ABSTRACT

Teaching assistants and teachers (N = 186) in Cambridgeshire primary schools in the UK were invited to participate in a survey to explore the perceived impact of school-based counselling (SBC) on pupils’ cognitive, social, and emotional engagement. Participants were also asked which of these factors they believed were most important to a child’s educational progress. T-tests and one-way ANOVAs were conducted to explore the findings. Perceived effects of SBC were greatest on pupils’ social engagement (M = 18.05, SD = 4.17), followed by emotional engagement (M = 16.71, SD = 5.24) and cognitive engagement (M = 15.08, SD = 3.96). Emotional engagement was reported as the most important factor in a child’s educational progress χ2 (2, n = 169) = 77.834, p < .0001.

Introduction

Counselling for secondary school pupils became a statutory obligation in both Wales and Northern Ireland over a decade ago (Welsh Assembly Government, Citation2008; Kernaghan & Stewart, Citation2016). Despite the lack of any statutory duty or dedicated funding to provide similar provision in England and Scotland, figures suggest that in England, between 61% and 85% of secondary schools, and in Scotland, between 64% and 80%, offer counselling to pupils (Hanley et al., Citation2012). However, provision in primary schools is much more sporadic; in Wales, statutory provision was extended to Year Six pupils in 2011 (Hill et al., Citation2011) while approximately 36% of primary schools in England (Place2Be, Citation2016) and 10% in Scotland (Ellison, Citation2017) provide counselling for pupils. At the time of writing, figures relating to the provision of counselling in primary schools in Northern Ireland were not available. Notwithstanding these variations in service provision, SBC is the prevailing therapeutic intervention available to children and adolescents in the UK (Department for Education, Citation2015) and it is associated with a positive change in mental health and emotional wellbeing for both primary and secondary school pupils (Cooper, Citation2009; Cooper et al., Citation2010; Fox & Butler, Citation2009; Lee et al., Citation2009; McArthur et al., Citation2013; Pybis et al., Citation2015).

Why should there be counselling in schools?

A child in the UK will typically spend over 7800 hours at school (Hewlett & Moran, Citation2014) hence school is an apt setting in which to promote emotional wellbeing, and to identify and react promptly when pupils show signs of problems (BACP, Citation2018). In stark contrast to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), for which average waiting times for an initial appointment range between 14 and 200 days (Children’s Commissioner Lightning Review, Citation2016) school-based counselling services (SBCS) are characterised by short waiting times and ease of access (BACP, Citation2018). Timely access to appropriate support is essential not only to ease emotional distress, but also because research has consistently emphasised the importance of early intervention for both emotional and academic outcomes (Allen, Citation2011; Riglin et al., Citation2014). The lack of counselling provision in primary schools across the UK, therefore, suggests that vital opportunities to intervene early are being missed, potentially obstructing children’s educational progress before their academic careers have even begun.

Mental health in children

Mental health conditions amongst school children are well documented; according to an Office for National Statistics report, an estimated 10% of boys and 5% of girls aged between 5 and 10 have a diagnosable mental health disorder (Green, Citation2005). More recently, in the Millennium Cohort Study, which looked at the mental health of children in the UK, Gutman et al. (Citation2015) concluded that 20% of children experience difficulties in their mental health at least once by the time they leave primary school. School-related stress is also a concern; in a study of over 5000 young people, “school stress” was cited amongst the top five contributing factors to mental health problems (Young Minds, Citation2017). Furthermore, over 50% of children at primary school worry “all the time” (Place2Be, Citation2017), and according to 90% of school leaders, mental health problems in school are rising consistently (ASCL and NCB, Citation2016).

Mental health and educational progress

Good mental health is an essential foundation for learning, and being able to “perceive, identify and manage emotion is the basis for being successful” (Cherniss, Citation2000, p. 26). These abilities develop in the early years and affect children’s productivity throughout school (Trzesniewski et al., Citation2006). Children with above-average levels of social, behavioural, and emotional engagement also have above-average academic attainment and are more engaged in school (Gutman & Vorhaus, Citation2012). Furthermore, academic success positively influences children’s views about how satisfied they are with their life and is associated with better wellbeing in adulthood (Chanfrreau et al., Citation2013). Likewise, emotional engagement influences how children behave and engage in school, and arguably, it shapes their ability to develop academic proficiency (Buck et al., Citation2008). Mental health problems are linked with poor school engagement, failure to achieve academic qualifications, and school absence and exclusion (Durlak, Citation2015). Almost half of all children with mental health problems fail to meet their expected level of academic attainment compared to less than a quarter of children without a mental health condition (Parry-Langdon et al., Citation2008). Indeed, the negative effect of emotional distress on progress in school is something that students themselves recognise; according to Ogden’s (Citation2006) review of secondary school counselling in Scotland, 94% of participants reported that their emotional problems hindered their learning. Moreover, it is not just those children who experience emotional difficulties themselves who suffer in the classroom; pupils who display patterns of disruptive behaviour adversely affect both the academic and social environment for their classmates (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, Citation1999).

