ABSTRACT

This article addresses the governance relationship between the ministry responsible for higher education and the sector agencies against the backdrop of comprehensive sector reforms. The relationship is examined based on autonomy and capacity, which are argued to be decisive in negotiating areas of responsibility. The Austrian and Norwegian ministries responsible for higher education and their interplay with two subordinate agencies exemplify this negotiation process empirically. The findings, based on data derived from organizational figures, policy documents, law texts, and interviews with politicians, bureaucrats, and academics, show that the initial years of a changed modus operandi were characterized by uncertainty about the roles and expectations of the organizations involved. The more time passed the more consolidated and aligned the new governance practices became, although this consolidation and alignment depended on various autonomy and capacity determinants, which played out differently in both national contexts.

Introduction

Traditionally, ministries responsible for higher education have played a key role in determining the governance conditions for universities and colleges in continental Western Europe.Footnote1 Recently, these ministries have gradually moved away from micro-managing higher education institutions (HEIs) toward steering from a distance, in which the establishment of governmental agencies plays an increasing role (Capano Citation2011; Kickert Citation1995). Agencies now cover important aspects in the governance of higher education (HE) but there is still a limited understanding of how areas of agency responsibility are defined in interaction with the ministry (Capano Citation2011; Ferlie, Musselin, and Andresani Citation2008; Jungblut and Woelert Citation2018).

In line with developments in other public sectors (Pollitt et al. Citation2001; Verhoest Citation2012) a number of challenges emerge for ministries responsible for HE in establishing agencies. These challenges typically include questions of agency autonomy, political control, organizational performance, accountability, and policy coordination (Bach, Niklasson, and Painter Citation2012; Christensen and Lægreid Citation2007; Verhoest Citation2012), which are a consequence of the complexities of the underlying intention to make governance arrangements more effective (Lodge and Wegrich Citation2014; Rothstein Citation2011). The research questions addressed in this article are accordingly: How are ministry and agencies in the area of HE in Austria and Norway related to each other? In how far can a focus on the concepts of autonomy and capacity contribute to an explanation of their relationship?

The next section provides an overview of agencification trends in HE. This is followed by a discussion of the challenges ministries and agencies face in defining areas of responsibility in HE, showing how agencification initiatives can be interpreted as efforts to change the autonomy and capacity at both involved governance levels. The fourth section includes a description of the design of the underlying study and of the two cases (based in Austria and Norway), both of which have undergone structural governance changes through national university reforms in the early 2000s. Next, key findings are presented followed by a discussion of the implications of these findings and the main conclusions of the study.

Agencification in higher education

A number of studies (Huisman Citation2009; Paradeise et al. Citation2009) have addressed how the public authorities’ relation to universities and colleges has changed over the last decades through a governance mode characterized as ‘steering at a distance’ (Capano Citation2011; Huisman and Currie Citation2004; Kickert Citation1995; Van Vught Citation1989). This development is embedded within a general transformation of public administrations within the OECD countries. The structural devolution of public administration has been promoted as part of this transformation, most prominently in the form of agency creation (Pollitt et al. Citation2001; Verhoest Citation2012).

Agencies are commonly understood to be organizations that (a) are subordinate to a ministry yet formally separated from it, (b) adhere to public law and are responsible for specific tasks at the national level assigned by the ministry, and (c) are mainly state funded and staffed by public servants (Bach, Niklasson, and Painter Citation2012; Christensen and Lægreid Citation2007). Agency creation has become a favorite template for restructuring public administration that has spread across countries and public sectors (Pollitt et al. Citation2001).

The HE sector has also been affected by this development (Beerkens Citation2015; Capano and Turri Citation2017; Jungblut and Woelert Citation2018), especially in the area of quality assurance (QA). QA agencies and their consequences for the sector received some scholarly attention (Westerheijden, Stensaker, and Rosa Citation2007), while agencies established in other subdomains, such as internationalization and student support, have been studied to a lesser extent. In addition, only a few studies have addressed the governance role of agencies and their interactions with ministries responsible for HE.

Beerkens (Citation2015) discusses agencification processes in QA and highlights the challenges of autonomy, political control, and accountability in the Netherlands, Great Britain, Norway, and Denmark. The author concludes that QA agencies have become a dominant regulatory actor in the space between the ministry and universities, with their own identities and strategies. Jungblut and Woelert (Citation2018) focus on the agencies’ role in the wider institutional matrix of HE in Australia and Norway. They apply a more holistic view to governance arrangements and the role of agencies by combining agencification trends with coordination aspects in HE policy processes. Capano and Turri (Citation2017) address one of the central dilemmas in creating agencies in HE, which is the question of agency autonomy and governmental control. The authors designed a framework in which an agency's policy autonomy can be assessed and categorized depending on the level of legal power it holds (high or low) in relation to the government's steering capacity (also high or low). This framework results in four ideal-type agencies (dominant, additional, administrative, and instrumental) that differ in their function.

