ABSTRACT

We present an empirically-grounded exploration of food sovereignty among Brazilian Amazonian forest-proximate peoples, revealing five dimensions bound together by autonomy: family farming, women's work, agrobiodiversity, care for nature and a preference for own produced over industrial food. We examine the compatibility of this conceptualisation of Amazonian food sovereignty with Brazil’s National School Feeding Program (PNAE). We find that in supporting family farming and local food for children, the PNAE fosters food sovereignty, but inclusion remains uneven, shaped by unequal recognition and over-centralization. The PNAE could further the actualisation of Amazonian food sovereignty by more equal inclusion of different forest-proximate peoples.

1. Introduction

This paper presents an empirically-grounded conceptualisation of food sovereignty among Brazilian Amazonian forest-proximate peoples.Footnote1 It consists of five dimensions: family farming; women’s work; agrobiodiversity; care for nature; and a preference for own produced over industrial food. What characterises all five dimensions is autonomy, which we show to be the common thread linking them together. We examine the extent to which Amazonian food sovereignty – conceived of in this way – can be supported by Brazil’s National School Feeding Program (PNAE), which aims to ensure that children at indigenous peoples and traditional communities’ schools are fed healthy and culturally appropriate foods by purchasing one-third of its food from local family farmers whilst recognising their importance in preserving the country's food and cultural diversity (BRASIL Citation2020). In promoting the purchase of traditional foods directly from communities for school meals, the PNAE provides a more nutritious and diverse diet for students, strengthening family income and contributing to the local economy (MPPA Citation2023). Understanding what constitutes food sovereignty among Amazonian forest-proximate peoples and how this relates to the actual and potential support the PNAE can provide is crucially important to address chronic food insecurity. Seventy percent of households are food-insecure in Brazil’s two largest Amazonian states, Pará and Amazonas (IBGE Citation2020), and the country has recently returned to the FAO hunger map (Guedes Citation2022).

We ask, to what extent is the PNAE fostering food sovereignty among Amazonian forest-proximate peoples? To answer this question, it is necessary to understand the diversity of food systems and family farming among these different groups. So, we ask three sub-questions: (i) which food systems characterise different social groups and corresponding territorial units in Amazonia; (ii) how does each group understand ‘food sovereignty’? (iii) what do different social groups think of the PNAE, and how successful is its implementation?

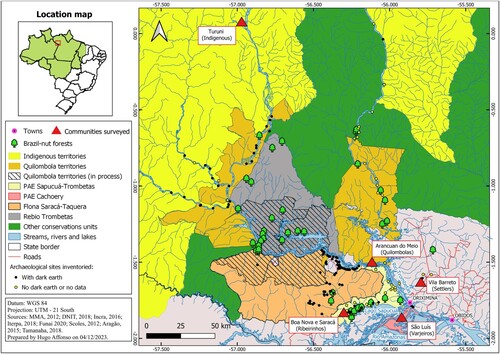

We present a case study of Oriximiná municipality, located in Pará state, Brazilian Amazonia, which provides an excellent environment to explore these questions: it has a PNAE programme implemented by local government and supported by NGOs. The region is home to five self-identifiedFootnote2 groups of people that inhabit distinct forms of territorial unit, broadly analogous to those found elsewhere in Brazilian Amazonia. These are: indígenas Tunayana (an indigenous people) and their territorial unit the terra indigena (TI) Kaxuyana-Tunayana; quilombolas (Afro-descendant peoples) whose territory is terra quilombola (TQ) Trombetas; ribeirinhos (riverside dwellers) whose territory is the Agro-Extractivist Settlement Project (PAE) Sapucaia-Trombetas and varjeiros (floodplain dwellers) who reside in PAE Cachoeiry, and colonos (settlers who arrived in the last 25 years, from Óbidos, a municipality close to Oriximiná) who live on a privately owned property (). Our focus on these five self-identified social groups and their corresponding territorial units allows us to be examine our questions at regional scale and also to give greater visibility to the latter three more ‘invisible’ forest-proximate peoples, too often omitted in Amazonian research compared to the former two who tend to have greater rights and recognition, in the Brazilian Constitution, in media and academia, and in terms of NGO assistance (Forest Peoples Program Citation2013; Fraser Citation2018).

Figure 1. Locations of the five communities sampled, territories and conservation units, and domesticated landscapes in Oriximiná municipality, Brazilian Amazonia.

We find a convergent understanding of food sovereignty amongst the five social groups investigated, despite distinct identities and territorial units. This emerges from our ethnographic and survey work but is also consonant with the literature that we examine in section 3.1. The most salient characteristic is autonomy, which links five dimensions of food sovereignty together: family farming featuring collective labour mobilised through kinship networks with a centrality of women’s work in agrobiodiverse food systems where species and landraces circulate between families with little to no use of chemical fertilisers or credit. Food systems are rendered sustainable by caring for nature, in particular concepts of abundance and tiredness guiding decisions to not overexploit, and to let areas that have been cultivated rest in order to recuperate them. Finally, all groups expressed a preference for own produced over industrial food.

Understood in terms of these five dimensions, linked by autonomy, food sovereignty can clearly be fostered by the PNAE. This is because it supports ecologically-friendly family farming with a centrality of women’s work in providing locally produced non-industrial food to school children. The five groups were all positive about the PNAE, their criticisms relate to its inadequate functioning. Inclusion in the PNAE – both schools receiving food and farmers in providing it – remains uneven, shaped by unequal recognition and over-centralization. To realise tropical forest food sovereignty, we advocate for improved implementation and expansion of the PNAE, including greater participation and decision-making power for forest-proximate peoples. This can help to ensure that the programme benefits those who rely on forest resources for their livelihoods and sustenance and that their traditional knowledge and food systems are valued and preserved.

This paper is structured into six sections. Section two outlines food sovereignty and its relationship to food security, both in Brazil and internationally, along with their relationship to the PNAE. Section three presents our conceptual framework, methodology and case study. Section four analyses the five groups’ understandings of tropical forest food sovereignty, finding a convergence on the five key dimensions linked by autonomy, these are subsequently examined in turn. Section five examines the extent to which the PNAE can contribute to Amazonian food sovereignty when conceived in this way, also looking at perspectives from the different social groups on the PNAE and at whether its implementation in Oriximiná has been successful on its own terms. Section six comprises our concluding discussion.

2. Food sovereignty, food security, and the Brazilian national school feeding program.

We depart from the understanding that food is a ‘total social fact,’ meaning it articulates ‘different dimensions of human experience on multiple technical, ethical, aesthetic, political and classificatory levels’ (Benemann et al. Citation2023, 2). Food is central to all societies, linked to many kinds of activity and infinitely meaningful. It is a nexus unifying diverse social phenomena into one coherent domain (Counihan Citation2000). Food therefore has symbolic and social meanings beyond material value, embedded in social structures reflecting broader social, economic, and political relationships. Researching food systems, therefore, requires an expansive approach analysing not only production processes, but also processing, preparation, distribution and consumption, along with symbolic, spiritual, religious and aesthetic aspects (Benemann et al. Citation2023, 2).

It is from this broad perspective that we seek to examine how different peoples’ practices and discourses involving food shape what they think of the PNAE, and how they conceive of ‘food sovereignty’ and ‘food security.’ These two concepts provide distinct but overlapping normative framings of what constitutes a ‘good’ food system. While at the international level food sovereignty and food security are divergent concepts, in Brazil the idea of food sovereignty has partially radicalised the notion of food security. Hence, whilst we foreground the concept of food sovereignty to communicate clearly to an international audience, we also use it in tandem with the radicalised concept of food security in recognition of its particular meaning with the Brazilian sphere. In this section we draw out the resonances and dissonances between these concepts and how they relate to Brazil’s National School Feeding Program.

