ABSTRACT

The long-term (AD 1300–1800), multi-scale interactions of monocropping and subaltern agri-food systems of Andalus (Spain) and coastal Peru reveal the entangled transformations of the Plantationocene. Historically convergent colonial monocultures (wheat, sugar, cotton, sheep, cattle) entangled with the divergence and plurality of resilient yet precarious diverse-food affordances of subaltern groups (peasants, indigenous people, enslaved persons, Mudejares, Moriscos). Using political ecology, the comparative cases illuminate how Plantationocene colonial entanglements were shaped through spatial movements and social-environmental affordances of biota, populations, and institutions. New empirical understanding and a novel conceptual and analytical framework offer insight into Plantationocene pathways, alternatives, and struggles.

I. Introduction: Plantationocene entanglements of monocropping and subaltern diverse-food strategies

This study examines the long-term, multi-scale interactions and cross-cutting influences of the global monocultures of colonial societies and the diverse-food strategies of subaltern groups using a historical case study (AD 1300–1800) of Andalus (Spain) and Peru. Insight on the non-binary, connected relationality of contrasting agri-food politics and assemblages (Carolan Citation2018) motivates this study’s goal to advance understanding of the Plantationocene (Haraway Citation2015). The Plantationocene is distinguished by the racialized, colonial, and corporate exploitation of people and the environment (Barua Citation2023; McKittrick Citation2013; Murphy and Schroering Citation2020) through the global proliferation of agri-food monocultures (specialized agricultural production and food systems based on single types of crops and livestock). Additional agronomic, cultural, and economic qualities of Plantationocene monocultures include high levels of agrochemical and water inputs, the exploitation of precarious workers (e.g. historically peasants, indigenous people, enslaved Africans, immigrant farmworkers), and the economic and geographic characteristics of long-distance and colonial power, extractive logics and monopoly markets, territorial control and enclosures, and cross-scale mobility (Barua Citation2023; Chao et al. Citation2023; McKittrick Citation2013; Wolford Citation2021).

By framing the Plantationocene concept and its analytics as inclusive of both monoculture and subaltern diverse-food strategies – evident in their historical interactions and ongoing influences – this study seeks to contribute to socially just and sustainable agri-food alternatives. Here our study responds to calls that ‘what the [Plantationocene] concept does not yet effectively do is bring into relief the subaltern archipelagos of agrobiodiversity that the Plantationocene spawned’ (Carney Citation2021, 1094). Our framework of the Plantationocene uses the idea of political-ecological entanglements as the relationships of humans and non-humans whose multiple forces, directionalities, and scales produce historical change (Nading Citation2013; Neely Citation2021; Voelkner Citation2022; Zimmerer, Rojas, and Hosse Citation2022). Formative Plantationocene pathways entangle developments of both the expansive monocropping that propels oppressive political ecologies of socioenvironmental destruction and the diverse-food strategies of subaltern survival and resistance that can advance social justice-guided sustainability (Carney Citation2003; Citation2021; Carney and Rosomoff Citation2011; Watkins Citation2021; Wolford Citation2021; Zimmerer Citation2015; Zimmerer et al. Citation2023).

In broad overview, this study considers a triad of defining political-ecological entanglements of the Plantationocene. First, we frame colonial monocropping and diverse-food strategies of subaltern groups as contrasting yet entangled political-ecological transformations. This approach seeks to move beyond a sole agri-food focus (monocropping or subaltern) with the other mode treated as antithetical, unrelated, or functionally derivative. Second, we examine multi-scale, spatial movements – ranging from transoceanic or global to local – of colonial power, populations, and diverse food biota (also referred to as subaltern agrobiodiversity or the distinct sociocultural-and-ecological food types and sub-types combining human-biota assemblages of plants, animals, and other non-human elements). This mobility entangled the Plantationocene historical transformations of monoculture and subaltern food strategies. Our attention to wide-ranging movements (long-, medium, and short-distance) of food biota through colonial spatial networks and landscapes complements current understandings of the Plantationocene spatialities of transported slave labor (Haraway Citation2015, 162), landscape simplification (Wolford Citation2021), and diasporic conditions (Barua Citation2023; McKittrick Citation2013). Third, we frame multi-species food biota as comprising multiple, distinct assemblages and spaces – rather than singular attention to escape crops (Scott Citation2010), plantation gardens (Carney Citation2021), or fugitive landscapes (Zimmerer Citation2015; Zimmerer and Bell Citation2015) – to reveal the plurality of power-differentiated entanglements propelling the Plantationocene.

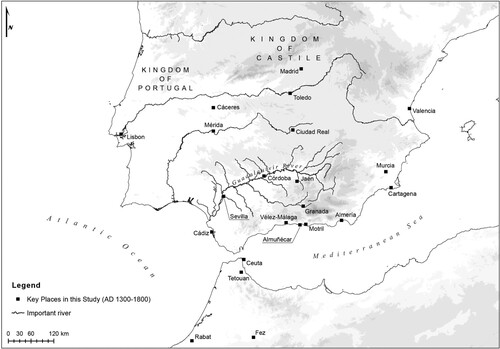

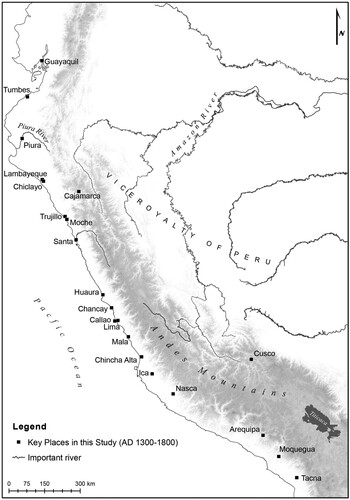

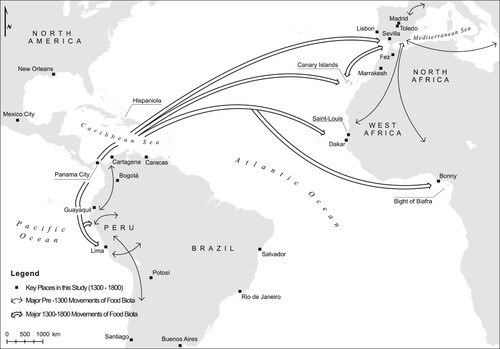

Our research pairs comparative, structured case studies of the interconnected regions of Andalus (Andalucía, Murcia, and Valencia portions of historical southern Spain and earlier Islamic Al-Andalus) and coastal Peru during the AD 1300–1800 period ().Footnote1 Focus on these distinct-yet-similar-and-connected geographic regions enables our historical political-ecological analysis of powerful common developments that were globally important and suggest broad generalization. These two regions shared networked colonial histories and common environmental affordances (sensu Nally and Kearns Citation2020, next section), notably specific diverse-food biota (i.e. the diversity of food-providing organisms including plants, animals, and other organisms) and the landscape roles of environmental aridity (detailed in Study Design). Our comparative approach builds on multi-site designs in Plantationocene and postcolonial research (Carney Citation2021; Watkins Citation2021; Wolford Citation2021) while examining previously understudied regions (colonial territories in present-day Spain and those of the Spanish Empire in Latin America) that entwined with extensive Islamic and African influences (see Study Design and Methods).

Figure 1. Major Plantationocene demographic and food-biota movements of Andalus, Coastal Peru, Africa, and Asia between AD 1300 and 1800 (double arrows) with examples of pre-1300 precursors (single arrows).

The next sections describe the framework and methods to examine historical, political-ecological entanglements of: (1) colonial monocropping of expanding global plantation mainstays (wheat, sugar cane, cotton, sheep, and cattle); (2) nascent plantation monocrops (Asian rice, bananas, orange, indigo, olive, and wine-producing grapes), and (3) more than thirty diverse-food biota in the survival strategies of peasant populations, enslaved persons, and indigenous peoples that highlight connections with Africa and the Middle East. The empirical sections then narrate our results on these entanglements in Andalus and coastal Peru during AD 1300–1800. The discussion advances Plantationocene insights and the key concepts, followed by main concluding points.

II. Theoretical and analytic framework

Our framework integrates three theoretical concepts to analyze the differentiated development and dynamics of monocultures – including specialized livestock – and subaltern diverse-food assemblages of the early Plantationocene. First is the idea of entanglement as introduced (see also Neely Citation2021; Voelkner Citation2022; Zimmerer, Rojas, and Hosse Citation2022), along with its corollary of rooted networks (Bassett, Koné, and Munro Citation2022). The entanglement concept guides our analysis of: (1) relations of monocropping (defined as the processes of single-type agricultural production and food-system functions, see above; on terminological usage of ‘monocropping’ see Wolford Citation2021) and subaltern, diverse-food strategies (in which food is both a material and symbolic resource in the survival and well-being of disempowered groups that identify as resisting and opposing dominant rulers) as contrasting yet interconnected through labor, knowledge-skill, land, water, and seed, among other factors; (2) movements of common food biota entangled in the networks of Andalus and coastal Peru while extending to North Africa, West Africa, the Middle East, and other world regions, in addition to Europe; and (3) networks of colonial powers and institutions, subject populations and their movements and food biota, and environments and landscapes.

