ABSTRACT

The current study explored the experiences of Asian International Students (AISs) in terms of mental health, disclosure and help-seeking within Higher Education in Scotland, UK. A qualitative study using individual semi-structured interviews with AISs (n = 20) was used and an inductive thematic approach to analysis was conducted. Three major themes were developed: (1) Negative beliefs, stigma and fear of judgment, (2) Adaptation and acculturation difficulties and (3) Barriers in communication, social disconnection and loneliness. Supporting AISs involves challenging negative judgements surrounding mental health, increasing mental health literacy and addressing barriers that may inhibit disclosure and help-seeking behaviour. The need for culturally sensitive mental health practitioners and awareness of diverse understandings of mental health issues is essential to improving support for AISs.

Introduction

The UK has been highly successful in attracting international students; over a third of non-European Union international students being from Asian countries (Universities UK, Citation2022). Asian International Students (AISs) not only contribute a significant proportion of the income of UK Higher Education (HE) institutions, but also enrich the diversity of the HE student population (Lomer, Citation2023). They often strengthen the workforce as they can bring a unique skillset, fresh outlook and cultural perspective (Huang et al, Citation2020). Many studies have documented the various psychosocial, academic and financial challenges faced by AISs in the HE environment (Dodd et al., Citation2021; Furnham et al., Citation2011; Ryan et al., Citation2010). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated stressors facing AISs in both reducing student mobility and increasing concerns about health, safety and mental wellbeing (Chen et al., Citation2020; Gui et al., Citation2023; Holliman et al., Citation2023; Koo & Nyunt, Citation2023; Maleku et al., Citation2021; Mok et al., Citation2021; Rzymski & Nowicki, Citation2020). However, to date, no research has specifically explored the unique perspectives and understandings of mental health, disclosure and help-seeking behaviours of AISs studying in Scotland.

Scotland’s HE sector is one of the best in the world with three of the world’s top 200 universities being in Scotland. Scotland’s universities are also amongst the most multicultural in the world. Around 31% of students in Scotland are from overseas (HESA, Citation2023). HE is devolved to the Scottish Parliament, with funding and policy decisions affecting HE taken primarily by the Scottish Government, Scottish Parliament and Scottish Funding Council. Scottish universities are internationally regarded for enhancement-led teaching and this ethos has been applied to work on mental health in recognition of the diversity of the student population (Scottish Government, Citation2018). While universities have sought to support students with committed student support services and counselling teams, over the past 10 years there has been a significant increase in the number of students disclosing mental health problems to HE institutions (Maguire & Cameron, Citation2021); particularly among international students who have tended to be most in need yet least likely to seek help (Cao et al., Citation2021; Maeshima & Parent, Citation2022).

Unique sources of stress of international students

Psychological distress has been commonly identified among HE international students (Cooke et al., Citation2006; Naylor, Citation2022), yet relatively little research has been carried out with AISs studying in the UK (Lu et al., Citation2014; Tang et al., Citation2012). Besides the normal developmental concerns that every student may have, AISs studying in Western countries are likely to experience acculturative stress (Kristiana et al., Citation2022; Lam et al., Citation2006; Lu et al., Citation2014; Soorkia et al., Citation2011; Tang et al., Citation2012). A systematic review on the psychological wellbeing of East AISs confirmed this finding, although of the 18 studies reviewed the vast majority were conducted in the US and no UK studies were included (Li et al., Citation2014). AISs may encounter a range of acculturative stressors, such as language difficulties, intensified academic stress associated with academic adaptation, social isolation and/or having to form and maintain new social networks, financial and practical difficulties, homesickness and perceived discrimination (Cao et al., Citation2021; Smith & Khawaja, Citation2011; Wong et al., Citation2014; Zhang & Brunton, Citation2007). These stressors are likely to have an adverse impact on AISs’ mental health and wellbeing. For example, previous research has demonstrated an association between acculturative stress and depression in AISs (Pan et al., Citation2007). Existing studies have also found that the level of acculturation is positively associated with psychological help-seeking attitudes (Miller et al., Citation2011; Sun et al., Citation2016), and length of stay in the host country is positively correlated with the level of acculturation (Kuo & Roysircar, Citation2006).

Disclosure and helping-seeking

Disclosure is a multidimensional construct, including the amount, depth, honesty, intent and valence of information shared about one’s mental health challenges. Weighing up the costs and benefits of disclosure and obtaining peer support through the disclosure process has been found to be important in how it is experienced (Zhang & Jung, Citation2017). Yet, limited research has examined mental health disclosure or help-seeking among AISs studying in the UK. Despite AISs having been identified as a high-risk group for developing psychological distress (Han et al., Citation2013; Lu et al., Citation2014), wellbeing services have been reported to be significantly underused by this population (Cheng et al., Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2013). Relative to domestic students, AISs have been found to have lower rates of mental health care utilisation yet higher rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and completed suicide (Chen et al., Citation2019; McKay et al., Citation2023). Mental health literacy, which is defined by Jorm et al. (Citation1997, p. 182) as “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management or prevention”, is commonly found to be a barrier to disclosure and help-seeking among university students (Furnham et al., Citation2011; Gorczynski et al., Citation2017). AISs appear to have low levels of mental health literacy, according to Westernised measures that tend to focus on classification and diagnostic categories, which could be explained by their diverse cultural values and beliefs surrounding mental health (Altweck et al., Citation2015; Soorkia et al., Citation2011; Tang et al., Citation2012). For example, it has been reported that Asian people’s values advocate emotional self-control, which has been identified by researchers as one of the most salient dimensions in Asian people’s values that might lead to negative attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help (Lee et al., Citation2014; Soorkia et al., Citation2011). AISs who adhere to this value may not be comfortable with expressing feelings and emotions and view emotional inhibition as a virtue (Kim & Omizo, Citation2003; Wong et al., Citation2014; Zhang, 2017). This may lead to more self-reliant ways of dealing with mental health problems and the avoidance of personal disclosure (Carr et al., Citation2003; Winter et al., Citation2017).

Other cultural factors that may inhibit mental health help-seeking include lack of confidence in English proficiency, fear of burdening others with personal problems and tendencies to somatise psychological problems (Chen et al., Citation2019; Ra & Trusty, Citation2015; Smith & Khawaja, Citation2011). In addition to cultural factors, several systemic factors may also be inhibiting the accessibility of existing mental health support to AISs including lack of awareness on how to access new systems of support and lengthy waiting times for gaining therapeutic input (Barletta & Kobayashi, Citation2007; Russell et al., Citation2008; Zhai & Du, Citation2020). Of the research conducted to date, this has largely focused on international students studying in the US and Australian context; no research to date has explored AIS studying in the Scottish context.

The current study

The current study aimed to gain in-depth insights into the perspectives of AISs in terms of their understandings of mental health, experiences of disclosure and help-seeking while studying in Scotland, UK. The research questions explored were as follows:

What is distinctive about AIS’s understandings of mental health?

What factors influence AIS’s disclosure of mental health problems?

What factors influence/inhibit AIS’s ability to seek help within HE?

How can HE institutions develop more appropriate services for AIS’s experiencing MHPs?

