ABSTRACT

Migrants, along with youth, stand at the forefront of gig economy in many countries. Gig work intersects with other domains of migrants’ post-migration life, including career development. To substantiate “plural systems of knowledges” [Sultana, R. G. (2021). For a postcolonial turn in career guidance: The dialectic between universalisms and localisms. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, p. 5] required for understanding such intersecting boundaries, qualitative research that prioritises migrants’ local knowledges is essential. This research systemically explores the career development of New Zealand immigrants working as rideshare drivers in Australia and considers the impact of gig work on their career development through the lens of the Systems Theory Framework (STF) of career development. Using a qualitative exploratory multiple case study design, interviews were conducted with four rideshare drivers. Findings highlight the role of systemic influences in the intersections of migration with gig work and career development. The role of the STF of career development in facilitating a systemic exploration through both stages of data collection and data analysis is highlighted.

The nature of work is changing rapidly and with the introduction of digital platforms, gig work is an increasingly growing sector of the global economy. Gig work is the term used to apply to “contingent labour that uses electronically mediated employment arrangements in which individuals find short-term tasks or projects via websites or mobile apps that connect them to clients and process payment” (Kuhn & Galloway, Citation2019, p. 186). A variety of labour platforms now provide individuals with the ability to choose when and whether to work, either remotely or in person.

Gig work is not self-employment, contract work, part-time or seasonal work. It is performed via a labour-based digital platform where an electronic intermediary (like Uber) matches private workers with consumers in real-time and on-demand (Fleming et al., Citation2019). Therefore, gig work differs from traditional work where agreements between employers and employees may contain clearly defined employment contracts that outline expectations and include standardised wage amounts and/or specific time arrangements. In most countries of the world including Australia, which is the focus of this article, these arrangements are missing for gig workers (Malos et al., Citation2018). Therefore, gig work remains precarious (Kost et al., Citation2020) because it is generally temporary, atypical, contingent, or non-standard work, lacks job security, worker rights, and often has inadequate salary without much of a prospect for career advancement (Ornek et al., Citation2020). Broader underlying factors are known to play a role in the precarisation of gig work, including globalisation, neoliberal politics, and regression of social policies to facilitate open markets, among others (Helbling & Kanji, Citation2018; Koranyi et al., Citation2018). Unpacking such underlying factors remains beyond the scope of this paper.

Although traditional jobs still dominate the global economy, the share of the gig economy from the labour markets is constantly increasing in many economically developed countries, such as the United States, Canada and Australia. For example, between 2005 and 2020, alternative work arrangements (which include gig work) accounted for nearly 80% of employment growth in the United States (Mas & Pallais, Citation2020). Given the focus of this article is the Australian gig economy and its employment arrangements, it is important to consider that the size of the Australian gig economy has increased over nine times between 2015 and 2019 (Australian Parliament, Citation2021). In 2021, more than 100,000 people worked as rideshare drivers in Australia (Rideshare Drivers Association of Australia, Citation2021). Immigrants and young people are at the frontline of gig work (Altenried, Citation2021; Van Doorn et al., Citation2020; van Doorn & Vijay, Citation2021). However, these same groups are more vulnerable to some of the negative effects of participating in gig work (Victorian Government, Citation2020). Given the major contribution of globalisation and the rapidly changing nature of work (Graham et al., Citation2017), it is important to explore the career development of immigrants after immigration, how or why they engage with gig work and what are the implications of such engagements for their career development.

Career development, immigration and vulnerable groups

Historically, the fields of vocational psychology (and consequently career development) emerged in the early 1900s with a social justice focus on the vocational needs of vulnerable groups, such as those with immigration and refugee backgrounds (Parsons, Citation1909). With new waves of migration in the twenty-first century, the career development of some groups of immigrants has recently received increased and deserving emphasis (e.g. Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022; Blustein & Duffy, Citation2020; Fejes et al., Citation2022; Magnano et al., Citation2022; Zacher, Citation2019). For example, a special issue of the Journal of Vocational Behavior focused specifically on the career development of refugees (Newman et al., Citation2018), and included an article on the career development of migrants with refugee backgrounds in the Australian context (Abkhezr et al., Citation2018).

While trying to develop their careers, immigrants (including refugees, asylum seekers and even some voluntary migrants) must adapt to life in a new context after migration. This poses many challenges for them and as such they could be disadvantaged and might need further support. However, immigrants are a highly diverse and heterogenous group. The nature of and the complexities surrounding their migration intersect with other various contextual factors that they face in each host country, including its specific migration policies. Various terms distinguish between different groups of immigrants. For example, a refugee is a person:

who owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his [sic] nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country. (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], Citation2012, p. 2)

a claim that he or she is a refugee and is waiting for that claim to be accepted or rejected. The term contains no presumption either way – it simply describes the fact that someone has lodged the claim. Some asylum-seekers will be judged to be refugees and others not. (UNHCR, Citation2012, p. 8)

Immigrants coming to Australia often seek better employment and increased economic opportunities (Breen, Citation2016). According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Citation2020), 7.3 million immigrants call Australia home, which is approximately 30% of the population. Skilled migrants are the biggest group among voluntary migrants who enter Australia. The Australian government defines skilled migrants as “individuals or families who are skilled and looking to permanently migrate to Australia, make a significant contribution to the Australian economy, and fill positions where no Australian workers are available to fill” (Australian Government, Citation2023a, para. 1). Australia’s Skilled Migration Program is the biggest migration programme in the country and each year attracts a few hundred thousand immigrants to Australia, but little is known about the career development trajectories of people who enter Australia under this scheme or other voluntary immigrants (Ressia et al., Citation2016).

All groups of immigrants could experience downward occupational mobility, particularly those from developing countries or with refugee backgrounds. This means that they are employed in lower-skilled jobs than those they held pre-immigration (Ressia et al., Citation2016). While there is a growing research focus on the career development of those with refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds, little is known about the career development of voluntary immigrants who engage in gig work post-migration. Given the heterogeneity of gig worker immigrants, it is important to extend research that prioritises a focus on subjective experiences and narratives of immigrants from different cultural and contextual backgrounds to facilitate a “disentangling of the intersections of gig work, migration, and career development” (Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022, p. 17). Voluntary immigrants from economically developed countries, such as New Zealand, form a major segment of the Australian immigrant population. Therefore, exploring their career development and how it intersects with their immigration journey and context seems warranted.

New Zealand immigrants in Australia

Immigrants from New Zealand (NZ) are the fourth largest group of overseas-born residents in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2020). By 2023, over 670,000 New Zealanders live and work in Australia on special category visas, including 380,000 who arrived after 2001 eligible for Australian citizenship (Karp, Citation2023). Special category visas (Australian Government, Citation2023b) are temporary visas that allow NZ citizens to live and work in Australia, giving them certain entitlements but posing certain restrictions (e.g., duration of employment with a single employer). In addition to special category visas, many other NZ immigrants live in Australia under other visa streams such as partner visas, and skilled migration visas for NZ citizens.

