ABSTRACT

Youth unemployment rates in the United Kingdom are almost triple that of adults (11.3% vs. 4%), particularly impacting the employability of young people with complex needs, of whom 61.8% are unemployed. Interventions facilitating transition into work can operate at individual, community and government levels. The main objectives of this review were to explore current practices, identify factors affecting and strategies used to improve employability, and classify strategies at multi-levels. Findings suggest that collaborative strategies covering training, work practices, therapeutic support and creating appropriate work environments, with active involvement of young people, are key in supporting young people with complex needs into employment. Classification of factors indicated four categories: skills-based approaches, job/work experience accessing approaches, therapeutic interventions, and supportive working environments.

Introduction

Significant changes within Europe over recent years, at political and financial levels, have had a substantial impact on many people’s lives (United Nations, Citation2018). One of the most important impacts has been the effect of the economic crisis on society and employability. In this study, the term “employability” refers to individual factors (employability skills and attributes, demographic characteristics, health and wellbeing, job seeking, adaptability and mobility), personal circumstances (household circumstances, work culture, access to resources) and external factors (demand and enabling support factors) which have a significant effect when a person is looking for work (McQuaid & Lindsay, Citation2005). Past research reveals high levels of youth unemployment in many European countries (Banerji et al., Citation2014). The youth unemployment rate pertains to a transition period from education into the labour market between the ages of 16 and 24. Although there has been a decrease in UK youth unemployment rates in the last few years, the statistics are still alarming, especially when compared to general employment rates. The recent youth unemployment rate in the UK was 11.3% between April and June 2018 (McGuiness, Citation2018). Of these youth, 16% were unemployed for long periods of 12 months or more. The youth unemployment rate in the UK is relatively low when compared with the average figures in the European Union (EU, 15.2%) and Euro Area (16.9%). However, it is still almost three times higher than the adult unemployment rate in the UK, which is around 4% (McGuiness, Citation2018).

According to the EU’s growth strategy, initiatives seeking to raise the level of employment among young people should include extra support for those experiencing complex health, emotional, social, or physical problems (Grammenos, Citation2013). This is unsurprising, given the considerable amount of research demonstrating that young people with complex needs have to contend with weak employability (Broad, Citation2003; Dixon & Stein, Citation2005; Moran et al., Citation2001), particularly in relation to lack of skills, insufficient support and unsuitable work conditions. For instance, Powell (Citation2018) reported that only 38.2% of youth with complex needs are in employment in the UK. This indicates that unemployment rate for those young people is almost six times higher than that for youth in general.

Whilst unemployment has negative consequences for many aspects of all young people’s lives, it has a greater impact on the lives and wellbeing of those with complex needs (The Prince’s Trust, Citation2014). Thirty-five per cent of young people facing unemployment report a variety of mental health problems, including panic attacks and suicidal thoughts (The Prince’s Trust, Citation2015). Many feel that they are not in control of their lives, have health issues, and face lower levels of future employability (Bell & Blanchflower, Citation2011; Bynner & Parsons, Citation2002). Equally, long periods of unemployment for young people with complex needs appear to have financial and psychological effects, such as, lower future incomes, gradual depreciation of acquired skills, sense of life dissatisfaction and unwillingness to work (OECD, Citation2013). Furthermore, even when employment is gained, this is often in part-time, low-paid, and low-skilled jobs (Powell, Citation2018), which make it difficult to plan a future-oriented career.

Complex needs and employability

Identifying people with complex needs leads to the construction of two broad groups that are different but interrelated (Rankin & Regan, Citation2004): those confronting health issues, and those with social exclusion issues. Firstly, when considering the health issues of people with complex needs, we use the term “complex needs” to refer to people with intellectual, physical, and multiple disabilities such as: learning disabilities; impairments of hearing, vision and movement; as well as epilepsy and autism, challenging behaviours, or mental health problems (Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2010; Scottish Executive, Citation2000). Secondly, complex needs might be due to social exclusion issues, including: high levels of deprivation, poverty, homelessness, imprisonment, unemployment, migration, literacy problems, high risk of crime behaviour, substance abuse and young people in care (Pantazis et al., Citation2006; Scottish Executive, Citation2005; Social Exclusion Unit, Citation2005; Stanley et al., Citation2005). Complex needs due to health and social issues are interrelated. A young person being affected by one adversity (either health-related or social) is likely to encounter other difficulties (The Prince’s Trust, Citation2004). And the cumulative nature of difficulties creates more complexity for young people, putting them at greater risk.

In this study, we use a systematic review to investigate strategies for helping young people with complex needs to transition into paid employment. Such strategies may include capacity-building interventions, including both vocational and life skills training, which might have an emancipatory role in young people’s lives, transforming their life experiences. These interventions might require a collaborative and collective approach to develop, implement and maintain the practices, and actively involve the young people themselves in the process. In order for these interventions to be successful, incorporating a close, therapeutic support system is likely to be a crucial element.

