ABSTRACT

Decent work is crucial for an individual’s life development and well-being. The psychology of working theory defines the relationship between micro and macro factors that might be strongly influenced by the context. The aim of this research was to study how people working in the formal and informal economy in Burkina Faso describe their working conditions and the notion of decent work and how economic constraints and marginalisation influence work volition, decent work and work fulfilment using a mixed method approach. A study shows that above and beyond the usual components, social recognition is an especially important aspect of decent work in this context (N = 51). A second study shows that economic constraints and marginalisation factors have an impact on obtaining a decent work, mediated by work volition, both being related to work fulfilment outcomes (N = 501). Results suggest that the objective and subjective components of decent work might refer to two aspects of the same reality.

From its emergence, one important objective of educational and vocational guidance has been to help citizens finding a satisfying social and professional integration and thus to promote their personal and work fulfilment (Claparède, Citation1922; Parsons, Citation1909). This objective was later formalised in the Vocational Guidance Recommendation (No. 87) of the International Labour Office (ILO, Citation1949). This overall aim is still of prime importance and is explicitly mentioned, for example, in the statutes of the International Association for Educational and Vocational Guidance, which state that one aim of “educational and vocational guidance [is] to assist people in making their personal decisions about learning and work […] by helping them to […] integrate successfully in society and the labour market” (art. 2.1). In addition to access to the labour market, the quality of employment is crucial when considering fulfilment and well-being. The importance of benefitting from adequate working conditions for individuals’ development was already mentioned in the United Nations’ (UN) Declaration of Human Rights in Citation1948. Its article 23, al. 1 and 3, states “Everyone has the right to work […] to just and favourable conditions of work […] ensuring […] an existence worthy of human dignity […]” (p. 75). This ambition for social justice was carried further politically by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and was included in the 2030 agenda of the UN (Citation2015).

In this context the Psychology of Working Theory (PWT; Duffy, Blustein, Diemer, & Autin, Citation2016) is interesting because it provides a link between contextual markers of social privilege and marginalisation, personal resources, working conditions, fulfilment and well-being. However, many aspects of this model remain to be investigated. Decent work is usually determined by considering concrete work characteristics, whereas individuals’ perceptions about whether their working conditions are decent or not have been less investigated and may be quite context dependent. Moreover, the context may also impact other components of the PWT. For this reason, the aim of this research was to initially explore in a qualitative study how workers of the formal and informal economy in Burkina Faso would describe their working conditions and define decent work. A second quantitative study was carried to define the links between different aspects of the psychology of working theory, and more precisely the links between contextual markers of social privilege and marginalisation, work volition, decent work, and work fulfilment. Our ambition was to deepen our knowledge about how people perceive their working conditions and decent work and about how decent work, including its antecedents and outcomes, are interrelated.

Decent work across cultures

Decent work is crucial for an individual’s career and life development in terms of meaning and well-being. This concept of decent work was defined by the International Labour Conference in 1999. According to the ILO, decent work includes access to full and productive employment, to rights at work, to social protection, and to participation in a social dialogue (Burchell, Sehnbruch, Piasna, & Agloni, Citation2014). In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development of the United Nations (Citation2015), decent work was made an explicit goal (goal number 8, Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all). Moreover, to promote sustainable careers, education and lifelong learning are key issues that are mentioned in the 4th goal of this agenda. In fact, decent work can be considered a prerequisite for sustainable careers and decent lives (Urbanaviciute, Bühlmann, & Rossier, Citation2019).

In the report of the ILO’s director-general concerning the conference on decent work (ILO, Citation1999), regional specificities were already recognised as a challenge. In particular for Africa, the major problems of the informal economy and of the need for better governance were mentioned. The informal economy includes more than 60% of workers and can have a negative impact on the development of the formal economy (due to unfair competition) and on work conditions (in terms of safety, security, psychosocial factors, and health and social protection). In sub-Saharan Africa, while extreme poverty has decreased during these last 20 years, social protection is still rare and more than 80% of jobs remain informal (ILO, Citation2018). According to the ILO (Citation2015), informal economy concerns all legal “economic activities by workers and economic units that are – in law or in practice – not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements” (p. 4). Moreover, several countries are facing new security issues and political instability. For these reasons, the cultural context has to be considered when studying the antecedents and outcomes of decent work.

The globalisation of the economy and the uncertainty induced by the digitalisation of some industries also constitute threats to the promotion of decent work (Toscanelli, Fedrigo, & Rossier, Citation2019). For this reason, the question of the promotion of decent work for all is a major social justice issue (Reynaud, Citation2018). Educational and vocational guidance can contribute to the promotion of social justice by providing, among other things, support and services to all and in particular to the most vulnerable (Hooley, Sultana, & Thomsen, Citation2018). Nevertheless, the differences in terms of access to resources within and across countries are still very important and much remains to be done to challenge increasing inequalities.

Combining micro and macro factors to describe the access to decent work

The PWT (Duffy et al., Citation2016) describes the link between the antecedents of decent work, decent work, and its outcomes. Economic constraints and marginalisation factors are considered as predictors and defined as markers of privilege or inequalities, such as income, social class, level of education, gender, etc. These constraints predict access to decent work, their link being mediated by personal resources such as work volition or career adaptability. Decent work in turn predict needs fulfilment, which in turn predicts work fulfilment and well-being. Again, needs fulfilment is expected to mediate the impact of decent work on fulfilment and well-being. Several moderators are expected to have an impact on the relation between economic constraints and marginalisation factors and personal resources. These moderators can be personal dispositions or resources, as proactive personality traits or critical consciousness, or contextual constraints or resources, such as social support or economic conditions.

Several studies have recently used and tested aspects of PWT. Masdonati, Schreiber, Marcionetti, and Rossier (Citation2019) studied the link between predictors, decent work and outcomes, and confirmed that work volition partially mediated the relationship between work conditions and decent work and job and life satisfaction in a large sample of Swiss workers. However, they also showed that some marginalisation factors have a direct effect on decent work. McIlveen et al. (Citation2020) and Ribeiro, Teixeira, and Ambiel (Citation2019) studied the impact of decent work on work-related outcomes, job satisfaction, work engagement, work meaning, and turnover intentions, and have shown that decent work has a significant impact in countries as different as Australia and Brazil. Recently, Atitsogbe, Kossi, Pari, and Rossier (Citation2020) have studied the link between some marginalisation factors, decent work, and work-related outcomes, in a sample of Togolese teachers and confirmed that decent work partially mediated this relationship.

