ABSTRACT

A move to online therapy, observed in counselling courses within the UK during the global Covid-19 pandemic, prompted a research team of counselling educators to undertake a rapid literature review to explore the perceptions and experiences of video therapy internationally (PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020204705). Four databases (CINAHL, Medline, PsychInfo, and Web of Science) were searched using 25 keyword-phrases. Over half the research identified focused on using computers for therapy. Insufficient papers explored the client experience for inclusion. However, eleven practitioner papers of reasonable to strong quality were identified and are reported in this paper, with only one from the UK. Thematic analysis identified four internationally applicable themes for practitioners: therapeutic practice; technical concerns; perceptions of client benefits and challenges when working online; and therapist challenges. The paper identifies several areas of potential future research from the identified themes which could inform future practice, including the need for further client-based research.

Sustainable Development Goals:

Introduction

The practice of working via telephone and digital and online platforms has spread rapidly through health and mental health professions. Within the context of clinical and counselling psychology, as well as psychiatry, there has been increasing recognition of the value of online/remote delivery of services, not least from the perspective of inclusivity. A landmark systemic review (Barak et al., Citation2008) considered the overall effectiveness of internet-based interventions and demonstrated the efficacy of online CBT therapy, highlighting how practitioner and client preferences might influence perceptions and experiences of technological practice platforms. They signposted the value of, and need for, further investigation into interventions delivered through complex and varied digital platforms. More recently, a study considered how research can help us to identify differences between telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy, finding evidence of practitioner perceptions and beliefs about counselling media without a visual element as being inferior (Irvine et al., Citation2020).

Whilst digitised CBT-based therapies have been used for a number of years for a range of health and mental health issues (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Citation2009), counselling and psychotherapy practitioners have been slower to recognise the potential for in-person video and telephone services. Before 2020, almost all counselling training courses in the UK offered training for face-to-face therapy only, as these were the only clinical hours accepted by the main accrediting body, British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), for counsellor qualification. The cessation of face-to-face therapy due to the sudden imposition of a societal lockdown during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic influenced a move to online delivery (Békés and Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2020). This situation accelerated counselling and psychotherapy’s rapid technological transition to remote working and facilitated the growth of synchronous (i.e. real-time) digitally delivered therapy (Békés et al., Citation2020; Calkins, Citation2021).

The profession, where possible, adopted online delivery of therapy, but without a complete understanding of the nature of this modality, given their previous focus on face-to-face in-person client work (Smith et al., Citation2022). Professional and training organisations recognised the challenges of moving to visual online practice and the need to upskill practitioners for online work (Brown, Citation2020). They provided member and practitioner guidance and support through, for example, free training resources. UK professional bodies (BACP and UKCP) also surveyed their members to identify practitioner perspectives and experiences of online practice during Covid-19, recognising the opportunity to learn from practitioners’ new online experiences (Full et al., Citation2024).

These activities highlighted the need for empirical support and learning in this area of practice. One area of influence in the adoption and engagement of online therapy was predicted to be the attitude and assumptions made by practitioners and clients (Barak et al., Citation2008). In addition, there remained a question of what the experience of online therapy was like. The research team, who had experience of telephone and face to face counselling but not video counselling, sought to explore the existing literature on client and counsellor experiences and perceptions of counselling via synchronous, person-to-person online video counselling, to develop their understanding in this area. This review aimed to extend our understanding of the available literature and the nuanced experiences and value placed by practitioners and clients specifically on working through synchronous online (video) delivery modes. Synchronous online video delivery is defined here as: synchronous, client-therapist interactions through video platforms which are structured in the same way as in-room counselling and psychotherapy (Smith et al., Citation2022).

The key question informing this review was:

What are client and counsellor experiences and perceptions of online (video) synchronous person-to-person counselling?

In this review, the word counsellor, psychotherapist and therapist are used interchangeably and may include counsellors, psychotherapists, clinical/counselling psychologists or other mental health professionals who have a core training in delivering counselling or psychotherapy.

Methodology

Review structure

A rapid review framework (Tricco et al., Citation2015) rather than a systematic review was chosen, given the perceived urgency of the need for information from the team during the pandemic, in conjunction with the multiple additional calls on team members resources which precluded a more intricate design. The Prospero registration provided an outline of the approach utilised for the review (PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020204705).

Selection criteria

As previously identified in Smith et al. (Citation2022), identifying keywords for this specific area of research proved complex due to a multiplicity of naming conventions used at times inconsistently. Instead, the team used a different approach by identifying key words which would be widely recognised and commonly used in association with online counselling, specifically live synchronous video, and were likely to appear in study titles.

Papers published from 2010 onwards only were included, to allow for technological developments in online devices and platforms necessary for online synchronous video-counselling such as the introduction of Zoom© in 2013, and Microsoft Teams© in 2017. Those published worldwide and peer-reviewed were considered, although the translation of non-English language texts was considered beyond the scope of this study. The search was restricted to adult psychotherapy and any client groups under the age of 18 were excluded.

Search strategy

A search of four databases (CINAHL, Medline, PsychInfo, and Web of Science) plus Google Scholar was undertaken between August 2020 and November 2020 to identify primary research papers which focused on the delivery of counselling and psychotherapy via synchronous online video platforms only.

An initial search of 51 potential keywords was identified by the research team. The number of publications identified for each keyword was logged through a preliminary search and showed that there were 25 keywords which were used most frequently in the literature. To focus the search and manage search result numbers, this shortlist of 25 keyword phrases (see below) was agreed collectively by the authors as appropriate for the literature search. These keywords were then used to search the literature using title field only.

