ABSTRACT

In this article, we propose a framework for understanding career guidance policy. We use a systems theory approach informed by Gramscian theories of politics and power to make sense of this complexity. Firstly, we argue that career guidance policy is made by and for people and that there is a need to recognise all of the political and civil society actors involved. Secondly, we argue that policymaking comprises a series of ideological, technical and practical processes. Finally, we contend that policymaking takes place in a complex, multi-level environment which is can be described across three levels as the policy framing, middle and street level tiers.

Introduction

In a quote often, but probably incorrectly attributed to Bismark, we are told that “laws are like sausages. You should never watch them being made”. However, for those of us interested in career guidance, studying laws, regulations, funding arrangements, and other policy instruments used by government, is critical. In this article we set out a theoretical framework which seeks to both account for how career guidance policy is made and provide a tool for understanding and analysing future policies. While this is intended as a theoretical argument which might be applicable to all forms of public policy supported career guidance, we mainly apply examples from the compulsory school system to illustrate our arguments. Compulsory education typically extends from age 4 to 16, however in many nations the (compulsory or near-compulsory) schooling system extends further often to 18.

We understand career guidance in expansive terms as describing all interventions that help “individuals and groups to discover more about work, leisure and learning and to consider their place in the world and plan for their futures” (Hooley et al., Citation2018, p. 20). We also recognise that career guidance is an activity which has been championed by international agencies as a key component of the public policy mix of education, skills and employment (Inter-Agency Working Group on Work-based Learning [WBL], Citation2019). While career guidance is an activity that extends way beyond the public sector, in many countries most career guidance is funded through the public purse (McCarthy & Borbély-Pecze, Citation2021; Watts, Citation2008) because it has been recognised to serve a wide range of policy goals and to offer benefits to both the individual and society as a whole (Robertson, Citation2021; Watts, Citation2004). This means that the making and implementing of public policy is an existential concern for the field.

While the literature on career guidance is strongly rooted in the discipline of psychology, there is a growing recognition that public policy frames the activity and a developing strand of research is focused on exploring the interaction between public policies and practice in the field (e.g. Debono, Citation2017; Irving, Citation2017; Melo-Silva et al., Citation2019). However, much of this literature begins with the existence of the policy rather than looking at how the policy comes into being. In other words, it focuses on the eating of the sausage rather than on its making. It also, in many cases, assumes a more linear relationship between policy and practice than we think is justified. McCarthy and Borbély-Pecze (Citation2021) opened up some important questions about the process of policymaking in their recent chapter on career guidance policy in the Oxford Handbook of Career Development which we build on, in this article, through a closer examination of the policymaking process for career guidance within compulsory education.

In the context of schools, career guidance typically is linked to and embedded within education policy and involves teachers as well as specialist careers professionals in delivering a wide range of educational and pastoral activities to support young people's careers, and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of educational systems (OECD, Citation2004). The broad definition of career guidance adopted in this article (Hooley et al., Citation2018) encompasses group learning and curriculum-based interventions that are sometimes referred to as “career education”. We prefer to group all school-based career guidance interventions together in part because the evidence suggests that the various approaches to career guidance that can be used within the education system are best understood as an interlinked whole rather than as a series of discrete interventions (Gatsby, Citation2014; Hooley et al., Citation2012).

Policymakers often have a strong involvement in determining the shape and resourcing of career guidance based in the education system and may even involve themselves in determining the curriculum and learning outcomes of such provision (Andrews, Citation2019). Consequently, career guidance in schools provides a rich context to theorise a framework for career guidance policymaking. We acknowledge that career guidance as public policy also intersects with other government policy areas, including employment, culture, and social inclusion, and we hope that future empirical work explores the applicability of our framework to the variety of practice context and policy agendas which characterise career guidance.

We argue that the making of policy is not just something that happens solely in government offices and is then transmitted unproblematically into practice, but rather is made and remade, implemented and ignored at various levels, and that only by examining this entire process is it possible to sufficiently understand career guidance policymaking. In particular, our framework reveals how policy subsystems and paradigms are connected to different stages of the career guidance policy cycle, which allows for an examination of how career guidance policy issues get on the government's agenda; how choices for addressing those issues are prioritised; how decisions are made on pursuing courses of action relevant to educational policy in schools; how efforts to implement career guidance policy in schools are organised and managed; and how evaluations of what is and is not working are undertaken and fed back into subsequent rounds of policymaking (Howlett et al., Citation2009).

What is policy and how is it made?

Policy is defined in a range of different ways. In Dye’s (Citation1972, p. 2) pithy maxim it is “anything a government chooses to do or not to do”. Policy initiatives commence when problems emerge as candidates for the government's attention. This initial stage is a fraught process, influenced by personal values and interests, where problems move from a subject of individual concern to becoming a public issue worthy of government attention (Baumgartner & Jones, Citation2009). Furthermore, as Skovhus and Thomsen (Citation2017) have shown, drawing on the work of Bacchi (Citation2009), the construction of the problem that career guidance is supposed to address, its itself a highly political act which ultimately frames the policy and practice that emerges.

Cochrane and Malone (Citation2014, p. 3) noted that policy does not just describe a government's decision or pronouncement because policy is an ongoing process of “laws, regulatory measures, courses of government action, and funding priorities” as well as the enforcement of these decisions. So, a government's career guidance policy might appear briefly in a manifesto and then reappear in consultations, green papers and ultimately in the movement of the ideas into law, but this is only the beginning of the policymaking process as the policy continues to develop as the government makes further statements, issues regulations for schools, provides funding, and enacts sanctions for non-compliance.

This process has conventionally been described in various versions of the Policy Cycle Model (PCM) (Brewer & deLeon, Citation1983; Howlett et al., Citation2017; Lasswell, Citation1956). This approach divides policymaking up into a series of rational processes beginning with the inception of the policy and usually ending with its evaluation and in some cases the dismantling of the policy or its transformation into something new. The advantage of PCM is that it breaks down the various components of policymaking in a way that allows for examination and evaluation. The disadvantage is that it suggests policymaking happens in a linear systematic fashion which does not capture its actual messiness. Furthermore, whilst there are some examples of this kind of systematic policy development, implementation, review and evaluation, such as the Europe 2020 strategy for sustainable growth (European Commission, Citation2010), in most cases the change of government and political and economic cycles disrupt this kind of rational approach.