Impacts of counselling on educational progress

An emerging theme in the research on SBC is that of its impact on educational outcomes (Ryan, Citation2007). Cooper’s (Citation2009) systematic review of secondary SBC in the UK revealed that between 75-90% of teachers noticed improvements pupils’ motivation to attend school, ability to concentrate in class, motivation to study and learn, and willingness to participate in class, as a result of attending SBC. In a review of secondary school counselling in Wales, both pupils and staff reported that SBC enhanced engagement with studying and learning (Cooper et al., Citation2013). Moreover, a meta-analysis of 83 studies of youth counselling found significant self-reports of academically related outcomes, indicating that participants positively appraised counselling’s impact on their academic achievements (Baskin et al., Citation2010).

Rupani et al. (Citation2012) asked secondary school pupils in England how they believed counselling had benefited their studying and learning; the students reported that their concentration, behaviour in class, relationships with teachers, as well as their motivation to study and to attend school had improved due to counselling. The limited amount of research that has been conducted on the impact of educational outcomes in primary schools appears to mirror those impacts noted in secondary school counselling. For example, in a review of primary school counselling in Northern Ireland, Kernaghan and Stewart (Citation2016) proffer that the coping strategies children gain from counselling help them to better regulate their emotions, which releases some cognitive capacity. These findings replicate the results from previous large-scale research which suggest that improvements in educational outcomes are likely to occur as a consequence of improvements in emotional wellbeing and mental health (Cooper, Citation2009; Ogden, Citation2006; Welsh Government, Citation2011). That is, improvements reported in academically related outcomes are indirect because they occur by virtue of improvements in other areas (such as mental health). Moreover, academic improvement would rarely be the primary reason for a school counselling referral; indeed, Hamilton-Roberts (Citation2012) reported that “academic” was noted as a presenting issue in only 5.1% of referrals.

Evidently, SBC has been found to have a positive, indirect impact on a range of educational variables (such as behaviour in class, relationships with teachers, and improved concentration). The individual outcomes reported vary from study to study, but in many ways, they overlap with the constructs of emotion, behaviour, and cognition, and when viewed together, factors such as these could be said to fall under the umbrella of “school engagement”. Exact definitions of school engagement vary, but at a conceptual level, it is strongly associated with academic success (Davis et al., Citation2012). The coalescence of behaviour, emotion, and cognition under the multidimensional umbrella of school engagement is helpful because it unites the constructs in a meaningful way and potentially provides a richer understanding of children’s educational progress than would be possible in an exploration of singular constructs (Fredricks et al., Citation2004).

The interpretation by researchers such as Hamilton-Roberts (Citation2012), Kernaghan and Stewart (Citation2016), Ogden (Citation2006), and Rupani et al. (Citation2012) of the interaction between wellbeing and academic factors certainly corresponds to the notion of there being a dynamic, reciprocally influential relationship between them. The view that learning is both a cognitive and emotional experience is not new, and the association between the two has been explored and well documented by psychologists, therapists, and educational philosophers alike (Bachman et al., Citation1978; Durlak, Citation2015; Lawrence, Citation1973). Furthermore, the interaction between cognitive ability, social skills, behaviour, and emotional wellbeing is reinforced at a theoretical level by the concept of developmental contextualism, and its relevance to work with children and young people (Walsh et al., Citation2002). Developmental contextualism (Lerner & Galambos, Citation1998) is a developmental systems theory that highlights the dynamic, reciprocally influential relationship between children and their environments; thus, factors which influence outcomes in one area are seen also to influence outcomes in other areas (Walsh et al., Citation2002).

To better correspond with the terminology used in previous counselling research, the construct of behavioural engagement in the present study has been reframed as social engagement, although the underlying construct essentially remains the same.

Gaps in current research

Lack of research on counselling in primary schools

Research on SBC has predominantly focused on secondary schools, and this is perhaps a reflection of the sporadic approach to primary school counselling provision. This results in fewer robust research opportunities and as such, gives rise to fewer opportunities to disseminate the beneficial outcomes and raise the profile of primary school counselling. Greater evidence-based literature on the potentially positive impact of counselling on pupils in primary school may lead to an increase in take-up by schools.

Lack of research on the indirect impacts of school-based counselling

Similarly, research on the indirect effects of SBC, such as those on school engagement, and academic attainment, is relatively limited; however, this is an area that is attracting growing interest (Ryan, Citation2007). Indeed, it is a worthwhile research area, as value and efficiency are often deciding factors in securing and increasing funding provision for SBC (Hamilton-Roberts, Citation2012). Crucially, the absence of funding is the most frequently cited barrier to school counselling provision (BACP, Citation2018), and hence this is another research area which might help to rectify the lack of provision in primary schools.

Lack of research on stakeholder perceptions

Perhaps more so than with any other type of organisationally based counselling provision, the success of SBC is reliant upon the input and support of stakeholders, in this case, teaching staff. Indeed, SBC is most beneficial when the principles and values of counselling permeate the whole school (Fox & Butler, Citation2009). Hence, teachers are instrumental not only in ensuring that counselling is successfully embedded into school culture (Loynd et al., Citation2005), but also in helping to deliver the service effectively and efficiently – from making appropriate and timely referrals, attending link meetings, liaising with counsellors, and allowing pupils to attend counselling, to welcoming them back into lessons sensitively, ensuring they do not subsequently fall behind due to missed work, and respecting their confidentiality. Even on a very practical level, SBC relies on school staff to ensure, for example, that the counselling room is accessible, private, secure, safe, and welcoming (Department for Education, Citation2015). Since teachers are the largest body of professionals on whom the success of SBC provision is contingent (Loynd et al., Citation2005), explorative research to understand their perceptions is necessary and is likely to aid the success and survival of provision (Fox & Butler, Citation2009). This is also important because although stakeholder perceptions have generally been found to be good, their support is not a given; in Cooper’s (Citation2009) review, 2–3% of teachers thought that rather than helping, counselling made the situation worse for some pupils. Furthermore, Loynd et al. (Citation2005) reported that some teachers had “strongly negative attitudes” of SBC, and saw it as an “indulgent” or “pointless” activity (p. 203).

