Abstract

This study considered the sources of facilitating experiences and strategies for thesis writing from doctoral students and graduates (N = 30). The sample was balanced between science and social science knowledge areas, with equal numbers of English as Second Language (ESL) participants in both groups. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were used to explore issues around feedback, training, cohort experiences and personal strategies for writing. Four hundred pages of transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis with the assistance of specialist software (NVivo). A generative model of academic writing development was chosen to frame the analysis. Fifteen themes emerged, three of which are discussed: supervisors’ feedback, personal organisation and ESL learning strategies. Results show the perceived benefits of individually tailored supportive feedback and the importance of the students’ resilience. Original learning strategies from ESL students that may benefit non-ESL students are also considered. The conclusions outline implications for supervisors and students across knowledge areas.

1. Introduction

Developing academic writing is a crucial skill for completing a doctorate and increasing the employability of doctoral graduates, who at job interviews have to evidence expertise in preparing papers and reports. This skill is becoming very relevant in the competitive global job market encountered after graduation: NGOs, universities, corporate and government departments all expect highly developed writing skills in research job candidates (Careers Research and Advisory Centre Citation2012). However, academic writing development is not a compulsory element across research degree programmes that often focus on subject-specific knowledge, leaving academic writing to be developed independently (Odena and Burgess Citation2012a).

This paper draws on a UK Higher Education Academy-funded study aimed at exploring postgraduate research students’ perceptions of what helps them to develop their academic writing (Odena with Burgess Citation2012b, HEA Grant Ref. FCS 664). The rationale for such an enquiry lies not just in the importance of academic writing for employability but on developing learning strategies to overcome the writing blocks reported by research students. Over 75% of doctoral students in UK universities complete their thesis later than the expected 4 years full-time or its part-time equivalent (HEFCE Citation2010). This percentage includes an estimation of the unreported students who give up before they continue to the second year and are not counted in completion rate statistics. Part of this problem may be due to the students’ underdeveloped strategies for thesis writing, leading to academic roadblocks (Chiappetta-Swanson and Watt Citation2011). We hope that offering insights in this area of enquiry can assist the development of enhanced support mechanisms for research degree students.

1.1. Studying writing development in research education

Thesis writing learning processes and how best to support them is a topic overlapping two scholarly literatures: (a) academic literacy/ies (e.g. Lillis and Scott Citation2007; Wingate Citation2012, Citation2015; Wingate and Tribble Citation2012) and (b) research/doctoral education (e.g. McAlpine and Asghar Citation2010; Harrison Citation2014). These bodies of literature are not clearly delimited: publications focussed on academic literacy at dissertation level include sections on good supervisory practices (Kamler and Thomson Citation2006; Wallace and Wray Citation2011) and scholarly works focussed on doctoral study and supervision often have sections on writing (Denholm and Evans Citation2012; Lee Citation2012).

Scholars within academic writing instruction have recently attempted to bring together work in the fields of English as an Additional Language (EAL) and academic literacies (Street Citation2010; Wingate and Tribble Citation2012; Wingate Citation2015). For example, Street (Citation2010) outlines the research shift whereby emphasis is being placed far more on understanding literacy practices ‘in context’. This socially orientated approach influenced by ethnography and referred to as New Literacy Studies contrasts with previous experimental studies some of which ‘now appear ethnocentric and culturally insensitive’ (232). The literature on both EAL and academic literacies suggests that the learning issues under consideration ‘are best understood as meaning-making in social practices rather than technical skills or language deficit’ (233). Wingate and Tribble (Citation2012) review two dominant approaches to academic writing instruction in higher education, English for Academic Purposes (EAP) and Academic Literacies, outlining how the latter ‘has become an influential model in the UK’ (481). They argue these two approaches are apparently mutually exclusive strands: (a) EAP focussing on writing for non-native speakers offered mostly to foreign students in English Language Centres; and (b) remedial writing workshops ‘where writing is taught generically as part of study skills to students of all disciplines, typically in Learning Support or Study Skills units’ (481). Both types of provision neglect that learning academic writing ‘is not a purely linguistic matter that can be fixed outside the discipline’ and that ‘reading, reasoning and writing in a specific discipline is difficult for home and international students alike’ (481). Wingate and Tribble (Citation2012) argue that separate provision ‘reserved for non-native speakers of English, or as a remedy for students who are at risk of failing, is outdated for today's student generation’ (482). They propose shared principles such as embedding writing support into disciplinary (undergraduate) teaching, which could be used for developing relevant programmes for students from all backgrounds, not just non-native speakers. In a further enquiry with management and applied linguistics students, Wingate (Citation2012) argues that discussing discipline-specific rather than generic texts is the best way for learning academic writing, which would also develop control of disciplinary discourses enabling students to take a more critical perspective.

