ABSTRACT

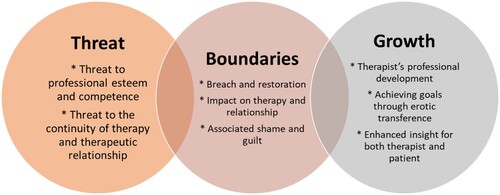

The central aim of the current study is to further the understanding of how therapists identify and understand erotic transference in therapy, and how they perceive it to influence the therapeutic processes and alliance. Answers were analyzed thematically using an open-coding analysis. A total of 116 therapists participated in the study reflecting on how erotic transference is experienced in the therapeutic setting. Data analysis yielded three main themes: (1) threat; (2) boundaries; and (3) growth. The threat theme included two subthemes: Threat to the therapeutic process and threat to the therapist’s professional-esteem. Growth also consisted of two subthemes: development of the therapist and opportunity for insight (into the inner world of the patient). The present study subscribes to the idea that erotic transference is a significant aspect of the therapeutic setting and, if addressed appropriately and more comprehensively, can have a great impact on the patient’s healing process.

Introduction

According to the psychoanalytic theory, transference refers to the process of transposing unconscious feelings about one significant individual onto another significant individual (Blum, Citation1973). One way to think about the experience of transference is that it is a way to make sense of a current experience by seeing the past in the present and limiting the input of new information (Kay & Kay, Citation2008). In therapy, transference is conceptualised as the patient’s attempt to relive childhood experiences (Freud & Strachey, Citation1915); it is thought to be a crucial component in the therapeutic relationship, and the study of this topic is generally incorporated into therapists’ education from the start. However, transference is usually discussed in a general way. Discussion of erotic transference, specifically, is often limited.

The term erotic transference is psychoanalytic in origin, deriving from Freud’s (Citation1915) paper “Observations on Transference Love.” Erotic transference is defined as any of the patient’s fantasies about the therapist that contain elements that are primarily romantic, intimate, sensual, or sexual (Book, Citation1995). Erotic countertransference encompasses romantic, intimate, sensual, or sexual feelings experienced by the therapist toward the patient. Erotic transference encompasses two experiences – erotic transference and eroticized transference – that have a different intensity and underlying motivation, and that require different interventions.

The psychoanalytic theory (Freud, Citation1921) explains that erotic transference should not be viewed as merely sexual attraction towards the therapist (Colom-Timlin, Citation2014), as this view simplifies the phenomenon. According to the psychoanalytic theory, the capacity to love develops within an individual’s earliest social environment – between an infant and the caregiver (Winnicott, Citation1956). These early interactions are and feelings of love and desire are then replayed in the therapeutic alliance (Welles & Wrye, Citation2013). If the capacity for love was damaged in early childhood experiences, patients will be unable to focus on developing appropriate insights and are likely to attend their sessions for closeness to the therapist, with the hope that the therapist will reciprocate their love (Rachman et al., Citation2009). According to Freud and Strachey (Citation1915), erotic transference is a defense mechanism used by patients to prevent them from remembering painful memories from the past. Ferenczi described erotic transference as an enactment of the child's seduction and early sexual trauma in the current therapeutic situation (Ferenczi, Citation1933).

Existing research on erotic transference is scarce, and focuses on three main areas: the prevalence of erotic transference (sexual attraction towards the therapist) and countertransference (sexual attraction towards the patient); the perceived training in this area and feeling of competence in managing erotic transference in therapy; and the emotional reactions therapists experience in reaction to erotic transference (e.g. shame, embarrassment).

As for prevalence, research consistently shows that erotic transference is extremely common in therapy (Mann, Citation1997). Erotic countertransference is also prevalent, with 95% of male therapists and 76% of females therapists reporting ever experiencing sexual attraction towards a patient (Pope et al., Citation1986). In a more recent study, seven out of ten (70.6%) therapists reported they found a patient sexually attractive, and almost a quarter (22.8%) fantasised about a romantic relationship with a patient (Vesentini et al., Citation2022).

Although erotic feelings in therapy are extremely common, research shows it is addressed in training programs in a very limited fashion. In a qualitative study that interviewed six qualified therapists, all have reported experiencing what they understood to be erotic transference (Rodgers, Citation2011). More than half of them were interested to learning more about how to manage and use it therapeutically. Other studies surveying therapists also found, therapists report a lack of training and poor knowledge on how to manage erotic transference (Sehl, Citation1998; Spilly, Citation2008). In a study conducted among 72 students who study towards their Master in Social Work (MSW), half stated that they had experienced sexual attraction to at least one patient. At the same time, the vast majority of students (68.1%) reported their training did not prepare them to handle erotic countertransference (Begun, Citation2011). Therapists who attended courses and classes that addressed human sexuality, felt more prepared and capable to detect erotic transference in therapy (Meritt, Citation2011).

