ABSTRACT

At a time of growing interest in graduate entrepreneurship, this study focuses on the role of mentoring in developing students’ entrepreneurial careers in the Early Years of University (EYU). An integrated conceptual framework is presented that combines mentoring functions and entrepreneurial development (entrepreneurial intentions and nascent behaviour). Data from 18 student mentees who expressed an interest in starting their own businesses, and who were mentored by alumni entrepreneurs of a British University were analysed. Findings support the applicability of our framework in addressing the multi-faceted nature of the mentoring functions, which include a range of knowledge development and socio-emotional functions such as entrepreneurial career development, specialist business knowledge, role-model presence and emotional support. The results contribute to understanding mentoring functions and entrepreneurial development in the EYU. Implications for the design of entrepreneurial mentoring programmes and avenues for future research are discussed.

Introduction

Since the seminal work of Kram (Kram Citation1985; Kram and Isabella Citation1985), research on mentoring has flourished, with a broader recognition of its potential to benefit mentees’ careers (see, for example, reviews by Allen et al. Citation2008; Ragins and Kram Citation2007) including in entrepreneurship (e.g. Gimmon Citation2014). Despite this growth in mentoring research, three distinct gaps in knowledge with regard to entrepreneurship education in higher education (HE) remain. First, although there is a growing body of research on mentoring outcomes in general (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009), within a university context there is little research that examines whether mentoring helps shape entrepreneurial outcomes such as entrepreneurial intentions and nascent behaviour. Addressing such student outcomes is critical because of the increasing use of mentoring in universities to develop entrepreneurs (Wilbanks Citation2013).

Second, mentoring can serve a variety of developmental and support functions (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009; discussed later). Nonetheless, there remains a lack of theoretical and empirical research on the application of these functions in the context of undergraduates’ entrepreneurial careers, including how these functions then influence entrepreneurial outcomes (Souitaris, Zerbinati, and Al-Laham Citation2007).

Third, while there exists an abundance of research on the impact of entrepreneurship education (EE) in HE (see Nabi et al. Citation2017 for an extensive review), little of this research focuses on the early stages of the university journey. Instead, research targets students who are close to graduation or have graduated (cf. Collins, Hannon, and Smith Citation2004; Nabi et al. Citation2018). The same focus applies to mentoring research in HE. However, the early stages of HE are not devoid of developmental promise, and indeed, are pivotal to shaping and supporting career development (Savickas Citation2002). Furthermore, the early years in HE are increasingly becoming a university priority in terms of student entrepreneurial experience and development (Nabi et al. Citation2018). The transition into HE and potentially into entrepreneurial careers is set against a backdrop of a period of exploration and crystallisation of career interests for youth (Savickas Citation2002). This pre-venture creation period represents a crucial time for mentoring in terms of supporting nascent activities and an entrepreneurial career path (Souitaris, Zerbinati, and Al-Laham Citation2007). Students are therefore likely to benefit from mentoring in these early years of HE (cf. Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000).

Consequently, we explore the role of mentoring in shaping entrepreneurial careers in the Early Years of University (EYU). More specifically, using the framework outlined below, we focus on the following research questions: What are the mentoring functions experienced by EYU students pursuing entrepreneurial careers, and how might these functions influence entrepreneurial development? We tackle these questions by drawing on Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) framework of mentoring in HE, applying and extending this to the entrepreneurship mentoring scenario. We also make reference to the two most-widely used models in the entrepreneurial intent literature: Ajzen’s (Citation1991) theory of planned behaviour and Shapero and Sokol’s (Citation1982) entrepreneurial event model (Krueger, Reilly, and Carsrud Citation2000). Based on the resulting extended framework, we then link mentoring functions to entrepreneurial development, specifically entrepreneurial intentions and nascent behaviour (Souitaris, Zerbinati, and Al-Laham Citation2007). Utilising qualitative data from students on a mentoring programme at a British university, the result is an overarching mentoring framework for entrepreneurship education in HE. Our research provides insights into how EYU mentoring supports prospective entrepreneurs and should appeal to researchers, policy-makers and practitioners interested in understanding and assisting early stages of entrepreneurial development.

Literature review

Mentoring functions for prospective entrepreneurs in the EYU

Mentoring can be defined as a one-to-one relationship between an experienced person (a mentor) and a less experienced person (a protégé or mentee) that provides a variety of developmental and personal growth functions (e.g. Crisp and Cruz Citation2009; Mullen Citation1998). Although there is some contention as to the difference between mentoring and coaching (D’Abate, Eddy, and Tannenbaum Citation2003; Garvey Citation2004), mentoring generally tends to be more developmental (here helping mentees to grow and understand how to be entrepreneurs), directed by the mentee and hence more focused on personal growth than formal results, and voluntary on the part of the mentor. In contrast, coaching tends to be more focused on specific formal outcomes (commonly set by the organisation) and tends to entail a business relationship with coaches financially rewarded for their work (Audet and Couteret Citation2012).

In this research, we draw directly on Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) framework of mentoring in the HE literature between 1990 and 2007, which itself extends the work of Kram (Citation1985) and Jacobi (Citation1991). Crisp and Cruz's framework comes closest to our scenario because it focuses specifically on mentoring in an undergraduate context and is therefore most applicable to our interest in early development of entrepreneurial careers in university. Crisp and Cruz (Citation2009) identify four major mentoring functions specifically within an undergraduate/student context: (a) support for setting a career path; (b) advancing students’ subject knowledge; (c) existence of a role model to emulate and from whom to learn how to overcome challenges; and (d) psychological and emotional support. Moreover, Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) mentoring functions are likely to be particularly pertinent to our developmental context of the EYU entrepreneur in which, for example, mentees are at an early stage in higher education and entrepreneurial careers, and are likely to approve of the help for choosing and setting a career path, developing subject knowledge, as well as emotional and psychological support a mentor can provide (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009; Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000). Thus, Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) framework relates more to a mentoring and mentee-led position, which is largely the approach we adopt, but nevertheless acknowledges that mentoring can incorporate elements of coaching i.e. guiding and advising mentees when necessary to address specific development of knowledge for specific needs (Garvey Citation2004; Kram Citation1985; Wilbanks Citation2013).