Furthermore, while the findings from research conducted in primary schools have tended to mirror those in secondary schools, teacher perceptions are perhaps one area in which caution should be exercised when making generalisations. By way of example, the level of input required from teaching staff to facilitate a successful school counselling service is likely to differ between the primary and the secondary setting. For instance, the amount of effort required by a primary school teacher to ensure a pupil does not fall behind from regularly missing an hour of a lesson is likely to be different to that required from a secondary school teacher. Similarly, ensuring a pupil settles back into the classroom appropriately following a counselling session might require a greater level of input from a teacher in a primary school than from a teacher in a secondary school.

The current study

In summary, research exploring the indirect impacts of counselling and the perceptions of stakeholders is necessary and is likely to aid the success and survival of counselling provision in schools. This is especially pertinent in the case of primary school counselling, which is under-represented in research, funding, and subsequently, in provision.

To address the gaps identified in the literature on SBC, research question one (RQ1) explores the perceptions of primary school teaching staff on the indirect effects of counselling; specifically, do staff report any noticeable improvements in overall school engagement, as represented by the cognitive, social, or emotional engagement of pupils who attend counselling? In an attempt to quantify the perceived effects of SBC, research question two (RQ2) explores which factor (cognitive engagement, social engagement, or emotional engagement) teaching staff believe is the most important factor in a child’s educational progress.

Methods

Participants

Teaching assistants (TA) and teachers (collectively “teaching staff”) in primary schools across Cambridgeshire, UK, were invited by email to take part (anonymously) in a survey about their experiences of SBC. A total of 186 participants completed the questionnaire. Only data drawn from respondents with direct experience of SBC (n = 62) have been included in the analysis of RQ1. The analysis of RQ2 includes the complete data set (N = 186). Not all questions were answered, so totals may not always add up to 100%, n = 62, or N = 186.

Materials

The survey was piloted with 10 primary school teachers, who were also asked to give feedback on the questions – no substantial changes were suggested. The questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first part asked respondents five single-answer multiple-choice questions to gather data on factors such as job role, number of years teaching, and amount of experience with SBC (the independent variables). The second part included a further 21 questions, 20 of which were answered with a 5-point Likert-scale (1 = “strongly agree” to 5= “strongly disagree”). These questions were intended to investigate whether respondents perceived any effects of SBC in three areas, namely, cognitive engagement (six items), social engagement (seven items), and emotional engagement (seven items), which when combined, can be said to represent school engagement (Fredricks et al., Citation2004). The items included in the Likert scale were based on questions used in previous studies on SBC (Cooper, Citation2006; Hamilton-Roberts, Citation2012; Rupani et al., Citation2012).

All three dimensions evidenced strong reliability and validity. Internal consistency reliability estimates using Cronbach’s Alpha were .89, .88 and .91, respectively. An exploratory factor analysis was also conducted on the 20 Likert scale questions using principal component analysis with Varimax (orthogonal) rotation. The analysis yielded three factors, which represent the three engagement constructs being investigated, and explain a total of 84% of the variance in the data. This result provides further evidence that the items in each of the three dimensions represent the underlying constructs of cognitive engagement, social engagement, and emotional engagement. A fourth factor, which included high loadings (≥.6) for three items (motivation to attend school, ability to get along with adults in school, and ability to accept responsibility for behaviour), could be said to represent maturity.

The final questionnaire item was a single-answer multiple choice question which asked participants to choose one of the three factors (cognitive engagement, social engagement, or emotional engagement) they believed to be the most important to a child’s educational progress.

Procedure

The questionnaire was self-administered online through the Qualtrics online survey platform. Responses were collected over a period of six weeks. To reduce social desirability bias, which has been identified as a potential issue in previous surveys on SBC (Cooper, Citation2009; Hamilton-Roberts, Citation2012), all respondents were anonymous, and no personal or identifying information was collected. A routing plan (which included filter questions and skip logic) was designed to ensure the survey was coherent from each respondent’s point of view, to reduce response fatigue, and to maximise the accuracy of the data collected. The order of both the questions and the response options was randomised (where possible and appropriate) to minimise the question-order effect. All procedures in this study received ethical approval from the University of East London’s Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

The data set was analysed in SPSS. Each respondent’s Likert scale data were converted (from 1–5 to 0–4) and summed to create summated scales suitable for parametric tests. T-tests and one-way ANOVAs were conducted to explore differences between the mean scores.

Results

Participants

As shows, most of the participants (n = 132, 71%) were teachers; nearly all respondents (n = 168, 90%) had four or more years’ teaching experience, a third of participants had an experience of SBC (n = 62, 33%), and of those with experience of counselling, approximately half (51% n = 30) had a “moderate” or “extensive” amount of experience of SBC.

