ABSTRACT

This paper explores the intersections between two phenomena that have shaped eastern Kachin State in Myanmar’s northern borderlands with China since the late 1980s: the transformation of once-remote spaces into resource frontiers shaped by overlapping and cumulative forms of export-oriented resource extraction, and the upsurge of opium cultivation and drug use. Through the analytic of extractivism, we examine how the modalities surrounding logging and plantations in the Myanmar-China borderlands offer critical insights into how drugs have become entrenched in the region’s political economy and the everyday lives of people ‘living with’ the destruction, violence and insecurity wrought by extractive development.

1. Introduction

Since the late 1980s, Myanmar’s borderlands with China have been important frontiers for logging, mining, and agribusiness. For much of the post-colonial period, widespread armed conflict and poor infrastructure had limited large-scale resource extraction. Furthermore, memories of the exploitation, instability and social tensions wrought by the country’s incorporation into the global economy under colonial rule had evoked a powerful economic nationalism amongst military-state ruling elites defined by firm state control over the economy, and a rejection of foreign investment and global economic integration (Hlaing Citation2003).

However, faced with a major economic crisis and determined to stabilise the economy after the widespread pro-democracy protests in 1988, Myanmar’s military rulers shifted economic strategy and came to view large-scale resource concessions and border trade as the most expedient ways to improve state finances. This strategy was aided by a series of ceasefires in the late 1980s and early 1990s between the Myanmar government and various armed organisations that controlled territory along the China border. Although these ceasefires did not address longstanding political grievances, they created a fragile stability that enabled new flows of capital into resource rich frontiers (Meehan Citation2011; Oo and Min Citation2007; Woods Citation2011a).

The growing demand for resources was driven primarily by China’s rapid economic growth and its emergence as the leading manufacturing hub of the global economy, as well as high levels of growth across the ASEAN region. For example, since 1990 Myanmar has had one of the highest deforestation rates in the world, and rampant logging has fuelled China’s wood-processing industry that supplies paper, construction materials, and high-end furniture to global markets (FAO Citation2010; FAO Citation2016). Myanmar’s borderlands with China are one of the world’s largest sources of jade, tin and rare earths – exerting a strong influence over global prices and supply chains – as well as a source of gold, amber and coal. Fertile farmland close to the China border has also become an important land frontier, primarily for Chinese agribusinesses.

Alongside these rapid changes, Myanmar’s borderlands with China have remained a key hub in the global illegal drug trade. Myanmar remains the world’s second largest producer of illicit opium in the world (after Afghanistan) and has become the epicentre of methamphetamine production in Asia, producing billions of pills each year. Increasing levels of drug use and drug harms have also become a major cause of concern and social tensions within Myanmar’s borderlands (Dan et al. Citation2021; Drugs and (Dis)order Citation2020; Meehan et al. Citation2022).

The interconnections between the flourishing drug trade and the increasing integration of Myanmar’s resource-rich borderlands into the regional and global economy questions the dominant reflex surrounding debates on illegal drugs and development that characterises drug production as rooted in the marginality, armed conflicts and poverty of remote regions that have been ‘left out’ of development processes, and claims that integration into states and markets will be an effective antidote. To account for rising levels of drug production and drug use, this paper moves beyond an analytic of remoteness and marginality to focus instead on how drugs have become embedded in the processes of ‘exclusionary integration’ that underpin how Myanmar’s borderlands are connected into national, regional, and global political economies.

To develop this argument, we engage with recent work on extractivism (Chagnon et al. Citation2022; Gudynas Citation2013; McKay Citation2017; Ye et al. Citation2020) and apply this concept to Myanmar’s borderlands. Extractivism denotes a particular pattern of ‘development’ whereby the gains from large-scale resource extraction are privatised and transferred elsewhere, while the costs – environmental degradation, dispossession, violence – are socialised and shouldered by local places and populations. Extractivism warns against neo-classical theories of economic convergence; instead, it highlights how spatially uneven development is functional to capitalism. By developing an analytical framework that integrates extractivism and drugs, this paper has two core aims. First, it explores how studying illegal drug economies can offer new insights into the workings of extractivism and the ways in which people ‘live with’ violent resource frontiers (Kikon Citation2019; Sarma, Faxon, and Roberts Citation2023). Second, it reveals how the logics of extractivism can reinvigorate longstanding local drug economies by generating new drivers of drug production and drug use.

These issues are explored through a detailed case study exploring the relationships between drugs and extractive development in eastern Kachin State, centring on Waingmaw and Chipwe townships. This region has experienced cumulative waves of extractivism since the late 1980s. During the 1990s and 2000s, a logging boom transformed this border region, resulting in vast levels of deforestation, extensive road building, and significant changes to the local political economy. The logging business strengthened political and business ties between Chinese capital, Myanmar military-state elites, and non-state armed organisations along the border. Since the late 2000s, a new wave of extractivism – this time large-scale Chinese-funded banana plantations – swept across lowland areas of Waingmaw and neighbouring townships. The banana boom led to the conversion of vast amounts of farmland and forest that had sustained smallholder agriculture into monoculture plantations. Alongside the social and political-economic transformations wrought by logging and banana plantations in eastern Kachin State, and the environmental devastation and worsening livelihood insecurity that they have left in their wake, this region has seen a prolonged rise in opium cultivation and drug use. Opium cultivation in this area, has more than quadrupled since the 2000s and accounts for more than 80% of all opium cultivated in Kachin State (KIO Citation2019; UNODC Citation2022). Rising drug use and drug-related harms, have become a major concern amongst local populations and has been particularly associated in this area with extractive development.

The rest of the paper proceeds through the following sections. Following a brief overview of the methods and data that underpins this research, we develop the paper’s conceptual orientation, which aims to bridge the scholarly disconnect between drugs and processes of extractive development by considering how drugs become embedded in the ‘assemblages of extractivism’ (Hernandez and Newell Citation2022) that come to organise large-scale resource extraction. The rest of the paper then explores how opium cultivation and drug use have become embedded in successive and interconnected waves of extractivism in eastern Kachin State. We set out to show how the linkages between local drug economies, logging, and banana plantations are embedded within a wider assemblage of forces shaped by local histories of armed conflict and migration, shifting power structures and border regimes under ceasefire arrangements, and processes of market liberalisation in China and Myanmar.

2. Methods and data

This paper reflects on more than a decade of research by both authors and draws particularly on an extensive set of interviews carried out in Kachin State between 2018 and 2020 as part of a four-year research programme, entitled Drugs and (Dis)order.Footnote1 A team of researchers at Kachinland Research Centre (KRC) conducted a large scoping study on drug issues in 2018, encompassing more than three hundred interviews across Kachin State and northern Shan State. The connections between drugs and resource extraction emerged as a dominant theme and further rounds of fieldwork in 2019 and 2020 generated targeted research on this issue through a further three hundred in-depth interviews and life story interviews. In eastern Kachin State, the KRC research team drew upon kinship and religious networks to conduct interviews across Waingmaw and Chipwe townships. In Chipwe, data collection involved more than sixty interviews, mostly in Chipwe and Pangwa towns, with local farmers (poppy and non-poppy farmers), pastors, people who use drugs, civil society organisations, those who had worked in the logging sector, current and retired government officers, township and village administrators, members and former members of the New Democratic Army-Kachin (NDA-K) – the main local militia governing the area – as well as local historians and researchers. Across Waingmaw township, the team conducted almost fifty interviews in Waingmaw town, Sadung, Kanpaiti and in towns and villages along the main roads. These interviews encompassed farmers, labourers, church and youth groups, local administrators, Myanmar government officials, and representatives of various armed organisations, including the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO). Interviews were conducted in Jinghpaw or Burmese and involved men and women aged between twenty and eighty years old. Most interviews were with Jinghpaw, Lhaovo and Lachid populations, although interviews were also conducted with Lisu and Burmese respondents. All interviews were recorded, and following transcription and translation into English, a series of online and in-person workshops involving the authors, the KRC fieldwork team and other members of the research project, generated the analysis that underpins the paper.Footnote2 All datasets generated through the Drugs and (Dis)order programme have been archived in the UK Data Service, where further details are provided regarding coverage and methodology. The research for this paper pre-dates the February 2021 military coup in Myanmar and thus focuses on the relationship between drugs and extractive development in the period since the early 1990s up to 2020.