In addition to enquiries on academic writing instruction, there is also important work on thesis writing and English as Second Language (ESL) students (e.g. Cadman Citation1997; Paltridge and Starfield Citation2007; Casanave and Li Citation2008; Chou Citation2011; Cotterall Citation2011, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Casanave Citation2002; Gao Citation2012; Paltridge and Woodrow Citation2012). For example, a number of authors have researched doctoral students of non-English-speaking backgrounds with a focus on their supervision (Ryan and Zuber-Skerrit Citation1999) and learning journeys (Starfield Citation2010; Gao Citation2012; Wang and Yang Citation2012). Starfield (Citation2010) emphasises the positive aspects of multiple literacy lives of ESL students who have become successful academics, and outlines that ‘reflective accounts of multilingual graduate students’ provide us with ‘an insight into the worlds students come from’ (138). Wang and Yang's (Citation2012) exploration of Teaching English as a Foreign Language students’ thesis development evidences the importance of the supervisors’ support and encouragement which are necessary for ESL students ‘to gain confidence in their continual pursuit of their academic goals’ (339). Cadman (Citation1997), in the context of her work with international research students in Australia, outlines that a significant cause of difficulty lies in ‘the different epistemologies in which these students have been trained and in which their identities as learners are rooted’ (1). She gives numerous examples of how difficult it is for ESL students to develop a voice as authors, in other words, how difficult it is to put forward their own original arguments. Some of her suggestions for practice are ‘to encourage students to express a personal voice in both oral and written texts about their research material even though their conventional genres may not use personal language’ (10) and to encourage self-reflection. Finally, Cotterall (Citation2013a, Citation2013b) explores the identity trajectories of six international doctoral students in Australia over a two-year period and reveals that supervisors and the students’ cultural capital are key influences on the development of scholarly identities. She concludes that ‘if all doctoral candidates are to be equally supported in their academic trajectories, participation and engagement need to be actively fostered by their supervisors’ (Citation2013a, 13).

Not all aspects revealed in the above studies are positive. Cotterall (Citation2013b) also uncovers that writing and supervision practices are common sites of tension. However, a culture of silence militates against systemic change. She outlines that, if acknowledged, ‘emotions can inspire, guide and enhance research; if ignored or suppressed, they can delay and even derail it’, suggesting that by acknowledging the emotional dimension of the students’ experiences, ‘supervisors, departments and institutions can better support their research trajectories’ (Citation2013b, 185). Paltridge and Woodrow (Citation2012) discuss instances of ‘imposter syndrome’ or the feelings of self-doubt that some postgraduate students, both native and ESL, experience in relation to their perceived competence as researchers. Other challenging areas include having to combine study, work and family commitments, which ‘requires careful negotiation to avoid one’ of them suffering in detriment of the others (96). Paltridge and Woodrow (Citation2012) suggest that supervisors’ tailored support is crucial for the students’ sense of progress and overall development, and that tutors ‘do need to expect that there will be differences, and that it is often not just a case of expectations being the same but different, but rather a case of them being very very different’ (98). Supervisors would need to keep their minds open as to how they respond to such varied needs. Motivation and resilience, important intrinsic factors, would, however, need to come from within the students. They propose that developing academic writing would involve ‘the acquisition of a repertoire of linguistic practices which are based on complex sets of discourses, identities, and values’. Research students would acquire the preferred practices of their discipline ‘learning to understand, as they write, why they are writing as they are, and what the position they have taken implies’ (Paltridge and Woodrow Citation2012, 100).

A comprehensive review of the available literature highlighted the need to approach this topic from the students’ viewpoint. There is an expanding body of publications on developing writing skills with a focus on school (Brisk Citation2014), undergraduate (Fairbairn and Winch Citation2011) and postgraduate students (e.g. Burgess, Sieminski, and Arthur Citation2006; Thomson and Walker Citation2010). These publications, particularly the ones aimed at research students, tend to frame any advice on the tutors’ viewpoint, offering recommendations on how to ‘choreograph the dissertation’ and what to do with unexpected findings (Phillips and Pugh Citation2010). However, when providing advice on academic writing, most suggestions tend to emerge from the experience of the authors as supervisors, rather than from the students’ perception of what works best for them. This paper focuses on the students’ voice, a term originally coined for school-based enquiries (e.g. Leitch et al. Citation2007). The students’ voice remains an aspect relatively underexplored in postgraduate research education. A few enquiries have focused on experiences of supervision and learning journeys (Wisker et al. Citation2010; Määttä Citation2012; McAlpine and McKinnon Citation2013). In the UK, the Postgraduate Research Experience Survey (www.heacademy.ac.uk/pres) regularly reports scores on student support, but provides limited qualitative analysis of the students’ reasons for the scores.

Within academic literacies, research scholars have focussed on a number of additional areas including: teaching to enhance student achievement (Granville and Dison Citation2005); students’ acquisition of linguistic skills needed for academic study (Fairbairn and Winch Citation2011); and doctoral and Master theses writing, in relation to specific as well as across disciplines (Owens Citation2012). This study sits within the latter area and aims to extend the knowledge available with original insights by postgraduate research students on what helps them in learning to write their theses.

2. Methodology

Participants were invited following a purposive sampling approach, using word-of-mouth and student, supervisor and alumni networks, to ensure ‘maximum variation’ across disciplines (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). The selection criteria were that participants had to be current research students or recent graduates willing to share their experiences, and their theses had to be in English (all were studying towards or had completed a doctorate within the previous eight years). No interviewees were invited from creative and performing arts as their doctorates usually combine a creative work with a written component that ‘is very different in kind from theses in more established disciplines, which have a written component only’ (Ravelli, Paltridge, and Starfield Citation2014, 2).