Table 1. Participant characteristics (N = 186).

RQ1: Descriptive analysis

Summated data from the Likert scale questions indicated that respondents perceived the greatest effects of SBC to be on pupils’ social engagement (M = 18.05, SD = 4.17), followed by their emotional engagement (M = 16.71, SD = 5.24) and then their cognitive engagement (M = 15.08, SD = 3.96).

A summary of the aggregated agreement and disagreement responses is presented in . This table highlights that over half of the participants somewhat agreed or strongly agreed that SBC had a positive effect in all three educational dimensions. Again, the most notable effects were perceived to be on children’s social engagement (n = 100, 59%), although the results are similar for each factor.

Table 2. Aggregated responses from the three educational factors.

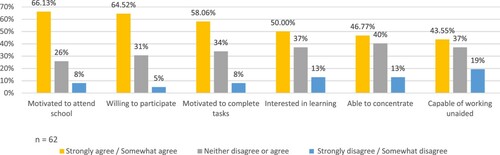

Perceived effect of school-based counselling on cognitive engagement

presents a summary of the aggregated responses within the construct of cognitive engagement. This figure highlights that within this construct, the largest effects of counselling were perceived in motivation to attend school (n = 41, 66%), willingness to participate (n = 40, 64%), and motivation to complete tasks (n = 36, 58%). Concentration (n = 29, 47%) and capacity to work unaided (n = 27, 44%) were perceived to be the least affected by counselling.

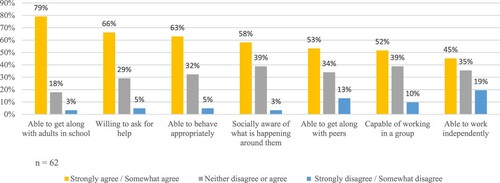

Perceived effect of school-based counselling on social engagement

presents a summary of aggregated responses within the social engagement dimension. There was more overall agreement amongst participants that SBC has an impact on social engagement than in either of the other dimensions (more than 50% of respondents somewhat agreed or strongly agreed that counselling had a positive effect on six out of the seven social engagement items).

Aggregated agreement scores were also the highest in this dimension. Over three-quarters of respondents (n = 49, 79%) perceived a positive effect of counselling on pupils’ ability to get along with adults in school, which is the highest scoring item in all three dimensions.

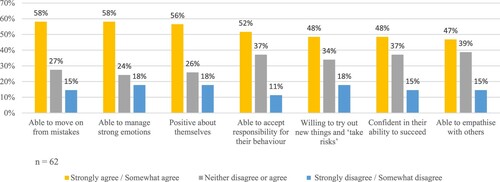

Perceived effect of school-based counselling on emotional engagement

presents a summary of aggregated responses within the dimension of emotional engagement. This figure demonstrates that overall agreement amongst participants is lowest in this dimension (more than 50% of respondents somewhat agreed or strongly agreed that counselling had a positive effect on only four out of the seven items).

also show that most participants (n ≥ 30, 50%) noticed a positive impact of counselling in 14 (70%) out of the 20 variables presented.

Advanced statistical analysis

show the results of analyses examining the effect of the various independent variables on the perceived effectiveness of counselling on pupils’ cognitive, social, and emotional engagement. Independent t-tests and one-way ANOVAs were employed to investigate whether differences between mean scores were significant. show that independent t-tests found no significant relationship between perceived counselling effectiveness and job role, years of teaching experience, whether counselling was provided in-house or through an external agency, or recency of counselling experience.

Table 3. Whether perceived counselling effectiveness differed by job role.

Table 4. Whether perceived counselling effectiveness differed by number of years of teaching.

Table 5. Whether perceived counselling effectiveness differed by how counselling was provided.

Table 6. Whether perceived counselling effectiveness differed by amount of experience with SBC.

Table 7. Whether perceived counselling effectiveness differed by recency of experience with SBC.

However, shows that one-way ANOVAs comparing the perception of counselling effectiveness by the amount of experience teaching staff have of SBC found significant differences across the three constructs: cognitive engagement, F (2, 56) = 5.876, p = .005; social engagement, F (2, 56) = 10.182, p = .000; and emotional engagement, F (2, 56) = 10.704, p = .000. Thus, the amount of experience participants had of SBC was the only independent variable which made a difference to how they perceived the effectiveness of counselling, that is, participants with more experience of counselling were more likely to report a positive impact of counselling.

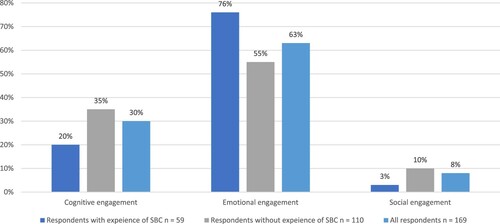

RQ2: Descriptive analysis

A summary of the responses to the question of which factor is most important to educational progress is presented in . This figure indicates that over half (63% n = 106) of the participants selected emotional engagement as the most important factor, suggesting that teaching staff view emotional health as important to learning and educational progression. The independent variables had no effect on responses to RQ2.

