ABSTRACT

Employment guidance theory and praxis promote long-term career development and access to decent work and sustainable jobs, yet the focus of public employment services in recent times has been influenced by policy matters of activation, conditionality and rapid job placement. While effective for some, it has been less effective for workers exposed to negative impacts of social and economic development. COVID-19-related unemployment has highlighted the need for employment guidance mechanisms that facilitate inclusive and resilient labour forces. Drawing on previous developments in employability approaches, this paper presents a conceptual analysis of employment guidance, integrating it within a work-first to life-first employability continuum. We propose an expansion of theory-informed employment guidance in national public employment services towards work-life employability for all.

Introduction

The sudden shock of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on unemployment across the globe has highlighted the ongoing formidable risk to economic stability, livelihoods and well-being. Its impact has been abrupt with established careers disrupted, youth careers stunted and those in low skill work particularly affected. It differs from previous crises as societies are “on hold” in the short term, with a limited vision of a post-COVID-19 world, and increased uncertainty about how labour markets and careers will endure. It has highlighted the vulnerability of labour-related economic activity, questioned how work is organised and conducted, and drawn attention to sectors most vulnerable to this new societal challenge. During the first phase of lockdown many countries froze their public employment services (PES). As economies re-open, COVID-19 will test the capacity of governments across the world to respond to what unemployed workers need to enable them back to employment (Furman Citation2020; OECD, Citation2020). This highlights the need for a PES primed to deal with future societal challenges including not only the pandemic but those arising from climate change, globalisation and technological disruption.

The challenge in developing an active response to mass pandemic unemployment is to find mechanisms that support all unemployed people to find good jobs. The risk post-pandemic is that an “any job is better than no job” mantra may prevail due to political, economic and societal pressures to curb welfare caseloads (McGann, Murphy and Whelan, Citation2020). The ambition should be decent work that enhances well-being and provides opportunity for all (Duffy, Blustein, Diemer, & Autin, Citation2016). This requires mechanisms to facilitate the development of inclusive and resilient labour forces, supporting and protecting workers at all career stages. The enabling potential of employment guidance in caring for a distressed labour force and responding to varying individual needs has never been more important.

Motivated to contribute to understanding the underdeveloped concept of employment guidance, and how it relates to different models of PES, this paper develops, from an employability continuum, an employment guidance typology, which we then contextualise as a set of employment guidance models nestled into a wider employability PES framework. We start by defining employability and employment guidance within a lifelong guidance context and outline its role within PES. We describe Active Labour Market Policy (ALMP) and the range of policy options available to policymakers and advocate for policies which promote decent work and sustainable labour market access, exploring the role of employment guidance within this context. Adding to previously developed typologies we then present a typology of ALMP options available to policymakers from work-first to life-first to support all unemployed on “a high road back to work” (Murphy, Whelan, McGann & Finn, Citation2020). The focus of our analysis then shifts to the use of selected career guidance models and theories that seek to explain how people develop and behave in their career development. These theories provide a framework for understanding career-related behaviours and experiences. Finally, acknowledging the post-pandemic pull on resources and intuitive appeal of a work-first approach in serving those most “job-ready”, we argue for the expansion, rather than reduction of employment guidance in PES.

Distinguishing career guidance and employment guidance

Career guidance has been found to have significant personal, social, economic and work-related benefits (OECD, Citation2004). It helps individuals reach their potential, makes economies more efficient and contributes towards fairer societies (Cedefop, Citation2019). Career guidance is lifelong and continuous, taking place within education and employment systems. It has been shown to be effective in re-engaging unemployed adults in the labour market and supporting young people to transition to the world of work (Hooley, Citation2017; Redekopp, Hopkins, & Hiebert, Citation2013; Sheehy, Kumrai, & Woodhead, Citation2011). In a recent joint statement Cedefop, the OECD, ILO, UNESCO, the European Commission, and the ETF encourage governments to invest in career guidance, understood as

services which help people of any age to manage their careers and to make the educational, training and occupational choices that are right for them. It helps people to reflect on their ambitions, interests, qualifications, skills and talents – and to relate this knowledge about who they are to who they might become within the labour market. (Cedefop, Citation2019, p. 2)