NZ immigrants were selected for this research because New Zealand is one of Australia’s close neighbours, is an economically developed country with a similar labour market to Australia, has unique immigration arrangements with Australia, and New Zealanders are among the top five largest populations shaping Australia’s immigrant population. Career research that uses an experience-near approach for disentangling the intersections of migration with gig work and career development is recently highlighted (Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022). Advancing a more contextual understanding of the intersecting boundaries between migration and other aspects of post-migration life, such as career development and gig work, aligns with the need for substantiating “plural systems of knowledges” (Sultana, Citation2021, p. 5). This means that a wide range of context-sensitive, anthropological and experience-near research is needed in order to attend to various groups of migrants’ subjective views on migration, and their local and particular knowledges about work and career development. However, given the significant challenges that surround the career development of migrants and refugees from economically developing countries, career literature could lose sight of the intersectional experiences of migrants from developed countries when studying the intersections of migration with career development. Little is known about the career development of NZ immigrants in Australia, particularly since the emergence of gig work. Therefore, this research intended to systemically explore NZ immigrant gig workers’ career development and their personal experiences of working in the Australian gig economy after immigration.

While acknowledging the heterogeneity of immigrants across the globe, they are generally considered a vulnerable group (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2020; Sargeant & Tucker, Citation2009). Different groups of immigrants are significantly affected by precarious work due to limited awareness of work rights, unfamiliarity with the labour market of their host countries, and limited access to occupational health and service policies among other complexities (Moyce & Schenker, Citation2018; Yanar et al., Citation2018). There has been some recent attention to the career development of people with refugee and forced migration backgrounds and the implications of such contextual factors on their career development (Abkhezr et al., Citation2015, Citation2018, Citation2022; Dunwoodie et al., Citation2022; Fedrigo et al., Citation2022; Fejes et al., Citation2022; Magnano et al., Citation2022; McMahon et al., Citation2019; Obschonka et al., Citation2018). However, it must be acknowledged that voluntary, family or economic immigrants from economically developed nations could also face challenges that deserve attention. For example, there might be an assumption that NZ immigrants do not encounter challenges with their career development in Australia. However, research has shown that despite their relatively less challenging process of securing and maintaining employment when compared to people from refugee backgrounds, many skilled migrants (both from economically developing and developed countries) face numerous challenges with their career development (Breen, Citation2016; Faaliyat et al., Citation2021) and some are pushed to engage in precarious gig work (Ornek et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is also important to investigate how gig work affects immigrants from economically developed countries. Such a particular focus on the career development of immigrants from economically developed countries could also help disentangle some of the global and overly generalised assumptions about the intersections of migration and career development (Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022) and contribute to substantiating “plural systems of knowledges” (Sultana, Citation2021, p. 5) about the intersecting boundaries of migration with other aspects of post-migration life such as career development and gig work. This research focused on the career development of middle-aged New Zealand male immigrants working in the Australian gig economy as rideshare drivers and employed the Systems Theory Framework of career development (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021) as a theoretical lens.

Systems Theory Framework of career development

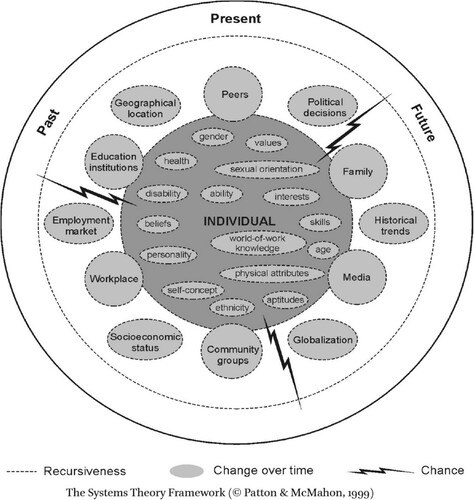

The Systems Theory Framework (STF) of career development provides a comprehensive conceptualisation of the many existing theories and concepts relevant to understanding career development (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021). The fundamental premise to understanding the STF of career development is a dynamic individual in context perspective whereby the individual is at the centre of a range of systems of influence in the context of past, present and future time (see ). The STF illustrates a range of intrapersonal, social, and environmental-societal influences on the individual in three interconnected systems, the individual, social, and environmental-societal systems. The individual system incorporates physical and psychological influences. The social system incorporates influences such as family, peers, and workplace colleagues. The environmental-societal system incorporates influences such as geographic location, political decisions, and globalisation. In the STF, the interaction between the influences is depicted by broken lines which suggest permeability and is referred to as recursiveness (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021). Change over time is inevitable and the lightning bolts represent the role of chance in an individual’s career development. The STF has cross-cultural applications (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021).

The STF of career development provided a framework for the exploration of the career development of New Zealand immigrant gig workers through its systemic and dynamic depiction of career development by considering the influences at play in the career development of the participants. It considers how each of the systems of influence interacts with other systems to enhance or inhibit each individual’s career development. As such, this research aims to explore: (1) the career development of middle-aged male New Zealand immigrants who are engaged in the Australian gig economy, and (2) some of the intersecting dimensions of immigration with gig work and career development.

Method

A qualitative multiple case study design through semi-structured interviews was used. Qualitative research assists researchers to get close to the narratives and experiences of participants (Merriam, Citation2009). Multiple case study design provides a greater understanding of the range of possible narratives (Yin, Citation2017) and various systems of influence on the career development of middle-aged NZ immigrant gig workers. Each participant provides a unique understanding of the phenomenon being investigated (Creswell & Poth, Citation2016), and multiple people provide a triangulation of data that provides a richer description of participants’ work experiences and career progressions in the context of their migration.

Recruitment and participants

After ethical approval was granted from the university ethics committee (GU Ref No: 2019/984), a non-random purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit four middle-aged NZ immigrants working in the gig economy, via social media (e.g. in five major Facebook community pages of the Australian rideshare drivers). All volunteers were provided with a participation information sheet that included an informed consent form and were asked to return the signed consent form to the second author by email if they want to participate. The inclusion criteria were middle-aged (between 35 and 65) male participants who have immigrated from NZ in the last 10 years. Only male participants were considered as they dominate the Australian rideshare industry (Alexander et al., Citation2022). Given that female drivers constitute less than ten percent of rideshare drivers in Australia, it is important to consider their unique context through dedicating a separate research project that specifically focuses on their unique employment and career development contexts. In this research, we decided to limit participation to males, to avoid attending to an overly broad range of lived experiences and narratives, such as those related to gender discrimination and career development challenges more specific to women (Bimrose et al., Citation2014; Yakushko & Morgan-Consoli, Citation2014), which deserve a more dedicated focus through a separate project. Keeping the focus on males was aligned with guidelines about narrowing down the scope of research in qualitative research. After keeping the recruitment advertisements open for more than a month, only four participants returned their signed consent forms. Participants were aged between 48 and 59. All participants were engaged on the Uber platform; one was also engaged on Didi (another rideshare platform) and one also completed gigs on Airtasker. Each participant received AUD25 as a token of appreciation for taking the time to participate in the interview. provides participants’ demographics. More details about the participants and their backgrounds are outlined later in the findings section.

Table 1. Participants’ demographics.