A ‘snow-ball’ strategy was used for simultaneous data gathering starting at the authors’ universities and continuing with invitations to others in the UK and internationally. This resulted into 22 respondents broadly from social science subjects and 15 from Technology, Engineering and Life Sciences. Participants were asked questions on effective feedback for academic writing around four themes: (a) supervisors’ feedback; (b) training; (c) cohort experiences; and (d) personal strategies for writing development (see a sample of questions in Appendix 1). Interviews were fully transcribed and to obtain a balanced sample, only 15 out of the 22 social sciences interviews were included in the analysis. Transcripts were selected following these three criteria: (i) equal number of interviews between the two broad knowledge areas; (ii) same number of ESL respondents across areas; (iii) inclusion of the longest transcripts as they appeared to contain more elaborate answers. The 30 transcripts selected for analysis ranged between 6 and 29 pages, totalling over 400 double-spaced pages. The interviewees’ area, country of study, degree status and mother tongue are included in . To maintain anonymity, pseudonyms are used throughout the article.

Table 1. List of interviewees’ knowledge area, degree status and mother tongue.

Transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis with the assistance of the specialist software NVivo. This process consisted of repeatedly reading each transcript until all relevant text was categorised and all themes were compared against each other (Odena Citation2013). A sample of categorised text was given to two independent researchers to further validate the categorisation. Fifteen final themes emerged and are listed in (and briefly defined in Appendix 2).

Table 2. Themes emerging across interviews.

3. Results and discussion

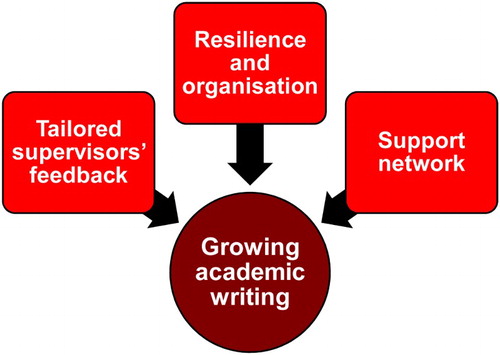

Given the qualitative approach of this investigation, the results and discussion are presented combined in one section. The experiences reported by interviewees will be contrasted with relevant literature in order to evidence how they stand and contribute to the broader areas of academic literacies and doctoral education. A generative model of academic writing development emerged from the analysis and is included in . The model contains three elements that appear to be indispensable for doctoral students’ academic writing development: (a) tailored and supportive supervisors’ feedback to scaffold independent thinking development; (b) personal resilience and organisation; and (c) a support network. This model was contrasted with the literature and further validated with higher education experts at the main conference of our national research association (Odena and Burgess Citation2013). The three elements of the model, which contain ideas from across a number of themes, are broadly defined to enable the model to work across disciplines as well as with ESL and non-ESL students.

Three out of the 15 themes are discussed in detail next due to their relevance for this paper's focus on learning: supervisors’ feedback, personal organisation and ESL learning strategies. We hope that by discussing some quotations contained in these themes, we can illustrate facilitating learning strategies for thesis writing as experienced by the students.

3.1. Supervisors’ feedback

This theme contained all the interviewees’ comments on feedback received, revealing the personalised and diverse nature of effective feedback processes. Whereas extended feedback helped best at the beginning of the doctorate, sometimes, brief suggestions were all that was needed towards the end:

I had literally 5 minutes with my supervisor … she just made a few comments and that was enough. Supervisors are great to de-clutter your brain just enough for you to be able to see the way.

As I've developed, probably imbibing general comments from my supervisors, I've seen a better picture of what I need to be attaining … Because it's about me developing my voice and being able to say ‘actually, no, this is my argument’.

[He] always reflected my questions back, he never told me the answer. And then towards the end I became quite argumentative with almost everything he said and it was at that point when he said ‘We're done because now you can argue with me … you're there, you're doctoral.’

I had originally undertaken my first degree [distance learning, and was] provided with all the learning materials required. This meant I did not have the necessary academic skills to search for my own information. My supervisors helped me to ‘filter’ relevant information and steered me in the right direction.

I needed to learn the specific skills required for scientific writing. One-on-one discussions … and feedback on documents which I had written was incredibly useful.

No particular supervisory structure or type of feedback seemed to be favoured across respondents. Instead, different strategies worked depending on the students’ needs and backgrounds. Some interviewees favoured written feedback and track changes on their drafts: ‘you can visit and revisit it many times’ (Barak, 3rd year ESL PhD candidate). Other respondents preferred oral feedback: ‘I enjoyed it when my principal supervisor sat down and connected, had an interaction. I found that much more useful than pencil written on a paper’ (Jenny, EdD graduate). Overall, both oral and written feedbacks were deemed necessary at different points of the thesis writing process: ‘sometimes it's helpful to talk about it and actually hearing it rather than writing it … it forces you to think differently about how to say things’ (Kate, 4th year PhD candidate).

Some participants liked meetings to be led by their supervisors while others preferred a loose structure shaped by their own needs and agenda. For example, Tanya, who sent her literature review to a journal three months after starting her PhD, outlined what worked best for her as follows:

When we had meetings I would say ‘this is what I want to talk about’ … I was very self-directed. But I know there are other students who are not like that, who need much more structure. It probably depends very much on the individual … I always loved writing.

Supervisors working in teams would often take up different roles when providing feedback, depending on personal style and practicalities such as location and supervision share:

My first supervisor was based [locally], read most of my writing and wrote comments. We then worked through the document together. We had many good ideas as we talked … My second was based in [another city]. I visited him 3 or 4 times a year. He gave me written comments on each chapter after my first supervisor had seen them.