Table 1. Search terms used within the Literature Review.

Selection process

Initially, two reviewers (JH and RS) undertook a search of titles and abstracts to discard research that did not meet the initial selection criteria. The reviewers at this stage erred on the side of inclusion in cases of uncertainty to ensure that potentially relevant papers were not excluded. The shortlisted papers from each database were then combined, and duplicates removed.

These shortlisted papers were then divided between the two reviewers and sorted into four categories as follows:

Category 1: synchronous, person-to-person therapy delivered by counsellors or psychotherapists;

Category 2: computer/software delivered therapy;

Category 3: support delivered by paraprofessional helpers (e.g. support workers/frontline workers such as nurses or social workers who have counselling skills but not full counsellor or psychotherapist training);

Category 4: letters, opinion papers, papers on protocols, minutes.

Any papers identified during this stage as not applicable to any of these four categories or the initial search criteria were removed. Papers where the categorisation was unclear from the title and abstract were placed in category 1. As over 50% (N = 570) of the identified papers were Category Two i.e. related to computer or software delivered therapy, these were rechecked by reviewers (LG, NM, JR, RS, KS) but none of the papers met category 1 criteria. In total, 177 papers were categorised as Category One.

A review of the abstracts of Category One papers was then undertaken by two reviewers (NM and JR). Both reviewers considered all 177 papers separately, categorising them according to the focus of the research, and then met to agree the final categorisations. This resulted in the exclusion of papers in the following categories:

not primary research

compared online and face-to-face working

not wholly 1–1 video-therapy experiences; for example, substantive email or text-based therapy included or group or couples therapy

related to issues outside the specific counselling process such as engagement, help-seeking

related to a very specific (and narrow) client group, such as those with eating disorders

involved the attitudes of non-professional groups

related to the effectiveness of online working

could not be accessed via the University database systems

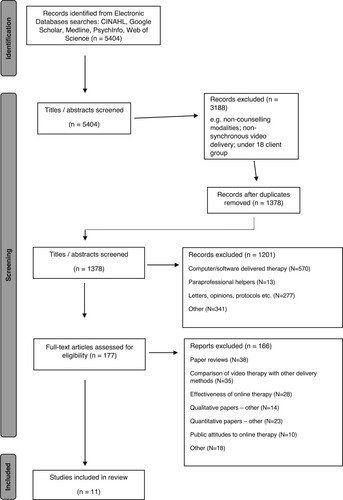

The remaining papers provided a focus on practitioner experiences and perceptions. A PRISMA chart, which visually summarises this screening process and the decisions made, is given in .

A quality review of the selected papers was completed using CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018) (NM and JR), which is a tool for appraising the strengths and limitations of any qualitative research methodology, and the Cochrane framework (Higgins et al., Citation2022) (DC and ED), which provides guidance for assessing the quality, breadth, and depth of systematic reviews (Higgins et al., Citation2022). Each academic team included a highly experienced researcher and an early career researcher to complete the assessment. Finally a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2021) of the papers included within this literature search was completed to determine the themes emerging from the literature.

Findings

The initial database searches were sorted into categories as shown in , providing insight into the focus of research in this area. Contemporary published literature appeared to be dominated by papers on computer/software delivered therapy (n = 570, 55%) and providing opinions and suggesting protocols for online delivery (n = 277, 27%). Hence, the main research focus to date has been on how to use computers to deliver therapy, rather than to facilitate in-person therapy and to discuss and propose, rather than conduct, primary research. Paraprofessional delivery (n = 13, 1%) appears very small, but this could be due to such research using different keyword phrases more appropriate to that specific profession.

The research associated with synchronous person-to-person online therapy was only 17% (n = 177) of the screened publications, suggesting immediately that the amount of research in this area at the point of review was limited. Further analysis of these papers provided more information on the type of research being undertaken in this area, as shown in .

The main focus of synchronous person-to-person online therapy research was the comparison of online working with face-to-face in-the-room working, to explore whether clients can experience comparable outcomes (n = 35, 20%) and to measure the effectiveness of online work (n = 28, 16%). Establishing online therapy as a realistic option for clients, when much is still unknown, is an important foundational position for future research. The other significant category identified was for literature reviews and opinion pieces (n = 38, 21%). Whilst it could be argued that these should have been classified as category 4 prior to this analysis, the first categorisation was to pull together all papers that appeared to match category 1 criteria, erring on the side of caution when allocating categories. Interestingly, many of these reviews were completed to support the case for trying video therapy i.e. the effectiveness, rather than exploring the experience, in line with other research.

One of the key and surprising findings from this study was the relative lack of client research (n = 3, 2%) on the perspective or experience of video-counselling. However, the larger cluster of research on counsellor perspectives of synchronous person-to-person online working (n = 20, 11%), is arguably a more ethical place to start, as this allows the establishment of research methods and areas of research interest prior to recruiting client participants for further studies.

The review of the full text of the 20 identified papers involving counsellor experiences or perceptions identified nine papers for exclusion. For example, papers with abstracts in English could be written in another language, whilst others included face-to-face in-person therapy or therapist independent computer activity as part of the process. The remaining 11 papers, including 5 qualitative, 5 quantitative and 1 mixed-methods papers on counsellor expectations and experiences of synchronous person-to-person online therapy are shown in Appendix 1. Six of these papers were authored in the USA, four in Europe and one in the UK. The papers explored a range of different issues including:

Perceptions of what it might be like to go on line (Drath & Necki, Citation2018; Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019; Hoffman et al., Citation2020; Paterson et al., Citation2019) compared with experiences of online working (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Békés & Aafjes-van Doorn, Citation2020; Békés et al., Citation2020; Cipolletta et al., Citation2018; Feijt et al., Citation2020; Gray et al., Citation2015; Interian et al., Citation2018)

A range of different contexts

from private client work (Cipolletta et al., Citation2018) to agency work (Gray et al., Citation2015);

from trainees (Gray et al., Citation2015; Paterson et al., Citation2019) to mental health professionals (Cipolletta et al., Citation2018; Hoffman et al., Citation2020); and

from an organisational choice to go online (Gray et al., Citation2015; Interian et al., Citation2018) to external events forcing online working (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Feijt et al., Citation2020).