RQ2: Advanced statistical analysis

A chi-square goodness-of-fit test was performed to determine whether the differences shown in were significant. The three factors presented to participants, namely, cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, and social engagement, were not reported equally χ2 (2, n = 169) = 77.834, p < .000. These results show that a significantly higher proportion of participants perceived emotional engagement to be the most important factor in a child’s educational progress, and this pattern of responses is evident whether respondents have experience of SBC χ2 (2, n = 59) = 51.492, p < .000., or do not have experience of SBC χ2 (2, n = 110) = 34.164, p < .000.

Discussion

The results of the present study present a largely positive view of the impact of SBC on a range of educational variables, as perceived by primary school teaching staff. These results could be taken as evidence of a perceived impact of counselling on overall school engagement. However, as with all data concerning perceptions rather than objective outcome measures, it is worth noting that these results do not provide evidence of an actual impact of counselling on school engagement.

The results of the current study indicate that positive changes occur in pupils’ social, emotional, and cognitive engagement following SBC, and these impacts are noticeable to teaching staff. This concurs with the findings from previous research, conducted predominantly in secondary schools, in which both client self-reports (Cooper, Citation2006; Cooper, Citation2009; Kernaghan & Stewart, Citation2016; Rupani et al., Citation2012) and those of teaching staff (Cooper, Citation2009; Hamilton-Roberts, Citation2012; Hill et al., Citation2011; Loynd et al., Citation2005; McKenzie et al., Citation2011; Pybis et al., Citation2015) have indicated either a positive impact or a perceived positive impact of counselling on educational outcomes. It also supports the research by Lee et al. (Citation2009), which found evidence of a perceived impact of counselling on social and emotional factors. Overall, these findings are also consistent with Cooper and McLeod’s (Citation2007) thoughts on the pluralistic nature of counselling impacts.

Concept of school engagement

The similarity between the results in the individual categories, namely, social engagement (M = 18.05, SD = 4.17), emotional engagement (M = 16.71, SD = 5.24), and cognitive engagement (M = 15.08, SD = 3.96), provides evidence for the notion of an overarching dynamic and multidimensional, construct of school engagement (Fredricks et al., Citation2004), which comprises these three categories of variables. Hamilton-Roberts (Citation2012) study on teacher and parent perceptions of counselling also found evidence of three educational constructs: engagement with education and learning, mental health and emotional wellbeing, and behavioural presentation. It could be argued that these constructs overlap with this study’s constructs of cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, and social engagement, and therefore further support the idea of school engagement (as a multidimensional construct). In contrast to the results of the present study, which suggest that the greatest perceived impact of counselling was in social engagement, Hamilton-Roberts reported the most considerable perceived impact of counselling was in the construct of mental health and emotional wellbeing. The disparity in the findings implies that more research is needed to create a robust, universal definition of school engagement comprising a universally agreed set of variables.

Social engagement

In contrast to previous studies on the impact of SBC (Cooper, Citation2006; Hamilton-Roberts, Citation2012; Lee et al., Citation2009), which have shown the largest of effects to be on emotional wellbeing, the current study suggests that teaching staff perceived a marginally larger impact on pupils’ social engagement, although the responses in all three categories were similar. This could perhaps be explained by the fact that in the current study, direct questions pertaining to social engagement were posed to participants.

Within the seven variables in the category of social engagement, teaching staff perceived an impact of counselling on pupils’ ability to get along with adults, behave appropriately, and work independently, which concurs with previous research (Baskin et al., Citation2010; Ogden, Citation2006; Rupani et al., Citation2012). There was only one variable within this category, namely, ability to work independently, in which less than half (n = 28, 45%) of the respondents agreed that there had been a positive impact. This contrasts with Ogden (Citation2006), who found evidence that participants were more able to work independently following an SBC intervention. However, the participants in Ogden’s study were secondary school pupils, whose ability to work independently was perhaps greater in the first place, which may explain the disparity in the findings.

Cognitive engagement

Previous studies which focused specifically on the impact of counselling on pupils’ educational outcomes (Ogden, Citation2006; Rupani et al., Citation2012) have indicated that the biggest impacts were on pupils’ ability to concentrate, closely followed by their participation in class, and their confidence in their ability with schoolwork. Indeed, numerous studies have suggested that improvements in educational outcomes, associated with SBC, occur by virtue of improved concentration (Cooper, Citation2009; Rupani et al., Citation2012). However, the current study found far less evidence of a perceived improvement in concentration: 47% of participants (n = 29) somewhat agreed or strongly agreed that SBC had positively affected pupils’ ability to concentrate, compared to between 60—70% in Cooper (Citation2009) and 95% in Rupani et al. (Citation2012). There are a few potential explanations for this variance: both Ogden (Citation2006) and Rupani et al. (Citation2012) interviewed clients directly, which is arguably the most accurate way to obtain information about concentration, given that concentration itself is not easy to observe in others. This is perhaps also evidenced by the relatively high number of participants (n = 25, 40%) who said they could neither agree nor disagree on whether counselling had affected concentration. Likewise, participants in the Rupani et al. (Citation2012) and Ogden (Citation2006) studies were secondary school pupils; irrespective of how data pertaining to concentration are gathered or measured, it is reasonable to anticipate that both levels of and influences on concentration will differ significantly between primary and secondary school age-groups, thus limiting the generalisability of the findings. Evidence of a perceived impact of SBC on pupils’ motivation to attend school, willingness to participate, and motivation to complete tasks in this category concurs with previous research (Cooper, Citation2009; Ogden, Citation2006; Rupani et al., Citation2012).

