ABSTRACT

To this date, research on the interplay between organisational structure/managerial and organisational value/psychological elements which impact on educational quality is scarce and fragmented. As a consequence of a lack of knowledge in this area, institutions often address these elements in isolation, moving past integral approaches, which reinforce the organisations’ quality culture. In order to examine interrelationships between context characteristics, work-related psychological attitudes of staff and enhancement practices, a path analysis was performed on data collected from academics with teaching coordination roles. The findings highlight the paramount importance of a ‘human relation’ value orientation; this orientation influences empowerment, commitment and communication satisfaction. Rational goal values and ownership are positively related to quality enhancement practices. It is advocated that institutional policies and strategies directed at educational quality enhancement should leave discretionary space for the availing of academics’ expertise. Nurturing collaborative teaching/learning communities with explicit concern for morale, involvement and development, deserves further cultivation.

Introduction

Higher education finds itself in a turbulent era, facing challenges of massification, diversification, increased competition and the introduction of consumerist levers to enhance student choice and control over education processes (Brennan and Shah Citation2000; Naidoo, Shankar, and Veer Citation2011). These developments, along with attempts to increase effectiveness and efficiency in times when resources are under pressure, have fostered the implementation of systematic quality management approaches in Higher Education Institutes (HEI) (Harvey and Stensaker Citation2008; Schwarz and Westerheijden Citation2004). As government policies, particularly in a number of western countries, are redirected towards deregulation and to an emphasis on HEI autonomy, the significance of internal quality management – ‘all activities and processes deliberately organised by HEI to design, assure, evaluate and improve the quality of teaching and learning’ – (Kleijnen et al. Citation2014, 104) is further amplified (Harvey and Newton Citation2007; Jarvis Citation2014).

Notwithstanding its indelible place on institutional agendas, the added value of quality management in higher education is contested. Whereas various authors report on its merits, such as increased transparency on performance indicators, improvement of teaching processes, readiness for change and staff/student involvement (Cruickshank Citation2003; Kleijnen et al. Citation2014; Lillis Citation2012), others express concerns that managerial approaches mainly serve ‘control’ and ‘accountability’ purposes (Brookes and Becket Citation2007; Newton Citation2000). Quality management has been reported to generate staff resistance if it exaggerates bureaucracy, relies too heavily on a top-down implementation and strains individual autonomy (Baker et al. Citation1998; Cruickshank Citation2003). As academics closely identify with their own (teaching) discipline, the evaluation and assessment of educational quality can touch upon their sense of professionalism (Lueddeke Citation2003). The evaluation and assessment of education are potentially sensitive matters which have an impact on staff morale (Gordon Citation2002).

Against this backcloth, the concept of ‘quality culture’ has captured an increased interest of researchers and policy makers in the field of higher education. The concept implies that, in addition to structural/managerial elements, organisational values/psychological elements should be addressed in order to enhance educational quality (EUA Citation2006). A quality culture can be regarded as a specific kind of organisational culture which encompasses a shared commitment to – and responsibility for – quality, grass-roots involvement of staff and students and an adequate balance between top-down and bottom-up improvement initiatives (EUA Citation2006).

The importance of aligning quality management with the values and the identity of employees has been well-underpinned by research in business and industry settings (Irani, Beskese, and Love Citation2004; Maull, Brown, and Cliffe Citation2001; Powell Citation1995; Prajogo and McDermott Citation2005). In higher education, empirical studies have been conducted on the relationship between organisational values and their effectiveness (e.g. Cameron and Freeman Citation1991; Smart Citation2003), on organisational culture types and quality management (e.g. Berings Citation2009; Kleijnen et al. Citation2014; Trivellas and Dargenidou Citation2009) and on barriers to the implementation of quality management (e.g. Horine and Hailey Citation1995; Lomas Citation2004; Newton Citation2002). However, there is a paucity of comprehensive studies in higher education on the way in which cultural and managerial characteristics of the institutional context trigger work-related psychological attitudes of academic staff, the way these attitudes interrelate, and their impact on staff’s involvement in practices aimed at educational quality enhancement. Note that the term ‘quality enhancement practices’ is deliberately used in the remainder of this article in preference over ‘quality management’, to more specifically refer to the institutional activities and processes serving educational improvement purposes. The notion of ‘quality management’ is more often associated with control and accountability purposes (Williams Citation2016).

Attitudes towards – and behaviours of front line academics in – teaching are quintessential for educational quality and its continuous development, through staff’s involvement in quality enhancement of the existing education offered, but also (perhaps even more important) through staff’s direct engagement in the initial design of education and the execution of teaching roles (Westerheijden, Hulpiau, and Waetens Citation2007). In order to nurture a quality culture, an integral approach which enacts on both organisational values/psychological elements and structural/managerial elements is required (Ali and Musah Citation2012; Burli, Bagodi, and Kotturshettar Citation2012; Osseo-Asare, Longbottom, and Murphy Citation2005). Up to now, limited insight exists in the way these two dimensions interrelate, which causes them to be most often addressed in isolation.

This study aims to investigate the interrelationships between the most important organisational value/psychological and structural/managerial elements for quality culture development. These are represented as a configuration of internal-organisational context characteristics (value orientation, leadership and communication), work-related psychological attitudes of staff (empowerment, commitment and ownership) and quality enhancement practices (Bendermacher et al. Citation2016; EUA Citation2006, Citation2010). The research variables are operationalised in a ‘quality culture survey’. Data collected from academics with teaching coordination roles (affiliated to four different bachelor study programmes) were analysed in order to construct a path analytic model.

Conceptual framework

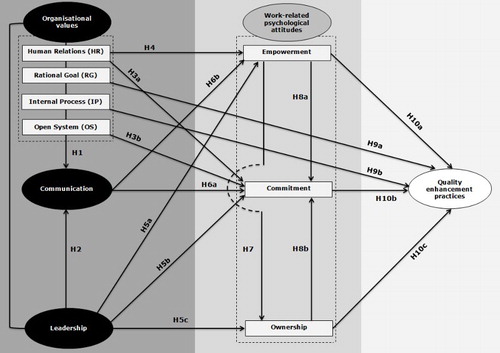

Throughout this conceptual framework, definitions of the researched variables are provided. depicts the theory-driven hypotheses (referred to in the conceptual framework between brackets/in italics; (H1–H10)).

Figure 1. Hypothesised path relationships between quality culture variables.

Note: the line connecting the ‘leadership’ and ‘organisational values’ variables reflects that a relation between these variables is expected, but that the direction of causality is unknown.