Instrument and data collection

The STF of career development that theoretically informed this qualitative case study research promotes systems thinking (McMahon & Patton, Citation2018). Systems thinking complements narrative approaches to career research, which highlight the importance of seeing wholes and parts through the facilitation of career storytelling. As such, a semi-structured interview informed by the STF of career development facilitated the exploration of participants’ career development, education levels, individual characteristics, social systems, and migration context. After gathering demographic information and some inquiries about the migration story of each participant, the interview protocol directly incorporated elements of the STF of career development (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021). These questions intended to encourage participants in telling life-career stories through which their narratives of migration, gig work and career development could emerge under each of the STF of career development’s systems of influence. The interview protocol was piloted with one single participant who attended two interviews and included five key areas:

Demographics and the migration context (5 questions).

The self, including education, career background/history, and individual characteristics (12 questions).

Environmental-societal systems, including employment experiences and the experience of gig economy work (19 questions).

Social systems, including personal, cultural backgrounds, and values (11 questions).

Chance events (2 questions).

Interviews were conducted online via Zoom and lasted between one to two hours. The second author conducted all interviews and transcribed them verbatim. All participants were provided with a de-identified copy of the transcripts of the semi-structured interview to read and modify if needed.

Role of the researchers

Qualitative research that prioritises storytelling, emphasises the relational nature of research, particularly when inquiring about life histories becomes a central component of data collection and analysis (Yin, Citation2017). This highlights the importance of researchers’ reflexivity from the initial stages of study design and conception to data analysis. Part of this involves an acknowledgment of the researchers’ social location and background and what influenced their dedication to the project. The lead author (Peyman) conceptualised the research project, applied for ethical clearance and discussed the research aims and methods with the second author (Mark), and wrote the bulk of the manuscript. Mark, who was completing this research project as part of his Honours degree in a Bachelor of Psychology programme, recruited the participants, conducted the interviews, and completed the initial stages of data analysis and was engaged in some of the writing. Throughout these stages, the two authors conducted several meetings to strategically plan the project, apply for ethical clearance, discuss potential biases and views about the project and safeguard against complexities that may arise throughout the stages of data collection and analysis. Both authors kept a brief reflective journal in which they noted their reflections after each meeting. The second author also consistently reflected on his experiences during the processes of recruiting participants and collecting data.

As a non-white, middle-aged, male migrant from the middle east, with a relatively privileged migration journey, I (Peyman) have always been fascinated with the intersections of immigrational experiences with other aspects of post-migration life, including work and career development. Being concerned for other migrants who are not as privileged as me, this curiosity was predominantly influenced by my personal values of social justice. Over the past ten years, the bulk of my research focused on possibilities for promoting a career development discourse for refugees in their post-migration context. This preoccupation, however, has left me wondering (sometimes through questions and responses that I get from colleagues) about the challenges that migration poses for other less-disadvantaged migrant groups, such as those who move from one economically developed country to another (e.g. from NZ to Australia). I knew that many immigrants from economically developed countries also engage with app-based gig work such as ridesharing. On the other hand, as a white, middle-aged, non-migrant male, Mark (the second author) had some different perspectives about immigration and its intersections with other aspects of post-migration life. While neither of us worked as a gig worker using app-based gig work such as ridesharing, this research project became a reflective opportunity in which we learned about some of our biases and expanded our perspectives about the intersections of migration with work (more particularly gig work) and career development. In this reflective process, we were both conscious of our several conversational experiences with friends or people who were rideshare drivers about their immigrational experiences, its intersections with work and intentions or backgrounds that led to their decision of doing gig work after immigration.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness ensures rigour and consistency in qualitative research. The trustworthiness of the research was assured by applying the four criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1999). From the conception of the research topic to data analysis, the research team met regularly to discuss and reflect on the conception and theoretical aspects of the project and its design, recruitment, interview protocol, the analytical strategies, and to reach consensus. Other strategies included voluntary participants’ member-checking, using reflexive processes prior to and throughout the different stages of research conception and design, ethics application, data collection and analysis to enhance confirmability. Some of these reflexive processes and their outcomes were explained in previous sections (e.g. role of the researchers).

Data analysis

To systemically explore the career development of participants and the intersecting dimensions of their immigration with gig work and career development, a theory-driven deductive thematic analysis based on the STF of career development was applied. The six categories for systems and influences described in the STF of career development (i.e. individual, social, environmental-societal, change over time, recursiveness, and chance; Patton & McMahon, Citation2021) were used to guide this deductive analysis. First, each author separately read each transcript once to become more familiar with each participant’s overall story while reflecting on the systems of influence shaping their career development and its complexities after migration. Then, the second author began colour-coding all excerpts that reflected one or a few of the six systems of influence. For this purpose, the second author read each transcript at least two more times to ensure a more accurate understanding of the content and its relevance to systems of influence. Each colour-coded transcript was then sent to the first author for a review, after which the two authors met at least once over each transcript to reach coding consensus. A separate spreadsheet was then developed for each participant and excerpts related to each of the six systems of influence were listed separately. Finally, each of the authors independently explored the content of each participant’s spreadsheet and the systems that shaped or disrupted their career development after resettling in Australia. Then, the second author initiated a thematic analysis using the “six phases of thematic analysis” (Braun et al., Citation2019, p. 852). This six-phase process was not entirely linear and as recommended was “reflexive and recursive” (Braun et al., Citation2019, p. 853). First, the two authors familiarised themselves with the data by reading the transcripts and the Excel sheets and listening to the audio recording of each interview. The second author generated initial codes as phase two and then after cross-checking with the first author initiated phase three which was searching for themes among agreed codes. In phase four, potential themes were reviewed by the two authors as they regularly met to reach a consensus. Phase five involved the defining and finalising of themes before phase six, which involved producing a report followed by the write-up of the discussion section. As such, this time an inductive approach to thematic analysis was used to reach new codes that reveal some aspects of the participants’ career development in their post-migration context and its intersections with gig work. In deciding about the emerging themes, the authors were cognisant of the two research aims. Five major themes emerged in relation to the two aims of this research (two for aim one and three for aim two), which will be reviewed in the discussion section.

Findings

The four participants lived in different contexts and cultures as they performed gig work and provided a range of stories. A brief introduction to the participants’ career development in the context of their migration journey is presented first, and then the findings related to the six categories of the STF of career development are presented.

Introducing the participants

Robb

Robb was born in NZ. After graduating from High School, he worked in the insurance industry for a few years before working in the telecommunications industry for the next twenty years. In 2011, Robb and his wife migrated to Australia for family reasons. Upon arrival, they decided to look for work in Australia. A telecommunications company was advertising, so Robb applied and was successful and worked there for five years in a variety of roles until he decides to eventually quit his role. In 2016, Robb started part-time with Uber and shortly after went full-time. Robb’s wife has wanted him to stop driving for Uber for several years. However, he enjoys it. At the time of the interview, Robb who was 59 years old, had been applying for other employment without success.