This typology represents an important contribution for classifying and conceptualizing different types and roles of agencies in HE. However, the typology remains static and does not capture the dynamic interplay underlying the relationship between agency and ministry. Further, the typology is based on a fairly implicit understanding of capacity matters and suggests that the effectiveness of an agency primarily depends on its ‘policy autonomy.’ As will be argued below, autonomy is a necessary but insufficient dimension for assessing a given agency's effectiveness and position of power in relation to the ministry.

Drawing on conceptualizations of governance quality (Fukuyama Citation2013; Rothstein Citation2011), this article presents an analytical framework in which autonomy will include both formal and informal dimensions. In some autonomy instances, a conceptual distinction between ‘ministerial authority’ and ‘agency autonomy’ will be made because of the hierarchical imbalance between the two organizations. Capacity will be added as a secondary analytical parameter, which will allow for capturing the changes and dilemmas that are of relevance for understanding the dynamic governance relationship between ministries and their subordinate agencies in HE.

Studying autonomy-capacity dilemmas

In essence, an agency's formal autonomy relates to all that has been codified in law: that is, the regulations defining the mandate of the agency and its legal scope of action (Yesilkagit and van Thiel Citation2008). However, these boundaries are often far from clear (Bach, Niklasson, and Painter Citation2012), among other things because ‘it is impossible to write laws that specify down to the last detail what is allowed and what is forbidden’ (Christensen and Yesilkagit Citation2006, 203).

Consequently, an informal dimension or de facto situation (Bach, Niklasson, and Painter Citation2012; Maggetti Citation2007) depicts how ministries and agencies interact within legal boundaries. If we consider autonomy as a trade-off between ministry and agency, then a simple approach is to trace if jurisdiction for organization A has been transferred to organization B or vice versa, or if the jurisdiction has not changed at all. While this is relatively easy to examine formally, for example through comparing legal frameworks in pre- and post-reform periods, tracing de facto changes and power constellations is more difficult to grasp. Key indicators for actual agency autonomy in this study have been defined as (a) the perception of ministerial staff about the agencies’ role, and (b) the perception of agency staff about the degree to which they can influence policy development within the formal boundaries. These indicators are naturally interrelated yet emphasize different aspects. In the first case, observations of situational events are of importance, such as how a ministry behaves if a QA agency develops a strategy that is not in line with ministerial interests. The second indicator contrasts the ministry's view with how the agency interprets its mandate and makes use of its room to maneuver within given boundaries.

Another facet for studying the dynamics between ministry and agencies includes capacity developments, as any discussion of autonomy will become irrelevant if these organizations lack the resources to experience their autonomy (Fukuyama Citation2013). From the perspective of public administration, Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (Citation2015, 166) define capacity ‘as the set of skills and resources […] necessary to perform policy functions.’ For measurements of capacity in organizational terms, important indicators are (a) the organization's operational budget (b) the number of personnel working in the organization with responsibility for a specific policy area, and (c) the professional expertise of that personnel (Fukuyama Citation2013). The operational budget essentially covers the costs for material, personnel, rents, and the like and not, for example, funds distributed and channeled to HEIs or study programs. The number of staff defines how effectively the organizational mandate is implemented (Egeberg Citation1999; Fukuyama Citation2013). The operational budget and staff numbers are positively correlated, since personnel costs overall consume most of the budget. The expertise of the personnel is a qualitative dimension that depends on training and education. Indicators include formal level of education such as staff who hold PhDs (Fukuyama Citation2013). Analytically, it is important to distinguish between the capacity of the ministry and the capacity of the agency in order to get a thorough and valid understanding of their governance relationship.

The idea of contrasting autonomy with capacity in the analytical framework derived from debates about what constitutes effective governance arrangements (Fukuyama Citation2013; Rothstein Citation2011). Fukuyama (Citation2013), for example, assumes an ideal constellation between the appropriate degree of autonomy and the right amount of capacity concerning the proper functioning of public administration. For instance, an agency that consists of incapable staff yet is equipped with a powerful mandate runs the risk of carrying out a misguided agenda. In such a case, public authorities should restrict the agency's autonomy in order to prevent any negative consequences for the sector. In the opposite case, it might be wise to encourage discretion, because the agency consists of capable staff with a high level of expertise, and thus can be expected to perform well, with favorable outcomes.