Four papers were written by those exploring online working during the Covid-19 pandemic (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Békés & Aafjes-van Doorn, Citation2020; Békés et al., Citation2020; Feijt et al., Citation2020) with the others completed prior to the pandemic when online working was not as prevalent.

Demographics

Where demographic information was presented, the responding population was reported as predominantly female and white, in line with reported demographics of the counselling and psychotherapy professions (Brown, Citation2017; York, Citation2020). The studies suggested variations in age of respondents, although the majority of studies had an average age of respondent of 35-45, which is slightly younger than the average of counsellors in the UK (Brown, Citation2017). Where modality was identified, this was predominantly CBT, psychodynamic or psychoanalytical. Although humanistic therapy was mentioned in practitioner demographics, the level of response from those practitioners was low and therefore had limited impact on research outcomes.

Review of quality of the quantitative studies

This section provides a narrative review of the five quantitative articles selected with the data presented in Appendix 1 (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Békés & Aafjes-van Doorn, Citation2020; Békés et al., Citation2020; Drath & Necki, Citation2018; Gray et al., Citation2015). All the outcome measure numeric values included in Appendix 1 are raw scores and should be interpreted within the context of their respective ranges and standard deviations. The numeric values included in this analysis are mean (average score), standard deviation (measure of variation within the data set), and range (minimum and maximum score allowed).

The Cochrane framework, which the researchers (DC and ED) were familiar with, was used to examine study quality and risk of bias. Overall, the quantitative studies were of consistently strong quality, with Aafjes-van Doorn et al. (Citation2021) and Békés and Aafjes-van Doorn (Citation2020) being especially well-designed. All studies provided sufficient detail with regards to methods and analysis, with statistics overall being presented clearly. Both Aafjes-van Doorn et al. (Citation2021) and Békés and Aafjes-van Doorn (Citation2020) used standardised scales and models to measure attitudes towards online therapy and therapeutic alliance during online therapy. Notably, Gray et al. (Citation2015) measured both client and therapist satisfaction with online therapy, and utilised established standardised scales to measure outcomes of video therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptoms but had a small sample size which limits the generalizability of their results. In addition, neither Gray et al. (Citation2015) nor Drath and Necki (Citation2018) used established scales or models to measure satisfaction or attitudes which somewhat limits measure validity. While the overall focus is on video counselling, the quantitative papers included are broader in their scope, including video, phone, and other forms of online counselling.

Review of the content of the quantitative studies

In line with thematic analysis, we undertook an across-case approach with the selected quantitative papers (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). Both researchers (DC and ED) identified and coded key quantitative results before meeting to share initial themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). The researchers (DC and ED) then discussed, refined, and agreed thematic names as detailed in Braun and Clarke (Citation2021). The four themes are as follows: (a) What are therapists’ perceptions and beliefs about the efficacy and effectiveness of online therapy? (b) What are the therapists’ attitudes towards online therapy? (c) What is the impact of online work on the therapeutic relationship? (d) What are therapists’ perceptions of future use of online therapy? These questions were drawn from each of the selected papers primary results.

Although therapist attitudes towards online therapy indicated fairly positive views, there were numerous unique challenges highlighted, including therapists reporting less therapeutic connection when conducting online therapy (including video, telephone, and other online methods) (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021). This study was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic, which may have influenced therapist attitudes towards video, as it contrasts with Gray et al. (Citation2015), who found therapists had high rates of satisfaction with delivering therapy online. While generally therapists indicated somewhat positive attitudes towards the usage of video therapy specifically (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Békés & Aafjes-van Doorn, Citation2020), Drath and Necki (Citation2018) found that the majority of therapist participants doubted the general applicability of online therapy unless in exceptional circumstances and Aafjes-van Doorn et al. (Citation2021) found that, in therapists’ perceptions of future use of online therapy, some were undecided on whether to continue using video therapy. In addition, Békés et al. (Citation2020) found that the majority of therapists reported positive or neutral perceptions of client satisfaction with online therapy.

Overall, therapists’ attitudes towards online therapy were highly varied and divided, with both positive and negative aspects of online work being drawn out of the data. Future research on the impact of online work on the experience of delivering therapy is needed particularly in the context of potential models of hybrid work post-pandemic.

Review of the quality of the qualitative research

The five qualitative studies (Cipolletta et al., Citation2018; Feijt et al., Citation2020; Hoffman et al., Citation2020; Interian et al., Citation2018; Paterson et al., Citation2019) and one mixed methods study (Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019) were reviewed independently by two reviewers with 85% agreement on the assessment of the nine elements included in the CASP framework (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018) across the six papers reviewed. Overall, the papers received high marks for quality as they included many of the required items. However, they were assessed as moderately good as they frequently lacked the detail provided in higher quality papers, with many lacking the reflexivity normally included within qualitative work. A summary of the findings is shown in Appendix 2.