Method

An inductive, qualitative design with semi-structured, individual interviews was used in accordance with a pragmatist methodology (Narey, Citation2017). Utilising a pragmatic methodology helps remove the constraints and rigidity often associated with adherence to pure methodologies (Johnson et al, Citation2017 ). Pragmatism helped the research team to effectively explore the manifold and multiplicative nature of international student mental health issues in order to address the research questions (Clarke & Visser, Citation2019).

Ethics

The research was carried out in accordance with the British Psychological Society’s ethical code of conduct (BPS, Citation2021) for research involving humans, and was ethically approved by the University Ethics Committee. Given the sensitive nature of discussing mental health issues within the current study, training on researching sensitive topics, handling distress and duty of care was provided to the interviewers from the research lead (Nabi et al., Citation2019). In the event of conducting the research, no ethical concerns were raised. The research team held regular reflexive meetings to discuss the conduct and process of the research and debrief among the team (MacIntyre et al., Citation2019a). This helped the team build a supportive infrastructure and trusting relationships for discussing sensitive and/or ethical issues throughout the conduct of the study.

Participants

A purposive sample of participants (n = 20) was obtained whereby the data collection process was monitored according to pragmatic grounds (Morgan, Citation2007; Robinson, Citation2014). As is recommended for interview research that has an ideographic aim (Malterud et al., Citation2016), this sample size was considered sufficient for individual participants to have a locatable voice within the study, allowing for an intensive thematic analysis of each case to be conducted. Participants were considered eligible for the study if they were: aged 18 or over; an AIS; studying full-time at the HE institution in Scotland; lived in the UK for at least 3 months; scored 5.5 (modest) or above on the International English Language System; and were able to provide informed consent to their participation in the study. The mean age of the participants was 25 (SD = 3.72). There was a gender split of 10 females to 10 males. Participants’ ethnic origin included China, India, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia (see ).

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Recruitment and procedure

Participants were recruited through adverts for the study which were posted on mail boards around campus, social media platforms and websites including WeChat, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. The recruitment period for the study commenced from November 2019 to February 2022. Given that data collection were conducted prior and throughout the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, the research team worked in accordance with social distancing protocols ensuring that participants were able to engage in online interviews while restrictions were in place (Lobe et al., Citation2020). Those who responded to study advertisements contacted the chief investigator (NC) through their university contact details to convey their interest in the study. Potential participants were offered the opportunity to ask questions about the study. An initial screening interview with one of the chief investigators (NC, XL and SK), each of whom were also trained mental health practitioners. The CORE-10 (Barkham et al, Citation2013), which is mental health monitoring tool with items covering anxiety, depression, trauma, physical problems, functioning and risk to self, was also conducted with each participant prior to engaging in the qualitative interview. The aim here was to safeguard any concerns raised concerning mental health (e.g. risk to self) during the screening interview; appropriate sign-posting to mental health advice and support was to be offered in such instances. In the event, all participants who were pre-screened were then interviewed for the study with no safeguarding and/or issues of risk identified. With permission from participants, their contact details were forwarded on to the research interviewer. The research interviewer then contacted the participant by email to discuss the study and their participation. A participant information sheet was then sent electronically to each participant; each of whom were given a period of a week to read information and to ask any questions, to ensure informed consent. Participants were then sent a consent form to complete and a suitable time and date to conduct the interview was arranged. All one-to-one interviews were conducted either in a safe and secure office in the University (n = 10) during regular working hours or through an online interview (N = 10) in accordance with social distancing regulations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interview schedule

Semi-structured, individual interviews were conducted with an interview schedule which consisted of 11 open-ended questions which were developed by the research team in order to address the aims of the research and were informed by earlier research. The schedule questions were informed by previous research literature, and developed in partnership with an international student stakeholder group. This stakeholder group included AISs who were undertaking research concerning student mental health and also had lived experience of some of challenges associated with studying abroad. The questions developed were piloted before agreement of the final interview schedule. It included questions which aimed to explore participants’ experiences of mental health, help-seeking, disclosure and help seeking behaviour. For example, “If you were to experience mental health issues, do you feel you could talk to someone about it?” and “What do you think others might think about you going to seek help?”.

Prior to commencing interviews, audio recording equipment was tested to ensure both interviewee and interviewer voices were audible. Upon conclusion of the interviews audio equipment was switched off and participants received written debriefs and an online £20 gift voucher as a thank you for their participation. Interviews ranged from 28 minutes to 1 hour and 13 minutes (mean of 59 minutes, SD = 23.55). Audio-recorded interviews were individually transcribed in full verbatim. The primary interest was in the content of the interviews, therefore it was sufficient to transcribe what was being said (the words), although selective transcription notation was found to be useful. This allowed inclusion of non-verbal communication and behaviour of the participants during the interviews that may have been relevant in the wider analysis of the research findings. Having conducted 18 interviews, the research team engaged in reflexive meetings in order to agree on the final themes. The research team agreed to commence with a further two interviews in order to substantiate the themes that had been developed (Ando et al., Citation2014; Braun & Clarke, Citation2019).

Analysis

Quality criteria were used for the reporting of the qualitative data (Shaw et al., Citation2019) to improve the transparency, trustworthiness, quality and credibility of the data collection and analytical process (Nowell et al., Citation2017). Thick contextual descriptions of the interview process were recorded by interviewers upon completion of each interview and discussed at reflexive meetings with the research team (Amin et al., Citation2020). This included recording and discussing initial perceptions, beliefs, interests, processes and even choices made throughout the research process (Moravcsik, Citation2014). The research team maintained an audit trail of the research process logging details of methodological decisions and the daily logistics of the research; this information also further informed the transparency of analytical process from the development of codes into themes (Shaw et al., Citation2019).

The data were analysed in accordance with an inductive reflexive thematic analysis (Braun et al., Citation2014; Braun & Clarke, Citation2021) which has stemmed from earlier work reporting on a thematic approach to qualitative analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Citation2012). In using an inductive reflexive thematic approach, the research team sought to derive meaning and create themes from the qualitative data without preconceptions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, Citation2023); this helped in addressing the exploratory nature of the study. This approach is a useful method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns within data through the use of an in-depth, description of themes. First, this involved becoming closely familiar with the data by reading and re-reading the interview transcripts. Following this close reading, initial codes were generated through focusing on what the participants were saying in relation to their understandings and experiences of mental health, disclosure and help-seeking behaviour. This consisted of identifying meaningful extracts and codes accordingly. At the end of this step, the codes were organised into preliminary themes that seemed to say something specific in relation to the research questions. The data associated with each preliminary theme was read and re-read and considered as to whether it really did support it. The themes were then examined in order to ascertain whether they worked in the context of the entire data set. The themes were then refined; all the data relevant to each theme were extracted and a process of defining and naming the master themes commenced (Braun & Clarke, Citation2018). Each master theme was actively created by the lead qualitative researcher. Each theme unites data that, captured implicit meaning beneath the data surface (Braun et al., Citation2014; Braun & Clarke, Citation2020).

