ABSTRACT

In 2017, 97,61% of the people of Cumaral, Colombia, voted in a popular consultation against having the oil industry in their municipality. However, this historical result was challenged by the government in court and ultimately overturned in 2018. By looking into the origins and strategies employed by Cumaral's environmental movement, we argue that their success involved turning a diverse, and even contradictory, collective into a singular voice that could reject the state’s development agenda. We thus highlight the combination of factors that led to the consultation result showing that an effective way of resistance can be achieved through the state.

Introduction

For many countries in Latin America, the extraction of oil and minerals has been the main policy for governments in order to accelerate economic development. This expansive form of extractive capitalism has sought to take advantage of high international prices and demand for commodities to propel social spending (Ulloa and Coronado Citation2016; Gudynas Citation2019). For these same governments the negative social, environmental and economic impacts are to be tolerated as long as they solely affect disadvantaged communities – usually ethnic minorities, the poor and the peasantry. Yet this crude form of accumulation by dispossession has not gone unchallenged by groups of people that do not want their livelihoods taken away from them (Harvey Citation2005). A particularity of these kinds of social movements of resistance against extractivism is their heterogeneity – combining multiple actors – in contrast to historic class-based expressions of agency for social change (Schuurman Citation1993). Rather than struggles based on social class, wages or land, these are ‘communities in struggle’ fighting against a neoliberal agenda and the destructive impacts of extractive capitalism (Bebbington and Bury Citation2013).

Among the many resistance strategies employed by local communities, popular consultations (consultas populares) became one of the main tools in Latin America to mount resistance and halt the encroachment of extractive industries into their territories (Rasch Citation2012; Walter and Urkidi Citation2017). Popular consultations are direct democracy mechanisms through which people can decide upon a policy question at the municipal, regional or national level (Barczak Citation2001; Roa-García Citation2017). The results bind the relevant layer of government to implement the decision. Hence, popular consultations allow people to build a collective voice that can dialogue and put pressure on the state (López y Rivas Citation2011). In Colombia, for the brief period between 2013 and 2018 ten popular consultations in an equal number of municipalities were carried out against extractive industries and large hydroelectric-power (See ). Promoted by the environmental movement for the defence of water resources and local livelihoods, popular consultations led to unlikely alliances of traditionally opposed actors that found their interests aligned in opposition to resource extraction. In all popular consultations people voted massively (>95% of the people) against having the industry in their territory. In this article, we use the case of the popular consultation held in 2017 in the municipality of Cumaral, Colombia, where 97.61% voted against the oil industry, to explore the intricacies of direct-democracy in development politics. We argue that Cumaral’s remarkable resistance against dispossession involved employing a series of mechanisms that turned an otherwise diverse collective into a singular voice that could dialogue with powerful actors and ultimately reject their extractivist development path.

Table 1. Popular consultations on natural resource use and exploitation in Colombia 2013–2018.

The conservation of water resources and protection of local livelihoods were the main arguments espoused by environmental movements for the different consultations. This is the case as the impacts of oil, gas and mineral extraction involve a large-scale use of surface and groundwater as well as the dumping of industrial wastewater into the natural environment. Furthermore, these industrial operations run the risk of spills and accidents that can severely, and even permanently, damage the local ecosystems thereby destroying people’s livelihoods by taking away their means of production (Martinez-Alier Citation2014). To stop the avalanche of another 54 popular consultations that were being organised (La Republica Citation2018), the national government cut down the funding and, in concert with corporate interests, challenged their legality in court (cf. Brock Citation2020).

Despite the remarkable outcome from all ten popular consultations, in 2018 the Constitutional CourtFootnote1 changed its precedent, and ruled in favour of the Chinese-Indian oil company, Mansarovar Energy, that the popular consultation carried out in 2017 in the municipality of Cumaral was unlawful. This first ruling, that concerned only the popular consultation of Cumaral, was followed by a 2019 ruling where the Constitutional Court struck down the possibility that municipalities had had access to since 1994 to hold popular consultations when a ‘development project for tourism, mining or of another kind, threatens to create a significant change in the land-use, and such a project transforms the traditional activities of a municipality … ’ (Law 136 of 1994). Thereby, the court effectively forbade popular consultations against extractive industries (Bocanegra Acosta and Carvajal Martínez Citation2019). Such scaling down of citizen participation diminishes the type of state described in Colombia’s Constitution in which citizens get to participate in the decisions that affect them (Garcés Villamil and Rapalino Bautista Citation2016, 61). Moreover, while the outcomes from the popular consultations effectively stopped the expansion of the oil industry, they also tended to obscure the local inequalities and disparities present in these same areas (Acosta García Citation2022). Hence, an analysis of the origins and social basis of the social movement is needed to reveal both their pitfalls and their revolutionary potential against extractivist policies (Veltmeyer Citation2019).

The implementation of neoliberal reforms in Latin America has been studied in-depth, showing that extractivist policies do not necessarily translate into social progress and, on the contrary, that they are usually related to poverty, violence and armed conflict (Bebbington et al. Citation2008; O’Connor and Montoya Citation2010; Vélez-Torres Citation2014; Le Billon, Roa-García, and López-Granada Citation2020). The conclusion of these studies is that reforms have benefitted a minority of people and have also created a ‘relative surplus population’ that is both deprived of its means of production, and is not absorbed by expanding capitalism (Sassen Citation2010; Li Citation2017). In the context of rural Colombia, this is exacerbated by successive botched efforts at tackling a colonial legacy of highly unequal land distribution across the country (Faguet, Sánchez, and Villaveces Citation2020), which forces small-holders to seek employment as agricultural workers. Furthermore, a history of violent land-grabbing has left many peasants and ethnic minority groups without land (Villarraga Sarmiento Citation2014). In these places, the ways in which part of the population is incorporated into, or excluded from, the labour force is at the root of contemporary rural conflicts. One such conflict arises, for example, from the way in which companies employ hierarchies (e.g. technical, ethnic, geographical) for the recruitment of workers (Rubbers Citation2020). For example, oil companies in Colombia are contractually required to recruit blue-collar workers solely from the often-economically deprived local communities, while white-collar workers can be brought into the region. As oil companies pay higher salaries to rural workers than agriculture, having access to such jobs is a matter of contention for both local employers competing for workers and for workers who try to secure better pay. What is important here is to note that many rural areas intended for oil exploration in Colombia have a legacy of capitalist expansion that in its latest form – dispossessive extractivism – is one among many other forms of exploitation that are already present.

As unlikely allies (e.g. peasants and large estate owners, agricultural workers and oil palm plantations, etc.) worked together in Cumaral to stop the incursion of the oil industry, we seek to shed light upon their motivations, interests and contradictions. For Harvey (Citation2005) different sectors of society experience exploitation in particular ways according to the regimes of accumulation that they are subjected to. Drawing on Harvey's (Citation2005) work, Wolfson and Funke (Citation2018) argue that the regimes of accumulation (or ways of appropriation of surplus-value) that structure contemporary capitalism generate identifiably distinct sectors of the working class – in particular they distinguish between two regimes: accumulation through expanded production and accumulation by dispossession. This distinction can serve as a typology between the changing forms of class struggle and resistance (Leonardi Citation2019; Veltmeyer Citation2019). Hence, we aim to discern between the interests of the diverse and otherwise opposing actors present in Cumaral (i.e. rural workers and oil palm plantations), whose interests appear aligned in opposition to the oil industry.