Second is the concept of affordances defined as human, biotic, and material capacities (Nally and Kearns Citation2020). Our use of this concept centers on influential environmental, biotic, and geographic capacities and limitations of food systems (including distinctions within non-human assemblages) (Angé et al. Citation2018). Recent affordances theory has been applied to agrarian history (Nally and Kearns Citation2020), landscapes (Kneas Citation2021), and biodiversity (Andersson and McPhearson Citation2018). Our framework of affordances and entanglements enables us to distinguish the agencies of diverse non-humans that otherwise can remain a glossed category in Plantationocene discourse (Haraway Citation2015).

Third is the historical political-ecological concept of landscape differentiation through spatialized colonial power dynamics and environmental factors (Zimmerer and Bell Citation2015; see also Carney Citation2003; Watkins Citation2021). The concept of landscape differentiation is used here for the spatial analysis of monocultures and subaltern diverse food. It is informed further through the landscape ideas of environmental history, historical geography, and archaeology (Kirchner Citation2021; Retamero Citation2021; Sluyter Citation2002, Citation2012).

III. Study design and methods

The methodology of comparative historical political ecology was used to examine Andalus in southern Spain and coastal Peru through their colonial interconnections. This comparative design is well suited to examine formative developments in the global Plantationocene (Bell Citation2015; Carney Citation2021; Offen Citation2004; Watkins Citation2021; Wolford Citation2021). Andalus and coastal Peru were interconnected through colonial movements of food biota and diverse populations (Gade Citation2015), in addition to institutions and other commonalities introduced in Section I. The study design incorporates key inter-regional differences, such as the influences of indigenous people and larger enslaved African populations in coastal Peru. Our initial research (2018–2021) analyzed agrarian and food-system histories to design the preliminary periodization as: (i) formative, global Plantationocene development (1450–1600) and ensuing transitions (1650–1800) toward the modern period (Bell Citation2018; Carney Citation2021; Chocano Citation2020; Wolford Citation2021); and (ii) early Castilian colonization in Andalus and powerful indigenous precursors in Peru (1300–1450) that postcolonial perspectives have shown to be crucial inclusions (Retamero and Torró Citation2018, 3; see also Agresta Citation2021; Glick Citation2005; Lockhart Citation1994).

This study utilized four document types with information on Andalus and coastal Peru: published scholarly works (see references cited in Sections I–V and Appendix 1); published colonial documents created during the time period of interest (e.g. Repartimientos in Andalus; Relaciones Geográficas in coastal Peru); scholarly editions of accounts by colonial authors (e.g. Yahyá Ibn Muhammad Al-Awwam, Bernabé Cobo, Pedro de Cieza de León); and unpublished documents in the Archivo General de la Nacion (AGN) in Lima, Peru. Notes were taken on the types, dates, location, and landscape and environmental information of monocropping and subaltern diverse-food strategies (including diverse food biota of specific crop and animal types); relations of monocropping and subaltern diverse-food strategies to colonial institutions, environmental affordances, and landscapes; and relations to cultural, social, political-economic, and multi-scale spatial movements (local, regional, transoceanic, and global-scale). Critical colonial historiography guided analysis. For example, interpretation of the Spanish colonial chronicler Cieza de León (Citation1984) distinguished places that he actually visited from others he described as first-person travel accounts per then-current representational norms (i.e. autoptic imagination; Safier Citation2014).

A secondary research component consisted of the authors’ fieldwork in Andalus and coastal Peru encompassing informal interactions and landscape visits between 2018 and 2022 (e.g. Red Andaluza de Semilla Citation2022, diverse peri-urban gardens in Piura, Peru 2018 & 2022). Integrating fieldwork with historical and archive research (Watkins and Carney Citation2022; Zimmerer Citation2012, Citation2015; Zimmerer and Bell Citation2015) enhanced our understanding of suggestive though incomplete documentation of the dynamics of diverse-food biota (e.g. zarandaja or West African lablab bean) and upland-valley landscapes (Yahyá Ibn Muhammad Al-Awwam, Bernabé Cobo, Pedro de Cieza de León; see also Agresta Citation2021; Quilter Citation2020).

Finally, the theoretical framework and analyses are used to structure the narration of historical results. Each section’s narrative begins by analyzing the entanglements of diverse-food strategies and biota with spatial movements and influences dating to the 1300s and earlier. The narratives then examine the distinctive colonial monocultures of the 1400s–1700s (including land- and labor-grab political-economic institutions), the entanglements with subaltern diverse-food strategies and biota, and, finally, the role of differentiated landscape dynamics.

IV. Results: colonial monocropping and subaltern strategies in Andalus (1300–1800)

Monocropped and diverse-food biota of Andalus in the 1300–1800 period can be traced back to pre-1300 Iberian agroecologies and food biota movements from Europe, the Middle East, and Africa through the Mediterranean context (, , Appendix 1a). Pre-1300 populations of Andalus grew diverse wheat, barley, rye, fava bean, field pea, lentil, Mediterranean lupine, cattle, sheep, and pigs (Agresta Citation2021; Butzer Citation2005; Peña-Chocarro et al. Citation2019). Early food-biota movements connected Andalus to Africa and the eastern Mediterranean during the long period of Islamic rulers beginning in the 700s. This pre-1300 phase featured a once-argued ‘Arab Agricultural Revolution’ (or ‘Medieval Green Revolution,’ eighth-eleventh centuries) under Islamic rule (Watson Citation1974). These Islamic introductions of food biota to Andalus were subsequently recognized as more spatio-temporally extensive than had been posited (García Sánchez Citation1995; Horden and Purcell Citation2000; Squatriti Citation2014; Trillo San Jose Citation2005). The findings and perspective of geographic research highlight additional long-term historical ties to South and Southeast Asia (Rangan, Carney, and Denham Citation2012) and Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. watermelon, sorghum, lablab bean, cucumber, and cattle; ). Islamic introductions to Andalus included sugar cane, cotton, eggplant, alfalfa, cumin, banana, spinach, artichoke, sour orange, citron, lemon, lime, grapefruit, flax, hemp, and mulberry (Bermejo, Esteban, and Sánchez Citation1998; also Butzer et al. Citation1985; Sauer Citation1993) and new cultivars of olive trees (Diez et al. Citation2015; Jiménez-Ruiz et al. Citation2020; Martínez-Moreno et al. Citation2023; Terral et al. Citation2004), hard wheat (Martínez-Moreno et al. Citation2023; Moragues et al. Citation2007), and date palms (Azuar Ruiz Citation1998; Rivera et al. Citation2013; Sauer Citation1993).

Table 1. Common subaltern crops in contexts of colonial conquests and occupations in Andalus and coastal Peru (1300–1800) (additional details in Appendix 1a).

By 1300, the afore-mentioned biota had become staple foods of the subaltern populations of Islamic and Christian peasants in Andalus as well as enslaved Africans and, later, Mudejares and MoriscosFootnote2 (for further background on the historical roles of these groups see Agresta Citation2021). Subaltern diets, which traced many elements to the Islamic period, were generally diverse and nutritious (García Sánchez Citation1988). Consumption of C4 cereals (e.g. sorghum and millet) was notable, with geographic variations (Inskip et al. Citation2019). Poorer groups consumed less meat and had a plant-based diet of cereals – primarily wheat, barley, sorghum, millet, and foxtail millet – and legumes complemented with diverse fruits and vegetables (García Sánchez Citation1988, 187, 189) that contrasted upper-class meat consumption – especially sheep (mutton), followed by beef (Morales Muñiz et al. Citation2011) along with spices (García Sánchez Citation1988, 186).

Tracing to the 1300s and earlier, diverse knowledge and techniques were used to produce and consume the highly varied food biota of Andalus, thus shaping affordances and multi-functionality (agronomic, agroecological, food) that would later become differentiated under Castilian colonialism (García Sánchez Citation1995; Retamero Citation2021). Annual plants were widely intercropped in polycultures with diverse perennials and tree crops of nuts and fruits eaten fresh, dried, pressed into oils, or ground into flours. This multi-species intercropping (e.g. wheat with olives, figs, and nut trees; sugar cane with citrus and bananas, Mediterranean lupines with grape vines and sumac; ) infused the cultivation of diverse food biota (García Sánchez Citation1995; Bermejo, Esteban, and Sánchez Citation1998, 24). Moreover, in the 1300s and 1400s even commercial cropping in Andalus, such as sugar cane, grape, and mulberry production (for silk-making), were intercropped with food trees and field crops (Fábregas García Citation2018, 311; Trillo San José Citation2004, 210).

Castilian colonizers expanded crop monocultures, as well as specialized livestock, in the Reconquista or ‘Christian feudal colonization’ that by 1300 were already inter-mixed with subaltern diverse-food strategies in Andalus landscapes (; Kirchner Citation2021). This Castilian colonization racialized the accumulation and control of the land and labor of Mudejares, Moriscos, and enslaved Africans as racially ‘other’ populations. The subaltern diverse-food biota increasingly entangled with a series of specialized monocrops (wheat, sugar cane, cotton, sheep, cattle). The Reconquista propelled the "cerealization" of Andalus and other regions as an initial wave of monocrop specialization. Grazing areas for cattle, pigs, and sheep were also integral to the Castilian strategies for territorial control in the Reconquista (Retamero and Torro Citation2018). In addition, certain minor Andalus crops that were perhaps subject to partial specialized monocropping later became major global monocrops elsewhere (citrus, rice, banana, indigo, wine grapes, olive). For example, vineyards were expanded for wine production in the Reconquista (Malpica Cuello and Trillo San José Citation2002; Trillo San José Citation2004, 210), primarily in rainfed lands given to settlers (Martínez Enamorado Citation2010). Yet monocropping was not an inherent property of these biota, as detailed below. The prevalent, intercropping of sugar cane among Mudejar, Morisco, and peasant populations in southern Andalus, for example, illustrated that its monocrop role was ultimately partial in these early Plantationocene pathways.