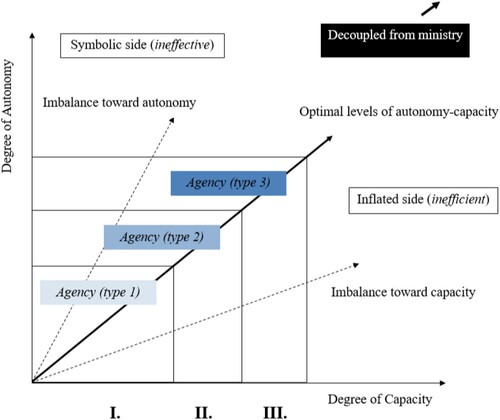

Fukuyama's approach has primarily been developed for analyzing the quality of national bureaucracies in the proliferation of public services. Here, it is argued that this approach is also appropriate to examine the relationship between ministry and agencies in HE, and for formulating various expectations related to potential autonomy-capacity constellations. Taking as a starting point that a ministry allows its agencies differing degrees of autonomy through determining an agency's formal mandate, and granting them various levels of capacity in the sense of the resources necessary to implement the mandate, the various constellations shown in are possible.

The linear function in the center of the figure describes the optimal levels of autonomy and capacity for the agency. The closer the position of an agency to the linear function the more balanced are its levels of autonomy and capacity. The zero point implies that an agency is in essence a unit within the formal organizational boundaries of the ministry. The farther an agency is positioned away from the zero point, the looser coupled it is from the ministry. Structurally, ministry and agency cannot become completely detached from each other, given the legal implications and formal responsibility of the ministry for the agency. However, it can be argued that agencies beyond the third quadrant have gone beyond the factual control of the ministry.

An agency positioned within quadrant type 1 has low degrees of autonomy and capacity, meaning that it is assumed to play a marginal role in the governance matrix, even if it enjoys an optimal autonomy-capacity balance. An agency positioned in quadrant type 2 is assumed to play a more active role in its assigned policy field, having a close-to-optimal relationship to the ministry. The type 3 position demarcates agencies that enjoy high amounts of autonomy and capacity; an agency positioned in this category can be problematic to the ministry because it has reached a potentially excessive level of autonomy and capacity that would allow it to implement its mandate beyond the control of the ministry.

Positions off the linear function present deviations from an optimal balance between autonomy and capacity levels but with different implications. The area above the linear function indicates a high level of autonomy and a relatively low level of capacity. An agency positioned in that area (the symbolic side) thus fulfills its mandate sub-optimally. The agency's mission is symbolic because it lacks the resources to function effectively, even though in theory it would have the appropriate mandate to do so. In contrast, a flatter linear function indicates high levels of capacity with relatively low levels of autonomy. An agency in this spectrum (the inflated side) fulfills its mandate in an inefficient way; simply put, it has too many resources that cannot be used appropriately, because the agency lacks autonomy. This framework allows for analyzing both varying amounts of autonomy and capacity for the agency as well as an agency's status in relation to its ministry.

Methodology

Empirical context and case selection

Developing a better understanding of the governance relationships between ministry and agencies in light of transforming HE sectors still calls for more conceptual work. A qualitative research design allows for an in-depth understanding of underexplored phenomena and for analytic generalizations at the conceptual level (Eisenhardt Citation1989). For these reasons a comparative and multiple case study design was depicted (Yin Citation2014), also in order to identify common traits and differences of changes in the central public governance matrix. The selection rationale of suitable cases was purposeful (Maxwell Citation2013) and based on an interest in cases that are (a) experiencing the establishment of governmental agencies as part of changes in public administration and national ministries, (b) as a consequence, changing their areas of responsibility in key policy areas within HE, (c) embedded in complex and mature HE sectors. Based on these rationales, the Austrian and Norwegian public administration responsible for HE were selected as relevant cases.

Given the interest in long-term developments and structural changes, the article's focus is rather on changes at the organizational level, than how these relations are influenced by single individuals.

Case 1 is an examination of the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research (KD) and its governance relationship to the Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (SIU) and the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (NOKUT). Case 2 consists of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research (BMBWF) and its relationship to the Austrian Agency for International Cooperation in Education and Research (OeAD) and the Agency for Quality Assurance and Accreditation Austria (AQ Austria).Footnote2

An advantage of comparing these two cases is their shared timeline in the reform processes. Starting point is the implementation of the Quality Reform in 2003 in Norway and the introduction of the University Act 2002 in Austria (Bleiklie Citation2009; Winckler Citation2012). In both cases, the implementation of these reforms was the result of numerous discussions, hearings, lobbying, and negotiations. For capturing the dynamics that led to these reforms, legal developments around the turn of the century and relevant national characteristics are of relevance. From an organizational perspective, ending the study in 2018 is logical. At that time, the Norwegian ministry underwent the most comprehensive internal change since its establishment as the Ministry of Education and Research in 2006, which included major restructurings of the SIU (since 2018 known as Diku due to a merger with two other agencies) and NOKUT (due to mandate changes). As for the Austrian case, the ministerial section responsible for HE became part of the newly established Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research in 2018. In both countries, the appointment of new ministers for HE accompanied these changes.

