?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The mental health of international students has become a concern, as they face high levels of psychological distress. We designed a five-week acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) workshop with two additional individual assessment meetings. The intervention aimed at helping international students attending a Finnish university to reduce their symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety, and enhance skills of psychological flexibility. The post-assessment was conducted seven weeks after the pre-measurement. Using data from 53 participants, an evaluation indicated that statistically and clinically significant reductions in symptoms were observed, and the workshop was well received. Regression analyses revealed that changes in psychological inflexibility, mindfulness, and value-based living acted as predictors of change in symptoms. Furthermore, changes in these psychological skills predicted changes in different kinds of distress. This study suggests that a brief group intervention might be a feasible alternative for enhancing the psychological well-being of international students.

Introduction

According to Forbes-Mewett (Citation2019), mental health is one of the leading contemporary concerns regarding international students. Indeed, studies suggest that international students face a range of challenges, which may result in feelings of isolation, loneliness, homesickness, and psychological distress, such as stress, anxiety, and depression (e.g. Brown & Brown, Citation2013; Mori, Citation2000; Russell, Rosenthal, & Thomson, Citation2010; Sawir, Marginson, Deumert, Nyland, & Ramia, Citation2008). For example, 41% of international students in Australia reported having experienced a significant level of stress as a result of homesickness, cultural shock, or discrimination. In terms of depression, Rice, Choi, Zhang, Morero, and Anderson (Citation2012) investigated international college students in the US and found that close to 40% of them met the clinical cut-off point of depressive symptoms. In line with Rosenthal, Russell, and Thomson (Citation2006), Shadowen, Williamson, Guerra, Ammigan, and Drexler (Citation2019) found that nearly 50% of international students reported clinically significant depression and that approximately 25% reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety. The psychological distress experienced by international students may ultimately cause poor academic performance, delay, withdrawal, or study interruptions (Hauschildt, Gwosc, Netz, & Mishra, Citation2015).

In addition to coping in a different cultural context, Forbes-Mewett and Sawyer (Citation2016) identified another critical factor to the mental health of international students: recognising and seeking professional help for mental health problems. International students may be reluctant to seek help from counselling centres or other services (Aguiniga, Madden, & Zellmann, Citation2016; Forbes-Mewett & Sawyer, Citation2016). For example, Lu, Dear, Johnston, Wootton, and Titov (Citation2014) found that 54% of the Chinese international students reported high levels of psychological distress, but only 9% of these students had received mental health services. Cultural differences in beliefs about mental health problems and stigma associated with psychological disturbances may inhibit international students from seeking help (Mori, Citation2000). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, Citation2012) is a process-based cognitive behavioural therapy approach that has been used effectively to alleviate stigma and to treat psychological distress (A-Tjak et al., Citation2015; Gloster, Walder, Levin, Twohig, & Karekla, Citation2020; Masuda et al., Citation2007).

The aim of ACT is to foster psychological flexibility through six related skills: acceptance, defusion, being present, self as context, values, and committed action (Hayes, Citation2019). Acceptance is about being open to one’s own experiences, especially in relation to unpleasant thoughts and emotions. Defusion involves undermining the negative effects of cognitions by teaching skills that enable people to take distance from thoughts. Defusion, in turn, is facilitated by self as context, a perspective from which an individual can become aware of their experiences without becoming overly attached to them, while contact with the present moment is about flexibly attending to an experience as it is happening in the now. Furthermore, a connection to one’s own values is represented by the ability to choose what matters and acting in service of them by performing value-oriented actions. Psychological inflexibility, the counterpart to psychological flexibility, has been associated with greater levels of psychological distress, rumination, and physical health problems (Lee & Orsillo, Citation2014; Ruiz & Odriozola-González, Citation2015; Stabbe, Rolffs, & Rogge, Citation2019). Among university students, inflexibility has been found to be linked to academic procrastination and negative emotional states, such as stress, depression, and anxiety (Levin et al., Citation2014; Ruiz, Citation2014; Tavakoli, Broyles, Reid, Sandoval, & Correa-Fernández, Citation2019). Masuda and Tully (Citation2012) demonstrated that both mindfulness and psychological flexibility were inversely associated with somatic symptoms, depression, and anxiety among a non-clinical sample of college students, suggesting that psychological inflexibility is associated with a wide range of psychological distress.

Regarding ACT interventions for higher education students, a systematic review showed that ACT training, implemented in various formats, has a positive, albeit small effect (d = 0.29), on student well-being (Howell & Passmore, Citation2019). ACT may alleviate anxiety and depression (e.g. Grégoire, Lachance, Bouffard, & Dionne, Citation2018; Levin et al., Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2020), enhance well-being and decrease stress (Katajavuori, Vehkalahti, & Asikainen, Citation2021; Räsänen, Lappalainen, Muotka, Tolvanen, & Lappalainen, Citation2016), and can be used as a treatment in combination with counselling services (Levin, Hayes, Pistorello, & Seeley, Citation2016; see also Pistorello, Citation2013). In the context of international students, research on ACT remains scarce. ACT has been examined among Japanese international students attending college in the US (Muto, Hayes, & Jeffcoat, Citation2011). Muto et al. (Citation2011) conducted a study with 70 Japanese international students in the US who were randomly assigned to a waitlist or to receive an ACT self-help book bibliotherapy intervention. Students who received the self-help book showed significantly better general mental health at post and follow up measurements (general mental health, within group ES d = 0.98; Muto et al., Citation2011). Recently, a study piloted an ACT-based group intervention focused on helping Chinese students manage stress when studying abroad. The intervention protocol was developed from a well-established ACT work-stress protocol and adapted for the Chinese international student population. The results showed reductions in depression (within group ES d = 2.68), stress (d = 2.17), anxiety (d = 1.71), and physical symptoms (d = 1.04) at post-intervention and these changes were maintained at a one-month follow-up (Xu, O’Brien, & Chen, Citation2020).