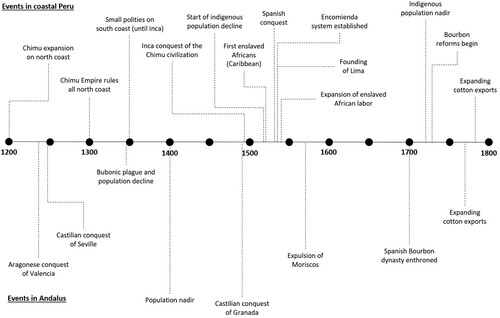

The notable expansions of Andalus monocropping occurred amid large-scale, Castilian settler-colonization occurring both before and after the fall of the Emirate of Granada in 1492 and the expulsion of the Morisco population in 1571 (Retamero Citation2021, 187) ( and ; Appendix 1b). The influential background to this phase was the Castilian military conquest and colonization of the 1300s and 1400s (). Castilian settler-colonization specialized in monocropped wheat, detailed below, even as sugar monocrops expanded in southern Andalus (e.g. Motril, Almuñecar, and Vélez-Málaga; ) to become Europe's predominant sugar source for a time.

Figure 3. Timeline of major events in Andalus (lower) and Coastal Peru (upper), 1300–1800, with key precursors of the 1200s.

Table 2. Overview of expanded monocropping and livestock in Andalus (1300–1800) (additional details in Appendix 1b).

Castilian colonization drove monocropping (including specialized livestock production) though the re-feudalization of land tenure with large estates (latifundia) locally interspersed with small- and medium-size landholdings of peasant farms (minifundia) around villages or alquerías (Carmona Ruiz Citation2018; Guinot Rodríguez Citation2018; Segura Graíño Citation1982). Repartimiento, the colonial institution of land allocation and regularization, was a common Castilian ‘plunder-allocation technique’ of these re-feudalized landscapes (Malpica Cuello Citation2018; Retamero and Torró Citation2018, 3). The Castilian colonial land grabs were also facilitated by the demographic decline of the Bubonic plague in the 1300s. Land allotments were divided by rank among the conquerors. Thousands of new settler-colonists included large peasant populations as well as the military and nobility (Glick Citation2005, 227; Retamero Citation2021).

Under the Castilian colonial regime, feudal and ‘free’ peasants supplied the labor for estate monocropping (e.g. wheat, cattle, sugar cane) and for their own sustenance and small-scale marketing (Glick Citation2005, 164). Mudejares and Moriscos, however, were prohibited from land ownership and required to pay tribute to the owners of seignorial estates, including higher in-kind payments than imposed on Christian peasantsFootnote3 (Molina, Luis, and del Carmen Veas Arteseros Citation2009, 104; Torró Citation2009). Moreover, Mudejares and Moriscos were tied to the land through mobility and residence restrictions (López and Retamero Citation2017; Torró Citation2009). While various goods were paid as feudal taxes or tribute (e.g. grains, chickens, garlic, onion, lamb, linen yarn, olive oil, fruits), these levies limited colonized peasants’ capacity to farm and feed themselves (Torró Citation2009).

Sugar cane monocropping in Andalus, which relied on salaried laborers, refining technology and infrastructure, and rented fields, was driven by the investment of capital from seignorial land rents (la Parra López Citation1995; Moreno Moreno Citation2020) and from Genoese and other European merchants (Galloway Citation1977, 192–193; Pérez Vidal Citation1973, 41–44). Expanded sugar monocropping replaced polyculture by forcing the peasant sharecroppers – notably dispossessed Moriscos with limited mobility (Torró Citation2009; Trillo San José Citation2004) – to produce caneFootnote4 (Galloway Citation1977; Pérez Vidal Citation1973). By the mid-1500s, the Morisco population supplied most labor for Andalus sugar (Malpica Cuello Citation1990, 158). This production fell sharply in the late 1500s (Pérez Vidal Citation1973) due to the Morisco expulsion and lower costs in new colonies. Meanwhile, monocrop diversity was thinned; traditional sugar cane varieties in Andalus may have been ‘wiped out’ by the Atlantic and American varieties (Fábregas García Citation2018, 321).

Enslaved North and Sub-Saharan Africans were made to work primarily in urban activities in Andalus (Phillips Citation2013), with their labor directed secondarily to agriculture. Slavery was present though uncommon in Andalus sugar production and processing (Fábregas García Citation2018, 321). Nonetheless, the region's notable slave labor and oppressive conditions (Fábregas García Citation2018, 321–322; Pérez Vidal Citation1973; Phillips Citation2013, 114–115) were influential as ‘the connection between slavery and sugar had been planted [in Andalus], setting the groundwork for the plantation system in the Americas’ (Phillips Citation2013, 115).

Diverse peasant food biota and foodways were entangled precariously with expanded estate monocropping and livestock herds. Descriptions of diverse plants and their food uses – peasant produced-and-consumed plants and animals as well as those in trade and tribute – were often more extensive in Arabic texts than later compilations (Bermejo, Esteban, and Sánchez Citation1998, 20). Continued polycultures, which included extensive tree intercropping(García Sánchez Citation2011), facilitated the development of new variants through grafting (García Sánchez Citation2019; Trillo San Jose Citation2005). Diverse food biota persisted to a large degree in Andalus (de Herrera Citation[1513] 1818), mainly through the subaltern labor and knowledge of women and men. 195 cultivated food sources were detailed in the late 1500s (Trillo San José Citation1996, 118), though the pressing precarit under Castillian colonialism is presumed to have pressured the affordance limits of this production (Trillo San Jose Citation2005, 17, 179).

Cultivators’ own differentiation of the non-human, multi-species mélange, as distinct from expanded monocropping, provided soil fertility management through crop rotations with diverse nitrogen-fixing food legumes and extensive agrosilvopastoralism. Leguminous chickpea or garbanzo, lentil, fava bean, field pea, lupine, and grass pea were typically rotated with wheat, barley, rye, and sorghum (de Herrera Citation[1513] 1818) and possible others (e.g. hyacinth bean and sesame). Andalus colonial networks from Latin America subsequently incorporated maize, potato, squash, common bean, lima bean, and scarlet runner beans among other American food plants in the 1500s and 1600s. Fertility-enhancing agrosilvopastoral systems, which utilized farm animals and tree biota such as oaks, walnuts, chestnuts, and acacia (algarrobo) (de Herrera Citation[1513] 1818), were similarly extensive in Andalus.

Colonial Andalus landscapes contained contrasting affordances of the mostly dry-farmed uplands and the intensively produced valleys created in earlier Islamic landscape management and categorization (e.g. Al-Awwam Citation1988). Castilian land grabs bridged these landscapes (e.g. deploying fiats that forcibly displaced Islamic populations to designated uplands following Morisco uprisings; Retamero Citation2021). Yet, rainfed lands (tierras de secano or de sembradura) were also allocated to colonial settlers for dedicated cultivation of cereals, vineyards, and olives (Guinot Rodríguez Citation2018; Martínez Enamorado Citation2010; Segura Graíño Citation1982). Repartimiento documents contrasted these lands with the irrigated valley bottoms and terraces (bancales) where settler families grew a greater variety of crops (e.g, mulberry, Armenian plum, carob tree, plum, lemon, quince, walnut, olive, and grape) usually in smaller plots (Guinot Rodríguez Citation2018; Martínez Enamorado Citation2010; Segura Graíño Citation1982; see also Agresta Citation2021; Kirchner Citation2021, 17). Colonial integration of the differentiated landscapes (Torró Citation2021) weakened as new deforestation, overgrazing, and erosion degraded the uplands (Butzer Citation2005). Moreover, new land-use conflicts emerged as Castilian wheat growers and confederated sheep herders expanded to Andalus (Agresta Citation2021; Dunmire Citation2004, 19–20). Consequently, alfalfa (an earlier Islamic introduction) was expanded in valleys as livestock feed (Trillo San José Citation1996, 118). Landscape differentiation and dynamics thus entangled with other forces, as described above, in the Plantationocene monocropping and subaltern diverse-food strategies of Andalus.

V. Results: colonial monocropping and subaltern strategies in Coastal Peru (AD 1300–1800)

Pre-European, indigenous agriculture and food influenced the ensuing colonial transformations of coastal Peru. Between AD 1300 and 1532, the agri-food systems of the Chimu and Inca empires provided diets of diverse indigenous plant components (e.g. maize, common and lima beans, sweet potato, chili pepper, squash) including trees (e.g. guanabana, avocado, lucuma). Diets were similar to the smaller polities elsewhere in coastal Peru (Cutright Citation2015). The varied diet is consistent with evidence of fields of diverse sizes (Caramanica et al. Citation2020; Dillehay, Kolata, and Ortloff Citation2023) that do not suggest large-scale monocropping. Multi-site studies highlight that diverse-food strategies in coastal Peru during the AD 1300–1532 period also featured indigenous Andean potatoes, other tuber- and root-bearing crops (manioc, sweet potato, yacon, achira, and ulluco), tree and perennial crops (chirimoya, pacae, papaya, and pineapple), and less-known but important food biota (e.g. cannavalia beans; Towle Citation2017). These foods were influenced by pre-1300 regional exchanges that had brought dozens of indigenous American crops to coastal Peru (e.g. maize, common beans), as shown by single-line arrows in .

