarian experts and settlers to implement modern agriculture and produce military crops in other colonies. For example, in April 1938, the Japanese army formally requested that the TCGO to dispatch agricultural experts and about 1,000 farmers to plant vegetables near Shanghai to feed the army. The group of experts and farmers who were subsequently sent were called the ‘Taiwanese Agricultural Volunteer Team’ (see ).Footnote8 There were also Taiwanese among the ‘Japanese’ experts sent to Southeast Asia (Chung Citation2020; Wang Citation2018).

Figure 1. The Taiwanese Agricultural Volunteer Team in Shanghai. Source: The Taiwanese Agricultural Volunteer Team Photo Album (1940). (This is an unpublished and unclassified archive collected by the authors from Kaohsiung Museum of History in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan.)

After the war, the Japanese wartime regime was interwoven with the US Cold War system through US foreign aid, rural development projects, and ‘green revolutions.’ At the same time, agriculture in China was influenced by the emergence of the socialist Chinese state and its experiments in socialist agricultural development, which resulted in the so-called red revolutions (Schmalzer Citation2016). Although the world structure changed significantly in the transition towards the postwar period, the circulation of modern agricultural knowledge, carried out (and re-located) through the agricultural scientists and their institutions, has remained a crucial part of the emerging postwar food regime.

The postwar food regime in Asia

The food systems that emerged in postwar East Asia largely followed the same ‘replication and integration’ pattern as in Western countries during the Second Food Regime, emphasizing the tight articulation within Keynesian container states of agricultural self-sufficiency, industrial development, and consumption. The Cold War and US containment policy were key factors in the development of Japan and the New Industrial Countries (NICs). But the domination of Japan and its former colonies under the US Cold War umbrella resulted in some key regional differences. Postwar reconstruction was accompanied by vast amounts of food aid but also sweeping, American-designed land reforms. US occupation forces allowed Japanese trade companies (sogo-shosha) to re-establish their prewar and wartime networks, and Taiwan played a prominent role; in the 1950s and 1960s it grew to be one of the world’s leading exporters of a range of agricultural goods, which went mostly to Japan (Cumings Citation1984; Hamilton and Kao Citation2018; McMichael Citation2000; National Development Council Citation1994; Schonberger Citation1973).Footnote9 As part of its Cold War efforts to prevent communist revolutions, the US amplified its role in modern agricultural research and development in Asia (Cullather Citation2010), and Taiwan became an important partner in these efforts. The case study presented here of the Sino-American JCRR and one of its leading figures, Shen Zonghan, helps foreground the central role played by international agricultural research and R&D programs in the postwar food regimes. A close examination of the creation of the AVRDC illuminates the implicit rules of the regional food regime, in which agency did not belong to the US alone; rather, Taiwan leveraged the geopolitics of food security to position itself internationally. The expansion of US hegemony was not limited to territorial expansion through either settler colonialism or geopolitical strategies (Arrighi Citation1994); the postwar food regime that mobilized agricultural R&D, including scientific knowledge, scientists, and modern agriculture, was a constituent part of US hegemony, mixed with both territorial strategies and geo-economic interests.

Shen Zonghan and the JCRR

Shen Zonghan (1895–1980) was the primary designer of the JCRR and later became its chair from 1964 until his retirement in 1974. He received a master’s degree from the Georgia State College of Agriculture (now University of Georgia) in 1924 and then entered the agricultural college at Cornell University. There he was trained by Harry Love in breeding, genetics, and plant pathology with a focus on rice and weed cropping. Love, who’s training led Iso Eikichi to invent horai rice, had close connections with China through missionary agricultural education. One of Love’s students, John Reisner, was a founder and the first director of the College of Agriculture and Forestry at the missionary University of Nanking. Together, Love and Reisner started the Cornell-Nanking Program in 1925, a cooperative project that lasted twenty years and combined missionary work with spreading modern agriculture. Thus, the first international technical cooperation in agriculture was designed to improve Chinese agriculture (Myers 1962,Footnote10 quoted in Love and Reisner Citation[1964] 2012). According to the program’s mission statement, each year a Cornell representative would visit China and conduct research, training, and extension at the University of Nanking with the support of a start-up fund from the Rockefeller Foundation and churches in the US. Three Cornell professors were deeply involved in the program, with Harry Love in residence in 1925 and 1929, Clyde Myers in 1926 and 1931, and Roy Wiggans in 1927 and 1930 (Stross Citation1986; Love and Reisner Citation[1964] 2012). Shen graduated from Cornell in 1927, and with Love’s support he joined the agricultural program at the University of Nanking. During the ten years he taught there, he was a pioneer of Chinese agricultural modernization and became ‘China’s foremost plant-breeding expert’ (Ladejinsky Citation1977, 137). Shen recalled his participation in the Cornell-Nanking Program:

