ABSTRACT

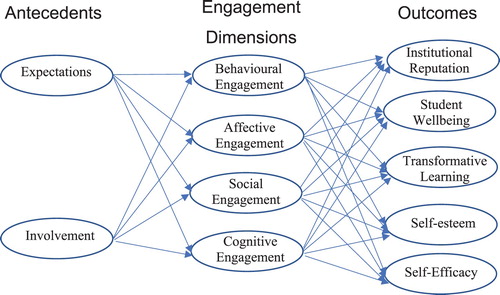

Creating the conditions that foster student engagement, success and retention remains a perennial issue within the higher education sector. Traditionally satisfaction has been prioritised in assessing student success. A more expansive, holistic and ontological perspective of the student experience that takes into account who and what students are becoming is required. This study develops a holistic approach to measuring student engagement. It models and measures two antecedents to engagement, namely involvement and expectations, four dimensions of engagement, namely affective, social, cognitive and behavioural engagement, and their relative and differential impact upon five specific student and institutional success outcomes namely, institutional reputation, student wellbeing, transformative learning, self-efficacy and self-esteem. A survey with a sample of 952 tertiary students enrolled at a major Australian tertiary institution was employed. A structural model was then specified to assess the structural relationships between the constructs. The results show that student expectations and involvement have an important seeding role in student engagement. Affective engagement was the most important determinant of institutional reputation, wellbeing, and transformative learning. Behavioural engagement determined self-efficacy and self-esteem. Cognitive and social engagement were necessary but not sufficient conditions for student success.

Introduction

The notion of the ‘student experience’ in higher education has a long and rich history. Systematic measuring of the student experience has historically focused on pedagogical approaches, educational practices, and student evaluations of teaching practice (Grebennikov and Shah Citation2013). Measuring attribute level evaluations of the student experience has offered institutions the ability to quantify and monitor the extent to which student’s baseline expectations are being met by the institution. Student satisfaction is a key benchmark metric of institutional performance and it continues to be prioritised in government policy;

… as they are the most important clients of higher education, students’ own assessments of the service they receive at university should be central to our judgement of the success of our higher education system. Their choices and expectations should play an important part in shaping the courses universities provide and in encouraging universities to adapt and improve their service (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills UK Citation2009, 70)

In addition, satisfaction has been found to be an inadequate measure performance due to its normative nature (Brown and Mazzarol Citation2009; Giese and Cote Citation2000). Satisfaction assumes a ‘tabula rasa’ blank slate effect, that is, that all students enter their tertiary journey in equilibrium, with similar experiences, contexts, tacit and implicit expectations, affective responses, and objectives. This approach can lead to a hollowing out effect whereby ‘education’ itself is arbitrarily separated out from ‘holistic experience’ leaving the notion of ‘the student experience’ in a social, cultural and political vacuum which is ‘discontinuous with what has come before it and insulated from all that is around it’ (Sabri Citation2011, 664). These perspectives again reiterate the need for a more holistic approach to conceptualising the tertiary journey, and the way in which it shapes student outcomes, and indeed identity.

The complexity of the tertiary experience as a transformative force was perhaps first alluded to by Dewey (Citation1938 [Citation1997], 35) who pointed out that the tertiary experience ‘modifies the one who acts and undergoes’ and ‘covers the formation of attitudes that are emotional and intellectual’. The higher education literature has arguably recently returned to this conceptualisation that takes into account ontological perspectives of the tertiary experience and its contribution to who and what students are becoming (Barnacle and Dall’Alba Citation2017). This perspective has been discussed under the nomological frameworks of ‘student involvement’, ‘academic integration’, the ‘student experience’, ‘research-led teaching’ and ‘academic engagement’ (Fredricks and McColskey Citation2012; Khademi Ashkzari, Piryaei, and Kamelifar Citation2018; Trowler Citation2010) and more recently, ‘student engagement’, ‘student partnership’ and ‘student collaboration’ (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014; Kahu and Nelson Citation2018).

Student engagement has been linked to an array of traditional success factors such as increased retention (Khademi Ashkzari, Piryaei, and Kamelifar Citation2018); high impact and lifelong learning (Artess, Mellors-Bourne, and Hooley Citation2017); curricular relevance (Trowler Citation2010); enhanced institutional reputation (Kuh et al. Citation2006); increased citizenship behaviours (Zepke, Leach, and Butler Citation2014); student perseverance (Khademi Ashkzari, Piryaei, and Kamelifar Citation2018); and work-readiness (Krause and Coates Citation2008). It has also been linked to more subjective and holistic outcomes for students themselves including; social and personal growth and development (Zwart Citation2009); transformative learning (Kahu Citation2013); enhanced pride, inclusiveness and belonging (Wentzel Citation2012); student wellbeing (Field Citation2009).

This study responds to calls for research to investigate the dimensions that drive positive student evaluations of the tertiary experience (e.g. Kuh et al. Citation2006). It develops a revised, approach to measuring student engagement. In order to capture the holistic nature of engagement on transformative tertiary experiences, this paper statistically examines the interrelationships between two antecedents, namely student expectations and involvement and their role in shaping the four dimensions of engagement namely affective, social, behavioural and cognitive engagement. This paper also examines the interrelationships between the engagement dimensions, and key student and institutional success factors including student wellbeing, transformative learning, self-efficacy, self-esteem and institutional reputation. In doing so it identifies the varied impact that these dimensions have on key institutional and student success factors.

Theoretical framework and model development

Student engagement has been referred to in the literature as: ‘student involvement’, ‘academic integration’, the ‘student experience’, ‘research-led teaching’ and ‘academic engagement’ (Fredricks and McColskey Citation2012; Khademi Ashkzari, Piryaei, and Kamelifar Citation2018; Trowler Citation2010). Recent conceptualisations have begun to more consistently adopt the terminology of ‘student engagement’, ‘student partnership’ and ‘student collaboration’ (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014; Kahu Citation2013). Student engagement is now considered to be an overarching ‘meta-construct’ in which an eco-system of students, educators, service staff and institutions interact to create enriching tertiary experiences (Junco Citation2012; Kahu Citation2013; Trowler Citation2010; Zepke Citation2014). Reschly and Christenson (Citation2012, 3) note that ‘academic time is important but not enough to accomplish the goals of education – development across academic, social-emotional, and behavioral domains. Student engagement is the glue, or mediator, that links important contexts’ such as student’s home lives, university, peers, and community to student success. As a meta-construct, Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris (Citation2004) note that engagement includes effort, persistence, concentration, attention; thoughtfulness and willingness to exert mental effort; and emotional responses such as interest, happiness, sadness, boredom and anxiety. In this way Blumenfeld et al. conceptualise student engagement as multidimensional and consisting of cognitive, emotional and behavioural dimensions.