3. Drugs and extractivism

Conflict-affected borderlands are important hubs in the global illegal drug economy. They are major sites of drug production and refining that provide the starting point for global trafficking networks. In many cases, these drug-affected borderlands have a long history of political and economic marginalisation, and armed conflicts have been both a cause and an effect of this marginalisation. Longstanding linkages between conflict, drugs, and economic marginality have created a powerful narrative claiming that integrating the margins and channelling investment into them – ‘turning battlefields into marketplaces’ (Dwyer Citation2011; Hirsch Citation2009) – will dismantle illegal drug economies (UNDP Citation2001; UNODC Citation2010). However, these narratives struggle to account for contexts like Myanmar’s borderlands where drugs remain deeply entrenched even amidst their growing integration into the global economy. Addressing this blind spot, we argue that an understanding of the extractivist modalities through which Myanmar’s borderlands have been integrated into the global economy can offer important insights into why drugs remain embedded in these spaces.

3.1. Defining extractivism

Extractivism denotes a distinct form of large-scale resource extraction underpinned by a ‘violent logic of taking resources without reciprocity, without stewardship’ (Durante, Kröger, and LaFleur Citation2021). Resources are extracted and exported with little or no processing locally, creating ‘enclave economies’ that generate few linkages to, or benefits for, the local economy (Acosta Citation2013; Gudynas Citation2013; Svampa Citation2013). It is an inherently parasitic or ‘draining’ form of value capture (Ye et al. Citation2020): vast wealth generated by extractive capital is channelled elsewhere, while ‘simultaneously eroding the very material and ecological base from which it depends’ (Veltmeyer and Ezquerro-Cañete Citation2023) and leaving devastating and often irreversible environmental destruction and damage to local livelihoods and ways of life in its wake (Shapiro and McNeish Citation2021; Watts Citation2021).

Whilst extractivism has been most commonly been applied to large-scale mining and logging, this concept has been increasingly used as a framework to analyse export-oriented plantation agriculture. The literature on ‘agrarian extractivism’ challenges dominant discourses that claim current modes of capitalist agriculture can be a driver for poverty alleviation, food security, and employment (McKay Citation2017; McKay, Fradejas, and Ezquerro-Cañete Citation2021; Perreault Citation2018; Petras and Veltmeyer Citation2014; Svampa Citation2013; Veltmeyer and Ezquerro-Cañete Citation2023). Instead, it draws attention to the extractive logics that underpin large-scale mono-crop farming in terms of its lack of value-added processes, sectoral linkages, or employment creation, and the ‘environmental violence and toxic dispossession’ that is hard-wired into it (Veltmeyer and Ezquerro-Cañete Citation2023).

Extractivism unfolds through moments of rupture that profoundly re-shape societies. The configuration of ‘extractivist societies’ is shaped by the dual processes of frontier making and territorialisation, which entail the often-violent dissolution of existing social orders and the embedding of new forms of authority and territorial administration, that fundamentally re-configure land, labour and livelihoods (Rasmussen and Lund Citation2018, 388). Extractivism thus generates ‘dramatic and multi-dimensional shifts that have a catalytic role in society’ (Mahanty Citation2018) by re-shaping social relations, systems of authority, cultures, and everyday life.

The logics and modalities of extractivism outlined in the wider literature resonate strongly with the dynamics shaping resource frontiers in the Myanmar-China over the past three decades. This region has experienced cumulative and overlapping extractive development which have wrought major environmental damage and disruptive social change. Land use has been transformed by the often-violent concentration of land ownership, the depletion of the commons, and the destruction of customary land rights. For the vast majority, extractivism has resulted in increasing poverty and precarity.

The ways in which overarching extractivist logics hold together and become embedded in particular places, and the impacts and outcomes they generate, are always highly contingent and context specific. As Soto Hernandez and Newell (Citation2022) emphasise, this requires comprehending ‘the ways in which local sites and struggles are related to and embedded within broader structures of power, without reducing what is historically, socially and culturally unique about those sites to abstract global actors and processes’. Addressing this challenge, they emphasise the importance of disentangling the ‘assemblages of extractivism’ at work by addressing the heterogenous forces that coalesce across different sites and scales to shape how extractive development is materialised, institutionalised and discursively produced (Hernandez and Newell Citation2022).

Drawing upon this framework, this paper advances a socio-spatial analysis of how opium cultivation and drug use have become embedded in the way that extractive regimes have been assembled in northern Myanmar. It incorporates a focus on how the distinct materiality and ecologies of different commodities – in this case timber, banana, and opium – shape the way that extractivist regimes have been assembled, the impacts they have, and the responses they evoke. In terms of how extractive regimes are institutionalised in conflict-affected and politically fragmented regions like northern Myanmar, this paper draws specific attention to the informal systems of brokerage and deal-making between private capital, state authorities, and powerful non-state armed authorities that are required to open up resource frontiers, secure territory and embed extractivist modalities, and the insights this provides into why illicit activities can become embedded in the DNA of extractive development. The paper also draws attention to how particular framings of drug issues become important to how violent and destructive forms of extractivism are legitimised and discursively produced as developmental. These narratives obscure how extractivism can reinvigorate drug economies by generating new drivers of drug production and drug use. Challenging such narratives requires confronting the power relations surrounding knowledge production and whose knowledge counts. The space given in this paper to the testimonies of those living amidst the ruins wrought by extractivism in eastern Kachin State is an attempt to challenge the knowledge hierarchies that have enabled state officials, private companies, and borderland armed authorities to disingenuously claim that logging and plantations have served to alleviate poverty and tackle the drug economies in eastern Kachin State.

3.2. Assemblages of extractivism in the Myanmar-China borderlands

China’s rapid economic development since the 1980s has been a central dynamic in shaping assemblages of extractivism in northern Myanmar. Most resource-seeking extractive capital originates from China and is driven by efforts to secure cheap resources for the country’s industrial and manufacturing sectors, access farmland to mitigate food insecurity, satisfy rising levels of domestic consumption, and absorb surplus capital. Yet, ‘China’ comprises many different actors, interests, policies, and processes (Dean Citation2020; Dean, Sarma, and Rippa Citation2022; Woods Citation2016b). As Jones and Hameiri (Citation2021) show, processes of state transformation within China have led to ‘the fragmentation, decentralisation and internationalisation’ of party-state apparatuses and have enabled a growing number of actors to shape foreign economic policies and activities, often with little regulatory oversight (Jones and Hameiri Citation2021). Extractive development in northern Myanmar has been shaped by both major policy initiatives and large-scale infrastructure projects driven by Beijing, and the activities of local authorities in Yunnan and private companies that have wrestled significant autonomy over cross-border trade and investment, often without Beijing’s awareness, oversight or permission and oftentimes contravening Chinese laws and regulations (Baird and Li Citation2017; Hameiri, Jones and Zou Citation2019; Jones and Hameiri Citation2021, 137).

Extractivist assemblages in northern Myanmar have also been profoundly shaped by how Chinese capital intersects with longstanding and unresolved armed conflicts and state-building aspirations held by both the country’s military-state and an array of ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) (Htung Citation2018; Ong Citation2023; Sadan Citation1994; Woods, 2011; Woods Citation2016a). Efforts by private companies to extract resources have become entangled in the region’s highly fragmented ‘armed sovereignties’ (Woods Citation2019), whereby access to resources requires navigating the mosaics of territorial control between the Myanmar Army EAOs, and army-backed militias and the diverse interests of these actors (Dan Citation2022; Meehan and Dan Citation2022). These actors have established their own relationships with Chinese capital and have institutionalised – to varying degrees – local systems of territorial administration that facilitate resource extraction. These dynamics reflects the fitful presence of the state and the capacity of armed actors – both those fighting against the state and those aligned with it – to pursue their own agendas (Meehan and Dan Citation2022).