In such definitions of policy and the policymaking processes, policymaking is viewed primarily as a matter of high politics and technocratic governance. Policies are made by governments and lived by citizens. However, other theories of policymaking recognise the importance of wider social and political actors including special interest groups (McFarland, Citation1992; Sabatier & Pelkey, Citation1987), political parties and movements (Burstein & Linton, Citation2002) and public opinion (Clawson & Oxley, Citation2017). Of particular importance to career guidance policy is recognising the impact, or potential impact, that the teaching and guidance professions can have both indirectly through representative bodies who often lobby government when policies are being created, and directly as professionals with the principal responsibility for implementing guidance policies. Finally, the role of the student, as an end user and key actor who is capable of influencing public policy, both consciously and unconsciously, through decisions to use or ignore career guidance services, is also crucial (Plant & Haug, Citation2018).

Policymaking as a complex and multi-stakeholder activity was theorised by Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier (Citation1994) through their Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF). The ACF analysis recognises that policymaking is not simply a neutral and rational process and emphasises that people engage in politics to turn their beliefs into action. So, career guidance professionals have a range of vested interests in policies which support professionalisation (Hooley et al., Citation2016), while governments are often looking for the field to contribute towards wider policy aims such as encouraging citizen investment in skills development (Bengtsson, Citation2011). In such a vision, policy emerges from the interaction between the coalitions that advocate for a variety of different positions. These coalitions can be both inside and outside of government. One of the key influences on career guidance policy is its role as a bridging object which connects different activities (learning, work, unemployment) and life stages, varying aims and different stakeholders (Bergmo-Prvulovic, Citation2018). Career guidance intersects many fields and policy areas including education, employment and social inclusion, and consequently is of interest to, and overseen by, multiple government departments, notably the education and labour ministries, which often have different policy aims in focus (McCarthy & Hooley, Citation2015).

Other theorists of policymaking emphasise the role that is played by the wider policy context and timing of policymaking (e.g. see Baumgartner & Jones, Citation2009; Kingdon, Citation1984). Such approaches discuss the fact that policymaking does not take place on a blank canvass, but rather within wider discourses, power structures and in response to political themes and events. Heikkila and Cairney (Citation2017) argued that policy environments are constituted of: actors including politicians, civil servants as well as those involved in delivering or receiving the service such as school leaders, teachers, parents, and students; institutions such as schools; networks and relationships between the actors and stakeholders; the ideas and beliefs that are held within the environment; and events which shape the context in which all of these interact.

Many of these discussions which describe the multi-actor nature of policymaking recall Gramsci's recognition of the importance of civil society as distinct from but intertwined with political institutions and power (Gramsci, Citation1957). Gramsci offers us the concept of hegemony which describes how the policies of the state combine with the actions, ideas and practices of civil society to create an underlying grammar of common sense for all actions. Successful policymaking in career guidance, at least in the terms of the architects of policies, could be said to be when schools and other providers of career guidance services have embedded the approach to career guidance outlined in the policy into their practices and have ceased to question it. Achieving this kind of hegemony is not possible through the provision of regulation or funding alone, but rather requires teachers, careers professionals, school leaders and their representatives to assimilate the logic of the policy into their thinking, practices and ethics.

Gramsci also offers us the concept of counter-hegemony, which recognises the possibility of contesting hegemony and explains how individuals and groups can establish alternative norms to those envisaged by policymakers and ultimately destabilise power and orthodoxy (Im, Citation1991). Central to Gramsci's discussion of hegemony and counter-hegemony is the recognition that this dialectic is played out on an unequal terrain in which those pursuing hegemony have more power than those seeking counter-hegemony. But it also acknowledges that the pursuit of policy aims either from above or below is not a forgone conclusion and that a multi-faceted process of struggle and contestation will be ongoing. This struggle is not just the struggle between Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier’s (Citation1994) advocacy coalitions, but also takes place on an ideological level both within and between individuals and institutions. Furthermore, the struggle is not contained within the policymaking process but continues into its implementation, evaluation and renegotiation.

In this expansive definition, policy is not just a list of government documents, but rather a system of discourse, actions and struggles that mediate between the state and actual career guidance practices. Consequently, policymaking does not cease when the ink is dry on a new set of statutory regulations, but rather continues as the policy is interpreted, implemented, and adapted.

A framework for career guidance policymaking

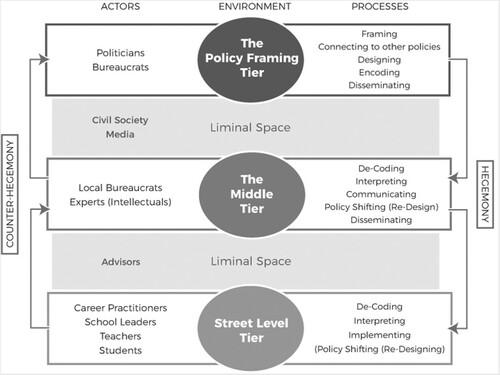

To help us in retheorising career guidance policymaking, we use three key concepts drawn from our discussion of policy theories. Firstly, we recognise that career guidance policy is something that is done by people, with, and to, other people. Given this, it is important to recognise the key actors who generate, influence, develop, implement and resist career guidance policy. Secondly, it is important to capture the processes and discourses that comprise the policymaking process for career guidance. And also, to acknowledge that the varied interests from different policy actors can lead to the failure or reworking of policies as well as the implementation of the government's objectives. Thirdly, we consider the environment in which career guidance policymaking takes place. We describe this in terms of three tiers: the policy framing tier, the middle tier, and the street level tier. We draw attention to the liminal spaces that exist between the different tiers, connecting them and allowing for ideas to pass both downwards (asserting hegemony) and upwards (through counter-hegemonic challenges) (see ).