In general, the qualitative studies were well presented, with Cipolletta et al. (Citation2018) and Hoffman et al. (Citation2020) being particularly strong. The studies provided clear research questions and a good description of the analytical process. Most of the studies provided a rationale for research decisions and the research process.

Overall, the sample size for the survey-based studies (Feijt = 51; Paterson = 27; Gilmore = 52) was relatively small for such studies. The focus group study (Hoffman et al., Citation2020) also had a small sample size of 11. Larger sample sizes from the qualitative studies would have provided more confidence in the data, but there was enough detail of the methodology to suggest the results were worth inclusion. Cipolletta et al.’s (Citation2018) Conversation Analysis study had 15 client sessions from 2 therapists working with 5 clients, which is a reasonable size for this methodology, although limited in the range of therapists.

A common weakness with four of the research papers was the lack of exploration of the relationship of the researchers with the research subject or participants. For example, the potential for researcher bias (Feijt et al., Citation2020); the researchers’ organisational position compared to participants (Interian et al., Citation2018; Paterson et al., Citation2019); or variation in group facilitators/interviewers (Hoffman et al., Citation2020); were not acknowledged or explored when this sort of reflexivity would be expected.

The papers (excluding Feijt et al. [Citation2020] and Cipoletta et al. [Citation2018]) were broadly in line with more positivist traditions, that is, an approach of coder validation and a general perspective that it is only “true” if all the researchers agree. Since this review, there have been other contributions to the literature showing that a greater depth of reflexivity is possible (García et al., Citation2022) whilst also using inter-rater reliability tests. Whilst most of the papers seemed to lack the rigour normally associated with qualitative work, the limited details provided of the research processes undertaken did meet the standards required for inclusion within this literature review.

Review of the content of the qualitative research

A summary of each study is presented in Appendix 1. Three of the papers explored the experiences of therapists of online working (Cipolletta et al., Citation2018; Feijt et al., Citation2020; Interian et al., Citation2018) and three the expectations or pre-conception of online working (Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019; Hoffman et al., Citation2020; Paterson et al., Citation2019). Although each of the papers had a specific objective, such as exploring therapist views about working with suicide risk (Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019) or exploring online therapy sessions in depth (Cipolletta et al., Citation2018), there were two main themes which emerged from this small selection of literature: difficulties with counsellor/client communication during a therapy session (Cipolletta et al., Citation2018; Feijt et al., Citation2020; Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019; Hoffman et al., Citation2020); and the technical competence and IT requirements of counsellor/client (Feijt et al., Citation2020; Hoffman et al., Citation2020; Interian et al., Citation2018; Paterson et al., Citation2019). Some papers also mentioned issues such as remote safeguarding, the effect of the client being in the home environment (both positive and negative); and benefits, such as better access to therapy for some clients, and the importance of the counsellor being positive about online working. These themes are developed in the next section.

Common themes emerging from the selected literature

A thematic analysis of the eleven reviewed papers identified four common areas across the selected papers: Therapeutic practice; technical concerns; perceptions of client benefits and challenges; and therapist challenges; which are described below.

Therapeutic practice

Many of the therapists not currently working online were concerned about their ability to engage fully with the client in an online environment. Studies highlighted potential issues with providing a therapeutic space due to, for example, a reduced ability to read non-verbal cues or notice bodily sensations (such as trembling) (Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019; Hoffman et al., Citation2020; Interian et al. (Citation2018)), which were also reported by those who were working online (Feijt et al., Citation2020; Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021). In a global survey of psychoanalytic therapists, who were predominantly in private practice (90%) and with the majority having delivered online therapy prior to the pandemic in some form (55%) (Békés et al., Citation2020), two thirds of respondents reported that they were able to express the same levels of authenticity or genuineness as they had in-person, yet just below half felt they were as emotionally connected as before. Around a third of respondents in Aafges-van-Doorn et al.’s (Citation2021) study noted more difficulty with reading emotions, in line with Békés et al.’s (Citation2020) study, where two thirds of therapists felt able to use their therapeutic skills online as competently and confidently as before. Despite this, only a quarter of practitioners in Békés et al.’s (Citation2020) study felt that the therapy was as effective as before. This suggests that many therapists felt able to continue their practice online but were unsure of the effect of the online medium on their practice.

A preference for face-to-face work (Paterson et al., Citation2019) seems to be implicit in much of the data, with 77% of participants in Drath and Necki’s (Citation2018) study suggesting that video technology should only be used in exceptional circumstances. Notably during the pandemic, an 80% uptake of online therapy delivery was reported in Feijt et al.’s (Citation2020) study, yet the majority of therapists in Aafjes-van Doorn et al.’s (Citation2021) study were unsure if they would continue the use of video therapy in the future, despite acknowledgement that the patient experience was broadly positive (64%) and that the therapeutic relationship was acceptable. These rating/survey studies indicated very mixed experiences of providing online therapy yet provide limited insight into the causes of these differences.

Technical concerns

One of the main components of video counselling is the technology required to facilitate the counselling session. This dependency on technology requires knowledge and skill, yet this was not always identified by groups yet to work online. For example, in a survey of counselling students thinking about online working (Paterson et al., Citation2019), only 20% mentioned concerns about equipment and technology skills, and nearly 40% did not identify any technical concerns.