[One supervisor would pose] quite detailed comments challenging whether I'd made clear the argument. The other was more direct … challenging the thinking, to make you think more about what you wanted to say.

This dual approach could be used by supervisory teams to take on apparently opposite roles in order to give stern deadlines and supportive feedback simultaneously, as in Jenny's case, who completed her thesis while being Head of School:

I remember saying to [my 2nd] at one point ‘God, I've got to get the business plan in and you're wanting my chapter?!’ And she said ‘Don't tell me about that, take two days off sick'. Because there was no way that anything else, as far as she was concerned, was more important. The Vice Chancellor of course would have disagreed. There were certain deadlines that I had to meet within the day job, but I knew there was no point in bleating to [her] … she would just go ‘This is your doctoral year, sort yourself out.’ In some ways, we were all quite frightened of her … Whereas [my 1st] was softer … He'd say ‘Don't drive yourself insane, you can do what you can do.’

Throughout their doctoral journeys, interviewees reported their supervisors’ feedback as being crucial for maintaining motivation to complete. ‘Being there’ and feeling supported was reported as one of the main motivators: ‘I am convinced that regular contact with supervisors is crucial’ (Laura, EdD graduate); ‘the most crucial thing is the supervisor. I feel that [he] is very nice and kind and really wants to help. I have a friend whose supervisor doesn't answer her emails. She is … not motivated any more to study’ (Zoe, 1st year ESL PhD candidate).

Different supervisory roles outlined by interviewees resonate with the themes discussed by Smith (Citation2009, 85–98) in relation to how research students are socialised into the academic world. These socialisation styles include: (a) ‘nurturing’, characterised by the use of facilitative coaching; (b) ‘top-down’, with more structure and formality; (c) ‘near peers’, characterised by role modelling and close affiliation with supervisors; and (d) ‘platonistic’, with little guidance on research ideas beyond exhortation to keep working and to bring back issues for discussion. Smith suggests that students in effective ‘platonic’ supervisory relationships are more enthusiastic and self-motivated, whereas students in ‘near peers’ relationships wish to emulate their supervisor's achievements.

Different supervisory styles are evidenced in our cross-disciplinary sample, with no clear patterns beyond personal characteristics and preferences. Some interviewees liked a nurturing supervisory style, with written feedback and facilitative support throughout their studies, whereas others favoured more independence from the outset. Useful feedback tailored to the students’ particular needs was aimed at supporting critical thinking skills development. Towards the end of their doctorates, there seemed to be a point where a higher level of reasoning was reached, making students ready to go through viva: ‘[my supervisor] said “We're done because now you can argue with me, you don't even want my critique … you're doctoral” (Jenny). Reaching awareness of this stage resonates with what has been described as a ‘learning leap’, understood as the students’ recognition and crossing of a conceptual and skills threshold (Wisker et al. Citation2010). As in Wisker's study, effective support reported by interviewees comprised a combination of mentoring and advising, including managing the doctorate in terms of deadlines alongside intellectual challenges, reading and networking guidance. All this support was aimed at facilitating the final viva exam and subsequent emancipation of the students as independent scholars. However, how much students benefited from the supervisors’ support appeared to be linked with their personal organisation, which is considered next.

3.2. Personal organisation

This theme included the participants’ comments on the way they organised their weekdays and weekends to work efficiently on their projects. Examples of advance planning and personal resilience abounded. Most interviewees could detail stories of producing chapters within tight deadlines, and working around job and family responsibilities. There was a sense of accomplishment in their writing experiences, as well as an understated feeling of devotion to their research that allowed them to invest time regardless of personal circumstances. This included writing early in the morning or during the night:

I would always write at night as during the day I was either at work or looking after the children. When the children were not at home, I would often go to the university at 10pm and return home about 4am … there is something about writing in the early hours.

I would get up at quarter to five so I could get some writing done in the morning … maybe four days a week.

Time management and regular writing were reported as necessary for successful completion:

It's very important to write little and write often.

Time management and planning are most important. If you don't have enough time to write, your writing will be poor.

Time set aside for writing was sometimes spent reading, thinking and doing other things to break up the writing periods, and such breaks were seen as useful: ‘I can go to the kitchen, make tea, come back, then I can do some other little things, tidy up the room. But at the same time I am thinking’ (Georgia, PhD graduate). Georgia and Kate explained that breaks in between writing periods and after producing a substantial piece of writing were needed to enhance productivity:

Three days a week I was teaching some kids privately. I always woke up seven or seven thirty and I would study until one. And then … I would go for a lesson for my students, and I would come back around seven and maybe after that, if I had any ideas I would go back and redo that. If I submitted a chapter or draft I made sure that I spent at least three days without doing anything.

Sometimes I think I sit there too long and I ought to break away because I find it's counterproductive … it's almost like my brain grinds to a halt, it's like walking through treacle … If I get too bogged down in the detail I feel like I have to walk away to give my brain a breath of fresh air … The ideal length of time would probably be between 3 and 4 hours.

