ABSTRACT

Bereaved people frequently report perceiving the continued presence of the person they lost in the form of a voice, a vision, a felt presence or any other sensory perception. This report explores this psychological phenomenon, experiences of presence, using narrative interviewing and analysis. Ten people were interviewed, in English or Spanish, using a biographical narrative procedure. The analysis, part of a project focused on unwelcome continued presences, was focused on the sources of distress, ambivalence and comfort reported in participant narratives on their experiences, as well as on the sociocultural processes influencing them. Identified properties were grouped into nine categories, with this report being primarily focused on sources related to distress, or ambivalence, and their relevance for clinical practice.

Introduction

Losing a loved one can shatter the worldview of the mourner, not solely because of the direct impact of the loss, and the drive to make sense of it, but also because of the need to re-construct one’s identity without them (Neimeyer, Citation2000, Citation2011). From a narrative perspective, our identity is primarily constructed through the stories we tell each other and to ourselves: the recounting of our past, the sense-making of other people’s behaviour, and the imagining of our future (Polkinghorne, Citation1988; Sarbin, Citation1986). Even afterlives, as Murray (Citation2003) highlighted, are described in a narrative way. The shattering of a shared life-story that can follow a bereavement can thus launch the mourner into the process of adapting or repairing the emplotmentFootnote1 of their self-narrative.

The literature indicates how this sense-making quest, in the aftermath of loss, is a key predictor of the person’s adaption to bereavement (Currier et al., Citation2006; Keesee et al., Citation2008; Neimeyer et al., Citation2006). New psychotherapeutic modalities are thus beginning to adapt these principles to clinical practice: moving away from stage theories of grieving, severely criticised in current bereavement research (Corr, Citation1993; Stroebe et al., Citation2017), toward theories (Klass & Steffen, Citation2017) and therapies (Neimeyer, Citation2000, Citation2011, Citation2012) focused on meaning-making and post-traumatic growth.

Shared-life stories, however, often continue evolving after the loss: the literature illustrates how a continuing bond between deceased and mourner is not only common but frequently helpful (Klass & Steffen, Citation2017). An aspect of bereavement that has not been the focus of narrative analysis, so far, are experiences of presence, a term coined by Hayes and Leudar (Citation2016). Other terminologies include “sense of presence” (Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011), “sensory and quasi-sensory experiences of the deceased” (Kamp, Steffen, Alderson-Day et al., Citation2020) and “post-bereavement hallucination” (Rees, Citation1971). They occur when a bereaved person has a sensory perception, or a felt presence, of the person who died, and they are experienced by 30% to 60% of the bereaved (Castelnovo et al., Citation2015). They are frequently reported as the feeling that the person is still around (20–52%), but hearing the deceased (13–45%) or seeing them (14–52%) is common as well (Grimby, Citation1993; Kamp et al., Citation2019; Rees, Citation1971). Other sensory modalities, such as those involving touching them or feeling touched by them, are less frequent (Kamp, Steffen, Alderson-Day et al., Citation2020).

Experiences of presence in context: distress and culture

Experiences of presence are comforting and reassuring for approximately 75% of people who report them, based on existing studies, being ambivalent-to-distressing for approximately 25% (Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2014; Lindström, Citation1995; Rees, Citation1971). These experiences can continue a shared life-story of support and solace (see Sluzki, Citation2008) and are frequently a source of help for the mourner. However, they can also continue a fraught relationship of rejection and abuse after a bereavement (see Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Thomas et al., Citation2004). Despite limited research into unwelcome experiences, studies have identified some sources of distress and ambivalence when experiences of presence go awry. The work of Hayes and Leudar (Citation2016), for example, explored how the experience can be unwelcome due to unfinished issues in the bereaved-department relationship, or to an intensification of the pain of the loss when it takes place (a “feeling of absence”). Rees (Citation1971), on the other hand, identified the presence of a societal stigma or taboo (i.e. the experiencer not disclosing the experience due to a fear of being ignored, judged or ridiculed) in a pioneering investigation conducted in Wales, a finding that has been replicated in some European countries (Kamp, Steffen, Alderson-Day et al., Citation2020). Our own previous work analysed examples of how pre-existing mental health issues can influence the way experiences of presence are felt by the bereaved (Sabucedo, Evans, Gaitanidis et al., Citation2020).

Clinical evidence, albeit limited, suggest that counselling and psychotherapy can be effective in the minority of cases when experiences of presence cause disturbance (Sabucedo, Evans, Gaitanidis et al., Citation2020). There is some evidence to suggest, however, that patient dissatisfaction may be frequent among those seeking professional help (Taylor, Citation2005). Drawing from empirical knowledge in the area, a set of therapeutic guidelines has been recently published to inform clinical practice (see Kamp, Steffen, Alderson-Day et al., Citation2020).

Although not culture-specific, experiences of presence, as personal narratives in general, are embedded within the overarching narratives of a given society, culture and time. These public or ideological narratives (Murray, Citation2003; Somers, Citation1994) provide a shared understanding (or a folk psychologyFootnote2) of how people should be, what can be expected of them, and why they behave the way they do. Each culture shapes grieving with a set of rules determining the way the bereaved should feel, think and behave (Walter, Citation2006, Citation2018), and with a set of resources from which to draw when explaining and communicating their lived experience. In the case of experiences of presence, as we explored in depth elsewhere (see Sabucedo, Evans, & Hayes, Citation2020), ethnographic and cross-cultural research illustrates the complexity of the cultural repertoires influencing whether experiences of presence are seen as fearful, and to be avoided, or as an experience to be actively sought. When experiences of presence are unwelcome, moreover, a socio-cultural pattern can be in place structuring both the way that distress is expressed (e.g. as an illness or possession) and the way that suffering is treated (e.g. through spiritual-religious or ethno-medical rites).

Narrative analysis of experiences of presence

This narrative inquiry is part of a larger project focused on understanding why some experiences of presence become ambivalent-to-distressing for some bereaved people, building upon the aforementioned survey of counselling and psychotherapy practice (Sabucedo, Evans, Gaitanidis et al., Citation2020) and review of cultural research in the area (Sabucedo, Evans, & Hayes, Citation2020). This narrative inquiry focuses on the way that the experiencer narrates their lived experience, and how these stories are told and re-told. Narrative interviewing and analysis were conducted focused on the sources of distress or comfort, regardless of whether they were seen as welcome or unwelcome by the perceiver, as well as the way that they were situated within wider socio-cultural narratives. Our research questions were:

RQ1. What are the sources of distress, ambivalence and comfort reported in participant narratives on their experiences of presence?

RQ2. What is the influence of socio-cultural processes on RQ1, if any?