The final strategy adopted was cross-checking of preliminary themes developed by the lead researcher by the co-researchers who also had expertise in qualitative research. Themes were discussed among the research team and the wider student stakeholder group in a collaborative and reflexive manner, designed to develop a richer more nuanced understanding of the data. Reflexivity throughout the research process was adopted through the researchers maintaining reflective journals (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019) and by the research team holding regular reflexive meetings. Through these processes, the research team was able to embrace researcher subjectivity as being equally key as the data generated in developing the themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021; MacIntyre et al., Citation2019a). This procedure resulted in three master themes that addressed the aims of the study and were present within all 20 interviews.

Findings

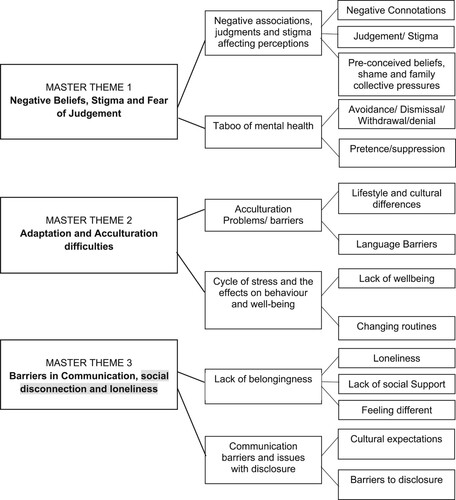

The three master themes identified were: (1) Negative beliefs, stigma and fear of judgment, (2) Adaptation and acculturation difficulties and (3) Barriers in communication, social disconnection and loneliness (see ).

Negative beliefs, stigma and fear of judgement

When describing their understandings of mental health, all the participants emphasised the negative connotations and perceptions that often surround their understandings of mental health. Mental health was largely associated with negative beliefs such as “weakness” (Jenny), “ failure” (Jim), “being mad” (Alan), “it’s a taboo” (John) or as “bad emotions” (Vivian). The sense that it was something “shameful” (Eric) and “frowned upon and shoved under the rug” (Jill) was widely acknowledged, and often internalised, among the participants. All participants described how studying abroad had presented challenges to their mental health, yet they expressed their concerns about disclosing such difficulties through fear of being “negatively judged” (James) by their peers in their host country (Scotland) and by their social circles (Asian friends and family) back home through “loss of face” (John). Jack described his personal thoughts and fears about acknowledging and addressing his mental health issues:

I didn’t perceive that was problematic at all. In fact, I think I was scared to seek help, that I was scared to be aware of the problem … I worried how others would react (Jack).

Our culture, we do not have the environment that encourages people to have a talk with other people, you know, because we think it is very private (May).

I think if I go to seek help … I’m just bringing up some, small issue … I’m making it look like that is quite a big problem. Why do that when everyone here is going through the same thing? (Emily).

Adaptation and acculturation difficulties

Whilst discussing the arising and/or ongoing mental health challenges experienced by the participants throughout their adaptation to studying and living in Scotland, several overlapping issues surrounding their transition to the cultural, lifestyle and social differences were highlighted. Upon reflecting on their earlier memories in Scotland, most participants could relate to feelings of uncertainty and unfamiliarity, seeming as though “everything has changed” (Eric). The noticeable difference in the culture between their home country and Scotland was observed by Alisha:

The culture tends to get very individualistic … you just go around, do your own thing … some people like that lifestyle, or they get used to it … but for some people it just doesn’t work out … It’s been hard for me (Alisha).

It’s just new to me, as in the university actually caring about people’s personal lives … It’s not something I have experienced before (James).

I don’t even know where to start … I don’t even know what it is … they are supposed to help you, giving advice to us … I’m afraid to go, cause I don’t know what to expect … it’s just different to what I know (Emily).

Barriers in communication, social disconnection and loneliness

A prominent factor found to inhibit participants from disclosing their problems and seeking help was their experience of communication barriers; both verbal and non-verbal communication issues were emphasised. Alan described his internal struggles associated with the language barrier inhibiting his ability to properly convey his feelings in English, thus contributing to his hesitation about expressing his mental health issues:

You are very shy, even though you know English, you don’t know how to express your feelings … so sometimes it will be very embarrassing. I don’t know how to say it (Alan).

I don’t feel the same, because when I switch my language to English, I am another person … I am not who I was before because of another language. It’s then hard to say what I feel (Eric).

I don’t know, I cannot engage in it … after all I am a Chinese student … and I don’t know the culture … I just listening and at that moment I feel very lonely because I cannot engage to the talking (May).

In the past I was scared to ask other people questions … I tried to solve the problems on my own and then I found that I cannot … I tried and tried my best to avoid contact with other people … I got really lonely and depressed (May).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to provide an in-depth exploration of the unique perspectives and experiences of AISs studying in Scotland; specifically, concerning their understandings of mental health, disclosure and help-seeking behaviour within HE institutions in Scotland. Negative beliefs, stigma and fear of judgement towards mental health as a taboo issue was evident among AISs’ accounts. The stereotypes and pre-conceived negative beliefs surrounding mental health as a form of weakness and as something shameful were widely acknowledged and often internalised by AISs in the study. These findings are consistent with previous research which has found that students from ethnic minorities are less likely to seek help for mental health issues due to fear of negative judgement and stigma (Heath et al., Citation2016; Maeshima & Parent, Citation2022; Soorkia et al., Citation2011). Specifically, adherence to traditional Asian cultural values of a collectivist nature advocates emotional self-control and humility, which has been found to negatively correlate with help-seeking intentions and attitudes (Bathje et al., Citation2014; Ma et al., Citation2020). In relation to the current study, this could suggest that participants who referred to their mental health concerns as a burden and shameful, considered help-seeking as a possible form of self-expression, which counteracts their belief of the need to be self-restrained, therefore attaching a high level of stigma against it (Constantine et al., Citation2005; Liao et al., Citation2023; Vogel et al., Citation2017; Wong et al., Citation2014; Yakunina & Weigold, Citation2011). It is worth considering how this may also have impacted on AISs’ ways of coping, for example, through keeping problems to themselves, suppression, withdrawal and denial, which have been found in previous research to impair mental health, increase psychological distress and contribute towards feelings of vulnerability (Ra & Trusty, Citation2015). These findings suggest that seeking to create a stigma-free environment among community of AISs could be a focus of mental health outreach within HE institutions (Glass & Westmont, Citation2014; Masuda & Boone, Citation2011; Slaten et al., Citation2016). The current findings reveal that perceived personal weakness, shame (to self and family), fear of judgement and collective pressures to succeed academically may be core features of participants’ experiences of stigma surrounding mental health challenges (Heath et al., Citation2016; Maeshima & Parent, Citation2022; Pimenta et al., Citation2021). Gaining insight from lay experiences can help researchers, practitioners and educators better understand observed differences between AISs and domestic students and, thus, provide a means of comprehending and reducing confusions and uncertainties surrounding the taboo of mental health among diverse student populations. As well as education as a means of challenging mental health stigma, research suggests that purposeful, contact based anti-stigma programmes are effective (Corrigan, Citation2005; Corrigan et al., Citation2003, Citation2010; Sharpe et al., Citation2022).