Student engagement is also noted to manifest through both positive and negative valences (D’Errico, Paciello, and Cerniglia Citation2016). Positive valences are typically compiled of positive states such as enjoyment, pride, satisfaction and negative valences consisting of negative states such as anger, anxiety, frustration. Student engagement valences also vary in level of activation, polarity and intensity (Russell Citation1980). Research has demonstrated that positive engagement valence contributes to student success including attention, immersion and problem-solving (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia Citation2012). Conversely negative valences precipitate disengagement, avoidance and withdrawal and undermine students’ intrinsic motivation (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia Citation2012). Positive engagement is therefore central to academic success and achievement (De Carolis et al. Citation2019; D’Errico, Paciello, and Cerniglia Citation2016). See for additional conceptualisations of engagement.

Table 1. Selected definitions of student engagement.

The most commonly accepted definition of student engagement is:

A multi-aspect construct that includes effort, resiliency, and persistence while facing obstacles (vigor), passion, inspiration, and pride in academic learning (dedication), and involvement in learning activities and tasks (absorption) as the main facets of this construct. (Schaufeli et al. Citation2002)

A student’s positive social, cognitive, emotional, and behavioural investments made when interacting with their tertiary institution and its focal agents (such as peers, employees and the institution itself).

Antecedents to student engagement

The shaping role of expectations

Pre-tertiary expectations are an important determinant of students’ engagement with their tertiary experience, as Bryson, Hardy and Hand (Citation2009, 1) explain:

The conception of engagement encompasses the perceptions, expectations and experience of being a student and the construction of being a student.

… motivation to engage relates to their expectation of value outcomes

H1: Expectations are positively related to behavioural engagement

H2: Expectations are positively related to affective engagement

H3: Expectations are positively related to social engagement

H4: Expectations are positively related to cognitive engagement

The shaping role of involvement

Involvement is defined as the ‘perceived relevance … based on inherent needs, values, and interests’ (Zaichkowsky Citation1985, 342). Involvement motivates one’s attention and commitment to the relationship (Brodie et al. Citation2011; Kinard and Capella Citation2006; Pansari and Kumar Citation2017) before, during and after exchanges (Bowden Citation2009; Dessart, Veloutsou, and Morgan-Thomas Citation2015). Involvement is a strong driver of student engagement (Mahatmya et al. Citation2012; Skinner and Pitzer Citation2012; Trowler Citation2010). Students who are not merely involved, but actively and multidimensionally engaged, are more likely to benefit from favourable academic, social and personal outcomes from their university experience (Kuh et al. Citation2008). According to Hu, Ching, and Chao (Citation2012, 74) students;

… learn more when they are intensely involved in their education.

We therefore propose that;

H5: Involvement is positively related to behavioural engagement

H6: Involvement is positively related to affective engagement

H7: Involvement is positively related to social engagement

H8: Involvement is positively related to cognitive engagement

Conceptualising the four pillars of student engagement

Students may exhibit the four dimensions of engagement, namely behavioural, affective, social and cognitive simultaneously or in isolation. We address each of the dimensions of engagement in turn, next, before discussing their interrelationships with specific institutional and student success factors.

Behavioural engagement

The behavioural dimension of engagement is defined as the observable academic performance and participatory actions and activities (Dessart, Veloutsou, and Morgan-Thomas Citation2015; Schaufeli et al. Citation2002). Positive behavioural engagement is measured through observable academic performance including: student’s positive conduct; attendance; effort to stay on task; contribution; participation in class discussions; involvement in academic and co-curricular activities; time spent on work; and perseverance and resiliency when faced with challenging tasks (Kahu et al. Citation2015; Klem and Connell Citation2004). Behaviourally engaged students therefore exhibit proactive participatory behaviours through their involvement and participation in university life, and extracurricular citizenship activities (Ashkzari, Piryaei, and Kamelifar Citation2018). The behavioural dimension is the most frequently measured dimension within national barometers of the student experience (Kuh Citation2009; Zepke Citation2014).

Affective engagement

The affective dimension of engagement relates to the summative and enduring levels of emotions experienced by students and captures the degree of passion students feel towards the tertiary experience (Schaufeli et al. Citation2002; Bowden Citation2013). Affective engagement manifests through heightened levels of positive emotions during on campus and off campus activities, which may be demonstrated through happiness, pride, delight, enthusiasm, openness, joy, elation and curiosity (Klem and Connell Citation2004; Pekrun et al. Citation2002). Emotionally engaged students are able to identify the purpose and meaning behind their academic tasks, and social interactions (Schaufeli et al. Citation2002). D’Errico, Paciello, and Cerniglia (Citation2016) also found that within e-learning, achievement emotions vary by learning task. These positive emotions were also found to correlate with behavioural engagement (D’Errico et al. Citation2018). Despite being central to engagement, the emotional component of students’ experiences has largely been under researched in the literature (Askham Citation2008; Kahu Citation2013; Pekrun et al. Citation2002). However, emotions are closely linked with students’ learning, achievement, life satisfaction, and health (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia Citation2012). Feelings of optimism, pride, joy, and enthusiasm can create a sustained psychological investment in the tertiary experience that extends beyond university (Pekrun et al. Citation2002).

Social engagement

The social dimension of engagement considers the bonds of identification and belongingness formed between students and their peers, academic staff, administrative staff and other pertinent figures in their tertiary experience (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia Citation2012; Wentzel Citation2012). It generates feelings of inclusivity, belonging, purpose, socialisation and connection to the tertiary provider (Eldegwy, Elsharnouby, and Kortam Citation2018; Goodenow Citation1993; Krause and Coates Citation2008; Vivek et al. Citation2014). Within the classroom, social engagement is characterised by the ‘unwritten’ rules of the learning environment, such as cooperation, listening to others, attending class on time, and maintaining a balanced teacher–student power structure (Coates Citation2007; Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia Citation2012; Wentzel Citation2012). Outside the classroom, social engagement is displayed through students’ participation in community groups, study groups and student societies, where bonds are formed with others based on shared values, interests or purpose (Freeman, Anderman, and Jensen Citation2007; Wentzel Citation2012). Social engagement strengthens the sense of achievement students gain from their university experience (Finn and Zimmer Citation2012). Students who lack social engagement are more likely to experience loneliness, isolation (McIntyre et al. Citation2018) leading to reduced wellbeing (Hoffman et al. Citation2002; McIntyre et al. Citation2018).