I should also like to express my gratitude and pleasure in having been privileged to take part in the Program. The International Education Board granted a research fellowship to me in 1926–1927 on the recommendation of Professor H. H. Love and C. H. Myers. While on the faculty of the University of Nanking in 1927–1937, I had the rare opportunity to acquire valuable experience from the Cornell University professors, Drs. H. H. Love, C.H. Myers, and R.G. Wiggans. (Love and Reisner Citation[1964] 2012, 57)Footnote11

With confidence in the international cooperation built up from my early association with the triangular cooperative program, I have enjoyed working, since 1948, in my present position with the China-United States Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction in China. (Love and Reisner Citation[1964] 2012, 57)Footnote13

Dear Dr. Shen … There is a great deal of value in Dr. Iso’s compilation, and as you will recall, sometime ago, Dr. Fendleton and I wrote JCRR urging that efforts be made to publish your book on Chinese agriculture and Iso’s manuscript covering the valuable results from his many rice experiments … Footnote14

Following that, Shen responded to Love:

My dear Professor … Referring to my letter under the date of April 30, 1953, I wish to inform you that Mr. Iso is leaving for the United States today under the support of the Chinese National Government for the final editing and publishing of his manuscript … Footnote15

As a trustee of the International Rice Research Institute, Manila, I met Mr. John D. Rockefeller, III at the opening ceremonies of the Institute on February 7, 1962. I expressed my gratitude to him for my research fellowship from his father’s foundation, the International Education Board, and commented on this triangular cooperative program as the earliest and also the best example of technical assistance by American institutions to foreign countries. (Love and Reisner Citation[1964] 2012, 57)Footnote18

Under US guidance in the 1950s, Taiwan’s agricultural institutions started allocating more resources to the research and development of high-value-added crops such as fruits and vegetables (Wang Citation2018). This would contribute to Taiwan’s growing food exports to Japan, but to Shen and the JCRR this was not just about improving agricultural productivity to support economic development, nor did they see it simply as a way to fight against communism. The JCRR’s partner and sponsor, USAID,Footnote19 molded international food security discourses in service of Cold War strategies, drawing upon the expertise of US universities, nongovernmental and private voluntary organizations, multilateral development partners, and overseas universities (Shah Citation2016). Green revolutions of basic grains and staples received more attention in the Cold War project of developing global food security, but in the 1950s USAID, the JCRR, and many partner institutions started to focus on increasing vegetable production as well (GAO Citation1978). Shen would again play a key role in these efforts. Close examination of his role and actions in founding the AVRDC, in the context of Taiwan’s geopolitical circumstances, reveals that his motivations exceeded US Cold War umbrella interests in containing communism. Ostensibly about bolstering Third World nutrition and wrapped in security concerns, the focus on vegetables would later play a significant role in the emergence of New Agricultural Countries (NACs) and transitions beyond the Second Food Regime (McMichael Citation2000; Rosset et al. Citation1999).

Seeding ‘the world’ for food security in the postwar period: CGIAR-IARCs and the AVRDC in the postwar food regime

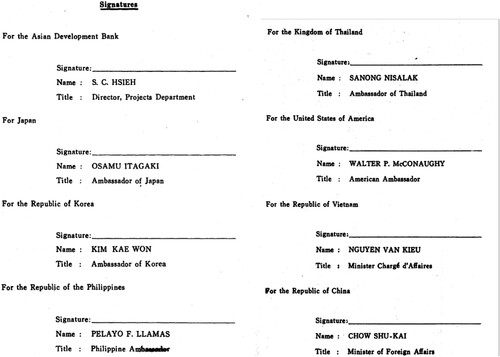

One of Shen’s major contributions was to deepen the ROC’s international agricultural cooperation. In this regard, the most important project he worked on was founding the AVRDC (Shen Citation1975), which he framed in Cold War terms as ‘Free China … making its contribution to world agriculture’ (Shen [1964] 2012, 57, quoted in Love and Reisner Citation[1964] 2012). Shen started working on the AVRDC right after he was appointed chair of the JCRR in 1964. The idea had been initiated that year by USAID to address the insufficient production and consumption of fruits and vegetables worldwide (General Accounting Office Citation1978). But USAID had difficulty securing funding for the new research institute, and it originally intended to locate it in Thailand, not Taiwan. Shen worked tirelessly and was instrumental in convincing USAID and members of the US government, such as Congressman Otto E. Passman, to provide funding and change the location to Taiwan (Shen Citation1975, 88–108). The AVDRC was founded in 1971 and became operational in 1974, with the official purpose of ‘alleviating poverty and malnutrition in the developing world through the increased production and consumption of nutritious and health-promoting vegetables’ (AVRDC Citation1976). Taiwan provided 116 hectares of land, facilities to house the center, and more than one-third of the budget, while USAID-JCRR provided 40 percent of the budget; the Asian Development Bank, 10 percent; the Republic of Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines, 5 percent each; Vietnam, a symbolic contribution; and Japan, technical support and a one-time US$40,000 donation. Currently, the AVRDC is supported by contributions from governments worldwideFootnote20 and international developmental agencies,Footnote21 but Taiwan has been the single largest donor at 40 percent of the average annual budget since 1990 (see ).Footnote22

Table 1. Taiwan’s (ROC) contribution to the budget of the AVRDC.