Actors

Our first key concept recognises that the system in which the sausage is made comprises individuals and institutions organised into networks (Cairney, Citation2011; Weible et al., Citation2012). These policy networks are usually constituted of actors with knowledge or interest in a policy area (Howlett & Ramesh, Citation2002), who come together to focus on a particular policy within a territorial or other bounded situation (Weible et al., Citation2012). We organise these actors into the Gramscian categories of the state or political society and civil society. Political society includes those who play a formal role in developing state policy (e.g. politicians, including education ministers, and bureaucrats) and those with direct responsibility for implementing and ensuring compliance (e.g. school inspectors) (Howlett et al., Citation2009). Civil society includes: those involved in the formation and discussion of policy (e.g. the media, intellectuals, such as academics and think tanks, and representative and lobbying bodies such as teaching unions and career guidance professional bodies); those who translate and support its implementation (e.g. advisers such as career guidance specialists working for school boards and local government); and those whose actions it seeks to regulate (e.g. school leaders, teachers and careers professionals and ultimately students and service users) (Howlett et al., Citation2009). These are not distinct categories but have considerable overlap. So, for example, trade unions and professional associations are made up of teachers and careers professionals who may be involved both as actors in their own right (e.g. lobbying government) and in concert with their members (e.g. setting out advice on how to implement policies).

There is considerable overlap between political society and civil society. In the context of the delivery of career guidance in the compulsory education system, school leaders act as representatives of the state who police compliance with laws and regulations, but at the same time have status and authority which is derived from their position within civil society rather than their formal role as an agent of the state. The permeability of the distinction between political and civil society is in line with Gramscian theory which recognises the way in which civil society is both distinct from political society whilst often being actively co-opted as a partner in the creation of hegemony (Gramsci, Citation1999). This is useful because it moves us away from viewing career guidance policy as a high politics action which is “done to” the career guidance profession or to end users. It acknowledges the way in which civil society actors, including the career guidance profession, are co-opted as co-producers who have to actively undertake the work of balancing their values and professional practice with the demands of the current policy agenda.

Political society

Within political society, there are several actors who influence career guidance policymaking. Elected politicians may be divided into members of the executive and legislators (Bernier et al., Citation2005), with the executive often controlling funding and regulation and providing access to resources. In some cases, governments directly develop policy targeted at shaping career guidance, but more usually career guidance policy is a secondary outcome of wider policies which seek to shape the education and employment systems or other aspects of society. For example, reforms to vocational education and apprenticeship systems shifts the context for career guidance even when the policies do not explicitly mention career guidance (Watts, Citation2009).

Elected representatives outside of the executive often have a role in holding the government accountable and scrutinising policy (Howlett et al., Citation2009). This can prove to be important for small policy areas like career guidance because it can bring to the surface issues that received scant attention during either electoral politics or legislative processes. An example can be seen in the UK where parliamentarians outside of the government have conducted numerous reviews which have examined career guidance policy either directly (e.g. House of Commons Sub-Committee on Education, Skills and the Economy, Citation2016) or as part of wider policy scrutiny.

It is also important to recognise the role of unelected policy actors within political society. Bureaucrats are appointed officials who assist the government, and they have access to a significant range of resources to support or hinder the policymaking process. Diffusion of power within bureaucracy is important and has a significant impact upon policymaking processes (Atkinson & Coleman, Citation1989). Because career guidance is often viewed as a minor policy area which may not attract the sustained attention of elected officials, this can mean that bureaucrats have considerable influence over career guidance policy. For example, Jenson’s (Citation2020) account of the development of the Danish guidance system in the last 20 years highlighted the control bureaucrats working for ministries and other government agencies had to shape guidance policy within the broad framework of legislation sponsored by the elected government.

At a more localised level, political society consists of local elected officials and bureaucrats (LeRoux, Citation2014) who are charged with implementing policies for government, but who also have some capacity to shape policies in line with local concerns. These can include local counsellors, leaders of school boards, local education structures, and school inspectors who have a compliance role.

Civil society

There are several actors within civil society who influence career guidance policymaking and implementation. Interest groups influence policy through advocating for the economic interests or social values of their members (Walker, Citation1991). In the context of career guidance policymaking these groups include career guidance professional associations, trade unions (notably the teaching unions), and employers’ associations, who all have particular perspectives on and knowledge about career guidance policy issues. Given that policymaking is an information-intensive process, such knowledge can be of immense value (Howlett et al., Citation2009).

A further set of societal actors of influence are researchers working in universities, institutes, and think-tanks (what Gramsci, Citation1999, describes as “intellectuals”). These researchers often have theoretical and philosophical interests in career guidance that can be directly translated into the policymaking process. For example, provincial governments in Canada often consult with a range of policy experts, researchers, and career guidance coordinators from differing district school boards during the policymaking process (Godden, Citation2016). As Gramsci explains, while these intellectuals bring important technical knowledge into the policymaking process, they are not independent of politics nor separate from the state, but rather in the same dialectical relationship with it as other members of civil society. In practice this can often be seen in the way that such intellectuals, whether working for universities or think tanks, are involved in funded research projects commissioned by government or other actors to inform, shape and evaluate career guidance policy.

The media potentially has an important influence on career guidance policymaking. The mass media has been said to play a pivotal role in public policymaking processes (e.g. Herman & Chomsky, Citation1988; Parenti, Citation1986) as it exerts considerable influence on how public policy problems and solutions are presented to, and understood by the public (Cairney, Citation2015). The way in which the media frames public policy questions also influences members of political society and results in some policy approaches being excluded whilst others are championed. While career guidance policy is rarely a central concern to the mass media, it will sometimes receive coverage in more specialist education trade press. Perhaps more importantly, the media has a role to play in shaping public perception of the concept of career and the role of career guidance within it.

Civil society also encompasses school leaders, teachers and careers professionals who are directly responsible for enacting the practice of career guidance. Career guidance policy is designed to regulate the behaviours and practices of these actors, and they are active participants in the processes of interpretation and translation that transforms career guidance from a policy document into a lived practice. Ball et al. (Citation2011a, Citation2011b) outline a useful framework that identifies a number of different roles that individuals within the school system undertake when implementing career guidance policy in schools. For example, school leaders and administrators are likely to determine selection of the types of career guidance provision required in their school and determine how this is enforced. Those who believe in the value of career guidance will likely undertake policy advocacy within schools, and consist of actors that “champion and represent particular policies” (p. 628). Ball et al. stress the importance of remembering that policy actors in schools sometimes undertake policy work with others (e.g. consultants, local authority advisers, outside agencies) who play an important role in policy implementation, interpreting policies and initiating or assisting with translation.