Cognitive engagement

The cognitive dimension of engagement reflects the set of enduring and active mental states experienced with respect to focal objects of engagement (Vivek et al. Citation2014). This can include the level of positive attention and interest paid to tertiary communications, and time spent planning and organising academic pursuits (Zepke, Leach, and Butler Citation2010). Students that are cognitively engaged demonstrate an increased understanding of the value and importance of academic work through their perceptions, beliefs, thought processing and strategies employed during academic tasks (Ashkzari et al. Citation2018; Kahu Citation2013). As such, cognitively engaged students are more likely to demonstrate higher order thinking given their ability to be cognisant of the content, meaning and application of academic tasks (Christenson, Reschly, and Wylie Citation2012; Kuh et al. Citation2006). The following section explores the consequences of student engagement for specific student success factors.

The outcomes of student engagement

Institutional reputation

Institutional reputation is defined as ‘the overall perception … what it stands for, what it is associated with and what individuals may expect’ (Helgesen and Nesset Citation2007, 42). From a strategic perspective, a positive reputation can: increase profitability, improve perceptions of trustworthiness, reputability, honesty and quality (Alan, Kabadayi, and Cavdar Citation2018; Robinson et al. Citation2018; Selnes Citation1998; Sung and Yang Citation2008). A high-quality reputation can also positively frame pre-tertiary experiences through students’ feelings of belonging, pride, trust and interest towards the institution (Sung and Yang Citation2008). Importantly creating a positive institutional image generates a ‘halo’ effect extending to prospective students and employees, and future industry partners (Alan, Kabadayi, and Cavdar Citation2018). Engaged students are more willing to advocate as unofficial ‘spokespersons’ (Bowden Citation2011; Kahu Citation2013; Krause and Coates Citation2008) and this in turn creates more trustworthy perceptions of an institution (Beerli Palacio, Díaz Meneses, and Pérez Citation2002; Harrison-Walker Citation2001). Therefore, we propose that;

H9: Behavioural engagement is positively related to reputation

H10: Affective engagement is positively related to reputation

H11: Social engagement is positively related to reputation

H12: Cognitive engagement is positively related to reputation

Student wellbeing

In addition to traditional success factors such as institutional reputation, the tertiary experience can have an enhancing effect on students’ lives through enhanced wellbeing (Christenson, Reschly, and Wylie Citation2012). Wellbeing is defined by Field (Citation2009, 9) as:

A dynamic state, in which the individual is able to develop their potential, work productively and creatively, build strong and positive relationships with others, and contribute to their community. It is enhanced when an individual is able to fulfil their personal and social goals and achieve a sense of purpose in society.

H13: Behavioural engagement is positively related to wellbeing

H14: Affective engagement is positively related to wellbeing

H15: Social engagement is positively related to wellbeing

H16: Cognitive engagement is positively related to wellbeing

Transformative learning

Transformative learning aggregates how a student’s social and academic experiences during university impact their view of;

… themselves, the campus, the community, and the world as a whole. (Zwart Citation2009, 86)

H17: Behavioural engagement is positively related to transformative learning

H18: Affective engagement is positively related to transformative learning

H19: Social engagement is positively related to transformative learning

H20: Cognitive engagement is positively related to transformative learning

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is defined as ‘beliefs in one’s capabilities to mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources, and courses of action needed to meet given situational demands’ (Wood and Bandura Citation1989, 408). Engaged students are more likely to persevere through academic challenge, which results in higher self-belief (Chipchase et al. Citation2017; Kuh Citation2001; Schaufeli et al. Citation2002). Students appraise their level of self-efficacy based on; their personal beliefs (thoughts); actual performance; interactions with others, including peers and teachers’ persuasions or discouragement; physiological reactions; and environmental conditions (Chipchase et al. Citation2017; Gist and Mitchell Citation1992). Engaging and supportive tertiary environments that facilitate ‘mastery experiences’, opportunities for new ways of thinking, and opportunities for social connection and modelling enhance student self-efficacy and aid in positive self-belief (Chemers, Hu, and Garcia Citation2001; Gist and Mitchell Citation1992). Therefore, we posit that;

H21: Behavioural engagement is positively related to self-efficacy

H22: Affective engagement is positively related to self-efficacy

H23: Social engagement is positively related to self-efficacy

H24: Cognitive engagement is positively related to self-efficacy

Self-esteem

Self-esteem is defined as ‘a global personal judgment of worthiness that appears to form relatively early in the course of development, remains fairly constant over time, and is resistant to change’ (Campbell Citation1990, 539). It includes perceptions of; pride; control; success; efficacy; social respect and acceptance; teacher approval; and confidence in their ability to meet clear goals during tertiary study and beyond degree completion (Heatherton and Polivy Citation1991). Students’ who are intrinsically motivated to complete academic activities report higher levels of self-esteem compared with extrinsically motivated students who are ‘going through the motions’ (Shernoff et al. Citation2016). In order to have intrinsic motivation, students must be cognisant of the value, meaning and relevance of their tertiary experience, which is generated through affective, social, cognitive and behavioural forms of engagement (Khademi Ashkzari, Piryaei, and Kamelifar Citation2018; Kahu Citation2013). We propose that;

H25: Behavioural engagement is positively related to self-esteem

H26: Affective engagement is positively related to self-esteem

H27: Social engagement is positively related to self-esteem

H28: Cognitive engagement is positively related to self-esteem

Research methodology

A questionnaire was designed adapting well-accepted scales to measure the model constructs. Data was collected from students enrolled in the Business Faculty of one top ten ranked major metropolitan University in Australia. The specific Faculty has an approximate enrolment of 17, 000 students, and contains a broad range of disciplines. A sample of 952 respondents was collected from the Business school. The sample drawn for this study was broadly representative of the profile of the institution from which it was drawn. The institution has five Faculties namely, Business, Arts, Human Sciences, Medicine, and Science of which Business is proportionally the largest in terms of student enrolments. In 2018 the institution had total student enrolments of 44, 558 students enrolled comprised of 32, 115 (full time) and 12, 443 (part time) in 2018. A total of 51% of students enrolled were male, and 48% female. Domestic students accounted for 73% of the total enrolment. The Australian Higher Education sector in the first half of 2018 had a total enrolment of 1, 332, 822 students; 44% were male, 55% were female; 74% were enrolled full time and 25% part time; 71% were domestic students and 28% international (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018). provides further details on the sampling frame. The questionnaire contained 11 constructs as identified in .

Table 2. Demographic profile.

Table 3. Scales to measure constructs.

