ABSTRACT

The field of performing arts presents an often unpredictable area for career development. Yet many people are drawn to this field as their chosen career trajectory. This study examines the life-career experiences that shape performing artists' trajectories within the framework of career construction theory. Using a qualitative multiple case study design, data was generated by Career Interest Profiles (CIP), career construction interviews (CCI), life-design counseling, and publicly available information. Thematic analysis uncovered two primary themes: the unique journey of performing artists in constructing their careers and the trajectory of career development, which highlights the factors influencing perceived success or failure and the essential 'survival skill set. The research offers theoretical insights and practical understanding of protean careers in demanding industries.

Introduction and literature review

Introduction

Performing arts constitute an uncertain field in which to develop and manage a planned career, fraught with risks, personal challenges, insecurities, conflicts, and constraints as performing artists need to juggle various roles and multiple jobs with no planned career opportunities resulting in performing artists having to manage their careers with all the moving parts thereof (Allen, Citation2022; Daniel, Citation2016; Daniel & Daniel, Citation2013; Inglis & Cray, Citation2012; Johnston, Citation2018; Thomson, Citation2013; Wyszomirski & Chang, Citation2017). For several performing artists, the stark reality of their daily existence calls for their involvement in multiple temporary jobs, once-off gigs, freelancing, moonlighting, “session work”, “pick up” ensembles, working on public grant projects, and moving between arts and non-arts jobs to make ends meet within a complex environment (Middleton & Middleton, Citation2017; Wyszomirski & Chang, Citation2017). They also experience the uncertainties of funding, the need for flexibility in working conditions, the need to develop their careers by building an artistic reputation (Inglis & Cray, Citation2012), entrepreneurship, and managing money and contracts, to mention but a few aspects (Allen, Citation2022; Bridgstock, Citation2005).

Dealing with the challenges explicated above constitutes a major challenge to the vast majority of performing artists. Performing artists’ career development and how they navigate the quest toward a performing arts career within a transformed industry amidst a complex environment is an underrepresented area of empirical research, with traditional career theories providing limited insights (Carey, Citation2015; Everts et al., Citation2022; Middleton & Middleton, Citation2017; Zwaan & Ter Bogt, Citation2009). Furthermore, research within the performing arts has mainly been done through economic lenses (Wacholtz & Wilgus, Citation2011), focusing on creative entrepreneurship (Bridgstock, Citation2011; Preece, Citation2011), creative entrepreneurship in higher education (Bridgstock, Citation2013) or the specific attributes (e.g. personality, cognition, memory, mobility and personality factors) of artists (Kogan, Citation2002) whilst focusing on quantitative, survey-tracking-based work that provides high-level generalisable findings in the creative sphere (Carey, Citation2015).

Literature and theoretical overview

The section will provide the theoretical framework for the study by first providing a rationale for the performing arts career as a protean career type. Hereafter, the term, performing artists, will be defined as applied in this study. Lastly, the contextual framework used for the study is highlighted.

The protean career type can be used to make sense of the above-described non-linear, flexible career path of performing artists as independent workers as they seek to reinvent themselves to meet changing circumstances and needs (Hall, Citation1996; Wyszomirski & Chang, Citation2017). Thus, performing artists experienced the new world of work that many other careers only experienced with the onset of the fourth economic wave and its associated changes in the globally integrated economy, accompanied by radical changes, complexities and connections, and where the metaphor of career has replaced the traditional career metaphor of climbing the corporate ladder as riding the waves (Maree, Citation2015b, Citation2020a; Pryor & Bright, Citation2011; Savickas, Citation2008, Citation2019a). Therefore, performing arts is an example of a non-traditional career setting, facing a non-traditional protean career path (Chopp & Kerr, 2008, as cited in Hall & Mirvis, Citation1996; Kerr & McKay, Citation2013).

In an attempt to provide a pragmatic, all-encompassing definition of performing artists fitting various contexts, the first author integrated descriptions and categorisations of multiple researchers (Brooks & Daniluk, Citation1998; Butler, Citation2000; Hume et al., Citation2007; Kerr & McKay, Citation2013; Kogan, Citation2002; Preece, Citation2011) leading to the description of performing artists as individuals, irrespective of gender or culture, who foremost identified themselves as performing artists (focusing on actors, musicians, and singers in any genre) and considered the pursuit and practice of their art to be of significant value and primary life activity. Furthermore, the individuals currently consider themselves active in their chosen artistic field and their role as performing artists as their primary career. Lastly, they regularly perform in front of an audience (even though they may or may not be the creator of the content of the performance) and have relevant experience in their chosen performing arts field.