In many countries, employment guidance services are located within PES affording PES significant influence on the extent and nature of the career guidance available to citizens, particularly adults (Sultana & Watts, Citation2006). While generic structures and practices exist across countries, individual labour markets and settings require tailored approaches to meet their specific employability needs. Similarly, career guidance services vary according to national contexts and operational systems within PES. Arnkil, Spangar, and Vuorinen (Citation2017b) argue for the increased role of PES in supporting, developing and maintaining people’s abilities to make employment-related connections, and to “craft” their careers. As new societal challenges lead to more diversified careers within evolving labour markets, the challenge for guidance services to offer tailored supports to meet individual need, enhance employability and connect people to labour demand becomes more complex. Neglecting this challenge could lead to poor employment outcomes, contributing further to persistent and significant “decent work” deficits identified by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and to poor psychological health and well-being associated with unemployment and poor work (Butterworth, Leach, McManus, & Stansfeld, Citation2013; Paul & Moser, Citation2009).

Some critics argue that many PES have been singularly focused on employment outcomes rather than a broader focus on career development. For example, Borbély-Pecze and Watts (Citation2011) describe PES employment guidance as predominately labour market focused, targeting short-term outcomes related to immediate entry into employment. It is activation-orientated and directional tending to focus on particular target-groups, especially the unemployed. Arnkil et al. (Citation2017b), however, recommend partnership-oriented PES offering holistic services that foster relevant skills and enable jobseekers to secure rewarding career pathways. They favour a wider career counselling approach within PES which aims for longer-term outcomes including the development of employability and career management skills, leading to sustainable employability across the lifecycle. This client-centred approach is already more widely available in education settings and to those who purchase private career advice (Borbély-Pecze & Watts, Citation2011). However, within PES, employment guidance is often blended with functions of gatekeeping and policing of public resources, both helping the individual make career choices while also making “institutional decisions about the individual” (OECD, Citation2004, p. 58) and thus weakening and diluting its very purpose. This suggests that clients of PES who are generally unemployed may be at a disadvantage, and questions the democracy of employment guidance which does not respect individual autonomy (Murphy et al., Citation2020).

The place of career guidance within PES has always been problematic (Sultana & Watts, Citation2006). Tensions exist between the longer-term focus of career guidance towards sustained employability and the short-term focus of PES in supporting jobseekers into employment as quickly as possible. Brante (Citation2014) identifies those working in the field of career guidance in PES as belonging to “human service professions” who manage and deliver services of the welfare state while guided by a “professional logic” which justifies their focus on social justice and allows them to act for the individual.

The level and range of guidance provision in PES is generally related to PES organisational goals, with some services provided in-house, while others may be contracted or outsourced (Borbély-Pecze & Watts, Citation2011). While limited employment guidance may have suited PES organisational goals heretofore, the rapid pace of societal change is impacting how people access, maintain and transition in employment, creating a far more complex labour market environment. In responding to these challenges, employment guidance will require a conceptual shift in how it supports individuals to withstand new risks, such as dealing with periods of unemployment, loss of income, deskilling and social exclusion. As Barnes, Bimrose, Brown, Kettunen, and Vuorinen (Citation2020) remind us “those without the resources or prepared for changes are vulnerable”.

Employability and labour market policy approaches

Often described as a “slippery” concept (Green et al., Citation2013, p. 11), employability – a central strategic pillar and goal of the European Employment Strategy – remains difficult to define. Much of the vagueness derives from a focus on either supply-related factors, reflecting the characteristics of the individual, or wider demand-related factors which influence the labour market. McQuaid and Lindsay (Citation2005) argue that employability should be defined more broadly than supply or demand as it is influenced by both these factors. Likewise, Green et al. (Citation2013) conceptualise employability as “gaining, sustaining and progressing in employment” (p. 11), thereby supporting Kellard et al.’s (Citation2001) notion of sustainable employment and Van der Heijden and De Vos’ (Citation2015) sustainable careers, which go beyond simply getting people into work.

