ABSTRACT

Finnish correctional labour facilities, which were closed institutions that operated on the basis of forced labour from the 1920s to the 1980s, were designed mainly to detain individuals perceived to be vagrant, maladjusted or alcoholic and those who were defaulters on child maintenance or the paying back of poor relief. These people had committed no crimes but were detained as a result of administrative decision-making. This article considers what grounds there were for sending people to correctional labour facilities from the perspective of the local level of the municipalities in which the individuals lived and were most likely known (including as neighbours) to the local social board members who made decisions. The main argument is that local social boards in northern municipalities primarily used correctional labour facilities to solve problems of placement originating within institutions themselves or, if outside, typically in family life. By analysing the types of cases that, in the view of social board members, were sufficiently problematic to require intervention, the article shows that everyday experiences might differ significantly from the legal grounds for detention.

Correctional labour facilities in Finland, most of them big farms fenced with barbed wire in rural areas, were designed to address various social issues: paying back poor relief or child maintenance by means of forced labour; isolating certain individuals from society and punishing them; and promoting the moral improvement of such individuals. These people had committed no crimes but were detained as a result of administrative decision-making. Correctional labour facilities had much in common with the workhouse system in various European countries.Footnote1 The Finnish history of workhouses can be traced to the fourteenth century and the history of vagrancy, as well as to the eighteenth-century spinning houses and prisons, which included sections for vagrants. By the 1880s, Finnish workhouses had ceased to exist, but similar arrangements existed in poorhouses and prisons.Footnote2 Workhouses were typically known as shelters for the destitute, who had to work on the premises. These were replaced by more humane approaches in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote3 The history of workhouses in Finland, however, resembles more closely that of German workhouses (Arbeitshäuser), which developed into penal institutions over the course of the nineteenth century.Footnote4 The term ‘correctional labour facility’, used in this study as the translation of the Finnish/Swedish term työlaitos/arbetsinrättning, is taken from the final report of the International Expert Commission (IEC) on Administrative Detention, which researched the use of administrative detention in Switzerland until 1981.Footnote5 The Swiss facilities, like those in Germany, have much in common, and their history continues until the late twentieth century. The last Finnish correctional labour facilities closed down in the 1980s.

After the 1880s, the number of institutionalised individuals in Finland increased. The inhabitants of the poorhouses included those who were required to pay back financial aid they had received, and this debt could lead to forced labour. These people lived together with children and the elderly, and despite strict discipline in the poorhouses, those who had been forced to work were at times seen as a bad influence on other residents.Footnote6 Special wards were established within poorhouses in the cities of Helsinki (1889), Turku (1898) and Tampere (1906), and these facilities were early versions of modern, twentieth-century correctional labour facilities.Footnote7 The Poor Relief Act (145/1922), which serves as the starting point of this study, advised Finnish municipalities either to found a facility or to collaborate in funding one.Footnote8 One of the goals of the Poor Relief Act was to separate different kinds of people in need of care.Footnote9 Institutional procedures exemplify the principle of differentiation, as methods and policies were adopted for categorising people according to their specific rehabilitative needs.Footnote10 Correctional labour facilities were specialised institutions intended for those who were not seen as suitable inhabitants of poorhouses (or municipal homes, as they came to be called). A person could be placed in a correctional labour facility until the debt was repaid, or until there was a guarantee that maintenance would be paid in the future, or until three years had passed.Footnote11

This article asks what the grounds were for committing people to correctional labour facilities – exploring this question at the local level of the municipalities in which the individuals lived and where they were most likely known to local social board members. Poor relief boards (köyhäinhoitolautakunta), or, as they were later called, social welfare boards (later huoltolautakunta or sosiaalilautakunta), consisted of at least four members and the chair, elected by the municipal or city council.Footnote12 In practice, the members were local residents who often knew the family histories and reputations of the people whose lives they aided and governed. The focus is on one facility, Pohjola, located in Revonlahti, a small municipality in the northern part of Finland, approximately 70 kilometres from the city of Oulu on the west coast of the Gulf of Bothnia.Footnote13 Northern Finland was a poor area in comparison to southern parts of the country, which also suffered from poverty. Between 1915 and 1945 in Finland, poverty-related problems increased in general. The period studied includes the years immediately after the Civil War of 1918 as well as those of the Great Depression of 1929–1933.Footnote14 In 1925, the population of the Province of Oulu was 398,622, of whom 37,428 lived in towns (Oulu, Raahe, Kemi, Tornio, Kajaani), and 361,194 in rural areas.Footnote15 This means that the majority of the population in the area, over 90%, was rural. The population of the area accounted for some 11% of the population of Finland.Footnote16

This article argues that the local poor relief/social welfare boards in northern municipalities used the correctional labour facility primarily to solve problems of placement. This meant institutionalising individuals on pragmatic and financial grounds to solve social problems either inside or outside institutions. Other institutions were mostly municipal homes but also district mental hospitals. The social problems outside institutions occurred both at home and in the community. The placement issues were the underlying cause, but to make decisions legally, various legal grounds were invoked, forming an intricate overall impression of administrative detention in the north. The detentions were decided on the basis of legal categories: failure to repay poor relief (1922); maladjustment in municipal homes (1922); vagrancy (1936); failure to provide child support (1922, 1948); and alcoholism (1936, shown in national correctional labour facility statistics from 1947 onwards). shows the frequency of categories in all Finnish correctional labour facilities over two decades, beginning immediately after the Vagrancy Act of 1936 and ending just before the new Act on Public Welfare Granting Support Assistance of 1956. While the categories provide some information on social problems addressed through institutionalisations, they remain abstract and portray abstract state-level ideologies, including the value-laden concept of vagrancy. By focusing on local-level decision-making, I aim to elucidate the reality behind the categories – what the local social board members, sometimes neighbours or individuals otherwise familiar to the detainees, perceived to be problems serious enough to require intervention, and how they justified detainment.

Figure 1. Detainment categories in all Finnish correctional labour facilities, 1937–1956.

The research is based primarily on archival sources from the northernmost Finnish correctional labour facility, including 1033 letters between the years 1925 and 1974. In 1925, when the Pohjola facility started operating, there were six correctional labour facilities in Finland (Helsinki, Turku, Tampere, Lammi, Punkalaidun and Revonlahti, of which the last three were new and established specifically for the purpose), accommodating a total 621 individuals. In Pohjola, there were 18 men and seven women during the first year in 1926.Footnote17 In 1925, in the Province of Oulu, a total of 3725 people were granted poor relief, indicating that the correctional labour facility was a rare solution.Footnote18 The number of detainees, however, increased in the following years, both in Pohjola and elsewhere in the country, where new facilities were also founded. Throughout its existence, the correctional labour facility system had a wider significance impossible to present in numerical form, namely deterrence.

The letters, which were addressed to the director of the correctional labour facility, were written mostly by representatives of poor relief/social welfare boards in the Province of Oulu (and the Province of Lapland after the latter was split from Oulu in 1938). I refer to anonymous data only and avoid mentioning names of smaller municipalities due to the risk of someone recognising the individual in question by reason of their place of residence. The letter archive includes administrative decisions, enquiries from local social boards to the Pohjola facility on administrative matters and copies of minutes from social board meetings sent to the facility for additional information. The main role of the letters was to serve as written documentation of the detainment decisions.