The AVRDC was formed independent of other mainstream global food security institutions of the Cold War. For example, it was not part of the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), which was co-organized in 1971 by eighteen governments and international organizations. Co-organizers including the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the United Nations Development Programme, and the World Bank provided financial assistance and technical support, and participated in decision-making. In order to extend its early achievements, additional International Agricultural Research Centers (IARCs) were established in the following years to support research to improve important staple crops (such as beans, root vegetables, and cereals) as well as livestock and other agricultural, forestry, and aquatic sectors. Several research centers that did not originally belong to CGIAR have been moved under its umbrella. Currently there are 16 IARCs, and many additional research centers that share the same purpose but are not formally under the CGIAR umbrella with ‘non-associated centers,’ one of which is the AVRDC (Greenland Citation1997).Footnote23

In 2017, CGIAR’s budget totaled US$849 million, with industrial countries accounting for two-thirds of its funding. Most of the funding sources are supported by diplomatic or foreign aid programs in these countries. Funds granted by sponsoring members are based on the IARCs or projects they choose to support, and each IARC is responsible for reporting expenditures to each sponsoring member.Footnote24 In other words, the CGIAR can be seen as an officially recognized institution under the US Cold War security umbrella, an identity that could not be directly afforded to the Taiwan-centered AVRDC.

The CGIAR Technical Advisory Committee recommendation to include the AVRDC among the IARC system was denied for ‘political reasons’ (Greenland Citation1997, 471), partially due to the US rapprochement with the PRC. In the 1970s, the US was gradually developing formal relationships with the People’s Republic China (PRC) and officially ended diplomatic relations with Taiwan (ROC) in 1979. But the CGIAR and AVRDC had close informal ties from the beginning. The founding director of the AVRDC, Robert F. Chandler Jr. (1972–1975) and his successor, James C. Moomaw (1975–1979), were both agricultural scientists from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines (Fletcher Citation1993), one of the original four of the CGIAR’s IARCs, and arguably the most important and famous. The AVRDC’s desire to gain official entry into these international networks can be seen in its significant, but unsuccessful, efforts to join the Global Forum on Agricultural Research (GFAR).Footnote25 The GFAR was established in 1996 by international and regional organizations, government agricultural institutions, scientific societies, nongovernmental organizations, and business groups to promote dialogue and cooperation among all agencies concerned with international agriculture and food security. These founding entities and GFAR itself have actively participated in academic exchanges and technical projects with CGIAR and with AVRDC. Thus, AVRDC never had a chance to formally participate in the CGIAR-IARC, but the GFAR is one of many channels through which a network of informal ties links AVRDC in close communication and cooperation with international society.Footnote26

Among the AVRDC’s many initiatives, two were integral to the postwar food regime and are discussed here in greater detail: the distribution of vegetable seeds and the training of agricultural experts. More than 50% of the AVRDC’s budget has been dedicated to maintaining a large collection of public domain germplasm, and breeding new varieties of vegetables. In 1974, it founded the Genebank seed database to collect vegetable species; this has since become the largest vegetable seed database in the world. In the same year, it started to distribute seed samples of germplasm accessions and advanced breeding lines to other US Cold War allies. Between 1974 and 2019, the AVRDC distributed 406,817 samples of different varieties of vegetable seeds to fulfil 15,421 requests made by private and public actors and agencies. After the end of the Cold War, the three major countries making requests were Thailand (12,114 samples), the Philippines (2,493 samples), and the US (1,163 samples).Footnote27 Another important mission of the AVRDC has been its role as a training center. Between 1974 and 2019, the AVRDC trained 1,973 agricultural scientists and experts. The majority of these trainees were from US Cold War allies, including the Philippines (202), Thailand (110), Indonesia (82), the Republic of Korea (100), India (82), and Malaysia (71).Footnote28

The AVRDC’s extraordinary contributions to international food security, with its advanced research and training programs, and vegetable crop seed development and distribution, has fulfilled its mission set by its founder Shen Zonghan: to expand the international political space of Taiwan (ROC) through its capability in scientific agricultural research.Footnote29 From the beginning, the role of the AVRDC has not been limited to agricultural R&D. None of the representatives of the founders of the AVRDC had backgrounds related to agriculture. Rather, they were ambassadors or ministers of foreign affairs representing their countries (AVRDC Citation1976, see ). The founding of the AVRDC was part of the international politics of food security. Considering the international political environment that Taiwan (ROC) was facing in the 1970s and 1980s, the AVRDC was more like a piece of driftwood that Taiwan had to grasp onto to survive, as its position in world politics was deteriorating rapidly. Since then, the AVRDC has become one of the few international organizations that Taiwan has remained involved in, despite losing its de jure and de facto international political status.Footnote30

