?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Temporary contracts are increasingly used in academia. This is a major concern for non-tenured researchers, since weak job security may hamper job satisfaction. This paper presents an empirical analysis of the role of academic tenure for job satisfaction of researchers in European countries. The work uses data from the MORE2 survey, a large-scale representative survey of researchers in all European countries. The results show that, ceteris paribus, academics with a permanent contract are on average more satisfied with their job than those that are employed on a temporary basis. We also show that academic tenure is a relatively more important factor of job satisfaction for researchers at an intermediate stage of the career. Finally, we point out some important differences in the working of the model among European countries.

1. Introduction

In many European countries, recent labour market reforms towards deregulation and flexibility of employment have led to an increasing use of temporary forms of contract. The academic labour market has also been affected by this trend, and temporary contracts are now increasingly used in HEIs in several countries, among which the Netherlands, Germany, the UK and the Nordic economies (Waaijer et al. Citation2017).

For many academic researchers throughout Europe, this is an issue of great concern. Younger and non-tenured academics often find it increasingly difficult to get a permanent job in academia in their own country, and they must therefore consider to migrate to another country, or leave academia altogether and get a job in another sector (Afonso Citation2016, 820; Brechelmacher et al. Citation2015; IDEA Consult Citation2013). Weaker job security and worsening career prospects have potentially important negative consequences for researchers’ job satisfaction and well-being (Waaijer et al. Citation2017).

In spite of the relevance of this topic, though, scholarly research on the effects of temporary employment on job satisfaction of researchers is scant. Empirical research in several other sectors of the economy suggests that weak job security is an important factor hampering work life satisfaction (Wilkin Citation2013). A few recent papers have started to explore this question for the academic sector, focusing for instance on the cases of the Netherlands, Spain and the UK (Escardíbul and Afcha Citation2017; Fontinha, van Laar, and Easton Citation2018; van der Weijden et al. Citation2016). However, research in this field does still lack comprehensive cross-country evidence on the effects of academic tenure on job satisfaction.Footnote1

Do permanent contracts contribute to support researchers’ well-being? This research question is not only important from the point of view of academic researchers, but it also have some relevant implications for the national public science system as a whole. In fact, if the increasing use of temporary forms of employment will end up weakening job security and worsening career prospects for non-tenured academics, many of these may well decide to leave academia and get a job somewhere else. If so, the public science system will progressively become a less attractive sector of employment for many young talents, and thus weaken its quality, performance and competitiveness in the longer run.

To investigate this question, we carry out an empirical analysis based on data from the MORE2 survey, a recent large-scale representative survey of researchers in all European countries. The dataset provides rich information on about 10,000 European researchers, thus enabling a comprehensive cross-country analysis of the relationships between job security and satisfaction in academia.

Our empirical analysis has three interrelated parts. First, we develop and test the hypothesis that permanent contracts are positively related to job satisfaction. Second, we ask whether this relationship varies along the life cycle, i.e. for academics that are at different stages of their career (which is a reasonable expectation according to the evidence previously presented by Albert, Davia, and Legazpe Citation2018; Bentley et al. Citation2013; Höhle and Teichler Citation2013; Locke and Bennion Citation2013). This part of the analysis shows that academic tenure is relatively more important for early and middle-aged academics, which is the age group for which stability and career prospects are particularly important in terms of academic achievements and personal / family life. Third, we investigate whether the tenure-satisfaction relationship varies across countries in Europe, and point out the existence of remarkable differences due to country specificities in academic traditions, career paths, and employment regulations among European economies (Bennion and Locke Citation2010; Enders and Teichler Citation1997).

The paper contributes to the important, but still limited, strand of research on job satisfaction in academia by focusing on one important unexplored dimension, academic tenure, which is a relevant topic of concern for researchers, but it has not yet received the scholarly attention it would deserve. Specifically, the paper contributes by presenting a cross-country empirical analysis based on a large representative sample of researchers, which is important due to the paucity of cross-country comparative studies on academic job satisfaction (Shin and Jung Citation2014). In fact, as noted by Bentley et al. (Citation2013), ‘most detailed former studies are single-country, often from the USA. (…) International studies have been limited to comparisons of descriptive results and mean levels of satisfaction, rather than exploring job satisfaction through a multivariate approach’ (Bentley et al. Citation2013, 240).

2. Literature and hypotheses

Research on job satisfaction has until now mostly focused on jobs in private organizations, and much less so in public institutions such as Universities and HEIs (Erdogan et al. Citation2012). As noted by de Lourdes Machado-Taylor et al. (Citation2016, 542), ‘the important area of academic staff job satisfaction is an under-researched subject in need of further discussion and documentation’.

Among recent research on job satisfaction in academia, several papers have carried out country-specific studies analysing the ‘Changing Academic Profession’ (CAP) survey. Locke and Bennion (Citation2013) focus on the UK, and point out differences in working conditions and job satisfaction for academic staff at different stages of the career (young, mature, older). Höhle and Teichler (Citation2013) analyse CAP data for Germany, providing a descriptive analysis of a broad variety of factors that affect well-being at work. Aarrevaara and Dobson (Citation2013) use CAP data for Finnish HEIs, emphasizing differences in working conditions between academics working in Universities and in Polytechnics.