After the 1532 invasion, Castilian colonizers developed a series of monocrops (wheat, livestock, sugar cane, cotton) in coastal Peru () that marginalized yet did not replace the diverse food biota of pre-1532 indigenous cultures and civilizations (see below). Similarities of coastal Peru monocrops to Andalus were fashioned through the common background characteristics of Castilian conquest and agrarian colonization (e.g. colonial land and labor institutions described below), defining crop and livestock movements, and shared environmental affordances of biota and colonial landscapes.

The role of monocrops as political-economic drivers began by the 1540s with single-crop wheat fields in coastal Peru (Bell Citation2018, 40; ; Appendix 1c). Progeny of seeds said to have been brought by Beatriz Salcedo (a colonial Moorish woman), wheat became widely monocropped under irrigation in coastal valleys around Lima and elsewhere (). The monocropped wheat was shipped to regional and long-distance markets (e.g. Panama and Chile, Cárdenas Ayaimpoma Citation2014). At the same time, large cattle and sheep herds (notably the Merino breed from Andalus) proliferated (Cobo Citation[1639] 1935; Cobo Citation1956). Specialized livestock production used alfalfa – a North Africa-via-Andalus biotic component – as a principal feed (Macera Citation1966). Wheat monocropping in coastal Peru later declined in the 1600s and 1700s due to several factors (Bell Citation2018).

Table 3. Overview of expanded monocropping and livestock in Coastal Peru, 1300–1800 (additional details in Appendix 1c).

As wheat declined, the monocropping of sugar cane expanded in coastal Peru (Flores Galindo Citation1984, 21–29; Pérez-Mallaína Citation2000; Dargent Citation2017). Colonial networks introduced Caribbean cane varieties (Klaren Citation2005) such as ‘mixed race’ (caña criolla) or ‘indigenous,’ (caña de la tierra) that highlighted colonial distinctions, as did the connotation of azúcar pagano (‘pagan sugar’; López Morales Citation1990, 197). Large plantations in coastal valleys near Trujillo and Lambayeque () produced more than 400,000 pounds of sugar annually (Cushner Citation1980, 123). Cotton became a colonial monocrop in coastal Peru in the late 1700s (). This new ‘Egyptian cotton’ (Alfaro y Lariva Citation1870) combined ancestral lines traced to Andalus and the Mediterranean as well as to indigenous American cotton that circulated globally after 1500 (Sauer Citation1993). Producers could sow cotton in soils depleted of nutrients by sugar cane (Watson Citation1974, 15). Olives and bananas were intercropped or produced in small- to medium-scale monocropped fields (Cushner Citation1980; Flores-Zúñiga Citation2008; Gade Citation2015; Keith Citation1976; Vega de Cáceres Citation1996).

Booming sugar cane monocrops in coastal Peru were capitalized by major colonial-institutional sources (e.g. the Jesuits) as well as urban and rural elites (especially after Jesuit expulsion in 1767; Chocano Citation2020, 42–49; see also Cushner Citation1980; Vergara Citation1995). Capital in this sugar monocropping also derived from the widespread colonial land grantees (encomenderos) that had specialized in wheat monocropping. Common Spanish colonial institutions that underwrote pervasive land grabs – including the encomienda, composición de tierra, and repartimiento – propelled widespread monocropping. Built on Castilian precursors, these colonial land institutions were used to dispossess indigenous common lands (Cárdenas Ayaimpoma Citation2014, 139) and regularize the individual lands of indigenous households (composiciones de tierras; AGN Citation1594–Citation1597; AGN Citation1594). In conjunction with mercedes grants and semi-feudal hacienda estates, these Spanish imperial institutions unleashed a surge of colonial monocropping by usurping extensive swaths of indigenous land.

Labor for monocropping was channeled partly through Castilian colonial institutions that controlled indigenous people (e.g. encomienda tribute), enslaved Africans, criollo peasants (mestizos), and ‘freed slaves’ subjected to colonial institutions. Encomienda control of copious appropriated labor and land underwrote the transition to monocropping in coastal Peru, thus demonstrating a direct tie to this institutional cornerstone of Castilian colonialism already applied in Andalus. By the 1570s, indigenous labor was being extracted not only by the massive dispossessions of the colonial land-grab institutions but also by the imperial resettlement fiats of the reducciones (forced population nucleation, likewise already in use in Andalus) and other widespread illegal appropriations. Direct and violent expropriation of indigenous labor was commonly used in each of the monocrops (e.g. cotton; Palomino, Guillén, and Maticorena Estrada Citation1996).

Populations of enslaved Africans on monocrop plantations in coastal Peru expanded amid the catastrophic mortality devastating indigenous population due to disease and exploitation. People of African origin, nearly all enslaved persons and a small portion of ‘Free Blacks’ concentrated in the Lima region, numbered similar to colonial Spaniards in the late 1500s (Aldana Rivera Citation1988, 131). The enslaved persons were mostly traded from other colonial entrepôts following enslavement in West Africa (). Enslaved Moors from Andalus and North Africa and Andalus were termed ‘white slaves’ in Peru (Bartet Citation2005, 45). By the late 1500s, these groups of enslaved people of African descent were a major labor source throughout coastal Peru (Cushner Citation1980; Lockhart Citation1994; Palomino, Guillén, and Maticorena Estrada Citation1996). Many worked on monocropping estates (Espinoza Claudio Citation2019) while others labored on small farms and were ‘rented out’ for the rapid expansion of livestock herding (Lockhart Citation1994). Moors and Moriscos formed important colonial populations in coastal Peru (Bartet Citation2005; Manrique Citation1993, 556; Vega Citation1991) that became recognized in indigenous cultures (Zimmerer Citation1996). Additionally, Spaniards from Andalus representing diverse social ranks were predominant in the colonizing population of Peru (Vega Citation1991).

Precarious entanglements of small-scale, diverse-food strategies were wrought with colonial monocropping and accompanying transformations. A general model of this entanglement was illustrated by indigenous peasants on the large encomiendas in the 1500s in coastal Peru. While producing their own small plots and farm animals (Cárdenas Ayaimpoma Citation2014; Lockhart Citation1994), the bulk of their land, labor, and production supplied encomendero tribute that was channeled to monocropping. The capacities of subaltern diverse-food strategies, including the labor and knowledge of women cultivators, were therefore entangled prodigiously yet precariously with the rise of monocropping.

These entanglements became varied and widespread as subaltern groups struggled to eke out food and livelihood strategies in colonial Peru. By the mid-1500s, the cultivation of diverse populations in the Lima valleys created ‘an impressive garden spot, full of closely spaced small holdings’ (Lockhart Citation1994, 186). Land access often occurred through rentals and sharecropping that included numerous persons of indigenous and African descent (Cárdenas Ayaimpoma Citation2014, 159, 162–163). Subaltern subsistence crops occupied fields and gardens in haciendas and around urban areas that combined with market and exchange production (subaltern ‘relative specialization’ that was widespread in colonial Peru; see Chocano Citation2020). Such fields and gardens were combined with crops and livestock concealed from colonial tribute extraction (on escape crops and fugitive landscapes in the colonial Andes see Zimmerer Citation2015; Zimmerer and Bell Citation2015).

Biotic movements and affordances further entangled monocropping and subaltern agriculture and food in coastal Peru. Extensive colonial trade and migration networks connecting to Andalus, Africa, and elsewhere fueled the widespread mobility of food biota (Gade Citation2015). Early voyages directed by the Castilian Crown were among the most documented biotic movements to the Caribbean and Latin America, with the second in 1493 including notable Euro-Mediterranean mainstays, such as wheat, olives, and wine grapes. Subsequent monocrops, such as sugar cane, Egyptian cotton, Asian rice, and oranges were similarly transferred by trade and migration, often via the Canary Islands and Caribbean. These early Plantationocene biota then passed colonial waystations, principally Panama, to the primary ports of Peru, especially Callao. Such biotic networks transporting crops and livestock were partially differentiated between those furnishing colonial monocrops and subaltern seed and stock (Gade Citation2015).

In addition, indigenous diverse food biota that had expanded during the Chimu and Inca empires in the pre-1532 period became vital to survival strategies of the subaltern populations of coastal Peru. These resilient indigenous elements that became culturally widespread were referred to as de la tierra (‘of the land’) in the post-1532 Spanish colonial lexicon. The colonial importance of indigenous diverse foods was reflected in the Quechua-language idea of kawsay (‘Living Well’) that came to indicate the subalterns’ customary, moral expectations of adequate food and resource access (Mejía Xesspe Citation1931; Zimmerer Citation2012).