Conclusion

When the Japanese empire occupied southern China and Southeast Asia and attempted to realign existing agrarian regimes to its ends, it drew heavily on its experience with tropical agriculture in Taiwan. The TCGO was key to these endeavors, actively participating in the reconstruction of the occupied territories with the goal of increasing food production. Concurrently, the scientific practices of modern agrarian development emerged in Asia, facilitated by intellectual contact driven by the Japanese empire. In the postwar era, the US and the KMT government preserved the Japanese colonial agrarian scientific institutions and incorporated tropical agricultural researchers. Moreover, the postcolonial connection of agricultural trade between Taiwan and Japan remained a constituent part of the postwar food regime, which contributed to maintaining the food security of the US-centered Cold War order.

Although Taiwan was the model state for ‘green revolutions’ due to its extraordinary performance in increasing agricultural production in the postwar era (Cumings Citation1984), its agrarian development must be interpreted within the context of both its unique local conditions and the translocal agrarian networks influenced by the US, the Japanese colonial legacy, the KMT government, and agricultural experts who immigrated from China. Recent studies generally agree that the emerging multipolarity of food regimes in the neoliberal era is an expression of the neoliberal architecture of the WTO. Yet McMichael points out that ‘each food regime is formed temporally: juxtaposing residual, dominant, and emergent relations’ (McMichael Citation2020, 118). Accordingly, through the case of the JCRR, the AVRDC and the proactive role played by Dr. Shen Zonghan in building both organizations and beyond, we have demonstrated that Taiwan (ROC) and the US began redefining the meaning of food security and expanded their missions to cover broad definitions of nutrition and food security, including the development of R&D and production of vegetable crops, alongside other crops in the 1970s. This trajectory paved the way for the neoliberal trend of agricultural R&D and the commodification of high-value crops in the contemporary food regimes. In effect, to understand the ‘carryover’ from the second food regime, we must consider the Cold War legacies and postcolonial contexts that have structured the institutions or practices of food regimes.

Finally, this study is very much in line with McMichael’s (Citation2020) view of China’s BRIC initiatives in the context of ‘agro-security mercantilism’ and how they contribute to the multipolar patterning of contemporary food regimes. However, there is a risk that food regime scholarship might overemphasize China and portray it as the single pole of the food regime, while ignoring other parts of Asia that still maintain the food regime developed in previous eras. As Chen (Citation2010) reminds us in Asia as Method, the economic miracle of Asia during the Cold War unfolded in the shadows of the ‘anticommunism-pro-Americanism structure.’ Without shedding light on the power structures underlying ‘Asian triumphalism,’ the rise of Asia (or China) could be seen as a mimic of the western empire. Additionally, we appreciate the perspective of ‘the power of small stories’ in analyzing the food system by recognizing the nuance and historical specificity of colonial farming without undermining our capacity to tell bigger stories of capitalism or food regimes (Campbell Citation2020). The complexity of Shen Zonghan’s life story in forming the postwar food regime – being a converted Christian and missionary, Chinese farmer and US-trained agronomist, diplomat and public official for the Taiwanese government – demonstrates how an individual’s agricultural technological imaginary can ‘scale up’ through the translation of agrarian knowledge for development, and further explains the transition narrative of food regimes in their colonial and postcolonial contexts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and feedback, which have greatly improved the quality of this research. Special thanks go to Bryna Goodman, Serena Chou, Ryan Holroyd, and Shuxi Wu, whose invaluable advice has been essential to the development of this project. We are also deeply indebted to the librarians at various institutions, including the Kaohsiung Museum of History, the Library of Institute of Modern History (Academia Sinica), Archives of the Institute of Taiwan History (Academia Sinica), AVRDC Library, USAID Library, and Cornell University Library, for their generous assistance in collecting archival sources, which have been instrumental in our research. We are grateful to the researchers and staff at AVRDC for their unwavering support, whether it be through interviews or by providing relevant data. Their contributions have been invaluable to the success of this project. Finally, we extend our heartfelt thanks to Yushuan Chen, Wayne Lo, Julia Xua, and Angus Yen, for their invaluable assistance in collecting and organizing the data and archives applied in this paper. Their hard work and dedication have been critical to the success of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kuan-Chi Wang

Kuan-Chi Wang is an associate research fellow at Academia Sinica. His current theoretical interests address critical geopolitics, environmental governance and politics, new economic geography, and geospatial modeling with a particular focus on Asian foodways. His works appear in academic journals such as The Journal of Peasant Studies, Area, Geography Compass, Environment and Planning E, Geographical Review, among others.

Daniel Buck

Daniel Buck is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and the Director of the Asian Studies Program at the University of Oregon. His research interests include political economy, political ecology, development, and food and agrarian studies.

