ABSTRACT

UK depression prevalence is increasing. In this study we appraised the relationships between psychological factors of derailment, self-criticism, self-reassurance and depression, to identify individual differences within the UK general population indicating those at higher risk. Participants completed self-report measures regarding these constructs. Relationships were assessed using correlation and path analyses. Derailment and self-criticism predicted depression positively, whereas self-reassurance predicted depression negatively. Self-criticism mediated derailment’s relation to depression. Self-reassurance moderated derailment’s relation to depression, with low self-reassurance indicating greater depression, though self-reassurance was not found to moderate the effect of derailment-associated self-criticism on depression. In depression treatment therefore derailment should be considered as a target factor to be reduced, since derailment indicates a risk of depression for individuals with high self-criticism or low self-reassurance. .

Introduction

The prevalence of depression continues to rise (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2017), posing a significant challenge to contemporary societies throughout the world (WHO, Citation2012), exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Ogueji et al., Citation2021). In the UK alone, mental health costs the economy an estimated 106 billion Euro annually (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development/European Union, Citation2018), with depression contributing approximately 10% of this total (Department of Health, Citation2011). Empirical findings regarding psychological factors affecting the etiology and treatment of depression are needed to extend contemporary research in other scientific disciplines (Cruwys et al., Citation2014). It is the purpose of this study to ascertain the extent to which psychological factors of derailment, self-criticism, and self-reassurance may indicate those at risk of depression in the UK general population, and to suggest further research for effectively targeting treatment.

Identity development as a risk factor for depression

During the life course a person’s identity forms and undergoes changes that have a direct relation to mental health (Beck & Alford, Citation2009; Erikson, Citation1977). Empirical research informed by Erikson’s psychoanalytic theory, in which identity is continually undergoing development (Erikson & Erikson, Citation1997), consistently provides evidence that failures of identity consolidation can contribute to mental health problems (Marcia, Citation1966; McLean, Citation2008; Waterman et al., Citation1974). Contemporary theories of narrative identity propose that mental health issues arise where a person is unable to derive a sense of meaning and continuity from their life story (Adler et al., Citation2015; McAdams & McLean, Citation2013). A sense of self-continuity and self-consistency through time have particularly been linked to mental health outcomes (Campbell et al., Citation1996), with individuals scoring low on measures of these attributes evincing higher depression levels (Campbell et al., Citation2003). The impact of identity discontinuity on psychological wellbeing is pronounced in Western populations (Suh, Citation2002) in which self-continuity has been shown to be more dependent upon narratives than in non-Western populations owing to individualist versus collectivist cultural influence (Sedikides et al., Citation2018). As such, self-perceived identity change is proposed to be a salient risk factor for depression in the UK population, in line with previous findings (Sedikides et al., Citation2016).

Derailment as an appropriate measure of self-perceived identity change

Burrow et al. (Citation2020) have developed a quantitative measure, which accesses self-perceived identity change in a manner more phenomenologically relevant to the individual’s experience than previous measures of subjective identity change, and is capable of single administration to large samples; this latter being an efficient means to identify individuals at risk of depression in research and clinical settings (Burrow et al., Citation2020). Arguing that the construct Burrow et al. posit is unique within the literature, these researchers assign the term derailment to denote a self-perceived disconnection of present and past identity, a “failure to sense sufficient stability or personal sameness over time” (Citation2020, p. 4). Derailment has been found to correlate with and predict depression independently of alternative identity change measures and personality traits in a number of samples in the USA (Burrow et al., Citation2020; Ratner et al., Citation2019). Recent evidence of cultural differences in derailment between North America and East Asia has been demonstrated, with Japanese samples showing less derailment and consequent mental health impact (Chishima & Nagamine, Citation2021). Although North American and UK populations are comparable on many psychological constructs, cultural differences have been found that demand investigation of derailment’s validity in the UK: Long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance for example, two dimensions in Hofstede’s (Hofstede et al., Citation2010) international cultural comparison index, are shown to be significantly different between the USA and UK (Hofstede et al., Citation2010), indicating cultural differences relevant to the individual’s perceptions of stability and change (Bearden et al., Citation2006; Beugelsdijk & Welzel, Citation2018). To date, no application of the derailment scale to a UK sample has been published. It is therefore an aim of the present study to provide initial validity data for the derailment scale in the UK whilst determining its utility as a predictor of depression risk for this population.

Psychological factors influencing derailment’s relation to depression

Evidence suggests self-perceived identity change has a negative impact on mental health whether resulting from positively or negatively viewed life events (Carter & Marony, Citation2021; Keyes, Citation2000; Keyes & Ryff, Citation2000). Such findings indicate psychological processes or interactions operating to dispose the individual to a negative self-evaluation when perceiving instability of the self over time based on various motivations or standards (Sedikides & Strube, Citation1997). Becker et al. (Citation2018) found individualist vs. collectivist cultural personhood beliefs play a role in this, with individualist cultures, such as the UK, depending more on narrative accounts for temporal change of self (Sedikides et al., Citation2018); however, this comparison between cultures does not address individual differences within a culture, necessary for risk identification in the UK. Although Burrow et al. (Citation2020) explored a range of potential psychological traits as buffers between derailment and depression none have yet been identified. It is proposed in the present study that identification of interaction effects of psychological factors influencing the relation between derailment and depression will provide valuable insight into individual risk factors for depression in the UK and give initial direction to a search for effective treatment for depression as related to derailment.

Derailment, depression, and compassion focused therapy constructs

One research area producing much evidence of psychological risk factors for depression as related to modes of self-relating is that of compassion focused therapy (CFT; Gilbert, Citation2014; Kirby & Gilbert, Citation2019). Based upon a neurophysiological and evolutionary approach, Gilbert (Citation1989) proposes that evolved social mentalities can be used to treat self-relating behaviours linked with depression. Depression accompanies down regulation of drive system neural networks hypothesised to be related to reward seeking, i.e. feeding and mating, and overactivity of threat protection networks hypothetically related to affects of grief, i.e. separation-distress and panic (LeDoux, Citation1998; Panksepp, Citation2010). CFT research has previously identified shame and self-criticism as positively associated with depression in the UK (Judge et al., Citation2012; Kotera, Adhikari, et al., Citation2020) and proposes shame and self-criticism activate the threat protection system and inhibit the drive system (Gilbert, Citation2009). Activation of social mentalities of care-seeking, care-giving and care-receiving promote physiological changes to the affect regulation systems involved in depression, stimulating positive affect and rebalancing the overall affect state (Gilbert, Citation2014; Hermanto & Zuroff, Citation2016). When directed toward the self, CFT research operationalises these ameliorative social mentalities as self-reassurance (Gilbert, Citation2009). It is proposed that shame, self-criticism, and self-reassurance relate to derailment either directly or by analogy.