Other country-specific studies made use of different data sources. Bender and Heywood (Citation2006) analyse the 1997 Survey of Doctorate Recipients, a large cross-sectional sample of PhD scientists (nearly 32,000 respondents) carried out in the US. The work focuses on gender differences, and it shows how these relate to tenure and wage differentials between male and female researchers. de Lourdes Machado-Taylor et al. (Citation2016) consider a sample of more than 4,500 academics in Portugal, highlighting a broad variety of factors that affect job satisfaction in academia. Escardíbul and Afcha (Citation2017) present an analysis of data from the Spanish Survey on Human Resources in Science and Technology (2009), focusing on differences between male and female PhD holders. Albert, Davia, and Legazpe (Citation2018), also analysing data for Spanish academics, point out that research productivity is an important factor that motivates researchers, and that is therefore associated with job satisfaction.

Cross-country comparative research on this topic is scant. Enders and Teichler (Citation1997) present an early study based on the results of the ‘International Survey of the Academic Profession’, comparing working conditions in HEIs in Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, England, Japan and US. More recently, Bentley et al. (Citation2013) make use of the CAP survey to compare job satisfaction patterns in 12 countries. The empirical study, based on a large sample of 13,400 academics, shows that researchers’ perception of their own well-being at work is affected by different types of antecedents previously pointed out by Hagedorn (Citation2000), and in particular motivators, demographic variables, environmental variables and trigger factors. Finally, Shin and Jung (Citation2014) present a comparative study of job satisfaction and job stress across 19 countries, also based on the CAP survey, and it points out that managerial reforms in HEIs are on the whole worsening working conditions and increasing job stress in academia.

2.1. Permanent contracts and job satisfaction

An important factor that has until now received very limited attention relates to the role of permanent contracts in academia (see the online appendix A1 of this paper for a definition and brief discussion of this type of labour contract). Several studies have examined the relevance of job security in private sector occupations, and Wilkin (Citation2013) presents a comprehensive meta-analytic review of the effects of temporary work on job satisfaction. The survey points out that temporary workers report on average lower well-being than permanent employees, and it explains this pattern in the light of social comparison theory, i.e. arguing that temporary workers are less satisfied at work because they compare themselves to their colleagues with a permanent contract.

In academia, temporary contracts have increasingly been used in the last few years. However, only a limited number of studies have examined the consequences of this important trend for researchers’ job satisfaction. Escardíbul and Afcha (Citation2017) analyse data for a large representative sample of PhD holders in Spain and find, among other results, a positive and significant correlation between academic tenure and job satisfaction. Waaijer et al. (Citation2017) present a study on the effects of temporary employment on job satisfaction in a large sample of recent PhD graduates (over 1,000 respondents) in the Netherlands. van der Weijden et al. (Citation2016)’s work presents the results of a recent survey carried out in the Netherland showing that low career prospects for postdoctoral researchers are related to job dissatisfaction. In a recent study, Fontinha, van Laar, and Easton (Citation2018) point out that contract type is an important factor that moderates the effects of other work characteristics on job satisfaction.

In line with these recent works, the main hypothesis developed in this paper is that permanent contracts are important for job satisfaction of academic researchers. This proposition is based on three arguments. First, academic tenure gives researchers more stability and job security, thus reducing uncertainty about the future. This makes it possible for scientists to plan career steps and future work, setting up priorities and focusing on activities that are considered more relevant and more interesting – and hence more rewarding in terms of job satisfaction. On the other hand, temporary positions make employees more dependent on ‘psychological contracts’ with their employers (Fontinha, van Laar, and Easton Citation2018; Waaijer et al. Citation2017). When such psychological contracts are violated, the employee feels her expectations have not been met, and this typically leads to dissatisfaction with the job (Lam and de Campos Citation2015; Robinson and Rousseau Citation1994). Second, in line with social comparison theory, researchers often compare their performance and achievements with those of their peers, and such social comparisons represent an important source of (dis)satisfaction (Clark and Oswald Citation1996). However, it is reasonable to argue that tenured employees will be less exposed to such comparison effects (because their job security is not affected by their peers’ performance), whereas temporary workers are more vulnerable in this respect (as their colleagues’ performance may have implications for their chances to get a permanent job in the future). Third, temporary employment will not only have negative effects on satisfaction with working conditions, but it will arguably also reflect on personal life. For instance, having a temporary contract will in many countries make it harder to get a mortgage to buy a house (Waaijer et al. Citation2017); and/or it will make it more difficult to plan family and social life in a given location (given the high mobility that academic researchers are typically subject to). Based on these three arguments, we formulate the following hypothesis.

H1: Permanent contracts are positively related to academic job satisfaction.

2.2. Job satisfaction at different stages of the academic career

It is also important to investigate whether the relationship between job security and well-being at work varies along different stages of the academic career. The literature points out a relationship between career stage, working conditions and job satisfaction (e.g. Albert, Davia, and Legazpe Citation2018; Enders and Teichler Citation1997). Hence, it is interesting to examine whether permanent contract is an equally important factor of job satisfaction for young early stage researchers, more experienced middle-aged scientists, and older academics.

In general terms, the literature on life satisfaction has previously pointed out a remarkable regularity that holds in many countries worldwide, the so-called U-shape of life (Blanchflower and Oswald Citation2004, Citation2008). According to this, life satisfaction is typically high at young ages, it declines steadily until mid-life, and thereby increases again during older age. A similar pattern has also been found for job satisfaction. Clark, Oswald, and Warr (Citation1996), using data from the British Household Panel Study from 1991 (about 10,000 individuals), find a robust U-shaped relationship between age of workers and job satisfaction, after controlling for a large number of possible confounding factors. Clark, Oswald, and Warr (Citation1996) point out various possible explanations for this pattern, emphasizing one plausible argument that is particularly relevant for our study, namely changing expectations and aspirations over the career. At young ages, workers often experience high satisfaction due to the excitement of having a job, instead of being unemployed like other peers in the same age group. As the career proceeds, workers typically rise their aspirations and expectations about desired working conditions, which may lead to dissatisfaction when these aspirations turn out to be unmet. Finally, at older age, workers have increased experience and maturity, which lead them to form less ambitious aspirations and more realistic expectations, as well as to put less emphasis on comparisons with other peers and colleagues at work.