The activation literature on employability approaches typically distinguishes between two ideal types of ALMP: “work-first” and “human capital development” (Bonoli, Citation2010; Dean, Citation2003; Lindsay, McQuaid, & Dutton, Citation2007; Peck & Theodore, Citation2000; Värk & Reino, Citation2018). Drawing on the seminal work of Peck and Theodore (Citation2000), Lindsay and colleagues (Citation2007) advance this dualistic typology comparing “work-first” and “human capital development” across five dimensions: rationale, programme targets, intervention models, relationship to the labour market, and relationship with individuals (see ).

Table 1. Expanded features of employability approaches.

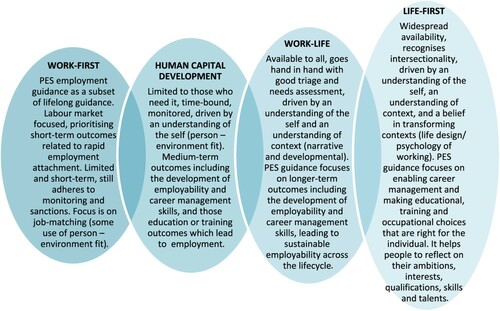

Bussi (Citation2014) further developed this typology by going beyond work-first and human capital, adding a capability approach to envisage further the objectives and principles underpinning employability approaches. She goes beyond the macro objective of “more people into employment” as sought by the “work-first” and “human capital” approaches, focusing instead on individual needs, aspirations and functions, and aiming at human flourishing and individual’s capabilities to achieve valued beings and doings (Alkire, Citation2008; Bussi, Citation2014). In , we build upon the dualistic typology and the work of Bussi to conceptually expand the notion of employability and to realise its potential breadth.

An Employability Continuum

Work-first approaches prioritise rapid labour market attachment based on the assumption that any job is better than none (Dean, Citation2003). More than this, they emphasise individual job-search effort as the key pathway to employability, leading to the criticism that such approaches individualise and mischaracterise the nature of workforce exclusion by reducing unemployment to “a simple matter of labour market supply and demand” (Goodwin-Smith & Hutchinson, Citation2015) and locating the source of labour market exclusion in a lack of motivation or effort on the part of individuals. The Human Capital Development model by comparison moves beyond work-first thinking, aiming to facilitate skill and competence development, thus improving sustainable access, long-term employability and in-work transitions (Peck & Theodore, Citation2000). It emphasises links to well-funded education and training and recognises the importance of integrated services (e.g. links to health providers, care) to address work-related barriers (Lindsay, Citation2014). Dean (Citation2003) highlights its social inclusion function as it “reinserts” those marginalised from the labour market into employment and society.

A further development of employability approaches is the Work-Life Balance model informed by the capability approaches of Sen and Nussbaum. It recognises the need to work as an essential need within an individual’s life, but only insofar as it is capability and well-being enhancing. It recognises participation in meaningful work as a key component of well-being for most people but in doing so prioritises well-being over employment. This entails a focus on empowering people “to lead the life and perform the job they have reason to value” (Orton, Citation2011, p. 356) which, in turn, depends on ALMP contexts that allow people freedom to choose. Respecting the agency of individuals becomes a central component of employment guidance, motivating co-production approaches in which employment pathway plans are co-designed with clients who retain a right to refuse to participate in activation programmes. While skills and knowledge may be exploited in the Human Capital approach, the Work-Life approach promotes capabilities as choice and well-being enhancing. Moreover, its multi-dimensional nature sees the individual within a life context, understanding employment participation needs as integrated with participation in other spheres of life. Thus it uses holistic and tailored individual coaching to attend to people’s work-life balance needs and (career) aspirations, promoting life-long learning and long-term career development (Murphy et al., Citation2020).