Mentoring for entrepreneurship in the EYU context is also different to other more typical, i.e. organisational, mentoring contexts. For example, as outlined earlier, undergraduates are transitioning into entrepreneurial careers against a background of career exploration, adaptation and maturity (Savickas Citation2002). This combines with a range of contextual factors related to entrepreneurial careers such as higher risk of failure and financial loss compared to more traditional careers, and a complex range of multiple functional roles involved in the start-up process, such as operations, planning, marketing, sales, accounting and so forth (Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000). Thus, mentoring recent university entrants for entrepreneurship has a different career development context from those in a traditional organisational context since students are planning to start and manage their own businesses, rather than being employees (St-Jean Citation2011). Similarly, entrepreneur mentoring in the student/EYU context differs from general entrepreneur mentoring, since students tend to be in a different transitionary and educational scenario, as opposed to others who may be unemployed or looking to grow an established business (cf. St-Jean Citation2011; Waters et al. Citation2002).

To illustrate further, the anticipated relevance of Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) four mentoring functions to the undergraduate entrepreneurship context, the mentoring function of supporting a career path (in our case, developing an entrepreneurial career path) may assist students in making sense of the entrepreneurial process through developing entrepreneurial maturity. Here entrepreneurial maturity reflects a capacity on the part of mentees to make and act upon vocational choices by analysing information on themselves (e.g. strengths, interests, and intentions), and the occupation (in our case, steps needed to start-up a business) (Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000; Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2010a). Similarly, Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) mentoring function of acquiring knowledge appears meaningful in the EYU, as mentees may benefit from learning entrepreneurial knowledge both generally and specifically in relation to their particular business idea, including product, market, financial and planning knowledge (Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2009, Citation2010a).

Regarding Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) socio-emotional support functions, we expect these also to be relevant to EYU students pursuing entrepreneurial careers. In this context, the presence of the mentor, as a role model, incorporates admiration of their journey and a desire to learn from as well as to emulate them; thus, affording the mentor an inspirational role (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009). Both St-Jean (Citation2011) and Wilbanks (Citation2013) also acknowledge this role-mode function in an entrepreneurship-mentoring context. Furthermore, Hedner, Abouzeedan, and Klofsten (Citation2011) suggest mentoring can help develop entrepreneurial resilience, enabling the overcoming of challenges, adversities or setbacks in the entrepreneurial career path.

Mentoring and entrepreneurial outcomes in the EYU

Entrepreneurial outcomes in general

Studies suggest a wide range of potential entrepreneurial outcomes from mentoring entrepreneurs, ranging from cognitive and affective measures such as entrepreneurial attitudes, knowledge, learning, opportunity recognition and self-esteem, to behavioural measures such as start-up behaviour and business performance (St-Jean Citation2011; Waters et al. Citation2002; Wilbanks Citation2013). In this study, the focus is on two entrepreneurial outcomes, namely entrepreneurial intentions and nascent entrepreneurial behaviour, because of their applicability to EYU students (as discussed below) and the paucity of previous research addressing them in relation to mentoring.

Entrepreneurial intentions

Entrepreneurial intentions, defined as ‘a conscious awareness and conviction by an individual … to set up a new business’ (Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2010b, 538), are argued to be a powerful predictor of entrepreneurial behaviour (Bird Citation1988). While a large body of research exists on entrepreneurial intentions (see Bae et al. Citation2014), there remains a lack of research focusing specifically on the relationship between entrepreneurial mentoring functions and entrepreneurial intentions. Thus, major reviews of the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions (e.g. Nabi et al. Citation2017) ignore the role of mentoring, as do recent meta-analyses of entrepreneurial intentions (e.g. Bae et al. Citation2014) as well as reviews of mentoring in the education literature (e.g. Crisp and Cruz Citation2009).

Conceptualised as a form of entrepreneurship education (Gimmon Citation2014), mentoring is likely to help in developing (or at least maintaining) students’ entrepreneurial intentions for the following reasons: First, extending from Crisp and Cruz (Citation2009), the mentoring function of supporting an entrepreneurial career path can be linked to entrepreneurial intentions through entrepreneurial maturity. Thus, the mentors can help their mentees engage in self-exploration and occupational-exploration, which may then consequently influence entrepreneurial intentions (e.g. Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000; Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2009, Citation2010a). Furthermore, mentors can also support the development of a range of specialist entrepreneurial knowledge (e.g. market or financial knowledge). Indeed, research suggests this type of knowledge can be developed through mentoring at university (Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2009, Citation2010a), and such entrepreneurial knowledge has been linked to developing entrepreneurial intentions (Souitaris, Zerbinati, and Al-Laham Citation2007).

Second, Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) role-modelling and emotional support functions may augment students’ entrepreneurial intentions: the former by real-life encouragement and inspiration (cf. Brockhaus and Horwitz 1986, cited in Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000), and the latter by providing psycho-emotional comfort, moral support, or empathy (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009; Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000).