The break periods between writing slots could take longer for some respondents than for others. For instance, Beth explained that she preferred ‘to have things mulling over’ in her mind ‘and then sit down for a day and write’. Some interviewees who had flexible part-time jobs such as translation and private lessons used these activities to take their minds off writing: ‘If I've got brain block then I'll do some translation just to free my mind up a bit’ (Kate); ‘I started working as a private teacher and it helped me leave the house, because I could always stay all day … and then I realised it wasn't productive’ (Georgia). Having downtime after intense work periods appears to be related with the nature of the creative process. A seminal theory of creativity by Wallas (Citation1926) illustrates four different stages in the formation of a new individual's thought: (a) preparation, or the stage during which the problem is investigated in-depth; (b) incubation, in which the individual is not consciously thinking about the problem; (c) illumination, or appearance of the ‘happy idea’; and (d) verification, in which the individual works out much the same in-depth strategies for controlling verification as those used in the preparation stage. Flexible work arrangements as well as apparently menial tasks were used as downtime by participants to rest their minds. These activities may be seen as useful tools for incubating original links between pre-existing ideas after sustained work periods. Once participants started writing a number of times weekly, they explained that work seemed to flow and writing bred the necessity for more writing:

Once I got into a grove and was able to work on it every day I got a lot of work done … I worked on my own laptop at home in the evenings and weekends.

I would set aside a couple of evenings in the week and Saturday and Sunday afternoons for studying … later I tried to have an evening off each week but found that I needed to write most days.

Sometimes I forget eating … I just keep writing, keep writing, keep writing. I come up with the main new ideas and revise. My brain is very active, so then, my working quality is very good so I can't stop. I just forget about the eating. I keep working, keep working, then exhausted. Then go to sleep.

I had teaching on 13 different subject teams at one time … I mainly had to manage my studies at evenings, weekends and annual leave.

In the last two years I worked probably three weekends out of four quite significantly but I wasn't working at that pace early on … . I literally came home [from being Head of School] on a Friday night and then worked from then until Sunday night.

In opposition to a flow state, some participants reported difficulties (rather than enjoyment) related to issues such as writing in a different language, writing blocks and distractions:

If I'm working at home for the day, I have always looked at my emails first … and you start at 8 o'clock and by half past nine you're still doing emails! … I think the discipline is preventing myself from not getting distracted.

I usually waste time and procrastinate, and I write in my blog rather than doing any meaningful productive work.

3.3. ESL learning strategies

An interesting finding that we did not expect was the particular strategies used by ESL students compared to those who had English as their first language. Writing at doctoral level requires a conscious effort from any student. For the ESL student, the challenge of writing and reviewing their work to improve both content and style was sometimes a difficult and arduous process. The efforts made to express their writing in coherent and fluent English comprise a range of strategies and ideas that could prove valuable for many other doctoral students. As Myles (Citation2002, 1) argues, ‘writing involves composing which implies the ability to tell and retell pieces of information in the form of narrative or description’. Some of the student's ideas for improving their writing are very simple while others are more complex and require input from the supervisor.

3.3.1. Gathering expressions and using words

Examples of comments from students indicated that they had to find strategies that enabled them to develop their language skills as well as their writing skills. This often meant learning new words and phrases and how they could be used in academic writing.

I had a notebook only for academic writing so I would add things on that so I developed my writing vocabulary … I divided it into sections. The first one was, if you want to write an introduction or an abstract which are the expressions that you use … . When reading articles I would underline expressions that the authors used and copied them in my writing.

When I say ‘this journal article is very easy to read’ … I try to copy the phrase … Reading is very good practice, because without input we can't output … I copy the structure as well and those of supervisor feedback.

Some ESL students tried to learn ‘rules’ for writing and then became perplexed when the phrase they had written, although grammatically correct, was not correct in terms of the phrase used.

Sometimes I ask a native English speaker why it's wrong, because I have to know the reason, why it's unnatural. Sometimes grammatical accuracy is right but the phrase is very unusual for a native.

I consult the Google and the dictionary and find them. Sometimes they are quite different, sometimes they are the same. For example, the word ‘furthermore’, ‘more over’, ‘besides’ and ‘additionally’ … I find them the same but I make it sometimes not always use ‘furthermore’, not always use ‘additionally’.

3.3.2. What should ESL courses include?

The content of courses on academic writing came in for criticism from some students. Despite such courses being planned specifically for ESL learners and writers, the role of empathy with second-language speakers, motivation and understanding of the learner perspective was often deemed missing. Negative attitudes to learning a language can also be reinforced through lack of success or failure (McGroarty Citation1996).

I think academic writing courses … should be lead by people who speak English as a second language … not by people who speak English as a first language, because they don't know what it feels like writing English as a second language … You should have an understanding of how people use a second language. Not only the way people learn and the grammar and everything but the emotion, and what it feels like to receive a feedback that tells you it's crap [sic]. I think that's completely de-motivating.

3.3.3. Writing – drafting and redrafting

Writing at doctoral level for ESL students brought many challenges. Some of these challenges related to the difference in the cultural context for learning and education, some related to style in the way that language is used. Being able to take a step-by-step approach to writing was also important:

Before doing any writing I make sure I have read a lot and familiarised myself with the topic and have ideas. The first step is to put my ideas on a mind map. After knowing structure I start writing each part of the text. Having my knowledge structured motivates me to write, also I like when I need to write recommendations or conclusion putting down my own ideas … [It helps] sharing writing experience with peers and figuring out one's own technique.

In Latin America it's a little more descriptive, so here you have to be very accurate with every sentence you use, be very short, but in Latin America we use very long sentences, we go around an idea. The first year it was very difficult for me to understand what was the level required … . It took me a lot of reading, a lot of feedback, long sessions of supervision, long sessions of reviewing my own writing to understand what was expected from me. At the beginning I just read, read, read a lot and tried to understand every little idea in a book … so then you start realising that it's more important to grasp the main idea.