Extractivist assemblages in the Myanmar-China borderlands have also been shaped by the wider agrarian crises and armed violence affecting rural populations across the country (Boutry and Allaverdian Citation2017; Prasse-Freeman Citation2022; Ra and Ju Citation2021). Farming households throught Myanmar have faced a worsening ‘reproduction squeeze’ (Bernstein Citation1979, 427–428) and increased debt and dispossession. These crises are rooted in several interlocking factors: the commodification of land through a series of land laws that fail to recognise customary land tenure systems and make smallholders vulnerable to land grabs (Kramer Citation2021); development strategies that promote agribusiness-led development and disadvantage smallholders (Bello Citation2018; Meehan Citation2021; Woods Citation2019); land grabs by the military and private companies even where farmers have legal documents (LIOH Citation2015; Ra and Ju Citation2021); the privatisation and enclosure of common land and forest that households have long relied on to graze animals and supplement diets (Prasse-Freeman Citation2022, 1475–1476); heavy competition from cheap imports following trade liberalisation (Meehan Citation2022); and changing systems of credit and debt management that have made it harder for households to borrow money and face greater risks of land forfeiture if they are unable to repay (Boutry and Allaverdian Citation2017).

Indicative of a wider phenomenon in the peripheries of the global neoliberal capitalism, the large legions of landless rural labourers produced by the dynamics sketched above have little prospect of absorption into the country’s underdeveloped industrial sector. Within Myanmar, the numbers of people on the move in search of work has been exacerbated by large-scale armed violence, notably the shocking state violence in Rakhine State against the country’s Rohingya population. Considering the costs and risks involved in crossing the country’s borders, the majority of those displaced by violence, dispossession and livelihood crises have migrated internally. In this context, extractive spaces in Myanmar-China borderlands have attracted large in-flows of migrant workers in search of land and work (Prasse-Freeman Citation2022). This has transformed the social composition of these regions and created vast pools of cheap labour.

Alongside the extensive literature on how extractivism has become embedded in Myanmar’s resource frontiers, a growing body of work has focused attention on everyday lived experiences in extraction zones (Sarma, Faxon, and Roberts Citation2023; Sarma, Rippa, and Dean Citation2023; Drugs & (Dis)Order Citation2020; Citation2022). This work reflects the importance, as Li (Citation2018) has argued, of exploring not only what is destroyed and taken away by extraction, but what comes after, in terms of the ‘actual forms of life’ that emerge. In an important contribution, Sarma, Faxon, and Roberts (Citation2023) explore the ways in which people ‘adapt, resist, comply, suffer and profit from resource frontiers’ in Myanmar. Drawing upon Dolly Kikon’s (Citation2019) work on coal and oil extractive spaces in Northeast India, their work emphasises how a focus on ‘living with’ resource frontiers can reveal how extractive assemblages are constantly being re-shaped by the ways in which people navigate the ‘contradictions and connections between survival and profit, dispossession and desire, disposability and surplus, and life and death that animate resource frontiers’ (Sarma, Faxon, and Roberts Citation2023).

3.3. Situating drugs in assemblages of extractivism

Amidst the rich body of literature on resource frontiers in the Myanmar-China borderlands, very briefly sketched out above, the relationship between extractivism and the region’s flourishing drug economy has received only limited scholarly attention. This is surprising considering that drug production and drug use have risen significantly alongside the societal transformations wrought by logging, mining and plantations.

Whilst aggregate levels of opium cultivation in Myanmar remain lower than the peak years of the early 1990s, this downward trend has been driven by bans on poppy cultivation enforced by several ceasefire armed organisations in specific territories along the China border in Shan State (Kramer Citation2007; Renard Citation2013). Outside of these areas, opium cultivation has grown markedly (KIO Citation2019; Meehan Citation2021; Meehan Citation2022; TNI Citation2014). For example, according to the UNODC, levels of cultivation have almost quadrupled across Kachin State between 2006 and 2020 from just over 1,000 hectares to more than 4,000 hectares (UNODC Citation2022), whilst a separate survey conducted by the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO Citation2019) – the largest ethnic armed organisation operating in Kachin State – reported much higher levels of opium cultivation of almost 7,000 hectares in 2018/19.

Furthermore, high levels of drug consumption and rising harms related to changing patterns of drug use – especially heroin injecting and long-term methamphetamine use – have become defining features of everyday life across northern Myanmar (Dan et al. Citation2021; Drugs and (Dis)order Citation2020; Citation2022; Oosterom, Pan Maran, and Wilson Citation2019; Brenner and Tazzioli Citation2022). Sites of extraction have been epicentres of drug use, whilst the impact of drug harms have spread far beyond these enclaves, creating significant burdens of care for those, predominantly women, tasked with supporting household members struggling with addiction (Sadan, Maran, and Dan 2021).

The tendency to separate out drug issues from studies of extraction is partly linked to the ethical and safety challenges of conducting field research on such a sensitive topic. It is also indicative of the way in which drugs continue to be primarily viewed through the lens of armed conflict and criminality. Consequently, most reporting on Myanmar’s drug trade has concentrated on the involvement of armed actors (both the Myanmar Army and non-state armed organisations) in the drug trade, the role drugs play in financing war economies, and the connections between the drug trade and transnational organised crime (Anderson Citation2019; Behera Citation2017; ICG Citation2019; Jonsson and Brennan Citation2014; Lim and Kim Citation2021; Luong Citation2022; Meehan Citation2011).

Our paper aims to address this disconnect. We ask: How have opium cultivation and drug use become embedded in the assemblages of extractivism surrounding large scale resource extraction in the Myanmar-China borderlands? We approach this question from two angles. First, we consider how extractivism generates new drivers of drug production and use that layer upon longstanding histories of drugs and conflict. Second, we consider how analysis of illegal drug economies can offer new insights into the ways that extractivism works and how people ‘live with’ violent resource frontiers.

We explore the extent to which opium has offered a bulwark against smallholder crises triggered by extractivism in eastern Kachin State. Poppy cultivation has long played a pivotal role in supporting the livelihoods of impoverished farmers across Shan State and Kachin State. Opium is a high-value commodity that can generate a decent profit, even from small plots of otherwise marginal and steep land, and with low input costs. Poppy has a short growing season of only 3–4 months and sustained global demand ensure relatively stable prices, which in turn have enabled farmers to access credit against the crop (Meehan Citation2021). As a value-dense commodity, it has been one of the few crops that can reliably cover the costs of transportation to/from inaccessible remote areas, and buyers will often travel to purchase opium directly from farmers. Existing literature shows how these characteristics have made opium cultivation an important coping strategy for rural populations living amidst armed conflict, allowing them to eke out a living in remote, upland areas, and generate sufficient income to cover food security and other basic needs even from as little as 0.25–0.5 hectares of poppy cultivation (Sai Lone and Cachia Citation2021; Meehan Citation2021; TNI Citation2021). Less well understood is the extent to which these characteristics may also enable opium cultivation to become a coping strategy amidst the crises caused by extractivism: large-scale land grabs, the depletion of the commons, and the lack of local economic linkages or employment creation that mean there are few viable ‘exit options’ for those who are dispossessed. This raises several key questions: can poppy cultivation provide a viable means for people to survive and ‘live with’ violent resource frontiers? To what extent? For whom? And with what effects? These questions guide the empirical analysis in the next section of intersections between logging, banana plantations and opium cultivation in Waingmaw township, eastern Kachin State.