The reports from those who were actually working online show quite a different picture, with technical issues being detailed and highlighted as important challenges. These difficulties included set up time of the session, system complexity, limitations of the online platform, instability of the internet connection, access to technical support and issues with client software and hardware (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Cipolletta et al., Citation2018; Feijt et al., Citation2020; Interian et al., Citation2018). Whilst these issues may generally be expected with IT infrastructure, these are also factors which may directly impact on the client experience within therapy, recognising the need for consistency and constant connection between two individuals throughout. Nevertheless, where technical issues appeared to be resolved or well supported to provide a good and reliable service, the experience appeared to be positive for both clients and practitioners (Gray et al., Citation2015). Where the practitioner is experienced with, and confident in, the application of technology, therapy delivery is considered better than for those who struggle with technology (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019; Interian et al., Citation2018).

Whilst technology appears to offer the possibility of instant and continued connection as perceived “in the room”, the reality of slow and dropped internet connections changed the experience for both therapist and client. These reported technical issues may give some insight into the difficulties with maintaining therapeutic connection (see above) reported by therapists. The difference in response of therapists depending on their technical knowledge may also be an area for future research.

Counsellors perceptions of client benefits and challenges when working online

Therapists had perceptions, beliefs and assumptions about the client experience and what appeared to be helpful for them, predominantly around the client’s environment and presentation of issues in therapy. Online working was considered helpful for those: with mobility difficulties (Hoffman et al., Citation2020); with time constraints (Feijt et al., Citation2020); living abroad and wanting therapy in their native language; with a fear of leaving home; or who did not want to be seen attending therapy (Cipolletta et al., Citation2018). In two small studies, rural and town practitioners saw more benefit than those working in cities, where the travel infrastructure may be more robust and the possibilities for anonymity greater (Hoffman et al., Citation2020; Interian et al., Citation2018). Interestingly, therapists tended to see video access as helping them to reach clients who may not attend therapy now, seeing the potential for new clients rather than enhancing work with existing clients.

Where therapists had previous experience of working with clients, studies focused more on the comparisons of perceived client experience, such as being able to find a suitable space, increased risks of distraction during the session, difficulties in being able to use the technology, and recognition that not all clients will want to access therapy this way (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Hoffman et al., Citation2020). Notably, therapists who completed more preparation with the clients regarding online work perceived better therapeutic outcomes (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021). Some therapists identified improvements in client work compared to in-the-room therapy, noting more client self-disclosure, more insight from seeing the client’s home environment, and more client independence (Feijt et al., Citation2020). Whilst these perceptions may be valid, no supportive research from a client perspective was identified to validate them.

Some practitioners raised concerns around working with specific groups who may be at risk, such as clients who experience severe anxiety, have previous experiences of trauma or are vulnerable to mental health crises (Feijt et al., Citation2020). Concerns about working with clients at risk of suicide without the containment possible with an in-the-room environment was also noted (Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019). However, Gray et al.’s (Citation2015) study with victims of domestic violence, likely to have included individuals with trauma and suicidal ideation, had perceived success. Overall, this review evidenced a key area of anxiety for therapists around working online with risk and more “serious” presenting issues/clients in crisis.

What was missing from the database searches was a clear articulation of the client experience of online therapy, either by choice or as a result of an enforced move such as during the recent pandemic. Three papers relating to the client experience of video-counselling were identified, one on client expectations of online therapy (Bleyel et al., Citation2020) suggesting concerns about technology and the lack of in-person contact, and two reporting on the experiences of clients (Goetter et al., Citation2019; Kysely et al., Citation2020), suggesting that online working appealed to some clients and not others, mirroring the reported online experiences of therapists and suggesting an area for further exploration.

Therapist challenges

A change to working online after working face-to-face with clients is likely to bring challenges to professionals and the working environment was specifically highlighted in a number of studies. The tiring nature of online working was noted (Feijt et al., Citation2020; Hoffman et al., Citation2020) with more than half of participants in Aafjes-van Doorn et al.’s (Citation2021) study revealing that they were more tired online and about a third noted the risk of them becoming distracted during a session. It seems that therapists may need time to get used to this new way of practice, specifically with the lack of physical presence involved in on-screen work compared to in-the-room therapy (Hoffman et al., Citation2020).

A publication prior to 2019 provided some evidence that qualified therapists over the age of 40 were more likely to engage in online working (to some extent) (Drath & Necki, Citation2018). Papers post 2019 suggested that practitioners who were more experienced and confident in their practice and had a more positive attitude to working online were more likely to feel positive about delivering therapy this way (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Gilmore & Ward-Ciesielski, Citation2019). Higher levels of doubt and anxiety in working online were associated with younger therapists, and those with low caseloads and limited clinical experience (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021). Although assumptions could be made about age influencing the uptake by therapists for online working (Hoffman et al., Citation2020), this research suggests that this may be more related to therapeutic and technological expertise than age specifically.

Discussion

The findings of this literature review suggest that the experience and perceptions of online working for therapists in the period up to mid-2020 is variable. Some found opportunities in delivering therapy in a new and different way, and others saw it as a lesser option compared to in-person work. Practitioner confidence in their ability to conduct therapy face-to-face is also reflected in their ability to do so online as well. It also seems that it is not age that determines a practitioner’s engagement with online working, but clinical experience and familiarity and positive engagement with IT systems. Additional IT skills training may be helpful for many existing, competent practitioners qualified in in-person counselling, with less experienced in-the-room practitioners possibly requiring both clinical and technical support to gain the confidence to move their practice online.

For those who wish to continue with online working post-pandemic a gradual upgrading of IT equipment (to deliver better audio and visual experiences in appropriate settings) and internet services would be required, together with service subscriptions to appropriate platforms, to try to provide the best possible service to clients (Barker & Barker, Citation2022). In addition, the future development of a robust IT infrastructure with support via some form of helpdesk, strong internet connections, appropriate hardware and easy to use and adapt software will assist practitioners in being confident in the delivery of their service. This may be an opportunity for IT providers to develop a technology package for health professionals working outside organisational infrastructure. This sort of provision could be extended to support clients with their IT systems too, if helpful.