Derailment as analogue of shame

Shame, a negative self-evaluation accompanied by negative affect (Kotera, Adhikari, et al., Citation2020), is proposed in the present study to be analogous to derailment, analogy being a valuable means to develop psychological theories (Haig, Citation2013). Whereas shame has its origins in evolved social rank behaviours (Gilbert, Citation2022d; Gilbert & McGuire, Citation1998) derailment taps an existential concern, not necessarily indicative of, nor identified with shame. Those feeling derailed do not necessarily feel shame and vice versa. However, since derailment and shame both manifest as negative self-evaluation, derailment is postulated to share cognitive affective features in common with shame, as opposed to alternative affective states such as grief or guilt, which are seen to involve less fundamental self-evaluation (Gilbert, Citation2022a; Tangney & Dearing, Citation2003). The role of shame in depression has been extensively researched within the CFT paradigm, with evidence that shame is consistently related to depression (Kotera, Green, et al., Citation2019; Kotera, Adhikari, et al., Citation2020), and that shame and depression are reduced through CFT intervention (Judge et al., Citation2012; Kelly et al., Citation2009). As has been demonstrated for derailment (Chishima & Nagamine, Citation2021), shame is influenced by normative cultural values (Gilbert & Irons, Citation2009; Kotera, Gilbert, et al., Citation2019). Though passing through phases of stability, values have been shown to change throughout the lifespan (Gouveia et al., Citation2015; Milfont et al., Citation2016). As an individual undergoes changes they reflect upon their identity and make self-evaluations informed by these changing values (Ryff, Citation1982), which may increase or decrease shame (Silfver et al., Citation2008). The existing literature citing shame’s effect on depression does not capture this temporal dynamic of shame; nor have alternative predictors of depression researched within the CFT paradigm, such as attitudes, or role identity, included a temporal dimension. To enhance existing knowledge in this area self-perceived identity change, operationalised as derailment, offers an analogue of shame appropriate to capture this temporal aspect of identity maintenance and address this gap in the literature. By integrating identity- and compassion-based research, it is proposed that insight into psychological risk factors for depression will be deepened. As analogue of shame it is hypothesised that derailment will positively correlate with and predict depression.

Derailment and self-criticism

Self-criticism activates the threat protection affect system, putting the individual at risk of depression, especially under chronic activation (Gilbert, Citation2009). The relationship between shame and depression appears to be statistically mediated by self-criticism in a number of populations, including UK adults (Duarte et al., Citation2017; Gilbert et al., Citation2004), with numerous studies finding a mediation effect whereby, when controlling for the effect of self-criticism on depression, the direct effect of shame on depression is either fully or partially reduced (Kotera & Maughan, Citation2020; Marta-Simões et al., Citation2017). It is proposed in the present research that the relation between depression and derailment, as analogous to shame, may also be statistically mediated to some extent by self-criticism. Self-criticism is proposed as a risk factor present as an individual difference exacerbating vulnerability to depression in derailed individuals. This hypothetical relation finds support in the literature suggesting that identity development has direct associations to both shame and self-criticism, which are internalised forms of other to self relating that manifest as negative self-evaluation (Blatt & Luyten, Citation2009; Gilbert & Irons, Citation2009). Identity has been shown to relate to self-criticism (Kotera & Maughan, Citation2020), however, no identity change constructs have directly been measured against self-criticism. Since derailment’s association with self-criticism has not been investigated to date the present study seeks to bring new findings in this area, hypothesising that derailment will positively correlate with and predict self-criticism, that self-criticism will positively correlate with and predict depression and that self-criticism will statistically mediate the relation between derailment and depression to some degree.

Derailment and self-reassurance

The negative influence of self-criticism on the affect system can be reduced by self-reassurance (Duarte et al., Citation2017; Kotera, Green, et al., Citation2019; Marta-Simões et al., Citation2017), which stimulates the neural networks associated with affects resulting from soothing social mentalities, such as care-receiving (Gilbert, Citation2009). As such, self-reassurance, as a compassionate mode of relating to oneself (Kirby & Gilbert, Citation2019; Petrocchi & Couyoumdjian, Citation2016), appears to be a key therapeutic agent of CFT, supporting Gilbert’s (Citation1989, Citation2009, Citation2014) theoretical model in which social mentalities can be mobilised to rebalance the neural affect regulation system. Since derailment is hypothesised in the present study to be analogous to shame, and to thus predict depression and self-criticism, it is proposed that the influence of self-reassurance as psychological resource will protect derailed individuals from self-criticism and depression. If the individual is able to self-reassure in the face of self-criticism related to feeling derailed, it is hypothesised that depression will be experienced to a lesser degree. These hypotheses form a novel mechanism by which derailment’s predictive relation with depression might be explained and, if evidenced, suggests psychological risk factors vital in identifying and treating depression.

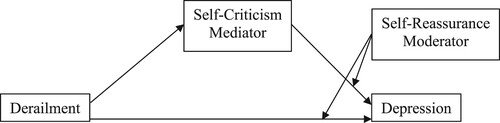

Within parallel mediation models used to date to explore the links between various personality factors influencing depression, self-reassurance has not consistently mediated the relationship (Kotera & Maughan, Citation2020). It is proposed by the current researchers that this may be due to a conceptual issue, and that the role of self-reassurance, rather than mediating the relationship between the personality factor, i.e. shame or derailment, and depression, acts instead as a moderator on the direct effect of the predictor as demonstrated by Cunha et al. (Citation2018) and also on the mediated effect through self-criticism as found by Petrocchi et al. (Citation2019). The conceptual path of this exploratory model is visualised in .

Study aims

In the present study we aim to identify psychological risk factors that contribute to negative self-evaluation and are present as an individual difference in the UK population. As previous psychological research indicates a marked relationship between identity change and depression, and identity change has not yet been included in compassion-based research, the purpose of this study is to examine self-perceived identity change as a self-evaluative cognitive mode of self-relating related to self-criticism and depression.

Measuring self-perceived identity change in the UK with a novel scale based upon the construct termed derailment, it is hypothesised that;

(H1) Derailment will positively correlate with depression and (H2) predict depression.

(H3) Derailment will positively correlate with self-criticism and (H4) predict self-criticism.

(H5) Self-criticism will statistically mediate the effect of derailment on depression.

(H6) Self-reassurance will moderate the effect of derailment influenced self-criticism on depression.

(H7) Self-reassurance will moderate the effect of derailment on depression.