Finally, the link between mentoring functions and entrepreneurial intentions is enriched by considering entrepreneurial intentions models, the most popular being the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB, Ajzen Citation1991) and the Entrepreneurial Event Model (EEM, Shapero and Sokol Citation1982). Applied to entrepreneurship, TPB posits that individuals’ intentions depend on three antecedents: attitudes towards starting up a business (degree of favourable or unfavourable attitudes), subjective norms (perceived social pressure to pursue or not to pursue entrepreneurship) and perceived behavioural control (belief about perceived ease or difficulty in being able to implement entrepreneurial behaviour and it being within their control). Similar to the TPB (Krueger, Reilly, and Carsrud Citation2000), EEM focuses on perceived desirability (attraction to entrepreneurship), perceived feasibility (viability of starting up a business), and propensity to act (disposition to act).

Although there is no empirical research to our knowledge that directly links Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) mentoring functions to entrepreneurial intentions, the theoretical link is quite strong when considering both TPB and EEM. Thus, and acknowledging that a fully-fledged discussion would fall beyond the remit of this paper, theoretically mentoring can help develop entrepreneurial intentions through changing attitudes, enhancing subjective norms, or beliefs about perceived behavioural control (TPB) or perceived desirability or feasibility (EEM), or a combination thereof (Schlaegel and Koenig Citation2014). For example, the mentoring function of helping to support an entrepreneurial career path through self and entrepreneurial learning is likely to enhance positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship by enhancing its desirability as a career option. Similarly, such mentor support for entrepreneurial career development can reinforce mentees’ perceived behavioural control or capability beliefs, in terms of the perceived visualisation or ease in becoming an entrepreneur by accumulating relevant know-how about the start-up process, perhaps through seeing the mentor's achievements, and hence perceived feasibility. The role model function can also enhance entrepreneurial intentions because the mentor is in a position to persuade mentees that unpleasant emotions (e.g. uncertainties, anxieties and fears) are manageable, just as they have done themselves, and thus within their capability and control, thereby enhancing the perceived desirability and feasibility of entrepreneurship (cf. Schlaegel and Koenig Citation2014; St-Jean, Radu-Lefebvre, and Mathieu Citation2018). This may also help students to become more resilient in dealing with the challenges during the start-up process (Cardon et al. Citation2012; Hedner, Abouzeedan, and Klofsten Citation2011; Nabi et al. Citation2018) and hence facilitate entrepreneurial intentions.

Nascent behaviour

Nascent entrepreneurial behaviour is the immediate precursor to the formation of a new business. More specifically, research defines nascent behaviour in terms of pre-start-up activities such as business planning, seeking sources of finance for the new firm, or interaction with the external environment e.g. engaging in sales and marketing activities, networking and exploration of contacts and so forth (cf. Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2010a; Souitaris, Zerbinati, and Al-Laham Citation2007). In this latter sense, nascent behaviour can be considered as a means of acquiring social capital (Bourdieu Citation1986; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Although not as widely studied as entrepreneurial intentions, nascent behaviour is pivotal to entrepreneurial development because it comprises the move from entrepreneurial intentionality to pre-start up behaviour. This therefore also extends beyond the typical application of TPB and EEM in entrepreneurship where the usual focus of these models is the explanation of antecedents of intent, not the actual behaviour itself (see for example Krueger, Reilly, and Carsrud Citation2000).

Moreover, Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) mentoring functions offer a perspective on how mentoring may influence nascent behaviour. For example, regarding the career path development and specialist knowledge functions, the mentor can provide guidance and facilitate the accumulation of specific entrepreneurial knowledge, especially if tailored to individual business ideas (cf. Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000; Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2009). Through such knowledge development, perceived control over behaviour (in this case entrepreneurial behaviour) is likely to be particularly realistic and accurate, which in turn has been linked directly to performing (or realising) the behaviour (TPB, Ajzen Citation1991). As per EEM (Shapero and Sokol Citation1982) in terms of mentees’ propensity to act, the mentor can also push for action, directly via encouraging action, or indirectly via facilitating mentees’ self-evaluation, or by addressing negative emotions, such as fear of failure, both of which can help mentees overcome doubts (St-Jean, Radu-Lefebvre, and Mathieu Citation2018), and hence facilitate nascent behaviour.

Methodology

Design and sample

The study is based on a qualitative research design, although initially a survey completed by 268 first and second year students at a British university was employed to identify students with moderate levels of entrepreneurial intent (Thompson’s Citation2009 measure). These students were approached in an effort to maximise chances of interest in mentoring i.e. realisation of intentions through mentoring support, as well as to gain commitment. The 27 highest scoring students were approached (top 10%), 25 of whom subsequently responded to our request to participate in the mentoring process. Of these 25, 18 completed the entire mentoring programme. At the outset of the programme, the final participants still only had moderate levels of entrepreneurial intent, with an average of 4.6 (6-point scale, 6 being highest score), allowing scope for further development in the future. presents participants’ demographic details. We note briefly that we were unable to identify any obvious differences in mentees’ use of mentoring functions or entrepreneurial development based on demographic characteristics in , suggesting that these demographics did not play a major role in our study. Nonetheless, we recognise the small sample size and hence the very indicative nature of this observation.

Table 1. Sample demographics.

Mentors comprised former university students who had gone on to start businesses that were still running. Not only were our mentors entrepreneurs, which should prove beneficial in supporting nascent entrepreneurs, they had all been through the student-to-entrepreneur transition themselves, and were therefore likely to be in a strong position to mentor students given shared experiences. Of the fourteen initially contacted mentors, four withdrew for work or personal reasons. provides mentors’ details. We attempted to match mentors with mentees in terms of areas of interest and expertise.