Despite their rich content, there are limitations to what can be deduced from the letters. They leave much unsaid, are not consistent and reveal only very little change over time, which is why I have mostly refrained from discussing changes in the facility system over the decades in question. I have used letters containing background information that led to the detainment decision; many of these did not provide further details. Some of the documents appended to the letters have not been preserved in the archive and some of the details were given by telephone, as is evident from references to telephone discussions. As a whole, however, the letters offer a wide set of reasons for why people were detained in a correctional labour facility in northern Finland. Although individuals were sent by reason of different legislative paragraphs that changed over time, the basic function of the correctional labour facility remained the same: it operated at the intersection of mental health care, social care, and alcohol control in particular. Alcohol was more often than not present in the problem settings, either explicitly or implicitly.

This is not a study grounded in history from below – an attempt to deduce detainees’ agency from the documentation provided by local-level decision-makers. Instead, my perspective can be characterised as history from the middle. It differs just as much from the history of marginalised groups as it does from the top-down perspective of politicians and legislators. State-level analysis of social policy is abstract. For example, Roddy Nilsson characterises how a larger strategy in solving alcohol-related social problems in Sweden was to prevent certain individuals from contaminating the social body.Footnote19 The local level presents itself as less ideological, although it simultaneously served these ideologies. Social board members, as ordinary citizens, can hardly be described as privileged wielders of power with strong political agendas. Instead of focusing on the improvement of society or protecting the social body, the officials focused on families – people they often knew personally – and the management of facilities. Different laws were used as instruments of intervention, separation and isolation. Institutionalisation in Finland has been portrayed as a desire to control lifestyles and the refund of financial help provided. Correctional labour facilities have been seen as censors of morals.Footnote20 As this study will show, in practice, defining such censoring is much more complex as placement decisions were in most cases tied to money and the poverty of the municipalities rather than to mere morals. Most importantly, the focus is on experiences in the municipalities. Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Raisa Maria Toivo claim that experiences originate through intersubjectivity. They categorise experiences in relation to three levels: everyday experiences, experience as process, and experience as structure. The transformation of everyday experiences into shared experiences is a social process through which experiences are mediated, exchanged and approved or disapproved. When experiences are repeated, they become social structures. The analysis of intersubjectivity focuses on the negotiation and mediation of experience.Footnote21 In this study, the letters exemplify this mediation on a municipal level. The everyday experiences of families, neighbours, employees and inmates of institutions and social board members were put forward in board meetings and finally transposed to the correctional labour facility. While some of the expressions in the letters may appear stigmatising and emotional, sometimes expressing anger, loathing and frustration, they mediate the shared experiences of those whom they describe. To understand the complexity of social problems, analysis of these views is just as important as study of the voices of the marginalised. According to Katajala-Peltomaa and Toivo, researching these three levels of experience connects micro, meso and macro levels, turning the empirical detail of source material into explanations and generalisations.Footnote22 The written accounts and board decisions assigned lives to legal categories. This process contributed to the further construction of social categories but, simultaneously, dispelled not only the uniqueness of individual cases but also structural problems and regional inequalities. I aim to deconstruct these categories.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The first section focuses on the availability of social and health services and negotiations regarding the right facility for placement. The letters show that people in the north had unequal opportunities to access services in comparison to the southern parts of Finland. Although the number of institutions grew on a national level, there were fewer institutions in the north, which is why correctional labour facility placements were used as a solution to various kinds of health and social issues in the municipalities. The second section analyses descriptions of behavioural problems in municipal homes. The staff in municipal homes made complaints about individuals they felt were unsuitable for residential life alongside other, often elderly, people. Local social boards took these complaints further with the aim of ensuring decency, peace and order in municipal homes. The third section delves into social problems experienced at home and in the community, thus expanding the analysis from institutions to the private sphere. It demonstrates that the correctional labour facility system was a significant apparatus of child welfare. Fathers were punished for not supporting their children, but the facilities were also used to separate and isolate parents from their offspring.

The lack of social and health services

During the years immediately following the establishment of the northern correctional labour facility, the municipalities contacted the facility to make enquiries and to discuss the cases they were considering; this also explains why many of the earlier letters are more detailed than later ones. The letters written to the Pohjola facility director illustrate the level of public social and health care services in the north. For a long time, the Poor Relief Act was the only form of social security as there was no social insurance.Footnote23 For this reason, local social boards aimed to profit from detainees’ work in the correctional labour facility in order to recoup the costs that the detainees had caused the municipality and prevent further need for assistance.

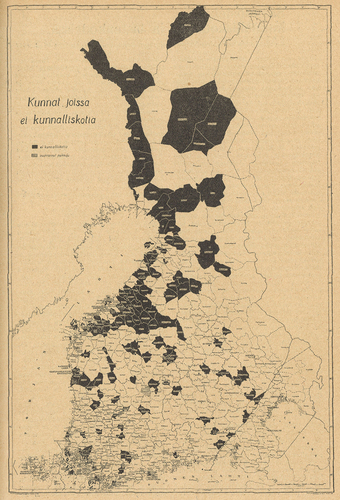

The accessibility of health services in the north was low, despite the national growth in the number of institutions in the 1920s and 1930s. On an ideological level, institutionalisation in Finland was fuelled by an interest in isolating so-called degenerates. In part, the problem was seen to be connected to the criminal law (1889), which prevented the imprisonment of certain groups of people, including the mentally ill. Besides the founding of new correctional labour facilities, institutions were established for the so-called feeble-minded, epileptics and also children.Footnote24 The ideological tone might have been in the minds of social board members, too, but their letters describe far more concrete reasons for detainment. Although the health issues of the detainees were not a legal cause for detainment, many of the cases were related to the need for institutionalisation and the lack of institutions. It was believed that people sent to correctional labour facilities were ‘mentally and physically ill’ due to their lifestyle; the avoidance of work and criminality.Footnote25 Small and poor municipalities often had no other institutions available, which underlines how low the level of provision of social and health services was at the time. For example, a woman living in a small municipality in Northern Ostrobothnia was ‘in need of institutional care’, but the poor relief board of the municipality stated that they had no municipal home or any other facility in which the woman could be placed, which is why they were considering the correctional labour facility.Footnote26 A map () from 1941 illustrates the number of municipal homes in the north of Finland from a statistical perspective; the Provinces of Oulu and Lapland are over-represented among those municipalities in the country that had no municipal homes even as late as the 1940s.Footnote27

Figure 2. Finnish municipalities lacking a municipal home in 1941 shown in black. The Pohjola facility served both the northern half of the country as well as most of the municipalities in the black cluster on the left.

The needs for institutionalisation varied and were considered differently in each municipality, following the more general ideology of individualised poor relief based on individual needs.Footnote28 The following case from 1926 of a physically disabled young man exemplifies how the correctional labour facility’s reputation was still neutral immediately after its founding, as the man in question clearly believed he could learn useful skills there – a person who had become paralysed during military service wanted to be placed in the facility. The representative of the municipality reported: ‘He is able to work a little and he would like to go there to learn crafts; he moves well and looks after himself well’.Footnote29 It is not known how the facility reacted to the enquiry. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the man’s earnings and placement had to be solved one way or another, and no other options were considered.