The negative impact of adaptation and acculturation difficulties on mental health, with participants emphasising the lack of sense of belonging within the Scottish context, was an important finding. Participants described their experiences with stressors including cultural clashes, communication and language barriers, alienation, loneliness and difficulties forming strong, interpersonal networks. This is consistent with existing research, involving AISs studying in other Western countries (e.g. US, Canada, Australia) reporting feeling of distress and alienation due to the unfamiliarity of their new environment (Rao et al., Citation2010; Yeh & Inose, Citation2003). The importance of social connection and overcoming acculturative stress has been found to be important in facilitating AISs’ sense of belongingness (Glass & Westmont, Citation2014; Ma et al., Citation2020; Razgulin et al., Citation2023; Slaten et al., Citation2016).

A further distinctive difference noted by participants was the perceived positive reception towards mental health held by their host universities in Scotland, which contrasted with the comparatively unfavourable perceptions observed back in their home country. Similar to previous work, one of the challenges in disclosing and seeking help for mental health difficulties experienced by AISs concerned “loss-of-face” (Carr et al., Citation2003; Russell et al., Citation2008; Zhang & Dixon, Citation2003). Loss-of-face is a cultural concept related to shame and embarrassment, which can be defined as “the deterioration in one's social image” (Kam & Bond, Citation2008, p. 175). A range of empirical studies carried out in Asian or Asian American populations support that loss-of-face may be a barrier to help-seeking (Bathje et al., Citation2014; Kim & Yon, Citation2019). However, in a study conducted with AISs in the US, loss-of-face was positively associated with intentions to seek counselling (Yakunina & Weigold, Citation2011). The researchers interpreted this finding as showing that AISs might be reluctant to share psychological problems with significant others or someone from their community and prefer counselling as an option for “saving face” to deal with mental health problems, due to the confidential nature between counsellor and client. It can be observed that problems associated with the effect of “saving face” on AISs’ disclosure and help-seeking decisions is complex and factors such as perceived confidentiality need to be explored in further research. Indeed, recent work reported that AISs may have unique but unspoken concerns and expectations about student counselling and mental health support services, emphasising the utility in openly encouraging the discussion of such perspectives during intake to mental health supports and services (Liu et al., Citation2020). This could partly explain why studies have found international students to underutilise support services such as counselling, as the perceived negative perception of mental health may impede awareness and confidence in these services (Ang & Liamputtong, Citation2008; Clough et al., Citation2019; Lu et al., Citation2014). The importance of providing culturally congruent explanations of mental distress has been found to increase therapeutic working alliances, decrease drop out, increase psychological safety and improve mental health outcomes (Benish et al., Citation2011; Lambert, Citation2013; Morton et al., Citation2022).

The impact of communication barriers (both verbal and non-verbal) on inhibiting disclosure and help-seeking behaviour and the consequential social disconnection and loneliness that AISs’ experienced among their domestic peers was a further important finding to emerge from this study. Similar to a growing body of research, participants discussed how language barriers not only made it difficult for them to effectively engage within the new culture and with local people, but it also negatively impacted on their ability to express their mental health concerns (Newsome & Cooper, Citation2016; Zhang & Brunton, Citation2007). The practical and emotional challenges experienced by the lack of confidence in English proficiency has been widely explored within acculturation research (Wang et al., Citation2010; Xing, Citation2017). Experiencing difficulties with the host language and culture has been found to lead to decreased levels of self-esteem, self-identity, superficial levels of friendships and lack of knowledge to make sense of social situations (Lu et al., Citation2018; Spencer-Oatey & Xiong, Citation2008; Yeh & Inose, Citation2003). It could be suggested that without the ability to form strong, meaningful relationships with domestic peers, AISs experience the loss of their close-knit relationships from back home. This can be detrimental to the mental health and adaptation of AISs, as social connectedness has been found to buffer the adverse impact of marginalisation and loneliness (Glass & Westmont, Citation2014; Haslam et al., Citation2022; Ng et al., Citation2017) and mediate links between adherence to the host culture and psycho-social adjustment (Yu et al., Citation2020; Zhang & Goodson, Citation2011). This corresponds with previous studies which found that over time, international students reportedly experienced lower levels of stress which could coincide with their integration, acceptance and the development of coping strategies as they adapt to the host country (Tang, Citation2018). This suggests that identification and social connection with the host culture may be a beneficial coping strategy for facilitating the management of acculturative stressors and with improving psychological well-being (Zhang & Goodson, Citation2011). Therefore, it could be suggested that to enable effective socio-cultural adaptation, institutional acceptance and cultural sensitivity is required to enable AISs to successfully confront the changing values, beliefs and behaviours which differentiate from their cultural norms in order to minimise the negative impact of acculturative stressors (Demes et al., Citation2015). AISs’ countries of origin are considered culturally distant from their Western host countries, which means they are likely to face greater challenges when adapting to this cultural context (Lee & Ciftci, Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2018). Larger differences in values, attitudes and beliefs place higher demands on adjustment and coping, and thus may result in lower levels of psychological adaptation among AISs (Bethel et al., Citation2020; Razgulin et al, Citation2023; Slaten et al., Citation2016). Previous studies in the US and Australia have found that compared to AISs, other international student groups (e.g. European and South American students) reported better socio-cultural adjustment and fewer psychological symptoms such as depression (Zhang & Goodson, Citation2011). Further, AISs are less inclined to utilise mental health services when they need them, and poor mental health literacy is one of the most significant barriers (Cheng et al., Citation2018; Soorkia et al., Citation2011; Tang et al., Citation2012). Better knowledge of mental health and support services could improve AISs’ ability to cope with the challenges they face and promote their help-seeking behaviour. However, to date there is no published study focused on culturally sensitive mental health literacy interventions for AISs. In addition, more research is needed on how to measure AISs’ mental health literacy given that current available mental health literacy measures have been developed based on Westernised notions of mental health which may not capture AISs’ understandings and perspectives on mental health (Cogan et al., Citation2022; Clough et al., Citation2020; Reis et al., Citation2021).

While it is not possible to make causal assumptions based on the current study’s findings, the rich and in-depth insights to have emerged from AISs’ perspectives and experiences provide a unique contribution to the existing evidence base, through considering the wider Scottish context, and will inform the development of future longitudinal work. Further research would benefit from a sub-group analysis of the socio-cultural experiences of AISs from diverse ethnic origin identities as it is recognised that there is significant heterogeneity within the Asian student population. The majority of Asian countries are home to a diversity of different ethnic groups, often with their own distinct languages, cultures and styles of dress (Kim, Citation2007). Many of these groups have their own systems of religious belief and practice as well. Further work adopting a larger scale, mixed method, community participatory approach (MacIntyre et al., Citation2019b, Citation2022) exploring differences as well as commonalities among AISs would provide an even deeper understanding of the mental health issues, challenges and opportunities for learning how best to inform mental health policy and support services in HE institutions moving forward and to enhance inter-cultural relations among diverse student populations (Cogan et al., Citation2023). Giving voice to AISs and recognising their need for support in navigating uncertainty and acculturational challenges as well as complex education and healthcare systems is essential in facilitating a sense of belonging and inclusion within their host HE institutions (Cogan et al., Citation2021).