Method

Design

A cross-sectional design enables these hypotheses to be tested whilst minimising the impact of the research on its object. Existing operational definitions of independent variables (IVs) derailment, self-criticism and self-reassurance, and of dependent variable (DV) depression, provide reliable interval measures appropriate to the statistical analyses proposed: correlations to test for relationships between variables, inferential statistics to test predictions, and path analysis to assess the proposed atemporal moderated mediation model (Winer et al., Citation2016). By sampling from the UK population by means of a single survey administration, data pertaining to this novel combination of psychological variables can be captured in a manner enabling comparison of individual differences within this population without manipulation, and in line with previous research in the areas of compassion (Petrocchi et al., Citation2019), identity (Burrow et al., Citation2020), and mental health (Curtis et al., Citation2016). To obtain as representative a sample as possible from the population under investigation, potential confounding variables, such as diagnosed mood disorder or substance addiction, were not controlled for. An a priori power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2009), at α = .05, two-tailed, based on moderate to large effect sizes found in recent related studies (Castilho et al., Citation2015; Kotera, Adhikari, et al., Citation2020; Marta-Simões et al., Citation2017; Petrocchi et al., Citation2019), determined a minimum sample of 90 participants to detect effects at power 1-β = .95 for the proposed multiple regression based analyses with three predictors. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines (von Elm et al., Citation2007).

Participants

Participants (N = 119) completed an online survey delivered through the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, Citation2020), or an identical print version, following ethical approval for the study. Inclusion criteria specified UK residency at time of survey and minimum age of 18 years. For participants with completed demographic items, ages ranged between 18 and 76 (M = 45.0, SD = 16.4), ethnicity was predominantly white (84.9%), with lower numbers of Asian/Asian British (3.4%), Black/African/Caribbean/Black British (.8%), and mixed ethnicity (2.5%) participants, which is representative of the UK population (Office for National Statistics, Citation2019), female (69.7%), and of diverse occupation: employed (47.1%); retired (21%); student (17.6%); unemployed (4.2%).

Measures

The Derailment Scale (Burrow et al., Citation2020) was used to determine self-perceived identity change by self-report. Participants rated their agreement, from (1) Strongly disagree to (5) Strongly agree, for 10 five-point Likert items, such as “I do not feel very connected to who I was in the past.” A higher score indicates a stronger sense of disconnection from past self/selves/motivations. As a new measure it has limited reliability and validity information, but multiple studies have provided internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha between .73 and .85 for North American samples (Burrow et al., Citation2020; Ratner et al., Citation2020). In the current study reliability was strong at α = .88.

The Forms of Self-Criticising/Attacking & Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS; Gilbert et al., Citation2004) is a 22 item scale used to measure self-criticism and self-reassurance by means of self-report, along five-point Likert style responses, from (0) Not at all like me to (4) Extremely like me. Self-criticism items measured two constructs: inadequate self, for example “There is a part of me that puts me down”; and hated self, for example “I have a sense of disgust with myself.” Remaining items, such as “I find it easy to forgive myself,” measured a third independent construct, reassured self. Reliability for the FSCRS typically ranges between .81 and .91 for all sub-scales, in both clinical and non-clinical samples (Castilho et al., Citation2015; Kotera & Maughan, Citation2020). In the current study reliability for all sub-scales was strong (inadequate self α = .93, hated self α = .90, reassured self α = .88).

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Citation2001) is a well-established screening tool for depression, incorporating DSM-IV criteria, with sensitivity to detect depression of varying severity. Participants in this study self-reported the frequency at which they have experienced specific depressive symptoms (e.g. “Feeling down, depressed or hopeless”) over the past two weeks, by responding to nine items from (0) Not at all to (3) Nearly every day. A higher total score indicates higher severity of depression. Reliability of the PHQ-9 in clinical and non-clinical samples is typically very strong, with Cronbach’s alpha over .90 (Cameron et al., Citation2008). In this study reliability was similarly strong at α = .90.

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Derby Research Ethics Approval Process, under British Psychological Society (BPS, Citation2014) guidelines. Recruitment occurred through convenience sampling, using the researchers’ professional social networks and contacts, and university Research Participation Scheme, under which participants gained course credit. Participants were required to provide informed consent and enter an anonymised code before the first questionnaire item to facilitate anonymous withdrawal. After completing the scale items, participants were fully debriefed, including an additional opt-out consent item and instructions for withdrawal up to 14 days post-completion.

Data collection ran from January until May 2020. Responses were screened for consent and missing values. Data for 12 participants failing to complete all scales were removed, a single missing FSCRS reassured self item for one participant was interpolated as a mean of the completed items for this participant on this sub-scale based on an assumption that this data was missing completely at random (Little, Citation1988), and two missing values for age were interpolated as the mean age for the entire sample prior to analysis, following the recommendations for missing data imputation of Shrive et al. (Citation2006). Scale totals were calculated for the 107 participants with complete scale data to provide single continuous variables for derailment, depression and self-reassurance, with self-criticism an aggregated score summing inadequate and hated self (Kotera, Green, et al., Citation2019).

Analytical strategy

To assess the psychometric properties of the derailment scale an exploratory factor analysis was undertaken and reliability calculated. To address hypotheses that derailment correlates with depression (H1) and self-criticism (H3), bivariate correlations were computed. Regression methods addressed hypotheses proposing the power of derailment to predict depression (H2) and self-criticism (H4), as part of a path analysis performed using PROCESS model 15 (moderated mediation, with moderated b-path) to test hypotheses that self-criticism mediates the effect of derailment on depression (H5), but would be moderated by self-reassurance (H6, H7). Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 26 and PROCESS macro version 3.5 (Hayes, Citation2017).

A moderated mediation model was used to evaluate the relationship between the variables and potential interactions. Due to the nature of the design (cross-sectional), this analysis was not used to make causal inferences. Although there is “a universal condemnation of the cross-sectional design” (Spector, Citation2019, p. 125), cross-sectional mediation studies have provided significant insights to lay foundations for theoretical and therapeutical developments (e.g. Rudy et al., Citation1988). Considering that the concept and measurement of derailment is still recent, a cross-sectional design is an efficient approach to establish covariation before investing resources in longitudinal studies.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

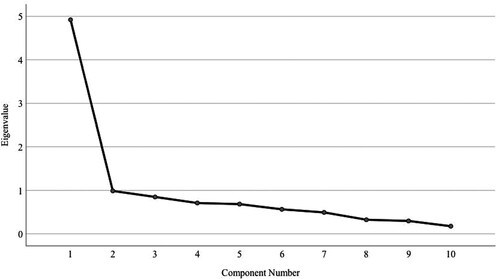

Sample adequacy to run EFA met the criteria required for size (N > 100; Kline, Citation2000), Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin criterion >.60 at .84, and Bartlett's sphericity test was statistically significant (Sharma, Citation1996), χ2(45) = 475.86, p < .001.

In line with the original derailment scale development in Burrow et al. (Citation2020), principal components analysis was used to compute component scores for the factors underlying the 10-item scale. A single factor solution was identified, with only one factor with an eigenvalue > 1 explaining 49.20% of the variance, as shown by the Cattell scree plot in . All items significantly correlated moderately to strongly, with no correlation >.80, confirming the absence of multicollinearity, with the determinant .009 > .00001 indicating the items were sufficiently correlated. Factor loadings per item in the component matrix, reported in , closely matched those reported for the four studies in Burrow et al. (Citation2020).

Table 1. Single factor loadings for the derailment scale.