Organisational culture: a competing values approach

‘Organisational culture’ in the setting of HEI can be defined as

The collective, mutually shaping pattern of norms, values, practices, beliefs and assumptions that guide the behaviour of individuals and groups within an HEI and provide a frame of reference within which to interpret the meaning of events and actions on and off campus (Kuh and Whitt Citation1988, 28).

As research in the field of organisational culture progressed, the shared norms and values approach, as implied by this definition, appeared to have its flaws: employees are part of – and are influenced by – multiple, coinciding subcultures, which can encompass different, possibly competing values. These subcultures emerge through a shared belonging to an academic profession (research, teaching), discipline, type of institution or specific department within the institution (Austin Citation1990; Chandler Citation2011; Lomas Citation1999; Välimaa Citation1998). The competing values model, as developed by Quinn and Rohrbaugh (Citation1983), provides a framework for assessing organisational value orientation. The model consists of two dimensions: external versus internal value orientation and focus on control versus flexibility (Kleijnen et al. Citation2014). Organisations can identify with and strive for different values at the same time: to be structured and stable (‘internal process’; internal/control orientation), to be a collaborative community (‘human relation’; internal/flexible orientation), to be proactive and innovative (‘open system’; external/flexible orientation) and to be goal-oriented and efficient (‘rational goal’; external/control orientation) (Berings Citation2001; Cameron and Quinn Citation1999).

Linking organisational value orientation, leadership and communication

The value orientation within HEI forms a frame of reference for its ‘leaders’ and inspires their behaviour. Bland et al. (Citation1999, 1228) note that ‘How leaders perceive the organisation greatly affects what they believe are the best ways to influence it’. In other words, whereas leaders themselves are likely to be influenced by the organisational value orientation, they are at the same time in a position to reinforce or alter specific orientations (Dannefer, Johnston, and Krackov Citation1998). This implies the existence of a bidirectional relation (a correlation) between leadership behaviour on the one hand, and organisational value orientation on the other.

According to Bass (Citation1985), positive organisational leadership can be conceptualised as a complementary construct(ion) of ‘transactional’ and ‘transformational’ styles. Transactional leadership entails an exchange relationship between leaders (or managers) and employees (Den Hartog, Van Muijen, and Koopman Citation1997). It denotes that employees receive valued outcomes (such as wages, promotion and prestige) when they act in accordance with the wishes of higher management. Transactional leadership styles motivate employee behaviour by making clear what is expected and by providing information on the way in which performance is reimbursed. This style fits in well with stable cultures, risk avoidance, efficiency and attention for constraints in resources (Lowe, Kroeck, and Sivasubramaniam Citation1996).

Transformational leadership styles are focused on broadening employee interests, generating awareness and acceptance of the purpose of the organisation and on motivating employees to go beyond their self-interest for the good of the organisation (Den Hartog, Van Muijen, and Koopman Citation1997). This style is aimed at finding new ways of working, seeking opportunities and valuing of effectiveness over efficiency. Transformational leaders envision an attractive future and inspire staff to be committed to achieve that future. They provide meaning to staff’s work by enhancing their levels of self-efficacy, confidence, meaning and self-determination (Avolio et al. Citation2004).

Communication satisfaction in this study refers to the content of organisational messages (what is being communicated) and the ‘communication climate’ (how information is communicated). The organisational value orientation is posited to influence communication satisfaction (H1), since their experienced and preferred value orientation affects staff attitudes pertaining to the management of information and communication practices within the organisation (Brown and Starkey Citation1994). Moreover, the value orientation promoted by the organisation’s management and support departments is inherently linked to their communication strategy (Quinn et al. Citation1991). As their position in the organisational hierarchy allows leaders to acquire information needed to develop strategies and policies and act as ‘information distributors’, a positive leadership style (defined in this study as a combination of transactional and transformational leadership behaviours) is hypothesised to contribute to communication satisfaction as well (H2) (Flumerfelt and Banachowski Citation2011).

Work-related psychological attitudes: empowerment, commitment and ownership

The presence of a supportive organisational context forms a basic requirement for human resources to achieve sustainable growth and performance (Luthans and Avolio Citation2003). The organisations’ value orientation, leadership and communication can constitute such supportive contextual characteristics and are hypothesised to be positively associated with work-related psychological attitudes: ‘empowerment’, ‘affective commitment’ and ‘ownership’.

Empowerment reflects a cognitive state characterised by a sense of perceived control, competence and goal internalisation (Menon Citation1999). Affective commitment resembles an emotional attachment to, identification with and involvement in the organisation (Meyer and Allen Citation1991). Ownership refers to ‘the psychological state in which individuals feel as though the target of ownership or a piece of that target is theirs’ (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2003, 86). Ownership conceptually differs from empowerment as the former asks ‘how much do I feel this entity is mine’, while the latter asks ‘do I feel capable and intrinsically motivated in my work role’ (Van Dyne and Pierce Citation2004).

Employees have been shown to feel more affectively committed to organisations with which they share values (Lok and Crawford Citation1999; Meyer, Gagné, and Parfyonova Citation2010). Previous research in higher education settings indicates that the more policies and practices reflect concern for staff morale and development (a human relation value orientation) and encourage innovation and growth (open systems values orientation), the higher the level of affective commitment experienced by employees (Meyer, Gagné, and Parfyonova Citation2010; Ovseiko and Buchan Citation2012). The present study tests the hypothesis that human relation value orientation and open systems value orientation are positively related to teaching coordination staff’s affective commitment (H3 a, b). In addition, since a human relation value orientation aims to promote participation, involvement and staff development, it is expected to have a positive effect on staff empowerment (H4).

Leaders can provide incentives to staff, create a sense of involvement, set a vision which is in line with staff’s norms and values and offer room for staff development and autonomy (Bryman Citation2007; Meyer and Allen Citation1991). These positive attributes of transformational and transactional leadership styles are hypothesised to trigger employee empowerment, affective commitment and ownership (H5 a, b, c).

Another important internal context element relevant for organisational performance is access to information (facilitated by and optimal usage of communication channels), as this offers staff the opportunity to learn and develop themselves (Ghani, Hussin, and Jusoff Citation2009). Adequate internal communication can help reduce uncertainty and equivocality by providing staff with a thorough understanding of their work environment (Thornhill, Lewis, and Saunders Citation1996). The way in which staff experience the communication climate is hypothesised to contribute to their affective commitment to the organisation and the degree in which they feel empowered in their work (H6 a, b). Hence, adequate communication can be considered a prerequisite for staff to be able to identify with the organisations’ mission, aims and value orientation, and it is through adequate communication and information provision that staff can acquire the knowledge needed to develop a sense of empowerment.