The experience of working online elicited differing perceptions of the work, with some acceptance that a form of therapeutic practice is possible but with frustration at the limitations of the technology. These experiences have encouraged practitioners to think about how the online environment can be improved, identifying, for example, a need to explore and use functionality in online platforms more effectively (such as use of a whiteboard, completion of outcome documents online etc.) and technological and procedural support (such as a readily available help desk) (Feijt et al., Citation2020). The move online for practitioners who may not have chosen to work online ordinarily may help to identify some of limitations of online working and encourage technological development (Roth et al., Citation2021) which could be useful for practitioners in the future.

However, many practitioners and clients may remain voluntarily or involuntarily excluded from online working. Paterson et al.’s (Citation2019) study suggested that some students did not identify as online counsellors, hence there may always be practitioners (and clients) for whom this type of therapy is unattractive. There will also be clients with limited IT options and skills, a poor internet connection, or lack of access to the IT infrastructure or private space required. Here, video counselling may not be feasible and such clients are effectively excluded from the service. There is concern that digital exclusion may impact those with significant mental health difficulties more than the general population, suggesting this is an area for further exploration (Spanakis et al., Citation2021).

Despite the potential for digital exclusion, video counselling may provide therapy access for hard-to-reach groups, may simply provide a very convenient and cost-effective option (Nobleza et al., Citation2019), or may allow clients to access specific therapy specialisms to match their needs. This element of client choice may be a significant factor in how well video-therapy works in future (Goetter et al., Citation2019).

Although there are some clear benefits to online working, practitioner concerns about their online therapeutic practice continue to be reported. The findings suggested that some therapists felt they had lost access to the immediacy of felt responses from the client when working online. Previous research into the working alliance, which encompassed relational factors between client and therapist such as trust as well as a focus on goals and tasks (Preschl et al., Citation2011), described the online working alliance as strong yet inferior to face-to-face working (Norwood et al., Citation2018), and an earlier meta-analysis (Barak et al., Citation2008) showed online outcomes as good as face-to-face therapy. It may be that online therapy feels “good enough” to the client, but to the therapist “not their best work”. Yet, in one of the few client studies completed with couples in therapy, the sense of connection and emotion in the room was also a significant part of the feedback from clients, with some finding lack of emotion helpful in their process whilst others found it inhibiting (Kysely et al., Citation2020). Another small study conducted with clients who had moved from in-person therapy to video counselling suggested that the felt sense of another person in the room was also missing for them in the new environment (Sheehy, Citation2021). This difference in experience between in-person and online therapy could be usefully explored with both clients and therapist to help to identify the needs and online therapeutic process of both. It is also worth remembering that therapists often choose their career to work closely with people. The value of the social interaction and the need for the physical sense of the other for practitioners cannot be underestimated.

Practitioner health when working online is also an area for further exploration, with tiredness and concerns about online working with high-risk clients noted. A more recent study found that risk management was a significant challenge for practitioners, with issues identified around perceptions and experiences of control when working online (Smith & Gillon, Citation2021). Findings from domestic violence practitioners working with women during the pandemic (Pfitzner et al., Citation2022) draws attention to the implications of remote service delivery on practitioner mental health and well-being, especially when working with complex or trauma-based cases. Determining what additional support may be required for practitioners to work safely online, as well as which client groups can be worked with safely and which cannot, are much needed areas of research.

Since the pandemic, some counselling programmes in the UK now offer an online option to counselling trainees, where a proportion of trainee counselling hours can be undertaken online, recognising the growth of online working. This may provide opportunities to conduct further research into remote and in-person delivery with practitioners who are comfortable with both. Ultimately, however, the current research suggests that online working may not be valued by, or appropriate for, all therapists or all clients.

Opportunities for future research

Research into the experience of video therapy for counsellors and psychotherapists is still in its infancy, as noted by the small number of papers identified in this literature review. It is notable that over half the papers initially categorised were associated with using technology to deliver therapy, and over half the papers associated with synchronous delivery of therapy were associated with proving it was a reasonable alternative to in-person therapy. This shows that there is significant potential for further research to determine a clearer picture of what works well and what could be usefully changed to improve the online therapeutic experience for both clients and therapists.

Whilst there were clear opportunities to use therapy skills to develop a therapeutic relationship online, the loss of in-person contact seemed to be a loss for some therapists and may be mirrored by the client experience, yet for others the experience was extremely positive. Further research to determine the scope and effect of such changes in delivery on therapists and clients would be helpful and could allow exploration of some of the nuances in therapeutic experience hidden within the reported studies.

Technical concerns were also raised regarding video therapy by practitioners and yet we live in a world of continually developing technology. The technological concerns were wide ranging, from the limitations of the platform used to the speed of connection between therapist and client. Further research to determine how technology can enhance or detract from the therapeutic experience, and how counselling professionals can take advantage of advancing technology to enhance online practice would be valuable.

What still requires further research is the client experience of video therapy, what was helpful and unhelpful in that context, and whether or how this is affected by previous in-person experiences. This would be useful in helping to understand where and how online working can be most beneficial.

Study limitations

As a rapid review, this study was limited by the time and resources available to the research team during the 2020/21 pandemic. Whilst care was taken to provide as comprehensive a search as possible, there may be additional, relevant papers not included here due to decisions taken to streamline the search process.

The study may also be limited by the objective to identify research specifically on online synchronous therapy. As this is an under researched area and the quality of the papers identified were moderate to strong, rather than excellent, this will impact on the robustness of the proposed conclusions.