Nevertheless, this model raises several questions. The first question concerns the choice of variables. Indeed, the model may be incomplete. Additional contextual constraints, such as structural economic factors, personal resources, such as self-efficacy, or outcomes, such as meaning of life or sustainable career, could also be considered. Moreover, the choice of the moderators may seem a bit restrictive. Finally, the role, in terms of antecedents, moderators, mediators and outcomes, seems somewhat arbitrary. For example, it is surprising that economic constraints do not have a direct impact on decent work. In light of several recent studies, both direct and indirect paths should be considered (e.g. Atitsogbe et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the exact status of decent work in this model could be questioned. Is it really an objective description of working conditions or is it more about personal representations of these conditions (Ferraro, Pais, Santos, & Moreira, Citation2016). The way decent work is defined in the PWT focuses on the individual and its perception and is quite different from a broader framework developed by the ILO (Citation2013) that suggests that 10 aspects have to be considered when assessing decent work (employment opportunities, adequate compensation, adequate working time, work-life balance, stability and security, etc.). Nevertheless, the PWT emphasises the importance of considering simultaneously both macro (e.g. public policies), and micro factors (e.g. personal resources), and their interactions in order to describe access to decent work and its implications in terms of fulfilment and well-being (Urbanaviciute et al., Citation2019).

Background of Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso is located in West Africa south of the Sahara Desert. Its population is estimated at 18,450,495 individuals including 8,696,995 working people as defined by the International Labor Office (INSD, Citation2016a). A former French colony that served as a source of labour for the Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso has been independent since 1960, but its economy remains poorly developed. As a country that is nearly 90% rural and agricultural, the Burkinabè economy is characterised by an informal economic sector, significant productivity of the rural sector and much subsistence agriculture for family consumption (INSD, Citation2016e). Rural agricultural entrepreneurship is often non-existent or very weakly developed, offering little prospect of diversification, valorisation and marketing of national products. This predominance of subsistence agricultural overshadows the low level of industrial production and tertiary activity dominated by the unstructured informal sector (INSD, Citation2016f).

Since 1994, the average economic growth has been estimated at 5%, and the productive system is characterised by a predominance of the tertiary sector which is above 45%. The importance of the primary sector varies between 28 and 31% and that of the secondary sector represents 14% to 24%. In addition, 95% of employed persons have their main activity in the informal sector, with a high proportion in rural areas (99.2%) due to agricultural activities (INSD, Citation2016d).

Workers in the formal sector (public administration, formal private enterprises, NGOs) account for less than 5% of active individuals. Compared to men, the share of women working in the formal sector of public administration is low (32.5%) and in formal private enterprises and NGOs the rate is 24.1%. The majority of working people in the informal sector have no education (88.5%). Usually they have never entered school or have not successfully completed primary school. Moreover, in the informal sector the proportion of employers with no education is 77.2% and those with a higher level represent only 3.3% (INSD, Citation2016b). The entry of the Burkinabe population into the labour market is very early. Indeed, in rural areas 80% of the people aged 15–24 are working while in urban areas 44% are working. Lastly, the gap between men and women is smaller depending on place of residence; it also increases with age then shrinks after age 55 in urban areas (INSD, Citation2016c).

Study 1

Introduction

The way people perceive their working conditions may be quite dependent on the cultural, social, and economical situation. For this reason, the aim of this first study was to analyse how people working in the formal and informal economy in Burkina Faso would describe their working conditions and how they would define decent work.

Method

Participants. Fifty workers were interviewed in the city of Ouagadougou, which is an urban commune structured in zoned and un-zoned housing areas, Burkina Faso (Mage = 29.98, SD = 13.87, range 12–74 years). According to INSD & AFRISTAT (Citation2019), the characteristics of jobs in the informal sector indicate that the proportion of children under 15 employed in the informal sector represents 3.7%. In addition, the jobs held by workers aged 65 are vulnerable (90.6%) and precarious (21.6%). A zoned area is an inhabited or non-inhabited area that has been fragmented by State services, and the un-zoned area is a space that has not been subject to fragmentation recognised by the competent services. Twenty-five participants, 18 men and 7 women, were working in the formal sector, for example as a nurse, security guard, teacher, salesperson, or in a bank. Only 52% had finished compulsory school, but all had had the opportunity to follow some years of school. Twenty-five (14 men and 11 women) were working in the informal sector, as a seller or a security guard, for examples. Of these, only 8% had finished compulsory school and 16% were illiterate. Participants were recruited by the students working with the second authors in the different areas of the city of Ouagadougou.

Interview. The semi-structured interview was conducted in the native language of participants by university students. This interview included questions about work conditions, the level of income, job satisfaction, the positive and negative aspects of their jobs, how they would describe their job conditions, the conditions that do not satisfy them and why, their protection at work, their link with unions, how problems are solved in their workplace, the social recognition of their work, their intention to quit, the notion of decent work, and if their work was decent. Before the interviews, the interview guide was translated from French into the language of the workers (Mooré, Dagara, Dioula, Bisssa, Gourmantché, Gurunsi, Fulfuldé, and Lobiri). All the interviews were recorded with the agreement of the interviewees and then transcribed by the interviewers in the interview language then were translated into French before the thematic content analysis.

Analyses. The qualitative data were collected and analysed collectively by sixteen sociology students from the Joseph Ki-Zerbo University in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) under the supervision of the second author. The qualitative content analysis of each interview has been done by at least two persons including the second author. The data capture using Nvivo 10 has been done by the second author. We used content analysis to identify emerging themes. We have also balanced the quoted verbatim to respect the diversity of the perception of the participants who are workers in the formal and informal sector.