Writing also boosted their language skills.

They needed to develop clarity in grammar.

Some supervisors led them to believe that content and ideas were more important than writing.

Students were not always clear what was being asked of them by their supervisors.

When not writing in their own language some felt that the quality of what they were capable of was reduced by 50%.

Writing was often painfully slow.

3.3.4. Supervisor input

ESL students developed many strategies of their own, but the role of the supervisor in their writing development seemed particularly significant. These accounts would concur with previous studies that evidence the importance of the supervisors’ encouragement for ESL students to gain confidence in their writing development (e.g. Wang and Yang Citation2012). The students appreciated the time that some supervisors took to assist them with eradicating mistakes in grammar and use of expressions as well as the intellectual content of the thesis – however, this type of assistance was not uniform across all supervisors. The cultural background of some students who had been taught to write to please their teachers and tutors made it problematic for some ESL students to develop a level of criticality in their work when writing about different authors’ texts:

My supervisor is so good that she also gives me feedback about language issues … I might put English mistakes, and she corrects. Not all supervisors give this kind of feedback, which is crucial for us.

She said you have to be very argumentative and she's very clear, she tells me this is how. But the problem may be … we call it internal noise when we talk to each other as Africans. We have a lot of internal noise! [Laughter] Even when we are writing we are writing to please because that's how we've been trained.

4. Conclusions

This enquiry builds on previous studies on academic literacy and doctoral education, supporting previously found supervisory patterns and styles, and extends this area of knowledge by evidencing the salience of personal characteristics and preferences. A continuum of supervisory approaches is used in the different phases of a doctorate, starting with enculturation, followed by critical thinking growth, emancipation and relationship development after completion (e.g. Lee Citation2012). Students and graduates interviewed reported facilitating experiences and strategies that can be located along this continuum. Effective supervisors of ESL and non-ESL students were reported to actively encourage and guide initial writing, supporting the co-construction of a scholarly identity. Other authors have suggested that this support is particularly relevant for the development of ESL students’ voices as authors (e.g. Cadman Citation1997; Wang and Yang Citation2012). Towards the end of the doctoral learning journeys, supervisors embraced an emancipator approach in which they wanted the students to find their own research voice and writing style. Arguably, many of the experiences reported were positive due to the self-selected nature of our sample: students facing tensions in their supervisory processes (Cotterall Citation2013b), ‘imposter syndrome’ (Paltridge and Woodrow Citation2012), or any other negative experience at the time of being invited to our study of ‘doctoral writing for timely completion’ may have declined participation.

Facilitating strategies reported by ESL students are likely to be of interest to non-ESL students, as well as graduates in the early stages of their academic careers.Footnote1 For example, organising ideas and creating a mind map and being clear about the structure of the writing before starting to write. The explanation of one ESL student about needing to understand how ‘ideas are glued together’ and using accessible language would also be relevant to all. These findings concur with the need outlined by Wingate (Citation2015) and Wingate and Tribble (Citation2012) to develop an approach to teaching doctoral writing that considers the complexities of academic writing as well as the diverse backgrounds of national and international students, ‘to bring about a feasible, appropriate and inclusive mainstream writing pedagogy’ in universities (Wingate and Tribble Citation2012, 492). However, a number of experiences described by the ESL students do indicate difficulties and issues that require particular attention from supervisors and higher education institutions, such as the facilitation of support networks for ESL students, many of whom are working not just in a different language, but within a new sociocultural environment away from their families. The provision of courses on academic writing, while recognised as helpful, also raised some issues to do with length of study, timing of the course and the knowledge and cultural background of the course tutor. A future study could focus on students who were not so successful in their strategies and had poor experiences at university to find out, from their perspective, what had hindered or delayed the development of their writing and learning about writing.

Considering the above tools and strategies in doctoral programmes may be of benefit to students who will be investing a great deal of time learning ‘new ways with words’ as they enter the discursive practices of their disciplines (Kamler and Thomson Citation2006). Academic writing learning is not a compulsory element across doctoral education, which often implicitly assumes that such learning will develop unaided. But for research students, particularly those with prior work or knowledge different from their chosen doctorates, there will be the need for subtle leading into the academic expectations of the new discipline by supervisors, who would need to actively foster their supervisees’ participation and engagement (Cotterall Citation2013a).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to interviewees for their time and to the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. These strategies are also relevant for developing papers during the doctoral journey (e.g. Veloso and Carvalho Citation2012; Nafisi Citation2013) and through the graduates’ early careers (e.g. Odena and Welch Citation2007, Citation2009; Esteve-Faubel, Stephens, and Molina Valero Citation2013; Garvis Citation2013; Johansson Citation2013; Oakland, MacDonald, and Flowers Citation2013; Partti and Westerlund Citation2013).

References

- Brisk, M. E. 2014. Engaging Students in Academic Literacies. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Burgess, H., S. Sieminski, and L. Arthur. 2006. Achieving Your Doctorate in Education. London: Sage.

- Cadman, K. 1997. “Thesis Writing For International Students: A Question of Identity?” English for Specific Purposes 16 (1): 3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0889-4906(96)00029-4

- Careers Research and Advisory Centre. 2012. Researcher Development Framework. www.vitae.ac.uk

- Casanave, C. P. 2002. Writing Games. Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum.