The post-1532 food biota of coastal Peru were enhanced by movements traced to Andalus, Africa, and the Middle East (). Numbering nearly three dozen (), most food biota moved via Andalus and the Canary Islands to the Americas including coastal Peru. Examples included garbanzo bean, lentil, spinach, honey melon, citron, banana, lemon, limes, eggplant, figs, and date (Azuar Ruiz Citation1998; Bermejo, Esteban, and Sánchez Citation1998; Cieza de León Citation1984; de la Vega Citation1976; Jiménez de la Espada Citation1881; Rivera et al. Citation2013) (). Additionally, the African foods that moved to coastal Peru included banana, lablab bean, cucumber, and watermelon. Possible further additions from Africa, though undocumented in our research to-date, were plantain, sesame, sorghum, millets, and African rice (). Grown in Africa in intercropped fields and polycultural gardens, they were transported to the Americas (Carney Citation2003; Watkins Citation2021) and, at least partly, to Peru.

Agroecological benefits and nutritious foods (e.g. legumes, vegetables, fruits, chickens, and ample others) were furnished by the diverse food biota adopted after 1532 in subaltern farming and food spaces in coastal Peru. This subaltern production incorporated assemblages of food biota that tiered with new labor-saving elements such as tree crops from Andalus (e.g. citrus) and Africa (e.g. plantain) to create innovative diverse-food strategies (e.g. Cieza de León Citation1984, 119). Combinations of diverse indigenous and new food biota were inter-mixed in dooryard and kitchen gardens that were widely used among subaltern groups. One early colonial account referred to huertas curiosamente plantadas (‘curiously planted gardens;’ published later in Jiménez de la Espada Citation1881, 153). Furnishing shade and soil protection, the multi-species assemblages enhanced the use of space, sunlight, and soil nutrients and elevated pest and disease resistance (Dunmire Citation2004).

Enslaved Africans in populations throughout coastal Peru (Macera Citation1966) managed these agroecological affordances to provision sustenance and, in cases, small-scale marketing. Their plots included plantation gardens adopted from West African garden, polyculture, and agroforest biota and techniques (see Carney Citation2003; Carney and Rosomoff Citation2011) that became microspaces of resistance (e.g. Piura; Espinoza Claudio Citation2019, 191) by fusing the diverse biota tracing to West Africa, Andalus, and indigenous elements. Further agroecological strategies were afforded by small-farm animals such as chickens and pigs. Additionally, cuy, or guinea pig, was common among indigenous people (Palomino, Guillén, and Maticorena Estrada Citation1996). More generally, the diverse food biota produced in coastal Peru afforded potential ‘summer crops’ and ‘winter crops’ in a single year (Cobo Citation1956), though this double-cropping was likely constrained by land, labor, and water limitations.

Finally, valley-and-upland landscapes contoured the agroecological affordances of monocrops and diverse-food biota through their associated water gradients. Coastal valley bottomlands were amply irrigated owing to local labor, knowledge, and organizations as well as indigenous irrigation infrastructure (Deneven Citation2001). The role of valley bottomlands as core settlement-and-monoculture spaces was cemented under Spanish colonialism (Zimmerer and Bell Citation2015), while patchworks of subaltern land use extended to the arid interfluves where intermediate areas were well suited to diverse, subaltern food biota. Landscape differentiation and dynamics of coastal Peru thus entangled with above-described elements in the Plantationocene development of monocropping and subaltern diverse-food strategies.

VI. Discussion: entanglement and transformation in the Plantationocene

This study and its framework elucidate the Plantationocene entanglements (AD 1300–1800) that propelled the transformations of monocropping and subaltern diverse-food strategies in Andalus (Spain) and coastal Peru. Entanglements drew on historical movements at intra- and inter-regional scales of populations and food biota. These differentiated entanglements (sensu Davis et al. Citation2019, 5) transformed the intersecting arcs of Plantationocene monoculture development and subaltern survival strategies. The development of our conceptual and analytical framework using comparative historical political ecology has elucidated three themes of political-ecological entanglement as integral to the early Plantationocene.

The first thematic entanglements of this framework are the closely related yet sharply differentiated pathways of colonial monocropping and subaltern diverse-food strategies. In Andalus and coastal Peru the historical sequences of monocropped wheat, sugar cane, and cotton (as well as specialized large-scale cattle and sheep production) were forged in the study’s sub-period of formative global Plantationocene development (AD 1450–1600). The common, minor monocrops in this pair of regions (citrus, rice, banana, indigo, wine grapes, olives) became global plantation staples elsewhere.These multiple monocropping pathways become powerful precursors of the present-day ‘global plantation’ (Uekötter Citation2014). Diverse foods that were enmeshed in survival, moral economy-type sustenance, and resistance (Carney Citation2021; Scott Citation2010; Zimmerer Citation2012) anchored a plurality of sub-altern agri-food systems and guided affordances that persisted precariously amid expanding colonial monocrops.

This first entanglement demonstrated the relationally transformative pathways of monocropping and subaltern diverse-food strategies (Zimmerer, Rojas, and Hosse Citation2022). The latter were not merely derivative artifacts of historical or political-economic processes nor were they singularly agential. Affordances – encompassing political-ecological and landscape dimensions – have enabled subaltern groups to draw upon diverse food biota, albeit often tenuously, in continued contestations. Combined concepts of entanglement and affordances guide our analysis of political-ecological relatedness-and-differences of monocrops and diverse food biota. The perspective of this first entanglement highlights how both the monocropping of imperial colonialism and the strategies of precarious subaltern survival were intimately and mutually embedded in Plantationocene developments. It offers insight into differentiated non-human-related worlds of the Plantationocene to advance conceptually beyond the generalized notions of the ‘multi-species assemblages’ of subaltern agroecology or the ‘industrial ecologies’ of plantation monocultures.

The second entanglement comprised the historical spatial movements embedded in the agri-food systems of Andalus and coastal Peru together with extensive connections to Africa and Asia. People, institutions, power configurations, and food biota were moved via myriad colonial connections in both monocropping (e.g. monocropped biota and colonial land and labor grabs) and subaltern diverse-food strategies. Influential long- and medium-distance movements, as well as local scales, linked the colonial networks of people and biota of Andalus and coastal Peru to North Africa, West Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia in addition to Europe. Similarly, this study elucidates the networked entanglements of survival-enabling, subaltern foods () – a fused, portmanteau of indigenous diverse-food biota incorporating elements from Andalus, indigenous America, Africa, and the Middle East – via non-local networks. The multiscalar, diasporic movements of the Plantationocene (Barua Citation2023; McKittrick Citation2013) thus contributed to the differentiated human social dynamics and non-human assemblages of monocropping and diverse subaltern agri-food systems.

Table 4. Andalus and Coastal Peru: shared thematic entanglements in the early Plantationocene (AD 1300-1800)

Illustrating this second entanglement, Castilian colonialism historically propelled both the convergence and divergence of agri-food systems across global sites in the Plantationocene through multi-scale spatial movements. As shown, the early developments, which were evident in the 1300s and 1400s (Andalus under contesting Castilian and Islamic rulers, coastal Peru under Chimu and Inka rulers), had occurred with scant evidence of large-field monocultures. Such early legacies illuminate how Castilian colonial institutions and political economy enrolled the affordances of crops, livestock, and resources in the notable expansions of monocropping beginning in the 1400s in Andalus and in the 1500s in coastal Peru.

In the third entanglement, subaltern agrobiodiversity countering the existential threat of colonial monocropping (Carney Citation2021; Watkins Citation2021) was entwined pluralistically with the survival, livelihoods, and landscapes of diverse subaltern groups and food biota. Indigenous people and enslaved Africans in coastal Peru, as well as Mudejares and Moriscos and local Christian peasants in Andalus, differed in their diverse-food biota. Though varied and distinct, their livelihood dynamics appeared to overlap in the exchange of diverse seeds, livestock, and local knowledge. For example, Peru's indigenous people, enslaved Africans, and criollo peasants relied on certain similarities of food biota, therefore suggesting seed-network connectivity for fields, gardens, and small-livestock integration. Moreover, subaltern diverse-food strategies extending to upland and interfluve landscapes in Andalus and coastal Peru upended the Spanish conquest's two-part geographic model of non-valley spaces as wastelands (despoblados; Cieza de León Citation1984, 119) that was widely imposed and resisted in early colonial Latin America (Zimmerer and Bell Citation2015).

This study contributes to a trenchant critique of the “Columbian Exchange” as overlooking subaltern agency (Carney Citation2003, Citation2021; Watkins Citation2021; see earlier multi-species approach in Carney and Rosomoff Citation2011). We center our analysis on multiple diverse subaltern populations and dozens of diverse food biota and regions that are not a focus of previous research from a post-Columbian Exchange perspective, Similarly, we provide a novel, much-needed advance to this perspective by interweaving the myriad role of colonial institutions as a main fabric entwining subaltern foods and diverse-food strategies across long-distance movements. Here, one principal advance is to illustrate the dynamics of the multiplicity of differentiated food biota, production spaces, and subaltern groups. This advance builds upon and yet differs from the thematically singular analysis of escape crops or fugitive landscapes (Scott Citation2010; Zimmerer Citation2015), singular niches (secondary forest, plantation garden, agri-forest), or individual vegetal protagonists such as mikania, African rice, or oil palm (Barua Citation2023; Carney Citation2003, Citation2021; Watkins Citation2021).