Food Sovereignty is internationally understood as a radical alternative to the hegemonic notion of Food Security. Whilst each advocates for the right to food, they were born of different political contexts, the former at a Via Campesina meeting in Nyéléni, Mali in 2007, the latter at the first UN World Food Conference in 1974, and represent different class interests historically in dispute, i.e. peasants, indigenous people, working classes versus capital and the state. The consequently distinct interpretations of the right to be protected from hunger have built divergent strategies for action. They differ radically in their conception of how the state should work (direct vs representative democracy) and of what ownership of the means of agricultural production should look like (i.e. empowering small farmers vs business-as-usual) (Hoyos and D'Agostini Citation2017).

In Brazil, the idea of food sovereignty emerged from debates among researchers, social movements and public policy makers from the 1970s onwards, centring on the increasingly apparent contradictions of food security discourse at the time. Criticism focused on how food availability and access were used by the state to maintain structures of social control and advance the interests of capital (Silva Citation2020). Against this, the idea of food sovereignty was used to emphasise the need for autonomy, better living and working conditions for peasants (Silva Citation2020). In the early 2000s, accompanying advances in public policy and social mobilisation, the concept of food security was reformulated, incorporating ideas from food sovereignty, nutritional security and the right to adequate and healthy food (see Noronha et al. Citation2023, Chapter 2). In Brazil, the now common phrase ‘Food and Nutrition Security’ combines nutrition and food security. In sum, the concept of ‘food security’ in Brazil has become radicalised in a way it has not internationally.

In 2022, the National Survey of Food Insecurity in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic revealed that 33 million people had no guarantee of the minimum to eat. It showed that hunger is unequally distributed in Brazil and is most prevalent in the North and Northeast. It also showed a direct relationship between a lack of food and people’s level of education. The less access to education there is, the greater the threat of hunger, the worse childhood nutrition, and the more compromised the physical development and cognitive capacity of that child will be (Penssan Network, Citation2022). The importance of school feeding programmes to address child hunger and improve nutrition and their ability to concentrate at school in developing countries therefore cannot be overstated (e.g. Jomaa, McDonnell, and Probart Citation2011).

The National School Feeding Programme (PNAE) began in 1955, offering school meals and food and nutritional education to students at all stages of basic public education. We can distinguish a ‘new PNAE,’ beginning in 2009, when products from family farmers began to be purchased. This was the outcome of an intersectoral process in the Federal Government with broad participation of civil society through the Food and Nutrition Security Council (CONSEA), resulting in Law 11.947 of 16 June 2009. It requires 30% of the funds passed by the PNAE to states and municipalities to be invested in the direct purchase of food produced by family farming, prioritising agrarian reform settlements, traditional communities, indigenous and quilombola communities (Brasil Citation2009; REBRAE Citation2022).

More advances have come recently. In 2020, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF) recognised the particularities of food preparation, handling and storage by traditional populations, exempting them from registration, inspection and supervision (MPF Citation2020). This document also recommends that food destined for school meals should be contracted directly from traditional peoples, without intermediaries, reducing costs and logistical problems. In addition, National Fund for Educational Development (FNDE) Resolution 6/2020 stipulates that at least 75% of the food purchased under the PNAE should be fresh or minimally processed, in recognition of traditional peoples’ methods of producing, handling and preserving food.

In 2021, the Permanent Dialogue Forum ‘CatrapovosFootnote3’ was set up, made up of representatives from public bodies, civil society and coordinated by the MPF. In 2023, the FNDE issued Technical Note 3744623, allowing indigenous and traditional producers to use the Social Identification Number (NIS) when they don't have the appropriate documentation (i.e. Declaration of Aptitude [DAP] or the National Family Farming Register [CAF]). Also in 2023, the federal government amended article 14 of Law 11,947 of 2009, which regulates the PNAE. Under the new text, formal and informal groups of women in family farming will also be given priority in the sale of food under the programme: at least 50% of sales by individual rural families must be made by women (Law 14.660 of 2023).

The PNAE can help actualise food sovereignty because it encourages the production of healthy and culturally appropriate food by local people themselves, through family farming considered as agroecological or ‘organic-by-default’ in comparison with industrial agriculture. Brazil therefore offers the opportunity to explore the degree to which the state can strengthen food sovereignty. Empirical evidence has shown that state policies, including the PNAE, can foster food sovereignty elsewhere in Brazil (Wittman and Blesh Citation2017). However, the dismantling of some public policies supporting family farming began in 2014, increasing in 2016 under Temer and intensifying under the Bolsonaro government (Niederle et al. Citation2023; Sabourin, Craviotti, and Milhorance Citation2020). The election of Lula in 2022 gives hope that the PNAE and the promise it holds to achieve food sovereignty can be realised.

3. Exploring tropical forest food sovereignty: concepts, methods, case study

3.1. Conceptualising tropical forest food sovereignty

Globally, 1.6 billion forest-proximate people resided within 5km of a forest in 2012, one billion of them in the tropics (Newton et al. Citation2020). More than a billion depend on forest resources for nutrition and health, particularly in developing countries. In Brazil, this comprises some 25% of the population, around 50 million in 2012 (Vira, Wildburger, and Mansourian Citation2015). In Brazilian Amazonia, forest-proximate peoples’ livelihoods are diverse and dynamic, shaped by urbanisation, migration and remittances, multi-sited households (i.e. with urban and rural nuclei), off-farm work, and the development of public policies that govern various aspects of distinct traditional territories, including changing production systems and environmental and land regulation (Adams et al. Citation2009; Brondizio Citation2008; Eloy Citation2009; Emperaire and Eloy Citation2015; Nasuti et al. Citation2015; Padoch et al. Citation2008).

The food systems of most Amazonian forest-proximate peoples – including those of the five social groups we focus on – centre on small-scale production and family farming, including shifting cultivation, homegardens, agroforestry, the gathering of forest products, hunting and fishing in rivers and lakes, with varying proportions of food bought through the market (Cunha Citation1999; Emperaire, Van Velthen, and De Oliveira Citation2012; Hiraoka Citation1992; Hladik et al. Citation1993; Murrieta et al. Citation2006; Redford and Padoch Citation1992). These food systems are also important aspects of the identities and worldviews of forest-proximate peoples, as has been established for indigenous peoples and peasants more broadly (e.g. Kimmerer Citation2013; Mintz and Du Bois Citation2002). Hence, the continued existence of these peoples qua forest peoples is contingent on the persistence of their agri-food systems into the future.

An international policy and academic consensus that forest peoples can be effective conservationists has grown over the last few decades (Cunha and de Almeida Citation2000). It is now widely accepted that an effective and socially just way to preserve tropical forests is to ensure the continued presence of these peoples and their cultures (FAO and FILAC Citation2021; Dawson et al. Citation2021). The persistence of Amazonian peoples in collectively held and managed territories is also the most effective way of conserving the rainforest against the aggressive expansion of industrial resource extraction, a major threat to the region (Baragwanath and Bayi Citation2020). The continued existence of these peoples, their cultures and the forests they inhabit is predicated on the future viability of their food-provisioning systems, under threat from both the destructive effects of industrial extractivism (e.g. logging and mining) and the erosion of their food systems by availability of cheap industrial food (e.g. Soto-Pinto et al. Citation2022).

Many forest-proximate peoples cultivate crops and gather forest products in landscapes that bear the exploitable legacies – edible-species and anthropogenic soils – of people living there in the past. They are the stewards of these landscapes; sometimes ancestrally related to past inhabitants, sometimes not (c.f. Fraser et al. Citation2012; Fraser and Jarvis Citation2015). This relationship can be conceptualised in terms of ‘human-food feedbacks’ in tropical forests, wherein diachronic positive feedbacks between local peoples’ management of diverse species and increasing food availability points to the possibility of conserving tropical forests while guaranteeing food provisioning (Flores and Levis Citation2021, 1147).

Two common exemplars of such ‘domesticated landscapes’ in the Amazon are anthropogenic dark earths and Brazil-nut groves. Dark earths are highly fertile soils that formed at settlement sites mainly during the pre-Columbian period in the Brazilian Amazon, and are found in many other places around the world. They are often cultivated by the Amazonian peoples. Brazil-nut groves are one of the most iconic forms of cultural forest in the Amazon, providing nuts harvested by Amazonian peoples for subsistence and trade. They are associated spatially with dark earths and are also likely of anthropogenic origin (Clement et al. Citation2015).