Dave

Dave was born in NZ. After high school, he worked various jobs for different training companies. At 26 he enrolled in university to study education, and subsequently, worked as a high school teacher for seven years prior to immigrating to Australia with his family in 2009. He was considering a change in career after migration, as he felt burnt out. Dave worked in part-time jobs such as cleaning, security, and eventually relief teaching. After several years, Dave decided to resume his teaching career full-time, while working in security part-time on weekends for extra income. When Uber emerged in Australia, Dave replaced security work with driving. At the age of 48, Dave’s main career is still teaching, but mostly part-time work is available for him. Uber driving is extra income to help him prepare financially for the future.

Jeff

Jeff was born in Newcastle, Australia, immigrated to NZ when he was 23, and returned to Australia after 30 years. After secondary school, Jeff began work in sales in the engineering industry and changed industries several times including radio, professional sport, insurance, and management. After moving back to Australia, he worked in management until work circumstances forced him to resign. Jeff subsequently started working with Uber, and at the age of 56, plans to continue until he could find another opportunity in management.

Larry

Larry was born in India, migrated to NZ with his family when he was 14, became a NZ citizen, and subsequently moved to Australia. Larry completed a Commerce degree, worked in the financial and insurance sectors, and has owned several businesses. In Australia, he purchased a transport company that he now manages part-time and drives for Uber when he can. At first, he enjoyed the gig work. However, as Uber has grown, his work and earnings have significantly decreased. At the age of 54, he no longer enjoys driving for Uber, and the pandemic has given him an excuse not to do it anymore.

Systemic influences on participants’ career development

We highlight that this research didn’t want to make a claim about which “systems of influence” (among the six) are more dominant, rather it was about placing the participants’ narratives within each of these six systems of influence’s context to illustrate the possibilities that a systemic exploration offers for understanding career development in context. As such, the six categories of the STF of career development, the individual system, the social system, the environmental societal system, recursiveness, change over time and chance (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021) are reported in turn and supported, where appropriate, with representative statements.

The individual system

As a young man, Robb developed a strong value system around service and honesty: “I have always felt strongly about doing the right thing” … “I always try to enjoy the moment” … “my motivating force is my positiveness, my church beliefs, and belief in God” (values, beliefs) and he places a high value on relationships. These values developed from his cultural heritage, religious upbringing, and working for over 20 years in customer service: “I am a person who likes to serve and help people out, without expecting anything in return … like being a good Samaritan” … “I’m interested in developing my personal character” (self-concept, world of work knowledge, abilities, skills). Robb enjoys working for Uber, and because of all his experiences is now considering becoming a psychologist: “I see the problems in the community through my interactions with customers, and that has given me the idea to study psychology” (self-concept, interests).

Dave migrated to Australia with the plan to change professions. However, the global financial crisis thwarted his plans: “I have a Bachelor’s degree in education and a post-graduate diploma in teaching … I was burned out … and looking for a change” (health). Dave began Uber driving because: “it’s easier than security work, and it pays better”. He emphasised the extra income, possibilities for communication skills improvement, a better understanding of digital platforms, and how Uber work helped him to realise that teaching is his main career:

[it] has enabled me to improve my communication skills … helped to pay off some debt … it can be dangerous but I’m a male and have a bit of size … I’ve worked security in the past … I’ve upgraded my skills … [I realised that] the gig work doesn’t have a bearing on my career. (self-concept, aptitudes, ability, skills, gender, physical attributes, world of work knowledge)

Jeff’s various roles in sales and management along with his sporting career have given him a strong work ethic and a high degree of confidence: “I see everything as an opportunity and also like to challenge people and myself” (aptitudes, values, skills). His goal-orientated nature at work has helped him progress in a variety of roles throughout his career: “You always work hard … and take advantage of the opportunities” … “you need a clear vision and purpose in your work” … “I’m a problem solver” (personality, beliefs, values). One of his core values is empathy which he felt could be a strength or a weakness: “Empathy is very important. It has helped in my career, and it may have hindered me in my last job” ... “they felt I was investing too much time with some individuals, but I didn’t agree, so I resigned”.

Jeff does not consider the gig economy as a long-term prospect in his career plans but he is concerned about obtaining new employment because of his age and formal education: “I won’t do this forever … for the moment it pays the bills” … “I am worried about my age and gaining new employment” … “ … wondering if I should have gone to University” (age, qualifications, skills).

Larry’s skills and abilities have enabled him to purchase a business upon migration (ability, personality, self-concept, world of work knowledge, aptitudes). Larry is extroverted, makes friends easily, and feels he is a good judge of character: “I make friends easily and I can read people easily”. Initially he enjoyed working with Uber, but he refuses to tell anyone what he does for work: “I don’t feel comfortable telling someone I drive for Uber … it is low-class work” (perceptions, values). He considers that his age and ethnicity have disadvantaged his career development in Australia: “I have never considered it [Uber] a career … it’s difficult for me [work in Australia] with my Indian background, and accent … I feel a lot of racial discrimination plus my age is against me now” (age, ethnicity).

The social system

The social system in the STF of career development represents the social influences with which individuals interact directly (see ), or from which they receive input (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021).

Robb’s primary migration reason was family relationships: “we hadn’t heard from our son for a long time” (family). His previous work experience enabled him to get an equivalent job in Australia (workplace). He was also keen to improve his qualifications with every job opportunity he received: “I enrolled into TAFE … a basic mining course” … “I completed two diplomas while I worked for the RTO” (educational institutions). Interactions with co-workers are important for Robb: “After two years, I only know two Uber drivers” (peers). He is very involved with his church and community groups so the lack of peer support at work is balanced this way: “I do lots of volunteer work at church”. Uber driving gives Robb a sense of community service because he uses his life experiences and faith-based values to help: “I transport a lot of drugged and drunk people and they often open up to me” (workplace, customers, community groups).

With strong role models, Dave grew up in “a very supportive family” where education was a priority. Gig work is only for extra income and a better lifestyle: “teaching is my profession and Uber’s just a little extra cash” (family, workplace, education institutions).

Growing up in a single-parent home, Jeff’s mother set a strong example for his developing work ethic (family). His career has involved several different industries and workplaces: “I’ve had a good amount of industry training” (workplace). Playing sport at a high level helped Jeff develop a strong sense of teamwork and organisational goal achievement: “I played in the Australian Rugby League … I am very driven by organisational goals” (peers, community groups, workplace). This helped him to obtain management and leadership opportunities. Working in the gig economy has given Jeff some relief and more flexibility compared to his previous corporate career: “Uber is a relatively stress-free role compared to my previous roles … I’m really enjoying the relatively stress-free work” (workplace).

After arriving in Australia, and setting up his own business, Larry craved social connection, so he decided driving for Uber might solve this challenge: “I have found it really difficult to make friends in this country … Uber gave me an opportunity to talk to people, which I longed for” (peers, community groups, workplace). Subsequently, he did not enjoy driving because there are too many drivers and not enough work: “I thought Uber was the best company in the world, but not anymore” (workplace). His migration journey to Australia has been difficult financially, emotionally, and socially and he appreciates strong support from his wife and his son: “ … my wife and son are a great support” (family).

