ABSTRACT

The National Islamic Alliance (NIA) has evolved as a leading Shia Kuwaiti political group since the 1980s. The NIA participates in electoral politics and Kuwaiti cabinets. While its roots go back to Shia activists in Kuwait, some of whom were linked to Iraq's Islamic Da'wa Party in the end of the 1960s, it is a pragmatic and Kuwaiti nationalist group. The article argues that the NIA shifted from being an active opposition group in the 1990s to a pro-ruling family and government group in 2008. The NIA's transformation was partly a response to the rise of sectarian politics in Kuwait and the opposition's resentment of the NIA's mourning of Imad Mughniyeh, a Lebanese Hezbollah leader. The article includes first-hand and secondary resources, including interviews and the NIA's figures' public statements to unpack the NIA's foundation, structure and changing relationship with the ruling family as well as its political engagement and positions on the Kuwaiti protest movement (2011–2013).

Introduction

The article explores the evolution of the most prominent and one of the oldest Shia Islamist political groups in Kuwait: the National Islamic Alliance (NIA). The study addresses how the NIA has evolved and engaged in politics. The paper relies on English and Arabic resources and Kuwaiti politicians’ statements and parliamentary debates in Majlis al-ʾUmma al-Kuwaytiyy (the National Assembly).

The NIA was loosely organised in the 1980s and has had roots in Kuwait’s Shia activism since the end of the 1960s. After years of turbulence in the 1980s in Kuwait and the Iraqi invasion and the restoration of the constitution in 1992, the relationship between Kuwaiti authorities and the Shia has become reasonably cordial. The Shia activist revolutionary networks, mainly the NIA, transformed themselves into peaceful organisations which have been given more space by the Emir to mobilise and enter politics.Footnote1 This article contends that the NIA changed from being a vehement opposition group in the 1990s, to pro-status quo and royal family since the mourning of Mughniyeh or al-Ta’byyn case in 2008 (see below), at which point it distanced itself from the opposition. Although Shia sub-groups splintered from the NIA, such as al-Methaq al-Waṭani, the NIA survived and outperformed other Shia groups. This article posits that the NIA has been a pro-government group and anti-opposition group even during the Kuwaiti protests (2011–2013) which coincided with the Arab Spring. Its position provided it with opportunities – strengthening ties with the government and temporarily joining the cabinets. However, it did not maintain high popularity among Shia constituencies.

The article first discusses the origins of the NIA. It then explores its formation, goals, structure, engagement in the political process, responses to the protests in Kuwait (2011–2013), and relationships with the ruling family.

The origin of the Shia group in Kuwait

Shias are considered the largest minority group in Kuwait, and it is estimated around one third or 30 per cent of Kuwaiti citizens are Shia.Footnote2 Shia Kuwaitis have been a key part of Kuwaiti state formation and they have been active in the Majlis al-Umma since its inception in 1963.Footnote3 Shia Kuwaitis settled in Kuwait 100–300 years agoFootnote4 and the majority are Twelver (Ithna ‘aashari) or Imami, the largest Shia subsect. Shia Kuwaiti Twelvers follow various doctrines and religious references marjáyya.

At the end of the 1960s, two Iraqi-based Shia movements, the al-Dáwa Islamic Party Ḥizb al-Dáwa al-Islāmiyya and the Message Movement or Movement of Vanguard Missionaries (MVM) Harakat al-Risāliyyan al-Ṭalá who are al-Shirazi’s followers (see below), extended to the Gulf region including Kuwait.Footnote5 Both al-Dáwa and the MVM sent clerics and activists from Iraq to Kuwait and their differences have since played out in Kuwait.Footnote6 These two movements had competing agendas and they differed in their religious and political visions. al-Dáwa was a political religious entity based in Najaf whereas the MVM was based in Karbala and the latter was the political wing of the al-Shirazi clerical family, under the spiritual leadership of Ayatollah Mohammad al-Husayni al-Šhirazi.Footnote7 The latter’s followers were known as Šhraziyyin (partisans of the al-Shirazi). Al-Shirazi’s argument was similar to the doctrine of Wilayat al-Faqih (Guardianship of the Jurisconsult) that entrusts the marjáyya (leading Shia clergy) with supreme political authority. Initially, the group was close to Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers. Shirazi’s school of thought holds that a council of scholars should govern the Islamic State (Hukumat al-Fuquh/Šhurat al-Fuquh), not a single cleric.Footnote8 After the 1979 Iran revolution, the relationship between the Ayatollahs Khomeini and al-Šhirazi deteriorated partly because of the clerics’ competition particularly over who to follow as a source of emulation (marjá al-taqlid).Footnote9

The NIA originated from al-Dáwa activists Nušhaṭṭa al-Dáwa. The Al-Dáwa network in Kuwait began with Ali al-Kourani (from Lebanon who arrived in Kuwait in 1969 and left in 1976) and Àzz al-Din Salim (known as Abu Yasin from Basra).Footnote10 Ḥizb al-Dáwa al-Islāmiyya (in Iraq) adhered to al-Sadr’s doctrine. Sadr's thought, which was portrayed in his manifesto The Bases of Islam (al-Usus al-Islāmiyya), stresses the goal of forming an Islamic state but not through revolutionary action. The revolution can be carried out in a limited condition. While al-Dáwa went through ideological and political shifts, today al-Dáwa has transformed into a pragmatic political party.Footnote11

In 1972 al-Dáwa networks in Kuwait gained control of the Social Society for Culture (SSC) Jamáiyyat al-Thaqafah al-Ijtimāáiyyah which was created in 1968. The SSC became the legal and public front of al-Dáwa in Kuwait and the groups within it were known as the Groups of the Line of the Imam (Ayatollah Khomeini) Majmuát Khatt al-Imam.Footnote12 Khatt al-Imam refers to students (usually youth) and clergy who support Ayatollah Khomeini’s conception of revolution. Khomeini’s conception of revolution is based on core Islamic values, the restoration of the Islamic rule of law, the rebellion against oppression and dispossession, and opposition to modernising reforms of the Pahlavi monarchy that promoted secular and cultural trends and were influenced by the United States. Khatt al-Imam’s followers transcended Iran’s borders including Lebanon, Iraq and the Gulf states.Footnote13

Al-Dáwa’s ideas spread fast among the Shia youth and students in Kuwait, and one of their key gathering areas was in Masjid al-Naqi.Footnote14 Al-Naqi is a prominent mosque for Shias, and Shia cleric Ali al-Kourani who oversaw the opening of the al-Naqi in 1967 was the first person who prayed at the mosque and was sent to Kuwait by Grand Ayatollah Sayyid Muhsin al-Hakim based in Iraq. Many attended al-Kourani’s gatherings at al-Naqi to listen to his religious lectures, including political insights.Footnote15Al-Kourani was a “Haraki ḥawzawi”, which means a member of a political movement and hawza (religious seminary).Footnote16 Al-Naqi became a vibrant place for learning and mobilisation for the Shia activists, including those associated with the SSC.Footnote17

Since the Iraqi al-Dáwa Islamic Party’s inception at the end of the 1950s its structure went through at least three shifts before 2003 when it asserted a more nationalist tone and reduced the role of clerics in the party.Footnote18 This weakened its transitional ties, including with Khatt al-Imam. The individual ties between the Iraqi al-Dáwa and their counterparts in Kuwait remained and some of them continued to share similar ideas.Footnote19 Al-Dáwa activists in Kuwait were not driven by Iran or Iraq in terms of political, logistical and material support and they represented a major Shia political trend in Kuwait as they were Kuwaiti nationalists, not a branch of the Iraqi Al-Dáwa.Footnote20

It is useful at this point to bear in mind the general nature of Kuwait’s constitution. Kuwait became an independent and constitutional monarchy in 1961. The arrangement was an elected legislature, constitution and separation of powers. A constituent assembly was elected in 1962, and the first parliamentary election was held in 1963.Footnote21 The political-constitutional arrangement is characterised by the dominant role of the Emir. The Emir appoints the government (cabinet members) without the approval of the Kuwaiti National Assembly (unicameral legislature). Thus, the government is not drawn from the majority of the assembly. All ministers are ex-officio members of the assembly. These arrangements reduce the separation of power between the legislature and executive bodies. While the pro-ruling family governments hold key executive powers, the assembly plays a critical role in holding the executive power accountable especially through questioning of ministers and holding votes of no confidence.Footnote22 Consequently, the relationship between the government and assembly has been increasingly tense.