An expanded notion of Work-Life is the Life-First approach defined by Dean, Bonvin, Vielle, and Farvaque (Citation2005) as a holistic approach, prioritising the life-needs of individuals above an obligation to work (Dean, Citation2003). It promotes the right (not) to work, rather than the obligation to work, and emphasises human capabilities as ways to realise this right. It acknowledges time (long-term and sustained) and space to realise potential and to resolve life problems as they arise, and recognises the fundamental issue of care (to be cared for and to care for). Appreciation of the life needs of people who face multiple challenges, who may be vulnerable and marginalised in the labour market and in society, is balanced with the importance of work. Viewed from this perspective, ALMPs should aim to minimise “involuntary unemployment” and provide “opportunities for those who want to work”, but “without actively promoting employment as the best choice for individuals” (Laruffa, Citation2020, p. 6).

Using an employability continuum, we position the dominant Work-First model at one end and the Life-First capability-informed model at the other. Between these models are the Human Capital Development and the Work-Life Balance models (see ).

While these typologies provide macro-level descriptions of discrete employability policy approaches, they are limited in explaining the variety of programmes and their often-nuanced implementation. Influential frameworks allow further examination of these approaches in terms of the extent of policy use (i.e. enabling, regulatory, and compensation policies) (Brodkin & Marston, Citation2013) and policy impact (incentive reinforcement, employment assistance, occupation, up-skilling) (Bonoli, Citation2010). However, the international trend has been towards reinforcing more regulatory and disciplinary aspects of policy, while de-emphasising their enabling aspects (Brodkin & Marston, Citation2013).

Implementing labour market policy

In most countries, PES provide employment assistance in the form of welfare payments and active labour market supports with the aim of enabling re-employment. Policy makers have a range of options and strategies available to them to support employability but considerable variation in how unemployment is understood and characterised can lead to fundamentally different ALMPs and programmes (Lindsay, Citation2014).

In the current COVID-19 context people need immediate supports to cope with the distress of sudden unemployment and the phased resumption of the economy. Waddell and Burton (Citation2006) highlight the risk posed by unemployment to occupational and overall well-being. Others emphasise the negative health and societal impacts of unemployment, with both psychological well-being and subsequent re-employment shown to be negatively affected (Paul & Moser, Citation2009; Wanberg, Citation2012). These unemployment effects are often multiple and include decreased well-being, loss of confidence, low self-esteem and decreased self-efficacy, all of which can act as barriers to re-employment as they affect levels of motivation and job-seeking strategies (Eden & Aviram, Citation1993). Warr (Citation1987) describes unemployment as a type of anxiety-provoking existence, as periods of unemployment create uncertainty where it is difficult to predict and plan for the future.

For these reasons, we must carefully consider the range of policy options available and their implementation through PES in terms of impact on well-being and employability. The post-COVID-19 challenge for PES is how to refocus, to support people through this and future transitions, into potentially more uncertain labour market environments, as they consider the implications of returning to work and, for some, the reality of longer-term job loss.

Defining approaches to employability

Labour market programmes across the western world have increasingly shifted towards a common “work-first” approach prioritising job search and job placement, with some element of compulsion (Dean, Citation2003). More recently this singular “workfarist” orientation has been driven by discourses and politics of austerity following the last financial crisis (Heyes, Citation2013). Characterised by intensive job search, it aims to move people from welfare into unsubsidised jobs in the shortest time possible, proposing that any job is better than no job (Mead, Citation2003). It uses short education, training and work experience to overcome barriers to employment while also monitoring jobseekers' levels of activity and compliance, using sanctions rather than trust (Sol & Hoogtanders, Citation2005).

Of course, “work-first” support may benefit some people displaced by the pandemic unemployment crisis to the extent that it helps them to “maintain contact with the labour market and move back into work as quickly as possible” (Wilson, Cockett, Papoutsaki, & Takala, Citation2020). However, it has proven less effective for more vulnerable workers who are often exposed to the negative impacts of social and economic development, such as low wage and precarious work. Its critics argue that it does little to systematically assist those with complex barriers focusing instead on sanctions and compliance (Dean, Citation2003; Lindsay, Citation2010). Martin (Citation2015) observes that even when work-first approaches have proven effective, continuing doubts remain about the kinds of career opportunities that work-first approaches lead to. Therefore, we must be mindful of how we use work-first assistance, with whom, and to what end. While it may be intuitively appealing, applying “work-first” to all unemployed people requires careful implementation, focusing on transitions to decent work. The quality of the support is critical, and many will need additional assistance beyond job-search support. With this in mind, we present our expanded model of employability and employment guidance which opens exploration of alternative options available within ALMPs.