From the epochal rupture of European colonisation forward, the human geography of the region has been transformed through the introduction of industrial extractivism (i.e rubber, modern agriculture, mining, logging, ranching). However, most forest-proximate peoples manage the forest in ways analogous to those of the pre-Columbian period (i.e. swidden-agroforestry) and have become de facto stewards of domestic landscapes that are the legacies of their pre-Columbian forebears (Junqueira et al. Citation2016; Lins et al. Citation2015). Food sovereignty therefore not only provides a way to articulate resistance and alternatives to the destructiveness of industrial extractivism, including industrial agriculture, but could also support the maintenance of biocultural diversity in tropical forests. In Brazil, biocultural diversity has also been called sociobiodiversity, a concept coined by Diegues (Citation2019) based on the notion of ethnobiodiversity.

3.2. Case study and methodology

Oriximiná municipality is well suited to exploring our research questions: it has a PNAE programme whose functioning is supported by EMATER (Technical Assistance and Rural Extension institute) and NGOs PROINDIO (the Pro-Indian Commission) and IMAFLORA (Forest and Agricultural Management and Certification Institute), the latter two focusing only on indigenous people and quilombolas. The Trombetas River has significant domesticated landscapes: high densities of anthropogenic dark earths and Brazil-nut groves (see Clement et al. Citation2015, Figures 1 and 2). The persistence of family farming systems among the five social groups surveyed is fundamental to their continued existence and, by extension, to the ‘domesticated’ landscapes they inhabit. Oriximiná municipality also forms part of the largest contiguous block of mature rainforest in Eastern Amazonia which extends far beyond municipal limits, forming the largest block of legally protected tropical forests on the planet (Pereira et al. Citation2020).

We selected the five self-identified social groups because together they represent the diversity of forest-proximate peoples, environments and forms of territorial unit present in Brazilian Amazonia today.Footnote4 This research was developed in the context of long-term ethnographic work by the authors in the region. Specifically, the first author has been working there since 2010, the second author since 2017, the third since 2013, and the fourth since 2008. For this paper, we conducted a semi-structured questionnaire survey in July and August 2019 in order to understand each groups’ food system, wider livelihood activities, understandings of food sovereignty and degree of involvement with the National School Feeding Program (PNAE). We selected interviewees using the ‘snowball method’. Based on initial conversations with the oldest residents and/or community leaders, the names of the people who would be interviewed were selected. We interviewed heads of households, typically the adult male or female present at the time of our visit. In frequent instances where both members of an adult male and female couple were present, both were interviewed together.Footnote5

We also conducted open interviews in a variety of different arenas pertaining to the PNAE with quilombolas, including with youth leaders protesting failures in the implementation of the PNAE in Oriximiná town, travelling up the River Trombetas in a food distribution boat passing from community to community. We also visited several ribeirinho communities and several quilombola schools to discuss the programme during August and September 2018. We also draw on insights from the lead author’s work as a subcontractor for IMAFLORA, collecting data on the functioning of the PNAE among participating quilombola communities. This project was granted ethics approval following a review by members of Lancaster University’s Faculty of Science and Technology Ethics Committee (no. FST17129).

4. What is tropical forest food sovereignty?

In this section we look at what food sovereignty means for forest-proximate peoples in Amazonia, based on open interviews and participant observation. We found five dimensions of tropical forest food sovereignty: family farming (4.1) women’s work (4.2); agrobiodiversity (4.3), care for nature (4.4) and a preference for own produced non-industrialised food (4.5). The thread linking these five dimensions is autonomy, which becomes apparent in the following narratives which we present now before exploring the five dimensions in detail.

When we asked people about food sovereignty, we found it to be closely linked to autonomous food production and familial and community networks of food sharing, and this was an understanding common to all groups investigated. As the settler Ozi Barreto put it:

I think that we only have sovereignty if we make the fields. It is very good for us to plant everything. Being [food] sovereign is [when] the person has a secure source of food for the family and for the community.

As a ribeirinho leader and his wife told us at Boa Nova community: ‘Nothing is better than being food sovereign. You don’t depend on buying.’ This sentiment was shared by a settler couple at Vila Barreto: ‘Depending on the market is more difficult. We have vegetables, fruits, greens. We don’t buy.’ At the São Luís varjeiro community meanwhile, a woman pointed out, ‘It’s easier here. Having our own canteiro (raised bed), we don’t need to buy. We only buy the basics.’ A quilombola at the middle Aracuan community said, ‘I think we still have fartura [plenty]. Here it is very rare not to have food. When you don’t have it, you have someone to give it [to you]. I think it’s very good.’ Another quilombola couple added, ‘It's good for us to be food secure, to value agriculture and not depend only on trade [for food].’

When asked to explain why producing your own food was preferable, answers were similar across social groups. A man in the Turuni village responded: ‘Better to produce your own food. This is why I stay in the village,’ implying that producing food is one of the key factors leading to decisions to remain in rural areas (rather than migrating to the city). The Turuni also claim that it is better to produce their own food in their own territory, because they do not like ‘white [peoples] food’, they do not want food other than that which belongs to their own culture.

In the ribeirinho community of Boa Vista, meanwhile, a man emphasised the importance of family farming for him: ‘producing [yourself] is much better, because you produce the food at home, at your family's side. If you have a job the food is bought and you are away from family.’ The ribeirinhos claim that their own production offers ‘healthier food’, which ‘you don't have to buy’, rather, ‘it’s better to sell and use the money for another need’, concluding, ‘it’s more guaranteed to have your own production, when it's necessary, we just harvest what is ours.’ In the floodplain, as the varjeiro families interviewed told us, the food they produce is fresh and ‘without poison’ (agrochemicals), and there is no need to buy it daily. There is a preference for eating own production. Following the same reasoning, the settlers of Vila Barreto state that producing their own food is ‘healthier and doesn't need to be bought’, and they like knowing it’s origin. They also highlighted the importance of ‘making [manioc] flour to [enable them to] buy other food’.

In the words of Turuni village chief and cook, Kurusi Kurumi Tunayana, ‘the most important thing is food, it is the heart of the village. In the city everything is paid for, but not here. Nature guarantees food’. Here ‘nature’ is understood as a fundamental element in food provisioning. This also underlines the importance of tenurial security, which underwrites their access to nature. Indeed, food sovereignty appears to be a key reason that people remain in the interior rather than migrate to the city. As quilombola woman Ana Maria Souza puts it:

People say they are going to live in the city. I don't. Here [in the countryside] I have water, fish, sweet potato. I can drink sugarcane juice, eat beiju (tapioca bread) and manioc flour when I want. When the sugar runs out, we cut a cane and that’s it.

Such views were shared by two settlers of Vila Barreto community: ‘It’s better to produce. If you work in the city, you only work to buy. Here we have neighbours to help whilst they don’t. We have chicken in the yard for when it’s hard.’ A couple at the Sao Luis varjeiro community expressed similar sentiments: ‘It's better to produce it ourselves. We work on our own, come rest, work again. We have cattle, we have to watch them.’ Another varjeiro made a complementary point: ‘It’s better to produce. Don't even talk to me about a job. I don't like being ordered around by others.’ Moreover, a quilombola woman emphasised the links of such autonomous family food production to social reproduction: ‘It's better to produce your own food. We feel at ease, we are close to our children. Here we farm manioc, make manioc flour, we are always close to the children.’