The three work-related psychological attitudes of staff are deemed to interrelate. Since empowered staff members are entrusted with more responsibilities and have considerable opportunities to make decisions, it is expected that staff experiencing higher degrees of empowerment also experience higher degrees of ownership (H7). In addition, staff members who feel empowered and who have a sense of ownership are hypothesised to develop a stronger sense of affective commitment to the organisation (H8 a, b).

Implications for quality enhancement practices

Quality enhancement practices are associated with devoting effort to information management, communication, planning and goal setting (Reitsma Citation2003). This systematic, structured side of quality enhancement is hypothesised to fit in best with control-oriented value orientations: internal process value orientation (reflecting attempts to improve from an internal-organisational perspective) and rational goal value orientation (reflecting the aim to develop processes and practices in order to respond to evolving external demands) (H9 a, b).

By definition, empowered staff members view themselves as being able to influence their job and work environment in meaningful ways and are likely to proactively execute their responsibilities by, for instance, anticipating problems and acting independently (Spreitzer Citation1995). Empowered employees possess a certain amount of responsibility, autonomy and decisiveness. These traits of empowered staff members are considered to have a positive effect on quality enhancement practices (H10 a).

Staff members who want to belong to the organisation (referring to their sense of affective commitment) are expected to exert more effort on behalf of the organisation, compared to those who experience a need to belong to the organisation because there are high costs associated with leaving (i.e. continuance commitment) or those who feel they ought to stay, for example because the organisation has invested in them (i.e. normative commitment) (Meyer and Allen Citation1991). The affective commitment of employees has been reported to be positively correlated with outcomes relevant for the organisation, such as attendance, job satisfaction, performance and organisational citizenship behaviour (Meyer et al. Citation2002; Marchiori and Henkin Citation2004; Cooper-Hakim and Viswesvaran Citation2005). Highly affectively committed employees are willing to put extra effort into their work and have a tendency to be more concerned with its quality (Meyer and Allen Citation1991). Therefore, it is postulated that affective commitment contributes to quality enhancement practices (H10 b). The term ‘commitment’ as further used in this article refers specifically to the affective dimension of commitment.

Conventional wisdom suggests that people will take better care of, and strive to maintain and nurture what they perceive to be their own. Research by Vandewalle, Van Dyne, and Kostova (Citation1995) revealed that experienced ownership is associated with a sense of responsibility, pride and the performance of extra role behaviour; constructive work efforts that go beyond the basic required work activities. Teaching coordination staff members who consider educational courses to be ‘their own’ are expected to report higher degrees of quality enhancement practices being realised (H10 c).

Theoretical model and hypotheses

depicts the theoretical framework and direction of hypothesised causal relationships by the unidirectional arrows linking two variables. The line connecting the ‘leadership’ and ‘organisational values’ variables reflects that a relation between these variables is expected, but that the direction of causality is unknown. Leadership and organisational values are independent variables (they are not hypothesised to be influenced by the other included variables; they do not have ‘incoming’ arrows). Communication, empowerment, commitment and ownership are dependent and mediator variables (the variables have both incoming as well as outgoing arrows), while the dependence of quality enhancement practices on other variables is reflected by it only having incoming arrows. Note that for the hypothesised relation between organisational values and communication, no specific hypotheses are formulated for the four individual archetypical orientations. H1 therefore has a more general, explorative character.

H1 The organisational value orientation affects communication satisfaction.

H2 Leadership is positively related to communication satisfaction.

H3 The higher the degree of ‘human relation’ (a) and ‘open systems’(b) values experienced, the higher the degree of experienced commitment of staff.

H4 A human relation value orientation has a positive effect on staff empowerment.

H5 Leadership positively affects empowerment (a) commitment (b) and ownership (c).

H6 Communication satisfaction contributes to staff commitment (a) and empowerment (b).

H7 Empowered staff members experience higher degrees of ownership.

H8 Empowerment (a) and ownership (b) are positively related to commitment.

H9 The more staff experiences a presence of rational goal (a) and internal process values (b), the higher their report of quality enhancement practices being realised.

H10 Empowerment (a) commitment (b) and ownership (c) are positively related to quality enhancement practices.

Research design and methods

Setting and participants

The hypotheses were tested against data collected from the course coordinators of four bachelor’s programmes: Bachelor in Health Sciences, Bachelor in Biomedical Sciences, Bachelor in Medicine and Bachelor in European Public Health, at Maastricht University (NL). All programmes apply Problem-Based-Learning as core methodology, with curricula being structured in a sequence of thematic courses of several weeks. Course coordinators, together with a number of planning group members, are responsible for the quality enhancement of their respective course; they are expected to systematically work on the improvement of education, taking into account both their own experiences as well as other sources of information, e.g. quantitative and qualitative results of student evaluations and input of involved teaching staff (tutors and lecturers). Coordinators report to the study programme’s management team and are accountable for translating strategic decisions of the management team into educational practices. After explaining the background and purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and the confidentiality of responses, informed consent was obtained from all participants by means of a ‘tick-box’ statement at the start of the digital survey. The study has been approved by the ethical review board of the Dutch Association for Medical Education (NERB dossier number 530).

In total, 123 coordinators were invited to fill out the online survey, which requested staff to reflect on experiences regarding the previous run of their course. Eighty nine responses were collected (including three partly completed surveys), representing a response rate of 72%. Fifty six percent of the respondents are male. Survey respondents were active in the role of course coordinator in the specific programme for respectively <3 years (17%), 3–6 years (40%), 6–9 years (24%), 9–12 years (6%) or >12 years (14%).

Survey development

The ‘quality culture’ survey was constructed by means of combining subscales of existing, well-validated questionnaires, incorporating items of original questionnaires into new scales, and item/scale development by the authors. The final version of the survey consisted of 62 items in total. The survey is included as Appendix A.

Organisational value orientation (24 items) was measured with the ‘Organisational Culture Assessment Index’ (Cameron and Quinn Citation1999), which includes questions to explore the experienced presence of human relation values (6 items), open systems values (6 items), rational goal values (6 items) and internal process values (6 items). Leadership was measured with six items of the ‘Charismatic Leadership In Organisations’ questionnaire (De Hoogh, Koopman, and Den Hartog Citation2004).This questionnaire includes both items on transformational leadership originating from the Multifactor Leadership questionnaire as developed by Bass (Citation1985) and items on transactional leadership. Communication satisfaction (six items) was measured with items of standardised communication audits (Downs and Adrian Citation1997; Postmes, Tanis, and De Wit Citation2001). Focus was placed on communication flow ‘down the organisation’, i.e. the way course coordinators experience the communication initiated by others in the organisation (support departments and higher management) (Thornhill, Lewis, and Saunders Citation1996).