The letters from the early years of the facility also reveal that decisions were made based on the employment opportunities in the region, which were connected to social services. The correctional labour facility was seen as a place where detainees could do some kind of useful work as no work outside the institution was available. In the 1920s and 1930s, this made economic sense. As a letter from 1927 explained, detainment was appropriate ‘because the jobs in town are about to end and there are hardly any ways of making a living available’. The board of the municipality in question promised to re-examine the issue in the spring, when there would be new jobs and opportunities to earn a living for the detainees’ families.Footnote30 The letter exemplifies the role of the municipality in regulating unemployment caused by a lack of seasonal work.Footnote31 In some letters, there are direct references to the economic depression and descriptions of the facility as the only opportunity to make a living.Footnote32 The challenges to making a living were not solely rooted in the depression. In part the difficulties were a result of detainees’ bad reputations. Some letters stated that no one wanted to hire the detainee – an example of the transformation of ‘everyday experiences’ into ‘shared experiences’ through mediation and exchange – and some asked if a former detainee could be sent back because the employer was dissatisfied.Footnote33 Some cases can be seen as a result of stigmatisation as livelihood in rural communities was often based on complex social networks.Footnote34 Even if there was work, there was none available for a ‘certain kind of men’.Footnote35 More generally, it was believed that the quality of these men’s work was bad.Footnote36 The preceding cases are examples of the ways in which the correctional labour facility was used flexibly as a solution to financial problems, although this may also be characterised as an attempt rather than a success, because throughout its existence, the economic profitability of the correctional labour facility system was actively questioned.

More typically, the facility detainees were seen to have had problems in the context of health services. Minna Harjula has categorised four layers of rights and obligations in Finnish health citizenship. First, during the early twentieth century, the focus was on educating citizens and promoting acceptability. The second layer was associated with the era between the 1920s and 1950s, a period when the availability of health services increased. Municipal services were developed to create a nationwide public health care system. The first two layers were followed by equal and universal access to health care in the 1960s and 1970s and, later, wage-work-based and income-related health rights in the 1990s.Footnote37 These developments are evident in the letters, too, which mention changes in the level of services. The evolution of the central role of municipalities between the 1920s and 1950s is apparent; the availability of services was poorer at first in the north but became much better by the 1960s as health citizenship became more universal.

It was common to discuss everyday challenges in the health care services. For example, a person who had been treated in a tuberculosis sanatorium was discharged due to ‘bad and disruptive behaviour’ in the sanatorium and was duly reported to the social board. The municipality in Lapland wanted to know if the person could be placed in the correctional labour facility instead.Footnote38 In this particular case, the discharged patient posed a potential health threat to society, as it was generally interpreted at the time. A study on ‘asocial tuberculosis patients’ published in 1957 shows that problematic sanatorium patients were well known. The physician A.S. Härö stated that the incidence of tuberculosis was no higher among so-called ‘asocial’ patients. He presented tuberculosis as a complication of asociality, not as the reason for it. His interest in ‘asocial patients’ was based on his observation that they were more difficult to treat because they either left the sanatoria prematurely or behaved badly there. Correctional labour facility histories were common among so-called ‘asocial’ patients.Footnote39 Although former detainees often had tuberculosis, the disease is not frequently mentioned in the letters; even in the above-mentioned case, it is not clear what happened to the former patient or where he was placed. It is possible that tubercular individuals were not placed in correctional labour facilities due to the risk of infection, but there may have been secrecy regarding the matter in order to avoid weakening the deterrent effect.Footnote40 Tuberculosis was well acknowledged, and the passive form of the disease was no hindrance to detainment, but the doctor responsible for physical examinations in the Pohjola facility removed individuals with active pulmonary tuberculosis from the facility.Footnote41

Often the health-related issues discussed in the letters were related directly or indirectly to mental health services and issues. Prior to the Second World War, mental health issues were mentioned only rarely. One such case was that of a man who was sent to the Oulu district mental hospital for assessment because he was, allegedly, so ‘crotchety’.Footnote42 Before the district mental system developed and even after it was established, it was common to reserve a few places for the mentally ill in the poorhouses. The first district mental hospital was founded in 1902, and the Oulu district mental hospital in 1925.Footnote43 The negotiations between the facility and the municipalities were about borderline cases, such as that of a man who was physically healthy and able to work, but mentally ‘somewhat deficient’, meaning to those who looked after him that he worked only if forced to do so and ran away from all institutions he had been placed in. He had spent some time in a mental hospital but had been discharged because the district mental hospital physician believed he could be placed in family care or in a municipal home. As care in a mental hospital was not deemed necessary, the municipality had decided to send the person to the correctional labour facility.Footnote44 The man’s transfers from one institution to another are a typical ‘revolving door’ case.

After the Second World War, the letters referred to the Oulu district mental hospital more frequently than prior to the war, which implies that mental health issues were better recognised and that services were available. Adjusting so-called maladjusted, ‘difficult’ individuals proved to be a failed attempt in the mental health sector in northern Finland after the Second World War.Footnote45 Medicalised language became common in the municipalities, too. This was another form of categorisation beside the detainment categories, and exemplifies how first-hand experiences were converted into social processes of pathologisation. For example, a ‘difficult psychopath’ was sent to the correctional labour facility ‘for a disciplinary reason’ because of causing disturbances and insubordination. He was thought unable to cope with freedom.Footnote46 Similarly, the disease model of deviancy entered the Swedish field of social welfare, which Annika Snare characterises as ‘new faith at the ideological forefront’.Footnote47 Some detainees were also diagnosed as psychopaths in the district mental hospital.Footnote48 In some letters, the underlying medicalised views about psychopathy are more implicit, but deducible. A social welfare board in Northern Ostrobothnia presumed that one man who had complained about his ailments was suffering from jealousy and ‘intense craving for alcohol’. His mental state was deemed incurable, but nevertheless an appointment at the mental hospital was suggested if needed. The board perceived sterilisation to be a necessary procedure but did not believe it would be done, because the man objected: ‘He thinks he is oppressed and everyone else is to blame’.Footnote49 Various clues imply that the board perceived the man to be a psychopath. First, his condition was seen as incorrigible, which was one of the core definitions of psychopathy. Second, blaming others was also seen as typical of psychopaths, and third, jealousy and alcoholism could also be signs.Footnote50

Various letters referred to the district mental hospital when there was concern about a detainee’s ability to work and ‘succeed in a correctional labour facility’, as one of the letters from the medical officer of the district mental hospital stated.Footnote51 Many letters addressed the condition of the detainee. As one of the letters stated, the ‘mental and physical state’ was important in making decisions if in the near future the detainee could be placed together with peaceful municipal home residents.Footnote52 In some cases, it is hard to tell whether board members were fully aware of the mental conditions that could affect the working and daily life capacities of the detainees. The social welfare board in a municipality in the Kainuu region pronounced one man who did not work and ‘avoided looking after his family’ to be not in need of care in a mental hospital. The municipality had helped the family financially for years due to the man’s ‘loitering’, as the local people interpreted his behaviour. It was concluded that the man ‘spoke in a distorted manner’ but did not need any other kind of institutional care than what was offered in the correctional labour facility.Footnote53 The cause of his mental confusion was not discussed further and the description of his distorted speech permits the assumption that had the man been seen by a medical professional, he might have been assessed differently.