Additionally, our engagement with alternatives offers specific suggestions to de-romanticize Plantationocene alternatives and highlight precarious subaltern struggles (Wolford Citation2021). Diverse food biota were commonly utilized by multiple groups (e.g. enslaved Africans and indigenous people in coastal Peru). This perspective complements yet differs from within-group perspectives (e.g. within enslaved African societies of the Caribbean and Brazil, respectively; Carney Citation2021; Watkins Citation2021). Capacity for between-group exchanges of diverse plants and livestock could have gained importance with intensified subaltern marginalization during the expanding Plantationocene. Between- and potentially cross-group seed networks, for example, would have provided food biota to enhance subaltern livelihoods and survival (Capparelli et al. Citation2005) with affordances suited to their marginalized landscapes (Rignall Citation2016).

Finally, we may outline related avenues of future research. Irrigation technologies and infrastructure in regions such as Andalus and coastal Peru have been globally paramount yet contested as Plantionocene developments of large-scale water systems and potential small-scale irrigation alternatives. Similarly, the development of large-scale, Plantationocene livestock production has been entangled with small-scale and diverse animal assemblages. Other related research themes include before-and-after studies of Plantationocene impacts (distinct from the focus on entanglements in this study) and Plantationocene alternatives (addressed here as implications).

VII. Conclusion

Like microbes and viruses – where knowledges and practices of their entanglement (e.g. human-wildlife and urban-rural interactions) are vital even in regimes of severe disentanglement (e.g. masks, quarantine) (Voelkner Citation2022) – Plantationocene monocropping and subaltern diverse food strategies have entailed multiple entanglements that continue today and that urge in-depth research. These differentiated entanglements have fueled the transformations of increasingly expansive and destructive Plantationocene monocropping as well as the diverse-food strategies of multiple, marginalized subaltern groups. We conclude that colonial monocropping and subaltern agrobiodiversity were both extensively entangled and definitively differentiated in the formative phases of the Plantationocene that occurred in Andalus (Spain) and coastal Peru between 1300 and 1800. These Plantationocene pathways arose through the effects of Castilian colonialism, struggles of several subaltern populations, multi-scale geographic movements, influential historical precursors, and the affordances provided by diverse and partially shared suites of differentiated food biota and landscapes.

Finally, our conclusion offers implications for current agri-food alternatives. Dynamic historical entanglements – rather than presentist assumptions or equilibrium ecologies – characterize Plantationocene pathways and alternatives. Here we highlight many diverse foods whose agrobiodiversity is vital to current alternatives (e.g. peasant or indigenous agri-food systems) that trace to the transformations of Plantationocene histories and geographies. Affordance characteristics of diverse food biota take shape through multi-scale, non-local entanglements. Place-specific agri-food systems in this study were influenced by nonlocal connectivity that continue to condition diverse-food alternatives. Finally, the coloniality of racialized, precarious labor remains common in alternative agriculture (e.g. examples of organic and ecological agriculture or Protected Denomination of Origin production). The ongoing entanglement of diverse-food alternatives with colonial-type labor urges social justice approaches. Together, these insights support the use of entanglement and affordance concepts to analyze the current alternatives that characterize and give hope in the Plantationocene.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (90.2 KB)Acknowledgements

This research was initiated in 2018 with funding to the first author by the Spain Fulbright Commission (2017–2019) that is gratefully acknowledged. It benefitted from the logistical guidance and scholarly insights of Yolanda Jimenez Olivencia and Carmen Trillo San José at the Universidad de Granada. Initial results were presented in 2019 at the International Congress of Environmental History Organizations in Florianópolis, Brazil, where feedback was provided by Judith Carney, Chris Duvall, Claudia Leal, Karl Offen, Richard Rosomoff, and Case Watkins. Funds for the second phase of research were provided by the E. Willard & Ruby S. Miller professorship (2019–2022) in the Department of Geography at Pennsylvania State University. José Luis Rodriguez Toledo assisted with the bibliographic and archival research in Peru. Stephanie O. Yépez made the maps. Magdalena Chocano shared insights. Research project and paper development between 2017 and 2023 benefitted from ongoing discussion with Medora Ebersole. Presentation of the near-final version of the paper received helpful feedback at the Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers in January 2023.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karl S. Zimmerer

Karl S. Zimmerer is Professor of Environment-Society Geography, Rural Sociology, and Ecology and directs the GeoSyntheSES Collaboratory at Pennsylvania State University. His research focuses on the political and social ecologies of food, agriculture, biodiversity, urbanization/migration, and climate change. His current projects address monocultures and diverse food in the Western Mediterranean (1990-present) (Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene), landscape connectivity and resilience in agri-food systems in Spain (Agricultural Systems, 2022), sustainability and resilience of informal seed systems in an 11-country study of poverty, precarity and peri-urban spaces of the Global South, immigrant farmworkers in peri-urban Spain, and present-day food strategies and biodiversity-nutrition dynamics of Indigenous and peasant communities. Since 2016 his research is allied with the Granada-based Foodscapes Project and the Instituto de Investigación Nutritional in Peru. Karl's current projects include collaborators at Penn State, in Peru, and at the University of Montpellier, CIRAD, and CNRS in France. He is Editor-in-Chief of Urban Agriculture.

Ramzi M. Tubbeh

Ramzi M. Tubbeh is a Lecturer at Lincoln University in Canterbury, New Zealand, with expertise in political ecology, agrarian political economy, and postcolonial studies. He has been appointed as a postdoctoral scholar at the GeoSyntheSES Collaboratory at Pennsylvania State University where he undertook research for this study. His areas of research include landbased rural livelihoods, water governance, conservation, agrobiodiversity and climate change, with a geographical focus on coastal, mountain, and rainforest landscapes in the tropical Andes. His recent work is focused on (1) indigenous communal land titling and forest conservation programs; (2) the impacts of large hydraulic infrastructures and associated water governance systems on agricultural landscapes and livelihoods; and (3) the relationship between community-based irrigation systems, landscape knowledge, and smallholding farmers' resilience.

Martha G. Bell

Martha G. Bell is an Associate Professor of Geography and Environment in the Department of Humanities at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (PUCP). Her research focuses on Peru and the Andes, which she studies from a historical political ecological perspective, with publications on colonial agriculture and water use. Her most recent project considers local and cultural knowledge production on disasters in the context of El Niño flooding in the coastal and upland areas of Piura, Peru. Other recent research analyzes the expansion of intensive commercial agriculture in the context of surrounding geographic spaces of natural areas and smallholder agriculture. Martha has also collaborated on interdisciplinary projects studying historical landscape models, historical linguistics and mapping, and urban agriculture. She currently serves as Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Latin American Geography.

Notes

1 Andalus is a regional term for this territory since between 1300 and 1800 it overlapped with the Arabic designation of Al-Andalus and later that of Andalucía in early modern Spain. Use of the term Andalus highlights continuities during the 1300–1800 period including diverse peasant groups (see text).

2 Mudejares were Muslims allowed to stay in conquered territories. They were known as Moriscos after Christian conversion, often by force, though often more apparent than real.

3 In the Kingdom of Valencia, place-specific taxes for settler-peasants rarely exceeded a fifth of the harvest, but Mudejares and Moriscos paid roughly one third to one half of harvest (Torró Citation2009).

4 Compulsory sugar cane sharecropping existed in Nasrid nobles’ estates prior to Castilian colonization (Trillo San José Citation2004; Lagardere Citation1995).

References

- AGN (Archivo General de la Nación, Lima). 1594. Testimonio de la visita y composición que hizo en las tierras del valle de Santa el Maestro Fray Domingo de Valderrama. Sección: Campesinado, Derecho Indígena, Legajo 31, Cuaderno 620.

- AGN (Archivo General de la Nación, Lima). 1594–1597. Título y composición de las tierras de Carva o Cauva. Sección: Campesinado, Títulos de propiedad, Legajo 2, Cuaderno 49.

- Agresta, Abigail. 2021. “Humans and the Environment in Medieval Iberia.” In The Routledge Hispanic Studies Companion to Medieval Iberia. Unity in Diversity, edited by E. Michael Gerli and Ryan D. Giles, 3–18. London and New York: Routledge.

- Al-Awwam, Yahyá Ibn Muhammad. [1100s] 1988. Libro de Agricultura. Volumes 1–2. Originally translated by J.A. Banqueri (1802). Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, Secretaría General Técnica.

- Aldana Rivera, Susana. 1988. Empresas Coloniales: Las Tinas de Jabón En Piura. Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos.

- Alfaro y Lariva, Manuel D. 1870. Tratado Teó rico Prá ctico de Agricultura, Seguido de Los Reglamentos de Aguas de Los Valles de Lima y Chancay. Lima: Casa del autor.

- Andersson, E., and T. McPhearson. 2018. “Making Sense of Biodiversity: The Affordances of Systems Ecology.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00594.

- Angé, Olivia, Adrian Chipa, Pedro Condori, Aniceto Ccoyo Ccoyo, Lino Mamani, Ricardo Pacco, Nazario Quispe, Walter Quispe, and Mariano Sutta. 2018. “Interspecies Respect and Potato Conservation in the Peruvian Cradle of Domestication.” Conservation and Society 16 (1): 30–40.