In sum, a shared notion of food sovereignty can be discerned among the five groups (despite historical, environmental and cultural differences) that places emphasis on productive autonomy and security in obtaining food in their own territories, and being able to sell surplus (particularly of manioc flour) for cash, a condition often contrasted with food insecurity experienced in the city. They also used the term ‘security’, which we interpret to mean that food is safe for health (direct control of the production process), but also security in the sense that secure land tenure provides the basis for a continuous and stable food supply. An understanding of ‘sovereignty’ as control of the healthy origin of food predominated among interviewees irrespective of social group. Another understanding of sovereignty, highlighted in interviewees’ statements, is the control by both male and female farmers of their own work, time and rhythm. When asked, our interlocutors invariably said they preferred to produce their food directly, rather than get a job as a means of obtaining it with money: this dimension of ‘self-management’ or autonomy of work was central to responses from all social groups, along with another highly valued aspect made possible by working on land: proximity to family and community life.

What we observe among Oriximiná communities does not differ substantially from what is observed in other indigenous and peasant societies with regard to food sovereignty. The production of food is aimed at satisfying human needs, social reproduction, and territorial recognition. Food is not conceived as a commodity, rather it circulates in a reciprocal gift economy (some sold, some exchanged, some given, etc.), which guarantees food security. Thus, the motivations of our interlocutors to access the PNAE market include but go beyond the need to generate ‘income’, incorporating other values associated with the maintenance of food sovereignty, territory, and family. This section showed that, despite social and environmental differences, the people of Oriximiná hold a shared vision of food sovereignty, based on family farming, with a centrality of women’s work and management of agrobiodiversity mainly in ancestral territories wherein they engage in relations of care for nature, valuing their own produced over industrial food and preferring gift exchange with kin and neighbours to purchasing food with money. We now examine these five dimensions in turn.

4.1. Family farming

Family-farming is one of the most important sources of income for households in all five territories. Its practice is conditioned by the eco-region in which the community is located: Indigenous people, ribeirinhos and quilombolas inhabit areas of terra firme close to major waterways that often feature dark earths and Brazil-nut groves, likely owing to the attractiveness of these locales for human settlement (). The settlers inhabit an interfluvial area of terra firme relatively far from major waterbodies, lacking dark earths and Brazil-nut groves owing to sparser pre-Columbian inhabitation. Varjeiros live in the most distinct environment, the floodplain. They live in raised houses on the higher areas of the floodplain and cultivate in lower areas with seasonally inundated soils.

Of the five social groups investigated, the four occupying terra firme environments: indigenous people, quilombolas, ribeirinhos, and settlers had similar systems of food provisioning. They all focused on the shifting cultivation of manioc, Manihot esculenta, the Amazonian carbohydrate staple which is fundamental to what food is conceived to be among all groups. It is consumed in the form of farinha – toasted manioc flour – accompanied with protein in the form of fish, or bushmeat. Most also have homegardens and practice forest product gathering, fishing and hunting. Varjeiros were distinct, mainly because of the floodplain environment they live in, which offers limited opportunities for hunting and lacks dark earths and Brazil-nut groves, but offers fertile but seasonally inundated soils (whose cultivation is only possible during the dry season). The proximity to Oriximiná’s market has also made possible intensive vegetable production in raised beds.

Brazil-nut extraction and the use of dark earths for agriculture were practised by indigenous people, quilombolas, and ribeirinhos, but not varjeiros and settlers, quite simply because these ‘domesticated landscapes’ are not present in the floodplain and the interfluve where the latter two groups reside (). Dark earths were most used by the Turuni village, where all respondents said they cultivated the anthropogenic soils. In the ribeirinho communities Boa Nova and Saracá and quilombola Aracuan do Meio, around one third of informants in each reported using dark earths. Brazil-nut extraction was most prevalent among quilombolas of the Arancuan do Meio community, with 77% of those interviewed carrying out this activity. The harvesting of Brazil-nuts guarantees autonomy and quilombola participation in the regional economy. The indigenous people of Turuni village and, to a lesser extent, the ribeirinhos of the Boa Nova and Saracá communities, also use Brazil-nut groves. Indigenous, quilombolas and ribeirinhos exploited other forest products for medicine, construction and sale, but not the settlers of Vila Barreto (they are located at a distance from the forest in the middle of cattle ranches in the interfluvial terra firme hinterlands of Oriximiná) or the varjeiros of São Luis (because there is no terra firme forest in the varzea). All five groups fish throughout the year, both for subsistence and sale. Hunting is regularly practised by indigenous, quilombola and ribeirinho families interviewed.

For most people interviewed, farm production is aimed at own consumption and sale, providing funds for the purchase of clothing, medicines, school supplies for children, and the purchase of other foods. In general, all groups share food within the community, especially if it is from hunting or fishing. The five groups studied also show a pattern in terms of animal husbandry. For most families, a combination of chickens, pigs or ducks are raised. The rearing of these small animals is mainly aimed at consumption, but also as a hedge against emergencies. For example, a pig is sold in case of the illness of a family member. For the varjeiros, cattle are a savings to draw on in emergency situations.

4.2. Women’s work

In all five groups, the role of women in food sovereignty is fundamental. Women’s work is central in all the stages of food production: from cultivation and preparation, to the sale of food produced. In the production of the carbohydrate staple – manioc flour – women are involved in planting, harvesting, transport, washing, grating, pressing, crumbling, sifting, roasting and the production of tapioca starch. Women’s knowledge is also fundamental in the manioc-based foods, such as beiju (manioc bread) and tucupi (a manioc sauce). In the floodplain, it is common for women to be responsible for the production of various different kinds of vegetable.

During fieldtrips in July and August 2019, we observed this central role of women in each of the five territories surveyedFootnote6 (see photos in Appendix 2). The opening of manioc fields in the region, from the beginning of summer (June/July), is one of the most labour-intensive activities of the year. From the clearing of secondary forest to planting, women help mobilise extended family members to work, along with people from neighbourhood networks with whom relationships of mutual aid are established. Women’s work is central at all stages, from the preparation of food for the men responsible for the ‘heavy’ tasks (especially the felling of large trees) to the planting phases. Puxirums, cooperative work groups including relatives and neighbours, usually in festive spirit, have specific female roles: women are the cooks, diggers and planters, often with the help of children in the phases of work considered ‘lighter’, activities that allow the intergenerational transmission of knowledge associated to agriculture, along with social reproduction more broadly. Puxirum is a variation of mutirão, originating in the Tupi moty’rõ. Workgroups were used by all five social groups. Food provisioning is therefore mediated by this universe of relations where women’s work is central and which overlaps with social reproduction, involving reciprocity, education and organised work inside and outside the domestic group.

4.3. Agrobiodiversity

Autonomy in the agricultural practices of the communities in the territories we visited is supported by the maintenance of local agrobiodiversity, and the practice of seed exchange between people. Diverse manioc landraces are planted by and circulate among the five groups.Footnote7 Various other species are exchanged, including sweet potato, yam, banana, and pumpkin, along with fruit tree seeds appreciated by the group, and this occurs through networks of reciprocity, kinship and neighbourliness among local producers. These networks among producers do not prevent them from initially buying fruit tree seeds or seedlings in the city of Oriximiná. But once bought through the market, they are exchanged among producers, based on reciprocal relations following non-market logic. For example, ribeirinho José Domingos Rabelo planted hundreds of watermelon seeds bought in Oriximiná in a large area of dark earth. The watermelon was very productive, and he traded or gifted hundreds of new watermelon seeds to other people in the community. About ten years ago, through an agroforestry project by EMATER, José planted dozens of orange and lemon seedlings in the dark earth around his house, without chemical inputs; according to him, the fertility of the anthropogenic soil is the secret of his successful production. His annual production of citrus fruits is bountiful and seeds are distributed to other the producers in his community, strengthening the networks of reciprocity and the autonomy of agricultural production among the group. In Vila Barreto, Ozi Barreto exchanged corn after a good harvest with his brother for some manioc. In the varzea, Cristiane exchanged with her neighbour Sandra okra seeds for some pepper seeds.