The reaction to erotic transference varies among therapists. However, most therapists feel uncomfortable with erotic transference, and some resist awareness of it (Barnewall, Citation2016; Luca, Citation2018). Therapists often report negative feelings in relation to erotic transference. Namely, the research indicates that therapists often feel embarrassed, guilty, or ashamed when they become aware of the existence of an erotic transference within their relationship with the patient (Luca, Citation2018; Pope et al., Citation1986; Rodgers, Citation2011; Spilly, Citation2008). Therapists have also reported feeling angry at themselves for being aroused, as well as confused by their arousal (Rodgers, Citation2011), and they also express moralistic attitudes when it comes to erotic transference. In a study conducted among 12 trainees of counselling psychology, any sexual feelings within therapy was perceived as wrong and unethical (Luca, Citation2018).

Feelings of shame and guilt, and moralistic attitudes, may lead therapists to embrace more defensive and avoidant strategies such as wearing a wedding ring, ignoring an erotic transference, or telling patients that sexual involvement is prohibited (Luca, Citation2018). This defensive and avoidant approach toward erotic transference can also be attributed to the absence of discussing this phenomenon in core training. Therapists report lacking both knowledge on erotic transference as well as clear guidelines as to how to deal with it effectively (Barnewall, Citation2016; Colom-Timlin, Citation2014). Resultantly, therapists lack confidence in handling erotic issues and in setting clear boundaries (Barnewall, Citation2016).

Although therapists acknowledge the value of exploring erotic transference within the therapeutic relationship (Rodgers, Citation2011), they often tend to deny or dismiss erotic transference feelings because they are afraid of frightening the patient or simply feel uncomfortable discussing sexual-related issues. Supervision and guidance have been found to be unhelpful in managing erotic transference (Pope et al., Citation1986). In cases where erotic feelings were reciprocal, therapists were reluctant to raise this issue during supervision and experienced higher levels of anxiety and discomfort (Spilly, Citation2008).

Understanding erotic transference is important for the therapeutic process as it allows early traumas to be processed and verbalised for the first time in the patient's life (Alvarez, Citation2010). The resistance, when both client and therapist collude to deny transference feelings for each other, impedes therapeutic work (Kahn, Citation1997). Little attention has been given in the literature to the potential benefits of working in an ethical manner with erotic transference, which may facilitate change by identifying the patient’s relational needs (Giovazolias & Davis, Citation2001; Stirzaker, Citation2000).

Gaps in the literature

Erotic transference is a complex clinical entity. A full understanding of it has not yet been reached. Previous literature has made a significant contribution to estimating how prevalent erotic transference and countertransference are (Giovazolias & Davis, Citation2001; Pope et al., Citation1986), and in describing the lack of supervision and training in this area (Krausz, Citation2016; Meritt, Citation2011; Pope et al., Citation1986; Sehl, Citation1998; Vesentini et al., Citation2022). In addition, research in the field of erotic transference illustrated the varied emotions that emerge among therapists when they encounter erotic transference and countertransference in therapy (Luca, Citation2018; Pope et al., Citation1986; Rodgers, Citation2011; Spilly, Citation2008). However, there is very little information available about how therapists identify and understand erotic transference. The current study aims to further the understanding of how therapists identify and understand erotic transference in therapy, and how they perceive it affects the therapeutic process. We wish to identify themes related to therapist’s experience with erotic transference, and examine how the different experiences and concerns intersect with one another. This study is another step on the way towards conceptualizing and further measuring erotic transference and countertransference in therapy (Bodenheimer, Citation2011).

Methods

Participants

The study enrolled a total of 116 participants including 101 women and 15 men with 101 (86.3%) of identifying as heterosexual. The mean participant age was 45.84 (SD = 9.68, age range: 28–70). The majority of participants identified as either married or in a relationship (75%), and the rest were either separated or divorced (13.8%), or single (11.2%) and the majority of respondents had children (n = 97, 83.6%). The sample was highly educated, only three people (2.6%) had a bachelor’s degree, 99 (84.6%) held a masters degree, and 14 (12.1%) had a PhD. The majority of participants (n = 114, 97.4) were Jewish, and non-religious (82.9%). The majority of participants (61.5%) reported an income higher than the average income in Israel (10,584 NIS).

More than half of the sample (n = 63, 53.8%) were social workers, and the rest had a degree in psychology (n = 17, 14.5%), or other therapeutic degrees (n = 36, 31.7%), such as art therapy and family therapy. The majority of the sample reported undergoing continuing education courses and certifications (following their academic degree), such as psychotherapy (n = 46, 39.3%), couples therapy (n = 38, 32.5%), sex therapy (n = 25, 21.4%), and other certifications (n = 19, 16.2%) such as EMDR, CBT, art therapy, somatic experience (SE) and Post Traumatic Transformation (PTT). The sample consisted of very experienced therapists, with 25.6% reporting 20 and more years of clinical experience, 15.4% reporting 15–20 years of clinical experience, 24.8% reporting 10–15 years of clinical experience, 26.5% reporting 5–10 years of clinical experience, and only 6.8% reporting less than five years of clinical experience.