Notes

1 In recent years, one of the major developments in the field of food regime analysis has been the introduction of the concept of ‘scale’ (Jakobsen Citation2021). To avoid repeating too much of what has been achieved, we draw on the new food regime geographies perspective with an emphasis on the ‘multipolarity’ or ‘polycentricity’ of food regimes. We emphasize ‘regionalization’ processes that make scale in Asia, with particular attention to how certain nodes or places of power in the postwar food regime were increasingly dispersed across new spatialities in the global political economy, such as Taiwan (ROC) and parts of Southeast Asia. In this paper, our goal is to explain how regional food regime analysis can benefit from such a ‘regionalization’ perspective, drawing on postcolonial approaches to understanding the roles of translocal networks and knowledge translation in agricultural innovation, such as R&D.

2 For instance, because of the influence of Cold War geopolitics, Taiwan’s experience with agrarian change demonstrates a unique pattern of mobilizing rural society through the intervention of the JCRR and the US in order to develop Taiwan’s agriculture through the Farmers’ Associations (FAs) (Looney Citation2020).

3 We collected data from archives and libraries including: US Agency for International Development (USAID) Archives; Kroch Library at Cornell University; Institute of Modern History Archives (Academia Sinica, Taipei); Asia Vegetable Center Library; and Academia Historia Archives.

4 Later renamed Tohoku Imperial University, then renamed Imperial Hokkaido University in 1918, and simply Hokkaido University after the war.

5 From unpublished documents archived at the NTU Eikichi Memorial House. The influence of these agricultural experts trained by the university in Sapporo was felt at multiple levels of the school education in colonial Taiwan (Kitamura, Hiura, and Yamamoto Citation2016).

6 Originally there were only nine sub-regional agricultural experimental stations and laboratories, but the number of research institutions increased significantly during the Pacific War (Wang Citation2018).

7 ‘Rice Riots 1918’ is a research topic that has attracted a fair amount of attention in academia. In general, they were due to the convergence of social, economic, and political crisis, caused by the inflation and the skyrocketing price of rice in Japan which happened right after the end of World War I, and involved series of mass demonstrations and armed clashes that spread across Japan for eight weeks from July to September 1918. The riots led to the resignation of Prime Minister Terachi and his cabinet. To learn more about the historical background of the riots, refer Steven J. Ericson’s article (Ericson Citation2015): Japonica, Indica: Rice and Foreign Trade in Meiji Japan.

8 This is an unpublished and unclassified archive collected by the authors from Kaohsiung Museum of History in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan.

9 Over 50% of Taiwan’s exports were sent to Japan, including rice, sugar, canned asparagus, canned pineapple, and fresh fruits and vegetables (Taiwan Statistical Data Book Citation1994, 194). Starting in the late 1960s, Taiwan’s agricultural exports also began to supply the US Army in Vietnam until the end of the Vietnam War (Hamilton and Kao Citation2018).

10 The document is a lecture quoted in Love and Reisner Citation[1964] 2012.

11 See also letter from Shen to Love on Oct 12, 1962. Source: Harry H. Love papers, 1907–1964. Collection Number: 21-28-890. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

12 In terms of qualifications, one of the main reasons, besides being a well-trained agronomist, was that Shen was a devout Christian. Shen’s older brother converted to Christianity in high school around the age of 15, and Shen followed in his footsteps, becoming a Christian around the same time (Shen Citation1975).

13 See notes 10 and 11.

14 See letter from Love to Shen on Apr 9, 1953. Source: Harry H. Love papers, 1907-1964. Collection Number: 21-28-890. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

15 See letter from Shen to Love on May 5, 1953. Source: Harry H. Love papers, 1907-1964. Collection Number: 21-28-890. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

16 We have used the New Taiwan Dollar as the monetary unit based on the original information from the archive.

17 Letter from Samuel P. Hayes to Hubert G. Schenck. 1953. JCRR Archive in the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, Taipei (36-16-002-001, 201).

18 See note 10.

19 The USAID was formally created by the US in 1961, but to the ROC (and KMT), based on the Mutual Security Act 1951, the ROC and the US co-founded the USAID Council to arrange foreign aid directly from the US to the ROC starting in 1951. We use the term USAID in this context.

20 These countries include Australia, France, Germany, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the Philippines, and the United States.

21 Special support comes from the ADB, International Development Research Centre, Swiss Development Corporation, Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation, and World Bank.

22 See for the statistics of the Taiwan government’s budget in supporting the AVRDC.

23 There are five ‘non-associated centers’ of CGAIR that only received limited support from CGIAR, including AVRDC, the International Board for Soil Research and Management (IBSRAM) in Thailand, International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) in Kenya, International Fertilizer Development Centre (IFDC) in USA, and International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) in Nepal (Greenland Citation1997).