Towards an expanded model of employability and employment guidance

In this paper, our analysis is conceptual and analytical. We contribute to the model described above by expanding the traditional dualistic typology to emphasise a broader range of ALMP choice. presents the theoretical and practice developments outlined in existing research on work-first, human capital and capability-informed activation policy and employability approaches (Bussi, Citation2014; Lindsay et al., Citation2007) and includes the capability-informed work-life and life-first approaches proposed by Dean (Citation2003) and by Dean et al. (Citation2005) respectively. We add to current understanding of the “how to” of employability approaches by analysing the potential role of employment guidance within each of the four types. The typology combines the five dimensions proposed by Lindsay et al. (Citation2007) and the additional four offered by Bussi (Citation2014). We advance the typology by including two further “employment guidance” oriented dimensions; the “missing middle” and “the role and extent of employment guidance”.

The first additional dimension relates to what Brodkin and Marston (Citation2013) calls the “missing middle” of policy implementation. Existing approaches tend to focus on inputs (the policy), or outcomes (job placement), with very little, if any, investigation of processes occurring in between. Our analysis provides an overview of implementation practices across the four employability types. It outlines, for example, the highly administrative mechanisms of the Work-First model, focused on responsibilisation and compliance, and influenced by New Public Management where attempts to marketise services result in reducing availability, narrowing objectives and eroding professionalism (Hooley, Sultana, & Thomsen, Citation2018). Moving across our continuum, implementation broadens in scope, allowing for self-reflection and self-knowledge creation, building individual biographies, and providing tools to enable people to realise well-being and their career potential (Hooley et al., Citation2018).

The second dimension focuses on the potential use of employment guidance across the four employability approaches. Having an understanding of how people make career choices provides a system to help people find work and build careers (Sharf, Citation2013). Career theories provide a framework for understanding career-related behaviour and the human experience of careers. We argue for the inclusion of career theory in the development of appropriate, inclusive, employment guidance within national PES. The challenge now is for a broadening of employment guidance from traditional Person-Environment Fit models to the more holistic and lifelong approaches underpinning career counselling. offers a deeper understanding of where and how employment guidance fits into employability continuums.

Many influential career theories (e.g. Person-Environment Fit, Person-centred) have shaped career guidance practice in the last century, focusing largely on internal and individual-level factors. More recent theories (e.g. the Psychology of Working Theory, Social-Cognitive Career Theory) recognise the importance of contextual and structural factors, for example, the changing world of work, the life needs of workers, workforce demographics, the employment relationship and the “new realities” of careers (Tomlinson, Baird, Berg, & Cooper, Citation2018). Jobseekers must have the skills to survive and adapt within an increasingly changing labour market, where traditional linear careers (i.e. bounded within the same organisation) are steadily being eroded.

While we know the negative impacts that unemployment unleashes, career theories offer a way of thinking about people in careers and how they can be supported back into work. Employment guidance in PES could benefit from these theories, offering more tailor-made approaches which recognise the psychological and well-being impacts of unemployment and poor work, the complex interactions of individual (e.g. personal attributes) and environmental (e.g. opportunities, resources) variables that form career trajectories, and the supportive conditions (e.g. impartial guidance) that facilitate career development over the life course. Bimrose (Citation2013) reminds us of the old adage “Theory without practice is meaningless, but practice without theory is blind”.

For example, Savickas's narrative life design paradigm reflects a shift towards a more holistic Work-life approach where “people use stories to organize their lives, construct their identities, and make sense of their problems” (Citation2015, p. 9). Applying this approach, we move beyond states or traits, and emphasise context, processes, complexity, meaning making and life-long authoring of careers.

Similarly, employment guidance practice in Work-life and Life-first approaches could be strengthened by the Psychology of Working Theory (Blustein, Citation2013; Duffy et al., Citation2016) which acknowledges the work-based experiences of people on the “lower rungs of the social position ladder” (p. 127) and enables adaptive framing of the causes of work struggles. Blustein recommends a theoretical and praxis shift towards inclusivity of the experiences and psychological needs of economically vulnerable groups, advocacy for decent work, and sensitivity to diversity and socioeconomic disadvantage.