The environmental-societal system

Society and the environment also impact and influence the individual. They may seem less direct (see ), but they can have a profound effect on the individual’s career development (McMahon & Patton, Citation2018).

Since migrating to Australia, Robb has always been employed which is fortunate because NZ immigrants cannot receive unemployment benefits until they have lived continuously in Australia for 10 years. He expressed his displeasure about this condition: “I can’t get the unemployment support … I can’t get HECs (student loan). It’s ridiculous that the government won’t give us these benefits” (political decisions, employment market, historical trends, geographical location).

Dave’s move to Australia was partially related to the NZ economy: “I was discouraged by the economy in NZ … I knew my qualifications would mean employment in Australia” (political decisions, employment market). His motivation to work for Uber was to pay off some accumulated debt: “I needed to pay off some debt” (socioeconomic status).

The employment market can have positive and negative effects on a career. This was evident in two of Jeff’s workplaces because in New Zealand “deregulation opened up the market to new entrepreneurs” and despite opportunities in the market for some, it led to some complexities for Jeff (globalisation, geographical location, employment market, political decisions). A large-scale merger of two companies gave Jeff extra managerial responsibilities which caused his burnout: “It all became a bit too much” (globalisation).

Larry expressed that with his Indian heritage he has experiened certain career development challenges in Australia: “Doing work and business in Australia has been one of my biggest obstacles … but there was discrimination and racism, which I didn’t notice in NZ” (employment market, geographical location). All participants noted the major systemic influence of the global pandemic on their work and career development.

Change over time

Career development is a dynamic process involving ongoing decision-making and transitions. For the participants, the complexity and challenge of immigration introduced new changes in their careers.

Robb explained how prior to migration, he had very stable employment but how things changed after migration: “I’ve had so many jobs since moving here, but it’s been an upward journey, I think each one has been better” and “I’ve earned more qualifications since moving to Australia”.

Dave explained how he was looking for “a change in lifestyle, a change in scenery, and change in opportunity” but was worried about his age, because “as you get older it’s counted against you”. He was also aware that change in market forces and technological changes over time, especially with the necessities that the global pandemic introduced, has affected the relevance of the gig economy: “We are governed by [the health of] the economy” and how “ … without GPS, smartphones, this job [Uber] wouldn’t exist”.

Jeff had experienced many changes in the industries he has worked in over his career which always provided him with opportunities and were positive for his career development. Since Uber driving, Jeff has experienced some personal changes:

I’m not as hard-nosed as I used to be. I have much more empathy for people … one of the conflicts in my last role was the board felt I was wasting time on some people … I enjoy listening, helping, and relating to the people. Uber has been great for that.

Chance

Chance is defined as “an unplanned event that measurably alters one’s behaviour” (Miller, Citation1983, p. 17), and is sometimes referred to as luck, fortune, accident, or happenstance. Chance also plays a role in career development. It can be unpredictable, but its influence can be profound (McMahon & Patton, Citation2018). For three participants, chance events, mainly through relationships with others, had resulted in opportunities for them because they took them up. By contrast, Larry, who does not mix in any community groups and has found migration challenging could not recount any chance events which played out in different ways. For example, since migration, Robb’s career development has involved multiple chance events that he attributes to relationships he developed in Australia: “I’ve taken advantage of educational opportunities … and met various people that have offered me [work] opportunities” … “It’s the actual friendships that I’ve developed that make these chance events happen”.

Dave’s first job in Australia was by chance through a friend he met at a funeral: “He helped me get a security license and gave me some work”. Another friend suggested Uber to him, and he now states: “ … it’s worked out great. It’s better than standing on your feet all day and night”. Similarly, Jeff, who had not considered Uber driving until his daughter mentioned it to him “found it very therapeutic”.

Recursiveness

Recursiveness is the interaction within and between the STF’s systems of influence (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021). Recursiveness between influences is evident in many instances of the participant’s career stories. Indeed, migration itself and the emergence of gig work, such as Uber driving, is an example of the recursiveness of the environmental-societal system and change over time. An example for each of the participants will be presented here and the recursive systems of influence italicised in brackets after the examples.

Robb’s family relationships were the catalyst for his migration: “we moved to be with our son” (social, environmental-societal). Since his migration and his Uber driving, he realised new career aspirations by listening to his passengers: “There are so many individuals with problems” … “I always want to help people” … “I might study psychology” (individual, social, environmental-societal, chance, change over time).

Dave recounted how education was a priority in his family, and he became a teacher as his mother was a teacher. Despite wanting to move out of teaching, the financial hardship created by the crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic inspired him to conclude that teaching was his best career direction: “I know it’s best to stay in this field [teaching]” (social, change over time, environmental-societal).

Jeff attributed the values imparted by his mother related to hard work and responsibility to his career progression into senior management roles: “I’ve always had good roles” (individual, social, change over time, environmental-societal). These opportunities also created stress and burnout, and the shift to working in the gig economy has acted as a reset button for his career: “It’s [gig work] been therapeutic” (individual, social). His geographical location has also been an advantage: “Living close to the airport has been excellent” (environmental-societal).

Larry’s ethnicity has impacted him during his gig work and he has experienced negative stereotypes, discrimination and racism: “the [implicit] racism has been a challenge” (social, individual). His experience of Uber driving in Australia, although positive at first, worsened with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic until he decided not to drive anymore because “COVID-19 has made it unsafe”. In addition, he described Uber driving as “ low-class work” that he felt ashamed of and wouldn’t call it a career or tell anyone he works for Uber … (change over time, individual; environmental-societal). The recursive interaction between various systems of influence appears evident in all participant’s stories and illustrates the diversity of the range of influences in their career development. Post-migration, the two major domains of resettlement and Uber driving gig work experiences have been heavily influential in their career development.

Discussion

The findings highlight the value of systemic qualitative research for obtaining a comprehensive, context-sensitive and nuanced understanding of the career development of male middle-aged immigrants from economically developed countries working in the Australian gig economy. The value of using the STF of career development in this research is illustrated through the provision of a holistic view of dominant influences that shape these participants’ career development across the systems (see ).

In this way, the STF of career development enriched this research both through the data collection method, as well as offering a systemic analytical lens. In attending to the aims of this research, such theory-driven deductive thematic analysis of the participants’ narratives provided the researchers with an enhanced understanding of their career development in the context of their migration journeys. By further reflecting on the findings of the systemic analysis, and linking these findings with career development literature, the two aims of this research are reviewed through an outline of the emergent themes (from the inductive analysis) relevant to each aim. First, a discussion of the career development of these middle-aged NZ immigrants working in the Australian gig economy that emerged through a systemic qualitative exploration are highlighted (with three emergent themes). After that, the second part of this discussion corresponds with the second aim of this research and overviews a few of the intersections of immigration, gig work with these immigrants’ career development (with two emergent themes).