Forest-proximate peoples’ food production relies on agrobiodiversity, which in turn is itself shaped by the traditional knowledge that mediates direct, daily work on the land, in waters and in forests. This knowledge is not, as Cunha (Citation2007) observes, ‘a static collection passed down from ancestors’, rather it needs to be practically reproduced in order to stay alive, to circulate among people of different generations, to be able to innovate and reinvent itself. The reciprocal networks we observed also extend to seed exchanges among different social groups surveyed, representing conduits of knowledge-exchange between groups. One example is the circulation of manioc landraces between quilombolas and indigenous Wai-Wai people in this region (Caillon, Eloy, and Le Tourneau Citation2017; Emperaire et al. Citation2021). The stimulation of production by the PNAE should also further encourage such exchanges of species and landraces, helping keep agrobiodiversity and associated local knowledge alive.

4.4. Care for nature

Here we focus on two concepts that subtend practices which underwrite the sustainability of family farming in Oriximina: (i) ‘fatigue of the land’ and the corresponding need to leave it to fallow, and (ii) ‘abundance’ (fartura) and the corresponding need not to overexploit, both of which we understand as concepts associated with ‘caring for nature’ that form part of their underlying cosmologies. We found these concepts present in all five groups.Footnote8 The traditional farming system practiced in the terra firme areas is based on shifting cultivation, requiring the fallowing of fields to restore soil fertility. Given the fatigue of the land in areas that have already been cultivated for many generations, the cultivated plots are rotated so that new crops can be planted in areas that have already been ‘rested’. There are at least three categories of cultivable areas: (i) an area that is producing (a field planted a year ago, for example), (ii) a new field, recently planted and (iii) an area in recovery or ‘resting’ – called capoeira (young fallow) or capoeirão (old fallow).

The local notion of fartura (abundance), which emerged in conversations with the five groups about food sovereignty, is present in all five groups, and refers to the quality of places, such as lakes and forests, in terms of their ability to provide abundant food to the territory. Some lakes are ‘abundant’ in fish, parts of forests are ‘abundant’ in nuts. The access of humans to this abundance, however, depends on the good relations established by them with the ‘mothers’ or ‘owners’ of these places, entities that are present in the cosmology of these groups and that demand care for these places, under the risk of penalising humans with scarcity (cf. Ferreira Citation2013; Nepomuceno Citation2017). Thus, if these concepts infuse local understandings of food sovereignty, it is achieved not only by conserving the ecological conditions of reproduction of renewable natural resources, but also by the balanced relationship with other beings that inhabit these territories and on whom permanent and stable access to food is dependant.

4.5. A preference for own produced non-industrialised food

All groups expressed a preference for own produced food, but were also reliant on processed and ultra-processed foods, to varying degrees. Even the Tuyani, who show the least demand for food from outside, who do not buy any meat, go to city markets, or small shops located nearer them, for coffee, sugar and biscuits. All the other groups buy meat, rice and beans when able, in order of priority. A record of meals consumed during the field trips of July and August 2019 show that all groups produce a significant proportion of food consumed, with indigenous and quilombolas consuming the least quantities of market produce, likely owing to a greater distance to Oriximiná.Footnote9

In the schools we visited, prior to the introduction of the new PNAE in 2009, meals were composed of processed and ultra-processed foods: oil, sugar, powdered milk, artificial juices, crackers, canned sardines, sausages, canned foods, etc. There has been an improvement in the quality of the food according to teachers and students, who also appreciate knowing the origins of food from family farming incorporated through the PNAE. A teacher explained, ‘The children like [locally produced foods such as like manioc flour and banana].’ He added, ‘And they know it’s produced by their parents … . before, it was sausage, sardines and manioc flour bought in the market without knowing its origin … it was more industrialised food, it was not local.’ And the children agreed, as one stated: ‘food [provided under the PNAE] from here [this region] is better, it is natural … food from outside [i.e. industrial food] is full of things [i.e. additives].’ This was a typical response. But children added they wanted more local fruits like acaí (Euterpe oleracea), cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum) and passion fruit (Passiflora edulis).

As stated in section 2, we conceive of food as a ‘total social fact’ that articulates with multiple aspects of social life, involving production, processing, preparation and finally, distribution and consumption (Benemann et al. Citation2023, 2). With regard to these last two aspects, it is important to note that the PNAE affects the food consumption habits of the children and adolescents of the social groups in question. As such, the PNAE can help make school a place where young people learn to value their food cultures, rather than merely a place where industrialised foods are consumed unreflectively. Since the PNAE involves the distribution of food to schools in the interior, it can help to address chronic logistical problems related to the challenges of travelling on Amazonian rivers – which have been highlighted during the historic drought of 2023.

In sum then, this section has shown that food systems among the five groups are broadly similar, with differences related to the affordances and seasonality of different environments inhabited (for instance, the presence of dark earths and Brazil-nut groves, or proximity to rivers and lakes for fishing, or the presence or absence of game, and proximity to the town of Oriximiná) (). Varjeiros are an outlier owing to the distinct environment that they inhabit, and the opportunities presented to them by their proximity to Oriximiná to engage in raised-bed cultivation.

Table 1. Overview of the land tenure, environment, and food provisioning systems of five groups.

5. To what extent does the PNAE contribute to Amazonian food sovereignty?

The first part of this section looks at how the PNAE relates to our five dimensions of food sovereignty (5.1). We then take a look at perspectives of individuals belonging to the five groups investigated (5.2) and the functioning of the programme itself (5.3).

5.1. How does the PNAE relate to five dimensions of food sovereignty?

The new PNAE of 2009 established a preference for the purchase of products from family farming, indigenous, peasant, quilombola and women’s groups (Art. 14, Law 11.947), and more recently, 50% of sales by rural families must be made by women (Law 14.660 of 2023). Hence, the PNAE values the most common way of organising food production by these social groups, autonomous family farming, based on the organised distribution of roles in the family, within the community and villages, involving people of different genders and age groups in agriculture and other productive activities, with a centrality of women’s work and overlapping with social reproduction, as observed empirically in the field and evidenced in this article. So, the PNAE can be seen to support our first two dimensions of food sovereignty, family farming and women’s work.

Forest proximate peoples’ food production relies on agrobiodiversity and traditional knowledge informing daily work on the land, in waters and in forests. This knowledge, rather than being a ‘static collection’ passed down from ancestors (Cunha Citation2007), needs to be practically reproduced in order to stay alive, to circulating among people of different generations, to be able to innovate and reinvent itself. We observed reciprocity networks involving seed exchanges among the different social groups surveyed, and this is also further evidenced in the circulation of manioc landraces between quilombolas and indigenous Wai-Wai people in this region (Caillon, Eloy, and Le Tourneau Citation2017; Emperaire et al. Citation2021). The stimulation of production by the PNAE should also further encourage such circulation of species and landraces, helping keep agrobiodiversity, our third dimension of food sovereignty, and associated local knowledge alive.

As noted, the PNAE preferentially purchases food from family farming by indigenous, quilombola and peasant groups. These groups often inhabit different kinds of ‘traditionally occupied lands’ (De Almeida Citation2004), which at a national level show significantly lower conversion of vegetation cover than their surrounding areas with other land uses according to a recent survey from 1985 to 2018 (Calaboni Citation2021). The forest-proximate peoples’ territories surveyed fall largely within the Protected Areas of Northern Pará, which together with the Protected Areas of the states of Amapá and Amazonas form the largest biodiversity corridor in the world (Pereira et al. Citation2020). The five groups investigated have inhabited these landscapes on timescales ranging from decades to hundreds of years. Their presence is consonant with the conservation of these tropical forested landscapes because they have historically developed agricultural systems and forest product extraction that work with natural cycles and maintain substantial forest cover, as we have made clear in the article. Favouring the purchase for school feeding of food produced under such conditions is a way of valuing agrobiodiversity and care for nature, our third and fourth dimensions of food sovereignty, perpetuating the aforementioned human-food feedbacks (Flores and Levis Citation2021) especially when contrasted with conditions under which industrial food is produced.

As noted in section two, we conceive of food as a ‘total social fact’ linked to various aspects of social life, involving production, processing, preparation, distribution and consumption (Benemann et al. Citation2023, 2). With regard to these last two aspects, it is important to note that the PNAE affects the food consumption habits of the children and adolescents of the social groups in question. The PNAE can help make the school a place where young people learn to value their food cultures and so bolster the final dimension of food sovereignty, the preference for non-industrial food, rather than the school being merely characterised by the unreflective daily consumption of industrialised foods.