Results

Concerning work conditions participants did describe them according to salary conditions, work satisfaction, and various positive and negative work characteristics. Work is said to be decent if it enables those who exercise it to meet their basic needs and to come and help other members of their community. However, in the informal sector where jobs are not secure and adequately paid, participants’ perceptions emerge that decent work must also uphold the dignity of the worker and have the approval of the social group to which they belong. Five categories emerge from the visions of the participants. Firstly, the participants perceive decent work as an activity which covers basic needs. Secondly, participants consider that decent work must provide social security and protection. Third, participants say that decent work is an activity that must be accepted and tolerated by the worker’s social group of membership (e.g. not to be a sex worker). Fourthly decent work is perceived as an activity that preserves the dignity and honour of the worker (e.g. no cheating, no theft). Finally, a last category of perception mentions that decent work is a blessed activity by God.

Salary conditions. Employees in the formal sector (civil service, business, NGO) receive a fixed annual income, unlike informal sector employees whose income is neither regular nor guaranteed monthly. Thus, the formal sector offers more employment security. The workers declare a monthly income between 15,000 and 300,000XFO (which corresponds to 25 to slightly more than 450 USD). In the informal sector some workers receive a daily income ranging between 200 and 500 XFO depending on the daily profits generated by the activity (which corresponds to daily income ranging from 30 cents to slightly less than 1 USD). Most often, formal public sector workers say they receive a fixed monthly salary close to XOF 300,000 (which corresponds to 450 USD). In the formal sector, the state offers the best jobs because of job security and guaranteed social security benefits.

I am a public sector police officer. My work has no fixed time, my salary can reach 270,000XOF (which corresponds to 405 USD). (Male, 58 years old, Christian, leaving in habited area, unfinished studies, Prison Security Officer, formal sector)

I started doing this, it’s worth eight years like that (laughs). Does the dolo have a profit? Dolo does not have any profit (laughs), dolo does not have any profit in all that, we manage (laughs). Me for example you get up like that come to sell today if you have the chance you can have maybe one day five hundred francs [less than 1 USD] like that, it’s your profit like that and if there is not the market you can sell for example have two hundred and fifty francs like that. (Female, 46 years, Catholic, living in a non-inhabited area, illiterate, working in the informal sector)

For small informal sector activities such as the sale of dolo (traditional beer), traditional women cloth (cotton), motorcycle washing or fruit sales (street vendor), earnings are low and not enough to pay the wages of the workers. Workers in the informal sector are often exploited by their employer. Workers often report that working conditions in Burkina Faso are difficult and precarious. The INSD and AFRISTAT (Citation2019) made the same observation in a study conducted in 2018 which showed that the monthly income from the activity is estimated at 140,000 XOF (which corresponds to 210 USD) for men and 80,200 XOF (which corresponds to 120 USD) for women. Also, excessive working hours (more than 48 h per week) are 55% for men and 45.6% for women. It also appears that the wage rate lower than the minimum wage is 8.6% for men and 27.3% for women.

Work satisfaction. Most informal sector workers are happy to work, and some thank God for allowing them to work. Their satisfaction refers to feeling useful, learning a job and being in touch with others. Feeling healthy at work and having the chance to find a job is also a reason for satisfaction. Compared to those who are in the wrong occupation or unemployed, most formal and informal sector workers are satisfied with their work.

Yes, I am satisfied with my work. Well, in a poor country like Burkina Faso, where the unemployment rate is very high, I think, well, my job is acceptable (Male, 31 years, Muslim, living in an inhabited area, unfinished studies, formal sector)

No, I am very satisfied, as I am in good health, and we do not sleep with hunger, we can eat, I am satisfied. As it is God who gives, if you are in good health and you are not satisfied then you make palaver with God. (Man, 74 years, Muslim, leaving in an inhabited area, illiterate, informal sector)

Having the opportunity and being able to work is perceived as good luck whatever the nature of the work (formal vs informal). However, people perceive accurately their working conditions. People seem to dissociate the fact of being able to work from the conditions in which this work is carried out. So, when work is difficult, precarious, and provides insufficient income, workers in the informal sector express dissatisfaction about their work.

No, I am not satisfied with my work because when I go down at night with 500 francs [less than 1 USD]; it’s not enough for me to eat at night; with 500 francs if I go down and there is no food at home, and I have a little brother and a little sister, the 500 francs will not be enough for us three. (Man, 16 years, Catholic, leaving in an inhabited area, unfinished studies, informal sector)

No, I’m not satisfied with my work because it didn’t allow us to do many things, like buying a motorcycle. I wanted my mom or dad to be able to ride the bike that I would like to buy. (Female, 11 years, Muslim, leaving in habited area, uncompleted studies, private formal sector)

This qualitative study shows that despite the often difficult and painful working conditions, most workers say that they are generally satisfied. They consider themselves lucky to have a job, even a precarious one, in a context where many people cannot find a salaried job. Indeed, considering that in the city of Ouagadougou where the study was carried out, the percentage of unemployed within the meaning of the ILO and of the potential workforce wishing to work as self-employed is estimated at 28.9% for men and 45,4% for women (INSD & AFRISTAT, Citation2019).

Positive and negative work characteristics. Negative aspects of the job are arduousness, psychological pressure, lack of time to devote to one’s family, bad work atmosphere and complaints from clients. High heat and insecurity are other negative aspects of work that are mentioned by workers in the formal and informal sectors.

And then the negative aspects are that as I told you the working conditions are not really pleasant, a lot of pressure at work, there is the climate within the bank that is not pleasant what makes that there are many negative aspects. (Man, 28 years, Muslim, living in an inhabited area, studies completed, formal sector)

The negative point of my job, I walk around to sell and walking around others watching without paying. I walk under the hot sun there and often it does not pay and there is no security on the road Burkina-Ivory Coast. (Woman, 36 years, Muslim, leaving in a non-inhabited area, unfinished studies, informal sector)

As for the positive aspects of work, formal and informal sector workers mention customer satisfaction, having civil servant status, being able to support themselves and making ends meet. The fact of not being unemployed is also mentioned as a positive aspect of the work.