Most of the letters are short and vague, which makes the following two detailed letters from the 1960s valuable. They shed light on the challenges of assessing mental health over time to determine the right form of care, and in relation to social problems. The following case shows how difficult it could be to detect incipient mental illnesses even if there were services available to treat them. What initially manifested as mere social problems could evolve into schizophrenia in later life. A man named Pentti was discharged from the correctional labour facility after having been placed in the district mental hospital for three months. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Data were gathered for his anamnesis, following the typical protocol in the hospital.Footnote54 In the 1950s, Pentti had been divorced from his first wife. He believed that his wife had been unfaithful and imagined that all his children had different fathers. At the end of the 1950s Pentti remarried and the same accusations continued. In later years Pentti had become more closed, restless and nervous. At times he experienced auditory illusions. He drank heavily, which made him violent. In the mid-1960s, Pentti was required to go to the correctional labour facility due to his unpaid child maintenance. He was, however, unable to work, and feared illnesses, such as cancer. When he was sent to the hospital, he seemed psychotic. Pentti’s look was ‘oddly staring’ and he described his head as being ‘messed up’. In addition to his fear of cancer, Pentti was also afraid of heart failure.Footnote55 The anamnesis describes Pentti’s symptoms that were at first difficult to differentiate from mere jealousy, nervousness or alcoholism. His problems led first to divorce and then debt. It took a decade before Pentti was diagnosed with a mental illness. Although the level of detail and the time span of Pentti’s case are rare among the letters, most likely he was a typical example of a person with numerous problems but who was difficult to treat because of the way the social and mental problems were intertwined and obscure, and most probably also underdiagnosed.

The second case, Olavi, tells another kind of story, that of unpleasant encounters with the detainees. Olavi’s own letters are exceptional among the collection because they provide some indication of a detainee’s own voice. It is, however, clear that Olavi’s letters, probably sent from prison to the Pohjola facility, were not archived to save traces of his agency. On the contrary, the letters have served as proof of his intractable nature and the challenges of handling the detainees. Olavi had been sent to prison and he wrote letters to the correctional labour facility about being set free after getting out of there and before returning to the correctional labour facility. Alternatively, he insisted he should be sent to a mental hospital because he would lose his mind if moved from one facility to another. He wrote that he would refuse to work and would prefer going to prison again. His letters included a threat: he had planned to stay only a week in the correctional facility. After that he would kill himself and take someone with him. He explained that he was inspired by Tauno Pasanen, who killed four policemen in Finland in 1969.Footnote56 The case was covered extensively in the news, which is why the reference was surely clear to all concerned. The facility replied by promising a doctor’s appointment. Although Olavi’s threats were probably among the most dramatic, they were hardly unique. Many detainees, frustrated and sometimes in desperate life situations, might utter threats or refuse to co-operate, and mutual distrust was not uncommon. Olavi was convinced that his mental state was not good enough for yet another period in the correctional labour facility, but he presented his concern in a highly provocative and menacing way, which caused additional challenges for placement decisions and procedures.

Bad behaviour in municipal homes

The staff in municipal homes took part in the social process that transformed their own experiences at the workplace into a shared view of individuals’ maladjustment. Their presence in the letters from the social boards is implicit; there are no reported first-hand experiences from the municipal homes, but the complaints must have come from them. Individuals who were not deemed suitable to live in municipal homes were sent to the correctional labour facility as soon as it began operating. This, too, was enacted in the Poor Relief Act of 1922; in the 1950s, the law was replaced by the Act on Public Welfare Granting Support Assistance (116/1956). The first time that the different inhabitants (44 in total) in the Pohjola facility were categorised in the statistics – in 1927 – 23 of them were sent from municipal homes and 21 were obliged to work.Footnote57 The percentages varied each year. In comparison, some years later, in December 1935, 99 persons were sent from municipal homes, and in the country as a whole 217 were obliged to work.Footnote58 show that the legal category of maladjustment remained relatively stable over the years, diminishing in size in the post-war years.

Figure 3. Detainment categories in the Pohjola correctional labour facility, 1937–1956.

Statistics show the typical reasons for living in a poorhouse in the period 1897–1915 – that is, prior to the new law. The most common category was illnesses and accidents. Half of those who were ill were categorised as ‘feeble-minded’, and a quarter were reportedly ‘crippled and paralysed’. The second most common grounds were old age and inability to work. The number of minors lacking care were a diminishing category. Some drank too much and some were unemployed or earned insufficiently.Footnote59 It is important to note that these categories are vague; for example, feeble-mindedness might mean several very different things. As late as 1938, most of the mentally ill in Finnish municipalities were still treated in municipal homes (6300 categorised as mentally ill, 2000 as feeble-minded), whereas a significantly smaller minority (1470) were treated in mental hospitals. To a large extent this was seen as a financial matter, and the level of mental health services in the Provinces of Oulu and Lapland was characterised as the lowest in the country.Footnote60 Some of the following characterisations might thus have been symptoms of mental illnesses and intellectual disabilities.

The general arguments for unsuitability in the letters are manifold, but the most common reasons concerned difficulties in controlling the individual in the municipal home as well as the trouble that the person allegedly caused to other inhabitants: ‘would not work’, ‘behaved in such a way that he could not be kept there’, ‘could not be cared for among the old people […] due to the person’s scheming behaviour’, ‘high-handed and unruly’, ‘insolent and inappropriate’, ‘stubborn’, ‘inappropriate behaviour’, ‘drinking lifestyle and bad behaviour’, ‘not following the rules’, ‘arguing and fighting’ and ‘tricks’.Footnote61 Such recurring characterisations were seen among the staff as threats or nuisances to the peace and everyday life of the municipal home.

As was the case with some other social and health care services, correctional labour facility placements were made because municipal homes did not suit the individual in question. The reasons could be as simple as inadequate surveillance capacity in the institution. For example, in a small municipality in Northern Ostrobothnia, the only facility available was intended for elderly people, and the 19-year-old youth in question was described as an epileptic who, as a result of his illness, was also reportedly ‘slightly feeble-minded’. The young man could not live at home either because, as was described in the letter, he was always ‘on the move’, and when he went into town, he had seizures, was caught stealing and ‘committing other wickedness’.Footnote62 Another young man had escaped at the local fair and stayed there. He was apprehended by the police and 500 grams of strong spirit was confiscated from him.Footnote63 Young age was one factor in the previous examples, but old age could also be seen as a challenge. As late as 1957, it was deemed impossible to organise the care of one man in any other way than the correctional labour facility because keeping him in an old people’s home had reportedly proven impossible. Therefore, the person was not released from the facility.Footnote64

Young men were not the only ones to abscond from the municipal home. One man in a municipal home in 1928 was in the habit of wandering from one place to another and then asking for poor relief in different municipalities; it was known that most recently he had sought help in a town in Lapland. The poor relief board in his place of residence asked if he could be sent to the correctional labour facility because there was no point in placing him a municipal home due to his tendency to run away.Footnote65 Clearly the vagrant lifestyle of the man annoyed the local people, in addition to the financial burden he was seen to cause.

Some municipal home residents were considered violent. Violence was experienced as a threat to both the staff and the inmates. An excerpt from a municipal home board meeting provides a more detailed description of the violence:

and when she was asked why she bullied the young and the old and even today has beaten up [another inhabitant] and hit her in the face so that the person’s eye is badly swollen. She did not deny it but said that she cannot behave like a decent human being in this house. When she was asked if she would be pleased if she were sent to a forced labour facility, she said ‘You can put her wherever you like or shoot her, she doesn’t care’.Footnote66 She had even threatened to stab the foreman.Footnote67

The municipal home staff were hardly able to manage such daily disturbances, and it is evident from the description that the staff were appalled by the behaviour, described in detail to convince the reader of the unruly tone.