Our argument is organised in the following way. After this introduction, we reconstruct the history of resistance against extractivism in Cumaral, following the two most recent periods of dealing with and resisting oil companies. Then, we provide an analysis of the main factors that influenced the success of the environmental movement of Cumaral. This is followed by the conclusion. We focus on the case of Cumaral for two reasons. First, virtually all of the research on popular consultations has focused on the case of goldmining in Piedras, Tolima.Footnote2 While Piedras, Tolima, is worthy of special attention due to its being the first such case, it should not be taken as representative of the opposition to extractivism through popular consultations as a whole. Thus, other case studies, such as Cumaral, are desirable as a corrective. Second, the fact that the Constitutional Court overturned Cumaral’s decision allows us to tease out some of the contradictions inherent in overturning people’s decisions against a particular form of development intervention.

This article is based on ethnographic fieldwork carried out by the authors in Cumaral between 2020–2022 covering different periods of time amid COVID-19 restrictions. Source data includes interviews and archival materials. We conducted 20 interviews with people involved with the organisation of the popular consultation in Cumaral, among whom were teachers, farmers, owners of the local commerce, agricultural workers, priests, as well as activists that work at a national and regional level (i.e. NGOs and academics). Some of the interviews were conducted online and the majority in person. Because of the great security risk that environmental activism carries in Colombia (Le Billon and Lujala Citation2020), we use pseudonyms and omit identifying characteristics of participants. Archival materials include the official documentation and correspondence pertaining to the environmental licenses and contracts for Llanos 59 (Ministry of Environment Reference: LAM5790) and Llanos 69 (Ministry of Environment Reference: LAV0094-00-2015).

The first struggle – know thy adversary

Located on the grasslands (Llanos) of the Orinoco River basin, Cumaral is one of 29 municipalities in the department of Meta, which produces nearly half of Colombia’s oil (ANH Citation2022). Cumaral is a relatively small municipality with just over 21,000 inhabitants and its main urban centre is located on the spurs that stretch from the Andes into the flatlands. To reach Cumaral by car, it takes four hours from Bogotá and less than 40 min from Villavicencio, Meta’s regional capital. In Cumaral, the streets are wide, bustling with commerce, and lanes are gardened with fruit trees. Most of the houses are one storey and have tin rooves. While this region is rich in water resources, during summer months (Dec-Mar) people struggle to meet their water needs. Colombia’s Llanos have a long-standing tradition of extensive cattle ranching, and most land is in the hands of large estates (latifundios) (García Gutiérrez and Pulido Castro Citation1999). In the past few decades the production of oil and the expansion of oil palm and rice monocultures, some owned by the richest people in the country, has transformed the regional economy, which now also hosts tourism alongside these economic activities (Rausch Citation2009).

Historically, local resistance against oil companies can be understood as a response to the policies for oil exploration of president Uribe’s (2002–2010) right-wing government, whose economic plan had increasing oil production as one of its main ambitions. The government’s ANH (National Hydrocarbon Agency)Footnote3 auctioned areas across the country so oil companies could explore and eventually exploit the resource. According to Colombia’s Constitution, underground and non-renewable resources are owned by the state. Hence, when the government grants rights to an oil or mining company, there is a tension between the people that use the land (e.g. land owners, peasants, indigenous peoples) and the company. While both groups have conflicting rights over the same space, according to the LawFootnote4 the mining and oil industries are considered of ‘public utility and social interest’ and hence their rights prevail. After acquiring such rights over a determined area, a company proceeds to conduct seismic exploration. This involves placing geophones and explosive charges in a grid, buried in the ground, to detect the potential of hydrocarbons stored in the bedrock (Talwani and Kessinger Citation2003, 710). Usually, seismic exploration and the environmental licensing from the environmental authority ANLA (National Authority of Environmental Licenses)Footnote5 run in parallel. Seismic exploration is not subject to the same environmental controls as other activities related to the oil industry.

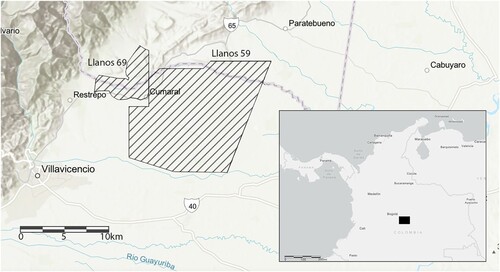

As seismic exploration involves having access to people’s farms to place both the explosive charges and geophones, it was during this first step in 2011 that the inhabitants of Cumaral say they first found out that their farms and homes could potentially become part of an oil field (Prensa Libre Citation2011). The Canadian company Petrominerales had won in ANH’s 2010 auction the rights for oil exploration in an area designated as Llanos 59 on the eastern side of Cumaral, as well as in the adjacent municipalities of Restrepo and Paratebueno (see ). Then, according to Angelica, president of one of the urban JAC (Juntas de Acción Comunal – Local Community Boards) of Cumaral, the company first organised a meeting in early 2012 with all the presidents and the mayor (José Albeiro Serna 2012–2015) to present what their activities were going to be. It is worth noting that while urban JAC members in Cumaral live mostly in poor and lower-income areas, rural JACs are made up mostly by working-class and wealthy landowners. Soon after, Angelica explains

the company contacted one of the presidents and told them what vacant positions they had. These were always for blue-collar workers. The company would bring their own people [for white-collar jobs] and here they would find the blue-collar workers. The president of the JAC then would make a raffle among his or her constituents to find who would get the jobs … but this was very disorganised, there were rumours of corruption, people selling their spots instead of working …

Figure 1. Map of the Meta department displaying the oil exploration areas of Llanos 59 and Llanos 69.

This is not an uncommon practice in extractive industries in Colombia: companies seek to approach the JACs with job offers as a way to gain access to the areas, which in turn sets the basis for fragmenting labour (cf. Rubbers Citation2020). During this period the company conducted its Environmental Impact Assessment and began its seismic exploration.

The seismic exploration covered 75.5 square kilometresFootnote6, which included part of a rural area known locally as Chepero. According to a complaint sent to ANLAFootnote7 on Jan 2012 by one of our interviewees among others, the explosive charges of the seismic exploration triggered over 120 landslides affecting 10 farms, some of them with damages in over 30% of the total farm area. For the farmers the damages were irreversible, and beyond the landslides, there was also a 15-meter drop in the water table thereby affecting their wells and the water availability during summer months. Due to such stark impacts, local residents began meeting up and organising, thus giving shape to what would become the environmental movement.