Implications

This study has implications for mental health support workers, educators, practitioner and policy makers in HE institutions. Arguably, HE institutions could be more proactive in supporting the adaptation of AISs and mitigating acculturative stressors. For example, universities could aim to develop peer support/buddy programmes between home and international students using social media platforms that are more familiar to AISs (e.g. WeChat for Chinese students). To reduce the language and communication barriers faced by AISs, HE institutions could provide more support for English learning and aim to build more diverse student wellbeing teams. Culturally sensitive training workshops on relevant topics (e.g. introducing university wellbeing service, improving mental health literacy, reducing stigma, coping skills trainings, seeking help for mental health) could be offered to AISs to support their wellbeing and facilitate their disclosure and help-seeking when needed. This is particularly pertinent given the context of stressors associated with the COVID-19 outbreak and its consequent impact on student mental health and wellbeing (Dong et al., Citation2022; Van de Velde et al., Citation2021). This may be particularly challenging for AISs given that this pandemic has been found to have triggered xenophobic reactions towards students of Asian-origin, including prejudice, violence and discrimination related to COVID-19 leading to feelings of isolation (Dong et al., Citation2023; Litam, Citation2020; Maleku et al., Citation2021; Rzymski & Nowicki, Citation2020; Zhou et al., Citation2023). These findings underscore the importance of HE institutions being aware of these challenges and taking responsibility in overcoming and preventing discriminatory attitudes and behaviours which may adversely impact on student mental health. Understanding and measuring the systemic and structural barriers that are often faced by AISs in accessing mental health supports is essential (Cogan et al, Citation2022); this may help raise awareness of students’ rights. In addition, it is important to make sure that counsellors, psychological support staff, teaching staff, researchers and other staff members supporting student mental health have appropriate awareness, knowledge and skills to work effectively with AISs. Mental health policy makers are encouraged to address the need for supporting AISs and enhancing mental health support workers’ cultural competences in order to create a more inclusive, diverse and socially connected HE environment.

Conclusion

This study reported on AISs’ understandings of mental health, disclosure and help-seeking within HE institutions in Scotland. The importance of understanding the negative beliefs, stigma and fear surrounding mental health and how this can lead to unhelpful ways of coping with the stressors associated with adaptation and acculturation challenges are emphasised. Recognising how the barriers in communication (both verbal and non-verbal) may lead to AISs feeling socially disconnected from HE institutions is essential, particularly for mental health supports and services which seek to help students gain a sense of integration and acceptance within the host institution in which they are students. Addressing the barriers that may inhibit disclosure and help-seeking for mental health issues, including increasing mental health literacy, providing coping skills training and improving inter-cultural relations among diverse student populations, is paramount. Adopting a “whole” systems approach (Dooris et al., Citation2020) to supporting student mental health within and across HEIs is advocated in order to embrace the challenges and opportunities presented within a complex multi-cultural environment.

Authors’ contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception, design and analysis. Material preparation and data collection were performed by all authors. Data analysis and write up were performed by Nicola Cogan, Xi Liu and Yvonne Chau. All authors contributed to the final manuscript, which all authors read and approved.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the University Ethics Committee, University of Strathclyde. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and BPS ethical code of conduct.

Consent

All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the qualitative and potentially identifiable information obtained in the interviews but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicola A. Cogan

Dr Nicola Cogan (PhD, D.Clin.Psy): Senior lecturer at the University of Strathclyde. She joined Strathclyde in October 2017 having previously worked as a consultant clinical psychologist and clinical lead in mental health services in the NHS. She has over 15 years NHS experience working as a practitioner clinical psychologist in mental health services. She retains an honorary consultant clinical psychologist post in NHS Lanarkshire. Her consultancy work has largely concerned trauma informed practice with first responder and frontline workers. She completed a Professional Doctorate in Clinical Psychology (D.Clin.Psy) at the University of Edinburgh. Prior to this she completed a PhD in Psychology and Social Policy and Social Work and MA (Hons) Psychology at the University of Glasgow. Her research interests are in the areas of mental health, wellbeing, recovery and citizenship in applied health and social contexts. She is involved with research adopting community participatory research methods. She is a member of the International Recovery and Citizenship Collective led by Yale Medical School, where she has a strong working collaborative.

X. Liu

Dr Xi Liu (PhD): Senior teaching fellow at the University of Strathclyde with expertise in child and adolescent mental health. Dr Liu is also a qualified therapeutic counsellor.

Y. Chin-Van Chau

Chin-Van Chau (MSc): Research Assistant at the University of Strathclyde with expertise in qualitative research methods and research on student mental health.

S.W. Kelly

Dr Steve Kelly (PhD): Senior teaching fellow at the University of Strathclyde and a qualitied person- centred counsellor with research expertise in mixed methods.

T. Anderson

Dr Tony Anderson (PhD): Senior teaching fellow at the University of Strathclyde with expertise in student mental health and critical thinking skills.

C. Flynn

Colin Flynn (MSc): Lead for the Student Mental Wellbeing Service at the University of Strathclyde and a qualified therapeutic counsellor.

L. Scott

Laura Scott (MSc): Research assistant at University of Strathclyde with specialist interest in student mental health and qualitative research.

A. Zaglis

Antonia Zaglis (MSc): Research assistant at the University of Strathclyde with specialist interest in student mental health and qualitative research.

P. Corrigan

Professor Patrick Corrigan (PhD): Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the Illinois Institute of Technology and a core faculty member in the Division of Counseling and Rehabilitation Science.

References

- Altweck, L., Marshall, T. C., Ferenczi, N., & Lefringhausen, K. (2015). Mental health literacy: A cross-cultural approach to knowledge and beliefs about depression, schizophrenia and generalized anxiety disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1272. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01272

- Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16(10), 1472–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.005

- Ando, H., Cousins, R., & Young, C. (2014). Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: Development and refinement of a codebook. Comprehensive Psychology, 3. https://doi.org/10.2466/03.CP.3.4

- Ang, P. L., & Liamputtong, P. (2008). ‘Out of the Circle': International students and the use of university counselling services. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 48(1), 108–130.

- Barkham, M., Bewick, B., Mullin, T., Gilbody, S., Connell, J., Cahill, J., Mellor-Clark, J., Richards, D., Unsworth, G., & Evans, C. (2013). The CORE-10: A short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 13(1), 3–13.

- Barletta, J., & Kobayashi, Y. (2007). Cross-cultural counselling with international students. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 17(2), 182–194.

- Bathje, G. J., Kim, E., Rau, E., Bassiouny, M., & Kim, T. (2014). Attitudes toward face-to-face and online counseling: Roles of self-concealment: Openness to experience, loss of face, stigma, and disclosure expectations among Korean college students. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 36(4), 408–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-014-9215-2

- Benish, S. G., Quintana, S., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(3), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023626

- Bethel, A., Ward, C., & Fetvadjiev, V. H. (2020). Cross-cultural transition and psychological adaptation of international students: The mediating role of host national connectedness. Frontiers in Education, 5, 539950. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.539950

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 57–71). APA books.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2018). Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: A critical reflection. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research Journal, 18(2), 107–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12165

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2023). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be (com)ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Rance, N. (2014). How to use thematic analysis with interview data. In A. Vossler, & N. Moller (Eds.), The counselling & psychotherapy research handbook (pp. 183–197). Sage Publications.