Sexual misbehaviour was a recurrent problem in municipal homes. One woman was sent to the correctional labour facility together with her eight-month-old baby due to her ‘lascivious lifestyle’, as was reported, which is why she could not be helped at home either.Footnote68 The euphemism probably referred to the woman’s active sexual misconduct, which the municipality was keen to control. Another letter about a young woman was more specific:

Could you take a 17-year-old daughter with the child to your facility, her child is about one month old. It is impossible to keep her in a municipal home because she is so friendly to men that she debauches weaker inhabitants and causes ill feeling and immorality to the partially feebleminded male inhabitants, and working men are very excited about her and she is excited about them. In five months we will have to send her to a hospital syphilis ward […].Footnote69

These municipal home cases were not categorised as vagrants, but the Vagrancy Act (204/1936) placed additional focus on vagrancy and female sexuality. The financial aid gave the municipality the right to intrude in the private lives of the women, but there was also active resistance. A woman who came to give birth to her fourth child – the three existing children were all ‘fatherless’ – was already being financially supported by the municipality and was described as acting defiantly in the municipal home. She declared she would rather be killed than behave herself, which is why the correctional labour facility was considered.Footnote70

Local social control has typically been characterised as control of women’s sexuality in particular, but in institutional settings at least, male sexuality was similarly under control.Footnote71 In the 1930s, one man seen as unable to support himself because of his ‘weakness’ and ‘feeblemindedness’ was in the care of the local poor relief. However, the man had a ‘special tendency’ – a euphemism referring to his active sex life – and the female inhabitants, some of whom were described as feeble-minded, ‘gave in to a licentious life’. It was impossible for the staff to guard the man all the time and he had already made someone pregnant. The social welfare board was wondering if the man could be diagnosed as feeble-minded, which would enable an application for sterilisation.Footnote72 Another man was believed to be responsible for fathering various children.Footnote73 Sterilisation was seen as a means to solve placement problems because it prevented unwanted pregnancies.Footnote74

Finally, a recurring problem behind many other problems was alcohol. In the municipal homes, alcohol caused various kinds of trouble, such as general unruliness, drunkenness in the presence of children, bringing in intoxicated guests and fleeing the premises.Footnote75 Correctional labour facilities were not the only facilities to address problems with alcohol, as the Alcoholics Act (60/1936) was also aimed at alcohol-induced social problems.

Family issues

Besides solving placement issues in the municipal home and other public institutions, the correctional labour facility was used to solve problems in the private sphere. Throughout its existence, the correctional labour facility system was a significant apparatus of child welfare. The legal detainment categories fail to show the extent to which the facility was a means not just of punishing but also of separating and isolating through administrative detention.

Punishment was targeted particularly at fathers who did not support their children. The Poor Relief Act stated the obligation to repay debts, which could be related to any kind of poor relief.Footnote76 Ever since the Pohjola facility was established, the municipalities were interested in sending residents who refused to financially support their children.Footnote77 This applied mostly to men, but also included women.Footnote78 Often the letters were vague and described ‘duties and responsibilities for the family’, ‘weakening sense of duty’ or ‘idle lifestyle and not providing for the family’.Footnote79 In 1948, as a result of a new law, non-support became an increasingly significant reason for being sent to a correctional labour facility.Footnote80 The law was meant as a threat and deterrent to increase the effect of maintenance liability. shows the increasing numbers of detainees due to failure to pay child support from 1949 onwards. Over time, this became the most common category of detainees in the Pohjola facility and on the national level alike (also see ).

Local communities emphasised how they tried to help the families before detainment decisions were made, as the following example from 1927 shows: ‘He has been assisted and helped in every possible way to look after his family but it seems that nothing helps, so we thought if he would get better there [at the Pohjola facility] and acquire a willingness to work’.Footnote81 The tone of the letter alludes to hopes regarding the correctional effect of the facility. Another case, from 1957, shows a similar expressed willingness to help:

We have tried everything we could but while [the person] was here, he neglected to care for his family so that in November and December 1956 the family was aided with altogether 45,000 Finnish marks. We tried payroll deduction but [the person] changed jobs and in the end, stopped working, bragging about going to a correctional labour facility. [The person] has been in care for alcoholics as well as on parole, but even they haven’t brought about any changes. [The person] should finally learn to feel that he has duties to his family and society.Footnote82

While the communities undoubtedly tried different ways to solve problematic situations, some letters might exaggerate their sincere willingness to help. Examples such as the following show clear signs of frustration and contempt: the person had failed to support his family ‘in over ten years because of his indolence, unwillingness and uncleanliness and destitution to provide the needed living and care for himself and his family’. The letter listed ‘the generous help, which has been given in the form of a dwelling, food, clothes, firewood, doctor, medicine and hospital care’, and stated that the help provided was indeed in the nature of poor relief. The municipality was utterly weary of the situation and wanted to see whether detainment in the facility might resolve the issue: ‘If the aid was still given in home circumstances, one would need a cleaner and a housekeeper, as has happened before. [The person]’s apartment has become a visiting and living place for suspicious people […]’.Footnote83 The negative emotions might have fuelled the detainment decisions and inclination to punish. It is unlikely that similar expressions would have been used of good neighbours even if there were problems in the household.

The letters reveal nothing about negotiations by local-level decision makers, although disagreements must have occasionally taken place. One case permits the assumption that decision-making could be contradictory: A social secretary from a municipality wrote a letter to the correctional labour facility about a man who, according to the secretary’s description, was pressured by the social welfare board chair and the man’s wife to return to the facility. The secretary had defied the decision and given a deposit worth 8000 Finnish marks on behalf of the man. The secretary was reportedly exasperated by the whole situation as the man was made to suffer and it was ‘forbidden to trust him’. He was assured that it would have been better for the man to repay his debts in freedom instead of being taken back to the facility.Footnote84 The secretary did not mention knowing the man personally, but this was likely. In any case, the secretary was convinced that the man should be given a chance in freedom. Perhaps the chair was more sceptical and the wife may have had a personal grudge. In general, it was well known that some men hid in order to avoid being sent to the facility.Footnote85 Some were reported to have escaped to Soviet Russia or, later, to Sweden.Footnote86 Holidays and paroles were always a risk that could lead to an escape. It was also common to try to avoid paying by deceiving the officials, which also increased the general mistrust. For example, some fathers of illegitimate children put all their property in their wife’s name to avoid having to pay.Footnote87

At times the family cases were complicated. For example, the men might have families (either pre-existing or new) who also needed support, such as a man in Lapland sent to the Pohjola facility because of failure to pay maintenance for his illegitimate child. The social welfare board of the municipality asked for the man to be released from the facility because while he had been incarcerated, his other children were suffering. The children and the wife, who all had pulmonary tuberculosis, were living in a ‘modest dwelling’, and had to be financially supported by the municipality. The wife was described to be ‘on the brink of a nervous breakdown’.Footnote88 Some women were ready to leave their older children behind, such as a woman in a village in Northern Ostrobothnia who, having separated from her husband, was cohabiting with another man with whom she had two children. The older children were in the care of the municipality, and, according to the letter, the woman had threatened to leave the younger children for the municipality to support.Footnote89 Such letters leave a lot unanswered, such as the nature of the former married life and whether or not the husband had treated his wife well. It is also impossible to know whether the woman was in earnest about her threat to leave her younger children or if it was uttered for effect when in a state of conflict with the officials.