Whilst this paper focuses primarily on opium cultivation, we also explore how drug use has become deeply embedded in the workings of extractivism. The association between drug use and extractive industries has a long history, both in Myanmar (Dan et al. Citation2021) and in other contexts (Trocki Citation2000, 90–100; Waetjen Citation2017). This is linked to both labour conditions and ‘risk environments’ that emerge around extraction sites (Rhodes Citation2002). Jobs are often physically demanding, entail long hours, and require workers to relocate to isolated areas with few social support networks. Alcohol and drug use have often been a means for workers to cope with the demands of these jobs, to deal with stress, and to establish new social bonds (Ennis and Finlayson Citation2015; Sincovich et al. Citation2018; World Bank Citation2015) Resource extraction often drives the growth of boomtowns that attract large inflows of people, predominantly young men, and in which significant amounts of cash circulate in the local economy through wage labour and the trade in mined goods. Boomtowns attract informal economies seeking to capitalise on higher levels of disposable income by servicing the needs of workers who are far from home, including food, sex, entertainment, alcohol, and drugs. Furthermore, the growth of boomtowns typically outpaces the extension of authority, regulation and service provision, meaning that there is little policing of the drug trade or support for these who experience drug harms. Extractivism, we argue, can intensify the links between drugs and extractive sectors through the pace and scale of extraction, the disregard for the labour it requires, and the draining of value from sites of production, which prevents investment in any kind of services to address drug harms.

4. Logging: the first wave of extractivism in eastern Kachin State

4.1. Opium, conflict dynamics and changing border regimes in eastern Kachin State

Opium cultivation in Kachin State is concentrated in a region close to the China border in Waingmaw township, centred around the border town of Kanpaiti and stretching to Sadung to the west and up to/across the township boundary line with Chipwe to the north in an area known locally as Tamu Hkung.Footnote3 The Kanpaiti-Sadung-Chipwe region accounts for more than 80% of opium cultivation in Kachin State, with an estimated 4,651 hectares recorded in 2018/2019 (KIO Citation2019, 19) ().

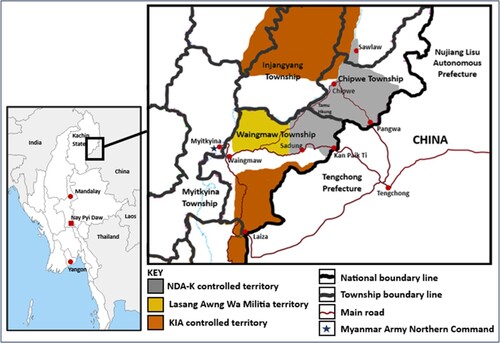

Figure 1. Eastern Kachin State. Areas of territorial control depicted on this map reflect the situation in the period under study in this article.

This region has a long history of small-scale poppy cultivation, primarily amongst Lachid, Lhaovo and Lisu populations who grew opium for personal use and small-scale trade with buyers from Sadung, Myitkyina and China. Levels of cultivation expanded in the 1960s in connection with the region’s growing insurgency. In 1960/61 the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO) was formed and grew rapidly following the 1962 military coup and the installation of a military dictatorship in the country under General Ne Win. Opium became an important source of finance for the KIO in eastern Kachin State where there were few other ways of generating revenue, as recounted by one elderly Chipwe denizen,

When forming new brigades, the KIO did not give the commander money, instead they provided opium … At that time opium could be used as a currency … The KIO collected taxes in opium if the villager could not pay in cash … So as long as you paid tax you could grow poppy, and then cultivation became widespread.

Although conflict receded after 1976 following a ceasefire between the KIO and the CPB, the violence had a devastating impact on local populations, many of whom migrated to escape the fighting. Remembering the fighting, one elder reflected:

It created a tremendous problem for local communities. The Communists came and laid landmines, the KIA also came and laid land mines, the government's army also came and laid landmines. The villagers did not even have a space to step on … I still remember within 8 months 122 villagers died of landmines … The villagers could no longer put up with the landmine issues so they migrated to Waingmaw and Myitkyina.

Conflict dynamics in this region changed dramatically in the late 1980s and early 1990s following the collapse of the CPB in 1989 after a series of heavy defeats to the Myanmar Army and growing internal tensions (Lintner Citation1990). The CPB fragmented into a series of successor splinter groups. Zakhung Ting Ying and Layauk Ze Lum formed a new organisation – the New Democratic Army-Kachin (NDA-K) – and agreed a ceasefire in 1989 with Myanmar’s military rulers. The ceasefire granted the NDA-K de facto control over much of the CPB’s old 101 War Zone, which became known as Kachin Special Region 1. In 1994, the KIO also reached a ceasefire with the Myanmar government, and levels of conflict across Kachin State receded (Sadan, Maran, and Dan Citation2021).

The ceasefires coincided with, and helped to facilitate, efforts on both sides of the border to expand border trade and resource extraction in Myanmar’s borderlands. China was the first country to officially recognise Myanmar’s new military junta – the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) – that had replaced General Ne Win in 1988 and brutally repressed the country’s pro-democracy protests. This was swiftly followed by a series of trade agreements between the two governments (Global Witness Citation2003, 80). These moves were part of a wider set of initiatives instigated by the Chinese government to stimulate economic development in the country’s land-locked interior provinces where rates of economic growth remained lower than the country’s rapidly developing coastal provinces. In the early 1990s, the Chinese government announced that policies of economic openness that had been granted to coastal regions through the 1980s would be extended to interior regions, allowing them to establish border trade ports with neighbouring countries (Rippa Citation2020, 91). These national-level policy shifts were quickly seized upon by Yunnan’s political and business elites (Meehan, Hla, and Phu Citation2021; Rippa Citation2020, 73; Summers Citation2013). Yunnan government authorities established various official border crossings at Houqiao in Tengchong Prefecture and at Pianma in Nujian Lisu Autonomous Prefecture, both of which bordered with NDA-K-controlled territory on the Myanmar side (Rippa Citation2020, 92; Woods Citation2011b). Various other small-scale border crossings opened as companies eyed the vast natural resources across the border, which decades of conflict and inaccessibility had left relatively unexploited.

Within Myanmar, military elites were desperate to secure new sources of revenue to stabilise the economy and generate funding plans to modernise and expand the military. Large-scale logging concessions granted by the Myanmar military to Thai businesses in 1989 had played a pivotal role in staving off the immediate financial crisis facing the SLORC and the government now looked to replicate this model in northern Myanmar (Bryant Citation1997, 178). Allowing ceasefire groups like the NDA-K and the KIO to grant resource concessions and administer border crossings also acted as form of ‘resource diplomacy’ aimed at stabilising the ceasefires. Amidst this changing border region, eastern Kachin State experienced a first wave of extractivism through the 1990s and 2000s in the form of rampant logging.

4.2. The logging boom in eastern Kachin State

By the 1990s, half of all remaining closed forest in mainland Southeast Asia was in Myanmar (Global Witness Citation2003, 29). Through the 1980s there had been some attempts by timber companies in Yunnan to access forests in northern Myanmar, and these efforts gathered pace through the 1990s amidst border liberalisation and declining levels of armed conflict under the ceasefires. Domestic reforms to China’s logging sector further transformed the cross-border timber trade and contributed to unprecedented levels of deforestation throughout northern Myanmar. These reforms were in response to serious floods that beset China in the late 1990s. In 1998, major flooding along the Yangtze River affected one-fifth of China’s population across 29 provinces, killing more than 3000 people, making 15 million homeless, destroying 5 million hectares of farmland and causing more than $20billion damage (Global Witness Citation2003, 83; UNOCHA Citation1998). The scale of the flooding was blamed on deforestation of upstream watersheds in Yunnan that had caused huge volumes of sediment to be deposited in the river. In response, the Chinese government implemented two pieces of legislation that had a major impact on the timber industry across China and especially in Yunnan: The National Forest Protection Programme (NFPP) which effectively banned logging in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River in Yunnan Province; and the Sloping Land Conversion Program (SLCP), which aimed to reforest denuded slopes by paying farmers subsidies to return cultivated lands steeper than 25 degrees to their original vegetation (Delang and Wang Citation2013). The NFPP was estimated to have led to 1.2 million job losses in the timber sector across China and more than 60,000 in Yunnan. It also came at a time when China’s domestic wood consumption and wood-processing industry experienced rapid growth (Sun, Wang, and Gu Citation2005). Imported timber became a way to plug the gap between demand and domestic supply, and in 1999 the Chinese government cut all import tariffs on roundwood and sawnwood to zero (Rippa Citation2020, 94). Between 1998 and 2001, the volume of log imports more than tripled to 16 million cubic metres (Global Witness Citation2003, 84). In Yunnan, the combination of border liberalisation and domestic logging reforms inspired a major boom in cross-border logging.