Both mentors and mentees received training covering the purpose of the mentoring relationship and signed a confidentiality agreement detailing codes of conduct. The mentors’ role was developmental via a process of reflection, questions, challenges and feedback. This process allowed mentees to reach decisions themselves and to formulate their own goals and action plans (Alred and Garvey Citation2010). All mentors received training on: (1) the role of a mentor (e.g. to be developmental, supportive, and impartial); (2) models of mentoring and development (e.g. Alred and Garvey Citation2010); and (3) how to allow mentees to set, achieve, and review their own progress. This training also aligns well with the ‘ideal mentoring style’ where the mentor is less directive than traditional coaching (Garvey Citation2004), yet highly involved in terms of helping mentees to find answers to their questions (Gravells Citation2006; St-Jean and Audet Citation2013).

The mentoring process ran for 5-months (Nov 2016 – March 2017) and entailed the mentor-mentee pair reaching an agreement on the frequency and scope of their meetings, with the recommended frequency of at least once per month. Mentees were asked to keep a log of their meetings, and reflect on their learning, plans and development. These logs were confidential, intended solely to support mentees’ learning and consequently, we have not drawn directly on their content. Nonetheless, it was deemed that keeping a log added rigour to the process as it helped mentees to undertake ‘live’ reflection on their experience. Thus, the framework offered by our project (initial training, suggested number of meetings, request to keep a learning log) should have resulted in a similar, albeit not identical, structure to each mentoring relationship.

We employed semi-structured interviews to tap into the mentees’ experiences of the following three main areas: (1) start-up plans; (2) to what extent mentoring had supported them and what functions it served; and (3) the extent to which the mentoring programme helped entrepreneurial development (intentions and nascent behaviour). Each interview lasted 40–50 minutes.

Data analysis strategy

Using qualitative analysis software, NVivo, our analysis comprised four stages. In stage 1, we familiarised ourselves with the data by reviewing the transcripts. In stage 2, we applied Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) four mentoring functions to identify how these functions were involved in the mentoring process and led to our first-order themes: (1) Entrepreneurial career development; (2) Market/product/financial knowledge development; (3) Role-model presence; and (4) Emotional support. To ensure coding reliability, we engaged in a process of independent coding, comparison and recoding amongst the authors. In stage 3, the four first-order themes relating to mentoring functions were systematically probed again, using the same data analysis process, but with a focus on identifying second-order themes. Thus, our framework to understand how mentoring functions work, while drawing on Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) general mentoring framework for university students, develops this further within the context of entrepreneurial careers in the EYU. In stage 4, we repeated the aforementioned data analysis process examining second-order themes, but with a focus on the relationship between mentoring and entrepreneurial development. Here, entrepreneurial intentions did not reduce into further sub-themes, but our assessment of nascent behaviour, guided by Souitaris, Zerbinati, and Al-Laham (Citation2007), resulted in two second-order themes: nascent planning behaviour and external stakeholder interaction.

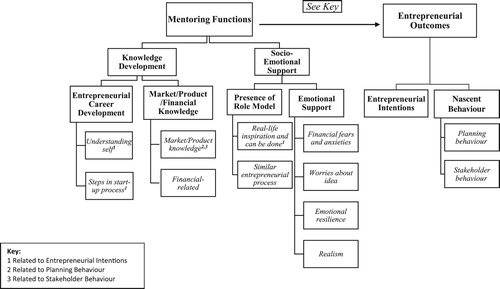

To understand mentees’ experiences holistically, we also reviewed their overall narratives through case summaries (Nabi et al. Citation2018) and established the frequency of themes by mentee to provide transparency to the analysis. This allowed us to triangulate mentees’ overall narratives against individual themes. An overview of our first and second-order themes is presented in and discussed in the next section.

Results

The qualitative analysis suggests a number of themes and sub-themes in relation to our conceptual framework (see ), that we first explore with reference to the nature of mentoring, before evaluating how mentoring relates to entrepreneurial development, via the concepts of entrepreneurial intentions and nascent behaviour.

Knowledge development

The first overarching mentoring function category, knowledge development, encompasses two main themes: entrepreneurial career development and market/product/financial knowledge. These concern the development of general knowledge about the entrepreneurial process, and market, product, and financial knowledge in relation to a specific business idea.

Entrepreneurial career development

Our data suggest mentoring helps to clarify mentees’ understanding of themselves and the entrepreneurial process. This then provides a ‘direction’ for their entrepreneurial careers to develop further, including specific steps required to move from idea to implementation. This supports the notion of mentoring developing entrepreneurial career maturity, by helping mentees to understand themselves (e.g. their own career intentions, goals, strengths, and ideas) and the entrepreneurial career path (e.g. the steps involved in becoming an entrepreneur). Regarding the former, for example, mentees focus on becoming more self-aware or aware of their own strengths and ideas.

The main advice was to explore my strengths because I know that I speak four languages, but I haven't really thought that that was going to be helpful so he [the mentor] helped me on trying to gain opportunities from those strengths … . (Afifah)

… I did not have really any like good prior knowledge that is relevant to today. So this mentoring program has helped me to get a clear understanding of how to start-up a business in today's world. (Mary)

Market/product/financial knowledge development

Mentees indicate mentoring assists in gaining business-specific knowledge. The data highlight sub-themes of developing mentees’ specialist market/product knowledge through research or analysis, and financial-related knowledge including financing and costs. Mentees explain how their mentor helps them to clarify the role of market/product research and issues related to the business planning process. For example, Hameed appreciates the importance of research in understanding legal (planning permission) requirements and to differentiate himself from competitors. On this note, mentoring helps mentees develop maturity in terms of reflecting and realistically thinking through what is required to bring the product to market. Similarly, Larry describes getting a fuller understanding of the importance of market/product knowledge from mentoring.