The correctional labour facility was also considered when the social welfare board wanted to isolate the parent from the children. In one case, relinquishing custody was required before the municipality was ready to consider release: ‘The social welfare board can no longer leave these children to live among lice in the dirt as they have now learned to live in cleaner circumstances and hope to stay in their current places of care’.Footnote90 The correctional labour facility was thus used as an indirect instrument of child welfare. There are explicit statements in the letters about keeping an individual in the facility to avoid causing further trouble to the children, such as in the following reasoning: ‘because her children, who have been taken away from her in court and placed in excellent homes, do not need her’.Footnote91

Mothers or adoptive parents might be in favour of keeping biological parents detained.Footnote92 Some letters explain why. A social welfare board in Lapland wanted to know why the correctional labour facility allowed one man to go on leave from the institution, since he got drunk and went to frighten his children, cause general disturbance and waste his earnings. The board asked if the man could be kept in the institution for as long as it was legally possible.Footnote93 There was connivance between the social welfare board and the families. According to another letter, the wife of a detainee had visited the board complaining that her husband had brought other drunken men to their home where they only had one room. He had spent all his savings on alcohol, except for five Finnish marks, which he had saved for his return ticket.Footnote94

Some cases exemplify perceived social problems relating to wider community life. As historians Antti Häkkinen and Miika Tervonen point out, the attitudes of local people to vagabonds has been based not on nationality, ethnicity, language, religion and gender, nor on laws and regulations, but on the extent to which local inhabitants benefitted from them, and on their individual reputations. Diligent workers and useful saleable items were held in high regard and some of the wanderers were treated well.Footnote95 In the letters from the municipalities we find mention of some individuals who caused disapproval. Some were described with vague expressions such as ‘contempt’.Footnote96 One more detailed example is a man who was described wandering around the parish, ‘preaching the most blatant communism and mixing theology into it, causing nervousness in our weakest citizens’.Footnote97 The main issue regarding this man, however, was that the municipality was unwilling to pay for his facility upkeep as he was not a resident of the municipality.

There are hardly any letters on sex work, although the extent of sex work reached its peak in Finland in 1949. As shows, vagrancy became a common category in the Pohjola facility in the post-war years, although it was not so common across the country as a whole (also see ). Vagrancy did not necessarily mean sex work, but the latter was a common cause behind detainment for vagrancy on a national level. Some of the scarcity of references to prostitution might be explained by the fact that social boards were less involved with these so-called ‘vagrants’, who were pursued by the vice police and also by the policy to place vagrant women in facilities that specialised in them. The lack of explicit descriptions can also be at least partially explained by the difference between urban and rural areas. According to the historian Antti Häkkinen, there was sex work in the countryside, but unlike in the cities, it was not institutionalised or regulated. Instead, the benefits of sex work could be measured as indirect economic gain, and sex work was often only one profession among other work the women in the countryside did to earn their living.Footnote98 There are various cases of women whose descriptions fit that of Häkkinen. For example, a woman in a small municipality in Northern Ostrobothnia had four illegitimate children in the care of the municipality and had recently given birth to a fifth. She was described as living ‘inappropriately causing immoral life’ in her surroundings. The main concern, however, was the amount of money her children cost the municipality.Footnote99 For financial reasons, the correctional labour facility could also be a way to prevent the births of new children. In one case, a social welfare board in a municipality in Northern Ostrobothnia required that before a man could be released from the facility to support his family he should be sterilised.Footnote100 Sterilisation was thus presented as a condition for his release. Although sterilisations have attracted considerable international attention, Mattias Tydén points out that eugenics and sterilisation were marginal issues in Nordic social policy and reforms, especially in the post-war era, when universal social rights were developing.Footnote101 He characterises such social policy as ‘a history where good intentions and abuse blended’.Footnote102

The same statement also applies to the pragmatic decisions of the officials who attempted to solve social problems by detaining individuals. One man who had been detained in the correctional labour facility for almost four years wanted to know why: ‘I would like to find out […] because I have not committed any kind of crime […]’.Footnote103 The municipality explained their decision: ‘His mind is so confused that he threatened to destroy his family, who had to stay hiding in safety in the care of other people’.Footnote104 This form of mediation is worth noting, given that the first women’s shelters were only founded in 1979.Footnote105

Conclusion

The correctional labour facility system faced a lot of criticism, which culminated in various legislative changes in 1971. For example, those who were deemed unfit to live in municipal homes were no longer forced to stay in correctional labour facilities. Instead, the facilities became voluntary. The duration of detainment on the grounds of vagrancy was shortened, and the repayment of debts to society was no longer used as a justification for facility placement.Footnote106 The accessibility of health and social services in the northern half of Finland improved, although differences with the more prosperous areas of the country persisted.Footnote107 Many of the facilities were closed down in the 1970s, and the last facilities were closed in the 1980s as a consequence of multidimensional development that is beyond the scope of this study to discuss. Besides significant structural changes and improved and more prosperous social and health services, care in general operated increasingly on a voluntary basis and some of the facilities continued as institutions that specialised in the treatment of alcoholism. It was calculated that it was many times more expensive to detain a father than the amount he owed for unpaid child support. Social norms had also changed. It was more widely questioned whether correctional labour facilities could rehabilitate or ‘normalise’ individuals and whether this might be a reasonable goal in the first place, given that institutionalisation was seldom a successful form of intervention among those accused of vagrancy. Some forms of behaviour were no longer portrayed as being as harmful to society as they had been in previous decades; vagabondage, for example, was hardly a threat to social order in the 1980s in Finland.Footnote108

This article has demonstrated that local social boards in northern Finland used correctional labour facilities as a means to solve social problems. Although the decisions had legal justifications, the use of the law was at times creative as officials tried to resolve problematic situations and make their cases match the legal provisions. The Pohjola facility, the focus of this article, is a particularly good case for closer scrutiny because, in comparison to the southern part of Finland, the northern (as well as the eastern) part of the country developed more slowly, and social and health services were more scarce. The letters sent from the municipalities to the Pohjola facility show that the social problems the boards commonly faced can be divided into three broad categories: issues with mental or physical health; behaviour problems in municipal homes; and domestic issues, often related to either financial issues, violence or the protection of family members.

The letters offer a unique opportunity to study social problems as they were experienced on a local level. They show how national social and health goals failed due to the poor level of services available. The Pohjola correctional labour facility operated in place of other institutions and services that were planned at a state level but did not exist or were insufficient in the north of Finland. It was also a repository for those whose social problems were a financial or social burden on the municipalities but who could not be incarcerated in other closed institutions, such as prisons. The letters mediate how everyday experiences became a social process, as members of social boards in the municipalities recorded either their own experiences or incidences described to them. The detainees were not included directly in this intersubjective record; their deeds (while described) had excluded them from the social practice that moulded the experiences further into legal categories. I have intentionally left the complex legal concepts, such as vagrancy, out of focus. My approach resembles the study of institutional ethnographic discourse and how this is grounded in people’s experiences. The idea of conceptual practices in institutional ethnography is based on the belief that ignorance can be a benefit because concepts and theories direct attention to aspects that fit the concepts, which is why research then conforms to the conceptual frame.Footnote109 While the legal concepts used in the context of Finnish administrative detention are by no means without importance, ‘forgetting’ them for a while to study what the correctional labour facility in the north of Finland was actually used for has helped reveal the underlying motifs. In the language used in the letters, even euphemisms such as a need for ‘fatherly upbringing’, ‘need to chastise’, ‘weakening sense of duty’, or ‘educational procedure’ were used to express financial and hands-on issues that had to be solved one way or another.Footnote110 Of course, studying another, more urban facility could show the role of disapprobation more clearly, especially in the context of sex-working women. All in all, the letters studied exemplify the arbitrary nature of administrative detention, but at the same time show the advantages of administrative decision-making as flexibility to solve social problems.