A few months later in 2012, local activists collected signatures of over 200 people from Cumaral and Restrepo in order to request that ANLA hold an environmental public hearing. This is a public participation mechanism that serves as a forum for local communities to know and ask about a project’s permits and licenses, its impacts and the measures taken to manage them.Footnote8 This type of meeting has been used by the environmental movement across the country as a way to delay the licensing process and as a space for local communities to challenge the official narrative (McNeish Citation2017; Roa-García Citation2017). According to Alvaro, a local activist and entrepreneur in his fifties, during the hearing representatives from diverse local organisations from the three affected municipalities were given the opportunity to present their views. This included members of the department’s assembly, municipal ombudsman offices, local schools, farmers associations, among others. In ANLA’s archivesFootnote9, it is recorded that over 300 people attended the meeting. The great majority of them were against the oil exploration project as it would negatively affect the local ecosystems and water resources, as well as drastically transform the land-use from tourism, cattle ranching and industrial agriculture to oil industry. Highlighting the relevance of the event, it was also attended by the minister for the environment, the CEO of the national oil company Ecopetrol, representatives of Petrominerales, and the director of ANLA, all of whom claimed – to the chagrin of the local communities present in the meeting – that oil production could be done in a way compatible with the environment.

Among the arguments taken up by ANLA to finally grant the license in 2013 was that the area was already affected by farmers’ activities in the form of deforestation, and that people’s active participation in the public hearing showed that they had ‘sufficient and adequate knowledge of the [oil exploration] project’ (ANLA Citation2013, 58). Later that year, Petrominerales was bought by the Canadian company Pacific Rubiales – which planned to drill four exploration wells in Llanos 59 (Bloomberg Citation2013). With the collapse in oil prices in 2014 and high levels of debt, Pacific nearly went bust and was bought by Frontera Energy, another Canadian company. Shortly after, Frontera shelved the plans for Llanos 59 and in 2016 surrendered its contract with ANHFootnote10 (Pacific Exploration and Production Corporation Citation2016, 63).

For the residents of Cumaral the experience with Petrominerales foreshadowed what could come if oil was ever discovered in the area, and served as a prelude to the popular consultation.

The second resistance: ‘when we’re thirsty we are not going to drink oil’

In 2015 came the news that an oil company called Mansarovar (A Chinese-Indian company) was going to conduct seismic exploration in an area called Llanos 69. This area covered the western part of the municipality of Cumaral that includes part of the plains and foothills of the Andes, where local rivers are formed and the local aquifer recharges. The area also included the adjacent municipality of Medina. Llanos 69 had been awarded to Mansarovar Energy during ANH’s 2012 auction. Unsurprisingly, when seismic exploration began it was met with fierce resistance on all fronts.

On the institutional side, as reported by the company itself to ANHFootnote11, the mayor of Medina forbade the mobility of the heavy machinery through the municipality’s roads. Although it was later withdrawn, the Mayor’s Decree sent ripples all the way to Bogotá due to its strong wording:

the people of Medina, have manifested in peaceful yet staunch ways their nonconformity and complete opposition to the execution of Mining and Energy projects … the people have requested a popular consultation to establish the defence of democracy and sovereignty over our territory. If there are no legal alternatives presented on behalf of the municipality, the community shall take direct action to impede the transit of this machinery which will cause the alteration of public order … (Alcaldía de Medina Citation2016, 3).

Based on the previous experience of resistance against Petrominerales, people in the environmental movement realised that they needed to influence local politics if they were going to organise a popular consultation. The point of reference was the success of the two first popular consultations of Piedras and Tauramena. Juan is a man in his thirties and as a result of his activism he was elected in 2019 to the municipal council. Juan recalls attending an event organised by an environmental NGO on popular consultations in 2015:

in that event I met the people from Tauramena and they gave me the contact details of … a lawyer who would later be the lawyer that made our popular consultation … he explained to us what we needed to do, how the popular consultation was … that was the moment when one could say that the process of the popular consultation began.

In addition to getting a lawyer to guide them, the environmental activists sought training from Oscar Vanegas, a professor from the School of Petroleum Engineering of the Universidad Industrial de Santander. He is both an academic, environmentalist and a public figure who has run for congress on an anti-extractivism platform. He came to Cumaral and explained to the activists the political economy of oil production in Colombia where the lion’s share of the profits is taken by foreign oil companies leaving behind a trail of environmental and social issues. Soon after, the local activists began working towards the popular consultation. In a way, rather than allowing activists to seize or challenge state power, the popular consultation allowed the activists of Cumaral to imagine anew their municipality without the oil industry (Holloway Citation2010). As a precaution, the few that began working on the promotion of the popular consultation made sure that there was no visible head, in order to avoid being targeted by the unfortunate violence that surrounds activism and human rights defenders in Colombia and in Latin America in general (Le Billon and Lujala Citation2020).

According to the Law, there are two routes to organise a popular consultation at the municipal levelFootnote12: it can be proposed by grassroots organisations through the collection of signatures or by the local mayor to the municipal council. The first attempt to call for a popular consultation took the former path of collecting signatures. The idea was that the presidents of the JACs would lead the process of collecting signatures across the municipality. In order to have access to all the people active in the JAC, the activists needed to become the presidents of the JACs. According to our interviewees, the activists used the JACs to gain access to their neighbours. This allowed them to convince those that were in favour of having the oil projects to change their minds.

On the corporate front, we were told that as a way to exert pressure and shore up support, Mansarovar would pay money directly to the JAC as investment for local projects. That said, social investment is a contractual obligation for oil companies, which serves the state as a way to overcome local resistance (Verweijen and Dunlap Citation2021), and to outsource part of its obligations to its citizens (Hilson Citation2012; Rabello, Nairn, and Anderson Citation2019). ANH’s records show that Mansarovar had to invest at least US$143,000 in local community projects during seismic exploration. The company wanted to spend this money training 15 people for its own benefit, so that they would become blue-collar workers and another 10 that would act as leaders promoting community-led projects.Footnote13 After the opposition of several JACs, the company ended up paying in 2017 for construction materials for local schools, and improving a few roads.

As the process of collecting signatures coincided with the 2015 elections, it was postponed to avoid the risk of politicians using the popular consultation as a campaign pledge. Slowly the popular consultation committees started taking shape. There were two groups of environmentalists with two different campaign headquarters. One led by entrepreneur and poultry farmer Alberto, and a second group that served later as political platform for future politicians. This latter group was heterogenous as it was organised by people with low-income professions (i.e. small-scale farmers, shoemakers, etc.) as well as by well-off activists who claim to trace their lineage back to the foundation of Cumaral and are known locally as part of the ‘traditional families’ of the town. Although communication at times between the two groups was difficult, Alberto explained that their common goal made them work together in creating the campaign materials and organising the rallies.

The committees brought together a plurality of actors that included teachers from the local schools, owners of the local commerce, clerics, environmentalists, politicians, cattle ranchers, fish farmers, and even the oil palm plantation owners and the plantation workers. The reason behind involving the plantations, as Gabriel an environmental leader told us, was because the plantations were also going to be affected by the reduced water availability for irrigation due to the oil production and be impacted by increased labour costs (cf. Sánchez Plaza Citation2016). Regarding the former, the two main water users in the rural area are a community-managed irrigation district with 11.2 m3/s that supplies rice farms, oil palm plantations and cattle ranches, and Unipalma’s with 6.1 m3/s for the largest oil palm plantation (Centro de Investigaciones sobre Dinámica Social Citation2015). In addition, the activists figured out that despite their huge environmental impact the plantations could be allies. Gabriel explained that, ‘they were fundamental because they offer 35–40% of the local employment’. Regarding the latter, in the area, there is a recurrent labour conflict between the palm oil plantations and local unions demanding better wages and work conditions. We were informed by cattle ranchers and environmental activists that shortly after the beginning of the exploration of Llanos 59 in 2012, agricultural wages had gone up in the region, making it more costly for oil palm companies to hire labour. Juan puts this in terms of people’s motivations:

[during] the popular consultation the oil palm plantations were defending their guild, the cattle ranchers were defending their cattle, the mothers were defending public morality, fearing that Cumaral would not become a municipality with high levels prostitution. Everyone was defending their own interests and their vision of development.