Sampling and procedure

The sample was collected through social media (e.g. Facebook, WhatsApp). To be included in the present study, participants had to (a) have at a minimum a bachelor’s degree in the following professions: social work, psychology, psychotherapy, counseling, or couples and sex therapy, and (b) be able to read and answer a survey in Hebrew. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Haifa [blinded for review]. Participants did not sign informed consent, but received detailed information concerning the study prior to their responses. Participants filled out an online survey using Qualtrics, a web-based survey and data service. Qualtrics servers are protected by high-end firewall systems, and promises anonymity. Participants completed the link voluntarily. After the university ethics committee approved the study, an anonymous link using Qualtrics software was distributed via social media. Participants were invited to take part in a short anonymous study on erotic transference. Facebook recruitment is a cost-effective tool for rapidly recruiting large samples of participants and obtaining public opinion data. Recruitment via Facebook also enables subject anonymity (Samuels & Zucco, Citation2013). The survey was published on Facebook pages of different groups in which the first author participates. According to Baltar and Brunet (Citation2012), this method increases participants’ level of confidence because researchers display their personal information (Facebook profile) and also participate in participants’ groups of interest (e.g. psychotherapy, and couples and sex therapy groups). However, the main limitation of Facebook recruitment is that the representativeness of the sample cannot be entirely determined (Ramo & Prochaska, Citation2012). The survey was conducted between March and May 2021. The participants initially completed a background questionnaire assessing demographics (e.g. gender, age, country of origin, years of education, marital status, and number of children). Participants were then asked to respond to two open-ended questions on erotic transference expressions in and consequences in therapy: (1) Have you experienced erotic transference in your practice? Please describe how it was expressed within the therapeutic setting; (2) Have these expressions of erotic transference advanced or harmed the therapeutic process and/or the therapeutic relations between you (the therapist) and the patient? A brief introduction to the importance of the responses and a flexible answer space that increases as needed within the web-survey was provided to enhance the quality of responses (Smyth et al., Citation2009). Due to confidentiality obligations, we are unable to share any data or information related to this project.

Data analysis

A line-by-line, open-coding analysis was employed (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). The analysis did not use preconceived a priori themes, but allowed themes to emerge directly from the text (Creswell, Citation1998). The answers to the open-ended questions were analyzed thematically, according to Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) approach. All three authors familiarized themselves with the data individually, reading and rereading the data, and noting down initial ideas. Then, initial codes were generated across the entire data set, and quotes relevant to each code were collated. In the second stage, codes were discussed among the authors and were grouped into three main themes to identify variations in responses (see ). All three authors (AGM, OL, and LR) defined and named themes and formulated the overall storyline emerging from the texts. Finally, to obtain a general picture of the distribution of the different attitudes, we counted the number of times each theme appeared. Answers which were complex and contained more than one theme were coded into the theme that was most dominant in the response. “Do not know” responses received a separate code.

Table 1. Organization of the themes and codes (n = 116).

Results

Identifying erotic transference

As for identifying erotic transference in therapy, therapists gave many examples, that ranged between explicit erotic transference and more implicit forms of erotic transference. Among the examples, therapists mentioned the following: compliments or comments on the appearance of the therapist (e.g. “you lost wight,” “you did something different with your hair”), sharing erotic dreams or fantasies about the therapist, constant demands and requests for love (e.g. “do you love me?” “Am I you favorite patient?”), flirts, request for a hug or a kiss, comparing the therapist to a current partner (e.g. “if my wife was just a little more like you”), attempts to ask about the therapist’s sexual life, use of nick names, looking or staring at the body and especially intimate parts of the therapist, and one participant said she received a marriage proposal. Interestingly, some participants also interpreted significant hate as erotic transference.

Data analysis yielded three main themes (see ): (1) threat; (2) boundaries; and (3) growth (enabling factors). The threat theme included two subthemes: threat to the therapeutic process and threat to the therapist’s professional esteem. Growth also consisted of two subthemes: development of the therapist and opportunity for insight (into the intimate world of the patient).

This is not good: erotic transference as a personal and relational threat

Forty-six percent (n = 52) of respondents viewed erotic transference as a threatening phenomenon that needs to be avoided. This theme seemed to be the most dominant one, with the main idea being that erotic transference has enormous potential to destroy the therapeutic process and threaten the therapist’s personal and professional sense of self. self-esteem.

Erotic transference was perceived as dangerous to the therapeutic process: both to the therapeutic alliance and to the therapist’s sense of control of the therapy. In many cases, erotic transference was seen as threatening because it was perceived as a direct attempt to sabotage the therapeutic process, especially when it was difficult to manage. In the words of one therapist: “I remember once that the erotic transference was sabotaging [the therapy], and I didn’t manage it very well.”