25 This information is based on my interviews with the (former) Deputy Director General for Administration and Service of AVRDC, Yin-Fu Change, and a senior researcher, George Kuo, who was in charge of the international cooperation of the AVRDC in 2001–17. The interviews were conducted by one of the authors at the AVRDC, Tainan, Taiwan, August 22, 2019.

26 Though AVRDC only received limited funding from GCIAR, according to the annual budget reports, the support has lasted for decades, and as we have demonstrated, the goal of AVRDC and its practices are somewhat aligned with the mission of GCIAR.

27 Our data sources are annual reports and the unclassified and unpublished data of the AVRDC. We have provided the metadata to the journal (note that the data documented in 1974–1994 were not allowed to be disclosed by the AVRDC and so we only provide the data from 1995 to 2019).

28 Our data sources are annual reports and the unclassified and unpublished data of the AVRDC. This part of the information is not allowed to be disclosed by AVRDC, so we have decided not to submit it with our paper.

29 See note 25.

30 This is not to suggest that the AVRDC has had no influence on the evolution of the global food system. Within a larger context, the AVRDC was actually the pioneer of developing the R&D of high-value crops. For instance, based on the archives of the official letters we were allowed to read during our interviews with the AVRDC, we find that at the annual meeting of the CGIAR-IARCs in 1985, the CGIAR-IARCs proposed including vegetable R&D, and, at its annual conference in 1987, the CGIAR-IARCs formally proposed the establishment of an international vegetable research service center. The World Bank also started to support this sort of research in the 1990s, including allocating US$250,000 to the AVRDC in 1989, and later increasing its annual sponsorship to US$550,000 in 1993.

References

- Arrighi, Giovanni. 1994. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times. New York: Verso Press.

- Arrighi, Giovanni. 2007. Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Verso Press.

- AVRDC. 1976. Memorandum of Understanding and the Charter. Tainan: Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center Press.

- Azuma, Eiichiro. 2019. In Search of Our Frontier: Japanese America and Settler Colonialism in the Construction of Japan’s Borderless Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bernstein, Henry. 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing and Kumarian Press.

- Bremseth, Cameron. 1959. An Evaluation of the Participant Program in Taiwan. Washington, DC: MSM/C, the JCRR, and the USAID.

- Campbell, Hugh. 2020. Farming Inside Invisible Worlds: Modernist Agriculture and Its Consequences. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Chang, Ching-I. 2007. “「Chutou zhanshi」zhinanjin— rizhi houqi taiwan nongye rencai zhi shuchu.” [Hoe’s Warriors to South: The Export of Taiwan Agriculturists in the Later Japanese Period.] Journal of Kao Yuan University 13 (7): 377–400. (in Chinese).

- Chang, Han-Yu, and Ramon H. Myers. 1963. “Japanese Colonial Development Policy in Taiwan, 1895–1906: A Case of Bureaucratic Entrepreneurship.” The Journal of Asian Studies 22 (4): 433–449. doi:10.2307/2049857

- Chen, Kuan-Hsing. 2010. Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Ching, Leo T. S. 2001. Becoming ‘Japanese’: Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Chung, Shu-Min. 2003. “Zhimin yu zaizhimin—rishi shiqi taiwan yu hainandao guanxi zhi yanjiu.” [Colonization and Re-Colonization: Study on Relationship Between Taiwan and Hainan in the Japanese Colonial Period.] Historical Inquiry 31: 169–221. (In Chinese).

- Chung, Shu-Min. 2020. Rìzhì shíqí zài nányang de Táiwānrén [Taiwanese in Southeast Asia in the Japanese Colonial Period]. The Institute of Taiwan History Press, Academia Sinica. (In Chinese).

- Cramb, Robert. 1998. “Agriculture and Food Supplies in Sarawak during the Japanese Occupation.” In Food Supplies and the JapaneseOccupation in South-East Asia, edited by Paul H. Kratoska, 135–166. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-26937-2_6

- Cullather, Nick. 2010. Hungry World: America’s Cold War Battle Against Poverty in Asia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Cumings, Bruce. 1984. “The Origins and Development of the Northeast Asian Political Economy: Industrial Sectors, Product Cycles, and Political Consequences.” International Organization 38 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1017/S0020818300004264

- Dong, Guangbi. 1997. Zhongguo jinxiandai kexue jishu shi [The History of Science and Technology in Modern China]. Changsha: Hunan Education Publishing House. (In Chinese).

- Duke, Benjamin. 2009. The History of Modern Japanese Education: Constructing the National School System, 1872–1890. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Ellinger, Barnard, and Hugh Ellinger. 1930. “Japanese Competition in the Cotton Trade.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 93 (2): 185–232. doi:10.2307/2342172

- Ericson, J. Steven. 2015. “Japonica, Indica: Rice and Foreign Trade in Meiji Japan.” Journal of Japanese Studies 41: 317–345.

- Fletcher, Alan Mark. 1993. AVRDC Story. Tainan: Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center Press.