The hypotheses were tested using a two-step structural equation modelling method (Anderson and Gerbing Citation1988). The psychometric properties of each measure were tested through CFA using AMOS 25. Analysis of the measurement model showed a good fit to the data: χ2 (2481); df = 764; p = .00; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.938; Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = 0.93; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.049; standardised root square mean residual [SRMR] = 0.05. Convergent validity was established for all scales used in this study. All standardised loadings on all constructs exceed the 0.50 criterion and were significantly different from zero at the 1% level. In addition, the average variance extracted estimates demonstrated that the measurement scales accounted for a greater proportion of explained variance than measurement error as the AVE statistics were above the >0.50 criterion value. Discriminant validity was examined according to Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) stringent test to establish separation between latent constructs and it was established for all construct pairs.

Results

Hypotheses testing

A structural equation modelling approach was used to test research hypotheses. The model established an acceptable fit, with χ2 = 3323.93, (df = 790; p = .00), CFI = 0.91, NFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05. A total of 24 hypotheses were supported. Four specific hypotheses were not supported; cognitive engagement and student wellbeing (H16); self-efficacy (H24) and self-esteem (H28) and behavioural engagement (H17) and transformative learning as shown in .

Table 4. Results.

The effect of students’ expectations on the four dimensions of engagement was of a moderate magnitude (β = 0.21–0.31, p = 000) suggesting that expectations are an important precursor to the development of engagement. Similarly, the effect of student involvement on the dimensions of engagement was moderate and even (β = 0.21–27, p = 000) across the elements of engagement except for affective engagement, for which it was found to be a strong driver (β = 0.51, p = 000). Thus, both expectations and involvement were found to both be important determinants of the development of holistic engagement.

Affective engagement was identified as the primary determinant of institutional reputation including students’ perceptions of its trustworthiness, and their willingness to recommend it to others (β = 0.46, p = 000). Affective commitment was also found to be the strongest determinant of student wellbeing (β = 0.40, p = 000), and transformative learning (β = 0.30, p = 000). The relationship between affective commitment and these success factors was stronger than the effect of social, cognitive and behavioural engagement. Conversely, behavioural engagement was found to be the primary and strong determinant of students’ self-esteem (e.g. confidence) (β = 0.49, p = 000) and self-efficacy (e.g. problem-solving ability and ability to manage challenges) (β = 0.58, p = 000). The results for social engagement suggest that it has a significant but weak impact upon student success and institutional success (β = 0.14–0.29, p = 000). Cognitive engagement was found to be a necessary, but not sufficient condition for institutional and student success. It had a significant but weak effect upon the establishment of institutional reputation (β = 0.09, p = 000) and transformative learning (β = 0.10, p = 000).

A comparative rival model was also developed and tested to examine whether or not the multi-dimensional holistic model of student engagement was a stronger conceptualisation and measurement approach to capturing student engagement than existing barometers. The competing model utilised the ‘learner engagement’ dimension and scales from the Australian Student Experience Survey, a national barometer measuring the student experience and a part of the Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) survey program. These items captured the extent to which students felt a sense of belonging, prepared, and participated in tertiary life. The rival model results demonstrated poor goodness of fit (RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.847; TLI = 0.838, p = 000).

Theoretical implications

Our findings form the basis of a revised holistic measurement approach for student engagement that accounts for the complexity of the dimensions of engagement; the multifaceted nature of the elements that constitute its process; as well as the differential effects that the dimensions of engagement have on key institutional and student success outcomes. It advances our current understandings of student engagement by firstly, attempting to empirically measure the pillars of engagement and by secondly, assessing their relative impact on key student and institutional success factors.

Firstly, the revised measurement approach to conceptualising and capturing student engagement advances current conceptualisations of engagement by underlining the importance higher education as a transformative experience (Rosenbaum et al. Citation2011, 5). Tertiary education serves several fundamental roles in that it shapes not only academic and career outcomes for students, but it also supports, fosters and develops students’ sense of self and identity (Anderson et al. Citation2013). Our study also supports the importance of the tertiary experience in shaping student wellbeing including their overall life satisfaction, and their emotional, social, financial, psychological, physical wellbeing. This is an important finding since individual wellbeing impacts upon collective societal wellbeing – in turn strengthening social networks, communities, neighbourhoods, cities and nations (Anderson et al. Citation2013). Lizzio and Wilson (Citation2009, 70) support this broader societal level impact noting that student engagement: can also be understood as part of the emerging and related discourses of education for democracy and ‘universities as sites of citizenship.’

Secondly, this study has argued that student engagement needs to expand from conceptualisations that focus at the individual level on singular dimensions of student engagement in isolation, to examine the way in which the dimensions of engagement operate interdependently to shape student and institutional success outcomes (Reschly and Christenson Citation2012). This more holistic conceptualisation of engagement captures the deeper and more systemic effects that tertiary education has upon the lives of students and their experience of the tertiary environment (Kuh et al. Citation2006). This measurement approach also emphasises that models of engagement should incorporate the initiating and seeding role of pre-tertiary expectations and involvement, and the ways in which these factors act to precondition students’ propensities for positive student engagement. These antecedents act as continual reference points throughout the student experience; they directly impact upon the four dimensions of engagement shaping the extent to which students experience emotional, behavioural, cognitive and social engagement; and through these dimensions, they ultimately impact upon student and institutional success. Together we argue that the affective, social, cognitive and behavioural dimensions of engagement identified in this study, comprise the four pillars of tertiary student engagement. They are closely interrelated and when integrated effectively, they constitute critical success factors for tertiary institutions seeking to facilitate and enhance engagement opportunities. We propose that these four dimensions, when measured together, comprise an invisible tapestry of student engagement. They are closely interrelated and when stitched together and constitute critical factors for institutional and student success.

Thirdly this study advances the student engagement literature by examining how the four pillars of student engagement differentially impact upon student and institutional success. We find that students can be variably engaged across one or more of the dimensions, and that these dimensions have varying impacts upon the extent to which institutions can build a positive reputation, and support students in their transformative learning, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and personal wellbeing. We propose that each dimension contributes to enhanced engagement and a more profound and transformative tertiary experience which fostered positive dynamic and value-creating interactions and created rich opportunities for learning, sense-making, and proactive learning (Bensimon Citation2007). However, within our specific study context, we find that the most important dimensions for institutional measurement and monitoring were those of affective and behavioural engagement. Affective engagement through positive feelings and emotions, supported students’ sense of wellbeing and transformative learning. Students’ feelings of happiness, pride, delight, enthusiasm, openness, joy, elation and curiosity led to the establishment of a strong institutional reputation as indicated through positive referral and retention. Behavioural engagement empowered students to develop a strong sense of self-esteem and self-efficacy. This subsequently strengthened their sense of competence and enhanced their perceived work-readiness. The next section discusses the implications of these findings for tertiary practice.