Schools are complex, dynamic environments consisting of “multiple interacting parts” (Ball et al., Citation2011a, p. 637), and what Law (Citation2007, p. 2) called “the messy practices of relationality and materiality of the world”. Actors and their roles are not necessarily stable or mutually exclusive, as they may move between these roles or hold more than one role at any one time. In addition, we need to draw attention to people's formal as well as informal roles. For example, someone may be a contractor responsible for implementing government policy, but through their professional association they may also be lobbying for change to that policy. These formal and informal roles will frequently be in tension. Furthermore, prior training and experience with policy has influence and impact on subsequent policy interpretation and implementation (Coburn, Citation2005; Spillane et al., Citation2002). Consequently, career guidance policymaking is not an abstract process, it is something undertaken by people for people, and their levels of engagement with and contributions to this process are crucial.

Career guidance policymaking has its end point in a range of services, opportunities and programmes that are co-created by educators and careers professionals and made available to individual citizens. How educators choose to react to such policies can have a pivotal role in their success or failure. The decision to engage or disengage with the policy can ultimately shape both the policy itself and the way in which it is experienced (Löfgren et al., Citation2018). Within schools, students are not solely passive recipients of educational policy, but are in fact involved with these policies (albeit often without a technical awareness of the details of the policy) and keen to “have a say” in how they are implemented (Wilkinson & Penney, Citation2020). In looking at students’ responses to physical education policy, Wilkinson and Penney (Citation2020) argued that students, like their teachers, played a range of roles in responding to policies. These include coping with the policy and seeking to survive it as well as adopting more active positions where they develop analyses and critiques of the policy and either advocate for it or resist it. It is not difficult to imagine that students might be similarly engaged with career guidance policy, and this is an area of career guidance policymaking that warrants further investigation.

Processes

So far, we have looked at who is doing policy. Our argument is that rather than seeing policymakers as an elite group operating solely in government buildings, we should view K-12 career guidance policymaking as a diffuse process that is undertaken by a wide range of actors. However, actors are not all doing the same thing to develop, disseminate and implement policy. In this section we turn to look at the various processes that take place within policymaking. We organise the different policymaking processes under three headings. Firstly, ideological processes frame and reframe the policy through narratives about what policy aims career guidance is supposed to impact on and what and who the policy is for. Secondly, a range of technical processes create artifacts of discourse that comprise the “policy” as it is usually understood and the guidance and marginalia that surround it. Thirdly, there are a range of practical processes through which the policy is operationalised into career guidance practices.

Ideological processes

The creation of a policy is an ideological and political act. As such it is a narrative, a creation of a story about what the problem is (Skovhus & Thomsen, Citation2017), what needs to be changed, and how such a change might improve the world. Watts (Citation2015) provided a powerful example of the impact of such ideological work in his description of the way in which “social exclusion” was introduced in the late 1990s in the UK as the primary framing concept for a range of educational and social policies including career guidance. From this ideological shift a range of technical decisions flowed about the funding and organisation of career guidance services which Watts argued were ultimately of detriment to the field. In other cases, the creation of a new framing device for career guidance resulted in increased status or funding (e.g. the adoption by the Council of the European Union [Citation2004, Citation2008] of resolutions to integrate lifelong guidance into lifelong learning strategies). As these examples show, for career guidance the ideological processes that underpin the development of policies are often about linking career guidance with wider narratives and trends in policymaking and using these narratives to justify policy attention.

Actors operating in political society engage in processes of narrative making through the development of speeches, articles and think pieces, political manifestos, green and white papers and through governing. Actors operating in civil society undertake ideological processes through the lobbying of government and through forms of public discourse which seek to raise concerns, popularise new analyses and narratives and propose or suggest possible solutions. This concept of shaping the ideological space within which policies can be created has been popularised in the idea of the Overton Window (Mackinac Centre for Public Policy, Citation2019) which suggests that public opinion limits what is possible for policymakers, that public opinion can change, and that interested actors can be part of shifting public opinion. The Overton Window's representation of public policy as an essentially binary scale of pre-existing policy ideas is not particularly relevant to career guidance policy, but the recognition that public opinion, elite media and intellectual discourses are dynamic and ultimately shape the policymaking process is very useful.

Such ideological processes do not end once a policy direction is agreed upon. Rather policy actors continue to make the case for the policy (hegemony) and dispute and contest it (counter-hegemony). As such these ideological processes are important for both the creation of policies and their implementation and enactment.

We have already argued that both educators and students are involved in advocating for, contesting and critiquing policies as they are implemented in schools. Ball et al. (Citation2011a) captured this process of debate and discussion about the validity of policies at the point of implementation. They pointed out that critical actors continued to advance ideological critiques at this point, for example by highlighting the impact that a new policy can have on the work-life balance of teachers or contesting whether the provision of career guidance is compatible with educators’ wider responsibilities. Such critiques need to be understood as operating on both an ideological and a practical level as educators seeks to answer the intertwined questions of what is worth doing and what they have the time and resource to do.

Technical processes

Policymaking is also a technical process. Policies are encoded in Vedung’s (Citation1998) three types of policy instrument regulations (laws, rules and directives), economic incentives (funding agreements and the provision of other resources) and information (including advisory documents, curricula and other forms of public or professional information). Bureaucrats are particularly critical to this process whereby political commitments are transformed into concrete documents in which the policy is set out (Savickas et al., Citation2005). Inevitably this process of encoding introduces new elements, perhaps resolving gaps in the ideological narrative, linking to other policies and providing further detail and explanation of how the career guidance policy should be implemented.

Encoded policies can be difficult for the range of educational policy actors to fully access (Grubb, Citation2004). In particular, career guidance practitioners often struggle for time to engage with policy documents and may lack the skills and experience to successfully decode legalistic policy documents. So, the process of encoding is often followed by a process of recoding whereby governmental documents are turned into practical guidance, frequently asked questions documents, case studies and curriculum resources designed to provide greater context for those involved in implementation. Such recoding is normally done by policy intermediaries operating in the middle tier between government and practice. Advisors (e.g. career guidance specialists employed by local government to work with groups of schools), professional associations and experts help practitioners to make sense of what the policy says. This recoding process also presents opportunities to emphasise and deemphasise particular aspects of the policy, to add context and to make links to what they consider good practice and so on. Consequently, recoding is not neutral, but rather a way of engaging in hegemonic and counter-hegemonic processes.