Method

Recruitment

Recruitment was primarily conducted through counselling and psychotherapy centres, both university research centres and private clinical practices, located in Spain and England. The recruitment poster was included in their waiting room or, alternatively, shared through their mailing list or social media. In addition, an advertisement was published in both a British and a Spanish local newspaper. Recruitment was passive (i.e. waiting for a potential participant to contact the researcher after seeing a poster or ad) in order to ensure people were not coerced or pressured into participating. The dual sampling strategy was aimed to recruit people with unwelcome experiences, perhaps more likely to participate if recruited through a mental health centre, and people with welcome ones, who would see the advertisement in local media. A secondary aim was to create some diversity of country of residence and other socio-demographic variables.

Sociodemographic profile

Inclusion criteria were being over 18, to have suffered a bereavement not more recently than three months before the interview, and to experience (or had experienced) the continued presence of the person they lost via a sensory perception or a felt presence. This latter criterion was communicated in the following way in the recruitment material: “if someone important to you has died, and you have experienced their voice, a vision of them, their touch, or otherwise a sense or feeling that they are still around”. Ten people, four based in England and six based in Spain, chose to participate in the project. Nine identified as female and one as male. Ages ranged from 25 to 92, which seven interviewees being middle-aged (50–70). From the people recruited in the United Kingdom, two identified as British, one as Bulgarian, and one as Franco-American. All of those recruited in Spain identified as Spanish. Regarding their profession, two were retired, two worked in an administrative role, three belonged to the psychology, counselling or psychotherapy profession, one worked as a cleaner, one as a teacher and one was unemployed. Their educational level varied from school diploma to master’s degree.

Data collection

The interviewing procedure followed the biographical narrative guidelines developed by Rosenthal (Citation2003, Citation2018). During the first phase of the interview, dubbed the period of main narration, the interviewer elicited the interviewee’s story focusing on active listening and note-taking. During the second phase, the questioning period, narrative-generating questioning took place around phases and themes within the story, following the same order and wording as in the first phase. Most people were interviewed once, though two people were interviewed twice when they expressed a desire to do so, as per the guidelines of the biographical narrative method (see Rosenthal, Citation2003). Two interviewees added extra information after the interview in the form of a letter or email. The initial question, inspired by the previous work of Hayes and Leudar (Citation2016) and following the work of Rosenthal (Citation2003), was phrased in the following way:

We are interested in the life stories of people who, after losing a loved one, feel (or felt) their continued presence via a voice, a vision, or other sensation. Can you please tell me your personal experience? All the experiences and the events that were important for you. Start wherever you prefer. You have as much time as you like. I won’t ask any questions for now. I will just make some notes on the things that I would like to ask you more about later; if we haven’t got enough time today, perhaps in a second interview.

Data analysis

A narrative methodology was chosen in order to explore the evolution of experiences over time, as well as their complexity and intertwining with the person’s life-story, complementing our previous work using other methodologies (Sabucedo, Evans, & Hayes, Citation2020). By focusing on the sense-making quest at the heart of the grieving process, in the context of the interviewer’s interpersonal and socio-cultural environment, this method allowed for an exploration of how and why some experiences of presence are welcome or unwelcome for a set of interviewees.

Data analysis of the collected narratives was inspired by analytic stages and devices of both Crossley (Citation2008) and Hiles and Cermák (Citation2008). During a first phase (holistic-content perspective), following a comprehensive reading of the data, each participant’s story was summarised as a whole identifying the agent (who), the event (what), the helper (with what or whom), the setting (where), the purpose (why) and the trouble or breach (the imbalance between the previous five). The second phase (holistic-form perspective) involved identifying the narrative progression (or tone) of the story, focusing on the typology of Gergen and Gergen (Citation1986): whether the narrative moves away or toward the achievement of a life goal (regressive and progressive narratives, respectively) or it is stable (stability narratives). The third phase (categorical-content perspective) involved the analysis of the themes that appeared repeatedly in the story as well as the structure and overlap between them. The fourth phase (categorical-form perspective) was focused on the way that the story was re-told to the interviewer: the interviewer-interviewee interaction, the function of the story, and the narrator’s linguistic choices. The analysis was woven into a cohesive story during the fifth phase, attending as well to whether the story was situated within a wider socio-cultural narrative. After each interview had been analysed, a comparative analysis of similarities and differences across the data set (see Wong & Breheny, Citation2018) was performed. Themes, episodes and properties related to sources of distress, ambivalence and comfort, when identified across at least two narratives, were grouped into categories.

Epistemological stance

The focus of this inquiry was on the phenomenology and consequences of these experiences, and not on their reality status for the perceiver. This is grounded on the epistemological stance of the project, philosophical pragmatism and contextualism, from which scientific knowledge is seen as context-dependent instead of objective and absolute (James, Citation2000). This integration of narrative research and philosophical pragmatism can be traced to Sarbin (Citation1986) who, when defending a narrative metaphor in psychology (i.e. the person as a storyteller) instead of a cognitive metaphor (i.e. the mind as a computer), grounded his perspective on the ideas of Pierce, James and Dewey (see Howard, Citation1991; McLeod, Citation2011). The aim of this analysis, therefore, is to provide a tool or map which can be useful in reducing psychological distress, and fostering sense-making, in psychotherapeutic practice. In order to mitigate the effects of the researchers’ premises and worldview, preliminary analyses were discussed with an external data analysis research group to contrast perspectives and integrate alternatives ideas, and reflexive diaries were used to aid in detect issues when present. In concordance with the epistemological stance, however, this analysis should be seen as one among several potential analyses: no analytical procedure can fully account for subjectivity. We wish to remark that the perspective of this work, and psychological science in itself, is but one way of knowing, and that our approach in this report is not an attempt to undermine or undervalue spiritual, mystical or religious perspectives on death and grief.

Ethical approval

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology at the University of Roehamptom. The information obtained was anonymised by deleting all personal information and by and using a pseudonym for each participant. All interviewees joined the project voluntarily giving written informed consent.

Findings

The information presented in summarises the main loss for each participant, the type of loss, and the sensory modality of their experiences of presence. Each interviewee is listed under a pseudonym. With the exception of one interviewee who experienced a recent loss, most of the stories concerned losses happening more than a year before the interview, sometimes decades before. Their stories were primarily focused on the bereavement of a father (5), a mother (2), a brother (2) or a partner (1), but some interviewees also reported an experience involving a friend (2), a grandparent (1) and a mother-in-law (1), as some interviewees suffered multiple losses and reported a variety of experiences. The causes of death, both natural and violent, varied greatly: cancer, heart attack, long-term illness, old age, suicide and car accident.