- Casanave, C. P., and X. Li, eds. 2008. Learning the Literacy Practices of Graduate School. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Chiappetta-Swanson, C., and S. Watt. 2011. Good Practice in the Supervision and Mentoring of Postgraduate Students. Hamilton, Canada: McMaster University.

- Chou, L. 2011. “An Investigation of Taiwanese Doctoral Students’ Academic Writing at a U.S. University.” Higher Education Studies 1 (2): 47–60. doi: 10.5539/hes.v1n2p47

- Cotterall, S. 2011. “Doctoral Students’ Writing: Where's the Pedagogy?” Teaching in Higher Education 16 (4): 413–25. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2011.560381

- Cotterall, S. 2013a. “The Rich Get Richer: International Doctoral Candidates and Scholarly Identity.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International. doi:10.1080/147032297.2013.839124.

- Cotterall, S. 2013b. “More than Just a Brain: Emotions and the Doctoral Experience.” Higher Education Research & Development 32 (2): 174–87. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.680017

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1996. Creativity. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- Denholm, C., and T. Evans, eds. 2012. Doctorates Downunder. 2nd ed. Camberwell: ACER.

- Esteve-Faubel, J.-M., J. Stephens, and M. Á. Molina Valero. 2013. “A Quantitative Assessment of Students’ Experiences of Studying Music: A Spanish Perspective on the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS).” British Journal of Music Education 30 (1): 59–84. doi: 10.1017/S0265051712000071

- Fairbairn, G., and Ch. Winch. 2011. Reading, Writing and Reasoning. 3rd ed. Maidenhead: OU.

- Gao, L. 2012. “Investigating ESL Graduate Students’ Intercultural Experiences of Academic English Writing: A First Person Narration of a Streamlined Qualitative Study Process.” The Qualitative Report 17 (24): 1–25.

- Garvis, S. 2013. “Beginning Generalist Teacher Self-Efficacy For Music Compared With Maths and English.” British Journal of Music Education 30 (1): 85–101. doi: 10.1017/S0265051712000411

- Granville, S., and L. Dison. 2005. “Thinking about Thinking: Integrating Self Reflection into an Academic Literacy Course.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 4 (2): 99–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2004.07.009

- Harrison, S., ed. 2014. Research and Research Education in Music Performance and Pedagogy. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Higher Education Funding Council for England. 2010. Research Degree Qualification Rates. HEFCE July 2010/21. www.hefce.ac.uk

- Johansson, K. 2013. “Undergraduate Students’ Ownership of Musical Learning: Obstacles and Options in One-To-One Teaching.” British Journal of Music Education 30 (2): 277–95. doi: 10.1017/S0265051713000120

- Kamler, B., and B. Thomson. 2006. Helping Doctoral Students Write. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lee, A. 2012. Successful Research Supervision. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Leitch, R., J. Gardner, S. Mitchell, L. Lundy, O. Odena, D. Galanouli, and P. Clough. 2007. “Consulting Pupils in Assessment for Learning Classrooms: The Twists and Turns of Working with Students as Co-Researchers.” Educational Action Research 15 (3): 459–78. doi: 10.1080/09650790701514887

- Lillis, T., and M. Scott. 2007. “Defining Academic Literacies Research: Issues of Epistemology, Ideology and Strategy.” Journal of Applied Linguistics 4 (1): 5–32.

- Lincoln, Y., and E. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Enquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Määttä, K., ed. 2012. Obsessed with the Doctoral Theses. Rotterdam: Sense.

- McAlpine, L., and A. Asghar. 2010. “Enhancing Academic Climate: Doctoral Students as their Own Developers.” International Journal for Academic Development 15 (2): 167–78. doi: 10.1080/13601441003738392

- McAlpine, L., and M. McKinnon. 2013. “Supervision – The Most Variable of Variables: Student Perspectives.” Studies in Continuing Education 35 (3): 265–80. doi: 10.1080/0158037X.2012.746227

- McGroarty, M. 1996. “Language Attitudes, Motivation and Standards.” In Sociolinguistics and Language Teaching, edited by S. McKay and N. Hornberger, 3–46. New York, NY: CUP.

- Myles, J. 2002. “Second Language Writing and Research: The Writing Process and Error Analysis in Student Texts.” TESL-EJ (Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language) 6 (2): 1–19.

- Nafisi, J. 2013. “Gesture and Body-Movement as Teaching and Learning Tools in the Classical Voice Lesson: A Survey into Current Practice.” British Journal of Music Education 30 (3): 347–67. doi: 10.1017/S0265051712000551

- Oakland, J., R. MacDonald, and P. Flowers. 2013. “Identity in Crisis: The Role of Work in the Formation and Renegotiation of a Musical Identity.” British Journal of Music Education 30 (2): 261–76. doi: 10.1017/S026505171300003X

- Odena, O. 2012. “Perspectives on Musical Creativity: Where Next?” In Musical Creativity, edited by O. Odena, 201–213. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Odena, O. 2013. “Using Software to Tell a Trustworthy, Convincing and Useful Story.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 16 (5): 355–72. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2012.706019

- Odena, O., and H. Burgess. 2012a. “An Exploration of Academic Writing Development Across Research Degrees: The Students’ Perspective.” Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association (BERA) Annual Conference, Manchester, September 4–6.