Descriptive statistics

Derailment and self-reassurance satisfied all assumptions of normality. Self-criticism and depression exhibited positive skew, with kurtosis apparent in the depression distribution. As these are scale values, and reliability for the scales in this sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .90), removal of outliers or transformation was not deemed appropriate (Gough & Hudson, Citation2009), especially considering that the PHQ-9 is designed for clinical samples, and therefore positive skew is expected in administration to non-clinical populations (Kjell et al., Citation2020). Since no evidence of response set bias in five outlier cases was identified, it is assumed that these responses are authentic, indicating their low likelihood of biasing the analysis (Zijlstra et al., Citation2011). With these minor violations of normality assumptions acknowledged parametric tests were implemented.

Pearson’s correlations between all variables, together with descriptive statistics, are presented in .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations between depression, derailment, self-criticism, and self-reassurance for 107 adult UK participants.

Significant correlations were found for all independent variables with the dependent variable at p < .01 (two-tailed). Derailment r(105) = .40, self-criticism r(105) = .69 and self-reassurance r(105) = −.53, supporting hypotheses H1 and H3, and satisfy the conditions necessary to test for the presence of a moderated mediation.

Path analysis

All predictor variables demonstrated a linear relationship to the dependent variable, as demonstrated in and scatter plots for each relationship. The regression models, upon which the path analysis is based, indicated an absence of correlated residuals (Durbin-Watson = 1.97), absence of collinearity prior to interaction term inclusion, homoscedasticity, normality of residuals, and model significance p < .001. Multiple regression results are presented in .

Table 3. Multiple regressions: derailment as predictor of self-criticism and derailment, self-criticism, and self-reassurance as predictors of depression for 107 adult UK participants.

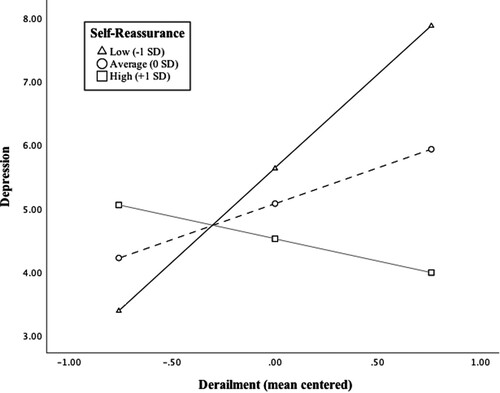

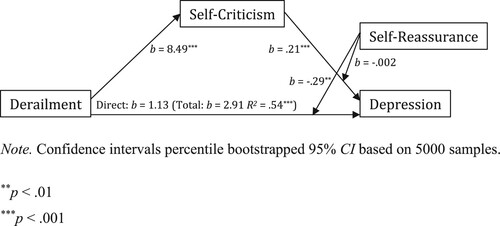

Overall the model accounted for 54% of the variance in depression, F(5, 101) = 24.18, p < .001, R2 = .54, indicating a large effect size, f2 = 1.17, suggesting that, together with self-criticism and self-reassurance, derailment predicted depression, supporting H2. Derailment is seen to have significantly predicted the proposed mediator, self-criticism, b = 8.49, t(105) = 5.65, p < .001, supporting H4. At all levels of self-reassurance (−1 <0> +1 SD mean centred) self-criticism mediated the relationship between derailment and depression: −1 SD: b = 1.86, CI [.83, 3.13]; 0 SD: b = 1.78, CI [.80, 3.12]; +1 SD: b = 1.70, CI [.17, 3.51], supporting H2 and H5. In this model evidence was not found for self-reassurance moderating self-criticism’s relation to depression, b = −.002, t(101) = −.31, p = .75, R2 Change = .000, F(1, 101) = .10, p = .75, refuting H6, though self-reassurance significantly moderated derailment’s relation to depression, accounting for 4% of the variance in depression scores, b = −.29, t(101) = 2.89, p = .005, R2 Change = .04, F(1, 101) = 8.33, p = .005, supporting H7. The exploratory path analysis model is represented in .

Figure 3. Path analysis of the effect on depression of derailment, self-criticism and self-reassurance.

Simple slopes analysis (see ) reveals that, whilst average (0 SD, direct effect), b = 1.13, t(101) = 1.98, p = .051, and high (+1 SD), b = −.70, t(101) = −.93, p = .36, levels of self-reassurance did not significantly influence the relation between derailment and depression, low (−1 SD) self-reassurance significantly predicted a 2.95 unit increase in depression score per unit increase in derailment score, b = 2.95, t(101) = 3.15, p = .002, specifying the moderating role of self-reassurance between derailment and depression.

Controlling for age and sex introduced a nuanced effect for very high levels of self-reassurance, reducing self-criticism’s mediation between derailment and depression. However, since the model remained the same in all other respects, the marginal influence of these controls is deemed insufficient to be included in the final model. Age and sex controlled results are available in supplement Online Resource 1.

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between derailment, a self-perceived disconnection between past and present identity, self-criticism, self-reassurance and depression in the UK. The derailment scale demonstrated high psychometric reliability in the sampled adult members of the UK population, providing the first evidence of the scale’s validity outside the USA or Japan. The findings indicate a strong relationship between all the psychological factors (H1, H3), with a large amount of variance in self-reported depression predicted by the combined influence of derailment, self-criticism and self-reassurance as hypothesised (H2, H4). The mediating role of self-criticism between derailment and depression was found as predicted (H5). Self-reassurance moderated the direct effect of derailment on depression, reducing this to a small degree (H7), however, contrary to H6, self-reassurance was not found to moderate the effect of derailment related self-criticism on depression. The implications of these findings will now be discussed.

Derailment as a unitary psychological construct has received support from this study, with evidence that the derailment scale of Burrow et al. (Citation2020) is capable of measuring this construct within the UK. That higher scores in derailment were related to higher self-criticism and reduced self-reassurance are indicative of the effect losing one’s sense of identity continuity through time can have on one’s modes of self-relating. That the interaction of these psychological factors is related to depression provides evidence for the theoretical model proposed from the literature (Duarte et al., Citation2017; Gilbert, Citation2009; Petrocchi et al., Citation2019), and provides a novel insight into individual differences in personality that may influence an individual’s vulnerability to depression. As such, the present research has shown the derailment scale to be a promising screening tool to identify individuals potentially vulnerable to depression, in Western populations at least.