Empowerment (six items) was measured with the subscales ‘self-determination’ (reflecting autonomy over the initiation and continuation of work behaviour and processes) and ‘impact’ (the degree to which a person can influence strategic, administrative or operating outcomes at work), derived from the ‘Psychological Empowerment Scale’ (Spreitzer Citation1995). Commitment (seven items) was operationalised with the ‘Affective Commitment Scale’ as included in the ‘Organisational Commitment Questionnaire’ (Meyer, Allen, and Smith Citation1993). One additional item, measuring willingness to exert ‘extra effort’ on behalf of the organisation, was derived from the ‘Organisational Commitment Questionnaire’ (Mowday, Steers, and Porter Citation1979). Ownership (five items) was measured with the subscales ‘self-efficacy’ (one’s belief in the personal ability to accomplish a given task) and ‘accountability’ (the tendency to feel a sense of responsibility for the object of ownership) of the Psychological Ownership Questionnaire (Avey et al. Citation2009).

Quality enhancement practices (eight items) were measured with items derived from ‘Quality Management Activities Scale’, as developed by Kleijnen et al. (Citation2013), in combination with self-developed items by the authors.

Items of original questionnaires were modified in order to fit in with the specific organisational context. A pilot test was conducted among six former course coordinators to check the survey’s content validity and correct terminology. Since the original subscales and items were adapted, a principal component analysis (with oblique rotation to allow for correlations between components) was conducted to identify whether subscale items sufficiently loaded on one dimension and thus could be interpreted as one concept. Items with insufficient loadings on the variable subscale were removed. Decisions on the final (sub)scale construction were based on the consideration of multiple criteria: extracted communalities, scree plots, total variance explained and the structure matrix (item loading). Computation of Cronbach’s alpha (α) for the subscales led to acceptable results: all scales met the rule of thumb of α > .7 (Nunnally and Bernstein Citation1994). Scale reliability estimates (α) are included in . Results from the principal component analysis are available from the first author upon request.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, correlations and Alpha Reliability Estimates (on the diagonal) of quality culture variables.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were calculated to describe the population sample. Responses to all items were provided on a 5-point scale; strongly disagree (1); disagree (2); neither agree nor disagree (neutral, 3); agree (4) and strongly agree (5). Subsequently, a path analysis was carried out to test the formulated hypotheses (H1–H10). The standardised path coefficients (β) and their significance provide information on the relative strength of the hypothesised relationship between variables. Standardised coefficients can vary between −1.00 and +1.00 and indicate how many standard deviations a dependent variable will change, per standard deviation increase in its predictor variable. β-weights around .10, .25 and .40 respectively represent small, medium and large effects (Lipsey and Wilson Citation2001). Coherence between several goodness-of-fit indices was used to determine whether the theoretical model fitted the empirical data, i.e. relative chi-square statistic, normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A further elaboration on these measures and their interpretation is provided in the result section under the heading ‘model fit’.

Results

Descriptive statistics

presents the descriptive statistics, correlations (r) between variables and scale reliabilities (α) in parenthesis on the diagonal. With regard to the organisational value orientation, coordinators indicated to be ‘neutral’ to experienced control-oriented values (internal process; M = 3.16, SD = 0.54, rational goal values; M = 3.18, SD = 0.52). Flexibility oriented values; both with an internal focus (human relations; M = 2.87, SD = 0.62) and an external focus (open systems, M = 2.90, SD = 0.56) also reached a near neutral score, with mean scores being almost equivalent. When drawing to the other ‘context’ related variables, staff indicated to be neutral with regard to communication satisfaction (M = 3.05, SD = 0.73) and also tend to neither agree nor disagree with regard to the presence of (positive) leadership. (M = 3.19, SD = 0.60). The mean scores on work-related psychological attitude variables reveal that, overall, staff members who agree that they feel empowered in their role as coordinator (M = 3.99, SD = 0.65), score ‘moderate’ (between neutral and agreement) with regard to questions concerning their commitment to the study programmes (M = 3.66, SD = 0.54), and agree that they experience a sense of ownership of their course (M = 4.14, SD = 0.45). Moreover, staff members tend to agree with quality enhancement practices being enacted within their respective courses (M = 3.85, SD = 0.51).

The correlation coefficients for variables being hypothesised to interrelate (H1–H10) are presented in in bold. These coefficients provided preliminary support for most of the expected interrelations between variables included in the path model. Exemptions (nonsignificant correlations) are the hypothesised relations between leadership and empowerment (r = −.05), communication and empowerment (r = .06), the relation between leadership and ownership (r = .06) and the positive association of both internal process value orientation (r = .06) and commitment (r = .19) with quality enhancement practices. Rational goal value orientation appeared to have no correlation with leadership and communication, whereas, in line with the hypotheses, the other three value orientations were found to be correlated to leadership and communication satisfaction. Both correlations between organisational value orientation and leadership and organisational value orientation and communication satisfaction turned out to be the highest for the human relation value orientation archetype.

Interrelationships between researched variables

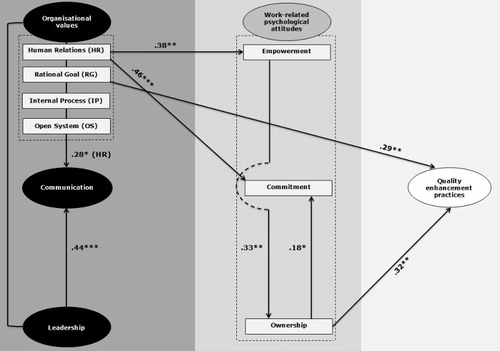

presents the path model including tests of the hypothesised relationships between variables as outlined in the conceptual framework; only significant paths are included. Note that the correlation coefficients between organisational value orientations and leadership are presented in . For a complete overview of path coefficients, standard errors and p-values, please refer to Appendix B.

Figure 2. Path model standardised coefficients of the relations between quality culture variables; *p < .05; **p < .01, *** p < .001.

Note: the relationships between variables depicted in resemble the hypothesised relationships as presented in which were found to be statistically significant; the line connecting the ‘leadership’ and ‘organisational values’ variables reflects that a relation between these variables is expected, but that the direction of causality is unknown.

With regard to H1 (the effect of value orientation on communication satisfaction) the analysis revealed that this hypothesis solely holds ground for the predicted effect of human relation value orientation on communication satisfaction (β = .28, p < .05). Hence, no relation was found between the three other organisational value orientations and communication satisfaction. The analysis also provides support for H2 (a positive relationship between leadership and communication satisfaction (β = .44, p < .001).