When I first went to him [mentor] in our first session I gave my idea … ., I knew nothing about market research. I did not even realize how to create the app … he basically helped develop my skills. He taught me that you need to research … He also taught me that you need to look at the market and make sure that it is feasible and it is sustainable … . (Larry)

[The mentor] has shown me ways I can get funds to start businesses … In terms of start-up cost and what not, he’d sent me a link of the Prince's Trust foundation to get money, like start-up loans, so that's showed me that there are places out there where you can gain funds … . So now I feel a bit more comfortable about the financial part. (Edgar)

He [the mentor] introduced me to a software developer and then when we were speaking to each other he was saying, basically an app is going to cost £20k–£30k to start up, but you can do this and it's only going to cost you £2k-£3k. So, he's saying you don't need to make the app straight off, you can make a hybrid website for mobile phones, which is going to save you so much money, so it cost £2k to make the hybrid website whereas the app would cost £30k. (Edgar)

Socio-emotional support

The second overarching mentoring function category, socio-emotional support, also incorporates two main themes, the presence of a role model and emotional support. The former relates to the existence of a mentor whose stories or achievements mentees learn and take inspiration from, and the latter reflects mentor support that is more directly of an emotional nature to address mentees’ fears and anxieties, resilience in dealing with setbacks, and realism.

Presence of entrepreneurial role model

This theme focuses on the participants actually seeing the mentors’ entrepreneurial achievements and that ‘it can be done’, rather than just being told that it is achievable. Seeing the mentors’ success on their entrepreneurial journeys serves to inspire mentees, and reassure them that the journey is realistic and achievable. This reflection of the ‘it can be done’ narrative is illustrated below.

To be honest, I definitely recommend the mentoring thing as well because it is helpful … I have learnt that if somebody else [mentor] can do it [start up a business], I can do it. (James)

You know we [mentor and mentee] were always talking like friends rather than you know I am the mentor and you are my mentee and I tell you what to do. You know what I mean, it was more like we were on the same level all the time like sharing experiences kind of things … . (James)

Emotional support

Beyond the role-model presence function, mentors provide a range of emotional support functions to EYU mentees. This theme focuses on mentors helping with emotion-based issues by directly addressing fears and anxieties of a financial nature, for example, of raising or losing capital, wasting time, or having large overheads.

Just the fear of taking a couple of years of my life to develop this business and if it does not work. Like how much time and money it would take, like what happens if I lose money … She [mentor] told me that if it is not making millions it does not mean you are losing millions. I know how [mentor's] business was running like low profits and breaking even point and paid a lot of wages, so it was not like a failure but it was a steady process. (Richard)

She [mentor] made me aware that it's ok to be worried about setting up some business and it is not going to work like nothing great has come easily. It takes the jump. It takes the fear to create something good. You have to take the risks and see if it works or not. (Sara)

… so I set up a Facebook page, and got friends to like it, and then I did it, and I got the stuff and put it on eBay. That got me down, because nobody was interested in it, so nobody bought anything, and I felt down about it and demotivated. So then, I spoke to [the mentor] again … He said, you know, you just tried it, you can't expect it to come straight away, and you need to keep working on it, don't give up. This helped to motivate me and keep going … . (Nicola)

I went into it with possibly too much like excitement and the prospects of being able to get into like property and the way he [mentor] has helped me and said like you need to think about this. There is a lot of like logistical stuff … there is a lot of research to be done. (Sue)

Entrepreneurial development

In this section, we address our second research question of how mentoring functions influence entrepreneurial development. We first discuss the impact of mentoring on mentees’ entrepreneurial intentions, before moving to nascent behaviour.

Entrepreneurial intentions

The results suggest mentoring influences entrepreneurial intentions in terms of either increasing or maintaining intentions, via specific mentoring functions, as described below. Two main patterns emerge. The first relates to those respondents for whom mentoring enhances entrepreneurial intentions (Jack, Harrison, Mary, James, Edgar, Larry, Nicola). Here, entrepreneurial intentions develop through the mentoring function of general development of knowledge about the start-up process, with mentees increasing their understanding of the entrepreneurial career path and steps required in the process in practice. These mentor functions play a pivotal role in facilitating mentees' favourable attitudes towards an entrepreneurial career. For example, mentoring enhances Jack's attitudes and intentions towards an entrepreneurial career as opposed to organisational employment after his mentor helps him understand how to start-up and run a company.

For me, it [mentoring programme] has taught me more [about start-up] for the future. It has just given me an understanding of how a company runs … I would say [entrepreneurial intentions] increased because before I was more interested in just getting a job and working for somebody else. But then I think the programme has definitely increased my passion into doing it [starting up a business] myself. (Jack)

[About the start-up process] I only knew the basics before and I was looking for ways to start-up … through [mentoring] it has definitely helped and definitely amplified like my knowledge … it [mentoring] has definitely maintained my intentions. … I believe my personal intentions have stayed the same. (Stephen)

This mentoring project helped me a lot so far on how to think appropriately, on how to think on my start up business and on the idea because it was a bit vague for me. I didn't know which thing is best for me, also it made me aware about what I hope to gain in my future career [intentions] and most importantly on trying to build strength to create business opportunities. (Afifah)

Nascent behaviour

The data suggest that mentoring plays a key role in the development of nascent entrepreneurial behaviour in terms of concrete planning and external stakeholder interaction. The data suggest mentoring encourages and pushes for such nascent behaviour, helping participants go beyond their ideas and knowledge to actual behaviour.