Conclusion

The current predominately work-first informed ALMP, focused on productivist short-term labour market outcomes, is limited in its capacity to meet the more urgent post-COVID-19 needs of all unemployed or to adequately support workers to tackle new societal challenges. Labour forces globally are being radically transformed by processes of globalisation, new forms and patterns of work organisation, and technological disruption. While a work-first model may be intuitively appealing, it needs to be exercised cautiously and targeted at transitions to “high-quality” rather than any employment. A work-life approach for those more distant from the labour market would require a shift in policy which could have significant implications for current administrative systems. It would also require a shift in ideology favouring workers and families over the economy and business. Achieving the right balance between caring for the labour force and re-igniting economies will require a careful and delicate strategy. Barnes and colleagues (Citation2020) recommend giving “fresh policy impetus” to career guidance policy and practice in education, training, youth and employment policies, emphasising professionalism and quality. Developing a wider range of employment guidance practices nestled in employability approaches might serve as an example of the policy stimulus required to build sustainable and inclusive labour markets into a riskier and more uncertain future.

Acknowledgment

The views expressed are those of the authors alone. Neither Maynooth University, the European Commission nor Irish Research Council is responsible for any use that may be made of the information in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nuala Whelan

Nuala Whelan is a post-doctoral researcher on the ACA PES: A Collaborative Approach to building a Public Employment Service project at Maynooth University Social Science Institute (MUSSI), Ireland. She is a Chartered Work and Organisational Psychologist who has worked for 20 years as a practitioner in community-based employment services with clients disadvantaged in the labour market. Her main research interests centre on employability, employment service effectiveness, career guidance models and practice, collaborative working, policy implementation and the potential value of enhancing human capacity for personal, organisational and societal impact. Her current research involves mapping a public employment eco system in Ireland and designing an employment guidance tool kit and metric for practitioners working with those most distant from the labour market.

Mary P. Murphy

Mary Murphy is Professor of Political Science and coordinator of the BA Politics and Active Citizenship in the Department of Sociology at Maynooth University, Ireland. Her research interests include labour market and social security policy, power and civil society, and gender. Her books include Towards a second republic (with P. Kirby, Pluto Press 2011) and The Irish Welfare State in the twenty-first century (co-edited with F. Dukelow, Palgrave 2016). A contributor to national policy debate, she was a member of the National Expert Advisory Group on Taxation and Social Welfare 2011–2014 and the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission 2013–2017. In 2019, she was appointed by President M.D. Higgins to the Council of State.

Michael McGann

Michael McGann is a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Research Fellow in the Department of Sociology and Social Sciences Institute at Maynooth University, Ireland. He specialises in the sociology of work and social policy on employment, with a particular focus on issues related to welfare-to-work and the marketisation of public employment services as well as ageing and employment. His current research involves a study of the governance of activation in Ireland, looking at the impact of recent marketisation reforms on how public employment services are delivered. Before joining Maynooth University Michael was Research Fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne, Australia, for several years. He has also previously worked as a researcher with the Parliament of Victoria (Australia) and with third sector organisations in Australia.

References

- Alkire, S. (2008). Using the capability approach: Prospective and evaluative analyses. In F. Comin, M. Qizilbash, & S. Alkire (Eds.), The capability approach: Concepts, measures and applications (pp. 26–50). Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492587.002.

- Arnkil, R., Spangar, T., & Vuorinen, R. (2017a). European Network of public employment services mutual learning: PES Network seminar ‘career guidance and lifelong learning’ 28-29 June 2017. Discussion paper. Brussels: European Commission.

- Arnkil, R., Spangar, T., & Vuorinen, R. (2017b). Practitioner’s toolkit for PES building career guidance and lifelong learning.

- Barnes, S. A., Bimrose, J., Brown, A., Kettunen, J., & Vuorinen, R. (2020). Lifelong guidance policy and practice in the EU: Trends, challenges and opportunities. Final report. Luxembourg: European Commission. doi:https://doi.org/10.2767/91185.