Data collection

In order to examine how ministerial authority / agency autonomy and capacity are balanced, and in order to grasp the interactional dynamics between ministry and agencies in defining areas of responsibility, the study applied multiple methods in a triangulated fashion (numerical data, documents, and interviews). In total, 26 semi-structured interviews with 28 participants were conducted. The interviews came in different formats: 23 face-to-face interviews with individual participants, two face-to-face interviews with two participants jointly, two telephone interviews, and one Skype interview. Participants were considered suitable if they:

had long working experience in the organization of interest, preferably starting before the new laws were introduced (and thus having been able to witness the transformation process over the years);

held crucial positions in the organization, such as management/leadership;

played a key role in advocating, pushing forward, and implementing the reform process.

Corroborating data (documents / numbers) from the years 2000 to 2017 (including annual reports of the agencies, allocation letters by the Norwegian ministry, documents on task divisions in the Austrian ministry, and national HE laws) revealed staff-number developments and formal organizational changes during the past two decades. Further pieces of complementary data, such as operational budgets, were received upon request directly from the organizations or were found in national databases, such as the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. In some cases, interview participants provided assistance in acquiring relevant data material or complementing existing material ().

Table 1. Overview of organizations and interview participants.

Data analysis

Interviews were conducted in English and German and were coded manually following transcription. The coding/analytic process went through several rounds. In the content analysis step, initial ad hoc coding was done by writing interview reflections and summaries right after an interview session had taken place. In the second step, particular segments were coded descriptively, with the intention of obtaining an overview of the issues that were discussed, accompanied by preliminary jottings. The third round was a deductive analysis that was done to examine ‘the data for illumination of predetermined sensitizing concepts or theoretical relationships’ (Patton Citation2014, 551), which in this case included ‘ministerial authority / agency autonomy’ and ‘capacity’ as well as their relationship to each other. After completion of these initial analytical rounds, some participants were contacted for clarification and / or commenting on specific issues, as this step provided extra reliability (Yin Citation2014). Triangulating the interviews with statistical data and documents was motivated by strengthening the overall validity of the findings, thereby reducing potential biases and idiosyncrasies of the cases.

Results

Reform rationales in Austrian and Norwegian higher education

The empirical analysis shows how ministries and agencies in both national contexts relate to each other. Recent changes to system-level governance and the implications for ministries and agencies must be seen in light of the universities’ situation in the 1990s, when massification and a growing Europeanization process put the Austrian and Norwegian HE sectors under pressure (Bleiklie Citation2009; Winckler Citation2003). Central actors realized that the then governance modes were no longer appropriate and effective. Task forces in both countries were formed that looked into the possibilities of different governance arrangement and how to address current trends and challenges. In Austria, an expert group emerged in a more ad hoc way with central actors and stakeholders in Austrian HE that proposed and lobbied for systemic changes at the ministry. In Norway, the ministry set up a national expert committee, the Mjøs committee (consisting of experts from academia and the broader sector), with the mandate to recommend system-level changes.

A central element in both countries’ policy debates was how to design and define the governance relationship between universities and the state. This re-definition process was subsumed under the concept of ‘university autonomy.’ While this was not a new concept in itself, the interpretations at that time leaned toward less direct state interference and strengthened institutional room to maneuver. Perceived ineffective governance mechanisms correlated with an enormous ‘level of suffering’ (A_3, translated by the author), which emerged within both the ministry and the institutions, and concerned strenuous administrative command chains, which contained little room for policy formulation. In other words, dissatisfaction about micro-steering processes was prevalent in both Austrian and Norwegian HE at that time:

The institutions had very, very little autonomy, and they had to bring up … every kind of question to the ministry. When it was raining [and the rain gutter was broken], you had to go to the ministry to [ask for] money, and the ministry had to [approve] every kind of change, even at the University of Oslo, when it came to administration. (D_3)

If you … needed a printer for your computer, then you had to write applications and have cumbersome phone calls with Vienna. And then some undersecretary in the ministry … decided if it was okay if a printer could be installed somewhere. (A_2, translated by the author)

Issues of authority in administering higher education

In both Austria and Norway, the ministry was supposed to keep the role of the political guardian and maintain sectoral interests. The question, however, was how to preserve and further develop the ministry's mandate. Two central governance tools were devised and modified in the past two decades: strategic steering of the universities and colleges through performance agreements, and the empowerment of agencies. The latter acquired substantial authority over key policy areas in HE (such as internationalization and QA) and operated at arm's length of the ministry. The crucial question, though, was how this ‘arm's length’ was to be interpreted.