This U-shaped pattern has not been investigated yet for the case of academic researchers. However, some recent studies provide scattered evidence that is in line with this idea. For instance, Höhle and Teichler (Citation2013) find that job satisfaction in Germany is lower for middle-aged academics in their late 30s and early 40s. de Lourdes Machado-Taylor et al. (Citation2016) find a similar pattern for Portuguese academics, with highest satisfaction at early and later stages of the career, and lower levels in the middle. Bentley et al. (Citation2013) also report a positive relationship between age and job satisfaction at later stages of the career. Escardíbul and Afcha (Citation2017) include a quadratic term in their regression analysis of the determinants of job satisfaction among Spanish PhD holders, finding support for a non-linear relationship between age and workers’ well-being. Further, Fontinha, van Laar, and Easton (Citation2018) point out that having a temporary contract may have a stronger negative effect on job satisfaction when the researcher has had such temporary position for several years.

We contend that the theoretical argument explaining such U-shape of academic life is closely related to Clark, Oswald, and Warr (Citation1996)’s explanation for the working population as a whole. According to Hagedorn’s (Citation2000) framework, age is a ‘trigger’, as in different phases of life academics tend to change their expectations about desired work conditions and job satisfaction. Hence, differences in job satisfaction among researchers at different stages of the career may be explained by ‘differences of expectation, focus and aspiration and in levels of understanding of the demands of an academic career’ (Locke and Bennion Citation2013, 233).

In other words, it is reasonable to postulate that young early stage researchers will typically have high motivation and a focus on learning opportunities and intrinsic aspects of the scientific work (Albert, Davia, and Legazpe Citation2018).Footnote2 Middle-aged and more experienced academics will often have higher ambitions, stronger pressures to perform, and they will also be more subject to comparison effects. Finally, older and well-established researchers will have greater experience, which will arguably lead to form lower and more realistic ambitions, and to be less vulnerable to performance pressure and social comparison effects.

Based on this reasoning, we argue that job security is not an equally important factor at all stages of the academic career. Although having a permanent contract is admittedly important for all researchers, we postulate that it is relatively more important for middle-aged academics. The reason is twofold. On the one hand, academic tenure makes researchers less vulnerable to performance pressure and social comparison effects, which are crucial at intermediate stages of the career. On the other hand, having a permanent contract is important because it makes it easier to plan personal and family life, e.g. reducing mobility and the need to get a job in other cities or countries, which is a negative factor for satisfaction related to family life. This is a particularly important aspect for middle-aged individuals, which is typically the age group when important family-related decisions (e.g. having children; getting married; buying a house) are taken.

H2: Permanent contracts are relatively more important for the job satisfaction of researchers at an intermediate stage of the career.

2.3. Differences across countries in Europe

Although the two hypotheses that we have pointed out above formulate general relationships that we expect to hold, on average, for all researchers in European countries, it is also important to consider that there are huge differences in academic and labour market conditions across countries in Europe, which may affect the extent to which researchers get academic tenure, and the latter affects job satisfaction.

Regarding differences in terms of academic tenure systems, Enders and Teichler (Citation1997) emphasize country specificities for early stage researchers, and point out that «different systems offer tenured or unlimited contracts for middle-rank positions to younger staff members with a PhD to a different extent» (p. 350). For instance, Germany has worse employment security for younger staff compared to other European countries (Enders and Teichler Citation1997). Other studies emphasize the existence of more general differences in academic traditions and institutions across European countries, which determine different career paths in academia (Bennion and Locke Citation2010; Brechelmacher et al. Citation2015; Cavalli and Moscati Citation2010; Frølich et al. Citation2018). The online appendix A1 of this paper provides a brief discussion of different academic labour market models and permanent contract definitions in European countries.

However, cross-country differences may also be related to the more general issue of labour market institutions, and in particular employment protection legislation (EPL), which may of course also have implications for academic tenure and career structure in different countries (Waaijer et al. Citation2017). European countries have largely different relationships between employment protection legislation (e.g. legal protection against dismissal) and job security, on the one hand, and labour market flexibility, on the other (Muffels and Luijkx Citation2008). Böckerman (Citation2004) and Clark and Postel-Vinay (Citation2009) find a negative correlation between EPL and perceived job security. The reason for this is that stricter EPL makes it harder to dismiss workers. Strict EPL is thus good for ‘insiders’ (i.e. workers that are already permanently employed) but it makes it harder for ‘outsiders’ (unemployed, or part-time workers) to find a new job. Hence, EPL may also end up increasing job insecurity of temporary workers, which might anticipate the costs and insecurity of becoming unemployed in the future. Examples of countries with strict EPL in Europe are Southern EU economies, as well as Sweden, Norway and Germany (Esser and Olsen Citation2012, 446). Relatedly, it has also been noted that countries with stricter EPL typically make active use of temporary jobs (Clark and Postel-Vinay Citation2009). Recent labour market reforms towards deregulation in Europe have not changed substantially regulations to protect insiders, but rather affected hiring conditions for outsiders, hence in practice increasing the use of temporary forms of contract. This general trend is also reflected in the academic labour market, in which temporary contracts are now increasingly frequent, among other countries, in the Netherlands and Germany, as well as UK and the Nordic economies.