Both higher degrees of experienced human relation value orientation and open system value orientation were hypothesised to lead to higher degrees of commitment (H3 a, b). Whereas the analyses support this thesis for the association between human relation value orientation and commitment (β = .46, p < .001), no significant relation was identified between open systems value orientation and commitment.

Human relation value orientation was confirmed to have a positive effect on empowerment (H 4; β = .38, p = <.01). However, no empirical support could be provided for the existence of a (direct) relationship between leadership and the three included work-related psychological attitudes of empowerment, commitment and ownership (H5 a, b, c), nor for the contribution of communication satisfaction to experienced staff commitment and empowerment (H6 a, b).

When turning to the interrelations between the three work-related psychological attitudes, the analyses indicate that more empowered employees experience higher degrees of ownership (H7; β = .33, p = <.001). Only partial support was provided for H8, as the relation between empowerment and commitment was not significant (H8 a), while ownership did relate to commitment: β = .18 at p < .05 level (H8 b). These results imply that an indirect path runs from empowerment to commitment via ownership.

Rational goal and internal process value orientation were predicted antecedents of quality enhancement practices (H9). This hypothesis too was only partly confirmed: a direct medium-sized effect exists for rational goal orientations’ impact on quality enhancement practices (H9 a; β = .29, p < .01). No relation exists, however, between internal process value orientation and quality enhancement practices (H9 b). Finally, of the predicted association of work-related psychological attitudes with quality enhancement practices (H10 a, b, c) only the impact of ownership was found to be significant (β = .32, p = <.001).

The relative amount of variance of the dependent variables (communication, empowerment, commitment, ownership and quality enhancement practices) explained or accounted for by their predicator variables is represented by the squared multiple correlation (R2). R2 communication = .50, R2 empowerment = .10, R2 ownership = .11, R2 commitment = .36, R2 quality enhancement practices = .26.

Model fit

The coherence between several statistics was used to determine whether the theoretical model fitted the empirical data. The chi-square statistic tests the null hypothesis that the model adequately represents the population data. The nonsignificant Chi-square (p = .365) indicates that the null hypothesis should not be rejected (meaning that the overall fit of the model is satisfactory). It is argued that the chi-square statistic divided by the degrees of freedom is a more reliable fit index, since it compensates for sample size. A relative chi-square of 2 or less indicates a good fit (Ullman Citation2001). For the tested model Chi-square/df = 1.085. Alternative measures for fit are the NFI, the CFI and the RMSEA. A good fit is indicated by values greater than 0.90 for NFI and 0.95 and greater for CFI (Hu and Bentler Citation1999). NFI of the tested model = 0.943, CFI = 0.994. For RMSEA, a value of 0 is interpreted as an exact fit and an RMSEA of 0.05 or less indicates a close fit (Browne and Cudeck Citation1993). RMSEA of the tested model = 0.031, further reflecting an adequate fit of the model.

Discussion

In this study, hypothesised interrelationships between organisational context characteristics (value orientation, leadership and communication), work-related psychological attitudes of academics with teaching coordination roles (empowerment, commitment and ownership) and educational quality enhancement practices were tested in a path analytic model. The findings highlight the paramount importance of a ‘human relation’ value orientation within HEI, as this orientation contributes to staff empowerment and commitment, indirectly impacts on ownership (through empowerment) and has a positive effect on communication satisfaction. Moreover, out of the four archetypical organisational value orientations, the human value orientation was found to have the strongest correlation with positive leadership. Successfully shaping work-related psychological attitudes of academics is crucial, since these attitudes do not only influence ‘in role’ behaviour (acting in accordance with requirements set by the organisation), but also affect ‘extra role’ behaviour (going beyond formal requirements of a role) which is an important determinant of productivity, creativity, innovation and overall organisational performance (Van Dyne and Pierce Citation2004).

The fact that ‘rational goal’ values which emphasise planning, goal attainment, and efficiency were found to impact on the execution of quality enhancement practices, resembles the significance of the organisational structure/managerial pillar for quality culture development: organisational policies, strategies and guidelines determine to a certain degree whether evaluation and enhancement practices are being executed by staff. This study reveals, however, that in order to reinforce this structural/managerial pillar, as well as the organisational value/psychological pillar for quality culture development, the nurturing of an academic teaching/learning community characterised by collaboration, explicit concern for staff morale and involvement (i.e. reflecting a human relation value orientation) as well as the promotion of ownership, need further cultivation. Especially the implementation of longitudinal faculty development initiatives, which incorporate attention to staff’s motivations for teaching, values and professional identities, can contribute to favourable outcomes in this respect. That is, the intentional community building which coincides with comprehensive faculty development programmes has shown to impact on increased staff self-awareness, acquisition of new skills and expertise, and a higher degree of perceived institutional support for taking on responsibilities which impact on continuous educational quality enhancement (Steinert et al. Citation2016). The finding that especially the degree of ownership experienced by teaching coordinators impacts positively on the execution of quality enhancement activities implies that it will be worthwhile to increase their involvement in the design of quality evaluation and improvement measures: staff is more likely to act on quality evaluation data which they feel exemplify the key criteria of educational quality in ‘their’ domain.

Counter to the theoretical predictions, no direct relation was identified in this study between leadership and staff’s experienced empowerment, commitment and ownership. One reason for the finding that leadership and work-related psychological attitudes were not related can stem from staff’s self-views as being autonomous and competent professionals. Hence, staff’s professionalism, internal motivation and preference for an independent way of working mitigate their need for strong/directive leadership (Hall and Weaver Citation2001). Academics might need a more covert form of leadership entailing protection, support and the management of autonomy (Bryman Citation2007). A second reason for the absent relation between leadership and psychological work-related attitudes can be derived from the performed path analysis: leadership correlates to a variety of value orientations, which suggests that instead of a direct path from leadership to work-related psychological attitudes, an indirect path runs from leadership to these attitudes via the value orientation reinforced by leaders. This is in line with findings of a literature review performed by Bland et al. (Citation2000) on factors influencing successful curriculum development and organisational change in medical schools: leaders’ assertive, participative and cultural/value-influencing behaviours were found to substantially contribute to positive change outcomes, since leaders promoted collaboration, shared values in the light of the envisioned change, built trust and facilitated involvement and open communication.

It is imperative that sufficient resources (time, expertise and adequate evaluation instruments) are available in order to collect data on educational quality and to identify potential areas of improvement (Gerrity and Mahaffay Citation1998; Kottmann et al. Citation2016). While it is acknowledged that resource availability inevitably plays a role in quality enhancement practices, the present study refrained from focusing on material aspects in favour of providing insight in ways to successfully shape work-related psychological attitudes of academics. The study paves the way for developing organisational strategies for quality culture development based on empirical research on the interrelationship between organisational values/psychological elements and organisational structure/managerial elements. To our knowledge, this empirical approach to quality culture development is unique in its kind. It is advocated that institutional policies and strategies directed at educational quality enhancement should leave sufficient discretionary space for the availing of academic professionals’ expertise and the promotion of ownership, while leadership in higher education should especially be directed to the promotion of a human relation value orientation.