Logging took place throughout northern Myanmar – in territories controlled by the Myanmar Army, the KIO, and the NDA-K – and bore all the hallmarks of extractivism. Companies exported raw logs on a vast scale with no local value-added processing, leaving behind huge environmental destruction. Since 1990, Myanmar has had one of the highest deforestation rates in the world. By 2010, the FAO estimated that logging had removed 19% of Myanmar’s forests (FAO Citation2010; FAO Citation2016), with Kachin State experiencing the highest loss in forest area (Yang et al. Citation2019).

The scale and intensity of logging was particularly pronounced in NDA-K controlled territories considering their proximity to the China border and their accessibility via key border crossings. The NDA-K positioned itself as a key borderland broker granting concessions to Yunnan timber companies, facilitating access to vast forests under its control and managing relationship with the Myanmar military government. As one resident of Pangwa reflected on that time,

When they [the NDA-K] signed the ceasefire they started logging … Only those people who had been loyal to the NDA-K since the Communist Party period [got concessions] … I don't know how many acres but they would divide the mountain range on a map … Zahkung Ting Ying became very rich because he was based in Pangwa [a key border town] when he started. … He knew that he would have to pay money per tonne to the government, so he doubled the price. It became a win-win for the government and for him.

4.3. Drugs and logging

Chinese authorities, timber companies and the NDA-K presented logging as a force for development and poverty alleviation, and even as a way to tackle longstanding opium cultivation. By channelling investment into remote regions, they claimed logging generated economic growth and provided opportunities for local populations to draw them away from reliance on opium cultivation (Global Witness Citation2003, 57). In the words of the Deputy Director of Poppy Alternative Development Office in the Yunnan Department of Commerce, such investments generated ‘a benign cycle between drug control practice and economic development’ (UNODC Citation2008, 127). Logging companies also claimed to be well-placed to implement alternative development schemes in Myanmar and lobbied the Chinese government for funding.

These narratives presented Chinese companies that have made vast wealth from exploiting resources in upland borderland areas of Myanmar as operating in the interests of drug control and poverty alleviation. Official state narratives presented Yunnan enterprises as having ‘actively responded to the call of the Chinese Government to engage in aid and support programmes initiated by drug control committees.’ Despite ‘substantial investment risks and a long capital recovery,’ these companies were commended for having gone ‘without reservation to the harsh area beyond the border, overcame difficulties and constantly increased their investment.’ Even roads – the harbinger of deforestation and vast value capture by Yunnan companies – were reimagined as public welfare undertakings directed towards ‘where the alternative programme is located, with alternative development radiating outwards’ (UNODC Citation2008, 25–34).

Such claims represent important discursive elements of extractivist assemblages in northern Myanmar and became important in enabling provincial authorities and private companies to attract further state funding from counter-narcotics budgets, as shown below (Section 5.2). Yet, these claims were also highly disingenuous. Companies with longstanding connections to the drug trade used the logging industry to launder drug money. The most notorious example of this was Asia World Company, founded by Lo Hsing Han – whose involvement in the drug trade dated back to the 1960s (Gutierrez Citation2020; Meehan Citation2011). Asia World Company established close business ties with the NDA-K and obtained various logging concessions and road-building contracts.

Furthermore, very little money generated from logging was invested in the local economy or into financing service provision. Almost all timber was exported as raw logs for processing in China where it fuelled the province’s wood-processing industry and contributed to Yunnan’s rapid economic growth. Most companies employed labour from China – drawing upon workers laid off following domestic logging bans – rather than recruiting locally. Far from alleviating poverty, the way the sector operated meant that logging generated few local benefits but brought huge environmental destruction and adversely impacted the livelihoods of local populations who have long relied on forest products to supplement diets and income. As is typical of extractive development, the gains from logging were privatised, while the costs were socialised. As one long-term Sadung resident reflected,

In the past in Sadung area was heavily forested area, full of big woods. But since the ceasefire period started forests have been disappearing, and you saw drastic environmental degradation. Many Chinese came here for logging business. You see those roads; they were used for transporting logs. But now they are no longer in use … . During the peace era we see the process of our forests getting denuded … we see our environment getting destroyed … Our ancestral land got destroyed.

Zahkung Ting Ying from the NDA-K gave pines as an alternative crop. We planted what we were given, but we can’t sell because there is no price. We only get a price if the Chinese come to buy. But we do not know how to do finished products and so local growers got nothing. Some have even cut all their pines down … There is no responsibility from the government for us … We cannot rely on government support. The main reason [for growing poppy] is that if we did not grow opium, we would not be able to do any other business.

Some logging companies even part-paid wages in drugs – a practice that reflected and served to reinforce widespread drug use amongst loggers. In other cases, workers were still paid in cash, but companies sold drugs (and alcohol) to their workers, enabling these companies to recoup a significant proportion of their labour costs through the profit margins on these transactions. As more drugs flowed into the local area, drug use soon proliferated beyond the logging camps. As one elderly resident of Chipwe recounted,

When I settled down in Chipwe in 1973, I heard that there was opium available but I had never seen it with my own eyes. That time, I did not come across drug addicts. I had not heard about heroin and yaba [methamphetamines] in the area. After the ceasefire, Asia World Company came into the area, then road construction started, then the logging started in the area. The heroin started coming in when the area became more populated. Then the local youth started using different kinds of drugs. Many young people started shooting heroin. Many young people passed away because of drugs.

Far from dismantling the region’s longstanding opium economy, logging played an important role in further entrenching the importance of opium cultivation to the livelihoods of poor farmers in the Kanpaiti-Sadung-Chipwe region and driving new drug use habits. These foundations are significant in accounting for the steep rise in opium cultivation in this region since the late 2000s that accompanied a new wave of extractive development.

5. Banana plantations: the second wave of extractivism in eastern Kachin State

5.1. Land as the new frontier

By the late 2000s, a new wave of extraction hit eastern Kachin State – this time in the form of large-scale Chinese-funded banana plantations. The opening up of new land frontiers in eastern Kachin State was part of wider phenomenon whereby Chinese agribusinesses have sought to access farmland outside of China to capitalise on growing domestic markets created by rising levels of consumption, and in response to the shrinking availability of domestic arable land (Chen et al. Citation2019; Thomas Citation2013, 532). China accounts for around 20% of the world’s population but has less than 10% of the world’s arable land and under 6% of the world’s water resources (Grimsditch Citation2017, 18). Rapid urbanisation and industrialisation have created further pressures and accounted for the loss of more than 8 million hectares of arable land between 1997 and 2009. Years of intensive farms have exhausted soils in many areas leading to reduced yields, whilst the government has also had to manage growing ecological pressures. For example, the aforementioned Sloping Land Conversion Program (SLCP), which was introduced following the severe floods of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers in 1998, sought to convert more than 14 million hectares of cropland to forests through a strategy know as Grain for Green (Hyde, Belcher, and Xu Citation2003).

How to increase food production without disrupting rapid economic growth and social transformation has been a major challenge for the Chinese government (Thomas Citation2013, 532). The government’s 2011–2016 Five Year Plan – in which food security was given policy priority – outlined a twofold strategy to address this challenge. Domestically, the government set out plans to ensure that a minimum of 120 million hectares of arable land was ringfenced for food production. At the same time, the Chinese government incentivised companies to invest in agribusiness ventures abroad, and effectively ‘grafted its agricultural development policy onto its ‘going out’ strategy’, which had been initiated in 1999 to promote Chinese overseas investment (Thomas Citation2013, 532).