Finally, those in practice undertake a further range of processes to decode what they have been presented with by policy and by others who have sought to recode it for them. These include reading, annotating, planning lessons and interventions and linking what they are being asked to do with their existing practice (Godden, Citation2020). This process is by its nature a dynamic one as policy documents are transformed into learning interactions such as career counselling interventions, career education lessons and programmes of work experience. Some of these approaches to practice may be innovations that were not explicitly addressed in the policy documentation. This process of encoding, recoding and decoding therefore offers multiple opportunities for what is put into practice to look very different from what was originally intended.

Practical processes

Ultimately the sausage has to be eaten. In the case of career guidance policies, it is usually in the conduct of an interview or the delivery of a careers lesson or careers programme. What is delivered and how it relates to the policy originally encoded by politicians and bureaucrats will depend in part on the range of actors who have been involved in transmitting the policy to the school or relevant professional. However, it will also be shaped by a range of practical considerations around resourcing, delivery and reception.

Practitioners have a range of decisions to make about how policy initiatives are delivered. They need to decide how innovations driven by policy are combined with existing practices, where and when they are delivered and to what students. Finally, the students also have an important role in shaping what is received, understood and engaged with. They determine whether the sausage is edible or not. Despite the best efforts of policymakers and educators some policies inevitably fail to engage, inform the thinking and shift the behaviour of some learners.

Environment

Educational policy moves through multiple tiers as it is developed, contested and implemented. These might include the involvement of national government, state or local authorities, school boards or management structures, school administration, and the classroom (McLaughlin, Citation1987). What is more, career guidance is a very particular type of educational activity because it is concerned with preparation for and transition into the labour market and post-school life. This means that career guidance is one of the places where the educational system interacts with the labour market and economic planning structures.

As career guidance policies move through these bureaucratic systems and other systems and sub-systems, there are multiple opportunities for policies to be recast and reframed (Howlett et al., Citation2009). Consequently, it is important to emphasise the recursive nature of policy development and implementation (Hill & Hupe, Citation2009). Policy is not developed and transmitted through a straightforward implementation process, but is rather passed between a range of actors in a series of overlapping ideological, technical and practical processes.

The dynamic process of policymaking and implementation is shaped by the milieu in which it is situated including the legal, political, cultural, demographic, ecological, economic, cultural, and technological structures and systems (Howlett et al., Citation2009). So, career guidance policy is embedded into and interactive with a wide range of other systems. This means that the nature of career guidance policy is particular to different nations and states as different political systems have distinctive authoritative sites, formal and informal rules of politics, networks of power, ways to describe how the world works and should work, and socioeconomic contexts (Cairney, Citation2019). Returning again to the sausage analogy, when we examine how the sausage gets made, we can begin to understand the many national, regional, and local facets that determine what ingredients are permissible and the localised tastes that define its final flavour. Consequently the flavour of career guidance policy is shaped by the environment in which it is situated, and neither career guidance policy nor individual behaviour in its implementation can be fully understood in isolation from the social, economic, and political contexts within which they function (Herr, Citation1996).

The environment in which career guidance policy is developed also needs to be understood as a historical one which develops over considerable time periods especially where new policies are substantial and complex (Kirst & Jung, Citation1980). New career guidance policies interact with previous generations of policy which have developed over time through a series of incremental changes that involve layering where new policy is introduced and previous policy is left in place (Howlett & Rayner, Citation2014), drift where the meaning of policy gradually moves away from its original intent (Hacker, Citation2004), conversion where new goals are adopted for the policy, or new actors are affected by the policy (Béland, Citation2007), or reformulation such as redesign where street level bureaucrats for example, make deliberate attempts to influence and affect policy outcomes (Cohen & Klenk, Citation2019). While politicians and bureaucrats can create new policies, these policies enter a complex milieu within which practice operates. Practitioners need to align new policies and processes with the existing bureaucracy, regulations and “common sense” of the environment in which they operate, connecting it with existing subsystems and routines in their world and inevitably transforming it as they do this.

The framework that we are using to understand career guidance policy is essentially a systems theory one. Systems theory has been used to effectively to analyse policy (Stewart & Ayres, Citation2001) as well as career and career guidance (Collin, Citation2012; Patton & McMahon, Citation2006). Its advantage is that it is capable of taking into account that multiple things are taking place, each with their own logics and dynamics, at the same time identifying the inter-dependencies between these different systems.

Our framework identifies three environmental subsystems through which career guidance policy operates: the policy-framing tier, the middle tier, and the street level tier. We have already drawn attention to a variety of actors that operate within and in the liminal spaces between these three tiers whilst they engage in a range of processes.

The policy framing tier

Governments have an important role to play in the strategic leadership and coordination of career guidance (Watts, Citation2004). However, governments neither speak with a single voice, nor do they make policy in isolation. Even the most detailed political manifestos rarely have fully worked out career guidance policies within them. So, policies are often grown, developed or created as part of governing with a variety of different actors and political factors playing a role. This process of agile or reactive policymaking is likely to be more evident in a “small” policy area like career guidance which is unlikely to be a key plank of any government's manifesto. In other words, governments are often in the process of working out career guidance policy and one of the places that this working out takes place in in the policy framing tier.

The policy framing tier is not a synonym for government. It includes a range of actors from both political (notably politicians and bureaucrats) and civil society (notably the media, intellectuals and special interests like teaching associations). The policy framing tier describes the space within which the ideological and technical process of policymaking are conducted. It includes spaces within government, both behind closed doors and in public, as well as those outside of government. It is a space made of discourse, but shaped by the relative power of the different actors within it.

The weakness of the policy framing tier is that it has, at best, a limited connection to practice. This means that while it can identify resources, draw up rules and proclaim on what should happen, actors within the policy framing tier cannot actually make anything happen directly. As an example of this weakness, the People for Education (Peterson & Hamlin, Citation2017) review of the implementation of the 2013 Creating Pathways to Success (a policy intended to support students in Ontario, Canada with career planning and transitions), reported that only 15% of elementary and 39% of secondary schools had implemented the required career and life planning committees necessary for satisfactory policy implementation some four years after the policy was rolled out across the province.