That Miguel Antonio Caro (2016–2019) was elected as mayor for a progressive left-wing party was a great omen for the resistance movement against oil extraction. According to several of our interviewees, it was difficult for the previous mayor to come forward in support of the popular consultation as ‘the blackmail was very strong … it practically meant saying to the national government that there is no need for investment in any [new development] project’ (interview with Juan). Furthermore, the Office of the Inspector General (Procuraduría) began sending warnings to all mayors that it was against the law to hold a popular consultation against the oil industry (Procuraduría Citation2012).

Despite the warnings, the new mayor took charge of the popular consultation and in October 2016 presented a proposal to the municipal council (Alcadía de Cumaral Citation2016). The text had as its main motivation that a significant number of residents

consider that the Contract … between the ‘ANH’ and the company Mansarovar … will irreparably affect water resources of: rivers, streams, springs, wetlands, morichales, lakes, fauna and flora and wells, which even provide the natural resource (water) to other municipalities than Cumaral …

The collected signatures served as a way to show that the mayor had the people’s support. Of the 11 council members 6 had to vote in favour. According to Juan, the campaign focused on meetings, workshops and events to ensure that the popular consultation convinced the majority of council members. National political parties also exerted pressure on the council members conditioning their support for future campaigns to voting down the popular consultation. The oil company also lobbied council members. A month after the mayor submitted the proposal to the municipal council, eight council members voted in favour and the popular consultation moved forward to the next step: the revision by an administrative court to determine its constitutionality. The question read as follows: ‘Do you citizen of Cumaral agree that within the jurisdiction of the Municipality of Cumaral activities of seismic exploration, production, transport and commercialisation of hydrocarbons may be carried out?’ In March 2017, the regional Administrative Court ruled that the question and process was constitutional, and could proceed. The mayor thus set a date for the consultation: Sunday, June 4th 2017.

On the corporate front, Mansarovar kept ramping up the pressure to speed up its seismic exploration activities, heightening the tensions between the companies’ contractors and the general population. Through its contractors Mansarovar offered jobs to rural residents, which made people in those areas hesitate in their support for the popular consultation. As Angelica, the president of a JAC, puts it

we were afraid that for a job in an oil company, that just lasts for a month, people would favour extraction … and I think, what do they get out of that? Someone gets a couple of million pesos, spends them on trinkets, and the municipality is badly affected because it affects food prices, rental prices and the land, and that on top of the social impact.

Such temporary jobs, while still belonging to the precariat, provide much better incomes than regular agricultural jobs.

Indeed, the salaries offered by oil companies and their contractors can be several times higher than regular agricultural wages. To put this in context, salaries of agricultural workers across the country are about 70% of the legal minimum wage (Otero-Cortés Citation2019, 14). According to 2018 census data (DNP Citation2022), 22.27% of Cumaral’s population was living under poverty conditions and 22.9% of the population had no access to running water. Most of the available employment, 77.02%, in the municipality was informal, which means that workers were not being paid wages according to the law and are neither making social contributions nor paying taxes. The majority of the employment is provided by the oil palm plantations that add up to ca. 24,500 ha. The largest single plantation is Unipalma’s with 4,500 ha which is jointly owned by Colombia’s richest man Luis Carlos Sarmiento Angulo and Unilever (Las2orillas Citation2022). According to the collective agreement signed with the workers union in 2016, Unipalma agreed to hire directly 150 workers and pay them salaries that are slightly above minimum wage. This is significant since there were only ca. 1700 people with formal contracts in that year in Cumaral (DNP Citation2022). In contrast, 2016 job advertisements from the seismic contractor offered between one and two minimum legal monthly salaries (Servicio Público de Empleo Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Hence, it is not surprising that many people would seek to get employment with Mansarovar and its contractors.

One of the challenges that the committees had to overcome was raising funds. Fundraising began slowly through raffles, fairs and through the sale of t-shirts. As the date of the elections got closer funding began pouring in. Many people gave donations in cash and kind – this included the rich owners of the large cattle ranching estates and the oil palm plantations. When asked about the source of funding, several informants explained that most of the support came from medium and small-size family businesses, which at a later stage, was joined by the larger companies present in the area.

The second challenge was organising the campaigning. Several members of the committees quit their day jobs to dedicate themselves full-time to the campaign. The two committees trained the activists so they would visit people in their homes:

We would say to the people how are we going to turn Cumaral into an oil town? That money is not for us, they take it and we are left [to deal] with all the troubles … It is better to have water because when we’re thirsty we are not going to drink oil (Interview with Angelica)

Activists were assigned to different areas within the municipality so they would visit every single house. For Sandra, being a teacher facilitated the campaigning process: ‘it was more like doing a family visit … having coffee together and telling them the story [of the popular consultation]’. Sandra had her family involved in helping out with door-to-door visits. Her family and other activists organised a call-centre where they answered questions as well as allowed campaigners to call people to remind them to vote and to do it early in the day. To counteract this, the oil company offered scholarships in China to the young activists to conduct graduate and postgraduate studies if they would desist from their campaigning.

In the last weeks of May during the run-up to the consultation many other environmentalists from across the country came to Cumaral in solidarity in order to support the campaigning effort. This contingent included election monitors and academics. Local activists welcomed them to their homes. At the same time, the national media began taking notice of Cumaral as the campaigners were able to rally support from national artists (Semana Citation2017). On the other hand, Mansarovar had begun a series of lawsuits aimed at stopping the popular consultation from taking place. These were supported by the national government through its legal defence agency and by the Ministry of Mining and Energy arguing that the question was against the constitution and that there were procedural issues with how the popular consultation was called (Corte Constitucional de Colombia Citation2018).

On May 30th 2017, the Tuesday before the vote, the highest administrative court in the land ruled against the oil company thereby clearing the last legal challenge. In Cumaral, the committees organised a Demonstration-Carnival in order to rally support for the popular consultation (cf. Badillo Mendoza and Marta-Lazo Citation2019). Lina, one of the activists involved in the process recalls that one of the committees called for a horse parade – a way to celebrate in the Llanos rooted in the region’s cattle ranching traditions. This created a competition for which committee was more prominent in motivating people to come out to celebrate. According to the people we interviewed, they were confident the ‘No’ would win. However, they were concerned that the popular consultation would not cross the threshold.

The day before the vote the army was present all over town. The activists in both committees knew that the government had provided a reduced number of polling stations. At six in the morning there were already long lines of people waiting for the polls to open. Activists and local companies provided free transport to bring voters to the polls, the owners of the oil palm plantations provided buses for their workers. Some of the activists were stationed at the entrances of the polling stations counting how many people went in. This way they could report irregularities, should they arise. Two hours before the polls closed, the committees knew the popular consultation had crossed the 33% voter-threshold. Nevertheless, the committee kept asking people in town to vote to ensure that the results were well above the threshold and harder to challenge in court.