In summary, several studies have revealed concerning rates of psychological distress among international students. Therefore, brief interventions that support their well-being are warranted. There is also a need for interventions that do not only target psychological symptoms but also enhance skills of mindfulness and psychological flexibility (Masuda & Tully, Citation2012), as these skills are associated with psychological well-being. An ACT approach would provide a treatment that specifically targets these aims.

Aim of the current study

The main objective of this pilot study was to examine whether a brief group-based ACT workshop would be effective at reducing psychological symptoms and increasing psychological flexibility skills among international students experiencing study-related stressors. We hypothesised that participation in a five-week workshop would decrease symptoms of perceived stress, depression, and anxiety and increase psychological flexibility skills. The second objective of our study was to enhance our understanding of psychological processes or, more precisely, skills connected to favourable changes in psychological symptoms among international students. We expected that a decrease in psychological inflexibility and an increase in mindfulness and engaged living skills would predict a reduction in symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety. Furthermore, we were interested in identifying which of these psychological skills acted as the strongest predictors of change in psychological symptoms.

Methods

Recruitment and participants

International students were recruited from the University of Jyväskylä following the posting of ads and flyers online and on campus, inviting them to participate in a group workshop composed of five weekly meetings. The ad specified that the workshop aimed to promote student well-being by covering topics such as how to more effectively cope with life and study-related stressors and how to engage in life and studies in a more meaningful way. The participants were required to be enrolled as international students at the University of Jyväskylä and be at least 18 years old. Students who were simultaneously receiving psychological therapy were excluded.

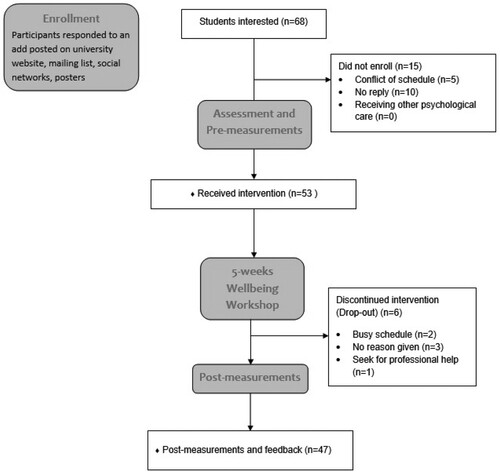

Sixty-eight international students indicated via email that they were willing to participate in the workshop and were contacted via email to schedule the initial interview. Among them, five potential participants had a busy schedule and declined to participate, and ten students did not respond (). Finally, pre-measurements were collected from 53 students. The post-measurement was completed seven to eight weeks after the pre-measurement. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by Central Finland Healthcare District’s Ethics Committee (registration number 14U/2012).

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram of the progress through the phases of the intervention (that is, enrolment, assessment and pre-measurements, intervention period, post-measurement and feedback). Available at: http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement/flow-diagram

Participant characteristics

The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 46 years, with most of them being female (n = 44; 83%) and between 18 and 25 (n = 31; 58.5%). Around half of the students were pursuing degree programmes (n = 29; 54.7%), and the other half were exchange students (n = 24; 45.3%). The students belonged to a variety of ethnicities and 28 nationalities, with most students coming from Asia (n = 17; 32%). See .

Table 1. Participant characteristics (n = 53).

Intervention

The intervention was offered once per semester between 2017 and 2019 and completed in face-to-face groups of five to 10 students (totally seven groups). The content of the 10-hour intervention () was as follows: an individual pre-assessment interview (60–90 mins), five weekly workshops lasting 90 mins each, and a closing individual meeting for post-measurements and feedback (60 mins, one week after the last workshop; see ). Prior to the workshop, the students were invited to participate in an individual semi-structured interview based on the model adapted from Strosahl, Robinson, and Gustavsson (Citation2012) and pre-assessment including a set of online questionnaires. Each weekly workshop meeting introduced a new ACT process () and started with a mindfulness exercise. Second, the past week’s theme was summarised, followed by a discussion in pairs. Next, the topic and core message of ACT was introduced, and a variety of experiential exercises and metaphors, including animated videos, were utilised, followed by discussion in pairs or in groups. The content was related to issues relevant to international students, such as values related to studying abroad, frustration, procrastination, and feelings of being an outsider (see ). Each workshop closed with a home assignment to be conducted throughout the week, including handouts and ACT skills for application in daily life (). Thus, the intervention was not only psychoeducational but included a large amount of interaction and discussion and provided the core components of the ACT model in practical experiential and interactive exercises. The content of the intervention was based on earlier ACT interventions developed by the research team and conducted by two leaders, who were two of the authors (F.B. and S.G.) of this article. The persons delivering the intervention were former international students at the University of Jyväskylä, and they were trained and supervised in ACT methods by the researchers who were experts in ACT with 10–20 years of experience (P.L., P.R., R.L.).

Table 2. Structure and content of the intervention.

Measurements

Outcome measures

The Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10) was used to measure symptoms of stress (Cohen & Williamson, Citation1988; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, Citation1983), and it was our main outcome measurement. The PSS-10 is a 10-item scale in which respondents’ rate how stressful they perceive their lives to have been in the past month through a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 4 = very often). Total scores (min 0, max 40). up to 13 denote low level, 14–26 moderate, and 27–40 high stress. The PSS has been used in college student populations (Tavakoli et al., Citation2019). The PSS-10’s internal consistency in previous studies has ranged from .74 to .91 (Lee, Citation2012). In the current study, α = pre .81, post .85.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) is a seven-item questionnaire for assessing generalised anxiety disorder (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, Citation2006). The items are linked to the DSM-IV criteria, and a score of 10 or greater is considered to represent a cut point for identifying cases of General Anxiety Disorder (Spitzer et al., Citation2006). Respondents rate how often specific problems related to anxiety have bothered them over the preceding two weeks. The responses are scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with a sum score of max 21. Scores of less than 4 represent minimal symptoms, 5–9 mild, 10–14 moderate, and > 15 severe anxiety. The scale has shown excellent internal consistency (α = 0.92; Spitzer et al., Citation2006) including university students (Kim, Maleku, Lemieu, Du, & Chen, Citation2019). In this study, α = pre 0.86, post 0.85.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a depression instrument that scores each of the nine DSM-IV depression criteria from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Citation2001). A PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 has a sensitivity and specificity of 88% for major depression. A sum score (min 0, max 27) is then calculated. A total score of less than 4 represents none to minimal level of depressive symptomatology, 5–9 mild, 10–14 moderate, 15–19 moderately severe, and 20 or greater severe symptomatology. Internal consistency has been shown to be high in general, clinical (Kroenke et al., Citation2001, Citation2002) and university student populations (Tavakoli et al., Citation2019). In our sample, α = pre 0.79, post 0.86.