Thus, in this systematic review, we investigate the effects of the practices aimed at helping young people with complex needs to improve their employability, at the time the search was carried out. The objectives of the review are to:

Identify the factors affecting and strategies used to improve the employability of young people with complex needs.

Classify these strategies at the individual, community, and governmental levels.

Method

Search procedures

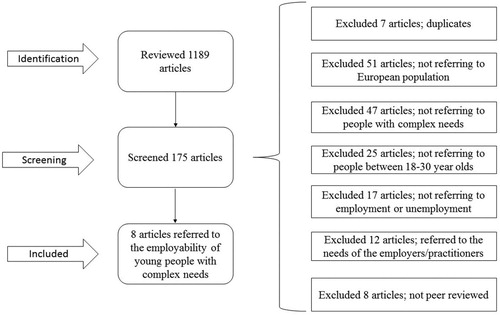

Twenty-one electronic databases were used to search for and identify studies published in English, between the year 2000 and 2017. These databases were: AMED – The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), Art Index Retrospective (H.W. Wilson), British Education Index, Business Source Premier, Child Development & Adolescent Studies, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Communication & Mass Media Complete, Criminal Justice Abstracts, eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), Education Abstracts (H.W. Wilson), Educational Administration Abstracts, E-Journals, ERIC, GreenFILE, Hospitality & Tourism Index, Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, PsycINFO, Regional Business News, SPORTDiscus, and Teacher Reference Center. The search terms were: “employ*” OR “unemploy*” AND “complex needs” in article abstracts. The initial search identified 1,189 articles. After specifying age limits to only include the ages 18–30 years old, the number of articles was reduced to 175.

Study selection and data extraction

The titles and abstracts of the 175 articles were screened for relevance to this review by two of the authors. Documents deemed relevant on the basis of the abstract review were retrieved in full text, examined, and compared against the following inclusion criteria for the review:

The study population was within the UK and Ireland.

The age range of the study population was 18–30 years.

The studies referred to people with complex needs as defined in the beginning of this review.

The studies referred to the employment or unemployment opportunities of people with complex needs.

The studies were about people with complex needs and not about the needs of employers or practitioners.

The studies were original.

As seen in , from 175 articles, finally the number of articles meeting the inclusion criteria was 8. This represents 7 studies, because two of the articles pertained to the same project (i.e. Dixon Citation2007; Wade & Dixon Citation2006).

Results

Objective 1: factors affecting and strategies used to improve the employability of young people with complex needs

The studies selected for this review summarise the factors affecting paid employment, and strategies for improving paid employment, of young people with complex needs. Specifically, they focus on disclosure of mental health issues at work; the combination of structures, guidance and support given to people with complex needs and learning disabilities to maintain paid employment; the vocational and life skills as factors of enrolment in education and paid work placements; the implementation of a multi-level partnership programme which provides paid employment; the importance of individual, practice and policy factors to participating in Education, Employment and Training (EET); the successful results of supported employment models for people achieving employment; and the activation of local authorities to help people leaving rehabilitation to re-enter employment.

Brohan et al. (Citation2014)

This is a qualitative study exploring disclosure of mental health issues in the work environment (see ). It summarised the beliefs and experiences of 45 people with complex needs collected through semi-structured interviews. The outcomes of the interviews were presented in a four-dimensional framework for improving the employability of young people with complex needs. The first dimension was the societal context, in which multiple needs are cited as conditions which can unjustly trigger public stigma. This refers to lack of knowledge, media stereotypes and different treatment. People’s unwillingness to work closely with someone with complex needs was widely referred to by study participants as a public reaction to not understanding the needs of people facing adversities. The second dimension described the employment environment in relation to barriers to work (i.e. difficulty in navigating disability benefits and lack of confidence), benefits of work (i.e. financial support, purpose in life and giving back to the community) and the role of the employer. The collaboration between employer and the employee with mental health issues was perceived as the prime factor in finding and maintaining a job. The third dimension was the personal impact of stigma, in relation to complex needs, on the evaluation of the employee’s work performance. The beliefs and experiences of participants ranged from mental health issues being a reason for not finding a job, or for poor performance, to it not being a problem at all. The fourth dimension primarily focused on the personal aspects of disclosure needs. This dimension emphasised the importance of trust, honesty, control and acceptance in the work environment. In particular, it was essential to build good communication systems and trust in the working context, as well as proving oneself first, and managing the tension between honesty and releasing too much information.

Table 1. Summary of Paper 1: Brohan et al. (Citation2014).