The results came at 5pm: 48.52% of the people had gone to the polls (7658 people), out of which 183 voted in favour and 7475 against the oil industry, which represents 97.61% of the total votes. That night the town was overcome with joy and celebrations. For many of the people we talked to this was a significant moment in their lives. For example, one of them named their child Victoria as a reminder of their activism.

This success was short lived. In 2018 the Constitutional Court revised the ruling made by the highest administrative court and conducted a review of its previous rulings.Footnote14 The Constitutional Court determined that the prerogative that municipalities had since 1994 to hold popular consultations was unconstitutional on the grounds that decisions taken at a local level cannot step into the sphere of decision-making of the national government regarding non-renewable natural resources, which in the Constitution are said to belong to the state.

In 2020 and 2021, we conducted fieldwork and asked our participants to reflect upon what has happened after the popular consultation and the court ruling. This prompted mixed reactions. For David, a farmer in his fifties,

the consultation’s ultimate purpose was to defend sovereignty. Sovereignty is not only defended by soldiers … and beyond the environmental issues … [what we wanted] was to make the state respect our territory which is ours and … we are the only ones that have the capacity or competence to decide upon it.

The process served as a forum for people to meet one another, become active political subjects and create a collective voice that could negotiate directly with powerful actors (López y Rivas Citation2011). However, for Alberto, who led one of the committees, ‘the Court’s decision damped the environmental movement. People stopped believing and fighting. We did not expect that this [the court’s decision] would happen.’ Yet to him, ‘people’s mentality changed. People in Cumaral today love water. People think about water before making any decision. That’s what is left. We wrote in the land something very impactful, that if we defend the land, everyone defends it as well’ – in other words, the solidarity displayed during the popular consultation process could be reignited in the future. Furthermore, in our correspondence with the ANH and review of ANLA’s archives in 2022, it seems that at least for now, the two companies that purchased the exploitation rights for Llanos 59 and Llanos 69 surrendered their respective contracts. It is nevertheless possible that these two areas become auctioned once again in the future by the ANH – however, the people of Cumaral will not forget their mobilisation and will surely mount resistance once again. Since late 2018, on the southern side of the town one finds a cattle-dealing place and the Plaza de la Consulta (Square of the Consultation), renamed officially after the popular consultation. Thus, it serves as a reminder of the cattle-ranching tradition and the town’s pride in achieving the remarkable results of working against resource extraction.

The polyphonic voice of the people

The environmental movement for the popular consultation managed to create a collective voice capable of negotiating directly with the state (López y Rivas Citation2011). Its effectiveness is displayed, for instance, in the high-level environmental public hearing attended by ministers and senior management of Ecopetrol. The environmental movement of Cumaral employed a mix of strategies, such as civil disobedience, alleged damage to seismic equipment and road blockades, that first challenged the authority of the state and then sought to subvert it by appropriating its own institutional tools, some linked to environmental protection. This included, for instance, the public hearing, sending letters and complaints to environmental authorities, the municipal decrees that banned heavy traffic, and later, the popular consultation itself that had the defence of water resources and local livelihoods as its main slogan. Such strategies of appropriating and making use of institutional mechanisms for resistance show that an effective way to face dispossession in the long-term is through the state (Bebbington Citation2013).

The seemingly unified voice that led to the popular consultation, however, obscures the diversity contained within the environmental movement itself. To understand the potential that the popular consultations had in catalysing structural change, we need to look at the material interests that the environmental movement in Cumaral represented (Veltmeyer Citation2019). In Cumaral prior to the arrival of oil companies there was already an established regime of capital accumulation by expanded production. For example, oil palm and rice plantations in the municipality accumulate capital, in part, through the appropriation of surplus-value produced by the agricultural workers, through expanding the workforce, and the exploitation of the seasonal water resources – with clear class contradictions between, on the one hand, agricultural workers and urban environmentalists and, on the other, the oil palm plantations owners. Nevertheless, the environmental movement against the oil industry led by the committees that promoted the popular consultation managed to rally an array of diverse actors and bundle them up together under a single cause. The committees were made up of people located across the social structure that included the precariat such as students and volunteers, the working class (i.e. the teachers, agricultural workers and other public employees with job security), as well as people that are placed within a minority of Cumaral’s population in terms of high incomes, wealth and location in the social structure. In this sense, the committees managed to rally unlikely groups of people that found their interests aligned in opposition to oil extraction and in agreement of the protection of local livelihoods and water resources – despite the fact that some of them stood to make monetary gains if oil was discovered and exploited in the area (e.g. through increasing wages, increasing business for local commerce, property price speculation, etc.).

The protection of water resources worked as a binding element for the many struggles already present in the region such as forced displacement, land-grabbing and capitalist expansion. In contrast to the ‘water grabbing’ dynamics that have taken place in other Colombian regions where water resources are privatised in favour of large economic interests (Vélez-Torres Citation2012; Ojeda et al. Citation2015), in Cumaral, with the oil exploration and eventual oil production of Llanos 69, water resources ran the risk of becoming unusable with clear implications for social reproduction, biological reproduction and expanded production. Today, the population of Cumaral, in both urban and rural areas, continues to struggle to meet its drinking water needs during seasonal periods of scarcity. Local communities in Cumaral depend for their drinking water on tapping into surface aquifers during the eight months of the rainy season and on groundwater to complement their supply during the four months of the dry season (Rinaldi, Roa-García, and Brown Citation2021). During the dry season, in the urban area water is rationed, while on farms people depend on wells for water provisioning. Such vulnerability became explicit when seismic exploration for Llanos 59 left a trail of damages on people’s farms that included the drying of wells due to the dropping of the water table, landslides and the destruction of local roads. Moreover, Llanos 69 covered the mountainous areas where aquifers recharge and where the intake areas for the local waterworks are located. Hence, the possibility of having local water resources contaminated or depleted during a second round of oil exploration of Llanos 69 was seen as an existential threat to all economic, social and cultural activities in the municipality – one which people were unwilling to tolerate. For this reason, we can explain the wide opposition reflected in the outcomes of the popular consultation where 97.61% of the people voted against.

The social protest against the oil industry as a whole can be understood to be a response to a regime of accumulation by dispossession (Harvey Citation2005). Dispossession is both material and symbolic. Activists used the successes of other popular consultations in the country to showcase the material effectiveness of this mechanism against dispossession. In particular, they succeeded in showing that a popular consultation allowed the complete rejection of the oil industry instead of altering or proposing compensation measures that would still permit oil projects to move forward (e.g. environmental public hearings, complaints, environmental impact assessments, etc.). Symbolically, the campaign itself for the popular consultation followed traditional campaigning activities that local politicians employ to get elected, such as the door-to-door pedagogical visits carried out by the teachers and the presidents of the JAC, using joropo traditional music to create campaign jingles, and horseback parades that resonate with the local cattle ranching traditions of the Llanos region. The success of the campaign relied on the grassroots organisation as well as on the funding of the wealthy cattle ranchers and palm oil plantations. This combination of electoral campaigning, traditional symbolism, local identity, wealthy local actors and an institutional mechanism allowed the people of Cumaral to stand against dispossession.