This strategy aligned with development ideologies pursued by several of China’s neighbours in Southeast Asia. In Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, national governments have pursued a vision of agricultural ‘modernisation’ predicated on a shift away from smallholder production to large-scale industrial agriculture and have sought foreign direct investment to reduce aid dependence (Baird Citation2011; Bello Citation2018; Grimsditch Citation2017; Kenney-Lazar and Mark Citation2021; Luo et al. Citation2011 Thomas Citation2013; Phonvisay and Manolom Citation2022).

In Myanmar, these policies were also inextricably linked to the military government’s counter-insurgency strategy. This strategy sought to use the allocation of large-scale land and resource concessions in contested territories as a mechanism to wrestle control away from opposition forces and establish a nexus of military-private sector power to underpin processes of military territorialisation (Ferguson Citation2014; Woods Citation2011a). Amidst the growing demand for land and resources, legal frameworks established by successive Myanmar governments over the previous three decades facilitated agribusiness investment by enabling large-scale land grabs (Mark Citation2016; San Thein et al. Citation2018). In 1991, the country’s military junta implemented the ‘Wasteland Law,’ which characterised all land without legal title – effectively including all customary and communal lands – as ‘wasteland’ and granted the government the right to then allocate large-scale land concessions to private companies, regardless of whether or not this land was being farmed (FSWG Citation2011; TNI Citation2012). This law was particularly devastating in borderlands populated by ethnic minorities where most land ownership was managed through customary institutions that were not recognised by the state.

This legal framework was further reinforced by a series of laws passed by the Thein Sein government (2011–2016) and the National League for Democracy (NLD) government (2016–2021). The 2012 Farmland Law established a market for land by allowing registered land to be bought, sold, and transferred. This was accompanied by the 2012 Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land Management Law (VFV Law), which allows the government to re-allocate all unregistered land. Again, this law provided no recognition of customary and communal land tenure. Nearly one-third of the country’s agricultural land was deemed to be VFV land, 75% in the country’s ethnic states (Ra and Ju Citation2021). In 2012–2013 alone Myanmar’s agricultural ministry granted 566,500 hectares of land concessions in Kachin State and 80,900 hectares in Shan State (LIFT Citation2019). A further amendment to the VFV Law in 2018 by the NLD government set a six-month deadline for people to register their land and introduced punishments for those who continued to farm unregistered land after this deadline. These laws meant that ‘overnight millions of people in the country were criminalised for living on their ancestral lands and practicing customary systems but without formal land titles from the government’ (Kramer Citation2021, 490). It is important to emphasise that whilst legal frameworks in Myanmar have facilitated large-scale land grabs, they have also provided scant protection for smallholders who do have a legal claim to their land. A 2015 report based on research in 62 townships across 13 of the country’s states and regions found that more than 40% of respondents who had lost land had legal documents issued by the government (LIOH Citation2015).

5.2. China’s Opium Substitution Programme: a major stimulus for agrarian extractivism

In the mid-2000s, Chinese agribusiness expansion into northern Myanmar received a major stimulus through China’s state-funded Opium Substitution Programme (OSP). Funded by the Chinese government and administered by the Yunnan Department of Commerce, the OSP offered Chinese agribusinesses various incentives – including import licenses and tax waivers – to invest in Laos and Myanmar.

Since the late 1980s, rising levels of drug use across China became an increasing cause for concern for the Chinese state. Efforts to strengthen the country’s domestic anti-drug laws were perceived to have limited effect considering continued large-scale opium cultivation and heroin production just across the country’s borders (Swanstrom Citation2006). Local authorities in Yunnan proved adept at leveraging these concerns to pursue a set of commercial interests aimed at dismantling import restrictions and tariffs on agricultural commodities produced abroad for Chinese markets. The Yunnan Department of Commerce framed the expansion of large-scale commercial agriculture into upland areas of neighbouring Myanmar and Laos as the most efficient mechanism to facilitate sustained economic growth and create new employment opportunities, thus drawing land and labour away from opium cultivation (Su Citation2015; TNI Citation2012).

This initiative gained a major impetus in 2006 when the State Council created the Opium Substitution Special Fund and tasked the Yunnan Department of Commerce to administer it. Annual funding was approximately 50 million yuan (c.$6.25 m) in the first five years of the scheme and this was expanded to 250 million yuan (c.38–$40 m) between 2011 and 2016 (Jones and Hameiri Citation2021, 139; Su Citation2015). This funding primarily financed a system of subsidies, import licences, and exemptions from import tariffs and VAT for Chinese agribusinesses (TNI 2012; Shi Citation2008; Su Citation2015). To be eligible for these benefits, the OSP stipulated that companies must undertake substantial ventures, defined in terms of capital invested and land area cultivated (Dwyer and Vongvisouk Citation2019; Jones and Hameiri Citation2021, 138). The centrepiece of the OSP was initially rubber cultivation, although the programme has also provided support for agribusiness ventures in a range of crops, maize, rice, and banana. By 2015, more than 200 Chinese companies had participated in the OSP and were responsible for agricultural plantations on more than 200,000 hectares of land in Myanmar and northern Laos, a figure that far surpasses the amount of land under poppy cultivation (Su Citation2015, 79).

In reality, tackling opium cultivation was not the primary concern for those who obtained OSP funding, and the programme was designed to allow large agribusiness corporations with strong political connections to capture most of the funding disbursed by Beijing (Jones and Hameiri Citation2021, 136; Shi Citation2008, 27–30; Lu Citation2017, 733). There is debate over how far the OSP provided the necessary impetus for Chinese companies to expand into northern Laos and Myanmar, or simply supported a process that was already under way. Either way, by channelling hundreds of millions of dollars to Chinese agribusinesses, the OSP has been instrumental in magnifying the speed and scale of cross-border agribusiness ventures into conflict areas of northern Myanmar.

5.3. Building on earlier rounds of extraction

The earlier logging boom also played an important role in opening up land frontiers in eastern Kachin State for Chinese agribusinesses. Logging cleared large swathes of land, some of which were then converted to agriculture. More importantly, as Rippa (Citation2020, 100) emphasises, the materiality of logging – its heft and the infrastructure it requires – had distinct political-economy effects. Logging provided the impetus and finance to improve road networks (Rippa Citation2020; Sarma, Rippa, and Dean Citation2023). Of particular note was the 200 km paved highway that opened in 2007 connecting Tengchong in Yunnan with the Kachin State capital, Myitkyina. The road, which crosses the border at Kanpaiti before going through Sadung and Waingmaw, halved travel time between Myitkyina and Tengchong (Zhou Citation2013). Myanmar Army militarisation went together with road building, strengthening military control across northern Waingmaw, and weakening KIA positions in this region. As well as connecting logging areas to the China border, these army-controlled roads also improved access to fertile lowland areas across Waingmaw and Myitkyina townships.

Logging also generated vast capital in search of new investment opportunities as forest reserves became depleted and more expensive to extract. For example, the Tengchong-based Jinxin Trade Company, which was one of Yunnan’s largest logging companies and operated major concessions in Kachin State (Global Witness Citation2003, 86), has since invested heavily in banana plantations in Waingmaw (see below). Logging played a further role in entrenching a political economy that was conducive to successive waves of large-scale extraction. Revenue-sharing arrangements between the military government and the NDA-K strengthened the elite bargains underpinning ceasefire arrangements, magnified the ‘benefits’ of stability, and reduced the risk of a return to large-scale armed conflict. Logging concessions also established business networks between the Myanmar military, local strongmen like Zakhung Ting Ying, and Chinese and Burmese investors. Through the 2000s, the NDA-K maintained good relationships with the Myanmar military government even as other ceasefires became increasingly fragile. In 2009, the NDA-K became the first ceasefire group to accept the Myanmar military government’s proposal to convert into a ‘Border-Guard Force’ (BGF). The BGF scheme was designed to limit the size of ceasefire armed groups and bring them under firmer Myanmar Army control. The NDA-K’s decision to accept BGF status ensured there was no return to war in this border area and allowed the NDA-K to reinforce its position as a key borderland broker for Chinese investors, capable of providing local security, access to resources, and government connections.