In the contemporary world of work, the focus must be on individuals’ unique and subjective career development experiences (Coetzee et al., Citation2016), continuous learning and identity changes across their lifespans (Hall, Citation2013). Career Construction Theory (CCT) corresponds to the contextualised paradigm of post-modernity’s life-designing and answers the need for an alternative paradigm that focuses on performing artists as a protean career as artists adapt to ongoing events in a dynamic world. Two prominent theories relating to this paradigm are the system theory framework (STF) (Patton & McMahon, Citation1999, Citation2006, Citation2015) and career construction theory (Savickas, Citation2005, Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2019b, september).

Systems Theory Framework (STF)

The STF is a metatheoretical framework which values the whole, recognising contributions from all theories from a positivist and constructivist worldview. The STF represents the complex interplay of influences through which individuals construct their careers and emphasises both the content and process of career development while taking the unpredictability of career development through the inclusion of chance into account. The STF reflects the constructivist worldview, emphasising disorganisation, adaptation and reorganisation. The content and process influences are represented in the STF as many complex and interconnected systems within and between which career development occurs. Content influences include intrapersonal variables (such as self-concept, gender or interest), contextual variables (social influences such as peers or media), and environmental and societal influences (such as political decisions or globalisation) (Patton et al., Citation2017).

Career construction theory (CCT)

CCT is a metatheory grounded in the post-positivist epistemology of social constructionism (Savickas, Citation2005) as well as a narrative perspective with its roots in Super’s lifespan, life-space theory (Del Corso & Rehfuss, Citation2011; Savickas, Citation2013b, Citation2019a; Swanson, Citation2013). Individuals construct a subjective career to impose meaning and direction on their vocational behaviour (Savickas, Citation2005, Citation2013a, Citation2019a), guiding and carrying individuals across career transitions (Maree, Citation2015a, Citation2018; Savickas, Citation2013a). Careers are thus conceptualised as a story in which performing artists reveal the various projects that occupy them and of which they are the actors, agents, and authors within the theatre of work (Maree, Citation2020b; Savickas, Citation2013a).

CCT includes three critical aspects: identity, career adaptability and life themes (Savickas et al., Citation2009). The identity focuses on the “what” of career construction and includes individuals’ career-related abilities, needs, values, and interests (Savickas, Citation2019a; Savickas et al., Citation2009). Savickas (Citation2005) built on Super’s (Citation1957) initial concept of career maturity, referring to career adaptability as the “how” of career construction, which involves coping processes and resources individuals use to connect and construct their careers (Hartung & Cadaret, Citation2017; Savickas et al., Citation2009; Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012). How people adapt to specific experiences depends upon their problem-solving resources and strategies, which can be identified as the attitude, beliefs and competencies (ABCs) of career adaptability as it is applied to career adaptability’s four dimensions (career concern, control, curiosity and confidence). Lastly, life themes refer to the “why” or the motivational force of Career Construction (Savickas et al., Citation2009).

Life design counselling

Life-design counselling is premised on the concepts of identity (self), narratability of identity (story) and intentionality (meaningful action) (Lent, Citation2012). The focus of life design is on how an individual can construct and co-construct their identity and life through their work within the context that forms part of the society in which they live (Maree, Citation2020b; Savickas et al., Citation2009; Symington, Citation2015). Life-design interventions examine how an individual has constructed a career through small stories, then deconstructs and reconstructs these stories into an identity narrative and finally co-constructs intentions that lead to action in the real world (Savickas, Citation2013b). The core elements of life-designing are reflexive consciousness, self-making, the client’s capacity to tell their life story (narratability), and adaptability and intentionality (Hartung, Citation2013). Thus, CCT and Life design counselling focus on making a self, shaping an identity, constructing a career, and designing a life (Savickas, Citation2013b, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, september).

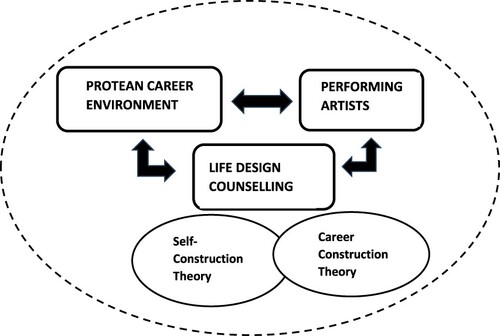

Conceptual framework

The study was based on three primary considerations: the protean career environment, performing artists, and life-design counselling, as indicated in . The protean career environment (the first construct) acknowledges the ever-changing and fluid work environment in which individuals independently drive their careers. Most of the time, performing artists (the second construct) must function, cope, and thrive in such a protean environment. Core to this process is performing artists’ self-construction and career construction. The three core pillars of career construction theory are identity (the what), adaptability (the how) and life themes (the why). The life-design theory forms the basis of the intervention technique by implementing the Career Interest Profile (CIP, version 6) (Maree, Citation2017b) and the career construction interview (CCI) (Maree, Citation2017a; Savickas, Citation2019a). Thus, the intervention assists in the construction, deconstruction, reconstruction, and co-construction of performing artists based on the self and CCT. There is a reciprocal interaction between the constructs as they influence each other within an ever-changing and fluid environment (the more extensive system) that impacts the smaller system, namely the individual.