Limitations

It should be noted that, while the path model included many variables important for the development of a quality culture, it was only able to account for a modest proportion of variance in some variables. Hence, characteristics of the organisational context, work-related psychological attitudes and quality enhancement practices are likely to also be affected by factors outside the model (for instance resource availability). Although the path analysis technique allows for testing plausible, prespecified relations between variables, in itself it cannot distinguish whether a correlation between A and B represents a causal effect of A on B, a causal effect of B on A, mutual dependence on other variables C, D or a mixture of these (Stage, Hasani, and Amaury Citation2004). However, in this study, the adequate application of the path analysis technique and the interpretation of relationships between the researched variables were supported by a sound theoretical framework (Leppink Citation2015). Caution is warranted on the generalisability of the findings as the data collected is context specific. In countries characterised by collectivistic values, higher education staff’s behaviour is more likely to be influenced by shared norms, group interdependence and experienced obligations toward the organisation, instead of individualism, independence and the primacy of personal needs and rights, which is more typical for western cultures (Wasti Citation2003).

Suggestions for further research

The empirical insight in ways to promote quality culture development in HEI can be augmented by conducting cross-institutional studies on this theme. Moreover, qualitative research on quality culture will prove to be valuable in terms of its potential to enlarge the understanding of academic staff’s perceptions and behavioural determinants which have not been incorporated in the present study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

M. G. A. oude Egbrink http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5530-6598

References

- Ali, H. M., and M. B. Musah. 2012. “Investigation of Malaysian Higher Education Quality Culture and Workforce Performance.” Quality Assurance in Education 20 (3): 289–309. doi: 10.1108/09684881211240330

- Austin, A. E. 1990. “Faculty Cultures, Faculty Values.” New Directions for Institutional Research 1990 (68): 61–74. doi: 10.1002/ir.37019906807

- Avey, J. B., B. J. Avolio, C. D. Crossley, and F. Luthans. 2009. “Psychological Ownership: Theoretical Extensions, Measurement and Relation to Work Outcomes.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 30 (2): 173–91. doi: 10.1002/job.583

- Avolio, B. J., W. Zhu, W. Koh, and P. Bhatia. 2004. “Transformational Leadership and Organizational Commitment: Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment and Moderating Role of Structural Distance.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 25 (8): 951–68. doi: 10.1002/job.283

- Baker, G. R., S. Gelmon, L. Headrick, M. Knapp, L. Norman, D. Quinn, and D. Neuhauser. 1998. “Collaborating for Improvement in Health Professions Education.” Quality Management in Health Care 6 (2): 1–11. doi: 10.1097/00019514-199806020-00001

- Bass, B. M. 1985. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press.

- Bendermacher, G. W. G., M. G. A. Oude Egbrink, H. A. P. Wolfhagen, and D. H. J. M. Dolmans. 2016. “Unravelling Quality Culture in Higher Education: A Realist Review.” Higher Education 73 (1): 1–22.

- Berings, D. 2001. “Dealing with Competing Values as a Condition for the Development of Integral Quality Management in Higher Vocational Education in Flanders.” [Omgaan met concurrerende waarden als voorwaarde tot de ontwikkeling van integrale kwaliteitszorg in het hogescholenonderwijs in Vlaanderen.] (PhD Thesis), K.U. Leuven, EHSAL, Brussel.

- Berings, D. 2009. “Reflection on Quality Culture as a Substantial Element of Quality Management in Higher Education.” Paper presented at the fourth European quality assurance forum (EQAF) of the European university association (EUA), Copenhagen, November 19–21, 2009.

- Bland, C. J., S. Starnaman, L. Hembroff, H. Perlstadt, R. Henry, and R. Richards. 1999. “Leadership Behaviors for Succesful University-Community Collaborations to Change Curricula.” Academic Medicine 74 (11): 1227–37. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199911000-00018

- Bland, C. J., S. Starnaman, L. Wersal, L. Moorhead-Rosenberg, S. Zonia, and R. Henry. 2000. “Curricular Change in Medical Schools: How to Succeed.” Academic Medicine 75 (6): 575–94. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00006

- Brennan, J., and T. Shah. 2000. “Quality Assessment and Institutional Change: Experiences from 14 Countries.” Higher Education 40 (3): 331–49. doi: 10.1023/A:1004159425182

- Brookes, M., and N. Becket. 2007. “Quality Management in Higher Education: A Review of International Issues and Practice.” International Journal for Quality and Standards 1 (1): 1–37.

- Brown, A. D., and K. Starkey. 1994. “The Effect of Organizational Culture on Communication and Information.” Journal of Management Studies 31 (6): 807–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.1994.tb00640.x

- Browne, M. W., and R. Cudeck. 1993. “Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit.” In Testing Structural Equation Models, edited by K. A. Bollen, and J. S. Long, 136–62. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Bryman, A. 2007. “Effective Leadership in Higher Education: A Literature Review.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (6): 693–710. doi: 10.1080/03075070701685114

- Burli, S., V. Bagodi, and B. Kotturshettar. 2012. “TQM Dimensions and Their Interrelationships in ISO Certified Engineering Institutes of India.” Benchmarking: An International Journal 19 (2): 177–92. doi: 10.1108/14635771211224527

- Cameron, K. S., and S. J. Freeman. 1991. “Cultural Congruence, Strength, and Type: Relationships to Effectiveness.” Research in Organizational Change and Development 5 (1): 23–58.

- Cameron, K. S., and R. E. Quinn. 1999. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture. Based on the Competing Values Framework. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Chandler, N. 2011. “Understanding Complexity: A Multi-Perspective Model of Organizational Culture in Higher Education Institutions.” Practice and Theory in Systems of Education 6 (1): 1–10.

- Cooper-Hakim, A., and C. Viswesvaran. 2005. “The Construct of Work Commitment: Testing an Integrative Framework.” Psychological Bulletin 131 (2): 241–59. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.241

- Cruickshank, M. 2003. “Total Quality Management in the Higher Education Sector: A Literature Review from an International and Australian Perspective.” Total Quality Management and Business Excellence 14 (10): 1159–67. doi: 10.1080/1478336032000107717

- Dannefer, E. F., M. A. Johnston, and S. K. Krackov. 1998. “Communication and the Process of Educational Change.” Academic Medicine 73 (9): S16–23. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199809000-00031

- De Hoogh, A. H. B., P. L. Koopman, and D. N. Den Hartog. 2004. “The Development of the CLIO, a Questionnaire for Charismatic Leadership in Organisations.” [De ontwikkeling van de CLIO, een vragenlijst voor charismatisch leiderschap in organisaties.]Gedrag & Maatschappij 17 (5): 354–81.