- Friedmann, H. 1987. “The Family Farm and the International Food Regimes.” In Peasants and Peasant Societies, 2nd ed., edited by T. Shanin, 247–258. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Friedmann, H. 1993. “The Political Economy of Food: A Global Crisis.” New Left Review 197: 29–57.

- Friedmann, H. 2005. “From Colonialism to Green Capitalism: Social Movement and Emergence of Food Regimes.” In New Directions in the Sociology of Global Development, edited by Frederick H. Buttel, and Philip McMichael, 227–264. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Friedmann, H. 2016. “Commentary: Food Regime Analysis and Agrarian Questions: Widening the Conversation.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (3): 671–692. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1146254

- Friedmann, Harriet, and Philip McMichael. 1989. “Agriculture and the State System: The Rise and Fall of National Agricultures, 1870 to the Present.” Sociologia Ruralis 29 (2): 93–117. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.1989.tb00360.x

- Fujihara, Tatsushi. 2018. “Colonial Seeds, Imperial Genes: Horai Rice and Agricultural Development.” In Engineering Asia: Technology, Colonial Development, and the Cold War Order, edited by Hiromi Mizuno, Aaron Moore, and John DiMoia, 137–161. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- General Accounting Office. 1978. U.S. Participation in International Agricultural Research: Report to the Congress. Washington, DC: GAO Press.

- Geng, Xuan. 2015. Serving China Through Agricultural Science: American-Trained Chinese Scholars and ‘Scientific Nationalism’ in Decentralized China (1911–1945). Twin Cities: University of Minnesota.

- González-Esteban, A. L. 2018. “Patterns of World Wheat Trade, 1945–2010: The Long Hangover from the Second Food Regime.” Journal of Agrarian Change 18: 87–111. doi:10.1111/joac.12219.

- Gowen, Garrett, Rachel Friedensen, and Ezekiel Kimball. 2016. “Boys, Be Ambitious: William Smith Clark and the Westernisation of Japanese Agricultural Extension in the Meiji Era.” Paedagogica Historica: International Journal of the History of Education 3. doi:10.1080/00309230.2016.1178784.

- Greenland, D. J. 1997. “International Agricultural Research and the CGIAR System—Past, Present and Future.” Journal of International Development 9 (4): 459–482. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1328(199706)9:4<459::AID-JID457>3.0.CO;2-G

- Hamilton, Gary G., and Cheng-shu Kao. 2018. Making Money: How Taiwanese Industrialists Embraced the Global Economy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Hiraga, Midori, and Shuji Hisano. 2017. “The First Food Regime in Asian Context? Japan’s Capitalist Development and the Making of Soybean as a Global Commodity in the 1890s–1930s.” AGST Working Paper Series No. 2017-03. Kyoto: Asian Platform for Global Sustainability & Transcultural Studies.

- Hirano, Katsuya. 2015. “Thanatopolitics in the Making of Japan’s Hokkaido: Settler Colonialism and Primitive Accumulation.” Critical Historical Studies 2: 191–218. doi:10.1086/683094

- Hotta, Eri. 2014. Japan 1941: Countdown to Infamy. New York: Knopf Doubleday.

- Iso, Eikichi. 1954. Rice and Crops in Its Rotation in Subtropical Zones. Tokyo: FAO Press.

- Jakobsen, Jostein. 2021. “New Food Regime Geographies: Scale, State, Labor.” World Development 145: 105523. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105523

- Japanese Civilization Association. 1943. Seinen rensei no jōkyō. Takunan nōgyō senshi kunrenjo kisoku. Daininen ni okeru kōmin hōkō undō no jisseki [Guidelines in Training Toward South Agricultural Warriors. In the Second Year Work of Japanese Civilization Movement]. Taipei: Japanese Civilization Association. (In Japanese).

- Jose, Ricardo Trota. 1998. “Food Production and Food Distribution Programmes in the Philippines during the Japanese Occupation.” In Food Supplies and the Japanese Occupation in South-East Asia, edited by Paul H. Kratoska, 67–100. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ka, Chih-Ming. 1995. Japanese Colonialism in Taiwan: Land Tenure, Development and Dependency, 1895–1945. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Kang, Sang Jung, and Mooam Hyun. 2010. Dai-Nihon, Manshū teikoku no isan [Greater Japan: The Legacy of Manchurian Imperialism]. Tokyo: Kõdansha. (In Japanese).

- Kao, Shu-Yuan. 2005. “Táiwānzhàn shíshēng chǎnkuò chōngzhèng cèzhīshí shīchéng xiào: yǐgōng yèwéizhōng xīnzhīfēn xī.” [Efficacy of the Policy of Increased Production in Wartime Taiwan—an Analysis Focused on Industry.] Cheng Kung Journal of Historical Studies, 165–214. (In Chinese).