The variety of capitalism approach points out different groups of countries that are characterized, among other institutional features, by distinct labour market institutions (Amable Citation2003; Hall and Soskice Citation2001). In our empirical analysis, in line with this literature, we will distinguish five groups of countries (Continental, Nordic, Anglo-Saxon, Mediterranean, Eastern EU), in order to investigate whether our two theoretical hypotheses hold for all groups, or the extent to which they differ among European countries.

3. Data and methods

The database used for this study is the second edition of the Mobility Survey of the Higher Education Sector (MORE2), which was carried out in 2012. This is a large-scale representative survey of European researchers, their working conditions and their career paths. The objective of the MORE2 study was to ‘provide internationally comparable data, indicators and analysis in order to support further evidence-based policy development on the research profession at European and national level’ (IDEA Consult Citation2013). MORE2 provides information on about 10,000 researchers (from different scientific fields and at different stages of the career stages), working in HEIs in 34 European countries.

The dependent variable in our study is job satisfaction. The MORE2 survey includes various questions measuring different aspects of researchers’ reported well-being at work, such as satisfaction with salary, benefits, dynamism, intellectual challenge, level of responsibility, degree of independence, contribution to society, opportunities for advancement, mobility perspectives, social status, job location and reputation of employer. Our dependent variable job satisfaction is a composite indicator that sums together these variables. The reason for combining these variables together into a single composite indicator is that they are highly correlated to each other (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76), so that the composite job satisfaction indicator provides a good summary measure of different aspects of well-being at work.Footnote3 As reported in , the job satisfaction indicator ranges between 0 and 13, and it has a mean value around 10 in the whole sample. Across EU countries, the value is highest for Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland (close to 11), and lowest for Greece, Italy and Portugal (around 8,60).

Table 1. Indicators: definitions and descriptive statistics.

reports all indicators that we have included as explanatory variables in the empirical study, along with their definition and some descriptive statistics. The main explanatory variable is the contract duration variable, which is a dummy that takes value 1 for researchers that have a permanent contract, and 0 for those with a temporary contract. Among the control variables, we consider a set of personal characteristics of individual researchers (top part of the table), such as gender, age, nationality, family status and education level. Among the working characteristics and conditions (bottom part of ), we include the scientific field in which each researcher works, teaching load, reported career prospects and collaboration patterns (within academia and outside). Country dummies (not reported in ) control for differences in institutional conditions and cultures across countries.

The objective of the empirical study is to investigate whether researchers’ job satisfaction is affected by the type of contract they have (permanent vs. temporary). An important issue that has to be taken into account in this analysis is that the main explanatory variable of interest, permanent contract, is arguably not an exogenous and randomly assigned variable, but it is in turn dependent on a set of work-related and personal characteristics. For instance, the probability that a researcher has a permanent contract does arguably depend, among other things, on the worker’s age, education, experience level, and scientific field. This means that when we estimate the relationship between job satisfaction and academic tenure we have to take into account the possible endogeneity of the permanent contract variable.

To take this issue into account, we adopt a two-equation IV econometric approach. The first step is a probit equation that investigates the factors explaining why some researchers have a permanent contract and others have not, while the second equation studies the relationship between job satisfaction, academic tenure (endogenous variable) and control factors. The econometric model is the following:(1)

(1)

(2)

(2) where PC denotes permanent contract, JS job satisfaction, W is a set of control variables, Z is a peer effect included as instrumental variables (see below), and σ and ε are the error terms of the two equations. The subscripts i, c and j indicate the individual researcher, country and University (HEI) respectively. The subscript k indicates the kth variable in the vectors of control variables. To improve identification of the model, in addition to other explanatory variables, equation 1 also includes a vector of instrumental variables Z that are not included in equation 2 and that are supposedly uncorrelated with the error term of the second equation. Further information and discussion of the instrumental variables and identification strategy can be found in the appendix.

4. Results and discussion

presents the results of equation 2 (second-stage). Focusing on the first column of , the permanent contract variable reported on top of the table presents the results of tests of hypothesis 1. The results indicate that academic tenure positively and significantly affects job satisfaction. This provides support for hypothesis 1. After controlling for a number of possible confounding factors, and after taking into account the possible endogeneity of the tenure variable (see discussion in the appendix), we find that having a permanent contract is an important factor supporting well-being of academic researchers. As explained in section 2, our interpretation of this result is based on three related arguments. First, job security reduces uncertainty about the future, and it gives researchers the possibility to plan future career steps and working activities with a focus on more rewarding tasks, and hence be less dependent on ‘psychological contracts’ with their employers (Fontinha, van Laar, and Easton Citation2018; Waaijer et al. Citation2017). Second, tenured employees are in general less exposed and less vulnerable to social comparison effects, because their job security and future career prospects are not affected directly by their colleagues’ performance (Clark and Oswald Citation1996). Finally, having a permanent contract has also positive implications in terms of personal life, e.g. by making it easier to plan family and social life in a given location on a long-term basis, without the prospect to move to another city or migrate to another country (Waaijer et al. Citation2017).Footnote4

Table 2. Second-stage results (equation 2). Dependent variable: Job satisfaction. Linear regression with endogenous covariates.