Regarding nascent planning behaviour, mentoring helps the mentees in our sample take specific actions that relate to their particular business idea, such as progressing business plans, applying pricing knowledge, or developing prototype designs. Furthermore, mentoring influences actual nascent activity through not only specific knowledge development, but also encouraging actions to be taken. Edgar (app business) and Andreas (music/events business), for example, illustrate how the mentor facilitates specific knowledge of ‘hybrid websites’ or ‘pricing ranges’ respectively, which in turn leads to actual nascent activity related to the mentees’ business ideas. Thus, the data suggest that mentoring is pivotal in inducing change through increasing perceptions of one's control over entrepreneurial behaviour and ‘influencing’ mentees to act and engage in nascent planning behaviour to move their business forward. This is illustrated below, where the mentor assists Edgar in understanding how to implement guidelines (enhancing perceived feasibility and behavioural control) and encourages the mentee's activity (business planning behaviour).

[Mentor] … not only would he give me the advice, but then he would tell me how I could implement his advice, even just back to the business plan, … I’d take the action to actually go and create the business plan, so like he did influence action from what he was explaining, like even with the software developer, when he said about the hybrid website, I then went away and looked at that, and actually researched what it was and how it worked … . (Edgar)

In sum, our focus here has been on a qualitative understanding of the mechanics of mentoring and what this means for entrepreneurial development. The most prevalent mentoring functions relate to understanding the start-up process, financial knowledge, role-model inspiration and alleviating financial worries. Emotion-based functions are the most widespread, for example, role-model inspiration is evident across the entire sample, and emotional support has the widest range of sub-themes e.g. financial/idea worries, resilience, and realism. Similarly, the data indicate a positive link between mentoring functions and entrepreneurial development. That is, understanding steps in the start-up process and role-model inspiration are related to entrepreneurial intentions, while market/product knowledge is related more to nascent planning and stakeholder behaviour.

Discussion and conclusions

This research explores the role of mentoring in shaping students’ entrepreneurial careers in the EYU, focusing on two interrelated research questions: What are the mentoring functions experienced by EYU students pursuing entrepreneurial careers and how might these functions influence entrepreneurial development (i.e. entrepreneurial intentions and nascent behaviour)? In doing so, we developed a conceptual framework that integrates mentoring functions and entrepreneurial development outcomes. While the support mentoring can provide undergraduates (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009) and entrepreneurs is recognised (e.g. St-Jean Citation2011; Wilbanks Citation2013), no studies, to the best of our knowledge, have explored mentoring for entrepreneurship in the career development context of the early years of HE.

Our analysis suggests four key contributions. First, we extend Crisp and Cruz’s (Citation2009) framework to students for the purposes of entrepreneurial career development. Here, we identify a range of knowledge development functions (e.g. understanding of self, entrepreneurial/start-up process, market/product/financial knowledge) and socio-emotional functions (e.g. role-model inspiration from mentors’ experiences, shared entrepreneurial process, emotional support addressing a range of anxieties about starting up a business) that specifically apply to entrepreneurial mentoring in the EYU. Furthermore, we recognise the complex interplay of mentoring functions based on individual needs. This is a result that lends support to previous research advocating a ‘tailored’ rather than generic approach to supporting students in making the transition from student to entrepreneur (Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2009; Nabi et al. Citation2018).

Second, our findings point to the importance of socio-emotional support and the development of entrepreneurial maturity especially in relation to knowledge development. With regard to the former, socio-emotional support, especially the role-model function and the inspiration it can provide, is highly valued by mentees, unsurprisingly perhaps given that anxiety is part of the entrepreneurial process (Cardon et al. Citation2012; Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000). With regard to the latter, the development of the ability to reflect and realistically assess situations (e.g. market or financing opportunities) and appreciate the confluence of steps required in the entrepreneurial process is supported by earlier studies (e.g. Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2000; Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2010a). Moreover, our study confirms the importance of the socio-emotional support mentoring function for entrepreneurship as indicated in the broader literature (Wilbanks Citation2013; Waters et al. Citation2002), albeit with a focus on the EYU mentoring context.

Third, our findings demonstrate how mentoring can support EYU entrepreneurial development (entrepreneurial intentions and nascent behaviour). Regarding entrepreneurial intentions, we have been able to identify parallels with both the TPB and EEM in that mentoring may increase positive attitudes (TPB)/perceived desirability (EEM) towards entrepreneurship, but also, and perhaps more importantly, perceived behaviour control (TPB)/ perceived feasibility (EEM). Thus, the importance of the mentor as role model, as someone who not only shows how to do things, but who provides the confidence that they can be done should not be underestimated. This does not mean the knowledge-development function should be ignored either, but that mentoring can play an important role for the development of perceived feasibility, a finding that highlights the role of self-efficacy beliefs in entrepreneurship generally (St-Jean, Radu-Lefebvre, and Mathieu Citation2018; Wilbanks Citation2013), but also specifically in the EYU context, where students will need more reassurance and inspiration about their potential capability. In this regard, the data suggests that role modelling was useful to EYU students because they believed that the mentor helped them to visualise the entrepreneurial journey, evoking the notion that ‘if they (the mentor) can do it, I (the mentee) can do it’. This clearly supported mentees’ perceptions about their perceived behavioural control, that entrepreneurship is feasible and achievable, and helped to enhance or maintain entrepreneurial intentions.

Fourth, and following on from the above, our findings show how mentoring (specifically the knowledge development function) can enhance nascent behaviour, especially nascent planning behaviour (business plans, prototypes, market testing), and stakeholder behaviour (networking and engagement with stakeholders). Moreover, our results about knowledge development functions of mentoring (e.g. specific market/product/financial knowledge) suggest that mentors, incorporating some elements of coaching (e.g. helping mentees to develop specific entrepreneurial knowledge), influences perceived control by providing realistic knowledge about their business idea, which in turn leads to nascent behaviour; the latter lending support to Ajzen’s (Citation1991) position that an individual's perceived behavioural control influences actual behaviour, especially if he/she acquires realistic and accurate knowledge or resources. This also reinforces the idea that while mentoring tends to be mentee-led, which is largely the approach we adopt in our research, some aspects of coaching did emerge, such as specific knowledge development to address mentees’ specific business needs, and this actually helps the mentees’ nascent planning and networking behaviour.