Gore et al. (Citation2013)

The Sustainable Hub of Innovative Employment for People with Complex Needs (SHIEC) project supported people with learning disabilities and complex needs in finding and maintaining paid employment. SHIEC’s team worked closely with managerial staff and frontline practitioners of eight regional service providers, to identify and support target groups with learning difficulties and complex needs. The regional providers were composed of residential schools, forensic services and challenging behaviour specialist settings. This study (see ) investigated the strategies that facilitated the employability of people with learning difficulties and complex needs in the first year of the SHIEC project, as reported by service providers and frontline practitioners through semi-structured interviews (n = 16). The findings revealed that supporting individuals with complex needs into employment requires: significant amounts of time, effort, commitment and resources; a shared value system at an organisational level; and ongoing social support mechanisms. The interviewees also emphasised the importance of recognition of their hard work to sustain their motivation. Furthermore, they reported that the SHIEC project not only facilitated the participating individuals with complex needs to find paid employment, but also transformed the culture and professional practices of participating organisations.

Table 2. Summary of Paper 2: Gore et al. (Citation2013).

Conway and Clatworthy (Citation2015)

Grow2Grow is a training programme in the south of England for young people with complex mental health needs, who are (or are at risk of being) not in education, employment or training (i.e. NEET youth) (see ). It offers vocational skills (e.g. market gardening, growing vegetables) and life skills (e.g. cooking, travelling independently) through training in an organic farm centre up to two days a week for up to two years. Simultaneously, weekly one-to-one therapeutic support is also provided. The programme is run by a multidisciplinary team including: psychologists, psychotherapists, occupational therapists, horticultural therapists and psychotherapy trainees. Of the 36 young people who started the Grow2Grow programme, 21 completed the programme and participated in the evaluation study (see ). The findings showed significant increases in social, emotional and behavioural outcomes of young people, as reported by programme practitioners. The majority of young people (17 out of 21) were enrolled in an education or paid work placement by the end of the programme. Creating a non-stigmatising and safe environment, and combining both training and therapeutic processes, were reported to be the main reasons for Grow2Grow’s success in engaging and sustaining young people with complex mental health difficulties in paid employment.

Table 3. Summary of Paper 3: Conway and Clatworthy (Citation2015).

Taylor et al. (Citation2004)

Vocational Opportunities in Training for Employment (VOTE) was a partnership programme which aimed to help young people aged 18–25 years old with complex needs (including learning disabilities, mental health problems, and physical disabilities), to improve their employment prospects in the labour market (see ). The programme started as an EU-funded initiative, however, it was subsequently coordinated and financed by local statutory and voluntary organisations in Belfast. VOTE supported young people to enter the employment market, provided skills, trained employers and parents regarding young people’s complex needs, and supported young people and employers in work placements. There were multiple projects conducted under the VOTE partnership. For example, one project was conducted by a team including full-time support workers, a development officer and a researcher. This particular project provided a range of specialist job skills training courses to young people with learning difficulties and also offered work experience opportunities. Young people who participated in this project gained qualifications in first aid, word processing, and “Working with Equal People”. Approximately 10% of participants found paid employment at the project’s conclusion. Other VOTE projects worked with school leavers, care-leavers and young people with physical disabilities. This paper reported the findings from its initial evaluation study across the multiple projects of VOTE. It was found that young people who joined VOTE projects had opportunities to develop and learn, as well as successfully perform in work placements with suitable support. The study also highlighted the importance of involving parents in the recruitment phase and maintaining regular contact with them. Investigating VOTE’s processes revealed helpful strategies for referrals and referral agents, including: the impact of public relation activities, familiarity with local services, and maintaining good communication. Furthermore, building trust-based relationships with local employers and matching young people’s needs with working environments were other strategies found to be effective in this study. Overall, building and maintaining successful partnerships across diverse organisations and agents were found to be the key factors for supporting young people with disabilities and complex needs.

Table 4. Summary of Paper 4: Taylor et al. (Citation2004).

Dixon (Citation2007)

This study (see ) investigated the risk and protective factors of successful career outcomes, during transition from care to independent living. The aim was to understand strategies for supporting care-experienced young people to participate in education, employment and training (EET). Through interview and survey methods, a mixture of data were collected from 106 young care leavers, their personal advisors and policymakers. The results of this study showed the low probability of young care leavers to be engaged in EET two months after leaving care (35% in education, 29% in training, 10% in employment) compared to school leavers in general (57% in education, 75% in training, 31% in employment). The sustainability of participation was another significant issue. Approximately half reported that their career progress over time had deteriorated or remained poor. Various strategies were suggested for improving the numbers of young people with complex needs participating in EET and maintaining engagement. These strategies were: promotion of a more co-produced interagency approach with a holistic view, negotiating the changes and challenges involved in transition, having a stable care background, using local businesses as local resources, a gradual shift into the career arena, focusing on education and career planning, and an increase in young people’s potential and options within the market. Engaging in education and training increased the participation of young people with additional needs in the labour market. Local authorities can boost engagement by developing appropriate policies and initiating/supporting collaborations with local businesses.