5.2. Perspectives from the five social groups on the PNAE

As already noted, the PNAE has not yet been extended to the Tunayana community. But at the Turuni village school, chief Kurusi Tunayana said that the implementation of the PNAE programme would be ‘very good for families to sell [food], and the children to eat healthy foods.’ He added that industrialised, canned or preserved products are not appreciated by the children of his village, who prefer culturally appropriate foods (porridges, game, fish, fruit, etc.). He explained that, ‘the most important thing is food: the heart of the village. In the city everything is paid for, but not here. Nature guarantees food. Children prefer to eat nature’s food.’ According to him, the PNAE would improve the quality of the lunch, and contribute to the income of local farmers. Elzira Tunayana, health agent, points out that children do not have the habit of eating industrialised foods, and that, therefore, the implementation of the PNAE would be very welcome in the village.

We visited several quilombola schools where the PNAE was active to get perspectives on the programme. A teacher explained to us that following the introduction of the PNAE school menus in 2009, whereafter law 11.947/2009 stipulated at least 30% of the products purchased had to be from family farmers, the children are more disposed to learn and have greater motivation. They further explained that it improved the relationships between the school and the community; community members know that the school is now offering regional food to children and buying regional products. Before 2009 the food was instant and mostly industrially produced. After 2009 it became fresher, better quality and longer lasting. Food consumed now includes okra, gherkin, lime, manioc flour, banana, pumpkin, and tapioca flour.

Adeilson Viera explained how the PNAE food is essential for children to be able to participate in school:

The child may leave their house at 4 or 5 am (in the school boat). They may have nothing to eat before they leave. They have breakfast when they arrive in school at 8 am and more food at 11 am.

Like the indigenous people, the ribeirinhos of the Boa Nova and Saracá communities did not participate in the PNAE. Most ribeirinho farmers we spoke to were interested in participating in the programme but lacked necessary documentation, which at the time of interview was the Declaration of Aptitude (DAPFootnote11) for PRONAF, the National Program for the Strengthening of Family Agriculture, issued by EMATER. EMATER technicians consistently lack the resources to carry out visits to ribeirinho communities. Ribeirinhos contrasted their situation unfavourably with that of indigenous people and quilombolas, ‘those who have NGOs manage [to get the DAP] because they have help.’

Varjeiros live close to the urban centre of Oriximiná, which facilitates their inclusion in the PNAE. In São Luís community, students receive family farming products on their menu, provided by the programme. The amount of food from family farming is not enough to feed students for the entire month, however. The importance of proper storage at school for food such as bananas, vegetables and greens was highlighted as a point of attention by the interviewees. The idea of delivering products at two different times, in order to reduce the waste of rotting food, was also raised. The Vila Barreto settlers also point out that the amount of food purchased by the city hall is low.

5.3. How successful is the PNAE on its own terms?

Despite Federal Law No. 11,947/2009 stipulating that at least 30% of the resources transferred by the National Education Development Fund (FNDE), via the PNAE, to the municipality of Oriximiná should be used in the acquisition of foodstuffs from family farming, the municipality has consistently failed to achieve this percentageFootnote12. Sale of produce to the PNAE is uneven among the five groupsFootnote13 ().

Table 2. Agricultural Production for the 2019 PNAE by five social groups in Oriximiná.

Indigenous people and ribeirinhos found it more difficult to contribute to the call for foodstuffs for two reasons. DAPs are hard to obtain; EMATER is unable to meet the large demand of family farmers in the municipality of Oriximiná (see also de Moraes Citation2019 Chapter 3; Monzoni, Nicoletti, and Santos Citation2020). The other problem is distance. The indigenous community lies 235 km from Oriximiná, making it difficult to deliver family farming products to the indigenous schools. All food produced for the PNAE has to be taken to the town of Oriximiná for processing before being sent back out to the interior. However, three indigenous people transport food from their own production directly to the indigenous schools, which substantially facilitates the delivery process, in effect making their own autonomous school feeding programme in the absence of state action.

An issue shaped by unequal rights and recognition is that NGO help is extended to some groups and not others. Indigenous people and quilombolas have assistance from NGOs, whereas the ribeirinhos, varjeiros and settlers do not. NGOs reportedly compete for access to the two former groups, while ignoring the latter three. For example, the quilombolas have Comissão Pró-Índio and IMAFLORA helping them obtain DAPs, and include them in the PNAE. The ribeirinhos by contrast have only the help of the state institution EMATER.

We found greater participation in the PNAE closer to the urban centre of Oriximiná, which can be explained by the logistical difficulties in bringing and taking food to distant localities in the interior. Access to this public policy is facilitated by EMATER (catering to ribeirinhos, setters and varjeiros) and IMAFLORA (catering to quilombolas and indigenous). EMATER helps families mainly in accessing credits to encourage family farming under PRONAF, the National Program to Strengthen Family Agriculture including Agroforestry projects aimed at fruit production and/or participating in the PNAE. Indigenous and quilombolas participate in much more limited numbers, supported by IMAFLORA. Farmers participating in the programme have recurring complaints, such as delays in payment by the city hall, and the annual decrease in the amount of food requested by SEMED (the municipal education secretary).

Before the PNAE, school lunches were made up of canned foods, oil, powdered milk, rice, pasta, biscuits, sugar, salt and other processed foods. The quality of meals began to improve, according to local residents, when food from the fields of local families was incorporated, as a result of the PNAE. However, according to the majority of community members interviewed (from all five groups), the quantity is insufficient to last a month and is also considered of insufficient quality (see also Nepomuceno and Andrade Citation2019). In the second half of 2018, we accompanied the delivery of school lunches with quilombola farmers in rural public schools. Most of the schools in the municipality receive food from family agriculture, but some very little. Few farmers from the groups studied participate in the calls and provide food from their own production. And many while many schools receive this food, they do so in small quantities. Hence, while all groups participate in the PNAE, some participate more and others less. Moreover, there was a consensus that the amount of food from family farming bought by the city government is insufficient to adequately provision all schools.

We found that the main difficulties faced by forest-proximate peoples participating in the PNAE relate to logistics and compliance with regulations linked to health surveillance. Da Silva et al. (Citation2020) and Nascimento-Silva, Cavalcante, and Rêgo (Citation2022) highlight challenges faced by communities in terms of access to resources and the necessary infrastructure for the production, processing, transportation and distribution of food within the parameters established by the PNAE, which directly impacts the effective inclusion of communities in the programme. Since the PNAE involves the distribution of food to schools, it can help to address chronic logistical problems affecting commercialisation of production – related to the challenges of travelling on Amazonian rivers – which have been highlighted during the historic drought of 2023.

6. Concluding discussion

We wanted to understand the extent to which the PNAE is fostering food sovereignty among five distinct self-identified forest-proximate peoples in Brazilian Amazonia. We needed to understand the food systems that characterise each of these social groups and their territorial units. The food systems of the five groups studied are based on the management of agrobiodiversity in various environments supported by local knowledge, including concepts of abundance and tiredness, understood as forms of caring for nature. Such systems enable sustainable food production, taking advantage of the environmental affordances of the Oriximiná region, including sustainable exploitation of domesticated landscapes, dark earths and Brazil nut groves, along with floodplain and terra firme soils. This sociocultural diversity and agrobiodiversity contrasts with the social and ecological destructiveness of industrial monocultures (Perfecto, Vandermeer, and Wright Citation2019). The connection and positive influence of the PNAE on environmental and agrobiodiversity issues has already been highlighted by Redin (Citation2017).

Of the five forest proximate peoples investigated, we found differences had more to do with environmental affordances of distinct locales inhabited than substantive differences in family farming and food culture per se. Key environmental differences include presence/absence of, distance to, and abundance of: (i) dark earths and Brazil-nut groves, (ii) floodplain soils, and (iii) hunting and fishing opportunities (presence and type of rivers and lakes) (see ). Food cultures were broadly similar in the centrality of family farming, manioc as the carbohydrate staple and the reciprocal sharing of food and seeds with kin and neighbours. This is not to discount real differences, but to emphasise that the five groups are broadly similar in terms of food systems, especially when compared to industrial agriculture.