Feeling threatened by an erotic transference seemed tied to the therapist’s uncertainty regarding how to address or handle this experience. Some therapists felt that they did not know whether or how to discuss erotic feelings: “I felt that I could not talk about it. I didn’t know how to.” Another therapist described feeling paralyzed by the erotic transference:

“When I was in my internship, I was paralyzed by an erotic transference. I did not handle it well at all. While it may have seemed that I was containing it, I was actually very frightened, and did not properly address it. I felt stressed and uncomfortable, and I was eager to terminate that therapy.”

Nineteen (16.81%) therapists said that when they felt they lacked the ability to properly address the challenge posed by the erotic transference in the therapeutic process, they experienced a sense of threat to their professional self-esteem. One therapist said that she couldn't deal with it because it was so “paralyzing” and took place at a critical moment in her training: “I was an intern and I still remember it today.” Another described it as “a continuous feeling of lacking the ability to explore this territory with the patient,” despite the fact that she identified the occurrence of erotic transference and was willing to address it. Another described how “it [may have] felt as if I contained it but in fact, I was mortified, and I could not deal with it properly.” Another therapist described that her lack of competency in dealing with the erotic transference made the situation worse:

“Despite attempts to deal with the patient's obsession with me for more than six months, and the supervision that I received, I had to bring the therapy to an end because it felt as if it had become unsafe for me.”

Ethics above all: erotic transference as a boundary breach

Another theme that was discussed by a small number of respondents (n = 12,10.62%) was perceiving the erotic transference as a boundary breach, or an attempt to violate the boundaries of the therapeutic setting. Therapists were concerned with how to maintain therapeutic boundaries. One said: “The patient was having a hard time with the boundaries of the therapeutic relationship,” and the challenge of maintaining the boundaries was discussed in relation to the therapist’s experience: “I have to learn to set boundaries, create and build a proper dialogue with [the patient] about sexuality, and I do not know how to do that. I’m inexperienced with that.”

Therapists discussed the need to set clear boundaries in order to explore the erotic transference. Setting clear and ethical boundaries while empathically responding to the patient was one of the main challenges discussed by participants. Although their comments expressed an understanding of the need for boundaries, they also feared that setting boundaries would make the patient feel rejected or abandoned, and would thereby pose a risk for premature termination.

Breaking cycles and gaining insight: erotic transference as an opportunity for growth

Growth was the most widely discussed theme with 58 (51.33%) of therapists writing about this aspect. Growth was discussed in regard to two main aspects: the therapeutic process and the therapist’s professional sense of self.

According to the participant narratives, the main advantage of the erotic transference in therapy was the way it enabled therapists to learn about the patient and especially about the patient’s need for love and recognition, early needs, and attachment style. One therapist wrote: “The erotic transference helped me and the patient to understand his self-object relations, and anxieties over relationships.” Another therapist was able to see, via the erotic transference, how her patient used seductiveness within interpersonal relationships:

“The seduction on her part and my reaction to it allowed me to see the way this patient created relationships and the way people responded to her. The context of her background and the content that emerged in therapy helped me to think about her deep needs within a relationship and her fantasies regarding connecting with others.”

Another therapist described the benefits of allowing patients to practice with their therapists the ability to be desired and to feel worthy:

“When patients flirt [with us] in the clinic, I think it's their attempt to connect, in a safe space. In my experience, I have noticed that after this flirtation happens, patients also experience a change in their romantic status in the outside world.”

According to some participants, the erotic transference allowed them to directly discuss the patient’s emotional pain, deprivation, and different patterns. One therapist even said that she did not think she would have been able to discuss some of the important content that came up if it had not been for the erotic transference:

“In most cases, the erotic transference advances the therapy because it enables closeness and discussion of some content that would otherwise be hard to get to in any other way. I believe the erotic transference helped me get to this content and to better understand the inner world of the patient.”

Erotic transference was discussed not only as a way to better understand the patient, but also as an important piece of intersubjective work:

“In situations where I identified erotic transference content, I used it, and doing so deepened the therapeutic process. It is possible to use the “here and now” to help the therapist understand the patient's patterns. The encounter between the patient's needs and the therapist’s ability to address those needs, taking into account the patient’s family history, can lead to greater insights. For me this is an opportunity to test and self-examine my reactions in the clinic.”

Another main aspect of growth in relation to erotic transference was patients’ understanding of their romantic and sexual lives. One therapist explained:

“In a way, the erotic transference helped the patient bring passion back into his life and to choose how to invest in his relationship.” Another therapist wrote, “We were able to shift the discussion from why he feels these feelings toward me to what he is looking for in a relationship with a significant other.”