First if we take the positive aspects is that it allowed me to no longer be in the category of unemployed, secondly good it allowed me to have something at the end of the month to at least care primary needs as I had pointed out above to finish on this part good I can say that good is a job also that allows the development of a country as any part of education. (Man, 43 years, Muslim, leaving in a non-inhabited area, unfinished studies, formal sector)

The positive aspects is that by doing this job, I can make ends meet and support myself without asking someone else for help. (Man, 30 years, Muslim, leaving in a non-inhabited area, unfinished studies, informal sector)

Thus, workers most often mention negative aspects of their work, especially in the informal sector. In the informal sector, the precarious employment rate is estimated at 33.2% nationally by INSD and AFRISTAT (Citation2019). Precarious work or employment generally refers to work without guarantees and without a future. Usually, these are informal “small jobs” done by a worker every day to have a little money to meet basic needs. Most often, self-employed and family workers in the informal sector work in vulnerable jobs. Young people aged 15–24 (59.5%) are generally affected by precarious work. As for the positive aspects of work were more frequently mentioned by workers employed in the formal sector, jobs being generally less vulnerable.

Decent work. Decent work is perceived by workers in the formal and informal sector as an activity that enables the individual to meet his or her needs. It is an activity that does not undermine the worker’s morality or soil his honour, does not give him suffering but brings him satisfaction. Decent work is perceived as an activity that takes place without cheating or theft, or having to adopt behaviours that go against social norms. This is a job that must be interesting for the person who exercises it, and everyone must appreciate it and want to exercise it.

Decent work is someone who does his job honestly, without theft, without shady business, that’s what I call decent work. A job that pays you a salary you deserve. (Female, 29 years, Muslim, leaving in an inhabited area, completed studies, informal private sector)

Yes, I’m waiting. Decent work is a work without cheating, interesting and appreciated by others. (Male, 18 years, Muslim, leaving in an inhabited area, unfinished studies, Informal sector)

Well! For me decent work is a job that does not soil your honor, a job that is enough for you. (Female, 32 years, Catholic, leaving in an inhabited area, completed studies, formal sector)

Work is said to be non-decent when it causes dishonour, is painful and does not bring sufficient income to the person who exercises it. So decent work implies in this context dignified work that means that it should be a socially recognised work, situating a person in a social space, and that prevent this person adopting behaviours that go against social norms. So, a formal or informal work can be both decent or indecent according to this social aspect.

Discussion

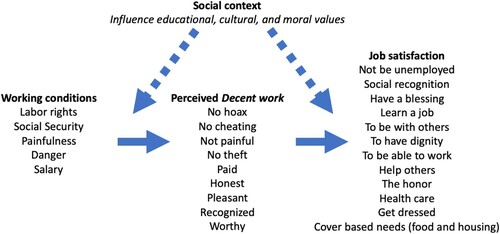

The objectives of the study were to describe how people working in the formal in informal economy in Burkina Faso perceive their work conditions and how they would define a decent work. The informal sector occupies still a preponderant place in the economy of Burkina Faso and is occupied mainly by employers and employees with no formal education. In most cases, workers in this sector are not declared to the social security fund, and the rights and security of jobs are not guaranteed. The working conditions of informal sector workers are generally worse than those of formal workers. It also appears that workers’ visions of decent work do not depend on the sector of activity. Decent work is seen by workers in the formal and informal sector as a fulfilling activity at the personal, family, and social levels (see ). Decent work is a paid activity that enables the individual to meet basic needs, help others, receive blessings and be recognised by their cultural, social and religious group.

Figure 1. Influence of educational, cultural, and moral values, on the visions of decent work in the context of Burkina Faso.

Workers in the formal and informal sectors perceive employment as decent work if certain conditions such as security, social protection, sick leave, health insurance, regular payment of wages and the possibility of unionising and changing activities are respected by the employer. This perception is in line with the definition given by the ILO of a decent work and its’ four pillar that include access to employment, social protection, rights at work, and social dialogue (ILO, Citation2013). However, the perception of decent work by most workers also includes the notion of dignity and social recognition. This aspect can be linked with the needs for social connection that is one outcome of decent work according to the PWT (Duffy et al., Citation2016) not only in terms social support or social relations but also in terms of to be recognised as having a particular social role and situated in a social space (Pouyaud, Citation2016). The social recognition associated with being able of benefitting of decent and meaningful work is certainly an aspect that should be further studied (Urbanaviciute et al., Citation2019). Socially low-status jobs such as gravediggers, garbage collectors and prostitutes are not perceived by workers in the informal sector as decent work. Likewise, when the perceived morality of the job (dishonouring, humiliating, dirtying and corruptible) is incompatible with the values of the worker's home group, the job is often perceived as not-decent work, even if it provides sufficient income. According to these perceptions, decent work must respect the regulatory conditions (labour code) on the one hand, and on the other hand be compatible with the moral and social values of the group of origin of the worker (honour and dignity).

Having a paid job and exercising it in a good working condition contributes to the social integration of individuals, which will contribute to their satisfaction and well-being. Visions of well-being are also influenced by the education of individuals and the cultural, moral and religious values conveyed by the environment in which they live.

Study 2

Introduction

Based on the qualitative study, the first aim of this second study was to adapt the measure of decent work to this specific context including two additional sub-scales, one assessing physical safety at work and a second assessing social recognition. The second aim of Study 2 was to assess the links between economic constraints and marginalisation factors, age, gender, level of education, social class, income, and unemployment history, work volition and decent work as potential mediators – in a sequence as suggested by the PWT –, and job satisfaction and meaning at work.

Method

Participants

The sample included 501 workers from the city of Ouagadougou (Mage = 30.35, SD = 15.24, ranging from 7 to 78 years) with 264 men (52.7%). Thus, some working children or elderly were included in the study. Participants completed a series of questionnaires with the help of students who collected the data. The students recruited the participants among the inhabitants of their neighbourhoods. Of the total, 28.3% were working in the formal sector, 19.6% did not finish school, 22.8% finished compulsory school, 38.2% had a high school degree or completed vocational training, and 15.8% went to some upper education school. Half of participants (49.9%) earn less 50,000 CFA a month (about 85 $). Two-hundred out of 461 (39.9%) reported that they have been unemployed during their careers. Two-hundred and one (described themselves as belonging to a low-income social class, 121 to the lower-middle class, 132 to the middle class, and 36 to upper-middle or the upper class).