Shia movements in Kuwait during the Iranian revolution

Kuwaiti Shias are not a monolithic community and many are divided at least into the following groups: merchants, mainly conservative and religious; and the middle class which seeks to reform the state. The Shias have been perceived as supportive of the government and the ruling family.Footnote23 The Iranian revolution shifted this perspective and some Shia grievances surfaced including freedom, equality and accountability.Footnote24 The Iranian revolution was at a time when the Kuwaiti semi-parliamentary system was in crisis and the ruling family suspended parliamentary life (1976–1981) and the constitution.Footnote25

Following the Iranian revolution, suspicion arose of the Shias in Kuwait. Nevertheless, Kuwaiti Shias demanded wider participation in politics and greater recognition of their role and rights.Footnote26 In the 1981 elections, the SSC fielded three candidates and began to win seatsFootnote27 which included cadres of Al-Dáwa such as Ádnan Ábd al-Samad, Ábd al-Muhsin Jamal and Naser Sarkhu.Footnote28 Most al-Dáwa clerics in Kuwait have supported the doctrine of Wilayat al-Faqih as the principle connects Islam to politics. The doctrine’s core principle fuses religion and politics through the medium of Faqih.Footnote29 Sabat argues that the doctrine addresses the question of who is legitimately qualified to rule during the occultation of the Shia’s Twelfth Imam and the scope of such rule beyond spiritual and legal issues to include the political aspect (leadership and governance).Footnote30

Since the Iranian revolution, al-Dáwa activists in Kuwait have believed in the concept of an Islamic State and also espoused the ideas of gradual action which sought to obtain concessions from the ruler including more democracy and power sharing. Kuwaiti al-Dáwa activists did not pursue the overthrow of the established order.Footnote31 Nevertheless, in the 1980s, the government used several measures to supress the Shia movements, for instance, supporting non-opposition Shia in elections in 1985 to reduce the pro-Iran Shia movements’ influence.Footnote32 At the beginning of the 1980s a number of Khomeini and al-Dáwa followers founded Hezbollah of Kuwait Hezbollah al-Kuwaiti.Footnote33 Although there were links between the latter and circles of Iranian authorities, Hezbollah of Kuwait managed not to be completely absorbed by the regime in Iran.Footnote34

The troubles in Kuwait started at the beginning of the 1980s when Iraqi al-Dáwa operatives and the Islamic Jihad Organisation – one of the designations that Lebanese Hezbollah used – carried out a series of terrorist attacks.Footnote35 The first prominent operation was on 12 December 1983, against the American and French embassies, and strategic and economic installations in Kuwait, which resulted in six dead and nine wounded.Footnote36 Seventeen were convicted and jailed in Kuwait and they became known by the moniker “Kuwait 17”.Footnote37 14 of them were affiliated to the Iraqi al-Dáwa and three to the Lebanese chapter of al-Dáwa created in the 1970s.Footnote38 In response, Imad Mughniyeh, a leader of the Lebanese Hezbollah, orchestrated attacks during this period, including hijacking a Kuwaiti airline in 1984 and 1988 and the attempted assassination of the Emir in 1985. His brother in law, Mustafa Bader al-Din, was one of those arrested for these attacks.Footnote39 These operations were carried out in order to compel the release the Kuwait 17, dissuade Kuwait from supporting Iraq in the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), and push the narrative of the Iranian revolution that underlines the struggles of the Muslims (namely Shia) against oppressive states.Footnote40 A tiny portion of Kuwaitis were involved in these attacks and these were part of external dynamics rather than internal conflict.Footnote41 These incidents further raised sectarian tensions and suspicions against Shias in Kuwait and the government deported thousands of expatriates from Iran and Bidoon (stateless Kuwaitis). The Shia further lost their rights and the government purged sensitive sectors of the administration.Footnote42

The SSC was influenced by Iran’s revolutionary ideology and gradually developed an Islamic identity representing a Shia segment of Kuwait.Footnote43 The SSC was peacefully engaged in promoting cultural education in centres and unions.Footnote44 In 1989 the government issued an order to disband the SSC, accusing some of its members of associating with the networks that caused the violence in the 1980s.Footnote45

After a policy of suppressing Shia groups in the 1980s, in the 1990s the regime decided that the best option was to co-opt the Shia groups by legalising some of their associations and allowing their electoral participation.Footnote46 Meanwhile, al-Dáwa activists ceased to be arrested and many of them became further integrated into legal associations with modest aspirations, such as creating a balance between the elected assembly and the ruling family, and pursuing political careers.Footnote47 However, the government was gerrymandering the districts in order to reduce Shia influence.Footnote48 Officially, political parties are not legal in Kuwait. Often, political groups rally around a common purpose or ideology, thus the groups “sponsor, back or ally themselves with parliamentary candidates”.Footnote49 Political groups or associations are to an extent tolerated; the constitution does not ban political parties, but equally they are not permitted.Footnote50

The official foundation of the National Islamic Alliance

The NIA unofficially emerged in 1980, and without declaring itself to be an association at that point, its key figures have been elected to the Majlis since 1980. Its presence became noticeable during the suspension of Majlis in 1986 – which continued until the Iraqi invasion – and for supporting the pro-democracy movement in 1989.Footnote51 During the invasion in 1991, key figures of the group took part in the “resistance” community action committee.Footnote52 A number of Hezbollah of Kuwait followers who escaped prison fought against the Iraqi invasion.Footnote53 Since then, the ruling family has become more tolerant of the peaceful Shia activists.Footnote54 Today, the Hezbollah of Kuwait does not exist,Footnote55 and the NIA denies any links to Hezbollah and Iran’s regime.Footnote56

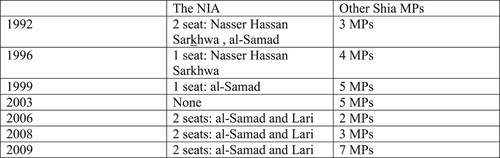

The group appeared in different forms since its formal organistion in 1992 under the name the Islamic National Coalition Itilaf al-Islaāmi al-Waṭani. The group’s core consisted of 89 Kuwaitis.Footnote57 This group supported the declaration of the “Future Outlook for Reform of Kuwait”,Footnote58 which was part of the reform plan in Kuwait. It participated in the 1992 elections and won two seats (see ). In 1998, it was fully reorganised and active under the name National Islamic Alliance al-Tahaluf al-Waṭanial-Islami.Footnote59 Laurence, Wehrey, AlbloshiFootnote60, AssiriFootnote61 and FreerFootnote62 rightly argue that the NIA was drawn from al-Dáwa activists in Kuwait, mainly the SSC, which included Khatt al-Imam, Shabab or youth of Masjid al-NaqiFootnote63 and those who gave up revolutionary approaches including Hezbollah of Kuwait.Footnote64 The SSC’s figures within the NIA included Abd al-Wahhab al-Wazzan, Hussein Abdullah al-Maʽatuk, Ábd al-Muhsin Jamal, Nassar Ábd al-Aziz and Adnan Abd al-Samad; the latter has won seats in the Majlis since 1981.Footnote65 The NIA also includes technocrats, educated and intellectual figures sympathetic to the Iranian revolution.Footnote66 The NIA follows Ayatollah Khamenei as a reference but they do not implement Khamenei’s political commands, as the NIA is a nationalist political group that believes in the Kuwaiti political system.Footnote67 The NIA follows other ayatollahs for personalFootnote68 and day-to-day practices, particularly Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. While several figures within the NIA have an affinity with the doctrine of Wilayat al-Faqih, most of the NIA figures have a pragmatic approach to political participation similar to the al-Dáwa party in Iraq post-2003. Today, the NIA’s figures accommodate and merge different political ideologies. Thus, the NIA is not a coherent political group as many of its figures have slightly different interpretations of an ideology and approach. For example, its prominent figure Sheikh Hussein Abdallah al-Ma’tuk takes conservative religious approaches.

Figure 1 The NIA’s election results since its official creation until 2009

Notes: Kuwait Politics Database, March 11, 2021, https://www.kuwaitpolitics.org/الاصوات-و-المواقف /.