Interaction between themes

The majority of the sample viewed erotic transference as an opportunity for growth (n = 72, 61.5%). Viewing erotic transference as a threatening situation was indicated by 40 participants (34.2%). Only ten (8.4%) participants viewed erotic transference as a boundary breach and were concerned about boundary issues. Following the coding process, we examined how many participants had more than one code (interaction between two or more themes). We found that being coded for more than one theme was not common. Only three participants (2.6%) were coded with both threat and boundaries concerns, and four participants (3.4%) discussed both boundaries and growth. The largest group to report on more than one theme, were participants which discussed both threat and growth (n = 10, 8.5%). Only one participant had discussed all three themes (threat, boundaries, and growth). To identify correlation between themes and with sociodemographic variables, we conducted a Spearman correlation test. We found that threat was negatively associated with growth (r = -.54, p = .000) but unrelated to boundaries. Being male was significantly associated with having more concerns around boundaries (r = .34, p = .000). A significant negative correlation was found between religiosity and viewing erotic transference as an opportunity for growth (r = -.23, p = .012), meaning, the more religious one defined themselves, the less they viewed erotic transferences as a mean for growth in therapy. Surprisingly, age, years of education, and years of experience were unrelated to any of the themes coded. In addition, no significant differences were found between social workers to therapists with other training (e.g. psychologists, art therapy).

Discussion

The current study adds to previous literature in the field as it advances the empirical investigation of a very complex psychodynamic phenomenon: the erotic transference. Our findings reveal how therapists identify and understand the erotic transference in therapy, identifying three main themes: threat, boundaries, and growth.

Erotic transference as a personal and relational threat

In the current study, the threatening aspect of the erotic transference represented one of the three main themes in the participants’ responses regarding their experience of this phenomenon. The theme of threat was divided into two main characteristics: a threat to the therapeutic process and a threat to the therapist’s professional self-esteem.

Participants admitted to feeling their professional self-confidence threatened on two levels. One, they first had to have the appropriate knowledge and level of experience to identify the erotic transference (i.e. by interpreting gestures of a friendly or romantic nature). Second, the erotic transference in and of itself was experienced as a threat, especially when a patient explicitly or provocatively expressed sexual feelings toward the therapist.

The reasons that an erotic transference can be threatening to a therapist are varied. For one, an erotic transference can create an environment in which therapist and patient are on the same level.

Aspects of the therapist that he/she may not wish to have on display may be revealed, and the patient may feel a sense of power or control over the process in a way that tips the balance and undermines the therapist’s professional standing.

One of the main reasons for that erotic transference may be understood as threatening, can be explained by incest anxiety. If the therapeutic relations are perceived as a relationship of a parent–child nature, if sexual tension enters this relationship it is forbidden (Davies, Citation2001). Also, there is also a fear that the erotic transference is a result of early traumatic experiences of the patient, and any discussion about this erotic transference can be unsafe and even harmful for the patients, as it can lead to the reliving of the trauma (Davies, Citation2001).

However, it is the therapist’s professional responsibility to identify the transference and not avoid its existence, as discussing an erotic transference is often helpful for the therapeutic process (Ladson & Welton, Citation2007). Discussing an erotic transference with patients can allow them to learn a great deal about themselves and about their relationships with others. In addition, when the therapist raises the topic of erotic transference, the patient understands that it is not a taboo subject, and that the therapist is comfortable discussing it and trying to understand it. Such openness and willingness to address the erotic transference may stop the patient from feeling embarrassed, rejected, or negatively judged (Golden & Brennan, Citation1995). Although it is important that therapists not feel threatened and thus disabled when encountering an erotic transference, it is equally important that the boundaries of the psychotherapeutic relationship be respected, for the sake of effective and safe treatment (Golden & Brennan, Citation1995; Ladson & Welton, Citation2007). It is the therapist’s job to voice this point clearly, if gently, to the patient.

Erotic transference as a boundary breach

The erotic transference as a breach of boundaries was a main concern for therapists. Indeed, when managing an erotic transference, the therapist must maintain therapeutic boundaries while also empathically responding to the patient. There is a real risk that, without having an adequate therapeutic alliance, interpreting the erotic transference or making any connection between early childhood experiences and the current erotic transference can be premature and can easily be misinterpreted or rejected by the patient. Also, when the therapist sets boundaries, the patient may feel rejected or abandoned, potentially leading to nonadaptive reenactments between the therapist and the patient, or to premature termination.

In terms of training and helping therapists to successfully manage an erotic transference, therapists must understand the necessity of setting and maintaining appropriate boundaries within the therapeutic process, despite the fact that patients may indeed feel rejected. When establishing boundaries, there might be a reenactment of early feelings of rejection, as the therapist interrupts the illusion in the transference, thus preventing the fantasy (Barnewall, Citation2016). Clearly, as stated, boundaries are a basic ethical requirement and must be clearly set within therapy; that said, the effect that such boundaries have on patients must also be acknowledged. By maintaining healthy boundaries, the therapist is ensuring and setting as a priority the patient’s safety. This point is especially salient with patients whose boundaries were previously breached, or who feel overwhelmed by the intensity of therapy. Thus, in order to minimize feelings of rejection among patients, therapists must stress the importance of maintaining firm boundaries in therapy; explain to the patient the nature and intensity of the therapeutic relationship; and educate the patient about what can happen in the work. By bringing the patient’s feelings into conscious awareness, and without being punitive, it is possible to work through any erotic issues (Schafer, Citation1993). Unlike the threat and growth themes, the boundary theme uniquely touches base on both aspects. The boundary theme in the context of erotic transference encompasses both aspects of threat and growth, highlighting its complex role in therapy. For therapists, boundary issues can represent a significant threat, particularly when they perceive these boundaries as being breached. This perception can evoke feelings of professional vulnerability and ethical dilemmas, challenging the therapist's sense of competence and security in their role. In such cases, boundary concerns are closely aligned with threats to the therapeutic process and the integrity of the therapist-patient relationship.