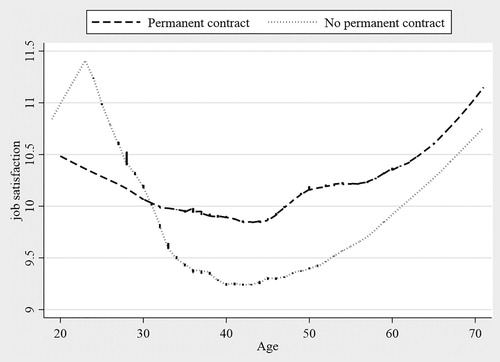

The second column of presents the results of tests of hypothesis 2. This hypothesis postulates that permanent contracts are relatively more important for the job satisfaction of researchers at an intermediate stage of the career. Before discussing these results, we note that finds a U-shaped relationship between age and job satisfaction, since the estimated coefficient for the age variable is negative, and the one for the age-squared variable is positive. This pattern, which is in line with extant research (notably Clark, Oswald, and Warr Citation1996) indicates that job satisfaction of academic researchers in our sample tends to decrease in the early phase of the career, it reaches the lowest point at middle-age (43-year old on average, according to our estimation results), and thereby increases steadily in the later part of the career.

Based on this pattern, hypothesis 2 tests whether the type of contract that researchers have (permanent vs. temporary) affects such U-shaped relationship between age and job satisfaction. To put it differently, we test whether age moderates the positive effect of academic tenure on researchers’ well-being. To test this second hypothesis, we introduce two interaction terms in the model specification of equation 2, which multiply academic tenure with age and age-squared, respectively. In this extended model specification, the coefficient that tests hypothesis 2 is the interaction effect of permanent contract and age-squared (Haans, Pieters, and He Citation2016).Footnote5

The results in the second column of show that this interaction variable is negative and significant. This means that the permanent contract variable affects the U-shaped relationship between age and job satisfaction by flattering it (i.e. decreasing its slope before the turning point). This econometric result is also evident in , which compares the U-shape of academic life for researchers with a permanent and those with a temporary contract. The figure shows that both tenured and non-tenured academics tend to experience a decrease in job satisfaction in the early phase of the career and up until middle age, but such decrease is much steeper for temporary workers, and substantially milder for permanent employees. The figure also shows that the relative effects of academic tenure are more visible up until middle age, whereas the increase in job satisfaction at later stage of the career is remarkably similar for tenured and non-tenured academics.

This econometric evidence lends support to our second hypothesis, i.e. that job security is a relatively more important factor of job satisfaction for middle-aged academics. As discussed in section 2, the interpretation of this result is based on two arguments. First, a permanent contract makes researchers less vulnerable to performance pressure and comparison effects with peers and colleagues, which are particularly important at intermediate stages of the career (and less so at later stages of working life; see Clark and Oswald Citation1996). Second, job security may also have some important positive implications for researchers’ personal and family life, for instance because it reduces uncertainty about the future, e.g. due to the need to get a job in other cities or countries (Waaijer et al. Citation2017). This aspect is particularly important for middle-aged individuals, since this is the age at which people typically take important family-related decisions.Footnote6

We have so far presented results for the whole sample of researchers that have responded to the MORE2 data survey, and which therefore provide a general test of our hypotheses when we consider academics from all European countries in this dataset. However, an important aspect that must be discussed refers to possible cross-country differences in these results. As noted in section 2, extant research points out that European countries differ substantially in terms of working conditions for researchers, and particularly so at early stages of the career. The academic tenure system does also vary among countries in the EU. These differences are broadly related to country-specific academic traditions and HEIs policies, as well as labour market institutions and policies (e.g. employment protection legislation; see Waaijer et al. Citation2017). It is therefore reasonable to expect that the role of permanent contracts for job satisfaction may not be the same across European economies, and arguably be more important for some and less relevant for other countries.

In order to discuss this aspect, we have repeated the tests of the two hypotheses for five distinct groups of countries: Continental, Nordic, Anglo-Saxon, Mediterranean, and Eastern EU. These country groups are in line with studies in the variety of capitalism approach, which points out different groups of countries that are characterized by distinct institutional features, and in particular different labour market institutions (Amable Citation2003; Hall and Soskice Citation2001).Footnote7

and report the results of estimations of equation 2 for each of these country groups separately. focuses on the test of hypothesis 1. While most of the control variables have similar results across country groups, an important difference is that the permanent contract variable is only significant for the sub-samples of Continental EU and Scandinavian countries, and not significant at conventional levels in the other three country groups. shifts the focus to the test of hypothesis 2. The interaction variable Permanent * Age-squared (which is the one that we use to test the hypothesis on the moderating effects of age on the job security-satisfaction relationship) is negative and significant for the groups of Continental EU and Scandinavian countries, and again not significant for the other three sub-samples. Taken together, the results in and indicate that we are able to confirm the important role of job security for researchers’ well-being only for Continental EU and the Nordic economies, whereas the evidence for other European countries is not statistically precise, and it does not enable to support our two hypotheses.

Table 3. Second-stage results for different country groups. Dependent variable: Job satisfaction. Linear regression with endogenous covariates. Baseline results, no interaction variables (test of hypothesis 1).

Table 4. Second-stage results for different country groups. Dependent variable: Job satisfaction. Linear regression with endogenous covariates. Models including interaction variables (test of hypothesis 2).

What can be the reasons of this? Continental and Scandinavian countries, according to MORE2 data, have on average a high level of academic job satisfaction (above the EU average), and at the same time a relatively low share of permanent contracts vis-à-vis other European countries. We posit that this peculiar combination of high job satisfaction and flexible labour markets for academic researchers may contribute to explain our econometric results.