A final point to note, one that might benefit from further research, is the mentor's ability to change the mentee's ‘habitus’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). That is, we shift towards a contextualist explanation of careers in acknowledging ‘status identity’ (Savickas Citation2002, 165) in forming career decisions. Thus, by associating with entrepreneurs and other business people (e.g. suppliers, funders, marketers) entrepreneurship becomes more ‘normal’, possibly even shifting students’ identities from that of student to that of entrepreneur (this relates also to the subjective norms element of the TPB, i.e. making entrepreneurship an acceptable, even desirable activity). Thus, we extend Crisp and Cruz (Citation2009) by demonstrating how mentoring can play a useful role in the development of nascent entrepreneurial activity via the individual's context and therefore ‘habitus’ (if we were to take a sociological perspective, Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), as opposed to just intentional, even in the early stages of university education.

In terms of helping prospective entrepreneurs in the EYU, our findings indicate the following for the design and implementation of mentoring programmes in entrepreneurship, as well as for future research in the area. Our proposed overarching conceptual framework that links mentoring functions with entrepreneurial development could serve as a basis for the tailoring of student-specific mentoring packages. For example, while some mentees may need more help with knowledge development functions, others may place more emphasis on socio-emotional ones, such as financial worries, and yet others may need a particular configuration of support, agreed after the mentees discuss their learning objectives. Such an approach should allow for a more flexible and tailored programme of support.

Second, our research suggests that while knowledge-based functions are useful in their own right, mentors and programme designers may also need to factor in a broader range of socio-emotional sub-functions as these appeared relatively more important for EYU students. That is, mentor training that focuses on the range of potential emotions, worries and anxieties that EYU students might face may be worthy of consideration, as would training around ‘emotional’ reassurance and resilience of mentees (cf. Cardon et al. Citation2012). Such issues are likely to be more pronounced in EYU students because they are still transitioning into entrepreneurship (and HE), exploring and then crystallising their entrepreneurial careers (Nabi, Holden, and Walmsley Citation2010a; Savickas Citation2002).

Third, since we found that mentoring functions from an EYU mentoring programme can help prospective entrepreneurs develop their careers by facilitating integration across different functional areas of entrepreneurship education such as operations, planning, marketing and so forth, this raises the question whether other students in HE may also benefit from mentoring in the EYU. For example, universities could consider such mentoring programmes as part of a student support initiative to help undergraduates’ early transition into careers. This is especially relevant given the growing focus on graduate employability and indeed entrepreneurship and self-employment across all areas of HE (Young Citation2014). Our mentoring framework in the EYU could therefore be applied to other occupations/subject areas with positive impact on employability outcomes. This could provide an early and more tailored developmental experience for students from the outset of HE.

Finally, we acknowledge an important limitation of our study – we only focus on mentees’ assessment of their development (rather than drawing also on the mentors’ perspective, and comparing the two parts of the dyad for example). However, their perspective could usefully be considered in future research. Further, the mentoring programme ran for 5 months. Although this could be considered short compared to other mentoring programmes (Kram Citation1985), entrepreneurship education or mentoring programmes may vary from a few months to a few years (e.g. five months in Souitaris, Zerbinati, and Al-Laham Citation2007). We believe that the mentoring in this study did provide valuable support as evidenced by our findings. However, further research of the impact of mentoring would benefit from a longer time-scale.

We also acknowledge that while we could not find any discernible difference in functions and outcomes based on demographic factors, and indeed this was not the aim of our research, further research is warranted, given the small sample and lack of previous research in the area. Moreover, using our framework future studies could still explore more complex patterns, such as: whether, and in which ways, same-gender mentors influence the mentoring relationship in terms of functions and impact on development, the impact of mentor intervention styles e.g. directive vs nondirective or involved vs disengaged (St-Jean and Audet Citation2013), and further insights into how mentoring facilitates the integration of different functional areas of entrepreneurship (marketing, operations, finance and so forth). Overall, our research provides a conceptual framework for prospective EYU entrepreneurs and mentoring for entrepreneurship programmes, and importantly a coherent foundation for further research and practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Editors and anonymous reviewers for providing constructive and helpful guidance throughout the review process. We also thank Prof. Crisp (US), Prof. St-Jean (Canada) and Catherine Jones (UK) for comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Ajzen, I. 1991. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (2): 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Allen, T., L. Eby, K. O’Brien, and E. Lentz. 2008. “The State of Mentoring Research: A Qualitative Review of Current Research Methods and Future Research Implications.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (3): 343–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.08.004

- Alred, G., and R. Garvey. 2010. Mentoring Pocketbook. Alresford, UK: Management Pocketbooks.

- Audet, J., and P. Couteret. 2012. “Coaching the Entrepreneur: Features and Success Factors.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 19 (3): 515–31. doi: 10.1108/14626001211250207

- Bae, T., S. Qian, C. Miao, and J. Fiet. 2014. “The Relationship Between Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38 (2): 217–54. doi: 10.1111/etap.12095

- Bird, B. 1988. “Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas: The Case for Intention.” Academy of Management Review 13 (3): 442–53. doi: 10.5465/amr.1988.4306970

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 41–58. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cardon, M., M. Foo, D. Shepherd, and J. Wiklund. 2012. “Exploring the Heart: Entrepreneurial Emotion is a Hot Topic.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00501.x

- Collins, L., P. Hannon, and A. Smith. 2004. “Enacting Entrepreneurial Intent: The Gaps Between Student Needs and Higher Education Capability.” Education + Training 46 (8/9): 454–63. doi: 10.1108/00400910410569579

- Crisp, G., and I. Cruz. 2009. “Mentoring College Students: A Critical Review of the Literature Between 1990 and 2007.” Research in Higher Education 50 (6): 525–45. doi: 10.1007/s11162-009-9130-2

- D’Abate, C., E. Eddy, and S. Tannenbaum. 2003. “What’s in a Name? A Literature-Based Approach to Understanding Mentoring, Coaching, and Other Constructs that Describe Developmental Interactions.” Human Resource Development Review 2 (4): 360–84. doi: 10.1177/1534484303255033

- Garvey, B. 2004. “The Mentoring/Counseling/Coaching Debate: Call a Rose by Any Other Name and Perhaps It’s a Bramble?” Development and Learning in Organizations 18 (2): 6–8.