The career development of middle-aged NZ immigrants working in the gig economy

One of the aims of this research was to explore the career development of middle-aged male NZ immigrants who work in the gig economy. All four participants’ career development was somewhat impacted after immigration as they entered gig work looking for similar benefits, such as material outcomes, flexibility, and social experience. Upon immigration from NZ, none of the participants anticipated that they will be engaging in gig work in Australia. Ridesharing companies’ promotion of flexibility accompanied by initial support from family and peers (social), or combined with the demands of a changing employment market (environmental-societal) gave participants the impetus to start gig work. The life-career stories of these participants often reflected a degree of employment volition prior to their decision of starting app-based gig work that might be absent from the narratives of other migrant groups, such as those from economically developing countries or refugees. However, their narratives illustrated a number of compromises (trade-offs) that they made as they continued to work in the gig economy. When compromise is needed, often the fields of interest, personal priorities and career values are sacrificed (Brott, Citation2006) and this is somewhat reflective of participants’ experiences who had to sacrifice their career interests and aspirations to engage in gig work. Finally, the participants of this research might be at a stage where they begin to reduce or eliminate career opportunities due to their age. Therefore, such trade-offs seemed to be supported by the construction of a temporary occupational identity that allowed them to continue gig work. The impact of these trade-offs and the adjustment in career identity were the two emergent themes related to the first aim that will be discussed by considering the participants’ lived experiences in the next two sections.

Career development trade-offs of working in the gig economy

One of the themes that emerged was related to trade-offs and career sacrifices that potentially highlight the precarious nature of gig work (Ornek et al., Citation2020) versus its potential earning capacity, the flexibility of work schedule, and its social experience (Josserand & Kaine, Citation2019). Three major types of trade-offs were noted.

Flexibility versus autonomy

All four participants’ narratives emphasised gig work flexibility and autonomy. Such flexibility appeared as an entrepreneurial sense. However, a large part of entrepreneurship is autonomy (Kaine & Josserand, Citation2019). The irony here is that Uber has constant surveillance and stringent controls over all drivers’ work activities (Josserand & Kaine, Citation2019). Pay rates and expenses can change without prior notice and the work distribution is determined by algorithmic equations over which the driver has no control, can be terminated without explanations, or receive no task at any time (Josserand & Kaine, Citation2019). This may be an implicit trade-off and could be an example of the gig economy having more influence on the individuals’ career, without the person recognising it. The individual feels like they are in control, however, they have very little control; a position that is also examined in other research, and which explains how the ride-sharing industry maintains these successful engagements (Josserand & Kaine, Citation2019).

The STF of career development helped deconstruct such narratives, highlighting the recursive nature of the interactions between the individual, social, and environmental-societal systems. This may provide an initial indication that changes in the employment market, the growth of globalisation, and the rapid rate of technological advancements are exerting greater control over individual career decisions when they intersect with gig work.

Positive social experience versus negative social experience

The social experience of doing gig work was also emphasised by participants as a positive aspect of their ridesharing work. For example, meeting people, listening to their stories and providing an essential service brought a sense of connection and reward. This aspect of gig work (and particularly ridesharing) is heavily linked with “work as a means of social connection”, as one of the major roles that work plays in people’s lives (Blustein, Citation2013, p. 86). Despite this, through engaging in app-based gig work, all four participants faced some forms of complexities in social interactions with customers (e.g. intoxicated by alcohol or drugs, verbal abuse, or sexual harassment). Rideshare gig work often involves working long hours, usually nights and weekends, which heavily impacts family commitments and social lives (Ornek et al., Citation2020). These negative social experiences add to the precarious nature of gig work and are part of the compromise of working in the gig economy.

Gig work versus traditional work

Often, the financial outcomes of gig work are challenged by the lack of safety net that traditional work provided (Kaine & Josserand, Citation2019). Additionally, in many countries such as Australia, various characteristics of app-based gig work such as an absence of ongoing training, health and retirement benefits, social insurance, fluctuations in the number of available gigs and uncertain work hours jeopardise income and possibilities for stability and planning (Kaine & Josserand, Citation2019; Malos et al., Citation2018). In turn, narratives of flexibility, autonomy, and social experience could mask such realities of gig work. This type of cognitive dissonance may illustrate how certain systemic influences gain more power and impact following a transition from traditional employment to gig work. Another possible finding that follows from the trade-off discussion is how gig workers re-formulate their sense of occupational identity and its impact on their longer-term career development (Stewart & Stanford, Citation2017).

Constructing a self-narrative of occupational identity

People often have a certain image of what their occupation should look like, how they position themselves in a certain occupation and what meaning they ascribe to their lives and ways of being in such context. This overall sense of identity provides comfort and security, helps people to make decisions, guides their vocational behaviour and finally provides social meaningfulness (Cohen, Citation2020). As in many countries, gig workers are not formal employees, but they are also not contractors under the legal definitions (Minter, Citation2017), it is often difficult for them to construct an occupational identity, because of such ambiguities around legal employment classifications, as well as the blurry social status of gig work in society. For example, two of the participants stated that they don’t feel comfortable sharing it with their friends or relatives that they engage in ride-sharing work. Such ambiguities potentially lead to the development and strengthening of some personas to help construct an occupational identity as Josserand and Kaine (Citation2019) introduced varied identities of ride-share drivers. Despite the temporariness of gig work that is reflected through such personas they allow people to cope with the precarious nature of gig work (Josserand & Kaine, Citation2019). These narratives delineate the change over time and the recursiveness that gig work may have on personal experiences and subsequently on career development. The “change over time” in occupational identity seemed a dominant theme of all participants’ narratives. All were enthusiastic to start work in the gig economy, but over time and with the recursive nature of influences from the social and individual systems, their enthusiasm waned. As a result, all participants plan to discard ridesharing in the future (one already has). Their reasons included ethical reservations, social and family pressure, and material conditions. Such occupational identity volatility seems to disrupt the career development of those working full time in the gig economy. The second aim of this research was to explore some of the intersecting dimensions of immigration with gig work and career development.

The intersecting dimensions of immigration with gig work and career development

A challenging career development might intersect with immigration challenges, leading to work in the gig economy that might introduce new complexities for immigrants. Australian “skilled migration” programme remained constant during the five-year period before the COVID-19 pandemic, attracting approximately 200,000 immigrants per year (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2020). However, the findings of this case study research confirm previous research that even skilled migrants from economically developed countries face several challenges and complexities as they transition into a new country and try to navigate the murky waters of employment in a new environment (Breen, Citation2016; Faaliyat et al., Citation2021). STF of career development provides a rich opportunity to analyse the recursiveness of the multiple systems of influence that support or disrupt immigrants’ career development and their interactions with other post-migration contextual factors.

Immigration context of Australia and community groups: a sense of belonging

Migration programmes across economically developed nations are designed to fill gaps in local labour markets (Wright, Citation2012), and counteract declining birth rates and aging populations (Phan et al., Citation2015). It is expected that Australia’s “skilled migration program” will significantly boost the number of skilled immigrants who enter the Australian labour force by 2024–2025 (Australian Government, Citation2021). However, skilled migrants’ career development challenges and finding stable and relevant employment are not considered in such programmes. Factors such as discrimination (Du Plooy et al., Citation2019), lack of familiarity with the recruitment processes (Ressia et al., Citation2017), workplace exploitation (Fels & Cousins, Citation2019), and educational qualifications transferability and qualification-matched employment (Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2019) are among factors that impact immigrants’ employment in their preferred areas of work, and as such disrupt their career development. However, certain factors may contribute to less challenging career development in Australia for immigrants who come from economically developed countries (or those who easily identify with the Australian predominant white Anglo and English-speaking community).