Table 5. Summary of Paper 5: Dixon (Citation2007), also described in Wade and Dixon (Citation2006).

Lynas (Citation2014)

Project Autism: Building Links to Employment (ProjectABLE) was a Northern Ireland/Belfast-based programme, which promoted the employability and life skills of young people with an Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC), using the Supported Employment Model (see ). This model is an effective tool to develop an individualised, flexible support system to help individuals secure meaningful employment. The main goals of ProjectABLE were: increasing work opportunities for young people with ASC, helping these young people to develop employment skills and preparing young people for the transition into employment. The five-step model included: engagement, placing, training, maintaining and progressing. In this programme, young people were trained in: developing social and communicational skills, identifying vocational opportunities, attending vocational training courses and education, and acquiring third-level educational qualifications (such as Degrees in Computer Science, Art, English Literature, History and Business Studies). This helped to promote their employability in administration or retail jobs, and to develop effective communication and social skills. The team, based across two organisations, included a coordinator and four support workers, who offered supported employment opportunities. The results of this study showed the benefits of the Supported Employment Model. These might be due to the consistent but flexible nature of the programme.

Table 6. Summary of Paper 6: Lynas (Citation2014).

Kavanagh and Lavelle (Citation2008)

This study looked at a Dublin-based residential recovery support service for people aged 18 years and over who also lived with multiple mental health issues and complex needs, including: co-existing alcohol and drug use, aggression, self-harm and treatment noncompliance (see ). The rehabilitation service provided recovery-focussed interventions, such as those aimed at helping people re-enter employment upon discharge. Of the 50 residents and former residents included in the study, 6% were in employment prior to placement. Following vocational rehabilitation, 60% were involved with training programmes and 10% participated in employment schemes. Results also showed that some new and old “long-stay” patients, with the most severe and enduring mental health problems and a history of multiple inpatient treatments, had extensive needs that could not be met by the programme.

Table 7. Summary of Paper 7: Kavanagh and Lavelle (Citation2008).

Objective 2: classification of the strategies used at individual, community, and governmental levels

The strategies used to promote the employability of people with complex needs, in the projects presented in this review, can be divided into four categories and at the individual, community and governmental levels: (1) skill-based approaches, (2) job/work experience accessing approaches, (3) therapeutic interventions and (4) a supportive working environment. The first category reported attempts by local authorities to create an organised, targeted service, by combining several service provider agencies (Wade & Dixon, Citation2006). The local authorities provided financial incentives for young people to participate in educational and training courses, as well as mentoring projects to provide a variety of work opportunities and support (Wade & Dixon, Citation2006). Additionally, the rehabilitation project provided re-engagement services, with the aim of helping people to become active in the labour market following poor mental health. This was achieved with a combination of recovery interventions and training programmes, in order to develop employment and life skills (Kavanagh & Lavelle, Citation2008).

The second category encompasses the actions taken to help people with complex needs gain employment or work experience. These strategies were found in three articles. The authors of these articles described how local authorities sought to promote the employment of people with complex needs. For example, the formation of SHIEC (Gore et al., Citation2013) where the main purpose was to organise a network of services willing to provide employment opportunities to people with complex needs.

The ABLE project initiative was financed by the Big Lottery Fund (2009–2014) and led by a voluntary organisation and registered charity. It was also delivered in other areas in Ireland together with a closely linked voluntary organisation. Furthermore the ABLE project initiative appeared to be extremely active in helping people with complex needs become employed (Lynas, Citation2014). The VOTE project, funded partly by the EU “Youthstart” employment programme, which promoted vocational opportunities for people with complex needs, was implemented in Ireland. It was coordinated by local statutory and voluntary organisations, and was partly managed and funded by regional statutory and voluntary organisations. This movement focused on training and supporting young people with complex needs in becoming employable, as well as educating employers and parents about people’s needs, and adapting the work environment to support employees with multiple difficulties (Taylor et al., Citation2004).

The third category refers to therapeutic interventions organised to improve the confidence levels of people with complex needs, in order to support their access to work. Grow2Grow trained and supported young people with difficulties, to acquire vocational and life skills in regional social enterprises, alongside the provision of therapeutic mental health support (Conway & Ginkell, Citation2014). Psychologists, psychotherapists, and occupational therapists involved in the project were trained to use developmental psychodynamic models and weekly one-to-one therapy was designed to engage young people with work.

The fourth category presents actions taken to create a supportive workplace environment for young people with complex needs. Specifically, it consists of individual initiatives, such as: employing young people dealing with difficulties, and the employers’ ability to make these young people feel sufficiently secure, particularly by creating trusting environments and facilitating good communication pathways to enable them to disclose their needs in an employment context (Brohan et al., Citation2014). Employers’ knowledge of and attitude towards complex needs seem to be key factors for implementing the strategies necessary for creating a supportive workplace for these young people.