Process measures

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) measures mindfulness using 39 statements rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = rarely or never true, 5 = very often true or always true) (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, Citation2006). The FFMQ (scores ranging from 39–195) has five subscales: observing (FFMQ-Ob); describing (FFMQ-De); non-judging of inner experience (FFMQ-Nj); non-reactivity of inner experience (FFMQ-Nr); and acting with awareness (FFMQ-Aw). Higher scores indicate greater mindfulness skills. The FFMQ has an adequate internal consistency (Baer et al., Citation2008), and is a valid measure of mindfulness with university students (Baer et al., Citation2006; Carmody, Baer, Lykins, & Olendzki, Citation2009). Cronbach’s alpha for the total score was α = pre 0.90, post 0.93; for the subscales, it was α = pre 0.83, post 0.84 (observe), α = pre 0.93, post 0.91 (describe), α = pre 0.87, post 0.82 (act with awareness), α = pre 0.89, post 0.95 (non-judgement), and α = pre 0.82, post 0.88 (non-reactivity).

The Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth (AFQ-Y) measures psychological inflexibility, a construct referring to avoidance of thoughts and feelings (Greco, Lambert, & Baer, Citation2008). The AFQ-Y includes 17 statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = not at all true, 4 = very true). The AFQ-Y scores are obtained by summing all 17 items (min 0, max 68). Lower scores indicate better outcomes. The AFQ-Y was initially developed for use with children and adolescents. Following the example of Levin et al. (Citation2014), we used the AFQ-Y for the student population in this study. The AFQ-Y has shown adequate reliability and validity in samples of university students (Schmalz & Murrell, Citation2010). In the current study, α = pre 0.85. post 0.92.

The Engaged Living Scale (ELS) is a measure of the process of engaged living, choices we make about how we want to live our lives (Trompetter, Citation2014). This measure features two subscales, learning to identify values (Valued Living, ELS-VL) and living according to them (Life Fulfilment, ELS-LF). All items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree). Total scores can be calculated for each subscale and the main scale (min 0, max 80). Previous studies including students have shown that the ELS-16 presents adequate to good psychometric properties (Grégoire, Doucerain, Morin, & Finkelstein-Fox, Citation2021; Trindade, Ferreira, Pinto-Gouveia, & Nooren, Citation2016). In our sample α = pre 0.93, post 0.92. For the subscales, α = pre 0.90, post 0.89 (ELS-VL) and α = pre 0.87, post 0.86 (ELS-LF).

Participant satisfaction and motivation

The participants’ feedback was collected using a self-constructed feedback questionnaire. They rated their satisfaction with the intervention on a 10-point Likert scale, with 0 indicating very dissatisfied and 10 very satisfied. Participants were also asked if they would recommend the intervention to other international students, and they expressed their opinion on a 1–5 Likert scale (1 = would advise against it; 2 = would not recommend it; 3 = would recommend it with some reservations; 4 = would recommend it; 5 = would highly recommend it). Additional feedback from the participants was collected using a 1–5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), including questions related to the coaches and the workshop, a selection of yes and no questions about the skills learned during the workshop (e.g. Participating in the workshop has helped me cope better with issues that have been challenging to me earlier) and open-ended questions focusing on the perceived benefits (e.g. What did you find most helpful in the workshop?) and suggestions for improvements (e.g. If you would change anything about the workshop, what would it be?)

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS and Mplus, version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017). Descriptive statistics were carried out to provide an overview of the mean values and change scores from the pre- to post-measurements of the symptom and process measures. The within-group changes from the pre- to post-measurements were investigated using structural equation modelling (SEM). The analysis included all the participants who completed the pre-measurement (n = 53). Thus, the within-group changes were described using estimated mean values. In addition, within-group effect sizes (ESs) were reported using Cohen’s (Citation1988) d in order to obtain an estimation of the magnitude of the changes. An effect size of d = 0.20 was considered small, d = 0.50 medium, and d = 0.80 large. We investigated further clinical significance of the intervention by studying the number of students who reported moderate or higher levels of symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) at pre- and post-measurement (n = 47).

In addition, we conducted multiple (linear) regression analyses in SPSS (n = 47) to determine whether changes in the psychological flexibility measures (AFQ-Y, FFMQ, ELS) predicted changes in the symptoms of stress (PSS-10), depression (PHQ-9), and anxiety (GAD-7). Two separate analyses were performed. First, the total scores of the AFQ-Y, FFMQ, and ELS were used as independent (predictor) variables. Second, the subscales of the FFMQ and ELS were investigated as independent (predictor) variables. For the regression analyses, we selected only those process variables that significantly correlated (p < 0.05) with the symptom measures. We performed the regression analyses using the stepwise model and verified the results using the enter method. Both methods resulted in identical conclusions. Furthermore, we tested whether multicollinearity was a problem by calculating tolerance and variance inflation factors (VIF; Kutner, Neter, Nachtsheim, & Li, Citation2004). The selected variables did not represent a problem of multicollinearity, with VIF scores being under 3.0.