These countries typically combine better working conditions for academics than other countries in Europe (e.g. in terms of wage, available resources and infrastructures, flexible time and work organization). Such good working conditions make the HEI sector highly attractive for many young workers, who may prefer to undertake an academic career and take a PhD instead of working in the private sector (Frølich et al. Citation2018). However, in recent years, there has been a growing mismatch in these countries between the number of young and middle-aged researchers aspiring to an academic career, on the one hand, and the number of available permanent positions, on the other (Bennion and Locke Citation2010; Brechelmacher et al. Citation2015; Cavalli and Moscati Citation2010). In the same period, HEIs in these countries have therefore increasingly made use of temporary forms of employment (which the trends towards deregulation and labour market reforms have facilitated). In short, it is this combination of high job satisfaction, good working conditions, but relatively low job security that may contribute to explain why researchers in Continental EU and Nordic economies point to temporary employment as an important factor hampering well-being at work.

Figure A1 in the online appendix provides additional evidence from the MORE2 survey dataset that corroborates this interpretation. The figure reports the share of permanent contracts for four different stages of the academic career (so-called R1, R2, R3 and R4) in the five different groups of European countries that we have considered in this study. The diagram clearly shows that, while for researchers at consolidated stages of the career (R3 and R4) the share of permanent contract does not vary substantially among European countries, this is not the case for middle-career researchers (R2), for which there are significant cross-country differences. For this group of academics, the percentage of permanent contracts is much lower in Scandinavian and Continental European countries compared to the other country groups, suggesting that getting a permanent contract at this stage of the career may in these countries be an important factor fostering academic job satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

The empirical results in this paper point out that academic tenure is an important antecedent of job satisfaction for researchers working in HEIs in Europe. We find that academics with a permanent contract are on average more satisfied with their job than their colleagues that are employed on a temporary basis. A few recent country-specific studies point out a similar finding for the case of Spain, Netherlands and the UK (Escardíbul and Afcha Citation2017; Fontinha, van Laar, and Easton Citation2018; van der Weijden et al. Citation2016). By considering a large cross-section of several thousand researchers in all European countries, the present study corroborates and extends recent research on this topic.

Our results also show that academic tenure is a relatively more important factor of job satisfaction for researchers at an early and intermediate stage of the career, and less so for older and well-established scientists. While other research in this field has previously suggested that job satisfaction of academics vary with age and career stages, the specific novelty of our result is that we estimate the hypothesis that age and career stages moderate the positive effect of contract duration on job satisfaction, showing in particular that the U-shaped relationship between age and job satisfaction is flatter for early-stage researchers that have a permanent contract compared to those who only have a temporary contract.

Finally, we also point out some important differences in the working of the model among European countries. Our two hypotheses receive empirical support for the groups of Continental EU and Nordic economies, whereas the tests are not statistically significant for other country groups (Anglo-Saxon, Southern EU, Eastern EU economies). This calls for future empirical research to investigate further the relationships between country-specific characteristics of the academic labour market and employment regulations on temporary work, on the one hand, and working conditions and job satisfaction in different countries in Europe, on the other.

On the whole, the paper contributes to this field of research by providing new empirical evidence on the important relationship between contract duration and job satisfaction, and of how this differs for academics of different age groups and European countries. Presenting new cross-country evidence on this topic based on a large representative sample of researchers is particularly important due to the paucity of cross-country comparative studies on academic job satisfaction. The empirical results in this paper are therefore meant to complement and extend previous research on job satisfaction in academia.

The paper has also some important managerial and policy implications. Job satisfaction of researchers is a key societal objective for two reasons. First, and more obviously, because public HEIs should to the extent possible provide their employees with good working conditions and career prospects, which are important preconditions to build up open and stable public spaces where creativity and new scientific ideas can flourish and be disseminated to the society. Second, job satisfaction is also important because it contributes to shape the attractiveness of a country’s R&D sector and public science system. Countries that provide good working conditions for public scientists will in general be able to attract a larger pool of talented researchers from the domestic private sector, and/or from other countries. And a larger and more competitive HEI sector will be important to foster scientific and technological innovations in the economic system as a whole.

Policy-makers and University leadership authorities should reflect upon this dilemma, and be aware that the recent trends towards labour market deregulation and the increasing use of temporary contracts in academia may end up worsening job satisfaction of non-tenured researchers, making the public science system less attractive for young talented individuals, and thereby less competitive in the future. On the other hand, however, increasing the number of permanent positions may also be a challenging task for University leaderships alone, given that the academic labour market is currently saturated in several countries. Public funding and other support mechanisms to sustain academic labour demand must go hand in hand with HEI’s recruitment and personnel policies on contract duration.

Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (34.3 KB)Acknowledgements

This paper is produced as part of the project ‘Investigating the Impacts of the Innovation Union (I3U)’. Financial support from the European Commission (Horizon 2020) is gratefully acknowledged. The paper was presented at the EU-SPRI Summer School on ‘The Science System in the 21st Century’ in Oslo, September 2018. We wish to thank two anonymous reviewers and the Editor of this journal for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 We think that the reason why such an important topic has not yet received systematic attention in the literature is twofold. First, temporary employment in academia has increased very rapidly in the last few years (Waaijer et al. Citation2017, 323). In particular, doctoral education has massively expanded in many countries.

In 2012, the number of students enrolled in PhD programs had increased by 40% in the 28 countries of the European Union […]. Since the number of potential applicants for each faculty position has increased at a higher pace than the number of jobs, it has provided hiring departments with a greater leeway to employ academics along more flexible terms. […] In many ways, these structural factors have created the conditions for the creation of a dual labor market, where a core of academics in secure employment coexists with an expanding periphery of workers with insecure job prospects. (Afonso Citation2016, 816)

2 As part of their focus on learning opportunities and capability building, young researchers are often inclined to see mobility, and international mobility in particular, as a necessary and useful step to build up and consolidate their early stage career. For instance, pre-doctoral mobility facilitates the entry to postgraduate doctoral studies, since it gives young researchers the opportunity to network and accumulate social capital as well as to increase independence and self-assertion. International mobility is thus often part of a personal strategy to advance an academic career in the home country (Brechelmacher et al. Citation2015; Fumasoli, Goastellec, and Kehm Citation2015).