Table 1. Type of loss, main relationship and sensory modality for the interviewees’ experiences of presence.

The outcomes of the narrative analysis, grouped into categories that highlight similarities and differences across stories, are presented after a brief description of some phenomenological properties of the experiences of presence as narrated by the interviewees. As the full stories, and associated analyses, had to be abbreviated in order to fit into the framework of the paper, the reader is referred to to provide a context from the quotes included in this section.

Basic phenomenological properties

Most interviewees described experiences of presence occurring repeatedly, sometimes daily, during a long period after the person’s death. For a few, experiences spanned more than a decade after their bereavement. By contrast, one participant reported a single experience occurring shortly after the loss. The vividness of the experiences also varied considerably, ranging from the vague impression of seeing the deceased out of the corner of the eye, or quickly walking away in the street, to a clear vision of the person in front of them. Some interviewees reported experiences of presence perceived in full wakefulness during the day. Other people experienced them after waking up, or when in bed, although they reported being conscious and aware when it happened. Four interviewees also reported sensory experiences not explicitly involving the person they lost, but which they clearly associated with them being present (e.g. a sunbeam in the sky). Two interviewees reported auditory or visual experiences that were initially perceived as anonymous, only to become progressively identifiable as, or related to, their loved ones. Most auditory and visual experiences, however, were immediately recognisable by the bereaved as the person they lost.

Sources of distress, ambivalence and comfort

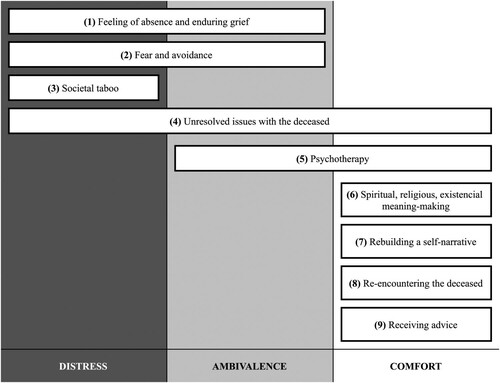

Nine sources of distress, ambivalence and comfort (see ) were identified across the interviewees’ narratives following RQ1 and RQ2: (1) feeling of absence and enduring grief; (2) fear and avoidance; (3) societal stigma or taboo; (4) unresolved issues with the deceased; (5) counselling and psychotherapy; (6) spiritual, religious or existential meaning-making; (7) rebuilding a self-narrative; (8) re-encountering the deceased; and (9) receiving advice. The interviewees’ stories are, of course, unique, with each containing a different combination of these categories, and experiences of presence were not easily classifiable as either comforting or distressing in every case. Ambivalent experiences were common, for example, and the way their experiences of presence were felt by some interviewees changed with time. Sources of comfort were clearly predominant, however, and no source of ambivalence or distress was identified in the stories of three interviewees. Some of these sources refer to immediate properties of the experience (e.g. receiving advice via voice-hearing), a “function” (Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016), while other categories refer to a prolonged period of sense-making using social and cultural resources, such as psychotherapy or religion. The term source as used in this report, therefore, encompasses the personal to the social.

Feeling of absence and enduring grief (source of distress and ambivalence)

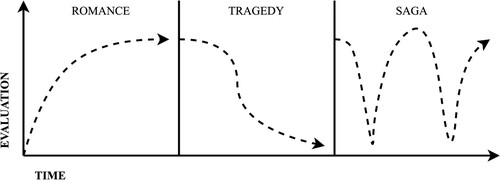

For three interviewees, the distress they felt, or still feel, was connected to their experiences of presence working as a reminder of the loss, or as a “feeling of absence” (Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016): while the experience can be joyous while happening, grief can intensify after, foregrounding the pain of the loss. For the three interviewees, this feeling of absence was part of a grieving process that was narrated as prolonged or never-ending. The narrative progression in all these stories, according to the typology of Gergen and Gergen (Citation1986), was regressive: they were emplotted as a tragedy (see ) with the experiencer moving away from the achievement of their aim or goal following the loss.

Figure 2. Some types of narrative progression according to whether the storyteller is moving away (regression) or toward (progression) the achievement of a goal. Elaborated from Gergen and Gergen (Citation1986).

Rebeca, for example, lost her brother three decades ago, when he had just become an adult. After he did not return from a trip to another Spanish city, Rebeca discovered that he had died in a car accident. They were very close and, after three decades, she does not believe she has “overcome the loss”: she is still distressed by it, feeling “very badly” (65)Footnote3 on a daily basis, and riddled with anger and sadness (p. 262). This is an emotional state she does not want to be in (66) and she does not feel capable of changing (p. 262). Any reminder of her brother (e.g. seeing a picture of him, seeing an old friend of his) is a source of pain for Rebeca, and something she actively tries to avoid. After his death, and for a long time, Rebeca continued seeing him in the street: recognising him for a moment, and moving toward him calling his name, or waving goodbye, before realising that the person was not actually him. After this realisation her grief was intensified. This used to leave her powerless, sad and angry and, since the experience stopped occurring, she was more at ease:

Let’s see, it’s not unpleasant, it’s not for me. But (pause) what I want is to have him here, with me, and I can’t. That is what makes me (deep intake of breath) I say, I mean, no (pause) no, it’s not unpleasant. It’s anguishing, it’s anguish, it’s (pause) of saying: “God, I miss him, I want him to be with me, right? Why did he die in that way?”. It’s that, not (pause) I doesn’t make me (pause) afraid, it doesn’t make me scared, it doesn’t (pause) no. It’s (pause) the anguish of not being able of (pause) touching him and speaking with him. It’s that. (Rebeca, pp. 98–107)

Fear and avoidance (source of distress and ambivalence)

Four interviewees reported having felt afraid of their experiences of presence. For three of them, the experiences were initially frightening because of how unexpected or startling they were, which lead to avoidance behaviour of a place, or situation, which they connected to them. For two of them, this fear was part of a wider fear and avoidance of death in itself.

Initial fright

Lola explained how the initial fright caused by her experiences of presence made her avoid her old family home for a long time. A month or two after the death of her mother, when visiting her old house in order to clean and empty it, she suddenly felt her mother’s hand touching her shoulder. She left the house in a rush, anguished by the experience, and did not return until much after:

We had to clean the house, taking the things out, and so on. Then, the first time, in the area when she had the washing machine, I was talking to one of my aunties, we were cleaning the house together, and I felt how she put her hand (pause) on (long pause) and so, it was the first time in my life, it was a sensation, well, I was very afraid, and for two years, I think, I didn’t enter in my parent’s house. Because it was something (pause) it was that (pause) that hand that I felt that (pause) it was as if she were saying to me: “I am here, don’t worry”. But deep down I was very scared. And because never, ever, something like that had happened to me, the truth is that I was very scared and I didn’t return to the house for a long time. (Lola, pp. 13–25)

As time passed, Lola continued experiencing the presence of her mother, but also the presence of other loved ones who had died, such as her father and her mother-in-law. Progressively, she got used to feeling their presence, which at the time of the interview was both welcome and beneficial for her. She stated that her mother was only trying to reassure her, back then at her old house, and that her anxiety impeded her to understand what she was trying to communicate. When she is in tension or worried, however, her experiences of experience can become frightening again, but only momentarily before she can begin to reflect on it. She established a link, therefore, between the valence of her experiences and her own emotional or arousal state.