In addition to individual initiatives taken to promote the employability of people with complex needs, it is necessary to present initiatives at the community and government levels. At the community level there are initiatives taken mainly by local agencies, such as the provision of financial motives to participate in education and training courses (Wade & Dixon, Citation2006), the networking of services to offer employment opportunities, and the support of regional social enterprises to help people with complex needs acquire vocational and life skills (Conway & Ginkell, Citation2014). At government level the initiatives refer to the development of a central agency in collaboration with local agencies to provide employment opportunities, which is strengthened by national policies (Dixon, Citation2007), the coordination of local statutory and voluntary organisations to train and support young people with complex needs to become employable, as well as educating employers and parents about people’s needs, and adapting the work environment to accept employees with multiple difficulties (Taylor et al., Citation2004).

Discussion

This review has shown that certain actions need to be taken in order to promote the engagement and inclusion of young people with complex needs in the labour market. The effectiveness of these strategies/approaches can be assessed by analysing the outcomes for young people with multiple difficulties, such as their desire to work and their actual participation in paid full-time or part-time employment. This review has helped identify four categories of actions taken to help people with complex needs become employed. The strategies range from skill-based approaches to supportive workplace environments. These have to work across multiple levels, from individual to community and government levels, in order to provide a holistic collection of initiatives, which aim to reduce youth unemployment for those with complex needs within the UK and Ireland.

At the community level, initiatives tended to focus on developing individual skills. Many projects have been established to help young people with complex needs become employed. As a result of this review, we have identified common structural tactics used in initiatives at the local authority level, to facilitate employability and encourage young people with complex needs to enter the labour market. The main shared characteristics of these projects are: a focus on providing vocational and life skills training to participants, an emphasis on a holistic approach, and establishing collaborations with local and multi-agency services, as well as with young people with complex needs themselves.

At the national level, it is interesting to note that our search did not retrieve any publications that considered the collective action or unionisation of young people with complex needs. We believe that giving young people access to this kind of collective support and help with politicisation could assist in moving beyond the promotion of individual access to employment experience. Connecting young people with complex needs to others in similar situations can help develop a sense of belonging, because they know they are not alone. Furthermore, helping to facilitate young people’s access to the political domain enables them to influence policymakers, which can potentially change the odds stacked against them due to their multiple layers of complex needs and systemic inequality. Accessing policymakers can establish a pathway by which young people with complex needs are able to change the odds and challenge the inequality, not just for themselves, but for others in similar situations as well. In addition, young people can be supported to manage responsibilities and obligations. They could collaborate with staff who can provide supported employment, and they might also be encouraged to spend more time on training and education courses.

At the individual level, perspectives on unemployment and complex needs have been gathered from participants and employers. The main responsibility for providing sustainable employment opportunities appears to be employers’ inclusive behaviours and attitudes, and their willingness to participate in training programmes about employing young people with complex needs. According to the third approach, described by us as “therapeutic interventions”, improving life and coping skills are essential in order to deal with the transition into employment. The interventions offered young people the opportunity to claim work placements independently. They also managed to find a place where they belonged, formed relationships with other young people with complex needs and their employers, and were able to focus on their successes.

Our review found hints of emancipatory approaches at a collective level. For example, actions concentrated on organising educational and training courses for people with complex needs in varying geographical areas, as well as education in whatever format, have long been identified as an emancipatory force (Freire, Citation1996). However, most of the education provided was technical in nature. Educating young people to understand more about the conditions of their own disadvantage and oppression is an obvious gap. Filling it may help them with the challenges they face. Most actions taken refer to local authorities or local voluntary organisations working to provide work placements and to form partnerships with other agencies, to support various needs. The extent to which employment brokerage initiatives included young people on their own staff or governance groups was unclear. Usually, state-level projects emphasise helping young people acquire qualifications and additional skills, which prepare them for the labour market.

Undoubtedly, well-structured support mechanisms are required to promote the employability of people with complex needs. In the framework of work promotion, service representatives who sought work placements for participants managed to reduce discrimination and stigma in the working environment by involving employers in training programmes. According to Protocol 12 of the European Convention of Human Rights, every person facing difficulties has the right to participate in inclusive paid employment without discrimination. In several cases, the working environment was adjusted to accommodate young people’s multiple needs. Adjustments were also made for employers to promote and empower these actions, producing an atmosphere of trust. The result was that young people felt safe enough to express their feelings (Ellison et al., Citation2003; Michalak et al., Citation2007) and were treated with acceptance (Goldberg et al., Citation2005; Owen, Citation2004).

This review has demonstrated the importance of having supported employment for people with complex needs. Furthermore, its necessity is revealed in the policy formulation and research designs, which are organised to tackle the unemployment of people faced with difficulties (Beyer & Robinson, Citation2009; Forrester-Jones et al., Citation2006; Kober & Eggleton, Citation2005). Most of the projects applied at a local level included supportive employment as an essential feature of helping young people with complex needs find and maintain jobs. Barriers for those working to facilitate supported employment included unpredictable difficulties arising from some of the young people’s complex needs, and payment issues (Ridley & Hunter, Citation2006; Wistow & Schneider, Citation2007).