Aims of the study (include research questions)

The research aimed to identify the life-career experiences influencing the career trajectory of performing artists as a protean career type within the framework of career construction. The aim of the study gives rise to the following research question: What life-career experiences influence the career trajectory of performing artists, including musicians, singers and actors in their early, middle and late life-career stages in South Africa?

Method

Study design

The researcher applied a qualitative research design to promote understanding of the unspoken challenges that individuals, the performing artists, had to confront and resolve, thereby answering not only the “what” but “how” (Teti et al., Citation2020). The study also employed an exploratory, descriptive research design (a multiple case study design) to obtain data from performing artists (Yin, Citation2003). Furthermore, an INDUCTIVE-deductive approach was followed, which yielded thick descriptions from an insider perspective within the specific context (Tracy, Citation2020). Lastly, the study followed an ontological paradigm of constructivism-interpretivism and employed a constructivist-interpretivist paradigm (Ponterotto, Citation2005) as facts only became relevant through their meanings and interpretations by the performing artists themselves (Flick, Citation2004).

Participants

Purposive sampling and, more specifically, criterion sampling was used to select 19 participants who conformed to the inclusion criteria based on the definition of performing artists. Participants identified themselves as performing artists and considered the pursuit and practice of their art to be of significant value and primary life activity. Even though most participants considered themselves active in their chosen artistic field, the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting consequences, such as not being allowed to perform on stage for more than a year, put pressure on them to engage in other income-seeking activities. Refer to for an outline of participants’ qualifications, performing arts category and income-generating activities.

Table 1. Participants’ qualifications, performing arts category and income-generating activities

Instruments/materials and procedures/interventions

Data was generated from various sources, with the first source being the computer-generated report after candidates completed the Career Interest Profile (CIP, version 6) (Maree, Citation2017b) on the JvR assessment portal. The Career Interest Profile (CIP, version 6) is a qualitative assessment instrument rooted in career construction and life-design theory, designed to generate qualitative data (Maree, Citation2017b, Citation2020a, Citation2022). The CIP questions are formulated to explore aspects related to differential, developmental, and psychodynamic (narrative) traditions. They are structured to foster reflection, reflexivity, and the processes of narratability and biographicity (Maree, Citation2020a). Extensive research has investigated the CIP’s credibility, validity, and trustworthiness (Maree, Citation2017b). The CIP comprises four sections (Maree, Citation2022). Part 1 requires participants to provide biographical details and information on family influences. Part 2 involves participants responding to questions about career choices. Part 3 entails participants answering questions regarding their preferences and dislikes in career categories, while Part 4 involves responding to micro-life story inquiries (Maree, Citation2022). The second source refers to the career construction interviews (CCI) (Maree, Citation2017a; Savickas, Citation2019a), which were recorded and transcribed. The CCI serves as an assessment technique and intervention to aid individuals in gaining deeper self-awareness and uncovering their subjective life-career themes (Hartung, Citation2011). It challenges individuals to share stories that illuminate both their current identity and their aspirations for the future (Maree, Citation2017a). In addition to its initial query (“How can I be useful to you?”), the CCI also includes a pivotal question: “What are your three earliest recollections?” (Maree, Citation2020b; Savickas, Citation2019b, september). Developed by Savickas (Citation2019b, september), the CCI serves dual roles as both a data-generation method and a strategy for career counseling. The third source refers to the CCI worksheet, which included the interview content summarised by the first author into a worksheet sent to participants for comments. Their feedback was integrated into the worksheet to obtain a summarised version of each candidate’s career construction (Maree, Citation2020a; career construction interview downloaded http://www.vocopher.com/). The fourth source refers to the process notes that include notes as the first author proceeded through the process with each candidate, along with actions and reflections. The fifth source refers to general communication via e-mails or WhatsApp messages from candidates. The sixth source includes participants’ information appearing in the public domain, for example, on social media platforms. The last source refers to the first author’s reflections throughout the research project. All of the above-mentioned sources are qualitative data with a minimal amount of “quantitative data” generated, consisting of the demographic and quantitative data generated in certain parts of the CIP.

Analysis

As qualitative analysis must be systematic and rigorous (Neale, Citation2016), all approaches and methods employed in the current study aimed to promote this goal. The data analysis method used was thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2013), which emphasises an organic approach to coding and theme development and the active role of the researcher in these processes, thus allowing researchers to identify and make sense of the collective or shared meanings and experiences.