- Azuar Ruiz, Rafael. 1998. “Espacio hidráulico y ciudad islámica en el Vinalopó. La Huerta de Elche.” In Agua y Territorio. I Congreso de Estudios Del Vinalopó, edited by María Carmen Rico Navarro, 11–31. Petrer: Centro de Estudios Locales del Vinalopó.

- Bartet, Leyla. 2005. Memorias de cedro y olivo: La inmigración Árabe Al Perú: (1885–1985). Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú.

- Barua, Maan. 2023. “Plantationocene: A Vegetal Geography.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 113 (1): 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2094326.

- Bassett, Thomas J., Moussa Koné, and William Munro. 2022. “Bringing to Scale: The Scaling-Up Concept in African Agricultural Value Chains.” African Studies Review 65 (1): 66–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2021.83.

- Bell, Martha G. 2015. “Historical Political Ecology of Water: Access to Municipal Drinking Water in Colonial Lima, Peru (1578–1700).” Professional Geographer 67 (4): 504–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2015.1062700.

- Bell, Martha G. 2018. “‘Wheat is the Nerve of the Whole Republic’: Spatial Histories of a European Crop in Colonial Lima, Peru (1535–1705).” Journal of Historical Geography 59: 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2017.10.002.

- Bermejo, Hernández, J. Esteban, and Expiración García Sánchez. 1998. “Economic Botany and Ethnobotany in Al-Andalus (Iberian Peninsula: Tenth-Fifteenth Centuries), an Unknown Heritage of Mankind.” Economic Botany 52 (1): 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02861292.

- Butzer, Karl W. 2005. “Environmental History in the Mediterranean World: Cross-Disciplinary Investigation of Cause-and-Effect for Degradation and Soil Erosion.” Journal of Archaeological Science 32 (12): 1773–1800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.06.001.

- Butzer, Karl W., Juan F. Mateu, Elisabeth K. Butzer, and Pavel Kraus. 1985. “Irrigation Agrosystems in Eastern Spain: Roman or Islamic Origins?” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 75 (4): 479–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1985.tb00089.x.

- Capparelli, A., V. Lema, M. Giovannetti, and R. Raffino. 2005. “The Introduction of Old World Crops (Wheat, Barley and Peach) in Andean Argentina during the 16th Century AD: Archaeobotanical and Ethnohistorical Evidence.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 14 (4): 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-005-0093-8.

- Caramanica, Ari, Luis Huaman Mesia, Claudia R. Morales, and Gary Huckleberry. 2020. “El Niño Resilience Farming on the North Coast of Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117 (39): 24127–24137. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006519117.

- Cárdenas Ayaimpoma, Mario. 2014. La población aborigen en Lima colonial. Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú.

- Carmona Ruiz, María Antonia. 2018. “La transformación de los paisajes rurales en el valle del Guadalquivir tras la conquista cristiana (Siglo XIII).” In Trigo y Ovejas: El Impacto de Las Conquistas En Los Paisajes Andalusíes (Siglos XI–XVI), edited by Josep Torró and Enric Guinot, 93–117. Valencia: Universitat de Valencia.

- Carney, Judith A. 2003. Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Carney, Judith A. 2021. “Subsistence in the Plantationocene: Dooryard Gardens, Agrobiodiversity, and the Subaltern Economies of Slavery.” Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (5): 1075–1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1725488.

- Carney, Judith A., and Richard N. Rosomoff. 2011. In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. Berkeley and Los Angles: University of California Press.

- Carolan, Michael. 2018. “Justice Across Real and Imagined Food Worlds: Rural Corn Growers, Urban Agriculture Activists, and the Political Ontologies They Live By.” Rural Sociology 83 (4): 823–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12211.

- Chao, Sophie, Wendy Wolford, Andrew Ofstehage, Shalmali Guttal, Euclides Gonçalves, and Fernanda Ayala. 2023. “The Plantationocene as Analytical Concept: A Forum for Dialogue and Reflection.” Journal of Peasant Studies, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2023.2228212.

- Chocano, Magdalena. 2020. Población, producción agraria y mercado interno, 1700–1824. In Economía del período colonial tardío, edited by C. Contreras. Lima: BCRP and IEP.

- Cieza de León, Pedro. [1553] 1984. Crónica del Perú. Primera parte. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Fondo Editorial: Academia Nacional de la Historia.

- Cobo, Bernabé. [1639] 1935. “Historia de La Fundación de Lima.” In Monografías históricas sobre la ciudad de Lima. Tomo 1, 4–317. Lima: Libería e Imprenta Gil.

- Cobo, Bernabé. [1653] 1956. Historia del Nuevo Mundo. Madrid: Atlas.

- Cushner, Nicholas. 1980. Lords of the Land: Sugar, Wine, and Jesuit Estates of Coastal Peru, 1600–1767. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Cutright, Robyn E. 2015. “Eating Empire in the Jequetepeque: A Local View of Chimú Expansion on the North Coast of Peru.” Latin American Antiquity 26 (1): 64–86. https://doi.org/10.7183/1045-6635.26.1.64.

- Dargent, Eduardo. 2017. Historia del azúcar y sus derivados en el Perú. Lima: Universidad Ricardo Palma.

- Davis, Janae, Alex A. Moulton, Levi Van Sant, and Brian Williams. 2019. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, … Plantationocene?: A Manifesto for Ecological Justice in an Age of Global Crises.” Geography Compass 13 (5): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12438.

- de Herrera, Gabriel Alonso. [1513] 1818. Obra de agricultura. Madrid: Real Sociedad Económica Matritense.

- de la Vega, Garcilaso. [1609] 1976. Comentarios reales de los Incas. Edited by Aurelio Miró Quesada. Ayacucho: Fundación Biblioteca Ayacucho.

- Deneven, William M. 2001. Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Diez, Concepción M., Isabel Trujillo, Nieves Martinez-Urdiroz, Diego Barranco, Luis Rallo, Pedro Marfil, and Brandon S. Gaut. 2015. “Olive Domestication and Diversification in the Mediterranean Basin.” New Phytologist 206 (1): 436–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13181

- Dillehay, Tom D., Alan Kolata, and Charles Ortloff. 2023. “Chimú-Inka Segmented Agricultural Fields in the Jequetepeque Valley, Peru: Implications for State-Level Resource Management.” Latin American Antiquity, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13181.

- Dunmire, William W. 2004. Gardens of New Spain: How Mediterranean Plants and Foods Changed America. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Espinoza Claudio, César. 2019. “Alteraciones climáticas, haciendas y vida social de los negros esclavos y libertos en Piura: 1791–1823.” Investigaciones Sociales 22 (42): 181–204. https://doi.org/10.15381/is.v22i42.17488.

- Fábregas García, Adela. 2018. “Commercial Crop or Plantation System? Sugar Cane Production from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic.” In From Al-Andalus to the Americas: (13th-17th Centuries), edited by Thomas F. Glick, Antonio Malpica Cuello, Félix Retamero, and Josep Torró, 301–331. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

- Flores-Zúñiga, Fernando. 2008. Haciendas y pueblos de Lima. Historia del valle del Rímac (de sus orígenes al siglo XX). Tomo II. Valle de Sullco y Lati: Ate, La Molina, San Borja, Surco, Miraflores, Barranco y Chorrillos. Lima: Congreso del Perú.

- Flores Galindo, Alberto. 1984. Aristocracia y plebe: Lima, 1760–1830. Lima: Mosca Azul.

- Gade, Daniel W. 2015. “Particularizing the Columbian Exchange: Old World Biota to Peru.” Journal of Historical Geography 48: 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2015.01.001.

- Galloway, J. H. 1977. “The Mediterranean Sugar Industry.” Geographical Review 67 (2): 177. https://doi.org/10.2307/214019.

- García Sánchez, E. 1988. “Los cultivos de Al-Andalus y su influencia en la alimentación.” In Aragón vive su historia: actas de las II Jornadas Internacionales de Cultura Islámica, edited by Ediciones Al-Fadila, 183–195. Teruel: Instituto Occidental de Cultura Islámica.

- García Sánchez, Expiración. 1995. “Caña de azúcar y cultivos asociados En Al-Andalus.” In Paisajes del Azúcar: Actas del Quinto Seminario Internacional Sobre La Caña de Azúcar, Motril, 20–24 de Septiembre de 1993, edited by Antonio Malpica Cuello, 41–68. Motril: Diputación Provincial de Granada.

- García Sánchez, E. 2011. “La producción frutícola en al-Andalus: un ejemplo de biodiversidad.” Estudios Avanzados 16 (16): 51–70.

- García Sánchez, E. 2019. “Plantas alimentarias en al-Andalus y su expansión a través del Atlántico.” In Problemas del pasado americano. Tomo 2. Colonización y religiosidad, edited by Dora Sierra Carrillo, 59–82. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

- Glick, Thomas F. 2005. Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages. Leiden: Brill.

- Guinot Rodríguez, Enric. 2018. “La construcción de nuevos espacios agrarios en el siglo XIII. Repartimientos y parcelarios de fundación en el Reino de Valencia: Puçol y Vilafamés.” In Trigo y Ovejas: El impacto de las conquistas en los paisajes Andalusíes (Siglos XI–XVI), edited by Josep Torró and Enric Guinot Rodríguez, 119–160. Valencia: Universitat de Valencia.

- Haraway, Donna. 2015. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6 (1): 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934.