Conversely, the act of setting and maintaining boundaries can also be a catalyst for growth within the therapeutic context. Effective boundary management not only safeguards the therapy from ethical pitfalls but also creates a secure space for therapeutic exploration and progress. When therapists navigate boundary-setting, it can enhance their professional development and insight, fostering a deeper understanding of their patients’ dynamics and needs. Moreover, guiding patients through the process of recognizing and respecting boundaries can be therapeutic at itself, contributing to their personal growth and healthier relational patterns. Thus, while boundaries can be a source of threat when challenged, their thoughtful implementation can also be a significant contributor to both the therapist's and the patient's growth.

Erotic transference as an opportunity for growth

Indeed, working with an erotic transference is challenging and may pose a threat to treatment if mismanaged. However, it often provides a window into the internal world of patients – their unconscious conflicts, narcissistic wounds, and past trauma – and, when worked through, can be highly therapeutic. If the therapist accepts that an erotic transference is a common and expected analytic interaction which is a significant repetition of something in the developmental pasts of both therapist and patient, then an intersubjective clinical approach can be implemented to explore the patient’s erotic feelings as well as the therapist’s own erotic feelings (Krausz, Citation2016). The intersubjective approach views the erotic transference as a product of a unique transaction between patient and therapist, and as a consequence of anticipated or experienced self-object failures or unfulfilled attachment needs. Via an erotic transference, patients seek to replace missing or unsteady self-object experiences and, believing themselves unworthy of love, offer themselves as sexual objects in order to preserve the relationship with the therapist (Eber, Citation1990; Koo, Citation2001). The intersubjective approach also corresponds with the previously mentioned theme of boundaries. If the intersubjective work is successful in reenacting the past trauma within clear boundaries, then the therapist will be able to ensure the patient’s safety and protect the patient where early caregivers may have failed.

Interconnection between themes and sociodemographic relationships

Our analysis of the interaction between themes in the context of erotic transference revealed distinct perspectives among therapists. When examining the overlap between these themes, we found that the intersection was relatively rare. Only 2.6% (n = 3) of participants expressed concerns about both threat and boundaries, and 3.4% (n = 4) discussed boundaries in conjunction with growth. The most notable overlap occurred between perceptions of threat and growth, discussed by 8.5% (n = 10) of participants. Remarkably, only one individual encompassed all three themes in their perspective. This finding implies that therapists in the currents study view erotic transference in a relatively narrowed way, through the lens of either threat, boundaries, or growth. A visual representation of the intersections and overlaps of these themes, is presented in . This illustration aids in understanding how the themes of threat, boundaries, and growth not only stand-alone but also interact in complex ways, reflecting the diverse perspectives and approaches of therapists in managing erotic transference.

Sociodemographic relationships uncovered several intriguing associations. In the context of erotic transference, gender appeared to play a role, with being male significantly associated with more concerns around boundaries. For male therapists, it is possible that in the MeToo era, erotic transference is perceived as particularly hazardous. This heightened awareness around issues of consent and power dynamics may lead male therapists to avoid exploring erotic transference in therapy sessions, in an effort to maintain clear professional boundaries and avoid ethical violations.

Another important finding was that higher levels of self-defined religiosity correlated with less likelihood of viewing erotic transference as beneficial for therapeutic growth. This is likely due to the influence of religious beliefs and values, which often have specific guidelines about sexuality. Religious therapists may find it challenging to reconcile these feelings within the therapeutic context, leading them to avoid exploring erotic transference in favor of other therapeutic approaches. This highlights the impact of personal beliefs on professional practice and the importance of therapists being aware of how their own values can shape their approach to therapy.

Clinical and theoretical contribution and recommendations

The present study subscribes to the idea that erotic transference is a significant aspect of therapy and, if addressed in therapy, can have a great impact on the patient’s healing process. The contribution of the current study is twofold: On a broader theoretical level, the current study provides information that is lacking in the literature concerning the nature and dynamic of erotic transference and how it is managed within and outside therapy. Developing a body of in-depth studies and theoretical knowledge about types of erotic transference, their meaning, and how they can be understood, in reference to the narrative and the internal world of the patient, would have great importance for the field.