Managerial implications

Involvement was identified as a positive antecedent of student engagement, reinforcing the importance of framing university as interesting, relevant, inspiring and meaningful. Involvement was the strongest driver of affective engagement, suggesting that highly involved students are more likely to feel happiness, pride and enthusiasm towards their institution. The development of collaborative partnerships between students and the institution prior to enrolment, and during enrolment in particular can facilitate engagement and reinforce feelings of attachment and commitment which help prevent students from becoming withdrawn and disengaged.

As an antecedent, expectations also positively shaped student engagement, highlighting the importance of understanding pre-tertiary expectations, especially given the heighted perceptions of risk and ambiguity that surround institutional selection for prospective students. Expectations start to influence engagement before students enrol and remain an important anchor for ongoing quality judgements of the tertiary experience. Expectations had the strongest impact on students’ affective engagement. This may be because when students’ expectations are exceeded, they are likely to experience positive feelings of surprise, delight and happiness. Understanding, monitoring and measuring the multi-focal sources, drivers and characteristics of these pre-tertiary expectations in relationship to the dimensions of engagement is essential to proactively shaping the student-institution relationship.

With regard to the four dimensions of student engagement, affective engagement was the primary determinant of institutional reputation, student well-being and transformative learning. The emotional connections students form with and among staff, peers, and the campus and institution at large establishes a superordinate goal, creates a positive perception of the institution, provides a heighten sense of well-being and facilitates transformative learning experiences. Tertiary institutions that facilitate emotional connectivity are more likely to be rewarded via student advocacy and recommendation enhancing institutional reputation. In addition, meaningful community participation enhances students’ sense of inclusion and ownership over their tertiary journey, and this generates positive feelings of pride which improves student wellbeing. Lastly, when students are emotionally engaged, they are more likely to be receptive to others’ ideas, opinions and, are more malleable in their own beliefs and perceptions enhancing transformative learning.

Emotional connection can be further enhanced at the strategic level through institutional ‘place identification’ communication strategies which use highly emotive and personalised imagery drawing upon students lived experiences, successes and achievements, memories and connections to the institution, their transformative growth, and careers. These approaches celebrate collective success and can be used to demonstrate that every student can have a personal victory during their tertiary pursuit. Emotional connection can also be facilitated through pre-tertiary connection through ‘relationship seeding’ initiatives such as by giving students a voice and allowing them to express their interests and strengths in personal statements prior to enrolment. Institutions can respond to these with personalised communications which provide future students with increased awareness of ‘connection’ points through institutional activities and events; and opportunities to emotionally connect to the institution and to others through membership. These approaches knit individual experiences into the collective core of institutional belonging, facilitate pride and passion, support ambitions and foster a collective, connected and unified emotional identity.

Our findings concerning the pivotal role of behavioural engagement on the remaining two student success dimensions of self-esteem and self-efficacy affirm the importance of the more functional dimensions of engagement. The findings point to the need for institutions to continue to facilitate opportunities for and monitor indicators of behavioural engagement such as participation in campus life; attendance (or view rates in digital environs); effort to stay on task; contribution; participation in class discussions; involvement in academic and co-curricular activities; time spent on work; and perseverance and resiliency when faced with challenging tasks.

Behavioural engagement was found to strongly drive students’ sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem, reinforcing student’s belief in their ability to achieve goals, and create positive evaluations of self-worth. As such, this dimension reflects the autonomous aspects of university in the achievement of personal goals. The strong relationship between behavioural engagement and self-efficacy is not surprising, as students largely appraise self-efficacy based on their performance on academic tasks. Therefore, students who dedicate appropriate time to mastering skills and tackling tertiary learning demands with a motivation to succeed are more likely to report higher levels of self-efficacy, career-readiness and employability.

Behavioural engagement can be further enhanced through fostering an organisational culture that aims to encourage students’ effort, persistence, reliance and achievement at all student touchpoints (i.e. in the classroom, on online platforms, on campus). It may also be enhanced through positioning academic tasks, coursework and involvement in extra-curricular activities as a series of positive and worthwhile ‘challenges’ to be tackled that will provide life-long skills. An institutional vision that focuses on positioning the tertiary experience as an opportunity for personal growth and development, alongside other outcomes such as grades and GPA’s is essential.

Perhaps somewhat surprising in nature, cognitive engagement, that is students’ intensity of immersion in their educational experience was found to be much weaker and more diffuse in its impact on engagement. In this sense, it is a necessary but not sufficient condition for holistic engagement. Cognitive engagement operates as a core requirement of the tertiary journey however, this study suggests that it does not provide for the key point of differentiation within the student experience. Cognitive engagement should of course continue to be prioritised given its core role in the tertiary experience and given that graduates become the workforce of the future. Strategies to enhance this dimension should focus on enhancing students’ ambitions through transformative learning experiences, and developing their knowledge, enterprise, collaborative, and employability competencies and skill sets. Institutions should focus on inspiring agency for all students and giving access to knowledge advancement for all students.

Social engagement, which reflects the bonds of identification and belongingness formed between students, staff and the broader tertiary experience, was found to be a weak determinant of institutional and student success. Nonetheless, social connection is a necessary element of holistic student engagement. Social engagement can create more inclusive campus environments, as it fosters equality between teachers and students, and helps relax the hierarchical relationships stemming from the often perceived ‘ivory tower’ effect of academic culture. The very act of engaging students from a relational perspective builds trust, confidence and empowerment and fosters positive and proactive habits of mind and heart that facilitate continuous learning, personal growth and development, and increased educational and emotional commitment. It is important to recognise that social engagement does not merely begin at ‘enrolment on-boarding’. It commences with pre-connection, buy in and empowerment of the student voice during the upper years of secondary school, is enhanced through the tertiary experience, and continues post-tertiary as students aspire to and achieve their career goals.

For the recommendations of this study to be implemented effectively they will need to be adapted to fit with the institution’s strategic vision for student engagement and connected communities. They will also need to be tailored to fit with other potentially competing priorities. If, as is commonly the case, institutional research is identified as a top tier priority, then this may leave students questioning their level of (de)prioritisation by the institution. In light of this potential perception it is important to reinforce an institution-wide understanding that students inherently experience research through teaching and engagement with the broader campus culture and that a student-centric vision is required.