It’s normal that they’re there, that they’re helping me and, for whatever reason, in a concrete moment they come to me. That’s the conclusion I’ve reached, okay? Sometimes I feel scared. Because, maybe, it’s one of those times when, for whatever reason, you’re in tension, or you have a bad day or some problem. And then, suddenly, you say: “Uh”. But then you think: “They are helping me”. (Lola, pp. 61–68)

Fear of death

For two interviewees, the distress they felt was part of a wider death anxiety: another reminder of the inevitable death of the people they love and their own. Experiences of presence, therefore, were not singled out in their stories as the core source of distress: they were functionally similar to anything else connected to death, such as a funeral or a cemetery. For both interviewees, this fear could be traced back to the first funeral they attended and the first dead person they saw. Alba, for example, continued seeing a deceased family friend after his passing, but she clarified that it was not the content of the vision that was distressing, but rather it working as a reminder of his demise:

When that man died, I got much worse. Because after I had issues with (with) fear many times. Many. But sense of presence, and so on, only those two. But neither of them was (pause) frightening, okay? Fear to death in general, yes, but not fear. […] I was afraid of the fact that he was dead rather than the vision of him. Because he didn’t seem threatening nor (pause) nor unpleasant. (Alba, pp. 195–207)

The way she avoided anything related to the deceased person, such as the place where he used to live or where the person was buried, is similar to the experience of Rosa, who is incapable of attending a funeral. Seeing a ceremony in the cemetery is, for her, almost a flashback to the funeral of the people she lost. This is especially the case regarding her father’s death, and an event during his funeral that remained stuck with her: giving him a last kiss and noticing how his body was cold.

With this woman I don’t have (pause) I didn’t have much of a connection. But (when) when I went there, and I saw (pause) with him we had a closer relationship, and so on, and I saw him fully dressed in black […] But his tears were falling. He was, but, like frozen, okay? Still. Completely still. And I, could see that, and then I saw myself in the same situation, you know? And then I began living it as my own: horrible. I began seeing my grandmother, I began seeing my father, I began seeing my husband, and my mother, and my son, everything. And I went crazy: I lost my nerves […] But that woman wasn’t (pause) so important for me, you know? That is what I think it is, that in those places, in those cases, I see my own stuff. I don’t see that: I see my own. So I can’t go to, I can’t to any funeral. (Rosa, pp. 188–209)

Societal stigma or taboo (source of distress)

Stigma around experiences of presence (a fear of rejection, judgment or ridicule)was an issue, in one form or another, in the stories of five interviewees in both Spain and the United Kingdom. Henry, for example, a mental health professional himself, was “very, very cautious” (p. 638) about who he told about his experiences, keeping them private out of a concern about the way he believes they are conceptualised in psychiatry:

If I talk about this people are going to think I’m crazy. So I kind of just left it, and I just kind of compartmentalised it. (Henry, pp. 320–322)

A similar concern was expressed by Lola: she refused to tell other people about her experiences of presence out of a fear of being considered insane (“there are things you don’t tell anyone”, pp. 227–228). She only told her husband, who reacted worrying about her mental health, and her therapist, who accepted her experience without judgment. She stated:

There are people that if you say to them that you are speaking with my mother, with my father, with their mother, or with their father, then they would say: “She is gone mad”. (Lola, pp. 215–228)

Lola also found comfort in an article she read in a Spanish magazine, which stated that experiences of presence are common and normal in bereavement. This piece of information, and the beneficial outcomes of her psychotherapy process, seemingly influenced the openness and ease with which she narrated her story to the interviewer.

Unresolved issues with the deceased (source distress, ambivalence and comfort)

Significant unfinished business in the bereaved-departed relationship were present in the stories of four interviewees but, with the exception of one participant, this also meant an opportunity to recognise them, to understand them, and to mitigate some of their psychological and interpersonal consequences.

For Henry, the continued presence of his father was apparently instrumental in both unearthing a family secret and resolving a pending issue. He had a recurring dream of his father, following his loss, who seemed to be physically unable to speak to him, and Henry had “the overwhelming feeling” (p. 167) that was trying to tell him something. This made him reflect on the last conversation he had with his father and, asking the extended family about his father’s past, Henry discovered that his father had kept his homosexuality a secret during all his life. Shortly after that, while having dinner in the house of a friend, Henry had a vision of his father sitting next to him:

I (I) was sitting eating my meal and I can remember sort of turning round and (and) doing a double-take because they’d got an armchair and I could see my father sitting in this, in the armchair. And I thought well that’s (that’s) bloody ridiculous! And I looked again and he smiled at me! And I, he was, he looked well, (uh) familiar, he was wearing sort of familiar clothes and a like tweed jacket and he (he) was never a particularly smart looking man, he was always, he was kind of scruffy. (Um) But he had a smile on his face. (Henry, pp. 243–252)

Henry then felt “an incredibly powerful sense of acceptance and love” (p. 276), a two-way connection with his father, and cried “joyful tears” (p. 284) after what he described as the “most moving experience” (p. 287) he had ever had. This double-edge sword nature is relevant for the clinician to be aware of: pending issues with the deceased can be a source of distress, but also an opportunity for resolution and sense-making under some circumstances.

Counselling and psychotherapy (source of comfort and ambivalence)

Five out of 10 interviewees discussed their experiences of experience with a mental health professional (e.g. a psychologist, analyst or counsellor) during a counselling or psychotherapy process, and all of them were satisfied with the outcome. They seemed to find a therapist who accepted their experiences in a non-judgmental way and, if needed, an opportunity to explore the meaning they placed on them. Some disclosed unwelcome experiences in the therapy room, whilst other interviewees narrated comforting or beneficial experiences without wanting to change, solve or explore anything about them. Clara, a Franco-American woman in her twenties, described how a decade-long psychotherapeutic process helped her to make sense of the loss of her father during her adolescence, the effect this had on her, and his continued presence in her life.