The data collection was completed in late 2020, with analysis and writing up completed during 2021/22, reflecting team time constraints. Hence the study represents a snapshot of an evolving area where the perspectives of practitioners and clients may be subject to change through their (sometimes unavoidable) experiences.

There were substantial increases in research activity on online working during this period and subsequently. It should be noted that publications from December 2020 through to the current day are not covered by this review and that this s a limitation on the findings. Inclusion of more recent research may uncover additional themes not recognised within this paper.

Finally, some of the papers were produced pre-pandemic whereas others were amongst the first publications of online experiences during the pandemic. Clearly the social context of these papers is different. Although the small number of papers identified led to combining the papers in the analysis, it should be noted that with larger numbers of papers, it may be appropriate to separate these into pre- and post-pandemic for both analysis and reporting.

Conclusions

We are at the beginning of a potential online revolution. Increasing practitioners technical, IT and clinical knowledge to allow them to fully embrace and gain benefit from online working could be hugely beneficial to the profession and to some client groups. Whilst working online is not the answer for all clients or for all therapists, identifying more clearly those who can help and those who can be helped through this medium of video counselling would be an important step forward.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by York St John University for this study.

Prospero registration

PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020204705

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr Alison Rolfe of Newman University to the early scoping stages of the research. Some elements of this paper were previously presented at the BACP Research Conference 2021 (Roddy et al., Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jeannette K. Roddy

Jeannette K. Roddy is CEO of Dactari Ltd, which offers online counselling, counsellor training, and research specialising in working with experiences of domestic abuse. She is a BACP accredited counsellor/psychotherapist, an Honorary Senior Lecturer at the University of Salford and an Honorary Research Fellow at York St John University.

Lynne Gabriel

Lynne Gabriel, OBE is Professor of Counselling and Mental Health at York St John University. Lynne is Director of the University's Communities Centre and leads a taught postgraduate research year. Her research interests include domestic and relational abuse and associated trauma, relational ethics, pluralistic concepts, and bereavement.

Robert Sheehy

Robert Sheehy is a qualified MBACP counsellor and psychotherapist, currently working with students within an educational setting. He received his MSc in Counselling & Psychotherapy (Professional Practice) from the University of Salford. His current research interests include the uses of technology within counselling to help different client groups and presenting issues.

Divine Charura

Divine Charura is a Professor of Counselling Psychology at York St John University (England). He is a Practitioner Psychologist and Counselling Psychologist and is registered with the Health and Care Professions Council in England. Divine’s research interests are in psychological Trauma across the lifespan. For some of Divine’s Publications please see https://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/profile/2104

Ellen Dunn

Ellen Dunn is a policy and research officer at the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy. She received her MSc in Global Health at University College London, and her research interests include psychotherapy and migrant mental health.

Jordan Hall

Jordan Hall is an administrator and researcher at the Counselling and Mental Health Centre at York St John University, having studied for a BSc in Psychology and MSc in Cognitive Neuroscience.

Naomi Moller

Naomi Moller is a Professor in the School of Psychology and Counselling and also current UK Chapter President of the Society for Psychotherapy Research. Current research interests for Naomi include video-based (online) counselling and the counselling and mental health care experiences of trans (including nonbinary) people.

Kate Smith

Kate Smith is Professor in Counselling and Mental Health at the University of Aberdeen where she oversees the MSc Counselling programme and the Counselling research clinic. She is a pluralistic practitioner and undertakes research and supervision in the area of process and outcomes in the pluralistic approach to therapy.

Mick Cooper

Mick Cooper is Professor of Counselling Psychology at the University of Roehampton. He is a chartered psychologist, a UKCP-registered existential psychotherapist, and a Fellow of the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. Mick is author and editor of a range of texts on person-centred, existential, and relational approaches to therapy.

References

- Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Békés, V., & Prout, T. A. (2021). Grappling with our therapeutic relationship and professional self-doubt during COVID-19: Will we use video therapy again? Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 34(3-4), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1773404

- Barak, A., Hen, L., Boniel-Nissim, M., & Shapira, N. A. (2008). A comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 26(2-4), 109–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228830802094429

- Barker, G. G., & Barker, E. E. (2022). Online therapy: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 health crisis. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 50(1), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2021.1889462

- Békés, V., & Aafjes-van Doorn, K. (2020). Psychotherapists’ attitudes toward online therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000214

- Békés, V., Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Prout, T. A., & Hoffman, L. (2020). Stretching the analytic frame: Analytic therapists’ experiences with remote therapy during COVID-19. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 68(3), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065120939298

- Bleyel, C., Hoffmann, M., Wensing, M., Hartmann, M., Friederich, H. C., & Haun, M. W. (2020). Patients’ perspective on mental health specialist video consultations in primary care: Qualitative preimplementation study of anticipated benefits and barriers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(4), e17330. https://doi.org/10.2196/17330

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should Inotuse TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

- Brown, S. (2017). Is counselling women's work? Therapy Today, 28(2). https://www.bacp.co.uk/bacp-journals/therapy-today/2017/march-2017/is-counselling-womens-work/.

- Brown, S. (2020). Working remotely. Therapy Today, 31(4), 21–24. https://www.bacp.co.uk/bacp-journals/therapy-today/2020/may-2020/articles/in-practice/.

- Calkins, H. (2021). Online therapy is here to stay. Monitor on Psychology, 52(1), 78–82. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/01/trends-online-therapy.