This study represents a preliminary attempt to develop a holistic metric approach to student engagement. Certainly, further research addressing the complexities of student engagement and its effects will be needed to explore more deeply the way in which engagement operates. Future research should examine the extent to which the metric approach and results are generalisable across different segments of students, from low to high SES, domestic and international students, undergraduate and postgraduate students; different Faculties within institutions; as well as across cross-cultural contexts. It should also examine expressions of both positive and negative valences of engagement across various cohorts such as young learners, adult learners, and online and offline modes of teaching delivery and their relationship to the specific student success and institutional success factors identified. This research should also attempt to examine the way in which specific attributes of the tertiary experience contribute to the four global dimensions of engagement.

Importantly, any metric approaches and subsequent policies developed to support student engagement and ultimately student success must necessarily incorporate a top-down supported systematic quality assurance programme with monitoring and measuring milestones to ensure that holistic student engagement is realised. Put simply, institutions cannot simply expect students to engage themselves. Rather, the onus is on institutions to understand the determinants of engagement, and to then proactively translate this understanding into effective ‘experience design’ which fosters the conditions that allow diverse student populations to mutually interact and engage;

Most institutions can do far more than they are doing at present to implement interventions that will change the way students approach college and what they do after they arrive. The real question is whether we have the will to more consistently use what we know to be promising policies and effective educational practices in order to increase the odds that more students get ready, get in, and get through.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Alan, A. K., E. T. Kabadayi, and N. Cavdar. 2018. “Beyond Obvious Behaviour Patterns in Universities: Student Engagement With University.” Research Journal of Business and Management 5 (3): 222–230.

- Anderson, J. C., and D. W. Gerbing. 1988. “Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-step Approach.” Psychological bulletin, 103 (3): 411.

- Anderson, L., A. L. Ostrom, C. Corus, R. P. Fisk, A. S. Gallan, M. Giraldo, M. Mende, M. Mulder, S. W. Rayburn, and M. S. Rosenbaum. 2013. “Transformative Service Research: An Agenda for the Future.” Journal of Business Research 66 (8): 1203–1210.

- Artess, J., R. Mellors-Bourne, and T. Hooley. 2017. Employability: A Review of the Literature 2012–2016. York: Higher Education Academy.

- Askham, P. 2008. “Context and Identity: Exploring Adult Learners' Experiences of Higher Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 32 (1): 85–97.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Selected Higher Education Statistics – 2018 Student Data. Australian Government Department of Education. https://www.education.gov.au/selected-higher-education-statistics-2018-student-data.

- Barnacle, R., and G. Dall’Alba. 2017. “Committed to Learn: Student Engagement and Care in Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 36 (7): 1326–1338.

- Bartikowski, B., and S. Llosa. 2004. “Customer Satisfaction Measurement: Comparing Four Methods of Attribute Categorisations.” The Service Industries Journal 24 (4): 67–82.

- Beerli Palacio, A., G. Díaz Meneses, and P. J. Pérez. 2002. “The Configuration of the University Image and its Relationship With the Satisfaction of Students.” Journal of Educational Administration 40 (5): 486–505.

- Bensimon, E. M. 2007. “The Underestimated Significance of Practitioner Knowledge in the Scholarship on Student Success.”The Review of Higher Education 30 (4): 441–469.

- Berry, L. L. 1995. “Relationship Marketing of Services—Growing Interest, Emerging Perspectives.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23 (4): 236–245.

- Bowden, J. L. H. 2009. “The Process of Customer Engagement: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 17 (1): 63–74.

- Bowden, J. L. H. 2011. “Engaging the Student as a Customer: A Relationship Marketing Approach.” Marketing Education Review 21 (3): 211–228.

- Bowden, J. L. H. 2013. “What’s in a Relationship.” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 25 (3): 428–451.

- Bowden, J. L. H., J. Conduit, L. D. Hollebeek, V. Luoma-Aho, and B. A. Solem. 2017. “Engagement Valence Duality and Spillover Effects in Online Brand Communities.” Journal of Service Theory and Practice 27 (4): 877–897.

- Brock, S. E. 2010. “Measuring the Importance of Precursor Steps to Transformative Learning.” Adult Education Quarterly 60 (2): 122–142.

- Brodie, R. J., L. D. Hollebeek, B. Jurić, and A. Ilić. 2011. “Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research.” Journal of Service Research 14 (3): 252–271.

- Brown, R. M., and T. W. Mazzarol. 2009. “The Importance of Institutional Image to Student Satisfaction and Loyalty within Higher Education.” Higher education 58 (1): 81–95.

- Bryson, C., C. Hardy, and L. Hand. 2009. “Student Expectations of Higher Education.” Learning and Teaching Update: Innovation and Excellence in the Classroom 27: 4–6.

- Campbell, J. D. 1990. “Self-Esteem and Clarity of the Self-Concept.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59 (3): 538–549.

- Chemers, M. M., L. Hu, and B. F. Garcia. 2001. “Academic Self-Efficacy and First Year College Student Performance and Adjustment.” Journal of Educational Psychology 93 (1): 55–64.

- Chipchase, L., M. Davidson, F. Blackstock, R. Bye, P. Colthier, N. Krupp, W. Dickson, D. Turner, and M. Williams. 2017. “Conceptualising and Measuring Student Disengagement in Higher Education: A Synthesis of the Literature.” International Journal of Higher Education 6 (2): 31–42.

- Christenson, S. L., A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie, eds. 2012. Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Coates, H. 2007. “A Model of Online and General Campus-Based Student Engagement.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 32 (2): 121–141.

- Crisp, G., E. Palmer, D. Turnbull, T. Nettelbeck, L. Ward, A. LeCouteur, A. Sarris, P. Strelan, and L. Schneider. 2009. “First Year Student Expectations: Results from a University-Wide Student Survey.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 6 (1): 11–26.

- De Carolis, B., F. D’Errico, M. Paciello, and G. Palestra. 2019. “Cognitive Emotions Recognition in E-Learning: Exploring the Role of Age Differences and Personality Traits.” In International Conference in Methodologies and Intelligent Systems for Technology Enhanced Learning, 97–104. Cham: Springer.

- D’Errico, F., M. Paciello, and L. Cerniglia. 2016. “When Emotions Enhance Students’ Engagement in E-Learning Processes.” Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society 12 (4): 9–23.

- D’Errico, F., M. Paciello, B. De Carolis, A. Vattani, G. Palestra, and G. Anzivino. 2018. “Cognitive Emotions in E-Learning Processes and Their Potential Relationship with Students’ Academic Adjustment.” International Journal of Emotional Education 10 (1): 89–111.

- Dessart, L., C. Veloutsou, and A. Morgan-Thomas. 2015. “Consumer Engagement in Online Brand Communities: A Social Media Perspective.” Journal of Product & Brand Management 24 (1): 28–42.