Yes, so I saw a therapist. I started seeing her when I was (pause) thirteen? So right after my father died. And then I kept seeing her until, like I was twenty-five, you know, until earlier this year. Like, I’ve seen her for twelve fucking years, you know? I haven’t seen her in a while. Now I am seeing someone else. But (pause) yeah. So she really (really) helped me to (eh), you know, sort of understanding that, and put my finger on it. (Clara, pp. 515–671)

An exception to this trend is the case of Gergana, a psychologist herself. On the one hand, the personal therapy she received helped her to resolve the guilt and confusion she felt after her mother’s suicide. On the other hand, she struggled with how her clinical supervisor reacted to her experiences of presence, explaining them away as a by-product of tiredness and shock. This interpretation was shared by other people in her life, and she felt that they did not empathise or recognise the meaning she placed on her experiences of presence. The emphasis her supervisor placed on the grieving stages, and on tackling these experiences with cognitive restructuring, did not seem to help in her recovery nor correspond to her situation at the time.

It’s (it’s) difficult to say to other people and other people immediately say “oh yes, don’t worry it’s (it’s) normal” but in a sense that almost a little bit diminishing. Almost saying that (sniffs) don’t worry that’s all what the mourning people do. Don’t worry that’s (that’s) (pause) yeah, I find it really not nice (laughs)[…][My clinical supervisor] said that (that, that) it’s (it’s) also normal and that I should (uh) rationalise it (pause) and that I have (I have) such a shock that (sniffs) that my mind is playing tricks on me (pause). And I should CBT it. You know. I should CBT it and well he was compassionate (he was compassionate) (pause) (uh) but (pause) but (but) he walked me through, it was more of a conventional (um) crisis management at the beginning that, he walked me through the stages, something that I knew also but (um) I think at certain points I experienced all the stages, mix of all the stages at the same time (pause). (Gergana, pp. 829–869)

Spiritual, religious or existential meaning-making (source of comfort)

For eight interviewees, their experiences of presence provided them with the hope, and reassurance, of believing that their loved ones are not completely gone. Regardless of whether they framed this belief from a religious perspective, or from a secular one, all of them felt comforted by it.

For four of them, this meaning-making process took place within their Catholic faith, their sole or primary religious worldview, and their belief in an afterlife. One interviewee compared the experience of talking to her deceased mother to the relief following confessing with a priest. Interestingly, however, none of them had told their experiences to a priest in conversation or confession. The interviewees did not provide an explicit reason for this, although one participant suggested that this would not be well received in her parish.

For Gloria, a Spanish Catholic widow in her nineties, feeling the presence of her deceased husband (“he is with me, he is (eh) in every moment I make”, p. 116) is a confirmation that they will meet again in Heaven: that their shared life-story, therefore, is not over. She narrated that he is interceding for her: protecting her from danger until her time is come. Feeling waited for, and taken care of, she lives in expectation of her afterlife “up there” (p. 216). Her daily morning prayer is to both Jesus and to her husband, and she is convinced of their help, as “the peace I feel, the peace (eh) I cannot achieve it alone. I am convinced of it, okay? That is true” (pp. 374–375). Her meaning-making was strictly situated within the religious sanctioning of her faith: in contrast to “credulous” (p. 124) people, presented herself as not communicating directly with her husband, or receiving direct help from him, but that only from Heaven and through God they can “give me a hand” (p. 127):

I simply ask for help when I wake up, as to the being (pause) as to the superior being I was taught to believe, and then within Him everything else is included. All of them are (unintelligible) there, and I always say to them: help me. (Gloria, pp. 17–21)

For another four interviewees, this meaning-making process took place using a metaphysical or existential worldview, and was not necessarily connected to a belief in an afterlife: a perspective, therefore, not aligned to, or identifiable with, a specific religion. They carefully switched in their stories between materialistic and metaphysical discourses: returning to the former repeatedly during the interview, maybe due to a fear of judgment, and expressing the latter on occasion in the form of a rhetorical question. Henry, who identified himself as a scientist, stated “not being afraid of death after the experience” (p. 472) of seeing his deceased father, and decried being seen as credulous by other people, or irrational, because of his lived experience:

The assumption is, because I’ve had an experience like that, that people think that I will believe anything and I don’t. I’m (I’m), I am a scientist (laughs) […] And (I) but I know that I (pause) I can’t (I can’t) tell you what’s real and what isn’t real. It, I can only tell you what my experience was. But I can’t make you have that experience. So you can’t verify it. And I accept that. I’m quite happy with that. (Henry, pp. 451–463)

For Rebeca, her sense-making provided her with a partial rationale for the visual experiences of her deceased brother, in which she would briefly recognise him walking down the street before realising it was not him. The organ donation following his death meant, for her, that part of him was still alive. And because his heart was still beating inside another person’s body, she argued, that person would have to be “as good as he was” (pp. 49–50). Maybe, she argued, when seeing her brother she was actually seeing the recipient of her brother’s heart: a physical overlap explaining her sensory overlap.

My parents donated his organs. So, maybe that person, is the one that had his heart. Or his liver, or his kidney. Well, probably the heart. That is what (pause) what makes you (pause) live? Well, the kidney and the liver and (pause) everything else, as well. But, well, the heart is the heart. Is where you have, well, in theory, feelings, the (pause) everything else. So (pause) well, he, well, I don’t believe that now, because I don’t think that can last (last) a heart for so long (pause) after being transplanted. But, well, he still lived those (pause) I mean, during X years, he was (pause) for me, for me, he was alive. Because his heart, his heart was beating inside somebody else. And that person had to be as good as he was. That is what (pause) what gives me (pause) a bit more of (pause) I mean, well, he didn’t die at that moment. He continued living. (Rebeca, pp. 137–152)

Re-building a self-narrative (source of comfort)

For five interviewees, their experiences of presence seemed helpful in re-constructing their self-narratives after the loss. The experiences answered a pending question, for example, or provided them with a clearer understanding of what had happened. Attending to the narrative progression of these five stories, this sense-making quest was in each case present within a progressive emplotment, following the typology of Gergen and Gergen (Citation1986): a self-story of affirmation (see ).