- Den Hartog, D. N., J. J. Van Muijen, and P. L. Koopman. 1997. “Transactional Versus Transformational Leadership: An Analysis of the MLQ.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 70 (1): 19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00628.x

- Downs, C., and A. Adrian. 1997. Communication Audits. Lawrence, KS: Communication Management.

- European University Association. 2006. Quality Culture in European Universities: A Bottom-up Approach. Report on the Three Rounds of the Quality Culture Project 2002–2006. Brussels: EUA.

- European University Association. 2010. Examining Quality Culture Part I: Quality Assurance Processes in Higher Education Institutions. Brussels: EUA.

- Flumerfelt, S., and M. Banachowski. 2011. “Understanding Leadership Paradigms for Improvement in Higher Education.” Quality Assurance in Education 19 (3): 224–47. doi: 10.1108/09684881111158045

- Gerrity, M. S., and J. Mahaffay. 1998. “Evaluating Change in Medical School Curricula; how did we Know Where We Were Going.” Academic Medicine 73 (9): S55–59. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199809000-00036

- Ghani, N. A. A., T. A. B. Hussin, and K. Jusoff. 2009. “Antecedents of Psychological Empowerment in the Malaysian Private Higher Education Institutions.” International Education Studies 2 (3): 161–65. doi: 10.5539/ies.v2n3p161

- Gordon, G. 2002. “The Roles of Leadership and Ownership in Building an Effective Quality Culture.” Quality in Higher Education 8 (1): 97–106. doi: 10.1080/13538320220127498

- Hall, P., and L. Weaver. 2001. “Interdisciplinary Education and Teamwork: A Long and Winding Road.” Medical Education 35 (9): 867–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00919.x

- Harvey, L. E. E., and J. Newton. 2007. “Transforming Quality Evaluation: Moving on.” In Quality Assurance in Higher Education. Trends in Regulation, Translation and Transformation, edited by D. F. Westerheijden, B. Stensaker, and M. J. Rosa, 225–45. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Harvey, L. E. E., and B. Stensaker. 2008. “Quality Culture: Understandings, Boundaries and Linkages.” European Journal of Education 43 (4): 427–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3435.2008.00367.x

- Horine, J. E., and W. A. Hailey. 1995. “Challenges to Successful Quality Management Implementation in Higher Education Institutions.” Innovative Higher Education 20 (1): 7–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01228324

- Hu, L., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. “Cut Off Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

- Irani, Z., A. Beskese, and P. E. D. Love. 2004. “Total Quality Management and Corporate Culture: Constructs of Organisational Excellence.” Technovation 24 (8): 643–50. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4972(02)00128-1

- Jarvis, D. S. L. 2014. “Regulating Higher Education: Quality Assurance and Neo-Liberal Managerialism in Higher Education.” Policy & Society: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Policy Research 33 (3): 155–66. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2014.09.005

- Kleijnen, J., D. Dolmans, J. Willems, and J. Van Hout. 2013. “Teachers’ Conceptions of Quality and Organisational Values in Higher Education: Compliance or Enhancement?” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (2): 152–66. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2011.611590

- Kleijnen, J., D. Dolmans, J. Willems, and H. Van Hout. 2014. “Effective Quality Management Requires a Systematic Approach and a Flexible Organisational Culture: A Qualitative Study among Academic Staff.” Quality in Higher Education 20 (1): 103–26. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2014.889514

- Kottmann, A., J., Huisman, L., Brockerhoff., L. Cremonini, and J. Mampaey. 2016. How Can One Create a Culture for Quality Enhancement?. CHEPS, CHEGG.

- Kuh, G. D., and E. J. Whitt. 1988. The Invisible Tapestry: Culture in American Colleges and Universities. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Higher Education. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1.

- Leppink, J. 2015. “On Causality and Mechanisms in Medical Education Research: An Example of Path Analysis.” Perspectives on Medical Education 4 (2): 66–72. doi: 10.1007/s40037-015-0174-z

- Lillis, D. 2012. “Systematically Evaluating the Effectiveness of Quality Assurance Programmes in Leading to Improvement in Institutional Performance.” Quality in Higher Education 18 (1): 59–73. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2012.663549

- Lipsey, M. W., and D. B. Wilson. 2001. Practical Meta-Analysis. London: Sage.

- Lok, P., and J. Crawford. 1999. “The Relationship Between Commitment and Organizational Culture, Subculture, Leadership Style and Job Satisfaction in Organizational Change and Development.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 20 (7): 365–74. doi: 10.1108/01437739910302524

- Lomas, L. 1999. “The Culture and Quality of Higher Education Institutions: Examining the Links.” Quality Assurance in Education 7 (1): 30–34. doi: 10.1108/09684889910252513

- Lomas, L. 2004. “Embedding Quality: the Challenges for Higher Education.” Quality Assurance in Education: An International Perspective 12 (4): 157–65. doi: 10.1108/09684880410561604

- Lowe, K. B., K. G. Kroeck, and N. Sivasubramaniam. 1996. “Effectiveness Correlates of Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Review of the MLQ Literature.” The Leadership Quarterly 7 (3): 385–425. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(96)90027-2

- Lueddeke, G. R. 2003. “Professionalising Teaching Practice in Higher Education: a Study of Disciplinary Variation and ‘Teaching-Scholarship.” Studies in Higher Education 28 (2): 213–228. doi: 10.1080/0307507032000058082

- Luthans, F., and B. J. Avolio. 2003. “Authentic Leadership: A Positive Developmental Approach.” In Positive Organizational Scholarship, edited by K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, and R. E. Quinn, 241–61. San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler.

- Marchiori, D. M., and A. B. Henkin. 2004. “Organizational Commitment of a Health Profession Faculty: Dimensions, Correlates and Conditions.” Medical Teacher 26 (4): 353–58. doi: 10.1080/01421590410001683221

- Maull, R., P. Brown, and R. Cliffe. 2001. “Organisational Culture and Quality Improvement.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 21 (3): 302–26. doi: 10.1108/01443570110364614

- Menon, S. T. 1999. “Psychological Empowerment: Definition, Measurement, and Validation.” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement 31 (3): 161–164. doi: 10.1037/h0087084

- Meyer, J. P., and N. J. Allen. 1991. “A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment.” Human Resource Management Review 1 (1): 61–89. doi: 10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

- Meyer, J. P., N. J. Allen, and C. A. Smith. 1993. “Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Test of a Three-Component Conceptualization.” Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 538–551. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

- Meyer, J. P., M. Gagné, and N. M. Parfyonova. 2010. “Toward an Evidence-Based Model of Engagement: What We Can Learn from Motivation and Commitment Research.” In The Handbook of Employee Engagement: Perspectives, Issues, Research and Practice, edited by S. Albrecht, 62–73. Cheltenham: Edwin Elgar.