The middle tier

Underneath the policy framing tier is a network of actors concerned with implementation and the recoding of policy for its use in practice. The middle tier is not composed of practitioners, but rather of advisors, inspectors, commentators and trainers. These may be local bureaucrats or representatives of sector bodies, professional associations and other intermediaries that sit between government and practice.

Like the policy framing tier, the middle tier is not a single organisation, but rather a network of organisations and individuals linked through discourse (Bubb et al., Citation2019). The middle tier is the level at which the accountability structures for career guidance are placed, where what constitutes quality is defined and managed, and where institutions are supported to develop their career guidance practice and train their staff. The middle tier also serves as a link between policy and practice, with many of the actors who are most active in the middle tier interacting frequently with both policymakers and practitioners.

The street level tier

Finally, the street level describes the context where policies are actually enacted. In the context of career guidance in the compulsory education system, this street level will usually be a school or college. McCarthy and Borbély-Pecze (Citation2021) draw on the work of Goodin et al. (Citation2011) to introduce the idea of career guidance professionals as “street level bureaucrats”. This concept is powerful because it recognises that the street level, as the site of practice, is not just a place in which policy is implemented, but also a place in which it is recoded and decoded before being put into practice.

Individual practitioners, as “street-level bureaucrats” have the capacity to influence and reshape policies through the practice decisions that they make. However, they do this within the environmental context of the “street” in which they operate. Institutions rarely choose the end users that they serve and have to make decisions about how much they would like to, and are capable of, resourcing the activity. In the case of schools this often results in decisions about how many students receive careers interviews and how much curriculum time is devoted to careers education. Inevitably the demography, geography and resourcing situation of each street will make a big difference to the impact of the policy.

In some cases, policies will be accompanied by an increase in funding, which McCarthy and Borbély-Pecze (Citation2021) argue is one of the key policy instruments available to governments to engage actors in career guidance. In effect, new funding is a direct tool to shift the environment of the street-level and make it more conducive to career guidance. Where decisions about the resourcing of career guidance are made locally, the street-level environments in which career guidance policy is being implemented become more variable which ultimately empowers street level bureaucrats at both leadership and practice levels further. For example, McGowan et al. (Citation2009) found that the devolution of budgets and responsibilities to the middle tier (local government) resulted in diverse interpretations and implementation of career guidance policy across England. While the subsequent devolution of responsibility down to the school resulted in even further variability and necessitated policymakers to actively create a street-level bureaucrat within schools, in the form of the careers leader, to manage the implementation of the policy agenda (Andrews & Hooley, Citation2017; The Careers & Enterprise Company, Citation2018).

If funding can be seen as a “carrot” that can change the environment and motivate and enable key actors, it is also clear that governments will sometimes use the “stick” to achieve the same ends. Heightened regulation and sanctions for not engaging with career guidance can also shape the environment, but such approaches also raise questions about how deviation from the policy can be identified and how compliance can be ensured.

Conclusion

In this article we have set out a new framework for understanding career guidance policy. We have deliberately chosen to focus on the making of the sausage rather than on its eating. In doing so we affirm that the process of policymaking is indeed a messy one. The neat, tidy, rational and technocratic description of the process set out by the Policy Cycle Model (PCM) makes for a poor description of how career guidance policy is made. The reality is more complex: involves far more people and the interplay of power, ideology and self-interest; and can only be understood through examining its multiple layers. Furthermore, it is not something that takes place solely within the seats of government, but rather in a complex iterative conversation between the policy framing tier, middle tier and the street level.

We have tried to make sense of this complexity using a systems theory approach informed by Gramcian theories of politics and power. We began by recognising that policy is made by and for people and therefore argue there is a need to recognise all of the people involved in this process of policymaking including both political and civil society actors. We suggest career guidance policy making is an active process of doing and applying and that it must be understood as comprising ideological, technical and practical processes. Finally, we acknowledge that policymaking takes place in a complex, multi-level environment which we highlight through policy framing, middle and street level tiers.

This theoretical framework is designed to help both researchers and policymakers to examine and disrupt the policymaking process. We hope it provides researchers with a framework for analysis that reveals and helps in managing the complexity of the policymaking process. We also hope that it will avoid the tendency to view governments as subjects and the career guidance profession and its clients as objects. Our focus on the power dynamics between the different actors in the policymaking process recognises that there is power and influence at all levels and draws attention to how intended policy does not necessarily result in enacted and experienced policy. We believe that the framework will help to reveal whether any policy change causes the career guidance policy universe to expand or contract, and to take into account and understand the impacts of policy changes on career guidance practitioners and other policy actors.

This article also provides a reflect tool for those involved in the creation and implementation of career guidance policy. It encourages politicians and bureaucrats to examine their positions of power, and through empathy and humility to recognise that without the other actors in the system, effective policy change cannot happen. It also encourages teachers, guidance practitioners, school leaders, trainers, advisors and inspectors to recognise their roles within the career guidance policy universe and the associated power that they hold to make and remake career guidance policies, and to support and challenge hegemony where needed. Ultimately, we hope all actors will be more aware of how the policymaking process works, and through this understanding of the system, we can increase the democracy, responsiveness and effectiveness of the career guidance policies that are formed and implemented.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tristram Hooley

Tristram Hooley is a researcher and writer specialising in career and career guidance. He is Professor of Career Education, University of Derby, UK; Professor II, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Norway; and Chief Research Officer at the Institute of Student Employers (ISE), UK. His research focuses on the interrelationships between career, career guidance, politics, technology and social justice.

Lorraine Godden

Lorraine Godden is an Instructor II at Carleton University, Canada, where she teaches career development, employability, and career management skills courses in the Faculty of Public Affairs. Her research is rooted in understanding how educators interpret policy and curriculum to make sense of career development and employability, work-integrated learning, adult education, school-to-work transition, and other educational multidisciplinary and public policies.

References

- Andrews, D. (2019). Careers education in schools. David Andrews.