Measures

Decent Work Scale (DWS; Duffy et al., Citation2017)

Decent work was assessed using the French version of the DWS (Masdonati et al., Citation2019) that includes 15 items to assess five subscales: safe working conditions, access to health care, adequate compensation, free time and rest, and complementary values. Responses are made on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Internal consistencies reported by Masdonati et al. (Citation2019) for the French-version were .83 for the total score, .78 for safety, .88 for health care, .89 for compensation, .85 for free time and rest, and .90 for values. Considering that physical safety at work and social recognition were very relevant in Burkina Faso, and considering that the safe working conditions sub-scale does more address emotional security than physical safety at work, we added 4 items about physical safety at work and 11 items about social recognition. An analysis of the reliabilities, of items inter-correlations, and of the factorial structure allowed us to select 3 items for physical safety at work and 3 for social recognition (see Appendix 1). Finally, item 9 – I’m rewarded adequately for my work – did not load well on the compensation sub-scale and had to be removed.

Work Volition Scale (WVS; Duffy, Diemer, Perry, Laurenzi, & Torrey, Citation2012)

Work volition was assessed with the 13-item WVS that includes three subscales: volition, financial constraints, and structural constraints. Responses are made on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Internal consistencies of the original English version were .86 for the total score, .78 for volition, .81 for financial constraints, and .70 for structural constraints. Masdonati et al. (Citation2019) reported an internal consistency of .87 for the total score of the French-version.

Job Satisfaction (JS; Judge, Locke, Durham, & Kluger, Citation1998)

Job satisfaction was assessed with French-version of the 5-item JS scale. Responses are made on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Internal consistency of the original English-version was .88. Masdonati et al. (Citation2019) also reported an internal consistency of .88 for the French-version.

Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI; Steger, Dik, & Duffy, Citation2012)

Meaning at work was assessed using the 10-item WAMI that includes three sub-scales about experiencing positive meaning in work (PM), sensing that work is a key avenue for making meaning (MM), and perceiving one’s work to benefit some greater good (GG). Responses are made on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (absolutely untrue) to 5 (absolutely true). Internal consistencies of the original English-version were .93 for the total score, .89 for PM, .82 for MM, and .83 for GG.

Analyses

Confirmatory factor analyses and structural equation modelling were performed using the AMOS statistical package. To achieve model identification, regression coefficients of error terms over the endogenous variables were fixed to 1. To assess the model fit, we used the χ2 per degree of freedom (χ2/df) that should be equal or below 3, the goodness of fit index (GFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), that all should be above .90, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), that should be below .08 for an adequate fit and below .05 for a good fit (Kline, Citation2005).

Internal reliabilities were assessed with Cronbach’s alpha. To study the relations between variables, correlations or bi-serial correlations were computed. To compare workers of the formal and informal sectors, t-tests and ANCOVAs, controlling for age and gender, were computed.

In order to further describe the interrelations between our variables a series of path analyses were computed. In order to assess the significance levels of indirect effects by bootstrapping, AMOS does not allow for missing data. A first path analysis was done after removing all participants with missing values. This left 101 workers from the formal economy and 249 from the informal economy. A second multi-group path analysis was computed with workers of the formal and informal sectors. Again, χ2/df, GFI, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA were reported. For the indirect effects the significant effects were tested by bootsrapping considering a bias-corrected confidence interval of 95%.

Results

Decent work scale in Burkina Faso

A first confirmatory analysis was performed to assess the five-factor structure of the decent work scale. This model did not fit the data well, χ2 (85) = 318.05, p < .001, χ2/df = 3.74, GFI = .905, CFI = .905, TLI = .882, RMSEA = .078, especially because item 9 did not load well on the adequate compensation latent variable, which in turn did not load well on the decent work latent variable. Removing item 9 led to significantly improved model fit, χ2 (72) = 236.50, p < .001, χ2/df = 3.29, GFI = .927, CFI = .930, TLI = .911, RMSEA = .071, Δχ2 (13) = 81.55, p < .001. Considering the importance of safety at work and social recognition, we tested a 7-factor model of decent work that fit the data well after removing item 9, χ2 (163) = 455.47, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.79, GFI = .901, CFI = .918, TLI = .904, RMSEA = .063; only the TLI had a borderline value. For this reason, this 7-factor model was used for the following analyses. The overall reliability of the original version of the decent work scale without item 9 was .75 and with the additional 6 items .76. The reliabilities of the original 5 sub-scales were, respectively, .75, .89, .58, .66, and .86. The reliability of the physical safety at work and social recognition sub-scales were .75 and .88.

Correlations between variables are presented in . Age was positively correlated with social class, salary work, and work and meaning. Correlations with gender (M = 1, W = 2) were generally small. Education, social class and salary were highly correlated, as were work volition, decent work, job satisfaction, and work and meaning. Thus, the social vulnerability factors and the subjective evaluations of people’s resources, work-context, and work outcomes constituted two clusters of correlations. These correlations were never significantly different between the participants working in the formal and informal sectors (ps > .05). Concerning the correlations between the sub-scales of the decent work scale and the other constructs, safe working conditions correlated moderately with job satisfaction (r = .43) and work and meaning (r = .40) but only at .12 with the physical safety sub-scale. The social recognition sub-scale correlated moderately with work and meaning (r = .41). Finally, it is interesting to note that the correlation between the adequate compensation sub-scale and the salary was non-significant.

Table 1. Correlations.

Comparing workers of the formal and informal economy

The participants from the formal and informal sectors differed significantly in terms of education, social class, and salary, all with large effect sizes (see ) even after controlling for age and gender (η2 > .14). Interestingly participants from the informal sector had less frequently encountered a period of inactivity. The differences in subjective evaluations of career resources, work conditions, and work outcomes were much lower and even negligible for decent work and job satisfaction after controlling for age and gender (η2 < .01).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the participants working in the formal and informal sector.

The difference was small for the work volition scale and the volition subscale, t(494) = −2.22, p = .03, d = 0.23 – even negligible after controlling for age and gender (η2 < .01) –, small to medium for the financial constraints, t(494) = −5.02, p < .001, d = 0.50, and non-significant and negligible for structural constraints, t(495) = −1.56, p = .12, d = 0.15.