On the clinical level, the knowledge developed in this study can be applied to and enrich therapist practice and training, as well as increase the legitimacy of discussing erotic transference by normalizing and validating this phenomenon. In addition, the findings of the study indicate that erotic transference can sometimes be at the very core of the success or failure of the therapeutic relationship, as it combines two central difficulties in interpersonal relationships: managing and integrating emotional intimacy and sexuality. Therefore, it would seem that erotic transference should receive much greater attention in the curricula of the therapy professions and in the training of therapists and therapy supervisors. Addressing erotic transference in therapy is essential for effective practice and ethical integrity. Clinicians should be trained to recognize and manage these dynamics, emphasizing the importance of maintaining professional boundaries and the therapeutic use of such transference. Ethical considerations, including handling these feelings appropriately and understanding the potential for harm, are paramount. There is a notable gap in practical training and supervision, especially in managing therapists’ own emotional responses, such as erotic countertransference. Incorporating real-life case studies and encouraging reflective practice can enhance skills in dealing with these complex situations. Improving understanding and management of erotic transference and countertransference will strengthen therapeutic alliances, can foster deeper emotional growth for clients, and potentially enhance the overall effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions.

Limitations of the research

One of the main limitations of the current study lies in the fact that the research was not quantitative, making it difficult to reach statistical findings that are significant. Another limitation is related to the way in which the subjects were invited to participate in a study on erotic transference; that is, the invitation was distributed on the social networks of professionals and among psychotherapist lists. This recruitment strategy naturally created a non-representative sample, given that the willingness to participate in a complex study about a taboo subject naturally reveals a bias in the research population. Another significant limitation is the absence of patient perspectives. Recognizing that understanding erotic transference is inherently a relational process, incorporating patient insights would offer a more balanced view of the therapeutic dynamics involved. Similarly, our study did not delve into the topic of erotic countertransference. An exploration of how therapists perceive and manage their own erotic responses would provide a more comprehensive understanding of these complex dynamics. In addition, while the themes of threat, boundaries, and growth, as well as their overlaps and correlations with sociodemographic factors, were explored through coding, it is important to note that these analyses are not based on direct measures but on interpretations of the coded data. Therefore, these insights should be approached with caution and not taken as definitive causal relationships. They serve as an exploratory step in understanding how personal beliefs, like religiosity, can impact a therapist's approach to erotic transference in therapy, emphasizing the need for therapists to be mindful of how their own values may influence their therapeutic practice. The observed overlap between themes is particularly noteworthy, as it highlights the complex and multifaceted nature of how therapists perceive and navigate erotic transference. This complexity underscores the necessity for therapists to be aware of and reflect upon how their personal values and backgrounds might influence their approach to therapy, especially in the context of managing erotic transference. Finally, we did not ask about race, thus, we are unable to determine the diversity of the sample. Further research, particularly on long-term outcomes and diverse populations, is crucial.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Omer Lans

Omer Lans is a senior faculty member at the Tel-Hai Academic College and Serves as head of the master's degree family studies program at the School of Social Work. Dr. Lanes is a certified psychotherapist. The main area of research in which the Lanes deals is "differentiation of self” among couples and individuals. Lanes is an invited lecture in training courses for psychotherapy and couple therapy. In the past, he served as chairman of the Association for Family and Couple Therapy and as head of the Magid School of Psychotherapy.

Ateret Gewirtz-Meydan

Ateret Gewirtz-Meydan is an Associate Professor at the School of Social Work at the University of Haifa and the director of The Science of Sex Research Lab. Dr. Gewirtz-Meydan studies intimate relationship problems, sexual distress and dysfunction, and sexuality following trauma. Dr. Gewirtz-Meydan is also a research fellow at the Crimes against Children Research Center (CCRC), the Haruv Institute, and The Interdisciplinary Research Centre on Intimate Relationship Problems and Sexual Abuse (CRIPCAS). In practice, Dr. Gewirtz-Meydan is a certified sex therapist and is an invited lecture in training courses for sex counseling and therapy.

Lee Reuveni

Lee Reuveni, has a MSW in social work, and another MA in gender studies. Lee is also a certified supervisor and sex therapist working with couples in a private clinic as an EFT therapist. Reuveni is the author of the book "mommy tummy mommy heart" that explains how children are conceived in a family that has two mothers, and the book “twin bed for teen” – a guide for teenager’s sexuality.

References

- Alvarez, A. (2010). Types of sexual transference and countertransference in psychotherapeutic work with children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 36(3), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417X.2010.523815

- Baltar, F., & Brunet, I. (2012). Social research 2.0: Virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Research, 22(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241211199960

- Barnewall, Y. (2016). An exploration of erotic transference in the therapeutic encounter (Issue July).

- Begun, J. D. (2011). Smith scholar works sexual attraction to clients : Are master of social work students trained to manage such feelings ?

- Blum, H. P. (1973). The concept of eroticized transference. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 21(1), 61–76.

- Bodenheimer, D. (2011). An Examination of the historical and current perceptions of love in the psychotherapeutic dyad. Clinical Social Work Journal, 39(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-010-0298-x

- Book, H. E. (1995). The “erotic transference”: Some technical and countertransferential difficulties. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 49(4), 504–513. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1995.49.4.504

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buirski, P., & Monroe, M. (2000). Intersubjective observations on transference love. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 17, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1037//0736-9735.17.1.78

- Colom-Timlin, A. (2014). Mutual desire in the therapeutic relationship. The Irish Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 14(3), 19–24.