In several articles, it was suggested that individuals with complex needs should be encouraged to engage with therapeutic support. Grow2Grow’s therapeutic approach helped people process the demands of a transition into work (Conway & Ginkell, Citation2014). Ultimately, the goal must be for society at large to tackle the shocking stigma and discrimination that people with complex needs experience daily, and to develop more inclusive, holistic practices as a way of life. However, as an immediate pragmatic step, at an individual level, therapeutic approaches have been shown to provide: psychological enhancement, coping strategies to withstand challenges, and development of self-esteem to encourage participation in society and to pursue the right to be employed (Bragg et al., Citation2013; Clatworthy et al., Citation2013). Besides therapeutic help, it is essential that people with complex needs have educational qualifications, to enter the labour market with a greater likelihood of being employed (Dixon, Citation2006). Research carried out in mental health services illustrated that employment is more likely to be achieved when clinical and vocational services are integrated, emphasising the need for a holistic approach (Harvey et al., Citation2013; Marshall et al., Citation2014).

Limitations and directions for future research on employing young people with complex needs

The review found only a few articles referring to government actions to promote employability (i.e. established policies promoting employability at the state level), revealing the need for more collective, collaborative and holistic interventions. Not all of the employability projects were successful in helping young people find paid work. Most projects contributed by engaging young people on courses to develop working skills or helping them gain work experience or voluntary work. It was not possible to ascertain whether or not young people were included on the staff teams of the brokerage projects, or indeed whether they were involved in project management. Both including them as staff and in governance roles on collaborative projects would result in even more potential employment for young people with complex needs, while simultaneously providing others with valuable role models.

A further point to make here is that the review criteria meant that some projects that we know to be successful from local evaluation data were not included in the review. For example, Project Search, which takes young people in their last year of education and immerses them in a work setting. It ensures that there is no break for students between school and work, so that students do not become unemployed at any point, and are transitioned into the identity of a working person. Participants learn employability skills and go on work placements every day to prepare them for paid work. Project Search has made significant inroads in supporting young people with complex needs to transition into work straight from school (http://www.projectsearch.us/). Project Search has good success rates and operates in many geographical locations. There may be other effective projects with no published evaluation which were overlooked in this review.

This review only covered initiatives for young people with complex needs, so no direct comparison can be made with young people without such needs, to assess which strategies are particularly helpful for those facing the most disadvantage. The analysis of all seven studies revealed that the employability projects designed at the governmental level were successful at helping young people get short-term paid work and engage with courses, but that they did not establish a political tactic to promote employability of other young people in similar situations more generally. For community level projects targeting the employability potential of young people with complex needs, greater success was achieved by harnessing the influential power of local authorities. Furthermore, the successful individual initiatives, such as supported employment, benefitted greatly from the cooperation of supportive and willing employers, facilitating young people’s participation in the work market. Employers’ knowledge, attitudes, and openness to young people’s involvement in decision-making are clearly key for young people with complex needs to make successful transitions into employment.

Conclusion

Every project designed to enhance employability in young people with complex needs that we have described had successful outcomes, such as: gaining full- or part-time paid jobs, voluntary work, or even just relevant, helpful work experience. To reiterate, it appears that to provide sufficient support for engaging and sustaining young people with complex needs in paid employment, a holistic approach is necessary where multiple stakeholders work collaboratively with young people, tackling issues at multiple domains of life, including knowledge, skills, attitudes and wellbeing. Participation in paid employment generates stronger feelings of satisfaction and functioning than other activities of daily living (Eklund et al., Citation2004). When young people with complex needs manage to enter a larger community setting, such as an employment environment, they benefit from enhanced social skills. This gives them the opportunity to improve their quality of life (Hutchison & McGill, Citation1998; Ochocka & Lord, Citation1998; Pedlar et al., Citation1999).

In order to achieve these outcomes, this review helps us conclude that there is a strong need for collective, collaborative and holistic interventions. The collective aspect of interventions should be seen as both bringing young people with complex needs together as an empowerment process, but also to support different agencies to work together with a shared focus and responsibility. For an impactful, collective intervention it is also essential that multiple agencies, including young people with complex needs, collaborate together; and we found multiple successful examples, especially at the community level. A holistic approach indicates interventions bringing vocational and clinical support and training together within a supportive work environment. Furthermore, the collective, collaborative and holistic nature of these interventions should be seen as fundamental aspects of a whole, where one cannot be put in place without considering the other two aspects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Angie Hart is Professor of Child, Family and Community Health, and Director of the Centre of Resilience for Social Justice, University of Brighton, UK. She teaches professional health and social care courses, and undertakes participatory research into resilience and inequalities. Angie directs a community interest company, Boingboing, which supports children, families and practitioners (www.boingboing.org.uk).