No difference was observed for the decent work scale between workers of the formal and informal sectors. For the sub-scales, non-significant, negligible differences were observed for access to health care, t(496) = −0.26, p = .79, d = 0.03, adequate compensation, t(492) = −0.39, p = .70, d = 0.04, free time and rest, t(496) = 0.11, p = .92, d = 0.01, and social recognition, t(495) = −0.41, p = .68, d = 0.04. Small and significant differences were observed for safe working conditions, t(496) = 2.40, p = .02, d = 0.24 (negligible after controlling for age and gender, η2 < .01), complementary values, t(495) = −2.87, p = .004, d = .28, and physical safety at work, t(496) = 4.11, p < .001, d = 0.41.

The difference for the meaning at work scale was small. For the subscales, a significant and small difference was observed for positive meaning in work (PM), t(497) = 3.10, p = .002, d = 0.31, and greater good (GG), t(497) = 2.22, p = .03, d = 0.22, but no significant difference for meaning making (MM), t(497) = 1.84, p = .07, d = 0.18. After controlling for age and gender the small difference for the total score remained relevant (η2 = .01) but the differences for the sub-scales were negligible (η2 < .01).

Work volition, decent work, and work fulfilment in Burkina Faso

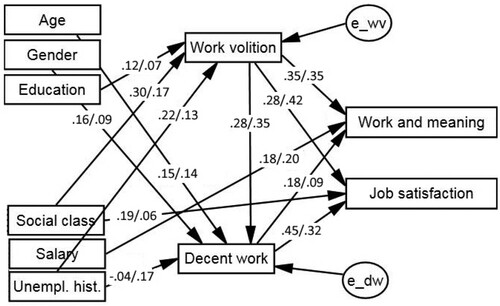

In order to further describe the interrelations between demographic, vulnerability factors, personal resources, decent work, and work fulfilment a path analysis was conducted, χ2 (16) = 16.04, p < .001, χ2/df = 1.00, GFI = .991, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.000, RMSEA = .003. Age and gender were related to decent work, education and social class with work volition, and unemployment history with both work volition and decent work. Social class also had a direct relation with job satisfaction and salary with work and meaning. Decent work seems to mediate part of the relationship between work volition and work fulfilment. Finally, work volition was strongly related with both work and meaning and job satisfaction, whereas decent work was more strongly associated with job satisfaction. All these direct paths were significant. Considering indirect effects, all indirect effects of the path diagram of were significant. The strongest indirect effects were those of gender (β = .11, p = .007) and social class (β = .15, p = .01) on job satisfaction, of unemployment history on work and meaning (β = .15, p = .007) and job satisfaction (β = .29, p = .01), and of work volition on job satisfaction (β = .16, p = .003).

Figure 2. Multigroup path analyses predicting work fulfilment for workers in the formal and informal economy in Burkina Faso. Standardised estimates are displayed for the formal sector first followed by the informal sector. Covariations between antecedents and outcomes and error terms are not reported.

A multi-group path analysis considered workers in the formal and informal sector separately (see ), χ2 (32) = 26.47, p < .001, χ2/df = .827, GFI = .985, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.000, RMSEA < .001. The coefficients were very similar across groups. The links between social class and work volition and job satisfaction, and the link between decent work and job satisfaction were higher for workers of the formal economy. On the other hand, the links between unemployment history and decent work and between work volition and job satisfaction were higher for workers of the informal economy. For the workers of the informal economy, the strongest indirect effects were the effects of social class on work and meaning (β = .12, p = .006) and job satisfaction (β = .12, p = .005), and of work volition on job satisfaction (β = .15, p = .003).

Discussion

Adapting the decent work scale to the context of Burkina Faso meant removing one item associated with a very low loading and which seemed to be difficult to understand. This is logical, as Item 9 (I’m rewarded adequately for my work) belongs to the compensation sub-scale, and refers to non-monetary compensations. In a context where informal work is the most prevalent, the link between non-monetary (social security and benefits) and monetary compensation isn’t obvious. However, in a short scale with only 3 items per sub-scales, removing one item can be problematic, as this leaves two observed variables to assess a latent construct. For this reason, it would have been ideal to have a slightly larger number of items. For future studies, an alternative to Item 9 should be developed for this cultural context.

Based on the qualitative study, two additional sub-scales were developed to assess physical safety at work (the current safety sub-scale assessing more psychological safety) and social recognition. The 7-factor model was validated in both the formal and informal economy sub-samples. In fact, the fit indices were quite similar for the 5- and 7-factor structures. The 7-component structure being more relevant for this cultural context, according to the qualitative study, we proceeded with this version. The importance of social recognition in this context may be associated with the fact that Burkina Faso can be considered a collectivistic culture, where social regulation processes may take the precedence over individual achievements. It also shows that decent work is closely associated with the notion of dignified work. Thus, decent work should provide freedom, equity, stability, security, and dignity (Blustein, Olle, Connors-Kellgren, & Diamonti, Citation2016).

This study also confirms that economic constraints and marginalisation factors have an impact on decent work and that this relation is partially mediated by personal resources. Furthermore, work volition has an impact on job satisfaction and meaning that is partially mediated by decent work. Economic constraints and marginalisation factors were all quite highly correlated on one side with more subjective perceptions, such as work volition, decent work and work fulfilment, on the other side. Mean differences between the formal and informal sectors were high for economic constraints and marginalisation factors and lower for work volition, decent work and work fulfilment. This could suggest that the decent work scale assesses a subjective evaluation of working conditions. On the other hand, working conditions could be seen as part of economic constraints. This subtle link between working conditions and the way in which they are perceived reflects the circular nature of the relation between objective factors and their subjective evaluation. This confirms that the status of decent work in the PWT should be further defined.

General discussion

The cumulative results of these two studies have various implications. First, they illustrate that the context has an impact on the way people perceive their working conditions and how they define decent work. Second, these studies suggest that PWT is relevant but should be further developed, in particular concerning the links between predictors, mediators, and outcomes, and concerning the status of decent work in this model. Finally, our results confirm that there are important differences between the formal and informal sectors, especially concerning economic constraints and marginalisation factors. Interestingly, the differences are much lower for the mediators and outcomes.