Results

Treatment adherence

As shown in , the attrition rate was relatively low. 11% of the participants discontinued the workshops (n = 6, out of 53), three gave no specific reason, whereas two reported a busy schedule. One participant interrupted their participation due to a high level of symptoms. About 83% of the participants attended four to five group meetings. Further, there was no trend indicating larger changes in the seven treatment groups towards the end of study period (from 2017 to 2019).

Severity of symptoms

At pre-measurement, approximately 87% (n = 46) of the students reported moderate to high stress; 40% (n = 21) moderate to severe anxiety (GAD-7); and 51% (n = 27) moderate to high depressive symptoms (PHQ-9). Approximately half of the students (51%) reported major level of depression (≥ 10).

Changes in symptoms and psychological flexibility

Significant decreases in all the symptom variables, stress, anxiety, and depression were found from the baseline to post-treatment (). According to effect size values, stress (PSS-10) showed a large decrease (d > 0.80), whereas the reductions in anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) were moderate (d > 0.50). For the process variables, we observed a significant and large decrease in psychological inflexibility (AFQ-Y), and moderate increases in total mindfulness skills (FFMQ) and in engaged living (ELS). Regarding the subscales, we observed a significant increase in four of five of the mindfulness subskills (FFMQ description, awareness, non-judgement, non-reacting). The subscale observing showed no change (). The change in non-judgement was moderate, while the changes in the other three scales were small. Regarding the subscales for the engaged living measure (ELS), there was a small effect in valued living (ELS-VL) and a moderate effect in life-fulfilment (ELS-LF).

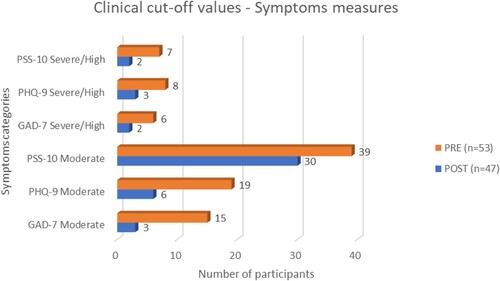

In addition, we investigated the clinical significance of the intervention by studying the number of students who reported moderate or higher levels of symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) at pre- and post-measurement (n = 47). Scores of 10 or greater in GAD-7 and PHQ-9 are considered to represent a reasonable cut point for identifying cases of General Anxiety Disorder (Spitzer et al., Citation2006), and for major depression (Kroenke et al., Citation2001). At post-intervention (n = 47) approximately 11% (n = 5) of the students reported moderate to high anxiety compared to 40% (n = 21) at the beginning of the intervention. Accordingly, 19% (n = 9) reported moderate to severe depression at the post-measurement compared to 51% (n = 27) at the pre-measurement (See ) and .

Figure 2. Clinical cut-off values of the symptom measures of stress (PSS-10), Depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) showing the decrease in symptoms at post intervention for the severe and moderate symptoms categories.

Table 3. Correlation between change score in symptom (anxiety, depression, stress) and process measures (valued living, psychological flexibility, and mindfulness skills) between pre and post intervention. Mean values for the change scores (pre to post) and standard deviations (SD) are also presented.

Table 4. Changes in outcome and process variables during the intervention (pre-post).

Students attending all five sessions of the workshops showed higher improvement compared to students who attended three or four sessions only. In our main outcome measure, PSS-10, the changes were as follows: three sessions (n = 8), mean change, m = 3.75; four sessions (n = 15), m = 4.53; five sessions (n = 24), m = 6.00. Similar trends were observed in our process measures: AFQ-Y, three sessions, m = 7.63; four sessions, m = 6.27; five sessions, m = 11.92; FFMQ, three sessions, m = 3.00; four sessions, m = 7.27; five sessions, m = 16.36; ELS, three sessions, m = 2.88; four sessions, m = 4.67; five sessions, m = 6.63.

Predictors of changes in symptoms

When investigating the predictors, only those psychological flexibility measures showing significant correlation with the changes in stress, depression, and anxiety were selected for the regression analysis (see ). In relation to perceived stress (PSS-10), we investigated the total change scores of the AFQ-Y, FFMQ, and ELS as predictors () and found two significant models. Changes in psychological inflexibility (AFQ-Y; Model 1: F (1,43) = 21.736, p < 0.001) made a significant contribution and explained 32% of the variance in changes of stress symptoms. The second model (F (2,42) = 14.390, p < 0.001), which included changes in mindfulness (FFMQ total), outlined an additional seven percent of the variance. In total, changes in these two process measures accounted for close to 40% of the variance in changes of the PSS-10. Two significant models (Model 1: F (1,43) = 15.416, p < 0.001; Model 2: F (2,42) = 12.033, p < 0.001) resulted from examining the changes in the subscales and including, in the analyses, the six scales that correlated significantly with changes in stress (). Changes in the mindfulness skill of non-judgement (FFMQ-Nj) explained 25%, and changes in the value subscale Valued living (ELS-VL) explained 10% of the changes in stress symptoms.

Table 5. Multiple regression analysis of intervention change scores.

Concerning changes in symptoms of depression (PHQ-9), we included the total scores of the ELS and FFMQ in the regression analysis and found that changes in values (ELS total) acted as a significant predictor (F (1,43) = 8.360, p = 0.006) and explained 14% of the variance in depression. After including the three subscales (ELS-VL, ELS-LF and FFMQ-Aw) that correlated moderately in the analyses, only changes in life fulfilment acted as a significant predictor (ELS-LF; F (1,45) = 6.889, p = 0.011), explaining 11% of the variance in depressive symptoms.

In terms of general anxiety (GAD-7), of the three total scores, only changes in the FFMQ total score was a significant predictor of the changes in anxiety (F (1,43) = 11.971, p = 0.001). Changes in the FFMQ total score explained nine percent of the variance in anxiety symptoms. Of all the subscales, only changes in the FFMQ-Acting with Awareness (Aw) was a significant predictor of the changes in anxiety (F (1,45) = 4.758, p = 0.034). Changes in the FFMQ-Aw explained nine percent of the changes in anxiety symptoms.