Acknowledgements

Besides thanking the reviewers and editors, I express my gratitude to Minna Harjula in Tampere University and Heikki Mikkonen at the University of Helsinki for their very useful comments, and to the criminology seminar attendees, especially Johan Edman and Henrik Tham, at the Department of Criminology in Stockholm University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For recent research on workhouses in Europe, see, for example, E. Luther Valentin, Feelings of Imprisonment: Experiences from the prison workhouse at Christianshavn, 1769–1800 (Aalborg Universitet, 2022); S. Ottaway, ‘“A very bad presidente in the house”: workhouse masters, care, and discipline in the eighteenth-century workhouse’, Journal of Social History, 54, 4 (2021), 1091–119.

2 Työlaitos: Pala menneisyyttä nykypäivässä (Tampere, 1972), 1–4.

3 M. Porta and J.M. Last, ‘Workhouse’ in Porta and Last (eds), A Dictionary of Public Health(Oxford, 2018).

4 L. Frohman, Poor Relief and Welfare in Germany from the Reformation to World War I (Cambridge, 2008), 169–70; W. Ayaβ, Das Arbeitshaus Breitenau: Bettler, Landstreicher, Prostituierte, Zuhälter und Fürsorgeempfänger in der Korrektions- und Landarmenanstalt Breitenau (1874–1949) (Kassel, 1992).

5 The IEC website (uek-administrative-versorgungen.ch), accessed 21 December 2022.

6 P. Haatanen and K. Suonoja, Suuriruhtinaskunnasta hyvinvointivaltioon: Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö 75 vuotta (Helsinki, 1992), 93–95.

7 V. Piirainen, Vaivaishoidosta sosiaaliturvaan: Sosiaalihuollon ja sen työntekijäjärjestöjen historiaa Suomen itsenäisyyden ajalta (Hämeenlinna, 1974), 29.

8 Köyhäinhoitolaki (145/1922) 31§.

9 Haatanen amd Suonoja, op. cit., 95, 101.

10 A. Snare, Work, War, Prison, & Welfare: Control of the labouring poor in Sweden (Copenhagen, 1992), 210.

11 Köyhäinhoitolaki (145/1922) 57§.

12 Köyhäinhoitolaki 145/1922. 8§ 9§.

13 Revonlahti is formerly also known as the municipality of Ruukki and, since 2007, Siikajoki.

14 J. Kalela, Pulapolitiikkaa: Valtion talous- ja sosiaalipolitiikka Suomessa lamavuosina 1929–1933 (Helsinki, 1987).

15 Suomen tilastollinen vuosikirja 1927: 12. Pinta-ala ja väestö kunnittain vuosina 1900–1925 (Helsinki, 1927).

16 The population of Finland in 1925 was 3,526,359. Suomen tilastollinen vuosikirja 1927: 8. Väkiluku vuosien 1750–1925 lopussa (Helsinki, 1927).

17 Suomen virallinen tilasto: XXI. Köyhäinhoitotilasto: Suomen köyhäinhoito vuonna 1926 (Helsinki, 1928).

18 Suomen tilastollinen vuosikirja 1927: 202. Kunnallisen köyhäinhoidon elättämät ja avustamat henkilöt vuosina 1918–1925 (Helsinki, 1927).

19 For example, R. Nilsson, ‘The policing of alcoholics: power and resistance in early welfare-state Sweden’, Scandinavian Journal of History, 47, 4 (2022), 545–66, at 550, 553, 557.

20 K. Urponen, ‘Huoltoyhteiskunnasta hyvinvointivaltioon’ in J. Jaakkola, P. Pulma, M. Satka and K. Urponen, Armeliaisuus, yhteisöapu, sosiaaliturva: Suomalaisten sosiaalisen turvan historia (Helsinki, 1994), 163–227, at 180–83.

21 S. Katajala-Peltomaa and R.M. Toivo, ‘Three levels of experience’, Digital Handbook of the History of Experience, 22 October 2022, tuni.fi (accessed 20 December 2022).

22 ibid.

23 Haatanen and Suonoja, op. cit., 104.

24 M. Harjula, Terveyden jäljillä: Suomalainen terveyspolitiikka 1900-luvulla (Tampere, 2007), 46–49.

25 J. L – i, ‘Mietteitä työlaitostemme kannattavuudesta’, Huoltaja, 1 March 1936, 123–27.

26 1. February 1927 DNo 24. 69 Pohjolan päihdehuollon kuntayhtymän I arkisto. Ef: 1 Kunnilta saapuneet kirjeet 1925–1932. The National Archives of Finland, Oulu; see also a similar reference to the lack of institutions 15 July 1930 DNo 77. Ef: 1.

27 ‘Kunnat joissa ei kunnalliskotia 1941’, Huoltaja, 1 April 1941, 139.

28 Piirainen, op. cit., 77.

29 8 December 1926 DNo 104/1926. Ef: 1.

30 12 October 1927 DNo 138. Ef: 1.

31 J. Kalela, Työttömyys 1900-luvun suomalaisessa yhteiskuntapolitiikassa (Helsinki, 1989), 83–88.

32 For example, 4 June 1931 Dno 85. Ef: 1.

33 For example, 16 January 1939 DNo 18:39. Ef: 2 Kunnilta saapuneet kirjeet 1933–1949; 15 January 1953 DNo 12. Ef: 3. Kunnilta saapuneet kirjeet 1950–1956.

34 A. Häkkinen and J. Peltola, ‘Suomalaisen “alaluokan” historiaa: Köyhyys ja työttömyys Suomessa 1860–2000’ in A. Häkkinen, P. Pulma and M. Tervonen (eds), Vieraat kulkijat – tutut talot: Näkökulmia etnisyyden ja köyhyyden historiaan Suomessa (Helsinki, 2005), 39–94, at 87.

35 5 March 1936 DNo 55. Ef: 2.

36 J. L – i 1936, 123–24.

37 M. Harjula, ‘Health citizenship and health services: Finland 1900–2000’, Social History of Medicine, 29, 3 (2016), 573–89, at 580–83.

38 7 July 1931 DNo 110. Ef: 1.

39 A.S. Härö, ‘Tutkimuksia epäsosiaalisista tuberkuloosipotilaista’, Duodecim, 73, 4 (1957), 173–94.

40 This hypothesis is presented by historian Heini Hakosalo. Email correspondence with H. Hakosalo, 9 November 2022.

41 7 July 1967 DNo 287. Ef: 5 Kunnilta saapuneet kirjeet 1962–1974; 4 December 1959 DNo 676. Ef: 4 Kunnilta saapuneet kirjeet 1957–1961; H. Vainiokangas, Karsseria, kasvatusta ja huolenpitoa. 70 vuotta sosiaalihuollon arkipäivää (Jyväskylä, 1997), 54. Heikki Mikkonen has made a similar observation. See H. Mikkonen, Kurinpidosta kuntoutukseen: Uudenmaan päihdehuollon kuntayhtymän historia (Hyvinkää, 2018), 49.

42 20 September 1926 DNo 73/1926. Ef: 1.

43 P. Pietikäinen, Kipeät sielut: Hulluuden historia Suomessa (Helsinki, 2020), 89–96, 212–14.

44 7 December 1940 DNo 152:40. Ef: 2.

45 K. Parhi and P. Pietikäinen, ‘Socialising the anti-social: psychopathy, psychiatry and social engineering in Finland, 1945–1968’, Social History of Medicine, 30, 3 (2017), 637–60.

46 17 November 1949 DNo 349. Ef: 2.

47 Snare, op. cit., 215–16. For more on the role of psychopathy in the 1930s and 1940s, see A. Berg, De samhällsbesvärliga: Förhandlingar om psykopati och kverulans i 1930- och 40-talens Sverige (Stockholm, 2018).