In the description of working conditions, salary aspects obviously hold a special place. There are very large disparities in Burkina Faso, especially between the formal and informal economy. Decent work should mean being able to fulfil basic needs, which is not the case for some workers of the informal economy. It is interesting to note that most of the participants are satisfied about being able to work, but regret their working conditions, which are often described as difficult in terms of hours, safety, etc. As expected, workers of the formal economy describe more positive aspects of their jobs compared to the workers in the informal economy. Concerning the definition of decent work, it was described as work that allows a decent life without contravening social norms. Decent work is connected with the notion of social dignity; it should be an honest occupation. This characteristic, as mentioned, might be linked with the more prevalent social norms of a collectivistic culture. It also suggests the ways in which work allows people to be socially situated beyond their achievements. This social component of decent work seems to be especially important in this West-African context. However, while the definition of decent work may vary according to the cultural context, this definition was quite similar for the formal and informal economy sub-samples.

This research also tested several aspects of PWT. First, we described the links between various predictors, decent work as a mediator, and two outcomes. We confirmed that work volition and decent work can be considered mediators, but that mediations were only partial. Moreover, the respective weight of the mediators seemed to depend on the sub-sample. Decent work had a particularly strong impact on job satisfaction for workers in the formal economy, whereas work volition had a particularly strong impact on job satisfaction for workers in the informal economy. It was also interesting to observe that the correlations among economic constraints and marginalisation factors were high, as were correlations between work volition, decent work, and outcomes. However, these two set of variables were quite independent. For example, salary was only moderately correlated with decent work. This suggests that a distinction can be made between objective and subjective descriptors considered by the PWT. This could also lead to possible feed-back loops or recursive processes. For example, work fulfilment could lead to lowering economic constraints. For this reason, we suggest that the PWT could be further developed considering the following aspects:

The PWT should consider simultaneously direct, indirect, and interaction effects, mediation being often partial, and moderation explaining usually only a small part of the variance (e.g. Atitsogbe et al., Citation2020);

Variables can have several functions, for example a marginalisation factor or an economic constraint can be a predictor but also a moderator;

In addition of work volition and career adaptability other personal resources, helping people to manage their career and overcome barriers, as career-decision making skills, career-decision self-efficacy, etc. could be considered (e.g. Rossier, Citation2015);

The PWT should include the development of this configuration of variables over time and in this case the possibility of feed-back loops, the process being possibly recursive;

Finally, the status of decent work in this model could further distinguish between objective and subjective indicators.

This research presents various limitations which are all avenues for future projects. First, the participants were not representative of the general population of Burkina Faso. Indeed, they were recruited in the urban area of Ouagadougou and there are obviously great disparities between urban and rural areas also in this context. These differences have been even accentuated by the prevailing insecurity in northern part of Burkina Faso. For the qualitative part, we overrepresented workers from the formal sector, to have two similar groups of participants. Regarding the quantitative study, not all participants were able to read and answer the questionnaires on their own. In some cases, the students administered the questionnaires orally. This diversity of ways of acquiring the data may also have introduced some bias. As mentioned above, if the issue of decent work is universal, the PWT may need to be adapted to the context of Burkina Faso. A more ambitious study on this topic is underway in various countries of West Africa. Finally, the practical implications are difficult to define precisely. On the one hand, guidance and counselling towards decent work should be generalised, bearing in mind that the educational and vocational guidance services are not yet sufficiently developed. There is also a problem for counsellors to access the populations, in particular for reasons of insecurity in the north. In addition, it is also a more political problem so that the state can support a transformation of the informal sector towards a formal organisation of this economy. To this end, a joint effort by all the social partners is necessary (Carosin, et al., Citationsubmitted).

The differences between workers in the formal and informal economy were very important, especially concerning economic constraints and the marginalisation factors. If the lower differences for the more subjective aspect of the PWT can be seen as the result of an adaptation process, these results also show the urgency for states, including those in Africa, to continue to promote access to decent work for all. This is of course a political and an economic issue, not only for these states but also more collectively (Hooley et al., Citation2018). Thanks to a holistic perspective, vocational psychology can contribute by describing the implications (in terms of opportunities and risks) associated with these social, economic and cultural constraints and marginalisation factors (Blustein et al., Citation2017). This study illustrates, once again, the necessity to continue to promote with conviction and determination public policies to fight inequalities and promote access to decent work for all as a prerequisite for sustainable careers, decent lives, and inclusive societies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jérôme Rossier

Jérôme Rossier, PhD, is full professor of vocational and counselling psychology at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland. He is the editor of the International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance and member of several editorial boards. His teaching and research areas include counselling, personality, and cross-cultural psychology. He has initiated and participated in several multi-national studies in Africa, and co-edited the Handbook of life design: From practice to theory and from theory to practice (Hogrefe, 2015).

Abdoulaye Ouedraogo

Abdoulaye Ouedraogo, PhD, is a sociologist and senior lecturer at the Department of Social Sciences of the University of Joseph Ki-Zerbo, Burkina Faso, and an invited lecturer at the Cheik Anta Diop University, Senegal, and the Sorbonne Development Studies Institute (IEDES) Paris, France. He is a certified practitioner and director of a private counselling centre (CeBi2E). His research focuses on adult education in the African context. He received the South Prize for Innovative Research for the first edition of the UNESCO Chair in Shared Development Challenges: knowing, understanding, acting in 2019.

References

- Atitsogbe, K. A., Kossi, E. Y., Pari, P., & Rossier, J. (2020). Decent work in Sub-saharan Africa: An application of psychology of working theory in a sample of Togolese primary school teachers. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 36–53. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720928255

- Blustein, D. L., Masdonati, J., & Rossier, J. (2017). Psychology and the International Labour Organization: The role of psychology in the decent work agenda. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization. http://www.ilo.org/global/research/publications/WCMS_561013/lang–en/index.htm.

- Blustein, D. L., Olle, C., Connors-Kellgren, A., & Diamonti, A. J. (2016). Decent work: A psychological perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00407

- Burchell, B., Sehnbruch, K., Piasna, A., & Agloni, N. (2014). The quality of employment and decent work: Definitions, methodologies, and ongoing debates. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38(2), 459–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bet067

- Carosin, E., Canzittu, D., Loisy, C., Pouyaud, J., & Rossier, J. (submitted). Developing lifelong guidance prospective by addressing the interplay between humanness, humanity and the world. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance.