Participant satisfaction and motivation

The students evaluated their satisfaction with the workshop with a mean value of 8.57 (SD = 1.30) on a scale from 1 to 10 (positive). With a rating of at least three (“Would recommend it with some reservation”; 1–5 Likert scale), 83% (n = 39) of students were likely to recommend the intervention to other international students. Over half of them (55%, n = 26) would highly recommend the workshop to others (value 5 in 1–5 Likert scale). Those few students who recommended the intervention with some reservations, wished either more sessions or individual meetings instead of group sessions. All participants (n = 47) agreed that the workshop helped them cope better with previously challenging issues. Nearly all students (n = 46, 97.9%) reported that they had gained new perspectives that had helped them clarify certain issues in their life. Similarly, most students (n = 41; 87.2%) perceived that they felt more satisfied with their life and their well-being had increased. In terms of what was perceived helpful, the students reported, among others, the skill of learning different strategies to handle thoughts and emotions constructively, learning present moment skills, and clarification of values. Negative aspects and suggestions for improvement included the need for longer or additional sessions, smaller groups, and more discussions or group activities to improve the group cohesion.

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to examine whether a brief group-based ACT workshop was effective at decreasing psychological symptoms and increasing psychological flexibility skills among international students interested in dealing with daily stressors. Prior to the intervention, the participants reported high distress with nearly 90% of the students experiencing moderate to high stress, approximately 50% reporting moderate to high symptoms of depression, and 40% experiencing moderate to severe anxiety.

The ACT-based workshops significantly reduced psychological symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety. After the seven-week intervention period, we observed over 30% reduction in the number of students reporting either moderate or severe levels of symptoms of depression or anxiety. However, the current study did not include a control condition and the conclusion needs to be treated with caution. On the other hand, our results are congruent with earlier ACT-based studies reporting positive outcomes in general student (e.g. Grégoire et al., Citation2018; Levin et al., Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2020; Räsänen et al., Citation2016) as well as in international student populations (Muto et al., Citation2011; Xu et al., Citation2020). For example, our results were in line with the within-group effect sizes in the Levin et al. (2104) study (d = 0.81–0.97, vs. the current study, d = 0.63–0.94).

Second, we expected that the workshop would increase psychological flexibility skills among the students. This hypothesis was also supported. The five-week intervention decreased psychological inflexibility and enhanced mindfulness skills, specifically non-judging, suggesting that the intervention fostered a less negative evaluation of thoughts and feelings. The intervention increased engaged living, in particular, life fulfilment. This implies that the intervention was able to promote a more meaningful, values-oriented life, and a non-critical attitude. Earlier ACT-based studies have shown that the training of psychological flexibility and mindfulness skills can increase the ability to respond more adequately to stressful situations, which may lead to improvements in a wide range of mental health outcomes (see e.g. Danitz, Suvak, & Orsillo, Citation2016; Grégoire et al., Citation2018; Lee & Orsillo, Citation2014; Levin et al., Citation2014, Citation2016).

In addition, a clarification of values and increases in cognitive, emotional, and behavioural flexibility have been found to be partial mediators of the relationship between mindfulness training and symptom reduction (Carmody et al., Citation2009; Carmody & Baer, Citation2008). Accordingly, it has also been shown in a recent study by Grégoire et al. (Citation2021) that when students reported being more engaged in committed actions, they also reported lower distress and greater well-being. Our study corroborates these findings, suggesting that clarifying values and working on flexibility and mindfulness skills are associated with symptom reduction (Paliliunas, Belisle, & Dixon, Citation2018).

Moreover, we hypothesised that a decrease in psychological inflexibility and an increase in mindfulness and engaged living skills would predict decreases in psychological symptoms. We investigated significant predictors of changes in symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety and found that, in line with the findings of Masuda and Tully (Citation2012), psychological flexibility and mindfulness accounted for a unique variance in measures of distress. More precisely, our findings indicated that changes in psychological inflexibility and overall mindfulness skills predicted changes in perceived stress over the course of the intervention. However, change in psychological inflexibility was a stronger predictor of changes in stress than changes in overall mindfulness skills. When we investigated more closely specific sub skills as predictors, we found that changes in non-judgment (e.g. “I tell myself that I shouldn’t be thinking the way I’m thinking”) and valued living acted (e.g. “I know what motivates me in life”) as a significant predictor of stress. Conversely, while changes in overall inflexibility and mindfulness predicted changes in stress, they did not predict changes in depressive symptoms. Instead, changes in values and especially in value-based actions (e.g. “I make time for the things that I consider important”), acted as significant predictors of depressive symptoms. Changes in anxiety were predicted by changes in mindfulness skills, especially the skill acting with awareness (e.g. “I rush through activities without being really attentive to them”). These results suggest that changes in different psychological flexibility skills may predict changes in different kind of distress, which is congruent with Gallego, McHugh, Villatte, and Lappalainen (Citation2020) and Kinnunen, Puolakanaho, Tolvanen, Mäkikangas, and Lappalainen (Citation2020), who found that different aspects of mindfulness and psychological inflexibility may be related to different psychological outcomes. Overall, these findings suggest that enhancing skills to stay focused in the present moment and acquiring a non-judging attitude to one’s emotions and thoughts are associated with positive changes in anxiety and stress, whereas engaging more in meaningful actions may lead to changes in depressive symptoms. Thus, when experiencing stress and anxiety, students need to be trained to acquire an accepting stance toward their thoughts and feelings while they stay focused on the present moment, and to commit to value-based actions if the target is to alleviate mood. It is possible that psychological flexibility skills could be enhanced methods other than ACT. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of acceptance, mindfulness, and valued actions in psychological health of international students.