Derailment was hypothesised to act as a form of negative self-evaluation analogous to the role of shame, with resultant self-criticism expected from recent studies (Kotera, Green, et al., Citation2019; Kotera & Maughan, Citation2020). The strong correlation of derailment with self-criticism, and power of derailment to positively predict self-criticism, provides initial evidence for this association. This finding might explain why both positively and negatively perceived identity changes can detriment mental health (Carter & Marony, Citation2021; Keyes, Citation2000); any discontinuity in identity can potentially trigger self-criticism and associated negative affect. Indeed, the strong link found in this study between derailment and self-criticism could reflect a normative pressure in Western cultures to maintain a consistent individual identity, rather than accepting dynamic role-identities, as has been found in Eastern cultures (English & Chen, Citation2007; Suh, Citation2002). Self-criticism was found to mediate the relation between derailment and depression significantly in this study, providing new insight into the psychological mechanisms involved in derailment’s affective component, and self-criticism’s role as risk factor for derailed individuals. If a person experiences a rift between present and past self and motivations, they are likely to be self-critical, and consequently vulnerable to depression (Gilbert, Citation2009). As derailment indicates a lack of identity with one’s past self (Burrow et al., Citation2020), a disconnected identity may be subject to similar disparities of sympathy found between those close to us and strangers (Loewenstein & Small, Citation2007), with sympathy for distal selves decreasing the more acutely derailment is experienced. Such fracturing would be likely to result in irreconciled cognitive dissonance (Albert, Citation1977; Festinger, Citation1957), and may explain a sense of hated self, which is likely to trigger a threat response dominating the affect system (Gilbert, Citation2014).

As self-reassurance was found to negatively correlate with derailment, self-criticism, and depression, its hypothesised role as a protective factor, reducing the effect of negative self-evaluative psychological processes’ impact on depression, finds some support in the current study. In the regression-based analyses, the effect of self-reassurance proved only to reach significance as an interaction term with derailment. Since highly self-critical individuals can be expected not to exhibit high levels of self-reassurance (Gilbert & Irons, Citation2004; López et al., Citation2018), and are even prone to a fear of compassion (Hart et al., Citation2020), the proposed protective influence of self-reassurance may only become evident after such individuals have received intervention to develop self-reassurance (Hermanto & Zuroff, Citation2016). That self-reassurance negatively correlated with self-criticism and depression supports this interpretation, and indicates the protective advantage self-reassurance can have for those individuals less susceptible to self-criticism. The moderation analysis provided further insight into this effect, finding low levels of self-reassurance to increase vulnerability to derailment induced depression, whereas increased levels of self-reassurance appear to protect derailed individuals from depression to a small extent. The protective effect of self-reassurance may be attributed to early life experiences reinforcing innate patterns of other-to-self relating which, in adult life, support self-to-self relating behaviours (Hermanto & Zuroff, Citation2016) conducive to a non-critical perspective on identity consistency (Wong et al., Citation2019). Conversely, through a lack of adequate other-to-self role models, discrepant identity finds no route to acceptance (Gilbert et al., Citation2006), serving to undermine the existential position one holds, with detrimental consequences to mental health (Laing, Citation1965; Yalom, Citation1980). To accept identity changes, CFT exercises, including the use of mental imagery (Gilbert et al., Citation2006), might be utilised to foster positive regard for the self, as an efficacious actor, dealing with life’s circumstances (Gilbert, Citation2009). It is important to acknowledge that compassion-based interventions can meet with resistance in individuals for whom a self-critical style is perceived as integral to self-identity (Gilbert, Citation2022b). CFT includes psychoeducation and guided discovery to enable clients to distance themselves from self-critical thoughts, fostering self-reassurance through self-compassion exercises (Gilbert, Citation2022b) such as chair work, expressive writing and reframing, amongst others, in treating depression (Simos, Citation2022). CFT is centred on nurturing a compassionate self-identity (Gilbert, Citation2022c) and, as such, addresses identity concerns directly.

That self-reassurance protects against derailment is a new contribution to identity research, and the first finding for a psychological factor protecting against the negative mental health correlates of derailment. As the present study failed to find reliable evidence that self-reassurance protects mental health against the effect of self-criticism related to derailment, the benefits of concentrating treatment on reducing derailment itself, in addition to promoting self-reassurance, are recommended for further research in applied settings. Since psychotherapy is centred on change (Yalom, Citation1980), the impact of derailment through a patient’s treatment course is of high relevance. Evidence suggests derailment reduction may be achieved by fostering a sense of self-continuity through autobiographical narrative exercises (Burrow et al., Citation2020; Sedikides et al., Citation2018), in particular encouraging the social emotion of nostalgia (Sedikides et al., Citation2015; Zou et al., Citation2018).

The derailment scale has been shown in this study to be effectively administered online. It is therefore recommended that practitioners adopt this mechanism if screening for derailment. Recent findings of a randomised controlled trial for online delivery of self-compassion enhancement, targeting increased self-reassurance, provide evidence that this may be effective even in circumstances where direct contact with mental health services is not possible (Halamová et al., Citation2021), so is recommended to ensure treatment is accessible to the widest populations.

Although the findings from this study appear to be consistent with social mentality theory (Gilbert, Citation1989), the cross-sectional correlational design limits the degree to which a causal relationship can be ascertained. However, the failure to find evidence that self-reassurance moderates the effect of self-criticism on depression, rather than being a methodological artefact, may question the validity of the soothing effect self-reassurance is purported to have within the affect regulation system. If this criticism is upheld, it would have potential ramifications for the neuro-affective theory of Panksepp (Citation2010), upon which social mentality theory is based (Gilbert, Citation2014). The evolutionary psychological explanation Gilbert’s (Citation1989) social mentality theory relies upon is also open to criticism, since such theories, by their nature, must make unfalsifiable claims about historical human development (Fodor, Citation2000). The practical efficacy of social mentality theory, as it informs CFT, presents compelling argument against these criticisms (Kirby & Gilbert, Citation2019).

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be taken into consideration when assessing the reliability and generalizability of its findings. The proposed model is based upon correlational statistical inferences, from a cross-section sample at a single point in time, and therefore causality and direction of effect are inconclusive. Recent research has postulated a cyclical relation between derailment and depression, suggesting that the model proposed in this study is not the only possible explanation for the effects observed (Ratner et al., Citation2019; Ratner et al., Citation2020). Longitudinal studies are needed to explore this relationship further. Nevertheless, it is important to note that a longitudinal design would present only limited improvement to the interpretation of the present results. This is because merely assessing the variables at arbitrary time points would not allow to infer causality. It would be crucial that the timeframe between the measurements matches the timeframe of the phenomenon (Spector, Citation2019). Therefore, the question that needs to be addressed is for how long derailment needs to occur before depressive symptoms can be observed.

This study also did not control for a number of variables that may have confounded the results. Bias from demand characteristics, potentially relevant due to survey administration differences, i.e. online vs. print, were not tested for, owing to a very small number of print versions returned. Shame and other potential correlates of self-criticism, were not controlled for, having previously been researched. The impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic, which occurred during data collection, has been linked to various mental health concerns and cited as potential cause of identity crisis (Ashforth, Citation2020; Templeton et al., Citation2020). Such influence has not been controlled for and could have affected the self-reported levels on each variable measured. Since the study findings pertain to relationships between variables rather than the specific levels of these variables, which during the pandemic have empirically demonstrated the same roles within mental health (Kotera, Mayer, et al., Citation2021; Lau et al., Citation2020) or, in the case of derailment, been theorised to (Hill & Burrow, Citation2020), this confound is not necessarily salient.