The clearest example of this is the story of Henry that, as we have seen, was centred around the discovery of a family secret: his father’s homosexuality. His experiences of presence seemed to provide him with the missing piece he needed in order to understand his childhood experiences: the nature of their parents’ marriage, and the pain they endured surrounded by the homophobia that was rampant at the time, but also the way this shaped his relationship with them, and his own personality, when growing up. This amended self-narrative was seemingly essential in making possible a reconciliation with his mother, making Henry’s story an example on how an experience of presence can lead to the healing of a relationship with a person other than the deceased. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first time that such a case has been reported in the literature:

It was always that kind of, it always felt conditional and (and) she would often (pause) she was schizophrenogenic from that Batesonian kind of point of view, in that she would often say one thing and do something different. So I was often in this state of upset because (because) I just didn’t know. So, you know, (um) so it was a tricky relationship that I had with her. After (pause) we’d had this (this) conversation about what she’d been through (pause) and she didn’t have to keep secrets from me anymore it (it) just opened up the possibilities for our relationship to be more real, more honest (um) and over (over) years we we’ve, I would now say, I mean she’s (she’s) ninety, and she’s dying herself (um), I would say that we’re friends. (Henry, pp. 507–520)

Another example of this re-building of a self-narrative is the story of Clara who, as was previously described, lost her father in her adolescence. Clara was clear on how she was still “piecing this [story] together” (p. 23) but that, with help from a decade of therapy and from her father’s felt presence, she was able to understand what happened in the past and the way this shaped her growing up. After his death, and during her therapeutic process, Clara discovered that his father was a war veteran who suffered from complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Feeling his presence was seemingly a way for her to bridge the “big disconnect” (p. 42) she felt with him when he was alive, despite how close they were:

I would still (pause) have (hum) these times when, you know, I was alone in my bed, or it was late at night, and I maybe I was like scared, or I heard a noise, or something, and I’d feel like: “Okay, my dad is with me”. You know. And that just would really (really) calm me down. So that’s the thing, it’s that (hum) I think that a lot of what I was feeling was also born out of desperation and was it was like a desperate way to connect with my dad, as well, especially because he was so ill. And there was always a disconnect when he was alive (hum). (Clara, pp. 49–59)

The loss of her father seemed incomprehensible during her adolescence, but now her father is an integral part of who she is, “part of my core […] part of my being” (p. 272). She can now understand what he went through, how his post-traumatic stress disorder influenced his family and their relationship, and the way that intergenerational traumaFootnote4 shaped who she is.

Re-encountering the deceased (source of comfort)

Several interviewees rejoiced at the opportunity to feel the presence of their deceased loved ones after their passing, whether this was a chance for them to say goodbye, to express their love, or simply to be with them. For two interviewees, their experiences of presence meant that the deceased kept a promise that was made before their death: to return to say they are well. In the stories of most interviewees, the experiences were something that happened to them: something over which they had no control. This was not the case for two of them, who described being able to evoke or provoke the feeling, at will, and feel reassured by it. The clearest example of this was Clara, who began feeling the presence of his father during her adolescence as a sudden feeling that would happen at night. Progressively, as she grew up, this felt presence became something she could evoke at will by focusing on the sensation. This is especially the case in natural spaces when she can feel his closeness: by the sea or a mountain area, places he used to love, but also a village abroad where he lived for a while. Another way she can evoke him is through reading a hand-written diary that she inherited from him:

Another way that I could evoke him with be reading the things that he wrote, you know. That would be a way for me to feel that he, he is close to me. So he had this notebook that he would write on, that it was kind of like a journal-slash-quote thing, he would just write in that (pause) and I remember him telling me, once, he was like: “When I die, I want you to have this”. And, so, anytime I would read it I would just, like, instantly feel (pause) that he was right there (um) because it was just visceral, you know: “This is my dad, like, it’s just, this is my papa”. (Clara, pp. 844–854)

Receiving advice (source of comfort)

Three interviewees not only felt supported by feeling the presence of their deceased loved one, but they also believed they were explicitly advising and guiding them. They could receive explicit advice (e.g. through hearing their voice) or they could also feel they were being implicitly guided (e.g. feeling their thinking influenced by them). For all of them, this guiding role was seemingly the continuation of the way the deceased person used to behave when alive: a continued support when facing a danger, for example, or a confidante to rely on in difficult times. Gergana, for example, narrated feeling empowered by the continued presence of her mother:

If I’m in a difficult situation, I also have the feeling that mother is, that my mum is around me and telling me what to do. (Gergana, pp. 340–342)

She perceives this advice through a felt presence, but also through hearing her voice “in my mind” (p. 618). When organising her mother’s funeral, for example, she heard her mother’s voice telling her to choose a closed coffin for the ceremony. This gave Gergana the strength she needed to oppose a strong norm in her country: the use of the open coffin. Then, she heard her mother’s voice again congratulating her for the decision:

And then I (I) heard my mother but not with voice (pause) I just (pause) (sniffs) hear my mother telling me in my mind “it was such a good decision”, like “bravo, it was good, it was good that you did not (uh) want to see me in such state.” (Gergana, pp. 624–628)

Discussion

The aim of this narrative analysis was to obtain an in-depth understanding of what makes experiences of presence distressing, ambivalent or comforting for a small set of interviewees. From the nine categories identified in the interviewees’ narratives, most of them and the most frequent (i.e. re-building a self-narrative, re-encountering the deceased, meaning-making, psychotherapy and receiving advice) were sources of comfort exclusively or primarily, a finding that matches existing evidence on how experiences of presence are mainly welcome for the bereaved (Kamp, Steffen, Alderson-Day et al., Citation2020; Kamp, Steffen, Moskowitz et al., Citation2020). Three were clear sources of distress, ambivalence, or both (i.e. fear and avoidance, feeling of absence and enduring grief, and societal taboo). These analytical outcomes have replicated several processes that have been previously reported in the literature, as summarised in .

Table 2. Sources of distress, ambivalence and comfort identified in participant narratives, and their connection to the existing research evidence.

Two properties are reported here for the first time: the potential role of fear and avoidance, concerning either the experience in itself or death as a whole, as well as the control that the experiencer may feel over felt presences. Although these sources of distress and comfort are new concerning experiences of presence, they are concordant with the available evidence on voice-hearing, in particular how experiential avoidance of voices (i.e. attempting to avoid, ignore or supress them) and subordinate relating with them (i.e. to voices seen as in control or in power) is linked to psychological distress (Birchwood et al., Citation2000; Morris et al., Citation2014).

These narratives have nuanced our existing understanding of the consequences of experiences of presence, such as the double-edged nature of unfinished business with the deceased. They have also highlighted the complexity of cultural repertoires, and the interpersonal context, from which their meaning is constructed. The discussion will now focus on the roles of narrative reconstruction and psychotherapeutic practice.