We then wanted to understand how each group conceived of ‘food sovereignty,’ what each thought of the PNAE, and how successful the implementation of the PNAE has been on its own terms. The perspectives of the five groups converged on certain shared attributes of what we term tropical forest food sovereignty: autonomously produced food that is shared among extended kin networks which also provide labour – with a centrality of women’s work and care for nature – in determinate territories (see Copeland Citation2019) wherein local knowledge and agrobiodiversity are valued and reproduced intergenerationally. Therefore, we found tropical forest food sovereignty to be composed of these five inter-related and mutually reinforcing dimensions linked by autonomy. Autonomous food production relies on the use of extended family labour and interviewees from all communities explained their motivations as both remaining independent from the market for food or agricultural inputs, and for being able to generate surpluses to sell. Another form of autonomy is the sharing of food among the extended family networks. This sharing is predicated on families producing their own food. This is linked to valuing local origin and traditional production methods of food production and underlying knowledge(s), and the valuing of production without agrochemicals, perceived as healthy for people and the environment.

This definition of tropical forest food sovereignty as spanning five dimensions of autonomy is broad enough to speak to the idea of food as a total social fact, permeating all aspects of society. We noted earlier that there is a scientific consensus that the most effective way to preserve rainforests is the continued existence of forest-proximate peoples in recognised territorial units. But their continued existence as peoples is contingent on the persistence of their food systems in particular territories, if we apprehend food as a total social fact. If their food systems and territories are replaced with industrial food accessed only through the market, they will lose a fundamental aspect of their culture. Moreover, values that lead them to act as stewards for their forested territories, such as collective labour, reciprocal exchange, and care for nature, are immanent in their food systems. Hence, tropical forest food sovereignty understood as a five-dimensional social fact reproduces values that contribute to forest conservation. If such food systems were to be replaced with reliance on the market and individual wage labour (i.e. proletarianisation), it is more likely that forest-proximate peoples would become alienated from one another and from nature, as has been the case in societies more thoroughly transformed by capitalist social relations. Or in Marxist terms, a metabolic rift would open up between people and nature (eg. Saito Citation2017). Tropical forest food sovereignty helps keep metabolic cycles intact.

Our findings support the assertion that the PNAE can support tropical forest food sovereignty conceived in this way. Our informants noted how as a school feeding programme, the PNAE is vital to make education possible: children need to be able to eat in order to concentrate and they prefer locally produced culturally appropriate food; both they and their parents valued that it was more ‘natural’, that they knew its origin, and sometimes they would even know the particular family who had produced it. When we approach food as a total social fact, fundamental in producing and reproducing culture and identity, it is clear that consumption of local produce in schools helps social reproduction, that is, it helps forest-proximate peoples reproduce themselves as cultures intergenerationally. The purchase of local produce also supports autonomy, centrally important in informants’ narratives, since it stimulates family farming production and provides income, making people less likely to become dependent on buying food through the market and wage labour.

We found however that the PNAE is not fulfilling its potential, in part due to a lack of transparency in local governance. This is associated with a failure to maintain financial inputs required by law, including sufficient money to purchase produce from local farmers, delays in payments and failure to provide adequate transportation for food. The PNAE also reflects broader problems of unequal rights and recognition. Despite all the difficulties encountered in relation to the progress of the PNAE, we recognise the great importance of this public policy which, by strengthening the traditional peoples and communities of the municipality of Oriximiná, supports food sovereignty for the groups studied. We, therefore, recommend the strengthening and expansion of this programme in Oriximiná and other places in Brazil where its application is often incomplete, as a way of fostering what indigenous peoples and traditional communities consider to be food sovereignty.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (3 MB)Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt thanks to all of the individuals and communities of Oriximiná, Pará, Brazil, who participated in our research. We would like to thank Jos Barlow for support with the N8 application and Emma Cardwell for reviewing a draft of the paper. We also thank two anonymous reviewers whose critical comments were important in helping us improve the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hugo Affonso

Hugo Affonso researches territorial conflicts in the Trombetas River region, Oriximiná, Pará, Brazil. He is a PhD candidate in the Postgraduate Programme in Amazonian Agriculture at the Federal University of Pará (PPGAA/UFPA). He holds a Master's degree in Environmental Sciences from the Graduate Programme in Natural Resources of the Amazon at the Federal University of Western Pará (PPGRNA/Ufopa).

James Angus Fraser

James Angus Fraser is a Senior Lecturer at Lancaster University, UK. His research takes a critical approach to questions of social justice, sustainable agriculture and biodiversity conservation. He holds a PhD in Environmental Anthropology from the University of Sussex and a Masters in Management of Agricultural Knowledge Systems from Wageningen University.

Ítala Nepomuceno

Ítala Nepomuceno researches socio-environmental conflicts and the governance of collective territories. She is a PhD student in the Postgraduate Programme in Social Anthropology at the Federal University of Amazonas (PPGAS/UFAM). She has a Master's degree in Environmental Sciences from the Graduate Programme in Natural Resources of the Amazon at the Federal University of Western Pará (PPGRNA/Ufopa).

Maurício Torres

Maurício Torres is a Professor at Federal University of Pará (UFPA), with a Masters and PhD in Human Geography from the University of São Paulo. His research focusses on territorial conflicts in the Amazon. He has acted as an ad hoc expert for the Federal Public Prosecutor (MPF) in dozens of land conflict cases. For over 20 years he has defended the rights of indigenous peoples and traditional communities in the Amazon. He is the author of 6 books and dozens of national and international articles.

Monique Medeiros

Monique Medeiros is Adjunct Professor at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), in the Amazon Institute for Family Farming (INEAF). She is Coordinator of the Postgraduate Programme in Amazonian Agriculture (PPGAA/UFPA). She has a PhD in Agroecosystems, in the area of Sustainable Rural Development, from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC/PPGA) with a sandwich period at the Mixed Research Unit – Actors, Resources and Territories in Development (ARTDev) – Montpellier 3 University – France (CAPES/COFECUB).

Notes

1 We borrow this term from Newton et al. (Citation2020) to embrace five distinct social groups in Brazilian Amazonia. Whilst indigenous people, quilombolas and ribeirinhos could be glossed with the term ‘forest peoples,’ varjeiros and especially settlers, cannot. This latter group – having relatively recently migrated from regions not necessarily forested – are not really a ‘forest people,’ as in being from the forest ‘culturally’ per se. The term ‘forest proximate people’ allows us to simply yet unproblematically capture all social groups in our study. The term forest-proximate people foregrounds the spatial relationship between people and forests and is an inclusive category that does not exclude certain groups on the basis of culture, ethnicity or indigeneity.

2 We use the categories ribeirinhos, quilombolas, varjeiros and colonos because these four peoples self-identified as such. The Tunayana identify themselves under the Tunayana ethnonym, but have rights as Indigenous peoples in the Brazilian constitution.

3 Catrapovos Brasil, which is national in scope, arose from the progress made at state level by the Commission for Traditional Food of the Peoples of Amazonas (Catrapoa). It was set up with the aim of ‘encouraging the adoption of traditional food in indigenous, quilombola and riverine, extractivist and caiçara communities, among others, throughout the country. In addition, the group […] is discussing the obstacles, challenges and ways of making public purchases of production from indigenous and traditional communities viable. The work aims to ensure compliance with the law that provides for the acquisition of at least 30 per cent of food products from family farming, as well as the right of indigenous peoples and traditional communities to school meals that are appropriate to their own production processes and culture.’ Information from https://www.mpf.mp.br/atuacao-tematica/ccr6/catrapovosbrasil/a-catrapovos. Accessed on 09/11/2023.