As noted in the results, some violations of normality were apparent for depression and self-criticism scores, potentially due to some aspects of recruitment. Caution should therefore be exercised in generalising the findings. The sole use of self-selection through opportunity sampling may have introduced common method variance, inflating correlation strengths (Lindell & Whitney, Citation2001).

Since cultural differences in self-relating have been demonstrated between individualistic cultures such as that of the UK, and collectivistic cultures, such as that of Japan (Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991), generalizability of this study’s findings outside individualistic cultures requires appraisal. This limitation has been found to extend to response style in self-report measures as used in the present research, with members of collectivistic cultures demonstrating higher levels of acquiescent responding then members of individualistic cultures (Kotera, Van Laethem, et al., Citation2020).

Further research

As the first study to integrate identity change and depression research with compassion-focused theory, the findings indicate numerous developments and alternative perspectives, to progress this novel research area. To address some of the limitations of this study, and to test the model proposed, longitudinal research is suggested. This would be of potential benefit to participants if intervention were part of the design, targeting reduction in derailment. Alternatively, building upon the strengths of this study’s methodology, further correlational research incorporating theoretically relevant exogenous variables, for instance factors related to self-criticism, such as shame (Kotera, Green, et al., Citation2019), or mediators of self-criticism and self-reassurance, such as cognitive fusion (Noureen & Malik, Citation2019), could improve our understanding of the relationships and directions of effects suggested in the present findings. Working within the same paradigm, it would also be instructive to probe further the effect derailment has on the sub-scales of self-criticism, and at different severities of depression, taking into account the clinical classifications made at boundary scores of the PHQ-9; anticipating that hated self and inadequate self (Castilho et al., Citation2015; Kotera, Dosedlova, et al., Citation2021), and mild, moderate or severe depression (Tolentino & Schmidt, Citation2018), may each have discernibly different relation to derailment (Ratner et al., Citation2020). It is also important to assess the derailment scale in different populations, exploring factorial invariance to address potential biases in any group comparisons. There are many populations in which group differences in this construct could be evident and, if found, might inform psychological treatments to deliver improved health outcomes.

This quantitative study has identified trends in the population identified as at risk of mental health problems through forms of self-relating, but insight into the individual’s lived-experience of derailment and its effects must be sought in qualitative extensions to our findings. Despite recent psychological definition, derailment is thematically present in much literature and art, and it is the existential dimensions of this construct that might be of most interest to the qualitative or cross-disciplinary researcher.

Conclusion

This study has integrated existing research into identity change and mental health with compassion-focused theory, finding that self-criticism and self-reassurance play an intermediate role between derailment and depression in a representative sample of the general UK population. Findings indicate that individuals experiencing a lack of identity continuity are vulnerable to self-criticism and depression. Contrary to the proposed hypothetical model, self-reassurance was not found to reduce the effects of self-criticism on depression, though it was shown to afford some protection against the remaining effect of derailment on depression. This is the first finding for a psychological factor protecting against the mental health consequences of derailment, indicating that interventions enhancing self-perceived identity continuity and self-reassurance will most effectively benefit sufferers of depression. Further research into these psychological factors is recommended.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study has been approved by the University of Derby Research Ethics Committee and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to participate and publish

All participants provided informed consent prior to and subsequent to participation including consent to publish.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (85.3 KB)Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Rory D. Colman and Katia C. Vione. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Rory D. Colman and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Psycharchives at http://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.4189.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rory D. Colman

Rory Colman is an independent researcher currently collaborating with the University of Derby, UK, in programmes investigating mental health. In addition to mental health, his research interests include psychotherapeutic theory and practice, consciousness, self and identity, human–computer interaction and online learning.

Katia C. Vione

Dr Katia Vione is a lecturer in Psychology at the University of Derby, UK. Her main area of research is social psychology and individual differences, particularly in relation to human values and wellbeing.

Yasuhiro Kotera

Dr Yasuhiro Kotera is Associate Professor in the Institute of Mental Health, School of Health Sciences, at the University of Nottingham, UK. As an Accredited Psychotherapist and certified Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) Trainer, he has worked with diverse clients and trained practitioners internationally. His research focuses on mental health, cross-culture and triplets.

References

- Adler, J. M., Turner, A. F., Brookshier, K. M., Monahan, C., Walder-Biesanz, I., Harmeling, L. H., Albaugh, M., McAdams, D. P., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2015). Variation in narrative identity is associated with trajectories of mental health over several years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(3), 476–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038601

- Albert, S. (1977). Temporal comparison theory. Psychological Review, 84(6), 485–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.6.485

- Ashforth, B. E. (2020). Identity and identification during and after the pandemic: How might COVID-19 change the research questions we ask? Journal of Management Studies, https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12629

- Bearden, W. O., Money, R. B., & Nevins, J. L. (2006). A measure of long-term orientation: Development and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(3), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070306286706

- Beck, A. T., & Alford, B. A. (2009). Depression: Causes and treatment. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Becker, M., Vignoles, V. L., Owe, E., Easterbrook, M. J., Brown, R., Smith, P. B., Abuhamdeh, S., Cendales Ayala, B., Garðarsdóttir, R. B., Torres, A., Camino, L., Bond, M. H., Nizharadze, G., Amponsah, B., Schweiger Gallo, I., Prieto Gil, P., Lorente Clemares, R., Campara, G., Espinosa, A., … Lay, S. (2018). Being oneself through time: Bases of self-continuity across 55 cultures. Self and Identity, 17(3), 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2017.1330222

- Beugelsdijk, S., & Welzel, C. (2018). Dimensions and dynamics of national culture: Synthesizing Hofstede with Inglehart. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 49(10), 1469–1505. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118798505

- Blatt, S. J., & Luyten, P. (2009). A structural–developmental psychodynamic approach to psychopathology: Two polarities of experience across the life span. Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 793–814. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000431

- British Psychological Society. (2014). Code of human research ethics [PDF document]. https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/bps.org.uk/files/Policy%20-%20Files/BPS%20Code%20of%20Human%20Research%20Ethics.pdf.

- Burrow, A. L., Hill, P. L., Ratner, K., & Fuller-Rowell, T. E. (2020). Derailment: Conceptualization, measurement, and adjustment correlates of perceived change in self and direction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(3), 584–601. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000209

- Cameron, I. M., Crawford, J. R., Lawton, K., & Reid, I. C. (2008). Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 58(546), 32–36. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp08X263794

- Campbell, J. D., Assanand, S., & Di Paula, A. (2003). The structure of the self-concept and its relation to psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 71(1), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.t01-1-00002

- Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavallee, L. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(1), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.141

- Carter, M. J., & Marony, J. (2021). Examining self-perceptions of identity change in person, role, and social identities. Current Psychology, 40(1), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9924-5

- Castilho, P., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, J. (2015). Exploring self-criticism: Confirmatory factor analysis of the FSCRS in clinical and nonclinical samples. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1881

- Chishima, Y., & Nagamine, M. (2021). Unpredictable changes: Different effects of derailment on well-being between North American and East Asian samples. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00375-4

- Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., Dingle, G. A., Haslam, C., & Jetten, J. (2014). Depression and social identity: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(3), 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314523839

- Cunha, M., Xavier, A., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2018). Negative emotional memories and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Can self-reassurance play a protective role? European Psychiatry, 48, S179.