In 1998, the first general secretary of the NIA was Sheikh Hussein Abdallah al-Ma’tuk.Footnote69 Al-Ma’tuk studied in Qum and contributed to opening Ḥawza Imam al-Hasan al-Mujtabi in 1996 in Kuwait. This religious seminary’s YouTube channel posts dozens of lectures and seminars.Footnote70 The NIA’s organisational structure includes al-Samad as its head and the political bureau head is Saleh al-Musa.Footnote71 There are certain unknown internal technical regulations which to its members adhere.Footnote72 While the NIA does not have specific written aims, it follows certain broad tenets and goals including: The commitment to the Kuwaiti Constitution; peaceful means for reform and change; individual freedom and equality particularly between Sunni and Shia citizens; securing the Shia community’s rights together with the principle of national unity. It supports the separation of the positions of Prime Minister and Crown Prince. Unlike the Salafists, it does not oppose women’s engagement in politics.Footnote73

The NIA’s associated newspaper is al-Dar, which belongs to Mahmud Ḥayder a Shia businessmen and the editor in Chief is Ábd al-Husayn al-Sultan. Al-Dar was supportive of PM Nasser al-Sabah.Footnote74 Al-Dar was suspended partly because it responded strongly to sectarian accusations.Footnote75 The NIA runs activities through student unions including al-Qaiyymia al-Islaāmiya at the University of Kuwait which actively organises events and promotes student rights.Footnote76

In response to the fragmentation within the NIA, its leaders have tried to project a unified image and one of their mottos was Kilmat al-Tawḥid wa Tawḥid al-Kilma (the unification of the word and the word that unifies). Many Shia groups splintered from the NIA because of various differences.Footnote77 In the 2003 elections, a schism emerged within the NIA’s Khatt al-Imam about the NIA’s devotion to the Wilayat al-Faqih doctrine. This division was because Ayatollah al-Sistani’s (who leads “the quietist school”) followers increased in number.Footnote78 The first group splintered from the NIA and Khatt al-Imam in 2003 and was led by Ábd al-Wahhab al-Wazzan, who was an active member in the SSC and minister of commerce (1999-2001).Footnote79 On 7 January 2003, al-Wazzan co-founded the Islamic National Accord Movement (INAM) (Haraka al-Tawafuq al-Islami al-Waṭani)Footnote80 which was inspired by the reform movement in Iran led by President Khatami and another key figure within the INAM Zahir al-Mahmid who became its secretary general.Footnote81 The splinter group mirrored the NIA’s poor performance in the 2003 elections.Footnote82

In 2005, another group splintered that represented a number of Kuwaiti al-Dáwa activists and cadres from Zahra House (Dar al-Zahra).Footnote83 Led by Yousef Al-Zalzalah, it created the National Pact/Charter Assembly (Tajamm’u al-Methaq al-Waṭani) on 6 July 2005.Footnote84 Al-Methaq al-Waṭani’s religious reference was the deceased Lebanese Ayatollah Muhammad Husayn Fadlallah – one of the founders of the al-Dáwa Islamic Party in Iraq and revered by the Lebanese Hezbollah.Footnote85

The Shirazis’ position against the NIA was underscored by the foundation of the Justice and Peace Alliance (JPA) in 2004, led by Ábd al-Hussein al-Sultan and Saleh Ashour. The JPA exhibited itself as anti-Hezbollah compared to the NIA and Khatt al-Imam.Footnote86 Hussein Qalaf (an independent Shirazi) confirmed the tensions between Shirazis and the SSC and said that the activists within the SSC were against the ‘Uluma [religious scholars of the Shirazi school].Footnote87 The JPA increasingly presented itself as a pro-establishment and more reliable Shia partner than the NIA. The JPA is also considered the second prominent Shia group in spite of its low representation in Maljis.Footnote88 In 2004 the JPA’s former secretary general al-Sultan denied that the JPA was founded against the NIA,Footnote89 but in September 2005, the JPA’s anti-NIA approach continued with its formation of a broad coalition with three different Shia political groups: Tajammú al-Methaq al-Waṭani, Haraka al-Tawafuq al-Islāmi al-Waṭani, Tajammú ‘Ullama al-Muslimen al-Shiá; it was called the National Coalition of Assemblies (I’tilaf al-Tajammuʿat al-Waṭani).Footnote90 The coalition aimed for a stronger unified Shia presence, but the JPA failed to secure seats in the 2006 elections, while the NIA secured two seats.Footnote91

Originally when the NIA was created it sided with opposition groups in Majlis to scrutinise the ruling family’s policies.Footnote92 The NIA was also seen as ‘the hawks’ as at the end of 1990s it coordinated with other MPs in establishing an opposition block called the Popular Action Block (PAB) Kutlat al-Ámal al-Shàabi. This pushed the NIA to vote with the populist, rather than Islamic blocs.Footnote93 The PAB became the main opposition bloc and it was headed by Dr Ahmad Sa’adoon and included populist figures, hardline nationalists, Shia Islamists and MPs across both tribal and urban constituencies.Footnote94 The NIA participated in the youth-led activist Orange Movement also referred to as Harakat Nabiha Khamsa (“we want it to be five districts”) in 2006 which called for an end to gerrymandering (by the reduction of districts from 25 to five to make vote-buying difficult).Footnote95 Eventually, the government conceded and reduced the districts to five. During this period, the NIA cooperated with the Islamic Constitutional Movement (ICM), the Muslim brotherhood branch in Kuwait, as the ICM was ready to form a parliamentary coalition with Shia MPs, something Salafists reject.Footnote96 However, the low level reproachment between the ICM and the NIA collapsed in 2008 because of the Ta’byyn case (see below).Footnote97 The NIA shifted from being a leading opposition entity to pro-government in 2008. Thenceforward, the NIA has been relatively careful in showing its political positions as not being too close to Iran’s regime and it has been an outspoken supporter of Kuwait’s ruling family.Footnote98

In 2008, al-Samad and Lari were expelled from PAB because of its public mourning of Hezbollah’s figure Mughniyeh as a martyr who was assassinated in February 2008.Footnote99 The NIA issued a statement that revered Mughniyeh and commemorated his death and organised a gathering at a Shia mosque Husseiniyya in the al-Rmithiyya area. The Kuwaiti MP al-Samad said, “The hero martyr shocked the earth underneath the Zionist and American enemy”.Footnote100 The gathering resulted in a harsh backlash by the opposition including all Sunni Islamists and liberals in 2008 against the NIA. The Kuwaiti media began an intensive campaign against the NIA, including a number of newspapers, particularly al-Waṭan, and stated that the gathering was provocative and didn’t respect the Kuwaitis who were killed during the attacks.Footnote101

While the NIA figures’ statements – such as al-Samad applauding the Lebanese Hezbollah’s role as an Islamic resistance group – at the mourning of Mughniyeh provoked the media and the opposition factions, the statements also asserted the unity between the Sunnis and Shias in Kuwait. For example, al-Samad said “No Shia and No Sunni but an Islamic national unity in Kuwait”.Footnote102 Al-Samad claimed that the media fuelled the situation and was pushing the security agencies to prosecute them.Footnote103 The Kuwaiti Interior Minister Sheikh Jabar Khalid al-Sabah expressed disapproval, saying “we shouldn’t glorify the terrorist and criminal Mughniyeh”.Footnote104 In March 2008, a large number of NIA followers and others who attended the mourning were wanted by the Kuwaiti Public Prosecution.Footnote105 This was known as the case of commemoration “Qaḏhiat Ta’byyn” and al-Samad and Lari were interrogated for one day then released on bail; both denied the charges, including that the NIA was an extension of Hezbollah of Kuwait.Footnote106 While the NIA apologised to the Kuwaiti people for organising the event, some of the NIA’s associates who did not even attend the gathering were briefly arrested.Footnote107

The media and the opposition accused the Shia groups of treachery and this pushed the NIA closer to the government. Since then, the NIA has become increasingly coopeted by the authorities and the alliance between Kuwaiti Shia groups and the al-Sabah ruler entrenched. This resulted in a tacit accord between the Shia groups and the government in exchange for ending the opposition stance.Footnote108 This informal agreement also included the reopening of the SSC, and the NIA’s members resumed their participation in it.Footnote109 One of the main reasons for the NIA’s shift towards pro-government positions is the media’s harsh campaign and opposition factions’ accusations against the NIA because of the mourning. The NIA and other Shia factions felt vulnerable during these times.