4 The indigenous community is located in Terra Indígena (TI) Kaxuyana / Tunayana, whose formal process of recognition has not yet been completed. It is located in a terra firme environment, by the river. The Arancuan do Meio quilombola community is located in the Trombetas Quilombola Territory (TQ), titled by INCRA (National Institute Of Colonization And Agrarian Reform) in 1997. The TQ Trombetas is in a terra firme environment, beside lakes and rivers. The Ribeirinho PAE Sapucuá-Trombetas (created by INCRA in 2010) includes residential areas, agricultural land, hunting and fishing areas, but large areas of historic use by this group for these activities have been enclosed by the Saracá-Taquera National Forest (FLONA), which restricts such livelihood activities in this conservation unit (Ibama Citation2002). PAE Sapucuá-Trombetas is located in a terra firme environment, beside the river Trombetas. The Varjeiro community studied is located in PAE Cachoeiry (created by INCRA in 2006). PAE Cachoeiry is known as Oriximiná’s ‘green belt’. Most of the vegetables that supply the municipality are produced in this settlement. In this várzea environment during winter, the Amazon, Trombetas and Cachoeiry rivers flood. For this reason, the varjeiros build their houses on stilts. When waters recede during the summer, the várzea soil is exposed, offering excellent fertility due to the nutrients left by the winter flood. The settlers of Vila Barreto arrived in the 2000s from Colonia São João, located in Óbidos and bought a piece of land on the BR 163 highway. The environment where Vila Barreto is located is interfluvial terra firme (see Appendix 1).

5 We interviewed six representatives of indigenous households (five men, one woman); nine representatives of quilombola households (two men, four women and three couples); ten representatives of ribeirinho households (three couples, five men, two women and two elderly men); seven representatives of varjeiro households (two married couples, three women and two men); seven representatives of settler households (six married couples and one man).

6 In the Turuni village, we saw Elzira Tunayana teaching younger women how to process manioc. In the quilombo, Ana Maria harvests her production of potatoes and washes them on the river bank, while her daughters produce beiju in the manioc processing house. In the ribeirinho community of Boa Nova, Maria seasons and divides the fish, and, in the floodplain, Cristiane takes care of her diverse production of vegetables. In Vila Barreto, Marli and her daughter work in the sieving and roasting of manioc flour, which will be sold in the future at the Oriximiná market, while her sister-in-law, Luciene Barreto, goes to the field to harvest yam.

7 The choice of varieties for planting depends on a considerable number of characteristics, in a logic that encompasses a plurality of cultivars to socioculturally specific needs, a fact that, as Torres (Citation2011) points out, would be irrational from an agribusiness perspective, based on the selection of genetic traits of high productivity for the market. For example, one of the characteristics important to the river dwellers is the ability to last a long time in the ground without rotting, as this ensures a tuber reserve for subsistence and flexibility for subsistence and flexibility for the production of flour to be sold when the time is or for the purchase of something not produced directly by the family. It is common for neighbours and/or relatives to share a variety of manioc landraces, exchanging small pieces of manioc stem (maniva) used for the cultivation of a new field. Thus, these agricultural systems and their agrobiodiversity are kept relatively autonomous from market logics

8 Although the varjeiros do not cultivate terra firme and thus do not refer to the varzea as ‘tired’ since it is replenished with nutrients each year.

9 In the Tunayana territory we ate fruit such as bananas, ingá, pineapples and lemons; pork, monkey and fish; manioc flour, manioc bread, sweet potatoes, yam, chilli pepper, sugar cane, among others. the only foods consumed during one week that were not produced by the community, or extracted from the forest and rivers, were coffee, milk and biscuits. In the quilombo territory, only coffee and biscuits were bought in the city. All the other foodstuffs, such as raw biscuits, cross potatoes, fried, boiled and roasted fish, açaí, yam, lemon, manioc flour, manioc bread and tapioca, were produced in the community itself. At the ribeirinho communities Boa Nova and Saracá of the Sapucuá lake, we ate plenty of large boiled banana, cocoa, manioc and tapioca flour, fish stews, baked fish, and deer meat given by neighbours. The consumption of beef and chicken meat, rice, biscuits, coffee and milk make up the food that was bought in town, and can also be bought in the community itself, in small shops. At São Luis community, located in the floodplain of the Cachoeiry River, we ate boiled and roasted fish, and we had more vegetables and greens at the table that in other territories, such as chives, coriander, cabbage, tomatoes, maxixe, among others produced in the community. Beef, cassava flour, biscuits and coffee were bought in the city. Hence, the varzerios diet was distinct, owing to their proximity to the city allowing them to purchase more food, and their ability to produce vegetables and greens. In the Barreto settler village, with the settlers, we consumed tapioca, manioc flour, manioc bread, sweet manioc cake, açaí, orange, jambo. Coffee, milk and beef were bought in the city.

10 In Oriximiná town we spent the day with quilombola youth leaders, who had been trained by the NGO Engajamundo which works to empower Brazilian youth to engage in political processes. They were protesting for a menu that had 50% of its ingredients from family agriculture, for logistical improvements (‘we don’t want to have to send food to the city to be administered only for it to rot before it is sent back’) and that the mayor contributes what he is supposed to, including paying for a minimum of 30% of the food as required by law, and paying for the community-organized boats which distribute food. They were being helped by Lilian Braga, Public Prosecutor of the Public Ministry of the State of Pará. She explained that the PNAE began in 2015; she understood its significance in terms of ‘traditional foods as a political act.’ But she cautioned that the PNAE can also erode traditional foods if it is not based on local food production.

11 Please note that in the current third Lula government, the DAP is now called the CAF – Family Farming Register.

12 In 2011, the municipality invested only 11%; 2012, 7%; 2013, 10%; 2014, 27%; 2016, 13%; 2017 27%. Data for subsequent years are not available (Nepomuceno and Andrade Citation2019).

13 In the PNAE public call of 2019, 50 heads of household participated, of which 33 were from the five social groups that we surveyed: 3 indigenous (all male), 14 quilombolas (six female and eight male), 3 ribeirinhos (all male), 7 settlers (two female and five male) and 6 varjeiros (four female and two male). However, of the families that we interviewed, none of the indigenous and ribeirinhos participated in the public call for foodstuff. Approximately 22% (2 respondents out of a total of 9) of quilombolas, 57% (4 respondents out of a total of 7) of varjeiros, and 71% (5 respondents out of a total of 7) of settlers benefit from this public policy.

References

- Adams, C., R. Murrieta, W. Neves, and M. Harris. 2009. Amazon Peasant Societies in a Changing Environment: Political Ecology, Invisibility and Modernity in the Rainforest. Environment: Springer Netherlands.

- Baragwanath, K;, and E. Bayi. 2020. “Collective Property Rights Reduce Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (34): 20495–20502. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1917874117.

- Benemann, N., C. Sordi, R. Menasche, and J. Collaço. 2023. Apresentação: Novos olhares antropológicos sobre comida. Antropolítica-Revista Contemporânea de Antropologia.

- BRASIL 2020. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Guia prático: alimentação escolar indígena e de comunidades tradicionais / Secretaria de Agricultura Familiar e Cooperativismo. – Brasília: MAPA/AECS. Accessed July 12, 2023. https://www.mpf.mp.br/atuacao-tematica/ccr6/catrapovosbrasil/documentos-e-publicacoes/guia-alimentacao-indigena-e-comunidades-tradicionais.pdf.

- Brasil. 2009. Lei nº 11.947, de 16 de junho de 2009. Dispõem sobre o atendimento da alimentação escolar e do Programa Dinheiro Direto na Escola aos alunos da educação básica. Brasília, DF: Diário Oficial da União.

- Brondizio, E. S. 2008. “Agriculture Intensification, Economic Identity, and Shared Invisibility in Amazonian Peasantry: Caboclos and Colonists in Comparative Perspective.” In Amazonian Historical Peasants: Invisibility in a Changing Environment, edited by C. Adams, R. S. S. Murrieta, W. A. Neves, and M. Harris, 181–214. Dordrecht, NE: Springer Publishers.