To begin with, all four agencies examined in this study are by the end of this study under the direct responsibility of the ministry (i.e. governmental agencies). The internationalization and exchange agencies SIU and OeAD started originally as program associationsFootnote3, orchestrated by the universities, until new laws were introduced in the 2000s. In the course of increasing Europeanization trends and in the aftermath of revised HE laws, the two associations became formal governmental agencies, although the timeline for the countries differed. While the SIU in Norway became an agency with the new university law from 2005, it was not before 2009 that the OeAD in Austria was established as a governmental agency with the status of a GmbH (which is similar to a limited liability company) but still with 100% ownership by the Austrian ministry. The mandate for both the SIU and the OeAD expanded substantially in the past 10–15 years and incorporated in addition to HE also other educational levels. These agencies therefore did not gain responsibility at the cost of the ministry but because of an expanding mandate. In addition, being at the intersection of policy areas under the responsibility of other ministries (such as the foreign-affairs ministry), their autonomy was constantly subject to inter-ministerial interactions. Therefore, ministerial authority was often related to safeguarding the interests of the ministry's internationalization agencies rather than interfering in their operations.

In terms of QA, the establishment of NOKUT in Norway was a direct consequence of the 2003 Quality Reform. NOKUT's main tasks when it started to operate in 2005 were the accreditation of Norwegian HEIs and study programs, and the approval of foreign qualifications. Over the years, NOKUT has become an important actor on all issues related to QA in Norwegian HE. In general, NOKUT functions as a supervisory body, information provider, and stimulator of quality debates in Norwegian HE. These functions include responsibility for the Centers for Excellence in Education program, which was established in 2010. NOKUT's mandate expansion has in essence led to a relatively powerful position in the Norwegian HE landscape.

In Austria, in contrast, QA of the tertiary sector remained fragmented until 2012. Until the new QA law (Hochschul-Qualitätssicherungsgesetz) was implemented in 2011, the Austrian system continued to have particular QA agencies such as the FHR (Fachhochschulrat) for the Universities of Applied Sciences, the ÖAR (Österreichischer Akkreditierungsrat) for private universities, and the AQA (Austrian Agency for Quality Assurance) from 2003 on for public universities. However, the AQA was mainly a consultative association with no accreditation mandate. Austrian universities were opposed to institutional accreditation because they saw such accreditation as conflicting with institutional autonomy (Fiorioli Citation2014). This outlook changed when AQ Austria was established in 2012 (a merger of the FHR, ÖAR, and AQA), though with some important limitations: even though public universities now had to be audited, there were no regulated consequences if the first audit did not lead to certification, other than needing a re-audit. Second, unlike the situation in Norway, Austrian institutions could choose foreign QA agencies that were registered in the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education (EQAR).Footnote4

In general, the perception of the Austrian agencies and their role in the public governance structure is more instrumental, as one of many similar statements shows:

[Agencies are the] extended work bench. … The ministry develops the overall agenda, and the agencies are supposed to execute [the agenda] operatively. (A_4, translated by the author)

We [the ministry] will never interfere in their decisions. I mean, that is, in the Norwegian context, it is just unthinkable. … We can give [the agencies] instructions and ask them to do specific things for us, but we will never interfere in [what they have decided upon]. (D_2)

Capacity developments within public administration

Another difference between Austria and Norway relates to staff-number developments in the ministries and agencies (see ). In Norway, the staff numbers of the ministerial section responsible for HE have remained stable, but the SIU and NOKUT experienced substantial growth of about five times more employees between the early 2000s and 2017. In Austria, the situation was considerably different. Staff numbers at the ministry, and especially in the HE section, were reduced dramatically once it became clear that the 2002 law would be implemented (in 2017, the ministry had around half of the staff numbers compared to 2000). This reduction continued until 2009/2010 with staff numbers remaining relatively stable from then on. The OeAD experienced a similar development as the SIU in Norway: it grew substantially and steadily in terms of staff numbers between 2006 until 2017.

Table 2. Development of staff numbers (full-time equivalents, rounded).

The development of operational budgets also shows some differences. Due to staff-number reductions, the expenditures in the Austrian ministry decreased in the early 2000s. In contrast, the operational budget of the Norwegian ministry increased steadily at that time. SIU's and NOKUT's operational budgets grew six times larger in the study period, while OeAD's budget tripled. The budget of AQ Austria has remained stable since 2012, when the agency was established.

Three interrelated professionalization issues are important to mention here. First, the development toward more strategic behavior and indicator steering made a more complex and sophisticated database structure necessary. Information and data became an even more important currency in a governance mode that now relied increasingly on evidence-based policy-making, performance agreements, and output control. Consequently, one crucial organizational development within the Norwegian agencies from 2009 on has been the establishment analytical departments:

So it wasn't until we made a new strategy in 2008 … where we were quite clear … that we actually need[ed] to do more analysis to be an agency, to be a competent body in our field. We managed to set up a special department for analysis and development. (B_1)

The third issue is that of the staff's educational background. In general, one can observe a development toward staff with higher degrees (master and PhD) at both the agencies and the ministry. Further, staff became increasingly diverse in the past two decades in terms of their educational backgrounds, with fields such as sociology, political science, economics, and IT becoming more prominent. As pointed out in the interviews, all organizations tried to recruit more people with IT-related knowledge (due to digitalization processes, big data analyses, etc.) or a background in natural sciences. However, these areas of academic specialization remained underrepresented in the ministerial and agencies’ staff profile compared to the social sciences.