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions.

- Davies, J. M. (2001). Erotic overstimulation and the co-construction of sexual meanings in transference-countertransference experience. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 70(4), 757–788. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2167-4086.2001.tb00620.x

- Eber, M. (1990). Erotized transference reconsidered: Expanding the countertransference dimension. Psychoanalytic Review, 77(1), 25–39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2111560/.

- Ferenczi, S. (1933). The confusion of tongues between adults and children: The language of tenderness and passion. In M. Balint (Ed.), Final contributions to the problems and methods of psychoanalysis (3rd ed, pp. 156–167). Basic Books.

- Freud, S. (1921). A general introduction to psychoanalysis. Boni and Liveright.

- Freud, S., & Strachey, J. (1915). Observations on transference-love (Further recommendations on the technique of psycho-analysis III). Hogarht Press.

- Giovazolias, T., & Davis, P. (2001). How common is sexual attraction towards clients? The experiences of sexual attraction of counselling psychologists toward their clients and its impact on the therapeutic process. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 14(4), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070110100974

- Golden, G. A., & Brennan, M. (1995). Managing erotic feelings in the physician-patient relationship. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 153(9), 1241–1245.

- Kahn, M. (1997). Between therapist and client: The new relationship. Holt.

- Kay, J., & Kay, R. (2008). Individual psychoanalytic psychotherapy. In A. Tasman, J. Kay, J. A. Lieberman, M. B. First, & M. Maj (Eds.), Psychiatry ((3rd ed, pp. 1699–1718). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Koo, M. B. (2001). Erotized transference in the male patient-female therapist dyad. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 10(1), 28–36.

- Krausz, R. (2016). Can we transcend the next taboo? When the analyst avoids the erotic transference and erotic counter-transference. Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis / Revue Canadienne de Psychanalyse, 24(1), 24–50.

- Ladson, D., & Welton, R. (2007). Recognizing and managing erotic and eroticized transferences. Psychiatry, 4(4), 47–50.

- Luca, M. (2018). Being seduced: Trainee therapists ‘reactions to and handling of client sexual attraction in therapy. European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy, 8, 23–33.

- Mann, D. (1997). Psychotherapy: An erotic relationship, transference and countertransference passions. Routledge.

- Maroda, K. J. (2012). Psychodynamic techniques: Working with emotion in Theraputic Relationships. Guilford Press.

- Meritt, C. (2011). Examining the relationship between human sexuality training and therapist comfort with addressing sexuality with clients (Master’s thesis). https://dspace.smith.edu/handle/11020/22972.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Pope, K. S., Keith-Spiegel, P., & Tabachnick, B. G. (1986). Sexual attraction to clients: The human therapist and the (sometimes) inhuman training system. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 41(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.s.2.96

- Rachman, A. W., Kennedy, R. E., & Yard, M. A. (2009). Erotic transference and its relationship to childhood seduction. Psychoanalytic Social Work, 16(1), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228870902837772

- Ramo, D. E., & Prochaska, J. J. (2012). Broad reach and targeted recruitment using Facebook for an online survey of young adult substance use. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(1), e28. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1878

- Rodgers, N. M. (2011). Intimate boundaries: Therapists’ perception and experience of erotic transference within the therapeutic relationship. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 11(4), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2011.557437

- Samuels, D., & Zucco, C. (2013). Using Facebook as a Subject Recruitment Tool for Survey-Experimental Research. SSRN. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2101458.

- Schafer, R. (1993). Five readings on Freud’s “observations on transference-love.”. In S. E. Person, A. Hagelin, & P. Fonagy (Eds.), On Freud’s Observations on Transference-love (pp. 75–95). Yale University Press.

- Sehl, M. R. (1998). Erotic countertransference and clinical social work practice: A national survey of psychotherapists’ sexual feelings, attitudes, and responses. Journal of Analytic Social Work, 5(4), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10529950.1998.11878772

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. http://www.crec.co.uk/docs/Trustworthypaper.pdf.

- Smyth, J. D., Dillman, D. A., Melani Christian, L., & McBride, M. (2009). Open-ended questions in web surveys: Can increasing the size of answer boxes and providing extra verbal instructions improve response quality? The Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(2), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfp029

- Spilly, S. A. (2008). Swimming upstream: Navigating the complexities of erotic transference. Smith College.

- Stirzaker, A. (2000). The taboo which silences”: Is erotic transference a help or a hindrance in the counselling relationship? Psychodynamic Counselling, 6(2), 197–213.

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research : Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Vesentini, L., Van Overmeire, R., Matthys, F., De Wachter, D., Van Puyenbroeck, H., & Bilsen, J. (2022). Intimacy in psychotherapy: An exploratory survey among therapists. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(1), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02190-7

- Welles, J. K., & Wrye, H. K. (2013). The narration of desire: Erotic transferences and countertransferences. The Analytic Press.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1956). Primary maternal preoccupation.