Agoritsa Psyllou is an independent researcher in Greece. She completed her PhD in Psychology and works as a special educator. She teaches on Distance Learning Masters’ Programmes at Frederick University in Cyprus, Greece, and conducts participatory research and literature reviews. Agoritsa’s research interests include school-based training programmes, development of emotional resilience and implementation of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) methods in children.

Suna Eryigit-Madzwamuse is a Senior Research Fellow and Deputy Director of the Centre of Resilience for Social Justice, University of Brighton, UK. Her work focuses on promoting the wellbeing and resilience of children, young people and their families, while considering their biological and contextual risk and protective factors, from a developmental perspective.

Becky Heaver is a Research Officer in the Centre of Resilience for Social Justice, University of Brighton, UK. She completed a Psychology PhD and now researches resilience for children, young people and families, using participatory research and literature reviews. Becky’s research interests include psychophysiology, recognition memory, self-advocacy and autism.

Anne Rathbone is the Senior Training and Consultancy Manager at Boingboing. Anne’s work focusses on inclusive engagement and co-production. She is undertaking PhD research at the University of Brighton, working with young co-researchers with learning disabilities, to explore their own experiences of resilience, to undertake self-directed collective action to challenge adversity.

Simon Duncan is Trainer and Project Worker for Boingboing. Simon gives presentations about being resilient with a physical disability to a variety of audiences, supports a co-productive project researching drought resilience in South Africa, and contributes to systems-change around how young people’s mental health issues are viewed and addressed in Blackpool, UK.

Pauline Wigglesworth is Programme Lead for the Big Lottery Funded HeadStart Blackpool, UK. Led by Blackpool Council, HeadStart Blackpool is a co-produced whole-town approach to build resilience in and support the mental health of young people aged 10–16. Pauline has a background in voluntary and statutory sector work with adults and young people.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Banerji, A., Saksonovs, S., Lin, H., & Blavy, R. (2014). Youth unemployment in advanced economies in Europe: Searching for solutions. International Monetary Fund.

- Bell, D. N. F., & Blanchflower, D. G. (2011). Young people and the great recession. IZA.

- Beyer, S., & Robinson, C. (2009). A review of the research literature on supported employment: A report for the cross-government learning disability employment strategy team. Cabinet Office.

- Bragg, R., Wood, C., & Barton, J. (2013). Ecominds: Effects on mental wellbeing. MIND.

- Broad, B. (2003). After the Act: Implementing the children (leaving care) Act 2000 (Monograph, No. 3). De Montfort University.

- Brohan, E., Evans-Lacko, S., Henderson, C., Murray, J., Slade, M., & Thornicroft, G. (2014). Disclosure of a mental health problem in the employment context: Qualitative study of beliefs and experiences. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 23(3), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796013000310

- Bynner, J., & Parsons, S. (2002). Social exclusion and the transition from school to work: The case of young people not in education, employment, or training (NEET). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(2), 289–309. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1868

- Clatworthy, J., Hinds, J., & Camic, P. M. (2013). Gardening as a mental health intervention: A review. Mental Health Review Journal, 18(4), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-02-2013-0007

- Conway, P., & Clatworthy, J. (2015). Innovations in practice: Grow2Grow – engaging hard-to-reach adolescents through combined mental health and vocational support outside the clinic setting. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20(2), 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12079

- Conway, P., & Ginkell, A. (2014). Engaging with psychosis: A psychodynamic developmental approach to social dysfunction and withdrawal in psychosis. Psychosis: Psychological, Social and Integrative Approaches, 6, 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2014.968857

- Dixon, J. (2006). Pathways to work experience: Helping care leavers into employment. A review of the York cares starting blocks project. University of York.

- Dixon, J. (2007). Obstacles to participation in education, employment and training for young people leaving care. Social Work & Social Sciences Review, 13(2), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1921/19648

- Dixon, J., & Stein, M. (2005). Leaving care: Through care and aftercare in Scotland. Jessica Kingsley.

- Eklund, M., Hansson, L., & Ahlqvist, C. (2004). The importance of work as compared to other forms of daily occupations for wellbeing and functioning among persons with long-term mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(5), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COMH.0000040659.19844.c2

- Ellison, M. L., Russinova, Z., Donald-Wilson, K. L., & Lyass, A. (2003). Patterns and correlates of workplace disclosure among professionals and managers with psychiatric conditions. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 18, 3–13.

- Forrester-Jones, R., Carpenter, J., Coolen-Schrijner, P., Cambridge, P., Tate, A., Beecham, J., Hallam, A., Knapp, M., & Wooff, D. (2006). The social networks of people with intellectual disability living in the community 12 years after resettlement from long-stay hospitals. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(4), 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00263.x

- Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (2nd ed.). Penguin.