The NDA-K’s ability to maintain this brokerage position – accruing significant wealth in the process and avoiding the fate of various other militias that had been forcefully dismantled by the Myanmar Army – provided an attractive model for others, notably the Lasang Awng Wa militia. Following a power struggle within the KIO in 2004, its erstwhile Intelligence Chief, Lasang Awng Wa, defected with about 100 troops – fleeing initially to the NDA-K before then establishing his own militia with the backing of the NDA-K and the Myanmar Army. The Myanmar Army granted Lasang Awng Wa various business opportunities and licenses – logging concessions, gold mining, riverine sand extraction, and casinos. By the late 2000s, this militia controlled a sizeable territory adjacent to NDA-K territory and had also converted into a BGF.

By the late 2000s, regional, national and local dynamics had coalesced to transform eastern Kachin State into a major new land frontier. The pursuit by Chinese agribusiness investors for farmland, improved cross-border infrastructure – spearheaded by the earlier logging boom, the Myanmar government’s support for large-scale agribusiness, the financial stimulus provided by the OSP, and a local political economy predicated on well-established personal and business ties between powerful local militia, the Myanmar military, and Burmese and Chinese investors, laid the foundations for a new extractivist assemblage: the banana boom that swept across Waingmaw.

5.4. The banana boom

The banana boom in eastern Kachin State began in stealth. In the mid-2000s farmers in some parts of Waingmaw found themselves being offered attractive prices for land that had previously garnered little interest. For many cash-strapped households, the lump sums on offer proved irresistible. Yet, as it soon transpired, the land was far more valuable than they had supposed. Many of those early buyers were land speculators who had learnt ahead of time of the wave of Chinese capital that was about to transform Waingmaw. In barely more than a decade, Chinese agribusinesses converted large swathes of the township’s farmland into vast banana plantations. By 2019, plantations covered almost 60,000 hectares across Waingmaw, representing well over half of all the township’s available farmland (LSECNG Citation2019).Footnote4

Why bananas? The banana boom in northern Myanmar has been driven entirely by the sustained growth in demand within China, where per capita consumption of the fruit almost doubled between 2000 and 2019 from less than 4 kg per person to 7.71 kg per person, representing an increase in domestic demand from less than 5million metric tonnes to almost 11million metric tonnes per year (FAOSTAT Helgi Calculation Citation2020). Rising demand fuelled (and was in turn driven by) domestic production of highly marketable but disease-prone Cavendish varieties. Agribusiness investment in banana plantations within China spiked in the late 2000s, following a combination of sudden price rises – driven by supply shortages caused by the spread of the fungal disease Fusarium wilt (popularly known as ‘Panama Disease’) – and a search by investors for new investment opportunities following the 2007–2008 Global Financial Crisis that slowed growth in export-oriented sectors. The distinct ecology of bananas – especially their susceptibility to Fusarium wilt, which can stay in the soil for many years and devastate entire plantations – pushed agribusinesses to pursue a strategy of ‘shifting plantation agriculture’ to try to outpace the disease (Soluri Citation2005; cited in Thiers Citation2019). This led cultivation, which was initially concentrated in Hainan, Guangdong and Fujian provinces, to expand further into Guanxi and Yunnan provinces.

In 2014, banana production in China was severely hit by the Category 5 super typhoon Rammasun (‘thunder of God’), one of only three such typhoons ever to have been recorded in the South China Sea. The typhoon destroyed 80% of banana plantations in Hainan, Guangdong and Guangxi, driving a new cycle of price hikes and a new quest for land. This came at a time when trade with the Philippines – the largest banana importer to China – had already been restricted following disputes between the two countries over territorial rights in the South China Sea (Friis and Nielsen Citation2017).

The search for new land frontiers for banana plantations coincided with the expansion of the Opium Substitution Programme (OSP) and the sustained fall in global rubber prices after 2011. Agribusinesses that had used the OSP to finance rubber cultivation in northern Laos and Myanmar now sought to shift their capital into more lucrative ventures. Chinese-funded banana plantations first expanded into northern Laos (Wentworth et al. Citation2021). However, banana plantations proved more controversial than rubber (Lu Citation2021). This was because banana required the conversion of rice paddy on lowland irrigated plots – rather than upland areas of shifting cultivation and forest – and so impacted on provincial food security targets. The fact that Chinese companies had secured land for banana plantations through informal land lease arrangements with local landowners rather than via formal state channels had also raised concerns (Lu Citation2021). Authorities in Bokeo, Luang Namtha and Oudomxay provinces subsequently imposed bans on banana plantations (Grimsditch Citation2017, 55–56; Hayward et al. Citation2020, 17). This led to the exodus of many banana companies from northern Laos – and their arrival in eastern Kachin State.

5.5. Banana plantations in Waingmaw: Agrarian extractivism at work

Banana plantations in eastern Kachin state have borne all the classic hallmarks of agrarian extractivism. The sector is dominated by transnational agribusiness corporations operating large-scale, capital-intensive, export-oriented plantations that are socially and sectorally disarticulated from the local economy. Banana companies have appropriated vast natural and surplus value by draining the region’s ecological wealth and exploiting labour, and have left in their wake serious social and environmental destruction.

The most striking transformation wrought by the banana boom in Waingmaw has been the concentration of land ownership and the subsequent shift in land use from agro-biodiverse smallholder food and farming systems to monoculture plantations. Companies have secured vast land concessions stretching across thousands of hectares of prime fertile lowland close to main roads, which had previously sustained large numbers of smallholders. For example, Yunnan Jinxin Agricultural Company, part of the major Yunnan Jinxin conglomerate and a recipient of OSP funding, operates a 6,667-hectare plantation in Waingmaw (Fresh Plaza Citation2020; Hayward et al. Citation2020, 28). Since Chinese companies cannot officially rent or buy land in Myanmar, many plantations operate as joint ventures between Chinese investors and local businessmen with close ties to the Myanmar military and army-backed militia. For example, in Man Wein village tract in northern Waingmaw, a local company owned by NDA-K leader Zakhung Ting Ying’s son, U Aung Zaw, and backed by Chinese capital operates a banana plantation on more than 4,000 hectares. The plantation has dispossessed many smallholders, even encroaching into the heart of Man Wein village and taking over cemetery land (Chan Thar Citation2018; Hogan Citation2018).

Across southern and central Waingmaw, companies have also taken land from those who had been forced to flee their homes following renewed armed clashes between the Myanmar Army and the KIA. The government’s demand that the KIA convert itself into a BGF hastened the breakdown of the ceasefire in 2011 after seventeen years and renewed fighting led to more than 100,000 IDPs across Kachin State and northern Shan State (Sadan et al. 2016).

As documented in , companies have gained control of land through multiple different mechanisms. In many cases, households leased their land to companies in return for what seemed like attractive lump-sum payments, although few have since been able to find alternative sustainable livelihoods. also reveals the extra-economic forces of dispossession that have underpinned Waingmaw’s banana boom and the devastating impact this has had on local populations.

Table 1. Mechanisms through which banana companies have obtained land in Waingmaw Township.

There is no reliable data on the exact size of the banana industry in northern Myanmar. Practically the entire harvest is exported to China and official trade data at the Kanpaiti border crossing recorded exports of 733,494 tonnes with a value of almost $300 million in 2019/20, although these figures almost certainly capture only a portion of the trade (Hayward et al. Citation2020, 22). Indeed, in the same year, Yunnan Jinxin Agricultural Company alone claimed to have produced 350,000 tonnes (Fresh Plaza Citation2020), and some researchers estimate the annual value of the trade to be close to $600 million (Hayward et al. Citation2020, 22).