- Curtis, E. A., Comiskey, C., & Dempsey, O. (2016). Importance and use of correlational research. Nurse Researcher, 23(6), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.2016.e1382

- Department of Health. (2011). No health without mental health: A cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_123991

- Duarte, C., Stubbs, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Matos, M., Gale, C., Morris, L., & Gilbert, P. (2017). The impact of self-criticism and self-reassurance on weight-related affect and well-being in participants of a commercial weight management programme. Obesity Facts, 10(2), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1159/000454834

- English, T., & Chen, S. (2007). Culture and self-concept stability: Consistency across and within contexts among Asian Americans and European Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(3), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.478

- Erikson, E. H. (1977). Childhood and society. Paladin (Original work published 1950).

- Erikson, E. H., & Erikson, J. M. (1997). The life cycle completed. W.W. Norton.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Fodor, J. (2000). The mind doesn’t work that way. The MIT Press.

- Gilbert, P. (1989). Human nature and suffering. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind. Robinson.

- Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043

- Gilbert, P. (2022a). Compassion focused therapy. In P. Gilbert & G. Simos (Eds.), Compassion focused therapy (pp. 24–89). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003035879-3

- Gilbert, P. (2022b). Internal shame and self-disconnection. In P. Gilbert & G. Simos (Eds.), Compassion focused therapy (pp. 164–206). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003035879-6

- Gilbert, P. (2022c). Introducing and developing CFT functions and competencies. In P. Gilbert & G. Simos (Eds.), Compassion focused therapy (pp. 243–272). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003035879-9

- Gilbert, P. (2022d). Shame, humiliation, guilt, and social status. In P. Gilbert & G. Simos (Eds.), Compassion focused therapy (pp. 122–163). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003035879-5

- Gilbert, P., Baldwin, M. W., Irons, C., Baccus, J. R., & Palmer, M. (2006). Self-criticism and self-warmth: An imagery study exploring their relation to depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(2), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1891/jcop.20.2.183

- Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J. N. V., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466504772812959

- Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2004). A pilot exploration of the use of compassionate images in a group of self-critical people. Memory, 12(4), 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210444000115

- Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2009). Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. Adolescent Emotional Development and the Emergence of Depressive Disorders, 1, 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511551963.011

- Gilbert, P., & McGuire, M. T. (1998). Shame, status, and social roles: Psychobiology and evolution. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews (Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture (pp. 99–125). Oxford University Press.

- Gough, K., & Hudson, P. (2009). Psychometric properties of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in family caregivers of palliative care patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 37(5), 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.012

- Gouveia, V. V., Vione, K. C., Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2015). Patterns of value change during the life span: Some evidence from a functional approach to values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(9), 1276–1290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215594189

- Haig, B. D. (2013). Analogical modeling: A strategy for developing theories in psychology. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 348. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00348

- Halamová, J., Kanovský, M., Varšová, K., & Kupeli, N. (2021). Randomised controlled trial of the new short-term online emotion focused training for self-compassion and self-protection in a nonclinical sample. Current Psychology, 40(1), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9933-4

- Hart, J. S., Kirby, J. N., Steindl, S. R., Kane, R. T., & Mazzucchelli, T. G. (2020). Insecure striving, self-criticism, and depression: The prospective moderating role of fear of compassion from others. Mindfulness, 11(7), 1699–1709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01385-8

- Hayes, A. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Hermanto, N., & Zuroff, D. C. (2016). The social mentality theory of self-compassion and self-reassurance: The interactive effect of care-seeking and caregiving. The Journal of Social Psychology, 156(5), 523–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2015.1135779

- Hill, P. L., & Burrow, A. L. (2020). Derailment as a risk factor for greater mental health issues following pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113093

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Judge, L., Cleghorn, A., McEwan, K., & Gilbert, P. (2012). An exploration of group-based compassion focused therapy for a heterogeneous range of clients presenting to a community mental health team. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 5(4), 420–429. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2012.5.4.420

- Kelly, A. C., Zuroff, D. C., & Shapira, L. B. (2009). Soothing oneself and resisting self-attacks: The treatment of two intrapersonal deficits in depression vulnerability. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 33(3), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-008-9202-1

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2000). Subjective change and its consequences for emotional well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 24(2), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005659114155

- Keyes, C. L. M., & Ryff, C. D. (2000). Subjective change and mental health: A self-concept theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 264–279. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695873

- Kirby, J. N., & Gilbert, P. (2019). Commentary regarding Wilson et al. (2018) “Effectiveness of ‘self-compassion’ related therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” All is not as it seems. Mindfulness, 10(6), 1006–1016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1088-8

- Kjell, O. N. E., Kjell, K., Garcia, D., & Sikström, S. (2020). Semantic similarity scales: Using semantic similarity scales to measure depression and worry. In S. Sikström & D. Garcia (Eds.), Statistical semantics: Methods and applications (pp. 53–72). Springer Nature.

- Kline, P. (2000). Handbook of psychological testing (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Kotera, Y., Adhikari, P., & Sheffield, D. (2020). Mental health of UK hospitality workers: Shame, self-criticism and self-reassurance. Service Industries Journal, https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2020.1713111

- Kotera, Y., Dosedlova, J., Andrzejewski, D., Kaluzeviciute, G., & Sakai, M. (2021). From stress to psychopathology: Relationship with self-reassurance and self-criticism in Czech University students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00516-z

- Kotera, Y., Gilbert, P., Asano, K., Ishimura, I., & Sheffield, D. (2019). Self-criticism and self-reassurance as mediators between mental health attitudes and symptoms: Attitudes toward mental health problems in Japanese workers. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 22(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12355

- Kotera, Y., Green, P., & Sheffield, D. (2019). Mental health attitudes, self-criticism, compassion, and role identity among UK social work students. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(2), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy072

- Kotera, Y., & Maughan, G. (2020). Mental health of Irish students: Self-criticism as a complete mediator in mental health attitudes and caregiver identity. Journal of Concurrent Disorders, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.54127/BHNM9453.

- Kotera, Y., Mayer, C. H., & Vanderheiden, E. (2021). Cross-cultural comparison of mental health between German and South African employees: Shame, self-compassion, work engagement, and work motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627851

- Kotera, Y., Van Laethem, M., & Ohshima, R. (2020). Cross-cultural comparison of mental health between Japanese and Dutch workers: Relationships with mental health shame, self-compassion, work engagement and motivation. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 27(3), 511–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-02-2020-0055

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Laing, R. D. (1965). The divided self: An existential study in sanity and madness. Penguin Books.