- Claparède, E. (1922). Problems and methods of vocational guidance. Studies and Reports. Series J (education) No. 1. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office.

- Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., England, J. W., Blustein, D. L., Autin, K. L., Douglass, R. P., Ferreira, J., & Santos, E. J. R. (2017). The development and initial validation of the decent work scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(2), 206–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000191

- Duffy, R. D., Blustein, D. L., Diemer, M. A., & Autin, K. L. (2016). The psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000140

- Duffy, R. D., Diemer, M. A., Perry, J. C., Laurenzi, C., & Torrey, C. L. (2012). The construction and initial validation of the work volition scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 400–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.04.002

- Ferraro, T., Pais, L., Santos, R. D., & Moreira, M. J. (2016). The decent work questionnaire: Development and validation in two samples of knowledge workers. International Labour Review, 157(2), 243–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12039

- Hooley, T., Sultana, R., & Thomsen, R. (2018). Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism. New York: Routledge.

- ILO. (1949). Vocational guidance recommendation (No. 87). Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:2686429227507::NO::P12100_SHOW_TEXT:Y:.

- ILO. (1999). Decent work: Report of the Director-General. International Labour Conference, 87th Session, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/P/09605/09605(1999-87).pdf.

- ILO. (2013). Decent work indicators: Guidelines for procedures and users of statistical and legal framework indicators (2nd edn.). Geneva. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/.

- ILO. (2015). Recommendation 204 concerning the transition from the informal to the formal economy. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_377774.pdf.

- ILO. (2018). World employment and social outlook: Trends 2018. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/.

- INSD. (2016a). Enquête nationale sur l’emploi et le secteur informel (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Thème 2 Caractéristiques Socio-démographiques [National survey on employment and the informal sector (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Theme 2 Socio-demographic characteristics]. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/enquetes_recensements/ENESI/RapportENESI2015_Phase1_Theme2_Carateristiques_Sociodemographiques.pdf.

- INSD. (2016b). Enquête nationale sur l’emploi et le secteur informel (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Thème 3 Cadre de vie et habitat [National survey on employment and the informal sector (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Theme 3 Living environment and housing]. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/enquetes_recensements/ENESI/RapportENESI2015_Phase1_Theme3_Cadre_de_vie_et_Habitat.pdf.

- INSD. (2016c). Enquête nationale sur l’emploi et le secteur informel (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Thème 4 Insertion sur le marché du travail [National survey on employment and the informal sector (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Theme 4 Integration into the labor market]. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/enquetes_recensements/ENESI/RapportENESI2015_Phase1_Theme4_Insertion_Sur_le_Marche_du_Travail.pdf.

- INSD. (2016d). Enquête nationale sur l’emploi et le secteur informel (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Thème 5 Chômage [National survey on employment and the informal sector (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Theme 5 Unemployment]. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/enquetes_recensements/ENESI/Chomage.pdf.

- INSD. (2016e). Enquête nationale sur l’emploi et le secteur informel (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Thème 6 Conditions de travail et dialogue social [National survey on employment and the informal sector (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Theme 6 Working conditions and social dialogue]. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/enquetes_recensements/ENESI/Conditions_De_Travail_et_Dialogue_Social.pdf.

- INSD. (2016f). Enquête nationale sur l’emploi et le secteur informel (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Thème 7 Trajectoires et perspectives [National survey on employment and the informal sector (ENESI-2015). Phase 1, Theme 7 Trajectories and perspectives]. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/enquetes_recensements/ENESI/Trajectoires_et_Perspectives.pdf.

- INSD & AFRISTAT. (2019). Enquête régionale intégrée sur l’emploi et le secteur informel 2018 [Integrated regional survey on employment and informal sector]. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso and Bamako, Mali: INSD et AFRISTAT. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/enquetes_recensements/ERI-ESI/Burkina%20%20%20%20Faso_ERI-ESI_SyntheseVF.pdf.

- Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., Durham, C. C., & Kluger, A. N. (1998). Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.17

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principle and practice of structural equation modeling (2). NewYork: Guilford Press.

- Masdonati, J., Schreiber, M., Marcionetti, J., & Rossier, J. (2019). Decent work in Switzerland: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110(Part A), 12–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.004

- McIlveen, P., Hoare, P. N., Perera, H. N., Kossen, C., Mason, L., Munday, S., Alchin, C., Creed, A., & McDonald, N. (2020). Decent work’s association with job satisfaction, work engagement, and withdrawal intentions in Australian working adults. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 18–35. Online first publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720922959

- Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Pouyaud, J. (2016). For a psychosocial approach to decent work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00422

- Reynaud, E. (2018). The International Labour Organization and globalization: Fundamental rights, decent work and social justice. ILO research paper no. 21, Geneva, ILO.

- Ribeiro, M. A., Teixeira, M. A. P., & Ambiel, R. A. M. (2019). Decent work in Brazil: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 229–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.03.006

- Rossier, J. (2015). Career adaptability and life designing. In L. Nota, & J. Rossier (Eds.), Handbook of life design: From practice to theory and from theory to practice (pp. 153–167). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436160

- Toscanelli, C., Fedrigo, L., & Rossier, J. (2019). Promoting a decent work context and access to sustainable careers in the framework of the fourth industrial revolution. In I. Potgieter, N. Ferreira, & M. Coetzee (Eds.), Theory, research and dynamics of career wellbeing (pp. 41–58). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28180-9_3

- UN General Assembly. (1948, December 10). Universal declaration of human rights. 217 A (III). http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/217(III).

- UN General Assembly. (2015, October 21). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development, A/RES/70/1. https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html.

- Urbanaviciute, I., Bühlmann, F., & Rossier, J. (2019). Sustainable careers, vulnerability, and well-being: Towards an integrative approach. In J. G. Maree (Ed.), Handbook of innovative career counseling (pp. 53–70). Cham: Springer.

Appendix 1

Additional items considered for assessing decent work in the context of Burkina Faso.