Narrative progression and meaning-making

When attending to the narrative emplotment of the interviewees’ stories, experiences of presence were instrumental in the amendment of self-narratives after the loss. Ambivalent-to-distressing experiences were, in each case, identified when the narrative plot of the grief was regressive, such as when the experiencer felt trapped in a grieving process seen as never-ending or meaningless. When the narrative structure was progressive, for other interviewees, experiences of presence were frequently helpful for the bereaved in making sense of the loss and continuing a shared life-story (or bond) with the deceased. This narrative analytical approach, in sum, has highlighted the role of the experiences of presence in the grieving process over time. These outcomes resonate with the existing evidence on the centrality of meaning-making in grief (Currier et al., Citation2006; Keesee et al., Citation2008; Neimeyer et al., Citation2006), and are of clinical relevance to those using grief psychotherapies (and especially narrative and meaning-oriented modalities) in the presence of traumatic or complex bereavement, as is further explored in the following sub-section on psychotherapeutic practice.

Strengths and limitations of the research design

The cross-cultural design allowed for variation regarding ethnicity, age, language and religiosity, as well as for the sensory modality of the experiences and the type of loss they were connected to. The extent to which these outcomes are transferable to another cultural context, or societal group, is however uncertain. This qualitative design is not aimed at generalisability nor objectivity: data collection, for example, was influenced by the interviewee-interviewer interaction as well as by the participant’s recall and disposition. The recruitment method, primarily based in counselling and psychotherapy centres, may have also biased the sample toward those satisfied with the psychological care they received, and more prone to draw resources from mental health sciences.

Counselling and psychotherapy practice with experiences of presence

The recruitment bias may explain the discrepancies with the work of Taylor (Citation2005). In opposition to her interview-based research, in which eight out of 10 interviewees reported dissatisfaction with their counsellor due to their non-accepting and deflecting responses, each of the five interviewees who participated in this project, and received therapy, described the process as largely helpful in their grieving process. The interviewees described in this report chose to participate in order to narrate their experiences of presence, without being asked or prompted about their experiences with counselling or psychotherapy unless they raised the topic. Taylor, on the other hand, interviewed people who received bereavement counselling in the past and were willing to discuss it with the researcher during an interview, a method of recruitment which may be more likely to recruit those discontented or frustrated with the psychological care they received. Again we stress the need to avoid generalisation: both studies are based on small samples in only two countries.

Nevertheless, the experience of one interviewee indicated the iatrogenic processes reported by Taylor, when she felt her experiences were “explained away” in the therapy room: counselling or psychotherapy becoming a source of ambivalence in itself. More than one therapist in our recent survey (Sabucedo, Evans, & Hayes, Citation2020), moreover, connected experiences of presence with the same blockage according to the grieving stages theories (i.e. a denial of reality due to impossibility to “let go” and “move on”) that Taylor’s interviewees found unhelpful, and this interviewee found unsatisfactory too. Most experiences, in fact, not only do not require psychological care, but may be beneficial in the grieving process. Considering the importance of interpersonal processes in the minority of experiences that go awry, causing worry or distress, the clinician’s normalisation should be ideally guided by acceptance, curiosity and empathy toward the person’s experience.

Conclusion

We hope that this analysis can be of use to those working with experiences of presence in their professional practice, adding to previous work on common sources of distress, and solace, in the continued presence of the deceased. We look forward to future research continuing to address the way that experiences of presence, inside and outside the therapy room, are made sense of in light of both the person’s biography and an ever-changing cultural landscape.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the 10 people who, volunteering their time, energy and insight, allowed us to use their stories for the purpose of this study. We are also thankful to Dr Edith Steffen, Senior Lecturer at the University of Roehampton in London, and Dr Anne Austad, Associate Professor at the VID Specialized University in Norway, for the inspiring debates that helped to shape some of the ideas presented in this report. Authors’ contribution: The first author, PS, co-devised the research design, conducted the interviewing and the analysis, and led the writing of the manuscript. The second author, JH, designed and supervised the project, co-devised the research design, contributed to the qualitative analysis, and helped with the write-up of the report. The last author, CE, co-devised the research design, and project, and contributed to the write-up of the report.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The transcript data analysed in this paper is not freely available in order to protect the interviewees’ privacy, in concordance with the informed consent given by them.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pablo Sabucedo

Pablo Sabucedo is a chartered clinical psychologist in private practice and an honorary lecturer at the School of Psychology of the University of Liverpool, UK. He completed his MSc and PhD in Clinical Psychology at Leiden University, Holland, and at the University of Roehampton,UK, respectively. His research interest lies in the relationship between culture, mental health and psychotherapy, especially in cases of clinical and non-clinical hallucinatory experiences.

Jacqueline Hayes

Jacqueline Hayes is a senior lecturer in Counselling Psychology at the University of Roehampton, UK. She completed a PhD at the University of Manchester which examined the accounts of bereaved persons who had experienced the presence of the deceased. Her primary interest is in the phenomenal and pragmatic qualities of the experiences and their situatedness in the ordinary lives of the bereaved, including their relational histories.

Chris Evans

Chris Evans is a clinically retired medical psychotherapist and visiting professor in the Department of Psychology of the University of Sheffield, UK. He trained in individual and group dynamic psychotherapy and systemic psychotherapy and worked in the National Health Service (NHS) from 1984 to 2016. He is a co-developer of the CORE (Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation) system (www.coresystemtrust.org.uk) and has published widely. His research interest has always been in how it is that we think we know what we think we know, but particularly what it is we think we know about the changes people achieve in psychotherapy.

Notes

1 Emplotment is the way in which a narrative is put together through a series of plots and subplots linking the story’s beginning with the story’s end (Howitt, Citation2013). Through emplotment we attribute agency to each character, and we infer causality between occurrences, thus understanding why a person acted in a specific way (Polkinghorne, Citation1988), but also imbuing daily life with coherent meaning.

2 Bruner (Citation1990, p. 35) defined folk psychology as “a set of more or less connected, more or less normative descriptions about how human beings ‘tick’, what our own and other minds are like, what one can expect situated action to be like, what are possible modes of life, how one commits oneself to them, and so on”. Narratives are only created and needed, he argued, when this worldview is breached.

3 The number after each quote is a reference to the line number in the verbatim transcript.

4 Intergenerational or transgenerational trauma is a term describing the transmission of complex post-traumatic symptomatology from survivor to offspring (Pearrow & Cosgrove, Citation2009).

References

- Austad, A. (2014). ‘Passing way, passing by’: A qualitative study of experiences and meaning making of post death presence [Unpublished doctoral thesis, MF Norwegian School of Theology].