Emotional engagement

School-based counselling was perceived to have a positive impact on emotional engagement, which concurs with most of the research (Cooper, Citation2006; Cooper, Citation2009; Hamilton-Roberts, Citation2012) on SBC. Due to the concurrence of emotional wellbeing as the most significant area of impact in counselling, the fact that participants scored the impacts of counselling in the social engagement category slightly higher than they scored emotional engagement was surprising. Perhaps most surprising, however, is the fact that lowest-scoring variables in this category, namely, willingness to try out new things (n = 30, 48%), confidence in ability to succeed (n = 30, 48%), and ability to empathise with others (n = 29, 47%) were all found to have been significantly affected by counselling in previous research (Ogden, Citation2006; Rupani et al., Citation2012). The participants in previous studies were secondary school pupils, which could help to explain some of this disparity. Furthermore, both Ogden (Citation2006) and Rupani et al. (Citation2012) asked clients directly about the impact of counselling on their emotional wellbeing. In contrast, the current study relied upon participant observations – observing a change in another person’s ability to empathise, or in how well they can move on from mistakes is difficult, especially in a busy classroom environment, and as such, investigations of emotional change are perhaps better suited to direct questioning and self-reports. That said, Lee et al. (Citation2009) found that teachers and parents perceived improvements in children’s emotional and social behaviour, as a result of SBC; parent scores were marginally higher, which suggests that parents, as might be expected, are more able to recognise subtle but significant changes that would perhaps go unnoticed in the classroom.

Amount of experience teaching staff have of school-based counselling

The amount of experience participants had of school-based counselling influenced how they perceived its effectiveness, that is, participants experienced with SBC were more likely to report positive impacts. This concurs with Cooper (Citation2004), who found that teachers who referred a greater number of pupils for counselling rated the helpfulness of the service significantly higher than those teachers who referred fewer pupils. This suggests that the more experience school staff have of school-based counselling, the more they value it. This has implications for how SBCS are integrated into schools and how short-term projects and pilot schemes are evaluated.

Emotional engagement as most important

The results provide strong support for the hypothesis that emotional engagement is the leading of the three factors in educational progress . Given the efficacy of SBC in alleviating children’s psychological distress and improving emotional wellbeing (Cooper, Citation2009; Lee et al., Citation2009), this strongly suggests that SBC could potentially play a vital role in improving educational outcomes.

The degree to which emotional engagement was favoured by participants as the leading factor in educational progress was surprising, particularly as it was presented alongside cognitive engagement, which you might expect teaching staff to favour. Social desirability has been found to affect studies on SBC previously (Cooper, Citation2006); hence, it is worth considering that there could be some level of bias in the responses. For example, participants may have been keen to highlight their consideration of emotional factors in learning, knowing that they were taking part in research on counselling.

Limitations of the current study

Small sample size

The small sample size (N = 186), of which only 33% (n = 62) had any experience of SBC, and of those, approximately half (51% n = 30) had a “moderate” or “extensive” amount of experience of it, potentially limits the generalisability of the results. Given that the amount of experience teaching staff has of SBC was found to influence how they perceive its impact, the mixed levels of experience amongst participants in the current study might also have influenced the results.

Lack of data collected

To ensure the brevity and clarity of the questionnaire, the survey did not collect information regarding issues such as the theoretical orientation of the counselling offered, the number of sessions the pupils in question received, their age and gender, the reason for their referral, the severity of their difficulties, or their baseline level of school engagement. Hence, it is difficult to know what, if any, impact these variables had on the results. Furthermore, the survey questions were phrased in such a way as to ask participants to make very broad generalisations, for example, “To what extent do you agree with the following statement? “As a result of their counselling, most children are more … able to concentrate”. The reason for this phrasing was to maximise the responses from a participant base likely to have a very broad, differing range of experiences and examples on which to draw from. However, inevitably, this necessitates generalising or summarising individual experiences, which could be difficult. For example, how can participants generalise their overall answer if their experience consists of two pupils who have attended counselling, one of whom demonstrated a significant amount of positive change and another, who demonstrated the opposite? This could explain the relatively high and consistent level of “neither agree nor disagree” answers provided (emotional engagement 32%, cognitive engagement 34%, social engagement 32%).

Appropriateness of questions

The questionnaire was based on those used in previous studies; however, these have largely focused on secondary schools, and this raises doubts about the appropriateness of some of the questions posed in relation to the primary school age group, such as ability to work independently, and ability to concentrate, especially given the contrasting findings. Age and developmental stage are likely to influence many of the educational variables in question, thereby making comparisons across such a wide age range potentially problematic.

Implications

Implications for practitioners

The results provide evidence for the pluralistic, multidimensional nature of counselling impacts, and for the existence of school engagement as a meta-theory; school-based practitioners should, therefore, be encouraged to include a broad range of outcome measures, covering emotional, social, and cognitive factors – to inform their practice and to share with their colleagues in school.

The finding that the more experience teaching staff have of counselling, the greater they perceive the impacts to be, has implications for how counselling provision is integrated within schools. This study, therefore, acts as a call to school-based counsellors and school counselling organisations alike, to work more closely with their counterparts and colleagues in education to ensure the full benefits of SBC are realised, evaluated, and shared. Moreover, disseminating outcome results which highlight the multidimensional impacts of counselling, such as those on school engagement, as well as those on mental health, is likely to help foster a better understanding between teachers and counsellors, whilst also promoting the “value for money” nature of SBC.