- Dewey, J. 1938 [1997]. Experience and Education. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Dill, D. 2007. Quality Assurance in Higher Education: Practices and Issues. Edited by Chief Barry McGaw, Eva Baker, and Penelope P. Peterson. Chapel Hill, NC: Elsevier.

- Eggens, L., M. Van der Werf, and R. Bosker. 2008. “The Influence of Personal Networks and Social Support on Study Attainment of Students in University Education.” Higher Education 55 (5): 553–573.

- Eldegwy, A., T. H. Elsharnouby, and W. Kortam. 2018. “How Sociable is Your University Brand? An Empirical Investigation of University Social Augmenters’ Brand Equity.” International Journal of Educational Management 32 (5): 912–930.

- Field, J. 2009. Well-Being and Happiness: Inquiry Into the Future of Lifelong Learning. (Thematic Paper 4). Leicester: National Institute of Adult Continuing Education.

- Finn, J. D., and K. S. Zimmer. 2012. “Student Engagement: What Is It? Why Does It Matter?” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, 97–131. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models With Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50.

- Fredricks, J., P. Blumenfeld, and A. Paris. 2004. “School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence.” Review of Educational Research 74 (1): 59–109.

- Fredricks, J. A., and W. McColskey. 2012. “The Measurement of Student Engagement: A Comparative Analysis of Various Methods and Student Self-Report Instruments.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, 763–782. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Freeman, T. M., L. H. Anderman, and J. M. Jensen. 2007. “Sense of Belonging in College Freshmen at the Classroom and Campus Levels.” The Journal of Experimental Education 75 (3): 203–220.

- Giese, J. L., and J. A. Cote. 2000. “Defining Consumer Satisfaction.” Academy of Marketing Science Review 1 (1): 1–22.

- Gist, M. E., and T. R. Mitchell. 1992. “Self-Efficacy: A Theoretical Analysis of its Determinants and Malleability.” Academy of Management Review 17 (2): 183–211.

- Goodenow, C. 1993. “Classroom Belonging Among Early Adolescent Students: Relationships to Motivation and Achievement.” The Journal of Early Adolescence 13 (1): 21–43.

- Great Britain. Department for Business, Innovation and Skills UK (BIS). 2009. “Higher Ambitions: The Future of Universities in a Knowledge Economy.” https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:44742.

- Grebennikov, L., and M. Shah. 2013. “Student Voice: Using Qualitative Feedback from Students to Enhance Their University Experience.” Teaching in Higher Education 18 (6): 606–618.

- Gustafsson, A., M. D. Johnson, and I. Roos. 2005. “The Effects of Customer Satisfaction, Relationship Commitment Dimensions, and Triggers on Customer Retention.” Journal of Marketing 69 (4): 210–218.

- Harrison-Walker, L. J. 2001. “The Measurement of Word-of-Mouth Communication and an Investigation of Service Quality and Customer Commitment as Potential Antecedents.” Journal of Service Research 4 (1): 60–75.

- Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2014. Engagement Through Partnership: Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. York: Higher Education Academy.

- Heatherton, T. F., and J. Polivy. 1991. “Development and Validation of a Scale for Measuring State Self-Esteem.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60 (6): 895–910.

- Helgesen, Ø., and E. Nesset. 2007. “Images, Satisfaction and Antecedents: Drivers of Student Loyalty? A Case Study of a Norwegian University College.” Corporate Reputation Review 10 (1): 38–59.

- Hoffman, M., J. Richmond, J. Morrow, and K. Salomone. 2002. “Investigating “Sense of Belonging” in First-Year College Students.” Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 4 (3): 227–256.

- Hollebeek, L. D., M. S. Glynn, and R. J. Brodie. 2014. “Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 28 (2): 149–165.

- Hu, Y. L., G. S. Ching, and P. C. Chao. 2012. “Taiwan Student Engagement Model: Conceptual Framework and Overview of Psychometric Properties.” International Journal of Research Studies in Education 1 (1): 69–90.

- Jaakkola, E., and M. Alexander. 2014. “The Role of Customer Engagement Behavior in Value Co-creation: A Service System Perspective.” Journal of service research 17 (3): 247–261.

- Johnson, D. R., M. Soldner, J. B. Leonard, P. Alvarez, K. K. Inkelas, H. T. Rowan-Kenyon, and S. D. Longerbeam. 2007. “Examining Sense of Belonging Among First-Year Undergraduates from Different Racial/Ethnic Groups.” Journal of College Student Development 48 (5): 525–542.

- Junco, R. 2012. “The Relationship Between Frequency of Facebook Use, Participation in Facebook Activities, and Student Engagement.” Computers & Education 58 (1): 162–171.

- Kahu, E. R. 2013. “Framing Student Engagement in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (5): 758–773.

- Kahu, E. R., and K. Nelson. 2018. “Student Engagement in the Educational Interface: Understanding the Mechanisms of Student Success.” Higher Education Research & Development 37 (1): 58–71.

- Kahu, E., C. Stephens, L. Leach, and N. Zepke. 2015. “Linking Academic Emotions and Student Engagement: Mature-Aged Distance Students’ Transition to University.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 39 (4): 481–497.

- Khademi Ashkzari, M., S. Piryaei, and L. Kamelifar. 2018. “Designing a Causal Model for Fostering Academic Engagement and Verification of its Effect on Educational Performance.” International Journal of Psychology (IPA) 12 (1): 136–161.

- Kinard, B. R., and M. L. Capella. 2006. “Relationship Marketing: The Influence of Consumer Involvement on Perceived Service Benefits.” Journal of Services Marketing 20 (6): 359–368.

- Klem, A. M., and J. P. Connell. 2004. “Relationships Matter: Linking Teacher Support to Student Engagement and Achievement.” Journal of School Health 74 (7): 262–273.

- Krause, K. L., and H. Coates. 2008. “Students’ Engagement in First-Year University.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 33 (5): 493–505.

- Kuh, G. D. 2001. “Assessing What Really Matters to Student Learning Inside the National Survey of Student Engagement.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 33 (3): 10–17.

- Kuh, G. D. 2003. “What we're Learning about Student Engagement from NSSE: Benchmarks for Effective Educational Practices.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 35 (2): 24–32.

- Kuh, G. D. 2009. “What Student Affairs Professionals Need to Know About Student Engagement.” Journal of college student development 50 (6): 683–706.

- Kuh, G. D., T. M. Cruce, R. Shoup, J. Kinzie, and R. M. Gonyea. 2008. “Unmasking the Effects of Student Engagement on First-Year College Grades and Persistence.” The Journal of Higher Education 79 (5): 540–563.

- Kuh, G. D., J. L. Kinzie, J. A. Buckley, B. K. Bridges, and J. C. Hayek. 2006. What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature Volume 8. Washington, DC: National Postsecondary Education Cooperative.