- Bimrose, J. (2013). Theory for guidance practice. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/ngrf/effectiveguidance/improvingpractice/theory/.

- Blustein, D. L. (2013). The Oxford handbook of the psychology of working. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bonoli, G. (2010). The political economy of active labor-market policy. Politics & Society, 38(4), 435–457. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329210381235

- Borbély-Pecze, T. B., & Watts, A. G. (2011). European public employment services and lifelong guidance. Brussels: European Commission Mutual Learning Programme for Public Employment Services.

- Brante, T. (2014). Den professionella logiken. Hur vetenskap och praktik förenas i det moderna kunskapssamhället. Stockholm: Liber.

- Brodkin, E. Z., & Marston, G. (2013). Work and the welfare state: Street-level organizations and workfare politics. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Bussi, M. (2014). Going beyond work-first and human capital approaches to employability: The added-value of the capability approach. Social Work & Society, 12(2), 1–15.

- Butterworth, P., Leach, L. S., McManus, S., & Stansfeld, S. A. (2013). Common mental disorders, unemployment and psychosocial job quality: Is a poor job better than no job at all? Psychological Medicine, 43(8), 1763–1772. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712002577

- CEDEFOP. (2019). Investing in career guidance: joint statement of OECD, ILO, UNESCO, The European Commission and its agencies ETF and CEDEFOP.

- Dean, H. (2003). Re-conceptualising welfare-to-work for people with multiple problems and needs. Journal of Social Policy, 32(3), 441–459. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279403007062

- Dean, H., Bonvin, J. M., Vielle, P., & Farvaque, N. (2005). Developing capabilities and rights in welfare-to-work policies. European Societies, 7(1), 3–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461669042000327009

- Duffy, R. D., Blustein, D. L., Diemer, M. A., & Autin, K. L. (2016). The Psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(2), 127–148. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000140

- Eden, D., & Aviram, A. (1993). Self-efficacy training to speed reemployment: Helping people to help themselves. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(3), 352–360. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.3.352

- Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005.

- Furman, J. (2020, September 29). Covid 19 and labour markets. Effects and Labour Market Responses, OECD WP 3 Group of Central Bank and Finance Ministry Deputies.

- Goodwin-Smith, I., & Hutchinson, C. (2015). Beyond supply and demand: Addressing the complexities of workforce exclusion in Australia. Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 163–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.36251/josi.97.

- Green, A., de Hoyos, M., Barnes, S., Owen, D., Baldauf, B., Behle, H., … Stewart, J. (2013). Literature review on employability, inclusion and ICT, Report 1. The concept of employability, with a specific focus on young people, older workers and migrants.

- Heyes, J. (2013). Flexicurity in crisis: European labour market policies in a time of austerity. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 19(1), 71–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680112474749

- Hooley, T. (2017). Moving beyond ‘what works’: Using the evidence base in lifelong guidance to inform policy making. In Schroder, K. and Langer, J. (Eds.) Wirksamkeit der Beratung in Bildung, Beruf und Beschäftigung (The Effectiveness of Counselling in Education and Employment) (pp. 25–35). Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann Verlag.

- Hooley, T., Sultana, R. G., & Thomsen, R. (2018). The neoliberal challenge to career guidance. In T. Hooley, R. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism (pp. 1–27). Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jackson, C. (2014). Lifelong guidance policy development: glossary, ELGPN tools, no. 2, European Lifelong Guidance Policy Network, Jyvaskyla. http://www.elgpn.eu/publications/elgpn-tools-no2-glossary.

- Kellard, K., Walker, R., Ashworth, K., Howard, M., & Woon, C. L. (2001). Staying in work: Thinking about a new policy agenda. Research report RR264. Norwich: Department for Education and Employment.

- Laruffa, F. (2020). What is a capability-enhancing social policy? Individual autonomy, democratic citizenship and the insufficiency of the employment-focused paradigm. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 21(1), 1–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2019.1661983

- Lindsay, C. (2010). Re-connecting with ‘what unemployment means’: Employability, the experience of unemployment and priorities for policy in an era of crisis. In I. Greener, C. Holden, & M. Kilkey (Eds.), Social policy Review 22: Analysis and debate in social policy (pp. 121–148). Bristol: Policy Press.