The national policies and a sequence of actions by the government and the oil companies set them on a collision course with the population of Cumaral. On the national level, during the course of the past three governments, national policies have aimed at bringing foreign investment into the country to raise oil production in order to finance the state’s social spending (Mitchell Citation2009; cf. Brock Citation2020). Underpinned by the constitutional precept that underground resources belong to the state, these policies translate into the auctioning of areas to oil companies that then have the rights of exploration and exploitation of the resource – in other words, one largescale landgrab (Borras et al. Citation2012). On the local level, the national government actively worked together with oil companies so that they could have access to the sites for seismic exploration and eventual oil exploitation. Furthermore, people’s irritation with the way they found out that oil companies had been granted the right to exploit underground resources, has to do in part with the auctioning of the areas carried out by the ANH. These areas impose interpretation matrixes over space overruling and even erasing existing boundaries, thereby symbolically dispossessing people and making those spaces available for accumulation (Harvey Citation2005; Acosta García and Fold Citation2022). Such processes are carried out regardless of the local people that live in these areas and that are seen more as a nuisance standing in the way of development than as rightful owners, residents and citizens with rights.

That the people we interviewed discussed popular consultation in terms of sovereignty is not haphazard. Akin to Graef's (Citation2013) work in Costa Rica, this case shows that prioritising environmental protection could change the conception of sovereignty through the incorporation of notions of human-environment relations into development disputes. In this case, there is a clash between three domains that claim sovereignty. First, the government, as a sovereign power, has the prerogative to enfranchise rights (Blom Hansen and Stepputat Citation2006; Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018) – in this case, those of exploitation of underground resources. Second, the municipalities have the power to decide upon local land-use. And third, the people and their rights to decide upon their property. Local activists positioned the environmental movement as taking action against the national domains – in part, as we have argued, by employing electoral tropes that resonate with the local identities and traditions and by positioning the oil industry as something imposed from outside, from Bogotá. The fact that people voted and that the results were overwhelmingly against the oil industry clearly shows the will of the people.Footnote15 Yet, the government sided with the corporations in court, which ultimately changed court precedent, thereby overriding the democratic process. As there cannot be oil exploitation without above surface activities, the government’s policies in effect dispossess the people from their rights to identity, livelihoods, and property so that oil companies can produce and accumulate capital.

Conclusion

In this article, we traced the recent history of the environmental movement in Cumaral showing the different stages of resistance against the incursion of the oil industry. We have shown the different strategies employed by activists to halt the encroachment of the industry. These have ranged from using institutional mechanisms, such as the organisation of an environmental public hearing, official complaints to the environmental authorities, municipal decrees, and the popular consultation itself. Resistance has also included the use of non-institutional strategies such as road blockades, denying access to the farms, as well as, allegedly, damage to the seismic equipment. In order to analyse such staunch opposition, we have produced a narrative, based on fieldwork and archival research, concerning the events that led to the popular consultation. We have argued that the environmental movement in Cumaral managed to turn a diverse, and even contradictory, collective into a singular subject that could dialogue with the state and its corporate allies in order to reject its extractivist development path.

Through the study of Cumaral’s environmental movement we have explored the intricacies of direct democracy in development politics, thereby enriching the debates on popular consultations in Colombia that have mainly focused on the first popular consultation against goldmining in Piedras, Tolima. Our study of Cumaral’s popular consultation against the oil industry reveals at least three aspects of the environmental movement in its navigation of institutional mechanisms and corporate actors.

First, the popular consultation provided a peaceful resolution mechanism for people to participate in development decisions. The defence of water resources and local livelihoods was good enough reason for people to rally behind the popular consultation – in particular as this mechanism could provide a tangible outcome. More importantly, this mechanism gave the people the possibility of not only influencing the type of development intervention that was going to take place but to completely reject the industry. This is in contrast to what usually happens with other types of institutionalised mechanisms (i.e. public hearings, complaints, environmental impact assessments) that are only able to alter an extractive project.

Second, the environmental movement, supported by an extensive national network, managed to create a unified voice capable of expressing people’s discontent with the government’s policies of resource extraction. The remarkable results of the popular consultation, where 97.61% of the people voted against having the oil industry, showed that unlikely alliances were formed in order to rally against the oil industry. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the voice of the social movement does not necessarily reflect its diversity and can silence the voices of those at the bottom. For example, the discourses for the defence of water resources and traditional livelihoods may have overshadowed the rural workers’ struggle for better material conditions. In other words, while diverse actors may temporarily agree on a particular objective, it need not mean they share the same values or interests.

Third, the struggles over the environment are about people fighting to keep their livelihoods taken away from them – struggles against dispossession. Prior to the arrival of the oil industry Cumaral enjoyed a regime of accumulation of expanded production based on industrial agriculture of rice, oil palm and cattle, as well as smaller sectors of tourism and commerce. The state’s policies for the extraction of non-renewable resources in Colombia symbolically and materially dispossess the people who inhabit the places where there is potential to find oil and minerals. National policies make those resources available for accumulation by extractive industries through the dispossession of people’s lands in order to access underground common resources. This regime of accumulation can be understood to generate the amply diverse sector of the dispossessed, which in Cumaral combines a wide array of actors including the poorest agricultural workers and the richest man in the country.

The success in the popular consultation shows that collective action is possible in development politics and that resistance to dispossession can be done successfully through the state. While the popular consultation mobilised the entire local population, showing that they disagreed with the government’s extractivist agenda, harnessing such social forces for structural change will require more than a popular consultation. Yet this, we hope, is a first step towards rethinking of the way oil production is done (i.e. technologies employed), how the benefits and burdens are distributed (i.e. present and future generations), who extracts the resource (i.e. ownership, role of workers), for whom it is extracted (i.e. local sovereignty), and perhaps most importantly, how and when people get to participate in the decisions that affect them.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the research participants and activists for taking part in this study. We would like to thank Astrid Ulloa, Ingrid Díaz, Ángela Castillo Ardila, Danute Pérez, Anja Frank, Florian Kühn, and Philip Lavender, as well as the reviewers for their thoughtful comments. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 838371.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicolás Acosta García

Nicolás Acosta García is a cultural anthropologist. His research focuses on the political ecology of development, ecotourism and biodiversity conservation on local, Afrodescendant and indigenous peoples. He received his doctorate from the University of Oulu, Finland, and currently works in sustainability in the private sector.

Fernando López Vega

Fernando López Vega is a PhD student in Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. He holds a Master's in Geography (Summa cum Laude) and Bachelor's in Anthropology from Universidad Nacional de Colombia. His research spans extractivism, territorialization, education, work, and social mobilization. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Rulings T-455 of 2016 and Auto 053 of 2017.

2 See e.g., Dietz (Citation2018), Garcés Villamil and Rapalino Bautista (Citation2016), McNeish (Citation2017).

3 Agencia Nacional de Hidrocarburos (ANH).

4 Law 685 of 2001.

5 Autoridad Nacional de Licencias Ambientales (ANLA).

6 ANH personal communication Dec 1st 2021.

7 File 4120–E1–3620 of January 28th, 2013.

8 See Decree 330 of 2007.

9 File No. 5790 of 14.03.2013.

10 ANH personal communication Dec 1st 2021.

11 ANH communication registry No. 20174010177152.

12 Law 134 of 1994 and Law 1757 of 2015.

13 ANH communication registry No. 20146240072222.

14 Constitutional Court of Colombia ruling SU-095 of 2018.

15 See Acosta García’s (Citation2022, 4) discussion on the polysemy of ‘the people’ in the context of popular consultations in Colombia.