The Shia constituencies rallied around the NIA, namely al-Samad and Lari, and they managed to secure two seats in the parliamentary elections in May 2008 from a total of five Shia MPs which was slightly lower than the Shia average of 8 seats.Footnote110 The NIA participated in the cabinets as its associate Dr Fathel Safar, who was a member in the Kuwait Municipality, became the Minister of Public Works in 2008, Minister of State for Municipal Affairs in 2009 and Minister of State for Planning and Development Affairs in 2012.Footnote111 Lari, a key member of the NIA and former MP, often supported the ruling family and he opposed the interpellations of the PM Nasser Mohammed Al-Sabah in 2009 and 2010 in votes of no confidence by the opposition MPs.Footnote112

The NIA’s response to the protests in Kuwait (2011–2013)

The Arab Uprising inspired many Kuwaitis to mobilise and call for change. This movement was known as the Nation’s Dignity protests (Karamat Watan). This movement for change however began before the Arab Uprising; it was launched on the internet in November 2010 with the slogan “al-Sháb Yurid Isqāt Nasser” (the nation wants to oust PM Nasser). The NIA did not join the protestors, and the opposition [al-Muáraḏha] that began in the summer of 2011 was composed of Sunni Islamists, liberals, reformers, youth groups and conservative tribesmen.Footnote113

A few months before the protests in March 2011, sectarian tensions rose as the Kuwaiti government symbolically sent a naval force to support Bahrain’s ruling family in suppressing the Shia protesters there.Footnote114 While the Sunni Islamists blamed the government for doing little, the Shia MPs (e.g. al-Samad and Ashour) expressed their discontent and condemned Kuwait’s involvement.Footnote115 In April 2011, the government resigned following the latter and the Majlis’ questioning of the PM and the ministers, but the government was reappointed after a few days.Footnote116

In the summer of 2011, the protests in Kuwait again called for the government’s resignation. This was revitalised by the rising of traditional and new political actors such as the Fifth Fence Al-Sour al-Khams which claimed that it sought to protect the constitution from violations.Footnote117

The NIA backed the government’s positions and on 14 August 2011, the ruler Sabah al-Sabah and the Crown Prince, the Prime Minister, and a number of ministers visited a Ramadan gathering organised by the NIA.Footnote118 During a parliamentary session in the middle of 2011, there was a quarrel between the leader of the NIA al-Samad and Musallam al-Barrak, the opposition fire brand and a key member of the PAK. Al-Barrak accused al-Samad of defending the ruling family and MPs who had allegedly abused public wealth.Footnote119

By October 2011, the protests increased in intensity following a wave of strikes across the oil and customs sectors because of a corruption scandal; members of the ruling family had bribed a number of lawmakers.Footnote120 On 3 November 2011, an NIA figure Lari said, “It is true that as a movement we are not part of the opposition … because they [opposition] don’t have an agenda or a plan to tackle Kuwait’s challenges”.Footnote121

The NIA, together with the government’s 15 ex-officio votes alongside other pro-government MPs, voted to drop the interpellation of the PM.Footnote122 On 16 November 2011, several opposition MPs led by al-Barrak rallied demonstrators towards the PM’s residence and thereafter stormed into the Maljis.Footnote123 After the continuation of protests, Nasser’s government resigned on November 28 and was replaced by Jabr al-Mubarak al-Sabah. The Emir dissolved the Majlis on 6 December 2011, and called for new elections.Footnote124 Although the common theme among the protesters was the government’s resignation, they did not seek to unseat the monarchy.Footnote125 On 5 January 2012, Lari, the NIA’s MP said, “those who broke into al-Majlis have attacked the prestige of the legislative institution and their [protesters and opposition] messages were not about democracy, they steered the country into dilemma, we agree that there is corruption but their approach to reform is wrong … in the past we were with the opposition … but now we don’t recognise them as a real opposition”.Footnote126

Five interrelated factors contributed to the NIA’s disapproval of the protests and its support of PM Nasser al-Sabah: (1) Intra-royal family rivalries played a role as PM Nasser supported the Shia groups and some urban liberals to push back against the second generation royal rival populist Ahmed al-Fahd al-Sabah (former Deputy Prime Minister) who supported the broad tribal alliance and the youth.Footnote127 (2) Nasser’s tactic of divide and rule and the co-optation of the Shia resulted in the NIA becoming part of Nasser’s consecutive cabinets (2008–2011).Footnote128 (3) Nasser’s career as an ambassador to Iran before the 1979 revolution helped him in maintaining networks in Iran. Nasser was perceived by many Sunni Islamists and tribes to be too close to Iran and the Shia groups at the expense of Kuwait’s relationship with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Kuwaiti Sunnis. Nasser’s formal visits to Iran outnumbered his visits to GCC countries.Footnote129 These factors caused a number of Sunni Islamist MPs to impeach Nasser and positioned the NIA as an ally of pro-Shia Nasser. (4) The NIA viewed the protest movement as sectarian as although it was a broad coalition. It included anti-Shia figures such as Walid al-Tabtabai, an independent Salafi, Mohammad Hayif and Osama al-Minawr leaders of Tajammú al-Thawabt al-Umma, a Salafi group.Footnote130 There is anti-Shia sentiment among Salafists, and the Shia groups, particularly the NIA, feel that they need the regime’s protection.Footnote131 Safar al-Fadil, a member of the NIA and a former minister said, “There were radical Sunnis within the protests, and we [the NIA] were unable to support them … . They have attacked us in their ceremonies and described us as traitors.” However, some Shia figures supported the opposition, for example former MP Dr Hassan Juwhar, and some of them participated in the protests, such as Muntḏhir al-Habib and Abbas Muhammad who were arrested for their involvement.Footnote132

The elections in February 2012 resulted in a win for the opposition, which obtained 34 seats, including tribal and Islamist candidates (Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists) with al-Barrak gaining the highest number of votes. The Shia won seven seats which included two seats for the NIA. In a parliamentary session in March 2012, the NIA leader al-Samad criticised those who stormed the Majlis and denounced their actions and he cited examples of the damage of public properties.Footnote133

The pro-government MPs in the Majlis were the minority and the Emir dissolved the pro-opposition Majlis on 18 June 2012, because the cabinet resigned after the publicisation of the parliamentary grilling by the opposition of the new PM Jaber al-Sabah and other cabinet members for corruption.Footnote134 Simultaneously, the Emir called for early elections and after two days the Constitutional Court reinstated the previous pro-government Majlis and disqualified the majority opposition parliament. Al-Barrak rejected this and on June 27 demonstrators mobilised against the Court’s decision and called for the lifting of immunity from MPs accused of receiving bribes.Footnote135 The NIA continued to oppose the opposition and Lari said in the support of the government that the Finance Minister al-Šhamali succeeded in confronting the questioning as “he entered [Majlis] with white clothes and left with white clothes”.Footnote136

Although PM Jaber al-Sabah tried to reconvene the 2009 pro-government parliament in July and August in 2012, he failed to assemble the MPs because the majority of them refused. Thereafter, the Emir dissolved the parliament on 7 October 2012, for the second time and issued a decree to amend electoral law by reducing electorate votes from four votes to one, which the opposition opposed.Footnote137 The NIA had somewhat contradictory positions. Two days after the decree, al-Samad said “these [decrees] have constitutional flaws”.Footnote138 On 10 September 2012, al-Samad supported the reconvention of the 2009 Majlis and said “Those who say that Majlis in 2009 is void are words in the air”.Footnote139 The NIA’s inconsistencies show its dilemma between its close ties with the government and the decrees which were widely rejected.