- Lindsay, C. (2014). Work-first versus human capital development in employability programs.

- Lindsay, C., McQuaid, R. W., & Dutton, M. (2007). New approaches to employability in the UK: Combining ‘human capital development’ and ‘work first’ strategies? Journal of Social Policy, 36(4), 539–560. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279407001171

- Martin, J. P. (2015). Activation and active labour market policies in OECD countries: Stylised facts and evidence on their effectiveness. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 4(1), 1–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40173-015-0032-y.

- McGann, M., Murphy, M. P., & Whelan, N. (2020). Workfare redux? Pandemic unemployment, labour activation and the lessons of post-crisis welfare reform in Ireland. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 40(9/10), 963–978. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-07-2020-0343

- McQuaid, R. W., & Lindsay, C. (2005). The concept of employability. Urban Studies, 42(2), 197–219. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000316100

- Mead, L. M. (2003). Welfare caseload change: An alternative approach. Policy Studies Journal, 31(2), 163–185. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-0072.00010

- Murphy, M.P., Whelan, N., McGann, M., & Finn, P. (2020). The ‘high Road’ Back to Work: Developing a Public Employment Eco System for a Post-covid Recovery, Maynooth University Social Sciences Institute, Maynooth.

- OECD. (2004). Career guidance and public policy: Bridging the Gap. Paris: Author.

- OECD. (2020). Public employment services in the frontline for jobseekers, workers and employers. Paris: Author.

- Orton, M. (2011). Flourishing lives: The capabilities approach as a framework for new thinking about employment, work and welfare in the 21st century. Work, Employment and Society, 25(2), 352–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017011403848.

- Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 264–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001.

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2000). Beyond ‘employability’. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 24(6), 729–749. P.123. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/24.6.729

- Redekopp, D., Hopkins, S., & Hiebert, B. (2013). Assessing the impact of career development resources and practitioner support across the employability dimensions. Ottawa: CCDF.

- Savickas, M. (2015). Life-design counseling manual.

- Sharf, R. (2013). Advances in theories of career development. In W. B. Walsh, M. L. Savickas, & P. J. Hartung (Eds.), Handbook of vocational psychology (4th ed., pp. 3–32). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sheehy, K., Kumrai, R., & Woodhead, M. (2011). Young people’s experiences of personal advisors and the Connexions service. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 30(3), 168–182. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/02610151111124923

- Sol, E., & Hoogtanders, Y. (2005). Steering by contract in the Netherlands: New approaches to labour market integration. In E. Sol & M. Westerveld (Eds.), Contractualism in employment services (pp. 139–166). The Hague: Kluwer.

- Sultana, R. G., & Watts, A. G. (2006). Career guidance in public employment services across Europe. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 6(1), 29–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-006-0001-5

- Tomlinson, J., Baird, M., Berg, P., & Cooper, R. (2018). Flexible careers across the life course: Advancing theory, research and practice. Human Relations, 71(1), 4–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717733313.

- Van der Heijden, B. I., & De Vos, A. (2015). Sustainable careers: Introductory chapter. In A. De Vos & B.I.J.M. Van der Heijden (Eds.), Handbook of research on sustainable careers (pp. 1–19). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Värk, A., & Reino, A. (2018). Meaningful solutions for the unemployed or their counsellors? The role of case managers’ conceptions of their work. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(1), 12–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1370692.

- Waddell, G., & Burton, A. K. (2006). Is work good for your health and well-being?. London: The Stationery Office.

- Wanberg, C. R. (2012). The individual experience of unemployment. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(63), 369–396. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100500.

- Warr, P. (1987). Work, unemployment, and mental health. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Wilson, T., Cockett, J., Papoutsaki, D., & Takala, H. (2020). Getting back to work dealing with the labour market impacts of the covid-19 recession, p. 26. Brighton, UK: Institute for Employment Studies. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/547.pdf.