Then, the first author employed a three-digit coding system, where the first number referred to a particular participant and the second number referred to specific sources from which the researcher obtained the information. It is important to note that no page numbers are generated when importing documents into ATLAS.ti (Friese, Citation2019), which also assisted in structuring and organising the data, but rather paragraph numbers. Therefore, the third number refers to the paragraph number in the source. The only exception is when referring to the CIP, a PDF-generated report, where the researcher referred to page numbers. Furthermore, each participant was assigned a colour to aid the reader in following responses from participants throughout the identified themes. Participants’ “verbatim” responses can thus be found following the coding system, as outlined in .

Table 2. Outline of the coding system.

Lastly, categories were based on various theoretical frameworks, such as Super et al.’s (Citation1996) developmental theory, the systems theory framework of Patton and McMahon (Citation2015), the core pillars of the CCT (Savickas, Citation2013a), and strategies participants reported employing for navigating through a protean career.

Findings and discussions

provides the main, sub-themes, sub-sub-themes and sub-sub-sub-themes that emerged.

Table 3. Depicting the main, sub-themes, sub-sub-themes and sub-sub-sub themes.

Theme: the idiosyncratic journey towards constructing a career choice

The first theme made the impact of external and internal influences on participants’ career choices evident.

External influences: External factors influence the nature and significance of work in any individual’s lifespan. They can be described as significant others, including parents, families or the community, that participants view as key figures they look up to for guidance and advice and whose opinion significantly influences the career choice of the participant (Coetzee et al., Citation2016). Many candidates (12) referred to the positive feedback, support and encouragement they received from their parents and family members to follow their dreams, whatever they may be. Central to the instrumental support participants received is the emotional and physical support received, such as funding participants while pursuing a performing arts career and assisting them with tasks while pursuing their performing art studies, even if it was to their own detriment, such as having to support the household on a small salary while allowing spouses to follow their calling. Negative feedback from significant others focused on the performing arts as an unstable career choice with no structure or security and, therefore, not a “real” job, i.e. a traditional job. The following quote refers to positive (supportive feedback) from a father:

(#13;B;21&204-207): “Those years, my father also still sang. I fell asleep at the back of stages. Interestingly, he never wanted to see me in this world, but he unwittingly woke me up to this world. I’ve inherited all that stuff through him.”

(#18;B;152&156): “So she coached the junior choir and spotted something in me already in grade one. I always walked away to her class. Then I practised on her piano. She sponsored me for singing, and she trained me until matric.”

“The first time I heard a live symphony orchestra and my first production. I remember the exhilaration that I felt with both events.”

(#9;B;24;28): “My mom tells me I sang before I spoke. So, before I had my first word, I sang. So that’s always been who I am. It is not something I chose. I think it chose me.”

The third internal influence that emerged was interest, referring to participants giving their attention, preferring or liking one activity rather than another and moving towards the object of their interest (Strong, 1955; in Maree, Citation2017b). Whereas most participants’ career choices confirmed their interest in the Arts and Social fields, participants indicated an apparent aversion towards a career choice in the Realistic and Conventional fields.

Theme: the career development trajectory

From the second theme, two sub-themes emerged. The first sub-theme referred to aspects impacting perceived personal and career success or failure. The subthemes include elements that participants value within their personal and career development trajectories perceived as positively or negatively impacting them and their perceived success or failure. Aspects include education, craft competency and the business of performing arts. Education is the first sub-sub-sub-theme referring to perceived success or failure within education, significantly impacting individuals’ goals and aspirations (Maree, Citation2020b). For many participants, obtaining a qualification made them feel good about themselves and their achievements. It was viewed as an essential criterion for their success. However, some participants who did not receive qualifications perceived themselves as “failing” in this area – evidenced by the following two quotes.

(#12;B;37&51): “You see, studies help you to be focused. Even in our field, you study first. You can’t break the rules that you don’t know. That’s what drama school and places like that are there for. For you to make mistakes in a comfort zone and to find your signature within that theory. Find yourself in what you’re doing and then go and teach … that’s non-negotiable for me.”

(#14;B;227): “I don’t know why I’m seeing it as a failure. I think it’s the pressure of people that are surrounding me, you know, that have qualifications. I don’t have a single qualification, and sometimes it just makes me feel bad about myself.”

The business of performing arts was the third sub-sub-sub theme referring to entrepreneurial acumen, such as obtaining resources and managing the performing arts as a business –, albeit a one-person business or an entrepreneur engaging continuously in new business ventures. Most participants indicated an aversion towards the business of performing arts, evidenced by the following quote (#11;B;133): “I hate money. I don’t like to talk about it. I don’t like working with money. It’s an evil for me.”