Implications for future research

Evidently, the results of the current study contradict a number of previous research findings found in secondary school studies, such as those pertaining to concentration. This raises doubts over the generalisability of the results and strengthens the call for a research focus specifically dedicated to counselling in primary schools.

Cooper (Citation2006) called for more research into how counselling might affect educational outcomes; the findings herein suggest that if we are to understand how SBC affects educational variables, it is the meta construct of school-engagement rather than the individual academic variables (such as concentration) or academic achievement per se that is worthy of further investigation. The current study found evidence of a grouping of variables that correspond with the idea of school engagement, but research is needed to explore and refine the concept to create a universally understood construct that stands up to robust research methods.

Wider implications

Emotional wellbeing is the leading factor in educational progress, according to primary school teaching staff. This finding, combined with the recognised decline in children’s mental health, and the efficacy of SBC in alleviating psychological distress and improving emotional wellbeing, provides a further call for the universal provision of SBC in primary and secondary schools across the UK.

Conclusion

Overall, the perceived impact of SBC was positive. Pupils who attended counselling were perceived by teaching staff to show noticeable improvements in school engagement, as demonstrated by changes in their social, emotional and cognitive engagement. When appraising the perceived impacts of SBC, such as those on school engagement, it is important to keep in mind that these are indirect impacts, which occurover and above the already well-evidenced, direct impacts on mental health and emotional wellbeing. Hence the indirect impacts of SBC are a worthwhile area of research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Helen Raynham

Helen Raynham is a school-based counsellor, and a PhD student at the University of Roehampton, UK. This article forms part of a dissertation submission for a Master of Arts Degree in Counselling and Psychotherapy from the University of East London, UK.

Gordon Jinks

Gordon Jinks is Head of Programme for the PGDip and MA Counselling & Psychotherapy at the University of East London, UK.

References

- Allen, G. (2011). Early intervention: Smart investment, massive savings, the second independent report to Her Majesty’s government. The Stationery Office.

- Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL) and National children’s bureau (NCB). (2016). Survey briefing. Keeping young people in mind – findings from a survey of schools across England. Retrieved 10 January 2017. https://www.ascl.org.uk/news-and-views/news_news-detail.school-leaders-voice-concerns-over-children-s-mental-health-care.html

- Bachman, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, J. (1978). Adolescence to adulthood-change and stability in the lives of young men.

- Baskin, T. W., Slaten, C. D., Crosby, N. R., Pufahl, T., Schneller, C. L., & Ladell, M. (2010). Efficacy of counseling and psychotherapy in schools: A meta-analytic review of treatment outcome studies 1Ψ7. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(7), 878–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010369497

- British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP). (2018). BACP’s response to the CQC’s report on children and young people’s mental health. Retrieved: 10 March 2017. https://www.bacp.co.uk/news/2018/8-march-2018-cqc-response/

- Buck, S. M., Hillman, C. H., & Castelli, D. M. (2008). The relation of aerobic fitness to stroop task performance in preadolescent children. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 40(1), 166–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e318159b035

- Chanfrreau, J., Lloyd, C., Byron, C., Roberts, R., Craig, D., De Foe, D., & McManus, S. (2013). Predicting wellbeing. Prepared by NatCen Social Research for the Department of Health. Retrieved 10 November 2017. www.natcen.ac.uk/media/205352/predictors-of-wellbeing.pdf

- Cherniss, C. (2000). Emotional intelligence: What it is and why it matters (p. 15). Rutgers University, Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology.

- Children’s Commissioner. (2016). Lightning review: Access to child and adolescent mental health services. Retrieved 1 November 2017. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/publication/lightning-review-access-to-child-and-adolescent-mental-health-services/

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1999). Initial impact of the fast-track prevention trial for conduct problems: I. The high-risk sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(5), 631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.67.5.631

- Cooper, M. (2004). Counselling in schools project: Evaluation report. Glasgow: Counselling Unit, University of Strathclyde. Retrieved 1 November 2017. http://www.strath.ac.uk/Departments/counsunit/research/cis.html

- Cooper, M. (2006). Scottish secondary school students’ preferences for location, format of counselling and sex of counsellor. School Psychology International, 27(5), 627–638. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306073421

- Cooper, M. (2009). Counselling in UK secondary schools: A comprehensive review of audit and evaluation data. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 9(3), 137–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140903079258

- Cooper, M., & McLeod, J. (2007). Psychotherapy: Implications for research. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 7(3), 135–143. ISSN 1473-3145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140701566282

- Cooper, M., Rowland, N., McArthur, K., Pattison, S., Cromarty, K., & Richards, K. (2010). Randomised controlled trial of school-based humanistic counselling for emotional distress in young people: Feasibility study and preliminary indications of efficacy. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-4-12

- Cooper, M., Stewart, D., Sparks, J., & Bunting, L. (2013). School-based counseling using systematic feedback: A cohort study evaluating outcomes and predictors of change. Psychotherapy Research, 23(4), 474–488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.735777

- Davis, H. A., Summers, J. J., & Miller, L. M. (2012). An interpersonal approach to classroom management: Strategies for improving student engagement. Corwin Press.