- Kim, Tae-Ho. 2018. “Making Miracle Rice: Tongil and Mobilizing a Domestic “Green Revolution” in South Korea.” In Engineering Asia: Technology, Colonial Development, and the Cold War Order, edited by Hiromi Mizuno, Aaron Moore, and John DiMoia, 189–208. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Kitamura, Kae, Satoko Hiura, and Kazuyuki Yamamoto. 2016. “Historical Documents of Shinka Common School and Shinka Agricultural Continuation School: A Step Toward Rebuilding Educational History of Colonial Taiwan.” Bulletin of Faculty of Education, Hokkaido University 126: 298–190. (In Japanese). https://doi.org/10.14943/b.edu.126.298.

- Kratoska, Paul H. 1998. “Malayan Food Shortages and the Kedah Rice Industry During the Japanese Occupation.” In Food Supplies and the Japanese Occupation in South-East Asia, edited by Paul H. Kratoska, 101–134. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kurasawa, Aiko. 1998. “Transportation and Rice Distribution in South-East Asia during the Second World War.” In Food Supplies and the Japanese Occupation in South-East Asia, edited by Paul H. Kratoska, 32–66. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-26937-2_3

- Ladejinsky, Wolf. 1977. Agrarian Reform as Unfinished Business: The Selected Papers of Wolf Ladejinsky. Edited by Louis J. Walinskey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lin, James. 2015. “Sowing Seeds and Knowledge: Agricultural Development in the US, Taiwan, and the World, 1949–1975.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society (EASTS) 9 (June 2015): 127–149. doi:10.1215/18752160-2872116

- Looney, Kristen E. 2020. Mobilizing for Development: The Modernization of Rural East Asia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Love, Harry, and John Reisner. [1964] 2012. The Cornell-Nanking Story: The First International Technical Cooperation Program in Agriculture by Cornell University. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Lynn, Hyung Gu. 2005. “Malthusian Dreams, Colonial Imaginary: The Oriental Development Company and Japanese Emigration to Korea.” In Settler Colonialism in the Twentieth Century: Projects, Practices, Legacies, edited by Caroline Elkins, and Susan Pedersen, 25–40. Milton Park, Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- McMichael, Philip. 2000. “A Global Interpretation of the Rise of the East Asian Food Import Complex.” World Development 28 (3): 409–424. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00136-9

- McMichael, Philip. 2005. “Global Development and the Corporate Food Regime.” In New Direction in the Sociology of Global Development, edited by Frederick H. Buttel, and Philip McMichael, 269–303. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- McMichael, Philip. 2009. “A Food Regime Genealogy.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 36 (1): 139–169. doi:10.1080/03066150902820354

- McMichael, Philip. 2013. Food Regimes and Agrarian Questions. Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.

- McMichael, Philip. 2015. “The Land Question in the Food Sovereignty Project.” Globalizations 12 (4): 434–451. doi:10.1080/14747731.2014.971615

- McMichael, Philip. 2020. “Does China’s ‘Going Out’ Strategy Prefigure a New Food Regime?” The Journal of Peasant Studies 47 (1): 116–154. doi:10.1080/03066150.2019.1693368

- Mitchell, Timothy. 2002. Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Moore, Aaron. 2013. Constructing East Asia: Technology, Ideology, and Empire in Japan’s Wartime Era, 1931–1945. Menlo, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Myers, Ramon H. 1984. “Post World War II Japanese Historiography of Japan’s Formal Colonial Empire.” In The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895–1945, edited by Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, 455–477. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Myers, Ramon H., and Saburo Yamada. 1984. “Agricultural Development in the Empire.” In The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895–1945, edited by Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, 213–239. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Nagano, Yoshiko. 1998. “Philippine Cotton Production Under Japanese Rule, 1942–1945.” Philippine Studies 46 (3): 313–339. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42634270.

- National Development Council. 1994. Taiwan Statistical Data Book. Taiwan (R.O.C): National Development Council.

- Nguyen, The Anh. 1998. “Japanese Food Policies and the 1945 Great Famine in Indochina.” In Food Supplies and the Japanese Occupation in South-East Asia, edited by Paul H. Kratoska, 208–226. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-26937-2_9

- Patel, Raj. 2013. “The Long Green Revolution.” Journal of Peasant Studies 40 (1): 1–63. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.719224.

- Perkins, John H. 1997. Geopolitics and the Green Revolution: Wheat, Genes, and the Cold War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pritchard, Bill. 2009. “The Long Hangover from the Second Food Regime: A World-Historical Interpretation of the Collapse of the WTO Doha Round.” Agriculture and Human Values 26: 297–307. doi:10.1007/s10460-009-9216-7.

- Pritchard, Bill, Jane Dixon, Elizabeth Hull, and Chetan Choithani. 2016. “‘Stepping Back and Moving In’: The Role of the State in the Contemporary Food Regime.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (3): 693–710. doi:10.1080/03066150.2015.1136621.