Only one participant stated an inclination towards the business of performing arts and listed various business endeavours she engaged in, some of them portrayed in the following quote:

(#1;A;12&17): “Owning two of my own festivals; Marketing Manager ensuring the success of brands in the creative sector; Programme Director Development of youth and contributing to building an industry and careers for young creatives; Working on programmes that are structured for success for creatives and developing audiences; Artist Manager ensuring that creatives are represented fairly and professionally.”

Career control refers to the individual’s ability to control career choices versus indecision (Savickas, Citation2010). It thus answers the question, “Who owns my future?” explicitly focusing on enhanced self-responsibility, being driven, preparation and perseverance emerging as sub-sub-sub themes. Enhanced self-responsibility is evident in the following quote (#8;B;446-449): “Making things happen for myself has been incredibly empowering.” Drivenness is evident in the following quote (#10;B;269): “We are now driven more than ever because we realised the power we possess.”

The following sub-sub-sub-theme of career control is the importance of preparation, echoed by many participants (#12;B;115):

“When I go and audition, I prepare. When I go on set, I prepare. When I direct, I am careful about my skills and the language I use. It matters all the time. You must prepare-professionalism in every sphere.”

Career Curiosity refers to curiosity towards various interests and alternatives (Savickas, Citation2013b). It answers the question, “What do I want to do with my future?” explicitly focusing on their diverse skill set, creating their own opportunities and a continuous re-invention of self as the three sub-sub-sub-themes. Firstly, the importance of employing a diverse skill as part of participants’ career survival skill set is evident in the following quote (#19;B;89&194): “You have to use all your skills; it’s effort. I basically have three careers: art, visual arts and music.” Another sub-sub-sub-theme that emerged focused on participants creating their own opportunities, evident in the following quote (#1;B;9):

“I’ve created a lot of my own opportunities by volunteering a lot of my time … to demonstrate the value of having somebody like me as part of your projects. To create a position for myself.”

The last sub-sub-theme emerging as part of participants’ career survival skill set was career confidence, reflecting the expectation of career success. It relates to feelings of self-efficacy concerning individuals’ ability to successfully execute a course of action needed to make and implement suitable career choices (Savickas, Citation2005). It answers the question, “Can I do it?” and includes positive self-view, self-confidence, independence, and increased risk-taking behaviour. The following quote indicates the importance many candidates attach to a positive self-view and self-confidence (#1;B;9): “I’ve created a lot of my own opportunities … to demonstrate the value of having somebody like me as part of your various projects.” Relating to career confidence was the participants’ view of the importance of being independent (#18;B;196):

“I want to do it my way. I don’t want a manager telling me exactly what I must sing, how I should dress, who I must mix with.”

Recommendations

Methods

Longitudinal research is needed to establish performing artists’ long-term self – and career construction throughout the life-career stages. For example, Mansour et al. (Citation2018) studied young people’s creative and performing arts participation and self-concept within the arts, focusing on the reciprocal effect of these constructs on each other over time. Furthermore, trans-institutional, transnational, national, international, transdisciplinary, and interdisciplinary research should be conducted on the career construction of performing artists. Even though Biggs and Karlsson’s (Citation2010) work is already more than ten years old, it can still serve as an example of expert researchers trying to find common ground for research in the arts while researchers collaborate across countries. However, more such collaborations are necessary continuously.

Training institutions

Bridgstock (Citation2013) highlights the need for higher education institutions to develop field-specific entrepreneurial capabilities among performing artists and their entrepreneurial identities. However, the literature misses the natural aversion of performing artists toward entrepreneurial activities. Therefore, research should be conducted on how the initial buy-in and motivation from performing artists can be obtained and how this motivation can be maintained to enhance the efficiency of such programmes or modules and enhance the entrepreneurial career trajectory of performing artists. The study of Schediwy et al. (Citation2018) is one of the first attempts to investigate students’ perceived need for entrepreneurship education and what such needs entail.

Career counsellors

First, it is evident that performing artists are significantly influenced by both internal and external factors when making career decisions. Moreover, they navigate a distinct career trajectory fraught with its own array of challenges within an unpredictable and constantly evolving environment. Consequently, career counsellors must initially recognise the supplementary factors and hurdles performing artists face in their career trajectories. Second, they should mitigate any negative perceptions their clients may hold regarding their careers. Third, they should actively facilitate the development of life skills, emphasising what are commonly referred to as the four C’s, in collaboration with their clients.