- Goldberg, S. G., Killeen, M. B., & O’Day, B. (2005). The disclosure conundrum: How people with psychiatric disabilities navigate employment. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 11(3), 463–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8971.11.3.463

- Gore, N. J., Forrester-Jones, R., & Young, R. (2013). Staff experiences of supported employment with the sustainable hub of innovative employment for people with complex needs. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(3), 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12033

- Grammenos, S. (2013). European comparative data on Europe 2020 & people with disabilities. Centre for European Social and Economic Policy.

- Harvey, S. B., Modini, M., Christensen, H., & Glozier, N. (2013). Severe mental illness and work: What can we do to maximise the employment opportunities for individuals with psychosis? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47(5), 421–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867413476351

- Hutchison, P., & McGill, J. (1998). Leisure, integration, and community (2nd ed.). Leisurability.

- Kavanagh, A., & Lavelle, E. (2008). The impact of a rehabilitation and recovery service on patient groups residing in high support community residences. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 25(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0790966700010764

- Kober, R., & Eggleton, I. R. C. (2005). The effect of different types of employment on quality of life. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(10), 756–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00746.x

- Lynas, L. (2014). Project ABLE (Autism: Building Links to Employment): A specialist employment service for young people and adults with an autism spectrum condition. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 41(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-140694

- Mansell, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2010). Deinstitutionalisation and community living: Position statement of the comparative policy and practice special interest research group of the international association for the scientific study of intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(2), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01239.x

- Marshall, T., Goldberg, R. W., Braude, L., Dougherty, R. H., Daniels, A. S., Ghose, S. S., & Delphin-Rittmon, M. E. (2014). Supported employment: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300262

- McGuiness, F. (2018). Youth unemployment statistics (Briefing Paper N:5871). House of Commons Library.

- McQuaid, R. W., & Lindsay, C. (2005). The concept of employability. Urban Studies, 42(2), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000316100

- Michalak, E. E., Yatham, L. N., Maxwell, V., Hale, S., & Lam, R. W. (2007). The impact of bipolar disorder upon work functioning: A qualitative analysis. Bipolar Disorders, 9(1–2), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00436.x

- Moran, R. R., McDermott, S., & Butkus, S. (2001). Getting a job, sustaining a job, and losing a job for individuals with mental retardation. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 16, 237–244.

- Ochocka, J., & Lord, J. (1998). Support clusters: A social network approach for people with complex needs. Journal of Leisurability, 25, 14–22.

- OECD. (2013). Tackling long-term unemployment amongst vulnerable groups.

- Owen, C. L. (2004). To tell or not to tell: Disclosure of a psychiatric condition in the workplace [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Boston University.

- Pantazis, C., Gordon, D., & Levitas, R. (2006). Poverty and social exclusion in Britain. The Policy Press.

- Pedlar, A., Haworth, L., Hutchison, P., Taylor, A., & Dunn, P. (1999). A textured life: Empowerment and adults with developmental disabilities. Wilfrid Laurier University.

- Powell, A. (2018). People with disabilities in employment (Briefing Paper N: 7540). House of Commons Library.

- Rankin, J., & Regan, S. (2004). Meeting complex needs in social care. Housing, Care and Support, 7(3), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1108/14608790200400016

- Ridley, J., & Hunter, S. (2006). The development of supported employment in Scotland. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 25, 57–68.

- Scottish Executive. (2000). The same as you? A review of services for people with learning disabilities.

- Scottish Executive. (2005). Delivering for health.

- Social Exclusion Unit. (2005). Transitions: Young adults with complex needs. A social exclusion unit final report. Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

- Stanley, N., Riordan, D., & Alaszewski, H. (2005). The mental health of looked after children: Matching response to need. Journal of Health and Social Care in Community, 12(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00556.x

- Taylor, B. J., McGilloway, S., & Donnelly, M. (2004). Preparing young adults with disability for employment. Health and Social Care in the Community, 12(2), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0966-0410.2004.00472.x

- The Prince’s Trust. (2004). Reaching the hardest to reach.

- The Prince’s Trust. (2014). Macquire Youth Index 2014. https://www.princes-trust.org.uk/help-for-young-people/news-views/youth-index-2014

- The Prince’s Trust. (2015). The Prince’s Trust Youth Index 2015. https://www.princes-trust.org.uk/support-our-work/news-views/anxiety-is-gripping-young-lives

- United Nations. (2018). World economic situation and prospects 2013.

- Wade, J., & Dixon, J. (2006). Making a home, finding a job: Investigating early housing and employment outcomes for young people leaving care. Child and Family Social Work, 11(3), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00428.x

- Wistow, R., & Schneider, J. (2007). Employment agencies in the UK: Current operation and future development needs. Health Social Care Community, 15, 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00667.x