3 In addition to summing up these variables together, we also used a second composite indicator that is the mean of these variables. However, the two composite indicators (sum and mean) are highly correlated to each other, and they provide very similar patterns and empirical results. Hence, we will only focus on one of them in the presentation of our results in the next section.

4 It is also relevant to ask whether the positive relationship between job security and satisfaction may partly be explained by the fact that equation 2 omits a wage variable among the control factors. Data on researchers’ salary level is not available in the MORE2 survey, and hence we are unable to include this as an additional control variable in the regressions. However, we have investigated this aspect and concluded that it is not an important issue for our estimation results. First, an important source of wage differences among researchers relates to country-specific institutional and labor market characteristics of European economies, which are implicitly controlled for in the regressions by means of country dummies. Second, the other important source of wage differentials in academia refers to the career stage at which each researcher is. In fact, within each country, the salary level typically increases with the career stage – i.e. the salary of a Professor is higher than that of an Associate Professor, postdoc, PhD student, and younger researcher. In some additional regressions not reported in this paper, we have included some additional categorical variables that note the stage of the career of each researcher in the sample (so-called R1 to R4 stages, according to the EU classification), and that implicitly control for salary differences among researchers at different stages of the career. These additional control variables do not affect the results of hypotheses tests that are pointed out in this section.

5 In these tests, the age variables have been standardized (mean-centred) in order to reduce multi-collinearity.

6 Note that the hypothesis formulated in section 2 discussed the role of career stage, in addition to age, as a moderating factor of the job security-satisfaction relationship. However, the econometric results that we present in this section focus more explicitly on the role of researchers’ age. The reason for this empirical choice is twofold. First, career stage and age are obviously closely and strongly correlated with each other, so that the latter represents a good proxy of the former. Second, the career stage variable available in the MORE2 dataset is categorical (four values: R1 to R4 stages), and it has much more limited variability than the age variable, which is a continuous indicator, and it is better suited to test the sort of non-linearities (U-shapes) that are discussed in the job satisfaction literature. Anyway, we also carried out some additional regressions in which we included the career stage categorical variables in addition to age among the regressors. These variables are mostly not significant, and their inclusion does not affect the main results presented in this section.

7 Continental: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands. Nordic: Denmark, Finland, Sweden. Anglo-Saxon: United Kingdom, Ireland. Mediterranean: Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Cyprus, Malta. Eastern EU: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia.

References

- Aarrevaara, T., and I. R. Dobson. 2013. “Finland: Satisfaction Guaranteed! A Tale of Two Systems.” In Job Satisfaction Around the Academic World, edited by P. J. Bentley, H. Coates, I. R. Dobson, L. Goedegebuure, and V. L. Meek, 103–123. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Afonso, A. 2016. “Varieties of Academic Labor Markets in Europe.” PS: Political Science & Politics 49 (4): 816–821.

- Albert, C., M. Davia, and N. Legazpe. 2018. “Job Satisfaction Amongst Academics: The Role of Research Productivity.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (8): 1362–1377. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1255937

- Amable, B. 2003. The Diversity of Modern Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bender, K. A., and J. S. Heywood. 2006. “Job Satisfaction of the Highly Educated: The Role of Gender, Academic Tenure, and Earnings.” Scottish Journal of Political Economy 53 (2): 253–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9485.2006.00379.x

- Bennion, A., and W. Locke. 2010. “The Early Career Paths and Employment Conditions of the Academic Profession in 17 Countries.” European Review 18 (S1): S7–S33. doi: 10.1017/S1062798709990299

- Bentley, P. J., H. Coates, I. R. Dobson, L. Goedegebuure, and V. L. Meek. 2013. “Academic Job Satisfaction From an International Comparative Perspective: Factors Associated with Satisfaction Across 12 Countries.” In Job Satisfaction Around the Academic World, edited by P. J. Bentley, H. Coates, I. R. Dobson, L. Goedegebuure, and V. L. Meek, 239–262. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Blanchflower, D. G., and A. J. Oswald. 2004. “Well-being Over Time in Britain and the USA.” Journal of Public Economics 88 (7): 1359–1386. 8. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00168-8

- Blanchflower, D. G., and A. J. Oswald. 2008. “Is Well-Being U-shaped Over the Life Cycle?” Social Science & Medicine 66 (8): 1733–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030

- Böckerman, P. 2004. “Perception of Job Instability in Europe.” Social Indicators Research 67 (3): 283–314. doi: 10.1023/B:SOCI.0000032340.74708.01

- Brechelmacher, A., E. Park, G. Ates, and D. F. J. Campbell. 2015. “The Rocky Road to Tenure – Career Paths in Academia.” In Academic Work and Careers in Europe: Trends, Challenges, Perspectives, edited by T. Fumasoli, G. Goastellec, and B. M. Kehm, 13–40. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Cavalli, A., and R. Moscati. 2010. “Academic Systems and Professional Conditions in Five European Countries.” European Review 18 (S1): S35–S53. doi: 10.1017/S1062798709990305