Limitations

No study is without limitations, and the present study is no exception. First, non-probability sampling with elements of convenience and purposive sampling was utilised. Furthermore, the sample consisted of 19 participants only. Even though the findings cannot be generalised to the entire population of performing artists, many findings were supported by literature, prompting the formulation of significant new research inquiries. Furthermore, the study was conducted during the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic substantially influenced performing artists’ lives and careers. Thus, even though the full impact of COVID-19 on the research outcomes remains unclear, performing artists continuously have to navigate their careers through perilous circumstances, and the pandemic was no different.

Second: The study only focused on specific performing arts categories, such as musicians, singers, and actors. The findings may have differed if other performing arts categories, such as dancers, were included in the study.

Third: Before starting the study, the first author was acquainted with some participants due to her involvement in the performing arts. Her bias towards performing artists and their unique challenges may have influenced the findings. However, she took every reasonable step to guard against the halo effect by avoiding making biased judgements as far as possible.

Lastly, the first author is aware of the subjective character of the chosen data sources. Therefore, quality control criteria were established to ensure confirmability, credibility, dependability, transferability, and trustworthiness. For example, the lead researcher employed software to systematically generate, organise, and analyse the data, bolstering its credibility. Information from diverse sources was collated over several months, and data triangulation was conducted. Moreover, study participation was voluntary, with member checks carried out to enable participants to review interview transcripts and worksheets, ensuring the accuracy of their input. Reflexivity and crystallisation were facilitated through the creation of detailed, descriptive data and prolonged engagement with it. The lead researcher also engaged in continuous self-awareness practices to augment self-reflection and reflexivity. An external coder verified themes and sub-themes to ensure the credibility and reliability of the recorded data and themes. Additionally, the lead researcher provided ample contextual details about the participants to enhance the transferability of the findings. Lastly, the lead researcher presented a thorough description of the research study process to ensure dependability. Despite employing these rigorous methods, the lead researcher acknowledges that the subjectivity of the analysis and interpretations needs to be considered a limitation, as another researcher could have interpreted the findings and resulting themes differently.

Conclusion

This article provides insights into the life-career experiences that shape the career trajectories of performing artists. It examines the distinct journey these artists embark on when navigating career decisions, taking into account a blend of external and internal influences. Furthermore, it presents a novel perspective on the career development trajectory within the performing arts field, examining factors that impact perceived success or “failure.” Importantly, it illuminates the indispensable skill set necessary for “survival” (and thriving) in the competitive landscape of the performing arts industry. Lastly, the article proposes practical recommendations for methodologies, training institutions, and career counselors.

Informed consent and ethical statement

The research was approved by The Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of the Free State (Ethical clearance number: UFS-HSD2018/1182). The first author obtained informed consent from participants and explained the participants’ right to withdraw from the project at any time should they wish to do so. Participants were ensured of the confidentiality of their information and the right to privacy as the researcher used pseudonyms and adjusted identifying data.

The researcher facilitated anonymity and confidentiality by ensuring that no individual’s identity could be traced based on the data and maintained this practice in communicating the results. Transcribed interviews and results were communicated to the participants for verification purposes and to ensure the absence of misinterpretations throughout the research process. Finally, the trustworthiness of the study was established by giving attention to the credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the research findings (Golafshani, Citation2003; Guba & Lincoln, Citation1989; Johnson et al., Citation2020), thereby enhancing the rigour of the research process.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the individuals who participated in this research.

Conflict of interest statement

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ronel Kleynhans

Ronel Kleynhans is a registered career practitioner and psychometrist in the Department of Industrial Psychology at the University of the Free State, South Africa. Her research interests include career (constructive) counseling, integrative career counselling, life-design counselling and employee well-being.

Petrus Nel

Petrus Nel is a registered industrial psychologist with an interest in employee well-being. He is affiliated with the Department of Industrial Psychology at the University of the Free State, South Africa.

Kobus Maree

Kobus Maree is a Professor and educational psychologist in the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. His research interests include career (construction) counseling, integrative career counselling, and life-design counselling.

References

- Allen, P. (2022). Artist management for the music business: Manage your career in music: Manage the music careers of others. Focal Press.

- Biggs, M. A. & Karlsson, H. (Eds.) (2010). The Routledge companion to research in the arts. Routledge.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Bridgstock, R. (2005). Australian artists, starving and well-nourished: What can we learn from the prototypical protean career? Australian Journal of Career Development, 14(3), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841620501400307

- Bridgstock, R. S. (2011). Making it creatively: Building sustainable careers in the arts and creative industries. Australian Career Practitioner Magazine, 22(2), 11–13.