- British Psychological Society. (2021). Code of human research ethics. ISBN: 978-1-85433-762-7.

- Cao, C., Zhu, C., & Meng, Q. (2021). Chinese international students’ coping strategies, social support resources in response to academic stressors: Does heritage culture or host context matter? Current Psychology, 40(1), 242–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9929-0

- Carr, J. L., Miki Koyama, M., & Thiagarajan, M. (2003). A women's support group for Asian international students. Journal of American College Health, 52(3), 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480309595735

- Chen, J. A., Stevens, C., Wong, S. H., & Liu, C. H. (2019). Psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses among US college students: A comparison by race and ethnicity. Psychiatric Services, 70(6), 442–449. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800388

- Chen, J. H., Li, Y., Wu, A. M., & Tong, K. K. (2020). The overlooked minority: Mental health of international students worldwide under the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 102333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102333

- Cheng, H., Wang, C., McDermott, R. C., Kridel, M., & Rislin, J. (2018). Self-stigma, Mental health literacy, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling and Development, 96(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12178

- Clarke, E., & Visser, J. (2019). Pragmatic research methodology in education: Possibilities and pitfalls. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 42(5), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2018.1524866

- Clough, B. A., Nazareth, S. M., & Casey, L. M. (2020). Making the grade: A pilot investigation of an e-intervention to increase mental health literacy and help-seeking intentions among international university students. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 48(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2019.1673312

- Clough, B. A., Nazareth, S. M., Day, J. J., & Casey, L. M. (2019). A comparison of mental health literacy, attitudes, and help-seeking intentions among domestic and international tertiary students. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 47(1), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2018.1459473

- Cogan, N., Macintyre, G., Stewart, A., Harrison-Millan, H., Black, K., Quinn, N., Rowe, M., & Connell, M. (2022). Developing and establishing the psychometric properties of the Strathclyde Citizenship Measure: A new measure for health and social care practice and research. Health Soc Care Community, 30(6), e3949–e3965. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13789

- Cogan, N., Murray, A. L., Gardani, M., O'toole, M., Long, E., Milicev, J., & Leung, M. (2023, March 24). Priorities and directions for future research on student mental health within Scottish Higher Education Institutions: A scoping review protocol. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/69yjv

- Cogan, N. A., Macintyre, G., Stewart, A., Tofts, A., Quinn, N., Johnston, G., Johnston, G., Hamill, L., Robinson, J., Igoe, M., Easton, D., Mcfadden, A. M., & Rowe, M. (2021). The biggest barrier is to inclusion itself”: The experience of citizenship for adults with mental health problems. Journal of Mental Health, 30(3), 358–365.

- Constantine, M. G., Kindaichi, M., Okazaki, S., Gainor, K. A., & Baden, A. L. (2005). A qualitative investigation of the cultural adjustment experiences of Asian international college women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 11(2), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.11.2.162

- Cooke, R., Bewick, B. M., Barkham, M., Bradley, M., & Audin, K. (2006). Measuring, monitoring and managing the psychological well-being of first year university students. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 34(4), 505–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880600942624

- Corrigan, P., Thompson, V., Lambert, D., Sangster, Y., Noel, J. G., & Campbell, J. (2003). Perceptions of discrimination among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 54(8), 1105–1110. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1105

- Corrigan, P. W. (2005). Changing stigma through contact. Advances in Schizophrenia and Clinical Psychiatry, 1, 614–625.

- Corrigan, P. W., Tsang, H. W. H., Shi, K., Lam, C., & Larson, J. (2010). Chinese and American employer’s perspectives regarding hiring people with behaviorally-driven health conditions: The role of stigma. Social Science and Medicine, 71(12), 2162–2169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.025

- Demes, K. A., Geeraert, N., & King, L. A. (2015). The highs and lows of a cultural transition: A longitudinal analysis of sojourner stress and adaptation across 50 countries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(2), 316–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000046

- Dodd, R. H., Dadaczynski, K., Okan, O., McCaffery, K. J., & Pickles, K. (2021). Psychological wellbeing and academic experience of university students in Australia during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030866

- Dong, F., Hwang, Y., & Hodgson, N. A. (2022). Relationships between racial discrimination, social isolation, and mental health among international Asian graduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2052076

- Dong, F., Hwang, Y., & Hodgson, N. A. (2023). “I have a wish”: Anti-Asian racism and facing challenges amid the COVID-19 pandemic among Asian international graduate students. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 34(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/10436596221143331

- Dooris, M., Powell, S., & Farrier, A. (2020). Conceptualizing the ‘whole university’ approach: An international qualitative study. Health Promotion International, 35(4), 730–740. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daz072

- Furnham, A., Cook, R., Martin, N., & Batey, M. (2011). Mental health literacy among university students. Journal of Public Mental Health, 10(4), 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465721111188223

- Glass, C. R., & Westmont, C. M. (2014). Comparative effects of belongingness on the academic success and cross-cultural interactions of domestic and international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38,106–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.04.004

- Gorczynski, P., Sims-schouten, W., Hill, D., & Wilson, J. C. (2017). Examining mental health literacy, help seeking behaviours, and mental health outcomes in UK university students. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 12(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-05-2016-0027

- Gui, J., Kono, S., He, Y., & Noels, K. A. (2023). Basic psychological need satisfaction in leisure and academics of Chinese international students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Leisure Sciences, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2023.2167027

- Han, X., Han, X., Luo, Q., & Jacobs, S. (2013). Report of a Mental Health Survey among Chinese international students at Yale University. Journal of American College Health, 61(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2012.738267

- Haslam, S. A., Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Jetten, J., Bentley, S. V., Fong, P., & Steffens, N. K. (2022). Social identity makes group-based social connection possible: Implications for loneliness and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.013

- Heath, P. J., Vogel, D. L., & Al-Darmaki, F. R. (2016). Help-seeking attitudes of United Arab Emirates students: Examining loss of face, stigma, and self-disclosure. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(3), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000015621149

- HESA. (2023). https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/19-01-2023/sb265-higher-education-student-statistics

- Holliman, A. J., Bastaman, A. S., Wu, H. S., Xu, S., & Waldeck, D. (2023). Exploring the experiences of international Chinese students at a UK university: A qualitative inquiry. Multicultural Learning and Teaching.