- Andrews, D., & Hooley, T. (2017). ‘ … and now it’s over to you’: Recognising and supporting the role of careers leaders in schools in England. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 45(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2016.1254726

- Atkinson, M. M., & Coleman, W. D. (1989). Strong states and weak states: Sectoral policy networks in advanced capitalist economies. British Journal of Political Science, 19(1), 47–67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/193787. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400005317

- Bacchi, C. (2009). Analysing policy: What’s the problem represented to be? Pearson Australia.

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Hoskins, K. (2011a). Policy actors: Doing policy work in schools. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 625–639. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2011.601565

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Hoskins, K. (2011b). Policy subjects and policy actors in schools: Some necessary but insufficient analyses. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 611–624. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2011.601564

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (2009). Agendas and instability in American politics (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Béland, D. (2007). Ideas and institutional change in social security: Conversion, layering, and policy drift. Social Science Quarterly, 88(1), 20–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00444.x

- Bengtsson, A. (2011). European policy of career guidance: The interrelationship between career self-management and production of human capital in the knowledge economy. Policy Futures in Education, 9(5), 616–627. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2011.9.5.616

- Bergmo-Prvulovic, I. (2018). Conflicting perspectives on career. Implications for career guidance and social justice. In T. Hooley, R. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism (pp. 143–158). Routledge.

- Bernier, L., Brownsey, K., & Howlett, M. (2005). Executive styles in Canada: Cabinet structures and leadership practices in Canadian government. Institute of Public Administration of Canada Series in Public Management and Governance. University of Toronto Press.

- Brewer, G., & deLeon, P. (1983). The foundations of policy analysis. Dorsey Press.

- Bubb, S., Crossley-Holland, J., Cordiner, J., Cousin, S., & Earley, P. (2019). Understanding the middle tier. Comparative costs of academy and LA-maintained school systems. http://www.sarabubb.com/middle-tier/4594671314.

- Burstein, P., & Linton, A. (2002). The impact of political parties, interest groups, and social movement organizations on public policy: Some recent evidence and theoretical concerns. Social Forces, 81(2), 380–408. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2003.0004

- Cairney, P. (2011). Understanding public policy: Theories and issues. London: Red Globe Press.

- Cairney, P. (2015). How can policy theory have an impact on policymaking? The role of theory-led academic-practitioner discussions. Teaching Public Administration, 33(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739414532284

- Cairney, P. (2019). Understanding public policy (2nd ed.). Red Grove Press.

- The Careers & Enterprise Company. (2018). Understanding the role of the careers leader.

- Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (2017). Public opinion: Democratic ideals, democratic practice. Sage.

- Coburn, C. E. (2005). Shaping teacher sensemaking: School leaders and the enactment of reading policy. Educational Policy, 19(3), 476–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904805276143

- Cochrane, C. L., & Malone, E. F. (2014). Public policy: Perspectives and choices (5th ed.). Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Cohen, N., & Klenk, T. (2019). Policy re-design from the street level. In P. Hupe (Ed.), Research handbook on street level bureaucracy: The ground floor of government in context (pp. 209–223). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Collin, A. (2012). The systems approach to career. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 28, 3–9.

- Council of the European Union. (2004). Council resolution on strengthening policies, systems and practices in the field of guidance throughout life in Europe. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/educ/104236.pdf.

- Council of the European Union. (2008). Council resolution on better integrating lifelong guidance into lifelong learning strategies. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/educ/104236.pdf.

- Debono, M. (2017). Career education and guidance in Malta: Development and outlook. In R. G. Sultana (Ed.), Career guidance and livelihood planning across the Mediterranean (pp. 337–350). Brill Sense.

- Dye, T. R. (1972). Understanding public policy. Prentice-Hall.

- European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020. A European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf.

- Gatsby Charitable Foundation. (2014). Good career guidance.

- Godden, L. (2016). Interpreting documents and making sense of public policy goals for career guidance in secondary schools: A multi-perspective empirical comparative study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Queen’s University.

- Godden, L. (2020). Career guidance policy documents: Translation and usage. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1784843

- Goodin, R. E., Rein, M., & Moran, M. (2011). Overview of public policy: The public and its policies. In R. E. Goodin, M. Rein, & M. Moran (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political science (pp. 3–38). Oxford University Press.

- Gramsci, A. (1957). The modern prince and other writings. International Publishers.

- Gramsci, A. (1999). Selections from the prison notebooks. The Electric Book Company.

- Grubb, W. N. (2004). An occupation in harmony: The roles of markets and government in career information and guidance. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 4(2-3), 123–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-005-1743-1

- Hacker, J. S. (2004). Privatizing risk without Privatizing the welfare state: The hidden politics of social policy retrenchment in the United States. American Political Science Review, 98(2), 243–260. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4145310?origin=JSTOR-pdf. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055404001121

- Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books.

- Herr, E. L. (1996). Perspectives on ecological context, social policy, and career guidance. The Career Development Quarterly, 45(1), 5–19. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00458.x. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00458.x

- Heikkila, T., & Cairney, P. (2017). Comparison of theories of the policy process. In C. M. Weible & P. A. Sabatier (Eds.) Theories of the policy process (pp. 299–326). New York: Routledge.

- Hill, M., & Hupe, P. (2009). Implementing public policy (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hooley, T., Johnson, C., & Neary, S. (2016). Professionalism in careers. Careers England & Career Development Institute.

- Hooley, T., Marriott, J., Watts, A. G., & Coiffait, L. (2012). Careers 2020: Options for future careers work in English schools. Pearson.

- Hooley, T., Sultana, R. G., & Thomsen, R. (2018). The neoliberal challenge to career guidance: Mobilising research, policy and practice around social justice. In T. Hooley, R. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism (pp. 1–28). Routledge.

- House of Commons Sub-Committee on Education, Skills and the Economy. (2016). Careers education, information, advice and guidance. House of Commons.

- Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2002). The policy effects of internationalization: A subsystem adjustment analysis of policy change. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 4(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014971422239

- Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., & Perl, A. (2009). Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems. Oxford University Press.