With regard to adherence to workshops, we observed a low drop-out rate of 11% among the international students in this sample. A similarly low drop-out rate (9%) was reported in an earlier study that employed a similar approach to university students (Räsänen et al., Citation2016). Importantly, the workshop was well received by the students, who evaluated their satisfaction with an average of 8.6 of a possible 10. In addition, all of them agreed that the workshop helped them cope better with previously challenging issues. Based on our findings including 28 nationalities, it may not be needed to make interventions or counselling more culturally appropriate for the diverse international student population, which was suggested by Forbes-Mewett (Citation2019). Our results, as well as participant feedback, show that a process-based ACT workshop combined with issues that international students perceive relevant can be effective and well received by the participants.

However, the present study does come up against several limitations, the most important being the lack of a control group, and lack of representativeness, as most participants were female university students (83%). Female students may experience higher levels of psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, than their male counterparts (e.g. Adlaf, Gliksman, Demers, & Newton-Taylor, Citation2001), and our results may reflect this. Moreover, the pre-measurement value of stress in the current study (PSS-10, m = 20.74) is comparable with the pre-measurement value of domestic students in the same university (m = 21.54).

The lack of a control group makes it impossible to draw firm causal conclusions. Without a control group, key threats to internal validity such as maturation, measurement-effect and regression toward the mean cannot be ruled out. Additionally, without a waitlist or alternative treatment comparison, it is impossible to unambiguously attribute the participants’ change to the ACT components. For example, the clinical skills of the coaches conducting the sessions, such as supportive listening, could have been sufficient to elicit change (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, Citation2015). The low number of interested students participating per semester did not allow us to create a control group condition. However, the authors have previously observed in a randomised controlled trial (offered to the domestic university students) that the change in stress (PSS-10) was small (d = 0.27) in the control condition receiving only some attention and repeated measurements. Thus, the research attention with repeated measures may possibly have had an impact on results in the current study. But, based on our earlier findings (Räsänen et al., Citation2016), we believe that this impact is significantly smaller compared to the changes in the current study (e.g. PSS.10, d = 0.27 vs. d = 0.94). In addition, we observed that the exposure to the intervention was related to magnitude of changes in stress. The positive effects of the intervention could be affected by the researcher’s positive allegiance to the investigated treatment model. Thus, the results could be associated with or influenced by the researchers’ enthusiasm for the ACT-model. However, there are mixed results of allegiance bias, and the bias is mostly directed to the randomised controlled trials when comparing the intervention to other treatment models (Wilson, Wilfley, Agras, & Bryson, Citation2011). Furthermore, the participants joined the study voluntarily. Thus, the participants selected themselves to the study group, and there is a possibility of self-selection-bias. For example, those students who were highly motivated to make changes participated in the study. Limited number of questions about negative aspects of the workshop is also a limitation. Additionally, the participants may have responded to the post-treatment questionnaires in a socially desirable manner. More studies with larger samples are needed to investigate whether our findings can be generalised to the overall international student population. The relatively low uptake rate of students joining the intervention may be since international students were adapting to the new cultural and academic environment, reducing their willingness to participate in extra activities. Some students might also be more skeptical towards psychological interventions due to their cultural background.

Conclusion

The current study suggested that it is possible to help international students who display high levels of psychological symptoms by offering them a brief workshop with the aim of increasing their psychological flexibility skills and significantly impacting their mental health outcomes. Therefore, emphasis needs to be placed on fostering students’ acceptance skills, for example, skills to handle their unpleasant thoughts and emotions, assisting them in exploring and discovering what is important to them in life, and encouraging them toward meaningful actions. Learning these skills should be integrated into both the curriculum and counselling services targeting international students in the future so as to increase the likelihood of better adaptation and coping in the new cultural and academic environment.

Data availability statement

The data of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the international students who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Francesca Brandolin

Francesca Brandolin, doctoral researcher at the Department of Psychology, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. A licensed clinical psychologist, in Italy. Previous studies are bachelor in Psychological Sciences and Techniques and an international master’s degree in Clinical Psychology. During the last year of the master and post-graduate internship she got involved in different research projects dealing with brief psychological interventions for student’s wellbeing and stress management, and virtual reality (VR) interventions for social anxiety and public speaking at the department of Psychology, University of Jyväskylä. Her ongoing research in the past six years involve the efficacy of a brief low-threshold workshop on the distress of international students, both delivered face-to-face or online through videoconference during the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, she has the first two articles of her dissertation accepted for publication and the third one in submission. Brandolin is an active member in the Association for Contextual Behavioural Science.

Päivi Lappalainen

Päivi Lappalainen, PhD. PostDoctoral Researcher has published over 40 papers in the area of web-based and mobile eHealth interventions based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). She has also been the digital content lead (psychology) for 18 web-based and mobile interventions, including web and mobile applications for preventing stress and promoting well-being of working age individuals, depressive symptoms, insomnia and chronic conditions. Therefore, she is one of the world leading experts in the field of digital ACT interventions. During the last 11 years she has been involved in and managed research projects dealing with web-based and mobile interventions at the department of Psychology, University of Jyväskylä. Her ongoing research projects involve the efficacy of a web-based psychological intervention for parents experiencing stress and burnout, a web-based psychological rehabilitation programme for working age individuals suffering from depressive symptoms, and virtual reality (VR) interventions for social anxiety and public speaking. Dr. Lappalainen has been in charge of several randomised controlled trials investigating digital solutions for people of all ages. Currently, she is co-supervising three doctoral students in psychology and several Bachelor and Master’s students. Lappalainen is an active member in the Association for Contextual Behavioural Science.

Simone Gorinelli

Simone Gorinelli, doctoral and project researcher at the Department of Psychology, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. His research focuses on the effectiveness of Virtual Reality (VR) exposure, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and Relational Frame Theory (RFT) training on social and public speaking interaction of university students aimed to increase performing skills of university students through an integration between Psychology and Technology. Project researcher in an international research project VRperGENERE, in which the aim is to reduce intimate partner violence through the deployment of cost-effective prevention and rehabilitation tools based on immersive Virtual Reality (VR). Co-facilitator in the Student Compass wellbeing group workshop for international students.