- Bridgstock, R. (2013). Not a dirty word: Arts entrepreneurship and higher education. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 12(2-3), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022212465725

- Brooks, G. S., & Daniluk, J. C. (1998). Creative labors: The lives and careers of women artists. The Career Development Quarterly, 46(3), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1998.tb00699.x

- Butler, P. (2000). By popular demand: Marketing the arts. Journal of Marketing Management, 16(4), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725700784772871

- Carey, C. (2015). The careers of fine artists and the embedded creative. Journal of Education and Work, 28(4), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2014.997686

- Coetzee, M., Roythorne-Jacobs, H., & Mensele, C. (2016). Career counselling and guidance in the workplace: A manual for career development practitioners (3rd ed.). Juta.

- Daniel, R. (2016). Creative artists, career patterns and career theory: Insights from the Australian context. Australian Journal of Career Development, 25(3), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416216670663

- Daniel, R., & Daniel, L. (2013). Enhancing the transition from study to work: Reflections on the value and impact of internships in the creative and performing arts. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 12(2-3), 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022212473525

- Del Corso, J., & Rehfuss, M. C. (2011). The role of narrative in career construction theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.04.003

- Everts, R., Hitters, E., & Berkers, P. (2022). The working life of musicians: Mapping the work activities and values of early-career pop musicians in the Dutch music industry. Creative Industries Journal, 15(1), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2021.1899499

- Flick, U. (2004). Constructivism. In U. Flick, E. von Kardorff, & I. Steinke (Eds.), A companion to qualitative research (pp. 88–94). Sage.

- Friese, S. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS. Ti (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Golafshani, N. (2003). Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 8, 597–606. http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol8/iss4/6.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Sage.

- Hall, D. T. (1996). Protean careers of the 21st century. Academy of Management Perspectives, 10(4), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1996.3145315

- Hall, D. T. (2013). Protean careers in the 21st century. In K. Inkson & M. L. Savickas (Eds.), Career studies: Vol 1. Foundations of career studies (pp. 245–254). Sage.

- Hall, D. T., & Mirvis, P. H. (1996). The new protean career: Psychological success and the path with a heart. In D. T. Hall, & Associates (Eds.), The career is dead — long live the career. A relational approach to careers (pp. 15–45). Jossey-Bass.

- Hartung, P. J. (2011). Barrier or benefit? Emotion in life-career design. Journal of Career Assessment, 19(3), 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072710395536

- Hartung, P. J. (2013). Chapter 4: The life-span, life-space theory of careers. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 83–114). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Hartung, P. J., & Cadaret, M. C. (2017). Career adaptability: Changing self and situation for satisfaction and success. In K. Maree (Ed.), The psychology of career adaptability, career resilience, and employability (pp. 15–28). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0_2

- Hume, M., Mort, G. S., & Winzar, H. (2007). Exploring repurchase intention in a performing arts context: Who comes? And why do they come back? International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 12(2), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.284

- Inglis, L., & Cray, D. (2012). Career paths for managers in the arts. Australian Journal of Career Development, 21(3), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841621202100304

- Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 7120. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7120

- Johnston, C. S. (2018). A systematic review of the career adaptability literature and future outlook. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072716679921

- Kerr, B., & McKay, R. (2013). Searching for tomorrow’s innovators: Profiling creative adolescents. Creativity Research Journal, 25(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2013.752180

- Kogan, N. (2002). Careers in the performing arts: A psychological perspective. Creativity Research Journal, 14(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1401_1

- Lent, R. W. (2012). Work and relationship: Is vocational psychology on the eve of construction? The Counseling Psychologist, 40(2), 268–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000011422824

- Mansour, M., Martin, A. J., Anderson, M., Gibson, R., Liem, G. A., & Sudmalis, D. (2018). Young people’s creative and performing arts participation and arts self-concept: A longitudinal study of reciprocal effects. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 52(3), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.146

- Maree, J. G. (2015a). Career construction counseling: A thematic analysis of outcomes for four clients. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.10.001

- Maree, J. G. (2015b). Life themes and narratives. In P. J. Hartung, M. L. Savickas, & W. B. Walsh (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of career intervention, Vol. 2. Applications (pp. 225–239). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14439-017

- Maree, J. G. (2017a). Opinion piece: Using career counselling to address work-related challenges by promoting career resilience, career adaptability, and employability. South African Journal of Education, 37, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n4opinionpiece

- Maree, J. G. (2017b). Career interest profile – version 6 (CIP v6). JvR Psychometrics.

- Maree, J. G. (2018). Advancing career counselling research and practice using a novel quantitative + qualitative approach to elicit clients’ advice from within. South African Journal of Higher Education, 32(4), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.20853/32-4-2558

- Maree, J. G. (2020a). Innovating counseling for self-and career construction. Connecting conscious knowledge with subconscious insight. Springer.