48 For example, 24 March 1964 DNo 115. Ef: 5. The neurological/psychiatric assessment is enclosed with the letter.

49 11 July 1966 DNo 315. Ef: 5.

50 Parhi and Pietikäinen, op. cit.

51 28 October 1958 DNo 596. Ef: 4. On psychiatric evaluations, see also a letter from a municipality, 8 March 1957. Ef: 4.

52 12 August 1957 DNo 269. Ef: 4.

53 14 February 1959 DNo 306. Ef: 4.

54 A pseudonym, as are the subsequent detainee names.

55 12 October 1965 DNo 567. Ef: 5.

56 10 November 1969 No DNo. Ef: 5. There is a film (1972) based on Pasanen, entitled Kahdeksan surmanluotia. Yle Areena, https://areena.yle.fi/1-4604670 (accessed 20 December 2022).

57 Suomen virallinen tilasto: XXI. Köyhäinhoitotilasto: Suomen köyhäinhoito vuonna 1927 (Helsinki, 1929).

58 J. L – i, op. cit., 125.

59 J. Jaakkola, ‘Vaivaistalon aika vuodesta 1886 1910-luvun lopulle’ in J. Jaakkola, M. Kaarninen and P. Markkola, Koukkuniemi 1886–1986: Sata vuotta laitoshuoltoa Tampereella (Tampere, 1986), 9–64, 51.

60 R. Jalas, ‘Piirimielisairaalat jäsenkuntiensa kunnalliskotien mielisairaanhoidollisiksi neuvojiksi ja tehostajiksi’, Huoltaja, 1 December 1938, 549–53.

61 11 September 1926 DNo 71/1926. Ef: 1; 26 July 1927 DNo 92. Ef: 1; 12 February 1927 DNo 17/1927. Ef: 1; 15 December 1927 DNo 181. Ef: 1; 7 April 1930 DNo 12. Ef: 1; 24 February 1932 DNo 11. Ef: 1; 23 March 1932 DNo 42. Ef: 1; 22 June 1931 Dno 26 Ef: 1; 30 April 1935 DNo 72. Ef: 2; 2 March 1936 DNo 13. Ef: 2; Undated, received 18 February 1934 DNo 6. Ef: 2.

62 20 July 1927 DNo 88. Ef: 1.

63 18 February 1930 DNo 18. Ef: 1.

64 4 September 1957 DNo 305. Ef: 4.

65 7 February 1928 DNo 16. Ef: 1.

66 Preventive detention for so-called dangerous recidivists was also used at the time as a more severe form of punishment if the detainee did not follow the rules in a correctional labour facility.

67 1 February 1937 No 8:37. Ef: 2.

68 20 September 1927 DNo 21. Ef: 1.

69 3 May 1930 DNo 46. Ef: 1.

70 8 December 1938 DNo 11:39. Ef: 2.

71 U. Germann and L. Odier, ‘Administrative Versorgungen in der Schweiz 1930–1981’ in Unabhängige Expertenkommission (ed.), Organisierte Willkür: Administrative Versorgung in der Schweiz 1930–1981, e-book: 978-3-0340-1520-2_UEK_10A.pdf (uek-administrative-versorgungen.ch), accessed 10 October 2022, 47; J. Edman, Torken: Tvångsvården av alkoholmisbrukare i Sverige 1940–1981 (Stockholm, 2004), 440–41.

72 24 May 1937 DNo 191:37. Ef: 2.

73 21 June 1949 DNo 185. Ef: 2.

74 26 May 1941. No DNo. Ef: 2.

75 22 March 1958 No DNo. Ef: 4; 31 May 1937 DNo 22:37. Ef: 2.

76 See Köyhäinhoitolaki (145/1922) §56.

77 For example, 10 January 1927 DNo 2/1927 Ef: 1.

78 For example, 20 September 1926 DNo 73/1926. Ef: 1; 13 January 1933 DNo 7. Ef: 2.

79 29 March 1927 no Dno. Ef: 1; 29 March 1927 DNo 38/1927 Ef: 1; 28 March 1927 DNo 40. Ef: 1.

80 Elatusturvalaki (614/1948), later also Laki elatusavun turvaamisesta eräissä tapauksissa (432/1965).

81 8 March 1927 DNo 30/1927 Ef: 1.

82 27 February 1957 DNo 97. Ef: 4.

83 1 June 1938 DNo 26:38. Ef: 2.

84 15 December 1959 DNo 699. Ef: 4.

85 For example, 31 March 1959. No DNo. Ef: 4.

86 22 August 1932 DNo 108. Ef: 1; 7 July 1960 DNo 341. Ef: 4; 28 April 1964 DNo 170. Ef: 5.

87 For example, 11 April 1927 DNo 52. Ef: 1.

88 28 February 1961 DNo 126. Ef: 4.

89 7 May 1927 DNo 62. Ef: 1.

90 For example, 26 February 1938 DNo 44:38. Ef: 2.

91 5 May 1927 DNo 59. Ef: 1.

92 7 March 1950 DNo 88. Ef: 3.

93 Undated, received 8 October 1962 DNo 414. Ef: 5.

94 24 February 1966 DNo 101. Ef: 5.

95 A. Häkkinen and M. Tervonen, ‘Vähemmistöt ja köyhyys Suomessa 1800 – ja 1900-luvuilla’ in A. Häkkinen, P. Pulma and M. Tervonen (eds), Vieraat kulkijat – tutut talot: Näkökulmia etnisyyden ja köyhyyden historiaan Suomessa (Helsinki, 2005), 7–36, 28–29.

96 For example, 31 August 1926 DNo 82/1926. Ef: 1.

97 21 January 1927 KDNo 10/1927 Ef:1.

98 A. Häkkinen, Rahasta – vaan ei rakkaudesta: Prostituutio Helsingissä 1867–1939 (Helsinki, 1995), 216, 220.

99 23 November 1936 DNo 244. Ef: 2.

100 6 April 1937 DNo 147. Ef: 2.

101 On international attention, see, for example, D. Butler, ‘Eugenics scandal reveals silence of Swedish scientists’, Nature 389, 9 (1997), https://www.nature.com/articles/37848 (accessed 20 December 2022); M. Tydén, ‘The Scandinavian states: Reformed eugenics applied’ in A. Bashford and P. Levine (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics (Oxford, 2010), 369.

102 Tydén, op. cit., 373.

103 7 September 1945 No DNo Ef: 2.

104 8 October 1945 No DNo. Ef: 2.

105 T. Laine, ‘Turvakodit Suomessa’, Yhteiskuntapolitiikka, 75, 2 (2010), 194–202, at 194.

106 H. Mikkonen, ‘Valvontaa ja piikkilankaa: Työlaitokset ja poikkeavuuden kontrolli’, Hybris 2/2019. Valvontaa ja piikkilankaa, hybrislehti.net, accessed 19 December 2022.

107 T. Manninen, Pohjoisen Suomen sairaanhoidon historia (Oulu, 1998); Y. Mattila, Suuria käännekohtia vai tasaista kehitystä? Tutkimus Suomen terveydenhuollon suuntaviivoista (Tampere, 2011).

108 Työlaitos, op. cit., 56–70.

109 D. Smith and A. Griffith, Simply Institutional Ethnography: Creating a sociology for people (Toronto, 2022), 27–32.

110 13 October 1927 DNo 141. Ef: 1; 2 February 1931 DNo 13. Ef: 1; 29 March 1927 DNo 38/1927. Ef: 1; 6 June 1958 DNo 331. Ef: 4.