- Lizzio, A., and K. Wilson. 2009. “Student Participation in University Governance: The Role Conceptions and Sense of Efficacy of Student Representatives on Departmental Committees.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (1): 69–84.

- Machell, J., and M. Saunders. 2007. An Exploratory Evaluation of the Use of the National Student Survey (NSS) Results Dissemination Website. York: The Higher Education Academy.

- Mahatmya, D., B. J. Lohman, J. L. Matjasko, and A. F. Farb. 2012. “Engagement Across Developmental Periods.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, edited by S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie, 45–63. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media.

- McIntyre, J. C., J. Worsley, R. Corcoran, P. Harrison Woods, and R. P. Bentall. 2018. “Academic and Non-Academic Predictors of Student Psychological Distress: The Role of Social Identity and Loneliness.” Journal of Mental Health 27 (3): 230–239.

- Merriam, S. B. 2004. “The Role of Cognitive Development in Mezirow’s Transformational Learning Theory.” Adult Education Quarterly 55 (1): 60–68.

- O'Keeffe, P. 2013. “A Sense of Belonging: Improving Student Retention.” College Student Journal 47 (4): 605–613.

- O’Keefe, M., T. Burgess, S. McAllister, and I. Stupans. 2012. “Twelve Tips for Supporting Student Learning in Multidisciplinary Clinical Placements.” Medical Teacher 34 (11): 883–887.

- Oliver, R. L. 1980. “A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions.” Journal of Marketing Research 17 (4): 460–469.

- Pansari, A., and V. Kumar. 2017. “Customer Engagement: The Construct, Antecedents, and Consequences.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 45 (3): 294–311.

- Pekrun, R., T. Gotz, W. Titz, and R. Perry. 2002. “Positive Emotions in Education.” In Beyond Coping: Meeting Goals, Visions, and Challenges, edited by E. Frydenberg, 149–173. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pekrun, R., and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia. 2012. “Academic Emotions and Student Engagement.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, 259–282. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Reschly, A., and S. Christenson. 2012. “Jingle, Jangle, and Conceptual Haziness: Evolution and Future Directions of the Engagement Construct.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, edited by S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Robinson, C. D., M. G. Lee, E. Dearing, and T. Rogers. 2018. “Reducing Student Absenteeism in the Early Grades by Targeting Parental Beliefs.” American Educational Research Journal 55 (6): 1163–1192.

- Rosenbaum, M. S., C. Corus, A. L. Ostrom, L. Anderson, R. P. Fisk, A. S. Gallan, and S. W. Rayburn. 2011. “Conceptualization and Aspirations of Transformative Service Research.” Journal of Research for Consumers 19: 1–6.

- Russell, J. A. 1980. “A Circumplex Model of Affect.” Journal of personality and social psychology 39 (6): 1161–1178.

- Sabri, D. 2011. “What's Wrong with ‘The Student Experience’?.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (5): 657–667.

- Schwarzer, R., J. Bäßler, P. Kwiatek, K. Schröder, and J. X. Zhang. 1997. “The Assessment of Optimistic Self-beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese Versions of the General Self-efficacy Scale.” Applied Psychology 46 (1): 69–88.

- Schaufeli, W. B., M. Salanova, V. González-Romá, and A. B. Bakker. 2002. “The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach.” Journal of Happiness Studies 3 (1): 71–92.

- Selnes, F. 1998. “Antecedents and Consequences of Trust and Satisfaction in Buyer-Seller Relationships.” European Journal of Marketing 32 (3/4): 305–322.

- Shernoff, D. J., S. Kelly, S. M. Tonks, B. Anderson, R. F. Cavanagh, S. Sinha, and B. Abdi. 2016. “Student Engagement as a Function of Environmental Complexity in High School Classrooms.” Learning and Instruction 43: 52–60.

- Sirgy, M. J., D. J. Lee, S. Grzeskowiak, J. C. Chebat, J. S. Johar, A. Hermann, S. Hassan, I. Hegazy, A. Ekici, D. Webb, C. Su. 2008. “An Extension and Further Validation of a Community-based Consumer Well-being Measure.” Journal of Macromarketing 28 (3): 243–257.

- Skinner, E. A., and J. R. Pitzer. 2012. “Developmental Dynamics of Student Engagement, Coping, and Everyday Resilience.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, 21–44. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Strathdee, R. 2009. “Reputation in the Sociology of Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 30 (1): 83–96.

- Sung, M., and S. U. Yang. 2008. “Toward the Model of University Image: The Influence of Brand Personality, External Prestige, and Reputation.” Journal of Public Relations Research 20 (4): 357–376.

- Taylor, E. W. 2007. “An Update of Transformative Learning Theory: A Critical Review of the Empirical Research (1999–2005).” International Journal of Lifelong Education 26 (2): 173–191.

- Teas, R. K. 1981. “A Within-Subject Analysis of Valence Models of Job Preference and Anticipated Satisfaction.” Journal of Occupational Psychology 54 (2): 109–124.

- Trowler, V. 2010. “Student Engagement Literature Review.” The Higher Education Academy 11: 1–15.

- Veloutsou, C., and L. Moutinho. 2009. “Brand Relationships Through Brand Reputation and Brand Tribalism.” Journal of Business Research 62 (3): 314–322.

- Vivek, S. D., S. E. Beatty, V. Dalela, and R. M. Morgan. 2014. “A Generalized Multidimensional Scale for Measuring Customer Engagement.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 22 (4): 401–420.

- Wentzel, K. 2012. “Part III Commentary: Socio-Cultural Contexts, Social Competence, and Engagement at School.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, 479–488. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Wood, R., and A. Bandura. 1989. “Social Cognitive Theory of Organizational Management.” Academy of management Review 14 (3): 361–384.

- Zaichkowsky, J. L. 1985. “Measuring the Involvement Construct.” Journal of Consumer Research 12 (3): 341–352.

- Zepke, N. 2014. “Student Engagement Research in Higher Education: Questioning an Academic Orthodoxy.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (6): 697–708.

- Zepke, N., L. Leach, and P. Butler. 2010. “Engagement in Post-compulsory Education: Students' Motivation and Action.” Research in Post-Compulsory Education 15 (1): 1–17.

- Zepke, N., L. Leach, and P. Butler. 2014. “Student Engagement: Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions.” Higher Education Research & Development 33 (2): 386–398.

- Zwart, M. B. 2009. A Phenomenological Study of Students’ Perceptions of Engagement at a Midwestern Land Grant University. University of South Dakota. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2009. 3382637.