- Department for Education. (2015). Counselling in schools: A blueprint for the future. Retrieved: 20 May 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_ data/file/416326/Counselling_in_schools_-240315.pdf

- Durlak, J. A. (2015). Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice. Guilford Publications.

- Ellison, M. (2017). School counselling support “patchy”. BBC Scotland, 28 August 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-40959463

- Fox, C. L., & Butler, I. (2009). Evaluating the effectiveness of a school-based counselling service in the UK. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 37(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880902728598

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

- Green, H. (2005). Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004, p. 2005. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gutman, L. M., Joshi, H., Parsonage, M., & Schoon, I. (2015). Children of the new century: Mental health findings from the millennium cohort study. Centre for mental health report. Centre for Mental Health.

- Gutman, L. M., & Vorhaus, J. (2012). The impact of pupil behaviour and wellbeing on educational outcomes. Retrieved 1 November 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/219638/DFE-RR253.pdf

- Hamilton-Roberts, A. (2012). Teacher and counsellor perceptions of a school-based counselling service in South Wales. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40(5), 465–483. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.718737

- Hanley, T., Humphrey, N., & Lennie, C. (2012). Adolescent counselling psychology: Theory, research and practice. Routledge.

- Hewlett, E., & Moran, V. (2014). Making mental health count: The social and economic costs of neglecting mental health care, OECD Health Policy Studies. OECD.

- Hill, A., Cooper, M., Pybis, J., Cromarty, K., Pattison, S., & Spong, S. (2011). Evaluation of the Welsh School-based counselling strategy. Welsh Government Social Research.

- Kernaghan, D., & Stewart, D. (2016). “Because you have talked about your feelings, you don’t have to think about them in school”: Experiences of school-based counselling for primary school pupils in Northern Ireland. Child Care in Practice, 22(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2015.1118015

- Lawrence, D. (1973). Improving reading through counselling. Ward Lock.

- Lee, R. C., Tiley, C. E., & White, J. E. (2009). The Place2Be: Measuring the effectiveness of a primary school-based therapeutic intervention in England and Scotland. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 9(3), 151–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140903031432

- Lerner, R. M., & Galambos, N. L. (1998). Adolescent development: Challenges and opportunities for research, programs, and policies. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 413–446. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.413

- Loynd, C., Cooper, M., & Hough, M. (2005). Scottish secondary school teachers’ attitudes towards, and conceptualisations of, counselling. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 33(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880500132722

- McArthur, K., Cooper, M., & Berdondini, L. (2013). School-based humanistic counseling for psychological distress in young people: Pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 23(3), 355–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.726750

- McKenzie, K., Murray, G. C., Prior, S., & Stark, L. (2011). An evaluation of a school counselling service with direct links to child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) services. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 39(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2010.531384

- Ogden, N. (2006). Interviews with clients regarding the impact of counselling on their studying and learning. In M. Cooper (Ed.), Counselling in schools project, Phase II: Evaluation report. Counselling Unit, University of Strathclyde. Retrieved 1 November 2017. http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/26793

- Parry-Langdon, N., Clements, A., Fletcher, D., & Goodman, R. (2008). Three years on: Survey of the development and emotional well-being of children and young people. Newport, UK: Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 1 November 2017. https://lx.iriss.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/child_development_mental_health.pdf

- Place2Be. (2016). Children’s mental health matters – Provision of primary school counselling [online]. Retrieved 10 January 2016. https://webcontent.ssatuk.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/02101242/Childrens-Mental-Health-in-Primary-Schools-Places2Be.pdf

- Place2Be. (2017). Children’s mental health week. [online]. Retrieved 1 May 2017. https://www.childrensmentalhealthweek.org.uk/news/look-back-at-children-s-mental-health-week-2017/

- Pybis, J., Cooper, M., Hill, A., Cromarty, K., Levesley, R., Murdoch, J., & Turner, N. (2015). Pilot randomised controlled trial of school-based humanistic counselling for psychological distress in young people: Outcomes and methodological reflections. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 15(4), 241–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2014.905614

- Riglin, L., Petrides, K. V., Frederickson, N., & Rice, F. (2014). The relationship between emotional problems and subsequent school attainment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 37(4), 335–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.010

- Rupani, P., Haughey, N., & Cooper, M. (2012). The impact of school-based counselling on young people’s capacity to study and learn. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40(5), 499–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.718733

- Ryan, J. A. (2007). Raising achievement with adolescents in secondary education – the school counsellor’s perspective. British Educational Research Journal, 33(4), 551–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701434060

- Trzesniewski, K. H., Donnellan, M. B., Moffitt, T. E., Robins, R. W., Poulton, R., & Caspi, A. (2006). Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.381

- Walsh, M. E., Galassi, J. P., Murphy, J. A., & Park-Taylor, J. (2002). A conceptual framework for counseling psychologists in schools. The Counseling Psychologist, 30(5), 682–704. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000002305002

- Welsh Assembly Government. (2008). School-based counselling services in wales: A national strategy. Department for children, education, lifelong learning and skills.

- Welsh Government. (2011). Evaluation of the Welsh school-based counselling strategy: Stage one report. Welsh Government Social Research.

- Young Minds. (2017). Impact Report. How we made a difference to children and young people in 2016-17. [online] Retrieved 10 January 2017. https://youngminds.org.uk/media/1578/impact-report-final-web.pdf