- Bennett, G., & Bennett, K. M. (2000). The presence of the dead: An empirical study. Mortality, 5(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/713686002

- Birchwood, M., Meaden, A., Trower, P., Gilbert, P., & Plaistow, J. (2000). The power and omnipotence of voices: Subordination and entrapment by voices and significant others. Psychological Medicine, 30(2), 337–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799001828

- Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

- Castelnovo, A., Cavalloti, S., Gambini, O., & D’Agostino, A. (2015). Post-bereavement hallucinatory experiences: A critical overview of population and clinical studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 186, 266–274. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.032

- Corr, C. A. (1993). Coping with dying: Lessons we should and should not learn from the work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. Death Studies, 17(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481189308252605

- Crossley, M. (2008). Narrative analysis. In E. Lyings, & A. Coyle (Eds.), Analyzing qualitative data in psychology (pp. 131–144). Sage.

- Currier, J., Holland, J. M., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2006). Sense-making, grief and the experience of violent loss: Toward a mediational model. Death Studies, 30(5), 403–428. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600614351

- Gergen, K. J., & Gergen, M. M. (1986). Narrative form and the construction of psychological science. In T. R. Sarbin (Ed.), Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct (pp. 22–44). Praeger.

- Grimby, A. (1993). Bereavement among elderly people: Grief reactions, post-bereavement hallucinations and quality of life. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 87(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03332.x

- Hayes, J. (2011). Experiencing the presence of the deceased: Symptoms, spirits, or ordinary life? [Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Manchester].

- Hayes, J., & Leudar, I. (2016). Experiences of continued presence: On the practical consequences of ‘hallucinations’ in bereavement. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(2), 194–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12067

- Hayes, J., & Steffen, E. (2017). Working with welcome and unwelcome presence in grief. In D. Kass, & E. Steffen (Eds.), Continuing bonds in bereavement (pp. 163–174). Routledge.

- Hiles, D., & Cermák, I. (2008). Narrative psychology. In C. Willig, & W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 147–164). Sage.

- Howard, G. S. (1991). Culture tales: A narrative approach to thinking, cross-cultural psychology, and psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 46(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.3.187

- Howitt, D. (2013). Narrative analysis. In Introduction to qualitative methods in psychology (pp. 362–388). Harlow: Pearson.

- Jahn, D. R., & Spencer-Thomas, S. (2014). Continuing bonds through after-death spiritual experience in individuals bereaved by suicide. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 16(4), 311–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19349637.2015.957612

- James, W. (2000). Pragmatism and other writings. Penguin.

- Kamp, K. S., O’Connor, M., Spindler, H., & Moskowitz, A. (2019). Bereavement hallucinations after the loss of a spouse: Associations with psychopathological measures, personality and coping style. Death Studies, 43(4), 260–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1458759

- Kamp, K. S., Steffen, E. M., Alderson-Day, B., Allen, P., Austad, A., Hayes, J., Larøi, F., Ratcliffe, M., & Sabucedo, P. (2020). Sensory and quasi-sensory experiences of the deceased in bereavement: Interdisciplinary and integrative review. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(6), 1367–1381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa113

- Kamp, K. S., Steffen, E. M., Moskowitz, A., & Spindler, H. (2020). Sensory experiences of one’s deceased spouse in older adults: An analysis of predisposing factors. Aging and Mental Health, Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1839865

- Keesee, N. J., Currier, J. M., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2008). Predictors of grief following the death of one’s child: The contribution of finding meaning. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(10), 1145–1163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20502

- Klass, D., & Steffen, E. (2017). Continuing bonds in bereavement. Routledge.

- Lindström, T. C. (1995). Experiencing the presence of the dead: Discrepancies in the ‘sensing experience’ and their psychological concomitants. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 31(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/FRWJ-U2WM-V689-H30K

- McLeod, J. (2011). Qualitative research in counselling and psychotherapy. Sage.

- Morris, E. M. J., Garety, P., & Peters, E. M. (2014). Psychological flexibility and nonjudgemental acceptance in voice hearers: Relationships with omnipotence and distress. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(12), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1839865

- Murray, M. (2003). Narrative psychology. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 111–131). Sage.

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2000). Searching for the meaning of meaning: Grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Studies, 24(6), 541–558. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180050121480

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2011). Reconstructing meaning in bereavement: Summary of a research program. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 28(4), 421–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2011000400002

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2012). Techniques of grief therapy: Creative practices for counseling the bereaved. Routledge.

- Neimeyer, R. A., Baldwin, S. C., & Gillies, J. (2006). Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Studies, 30(8), 715–738. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600848322

- Pearrow, M., & Cosgrove, L. (2009). The aftermath of combat-related PTSD: Toward an understanding of transgenerational trauma. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 30(2), 77–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740108328227

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. State University of New York Press.

- Rees, D. W. (1971). The hallucinations of widowhood. British Medical Journal, 4(5778), 37–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5778.37

- Rosenthal, G. (2003). Biographical research. In S. Clive, C. Gobo, J.F. Gubrium & D. Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp. 48–65). London: Sage.

- Rosenthal, G. (2018). Interpretive social research. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press.

- Sabucedo, P., Evans, C., Gaitanidis, A., & Hayes, J. (2020). When experiences of presence go awry: A survey on psychotherapy practice with the ambivalentto-distressing ‘hallucination’ of the deceased. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94(S2), 464–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12285

- Sabucedo, P., Evans, C., & Hayes, J. (2020). Perceiving those who are gone: Cultural research on post-bereavement perception or hallucination of the deceased. Transcultural Psychiatry. Advanced Online Publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520962887

- Sarbin, T. (1986). The narrative as a root metaphor for psychology. In Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct (pp. 3–21). Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Sluzki, C. E. (2008). Saudades at the edge of the self and the merits of ‘portable families’. Transcultural Psychiatry, 45(3), 379–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461508094672

- Somers, M. R. (1994). The narrative constitution of identity: A relational and network approach. Theory and Society, 23(5), 605–649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992905

- Steffen, E., & Coyle, A. (2011). Sense of presence and meaning-making in bereavement: A narrative analysis. Death Studies, 35(7), 579–609. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.584758

- Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Boerner, K. (2017). Cautioning health-care professionals: Bereaved persons are misguided through the stages of grief. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 74(4), 455–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222817691870

- Taylor, S. F. (2005). Between the idea and the reality: A study of the counselling experiences of bereaved people who sense the presence of the deceased. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 5(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140512331343921

- Thomas, P., Bracken, P., & Leudar, I. (2004). Hearing voices: A phenomenological-hermeneutic approach. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 9(1-2), 13–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13546800344000138

- Walter, T. (2006). What is complicated grief? A social constructionist perspective. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 52(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/3LX7-C0CL-MNWR-JKKQ

- Walter, T. (2018). How continuing bonds have been framed across millennia. In D. Klass, & E. M. Steffen (Eds.), Continuing bonds in bereavement (pp. 43–55). Routledge.

- Wong, G., & Breheny, M. (2018). Narrative analysis in health psychology: A guide for analysis. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 6(1), 245–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2018.1515017