Discussion and conclusion

Negotiating areas of responsibility

One important finding of this study is that dividing areas of responsibilities between ministries and agencies is not always a zero-sum constellation (Friedrich Citation2019). For example, the ministry does not necessarily lose formal authority over a policy area in which an agency has gained substantial autonomy. Agencies continue to be state owned and subordinated to their ministry. Second, being governmental organizations implies that their operational budgets are funded publicly. In formal terms, the ministry thus is the highest authority through ownership, but agency expertise due to new policy areas can undermine ministerial authority.

One possible explanation for this undermining is rooted in the information advantage that a powerful agency holds (Verhoest Citation2012), especially if the ministry lacks the capacity to control the agency. Moreover, the nature of the mandates which internationalization and QA agencies have, has different implications for ministerial authority. In other words, agencies can undermine ministerial authority in different ways.

Internationalization agencies appear to have a more autonomous role than QA agencies, which might have several explanations. Both the OeAD and SIU have longer institutional histories in their HE sectors, where international academic cooperation has played an important role. Further, the internationalization agencies acquired additional policy areas (new country collaborations, additional funding systems, and the like) through an intensified Europeanization/globalization process. However, internationalization agencies have no formal power, meaning that if a HEI does not want to internationalize through student exchange programs, the agencies have no means to force the HEI. In this respect, their operations do not interfere directly with ministerial ambitions in potentially controversial matters, which can be interpreted as a more autonomous role.

QA on the other hand presents a policy area that can be considered a control instrument for the ministry toward HEIs, with a control function in the area of accreditation and quality assessment. If a university does not reach the minimum quality levels, it can be punished (e.g. by losing its university status). The same goes for study programs that can lose public funding if they do not have adequate quality. However, suggesting to deprive HEIs of their university status can under certain circumstances also lead to conflicts with the ministry, which might have political interests to preserve university status. Such issues can be considered more controversial than for matters concerning internationalization agencies, thus undermining each other's area of responsibility more directly.

Power through expertise and analytic capacity

One dilemma from the perspective of the Austrian ministry was the assumption that more institutional autonomy for universities might mean less work for the ministry. The universities – more precisely, the institutional level/leadership – would take over certain tasks from the ministry, such as personnel policies, thus making analog capacity in the ministry obsolete. However, in hindsight, in terms of control options and the safeguarding of systemic interests / variety, this seemed to be a misguided conclusion. The constellation of anticipated task developments (i.e. a transfer from the ministry to universities), the existence of strong administrative leaders at both the ministerial and university levels that supported the reform agenda, and a favorable political leadership made it possible that ministerial capacity decreased substantially. At the same time, there were no immediate aspirations to further develop the agency structure, at least related to internationalization and QA. This only happened gradually, once it became clear that ministerial interests related to systemic developments could only be pursued effectively with more capacity.

In Norway, the ministry expected that changed governance modes would not mean less but different work. This expectation implied that ministerial capacity had to remain stable. Additionally, due to the ministerial agenda of strengthening the agency-level, agencies developed into organizations with substantial policy input and high levels of policy autonomy. However, enhanced analytic capacity at the agency level has brought a different challenge in the Norwegian HE sector. Developing the SIU and especially NOKUT has been a two-edged affair for the ministry. In essence, the ministry seems to perceive the development of the agencies positively, but concerns have also been raised that NOKUT has become too independent over the years.

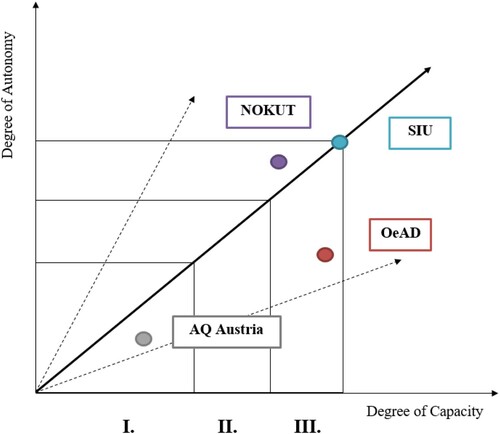

depicts the autonomy-capacity levels of the agencies, and shows how autonomous they have become in relation to the ministry by the end of the study period (2018). The position of the agencies aggregate formal and actual autonomy indicators as well as capacity features. The Norwegian agencies NOKUT and the SIU have a solid standing and are moving further toward more decoupling, especially the SIU. Their position in the third quadrant is due to continuous autonomy expansions and capacity increases, as well as their high-perceived factual autonomy. NOKUT's deviation is due to its more controversial role, and the claims that it has become too powerful. For the Austrian agencies, the data indicate that the OeAD has become quite powerful in capacity terms but less so in terms of autonomy. AQ Austria has a relatively limited mandate and is assigned a less important governance role than e.g. compared to NOKUT (hence its placement in the first quadrant and the minor deviation from the linear function). However, overall it seems that AQ Austria has rather appropriate capacity levels for that mandate.