- Clark, A. E., and A. J. Oswald. 1996. “Satisfaction and Comparison Income.” Journal of Public Economics 61: 359–381. doi: 10.1016/0047-2727(95)01564-7

- Clark, A. E., A. J. Oswald, and P. Warr. 1996. “Is job Satisfaction U-shaped in Age?” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 69 (1): 57–81. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1996.tb00600.x

- Clark, A. E., and F. Postel-Vinay. 2009. “Job Security and Job Protection.” Oxford Economic Papers 61 (2): 207–239. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpn017

- de Lourdes Machado-Taylor, M., V. M. Soares, R. Brites, J. B. Ferreira, M. Farhangmehr, O. M. R. Gouveia, and M. Peterson. 2016. “Academic Job Satisfaction and Motivation: Findings From a Nationwide Study in Portuguese Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (3): 541–559. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2014.942265

- Enders, J., and U. Teichler. 1997. “A Victim of Their Own Success? Employment and Working Conditions of Academic Staff in Comparative Perspective.” Higher Education 34 (3): 347–372. doi: 10.1023/A:1003023923056

- Erdogan, B., T. N. Bauer, D. M. Truxillo, and L. R. Mansfield. 2012. “Whistle While You Work: A Review of the Life Satisfaction Literature.” Journal of Management 38 (4): 1038–1083. doi: 10.1177/0149206311429379

- Escardíbul, J.-O., and S. Afcha. 2017. “Determinants of the job Satisfaction of PhD Holders: An Analysis by Gender, Employment Sector, and Type of Satisfaction in Spain.” Higher Education 74 (5): 855–875. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0081-1

- Esser, I., and K. M. Olsen. 2012. “Perceived job Quality: Autonomy and Job Security Within a Multi-Level Framework.” European Sociological Review 28 (4): 443–454. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcr009

- Fontinha, R., D. van Laar, and S. Easton. 2018. “Quality of Working Life of Academics and Researchers in the UK: The Roles of Contract Type, Tenure and University Ranking.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (4): 786–806. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1203890

- Frølich, N., K. Wendt, I. Reymert, S. M. Tellmann, M. Elken, S. Kyvik, and E. H. Larsen. 2018. Academic Career Structures in Europe: Perspectives From Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands, Austria and the UK. Oslo: Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education NIFU.

- Fumasoli, T., G. Goastellec, and B. Kehm. 2015. “Academic Careers and Work in Europe: Trends, Challenges, Perspectives.” In Academic Work and Careers in Europe: Trends, Challenges, Perspectives, edited by T. Fumasoli, G. Goastellec, and B. Kehm, 201–214. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Haans, R. F. J., C. Pieters, and Z. He. 2016. “Thinking About U: Theorizing and Testing U-and Inverted U-Shaped Relationships in Strategy Research.” Strategic Management Journal 37 (7): 1177–1195. doi: 10.1002/smj.2399

- Hagedorn, L. S. 2000. “Conceptualizing Faculty Job Satisfaction: Components, Theories, and Outcomes.” New Directions for Institutional Research 2000 (105): 5–20. doi: 10.1002/ir.10501

- Hall, P. A., and D. Soskice. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism. The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Edited by P. A. Hall & D. Soskice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Höhle, E. A., and U. Teichler. 2013. “Determinants of Academic Job Satisfaction in Germany.” In Job Satisfaction Around the Academic World, edited by P. J. Bentley, H. Coates, I. R. Dobson, L. Goedegebuure, and V. L. Meek, 125–143. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- IDEA Consult. 2013. Final Report. MORE2 Support for Continued Data Collection and Analysis Concerning Mobility Patterns and Career Paths of Researchers. Brussels: European Commission.

- Lam, A., and A. de Campos. 2015. ““Content to be Sad” or “Runaway Apprentice”? The Psychological Contract and Career Agency of Young Scientists in the Entrepreneurial University.” Human Relations 68 (5): 811–841. doi: 10.1177/0018726714545483

- Locke, W., and A. Bennion. 2013. “Satisfaction in Stages: The Academic Profession in the United Kingdom and the British Commonwealth.” In Job Satisfaction Around the Academic World, edited by P. J. Bentley, H. Coates, I. R. Dobson, L. Goedegebuure, and V. L. Meek, 223–238. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Muffels, R., and R. Luijkx. 2008. “Labour Market Mobility and Employment Security of Male Employees in Europe: ‘Trade-Off’ or ‘Flexicurity’?” Work, Employment and Society 22 (2): 221–242. doi: 10.1177/0950017008089102

- Robinson, S. L., and D. M. Rousseau. 1994. “Violating the Psychological Contract: Not the Exception but the Norm.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 15 (3): 245–259. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150306

- Shin, J. C., and J. Jung. 2014. “Academics Job Satisfaction and Job Stress Across Countries in the Changing Academic Environments.” Higher Education 67 (5): 603–620. doi: 10.1007/s10734-013-9668-y

- van der Weijden, I., C. Teelken, M. de Boer, and M. Drost. 2016. “Career Satisfaction of Postdoctoral Researchers in Relation to Their Expectations for the Future.” Higher Education 72 (1): 25–40. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9936-0

- Waaijer, C. J. F., R. Belder, H. Sonneveld, C. A. van Bochove, and I. C. M. van der Weijden. 2017. “Temporary Contracts: Effect on Job Satisfaction and Personal Lives of Recent PhD Graduates.” Higher Education 74 (2): 321–339. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0050-8

- Wilkin, C. L. 2013. “I Can’t Get no Job Satisfaction: Meta-Analysis Comparing Permanent and Contingent Workers.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 34 (1): 47–64. doi: 10.1002/job.1790