- Maree, J. G. (2020b). The need for contextually appropriate career counselling assessment: Using narrative approaches in career counselling assessment in African contexts. African Journal of Psychological Assessment, 2, a18. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajopa.v2i0.18

- Maree, J. G. (2022). Using integrative career construction counselling to promote autobiographicity and transform tension into intention and action. Education Sciences, 12(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020072

- Middleton, J. C., & Middleton, J. A. (2017). Review of literature on the career transitions of performing artists pursuing career development. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 17(2), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-016-9326-x

- Neale, J. (2016). Iterative categorization (IC): A systematic technique for analysing qualitative data. Addiction, 111(6), 1096–1106. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13314

- Patton, W., & McMahon, M. (1999). Career development and systems theory: A new relationship. Brooks/Cole.

- Patton, W., & McMahon, M. (2006). The systems theory framework of career development and counseling: Connecting theory and practice. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 28(2), 153–166. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/archive/00002621/01/2621.pdf

- Patton, W., & McMahon, M. (2015). The Systems Theory Framework of career development: 20 years of contribution to theory and practice. Australian Journal of Career Development, 24(3), 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416215579944

- Patton, W., McMahon, M., & Watson, M. B. (2017). Career development and systems theory: Enhancing our understanding of career. In G. B. Stead & M. B. Watson (Eds.), Career psychology in the South African context (3rd ed.). Van Schaik.

- Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.126

- Preece, S. B. (2011). Performing arts entrepreneurship: Toward a research agenda. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 41(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2011.573445

- Pryor, R., & Bright, J. (2011). The chaos theory of careers. Routledge.

- Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 42–70). Wiley.

- Savickas, M. L. (2008). Helping people choose jobs: A history of the guidance profession. In J. A. Athanasou & R. Van Esbroeck (Eds.), International handbook of career guidance (pp. 97–113). Springer Science & Media.

- Savickas, M. L. (2010). Vocational counselling. In I. B. Weiner & W. E. Craighead (Eds.), Corsini’s encyclopedia of psychology (4th ed., pp. 1841–1844). Wiley.

- Savickas, M. L. (2011a). Career counseling. American Psychological Association.

- Savickas, M. L. (2011b). New questions for vocational psychology: Premises, paradigms, and practices. Journal of Career Assessment, 19(3), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072710395532

- Savickas, M. L. (2013a). Career construction theory and practice. In R. W. Lent & S. D. Brown (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 147–183). John Wiley & Sons.

- Savickas, M. L. (2013b). The 2012 Leona Tyler Award Address: Constructing careers: Actors, agents, and authors. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(4), 648–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012468339

- Savickas, M. L. (2019a). The world of work and career interventions. In M. L. Savickas (Ed.), Theories of psychotherapy series. Career counseling (pp. 3–14). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000105-001

- Savickas, M. L. (2019b, September). Designing a self and constructing a career in post-traditional societies. In Keynote address at the 43rd International Association for Educational and Vocational guidance Conference, Bratislava, Slovakia, 11-13 September 2019.

- Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J.-P., Duarte, M. E., Guichard, J., Salvatore, S., Van Esbroeck, R., & Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2009). Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.04.004

- Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

- Schediwy, L., Loots, E., & Bhansing, P. (2018). With their feet on the ground: A quantitative study of music students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship education. Journal of Education and Work, 31(7-8), 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2018.1562160

- Super, D. E. (1957). The psychology of careers: An introduction to vocational development. New York: Harper & Bros.

- Super, D. E., Savickas, M. L., & Super, C. M. (1996). The life-span, life-space approach to careers. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development (3rd ed., pp. 121–178). Jossey-Bass.

- Swanson, J. L. (2013). Traditional and emerging career development theory and the psychology of working. In D. L. Blustein (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the psychology of working (pp. 49–67). Oxford University Press.

- Symington, C. (2015). The effect of life-design counselling on the career adaptability of learners in an independent school setting [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Pretoria. http://hdl.handle.net/2263/44251

- Teti, M., Schatz, E., & Liebenberg, L. (2020). Methods in the time of COVID-19: The vital role of qualitative inquiries. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920920962

- Thomson, K. (2013). Roles, revenue, and responsibilities: The changing nature of being a working musician. Work and Occupations, 40(4), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888413504208

- Tracy, S. J. (2020). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

- Wacholtz, L., & Wilgus, J. (2011). The whoop curve: Predicting entrepreneurial and financial opportunities in the performing arts. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 17(1), 23–36.

- Wyszomirski, M., & Chang, W. (2017). Professional self-structuration in the arts: Sustaining creative careers in the 21st century. Sustainability, 9(6), 1035. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/9/6/1035.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Zwaan, K., & Ter Bogt, T. F. (2009). Research note: Breaking into the popular record industry. European Journal of Communication, 24(1), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323108098948