- Meyer, J. P., D. J. Stanley, L. Herscovitch, and M. Topolnytsky. 2002. “Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences.” Journal of Vocational Behaviour 61 (4): 20–52. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

- Mowday, R. T., R. M. Steers, and L. W. Porter. 1979. “The Measurement of Organizational Commitment.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 14 (2): 224–47. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1

- Naidoo, R., A. Shankar, and E. Veer. 2011. “The Consumerist Turn in Higher Education: Policy Aspirations and Outcomes.” Journal of Marketing Management 27 (11–12): 1142–62. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2011.609135

- Newton, J. 2000. “Feeding the Beast of Improving Quality?: Academics’ Perceptions of Quality Assurance and Quality Monitoring.” Quality in Higher Education, 6 (2): 153–63. doi: 10.1080/713692740

- Newton, J. 2002. “Barriers to Effective Quality Management and Leadership: Case Study of two Academic Departments.” Higher Education 44 (2): 185–212. doi: 10.1023/A:1016385207071

- Nunnally, J. C., and I. H. Bernstein. 1994. Psychometric Theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Osseo-Asare, D. L., D. Longbottom, and W. D. Murphy. 2005. “Leadership Best Practices for Sustaining Quality in UK Higher Education from the Perspective of the EFQM Excellence Model.” Quality Assurance in Education: An International Perspective 13 (2): 148–70. doi: 10.1108/09684880510594391

- Ovseiko, P. V., and A. M. Buchan. 2012. “Organizational Culture in an Academic Health Center: an Exploratory Study Using a Competing Values Framework.” Academic Medicine 87 (6): 709–18. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182537983

- Pierce, J. L., T. Kostova, and K. T. Dirks. 2003. “The State of Psychological Ownership: Integrating and Extending a Century of Research.” Review of General Psychology 7 (1): 84–107. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.7.1.84

- Postmes, T., M. Tanis, and B. De Wit. 2001. “Communication and Commitment in Organizations: A Social Identity Approach.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 4 (3): 227–46. doi: 10.1177/1368430201004003004

- Powell, T. C. 1995. “Total Quality Management as Competitive Advantage: A Review and Empirical Study.” Strategic Management Journal 16 (1): 15–37. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250160105

- Prajogo, D. I., and C. M. McDermott. 2005. “The Relationship Between Total Quality Management Practices and Organizational Culture.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 25 (11): 1101–22. doi: 10.1108/01443570510626916

- Quinn, R., H. Hildebrandt, P. Rogers, and M. Thompson. 1991. “A Competing Values Framework for Analyzing Presentational Communication in Management Contexts.” Journal of Business Communication 28 (3): 213–32. doi: 10.1177/002194369102800303

- Quinn, R. E., and J. Rohrbaugh. 1983. “A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis.” Management Science 29 (3): 363–77. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.29.3.363

- Reitsma, A. 2003. “Kritische succesfactoren bij visitatie en kwaliteitsverbetering van P&A opleidingen. Case study onderzoek” [Critical Success Factors in Visitation and Quality Improvement of Personnel Management Programmes, A Case-Based Approach]. PhD thesis, Open Universiteit, Heerlen.

- Schwarz, S., and D. F. Westerheijden. 2004. Accreditation and Evaluation in the European Higher Education Area. Higher Education Dynamics Vol. 5. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Smart, J. 2003. “Organizational Effectiveness of 2-Year Colleges: the Centrality of Cultural and Leadership Complexity.” Research in Higher Education 44 (6): 673–703. doi: 10.1023/A:1026127609244

- Spreitzer, G. M. 1995. “Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement and Validation.” Academy of Management Journal 38 (5): 1442–65. doi: 10.2307/256865

- Stage, F. K., C. C. Hasani, and N. Amaury. 2004. “Path Analysis: an introduction and Analysis of a Decade of Research.” The Journal of Educational Research 98 (1): 5–13. doi: 10.3200/JOER.98.1.5-13

- Steinert, Y., K. Mann, B. Anderson, B. M. Barnett, A. Centeno, L. Naismith, D. Prideaux, et al. 2016. “A systematic Review of Faculty Development Initiatives Designed to Enhance Teaching Effectiveness: A 10-Year Update.” Medical Teacher BEME guide No. 40: 1–18.

- Thornhill, A., P. Lewis, and M. N. K. Saunders. 1996. “The Role of Employee Communication in Achieving Commitment and Quality in Higher Education.” Quality Assurance in Education 4 (1): 12–20. doi: 10.1108/09684889610107995

- Trivellas, P., and D. Dargenidou. 2009. “Organisational Culture, job Satisfaction and Higher Education Service Quality. The Case of Technological Educational Institute of Larissa.” The TQM Journal 21 (4): 382–99. doi: 10.1108/17542730910965083

- Ullman, J. B. 2001. “Structural Equation Modeling.” In Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th ed., edited by B. G. Tabachnick and L. S. Fidell, 653–771, Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Vandewalle, D., L. Van Dyne, and T. Kostova. 1995. “Psychological Ownership: An Empirical Examination of its Consequences.” Group & Organization Management 20 (2): 210–26. doi: 10.1177/1059601195202008

- Van Dyne, L., and J. L. Pierce. 2004. “Psychological Ownership and Feelings of Posession: Three Field Studies Predicting Employee Attitudes and Organizational Citizenship Behavior.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 25 (4): 439–59. doi: 10.1002/job.249

- Välimaa, J. 1998. “Culture and Identity in Higher Education Research.” Higher Education 36 (2): 119–38. doi: 10.1023/A:1003248918874

- Wasti, S. A. 2003. “Organizational Commitment, Turnover Intentions and the Influence of Cultural Values.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 76 (3): 303–21. doi: 10.1348/096317903769647193

- Westerheijden, D. F., V. Hulpiau, and K. Waetens. 2007. “From Design and Implementation to Impact of Quality Assurance: An Overview of Some Studies into What Impacts Improvement.” Tertiary Education and Management 13 (4): 295–312. doi: 10.1080/13583880701535430

- Williams, J. 2016. “Quality Assurance and Quality Enhancement: Is There a Relationship?.” Quality in Higher Education 22 (2): 97–102. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2016.1227207