- Lau, B. H.-P., Chan, C. L.-W., & Ng, S.-M. (2020). Self-compassion buffers the adverse mental health impacts of COVID-19-related threats: Results from a cross-sectional survey at the first peak of Hong Kong's outbreak. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 585270. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.585270

- LeDoux, J. (1998). The emotional brain. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114

- Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

- Loewenstein, G., & Small, D. A. (2007). The scarecrow and the Tin Man: The vicissitudes of human sympathy and caring. Review of General Psychology, 11(2), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.11.2.112

- López, A., Sanderman, R., & Schroevers, M. J. (2018). A close examination of the relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1470–1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0891-6

- Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

- Marta-Simões, J., Ferreira, C., & Mendes, A. L. (2017). Shame and depression: The roles of self-reassurance and social safeness. European Psychiatry, 41(S1), S241–S241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.02.012

- McAdams, D. P., & McLean, K. C. (2013). Narrative identity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 233–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413475622

- McLean, K. C. (2008). Stories of the young and the old: Personal continuity and narrative identity. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.254

- Milfont, T. L., Milojev, P., & Sibley, C. G. (2016). Values stability and change in adulthood: A 3-year longitudinal study of rank-order stability and mean-level differences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(5), 572–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216639245

- Noureen, S., & Malik, S. (2019). Conceptualized-self and depression symptoms among university students: Mediating role of cognitive fusion. Current Psychology, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00450-3

- Office for National Statistics. (2019). Research report on population estimates by ethnic group and religion. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/researchreportonpopulationestimatesbyethnicgroupandreligion/2019-12-04#population-estimates-by-ethnic-group

- Ogueji, I. A., Okoloba, M. M., & Ceccaldi, B. M. D. (2021). Coping strategies of individuals in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychology, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01318-7

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development/European Union. (2018). Health at a glance: Europe 2018 state of health in the EU cycle. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en

- Panksepp, J. (2010). Affective neuroscience of the emotional BrainMind: Evolutionary perspectives and implications for understanding depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(4), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/jpanksepp

- Petrocchi, N., & Couyoumdjian, A. (2016). The impact of gratitude on depression and anxiety: The mediating role of criticizing, attacking, and reassuring the self. Self & Identity, 15(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1095794

- Petrocchi, N., Dentale, F., & Gilbert, P. (2019). Self-reassurance, not self-esteem, serves as a buffer between self-criticism and depressive symptoms. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92(3), 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12186

- Qualtrics, Provo, UT. (2020). The data analysis for this paper was generated using Qualtrics software, Version May 2020 of the Qualtrics Research Suite. Copyright © 2020 Qualtrics. Qualtrics and all other Qualtrics product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of Qualtrics, Provo, UT. http://www.qualtrics.com

- Ratner, K., Burrow, A. L., & Mendle, J. (2020). The unique predictive value of discrete depressive symptoms on derailment. Journal of Affective Disorders, 270, 65–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.097

- Ratner, K., Mendle, J., Burrow, A. L., & Thoemmes, F. (2019). Depression and derailment: A cyclical model of mental illness and perceived identity change. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(4), 735–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619829748

- Rudy, T. E., Kerns, R. D., & Turk, D. C. (1988). Chronic pain and depression: Toward a cognitive-behavioral mediation model. Pain, 35(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(88)90220-5

- Ryff, C. D. (1982). Self-perceived personality change in adulthood and aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.108

- Sedikides, C., & Strube, M. J. (1997). Self evaluation: To thine own self be good, to thine own self be sure, to thine own self be true, and to thine own self be better. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 209–269). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60018-0

- Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Cheung, W.-Y., Routledge, C., Hepper, E. G., Arndt, J., Vail, K., Zhou, X., Brackstone, K., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2016). Nostalgia fosters self-continuity: Uncovering the mechanism (social connectedness) and consequence (eudaimonic well-being). Emotion, 16(4), 524–539. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000136

- Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Grouzet, F. (2018). On the temporal navigation of selfhood: The role of self-continuity. Self and Identity, 17(3), 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2017.1391115

- Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Routledge, C., & Arndt, J. (2015). Nostalgia counteracts self-discontinuity and restores self-continuity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2073

- Sharma, S. (1996). Applied multivariate techniques. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Shrive, F. M., Stuart, H., Quan, H., & Ghali, W. A. (2006). Dealing with missing data in a multi-question depression scale: A comparison of imputation methods. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-57

- Silfver, M., Helkama, K., Lönnqvist, J. E., & Verkasalo, M. (2008). The relation between value priorities and proneness to guilt, shame, and empathy. Motivation and Emotion, 32(2), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9084-2

- Simos, G. (2022). Compassion focused therapy: An evolutionary and biopsychosocial understanding of depression and its management. In P. Gilbert & G. Simos (Eds.), Compassion focused therapy (pp. 534–548). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003035879-26

- Spector, P. E. (2019). Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8

- Suh, E. M. (2002). Culture, identity consistency, and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1378–1391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1378

- Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2003). Shame and guilt. Guilford Press.

- Templeton, A., Guven, S. T., Hoerst, C., Vestergren, S., Davidson, L., Ballentyne, S., Madsen, H., & Choudhury, S. (2020). Inequalities and identity processes in crises: Recommendations for facilitating safe response to the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(3), 674–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12400

- Tolentino, J. C., & Schmidt, S. L. (2018). DSM-5 criteria and depression severity: Implications for clinical practice. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 450. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00450

- von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., Vandenbroucke, J. P., & STROBE Initiative. (2007). The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Medicine, 4(10), e296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296

- Waterman, A. S., Geary, P. S., & Waterman, C. K. (1974). Longitudinal study of changes in ego identity status from the freshman to the senior year at college. Developmental Psychology, 10(3), 387–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036438

- Winer, E. S., Cervone, D., Bryant, J., McKinney, C., Liu, R. T., & Nadorff, M. R. (2016). Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: Atemporal associations do not imply causation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(9), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22298

- Wong, A. E., Dirghangi, S. R., & Hart, S. R. (2019). Self-concept clarity mediates the effects of adverse childhood experiences on adult suicide behavior, depression, loneliness, perceived stress, and life distress. Self and Identity, 18(3), 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1439096

- World Health Organization. (2012). Global burden of mental disorders and the need for a comprehensive, coordinated response from health and social sectors at the country level.

- World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

- Zijlstra, W. P., van der Ark, L. A., & Sijtsma, K. (2011). Outliers in questionnaire data: Can they be detected and should they be removed? Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 36(2), 186–212. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998610366263

- Zou, X., Wildschut, T., Cable, D., & Sedikides, C. (2018). Nostalgia for host culture facilitates repatriation success: The role of self-continuity. Self and Identity, 17(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2017.1378123