Joona Muotka

Joona Muotka, university lecturer and researcher specialised in statistics and research methods for social sciences at the Department of Psychology, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. He collaborated in many research projects and papers in various area of psychology such as: MOTILEAD - The importance of leadership motivation in the career paths and well-being of highly educated people, Reducing the workload and usefulness of remote team meetings with physiological metrics, STAIRWAY – From Primary School to Secondary School/Youth COMPASS study promoting learning, school well-being and successful educational transitions.

Panajiota Räsänen

Panajiota Räsänen, Project Researcher (student wellbeing) and Student Life’s Study- and Wellbeing expert at the Department of Psychology, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She has been actively involved in the development and implementation of the innovative SL’s three-step wellbeing support model offered at JYU to students. She has been training and supervising over 250 psychology Master’s level students to work as well-being coaches in delivering an acceptance and mindfulness-based intervention called The Student Compass. The programme is a permanent service of the university and part of Student Life’s wider cluster of three-step wellbeing support. Her research primarily focuses on the area of brief, blended Acceptance and Commitment Therapy interventions for university students to enhance their psychological, emotional, social wellbeing and alleviate depression, anxiety, and stress. One recent collaboration involves Integra, which is a project funded by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. Integra is an educational model that integrates university language and content studies for immigrants who have completed or are qualified for higher education. Räsänen offers psychosocial workshops and counselling to the programme’s participants.

Raimo Lappalainen

Raimo Lappalainen, Ph.D. in clinical psychology. Professor in clinical psychology and psychotherapy at the Department of Psychology, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. A licensed psychologist and psychotherapist. He has acted as the vice head and the head of the Department of Psychology between years 2008-2013. He has over 25 years’ experience of Cognitive Behavioural Therapies (CBT) with expertise especially in the third wave CBT, acceptance and value –based interventions. Author of more than 100 scientific articles and books. He has special expertise in applying and constructing web- and mobile-based psychological interventions. His main research interests are development of brief psychological interventions, including web- and mobile -based interventions for wellbeing and wellness management. Received the Public Information Award (2015) by the Jyväskylä University Foundation for his research group’s achievement of developing web and mobile interventions.

References

- Adlaf, E., Gliksman, L., Demers, A., & Newton-Taylor, B. (2001). The prevalence of elevated psychological distress among Canadian undergraduates: Findings from the 1998 Canadian campus survey. Journal of American College Health, 50, 67–72.

- Aguiniga, D. M., Madden, E. E., & Zellmann, K. T. (2016). An exploratory analysis of students’ perceptions of mental health in the media. Social Work in Mental Health, 14(4), 428–444.

- A-Tjak, J. G. L., Davis, M. L., Morina, N., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2015). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for clinically relevant mental and physical health problems. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(1), 30–36.

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., … Williams, J. M. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342.

- Brown, J., & Brown, L. (2013). The international student sojourn, identity conflict and threats to well-being. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 41(4), 395–413.

- Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(1), 23–33.

- Carmody, J., Baer, R. A., Lykins, E. L. B., & Olendzki, N. (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 613–626.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

- Cohen, S., & Williamson, C. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan, & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology (pp. 31–67). Newbury Park: Sage.

- Danitz, S. B., Suvak, M. K., & Orsillo, S. M. (2016). The mindful way through the semester: Evaluating the impact of integrating an acceptance-based behavioral program into a first-year experience course for undergraduates. Behavior Therapy, 47(4), 487–499.

- Forbes-Mewett, H. (2019). Mental health and international students: Issues, challenges and effective practice. International Education Association of Australia (IEAA). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334721342_Mental_Health_and_International_Students_Issues_challenges_effective_practice.

- Forbes-Mewett, H., & Sawyer, A.-M. (2016). International students and mental health. Journal of International Students, 6(3), 661–677.

- Gallego, A., McHugh, L., Villatte, M., & Lappalainen, R. (2020). Examining the relationship between public speaking anxiety, distress tolerance and psychological flexibility. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 16, 128–133.

- Gloster, A. T., Walder, N., Levin, M., Twohig, M., & Karekla, M. (2020). The empirical status of acceptance and commitment therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 181–192.

- Greco, L. A., Lambert, W., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Psychological inflexibility in childhood and adolescence: Development and evaluation of the avoidance and fusion questionnaire for youth. Psychological Assessment, 20(2), 93–102.

- Grégoire, S., Doucerain, M., Morin, L., & Finkelstein-Fox, L. (2021). The relationship between value-based actions, psychological distress and well-being: A multilevel diary study. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 20, 79–88.

- Grégoire, S., Lachance, L., Bouffard, T., & Dionne, F. (2018). The Use of acceptance and commitment therapy to promote mental health and school engagement in university students: A multisite randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 49(3), 360–372.

- Hauschildt, K., Gwosc, C., Netz, N., & Mishra, S. (2015). Social and economic conditions of student life in Europe: Synopsis of indicators. Eurostudent V 2012–2015. W. Bertelsmann Verlag. https://www.eurostudent.eu/download_files/documents/EVSynopsisofIndicators.pdf

- Hayes, S. C. (2019). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Towards a unified model of behavior change. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 226.

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Howell, A. J., & Passmore, H. A. (2019). Acceptance and commitment training (ACT) as a positive psychological intervention: A systematic review and initial meta-analysis regarding ACT’s role in well-being promotion among university students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(6), 1995–2010.

- Katajavuori, N., Vehkalahti, K., & Asikainen, H. (2021). Promoting university students’ well-being and studying with an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)-based intervention. Current Psychology, 40, 1–13.