Conclusion

Balancing autonomy and capacity presents an important facet in the governance of HE. The reason for discussing the dimensions in relation to each other was to reflect about potential combinations that could appear as effective governance arrangements. As the findings show, varying degrees within these two dimensions had different implications for effective governance arrangements in Austria and Norway.

A high degree of agency autonomy, as in Norway, is beneficial to effective system steering but also makes it difficult for the Norwegian ministry to assert its authority toward the agencies. The ultimate effectiveness of the agencies, however, depends on capacity determinants, which developed more dynamically in the Norwegian case. Since ministerial capacity remained stable at the same time, assumptions can be made to which extent this governance mode entails redundancies. While the argument holds that different tasks do not necessarily mean less work, this situation does raise the question of how much capacity in the ministry will be necessary if agencies are expanded substantially. The Norwegian case (stable capacity in the ministry and increasing capacity in the agencies) can also be seen as a structural-change problem since new working modes take time to become completely detached from former modes (Brunsson and Olsen Citation2018).

In the Austrian case, the ministry reduced its own capacity and strengthened the agencies with some delay compared to Norway. Further, there is a difference in how the agency-level has been strengthened regarding QA (AQ Austria) and internationalization (OeAD). The latter extended its mandate and experienced a substantial capacity increase (among other things because it is now also responsible for secondary levels in education). As a result, Austrian HE may have experienced a system-level policy vacuum in the time after the reforms were introduced, as several indications show. First, the ministry faced capacity reductions in different forms, including fewer staff and less professional expertise in new governance modes. Second, a fragmented QA agency structure had practically no accreditation power for the public universities, implying that the ministry had no control mechanism via agency. Third, HEIs explored their new autonomy and therefore had little interest in systemic development.

These findings present important aspects of change processes at the state level in HE governance and are especially relevant for mature public HE sectors undergoing reforms. The theoretical contribution of the present study is the design of a framework that allows for capturing both the dynamics between the ministry and agencies as well as for considering effective governance arrangements. This contribution was substantiated with empirical findings from two cases that have faced comprehensive HE reforms and an intensifying agencification process.

However, this study does have several limitations. One challenge with case study designs in general is how idiosyncratic their theoretical contributions are and to what extent the theoretical generalizability may be increased (Eisenhardt Citation1989). Based on these limitations, future research avenues should include other types of public administrations / policy regimes in order to complement our understanding about the governance relationship between ministries and agencies in HE. Researchers could also include different types of agencies (such as research councils) and the institutional level. Another aspect would be to include the individual level to a greater extent (e.g. the role of senior leadership in change processes), thus providing a more complete picture of governance shifts.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the HEDWORK research group for helpful comments on earlier drafts. Special thanks to Peter Maassen and Jens Jungblut for their continuous support, patience, and for sharing their thoughtful insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In this article, the terms ‘universities’ and ‘higher education institutions’ will be used synonymously, unless stated differently.

2 The abbreviations refer to the Norwegian and the German titles respectively: KD = Kunnskapsdepartementet, SIU = Senter for internasjonalisering av utdanning, NOKUT = Nasjonalt organ for kvalitet i utdanningen, BMBWF = Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung, OeAD = Österreichischer Austauschdienst, AQ Austria = Agentur für Qualitätssicherung und Akkreditierung Austria.

3 SIU was founded in 1993, the OeAD in 1961.

4 The European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education (EQAR) lists all QA agencies that substantially comply with the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the EHEA (ESG). (https://www.eqar.eu/, 14.10.2019)

References

- Bach, Tobias, Birgitta Niklasson, and Martin Painter. 2012. “The Role of Agencies in Policy-Making.” Policy and Society 31 (3): 183–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2012.07.001

- Beerkens, Maarja. 2015. “Agencification Challenges in Higher Education Quality Assurance.” In The Transformation of University Institutional and Organizational Boundaries, edited by Emanuela Reale, and Emilia Primeri, 43–61. Rotterdam: SensePublishers.

- Bleiklie, Ivar. 2009. “Norway: From Tortoise to Eager Beaver?” In University Governance: Western European Comparative Perspectives, edited by Catherine Paradeise, Emanueal Reale, Ivar Bleiklie, and Ewan Ferlie, 127–52. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Brunsson, Nils, and Johan P. Olsen. 2018. The Reforming Organization: Making Sense of Administrative Change. Milton: Routledge.