On 15, 20, 21 October and 4 November 2012, Kuwait witnessed violent protests with tens of thousands mobilised against the decrees.Footnote140 On 20 December 2012, al-Samad said “We [the NIA] are not with the government because we love them but we don’t agree with the opposition”.Footnote141 Al-Samad also argued that “We are not a rubber stamp for the government and we are scrutinising the government including its budget and we disagreed with some unconstitutional actions of the government”.Footnote142 The NIA and al-Samad called the opposition’s actions in Majlis Nwab al-Ta’zyym (MPs who cause trouble). Al-Samad stated that, “The opposition is opposing the government’s policies on every case in order to serve its own interests” and also “the opposition has illogical demands such as requesting nine ministers from the opposition to be in the government”.Footnote143

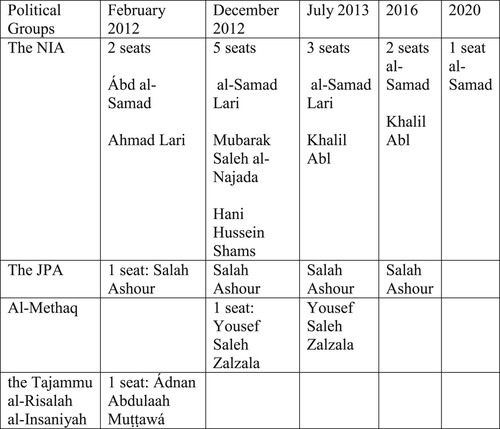

On 30 November 2012, one day before the snap election, a peaceful protest was organised. This included all main opposition actors including Sunni Islamists, tribes and youths. As a part of this protest, they boycotted the elections known as Muqaṭṭáat al-Intikhabat. As a result, voter turnout was low, around 40 to 26 per cent according to the government and the opposition respectively. Many Shia groups supported the elections and they came out ahead, securing 17 seats above the average. The Shia winners included four different political groups: the NIA secured five seats, JPA two seats, Tajammú al-Risalah al-Insaniyyah one seat, al-Methaq al-Waṭani one seat and the others were independent. The NIA celebrated its success and Lari said “This win is not against another or at the expense of another faction or sect”.Footnote144 This was an unprecedented achievement in electoral politics for the Shias due to the boycott of the opposition and it was seen as a political victory rather than a sectarian landslide.Footnote145

On 16 June 2013, the Constitutional Court declared the existing Majlis illegitimate and called for new elections but the Opposition Coalition decided to continue the boycott of the elections in July 2013 as it demanded “the four votes system” and that the cabinet’s members should be elected from Majlis.Footnote146 The opposition coalition of December 2012 fragmented and while a proportion of this coalition did not join the July 2013 elections, some tribes and liberals defected and participated as they did not want to be excluded. Fewer voters boycotted the elections; the turnout was 52.5 per cent.Footnote147 The NIA grudgingly accepted the constitutional court’s decision and it campaigned for the new elections. Former NIA MP Mubarak al-Najada said, “The dissolved assembly had important accomplishments in terms of legislatures and brought stability to Kuwait, but we accept the Court’s decision even if I would lose [my seat]”.Footnote148 The Shias lost half of their seats in the 2013 elections and the NIA got three seats, the JPA one seat, al-Methaq one seat and the others were independents (see ).

Figure 2 Shia groups in Kuwait’s elections from 2012 to 2020

Notes: Kuwait Politics Database, March 11, 2021, https://www.kuwaitpolitics.org/الاصوات - و-المواقف /

Similar to the Islamic al-Dáwa Party, the NIA also went through phases of ideological and political modifications and adjustments from being an opposition to a supporter of the government. Al-Dáwa moved from an opposition political force that tried to topple the regime in Baghdad before 2003 to a political entity that is actively engaged in the political process post-2003 and became an integral part of the political class in Iraq. The changes within the NIA were less extreme as the NIA originally did not try to overhaul the entire political system in Kuwait like al-Dáwa. However, the shift shows the NIA's willingness to adapt its political positions.

The re-emergence of sectarianism in 2015

The summer of 2015 witnessed two incidents that increased sectarian tensions in Kuwait. First, the bombing of the Shia al-Sadiq Mosque in June 2015 by Daesh which resulted in 27 deaths. Secondly, in August 2015, the authorities seized tons of weapons and explosives from two houses in Kuwait’s al-Ábdali area; 27 people were charged.Footnote149 Al-Samad condemned the authorities’ brutal measures including allegations of the interior ministry’s torture of the captives. Al-Samad questioned the Minister of Interior, saying “I wonder why the ministry did not take similar measures against those who were accused of their involvement in the bombing of al-Sadiq”. Whilst in November 2015, al-Samad applauded the Emir’s speech on Kuwait’s security in Majlis, he blamed the media for agitating over the al-Ábdali case and stirring up sectarianism because the media called for executions and the stripping of citizenship.Footnote150 Although in 2015 al-Samad stated that the NIA’s members were shocked by the al-Ábdali case, in 2019 the prominent NIA figure al-Mátuk was arrested and sentenced to five years in prison because he aided a suspect’s escape.Footnote151

The NIA generally sided with the Shia MPs; for example, it opposed lifting Ábd Hamid Dashti’s parliamentary immunity because he criticised Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen. However, the NIA’s MPs disagreed with Dashti’s approach as he was perceived to be too provocative.Footnote152 Al-Samad said “there were MPs who said things harsher than Dashti but no one took a measure against them, therefore the move is driven by regional politics”.Footnote153 The NIA tried to maintain a balanced political posture and suggested that Kuwait should mediate between Saudi Arabia and Iran.Footnote154

The NIA in the 2016 and 2020 elections

In October 2016, the Emir dissolved the Majlis by royal decree because of disputes between the government and the Majlis on austerity measures caused by budget deficits; regional upheaval (the war on Daesh) and the two incidents in 2015 that fuelled various security tensions; and to appease the tribal groups who boycotted previous elections. In 2016, the opposition alliance further disintegrated and slowly returned to engage in electoral politics and there was a sense of competition between and within Shia groups.Footnote155

On November 16, al-Samad stated that the NIA’s main goal of the 2016 elections was national unity and security. Al-Samad criticised the opposition, particularly the boycotters, as he believed that the opposition’s claim to stabilise Kuwait was not honest after they had steered protests over the last years.Footnote156 The opposition was the winner of the 2016 elections and gained 24 seats. The NIA’s presence was reduced from three to two seats and Lari lost his seat. The opposition’s participation and high turnout (around 70 per cent) on 26 November 2016, further reduced the Shia seats from nine to six.Footnote157 Similarly, in Kuwait’s parliamentary elections on 5 December 2020, the Shia again won six seats and the NIA’s position was further eroded as it won one seat and the other five Shias winners were independent. Thus, the Shias in this assembly feel that their voices have been curtailed because of the ascendance of the opposition Sunni Islamists.

Conclusion

The NIA is a result of the most enduring Shia movement in Kuwait which has been active for almost half a century. The founders and supporters of the NIA through the SSC have maintained a political presence since the Iranian Islamic revolution. The members who founded the NIA are not monolithic, and the members are from a spectrum of Shia ideological strands and groups, including conservatives such as Khatt al-Imam, al-Dáwa activists and Shia moderates. The NIA gradually became a pragmatic political group that seeks the protection of Shia constituencies’ rights and political participation, and particularly having seats in the assembly as critical priorities. These priorities have driven the NIA’s political orientation instead of the Shia ideological tenets.

The NIA’s roots and its activities prior to its official formation in 1992 and until 2008 showed an oppositionist stance. This stance changed when the NIA realised that anti-Shia rhetoric was on the rise from Salafists, the opposition groups, and a large segment of the Kuwaiti media, particularly at the time of NIA’s mourning of Mughniyeh. The NIA figures viewed the political atmosphere as less tolerant of the NIA and other Shia groups. Thus, the NIA sided with the government as the ruling family provided a sort of political shelter. It aimed to secure a solid political presence without the support of the opposition.

In the 1980s and 1990s the government promoted the tribal and Sunni Islamist candidates against the Shia and liberals. Since 2003, Sunni Islamists have become more hostile towards the government as they became more politically conscious and by 2008 the government became closer to the Shia groups including the NIA. The latter sought more political support from the government partly because of rising sectarian tensions.Footnote158 The intra-ruling family (the pro-Shia PM Nasser versus the populist pro-tribal alliance and the youth Ahmed al-Fahd al-Sabah) competition provided an avenue for the Kuwaiti Shia groups. The intra-ruling family rivalries paved the way for the NIA to engage further in the political process and consolidate its ties with the government and powerful elements within the ruling family.

Although there are ideological and political differences between the NIA and Shirazi followers and other Shia groups, the NIA tries to put aside its differences when it perceives a threat against Shia groups. This was especially evident during the NIA and the Shia groups’ position regarding the protest period of 2011–2013 when anti-Shia rhetoric was on the rise in Kuwait, especially among Salafists. During the Arab Spring, the NIA sided with the government, which further distanced the NIA from the opposition political factions.