- Huang, L., Kern, M. L., & Oades, L. G. (2020). Strengthening university student wellbeing: Language and perceptions of Chinese international students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155538

- Johnson, R. B., Waal, C., Stefurak, T., & Hildebrand, D. L. (2017). Understanding the philosophical positions of classical and neopragmatists for mixed methods research. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 69(2), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-017-0452-3

- Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166(4), 182–186. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x

- Kam, C. C. S., & Bond, M. H. (2008). Role of emotions and behavioural responses in mediating the impact of face loss on relationship deterioration: Are Chinese more face-sensitive than Americans? Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2008.00254.x

- Kim, B. S., & Omizo, M. M. (2003). Asian cultural values, attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, and willingness to See a counselor. The Counseling Psychologist, 31(3), 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000003031003008

- Kim, P. Y., & Yon, K. (2019). Stigma, loss of face, and help-seeking attitudes among South Korean college students. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(3), 331–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019872790

- Kim, W. (2007). Diversity among Southeast Asian ethnic groups: A study of mental health disorders among Cambodians, Laotians, Miens, and Vietnamese. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 15(3-4), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1300/J051v15n03_04

- Koo, K., & Nyunt, G. (2023). Pandemic in a foreign country: Barriers to international students’ well-being during COVID-19. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 60(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2022.2056476

- Kristiana, I. F., Karyanta, N. A., Simanjuntak, E., Prihatsanti, U., Ingarianti, T. M., & Shohib, M. (2022). Social support and acculturative stress of international students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116568

- Kuo, B. C., & Roysircar, G. (2006). An exploratory study of cross-cultural adaptation of adolescent Taiwanese unaccompanied sojourners in Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(2), 159–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.007

- Lam, C. S., Tsang, H., Chan, F., & Corrigan, P. W. (2006). Chinese and American perspectives on stigma. Rehabilitation Education, 20(4), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1891/088970106805065368

- Lambert, M. J. (2013). Outcome in psychotherapy: The past and important advances. Psychotherapy, 50(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030682

- Lee, E., Ditchman, N., Fong, M. W., Piper, L., & Feigon, M. (2014). Mental health service seeking among Korean International Students in the United States: A path analysis: Mental health service-seeking behavior. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(6), 639–655. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21643

- Lee, J. Y., & Ciftci, A. (2014). Asian international students’ socio-cultural adaptation: Influence of multicultural personality, assertiveness, academic self-efficacy, and social support. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.009

- Li, J., Wang, Y., & Xiao, F. (2014). East Asian international students and psychological well-being: A systematic review. Journal of International Students, 4(4), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v4i4.450

- Li, P., Wong, Y. J., & Toth, P. (2013). Asian International Students’ willingness to seek counseling: A mixed-methods study. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 35(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-012-9163-7

- Liao, K. Y. H., Wei, M., Tsai, P. C., Kim, J., & Cheng, H. L. (2023). Language discrimination, Interpersonal shame, and depressive symptoms among international students with Chinese heritage: Collective self-esteem as a buffer. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2023.2164845

- Litam, S. D. (2020). ‘Take your kung-flu back to Wuhan': Counselling Asians, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders with race-based trauma related to COVID-19. Professional Counselor, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.15241/sdal.10.2.144

- Liu, H., Wong, Y. J., Mitts, N. G., Li, P. J., & Cheng, J. (2020). A phenomenological study of East Asian international students’ experience of counselling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 42(3), 269–291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.738474

- Lobe, B., Morgan, D., & Hoffman, K. A. (2020). Qualitative data collection in an era of social distancing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406920937875. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940692093787

- Lomer, S. (2023). International student recruitment: Policy, paradox and practice. Universities in Crisis: Academic Professionalism in Uncertain Times, 117.

- Lu, S. H., Dear, B. F., Johnston, L., Wootton, B. M., & Titov, N. (2014). An internet survey of emotional health, treatment seeking and barriers to accessing mental health treatment among Chinese-speaking international students in Australia. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 27(1), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2013.824408

- Lu, Y., Chui, H., Zhu, R., Zhao, H., Zhang, Y., Liao, J., & Miller, M. J. (2018). What does “good adjustment” mean for Chinese international students? A qualitative investigation. The Counselling Psychologist, 46(8), 979–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000018824283

- Ma, K., Pitner, R., Sakamoto, I., & Park, H. Y. (2020). Challenges in acculturation among international students from Asian collectivist cultures. Higher Education Studies, 10(3), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n3p34

- Macintyre, G., Cogan, N., Stewart, A., Quinn, N., O'connell, M., & Rowe, M. (2022). Citizens defining citizenship: A model grounded in lived experience and its implications for research, policy and practice. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(3), e695–e705.

- Macintyre, G., Cogan, N., Stewart, A., Quinn, N., Rowe, M., O’connell, M., Easton, D., Hamill, L., Igoe, M., Johnston, G., Mcfadden, A., & Robinson, J. (2019a). Understanding citizenship within a health and social care context in Scotland using community-based participatory research methods. In Sage research methods cases Part 1. SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526484918

- Macintyre, G., Cogan, N. A., Stewart, A. E., Quinn, N., Rowe, M., & Connell, M. (2019b). What’s citizenship got to do with mental health? Rationale for inclusion of citizenship as part of a mental health strategy. Journal of Public Mental Health, 18(3), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-04-2019-0040

- Maeshima, L. S., & Parent, M. C. (2022). Mental health stigma and professional help-seeking behaviors among Asian American and Asian international students. Journal of American College Health, 70(6), 1761–1767. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1819820

- Maguire, C., & Cameron, J. (2021). Thriving learners. The Mental Health Foundation.

- Maleku, A., Kim, Y. K., Kirsch, J., Um, M. Y., Haran, H., Yu, M., & Moon, S. S. (2021). The hidden minority: Discrimination and mental health among international students in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(5), e2419–e2432.

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Masuda, A., & Boone, M. S. (2011). Mental health stigma, self-concealment, and help-seeking attitudes among Asian American and European American college students with no help-seeking experience. International Journal For the Advancement of Counselling, 33(4), 266–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-011-9129-1

- McKay, S., Veresova, M., Bailey, E., Lamblin, M., & Robinson, J. (2023). Suicide prevention for international students: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021500

- Miller, M. J., Minji, Y., Kayi, H., Choi, N., & Lim, R. H. (2011). Acculturation, enculturation, and Asian American college students’ mental health and attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 58(3), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023636

- Mok, K., Xiong, W., Ke, G., & Cheung, J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on international higher education and student mobility: Student perspectives from mainland China and Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101718

- Moravcsik, A. (2014). Transparency: The revolution in qualitative research. PS: Political Science & Politics, 47(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096513001789

- Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48–76.

- Morton, L., Cogan, N., Kolacz, J., Calderwood, C., Nikolic, M., Bacon, T., Pathe, E., Williams, D., & Porges, S. W. (2022). A new measure of feeling safe: Developing psychometric properties of the Neuroception of Psychological Safety Scale (NPSS). Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001313

- Nabi, N., Tweats, K., Logan, K., Moore, S., McMurdo, A., Vani, S., Cogen, N., & Fleming, L. (2019). Overcoming the challenges and complexities of researching a vulnerable population within a palliative care context. SAGE research methods Cases, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529709568

- Narey, D. C. (2017). Philosophical critiques of qualitative research methodology in education: A synthesis of analytic-pragmatist and feminist-poststructuralist perspectives. Philosophy of Education Archive, 70, 335–343. https://doi.org/10.47925/2014.335

- Naylor, R. (2022). Key factors influencing psychological distress in university students: The effects of tertiary entrance scores. Studies in Higher Education, 47(3), 630–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1776245

- Newsome, L., & Cooper, P. (2016). International students’ cultural and social experiences in a British university: “Such a hard life [it] is here”. Journal of International Students, 6(1), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v6i1.488

- Ng, T., Wang, K., & Chan, W. (2017). Acculturation and cross-cultural adaptation: The moderating role of social support. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 59, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.04.012