- Odena, O., with H. Burgess. 2012b. Enhancing Feedback for Academic Writing Across Research Degrees. Final report. TDG Individual Scheme, HEA Grant Ref. FCS 664.

- Odena, O., and H. Burgess. 2013. “Enquiring into Writing Development Across Research Degrees: A New Generative Model.” Paper at BERA Annual Conference, Brighton, September 3–5.

- Odena, O., and G. Welch. 2007. “The Influence of Teachers’ Backgrounds on their Perceptions of Musical Creativity: A Qualitative Study with Secondary School Music Teachers.” Research Studies in Music Education 28 (1): 71–81. doi: 10.1177/1321103X070280010206

- Odena, O., and G. Welch. 2009. “A Generative Model of Teachers’ Thinking on Musical Creativity.” Psychology of Music 37 (4): 416–42. doi: 10.1177/0305735608100374

- Owens, R. 2012. “Writing as a Research Tool.” In Doctorates Downunder, edited by C. Denholm and T. Evans. 2nd ed., 223–229. Camberwell: ACER.

- Paltridge, B., and S. Starfield. 2007. Thesis and Dissertation Writing in a Second Language. London: Routledge.

- Paltridge, B., and L. Woodrow. 2012. “Thesis and Dissertation Writing: Moving Beyond the Text.” In Academic Writing in a Second or Foreign Language, edited by R. Tang, 88–104. London: Continuum.

- Partti, H., and H. Westerlund. 2013. “Envisioning Collaborative Composing in Music Education: Learning and Negotiation of Meaning in Operabyyou.com.” British Journal of Music Education 30 (2): 207–222. doi: 10.1017/S0265051713000119

- Phillips, E. M., and D. S. Pugh. 2010. How to Get a PhD. 5th ed. Maidenhead: OU.

- Ravelli, L., B. Paltridge, and S. Starfield, eds. 2014. Doctoral Writing in the Creative and Performing Arts. Faringdon: Libri.

- Ryan, Y., and O. Zuber-Skerrit, eds. 1999. Supervising Postgraduates from Non-English Speaking Backgrounds. Buckingham: OU.

- Smith, N.-J. 2009. Achieving Your Professional Doctorate. Maidenhead: OU.

- Starfield, S. 2010. “Fortunate Travellers: Learning From the Multiliterate Lives of Doctoral Students.” In The Routledge Doctoral Supervisor's Companion, edited by P. Thompson and M. Walker, 138–46. London: Routledge.

- Street, B. V. 2010. “Academic Literacies: New Directions in Theory and Practice.” In The Routledge Companion to English Language Studies, edited by J. Maybin and J. Swann, 232–42. London: Routledge.

- Thomson, P., and M. Walker. 2010. The Routledge Doctoral Supervisor's Companion. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Veloso, A. L., and S. Carvalho. 2012. “Music Composition as a Way of Learning: Emotions and the Situated Self.” In Musical Creativity, edited by O. Odena, 73–91. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Wallace, M., and A. Wray. 2011. Critical Reading and Writing for Postgraduates. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Wallas, G. 1926. The Art of Thought. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Wang, X., and L. Yang. 2012. “Problems and Strategies in Learning to Write a Thesis Proposal: A Study of Six Ma Students in a TEFL Program.” Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics 35 (3): 324–41.

- Webster, P. 2012. “Towards Pedagogies of Revision: Guiding a Student's Music Composition.” In Musical Creativity, edited by O. Odena, 93–112. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Wingate, U. 2012. “Using Academic Literacies and Genre-Based Models for Academic Writing Instruction: A ‘Literacy’ Journey.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 11 (1): 26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2011.11.006

- Wingate, U. 2015. Academic Literacy and Student Diversity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Wingate, U., and C. Tribble. 2012. “The Best of Both Worlds? Towards an English for Academic Purposes/Academic Literacies Writing Pedagogy.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (4): 481–95. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2010.525630

- Wisker, G., C. Morris, M. Cheng, R. Masika, M. Warnes, V. Trafford, G. Robinson, and J. Lilly. 2010. Doctoral Learning Journeys. Final report. www.heacademy.ac.uk

Appendix 1. Example of interview questions.

Supervisors’ feedback

What type of feedback do you feel helps you better in developing your writing?

Training for academic writing development

What do you see as main skills for writing at doctoral level?

Personal strategies for academic writing development

What makes you ‘click’ in terms of writing?

What is the environment most appropriate for you in productive writing?

What do you use to help you to write?

Appendix 2. Themes from data analysis.

Tools for writing: comments on writing tools used by interviewees.

Editing processes and development: need to re-draft to improve and to start learning how to learn by themselves.

Motivation (for degree and writing): intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for studying and writing.

Ambition and personal characteristics: future ambitions and explanations about their backgrounds.

Supervisors’ feedback: comments revealing the diverse nature of feedback processes.

Support networks: including other students, staff, friends and/or family.

Personal organisation: comments on planning and using time efficiently.

Physical environment: descriptions of the physical settings preferred for productive writing.

Training on writing: comments on academic writing training received.

ESL learning strategies: comments on the particular nature of writing in a different language.

Wishes: comments on needs to further develop academic writing.

Formative experiences: experiences that appear to have impacted in later choices.

Passing the torch: comments on how they are now supervising other students.

Theses chapter production: explanations about production timelines.

Social capital: comments revealing a degree of social capital by some participants, often ESL students.