The case of al-Ábdali in 2015 and the lifting immunity from Dashti (a Shia MP) underlines the NIA’s delicate political position. The NIA post-Ta’byyn tries to maintain its pro-Shia position but not at the expense of its friendly relationship with the ruling monarchy. The NIA seeks to adhere to its pro-Shia stances (for example, by addressing and highlight Shia grievances and rights) and to appease Shia constituencies. While the 2016 and 2020 elections further weakened the NIA’s presence in Majlis, the NIA has over its long history of political participation, demonstrated a considerable degree of endurance.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Zana Gulmohamad

Dr Zana Gulmohamad is an Associate Lecturer in politics at the Department of Law and Criminology at Edge Hill University. He has a PhD in international politics from the University of Sheffield. His Publications include The Making of Foreign Policy in Iraq: Political Factions and the Ruling Elite (I.B. Tauris, 2021). Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 H. Albloshi, ‘Iran and Kuwait’, in G. Bhgat, A. Ehteshami and N. Quilliam, (Eds.), Security and Bilateral Issues Between Iran and its Arab Neighbours. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 123–149, p. 128.

2 D. Shultziner and M. Tétreault, ‘Representation and Democratic Progress in Kuwait’. Representation Vol. 48. Issue 3 (2012): 281–293.

3 I. al-Marashi, ‘Shattering the Myths about Kuwaiti Shia’. Al-Jazeera, June 30, 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/6/30/shattering-the-myths-about-kuwaiti-shia (accessed 11 February 2021).

4 M. Alruwayeh, ‘PhD thesis: Diglossic Code-switching in Kuwaiti Newspapers’. Newcastle University, 2016, February, p. 20, https://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/3409 (accessed 11 February 2021).

5 T. Matthiessen, The Other Saudis Shiism, Dissent and Sectarianism. New York: The University of Cambridge, 2015, p. 94.

7 L. Louër, ‘The Limits of Iranian Influence Among Gulf Shi’a’. CTC Sentinel Vol. 2. Issue 5 (2009): 1–3.

8 T. Matthiesen, ‘Hizbullah al-Hijaz: A History of The Most Radical Saudi Shi’a Opposition Group’. Middle East Journal Vol. 64. Issue 2 (2010): 179–197.

9 L. Louër, Transnational Shia Politics: Religious and Political Networks in the Gulf. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008, p. 97.

10 ‘Political Movements in Kuwait’. Kuwaiti Progressive Movement, December 3, 2013, http://taqadomi.com/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/12/التيارات-السياسية.pdf

11 Y. Dai, ‘Transformation of the Islamic Da‘wa Party in Iraq: From the Revolutionary Period to the Diaspora Era’. Asian and African Area Studies Vol. 7. Issue 2 (2008): 238–267.

12 Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 128.

13 L. Reda, ‘Khatt-e Imam: The Followers of Khomeini’s Line’, in A. Adib-Moghaddam (Ed.), A Critical Introduction to Khomeini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 115–148.

14 B. al-Matt’ari, ‘Sunni and Shiite Islamic Movements in Kuwait’. AlJarida, May 6, 2018, https://www.aljarida.com/articles/1525538344738784900/; Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 115 and 116.

15 B. Naser, ‘al-Mattari Sunni and Shiite Islamic Movements in Kuwait’. Al-Jarida, May 6, 2018, https://www.aljarida.com/ext/articles/print/1525538344738784900/ (accessed 15 November 2021).

16 Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 113.

17 Naser, ‘al-Mattari Sunni', op. cit.

18 Z. Gulmohamad and Munathamat Badr, ‘From an Armed Wing to a Ruling Actor’. Small Wars & Insurgencies (2021): 2.

19 Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 200 and 201.

20 Ibid. p. 199.

21 G. Alnajjar, ‘The Challenges Facing Kuwaiti Democracy’. Middle East Journal Vol. 54. Issue 2 (2000): 242–258.

22 ‘Assessment of the Electoral Framework Final Report’. Kuwait Transparency Society, November 2008, https://democracy-reporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/dri_kuwait_report_08.pdf?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=f29c9997182e6ad3512524feaca4f756077f4a9a-1615547038-0- (accessed 15 November 2021).

23 H. Alboshi, ‘Sectarianism and the Arab Spring: The Case of the Kuwaiti’. The Muslim World Vol. 106. (2016): pp. 109–126, p. 113.

24 A. Baaklini, ‘Legislatures in the Gulf Area: The Experience of Kuwait, 1961–1976’. International Journal of Middle East Studies Vol. 14. Issue 3 (1982): 359–379.

25 ‘Kuwaiti Cabinet Resigns; Parliament Dissolved; Two Ex-MPs Detained’. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 12, 2008, https://carnegieendowment.org/2008/08/12/kuwaiti-cabinet-resigns-parliament-dissolved-two-ex-mps-detained-pub-20535 (accessed 5 February 2021).

26 P. Salem, ‘Kuwait: Politics in a Participatory Emirate’. Carnegie Middle East Center, Number 3, June 2007. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/157954/CMEC_3_salem_kuwait_final1.pdf (accessed 5 February 2021).

27 H. al-Mughni, ‘The Rise of Islamic Feminism in Kuwait’. Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée Vol. 128 (2010): pp. 167–182, p. 208.

28 Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 204.

29 A. Sabet, ‘Wilayat al-Faqih and the Meaning of Islamic Government’, in A. Adib-Moghaddam (Eds.), A Critical Introduction to Khomeini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 69–70.

30 Ibid.

31 L. Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, p. 201.

32 Alboshi, op. cit., p. 114.

33 M. Rubin, ‘Has Kuwait Reached the Sectarian Tipping Point?’ American Enterprise Institute, Report No. 4, August 14, 2013, pp. 1–11. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/has-kuwait-reached-the-sectarian-tipping-point/ (accessed 5 February 2021).

34 Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 198 & 213.

35 ‘Kuwait: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy’. Congressional Research Service SRC Report, May 12, 2021, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/RS21513.pdf.

36 M. Levitt, ‘29 Years Later, Echoes of Kuwait 17’. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 13, 2012, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/29-years-later-echoes-kuwait-17.

37 M. Levitt, Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2013, p. 35.

38 J. Kifner, ‘Ex-hostages on Kuwait Jet Tell of 6 Days of “Sheer Hell”’. The New York Times, December 11, 1984, p. 10.

39 O. Seliktar and F. Rezaei, Iran, Revolution, and Proxy Wars. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019, p. 30.

40 D. Avon and A. Khatchadourian, Hezbollah: A History of the “Party of God”. Harvard University Press, 2012, p. 30.

41 Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 175.

42 E. Azani, Hezbollah: The Story of the Party of God From: Revolution to Institutionalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 179.

43 Alboshi, op. cit., pp. 123–149.

44 S. Ghabra, ‘Voluntary Associations in Kuwait: The Foundation of a New System?’ Middle East Journal Vol. 45. Issue 2 (1991): 199–215, p. 208.

45 K. Haider, ‘Who Protects the Moderation of the Shiites in Kuwait?’ Al-Yam, May 20, 2012, https://www.alayam.com/Article/courts-article/80280/Index.html; F. al-Mdrisi, ‘The First Public Presence of a Shiite Organization in Kuwait’. Elaph, December 4, 2006, https://elaph.com/Web/NewsPapers/2006/12/195239.html (accessed 2 March 2021).

46 K. Selvik, ‘Elite Rivalry in a Semi-Democracy: The Kuwaiti Press Scene’. Middle Eastern Studies Vol. 47. Issue 3 (2011): 477–496, p. 479.

47 Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 204.

48 Salem, op. cit., pp. 3–6.

49 D. Shultziner and M. Tétreault, ‘Representation and Democratic Progress in Kuwait’. Representation Vol. 48. Issue 3 (2012): 281–293, p. 282.

50 G. Alnajjar, ‘The Challenges Facing Kuwaiti Democracy’. Middle East Journal Vol. 54. Issue 2 (2000): 242–258, p. 247.

51 M. Tetreault, ‘Civil Society in Kuwait: Protected Spaces and Women’s Rights’. Middle East Journal Vol. 47. Issue 2 (1993): 275–291, p. 278.

52 A. al-Hajeri, ‘PhD thesis: Citizenship and Political Participation in the State of Kuwait: The Case of National Assembly (1963–1996)’. University of Durham, 2004, p. 268. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/108451.pdf.