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Pan, J., Fu, D., Joubert, L., & Chan, C. (2007). Acculturative stressor and meaning of life as predictors of negative affect in acculturation: A cross-cultural comparative study between Chinese international students in Australia and Hong Kong. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41(9), 740–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670701517942

- Pimenta, S. M., Hunter, S. C., Rasmussen, S., Cogan, N., & Martin, B. (2021). Young people’s coping strategies when dealing with their own and a friend’s symptoms of poor mental health: A qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/07435584211062115

- Ra, Y., & Trusty, J. (2015). Coping strategies for managing acculturative stress among Asian international students. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 37(4), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-015-9246-3

- Rao, D., Horton, R., Tsang, H., Shi, K., & Corrigan, P. (2010). Does individualism help explain differences in employers’ stigmatizing attitudes toward disability across Chinese and American cultures? Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(4), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021841

- Razgulin, J., Argustaitė-Zailskienė, G., & Šmigelskas, K. (2023). The role of social support and sociocultural adjustment for international students’ mental health. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 893. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27123-9

- Reis, A. C., Saheb, R., Moyo, T., Smith, C., & Sperandei, S. (2021). The impact of mental health literacy training programs on the mental health literacy of university students: A systematic review. Prevention Science, 23(4),1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01283-y

- Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

- Russell, J., Thomson, G., & Rosenthal, D. (2008). International student use of university health and counselling services. Higher Education, 56(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9089-x

- Ryan, M. L., Shocket, I. M., & Stallman, H. M. (2010). Universal online interventions might engage psychologically distressed university students who are unlikely to seek formal help. Advances in Mental Health, 9(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.9.1.73

- Rzymski, P., & Nowicki, M. (2020). COVID-19-related prejudice toward Asian medical students: A consequence of SARS-CoV-2 fears in Poland. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 13(6), 873–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.04.013

- Scottish Government. (2018, March). The impact of international students in Scotland: Scottish Government response to the Migration Advisory Committee’s consultation on the impact of international students in the UK. https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/corporate-report/2018/03/impact-international-students-scotland-scottish-government-response-migration-advisory-committees/documents/00532586-pdf/00532586-pdf/govscot&per;3Adocument/00532586.pdf

- Sharpe, T., Murray, M., Taylor, R., Corrigan, P., & Cogan, N. (2022). Engaging young people in mental health research addressing stigma. Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/Engaging-Young-People-in-Mental-Health-Research–5757.

- Shaw, R. L., Bishop, F. L., Horwood, J., Chilcot, J., & Arden, M. (2019). Enhancing the quality and transparency of qualitative research methods in health psychology. British Journal of Health Psychology, 24(4), 739–745. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12393

- Slaten, C. D., Elison, Z. M., Lee, J. Y., Yough, M., & Scalise, D. (2016). Belonging on campus: A qualitative inquiry of Asian international students. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(3), 383–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016633506

- Smith, R. A., & Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 699–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004

- Soorkia, R., Snelgar, R., & Swami, V. (2011). Factors influencing attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help among south Asian students in Britain. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 14(6), 613–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.494176

- Spencer-Oatey, H., & Xiong, Z. (2008). Chinese students’ psychological and sociocultural adjustments to Britain: An empirical study. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 19(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310608668753. ISSN 0790-8318.

- Sun, S., Hoyt, W. T., Brockberg, D., Lam, J., Tiwari, D., & Tracey, T. J. (2016). Acculturation and enculturation as predictors of psychological help-seeking attitudes (HSAs) among racial and ethnic minorities: A meta-analytic investigation. United States: American Psychological Association, 63(6), 617–632. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000172

- Tang, H. (2018). Coping strategies of international Chinese undergraduates in response to academic challenges in U.S. Colleges. Teachers College Record, 120(2), 1–42.

- Tang, T. T., Reilly, J., & Dickson, J. M. (2012). Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help among Chinese students at a UK university. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 12(4), 287–293. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00417

- Universities UK. (2022). https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/universities-uk-international/explore-uuki/international-student-recruitment/international-student-recruitment data&hash;:∼:text=In&per;202020&per;2D21&per;2C&per;20there&per;20were,the&per;20UK&per;20in&per;202020&per;2D21.

- Van de Velde, S., Buffel, V., Bracke, P., Van Hal, G., Somogyi, N. M., & Willems, B. (2021). The COVID-19 international student well-being study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 49(1), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820981186

- Vogel, D. L., Strass, H. A., Heath, P. J., Al-Darmaki, F. R., Armstrong, P. I., Baptista, M. N., Brenner, R. E., Gonçalves, M., Lannin, D. G., Liao, H.-Y., Mackenzie, C. S., Mak, W. W. S., Rubin, M., Topkaya, N., Wade, N. G., Wang, Y.-F., & Zlati, A. (2017). Stigma of seeking psychological services: Examining college students across ten countries/regions. The Counselling Psychologist, 45(2), 170–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016671411

- Wang, S. C., Schwartz, S. J., & Zamboanga, B. L. (2010). Acculturative stress among Cuban American college students: Exploring the mediating pathways between acculturation and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(11), 2862–2887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00684.x

- Wang, Y., Li, T., Noltemeyer, A., Wang, A., Zhang, J., & Shaw, K. (2018). Cross-cultural adaptation of international college students in the United States. Journal of International Students, 8(2), 821–842. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v8i2.116

- Winter, P., Rix, A., & Grant, A. (2017). Medical student beliefs about disclosure of mental health issues: A qualitative study. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 44(1), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0615-097R

- Wong, Y., Wang, K., & Maffini, C. (2014). Asian international students’ mental health-related outcomes: A person × context cultural framework. The Counselling Psychologist, 42(2), 278–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000013482592

- Xing, D. (2017). Exploring academic acculturation experiences of Chinese international students with low oral English proficiency: A musically enhanced narrative inquiry [Doctoral dissertation]. Queen's University (Canada).

- Yakunina, E., & Weigold, I. (2011). Asian international students’ intentions to seek counseling: Integrating cognitive and cultural predictors. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 2(3), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024821

- Yeh, C. J., & Inose, M. (2003). International students’ reported English fluency, social support satisfaction, and social connectedness as predictors of acculturative stress. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 16(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951507031000114058

- Yu, B., Vyas, L., & Wright, E. (2020). Crosscultural transitions in a bilingual context: The interplays between bilingual, individual and interpersonal factors and adaptation. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 41(7), 600–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1623224

- Zhai, Y., & Du, X. (2020). Mental health care for international Chinese students affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30089-4

- Zhang, J., & Goodson, P. (2011). Predictors of international students’ psychosocial adjustment to life in the United States: A systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(2), 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.011

- Zhang, N., & Dixon, D. N. (2003). Acculturation and attitudes of Asian international students toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 31(3), 205–222.

- Zhang, Y., & Jung, E. (2017). Multi-dimensionality of acculturative stress among Chinese international students: What lies behind their struggles?. International Research and Review, 7(1), 23–43.

- Zhang, Z., & Brunton, M. (2007). Differences in living and learning: Chinese international students in New Zealand. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(2), 124–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306289834

- Zhou, S., Banawa, R., & Oh, H. (2023). Stop Asian hate: The mental health impact of racial discrimination among Asian Pacific Islander young and emerging adults during COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.132