- Cipolletta, S., Frassoni, E., & Faccio, E. (2018). Construing a therapeutic relationship online: An analysis of videoconference sessions. Clinical Psychologist, 22(2), 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12117

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. Retrieved July 9, 2021from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

- Drath, W., & Necki, S. (2018). Online Psychotherapy: Polish Psychotherapists; Perspective. Psychoterapia, 3(186), 55–63. http://www.psychoterapiaptp.pl/uploads/PT_3_2018/ENGver55Drath_Psychoterapia_3_2018.pdf.

- Feijt, M., Kort, Y. d., Bongers, I., Bierbooms, J., Westerink, J., & IJsselsteijn, W. (2020). Mental health care goes online: Practitioners’ experiences of providing mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(12), 860–864. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0370

- Full, W., Vossler, A., Moller, N., Pybis, J., & Roddy, J. (2024). Therapists' and counsellors' perceptions and experiences of offering online therapy during COVID-19: A qualitative survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 703–718. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12707

- García, E., Di Paolo, E. A., & De Jaegher, H. (2022). Embodiment in online psychotherapy: A qualitative study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 95(1), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12359

- Gilmore, A. K., & Ward-Ciesielski, E. F. (2019). Perceived risks and use of psychotherapy via telemedicine for patients at risk for suicide. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 25(1), 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X17735559

- Goetter, E. M., Blackburn, A. M., Bui, E., Laifer, L. M., & Simon, N. (2019). Veterans’ prospective attitudes about mental health treatment using telehealth. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 57(9), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20190531-02

- Gray, M. J., Hassija, C. M., Jaconis, M., Barrett, C., Zheng, P., Steinmetz, S., & James, T. (2015). Provision of evidence-based therapies to rural survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault via telehealth: Treatment outcomes and clinical training benefits. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 9(3), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000083

- Higgins J. P. T., Thomas J., Chandler J., Cumpston M., Li T., Page M. J., & Welch V. A. (Eds.). 2022. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Hoffman, M., Wenseng, M., Peters-Klimm, F., Szecsenyi, J., Hartmann, M., Friederich, H.-C., & Haun, M. W. (2020). Perspectives of psychotherapists and psychiatrists on mental health care integration within primary care via video consultations: Qualitative preimplementation study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e17569. https://doi.org/10.2196/17569

- Interian, A., King, A. R., St. Hill, L. M., Robinson, C. H., & Damschroder, L. J. (2018). Evaluating the implementation of home-based videoconferencing for providing mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 69(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700004

- Irvine, A., Drew, P., Bower, P., Brooks, H., Gellatly, J., Armitage, C., Barkham, M., McMillan, D., & Bee, P. (2020). Are there interactional differences between telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy? A systematic review of comparative studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.057

- Kysely, A., Bishop, B., Kane, R., Cheng, M., De Palma, M., & Rooney, R. (2020). Expectations and experiences of couples receiving therapy through videoconferencing: A qualitative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02992

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2009). Depression the treatment and management of depression in adults (Updated Edition) National Clinical Practice Guideline 90. London: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG90NICEguideline.pdf.

- Nobleza, D., Hagenbaugh, J., Blue, S., Stepchin, A., Vergare, M., & Pohl, C. A. (2019). The use of telehealth by medical and other health professional students at a college counseling center. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 33(4), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2018.1491362

- Norwood, C., Moghaddam, N. G., Malins, S., & Sabin-Farrell, R. (2018). Working alliance and outcome effectiveness in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review and noninferiority meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(6), 797–808. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2315

- Paterson, S. M., Laajala, T., & Lehtelä, P. L. (2019). Counsellor students’ conceptions of online counselling in Scotland and Finland. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 47(3), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1383357

- Pfitzner, N., Fitz-Gibbon, K., & Meyer, S. (2022). Responding to women experiencing domestic and family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring experiences and impacts of remote service delivery in Australia. Child & Family Social Work, 27(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12870

- Preschl, B., Maercker, A., & Wagner, B. (2011). The working alliance in a randomized controlled trial comparing online with face-to-face cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-189

- Roddy, J., Gabriel, L., Smith, K., Moller, N., Cooper, M., Sheehy, R., & Hall, J. (2021). Practitioner understanding, experiences and perceptions of online synchronous therapy. 27th Annual BACP Research Conference: Promoting collaboration in research, policy and practice, Online.

- Roth, C. B., Papassotiropoulos, A., Brühl, A. B., Lang, U. E., & Huber, C. G. (2021). Psychiatry in the digital age: A blessing or a curse? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168302

- Sheehy, R. (2021). Understanding the perceptions and experiences of UK-based clients transferring from face-to-face to online counselling during the Covid 19 pandemic [MSc Dissertation]. University of Salford.

- Smith, J., & Gillon, E. (2021). Therapists’ experiences of providing online counselling: A qualitative study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(3), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12408

- Smith, K., Moller, N., Cooper, M., Gabriel, L., Roddy, J., & Sheehy, R. (2022). Video counselling and psychotherapy: A critical commentary on the evidence base. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12436.

- Spanakis, P., Peckham, E., Mathers, A., Shiers, D., & Gilbody, S. (2021). The digital divide: Amplifying health inequalities for people with severe mental illness in the time of COVID-19. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 219(4), 529–531. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.56

- Tricco, A. C., Antony, J., Zarin, W., Strifler, L., Ghassemi, M., Ivory, J., Perrier, L., Hutton, B., Moher, D., & Straus, S. E. (2015). A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Medicine, 13(1), 224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6

- York, K. (2020). BAME representation and psychology. The Psychologist, 33, 4. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-33/january-2020/bame-representation-and-psychology.