The narratives of participants in this study revealed how the participants had established connections before and after migration with the community, and how such connections contributed to increased job opportunities. Such possibilities for greater social integration and acculturation are partially related to the role of language and have been shown to contribute to career development post-migration for English-speaking immigrants (Booth et al., Citation2012; Hawthorne, Citation2016). These systems of influence (community groups & chance) helped reduce isolation and provided a sense of belonging, leading to improved well-being despite being engaged in gig work. Pre-migration educational qualifications were another factor that emerged through the participants’ narratives which seemed to smooth post-migration career challenges when intersecting with gig work.

Educational qualifications

Education levels determine levels of employment, and this could decide a person’s economic conditions and social status (Vijay & Nair, Citation2017). The findings of this research revealed how completion of tertiary education prior to migration seemed to have a positive impact on NZ immigrants’ career development even when the person is involved in gig work. This is consistent with other research that states human capital, which is made up of skill, knowledge, education and experience, attained pre-migration is a predictor of career success post-migration (Tharmaseelan et al., Citation2010). Those with this status could use gig work to meet their material outcome needs, while still maintaining their primary career or pursuing more relevant or stable work. Without tertiary education career opportunities are restricted after the migration (Breen, Citation2016), which potentially could increase reliance on gig work, further disadvantaging career development. However, easier recognition of previous tertiary education qualifications is an advantage for immigrants who come from economically developed countries, such as New Zealand, and may not be the case for all immigrants (Parliament of Australia, Citation2020). Legislative complexities such as accreditation of qualifications are part of the contextual constraints that many immigrants face with their career development after the migration (Breen, Citation2016). Such complexities that limit career development for many immigrants combined with the precarious nature of gig work could lead to downward occupational mobility.

Downward occupational mobility

Many groups of immigrants expect that migration will lead to better employment outcomes and increased economic opportunities (Ressia et al., Citation2016). Such a theme was evident in every interview. However, it is debatable whether better employment outcomes and increased economic opportunity were achieved for participants. The participants’ career stories reflect that downward occupational mobility, defined as “a transition to lower-status and lower-paid employment” (Ressia et al., Citation2016, p. 66), is also applicable to skilled migrants from economically developed countries, as their post-migration educational and occupational attainments suffer (Ho & Alcorso, Citation2004). Therefore, the complexities of finding and maintaining stable employment post-migration and the ease of obtaining gig work could possibly exacerbate this downward occupational mobility and negatively impact sustainable career development. This means that engaging in gig work after migration could operate as a disruptive element for the career development of people as it does not contribute to the development of further career-related skills (Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022; van Doorn & Vijay, Citation2021). Immigrants’ career development is then further interrupted, as returning to traditional employment (in an area where the person might have worked for years) might then become more challenging (Ornek et al., Citation2020).

Limitations and future research

As a qualitative exploratory case study research in which data were analysed predominantly through a theory-driven deductive thematic analysis based on the STF of career development, this research didn’t intend to be inductive and make inferences of general laws from particular instances. We acknowledge that for an extremely heterogeneous group such as immigrants, the intersections of migration with other aspects of post-migration life, such as career development, is a multifaceted and diverse space in which making generalisable claims is not possible. Instead, the findings intended to offer a nuanced qualitative understanding of how systemic influences operated in the pre- and post-migration life spaces of these specific immigrants and need to be considered in light of the small sample size and its case study nature. The participant pool only consisted of male drivers. We highlight that although the gig economy is highly segregated, and the ride-sharing platforms in Australia are male-dominated (Churchill & Craig, Citation2019), more women are also emerging as rideshare drivers. However, we preferred to narrow our focus and leave the exploration of immigrant women’s career development when it intersects with gig work to future research. Another limitation that needs to be acknowledged relates to the existence of various types of gig work, while this research only focused on ridesharing. Finally, the interviews were to be conducted face to face, but due to the restriction imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, they were conducted online. This might have reduced the quality of the researcher-researched relationship and how comfortable the participants felt to share personal experiences (Hewitt, Citation2007). Future career research on the intersections of gig work and migration might consider further qualitative and quantitative studies with other immigrant populations, such as females, non-English speaking and other cultural backgrounds, as they might experience various other types of complexities.

Implications

With the emergence of the gig economy, and migrants standing at its forefront in economically developed countries such as Australia, further exploration into the subjective experiences of various groups of migrant workers (e.g. age, gender, migration pathway) and the resources available to them for more sustainable career development is warranted (Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022; Hirschi, Citation2018). The current research took a step toward the disentangling of the intersections of gig work, migration, and career development (Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022), and therefore, has implications for career development and vocational psychology research as it offers a new perspective on such intersecting boundaries about a particular migrant group. By acknowledging the heterogeneity of migrants who engage in gig work and narrowing down its focus, this research contributed to the “plural systems of knowledges” (Sultana, Citation2021, p. 5) that are required for understanding such intersections by prioritising “localisms and particularisms” (Sultana, Citation2021, p. 2) through systemically exploring experience-near narratives of New Zealand migrants in Australia. While career research is starting to pay attention to the sustainable career development needs of migrant gig workers (Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022; Spurk & Straub, Citation2020) and the intersections of such work-life spaces with other aspects of post-migration life, career practice is encouraged to look for pathways to engage and support their career development needs (Abkhezr & McMahon, Citation2022). However, a stronger connection between career research and practice is essential. Advancing further research that aims to substantiate the fields of career development and vocational psychology’s understanding of the varied lived experiences and local and particular knowledges of immigrant gig workers about career development seems vital. This research was one such step towards substantiating a heterogenous understanding of the intersections of gig work with migration and career development. An accumulation of further experience-near and local research with diverse groups of immigrants could provide a more robust consideration of pathways and policies that could address the potentially precarious nature of gig work and offer possibilities for supporting migrant gig workers’ sustainable career development. Finally, this research highlighted the role of the STF of career development (Patton & McMahon, Citation2021) through the possibilities that systemic explorations and qualitative career assessments informed by the STF provide for career practice. The STF of career development as a metatheoretical framework unpacks the role of various influences in shaping the client’s career decisions of entering the gig economy or other influences that inform migrants’ future career plans (e.g. the client’s specific abilities, skills, or age and gender-specific circumstances from the individual systems, or the role of family, peers and colleagues from the social system, or other environmental-societal influences or the role of chance and changes over time). Career counsellors who work with migrant gig workers could utilise systems mapping and systemic thinking in their practice to facilitate systemic explorations with their clients (McMahon & Patton, Citation2018).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions (e.g. their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Peyman Abkhezr

Peyman Abkhezr, BA, M.Couns, PhD, Lecturer, School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia. Dr Abkhezr is broadly interested in career development and counselling research. Prioritising a social justice approach in his work, Peyman is more invested in qualitative methodologies that highlight participants’ voices and stories, and generally approaches research relying on a social constructionist/constructivist epistemology. His research explores the career development and the working lives of a diverse range of people who work in a rapidly changing world of work and explores areas such as the career development of migrants, people who do precarious gig work, and the intersections of their working lives with other domains.