- Capano, Giliberto. 2011. “Government Continues to Do Its Job. A Comparative Study of Governance Shifts in the Higher Education Sector.” Public Administration 89 (4): 1622–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01936.x

- Capano, Giliberto, and Matteo Turri. 2017. “Same Governance Template but Different Agencies.” Higher Education Policy 30 (2): 225–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-016-0018-4

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. 2007. “Regulatory Agencies? The Challenges of Balancing Agency Autonomy and Political Control.” Governance 20 (3): 499–520. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00368.x

- Christensen, Jørgen G., and Kutsal Yesilkagit. 2006. “Delegation and Specialization in Regulatory Administration: A Comparative Analysis of Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands.” In Comparative Studies of Organizations in the Public Sector. Autonomy and Regulation: Coping with Agencies in the Modern State, edited by Tom Christensen, and Per Lægreid, 203–234. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Egeberg, Morten. 1999. “The Impact of Bureaucratic Structure on Policy Making.” Public Administration 77 (1): 155–170. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00148

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

- Ferlie, Ewan, Christine Musselin, and Gianluca Andresani. 2008. “The Steering of Higher Education Systems: A Public Management Perspective.” Higher Education 56 (3): 325–48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9125-5

- Fiorioli, Elisabeth. 2014. “Entwicklungslinien und Strukturentscheidungen der Qualitätssicherung in Österreich.” In Handbuch Qualität in Studium und Lehre, edited by Michaela Fuhrmann, Jürgen Güdler, Jürgen Kohler, Philipp Pohlenz, and Uwe Schmidt, 103–120. Berlin: DUZ Verlags- und Medienhaus GmbH.

- Friedrich, Philipp E. 2019. “Organizational Change in Higher Education Ministries in Light of Agencification: Comparing Austria and Norway.” Higher Education Policy, 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-019-00157-x.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2013. “What Is Governance?” Governance 26 (3): 347–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12035

- Huisman, Jeroen. 2009. International Perspectives on the Governance of Higher Education: Alternative Frameworks for Coordination. New York: Routledge.

- Huisman, Jeroen, and Jan Currie. 2004. “Accountability in Higher Education: Bridge over Troubled Water?” Higher Education 48 (4): 529–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000046725.16936.4c

- Jungblut, Jens, and Peter Woelert. 2018. “The Changing Fortunes of Intermediary Agencies: Reconfiguring Higher Education Policy in Norway and Australia.” In Reconfiguring Knowledge in Higher Education, edited by Peter Maassen, Monika Nerland, and Lyn Yates, 25–48. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kickert, Walter. 1995. “Steering at a Distance: A New Paradigm of Public Governance in Dutch Higher Education.” Governance 8 (1): 135–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.1995.tb00202.x

- Lodge, Martin, and Kai Wegrich. 2014. “Introduction: Governance Innovation, Administrative Capacities, and Policy Instruments.” In The Problem-Solving Capacity of the Modern State – Governance Challenges and Administrative Capacities, edited by Martin Lodge, and Kai Wegrich, 1–22. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maggetti, Martino. 2007. “De Facto Independence After Delegation: A Fuzzy-Set Analysis.” Regulation and Governance 1 (4): 271–94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2007.00023.x

- Maxwell, Joseph A. 2013. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Paradeise, Catherine, Emanuela Reale, Ivar Bleiklie, and Ewan Ferlie, eds. 2009. University Governance: Western European Comparative Perspectives. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Patton, Michael Q. 2014. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Pollitt, Christopher, Karen Bathgate, Janice Caulfield, Amanda Smullen, and Colin Talbot. 2001. “Agency Fever? Analysis of an International Policy Fashion.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis 3 (3): 271–90.

- Rothstein, Bo. 2011. The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Van Vught, Frans. 1989. Governmental Strategies and Innovation in Higher Education. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Verhoest, Koen. 2012. Government Agencies: Practices and Lessons from 30 Countries. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Westerheijden, Don, Bjørn Stensaker, and Maria J. Rosa. 2007. Quality Assurance in Higher Education Trends in Regulation, Translation and Transformation. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Winckler, Georg. 2003. “Die Universitätsreform 2002.” In Österreichisches Jahrbuch für Politik 2003, edited by Andreas Khol, Günther Ofner, Günther Burkert-Dottolo, and Stefan Karner, 127–37. Wien: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik.

- Winckler, Georg. 2012. “The European Debate on the Modernization Agenda for Universities. What Happened Since 2000?” In The Modernization of European Universities. Cross-National Academic Perspectives, edited by Marek Kwiek, and Andrzej Kurkiewicz, 235–49. Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang.

- Wu, Xun, M. Ramesh, and Michael Howlett. 2015. “Policy Capacity: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Policy Competences and Capabilities.” Policy and Society 34 (3–4): 165–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001

- Yesilkagit, Kutsal, and Sandra van Thiel. 2008. “Political Influence and Bureaucratic Autonomy.” Public Organization Review 8 (2): 137–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-008-0054-7

- Yin, Robert K. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.