References

- Acosta García, N. 2022. “Can Direct Democracy Deliver an Alternative to Extractivism? An Essay on Popular Consultations.” Political Geography 98: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102715.

- Acosta García, N., and N. Fold. 2022. “The Coloniality of Power on the Green Frontier: Commodities and Violent Territorialisation in Colombia’s Amazon.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 128: 192–201. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.11.025.

- Alcaldía de Cumaral. 2016. Decreto 58 de 2016 “Por Medio del Cual se da Apertura al Proceso de Convocatoria de una Consulta Popular. Cumaral.

- Alcaldía de Medina. 2016. Decreto 072 de 2016. Medina, Colombia, No. 072.

- ANH. 2022. “Producción Mensual de Hidrocarburos.” https://www.anh.gov.co/estadisticas-del-sector/sistemas-integrados-operaciones/estadísticas-producción [Accessed 16 Feb 2022].

- ANLA. 2013. Resolución 0823 del 2013. Bogotá: Autoridad Nacional de Licencias Ambientales.

- Badillo Mendoza, M. E., and C. Marta-Lazo. 2019. “Ciberciudadanía a Través de Twitter: Caso Gran Marcha Carnaval y Consultas Populares Contra la Minería en La Colosa.” Cuadernos.Info 45: 145–162. doi:10.7764/cdi.45.1454.

- Barczak, M. 2001. “Representation By Consultation? The Rise of Direct Democracy in Latin America.” Latin American Politics and Society 43 (3): 37–59. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2001.tb00178.x.

- Bebbington, A. 2013. “Industrias Extractivas, Conflictos Socioambientales y Transformaciones Político-Económicas en la América LAtina.” In Industrias Extractivas. Conflicto Social y Dinámicas iNstitucionales en la Region Andina, edited by A. Bebbington, 25–58. Lima: iep, cepes y gpc.

- Bebbington, A., and J. Bury. 2013. Subterranean Struggles: New Dynamics of Mining, Oil and Gas in Latin America. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bebbington, A., D. Humphreys Bebbington, J. Bury, J. Lingan, J. P. Muñoz, and M. Scurrah. 2008. “Mining and Social Movements: Struggles Over Livelihood and Rural Territorial Development in the Andes.” World Development 36 (12): 2888–2905. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.11.016.

- Blom Hansen, T., and F. Stepputat. 2006. “Sovereignty Revisited.” Annual Review of Anthropology 35: 295–315. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123317.

- Bloomberg. 2013. “Pacific Rubiales Provides 2014 Outlook & Guidance and Operational Update: In 2014 Targeting 15 to 25% Production Growth, E&D.” https://www.bloomberg.com/press-releases/2013-12-18/pacific-rubiales-provides-2014-outlook-guidance-and-operational-update-in-2014-targeting-15-to-25-production-growth-e-d-iv0097nf [Accessed 16 Feb 2022].

- Bocanegra Acosta, H., and J. E. Carvajal Martínez. 2019. “Extractivismo, Derecho Y Conflicto Social En Colombia.” Revista Republicana 26: 143–169. doi:10.21017/Rev.Repub.2019.v26.a63.

- Borras, S.M.Jr., J. C. Franco, S. Gómez, C. Kay, and M. Spoor. 2012. “Land Grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (3–4): 845–872. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.679931.

- Brock, A. 2020. “‘Frack Off’: Towards an Anarchist Political Ecology Critique of Corporate and State Responses to Anti-Fracking Resistance in the UK.” Political Geography 82 (May): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102246.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sobre Dinámica Social. 2015. Comunidades de Páramo: Ordenamiento Territorial y Gobernanza Para Armonizar Producción, Conservación y Provisión de Servicios Ecosistémicos Complejo de Páramos Chingaza. Bogota: Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt.

- Corte Constitucional de Colombia. 2018. SU095-18.

- Dietz, K. 2018. “Consultas Populares Mineras en Colombia: Condiciones de su Realización y Significados Políticos. El Caso de La Colosa.” Colombia Internacional 93: 93–117. doi:10.7440/colombiaint93.2018.04.

- DNP. 2022. “Terridata.” https://terridata.dnp.gov.co/index-app.html#/descargas [Accessed 23 Feb 2022].

- Faguet, J. P., F. Sánchez, and M. J. Villaveces. 2020. “The Perversion of Public Land Distribution by Landed Elites: Power, Inequality and Development in Colombia.” World Development 136: 1–23. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105036.

- Garcés Villamil, MÁ, and W. G. Rapalino Bautista. 2016. “La Consulta Popular Como Mecanismo de Participación Ciudadana Para Evitar Actividades Mineras.” Justicia Juris 11 (1): 52–62. doi:10.15665/rj.v11i1.617.

- García Gutiérrez, E., and S. X. Pulido Castro. 1999. Pobreza y desarrollo rural en Cumaral. Cumaral.

- Graef, D. J. 2013. “Negotiating Environmental Sovereignty in Costa Rica.” Development and Change 44 (2): 285–307. doi:10.1111/dech.12011.

- Gudynas, E. 2019. “Value, Growth, Development: South American Lessons for a New Ecopolitics.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 30 (2): 234–243. doi:10.1080/10455752.2017.1372502.

- Harvey, D. 2005. Spaces of Neoliberalization: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development. München: Hettner-Lecture 2004. Franz Steiner Verlag 2005.

- Hilson, G. 2012. “Corporate Social Responsibility in the Extractive Industries: Experiences from Developing Countries.” Resources Policy 37 (2): 131–137. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.01.002.

- Holloway, J. 2010. Crack Capitalism. London: Pluto Press.

- La Republica. 2018. En 2017 se realizaron 7 consultas populares y hay 54 pendientes. https://www.larepublica.co/especiales/minas-y-energia/en-2017-se-realizaron-7-consultas-populares-y-hay-54-pendientes-2613185.

- Las2orillas. 2022. “Las 30 mil hectáreas de Sarmiento Angulo en los Llanos Orientales.” https://www.las2orillas.co/las-30-mil-hectareas-de-sarmiento-angulo-en-los-llanos-orientales/ [Accessed 23 Feb 2022].

- Le Billon, P., and P. Lujala. 2020. “Environmental and Land Defenders: Global Patterns and Determinants of Repression.” Global Environmental Change 65 (February): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102163.

- Le Billon, P., M. C. Roa-García, and A. R. López-Granada. 2020. “Territorial Peace and Gold Mining in Colombia: Local Peacebuilding, Bottom-up Development and the Defence of Territories.” Conflict, Security & Development 20 (3): 303–333. doi:10.1080/14678802.2020.1741937.

- Leonardi, E. 2019. “Bringing Class Analysis Back in: Assessing the Transformation of the Value-Nature Nexus to Strengthen the Connection Between Degrowth and Environmental Justice.” Ecological Economics 156: 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.09.012.

- Li, T. M. 2017. “After Development: Surplus Population and the Politics of Entitlement.” Development and Change 48 (6): 1247–1261. doi:10.1111/dech.12344.