- Howlett, M., McConnell, A., & Perl, A. (2017). Moving policy theory forward: Connecting multiple stream and advocacy coalition frameworks to policy cycle models of analysis. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 76(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12191

- Howlett, M., & Rayner, J. (2014). Patching vs packaging in policy formulation: Assessing policy portfolio design. Politics and Governance, 1(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12924/pag2013.01020170

- Im, H. B. (1991). Hegemony and counter-hegemony in Gramsci. Asian Perspective, 15(1), 123–156.

- The Inter-Agency Working Group on Work-based Learning (WBL). (2019). Investing in career guidance. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/2227_en.pdf.

- Irving, B. A. (2017). 3 the pervasive influence of neoliberalism on policy guidance discourses in career/education. In T. Hooley, R. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism (pp. 47–62). Routledge.

- Jenkins-Smith, H. C., & Sabatier, P. A. (1994). Evaluating the advocacy coalition framework. Journal of Public Policy, 14(2), 175–203. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:cup:jnlpup:v:14:y:1994:i:02:p:175-203_00. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00007431

- Jenson, S. (2020). Guidance in the Danish educational sector. In E. Haugh, T. Hooley, J. Kettunen, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career and career guidance in the Nordic countries (pp. 109–126). Brill.

- Kingdon, J. (1984). Agendas, alternatives and public policies. Harper Collins.

- Kirst, M. W., & Jung, J. (1980). The utility of a longitudinal approach in Assessing implementation: A thirteen-year view of title I, ESEA. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 2(5), 17–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v5n15.1997

- Lasswell, H. D. (1956). The decision process: Seven categories of functional analysis. University of Maryland Press.

- Law, J. (2007). Actor network theory and material semiotics. http://www.heterogeneities.net/publications/Law2007ANTandMaterialSemiotics.pdf.

- LeRoux, K. M. (2014). Local bureaucracy. In D. P. Haider-Markel (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of state and local government (pp. 489–509). Oxford University Press.

- Löfgren, H., Löfgren, R., & Prieto, H. P. (2018). Pupils’ enactments of a policy for equivalence: Stories about different conditions when preparing for national tests. European Educational Research Journal, 17(5), 676–695. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904118757238

- Mackinac Center for Public Policy. (2019). The Overton window. https://www.mackinac.org/OvertonWindow.

- McCarthy, J., & Borbély-Pecze, T. B. (2021). Career guidance living on the edge of public policy. In P. J. Robertson, T. Hooley, & P. McCash (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of career development (pp. 95–112). Oxford University Press.

- McCarthy, J., & Hooley, T. (2015). Integrated policies: Creating systems that work. Kuder.

- McFarland, A. S. (1992). Interest groups and the policymaking process: Sources of countervailing power in America. In M. Petracca (Ed.), The politics of interests (pp. 58–79). Routledge.

- McGowan, A., Watts, A. G., & Andrews, D. (2009). Local variations: A follow-up study of new arrangements for connexions/careers/IAG services for young people in England. CfBT.

- McLaughlin, M. W. (1987). Learning from experience: Lessons from policy implementation. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 9(2), 171–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1163728

- Melo-Silva, L. L., Munhoz, I. M. D. S., & Leal, M. D. S. (2019). Professional guidance in elementary school as public policy in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Orientação Profissional, 20(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.26707/1984-7270/2019v19n2p133

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2004). Career guidance and public policy: Bridging the gap. Paris: OECD.

- Parenti, M. (1986). Inventing reality: The politics of the mass media. St. Martin’s Press.

- Patton, W., & McMahon, M. (2006). The systems theory framework of career development and counseling: Connecting theory and practice. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 28(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-005-9010-1

- Peterson, K., & Hamlin, D. (2017). Career and life planning in schools: Multiple paths; multiple policies; multiple challenges. People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Career-and-life-planning-in-schools-2017.pdf

- Plant, P., & Haug, E. H. (2018). Unheard: The voice of users in the development of quality in career guidance services. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 37(3), 372–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2018.1485058

- Robertson, P. J. (2021). The aims of career development policy: Towards a comprehensive framework. In P. J. Robertson, T. Hooley, & P. McCash (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of career development (pp. 113–118). Oxford University Press.

- Sabatier, P. A., & Pelkey, N. (1987). Incorporating multiple actors and guidance instruments into models of regulatory policymaking: An advocacy coalition framework. Administration & Society, 19(2), 236–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/009539978701900205

- Savickas, M. L., Van Esbroeck, R., & Herr, E. L. (2005). The internationalization of educational and vocational guidance. The Career Development Quarterly, 54(1), 77–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2005.tb00143.x

- Skovhus, R. B., & Thomsen, R. (2017). Popular problems. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 45(1), 112–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2015.1121536

- Spillane, J. P., Diamond, J. B., Burch, P., Hallett, T., Jita, L., & Zoltners, J. (2002). Managing in the middle: School leaders and the enactment of accountability policy. Educational Policy, 16(5), 731–762. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/089590402237311

- Stewart, J., & Ayres, R. (2001). Systems theory and policy practice: An exploration. Policy Sciences, 34(1), 79–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010334804878

- Vedung, E. (1998). Policy instruments: Typologies and theories. In M.-L. Bemelmans- Videc, R. C. Rist, & E. Vedung (Eds.), Carrots, sticks, and sermons: Policy instruments and their evaluation (pp. 21–58). Transaction Publishers.

- Walker, J. L. (1991). Mobilizing interest groups in America: Patrons, professions and social movements. University of Michigan Press.

- Watts, A. G. (2004). Career guidance and public policy: Bridging the gap. OECD Publishing.

- Watts, A. G. (2008). Career guidance and public policy. In J. A. Athanasou & R. Van Esbroeck (Eds.), International handbook of career guidance (pp. 341–353). Springer.

- Watts, A. G. (2009). The relationship of career guidance to VET. OECD Publishing.

- Watts, A. G. (2015). Career guidance and social exclusion: A cautionary tale. In T. Hooley & L. Barham (Eds.), Career development policy and practice: The Tony Watts reader (pp.221-240). Highflyers.

- Weible, C. M., Heikkila, T., deLeon, P., & Sabatier, P. A. (2012). Understanding and influencing the policy process. Policy Sciences, 45(1), 1–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41487060. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-011-9143-5

- Wilkinson, S. D., & Penney, D. (2020). Setting policy and student agency in physical education: Students as policy actors. Sport, Education and Society, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1722625