- Horden, Peregrine, and Nicholas Purcell. 2000. The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Inskip, S., G. Carroll, A. Waters-Rist, and O. López-Costas. 2019. “Diet and Food Strategies in a Southern al-Andalusian Urban Environment During Caliphal Period, Écija.” Sevilla. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11 (8): 3857–3874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0694-7.

- Jiménez-Ruiz, Jaime, Jorge A. Ramírez-Tejero, Noé Fernández-Pozo, María de la O. Leyva-Pérez, Haidong Yan, Raúl de la Rosa, Angjelina Belaj, et al. 2020. “Transposon Activation is a Major Driver in the Genome Evolution of Cultivated Olive Trees (Olea europaea L.).” The Plant Genome 13 (1): e20010. https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20010.

- Jiménez de la Espada, Marcos. 1881. Relaciones Geográficas de Indias - Perú (Tomos 183–185). Edited by José Urbano Martínez Cárdenas. Madrid: Ministerio de Fomento.

- Keith, Robert. 1976. “Origen Del Sistema Hacienda. El Valle de Chancay.” In Hacienda, Comunidad y Campesinado En El Perú, edited by José Matos Mar, 53–104. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Kirchner, Helena. 2021. “Introduction. Research on Irrigation, Drainage, Dry Agriculture, and Pastures in Al-Andalus.” In Agricultural Landscapes of Al-Andalus, and the Aftermath of the Feudal Conquest, edited by Helena Kirchner, and Flocel Sabaté, 11–28. Turnhout: Brepol.

- Klaren, Peter F. 2005. “The Sugar Industry in Peru.” Revista de Indias 65 (233): 33–48.

- Kneas, David. 2021. “Cattle in the Cane: Class Formation, Agrarian Histories, and the Temporalities of Mining Conflicts in the Ecuadorian Andes.” Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (4): 754–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1762180.

- Lagardere, Vincent. 1995. “Les Contrats de Culture de La Canne a Sucre a Almuñecar et Salobreña Aux XIII et XIV Siecles.” In Paisajes Del Azúcar: Actas Del Quinto Seminario Internacional Sobre La Caña de Azúcar, Motril, 20–24 de Septiembre de 1993, edited by Antonio Malpica Cuello, 69–79. Granada: Diputación Provincial de Granada.

- la Parra López, Santiago. 1995. “Un Paisaje Singular: Borjas, Azúcar y Moriscos En La Huerta de Gandía.” In Paisajes Del Azúcar: Actas Del Quinto Seminario Internacional Sobre La Caña de Azúcar, Motril, 20–24 de Septiembre de 1993, edited by Antonio Malpica Cuello, 117–171. Granada: Diputación Provincial de Granada.

- Lockhart, J. 1994. Spanish Peru, 1532–1560: A Social History. 2nd Edn. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- López, Esteban, and Félix Retamero. 2017. “Segregated Fields. Castilian and Morisco Peasants in Moclón (Málaga, Spain, Sixteenth Century).” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21 (3): 623–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0390-1.

- López Morales, Humberto. 1990. “Orígenes de la caña de azúcar en Iberoamérica.” In La Caña de Azúcar En Tiempos de Los Grandes Descubrimientos (1450–1550). Actas Del Primer Seminario Internacional, 189–208. Motril: Junta de Andalucía.

- Macera, Pablo. 1966. “Instrucciones para el manejo de las haciendas jesuitas del Perú (SS. XVII–XVIII).” Nueva Crónica 2 (2): 1–127.

- Malpica Cuello, Antonio. 1990. “La Cultura Del Azúcar En La Costa Granadina.” In La Caña de Azúcar En Tiempos de Los Grandes Descubrimientos, 1450-1550. Actas Del Primer Seminario Internacional, 189–207. Motril: Ayuntamiento de Motril.

- Malpica Cuello, Antonio. 2018. “The Kingdom of Granada: Between the Culmination of a Process and the Beginning of a New Age.” In From Al-Andalus to the Americas (13th–17th Centuries), edited by Thomas F. Glick, Antonio Malpica Cuello, Félix Retamero, and Josep Torró, 383–400. Leiden: Brill.

- Malpica Cuello, Antonio, and Carmen Trillo San José. 2002. “La Hidráulica Rural Nazarí. Análisis de Una Agricultura Irrigada de Origen Andalusí.” In Asentamientos Rurales y Territorio En El Mediterráneo Medieval, edited by Carmen Trillo San José, 221–262. Athos-Pérgamos: Granada.

- Manrique, Nelson. 1993. Vinieron Los Sarracenos: El Universo Mental de La Conquista de América. Lima: DESCO.

- Martínez-Moreno, Fernando, José Ramón Guzmán-Álvarez, Concepción Muñoz Díez, and Pilar Rallo. 2023. “The Origin of Spanish Durum Wheat and Olive Tree Landraces Based on Genetic Structure Analysis and Historical Records.” Agronomy 13 (6): 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13061608

- Martínez Enamorado, Virgilio. 2010. “Repartimientos Castellanos Del Occidente Granadino y Arqueología Agraria: El Caso de Torrox.” In Por Una Arqueología Agraria. Perspectivas de Investigación Sobre Espacios de Cultivo En Las Sociedades Medievales Hispánicas, edited by Helena Kirchner, 173–184. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- McKittrick, Katherine. 2013. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17 (3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13061608.

- Mejía Xesspe, M. T. 1931. “Kausay. Alimentación de Los Indios.” Wira Kocha. Revista Peruana de Estudios Antropológicos 1 (1): 9–24.

- Molina, Molina, Ángel Luis, and María del Carmen Veas Arteseros. 2009. “Situación de Los Mudéjares En El Reino de Murcia (Siglos XIII–XV).” Áreas. Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales 14: 93–105. https://revistas.um.es/areas/article/view/84621.

- Moragues, Marc, Marian Moralejo, Mark E. Sorrells, and Conxita Royo. 2007. “Dispersal of Durum Wheat [Triticum turgidum L. ssp. turgidum convar. durum (Desf.) MacKey] Landraces Across the Mediterranean Basin Assessed by AFLPs and Microsatellites.” Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 54 (5): 1133–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-006-9005-8.

- Morales Muñiz, A., M. Moreno García, E. Roselló Izquierdo, L. Llorente Rodríguez, and D. Morales Muñiz. 2011. “711 Ad: ¿El Origen de una Disyunción Alimentaria?” Zona Arqueológica 15: 303–322.

- Moreno Moreno, Ana. 2020. “Trapiche o Ingenio de Azúcar de Jimena de La Frontera.” Meridies: Estudios de Historia y Patrimonio de La Edad Media 11: 15–37. https://doi.org/10.21071/meridies.vi11.12241

- Murphy, Michael Warren, and Caitlin Schroering. 2020. “Refiguring the Plantationocene.” Journal of World-Systems Research 26 (2): 400–415. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2020.983.

- Nading, A. M. 2013. “Humans, Animals, and Health: From Ecology to Entanglement.” Environment and Society 4 (1): 60–78. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2013.040105.

- Nally, David, and Gerry Kearns. 2020. “Vegetative States: Potatoes, Affordances, and Survival Ecologies.” Antipode 52 (5): 1373–1392. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12652.

- Neely, A. H. 2021. “Entangled Agencies: Rethinking Causality and Health in Political-Ecology.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 4 (3): 966–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848620943889.

- Offen, Karl. 2004. “Historical Political Ecology: An Introduction.” Historical Geography 32 (2004): 19–42.

- Palomino, Guzman, L. E, Guillén Guillén, and M. Maticorena Estrada. 1996. Tambogrande y la historia de Piura en el Siglo XVI. Piura: Centro de Estudios Histórico-Militares del Perú and Municipalidad distrital de Tambogrande.

- Peña-Chocarro, Leonor, Guillem Pérez-Jordà, Natàlia Alonso, Ferran Antolín, Andrés Teira-Brión, João Pedro Tereso, Eva María Montes Moya, and Daniel López Reyes. 2019. “Roman and Medieval Crops in the Iberian Peninsula.” Quaternary International 499: 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2017.09.037.

- Pérez-Mallaína, Pablo E. 2000. “La Fabricación de Un Mito: El Terremoto de 1687 y La Ruina de Los Cultivos de Trigo En El Perú.” Anuario de Estudios Americanos 57 (1): 69–88. https://doi.org/10.3989/aeamer.2000.v57.i1.259.

- Pérez Vidal, José. 1973. La Cultura de La Caña de Azúcar En El Levante Español. Madrid: Instituto Miguel de Cervantes.

- Phillips, William D. 2013. Slavery in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Quilter, Jeffrey. 2020. Magdalena de Cao: An Early Colonial Town on the North Coast of Peru. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

- Rangan, Haripriya, Judith Carney, and Tim Denham. 2012. “Environmental History of Botanical Exchanges in the Indian Ocean World.”.” Environment and History 18 (3): 311–342. https://doi.org/10.3197/096734012X13400389809256.

- Red Andaluza de Semilla. 2022. “La XIX Feria Andaluza de La Biodiversidad Agrícola Será Retrasmitida En Vivo.” 2022. https://www.redandaluzadesemillas.org/noticias/la-xix-feria-andaluza-de-la-biodiversidad-agricola-sera-retrasmitida-en-vivo.