53 L. Zaccara, C. Freer and H. Kraetzschmar, ‘Kuwait’s Islamist Proto-parties and the Arab Uprisings: Between Opposition, Pragmatism and the Pursuit of Cross-ideological Cooperation’, in H. Kraetzschmar and P. Rivetti (Eds.), Islamists and the Politics of the Arab Uprisings. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018, pp. 182–203.

54 Alboshi, op. cit., p. 128.

55 Ibid., pp. 128–129.

56 ‘Assessment of the Electoral Framework Final Report’. Kuwait Transparency Society, November 2008, https://democracy-reporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/dri_kuwait_report_08.pdf?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=f29c9997182e6ad3512524feaca4f756077f4a9a-1615547038-0- (accessed 1 February 2021).

57 A. al-Sau’da and A. Tahir, Kuwaiti Democracy: History – Reality and Future. Egypt: Al-Arabi Publishing, 2011, p. 154.

58 Al-Hajeri, op. cit., p. 268.

59 B.A. Alrajhi, ‘PhD thesis: Terrorism and the Law of Kuwait’. The University of Leeds, January 2015, p. 44, https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/9146/1/Bader_Alrajhi_Thesis_Corrected.pdf (accessed 7 March 2021).

60 Alboshi, op. cit., pp. 128–129.

61 A.R. Assiri, ‘The 2006 Parliamentary Election in Kuwait: A New Age in Political Participation’. Domes Vol. 16. Issue 2 (2007): 22–43.

62 C. Freer, ‘Kuwait’s Post-Arab Spring Islamist Landscape … ’, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, August 8, 2018, p. 4. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/media/files/files/55beac94/bi-brief-080818-cme-carnegie-kuwait2.pdf

63 Al-Sau’da and Tahir, op. cit., p. 154.

64 Al Alboshi, op. cit., p. 128.

65 M. Herb, ‘Shi’i Islamists’. Kuwait Politics Database, 2020, http://www.kuwaitpolitics.org/pg3.htm, (accessed 6 March 2021).

66 Al-Sau’da and Tahir, op. cit., p. 154.

67 F. Wehrey, Sectarian Politics in the Gulf from the Iraq War to the Arab Uprisings. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014, p. 209.

68 Ibid., p. 209.

69 R. Azoulay and C. Beaugrand, ‘Limits of Political Clientelism: Elites’ Struggles in Kuwait Fragmenting Politics.’ International Journal and Social Sciences in the Arabian Peninsula Vol. 4. (2015).

70 ‘Hawza of Imam Al-Hassan Al-Mujtaba’. YouTube, March 3, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC8P5dgOTtBzVLsAL3-J0wCg (accessed 22 March 2021); Louër, Transnational Shia Politics, op. cit., p. 209.

71 ‘The Islamic Alliance’. Al-Qabas, May 4, 2006, https://alqabas.com/article/193926- التحالف -الإسلامي -تقليص -الدوائر-إلى -خم (accessed 22 January 2021).

72 M. Saber, ‘Shia in the Gulf’. Markaz al-Aema, November 19, 2015, https://al-aema.com/2015/11/الشيعة -في -الخليج -الإنتشار - والنفوذ -الك / (accessed 22 January 2021).

73 Al-Hajeri, op. cit., p. 268.

74 Selvik, op. cit., p. 485.

75 B. Flanagan, ‘Criticisms follow Kuwait Court … ’. The National, March 22, 2012, https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/mena/criticisms-follow-kuwait-court-order-to-suspend-al-dar-newspaper-1.359661 (accessed 22 January 2021).

76 ‘The Islamic List at Kuwait University’. AlKout-YouTube, May 4, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ohIrUdcLQPs (accessed 22 January 2021).

77 H. Al-A’las, ‘The Million Deposits’. Al Rai Media, May 1, 2012, https://www.alraimedia.com/print-article?articleId=300330 (accessed 22 January 2021).

78 Wehrey, op. cit., p. 209; Herb, 2020.

79 Ibid.

80 ‘Shiites in the Gulf Spread and Influence’. Arab Gulf for Strategic Studies and Research, February 27, 2015, http://www.center-lcrc.com/print.php?s=4&id=13134 (accessed 22 January 2021).

81 ‘“National Accord” Elects Al-Mahmeed as Secretary-General’. Al-Qabas, February 22, 2006, https://alqabas.com/article/114888-التوافق -الوطني -تنتخب -المـحميد -أمين (accessed 22 January 2021).

82 Wehrey, op. cit., p. 209.

83 Y. Ghanem, ‘“I was a Minister” Reviews Saleh’s Notes in the Ministerial Post’. Al-Anba, July 7, 2018, https://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/843400/08-07-2018- -كنت -وزيرايستعرض -مذكرات-الصالحفي -المنصب -الوزاري / (accessed 22 January 2021).

84 A. Daqa, ‘Iranian “Tashbih” in Kuwait’. al-Bayan, January 15, 2016, https://albayan.co.uk/Article2.aspx?id=4863 (accessed 22 January 2021).

85 T. Mostyn, ‘Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah Obituary’. The Guardian, July 5, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/jul/05/grand-ayatollah-mohammed-hussein-fadlallah (accessed 22 January 2021).

86 ‘Karbala Taught Me … Abd al-Husayn al-Sultan’. Kuwait TV-YouTube, October 8, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dA4C6-f4rrY; Wehrey, op. cit., p. 210.

87 ‘Disagreement between Al-Shirazi and Dawa in Kuwait’. Al-Mehwar Channel-YouTube, December 14, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcsCDgjjbDE (accessed 29 January 2021).

88 M. Olimat, Arab Spring and Arab Women: Challenges and Opportunities. New York: Routledge, 2014, p. 101.

89 A. Al-Shati, ‘Shiite Front Against … ’. Elaph, December 29, 2004, https://elaph.com/Politics/2004/12/30540.html (accessed 28 January 2021).

90 ‘The Announcement of the Shiite Gatherings … ’ Annabaa, June 29, 2005, https://annabaa.org/nbanews/50/319.htm (accessed 28 January 2021).

91 ‘Political Developments in the State of Kuwait’. Gulf Center For Development Policies, May 6, 2016, https://gulfpolicies.org/2019-10-30-17-33-56 (accessed 28 January 2021).

92 Albloshi, op. cit., p. 128.

93 A. Alsharekh, ‘Youth, Protest, and the New Elite: Domestic Security and Dignity in Kuwait’, in C. Ulrichsen (Eds.), The Changing Security Dynamics of the Persian Gulf. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–190.

94 Salem, op. cit., pp. 12–13.

95 Shultziner and Tétreault, op. cit., p. 288.

96 A. Al-Rumaili, Interview via the Phone, April 22, 2021.; C. Freer, ‘The Rise of Pragmatic Islamism in Kuwait … ’. Brookings Institution, August 2015, p. 10, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/kuwait_freer-finale.pdf.

97 Ibid.

98 Salem, op.cit., pp. 12–13.

99 I. Hirotake, ‘Political Participation of the Muslim Brotherhood in Kuwait … ’. IDE Discussion Paper Vol. 730. Issue November (2018).

100 ‘The Condolences of Imad Mughniyeh Stirs Sectarian Controversy’. Elaph, February 16, 2008, https://elaph.com/Web/NewsPapers/2008/2/304609.html (accessed 5 January 2021).

101 Albloshi, op. cit., p. 116.

102 ‘MP Samad in the Memorial of Imad Mughniyeh: Some Parasites Tried to Offend the Martyr … ’. al-Jarida, February 2, 2008, https://www.aljarida.com/articles/1461253328297554300/ (accessed 15 November 2021).

103 A. Al-Saud, ‘Abdul Samad: I Swore Allegiance to the Emir 4 Times’. Alnaba, March 28, 2008, https://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/last/25234/26-03-2008-عبدالصمد -اقسمت -على -الولاء-للامير -مرات-فكيف -اتهم -بهذه -التهم -ولاري-يرد -التحالف-الوطني -علاقة -له -بحزب -الله -اللبناني / (accessed 5 January 2021).

104 A. Al-Matt’ari et al., ‘The National Islamic Alliance Tends to Announce … ’. AlRai Media, February 22, 2008, https://www.alraimedia.com/article/24263/محليات /التحالف -الإسلامي -الوطني-يتجه -إلى -إعلان-اعتذار-من -الكويتيين -عموما -وأهالي -شهداء -الجابرية -خصوصا (accessed 5 January 2021).