Mark Tang

Mark Tang, B.Psych (Hons), Honours Student, School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia. Mr Tang is currently a provisional psychologist in Australia and his research interests are career development of people who work in the gig economy.

References

- Abkhezr, P., & McMahon, M. (2022). The intersections of migration, app-based gig work, and career development: Implications for career practice and research. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09556-w

- Abkhezr, P., McMahon, M., & Campbell, M. (2022). A systemic and qualitative exploration of career adaptability among young people with refugee backgrounds. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-020-09446-z

- Abkhezr, P., McMahon, M., Glasheen, K., & Campbell, M. (2018). Finding voice through narrative storytelling: An exploration of the career development of young African females with refugee backgrounds. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 105, 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.09.007

- Abkhezr, P., McMahon, M., & Rossouw, P. (2015). Youth with refugee backgrounds in Australia: Contextual and practical considerations for career counsellors. Australian Journal of Career Development, 24(2), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416215584406

- Alexander, O., Borland, J., Charlton, A., & Singh, A. (2022). The labour market for Uber drivers in Australia. Australian Economic Review, 55(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12454

- Altenried, M. (2021). Mobile workers, contingent labour: Migration, the gig economy and the multiplication of labour. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211054846

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020, April 28). Migration, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Latestproducts/3412.0Main%20Features42017-18?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3412.0&issue=2017-18&num=&view=

- Australian Government. (2021). Planning Australia’s 2022–2023 Migration Program. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/how-to-engage-us-subsite/files/planning-australias-2022-23-migration-program.pdf

- Australian Government. (2023a). Skilled migration program. https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/what-we-do/skilled-migration-program/overview

- Australian Government. (2023b). New Zealand citizens. https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/entering-and-leaving-australia/new-zealand-citizens/overview

- Australian Parliament. (2021). First interim report: On-demand platform work in Australia. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2021-06/apo-nid312940.pdf

- Bimrose, J., McMahon, M., & Watson, M. B. (2014). Women’s career development throughout the lifespan: An international exploration. Routledge.

- Blustein, D. L. (2013). The Oxford handbook of the psychology of working. Oxford University Press.

- Blustein, D. L., & Duffy, R. D. (2020). Psychology of working theory. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (3rd ed., pp. 201–236). Wiley.

- Booth, A. L., Leigh, A., & Varganova, E. (2012). Does ethnic discrimination vary across minority groups? Evidence from a field experiment. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 74(4), 547–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2011.00664.x

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences, 843–860.

- Breen, F. (2016). Australian immigration policy in practice: A case study of skill recognition and qualification transferability amongst Irish 457 Visa holders. Australian Geographer, 47(4), 491–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2016.1220895

- Brott, P. E. (2006). Counselor education accountability: Training the effective professional school counselor. Professional School Counseling, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.5330/prsc.10.2.d61g0v3738863652

- Churchill, B., & Craig, L. (2019). Gender in the gig economy: Men and women using digital platforms to secure work in Australia. Journal of Sociology, 55(4), 741–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319894060

- Cohen, R. L. (2020). ‘We’re not like that’: Crusader and maverick occupational identity resistance. Sociological Research Online, 25(1), 136–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780419867959

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE.

- Dunwoodie, K., Due, C., Baker, S., Newman, A., & Tran, C. (2022). Supporting (or not) the career development of culturally and linguistically diverse migrants and refugees in universities: Insights from Australia. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 22(2), 467–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09506-y

- Du Plooy, D. R., Lyons, A., & Kashima, E. S. (2019). Predictors of flourishing and psychological distress among migrants to Australia: A dual continuum approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(2), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9961-7

- Faaliyat, N., Ressia, S., & Peetz, D. (2021). Employment incongruity and gender among Middle Eastern and North African skilled migrants in Australia. Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work, 31(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2021.1878571

- Fedrigo, L., Udayar, S., Toscanelli, C., Clot-Siegrist, E., Durante, F., & Masdonati, J. (2022). Young refugees’ and asylum seekers’ career choices: A qualitative investigation. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 22(2), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09460-9

- Fejes, A., Chamberland, M., & Sultana, R. G. (2022). Migration, educational and career guidance and social inclusion. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 22(2), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09493-0

- Fels, A., & Cousins, D. (2019). The migrant workers’ taskforce and the Australian government’s response to migrant worker wage exploitation. Journal of Australian Political Economy, 84, 13–45.

- Fleming, P., Rhodes, C., & Yu, K. (2019). On why Uber has not taken over the world. Economy and Society, 48(4), 488–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2019.1685744

- Graham, M., Hjorth, I., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2017). Digital labour and development: Impacts of global digital labour platforms and the gig economy on worker livelihoods. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 23(2), 135–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258916687250

- Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. (1999). Issues in educational research. Issues in Educational Research, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008043349-3/50014-1

- Hawthorne, L. (2016). Labour market outcomes for migrant professionals: Canada and Australia compared. Social Science Research Network. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2808943

- Helbling, L., & Kanji, S. (2018). Job insecurity: Differential effects of subjective and objective measures on life satisfaction trajectories of workers aged 27-30 in Germany. Social Indicators Research, 137(3), 1145–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1635-z

- Hewitt, J. (2007). Ethical components of researcher – Researched relationships in qualitative interviewing. Qualitative Health Research, 17(8), 1149–1159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307308305

- Hirschi, A. (2018). The fourth industrial revolution: Issues and implications for career research and practice. The Career Development Quarterly, 66(3), 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12142

- Ho, C., & Alcorso, C. (2004). Migrants and employment. Journal of Sociology, 40(3), 237–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783304045721

- Josserand, E., & Kaine, S. (2019). Different directions or the same route? The varied identities of ride-share drivers. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(4), 549–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185619848461

- Kaine, S., & Josserand, E. (2019). The organisation and experience of work in the gig economy. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(4), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185619865480

- Karp, P. (2023). New Zealanders to gain faster pathway to Australian citizenship under major changes to immigration rules. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/21/new-zealanders-to-gain-faster-pathway-to-australian-citizenship-under-major-changes-to-immigration-rules

- Koranyi, I., Jonsson, J., Rönnblad, T., Stockfelt, L., & Bodin, T. (2018). Precarious employment and occupational accidents and injuries – A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 44(4), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3720

- Kost, D., Fieseber, C., & Wong, S. I. (2020). Boundaryless careers in the gig economy: An oxymoron. Human Relations Management Journal, 30(1), 100–113.

- Kuhn, K. M., & Galloway, T. L. (2019). Expanding perspectives on gig work and gig workers. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 34(4), 186–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-05-2019-507

- Magnano, P., Zarbo, R., Zammitti, A., & Sgaramella, T. M. (2022). Approaches and strategies for understanding the career development needs of migrants and refugees: The potential of a systems-based narrative approach. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 22(2), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-020-09457-w