- Gimmon, E. 2014. “Mentoring as a Practical Training in Higher Education of Entrepreneurship.” Education + Training 56 (8/9): 814–25. doi: 10.1108/ET-02-2014-0006

- Gravells, J. 2006. “Mentoring Start-up Entrepreneurs in the East Midlands – Troubleshooters and Trusted Friends.” The International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching 4 (2): 3–23.

- Greenhaus, J., G. Callanan, and V. Godshalk. 2000. Career Management. London: Harcourt.

- Hedner, T., A. Abouzeedan, and M. Klofsten. 2011. “Entrepreneurial Resilience.” Annals of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2 (1): 79–86. doi: 10.3402/aie.v2i1.6002

- Jacobi, M. 1991. “Mentoring and Undergraduate Academic Success: A Literature Review.” Review of Educational Research 61 (4): 505–32. doi: 10.3102/00346543061004505

- Kram, K. 1985. Mentoring at Work. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

- Kram, K., and L. Isabella. 1985. “Mentoring Alternatives: The Role of Peer Relationships in Career Development.” The Academy of Management Journal 28 (1): 110–32.

- Krueger, N., M. Reilly, and A. Carsrud. 2000. “Competing Models of Entrepreneurial Intentions.” Journal of Business Venturing 15 (5/6): 411–32. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Mullen, E. 1998. “Vocational and Psychosocial Mentoring Functions: Identifying Mentors Who Serve Both.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 9 (4): 319–31. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.3920090403

- Nabi, G., R. Holden, and A. Walmsley. 2009. “Graduating into Start-up: Exploring the Transition.” Industry and Higher Education 23 (3): 199–207. doi: 10.5367/000000009788640233

- Nabi, G., R. Holden, and A. Walmsley. 2010a. “From Student to Entrepreneur: Towards a Model of Graduate Entrepreneurial Career-Making.” Journal of Education and Work 23 (5): 389–415. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2010.515968

- Nabi, G., R. Holden, and A. Walmsley. 2010b. “Entrepreneurial Intentions Among Students: Towards a Re-focused Research Agenda.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 17 (4): 537–51. doi: 10.1108/14626001011088714

- Nabi, G., F. Liñán, A. Fayolle, N. Krueger, and A. Walmsley. 2017. “The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda.” Academy of Management Learning and Education 16 (2): 277–99. doi: 10.5465/amle.2015.0026

- Nabi, G., A. Walmsley, F. Liñan, I. Akhtar, and C. Neame. 2018. “Does Entrepreneurship Education in the First Year of Higher Education Develop Entrepreneurial Intentions? The Role of Learning and Inspiration.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (3): 452–67. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1177716

- Ragins, B., and K. Kram. 2007. The Handbook of Mentoring at Work. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Savickas, M. 2002. “Career Construction. A Developmental Theory of Vocational Behaviour.” In Career Choice and Development, edited by D. Brown, 149–205. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Schlaegel, C., and M. Koenig. 2014. “Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intent: A Meta-Analytic Test and Integration of Competing Models.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38 (2): 291–332. doi: 10.1111/etap.12087

- Shapero, A., and L. Sokol. 1982. “The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship.” In Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship, edited by C. Kent, D. Sexton, and K. Vesper, 72–90. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Souitaris, V., S. Zerbinati, and A. Al-Laham. 2007. “Do Entrepreneurship Programmes Raise Entrepreneurial Intention of Science and Engineering Students? The Effect of Learning, Inspiration and Resources.” Journal of Business Venturing 22 (4): 566–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.002

- St-Jean, E. 2011. “Mentor Functions for Novice Entrepreneurs.” Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 17 (1): 65–84.

- St-Jean, E., and J. Audet. 2013. “The Effect of Mentor Intervention Style in Novice Entrepreneur Mentoring Relationships.” Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 21 (1): 96–119. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2013.784061

- St-Jean, E., M. Radu-Lefebvre, and C. Mathieu. 2018. “Can Less Be More? Mentoring Functions, Learning Goal Orientation and Novice Entrepreneurs’ Self-Efficacy.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 24 (1): 2–21. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-09-2016-0299

- Thompson, E. 2009. “Individual Entrepreneurial Intent: Construct Clarification and Development of an Internationally Reliable Metric.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33 (3): 669–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00321.x

- Waters, L., M. McCabe, D. Kiellerup, and S. Kiellerup. 2002. “The Role of Formal Mentoring on Business Success and Self-Esteem in Participants of a New Business Start-up Program.” Journal of Business and Psychology 17 (1): 107–21. doi: 10.1023/A:1016252301072

- Wilbanks, J. 2013. “Mentoring and Entrepreneurship: Examining the Potential for Entrepreneurship Education and for Aspiring New Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Small Business Strategy 23 (1): 93–101.

- Young, D. 2014. Enterprise for All: The Relevance of Enterprise in Education. London: Crown.