- Kim, Y. K., Maleku, A., Lemieu, C., Du, X., & Chen, Z. (2019). Behavioral health risk and resilience among international students in the United States: A study of sociodemographic differences. Journal of International Students, 9(1), 282–305.

- Kinnunen, S. M., Puolakanaho, A., Tolvanen, A., Mäkikangas, A., & Lappalainen, R. (2020). Improvements in mindfulness facets mediate the alleviation of burnout dimensions. Mindfulness, 11(12), 2779–2792.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2002). The PHQ-15: Validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(2), 258–266.

- Kutner, M. H., Neter, J., Nachtsheim, C. J., & Li, W. (2004). Applied linear statistical models (5th ed.). Boston.: McGraw- Hill Irwin.

- Lee, E. H. (2012). Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research, 6(4), 121–127.

- Lee, J. K., & Orsillo, S. M. (2014). Investigating cognitive flexibility as a potential mechanism of mindfulness in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45(1), 208–216.

- Levin, M. E., Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., & Seeley, J. R. (2016). Web-Based self-help for preventing mental health problems in universities: Comparing acceptance and commitment training to mental health education. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 207–225.

- Levin, M. E., Krafft, J., Seifert, S., & Lillis, J. (2020). Tracking valued and avoidant functions with health behaviors: A randomized controlled trial of the acceptance and commitment therapy matrix mobile app. Behavior Modification, doi:10.1177/0145445520913987

- Levin, M. E., MacLane, C., Daflos, S., Seeley, J., Hayes, S. C., Biglan, A., & Pistorello, J. (2014). Examining psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic process across psychological disorders. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3(3), 155–163.

- Lu, S. H., Dear, B. F., Johnston, L., Wootton, B. M., & Titov, N. (2014). An internet survey of emotional health, treatment seeking and barriers to accessing mental health treatment among Chinese-speaking international students in Australia. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 27(1), 96–108.

- Masuda, A., Hayes, S. C., Fletcher, L. B., Seignourel, P. J., Bunting, K., Herbst, S. A., … Lillis, J. (2007). Impact of acceptance and commitment therapy versus education on stigma toward people with psychological disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(11), 2764–2772.

- Masuda, A., & Tully, E. C. (2012). The role of mindfulness and psychological flexibility in somatization, depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress in a nonclinical college sample. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 17(1), 66–71.

- Mori, S. (2000). Addressing the mental health concerns of international students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78(2), 137–144.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2017). Mplus user's guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user's guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Muto, T., Hayes, S. C., & Jeffcoat, T. (2011). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy bibliotherapy for enhancing the psychological health of Japanese college students living abroad. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 323–335.

- Paliliunas, D., Belisle, J., & Dixon, M. R. (2018). A randomized control trial to evaluate the Use of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to increase academic performance and psychological flexibility in graduate students. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 11(3), 241–253.

- Pistorello, J. (Ed.). (2013). Mindfulness and acceptance for counseling college students: Theory and practical applications for intervention, prevention, and outreach. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Räsänen, P., Lappalainen, P., Muotka, J., Tolvanen, A., & Lappalainen, R. (2016). An online guided ACT intervention for enhancing the psychological wellbeing of university students: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 78, 30–42.

- Rice, K. G., Choi, C.-C., Zhang, Y., Morero, Y. I., & Anderson, D. (2012). Self-Critical perfectionism, acculturative stress, and depression Among international students. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(4), 575–600.

- Rosenthal, D. A., Russell, V. J., & Thomson, G. D. (2006). A growing experience: The health and well-being of international students at The University of Melbourne. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne.

- Ruiz, F. J. (2014). The relationship between low levels of mindfulness skills and pathological worry: The mediating role of psychological inflexibility. Anales de Psicologia, 30(3), 887–897.

- Ruiz, F. J., & Odriozola-González, P. (2015). Comparing cognitive, metacognitive, and acceptance and commitment therapy models of depression: A longitudinal study survey. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18, E39.

- Russell, J., Rosenthal, D., & Thomson, G. (2010). The international student experience: Three styles of adaptation. Higher Education, 60(2), 235–249.

- Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Deumert, A., Nyland, C., & Ramia, G. (2008). Loneliness and international students: An Australian study. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12(2), 148–180.

- Schmalz, J. E., & Murrell, A. R. (2010). Measuring experiential avoidance in adults: The avoidance and fusion questionnaire. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 6(3), 198.

- Shadowen, N. L., Williamson, A. A., Guerra, N. G., Ammigan, R., & Drexler, M. L. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among international students: Implications for university support offices. Journal of International Students, 9(1), 129–149.

- Sommers-Flanagan, J., & Sommers-Flanagan, R. (2015). Clinical interviewing (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

- Stabbe, O. K., Rolffs, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2019). Flexibly and/or inflexibly embracing life: Identifying fundamental approaches to life with latent profile analyses on the dimensions of the hexaflex model. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 12, 106–118.

- Strosahl, K. D., Robinson, P. J., & Gustavsson, T. (2012). Brief interventions for radical change: Principles and practice of focused acceptance and commitment therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Tavakoli, N., Broyles, A., Reid, E. K., Sandoval, J. R., & Correa-Fernández, V. (2019). Psychological inflexibility as it relates to stress, worry, generalized anxiety, and somatization in an ethnically diverse sample of college students. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 11, 1–5.

- Trindade, I. A., Ferreira, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Nooren, L. (2016). Clarity of personal values and committed action: Development of a shorter engaged living scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 258–265.

- Trompetter, H. R. (2014). ACT with pain: Measurement, efficacy and mechanisms of acceptance & commitment therapy. Enschede: Universiteit Twente.

- Wilson, G. T., Wilfley, D. E., Agras, W. S., & Bryson, S. W. (2011). Allegiance bias and therapist effects: Results of a randomized controlled trial of binge eating disorder. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(2), 119–125.

- Xu, H., O’Brien, W. H., & Chen, Y. (2020). Chinese international student stress and coping: A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 135–141. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.12.010