Despite the revenue generated by plantations, the sector has generated few local economic linkages. Banana tissue cultivation techniques and biotechnology are brought from China by companies who employ Chinese workers for technical jobs and do not share these technologies with local companies or farmers (Soe and Dunant Citation2019). Banana companies import almost all fertilisers and pesticides from China rather than use local brands and most of the profits from what is estimated to be a $90million market in northern Myanmar have been captured by Chinese industrial conglomerates like Shenhzen Batian, Yuntianhua Group, and Kingenta (Lin Citation2019).

Large-scale, capital-intensive modes of production require input costs of more than $10,000 per hectare for the first year (and more than $8000 per hectare in subsequent years), with transportation and taxation adding a further $3,600 per hectare (Hayward et al. Citation2020, 24). Despite these costs, banana has been highly profitable with net profit per hectare estimated to be more than $4000. However, the high input costs involved, the lack of state support for smallholder agriculture in Myanmar, and the plantation model adopted by Chinese agribusinesses has prevented any kind of smallholder banana sector from emerging.

The disarticulation of the banana sector from the local economy has been exacerbated by distinct plantation labour regimes. Although banana companies in Kachin State employ approximately 80,000 workers, more than 90% of this labour force comprises migrant workers recruited from other parts of Myanmar (Hayward et al. Citation2019, 35; Humanity Institute Citation2019). There are various reasons for this. They are cheaper and employed through Burmese labour brokers who can source large numbers of workers quickly from the ranks of desperate, landless rural populations in central Myanmar. Migrant workers are also viewed as more compliant and possessing less bargaining power than local workers, who may have connections to media and civil society organisations, local MPs, and armed organisations. The fact that many Kachin are Christian and expect to not work on Sundays also meant companies favoured non-local labourers (Nyein Citation2020).

Furthermore, little of the income that wage labourers earn circulates in the local economy. Wages are very low and are often paid to workers as a lump sum at the end of the harvest to ensure they do not leave. In the interim they are forced get by on meagre subsistence payments. Workers also typically stay within the confines of the plantation. This is partly because employers often withhold their ID cards, but also because wages are often calculated as a share of the post-harvest profits, forcing labourers to work long hours to try to ensure the quality of the plants they manage. Whilst some local people are employed on the plantations, especially at harvest time when companies take on extra labourers, the sector has not generated sufficient quantity or quality of local employment to become a significant support for local livelihoods.

Plantations have also seriously eroded the region’s ecological base, caused far-reaching environmental damage and adversely impacted the livelihoods of those who continue to farm in surrounding areas. Bananas are a heavy feeder crop and highly prone to disease. They thus require lots of water and vast amounts of fertiliser and pesticides. This distinct ecology has exacerbated the impact that profit-driven, unregulated companies have had on local environments and livelihoods. Companies have pumped water from local common waterways onto private plantations, using large tanks to store water throughout the growing season and depriving farmers of the water they need for their own land. Chemical run-off has contaminated nearby land, rivers, and groundwater, preventing people from being able to use local wells (Chan Thar Citation2018), killing off aquatic life that once formed an important part of local diets and incomes (Nyein Citation2020), threatening local bee populations that play an essential role within the wider ecosystem (Tun Lin Aung Citation2018), and killing animals that have drunk water downstream from plantations (Fishbein Citation2019). The unregulated use of powerful chemicals also creates significant health risks and plantation workers have reported respiratory illnesses (Hayward et al. Citation2020; Humanity Institute Citation2019). Although there has been no in-depth study on this issue in northern Myanmar, experiences in neighbouring Laos – where a study by the Laos National Agriculture and Forestry Institute found that 63% of banana plantation workers in northern Laos had fallen ill over the past six months (Parameswaran Citation2017) – reveal the extent of these dangers.

Where has agrarian extractivism left smallholders in eastern Kachin State? Despite the region’s economic integration into Chinese supply chains and the rising demand for agricultural commodities, most smallholders have experienced worsening livelihood insecurity. Many can no longer make a living from farming – either as a result of having sold or leased their land or through outright dispossession of private and communal lands. For those who have been able to hold onto their land, there have been few opportunities for local populations to ‘step up’ the value chain to become commercially successful banana smallholders in a rural economy where the odds are stacked against them. As has been documented in other parts of Myanmar, smallholders that have attempted to produce cash crops on their own land have struggled to generate the economies of scale required to offset investment costs, while the volatility in commodity markets, the lack of state support for smallholders, the difficulty in accessing credit and the subsequent reliance on expensive private moneylenders, have exposed many to debt and subsequent land dispossession (Meehan Citation2021; Woods Citation2020). Due to the high input costs documented above, these dynamics are particularly strong in the banana sector.

Nor do rural populations have much scope to ‘step out’ of smallholder agriculture. Waves of extractivism have drained vast wealth from the region but provided few foundations for wider economic development. Locally owned small and medium industries are almost entirely non-existent. Outside of farming there are few job opportunities and unemployment – amongst young people especially – is a major problem. Smallholders have responded in various ways to worsening livelihood insecurity. As has been well-documented in the literature, some go in search of work in mining areas across Kachin State – especially to the jade mines in Hpakant – or migrate abroad in search of work (Kyi Citation2013; Lin et al. Citation2019; Prasse-Freeman Citation2022; Sadan and Dan Citation2021). Less well understood has been the role that the opium economy has come to play in supporting some households whose livelihoods have been badly affected by the region’s banana boom.

5.6. Situating the opium economy in extractivist landscapes

At the same time as smallholders in lowland areas around Waingmaw and Myitkyina have faced worsening livelihood insecurity from the banana boom, opium cultivation expanded significantly in NDA-K controlled areas (). Prior to 2009, the pressures on the NDA-K to avoid antagonising its relationship with the Myanmar government, at a time when other militias had been targeted on drug charges when they stepped out of line, had required some caution around involvement in the drug trade. The transformation of the NDA-K into a Border Guard Force (BGF) in 2009 changed this. By accepting greater constraints on its political and administrative autonomy and agreeing to operate within the Myanmar Army chain of command, the NDA-K solidified its relationships with military authorities.

Following this agreement, the Myanmar government established a greater presence in NDA-K territories, strengthening its offices in Chipwe, Pangwa and Kanpaiti, and NDA-K troops were enlisted to fight against the KIA after the collapse of the ceasefire in 2011. In return, the BGF agreement protected the NDA-K’s business activities and offered new economic opportunities, including greater scope to engage in the drug trade without the risk of censure. The NDA-K had already facilitated some Chinese investment in agricultural ventures including tea, Chinese cedar wood, black cardamom (known locally as ‘China spice’), walnuts and opium. The high demand for opium and heroin in nearby mining and logging areas, as well as in China meant that poppy cultivation represented an enticing business opportunity. This resulted in new patterns of investment and production techniques in the opium economy. Chinese investors partnered with the NDA-K to establish poppy farms on large plots of land that employed significant labour, mechanised production by using basic tools such as tillers, and invested in fertiliser and irrigation. As one Chipwe resident explained,

Chinese people come and grow opium on a huge scale over many acres, so the local villagers just worked for those Chinese people. Our villagers worked as seasonal temporary workers or as wage labourers. They could earn more than 100 Chinese yuan, a day which is more than 20,000 Burmese kyat.

The concentration of opium cultivation in NDA-K territories in the Kanpaiti-Sadung-Chipwe region has also been the result of increasing crackdowns on drug production by the KIO and a large Kachin anti-drug social movement called Pat Jasan, which emerged in 2014 in response to the crisis of illicit drug use amongst local populations (Dan et al. Citation2021; Sadan et al. Citation2021). Supported by the KIO, Pat Jasan has sought to eradicate illicit drug production and consumption, and this has included destroying poppy fields. The NDA-K has rebuffed attempts by Pat Jasan to operate within its territories and has thus provided a haven for investors and smallholders. As one long-time resident of Sadung reflected on the changing patterns of opium cultivation and eradication,