105 Freer, op. cit., p. 4.

106 Al-Saud, ‘Abdul Samad … ’.

107 ‘Jawuher: The Government Handling of al-Ta’abeen … ’. Al-Jarida, March 3, 2008 https://www.aljarida.com/articles/1461347775436490200/ (accessed 5 March 2021).

108 L. Louër, ‘The Transformation of Shia Politics in the Gulf Monarchies’. POMPS Studies-Project on the Middle East, December 2017, p. 39, https://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/POMEPS_Studies_28_NewAnalysis_Web.pdf (accessed 5 March 2021).

109 ‘Speech of the Guest of Shams’. The Social Society for Culture – YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j2J9KA1sjiM (accessed 5 April 2021).

110 Salem, op. cit., pp. 12–13.

111 A. AbdRahman, ‘Abd al-Samad the Cabinet … ’. AlRai Media, December 22, 2012, https://www.alraimedia.com/print-article?articleId=369952 (accessed 5 April 2021).

112 ‘Ahmed Larri and Memories of Al-Naqi Mosque’. Al-Mehwar Channel-YouTube, November 12, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mYRFk2cUuV8 (accessed 5 April 2021).

113 F. Dazi-Heni ‘The Arab Spring Impact on Kuwaiti “Exceptionalism”’. International Journal of Archaeology and Social Sciences in the Arabian Peninsula Vol. 4 (2015).

114 Shultziner and Tétreault, op. cit., pp. 281–293.

115 A. Nosova, ‘Kuwaiti Arab spring? The Role of Transnational Factors in Kuwait’s Contentious Politics’, in F. Gerges (Ed.), Contentious Politics in the Middle East. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 75–79, p. 78.

116 ‘Kuwait Ministers Resign, News Agency Says’, CNN, March 13, 2011, http://edition.cnn.com/2011/WORLD/meast/03/31/kuwait.government/index.html (accessed 5 April 2021).

117 K.C. Ulrichsen, ‘Politics and Opposition in Kuwait: Continuity and Change’. Journal of Arabian Studies Vol. 4. Issue 2 (2014): 214–230, p. 222.

118 ‘The National Islamic Alliance’. Al Kut channel-YouTube, August 15, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7XwNnVG0QyE (accessed 5 April 2021).

119 ‘A Quarrel between Al-Barrak and -Samad’. Mauqa’ Baraka -YouTube, September 7, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WKXi4YjhkOU (accessed 5 March 2021).

120 J. Calderwood, ‘Bank Accounts of 14 Kuwait MPs to be Frozen in Bribery Inquiry’. The National, September 30, 2011, https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/mena/bank-accounts-of-14-kuwait-mps-to-be-frozen-in-bribery-inquiry-1.470530 (accessed 5 March 2021).

121 ‘Larri: We are not with the Opposition and We are not Loyal to the Government’. Al-Mehwar Channel-YouTube, November 5, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAUYqeuyBKk (accessed 5 March 2021).

122 ‘Crossing Out the Al-Saadoun and Al-Anjari Questioning in 2011’. Kuwait Politics Database, November 2011, 16, http://www.kuwaitpolitics.org/positions71.htm (accessed 9 March 2021).

123 ‘Protesters Storm Kuwaiti Parliament’. BBC, November 16, 2011, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-15768027 (accessed 9 March 2021).

124 Ulrichsen, op. cit., p. 223.

125 Shultziner and Tétreault, op. cit., p. 286.

126 ‘Interview: Lari’, al-Mehwar Channel-YouTube, January 5, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O_ETy0LIgc4 (accessed 9 March 2021).

127 K. Diwan, ‘Kuwait: Finding Balance in a Maximalist Gulf’. The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, Issue 4, June 29, 2018, https://agsiw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Diwan_Kuwait_ONLINE.pdf

128 Dazi-Heni, ‘The Arab Spring … ’.

129 Louër, op. cit., pp. 30–40; Azoulay and Beaugrand, ‘Limits of Political’.

130 ‘13 Islamists are Participating in the Elections’. al-Qabas, October 26, 2016, https://alqabas.com/article/311114-13-إسلامياً-يشاركون-في-الانتخابات (accessed 9 March 2021).

131 S. Al-Fadhli, ‘Interview via Phone’, November 28, 2020.

132 Albloshi, op. cit., p. 122.

133 ‘The Speech of MP in Majlis’. YouTube, May 3, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vwmzcz2Q_rg&t=501s (accessed 9 March 2021).

134 Ulrichsen, op. cit., p. 223.

135 ‘Kuwait Protest at Court Ruling Dissolving Parliament’. BBC, June 27, 2011, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-18606540 (accessed 9 March 2021).

136 ‘Ahmad Lari 2012’, Mohamad Lari-YouTube, July 1, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I8RJt_Iay7I&t=106s (accessed 9 March 2021).

137 K. Ulrichsen, ‘Pushing the Limits: The Changing Rules of Kuwait’s Politics’. World Politics Review, March 1 2016, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/18241/pushing-the-limits-the-changing-rules-of-kuwait-s-politics (accessed 9 March 2021).

138 ‘Representatives Commenting on the “Constitutional” … ’. Alanba, July, 21, 2012, https://www.alanba.com.kw/ar/kuwait-news/parliament/303316/21-06-2012-نواب-تعليقا-على-حكم-الدستورية-ببطلان-مجلس-نحترم-احكام-القضاء/ (accessed 9 March 2021).

139 ‘Samad: Some are Holed up Behind the 2009 Council’. Al-Mehwar Channel-YouTube, September 10, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bssHHA8PTko (accessed 9 March 2021).

140 ‘Kuwait: Lift Protest Ban’. Human Rights Watch, November 10, 2012, https://www.hrw.org/node/247958/printable/print (accessed 9 March 2021).

141 ‘Samad in the Al-Rai Interview 2012’. Abdul Dashti-YouTube, December 21, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Qzb-VhRdLs&t=1170s

142 Ibid.

143 A.G. Saleh and M.N. Ganm, The Civic State and the Civilised Dilemma: The Situation in Kuwait. Riyadh: Difaf Publishing, 2014, p. 90.

144 ‘Members of the National Islamic Alliance Receive’. AlKout Taqreer-YouTube, December 3, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CZtvuwi0TSs (accessed 9 March 2021).

145 Olimat, op. cit., p. 98.

146 I. Bickerton, ‘Explainer: Kuwait Elections’. The Conversation, July 26, 2013, https://theconversation.com/explainer-kuwait-elections-16264 (accessed 9 March 2021).

147 S. al-Atiqi, ‘One Man, One Vote’. Sada-Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 12, 2013, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/52947.

148 ‘Candidates of the Islamic Alliance’. Kuwait Television-YouTube, July 25, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ILgGTSzt1A (accessed 9 March 2021).

149 M. Levitt, ‘Hezbollah’s Pivot Toward the Gulf’. CTC Sentine Vol. 9. Issue 8 (2016): 11–16.

150 ‘Samad on the Issue of the Abdali Cell’ Mauqa’. Al-Burka-YouTube, November 4, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgQ3KUIRVpQ.

151 M. Habib, ‘Court rules in the case of “Al-Ma’touk … ”.’ Al-Qabas, December 2, 2019, https://alqabas.com/article/5730643-في-قضية-التستر-على-خلية-العبدليحبس-الداعية-المعتوق-و-3-أخرين (accessed 9 March 2021).

152 ‘National Assembly Lifted the Immunity of Dashti’. Al-Qabas, March 15, 2016, https://alqabas.com/article/3883-جلسة-مجلس-الأمة-لحظة-بلحظة (accessed 9 March 2021).

153 ‘Interview: Abd Samad’. Al-Mehwar Channel-YouTube, November 16, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5u9mpOb5zIo (accessed 9 March 2021).

154 ‘Al-Samad: Kuwait Should Mediate between Saudi and Iran’. Wadaa, January 9, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SRfnllMOjE.

155 S. Weiner, ‘Kuwait’s Emir Just Dissolved the Country’s Parliament … ’. The Washington Post, October 17, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/10/17/kuwaits-emir-just-dissolved-the-countrys-parliament-heres-why/.

156 Ibid., ‘Interview: Samad’, 2016.

157 M. Alfrhan, ‘The Scramble for Kuwait’s Democracy’. The International Affairs Review, December 24, 2016, https://www.iar-gwu.org/blog/2016/12/24/the-scramble-for-kuwaits-democracy.

158 Selvik, op. cit., p. 479.