- López y Rivas, G. 2011. “Autonomías Indígenas, Poder y Transformaciones Sociales en México.” In: Pensar las Autonomías Alternativas de Emancipación al Capital y el Estado. México: Bajo Tierra, 103–15.

- Martinez-Alier, J. 2014. “The Environmentalism of the Poor.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 54: 239–241. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.019.

- McNeish, J. A. 2017. “A Vote to Derail Extraction: Popular Consultation and Resource Sovereignty in Tolima, Colombia.” Third World Quarterly 38 (5): 1128–1145. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1283980.

- Mitchell, T. 2009. “Carbon Democracy.” Economy and Society 38 (3): 399–432. doi:10.1080/03085140903020598.

- O’Connor, D., and J. P. B. Montoya. 2010. “Neoliberal Transformation in Colombia’s Goldfields: Development Strategy or Capitalist Imperialism?” Labour, Capital and Society 43 (2): 85–118. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43158379.

- Ojeda, D., J. Petzl, C. Quiroga, A. C. Rodríguez, and J. G. Rojas. 2015. “Paisajes del Despojo Cotidiano: Acaparamiento de Tierra y Agua en Montes de María, Colombia.” Revista de Estudios Sociales 2015(54): 107–119. doi:10.7440/res54.2015.08.

- Otero-Cortés, A. 2019. El Mercado Laboral Rural en Colombia, 2010-2019. Bogotá: Banco de la República, Centro de Estudios Económicos Regionales (CEER).

- Pacific Exploration and Production Corporation. 2016. Amended and Restated Annual Information Form.

- Prensa Libre, Casanare. 2011. “Sismica en Restrepo y Cumaral para buscar petróleo.” https://prensalibrecasanare.com/meta/2080-snsmica-en-restrepo-y-cumaral-para-buscar-petruleo.html [Accessed 16 Feb 2022].

- Procuraduría. 2012. “Procurador Alejandro Ordóñez Maldonado Adopta Medidas de Control Para Jornada de Consultas de Partidos y Movimientos Políticos.” Boletín 1020. https://www.procuraduria.gov.co/portal/Procurador-Alejandro_Ordonez_Maldonado_adopta_medidas_de_control_para_jornada_de_consultas_de_partidos_y_movimientos_politicos.news [Accessed 22 Feb 2022].

- Rabello, R. C. C., K. Nairn, and V. Anderson. 2019. “Working Within/Against Institutional Expectations: Exploring Recommendations for Social Investment in the Oil and Gas Sector.” The Extractive Industries and Society 6 (1): 103–109. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2018.06.007.

- Rasch, E. D. 2012. “Transformations in Citizenship: Local Resistance Against Mining Projects in Huehuetenango (Guatemala).” Journal of Developing Societies 28 (2): 159–184. doi:10.1177/0169796X12448756.

- Rasmussen, M. B., and C. Lund. 2018. “Reconfiguring Frontier Spaces: The Territorialization of Resource Control.” World Development 101: 388–399. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.018.

- Rausch, J. M. 2009. “Petroleum and the Transformation of the Llanos Frontier in Colombia: 1980 to the Present.” The Latin Americanist 53 (1): 113–136. doi:10.1111/j.1557-203X.2009.01011.x.

- Rinaldi, P., M. C. Roa-García, and S. Brown. 2021. “Producing Energy, Depleting Water: The Energy Sector as a Driver of Seasonal Water Scarcity in an Extractive Frontier of the Upper Orinoco Watershed, Colombia.” Water International 46 (5): 723–743. doi:10.1080/02508060.2021.1955327.

- Roa-García, M. C. 2017. “Environmental Democratization and Water Justice in Extractive Frontiers of Colombia.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 85 (July 2016): 58–71. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.07.014.

- Rubbers, B. 2020. “Mining Boom, Labour Market Segmentation and Social Inequality in the Congolese Copperbelt.” Development and Change 51 (6): 1555–1578. doi:10.1111/dech.12531.

- Sánchez Plaza, F. A. 2016. Análisis de la Sostenibilidad de la Cadena Productiva de Biodiesel en el Departamento del Meta. Bogota.: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Sassen, S. 2010. “A Savage Sorting of Winners and Losers: Contemporary Versions of Primitive Accumulation.” Globalizations 7 (1–2): 23–50. doi:10.1080/14747731003593091.

- Schuurman, F. J. 1993. “Modernity, Post-Modernity and the New Social Movements.” In Beyond the Impasse: New Directions in Development Theory, edited by F. J. Schuurman, 187–206. London: Zed Books.

- Semana. 2017. “Artistas se unen al ‘No’ en la consulta de Cumaral.” https://www.semana.com/medio-ambiente/multimedia/cumaral-y-el-no-reciben-el-apoyo-de-monsieur-perine-chocquibtown/37791/ [Accessed 21 Feb 2022].

- Servicio Público de Empleo. 2016a. “Detalle de la Oferta Capataz de REgistro.” https://personas.serviciodeempleo.gov.co/detalle_oferta.aspx?sede_id = 374177&proceso_id = 151686&dep_id = 50 [Accessed 21 Feb 2022].

- Servicio Público de Empleo. 2016b. “Detalle de la Oferta Asistente de Recursos Humanos.” https://personas.serviciodeempleo.gov.co/detalle_oferta.aspx?sede_id = 374177&proceso_id = 151685&dep_id = 50 [Accessed 21 Feb 2022].

- Talwani, M., and W. Kessinger. 2003. “Exploration Geophysics.” In Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, 3rd ed., edited by R. A. Meyers, 709–126. Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B0-12-227410-5/00238-6.

- Ulloa, A., and S. Coronado. 2016. Extractivismos y Postconflicto en Colombia: Retos Para la paz Territorial. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Vélez-Torres, I. 2012. “Water Grabbing in the Cauca Basin: The Capitalist Exploitation of Water and Dispossession of Afro-Descendant Communities.” Water Alternatives 5 (2): 431–449. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/volume5/v5issue2/178-a5-2-14/file.

- Vélez-Torres, I. 2014. “Governmental Extractivism in Colombia: Legislation, Securitization and the Local Settings of Mining Control.” Political Geography 38: 68–78. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.11.008.

- Veltmeyer, H. 2019. “Resistance, Class Struggle and Social Movements in Latin America: Contemporary Dynamics.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (6): 1264–1285. doi:10.1080/03066150.2018.1493458.

- Verweijen, J., and A. Dunlap. 2021. “The Evolving Techniques of the Social Engineering of Extraction: Introducing Political (re)Actions ‘from Above’ in Large-Scale Mining and Energy Projects.” Political Geography 88 (1): e1–e8. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102342.

- Villarraga Sarmiento, Á. 2014. Nuevos Escenarios de Conflicto Armado y Violencia. Panorama Posacuerdoscon AUC - Región Caribe, Antioquia y Chocó. Bogotá: Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica CNMH.

- Walter, M., and L. Urkidi. 2017. “Community Mining Consultations in Latin America (2002–2012): The Contested Emergence of a Hybrid Institution for Participation.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 84: 265–279. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.09.007.

- Wolfson, T., and P. N. Funke. 2018. ““The History of all Hitherto Existing Society:” Class Struggle and the Current Wave of Resistance.” tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 16 (2): 577–587. doi:10.31269/triplec.v16i2.1008.